RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

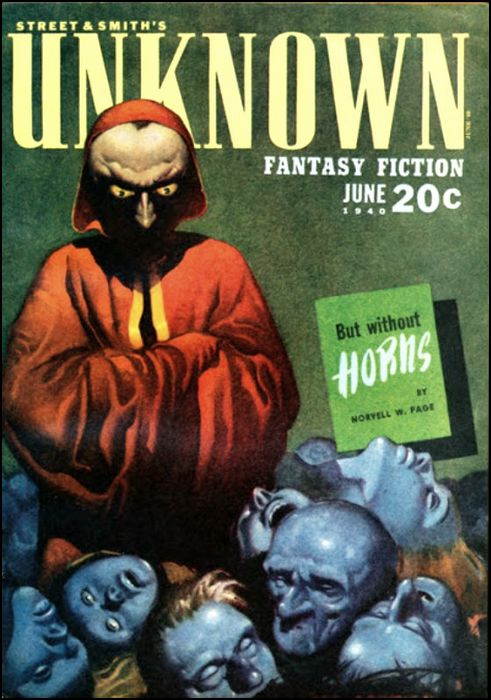

Unknown (US edition), Jun 1940,

with "Master Gerald of Cambray"

GUY OF SALISBURY lay sprawled across the rude pallet of coarse muslin stuffed with straw, just as he had fallen the night before. He had not troubled to remove his long trunk hose of scarlet hue nor the pointed, wine-colored shoon that laced high over his ankles. Puffed, illicit sleeves and a cambric shirt sheathed a brawny form and knotted muscles. Even in drunken sleep his features were firm and frank with goodly youth. His tonsured pate—sign of clericus and student—showed early need for a barber's ministrations. A fine golden fuzz was sprouting and making dim the rounded barrier from close-clustered, leonine locks. His mouth was open and he snored.

His fellow martinet, Jean Corbin, shook him by the shoulder. "Wake up, Guy," he said urgently. "Wake up!"

"Huh!" grunted the sleeper, and sought to turn over.

"Wake up!" repeated Jean, a dark, dapper fellow from the south of France. "It is already an hour past matins and. furthermore Martin, the beadle, is here to take you before the Rector's Court."

"Huh!" Guy grunted a second time and opened his eyes.

The little man who had stood respectfully in the shadows of the bare, low-eyed garret now came forward. He was fat and puffing from his unwonted climb up four narrow, high-pitched stairs. In his pudgy hand he carried the wand and emblem of his office.

"It is true, Master Guy," he said. "The noble rector of the. university demands your-presence immediately you are ready. There is a complaint." Guy rubbed his pate a moment to dispel the mingled fumes of wine and sleep. Then he heaved slowly to his feet and stared—six-feet of bone and whipcord muscles—at the beadle.

"The Rector's Court?" he demanded sharply. "What wish they of me?" His eye flicked to the illicit unsheathed sword that stood in a corner, its point embedded in, the unpainted floor. Bright flecks of spilled wine had dried upon its hilt; but near the tip there were darker, more somber spots of rusty brown.

The beadle turned his discreet gaze away from the weapon. He knew better than to see that which the rules of Paris forbade to students. He gripped his wand of office more firmly.

"The man, Hugues, innkeeper of La Cloche Perse," he explained in apologetic fashion, "died past midnight."

Guy shrugged. "The more fool he. I did but pink him. when he rushed on me with screams and tirades."

"You do not know your strength," Jean Corbin declared, eying his comrade's gigantic dimensions with admiration. "You pierced him clean through the body."

Guy yawned and stretched his arras. "He deserved to die. His wine was stale and diluted with water. He swore to me it was a clear Burgundy and of the finest vintage. I took but a mouthful and spat it out on him for a vile usurer. He seized a cudgel and had at me."

Jean grinned. "You forget. You followed your righteous expectoration with the filled flagon. It caught him a pretty clip on the side of the head," Jean began to chuckle. "I shall never forget how ludicrous the rogue looked standing there, drenched from head to foot in the lees of his own adulterated drink."

"You will come quietly, Master Guy?" asked the beadle warily.

"Of course," Guy laughed. "I will miss the morning lecture of Master Heinrich of Brabant on the ethics, but he is a dull dog and it will be no great loss. Wait but a moment and I shall go with you." He took the tabard—the long, black outer garment of the student—from its pegs on the wall and slipped it over his forbidden finery. The beadle stood with eyes averted, puffing grateful relief. He had expected trouble with Guy of Salisbury, and he had been prepared to retreat at the first sign of violence.

They emerged from the rickety, overleaning house into the cold light of morning and the gathering cries of the crooked street. The Petit-Pont, lined with curious wooden houses, spanned the Seine to the left bank and the scattered quarters of the university.

The beadle picked up his robe delicately as a rooting pig lurched against his fat legs. He eyed with distaste the piles of odorous garbage-at his feet. "You live like a veritable martinet, Master Guy," he complained, "a nesting swallow under eaves. It was understood among your nation that your kin were wealthy."

"So they are," grinned Guy, as they clattered over the wooden bridge. "But they cut me off with not even a sou some weeks ago. My respected father believes I've had enough of the fleshpots of Paris. He desires me to return to our English acres and play the knight. I prefer the clash of disputations, however, to the play of swords; and so I remain, penniless but happy."

Martin looked doubtful. He had just seen the carved handiwork that this mad Englishman had left in La Cloche Perse, but long ago he had learned that a held tongue was better than a coat of mail.

THE Rector's Court was in the rented hall of the English Nation—to which Guy himself belonged. The rector sat in state—a beardless man of four and twenty—not much older than Guy himself. He was magnificent in purple and ermine and the tipped fur around his neck shaded his long, narrow face. Clustered around him were others seated—grave and reverend seniors—all older than the rector. They wore the distinctive cappa—or cope—reserved exclusively to the masters. By their color one could tell their station and the university of their origin. The masters of Paris wore bright scarlet, with tippets and hoods of fur. The fur was not merely for ostentation—spring in Paris was cold and the drafty, unheated halls brought agues to uncovered-tonsures. The doctors of theology were resplendent in red, while one from Beauvais shone in a cobalt-blue.

The beadle extended his wand in greeting to the court and puffed importantly: "I have brought before you Guy of Salisbury, even as your worships demanded."

The rector nodded affably to the English giant. He and Guy knew each other well. They had had many a nocturnal adventure together. In fact, Pierre of Normandy was but this six months a master and less than two weeks the rector. Because he was of noble blood and had many livres tournois in his purse, he flashed a brief few weeks in this seat of power.

"I am sorry it was necessary to call you before us, Guy," Pierre said with a cough of apology, "but the innkeeper has died of your thrust, and his wife lodged a complaint with his guild, who in turn notified the Provost of Paris, who in turn laid the case before King Louis. He thereupon sent his messenger to the lord bishop and therefore the chancellor asked us to inquire into the matter." Guy nodded carelessly. "I do not blame you; it is the form. Yet the rascal deserved what he got. His wine is the worst in Paris and I did but admonish him gently thereon when he came at me with a cudgel." The rector coughed. "I know his wine; it is atrocious. But you... ah... slit his paunch with a sword. A sword, according to the regulations, is a forbidden weapon."

"A sword?" cried Guy, pretending, indignant surprise. "Who said I used a sword? It was a mere knife, such as I use for trencher weapon—a matter of a few inches of steel. No more." The rector coughed again. "There are the man's wife and seven witnesses who depose it was a sword, and a mighty one at that."

"Were there any students or masters of the university among them?"

"Not a one," admitted the rector. "They are all burghers of the town."

"Rabble and offal!" Guy declared triumphantly. "Those rascals would swear themselves into the arms of the foul fiend to decry a clericus.

They envy us our privileges."

"True!" Pierre nodded. "We shall therefore waive the item of the sword and proceed with the mere manslaughter."

He leaned to the right and to the left and whispered to his court. Fur-clad heads inclined gravely and resplendent cappas rustled. The scrivener of the court dipped his quill expectantly into the horn of ink and poised it over the parchment sheet before him.

"We are agreed," said the rector finally. His face took on a prim, severe expression. "Take heed to our judgment. For the slaying of one, Hugues, innkeeper of La Cloche Perse, a burgher of Paris and a member of a lawful guild, Guy of Salisbury, clericus and student of the university, and hence entitled to all the rights, privileges and immunities relating thereto, is required to attend matin mass for three weeks running, to say twenty Aves and Pater Nosters daily during said period, to make confession once every week for three months and humbly announce his fault; and furthermore, the said Guy of Salisbury shall purchase for the benefit of this court twenty quarts of good red wine, of a grade not worse than the first grade of Burgundy. So let it be inscribed."

Guy shook his head. "You are severe in your judgment, amplissimus rector, yet would I not object had I more than a few wretched sous in my purse. Perhaps you have riot heard that my noble father mislikes the learning of Paris and has cut me off from all supplies?"

The rector looked disappointed. The reverend doctors pulled long faces. Already they had been licking their lips over the prospective fine.

"I had not heard," sighed Pierre finally. "In that event, perhaps ten quarts?"

"Not a dram more than five," Guy declared firmly. "And at that I must borrow from my nation. Or belike I should add other penances—such as praying in my shirt at Sainte-Geneviève with book and candle instead?"

"We will take the five quarts," said the rector hastily, and furred heads bobbed agreement. "But next time be more discreet with your... ah... knife. The populace is clamoring for our heads, and King Louis meditates a complaint to the bishop. What is the next case, beadle?"

THE beadle pointed to a queer little mouse of a man who shifted his weight uncertainly from foot to foot and blinked watery and amazed eyes at the scene before him.

"It is this stranger, amplissime. I found him wandering, starved and wholly bewildered, through the Rue du Fouarre at dawn. He did not seem to know how he got there, nor even where he was, and his Latin has a barbarous lilt to it that made understanding difficult. I deemed it wise, therefore, to bring him before your court for inquiry and disposition."

The little man started forward indignantly. He seemed suddenly to have found his tongue. "My Latin barbarous!" he cried. "That is a base lie. For twenty years have I studied and taught the tongue of Cicero and Virgil, of Tacitus and Ovid. There is no one in all America who speaks a purer, more classical Latin than myself."

Guy paused, on his way out and stared in amazement. Martin, the beadle, had spoken true. The man did speak a queer Latin. The syllables were strained, and the inflections odd. There was a formal pomposity about his speech that smacked of the manuscripts rather than the free and living flow of ordinary, everyday give and take.

But the strangeness of his tongue was the least of the matter. His clothes were thoroughly outlandish and. incredibly ugly. He wore no cappa, or tabard, or even toga. His spindly legs were encased in two long cylinders of some woolen cloth, his neck was surrounded by a high, starched wide band that seemed to choke him, and from which dangled pendent into the mufflings of his coat a streak of flame-red silk that could only have come from semi-mythical Cathay.

His countenance was mild and sear, like an autumn leaf. A gray stubble of unshaven beard dotted his face. Owlish eyes peered from behind a pair of most curious spectacles. Now spectacles in themselves were rare enough, but these were of a fashion and cunning manufacture such as Guy had never seen before. His forehead was lofty and baldish. Gray wisps of hair disclosed no sign of tonsure such as a cleric should possess.

Pierre of Normandy surveyed him curiously. There was a stir among the doctors of theology.

"You invoke great names," Pierre told him, "but nevertheless your Latin is false in quantity and accent. Whence come you, stranger? I never heard of this land you call America."

The little man deflated suddenly. A strained frightened look came over his countenance. His hand trembled as he made wiping movements over his forehead. "America?" lie whispered. "I wish I knew. Yet if this incredible thing is true; if all of you are not the mere creations of a dream from which I must inevitably awake, then America is far beyond the sea, beyond the floods of time itself."

"Speak not in riddles, man," declared the rector peremptorily, or, if you do, use the proper logical forms. The minor premise, limps mightily in your argument. But you speak of lands beyond the sea. Everyone knows that the Western Ocean has no end; that it stretches to the base of purgatory-itself. Now, please, no more nonsense. You claim to have studied and taught. From what university came your license and in what field—arts, civil law, the canon, medicine or in theology?"

The little man bowed humbly. "My name is Gerald Cambray. I am—or was—my senses are a bit confused—professor of Latin in Harvard University—Universitas Harvardiensis."

The rector looked puzzled. There arose a great buzz of whispering among the masters. Guy strained his wits. He had been a wandering scholar for several years—a goliard—with a pouch of bread at his side; a song on his lips, and a kiss for every wayside pretty wench; he had sought knowledge from the great teachers of every school from Oxford to Bologna; but never had he heard of this Harvard.

Neither had the rector. "I suppose," he said with fine sarcasm, "this university which you claim is in this equally mythical America?"

Gerald Cambray's eyes flashed. He seemed to Guy like a rabbit who puffs up with courage in defense of his hole and spits defiance at intruders...

"Harvard," he said with heat, "is a mighty school—the greatest in the world."

The court rocked with laughter at that. Even Guy, loitering, grinned widely. The scrivener howled. Martin, the beadle, quivered like a jelly. Everyone knew that Paris, eldest daughter of kings and favorite child of popes, was the shining luminary of the Universe. True, those who wished to become learned in the law went to Bologna; those who sought the rewards of medicine attended Montpellier or Salerno; but in all else—

Pierre of Normandy wiped his eyes with the ermine of his robe. "There is no mention of this great school of yours in any of our parchments. Belike it is some local creation of a petty princeling without the ius ubique docendi—the license to teach everywhere—that only the holy pope or the emperor may grant."

GERALD CAMBRAY, the stranger, bethought himself and shivered. His fire vanished. He looked scared, Guy of Salisbury was moved by a sudden impulse. The bedraggled look of the man stirred a protective feeling in him. He strode over to the little man and clapped him kindly on the shoulder.

"How-now, Gerald of Cambray," he said, "take heart. Here in Paris are men of every race and clime—even from Muscovy. Perhaps some "comrade from your local Studium ,will appear."

The man in the curious costume shook-his head. "No one else caw appear. I was a mistake—if this is not a dream. Paris!" His round eyes grew rounder. "The University of Paris in the Middle Ages! Good Heaven!"

"I understand you not," Guy retorted with some asperity. "The Middle Ages, forsooth. We are moderns; this is a modern age. We have learned everything that God would wish us to know. Knowledge is complete, final. But come, you are: obviously a stranger in our midst. What will you do to make your bread?"

Cambray sucked in his breath. "I could teach,", he suggested timidly.

"That," declared the rector, "is impossible. In the first place, you belong to no nation."

"I could manage to enroll him in the English nation," declared Guy. "We have a number of foreigners in our midst—chiefly German."

"But I am English," cried Cambray joyfully, "or, rather, of English descent: See, I speak to you in the English tongue."

Guy listened carefully. "What says he?" Pierre demanded.

The English lad shook his head, frowning. "Now, by St. George," he swore, "this is indeed a marvel. His Latin was bad enough, but such a foul jargon which he now spews and insults by the name of my native tongue I never heard in all my years. Yet here and there in sooth there is a word or phrase that hath a familiar ring."

Cambray groaned. "What year is this?"

Pierre stared. "Are you mad or witless? Everyone knows that this is the year of Our Lord—1263."

The little man turned pale. To Guy it seemed that he had braced himself for a blow that he knew was coming; yet, when it came, it felled him just the same.

"Then it is not a dream," he whispered, half to himself. "No wonder the English of 1939 sounds strange to ears that know not even Chaucer."

"What say you?" asked Guy.

"Nothing," he muttered. "I thank you for your offer to induct me into your English nation. I can teach—I taught Latin for twenty years."

The rector laughed mockingly. "The veriest student is a better Latinist than you. The four nations that comprise the arts would never grant you a license in that tongue. What else know you?"

Guy stood close to him. He heard him muttering to himself. "Let me see. I know a smattering of science—physics, chemistry. Certainly far more than they could possible know. But one needs apparatus—which I wouldn't know how to handle myself. One needs techniques. History? Modern history isn't in existence yet. Ancient history—as I know it—they wouldn't believe. Geography? They would thing I was crazy. Literature? What good if the books are not yet written. Good Lord! What could I teach them? Mathematics? I know a little algebra, some geometry:—I've heard of calculus. But—Ah, I have it! Astronomy. At least the Sun, the Moon, the planets and the stars are there to see. I know little enough in all conscience, but surely—" Aloud he said: "I am acquainted with the stars and their motions, masters and doctors of Paris. I could teach students their motions and orbits, their sizes and plan."

The rector stirred. "Know you then the noble science of astrology?" he demanded eagerly. "Can you foretell the future from a reading of the stars?"

The little man shook his head vehemently. "That is nonsense," he declared. "The heavens have nothing to do with the future."

The doctor from Beauvais spoke up in peremptory manner. "The man is mad. Does he not know that there is. a chair in astrology at Bologna; does he not know that Michael the Scot foretold future events for the emperor himself?"

The rector was disappointed. "Astronomy! Hm-m-m! Perhaps—You know, masters, we do find difficulty in fixing the date of the Resurrection in each year. It is the least of the Quadrivium, of course, but—" After much cogitation it was so decided.

Master Gerald Cambray from the lands beyond the sea would be permitted to gather such students as he could and teach the aspect of the heavens to them.

"Of course, the chancellor will have to issue a license to you. in due form," Pierre announced. "But the worthy chancellor accepts our command in all things since our last secession." He turned to Martin, the beadle. "Next case!"

GUY saw that the little man was bewildered. He saw other things as well. The new-fledged master required students. In Paris an unknown master in such a minor phase of the seven arts as astronomy would find them, most difficult to obtain. And, no students, no fees. No, fees, no bread or wine.

Guy himself was in a somewhat similar state—as to bread and wine. Last night, when he had run. the scoundrelly innkeeper through, he had caroused away his last livre with a lordly gesture. He required money.

He approached the befuddled master and took him by the arm. Unresisting he led him out of the hall, into the roaring street.

"I," he said, "am Guy of Salisbury, a student of the arts for many years. In some few days I am ready for my bachelor determination. I require money, you require pupils. Let us make a deal."

Cambray stared. "What do you mean?"

"Every new master," Guy explained, "needs a runner; A student who is well known among his fellows and popular; who can expiate the advantages of the learned master, who can promise them in the name of the master certain discounts on the fixed fees or a new robe at the end of the term, and who can thrust off the. clamoring runners of other and inferior masters." Guy finished modestly: "I am such a man—for a commission, of course."

Cambray sputtered weakly: "But that is terrible. That is making a base commercial transaction of a noble profession."

"What would you?" Guy asked practically. "The master, must live. There are a thousand clamoring licentiates seeking pupils. There are not enough to go round. Leave it to me, Gerald of Cambray. We shall make an excellent team between us. But first we must obtain for you a school in the Rue du Fouarre—Straw Street—and then we visit the taverns for pupils."

The street on which they walked was narrow, tortuous, liquid with mud and filth. Pigs rooted restlessly through the flung garbage; a dead dog exposed his sightless eyes to the thin sun. The rickety frame houses overhung the thoroughfare, and from the open street-level fronts came the sounds of hammering and thumping and the smell of good, seasoned leather. Here was a cobbler pounding at his last; here was a blacksmith striking sparks from an anvil on which lay a heated bend of iron. Long loaves of bread gave up their odors as they baked in crude ovens; a cabinet maker was building a lordly carriage with laborious adz and hammer. Apprentices, in leather aprons and brown wool-hose, lounged in the doorways, crying out upon the passers-by, calling their masters', wares and interlarding business with pert remarks upon the blowzy washerwomen who hurried by to the banks of the Seine to rinse their clothes in that murky flood.

Cam bray gulped. He looked a little green around the gills. He tried to hold his breath, failed. "Isn't... isn't it a bit stifling around here?" he strangled finally. "All that garbage—Why don't they clean the streets?"

Guy sniffed the air. "I smell nothing," he declared. "Except"—and he grinned—"the good odor of baking bread. Which reminds me; I have a few sous left:" He darted into a bake-shop, came out holding a long, crusted loaf under his arm. He tore off a piece with his hand, crammed it into his mouth. He tore off another piece, offered it to Cambray.

The little man gulped again. He turned greener than ever. "I... I'm sorry," he whispered. "I... I'd vomit if I ate in this atmosphere."

Guy looked at him with a certain contemptuous pity. "You'll starve, then," he said placidly, and crammed another generous-portion into his mouth.

As they lived through one narrow, crooked thoroughfare into another, the streets became more and more crowded with fresh young faces. Students of the university, drawn to Paris from all over the world by the magic of the masters, blond, brunet, tall, short, fat, lean, hawk-faced, round as moons—but all alike in tonsured pate and the long, black tabard that draped below their knees.

Guy was popular and well known among them. He waved careless greetings to numerous salutations; again and again he was stopped and made to relate his exploit with the unhappy innkeeper, and the penances he was compelled to do therefor. There were murmurs of indignation.

"Five quarts of rare Burgundy!" exclaimed a dark Florentine. "Me-seems Master Pierre of Normandy swells it at our expense since the nations made him rector. I mind not the Aves and the. confessions; but, the other touches the purse. For a lousy burgher who deserved what he got! What is Paris coming to?" And he went away shaking his head.

Cambray looked startled. "But it was murder!"

Guy began to feel he had made a mistake in taking this helpless foreigner under his protection. He was becoming boring with his queer ethical judgments and his oversensitive organs in the face of a normal Parisian street. He was about to say so when an overhanging window above them opened, a brawny housewife framed suddenly in the oblong; two bare, brawny arms heaved and a huge basin of; assorted slops splashed its contents down upon their heads. Guy jumped with the agility of long experience and missed all but a few spattering drops. But poor Cambray was drenched from head to foot in foul-smelling liquor.

Mechanically, according to custom, Guy lifted his fist and yelled objurgations against the unmannerly dame; but the window had shut with a bang and his tirade was directed against a blank wall.

"Holy Mother!" he ejaculated disgustedly to the forlorn, dripping little man, "but you are an infant in the ways of cities. Don't you know better than to walk close to the wall, or not to jump wide when a window creaks overhead?"

Indistinguishable, gurgling sounds came from the victim.

"Oh, well," sighed Guy, wishing he had not been fool enough to take this strange, helpless person under his. wing, "you need other clothes in any event. My fellow martinet, Jean Corbin, is about your height and build. He has a second outfit. You will pay him for it when the fees begin to come. Meanwhile, here is a tavern where you can wash the filth from you and gain a stoup of wine."

THE swinging sign of Le Coq et la Poule beckoned them in. On it a fierce-looking rooster spread its gilt wings and crowed over a meek little brown hen. They entered the cavernous depths. It was still morning and only a single denizen sat brooding over his leathern goblet in the farther dim corner, close to where the long spit turned over a charcoal fire and the appetizing smell of roasting fowl inundated the air.

The tavern keeper, a burly red-faced Norman, came bustling out at the sound of their footsteps on the earthen floor, his smile of oily welcome slipping onto his countenance like a mask, and rubbing his hands on his greasy apron.

"Messieurs!" he greeted, "what is your—"

He stopped short, and the smile froze to open-mouthed, terror. The exploit of Guy of Salisbury had already traveled like the wind through the byways of Paris. He backed hastily toward the kitchen.

"If you reach for a cudgel," Guy said in a terrible voice, "I'll slit your throat from ear to ear. And-if you call for aid, there are a hundred students passing in the street who seek nothing better than a fight. Serve us properly and you need fear no harm."

Mine host swallowed hard and came back warily."What is your wish, Monsieur Guy?"

"First, take Master Gerald of Cambray to the well and wash him clean of the contents of a chamber pot. Then set before us a brace of fowl, done to a turn and tender to the teeth. With it a dish of little peas, firm in texture yet juicy withal, two loaves of golden-brown bread, still hot and crusty from the oven, and two beakers of Burgundian, of a rare and delicate flavor and cooled long in your cellar." Guy flexed his great arms. "And, remember my companion, Gerald of Cambray, is a great master from the famous Studium Generalis of Harvard across the seas. His palate is so fine he can detect even a drop of filthy water mixed into the wine."

Mine host raised his hands to call on the Virgin for testimony. "Everything shall be as you say, Monsieur Guy. May I roast in hell if the wine be not to the taste of your noble companion. Come this way, Master Gerald."

Guy sat down on a bench, grinning. Perhaps this stranger might not prove such a burden to him after all. There were possibilities. The seated man in the corner near the fire stirred, but did not turn his face out of the shadows. He toyed with his wine and seemed deep in thought. His cope was ornate in purple, trimmed with gray fur. It fell to his ankles. His long, bony head showed a ring of. jet-black hair around the shaven tonsure."

In due time Cambray returned, washed, cleaned, though smelling somewhat of the odorous slops. His nose was wrinkled in piteous disgust at himself. Guy chuckled and bade him to a seat on the bench. The obsequious innkeeper brought in noble flagons of wine, a steaming dish of peas, bread and two golden fowl, each on a trencher. He placed leather cups before them, and retreated hastily.

Guy stretched out his long legs in satisfaction. He poured the wine into the cups, surveying its dark-red shimmer, as it flowed, with a critical eye. "Ah, this is more like it. Nothing like a little blood-letting to bring these rascally fellows to heel. Drink to your mastership."

The little man was ravenous. It was obvious he had not eaten in some time. He downed the wine and tore into the bread. But he looked doubtful at the fowl. "Are there no knives and forks?" he said finally.

Guy took a dagger out of his belt. With one deft swoop he dismembered a leg. His fingers dipped into the peas, scooped up a round two dozen to pop into his mouth. Then, with greedy fingers, he lifted the leg, crunched on flesh and bone with sucking grunts. "Huh!" he demanded with mouth crammed full. "Have you no dagger? That is knife enough. As for forks, that word we know not. Is it some new-fangled weapon?"

Cambray grimaced. "I forgot where I was," he said hastily, and lifted the fowl delicately in his hand.

HUNGER was ultimately satisfied. Guy felt expansive, as he always did when a good meal was under his belt. So, evidently, did the little man. The strained look of terror seemed to have passed from his owlish eyes.

Guy slicked noisily on his teeth.

"Now," he said grinning, wiping his greasy lips on his sleeve, "tell me the truth, Master Gerald. I have taken a fancy to you and it will go no further. I am discreet. That cock-and-bull story you told the rector—it was a masterpiece of invention. But to me you can speak fair. Belike you have slain a cleric in some distant land and fled here to Paris for sanctuary. If so, and you are not already excommunicated and under the ban, our English nation will save you from harm. With proper payments I can promise you absolution."

The little man started. His hand trembled violently. It seemed as if he were remembering all over again.

"I told the truth, Guy," he said hoarsely. "Would to Heaven it were all a dream. I come in fact from a land called America beyond the great sea and I was a teacher of Latin in a great university called Harvard." Guy laughed indulgently. "I see you do not trust me. Everyone knows there are no lands across the sea, and there is no record of such a Studium as that you tell of."

Gerald Cambray leaned forward. Earnestness was written all over his face. "Not in this year 1263," he said, "but I came from the future—from the year 1939, to be exact. In almost seven centuries much has happened to your world. The Middle Ages were swept away, a renaissance occurred; Columbus discovered the land of America and a great nation, was founded and grew to maturity. Science took mighty strides. Men fly through the air faster than birds; there are chariots that skim along the ground at tremendous speeds. It is possible to speak clearly and distinctly to one's friend though thousands of miles apart, and music is dragged out of the ether for one's entertainment." He sighed. "I wish I were back there now. All my life I had dreamed of the glories of Paris and the university in the thirteenth century, but I had never thought of the filth and garbage, the emptying of slops from windows, the wanton killings, the lack of forks, the eating with one's hands."

Guy was slow to anger. That had always been his boast. Whereas a hotheaded Picard might have run his host through at the first taste of watered wine, he, Guy of Salisbury, being an Englishman, had merely thrown the offending liquid into his face. Not until the fool had come for him with a cudgel had he drawn his sword. Even so it had been merely his intention to lance the villain's veins a bit. He said this, to himself carefully as he hearkened, to show that he was not prone to gusts of temper. But this fellow who sat next to him was trying him sorely. Here he had practically paved the way for a true and proper confession of sin, and this was the answer. Not content with repeating the incredible, the fellow was actually embroidering on his tale. Did he think Guy a fool? Guy had been in Italy, had wandered through Scotland, had even journeyed to Spain to listen to a certain master at the newborn Universitas at Salamanca. He had seen the world; he was no peasant grubbing his ancestral acres.

"Now, look," he said with heat, toying with his dagger the while, "I am a patient man. But I do not like being mocked at. You have hearkened to the sayings of Roger Bacon, who is even now imprisoned here in Paris by order of Bonaventura for his nonsensical predictions. But do not prate such stuff to me as you would pull a cap over your eyes."

"Roger Bacon!" Awe breathed in Cambray's voice. "Of course! He was ordered into confinement in 1257. Everything checks. Believe me, Guy, I am not romancing. Everything is as I state it. Listen! I actually lived in that far future of which Bacon only caught distorted glimpses by reason of his soaring imagination. I was a peaceful professor, content to teach succeeding generation's of students, to breathe the quiet air of university life. Then I took ill—the date was in October, 1939. Classes had just commenced; I was tired, exhausted. There were strange buzzings in my head. I left class hastily and went to my room. Crossing the campus things began to shimmer before my eyes. I tried to call out, to seek help. No sound came from my throat. I remember that everything seemed to spin around me. There was a roaring noise, a blast of blue flame. I fell and remembered no more."

He took a deep breath, and stared through those peculiar spectacles of his. "When I came to, I was walking unsteadily in. a strange, narrow street, with strange wooden houses hemming it in. I was in a daze, not knowing what had happened; thinking perhaps it was a dream. Then Martin, the beadle, saw me and questioned me. Still dazed, I did not realize the fact he was speaking in a sort of Latin. I answered in the same tongue. The rest you know."

He paused a moment, brooding. "I don't know exactly what happened. I was not a scientist; just a teacher of languages. Perhaps Einstein might have been able to explain it. But I was carried back through time and space to this era, this incredible place." He passed his hand over his brow. It glistened with perspiration. "You must believe me," he cried suddenly, "or I shall go mad. I beg of you—"

THE seated man near the fire suddenly rose. He came toward them with measured step, his long, purple toga flapping at his heels. His head was long and narrow and his deep-socketed eyes burned with little black flames.

Guy sprang to his feet and bowed. "Cecco of Vercelli, the astrologic doctor," he said with a touch of fear.

Cecco nodded curtly and probed Guy's companion with keen, reflective glance. "You are that alien to whom the rectorial court has granted a license to teach astronomy?" he said abruptly.

"I am."

Guy was bewildered. "But how did you know, Master Cecco?" he cried. "We are come from thence but a few bare minutes."

The man smiled—or, rather, his face smiled. His eyes remained cold, penetrating. "Many things are. known to me even before the event," he replied. He turned back to Cambray. "Do you intend to teach the higher science of astrology as well?"

"Not at all," answered the other with some heat. "That is a charlatan humbuggery, not a science. Yet if I wished, I could put all your predictions to shame with the accuracy of my own."

Guy was aghast. He was brave enough physically, and prided himself on his freedom from most vulgar superstitions. But to call astrology a charlatan science, and that in front of its most noted and dreaded expounder, the mighty Cecco, who had predicted successfully the accession of Urban XV to the papal throne, was utter sacrilege. Why, everyone knew that the stars held in their ordered wheelings the fate of all mankind—it had been proven time and time again.

Cecco's eye flashed. Yet his voice was almost caressing. "I suppose," he murmured softly, "that you, who can predict without the stars, should find it easy to place the date of your own death?"

The little man was taken aback.

He lost color. "No," he faltered, "I cannot do that."

Cecco smiled. "Then listen to the stars whose messages you see fit to mock. Within a month from this very day, even to the hour, you are a dead man." He swept up his trailing toga, bowed ironically. "I wish you both good day, messieurs." Then he was gone.

The fire in the huge hearth seemed suddenly cold. Guy felt colder in the pit of his stomach. Cecco had predicted, and his predictions invariably came true.

"You see what you have done with your mockery of things sacred and your vain pretensions," he declared angrily.

The little man shrugged. That much Guy must grant him—he was brave for all his scrawny size, or a heretic at heart. He did not seem in the slightest perturbed. "Rubbish!" he retorted. "Neither your Cecco nor any living man: can foretell the future."

"Yet you yourself made that claim."

"That's different. I could only predict those things of which I had knowledge that they had happened as past events when X lived in 1980. Such as, for example, that Roger Bacon would remain confined in prison until 1267 and that he would die, an embittered old man, in the year 1292."

Guy grinned. "That is an easy guess, incapable of proof for at least four years. Pray predict some things that will happen within the month, as Cecco has just done."

Cambray shook his head. "I cannot," he admitted. "This year of 1263 is a blank to me. X was not sufficiently deep a medieval scholar to know what will take place."

Guy snorted, lifted the stoup of wine, replenished his beaker, and drained it to the bottom. "Bah!" he said. "Let us go. Furthermore, Master Gerald, let me warn you not to speak of this miraculous transposition in time if you desire to keep a whole skin. You have just made a powerful enemy in Master Cecco; you will make even more powerful enemies in the Bishop of Paris and the papal legate if you preach such heretical doctrine."

He shoved back the settle and rose. At the sound, the innkeeper came hurrying in. "Your account, Monsieur Guy. It comes to—"

Guy placed his hand significantly on his dagger. "Let us hear no more of accounts, Monsieur Toad," he retorted. "Behold before you a master of the university—one Gerald of Cambray. When his fees roll in, he will make it good with you. Farewell!"

He caught the bewildered little mail by the arm, hurried him out to the accompaniment of dire threats to lay this robbery before, the king himself. Outside, Cambray said in troubled tones: "The man should have been paid. After all—"

"With what?" laughed Guy. "I have a bare dozen sous in my purse. You have none. Let him wait—or not; it does not matter. Now to gain you a school."

THE Rue du Fouarre—Straw Street—was the most famous street in the world. Within its tortuous, turbulent confines lay the schools of the masters of Paris—tumbledown, dilapidated, ramshackle wooden houses rented or purchased from burghers who found them no longer fit for their own living.

It had rained the night before and the thoroughfare was a bottomless quagmire of liquid mud and filth. The stench was indescribable, but Guy's well-accustomed nose found it not too oppressive. He could see, however, that his companion was blue in the face with repressed breath and the sight made him chuckle.

Horsemen dashed by with a fine disregard for pedestrians, their horses' hoofs churning up the mess and spattering it over cappas and woolen gowns alike. The street swarmed with scholars in their shaven tonsures, with citizens and citizens' wives hastening about their modest business, with peddlers crying their wares, with pimps urging the merits of certain discreet houses, with fate, priests ambling by on fat mules, with dirty, half-naked urchins perpetually underfoot.

Through the doorways and out of patched, broken windows came the drone of the masters' voices, lecturing to their scholars. In some cases the drone was interrupted by whistlings and stampings and cries of derogation as exception was taken by the irreverent audience to a thesis of the master.

In the street a drunken scholar from Bourges, swarthy and staggering, collided with a tall, bony Scottish lad. The Bourgian screamed oaths and made for his dagger. "Barley-eater," he cried, "what mean you by jostling me?"

The Scotchman spat into the mud. "Cowardly, gluttonous Bourgian," he countered, and gave his opponent a shove that sent him face down into the muck.

As if by magic the swarming street coalesced. Cappas were thrown back, knives, jerked out. Cudgels were seized, stone lofted out of the mire. Instantly Straw Street was filled with shouts. "Up, France! Up, England!"

A conglomerate crew of French, Burgundians, Portuguese, Italians and men of Provence rushed to the aid of their comrade of Bourges. An equally conglomerate crew of English, Scotch, Germans, Poles and Swedes rushed to, rescue the Scotchman.

Guy grunted joyfully and pressed forward.

"Good Heaven!" Cambray cried in alarm. "Where are you going? They'll kill each other!"

"That Scot is Donald of Doon," Guy roared back over his shoulder, "a member of the English nation. We must help. Get yourself a stick, or a stone, and join. You are practically a member now."

Then Guy was in the whirl of kicking, slashing, thrusting students. Out of the houses came tumbling more lusty scholars and their masters, uttering loud cries and thirsting for the fray. His last glimpse of the man who claimed to have come from the future was of a cowering, scared figure flattened up against the side of a house, his mouth open and his eyes goggling.

Guy felt a sting across his forehead and laid open his adversary's cheek with a might counter-thrust. The street was a heaving, struggling bedlam of sound.

Then someone yelled: "The provost's guard!"

FROM the end of the thoroughfare came the tramp of horses. A dozen men with the king's insignia on their hats and led by a stern, granite-faced provost sporting the fleur-de-lis, clattered down upon the screaming mob.

The provost reined in, naked sword in hand. "Messieurs, the students of Paris," he called, "stop this rioting or the king must hear of it."

An ugly roar rose.in answer. The students, just how joyously engaged in slitting each other's throats, turned in unison on the guards.

Guy raised a mighty voice. "What means the Provost of Paris in invading the, precincts of the. university? Know you not our privileges? Get out, offal from the dung heap, before we sweep you out."

Some of the horsemen turned pale, and lifted their swords nervously in their scabbards. The provost flushed. He waved his weapon threateningly. "You go too far, students of Paris," he cried in a voice smothered with fury. "To the foul fiend with your privileges!"

"At the blasphemer!" yelled Guy and hurled forward, knife in hand. Behind him surged the throng—late combatants and mortal foes amicably side by side in a common front against the common enemy. Two of the provost's men bolted and fled, the others stood their ground.

The sword of the provost flashed down at Guy. He ducked under the belly of the rearing horse. The blow took a blond-haired Netherlander instead and cleaved him through from shaven pate to the bridge of his nose. He fell with a scream, spurting blood into the trampled mud.

Guy twisted upward with his dagger. The keen point entered the horse's, belly. The horse stumbled, neighing shrilly, and precipitated its rider to the ground. Guy flung, himself upon the provost as he strove to disengage his sword from the stirrup in which it had been caught. Then his foot slithered on the corpse of the Netherlander and he fell. With an oath the provost freed his sword, raised it for the murderous blow. Guy tried to rise in time, fell again. The sword swept downward. Guy shrieked: "Up, England! Help, comrades!" But the twisted street was a confusion of noise and oaths and screams and rearing horses. No one heard him. There was grim triumph in the provost's eye.

Someone catapulted from the wooden wall against which he had been pressed. A small, owlish figure clutching desperately in its fingers, a dagger dropped by one of the combatants who would never need it any more. His hand raised simultaneously with the downsweep of the sword. It lunged forward, straight for the back of the triumphant provost.

The sword faltered in mid-swing. The man's eyes glazed with sudden death. He crumpled and fell in a heap, almost smothering Guy with the weight of his fall. Guy crawled painfully to his feet, wiping the mud from his-brow.

"Thanks, Master Gerald!" he said warmly. "There will be no question now of your admission to our nation. You have earned your entrance."

But the little man had dropped his knife. His eyes were shuddering pools upon the blood that dyed his hand a scarlet; he looked sick and ready to vomit. "I... I killed a man!" he whispered. "I... I killed a man!"

"Don't get chicken-hearted," Guy said roughly. "You've shown yourself a man. Now don't play the woman. Come on; there is more work to do."

But the battle was already over. The guard, seeing their provost slain, and overwhelmed by numbers, fled incontinently back the way they had come, accompanied by the jeers and threats of the triumphant scholars.

In the quagmire lay half a dozen figures—the provost and one. of his men, the Netherlander in the stillness of death; and three wounded scholars of the university—one of them, by his blue cloak, a; master of Beauvais.

Guy leaned against the door lintel of a neighboring house, panting heavily. "Take up the wounded and carry them to the doctors of medicine," he ordered. "As for our dead comrade, Dietrich, bring him softly to the nation of the Picards, to which he belongs. There all the nations and the faculties will pass in reverence and decide what protest to make to King Louis for this foul murder."

"How about the two dead men of the guard?" Cambray asked faintly. He had already been sick. One further contribution to, the general filth of the street did not matter.

"Those carrion?" Guy said in some surprise. "We leave them here for the buzzards and the pigs to finish, and as a warning to all Paris that the university knows how to defend its privileges."

"HOW like you this school for yourself?" demanded Guy of the new-fledged master of arts, Gerald Cambray.

The new master looked dubious. It was the morning after the notable encounter with the provost's guard. He no longer wore the outlandish, barbarous costume in which he had been found. His thin shanks were hidden under a decent cappa of sober brown, rather too large, perhaps, so that it billowed out in ludicrous fashion as he waddled gravely down the street. A linen shirt, long gray stockings, jerkin of similar hue and breeches of brown encased his limbs. Only the shoes, borrowed from Jean Corbin, flaunted a touch of scarlet and-flourished upward at the toes in the Italian fashion.

A hurried evening session of the English, nation to discuss the outrage had made no difficulty of admitting him to their ranks on Guy's sober affirmation that Gerald of Cambray. was a master of Cam-.

bridge. "The Holy Virgin forgive me for a false oath," he grimaced aside to the still-trembling Cambray, "but in fact I stated no falsehood. You told me this Harvard of yours lies in a town called Cambridge. It.is not my fault that the nation knows only of the Studium by that name in England."

And now they were examining the interior of a house on the very end of Straw Street, on the Left Bank, close to the Petit-Pont. The owner, a fat, pursy burgher, his butcher's apron bloody around his middle, rubbed his ham-like hands with eager unction.

"It is a noble room," he told them modestly. "Master Thomas Aquinas, the Dominican, but recently taught in these very quarters. If I let you have it for one livre tournois per month and thereby deprive my children of the bread they should rightly have, it is because I have taken a fancy to this new master recently arrived from England."

But Cambray only sniffed. It seemed to Guy that all this stranger did was go around holding his nose. "What is the matter?" he demanded.

The little man stared with open disgust around the large, drafty, ill-ventilated room. A single scarred and battered chair faced one end. There was no other furniture. The walls, of a muddy plaster, dripped with damp and leprous spots. The bare pine floor was strewn with rushes. On these the students were supposed to sit, cross-legged like Turks, and hearken to the pearls of wisdom dripping extempore from-the master's lips. It was cold, and there was no bellied brazier for heating.

He pointed a delicate finger. "That straw!" he said in a choked way. "It smells worse than any stable. Fresh straw must be strewn."

The butcher held up his hands in horror. "The master jests," he cried. "I myself placed that good, clean straw on the floor not over three months past. Surely Master Gerald knows that it is changed but once a year, come the Feast of St. Denis."

Cambray turned pleadingly to Guy. But Guy only nodded. "Of course," he agreed, "that is the Custom: There is not need to change it oftener. You had better take this school," he advised kindly. "It is a good one, and schools are now at a premium, what with, the influx of Franciscans and Dominicans. Besides"—he lowered his voice—"this good burgher is the only house owner on the street silly enough to wait for his rental, instead of demanding it in advance."

The little man sighed and snuggled deeper into his voluminous brown robe. "Very well, then. But! wish I were back in the twentieth century, where things didn't smell so."

"Master Gerald!" There was reproof in Guy's voice.

"I'm sorry,", he murmured apologetically, "It just slipped my tongue."

GUY OF SALISBURY swaggered into the Auberge Notre Dame well satisfied with himself. His, association with this curious master, who pretended to have come, back in time from a fabulous future, had proven so far quite lucrative. On the strength of it he had eaten and drunk on future earnings, and he still jingled the pitiful few sous in his purse. Let his family back in Salisbury fume and refuse him. the gold to which he was entitled—he need not forgo the fleshpots of Paris and the disputations he loved. Already he had mumbled over his few Aves penance and meekly confessed his sin to a most tolerant prelate at the Church of St. Cosme et St. Damien, where the English nation worshiped.

He was met. with raucous shouts from a host of scholarly revelers and youthful arts masters flushed with wine. A gray doctor of theology sat discreetly in the rear of the inn.

"Welcome, Guy," cried a dozen voices. "Come and celebrate with us the glorious victory over the provost."

He took the first tankard of wine that was thrust at him, emptied it in one huge draft. A haunch of beef turned slowly on the spit, yielding fragrant odors. Dice clinked in a leathern cup, rolled clicking and dancing along the great pine table. His fellow martinet, Jean Corbin, waved at him. "Will you have a turn with us, Guy?" he cried jovially. "If I win this throw I seek better quarters than our verminous garret. Pray for me."

The dice rolled and quivered to rest. Two solitary spots heaved into view. The gamester opposite him laughed hoarsely and raked in the pile of silver that lay between them.

Jean sighed and shook his head. "Perhaps our nest under the eaves has its points, Guy," he said. "I have no luck with wenches or dice."

Just then there was a commotion at the door. A flustered lad, not over fifteen, with his face still innocent of down, seemed to catapult through. Clutched tightly under his arm was a tattered bundle, obviously stowed with all his worldly goods; his heavy boots were plastered, with the mud and dust of many roads; his round eyes were wide on the uproarious scene.

Behind him catapulted half a dozen students, whom Guy recognized as runners for various masters. "You will do well, good sir," cried one, "to attend the lectures of the illustrious Albertus of Germany. His fame spreads throughout the Universe as a clever logician. Besides," he said in half an aside, "he will willingly grant you a warm, new cloak and a yellow biretta when you become a bachelor."

"Bah!" sneered another. "Hearken not to that cozening wretch. Albertus knows not a major from a minor; his syllogisms are the laughingstock of Paris. Now take the noble Rinaldus, just arrived from Bologna. Now there is a teacher who can induct you into the mysteries of the canon law and gain you a nice, fat benefice when the time comes."

Guy forced his giant frame through the quarreling, struggling mass. He caught the bewildered youngster by the arm, pushed him by main strength into a corner. "You are a likely lad," he thundered, "and, by St. Denis, I hate to see you limned by these lying rogues. What have they to offer? Humdrum masters from Bologna and from the beer-swilling realm of Germany. Listen now to my offer. Master Gerald of Cambray is unique in Paris. He has studied and taught in a university rarer for its graduates than pearls from India." He brought out the syllables with bated breath. "Hast ever heard of Harvard, the great university across the seas?"

The scared little peasant shook his head in shame. "Nay, monsieur, I confess to my sorrow its name has not penetrated to my native village."

"There you are," Guy said triumphantly. "Its name is too sacred to be on every vulgar tongue. Only one master is incepted each year. Even the archbishops clamor in vain for entrance." He lowered his voice. "Furthermore, this most excellent master will teach you astronomy, the greatest of the seven arts. Her will discourse for you on heavenly things and bring down to your earthly ears the music of the spheres. How much have you in your purse for this year's fees?"

"Four shiny livres d'or," answered the rustic mechanically.

Guy pretended surprise. "Now by all the saints!" he exclaimed. "That is in truth miraculous. Why, that is the very fee demanded by this mighty master." He shoved with his shoulder at his indignant fellow runners. "It is a bargain then." He raised his voice. "Ho, there, rascal of an innkeeper. Bring for my friend and myself two plump, tender pullets, a hunch of that noble beef on your spit, and wine to overflowing. We celebrate good master... uh—"

"Martin, son of Fulbert."

"The good Martin's entrance as a bejaunus of Paris." Casually, as if it were an afterthought, he added: "Place the reckoning before Martin, son of Fulbert, mine host."

THE first lecture of Master Gerald of Cambray was filled to overflowing. Guy of Salisbury had seen to that. By cajoleries, by prompt seizures of newly arrived students in Paris, by wheedlings of friends, by forcible kidnaping of honest burghers who knew not a word of Latin, he had managed to create a respectable audience.

He felt quite satisfied with himself as he sat cross-legged on the straw in the very forefront of the room, right under the master's nose. The mingled odor of unwashed human bodies and damp, long-strewn straw tickled his nostrils. Precious parchment fragments lay on the auditors' laps, with quills poised above them to take down the master's words.

Gerald, seated on the only chair in the drafty room, looked half-frightened, half-sick. He had complained to Guy about the filthy rushes, had demanded chairs for his students. Guy had overruled him on both points. Item one—the expense; item two—it was against the regulations for Paris arts, candidates to be seated; it would tend toward luxurious sleep.

Cambray surveyed his audience and commenced in a quavering voice that grew stronger as he gathered confidence.

"My subject," he began, "is the science of astronomy. I am going to be frank. In my land and time... uh.... that is—" Guy frowned. He had. warned him against any mention of that insane delusion of his about having been catapulted back from a future age. But Cambray recovered himself. "What I meant is that there are far greater masters of this science where I come from. I am familiar only with the skirts of this knowledge. Yet what I have to say will be novel to you, and will doubtless upset many of your present concepts."

Quills had started to scratch. Students were taking him down in a species of abbreviated shorthand. Jean Corbin, cross-legged next to Guy, whispered complainingly: "He speaks with a vile accent. It's hard to understand him."

"In the first place," droned Cambray, "Ptolemy's Almagest, which is your text, is erroneous. The Earth is riot the center of the Universe. The Sun does not travel around the Earth, nor do the planets and the stars. Instead, the Earth is but one of many planets, all of which circle around the Sun as satellites."

Quills stopped sputtering. Shocked faces turned toward each other. A murmur rose like the buzzing of bees. Guy rocked on his heels. What the devil was this? He had never bothered to ask his protege what manner of astronomy he was going to teach.

He had assumed naturally it would be the regular, well-known facts. But this nonsense! The Earth going around the sun?

In the back of the room there was a rustle. A door banged. Someone had entered. Guy twisted his head and felt a sinking sensation in the pit of his stomach. Cecco of Vercelli, the great astrologer, stood grimly against the bare plaster, his lean face more hawk-like than ever; his dark eyes fixed upon the teaching master.

Guy turned again to see Cambray pause uncertainly, then take a deep breath and plunge recklessly ahead. "I hear your murmurs of doubt," he said, "and I can understand your incredulity. You have been brought up on Ptolemy's plan of the Universe as the final authority. No one has ever attempted to verify that plan for himself. You have no... ah... glasses that magnify and bring the planets closer to your vision. You haven't as yet the mathematics that would prove your errors.

"But I say to you, and in succeeding lectures I shall try to prove to the best of my limited abilities, that the Sun is a mighty ball of fire—a vast world so huge that thousands of puny planets like the Earth could fall into it and be burned to a crisp, like falling midges into a blazing furnace.

"In company with the other planets, the Earth circles the Sun. The other planets are worlds like ours; some of much greater dimensions. The so-called fixed stars are actually tremendous suns, at inconceivable distances from our own Solar System. Perhaps they, too, have planets like this Earth revolving around them."

Guy was making mechanical pigeon marks on his parchment—jagged marks that had no meaning. A horrible thought seized him by the hair. The man Gerald of Cambray was mad! He had smiled at his insistence on his travel in time as either the result of a knock on the head or a skillful attempt to achieve notoriety. But what he was now. saying was sheer blasphemy. And with Cecco—

A frozen silence had fallen on the audience. Even the damp rushes no longer stirred or crackled. Then came what Guy had feared—the grim, sardonic voice of Cecco of Vercelli.

"Pray, Master Gerald," he spoke suddenly, "you have denied for us the authority of that mighty father of our science—Ptolemy. Surely, for such an unheard-of daring, you have other equally might authorities. Who are they and what are their names?" The little man puffed up. His eyes flashed behind their peculiar glasses. The new-shaven tonsure made a bald, quivering spot in a vagrant wisp, of sunshine. "Authority?" he crackled. "That is the whole trouble with this age. Instead of seeking out the truth for yourselves, you are content with what others have said before you oh the subject. That is not progress, that is not the method of science. Ptolemy did the best he could with the knowledge and methods of his day. His conclusions were wholly erroneous. I could cite you authorities opposed to him, but you wouldn't know them from Adam. Because—" He stopped abruptly, and checked himself.

"You were about to go on," Cecco murmured politely. Guy did not like that smooth our in his voice. He knew the astrologer's reputation.

"I was about to say"—Cambray recovered himself—"that I believe I can prove these seemingly astounding statements to you."

"By the proper syllogisms?"

"Syllogisms be hanged!" Cambray retorted vehemently. "By proper experiments. The rotation of the Earth on its axis, for example. There is a way—let me think... uh... I have it—Foucault's experiment—something to do with a swinging pendulum tracing in sand the path of the Earth as it rotates beneath it."

"This Foucault is perhaps one of the fathers of our sacred Church?" purred Cecco.

"No—that is—" Cambray looked suddenly unhappy. "It's just a name," he ended lamely. "But I could perform it for you if—"

The astrologer gathered his purple robe around him. A queer sort of grin stamped his face. "It won't be necessary," he murmured, and walked out, leaving a chill behind him.

Cambray's eyes snapped fire. He squared his shoulders. "Now, messieurs," he said calmly, as if nothing had happened, "we shall proceed."

THE fame of his lectures grew. Nothing like them had ever been heard on Straw Street before. Students came to scoff, and remained to listen. That strange experiment, called Foucault's, had actually been performed to an excited audience. There, before their very eyes, an iron weight that tapered to a needle point, and suspended by a cord from the ceiling, made shifting turns in clean sand beneath. That was because, Cambray explained, the plane of a pendulum's vibrations always remained the same, even while the Earth was turning beneath it.

He made smoked glasses, and showed them curious spots on the face of the lordly Sun. He discoursed on the lordly stars; how they were aching billions of miles away. Stars disentangled themselves from the firmament at night, and fell to Earth. They claimed they were not stars, that they were bits of dust and lumps of iron that swam in space and were called meteors. The face of the man in the Moon—he who had blasphemed the Lord and had been transported thence for eternal punishment—Cambray maintained was actually a configuration of mountains, like the Alps that barred the way into Bologna and Padua. Worst of all, he ridiculed astrology and called it a delusion and a snare.

The sensation spread through all Paris. The halls of the other masters were deserted when Gerald of Cambray lectured. Fees poured in like a golden flood. Albertus Magnus, the Dominican, came once and took silent notes. Two doctors of theology sat frowning upon chairs, as became their dignity.

Now Guy of Salisbury was a brave lad. He would have thought nothing of flinging himself, dagger in hand, upon an armored knight armed with a sword. But this strange, intellectual audacity brought the cold sweat to his brow. It upset the ordered course of things. There was no room for God in such a frightening Universe as Cambray depicted; not only Ptolemy and Aristotle, but the sacred Bible itself was brushed aside.

Of course it wasn't true. Cambray was merely conducting a series of skillful intellectual exercises in philosophy. Syllogisms and propositions to display to the full the dazzling subtleties of argument, such as, for example, a theologic doctor had employed in the famous discussion as to how many angels could dance on the head of a pin.

Yet, as the days went on, Guy felt the uneasy sensation grow that Cambray was utterly sincere. On several occasions he tried casually to bring the errant master to an admission that it was all mere clever argument, but the little man looked at him with such a pained expression in his owlish eyes that he did not press the point further.

Guy's purse was filled now with his commissions on the students he had brought, but he was not happy. For one thing, he had grown fond of the strange little man; for another, things were progressing too smoothly. It was true that so far there had been no trouble. The students flocked and took diligent notes, instead of stamping and whistling derisions as they had done on occasion, even with Albertus Magnus himself when he spoke of the properties of certain plants in contradiction of what Aristotle had said concerning them.

The nations spoke privately among themselves about this heretical master, but did nothing. The Bishop of Paris had not been heard from. Nor had the papal legate, then in Paris. Even Cecco of Vercelli, whose very lucrative trade as a prognosticator had been cut into severely since the arrival of Gerald, seemingly did nothing.

It was this last which worried Guy more than anything else. Cecco was not the man to submit tamely to such a state of affairs. And, remembered Guy with a shiver, he had foretold Gerald's death within a month of that fatal day in the tavern. Only a week now remained!

The master's subversive lectures had not been interfered with because the energies of the university were just then engrossed in a mighty struggle with both king and bishop. The king, it was well known, was furiously angry at the slaying of his provost, and had refused the demand of the university that those of the guard who had escaped should be delivered to it for punishment.

The bishop, secretly envious of the tremendous power of the university, had sided with the king. Whereupon the enraged students and masters had posted the bishop all over Paris, on tavern walls and on churches, on brothels and on barber shops, as "an arid, rotten and infamous member," and that his family would be such even to the fourth generation.

Thus made a mockery, the bishop retaliated by stirring up the populace of Paris to an assault upon the proud and privilege-swollen university. The populace needed but little encouragement. The burghers of Paris hated the swaggering students and masters. They remembered insults, riots, armed invasions of homes by drunken lads, throwing of itching powders down their backs while engaged in seemly worship, and a thousand other arrogant and cruel pranks.

The narrow streets buzzed with excitement and hate. Peasants from the country round poured in, armed with clubs and staves. Cecco, though himself a master, was seen. closeted with the bishop, and whispered at length to the king. When he returned to Straw Street there was a curiously contented smile on his dark countenance.

SOMEHOW the name of Gerald of Cambray began to be bandied around in the crooked byways of Paris. Whispers arose and spread like wildfire, started no one knew whence. This Cambray, who taught strange doctrines at the university, was a warlock, the devil himself come in mortal guise to wrest their souls away from the blessed Lord. He was a heretic, a follower of the damnable Averrhoes, a perverter of sacred things. He claimed, it was whispered in shuddering circles, do have come back from the future; he claimed that there was land on the other side of the ocean, when everyone knew only purgatory reared its mountainous height in the antipodes. Yet the university sheltered him. Destroy him and the heretic university as well, said certain men, and scattered to say it elsewhere in fresh company.

Guy caught one of these slinking emissaries at his task. He entered La Trovisse-Vache to find a swirl of drink-flushed ragamuffins hearkening to a man he had never seen before. The man had a dark, Italianate face and was haranguing the smock-clad yokels from the top of a table.

"The good Lord is displeased with you," he thundered. "A curse is about to be visited on you and your city for harboring that vile perverter of all things holy.in your midst. I speak of Master Gerald of Cambray, limb of Satan—if he be not Beelzebub, himself. Destroy him, and save yourselves from, destruction."

Anger surged through Guy. The whole damnable mess became suddenly clear. Cecco, the astrologer, was in back of this. He had sent out emissaries to stir up things.

The tavern subsided, into deathly silence as Guy strode forward. The man saw him coming. He scrambled hastily from the table, his hand whipping inside his jerkin. "There's one of the university," he screeched. "Get him, kill him!" Then cold steel flashed in his clenched fingers.

Guy caught him a terrific clip on the side of the jaw. The man screamed once and flew in a long flat arc across the tavern to fall into a crumpled heap among a shattered glaze of earthen pots.

The young giant rubbed his skinned knuckles thoughtfully. "Anyone else wish the like?" he demanded. No one stirred; those on the outer edges began inconspicuously to fade through the doorway. The man lay just as he had fallen; moaning, mumbling through a broken jaw.

"Give me some wine, rascal!" Guy; ordered the trembling innkeeper. A flagon was hastily brought him. He tossed it off and strode out, leaving a hush behind him!

On the fifth day, however, the storm broke. The university had known it was brewing, yet characteristically did nothing. Pierre of Normandy, the rector, laughed at Guy's warnings. "That canaille!" he declared contemptuously., "They know from. bitter experience what would happen if they dared attack us." Then his face grew grave. "But a word with you, Guy, now that you have brought it up. I fear me that we have permitted your friend, the stranger who pretended to a license from a nonexistent Studium to go too far. The papal legate has just made representations to me. He maintains that the doctrines he teaches under the guise of astronomy are false, heretical and schismatic. A report of one of his lectures, taken verbatim, has just been sent to His Holiness for investigation. He wanted me to yield him to an inquisition for trial."

The blood receded in Guy's veins. He had been expecting something like this for a week now. "What did you tell him, Pierre ?" he demanded anxiously.

The young rector drew himself up proudly. "Naturally I told him that I wouldn't think of it. Gerald of Cambray is a master of the university, a duly elected member of the English nation. As such, he is under our protection and entitled to our privileges." Then he shook his head. "However, his teachings are suspicious. The faculties meet the day after tomorrow. We shall come to a decision."

The faculties never met. For, on the following day, as night yielded to thin streaks of light in the east, the Paris populace struck.

Guy awakened to shrieks and howls and bloodthirsty cries. He bounded from his pallet of straw, shook his fellow sleepers fiercely. "Wake up," he cried. "There is a riot."

Jean Corbin yawned, rubbed his eyes, grunted: "Eh, what's that?"

Gerald of Cambray got up quietly and began to dress. He was naked as the day he was born, and his thin, shrunken body looked doubly ridiculous. Guy and Jean had found this a source of infinite, if polite, amusement. Whoever thought of stripping to the skin when one slept? In the first place it was cold; in the second, there was all that effort gone to waste. One undressed in order to dress again. It was senseless. All they took off at night were their shoon and tabards. But they couldn't persuade Gerald, any more than he could persuade them to shiver and splash in a basin of cold water, laboriously carried into their garret every morning.

"I said there was a riot," repeated Guy, shrugging into his tabard and buckling on his illegal sword.

Gerald carefully put on his lenses over his nearsighted eyes. "I am to blame for it," he said quietly. "I should have known better than to teach what I did in this age. Knowledge should come only when the times are ripe for it. Otherwise it is dangerous."

"Nonsense," Guy told him. "The rabble erupt like this every so often, and get their skulls bashed in as a result."

Jean fingered his knife. "There are more than the rabble this time, Guy," he said. "Hearken!"

The streets echoed with running feet. Shouts mingled with the clash of arms. Horses' hoofs pounded. "The king's men-at-arms!"

"They want me," said Master Gerald tonelessly. "It is all my fault. Let them have me, Guy. Perhaps they will go away peaceably then."

"And shame the university forever?" roared the Englishman. "Never? Come on; they have fired the hall of the Picards."

Through the open window they could see the first flick of flame as it lifted from the wooden structure on the outermost verge of Straw Street, just where the Seine made its sluggish way under a wooden bridge.

Gerald caught up a stout club. They catapulted down the rickety stairs, brushed aside a frightened burgher and his wailing wife clad only in long, gray undergarments, and dashed out into the street.

They found themselves in a shambles of running men and boys—students and masters inextricably intermixed. Forbidden swords showed in abundance; knives flashed; some had pikes, some cudgels; others, finding no weapons, carried huge stones in their fists.

"Guy of Salisbury," they shouted joyfully to the blond young giant. "Lead us!"

"Up, university!" he cried, brandishing his sword. "Up, nations!" They poured after him in a growing mob, as every house, every brothel, every tavern yielded its crew of reckless youngsters.

The noise and confusion grew ever louder as they raced toward the huge wooden barrier that blocked Straw Street from the lay world without. The flames crackled and roared from the hall of the Picards. Oaths and blows and the grunting of conflict mingled in fine confusion.

Guy leaped the barrier, hurled forward. Behind him came a press of determined men. They found madness ahead. The narrow street swarmed with burghers and apprentices, dancing and roaring, shrieking objurgations on the hated university. Butchers, bakers, tanners, blacksmiths, armorers, linen drapers—all the guilds of Paris—armed with staves, clubs, hammers, knives; peasants from the surrounding fields with pronged pitchforks and wooden plowshares, armed retainers from the Abbey of St. Germain with iron-tipped staves, bows and arrows and clubs; and beyond, the horsemen of the king's chamberlain, helmeted and wielding great broadswords.

"Death to the clerks!" ran the cry through them all.

They were having great sport. Those unlucky university men whom they had caught unawares were running aimlessly back and forth, screaming for help, baited and torn at every step. A young lad, not more than fourteen, with tear-streaked face, was pounded down into the mud by a laughing horseman. A grave canon doctor, tragically ludicrous in skintight breeches and nothing else to cover his nakedness, thrust up his arm to avoid a storm of blows. A butcher, bloody with the night's slaughter, brought his poleax down with crushing, force. The doctor's arm snapped like a reed, head and skull spread in a smear. Then he was trampled over by the howling mob.

Guy heard Gerald's sobbing intake of breath beside him. Surprised, he turned his head. "What, you here?" he cried. "Get back! They'll tear you to bits!"

The little man's teeth chattered, but his lips were drawn tight. "The... the beasts!" he sobbed. "The vile beasts!"

Then the rush of men behind them swept them on.

With a huge shout, "Up, university! Down, gutterers!" Guy plunged into the seething maelstrom. In an instant Straw Street was a bloody shambles.

GUY slashed down upon the butcher. The broad red face disappeared with a howl of pain. An iron-tipped stave ripped his side; he caught the wielder a glancing thrust over the. arm. The shrieks of the wounded, the groans of the dying, rose on every side. From the overhanging buildings furniture, pots, boiling water, stones dropped in fine disregard on friends and foes alike. The horsemen of the chamberlain charged, battering down their own allies in order to get at the clerics.

But the clerics were adept at this sort of street fighting. At a warning cry from Guy they flattened against the walls, dived into open doorways.

As the heavy horses thundered down the crooked street, impeded by their own numbers, weapons darted out, cutting and slashing at the heaving flanks, hamstringing tendons and bringing the squealing animals to the ground. Then they darted out again, thrusting with dagger and sword at the armored men as they strove vainly to disentangle themselves from stirrups and reins.

The fight raged back arid forth. Guy was arm-weary, leg-weary, sodden with blood. Yet his mighty arm rose and fell like a flail, and with a flail's terrible effect. Sometimes he caught a fleeting glimpse of the master from another time. The little man had turned into a screeching demon.

His glasses were askew on his narrow nose, the straggly locks that rimmed his pate were wild and disheveled, and his voice rose in a thin, piping scream as he wielded his bludgeon.

But the numbers of the invaders were beginning to tell. Fighting desperately, disputing every twist and turn of the street, the university was being relentlessly forced back toward the slimy banks of the. Seine. In a few minutes they'd plunge in.

Suddenly there came the sound of music. Horns and trumpets and flutes. As if by common consent all fighting ceased, and all eyes turned toward the source of the sound.