RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Science Fiction, April 1938,

with "Negative Space"

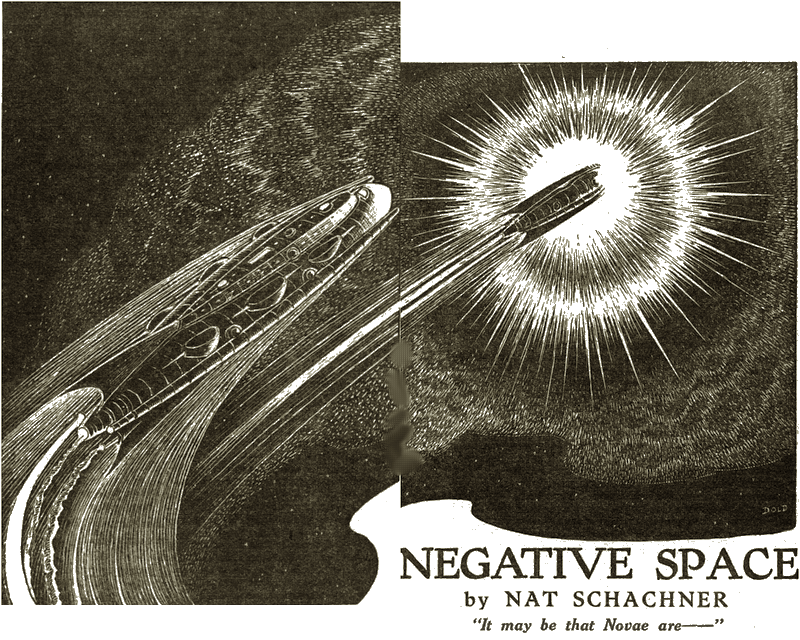

Desperately the Arethusa's blasts roared out, wrenching her

stout fabric—slowly she turned from the fire-fly area of annihilation...

SPACE COMMANDER Dan Garin spraddled his big-thewed body before the forward observation port and scowled blackly out into space. He did not look at his two companions in the tiny control chamber. His gusty face and gustier beard, its coal-blackness unstreaked with the slightest gray, were twisted in half-humorous bitterness.

"By the Beard of the Comet," he roared suddenly, "I'm getting fed up with this silly patrol duty and sillier transportation of distinguished space-tourists from one end of the Solar System to the other. I'm a fighting man, and the Arethusa's a fighting ship. It ain't natural for us to shuttle back and forth like brood hens clucking over blasted little chicks. I think I'll ground me and spend my declining days in the Martian pulque-caves, mumbling over my drink and telling tall tales to the gaping tourists."

"And a good many you'd have to tell, Dan," said Jerry Hudson affectionately, settling his slighter form more comfortably into his chair. His keen, gray eyes glinted with amusement. "What poor Dan actually means," he explained to the other passenger with becoming gravity, "is that within four days more, one Sandra Stone will be landed on Callisto to join her father, James L. Stone, General Manager of Callistan Mines, and that one Jerry Hudson, by devious methods known only to himself, wangled a new research unit on the aforesaid Callisto, with the sole and nefarious purpose of dwelling in close juxtaposition to the said Sandra Stone, thereby assuming an unsportsman-like advantage over that once scourer of the spaceways, that terror to now extinct pirates, Danny Garin."

"Be careful, Mister," warned the girl, puckering up very kissable lips in the process. She was slim as a young willow, with all of its pliable grace. Little wrinkles of laughter sprayed over her fresh young face, but there was understanding and some pain in her blue eyes. "You know the ancient saying, 'Absence makes the heart grow fonder!'"

Dan Garin swung his burly, powerful body around, glared savagely at the younger man. "Why, you young squirt," he rumbled, "just because I'm an old, worn-out, simple space-man, and you're the best damn scientist in the entire System, and a good-looking pretense at a man to boot——" He grinned suddenly. "Maybe you're right, Jerry. Sandra and you'll make a swell couple—with youth, looks, brains and the universe before you. I'm old enough to be her father, and a crabbed space-bachelor besides." He held up a big hand to stop Sandra's little cry of protest. "It really ain't that so much," he muted his roar. "It's just that I'm getting bored, rusty from disuse. The spaceways are just as placid and as disgustingly safe as the tunnel back on Earth under the Atlantic Ocean. Look out there!" He pointed through the observation port at a snub-nosed freighter, pitted with meteor scars, coasting bleakly against a star-strewn backdrop at an unhurried twenty miles per second.

Jerry nodded briefly. "She's Callisto-bound as well as ourselves. Carrying colonists and their families for the mines, and due to return with a heavy cargo of polonium and iridium."

"Sure!" Dan scowled. "And as safe and placid as a canal scow. A few years back, things'd have been different. There'd be a black-dusted pirate ship hurtling toward her—colonists bring good ransom, and Callisto metals run' the Solar System—and I'd be breaking out my space-tubes, yelling orders into the visor. Blue bolts of energy'd flick out across the void—there'd be swift maneuvering to avoid rocket torpedoes—all spaced crackle with the heat and flame of combat—then a direct hit, and pouf! you'd be blinded with the dazzle of the explosion." He sighed heavily. "Those were the good old days!"

"I really believe," protested Sandra with humorous indignation, "you're half pirate yourself, at heart."

"For ten thousand years," observed Jerry calmly, "men have bemoaned the good old days and thought all danger, all daring adventure past. You're an anachronism, Danny. Besides, it is your own fault that the spaceways have become dull and monotonous. Who was it finally located the pirate lair within the hollow shell of an inconspicuous asteroid and blasted them all into a billion fragments?"

Dan Garin shook his black-tousled head gloomily. "To tell you the truth, I'm sort of sorry I did it. Now there's nothing but——"

"What a queer effect!" Sandra said suddenly, her eyes fixed on the observation port. "I wonder what it is."

Both men turned to the magnifying crystal, stared. Silence descended in the little control chamber. The ship seemed suspended in a limitless void, without life or motion. Yet Jerry knew they were coasting along with the rocket tubes shut off at a swift two hundred miles a second.

Outside, to the extreme left, Jupiter was a belted orb, with the great mysterious Red Spot a splash of color across its surface. Three of its moons clung to its sides, tiny pinpoints of light. The farthest out was Callisto, their destination. A sizeable Earth-colony was already established on its bleak terrain, mining the precious heavy metals that furnished atomic power for rocket blasts and the mighty engines of Earth and Mars.

Involuntarily Jerry's eyes swung to the right. The stubby freighter was making its placid way, steady, unswerving. Its twenty miles a second seemed but fixity in space to the swift flight of the Arethusa. The detector-unit showed its distance to be approximately 100,000 miles. At their respective rates of speed, Jerry figured, it would take only about ten minutes for the Arethusa to overhaul it.

Then his gaze held. He heard the quick suspiration of breath of the black-bearded captain. Beyond the freighter, directly in front of its course, the normal star-powdered backdrop of space seemed to have gone haywire. Tiny flashes of light, microscopic puffs of flame, flared up with explosive suddenness, winked to extinction with as startling rapidity, spangling the jet blackness of space as far as the eye could see.

"It's like an enormous swarm of Earth fireflies," gasped Sandra.

THE simile was most apt. Those tiny flickers that went on and off like ancient electric light bulbs worked by a manual switch, were like nothing so much as dancing fireflies on a sultry evening in June. But there were countless trillions, and they swarmed in interplanetary space where no life could exist!

"By Deimos and Phobos!" swore Dan, "what would you call that, Jerry? A new type of aurora?"

Jerry was already on his feet, eyes narrowed. "Nothing of the sort," he said swiftly. "You can't have an aurora without gaseous matter. And there's no meteor dust or cometary clouds in that sector of space. The interplanetary surveys have mapped them pretty definitely. This is an entirely new phenomenon—something that——"

A hopeful light transfigured Dan Garin's scowling face. "Now look you, Jerry lad," he demanded with a certain eagerness, "you wouldn't be thinking that it's pirates' work—some newfangled device by a new-fangled band?"

"Don't be silly, you old pirate-hunter," grinned Jerry. "No band of pirates in the universe could create that effect. Why, it's about 50,000,000 miles in diameter, I'd say."

Dan sighed gustily. "Then what the hell!" he groaned. "It ain't my business. It's meat for pallid scientists like yourself, my lad. Go ahead. Study it, write it up, get yourself a medal for discovering a bunch of loony fireflies lost in space——"

"That freighter is heading straight into it!" Sandra exclaimed.

"Won't hurt it any," growled the captain. "Its hull's platino-duralumin alloy, insulated against every conceivable electrical or magnetic effect. Even meteors——"

"I wouldn't be too sure of that," Jerry's voice whiplashed. His keen, tanned face had suddenly become tense. "Whatever it is, it is something entirely new, something the solar system has never encountered before. It's come from the depths of outer space." He flung swiftly around, his speech crackled. "Quick, Danny! Signal the freighter before it's too late. Warn them to swerve, to apply their rockets full blast."

Captain Garin narrowed his eyes in surprise. "You're crazy, man!" he expostulated. "To get away now, when they're so close and coasting without power, would wrench every last hull-plate loose from its moorings and just about ruin every colonist's digestion on board."

Jerry swore. "Let 'em take that chance," he jerked out. "Don't you understand? It's a matter of life and death!"

Dan did not understand. But he knew Jerry Hudson, and, like a good commander, knew when to obey without asking too many reasons.

Without another word, he hurled for the control board, snapped on the visor. S-N-T! S-N-T! The space urgency call sputtered across the intervening void.

A bare 2500 miles now separated the lumbering cargo ship from the edge of the dancing fires.

Back came the reply, growling sarcastically out of the sono-tube. "Hello, Arethusa! Captain Greer of the Mercury talking. What's the matter? Need any help from a good boat?"

The veins swelled on Dan's dark forehead. "No, blast you!" he roared so that the control chamber shook. "I'm handing out orders. Cut in your entire battery of forward landing rockets; blast on every starboard tube. Swing to port in the sharpest arc you can; do not enter frontal area of flashes until we investigate."

A SINGLE moment the sono-tube was silent. Then, coldly, "Have you gone crazy, Captain Garin? You may be on patrol, but I'm running the Mercury. D'you think I'm going to ruin my ship on account of a lousy corona effect? So long, chicken-heart!"

Dan Garin choked. No one had ever dared talk to him that way before. Was he slipping? Had his name been forgotten in the last five years? "Listen, you white-livered son of a dog-faced Plutonian!" he yelled. "I'm handing out orders and you're taking them! Blast on your tubes, or by all the asteroids——"

A single word spattered out of the sono-tube, short, sharp, and to the point. A word of great antiquity.

"Nuts!" said Captain Greer.

"It's too late, anyway," breathed Sandra tautly.

The snub-nosed freighter coasted steadily on, direct on its course. It swerved neither to the right nor to the left. Then it immersed, head on, in the scintillating bath of little flashes of light.

A moment the ship silhouetted blackly against the flickering background. Tiny puffs of evanescent flame, measurable distances apart, harmless-seeming as summer lightning.

"Why, nothing's happening!" Sandra exclaimed. There was relief, mingled with an odd disappointment in her tone. Jerry had been wrong——

Captain Dan Garin scowled blackly. His beard bristled—a sure sign of inner volcanic wrath. Not only had Greer mocked him with vigorous language, but Jerry had let him down. He would be the laughing stock of the System when this got around; he would——

"Look!" said the young scientist, mouth a straight, hard line.

The hull of the Mercury had illumed suddenly with lambent blaze. St. Elmo-like fires raced and flashed over its pitted surface.

"What the hell!" rasped Dan angrily. "That ain't nothing. Even that blasted tub can take an electrical disturbance. You've let me down; you've——"

The flickers of dazzling light seemed to coalesce. There was a blinding surface flash, followed instantly by a furious explosion. The Mercury seemed to vanish in a spouting, geysering inferno of seething flame. The interior of the control chamber on the Arethusa flared with molten light.

Sandra cried out, threw her arm over her eyes to shield them from the searing blight. Captain Garin, with a strangled oath, stumbled blindly toward the control board, groped for the switch that controlled the helioscope filter. His fingers found it, closed.

The screen that made it possible for space-voyagers to look directly at the sun fell smoothly into place. At once the insupportable glare died away; a soft-toned, polarized illumination filtered through the chamber.

With horror in their hearts, they stared out at the gigantic cataclysm. A great shell of dazzlement shot out from the doomed ship, expanded, died down to abrupt darkness. A huge sphere of intense black made a hollow void within the flickers of innumerable pinpoints of flame.

But within the hollow shell a curiously shrunken Mercury—a collapsed miniature, correct in every proportion—blazed furiously. Even through the helioscope filter the glare of its molten wrath was almost unbearable. Jerry, sick at heart, calculated that fiery core at millions of degrees of Earth temperature.

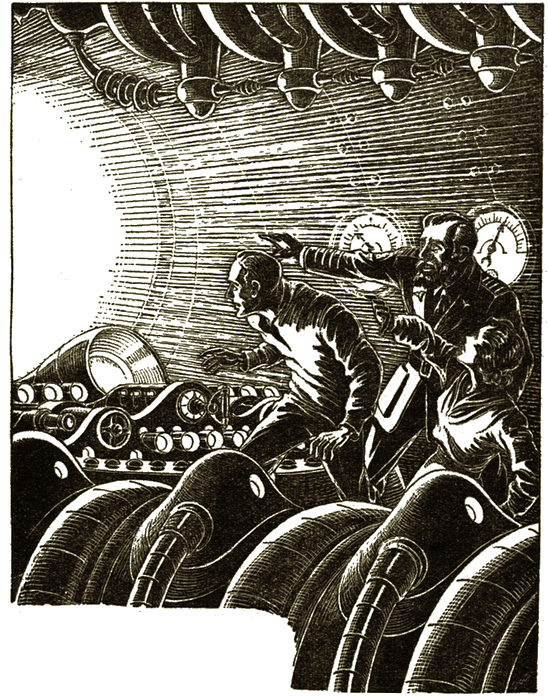

Even through the helioscope filter, the glare

of Mercury's vanishment was unbearable.

Then, while they watched speechless, unable to move, the tiny ship fell inward upon itself, fused to a molten meteor—a single point of flame within a shell of dark quiescence.

"THOSE poor people on board!" whispered Sandra, eyes wide with pain.

Her words released a trigger in the Captain's dazed mind. With a bull roar of rage he sprang for the rocket controls. At a touch, red fires licked out of the drive tubes; the armored ship leaped forward, pulsing and thrumming in every welded seam.

"Here, what are you going to do?"' Jerry cried in alarm.

"Do?" snapped Dan, a terrible look on his face. "Dive straight into that hellfire and get the blankety-blank pirates that thought up this new stunt."

Jerry whirled to the observation port, aghast. The ship was accelerating to 500 miles per second; they were rushing headlong into the mysterious spangle of space. In another two minutes——

It was too late to argue with Dan. His single-track mind was obsessed with pirates. There was only one way to avoid immediate destruction! In a single bound he was at the controls, punching feverishly at the buttons.

"Hey!" shouted the Captain.

The next moment he fell crashing against the side, barely missing Sandra as she flattened to the wall with inertial pull. Jerry clung desperately to a stanchion, swinging like a pendulum to the tremendous shift in pace and direction.

But even as he was hurled to the floor, his haggard eyes sought the observation port.

The staunch spaceship groaned and twisted with tremendous torque. The hull-plates creaked and crawled. The port rockets thundered in mighty unison, belching great tongues of fire into the void. The atomic engines heaved and buckled. Supplies slid from side to side within the hold. From the crew quarters came cries of alarm, the thud of slamming bodies. Never before had the spaceship been subjected to such a sudden, close-angled shift in course.

Yet still they hurtled on, held in the grip of a mighty initial acceleration, toward that ominous dance of glittering fireflies. They were turning, yes, but would they bank in time to avoid the annihilation that awaited them within that innocent-seeming spectacle?

Jerry whipped back unsteadily to his feet. His throat was a dry constriction. He had no illusions. If the Mercury had pulsed to fierce destruction, no power in the universe could save the Arethusa from a similar fate. Closer, closer! All space was swallowed up by the vast-reaching flashes of light. Jupiter was gone, its clinging satellites; the stars were obliterated in their courses. Only an endless panorama of evanescent sparkles, and the deadly spectacle of a collapsed freighter, glowing like a nova within a curious shell of moveless black.

Nova?

But even as his brain clicked on that casual simile, the cry that started in his throat died stillborn. From behind he heard Sandra's moan of terror, Danny's curse.

They would never make it. Already it seemed that they were within. In front, to the port, rocket tubes smothered and roared, but—the queer little explosive puffs surrounded them.

"Sandra!" he called in sudden despair. "It's all over. We——"

THEN, with a whoosh and a last desperate swerve, they cut in and out again, careening on a runaway tangent, back toward the asteroid belt.

Captain Garin hurled his powerful body toward the controls, sweated and cursed as he sought to bring the rocking, reeling vessel back to normal.

"You young idiot!" he howled at Jerry, "you've ruined my fighting ship! You've sprung open every seam, I'll be bound. And you stopped me from getting at the blasted beings responsible for Greer's annihilation—God rest his soul!"

Sandra picked herself up from the floor, her face still pale with the shadow of averted death. "But, Jerry," she cried shakily, "we were inside, and nothing happened. Are you sure——?"

The young scientist was not listening. His eyes glowed with the light of discovery. He snapped his fingers. "I've got it!" he exclaimed.

They stared at him as if he had gone suddenly insane.

"Got what, Jerry?" the girl asked gently.

"The connection. What happened out there to poor Greer's ship is the same as that which happens in galactic and extra-galactic space when a nova bursts forth."

Dan shook his massive head pityingly. "The strain was too much for him," he muted his voice for Sandra's benefit. "We'll get him to Callisto as fast as possible where he can receive proper medical attention."

"You'll do nothing of the sort," Jerry snapped fiercely. "We're not going to Callisto yet—perhaps never. If what I think is right, the Solar System, or major parts of it at least, is doomed."

"Doomed?" breathed the girl incredulously.

He repeated the word with a quiet despair. "Yes; doomed! If that visitant from outer space"—he pointed to the still flickering depths where the Mercury was a fast receding furnace—"is what I think it is, then we have bumped unwittingly into a space-structure that is responsible for the apparition of nova, of sudden-blazing stars. Suppose that area contacts a planet, contacts the sun itself. Well—you saw what happened to the Mercury. Think of the same flare-up on a gigantic scale, with the sun as the center. All the planets would melt away in the tremendous outburst, like particles of ice in a rocket-tube blast."

Dan snorted in his black beard. "You're a swell scientist, Jerry lad, but this time you've addled your own brains. You mean to say that when a star suddenly acts up way out in Andromeda—explodes, so to speak—that it's because it ran into a bunch of blooming fireflies like out there?"

"Exactly!" Jerry retorted. "Astronomers have never been able to figure out an adequate explanation for the appearance of a nova. They theorize about collisions between two stars, about the tidal pull between close-moving suns, about the frictional passage of a star through a nebula, about some mysterious sudden release of energy within the core of the bursting body. But none of their hypotheses has fitted all the facts. This new phenomenon into which the Mercury ran, does!

"There was the same swift expansion, of a brilliant shell of gas, the same absorption into a dark area, and the final retraction of the blazing core, to gradual extinction or inconspicuousness."

IN spite of themselves, the others were impressed. There was a logic to it, and they had witnessed with their own eyes——

"But what is this mysterious influence in space?" Sandra asked with a sharp intake of breath. She was thinking of her father, kindly, gray-haired, out there on Callisto waiting for her, waiting for the Mercury with its cargo of colonists. Involuntarily her eyes strayed to the observation port.

Already the blaze that had been the hapless freighter was dying down. Already the glittering sparkles had swept between them and their destination. Callisto and all the outer Solar System was cut off from the inner planets, from Earth.

"That is what we must find out at once," Jerry answered grimly. He spun on his heel. "Look, Danny! Swing the Arethusa around, head us back to that damnable mess, while I set up some test instruments. Every second counts. Every second represents the irrevocable loss of a faint chance to save our System from impossible disaster. But as you value our lives—and the safety of billions of people—keep out of range of those sparkles."

Captain Garin tugged at his black beard. A somber glow smoldered in his dark eyes. "I still think you're haywire," he growled. "I still think there's living beings in back of this; whether from this System or from some unknown star, I don't know. But I'll give you a chance, lad. If you fail——"

The next hours were fraught with unbearable tenseness. While Dan swung the Arethusa back on its tracks, hurtled once more for the ominous phenomenon that had strangely intruded itself into the spaceways, Jerry feverishly carted up from the hold the apparatus which he was shipping to Callisto for his new research laboratory, set up his instruments, tightened connections, adjusted, tested.

Sandra helped him—she had worked with him on Earth—her lovely face pale, but brave. Only once did she ask the question that was tearing at her heart. "Do you think Callisto—is—safe?"

Jerry straightened, looked at the girl he loved, said gently, "I don't know, darling, yet. I'll have to check the size of this space-disturbance, determine its velocity, its direction. Until then——"

He bent to his work. He did not want to tell her all the truth—that he was desperately afraid that no part of the System would survive the impending cataclysm.

"O.K.!" roared Dan, as the ship swerved from its headlong course like a racing thoroughbred to the pressure of its rider's knee. "We're running parallel, exactly 10,000 miles away. Get going, lad."

"I'm ready," Jerry responded quietly. He turned immensely delicate ammeters and voltmeters on the evanescent flashes, switched contact. Then he stared. The sensitive needles, shielded from all known influences, did not move. "Damn!" he swore, puzzled. "There isn't the slightest evidence of electrical disturbances." Frowning, he tried next for magnetic effects. There were none.

"But there's plenty of light," Sandra protested.

"Of course there is," he answered impatiently. "Light is a concomitant of practically all energy transformations that include the requisite wave lengths. But it is usually a secondary, not a causative phenomenon. However——"

HE set up his light-wave traps, adjusted his spectroscope, attached his Hallam-Geiger counters. "There are photons, of course, as is natural. It doesn't mean anything——" He leaned forward suddenly, stared eagerly at the automatic count of all energy intake on the admission disk, frowned furiously at the clicking count at the end of the trap where only pure photons could penetrate.

"By all the Martian gods," he swore in amazement, "this is unbelievable!"

"What is?" Dan Garin wiggled his black beard in Jerry's direction. His eyes still burned on that sparkling space with which he kept the ship skillfully in pace.

"Why," Jerry gasped, "the count on both is exactly the same."

"So what?" Dan snorted. He was a grand fighter and navigator, but he was not long on science.

"This! That phenomenon which has invaded our system is pure light—nothing else. There is absolutely no trace of any other energy content that I can determine."

Silence held the chamber a moment, broken only by the muted roar of the firing rockets. Then Sandra gasped. "It's not only unbelievable, Jerry, it's impossible. The Mercury didn't explode and blaze to extinction simply because it ran into light waves."

The young scientist ran nervous fingers through his hair. "I wish I knew the answer, darling," he said.

"Another thing, my lad," growled Dan. "What's making that light? I've been watching them there little fireflies till my old eyes are smarting. First there's nothingness—the regular black o' space. Then suddenly there's a blast of light. Then there's nothingness again. And never twice in the same place, Jerry boy. Once it's winked out, that spot stays dark."

Jerry said sharply: "What's that? Repeat what you said—every word!"

Dan repeated his observation, bewildered.

For a moment they could almost see the swift, keen machinery of the scientist's brain in action, then he let out a whoop. "By Ceres and the Rings of Saturn, I think you've put your finger on it."

"On what, Jerry?" asked Sandra.

But he was not listening. He had become a whirlwind of vital energy. He raced among his apparatus; his fingers fairly flew as he set up new tubes, placed a pinch of white powder within a lead-shielded chamber, pointed its orifice at the observation port.

"Artificially activated polonium salts," he explained rapidly. "A splendid source of beta-rays, or electrons to you."

"I see," nodded Sandra. "You're going to shoot a stream of electrons into those light photons. What will that prove?"

"I'm not shooting them into the photons," he corrected. "I'm shooting them into the space in which the photons are seemingly born. If it will do what I think it will—but watch!"

The powder began to glow under the activating bombardment. Little light dartles spattered along the tube. Trillions of electrons converged along a magnetic path, ripped through the glassine port as though it were not there, shot out with inconceivable velocity into space.

A grim tension filled the chamber. Three pair of eyes held to their invisible path, sought that far-off glitter where the focused pointers declared that the electron bombardment would strike.

OUT there, at the apex of the invisible stream of hurtling electrons, at the point of contact with the space-intruder, light blazed up suddenly. Light of an order comparable to that which had flared up from the hapless Mercury. Light which seared their eyeballs even through the filtering helioscope. No longer were there solitary photon flashes per. cubic inch. A solid wall of brilliant energy lashed out, beat against the plunging ship with a perceptible jar. The light-wave trap recoiled from the blow—the Hallam-Geiger counters could not take the load.

But still the activated polonium sent out its countless streams of electrons, set automatically upon that given spot, 10,000 miles away. In seconds, a pocket of utter darkness took the place of the flame of light. But deeper in, new fires commenced.

"Like a powerful stream of water that's washed away loose soil, and is attacking deeper layers," Sandra whispered in awe.

For the first and last time in his life, Captain Garin looked aghast. "For God's sake, Jerry lad," he husked, "turn the damn thing off. I'm scared."

The young man's eyes glowed fiercely—glowed with the thrill of discovery and with a strangely commingled fear. Swiftly he clamped a heavy lead shield over the electron-gun, switched off the power.

"Well?" demanded his two companions simultaneously.

The fear dulled the glow in his eyes. His face grew ashen. "It's incredible,"' he said slowly, "yet Dirac, that ancient mathematician of the twentieth century, postulated wiser than he knew."

"Never mind the details, lad," growled Dan. "Let's hear the worst."

"The details are important," Jerry replied with quiet intensity. "Dirac theorized from his differentials that space as we know it—the space of the Solar System, of the outer galaxies as well—was a continuum, a featureless energy continuum. But his equations also demanded that in certain instances, holes would develop in this space—pockets, depressions, whatever name you wish to give them—in other words, negative energy levels."

"Of course," Sandra cried out. "You mean positrons."

Jerry nodded gravely. "I mean positrons," he agreed. "But hitherto positrons, or negative energy states in space, have been among the very rarest of phenomena. Whenever, in our planetary laboratories, we managed with much exertion to create these positrons, their life-existence was extremely short."

"Huh!" snorted Dan. "Even I, an ignorant old space-navigator, know that. There'd always be free electrons running around loose. They'd meet up with friend positron, and the electron, of opposite electric charge, would sort of fall headlong into the positron hole, and—bang—both of them would annihilate each other, to vanish in a flash of photon energy." He started. "Hey, Jerry! You don't think——?"

"I don't think; I know it!" retorted the scientist. "My tests were conclusive." He flung his arm out at the observation port. "We are witnessing something never before seen by man: not merely a single positron, of infinitesimal dimensions, but a mighty congeries, a vast "positron" that is over 50,000,000 miles in diameter! In other words, a tremendous hole in space, a sinister negative energy level. Look what happens! As electrons hit these negative states—negative, that is, in space, but actually positive to our arbitrary attribution of a negative electrical charge to electrons—the charges annihilate each other, and emit photon energy in the process. That is what happened to my electron stream; that is what happened to the Mercury. Every outer orbit electron in its composition was stripped away, the corresponding emissions of energy at such infinitesimally close quarters disrupted even the close-held electrons in the nucleus, and the atoms literally exploded. Our ship was saved from a similar fate because, during the mere seconds we were immersed, our rocket gases took up the load, and flashed first to extinction."

DAN'S eyes bulged as he looked out at the tremendous panorama. "But if matter is required to set off that super-positron, why does it keep on exploding all the time?"

"You forget that so-called empty space is not actually empty. It has been calculated that there is, in fact, about an atom to every cubic centimeter in the so-called emptiest portions of interstellar space. Conceive, then, of these vast holes scattered throughout the galaxies. They sweep up the free electrons, flash out light messages—perhaps even some of the nebula as yet unanalyzed by our spectroscopes are, in fact, positron hordes——"

"But in the course of millions of years," Sandra protested, "they should have swept up enough electrons to annihilate themselves."

"You forget," Jerry pointed out, "that the average of one electron per cubic centimeter is almost infinitely small. The time element must be of the order of countless trillions of years to do what you suggest. But when a floating negative state, or positron bubble, should happen to meet up with matter in the mass—like a star Well——a nova results, a frightful cataclysm."

Sandra caught hold of his arm suddenly, clung to it. "And you think," she whispered, "that that is what's going to happen to our beautiful system, to our civilization, our peoples?"

"A scientist's duty," he answered harshly, "is not to think. He must know!" He turned swiftly on the bearded captain. "All right, Dan. Get busy! We've got little enough time. We're going to get all available data on this damned space-positron."

It took them almost a day of Earth time. A desperate, feverish race with onrushing disaster. The swift space-cruiser roared along the very edge of the mighty hole in space, building up reckless velocities, darting over its spangled surface, probing its depth, its direction, its size and velocity. Within the control chamber, tension built up to electric proportions, as Jerry, with Sandra's help, tested, flashed electron streams, plotted charts, calculated.

The last calculation ripped out of the integraph, the last chart was plotted on the automatic space-graphs. Jerry stared at them with a practiced eye. An unbearable silence surrounded him. Dan flicked him a glance, turned back steadily to his controls. But Sandra could not prevent a little moan.

They both had seen—had read the doom that was writ large in Jerry's eyes' as he stared at fateful charts and figures.

"The solar system will smash into a nova, won't it?" the girl asked bravely.

Jerry lifted his gaze. There was pain, infinite sadness in his look. "Not quite," he said tonelessly, "but it's almost as bad. The probes give the positron bubble an ellipsoid shape—62,340,000 miles along its major axis, and 44,591,000 miles along its minor axis. Its spatial coordinates show a directional velocity toward the Sun's path in space of twelve miles per second—zero velocity along the other coordinates. Which means that, with respect to our System, the positron area is motionless in interstellar space, and that the Sun and its attendant planets are meeting it head on."

"Please, Jerry, come to the point," Sandra begged. "What will it hit?"

He evaded her feverish question. "Thus far," he said slowly, "the System has been fortunate. The orbits of the outer planets have not coincided with the ellipsoid."

"You mean Callisto is safe?" whispered the girl. She was thinking of her father.

Jerry's eyes brooded on her slim loveliness. "Callisto is safe—for the present," he replied gravely. "But the longitudinal surface will graze Juno, in the asteroid belt. The attendant energy development will be sufficient to fuse the tiny planet into a miniature sun. Luckily, the glancing blow will not produce an explosion of the order of a nova."

"Thank God for that!" breathed Sandra. "Then there's really nothing to worry about. Juno is uninhabited." "Mars, the next planet in line," continued the young man inexorably, "will be in conjunction, on the other side of the Sun. But——" he hesitated, and his face clouded.

The girl put her hand to her mouth to prevent an outcry. "Then the Earth will——"

Again he avoided their gaze. "Yes," he said very low. "Earth is directly in line. It will be a total envelopment. Earth cannot escape."

SANDRA fell back into a chair, hid her face in her hands. The vision of Earth, her home, its green fields and tossing oceans, its teeming peoples even now living and loving and laughing, unknowing of onrushing catastrophe, brought choking sobs from her lips.

"Yes," repeated Jerry dully, as if to himself, "nothing can save Earth. A new nova will appear in the heavens for the delectation of astronomers on some Sirian planet."

Captain Garin's broad shoulders heaved. With an oath he locked the controls, strode gigantically across the little chamber, caught the slighter man's shoulder in a bear-like grip, shook him violently.

"Lay off that nonsense," he roared. "You're the best damn scientist in the system, ain't you?"

Jerry smiled wanly. "That's what you say," he retorted.

"Well, you are," Dan shouted. "I know it, Sandra knows it, every one else admits it. You're not going to fall down on us now, lad. You're going to think up some scheme to chase that blasted positron back where it came from." The young man shook his head mildly. "I'm not a miracle worker," he said. "Nor is any other scientist in the System. You might as well ask that we stop the Sun in its course, like ancient Joshua, or turn off the Moon."

"How much time is there?" rasped the bearded captain.

"I've already figured it out. The longitudinal vertex of the positron ellipsoid is 310,000,000 miles from the point of intersection with the orbit of Earth. At the Sun's speed of twelve miles per second it will take exactly three hundred days for the explosion." Sandra breathed easier. "Why, in that time you could practically evacuate all of Earth's population to the other planets."

Jerry shook his head. "You forget what happened when the freighter, Mercury, a tiny bit of matter, flashed to extinction. Think of Earth, with its trillions of tons, blasting to annihilation. Its atomic nuclei exploding. Think of the nova in other galaxies. There would be a flare-up, an expanding shell of gas that would engulf the entire Solar System. Only Neptune and Pluto might escape. And even if they were habitable—which they are not—no rocket ships could get there in time."

"Oh!" said the girl faintly.

But Dan Garin laughed almost jovially. "Three hundred days!" he thundered. "Why, that's an eternity! If you can't figure out a way in that time, lad, you just don't deserve to have a girl like Sandra. I'll up and marry her myself."

Jerry grinned, snapped out of his despair. "With a threat like that—" he exclaimed. "O.K.! How fast can you get back to Earth?"

The captain squinted at his fuel gauges. "Hm-m-m! The tanks are only a quarter full. But there's no time to stop at Vesta, and Mars is too far away. Damn it, boy! I'll give her everything we got, build up acceleration as quick as the tubes can hold it, and then coast the rest of the way to Earth." He did some figuring on a scratch pad. "I think there's enough to get a maximum of five hundred a second. At that speed we'll hit Earth in six days, which gives you 294 days more to do your stuff."

HE spun on his heel, ripped open every visor screen. The startled faces of the crew leaped out at him. "Come on, you blasted scalawags, you lily-handed sons of Saturnian monstrosities," he roared, "get to work! Work as you've never done before, as you never hope to do again. We're going back to Earth, and we're busting the Arethusa wide open to get there pronto. Bale out the fuel, cram the rocket tubes until they smoke, sit on the safety valves and let her ride. We're getting back in six days, d'ye hear?"

They heard and they grinned impudently back at their blustering commander. They loved him and would have gone through Hell for him. "O.K., old bullhead," shouted a grimy rocket-tube tender. "Keep your shirt on, and we'll get you there."

Danny turned to his passengers. "Y'hear that?" he demanded plaintively, "that's the kind of a rotten crew they hand me." But there was a twinkle in his dark eyes as he groused.

The spaceship swung in a wide arc. Jets of flame blasted out into space. The great hull thundered with fierce vibrations. The heavens whirled dizzily. The three in the control chamber caught at straps and cushioned seats to ease the tremendous acceleration. The Arethusa fled like a flaming comet back toward Earth, in a wild race with impending disaster.

"Don't you think," gasped Sandra, when she could catch her breath, "that we ought to televise Earth at once, to give them immediate warning?"

Jerry set his jaw grimly. "We'd better not," he decided. "They'll think us crazy. It'll be hard enough convincing sceptical scientists when we try to explain in person."

Just how hard it would be, even Jerry himself did not quite realize at the time.

They barely had fuel enough to smother their headlong fall toward the green-tinged planet. They hit the cushioning hydraulic cradle at the great rocket port on the Atlantic with a spine-jarring smack. Yet, without waiting even for the glowing, friction-heated hull to cool, they slammed out of the exit-port, yelled for an air-taxi.

"Hey, there, Captain Garin!" shouted a hurrying official. "This is most irregular! You weren't due back for another month. Where are your clearance papers?"

But Dan waved derisively down to' the gesticulating field official from his seat in the taxi. "Give her the gun, fellow," he yelled to the pilot. "We ain't got any time to waste."

Within an hour they glided to the landing roof of the huge Planetary Council Hall, islanded on the great Atlantic swell. The capital of the Solar System, owning jurisdiction only to the interplanetary State, It was a magnificent affair. An artificial island, anchored immovably to the continental shelf, some sixty miles out from the American city of New York, dedicated to the uses of the ruling Council. White and gold buildings dotted its smooth white surface, housing the various ministries of the Planetary League.

Earth and Mars were the powerful member States, with the autonomous Colonies, young and vigorous, steadily gaining in influence. Earthmen inhabited Venus, the hollow caverns of the Moon, and Callisto. Martians swarmed on Ganymede, Io, and Europa. Since the first Interplanetary War between Earth and Mars in 2346 A. D., Earth era, when both planets had been reduced almost to shambles, cooler heads had intervened and set up an amicable League. No further trouble had resulted. Disputes, claims to new territory, clashes between colonists, space-commerce rights, were quickly ironed out in an atmosphere of utter cordiality.

WHEN, in the 29th century, piracy along the interplanetary lanes had become a formidable threat under the aegis of the terrible Il Valdo, the patrols cooperated in stamping out the black-dusted vessels. It was Dan Garin who had finally discovered Il Valdo's almost inaccessible lair, and blasted him out of existence.

Towering high over the surrounding buildings on the Interplanetary Island was the great Council Hall. It soared upward for a hundred stories, its white and gold dazzling in the sun. Its flat roof had room for hundreds of Earth-planes, air-taxis, and even for the small, swift private cruisers that rocketed between the nearer planets.

Even as Dan Garin paid off the pilot of their air-taxi, Jerry Hudson said joyfully: "We're in luck. Look at those rows of fast space-cruisers on the racks. Official insignia on every one of them. Mars, Venus, Ganymede. There's a Council meeting in session. That means we'll get quick action."

A Council guard hustled over importantly just as the taxi took off again. "You can't land here," he exclaimed. "The Council is in session and no private individuals are permitted without a signed order from the mainland."

"Had no time to pick up any documents," Jerry answered quietly. "We've got news for the Council that's of the most urgent importance. Get down to the Hall as fast as the tubes can drop you, and tell Ira Peabody, Earth Representative and President of the Council, that Jerry Hudson, Captain Daniel Garin and Sandra Stone have returned from Callisto with matters of the gravest import to the entire System."

The guard—he was a youthful Moon Colonist, new to the job—hesitated uncertainly. He had heard of Hudson; the bearded Captain's name was still on every tongue; and James L. Stone, Sandra's father, was powerful—but his orders had been positive.

Dan towered over him. His black face screwed into fierce contortions. "Did you hear Mr. Hudson?" he roared. "Get going before I break you in two!" The guard backed away hastily from the frightening apparition. "Y-yes, sir," he stammered. "I didn't mean to——"

He turned incontinently and fled for his life. Captain Garin was obviously not a man to be trifled with.

"My goodness, Danny," Sandra cried. "When you put on a face like that, you scare even me."

He grinned. "I learnt that trick from 11 Valdo's men," he explained. "They used to frighten swell ransoms from their captives with their horrible scowls."

Within five minutes the guard was back, apologetic, subservient, yet keeping a discreet distance from the terrible Captain with the thick, black beard.

"President Peabody will see you right away," he said. "There's a recess just now. If you'll follow me——"

The great vertical tube dropped them at break-neck speed to the private office of the President. Ira Peabody rose to greet them. He was a tall, stooped man with gray hair and a thin, ascetic face. His sole consuming passion was the Interplanetary League. His devotion was that of an idealist; he loved resounding words like Truth, Justice, Honor! It was even whispered that when practical matters intervened, he waved them aside with a lofty disdain.

HE shook hands cordially, yet with a certain surprise. "Glad to see you, Jerry, and you, too, Captain Garin. We haven't forgotten your noble work against the pirates. And as for lovely Sandra, all that I can say is that you are lovelier than ever. But I thought you three were by this time landed on Callisto. The guard told me——"

"We didn't quite reach our destination," Jerry intervened. "We found something out there in space that made us turn around and come back as fast as rockets could take us. We——"

Peabody looked uneasily at his time signal. "Good Lord!" he exclaimed, "I'm due back in the Hall. We're in the middle of a discussion on a very important matter. We're considering what title to give to the representative from the newly discovered race on Mercury. How about having lunch with me after the meeting, when we can talk at our leisure?"

Jerry kept a grave face. "Of course I understand how important the matter is under discussion, Mr. President. But our own news can't wait. If the Council doesn't do something about it right away, titles won't be of much use very soon."

"What do you mean?" Peabody looked startled.

"I mean, Mr. President, that the fate of the whole Solar System is bound up in our news. Within less than a year, Earth will be wiped out, and all the inhabited planets with it. I doubt very much if all the resources of the Council can prevent it. But at least it must try."

"You—you're just joking," Peabody gasped.

"I can back him up on every word," Dan growled.

"And so can I," Sandra affirmed earnestly. "We saw things happen right before our eyes. Let Jerry tell his story right now to the Council."

Peabody was agitated, at a loss. His hands fluttered. "But we're right in the middle of a topic. Our agenda——"

"There isn't a minute to lose," declared Jerry with decision.

Ira Peabody reflected. Jerry Hudson, young as he was, knew more about scientific matters than any one else in the system. "Very well," he surrendered, "I'll put you on at once."

The vast Council Hall had a capacity of 20,000. But it was not filled now. Only the members and the advisory bodies were present. It was on stated public occasions that the huge galleries held the countless thousands of visitors. Now, only the small inner ring around the speaker's platform was occupied. About 2000 representatives in all; yet they were the brains and statecraft of the System.

Earthmen and Martians were about equally represented—with the Martians wearing special filters over their flat noses to cut down the oxygen content of the heavy Earth atmosphere. They were tall and extremely thin, with thick, rubberoid skins to keep out the Martian cold and green-tinged with chlorophyl-plasma to extract the maximum of vitamins from the pale rays of the sun on their native planet. The Colonists of both races were invariably bigger, burlier, more aggressive than their home-staying compatriots, as has been the case with pioneers in all ages.

A solitary, somewhat frightened, strange little creature sat timidly close to the dais. The new Mercutian, representative of a people newly discovered on that supposedly sterile planet. An expedition had stumbled on them by accident on the dark side of the sweltering orb. They were a race of troglodytes, dwelling in the deepest valleys of the enormous mountain ranges, holding on precariously to their limited air and water supplies, burrowing for protection against the cold into the soft pumice-like dirt. Tiny, not over four feet high, brown-bodied and furry, incredibly lithe and boneless, with huge round eyes to make the most of eternal dimness. Now their delegate sat uneasily on the edge of his chair, his saucer eyes covered with tinted glasses to keep out the insupportable glare of Earth.

BUT the brains of the Council sat in the outer rows. The technical advisers, the scientists, engineers, planners, who made up the Advisory Boards. They seemed bored at the desultory discussion that was going on as Peabody and his visitors entered.

A Ganymedan was saying: "If it please this august Assemblage, I must protest against the use of the title, His Magnificence, for the new Mercutian delegate." He stared down from his wavering six-foot-three upon the pigmy accession. The Mercutian seemed to shrink still further into himself. "Let us," orated the Ganymedan, "consider a new name for these—uh—newer delegates. Let us say——"

The entrance of the President put a stop to these important proceedings. The Ganymedan yielded the dais. Curious eyes turned to the three Earth-visitors. The technical men in the rear sat up and took notice. What was Jerry Hudson doing back on Earth? He should have been safely installed on Callisto by now, commencing his vast research on the heavy elements, and the possibility of new ones even higher in the atomic scale.

Ira Peabody took his presidential chair. "I'm sorry to break in on our agenda like this," he apologized, "but my three visitors, all well known to every member of the Council, have thought it most urgent. Without further ado, therefore, I shall permit Mr. Hudson to tell you himself what he has to say."

Jerry, heart pounding with the extreme gravity of his message, mounted the speaker's stand, surveyed his audience. He must get his warning across, must enlist the combined weight of all the planets to back him. Yet it was an incredible thing he was going to tell them—and he had a sinking feeling as he surveyed their placid faces.

He told them his story, crisply yet carefully, weighing each word, trying hard not to sensationalize, yet bringing home in every detail the doom that awaited them all. He closed with words of earnest warning. "Even with the immediate massing of the resources and scientific ability of the entire System, it is extremely doubtful whether we can stave off overwhelming disaster. But at least we must try. We must drop everything else, concentrate on this one problem. I ask of you instant, unequivocal action."

Even as he finished, he knew that he had failed. The political delegates stared owlishly. Here and there one clucked his lips commiseratingly. It was a pity that a brilliant young scientist like Jerry Hudson had lost his wits. Overwork, no doubt.

The technical men had followed him more carefully, but with equal scepticism. Jan Worden, of the Moon, flushed angrily. He was an astronomer whose theory of the inner mechanism of nova had been most widely accepted. If this were true, then his chief claim to fame was knocked into a cocked hat. Gor Ala, Martian physicist, scowled darkly. He was an authority on positrons, and he had maintained with much vehemence that these evanescent creations were highly unstable bits of matter, and not negative energy states as that ignorant ancient, Dirac, had first decided. Others of the technicians had their own pet theories, and every one was ruthlessly brushed aside by this appalling new development that Jerry had brought into their midst.

THEY arose clamoring, defending their prepossessions with much heat and prejudice, attacking every angle of Jerry's positron bubble. Gor Ala led the attack. "We know by this time what positrons are, their nature, their essential breakdown. It is impossible for such a state as Hudson predicates to exist longer than a millionth of a second anywhere in space. With all due deference to his proven scientific ability, it is more than likely that he found a familiar type of frictional electricity based upon a huge cloud of meteoric dust. As for the tragic fate of the Mercury, its shields may have been defective, and the friction of its passage generated a sufficient static charge to disrupt its atomic fuel." Jan Worden followed. "I would have placed greater credence in Hudson's fantastic story if he hadn't coupled it with a jejune theory about the origin of nova.

I have conclusively proved that——"

The Secretary of the Council, a Venusian, observed tolerantly: "By Mr. Hudson's own admission, we have almost three hundred days to worry about this—er—phenomenon. Let us first send a fact-finding commission to investigate the matter, before we go off half-cock. In the meantime, the agenda of our meeting has been sadly disturbed. Now as to the question before the Council—the title by which the Mercutian delegate is to be addressed—let me say in no uncertain terms——"

In the privacy of his own office, Ira Peabody spread his hands placatingly at the storm of indignation with which Sandra threatened to overwhelm him. Her eyes flashed and her tongue was a rapier thrust. "Fact-finding commission indeed!" She stamped her slender foot. "What can those pompous ninnies find out that Jerry hasn't already determined?"

The President tried to clothe himself in the torn shreds of his dignity. "You must remember, my dear young lady," he intoned, "that this is our regular procedure. We cannot disrupt the work of the System on—uh—a wild goose chase, without adequate preliminaries, without complete reports. Of course," he added hastily, "no one knows better than I the scientific merits of our young friend Hudson; but you heard the Advisory Technicians——"

"Yeah!" Dan Garin interrupted brutally, "you'll be reading your blasted reports just in time to sizzle to a cinder. Come on, Jerry, let these political dodos and their yes-men stew in their own juices. We got a man's job to do!"

Growling like a wounded bear, he caught the grim young scientist with one huge paw, the slim, raging girl with the other, and literally forced them out the door. Behind them a sadly bewildered and rather futile-looking idealist murmured agitatedly: "Dear me! Dear me!"

IT took the fact-finding commission ten days to get started. Gor Ala, the Martian and authority on positrons, was placed in command. He could not be rushed. It was, he felt, an excellent chance to crush his rival, the young Earthman, once and for all. So he filled three rocket ships with every conceivable type of equipment, checked and rechecked in advance.

Only the disturbing reports that began to filter through of ships on the Jupiter route being overdue induced him finally to hasten his preparations. They had been careless, no doubt, and permitted their shields to become defective. Static electricity covered all the facts—of that he was positive. Yet the great space lines were becoming anxious about their missing vessels, were clamoring for action.

On the eleventh day he started. There were speeches and admiring plaudits at the rocket port. Among those not present were Jerry, Dan and Sandra. They were immersed in Jerry's Earth laboratory, working furiously at a seemingly insoluble problem.

The planets were not disturbed. Judicious news items had been issued, emasculated editions of Jerry's jeremiad, followed by soothing announcements. Young Hudson was naturally an alarmist—his hypothesis was purely tentative—and, in any event, the famous physicist, Gor Ala, was even then on his way to check up. In the meantime, let Business Go On As Usual.

Business went on as usual. So did life. The peoples of the planets heard the newscasters, laughed, shrugged shoulders, discussed the possibilities with the same unconcern as if they were about an alien system. They made jokes about jittery scientists, and forgot them.

Gor Ala was in no hurry. The three ships under his command were fast cruisers, but he kept them at their normal space rate of two hundred miles per second. Not for him the risky pushing at top speed that had brought the Arethusa back in six days.

The voyage took thirteen days. From the space coordinates that Jerry had grimly given him, together with the pertinent data on directional velocity, etc., he calculated that the unknown field of force, at the time of his arrival, would be in the neighborhood of the asteroid Juno.

He was correct. On the thirteenth day, the three ships, driving parallel, spaced 10,000 miles apart, beheld the phenomenon almost simultaneously.

It was impressive, as even Gor Ala was forced to admit. He had never seen anything like it before. As far as his eye could reach, as far as his visor screens could take him, space was a glitter of innumerable darts of light, flashing up out of nothingness, blazing to sudden extinction, while new ones took their place.

Exactly as Jerry Hudson had described it. The spanglings were thickest on the outer surfaces of the ellipsoid, thinner within. But there was a certain variation. Whereas the young scientist had spoken of only one dark pocket within, caused by the destruction of the ill-fated Mercury, now there were a half dozen such pockets, all close to the surface.

For the first time Gor Ala experienced a little sensation of fright. The cold sweat burst out on his green, leatheroid skin. Including the Mercury, five space-liners had been reported missing. Could it be that——?

He shook his head angrily. This was nonsense, of course. A tremendous hole in space, a negative energy level that swallowed electrons, indeed! Hadn't he proved the contrary about positrons?

NEVERTHELESS, he signalled his ships to stand off, not to approach too close as yet. While he was confident that it was a field of infinitely small particles of meteoric dust, generating millions of volts of frictional electricity, and while he had checked carefully the insulating shields on his convoy, nevertheless it might be wise not to take any chances, but to investigate first.

But even as his signal ripped out into space, the farther cruiser, captained by an over-enthusiastic young Ionian whom he had thoroughly imbued with his own scepticism, had swerved suddenly and directly for the innocent-seeming little sparklets. Whether it was reckless over-confidence, or a desire to steal the honors of the expedition away from Gor Ala, no one was ever to know.

The Martian screamed angry warning into the visor, but it was too late. Perhaps the young captain heard and pretended ignorance. On and on rushed the vessel, headlong toward the glittering mass. Gor Ala, in the confines of his control chamber, yelled hoarsely and danced with rage. Whatever happened, he would Be the loser.

Then there was contact. The disobedient ship clove through the droplets of fire, scattered them to the right and left. At two hundred miles a second it ripped into the heart of the mysterious space, deeper, deeper, like a fast fish diving in luminescent water.

Now Gor Ala raged in good earnest. Damn that young squirt! He was safe, unharmed. Even as he, Gor Ala, had postulated. His shields were impregnable to any voltage. But he had stolen the show, and Gor Ala's glory would suffer. Wait until he got hold of him! He would prefer charges; he would see to it that——

The scattering flashes seemed to coalesce around the plunging cruiser, clung in sheeted flame to its rounded hull. Then suddenly Gor Ala staggered back with a loud cry, flung his hands over his blinded eyes to keep out the intolerable blast of light.

Out there, deep within the glittering mass, something had happened. Something terrible and cataclysmic!

The errant ship blazed with a fury of molten hue; a shell of blazing light swept rapidly out in all directions. Then there was an explosion. The hapless cruiser vanished in a shower of hurtling, dazzling particles. The velocity of expansion was incredible. Farther, farther they sped, flaring new areas to brilliance, leaving in their wake sullen darkness—moveless—dead——

At the very core a tiny replica of the huge ship was a molten mass, a miniature sun, on which it was impossible to look.

AT a distance, Gor Ala took stock with his frightened sister ship. He was puzzled, angry, and, withal, scared. He told himself, he told his dismayed companions, that young Tamu had been negligent, as well as disobedient. By a dreadful oversight he had permitted his shield to drain of its resistance.

But he could not convince himself, much less the others. He saw it in their ashen faces, the wary looks they turned to that firefly dance out in space, to that new gigantic hole where their comrade had rashly penetrated.

"I think," said one bolder than the rest, an Earthman, "that Jerry Hudson was right. My own hasty tests have been all in confirmation. We had better flash warning back to the Council at once!"

Gor Ala stabbed him with a furious glance. "I am in command of this expedition, not you," he said coldly. "When I have completed my own tests, I shall decide on our course."

"But at least," protested the Earthman, "we ought to report without delay the fate of poor Tamu, and what we discovered of the missing ships."

"And scare the Council out of its wits? That, too, can wait."

There was an uneasy mutter among the scientists. Gor Ala was running things with a high hand, yet there was nothing they could do about it. The Council had expressly given sole command to him, and discipline was strict.

Yet a burly Venusian could not forbear another protest. His eyes were glued to the space chart where Juno showed as a small disk. Close to its edge, closer than was comfortable, the inexorable line of dancing light motes was marching.

"Now look, Gor Ala," he said determinedly. "Only 65,000 miles separate that damned space field from Juno. At their respective rates of speed, it will take only an hour and a half for the asteroid to graze the field. According to Jerry Hudson, even that glancing touch will be sufficient to fuse it to incandescence. At present we're running approximately parallel to them both. At the moment of contact, our ships will be a bare 42,000 miles from Juno. If anything does happen—we're out of luck."

"You're beginning to believe Hudson's nonsense," the Martian laughed scornfully. "An asteroid is an entirely different proposition from a tiny spaceship. A rocket cruiser is stored with highly combustible fuel. If for any reason the shield is drained of its resistance, a child in the lower schools could tell you that high-voltage static electricity would explode it. But on that sterile chunk of rock, nothing like that could possibly happen. Not even an aurora effect, since Juno possesses no gaseous envelope. We are scientists, Hanson, not frightened little children. It is our duty to stay close, to observe once and for all the destruction of Hudson's silly theory."

Hanson, whose ancestors had been Earth pioneers on Venus, met his superior's angry gaze with level eyes. "I, for one, have become converted to Hudson's silly theory," he declared boldly. "And I don't intend staying here to be blasted to extinction. I'm going back to my own ship and head for Earth to give warning."

"You'll do nothing of the sort," snapped Gor Ala. "I order you to stay."

"Nuts!" declared the Venusian inelegantly. "I'm going."

"And so am I," spoke up the Earthman.

"That's mutiny," gasped the Martian.

"Call it that or anything you damn please. But don't try to stop me."

HE was a burly specimen, and his hand was close to his ray projector. In silence they watched him stamp out of the control chamber, followed by his companion in mutiny. In bitter silence they saw his space-boat catapult from the lock, dart swiftly to the other ship. With longing in their eyes, they saw their sister craft swing around, rockets belching, on its long flight back to Earth. Yet they remained, obedient to orders, sticking by Gor Ala in spite of their private thoughts.

An hour and a half out in space, almost to the second, Hanson, the Venusian, and Whitney, the Earthman, saw it happen in their visor-screen.

A pale line of flame ran along the terminator edge of the asteroid. The flame exploded. Blazing fragments rained out into space. In progressive waves, as the rest of the planet received the impact of the fiery particles, as blasting heat smashed deeper and deeper, Juno glowed incandescent. A sun was born!

Though the fleeing ship was already more than two and a half million miles away from the scene of disaster, the heat of sudden combustion overwhelmed their thermal controls, made a searing oven of the interior. Gasping, retching, blinded with the molten glare, Hanson staggered to the visor-screen, frantically snapped connection with Earth. Breathless words poured out warning.

But Hanson's warning was not necessary. Back on Earth, clustered around an electronic scanner, Jerry Hudson, Dan Garin and Sandra Stone were watching in grim silence.

Even as they saw the explosion, watched the incandescence that once had been Juno, the shell of heat struck them. The temperature gauge in the laboratory ran up ten degrees in ten seconds; the walls dripped with sudden steam.

"Juno blasted according to schedule!" For once the black-bearded captain's voice was oddly quiet. "Gor Ala and all his men are but shells of vapor."

"They'll believe you now, the fools!" Sandra whispered almost hysterically.

"Yes, they'll believe me now," said Jerry slowly. He was white-faced, shaken. He was rehabilitated in the eyes of the world, but the triumph was empty, mere ashes and Dead Sea fruit. What profit to be right when, within a bare eleven months, the Solar System would be stripped of life, would fuse to primal incandescence? If a mere grazing contact with an inconspicuous asteroid had led to such tremendous results, what would happen when the entire Earth immersed in the deadly area of negative energy?

Then, almost immediately, the sono-speakers commenced clamoring. The whole System was simultaneously trying to get in touch with the once-discredited scientist.

First Hanson, with his eye-witness account and confirmation of the loss of Gor Ala and two ships. Then a flood of terrified appeals from Mars, Io, Ganymede, the Moon, from every nook and cranny of Earth. Frantic, clamoring, imploring, throwing themselves unreservedly upon Jerry Hudson for protection against onrushing disaster.

Then, finally, blasting through all other calls on the powerful Council wave length, the almost tearful voice of Ira Peabody, President of the Interplanetary League.

"For God's sake, Hudson," he cried in extreme agitation, "you've got to do something, anything, immediately. You were right and the rest of them were wrong. The Council has just met and given you dictatorial powers. The planets, every resource of the System, are turned over to you. Call on every scientist for help. But you must find a way to stop this terrible thing before it hits Earth. You have no idea what's already happened from the flare-up on Juno. We've been overwhelmed with reports. They're awful! You're our only hope now!"

"I'll do my best, Mr. President," Jerry said coldly and snapped off the sono-tube.

He turned to face his companions. Sandra's eyes were shining. "You'll do it, Jerry. I know you will," she said softly.

Dan clapped him on the shoulder. "There ain't a doubt about it," he roared jovially. "Lad, the universe is yours!"

Jerry smiled a twisted grin. "I wish I were as certain as you two," he answered dryly.

THE inhabited planets were in a turmoil. The disaster in the asteroid belt had caught them unprepared, because the announcements the Council made beforehand had been deliberately fragmentary, soothing.

The satellites of Jupiter suffered the most. Io and Ganymede, closest to the new sun, had almost roasted alive. The Colonists, fur clad against the constant cold, gasped and pulled frantically at their stifling garments. Callisto, luckily, had been on the opposite side of Jupiter, and that mighty orb had been an effective shield against the sudden outburst of heat. And Jim Stone, Sandra's father, had been warned in time by his daughter, and had taken the necessary precautions.

Mars escaped intact. It was still in conjunction With the Sun, remote from the cataclysm. On the Moon it did not matter. The sealed caverns were insulated against heat and cold. Venus barely felt the effect through its blanketing atmosphere. But on Earth there was trouble. An increase of ten degrees in temperature was a serious matter.

Crops were forced untimely from the ground, the tropics sizzled with added heat. Evaporation increased enormously. Steam rose from the oceans, coalesced in huge cloud banks, beat back to earth in furious storms. The northern ice, the glaciers, softened and thawed. Floods followed, great, lashing tides, inundations. The loss of life and damage to property were enormous. And all the while, low in the heavens, a new sun, tiny but brilliant, glared balefully with the threat of approaching disaster.

Jerry went to work at once. The Council was prostrate at his feet, the scientists of the planets feverishly eager to obey his lightest command, the plain people hailed him as their only savior.

His first thought was to send out scouting ships to observe the ominous hole in space, to report instantly every shift, every change in its texture and direction. Perhaps, he hoped, the collision with Juno had broken it up, had somehow rendered it innocuous.

But even before the hundred hurtling cruisers reported, he knew that it could not be. The encounter with Juno would have sliced off a sizable area, filled the negative-energy states with electrons, and restored the placid normality of space. But the surviving mass would be sufficient to destroy Earth. As for change of direction, that was impossible. Neither heat nor gravitation nor impact with matter could appreciably stay its inexorable course.

AND so it proved. Re-measurements disclosed the fact that the ellipsoid had shrunk along its longitudinal axis a full million miles, but Earth in its appointed orbit would still find itself thirty thousand miles deep within the negative space of the bulge of the minor axis.

Jerry said despairingly: "If only we could slice off that much more, Earth would be saved."

"If I remember correctly," suggested Sandra, "a magnetic field will swerve positrons from their path. Doesn't that help?"

"Not in the slightest," he answered grimly. "I already considered that phase of it. The amount of magnetism that we could build up with our generators would be infinitesimal compared to that which is required. Only the Sun is a sufficiently powerful magnet to do the trick. And at that distance the Sun is not close enough to exert a useful effect."

"I've got it," Dan exclaimed excitedly. "What you need are electrons to fill up the holes, to make that damned positron bubble vanish?"

"Well?"

"Why don't you get the rocket navies of the System to shoot space projectiles into it day and night?"

Jerry shook his head with a weary smile. "We haven't enough munitions in the world for one thing, and even a constant bombardment for the nine months that's left us wouldn't make much of an impression."

"Damn!" the Captain ejaculated disappointedly. "I thought I had the answer. Too bad we can't find a real big asteroid to throw into its path as a sort of a blasted sacrifice."

"Yes, it's too bad!" Jerry repeated absently. Then he jerked erect. "Eh, what's that?"

Dan was taken aback. "I only said——" he started in self-defense.

But the young scientist's eyes were blazing; his body was a taut bow. "By the three-headed toads of Phobos, you've hit upon it, Danny!"

"You don't mean to say you can push asteroids around?" Sandra protested.

"Of course not. But we can sacrifice!"

"What?"

"The rocket fleets of the System, and every new one we can rush to completion in the allotted time. We have nine months to go. Look!" He sat down, scribbled furiously on a pad. "All we need is to slice off a cubic area of one hundred trillion cubic miles."

"A large order, lad," growled Dan.

"I know it. But we have now, at an estimate, some 20,000 rocket ships in the System. They range from small pleasure yachts to great 10,000-ton liners. Let us take the Mercury as the norm. It weighed about 2000 tons. Suppose we fill every last one of them with the heaviest cargoes we can get. Iron—even sand—atoms of any sort that possess the stores of electrons in orbits and electrons locked within their nuclei that we need."

HE grew more enthusiastic, scribbled more furiously. "Within nine months, with every shipyard going full blast, with the manpower of all the planets concentrated on the job, we can build another 20,000 ships, mine sufficient matter to fill every nook and cranny of them. Rocket fuel, of course, would have to be manufactured in tremendous quantities to lift these immensely heavy loads from the respective planets." He smiled wryly. "Fortunately, they wouldn't have to travel far."

Again he bent to the pad. "Now figure the average tonnage per ship, including hull and cargo, at 10,000 tons gross. Multiply that by the number of vessels, old and new—40,000 remember—and the total tonnage that we'll be able to hurl into that seemingly bottomless hole in space would amount to 400,000,000 tons. The cubic area to be filled runs to one hundred trillion cubic miles."

Dan Garin whistled. "That's mileage in any language."

"Yet we have enough material to take care of it, provided it is properly applied and at the most efficient points. I measured the dark area formed by the annihilation of the Mercury. It amounted to half a billion cubic miles for 2000 tons of matter. The proportion is almost exactly right."

The burly Captain stared. "Half a billion cubic miles?" he ejaculated. "Why, I saw it as well as you. It didn't look to me anything like that big."

Jerry smiled. "You forget we're dealing with cubic miles," he explained. "It sounds like a lot. Actually it means a diameter of not much over a thousand miles."

"But don't you know what you're doing, Jerry?" Sandra burst out suddenly. "You're going to strip the System of every ship, of all its reserves of metals. Civilization will be set back for hundreds of years."

"Isn't that better, dear," the young man replied gently, "than being wiped out altogether? We'll be crippled, no doubt, but I don't think it will take that long to get back to our feet. With united efforts we can build new rocket ships, exploit the mines, seek new sources of minerals on the planets beyond Jupiter where we haven't penetrated as yet. Of course there'll be suffering, hardship, for years to come. But perhaps it will be all for the best. Our peoples, especially on the old, settled planets, have been becoming rather soft of late. They need a return to harsher conditions of life. And in any event, it's the only way."

THE Interplanetary League drew back aghast at Jerry's calm proposal. What! Destroy every ship on the space lines, drop-everything else and build more only for similar destruction? Throw the wealth of the System into the same inexhaustible maw? It was outrageous; it was worse! Surely there was some other method, easier, simpler—one that wouldn't throw the planets back to primitive conditions, almost.

The vested interests were the loudest clamorers. The owners of ships, the dealers in metals, the great financial houses that controlled these chief sources of wealth. They would be ruined, stripped of all the precious property their ancestors had struggled to amass.

They circulated ugly rumors. It was a brazen scheme on the part of Jerry Hudson to wring untold wealth and power from the necessitous condition of the System. No doubt he and his copartner in crime, Captain Garin, had discovered an asteroid of solid polonium somewhere, and intended, after the stripping of all available supplies of the immensely precious fuel metal, to hold it for sale at exorbitant figures.

But the scientists of the System, after careful study of Jerry's data, unanimously backed up his conclusions. The System was doomed unless something was done, they announced in a joint proclamation. They had examined Jerry Hudson's plan and found it entirely feasible. Also they had examined all other plans. They would not work. The sacrifice must be made.

The Council reluctantly passed the requisite resolutions. The malcontents were put down with stern measures. Propaganda was employed to obtain the proper cooperation. Lurid pictures were painted of the Earth as a nova, of all life crisping as far as Saturn. The propaganda almost overshot its mark. It scared the people half to death. Secret expeditions were outfitted by fearful millionaires and took off for the unknown reaches beyond Saturn. Thereby precious ships were abstracted. What happened to these desperate ventures was never learned. Very likely they all Succumbed. Life could not possibly exist for long on the glacial moons of Uranus and Neptune.

Dan Garin cursed luridly at the long delay, but Jerry went calmly ahead with his plans. On the signing of the final ratifying decree his organization was full born. At a signal, work started in a thousand shipyards, in ten thousand mines. All but the most essential industries were dropped. The millions of men throughout the planets, and their wives as well, concentrated on the task in hand. Only eight months were left.

Rocket craft, of a uniform 2000 tons, slipped on the ways, and new hulls were commenced. Rocket fuel was manufactured in enormous quantities. Ore came in unending streams, was dumped into capacious holds to the bursting point. Countless billions of dollars of precious metals, the very lifeblood of civilization. New crews were hastily trained.

JERRY did not sleep or eat. He was everywhere, a whirlwind of energy, planning, organizing, exhorting, whipping up lagging workers. Sandra was with him constantly, assisting, taking care of details.

Captain Garin had charge of the technical problems of fuel supply, proper pay loads, and ultimate navigation.

They were in Jerry's Earth office. On the wall was a gigantic map of the Solar System, the ominous space-positron was marked out in moving red lights. It was now 186,000,000 miles from its anticipated meeting with Earth.

"Six more months to go," sighed Jerry. "And the work is only just really getting under way. But we can't afford to wait too long. The closer it gets to Earth the greater the danger." He turned to Garin, said quietly, "We'll have to start at once. Commence hurling loaded rocket ships into the intruder. I'll give you a duplicate of this map, marked in detail with the exact coordinates. It is essential that the sacrificial ships penetrate exactly to the areas marked. Otherwise it will never work out. We're working as it is on an uncomfortably close margin."

Dan saluted gravely. "How many ships and how many at a time?" he asked.

"I've marked that, too. Two hundred a day at as widely separated points as possible. Otherwise the generated heat of the blazing nuclei will be too great. Get going!"