RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

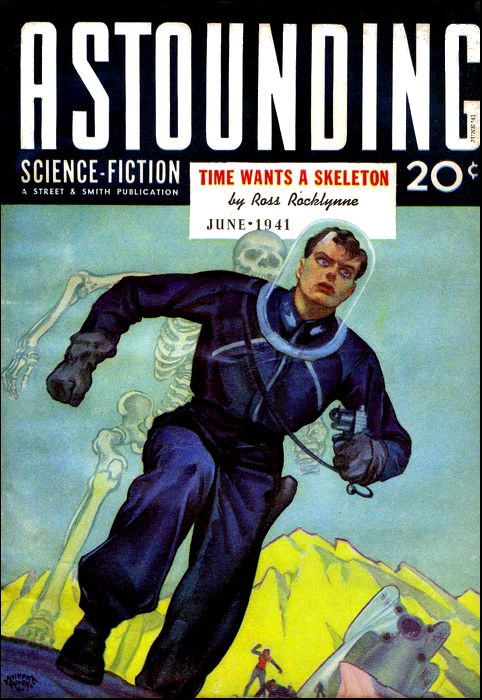

Astounding Science Fiction, June 1941,

with "Old Fireball"

SIMEON KENTON was an irascible man. He knew it; the far-flung thousands employed by the Kenton Space Enterprises, Unlimited, knew it. But only his daughter, Sally, knew he worked hard at being an irascible man. And that increased his irascibility to such a pitch that he could only glare and sputter unintelligible words.

"Har-r-rumph!" be spluttered. "If you weren't my own flesh and blood, I'd—"

"You'd be the first to agree that a man in your position owes it to his daughter to see to it that her account isn't perpetually overdrawn," she smiled.

Old Fireball was his nickname because of his habit of staging explosions on the slightest provocation. He exploded now.

"You get a larger allowance than any girl of your acquaintance," he yelled. "Yet you have the nerve to stand there and ask for more. You must think I'm made of money."

"Aren't you, dad?"

She asked it so innocently and with such a candid air that he felt utterly deflated. "Well, humph, that is—I may have a little money, but—" His indignation rose again. He snatched the statement of her account from his desk, waved it at her. "Damn it, Sally, I've had enough of this nonsense. Not another cent do you get—"

Father and daughter were standing in the private office of the president, owner and sole manager of the Kenton Space Enterprises. From this small, simply furnished room Simeon Kenton ruled an empire vaster by far than any of the mighty empires of old Earth. Rome, Assyria, England; Nazi Germany, Nippo-China, Australo-America had flung their tight webs over large portions of the Earth's surface—but Simeon Kenton's fleet spaceships fastened their flags in the spongy marshes of Venus, on the desolate wastes of Mars, on rocky asteroids and mighty Jupiter itself.

Technically it was merely a commercial empire, with ultimate sovereignty in the Interplanetary Commission whose seal of approval was necessary on all leaseholds, claims of ownership, mining rights, trade routes, cargoes, exploitations, wages and hours and conditions of employment. Actually Simeon Kenton was the kingpin of the spaceways, with half a dozen smaller princelets competing with him for concessions, spheres of influence and business. In the old days, when Simeon was a young man coming up the hard way, there had been no Interplanetary Commission and everything went, much to Old Fireball's irascible satisfaction. Not that he was a tyrant, by any manner of means. He was a driver and a hard taskmaster to his men, admitting of no failure or excuse; but he was fair and quick to reward the worthy. If he was feared and if every man in his employ trembled in his space boots at the sight of him, deep down there was the comforting feeling that Old Fireball knew what he was about, that he never let them down.

Simeon loved the exercise of power, a vast, benevolent paternalism with himself as the paterfamilias. As space became less of a thing unknown, and law and order took the place of the old scramble for new worlds, however, codes were established, spheres delimited and space law came into being. All this was much to Old Fireball's tremendous disgust. He grumbled constantly of the good old days, when men were men and not members of the Interplanetary Union of Spacemen, Blasters, Rocket. Engineers, Wreckers and Cargo Handlers, Local No. 176.

"Har-rrrumph!" he'd snort, "if a man's got a grievance, why can't he come direct to me instead of running like a dodgasted infant to whine to his union and the commission? Sure there're chiselers among the other companies. There's that double-dyed leohippus, Jericho Foote, of Mammoth Exploitations. Feeds his men stinking, crawling food, pays 'em when he can't help himself, wriggles out o' his contracts like a Venusian swamp snake. I wouldn't trust that smooth-faced, smooth-talking Simon Legree farther than I could throw an asteroid." He nibbed his own straggly white whiskers complacently. "Regulations an' laws're all right for guys like him, but not for me."

Accordingly he instituted a legal department in Kenton Space Enterprises, Unlimited; and many and Homeric were the legal tilts and battles between himself and the commission. He snorted and yowled and tore his hair when a decision went against him and rained maledictions on the unfortunate head of his chief legal adviser, Roger Horn, and on the august members of the commission alike; but if the truth were to be told, he loved it. Space had become too tame and business had become too grooved; and these tilts were the safety valves for his love of a keen-witted fight.

He scared everyone but his daughter. She smiled understanding at his tantrums and humored him as though he were a crotchety old invalid and went blithely on her way regardless. And they got along famously, even though, as now, he stormed and ranted and fumed.

"Yes, siree," he yelled, "not another cent do you get until the next—"

THE slide panel opened noiselessly and a young man came into the room. He was a very determined-looking young man with a square jaw and intent blue eyes. Sally Kenton pivoted on a daintily-shod foot to look at the intruder.

The determined young man didn't see her at first. His blue eyes were set and his square-jawed face pointed like a hunting dog's directly at the incongruous, mildly whiskered saint's visage of her father. There was something very definite on the young man's mind.

"Mr. Kenton," he said, "I've been in your employ for more than a year now and—"

Simeon's pale-washed eyes flashed dangerously behind his glasses. All the irascibility his daughter had frustrated focused on this most impertinent, rash intruder.

"Ah, so you have, have you?" he purred. "And what might be your name, my dear sir?"

"Dale—Kerry Dale. I'm in the legal department, under Mr. Horn. And I think—"

Simeon Kenton seemed to grow on the sight. His chest puffed and his cheeks puffed in unison. He raised on his toes until his five-feet-four assumed the dimensions of a giant. "So you think, Mr. Kerry Dale, or whatever your name might be? You think you have the right to barge in on me when I'm in private conference without so much as a by-your-leave and inflict your utterly useless thoughts on me. When you've been five years in my employ, not just twelve months, fifty-two weeks, three hundred and sixty-five days, you'll know better than to waste my time with dodgasted nonsense. Get back to your desk, Mr. Kerry Dale, and stay there. That's what I suppose that fool, Roger Horn, is paying out my hard-earned money for—"

He stopped for breath; inflating his lungs for another blast.

But the young man gave him no chance to continue. He was a tall young man and with a certain set to his shoulders, as Sally noted with approval. She enjoyed her father's outbursts and knew how strong men wilted and blanched before them, and slinked—or was it slunk—away before their withering blasts like whipped dogs. Would this Kerry Dale do the same?

He did not. A certain steely glint hardened his intent blue eyes. "I've always wondered why they called you Old Fireball," he said slowly. "Now I know. The term is apt. I've seen them in space. They're little and all puffed up and they explode at the merest contact with a breath of air and scatter themselves harmlessly. Calm down, sir; or you'll get a stroke."

Sally heard old Simeon's quick, choking gasp. Her own senses tingled. She was going to enjoy this.

"Me—Old Fireball! Why, you young snipperwhipper—I mean whappersnipper—damn it, you know what I mean—get out of here before I—"

The young man took a step forward. His hands gripped the fuming old man by the shoulders. "Not before you hear what I've got to say," he snapped. "I'm ashamed of you," he said severely. "I thought there was a man running the Kenton Space Enterprises. People said there was. That was why I was anxious to get in. That was why I took a job in that scrape-and-bow legal department of yours as soon as I got out of law school, under that smug old fossil, Roger Horn. That was why I worked my head off, twenty-five hours a day, twisting good, honest law and picking legalisms in the space codes so your piratical deals could sneak through regardless."

His indignation mounted in equal waves with the color in his face, and with each surge he shook the mighty Simeon Kenton just a little harder. "I suppose you think it was your fine Roger Horn, that puffed-out bag of wind, who won you the suit against Mammoth last month? I suppose you think it was that same self-winding Horn who thought up that neat little scheme whereby you obtained legal possession of Vesta against the actual staking-out claim of the government of Mars? Sure he took the credit for it. He always does. Loyalty of the department! Loyalty to Kenton Space Enterprises! Bah!"

Simeon was choking, spluttering, opening his mouth in vain attempt to make headway against this most remarkable torrent of words from this most remarkable young man, and failing utterly.

Kerry plunged on, not even knowing Simeon was trying to say something.

"Who cares about your overgrown schemes?" he yelled. "For a year I cared, and became a wage slave. Me, Kerry Dale, summa cum laude from the Planet Law School, voted most likely to succeed. Let me tell you what happened this very morning. I went to your ass of a legal chief, as humble as you please. I asked him for a raise; for a job a little above the thirty-ninth assistant-office-boy job I still hold; and what do you think the old windbag tells me?"

Simeon opened his mouth again; and it was rattled shut for him. "I'll tell you," Kerry yelled down at him. "He hemmed and hawed and grunted like an old sow and twiddled his thumbs and said it was a fixed rule in the empire of his majesty, Old Fireball, never to grant promotions under three years of slavery. He said—"

OLD SIMEON found tongue at last. It had swelled with indignation until it protruded from his mouth. "That goddasted blitherskite—I mean that dadgosted slitherblite—did he dare call me Old Fireball?"

For the first time Kerry Dale grinned. He released the fuming old man. "He didn't quite call you that," he admitted. "That's my own inventive genius; or rather, the inventive genius of every slaving underling in your employ. But I thought, like a fool, I'd come direct to you. They said you were a hard man and given to tantrums; but fair. I see now they were mistaken."

Old Simeon shook his released shoulders back into position. He twitched his rumpled vest back into shape with a violent gesture. He saw red—and yellow and purple and a lot of colors not in the normal spectrum. "Get out of here, you... you overgrown son of a space cook! Give you a raise? Sure I'll give you a raise, with a blast of rocket fuel under your space-rotted tail! Get out of here, young man. You're fired."

"You can't fire me," Kerry Dale said bitterly, "I've already resigned. I resigned as soon as I took a good look at you."

He turned sharply on his heel and stalked out through the open slide panel. The mechanism closed softly behind him. Old Simeon shook his fist. His wispy hair and wispier beard were all rumpled, and there was a glare in his eyes.

"Of all the impertinent young—

Sally was interested; yet offended. Interested in the way this most remarkable young man had maltreated her revered parent—something that no one had dared do as long as she could remember—and offended because in all that stormy interview not once had his eyes strayed toward her; not once had he shown by look or gesture that she was even present. She wasn't accustomed to that sort of treatment any more than Simeon Kenton was accustomed to the kind he had received.

Even if she hadn't been Sally Kenton, men's glances would inevitably have gravitated in her direction. She was mighty easy to look at. From the top of gold-bronze head to most satisfyingly shapely ankles she attracted attention, and the neat little dimple in her chin and the quick quirk of her lips did their share in fixing that attention. Yet this Kerry Dale had positively not seen her.

"Is that true what he said?" she interrupted Simeon's premeditated flow of language hastily.

Her father almost choked on an epithet; glared at her. "What's true?" he howled.

"That he prepared that Mammoth brief for you and cooked up that deal in which you hornswoggled the Martian Council?"

Sally had learned a thing or two associating with her obstreperous parent.

"How do I know?" he yelled. "That's Horn's business; that's what I pay him for. Do you think I bother my head—"

"You ought to," she told him severely. "It's the business of the head of an organization to know exactly what's going on, down to the last space sweeper," she quoted.

He recognized the quotation. In an off-moment he had permitted himself to be interviewed by the telecaster for the Interplanetary News Service. "Har-rrrumph! I don't know—well, maybe—" He pressed a button.

THE florid features of Roger Horn looked startled on the visiscreen. He was a portly, dignified-looking person. His strong, aquiline nose and bushy, beetling brows overawed judges, and his weighty throat-clearings gave the impression of considered thought.

"Ah—yes, Mr. Kenton?"

"There's a young whelp in your department, Horn. Name of Kerry Dale."

"Why... all... that is—"

"Save the frills for the Interplanetary Commission. Did he, or did he not write the Mammoth brief?" Horn looked unhappy. "Why... ah... in a manner of speaking—"

"Did he, or did he not punch that legal knothole into the Martial claim on Vesta?" old Simeon pursued relentlessly.

The lawyer squirmed. "Well—in a sense—"

Kenton's glare was baleful. Sally chirruped: "There, what did I tell you?" though she hadn't said a thing.

"Quiet!" yelled her esteemed ancestor. His glare deepened on his lawyer in chief. "So the young snipperwhopper was right! I pay you, and he does all the work."

Horn assembled the rags and tatters of his dignity. "Now look here, Mr. Kenton—"

"Quiet!" Simeon thundered him down. "What do you mean by refusing a raise to such a valuable... er... young man? Do you want that planetoidal scoundrel, Foote, to get his slimy tentacles on him and show you up for the pompous dincumsnoop you really are? Raise him twenty-five; raise him fifty; but don't let him get away."

Horn looked as though something he ate hadn't quite agreed with him. ""I can't," he said feebly. "Young Dale just left here. He said he had resigned."

"Then get him back. Comb the whole dingdratted town for him. Offer him a hundred."

"He said," Horn swallowed hard, "he wouldn't work for Kenton Space Enterprises again if it was the last outfit in the Universe. He said—"

"I don't care what he said. Get him; or else—"

"Y-yes, sir," the lawyer gulped. "I'll do my best."

Old Simeon switched him off, still protesting. "Hell come back," he said complacently, pulling on his chin whiskers. "Just a bit hotheaded, like all youth."

Sally smiled perkily. "Heavy-handed, I'd say rather," she murmured.

Her father winced, rubbed his shoulder.

"About my allowance," she continued. "Do I, or don't I?"

"Not another cent!" he spluttered. Then he caught her eye. "It's blackmail," he howled.

"Of course it is," she agreed sweetly. "I learned that from you, darling. I'm sure you wouldn't want me to mention this little scene I just witnessed. Think how Jericho Foote would love to hear—"

"Don't you dare! What's your price?

"One thousand per month."

"Trying to ruin me? I won't do it—"

"Mr. Foote's such a sweet old thing," she murmured. "I'm sure—" Simeon groaned. "To think I've nurtured a thingumgig of a Jovian dikdik in my bosom. I surrender, child; but beware—"

She kissed him on the forehead. "Darling, when yon find that young man, will you let me know?"

He stared hard at her. "So-oh! I'm to get a son-in-law who uses force and violence on me?"

"Don't be horrid, dad!" slue flashed indignantly. "You're just trying to get back at me. It's utterly ridiculous!"

WHOLLY unaware of the complicated series of wheels he had just set in motion, Kerry Dale walked disconsolately along the back streets of Megalon, the great new metropolis that had sprung up in the central prairie lands. His hotheadedness had gotten him into trouble again. It wasn't enough he had lost his job but maltreating the great Simeon Kenton the way he did meant he would be blacklisted in every law office from Earth to distant Ganymede. He was through; washed up! His career was over before it had well begun.

His wandering feet brought him unawares into the suburban district close to the great rocket-port, where every narrow alley held three saloons and half a dozen dives for the benefit of hard-bitten spacemen looking for a spree and a chance to dump the earnings of an entire voyage in a single mad release.

That was what he needed now—a drink!

The light cell scanned him approved his lack of weapons and police disk, and swung the panel open to admit him.

There were half a dozen men drinking at the bar. Burly tough-looking eggs with that peculiar deep-etched tan upon their faces that came only from long exposure to the penetrating rays of space. Kerry shoved up alongside, said: "A double pulla, bartender. And start another one going on its heels."

The bartender looked at him curiously whipped the drink into shape and set it before him. Kerry eyed the pale, watery liquid grimly downed it neat. "Hurry that second one," he commanded.

The nearer man leaned toward him. "That's powerful stuff to handle, son. You're liable to go out like a meteor."

"What's the difference!" Kerry said bitterly.

"Uni—I see. Troubles, eh?"

"Just that I lost my job. And there won't be any other."

The man's eyes brightened. He scanned Kerry up and down with manifest approval.

Kerry downed his second morosely. "Thanks for your approval," he said shortly. "But I didn't ask—" The man came confidentially closer. "Lost your job, eh? Too bad! Wouldn't by any chance be looking for another?"

"There aren't any others," Kerry retorted gloomily.

"Tsk! Tsk! How you go on! Here I'm making you a proper offer and you as much as tell me I'm lying." Kerry stiffened. The pullas was taking effect. If made him curiously springy and lightheaded. "What kind of job?"

"A nice job; a lovely job. Join a spaceship and see the Solar System."

"Oh!"

"What's the matter with a space job?" the man demanded belligerently.

"Nothing; except I'm—"

"This here one I'm offering don't require no experience. Cargo handler. Just a couple o' hours work loading and unloading—the rest of the trip you're practically the ship's guest."

"Well, I—"

"Look, matey. The ship's due to blast off in an hour. She's all loaded and battened down. Jem here's top kicker of the handlers. One o' his men just busted a rib; that's why he needs another man pronto. What d'ye say?"

Kerry considered. And the pulla considered with him. It was quite a comedown—from legal light to cargo wrestler. But what the hell! It was a job; and his funds were out.

A flicker of wariness came to him. "What's the name of the ship?" The first man turned to his companion. "I offer him a job an' he goes technical on me," he complained. He turned back to Kerry. "What's the dif, matey, if she's the Mary Ann or Flying Dutchman?" Kerry wobbled a little and considered that gravely. The more he thought of it, the more it sounded like brilliant sense.

"Done!" he said suddenly.

The man slapped him on the back. "That's the spirit. Bartender, three pullas. Make one double-strength." Twenty minutes later Kerry's guides and mentors helped his weaving feet out toward the rocket-port, shoved him half up the gangplank that led into the bowels of a space-scarred freighter. Its squat flanks were all battened down except for this single bow port, and the cradle on which it rested had swung slowly into the blasting-off position.

Jem, the cargo boss, helped him along. "In you go, son. Gotta hurry now."

Kerry blinked owlishly at the faded lettering along the bow.

"Flying Meteor," he read. "A very good name," he approved with drunken gravity. "A most—"

"Come along," Jem said impatiently.

"Flying—Hey!" Kerry was cold sober now.

"What's biting you?"

"Flying Meteor. Holy cats! That's a Kenton freighter!"

"Sure it is. And why not? Kenton ships're the best damn ships in space. Now will you come—"

"Not me. I don't ship on a Kenton ship. Not if it's the last job on Earth. Here's where I get off."

"Oh, you do, do you?" growled Jem. He shoved suddenly; and Kerry, off balance, went flying into the hold. The gangplank hauled away, the port slid shut; and the rockets went off with a roar and a splash. "You signed up for the voyage, son; and that's that."

The Flying Meteor was bound for Ceres, largest of the asteroids, with a cargo of power drills, high explosives, detonators and miscellaneous mining equipment. Ceres was the port of entry for the entire asteroidal belt. Through its polyglot, roofed-in town of Planets streamed all the commerce of that newly exploited sector of space.

For many years since the first exploratory flights no one had paid much attention to the swarms of jagged, rocky little planetoids that filled the gap between Mars and distant Jupiter. They held no air, no vegetation and their bleak stone surfaces looked uninviting to pioneers in a hurry to get on to the more hospitable ground of the Jovian satellites. The Martial Council took formal possession of the four largest—Ceres, Pallas, Vesta and Juno—more for astronomical outposts than for purposes of exploitation. The others were left contemptuously alone.

That is, until a particularly inquisitive adventurer smashed head-on into an eccentrically rotating bit of flotsam not ten miles in diameter. If he hadn't been carrying a cargo of atomite at the time, it wouldn't have proved anything except that he was a bad navigator and that no funeral expenses were required. But when the space patrols reached the spot they found no hide or hair of adventurer or ship and about a million meteoric fragments in place of the asteroid. And every fragment was a chunk of solid nickel steel, generously interspersed with glittering rainbow flashes of diamonds, emeralds and rubies. The nickel steel on assay proved immediately workable—a find of the greatest importance in view of the depleted mines of Earth. Mars, curiously enough, had plenty of copper, but no iron. As for the precious gems, they could be used in barter with the web-footed natives of Venus. Those child-like primitives took an immense delight in glittering baubles of that sort.

Whereupon there was an immediate rush to the Belt from all over the System. It was the kind of a rush that harked back to the first gold stampedes on Earth to California and the Klondike, to the initial space-hurtling to the Moon when rocket flight became a reality. And, as in all rushes, the pioneers, insufficiently prepared against the rigors of space and the dangers of the Belt, starved and suffered and fought among themselves and found death instead of riches.

Not every rocky waste held within it the precious alloy. Not one in a hundred, in fact. And the lucky miner, as often as not, had his claim jumped, his first load—blasted out with infinite pains—hijacked and his bloated body tossed into the void. If he survived the initial dangers, then he discovered that it took capital to work his find and transport the metal back to Mars and Earth. Lots of capital. And the men of wealth, like similar men of wealth throughout the ages, demanded so huge a slice of the take and their contracts were so cleverly complicated that the unfortunate prospector invariably found himself rather bewilderedly retired with a condescending pat on the back to the joy places that had mushroomed on Planets, there to rid himself of a modest pension as fast as he could.

Simeon Kenton hadn't come in with the first predatory rush of the men of wealth. He disapproved of their tactics and his disapproval, at first violent with expletives against such slimy snakes as Jericho Foote, of Mammoth Exploitations, took finally the cannier form of preying on them. By means of his superior resources and cleverer lawyers he formed holding companies, took assignments of seemingly worthless rights from disgruntled miners and then fought the men of wealth through every court in the System until they were bankrupt or glad to sell out for a song; he merged and bludgeoned and purchased until more than a third of the wandering planetoids were under his control by outright ownership or option. Mammoth Exploitations, his closest competitor and special bÍte noire, held no more than a fifth. Scattered smaller companies and individuals accounted for another fifth; the remainder were still in the public domain, subject to proper filing claims.

KERRY DALE soon found that life as a cargo wrestler was not all beer and skittles. Jem and his very suave companion—who proved to have been a space crimp and who discreetly disappeared to continue his trade after snaring Kerry—had been a. trifle reckless with the truth. To call it practically the ship's guest during a trip required a peculiar sense of hospitality.

No sooner had the ship blasted off than they set him to work. And what work! Scrubbing and scouring and restacking bales and cases every time the freighter took a steep curve—which was often—and the loose-packed cargo obeyed the law of inertia and tried to keep head-on in a straight line; running errands for the officers and opening tins of food for the cook and yessiring even the rocket monkeys and hunting for nonexistent left-handed ether-wrenches while the dim-witted spacemen snickered and grinned all over their idiotic faces.

Kerry had sobered fast enough. He demanded to see the captain at once. The captain was a man of few words. He cut short Kerry's own flow of explanation. "Put this blasted swab into the brig," he roared, "without food or water until he's ready to work. And if he bothers me again, I'll make rocket fuel of him."

"Yes, sir," said Jem discreetly and yanked the indignant new cargo handler out of the captain's way before he could say or do something really rash.

"He can't talk to me that way," exclaimed Kerry. "I'm a lawyer and I'll see him and his blasted boss——"

"Look, son," said Jem, who wasn't a bad fellow at heart, "don't get yourself into a lather. If you're really a lawyer—"

"Of course I am."

"Then you ought to know something about space law. You signed the articles and you're bound by them for the duration. A captain has power of life and death on a trip."

Kerry paused. "Yes, I know. I must have been drunk when I signed."

"You were," Jem told him feelingly. "The way you downed those pullas——"

Kerry brightened, "O.K., I'll be a sport. I'll do the work. But as soon as the trip is over, I'll tell that roughneck captain a thing or two."

"Better not," advised Jem. "You'll be under him for a whole year."

"What?"

"I told you you were drunk. That contract was Standard Form No. 6. One year on the space ways."

Kerry's jaw went hard and his eyes blazed. "Old Fireball won't want me in his employ that long," he said grimly. "Not after what I had just got through telling him in his own office. In the meantime, Jem, bring on your work."

It was brought on in a way that surprised even that lithe, athletically fit young man. But he didn't complain and by the end of the voyage he was on good terms with most of the crew and particularly friendly with Jem. And even as he wiped smudgy designs on his perspiring forehead with the back of his hand he schemed and planned.

THE Flying Meteor had no sooner dropped into its landing cradle at Planets and discharged its cargo, and asteroidal leave been granted its crew for the space of a day, than Kerry Dale hustled over to the office of the Intersystem Communications Service.

A most superior young lady looked at his still-smudged countenance with a lofty air. She patted the back of her hair-do with violet-manicured hand and said yes? with that certain intonation.

"Never mind the act," Kerry advised. "I want to send a spacegram to Simeon Kenton, of Kenton Space Enterprises, Megalon, Earth."

The young lady was indignant. Imagine a low-bred cargo shifter talking to her like that! She tried to freeze him with a glance, but the smudged young man refused to freeze. Whereupon she stared pointedly at his grimy hands, his single-zippered rubberoid spacesuit.

"The minimum for a spacegram to Earth is thirty Earth dollars," she said frigidly. "In advance."

He grinned at her; and his grin somehow made her forget her superiority. "Don't let that get you down, sister," he smiled, leaning confidentially over the stellite desk. "This one's going collect."

"Oh!" she gasped, and the melting thing she called a heart congealed again. "As if Mr. Kenton would honor your spacegram. As representative of the Intersystem Communications Service I must definitely refuse to—"

He leaned closer to her. "Don't—" he whispered.

"Don't what?"

"Don't refuse. Read Section 734, Subdivision 22, Clause A, of the Interplanetary Code. It says that should an officer or employee of any communications service engaged in the transmission, transference or forwarding of interspace messages refuse to accept any message properly offered for such transmission, transference or forwarding by any company, individual or individuals, the said officer or employee shall be liable to a fine of ten thousand Earth dollars or fifteen thousand Mars standard units, half of which shall be paid over to the aggrieved party. How would you like to pay that fine?" he asked her.

She was flabbergasted. A cargo wrestler, lowliest of spacemen, quoting law to her, with chapter and verse! Then she rallied the tattered remnants of her dignity. He must have read that in a communications office somewhere. The extract by law was posted prominently. She sniffed.

"That's silly," she said. "A message to be properly offered roust be paid for."

"Sure! Kenton will pay for it."

"He won't," she retorted. "And, anyway, how do I know?"

"Section 258, Subdivision 6, Clause D, which says, in short, when a member of the crew of any spaceship is lawfully on voyage to any planet, satellite or asteroid, and an emergency arises, he may, at his employer's expense, send such spacegrams, televised communications or other messages as may to him seem proper for the resolving of the emergency. I, my dear young lady, am a member of the crew of the Flying Meteor, just landed; said Flying Meteor belonging, as you. ought to know, to old Simeon himself." Kerry fished out his identification tag, exhibited it. "Now do you, or don't you?"

"I... I suppose so," she said weakly. She was getting a bit seared of this incredible space roustabout.

"Good!" He flung her a slip of paper. "Send this off. When the answer comes, send it on to the Flying Meteor, Landing Cradle No. 8."

By the time she started reading the message he was gone. As her eyes moved over the lines they became glassy, wild. She said: "You can't say anything like—" But she was talking to herself. The office was empty. In a panic she buzzed the visiscreen for her chief. He was out. All responsibility rested on her. Perhaps she should screen the main office on Mars. But that would take a few hours; and that terrible young man would quote another passage from the Code at her, relating to delays in transmission. Nervously she started the peculiar message on its way.

SIMEON KENTON was engaged in another verbal bout with his daughter. It meant nothing. They both enjoyed it. Old Simeon fussed and fumed and Sally got her way. Which was as it should be.

This time it was about her getting a little space knockabout with a cruising range to the Moon. "It's ridiculous!" he yelled. "And downright dangerous. Why can't you use my piloted machine?"

"Because I don't like Ben Manners, that stodgy old pilot you insist on keeping. Manners, indeed! He hasn't the manners of an old goat."

Simeon was shocked. "Such language, Sally! Fin surprised. Where do you learn such—"

He saw her impish twinkle and stopped in time. "Anyway," he added hastily, "it's dangerous."

"You know I've a Class A license, dad. If the Space-Inspection thinks I'm competent enough to go to Jupiter, certainly I don't see why—"

The visiscreen buzzed. "Message for Mr. Simeon Kenton; message for Mr. Simeon Kenton."

Simeon flung the switch into receptor range. "O.K. Go ahead."

The Megalon operator of the Intersystem Communications Service appeared on the screen. He looked nervous. "It's from Planets, sir."

"Ha! Must be the Flying Meteor. Shoot!"

"It... it's collect, sir."

"The devil! Since when does Captain Ball send collect? Don't he carry enough funds?"

"Maybe there's trouble," Sally suggested.

"The devil you say!" Simeon was startled. The Flying Meteor carried a valuable cargo. "Well, go on there, you!" he roared into the screen. "Don't be keeping me on tenterhooks. What's it say?"

The operator was plainly ill at ease. He cleared his throat. "This... uh... message... uh... our company takes no responsibility for—"

"Who the blazes asks you to?" roared Simeon. "It's for me; not for you! Now, hurry up, or by the beard of the comet—"

The operator began to read hastily.

SIMEON KENTON.

KENTON SPACE ENTERPRISES, MEGALON, EARTH.

DEAR OLD FIREBALL:

HA HA HA. SO YOU THOUGHT YOU FIRED ME? TAKE ANOTHER GUESS. BACK IN YOUR EMPLOY IN CREW OF FLYING METEOR. HAVING A WONDERFUL TIME WISH YOU WERE HERE. AND DON'T THINK YOU CAN FIRE ME AGAIN. I HAVE IRONCLAD CONTRACT FOR ONE WHOLE YEAR. I CAN'T STOP LAUGHING.

KERRY DALE.

Sally began to snicker as the operator gulped on and on. Simeon's face turned a mottled red. His angelic whiskers and the thin white wisps on his head grew so electric she could almost see the sparks jumping from one to the other.

"Stop!" he roared.

The operator stopped.

"Is he really back on your payroll, father?" Sally asked innocently.

He glared at her. "Quiet! Of all the insufferable impudence, the ratgosted, blatherskited ripscullions!"

"Father, your language! It's not even English!"

The operator said timidly. "Any reply, Mr. Kenton?"

Simeon whirled on the screen. "No!" he shouted. "I mean yes! Take this message. Kerry Dale, wherever the blazes you are, you're not—"

The operator paused in his writing. "Uh—is that the address?"

"It ought to be. Bah! You know the blamedadded address, don't you? Then put it in and stop interrupting me.

KERRY DALE,

ET CETERA. ET CETERA.

YOU'RE FIRED AND I MEAN FIRED. TO BLAZES WITH YOUR CONTRACT! I'LL FIGHT YOU ALL THE WAY UP TO THE COUNCIL AND DOWN AGAIN.

KENTON.

"There, that will hold the young flipdoodle. Back in my employ, huh!"

"I wonder," murmured Sally.

"Wonder on."

"I wonder if he doesn't want you to fire him. He looked like a pretty smart young man to me. In that ease, knowing you—as who doesn't?—that would be just the kind of a spacegram to—"

Simeon looked startled. "By gravy, Sally, maybe you're right! Hey there!" he yelled into the screen. "Skip that reply. Take another, addressed:

CAPTAIN ZACHARIAH BALL.

FLYING METEOR, PLANETS, VESTA.

HAVE YOU YOUNG SQUIRT IN CREW NAME OF KERRY DALE? IF SO REPLY FULL DETAILS.

KENTON.

A FEW hours later came the answer. Sally had waited for it. She was intensely interested. She told herself it was because she enjoyed watching her esteemed, lovable old parent fuss and fume, and because no one had ever dared stand up to him as this young man was doing. If there was anything deeper in her interest, she wouldn't admit it even to herself.

Captain Ball was brief and to the point.

KERRY DALE MEMBER OF CREW FLYING METEOR. CARGO HANDLER, STANDARD CONTRACT No. 6, SIGNED UP MEGALON WHILE DRUNK. GOOD MAN BUT ALWAYS ARGUING ABOUT RIGHTS. REGULAR SPACE LAWYER. SOON TAKE IT OUT OF HIM.

BALL.

Old Simeon rubbed his hands softly. His eyes gleamed. "Cargo handler, hey? The toughest, orneriest job in the whole System? Old Fireball, am I?"

He snapped the office of his lawyer in chief onto the screen.

"Yes, sir?" Horn inquired respectfully.

"About our employment contract, Form No. 6, how ironclad is it?"

Horn stroked his jowls complacently. "Not a loophole, sir, from our point of view, that is. We just redrafted it about six months ago. The Kenton Space Enterprises binds the employee to everything and is bound practically to nothing."

"Can the employee break it?"

"Break it!" Horn chuckled. "Not unless he wants to pay triple his wages as and for liquidated damages and be enjoined for the space of five years thereafter from engaging in any gainful employment. Oh, it was carefully drawn, I assure you." Kenton rubbed his hands very hard now. "Good! Excellent! I must say it was about time you began to earn that outrageous salary I'm paying you."

Horn preened himself. Coming from Simeon Kenton, this was indeed praise! "Well, sir, I'm glad you think—"

Suspicion glowed suddenly in Simeon's eye. ""Hey, wait a moment. Did you personally draft that contract?"

Horn deflated. "Well... uh... that is—" he stammered.

"Ahhh! It was that dingdratted Dale, wasn't it?"

"Well... uh... you see—" But Kenton, had already wiped him off the screen with a violent gesture.

"There, you see," Sally exclaimed happily. "Everything's worked out just fine. Kerry Dale's back in your employ whether he wants to or not. All you have to do is put it up to him. Come back to your legal department, with a raise, or stay on as cargo handler. Surely he'll—"

She stopped. When her parent looked as unbearably angelic as he did right now, he had something particularly devilish up his sleeve. She was right.

"Oh, no, child. Kerry Dale is staying right where he is. He made a contract and he's going to live up to it."

Sally felt suddenly sick. This was no longer fun. The thought of that very determined, intent young man, whom she had seen only once and who hadn't even looked that once at her, wrestling with staggering loads and living in grubby spaceship holds for a year did things inside of her.

"You're taking a mean revenge, dad," she exclaimed. "You can't—"

He put his hand against her cheek, stroked it gently. His eyes softened. "You like him, don't you, child?"

"No—that is, yes—I don't know.

He didn't even see me."

"Let me handle him, Sally. It will be a good experience. If he's got the stuff in him, this year will bring it out. There's nothing like space for making or breaking men. If he breaks, then we'll know—you and I. If he doesn't, then we're both sure about him."

KERRY DALE sweated and strained at the huge chunks of ore that were rapidly filling the hold of the Flying Meteor. The sweat streaked down over his half-naked body and dripped from under his rubberoid pants. As he heaved and juggled, he wondered. Three days had passed since he sent that impudent, carefully deliberated spacegram to Old Fireball and nothing had happened. It didn't sound right. By all accounts that most irascible old man should have promptly exploded and fired him by return message—which was just what Kerry had counted on. A horrible thought came to him. Had the girl in the office double-crossed him and not sent off the spacegram? His jaw hardened. "If she hadn't, he—

Bill, the shipboy, came whistling into the hold. "Hey, Kerry, the cap'n wants to see you. Gee, you must of done somethin' terrible!"

Kerry's fellow handlers stopped work, made ducking sounds of pity. When the captain sent for one of their kind, it meant only one thing—trouble!

Jem said anxiously: "For God's sake, Kerry, whatever it is, don't try to talk back, or you'll land up in the Ganymedan hoosegow. And that ain't no place to be. I've been there," he added feelingly, "so I know."

But Kerry threw down the piece of ore he was handling with a contemptuous clatter. Exultation filled him. He laughed at their anxiety. "So long, fellow slaves!" he waved to them. "I'm through; washed up. I've been waiting for this call. Next time you see me, call me "Mister". I'll be a free man, free of Old Fireball and his lousy ships. Bon voyage, mes pauvres."

They stared after his swaggering exit. Jem shook his head and looked anxious—

Captain Ball greeted his cargo handler with a smile. It was a grim smile, but Kerry didn't note that. All he saw was the spacegram in the captain's hand.

"This is for you, Dale," purred the captain. "Direct from Mr. Kenton, himself."

"Direct from Old Fireball himself?" said Kerry jauntily. "Very sweet of him to fire me in person. Tsk! tsk!"

He spread out the spacegram; read:

DALE:

FIRE YOU? NOT AT ALL. GLAD TO HAVE YOU IN EMPLOY AS CARGO MONKEY. SUITS YOUR TALENTS PERFECTLY. ONE WHOLE YEAR!

KENTON.

Kerry was shocked; more, he was dumfounded. The old scoundrel! He could see him laughing fit to kill in that office of his. He had outsmarted Kerry. A whole year doing this rotten. jumping job! He'd be damned if—"

Captain Ball said grimly: "It may interest you to know that I also received a spacegram. I'm to make—you toe the mark." He laughed nastily. "As if I had to be told that. Now get back to your work, you ether-scum, and don't let me catch you laying down on it or I'll put you in irons with extreme pleasure. Git!"

Kerry got. It was a much sadder and wiser young man who came back into the hold to meet the queries first, then the gibes of his shipmates.

"Mister Kerry Dale!" mimicked one. "He ain't gonna be no slave no more, nohow. No, siree. He's gonna tell Captain Ball and Old Fireball, too, just where they get off. Yes, sirree."

"Lay off the lad!" commanded Jem sharply.

Kerry grinned painfully. "Let them talk, Jem. I've got it coming to me. I thought I was smart." Then his jaw squared, "But I'm not through yet, not by a long shot."

"Good lad!" approved Jem. "Now about that load over there—"

THE Flying Meteor cleared for Earth: picked up another cargo, returned to Vesta. Kerry had never worked so hard in his life. He gained a new respect for the brawny spacemen and their ability to take it. He was fast becoming one of them himself. The rough work hardened and deepened him and he gained the saddle-grained tan that was the hallmark of all the men of space.

Captain Ball rode him: but there was no persecution. No excuses were permitted; no extra shore leave granted him, as sometimes happened to the other members of the crew. The letter of the contract was religiously upheld.

He didn't have a single comeback, Kerry reflected bitterly. He had drawn that blasted contract only too well; so well that even he couldn't find a single loophole in it.

The first resentment passed. Old Fireball had hoisted him with his own rocket, and that was that. But he was determined before the year was up to make the chortling old man regret the day he had triumphed so easily over him. Just how he'd do it, he didn't know as vet. But his brains worked overtime, seeking opportunities.

In Megalon he saw a telecast. It was the only recreation he could manage in the six-hour shore leave his contract called for. The feature —a rather dreary tale of adventure on a still-unexplored Saturn—bored him. The way these writer chaps dress up space life! I bet not one of them ever set foot on a spaceship. Then the news program flashed on:

"And now," said the announcer, "we'll show you Miss Sally Kenton, the beautiful, high-spirited daughter of Simeon Kenton, and sole heiress to all his millions. She's about to take off for the Moon in her new, special-job flier. It's a honey, as you'll see immediately for yourself; and—I don't mind telling "you—so is she. In addition to her other accomplishments Miss Kenton is the only woman holder of the Class A Flight License."

"Huh!" snorted Kerry in the depths of his seat. "Her old man's pull got her that. And why is it that every girl who's born to millions is beautiful, according to the announcers. I bet she's cross-eyed and bowlegged and—"

"Shut up!" Jem said genially. They had gone together. "Did you ever see her?"

"No; and I don't want to."

"Well, I have. On the telecast, that is. But here she is."

The rocket field swain into view. The one-seater flier gleamed and sparkled with sleek stellite. It was a beauty. But Kerry jerked upright in his seat at the sight of the girl who stood at the open port. Her windblown hair rippled in the sunshine; her piquant face was smilingly turned toward the visiscreen.

"Well?" murmured Jem admiringly. "Cross-eyed, hey? Bowlegged?"

"Holy cats!" breathed Kerry. "I... I thought, she was Old Fireball's secretary."

Jem snorted. "She don't have to work. Even if she wasn't born to money. Not with those looks!" But Kerry wasn't listening. Even after the newscast shifted elsewhere he sat in a daze. He had dreamed of that girl. Even though they hadn't said a word to each other. And now his dreams collapsed. Aside from everything else—he had used violent hands on her father, and even more violent words. Oh, well, the hell with it! Might as well be hung for a wolf as for a sheep. He'd show the precious pair of them a thing or two before he was through.

But two more trips intervened, and a month had passed; and still he was a wrestler of cargoes. He cudgeled his brain and he utilized every spare shore leave to seek opportunities for striking back at that smug Old Fireball. He drew only blanks.

THEN, back at Planets again, there was a hitch. They were due to pick up an especially fine load of high-grade electromagnetite. Back on Earth this alloy of rare metals cost a hundred dollars a ton to produce and industry clamored for all it could get. The new atom-smashers that powered the world's work were lined with the alloy. Nothing else could withstand the terrific explosions of bursting atoms.

Only two months before, however, one of Simeon Kenton's exploration expeditions had found an asteroid on the very outer verge of the Belt, not far from Jupiter itself, which was practically sheer electromagnetite. The asteroid was small, yet the experts figured it at sixty thousand tons of workable metal. At a hundred dollars a ton—

"Lucky stiff!" stormed Jericho Foote, of the rival Mammoth Exploitations, and sent a ship posthaste to chart every asteroid in the vicinity of the find. The expedition came back with sad news. There were plenty of asteroids, all nicely mapped and orbits plotted; but nary a one was anything but useless burnt-out slag and rock. And there the matter had dropped.

This was the first load that had been mined. And the fat-bellied, slow-moving scow that was freighting it to Vesta for transshipment to Earth on the Flying Meteor had broken down in space about a million miles from Vesta. A radio flash came in, calling for a tow. A tow-ship, with special magnetic grappling plates, started out. It would take almost a week before the crippled ship would come in.

Captain Ball swore deeply, but there was nothing else to do but wait. Perforce he gave his crew shore liberty. He was so upset by the mishap that he forgot to exclude Kerry Dale from the coveted leave.

So that Kerry found himself wandering the inclosed streets of Planets, seeking something to do. There was plenty to do, if you cared for that sort of stuff, Joy palaces, drink dives, gambling layouts, honkatonks, razzledazzles—all the appurtenances of a System outpost calculated to alleviate the boredom of space and wrest away from its wayfarers the hard-earned pay they had accumulated.

The crew of the Flying Meteor went to it with whoops of joy and a spray of cash. Even Jem, ordinarily sober and steady, fell for the lure.

"Come along, Kerry," he urged. "It will do you good. Cap Balks liable to wake up any moment to the fact that you're included in the leave."

Kerry shook his head. "Not me, Jem. I still remember how I got so drunk I didn't know what you gave me to sign."

Jem looked pained. "You aren't holding that against me, lad?"

"Not at all. That was your job. But I've got other fish to fry; and I've a hunch that somewhere on Vesta I'll find both fish and frying pan."

So he walked the streets, heedless of the siren calls from overhanging windows, thinking hard. He simply had to get back at that old rascal, Simeon Kenton. But how?

This discovery of his—electromagnetite? Six million dollars worth of stuff dumped into his lap. Could anything be done about that? He couldn't see how. The claim of ownership to the asteroid had been filed. Properly filed, without doubt, Kerry remembered the meticulous care they had used back in Horn's office to check on every claim. Horn was a pompous old ass, but he knew about mining claims. There'd be nothing there.

Still—it wouldn't hurt to take a look. Might as well, in fact. Planets wasn't built to provide distractions for men of his stamp. So his feet moved him rapidly toward the Bureau of Mining Claims and Registrations.

VESTA had jurisdiction over the entire Asteroid Belt, Every claim, every title, had to be registered there to be valid.

Dale walked into the Records Department, asked to see the file on Planetoid No, 801. This was the way Kenton's find was listed—the jagged little bit of metal was too tiny for a name.

A can of film was handed Dale and he was given a projection room in which to examine it. Carefully he studied the elements of the claim on the projection screen, running it over and over.

After an hour, he gave it up with a sigh. The chain was air-tight and space-tight. Horn had done a proper job on it. Old Fireball would hold title until Kingdom Come. Every possible contingency had been provided for. Prior liens, mineral rights, space above and core beneath.

Glumly he turned the can back to the clerk. The clerk said conversationally: "Lucky guy, that Kenton."

"Yes."

"Jericho Foote's been taking a fit. He must of spent a cool hundred thousand on that expedition of his alongside. All he brought back for it was a beautiful chart of that whole sector of space."

Kerry said suddenly: "Got it here?"

"Sure. All those things go on file. Want to see it?"

"Might as well, I've got nothing else to do."

The clerk examined him curiously. To outer appearance, in his rubberoid suit and calloused hands, Kerry was just another cargo wrestler. Nothing else to do in Planets, huh?

Feeling a bit offended in his local pride the clerk withdrew, returned with a larger can.

Kerry took it into the projection room.

It was a beautiful chart, he acknowledged. Foote had sent along one of the best cartographers in the System. Every sector was carefully plotted, every asteroid, every speck of space dust put in its proper place and the elements of its orbit set forth in measured tones.

Idly, Kerry checked some of the orbits on a scratch pad. Back in college, before he had gone in for law, he had been pretty good at space mathematics.

He plotted a few of them, for no special reason, but just to see if he still knew how to do them. He did.

The courses were pretty complicated, what with Jupiter, Mars, the Sun and all the other asteroids pulling on each other. The orbits did loops and curlicues and led nowhere in particular. He was about to give it up, when he came across a somewhat larger bit of flotsam, perhaps a mile across at its greatest diameter. According to the accompanying data it was an arid waste of congealed lava, with a pitted, glassy surface. Nothing on which to waste a second glance. Yet there was something curiously familiar about the elements of its orbit. He stared hard at them. Where had he seen similar ones?

He riffled through the sheets of his scratch pad, stopped suddenly at his figures on Planetoid No. 891. There it was. Allowing a differential angle of six degrees to Plane Alpha the two sets of elements might have been twin brothers.

An idea groped in the back of Kerry's head. He began to plot the course of the second asteroid, No. 640. His pencil raced and his brain raced. His excitement mounted as the complicated elements unfolded. Checking each set against those of No. 891, it seemed—it seemed—

The last equations were down, the spacegraph drawn. Feverishly he superimposed the twisting curve on That of No. 891. If his first approximation was correct, the two asteroids should collide on December 17th, Earth Calendar. It was now December 13th!

He went to work again rapidly, taking successive approximations. Then he was staring blankly at the curves. The sweeping lines approached each other, closer, closer, so close that they practically brushed; then swung away in widening loops to separate sectors of space. Practically brushed each other; but not quite. His first approximation had shown actual contact. The final figures disclosed a distance of three miles at the point of closest approach!

Three miles is not much; but when one deals with two bits of rock, one not more than two hundred feet in diameter, and the other about a mile, and both hurtling along at speeds of several miles per second, three miles becomes a yawning, unbridgeable chasm. There would be no collision!

The vague idea, that had been burgeoning in Kerry's head collapsed. Another scheme to do something about Old Fireball's victory over him died a-boming. He was licked again.

He sat there, staring at the figures as though he could by the mere act of concentration shift them just the slightest. Three measly little miles! So near and yet so far. If only there was a, way—

He whooped, and the echo in the confined projection chamber startled him. It was a long-shot gamble. There were half a dozen incalculable factors, each of which had to fall neatly into place; but he'd be damned if he wouldn't try it.

Very casually he returned the can of film to the clerk. Even more casually, though his heart was hammering, he asked for the Claims Registration Book.

His finger stopped at Planetoid No. 040. The registered owner was one Jake Henner, and his official address was the Gem Saloon, Planets. Vesta.

"Got what you were looking for?" asked the obliging clerk.

Kerry found it hard to keep his face blank. "Wasn't looking for much," he said. "Thanks!"

BUT out in the street Dale hailed a swift little gyrotaxi. "Gem Saloon!" he snapped. "And never mind the speed limits."

"What a break! What a break!" he exulted to himself. "Imagine if the owner had been old Kenton or Mammoth or some guy who lived on Venus!"

"Here y'are, buddy," The gyro-driver came to a halt. "The Gem Saloon in four minutes flat. And I got me a fine, too. Doing a hundred an' twenty on a city street. See up there!"

Kerry looked obediently at the little oblong screen above the dashboard. On it, flashing neatly, was imprinted a summons for violation of the traffic laws. The photoelectric cells at each crossing had docked the gyro's speed. As it passed the legal limit, the automatic mechanism recorded the offender's license, sent out the impulses that printed the summons in the offender's cab.

"What'll the fine be?"

"Ten bucks."

Kerry fished in his pocket. "Here it is, and the fare and a tip. It was worth it."

"Gee, thanks!"

The Gem Saloon was on the outskirts of Planets. It wasn't one of the higher-class razzledazzles. It was just a cheap joint in a cheap neighborhood. Which, strangely enough, pleased Kerry no end.

He went in. A couple of shabby men were drinking rotgut brew. A frowsy-looking bartender with a dirty, slopped-over jacket was lackadaisically leaning an elbow on the bar. Business was not so good.

"Where can I find Jake Henner?" asked Kerry.

The bartender did not even shift his glance. "You're looking at him right now, buddy. An' I don't mind tellin' you meself he ain't much tuh look at."

"Not so bad, Mr. Henner," Kerry said critically.

"Just call me Jake. If it's a drink you want, speak up. If it's money, you're wasting your time."

"I'll take the drink: and maybe I'll give you money, Jake."

The man perked up. He slopped some firewater into a dirty glass, set it before Kerry. "Say, mister, don't give me heart failure, speakin' so easy-like about money. They's gonna throw me outta here soon if I don't pay the taxes."

"You registered Planetoid No. 040 in your name, didn't you?"

The eager look died. "Yeah!" he said bitterly. "Coupla years ago me an' a pal got ourselves a grubstake an' went prospectin'. Didn't find a damn thing. The pal ups an' blows hisself tuh bits on that blasted little speck o' nothing. There wasn't anything left tuh bring back tuh bury, so I sorta registered the rock for his sake, me bein' sentimental-like."

"And a very good sentiment, too," approved Kerry. "You wouldn't want to sell that bit of sentimental desert for fifty bucks, cash?"

Jake looked suddenly suspicious.

"Whoa there!" he exclaimed, "There ain't been somethin' found there what I don't know about?"

"Don't be silly," Kerry told him severely. "Did you find anything? Did the Mammoth crowd who landed there find anything?"

"No." Jake scratched his head. "Whatcha want it for, then?"

Kerry leaned over the bar; whispered. "I'm a spaceman, see! I get chances to pick up things here and there; and I need a place to cache the stuff until I can get it away safely. Of course, if you don't want to sell No. 640, that's all right with me. It's convenient, but there's a hundred other asteroids just as convenient."

"Make it two hundred bucks."

"Seventy-five."

"One fifty, mister, and the deal's closed. So help me, I need—"

"One hundred," Kerry told him firmly, "and not a penny more. It's found money for you."

"Gimme!"

"After you sign the proper papers, my dear Jake."

TWO hours later Kerry was the sole and legal owner of Planetoid No. 640, with all the rights, appurtenances, hereditaments and easements accruing and adhering thereto. Step No. 1!

Now for the next and more difficult step!

He reported to Captain Ball.

The captain's eyes gleamed. "Oh yes, Dale. I had completely forgotten. You've been sneaking extra shore leave. Your contract calls only for twelve-hours leave for each week in port. You're already overdrawn, so—"

"Kenton Space Enterprises ought to thank its lucky stars I took the time I did," he interrupted.

The captain stared. "What do you mean by that?"

"Just this. I happened to wander into the Registration Office. Looking at... er... orbital data is a hobby of mine. Used to be good at mathematics; and I like to keep up my figuring."

"Come to the point."

"In due time, captain. Being a loyal employee of Kenton Space Enterprises, Unlimited, I naturally looked at our Asteroid No. 891 first." The captain grunted suspiciously. Kerry paid no heed. "And being properly curious about Mammoth Exploitations, our hated rival, I looked at their futile charts if only to get a laugh.

"Hmm-m!" said the captain. "What's your bloody school work got to do with me?"

"I'm telling you, captain," Kerry smiled sweetly. "If you, or anyone else, would wish to calculate the orbits of our precious asteroid and of Planetoid No. 640 in the same area, you or he would discover, as I did, that they intersect simultaneously on December 17th. And that intersection, Captain Ball, means smash for almost six million dollars worth of firm property, not to speak of the lives of the forty-odd men who are mining the stuff."

Captain Ball said hoarsely: "If this is your idea of a practical joke, Dale—"

"I told you; get the company's experts to check me. There are duplicate charts at Megalon. Tell them to check No. 891 against 640, But, remember, December 17th is only four days away."

The captain was a man of action, "I intend to," he said grimly. "And Heaven help you if you're trying to make me look like a fool!"

But Kerry Dale obviously was not. The ether surged with spacegrams. A frantic message came from Simeon Kenton. Working at top speed, his experts had taken the charted elements of the two asteroids, as Kerry had suggested and, sure enough, on December 17th they would meet in head-on collision.

"Get every man off No. 891," jittered Kenton. "And do something, do anything, to shift that infernal bit of rock away. Six million dollars!"

The captain called Kerry into conference, as Kerry thought he would. His face was a black thundercloud.

""Easier said than done," he growled. "The Nancy Lee's bust in space. All they've got out at No. 891 is a floating shed to house the miners until she comes back. Even if I sent them a radio, they couldn't get away."

"The Flying Meteor, if it starts fast, could get there with some hours to spare," Kerry pointed out.

"I suppose we could," he admitted. "But how about old Kenton's other instructions? What does he think I am—God? I suppose he thinks all I got to do is slip a tow chain around an asteroid, and haul it out of harm's way. Yet if I don't do something, he'll go ranting and tearing around, and I'll be in the soup."

In his unhappiness the incongruity of his thus complaining to a lowly cargo wrestler did not strike him.

"I've an idea, captain, which may or may not work," Kerry said quietly."

THE captain was ready to grasp at straws. Sometimes Old Fireball expected the impossible from his men, and when they didn't or couldn't deliver they heard from him plenty. And it was six million bucks.

"What is it?" he asked eagerly.

Kerry frowned as if in deep thought. "The total mass of No. 891 is only about eight hundred thousand tons, isn't it?"

"Well?"

"A not impossible amount of power, applied tangentially and in the direction of the orbit, could shift it slightly from its course. It wouldn't take much of a shift to avoid a collision."

"True enough," Ball admitted. "But where's the power coming from, and how is it going to be applied?"

"You forget No. 891 is almost solid electromagnetite. If we can set up a powerful countermagnetic field in the immediate vicinity—"

The captain's face cleared. "By Heaven, Dale, you've got something there. Our magnetic tow plates."

"Yes, sir."

"But how much juice would we need? It would be a damn delicate job to give it the right boost."

"Damn delicate, captain," Kerry agreed. "Ill do the figuring, but there are so many complicating factors the whole thing will be a gamble."

"Let it be. We can't lose anything by trying." Captain Ball pressed buttons. Men's faces appeared on the visorscreen, gave way to others. He barked orders. Rush relays of storage batteries on board, additional power units and booster cells. Televise No. 891 to prepare for instant evacuation. Fill all fuel tanks. Stand by for instant takeoff!

He turned to Kerry, stroked his chin. He cleared his throat. "By the way, Dale; about your job. I don't think it will be necessary for you to do cargo hustling from now on. Move your duffle-bag into the bow cabin. You're acting third officer."

"Thank you, captain," Kerry acknowledged gravely. Not until he was safely out of sight did he permit himself a grin. Everything was working out far better than he had dared hope.

The first hurdle had been the experts back on Earth, They had made the very mistake he had prayed they would; the same one he had first been guilty of. In their hurry, and because he had deftly focused their attention wholly on the two small asteroids immediately involved, they bad overlooked the concomitant gravitational pulls of the other small bodies in the vicinity. These were charted with any degree of exactitude only on the Mammoth map. Foote had filed a copy on Vesta because it was the law. Duplicate filing on Earth was a courtesy, and Foote had been in no mood for courtesies.

The second hurdle had been to get Captain Ball to follow his suggestions. Kenton's explosive spacegram, with its seeming grant of unlimited authority, had unwittingly helped.

THE Flying Meteor hurtled the void to No. 801 in three days fiat. They found a bewildered crew of men huddled in the captive shelter, anchored to the rushing little segment of purplish metal by a steel chain, and holding its distance by means of a weak repulsive current. Ail their tools and equipment had been salvaged, and the deep pit in the asteroid showed bare and forlorn.

The transfer of men and materials into the capacious hold of the Flying Meteor was a matter of hardly two hours. Every instant was precious. They could not see the oncoming No. 640. It was still almost half a million miles away, and its mile-wide dullness of dark lava could not be picked up in the deep confusion of the Belt. But they knew it was there and that, in less than twenty-four hours, the two bits of space wreckage would crash. Dale had said so; and he had been confirmed by the men back home.

"Have you worked out the amount of power we need, Mr. Dale?" the captain asked anxiously. "And at what specific point it's to be applied?" It was Mr. Dale now, as became a newly appointed officer.

"Yes, sir." Kerry thrust a sheet of figures at him. "But remember, sir," he warned, "I can't guarantee they'll do the trick. Space here in the Belt is full of conflicting pulls and repulsions. I had to disregard most of them, and pray that they cancel themselves out."

"I know: but we've got nothing to lose by trying. They're due to crash, anyway. Take your figures below to Mr. Carter, and let him get the necessary power up."

Kerry delivered the message. Meanwhile the ship had moved on No. 891's tail, and jockeyed into the exact position he had calculated. Kerry grinned; then grew a bit worried, He had covered himself against seeming failure; which, in fact, from his point of view, would be complete success. For the data he had laboriously compiled would, if everything went right, give just sufficient of a fillip to No. 891's tail to send it delicately grazing against the still invisible No. 640.

But would everything go right? The slightest bit one way would thrust them wholly untouched past each other; the slightest bit the other way would mean a head-on collision, with total destruction of the two compact little bodies. He didn't want that, either.

The power surged and throbbed in the ship's stout steel plates. The engines roared and the boosters thrummed their song. Long, pencil streamers of flame darted from the rocket tubes, checking, accelerating. They were a bare two miles behind the asteroid, itself no larger than the ship, and at the speeds they were traveling, the slightest deviation might mean a terrific crash.

Magnetic currents flowed and crisscrossed the gap. Waves of repulsion that kicked the big freighter, by much the lighter or the two straining forces, right off its course. Each time Carter, the chief engineer, did miracles with the rocket tubes to get them back into line.

The crazy gyrations of the pursuing ship were obvious to everyone on board. But the opposite reaction on the purplish gleam of plunging metal was not so obvious.

THE hours passed, and still no discernible effect could be observed. It was impossible, with the instruments on board, to detect the infinitesimal shift in the angle of flight which was all that was required.

Asteroid No. 040, the villain in the piece, hove into view. It was coming at an acute angle to its prey, cutting sharply in front. Would they collide? Would they not? Would there be a smash? Would they only graze? If they grazed, would they stick; or sheer off again? Questions that tortured Kerry as he watched eagerly. His whole future depended on the answer.

Closer and closer they rushed on each other, with the Flying Meteor like a watchdog snapping at the heels of the smaller one. Closer and closer, while the power surged and repulsions leaped across the void. All hands on board pushed and shoved at the portholes, straining their eyes and holding their breaths.

Six million dollars worth of precious metal hung in the balance!

Closer! Closer! A cheer went up. Jem yelled excitedly: "They're going to clear!"

Kerry felt a little sick. They would clear. He had miscalculated. A decimal place, perhaps, had gone wrong; some force had not been taken into account. Oh, well, he'll get the honor of having saved the asteroid. Old Fireball would have to be properly grateful. But that wasn't what he wanted. He wanted to stand up to the man, not come crawling to him with gifts in his hand.

A great groan went lip. Kerry opened his eyes. He had involuntarily closed them.

The two asteroids, one so relatively large it almost swallowed the smaller, seemed to hang together. No. 891 shivered and dipped. It turned inward.

For one terrible moment Kerry was in agony. They would crash. He, personally, in his anxiety to outsmart Simeon Kenton, had blown to smithereens immensely valuable metal, important to the industries of the System.

Another cry echoed in the hold of the pursuing ship. The two small planetoids, of unequal size, trembled together. There was a little puff of smoke-like lava dust that rose outward in a cloud; the heavier metal of No. 891 ground and scraped tangentially along the surface of No, 640; then both space-wanderers nestled snugly together and rushed on a swerving course, held by mutual pull and the inertia of their common speed.

Captain Ball unbent so far as to shake Kerry's hand violently. "Grand work!" he crowed. "No. 891 is absolutely undamaged. There's a groove on No. 640, but what the hell!

It's just a bit of waste lava. We could leave things as they are; or get some tractor ships from Vesta to help separate them."

"Not bad!" Kerry agreed quietly. "But I think we'd better get back to Vesta and send for instructions before you do anything."

"Of course! I intended that. But you've done a swell job, Mr. Dale. Simeon Kenton will be tickled."

How tickled, the worthy captain had no means of knowing at the moment.

FOR, once back at Planets, Kerry hurried ashore, filed certain affidavits with the startled authorities, then sent a spacegram addressed to Simeon Kenton, President, Kenton Space Enterprises.

It was short and to the point:

AS OWNER PLANETOID No. 640 MUST DEMAND DAMAGES MY PROPERTY DUE TO FALL OF PLANETOID No. 801 UNDERSTAND YOU OWN. ADVICE IMMEDIATELY IF YOU'LL PAY BEFORE SUIT.

DALE.

Back came the blistering reply:

DALE,

PLANETS, VESTA.

YOU'RE DAMN FOOL AS ALWAYS. WAS GOING TO PAY REWARD AND OFFER BIG JOB. NOW YOU CAN GO TO HELL. YOUR BLITHERING ASTEROID VALUELESS, DAM AGE WORTH SIX CENTS. CASH EN ROUTE. WILL FILE COUNTERCLAIM AS SOON AS SEPARATE THE ASTEROIDS AND DETERMINE DAMAGE TO MY OWN.

KENTON.

Kerry's grin was a positive delight. Space surged again.

KENTON,

MEGATON. EARTH.

THANKS FOR THE COMPLIMENTS. SIX CENTS REFUSED. WHAT DO YOU MEAN YOUR ASTEROID? No. 891 MY PROPERTY. READ SECTION 4 ARTICLE 6 OF SPACE CODE. WHO'S DAMN FOOL NOW?

DALE.

Back on Earth old Simeon went into a veritable ecstasy of explosive anger. His epithets burned holes in the office furniture and melted the lucite walls. Even Sally was startled, though she had thought herself thoroughly immune to her estimable ancestor's language.

"What's the matter, dad?" she queried.

He danced up and down the length and width of the office. "That dod-rotted, incinerated, langasted skibberite you think's so grand! Look at this now! Look, I tell you!"

"Don't yell so," she reproved. "You'll break a blood vessel." She took the spacegram from his trembling fingers, "Hm-m-m!" A little smile made impudent curves of her lips. "Have you read Section what-is-it yet?"

Old Simeon glared at her. He slammed open the visorscreen.

"Horn," he barked, "what's Section 4, Article 6 of the Space Code say?"

"Well... uh... offhand I don't know, but—"

"Oh, you don't, don't you? You have to look it up, do you? I bet that ding-the-ding-ding Dale didn't have to look it up. He had it at his fingertips. Go on, look it up! Don't stand there like a bleating doodlebug."

Horn swallowed hard. Within a minute he was back on the screen.

"It reads, sir, as follows:

"When in the event that a freely moving body in space, not artificially produced or manufactured by man or machine, shall fall or in anywise impinge upon the surface of a planet, satellite or asteroid, the said falling body so impinging shall forthwith become the property of the record owner of title to the surface of such planet, satellite or asteroid upon which the same has fallen as aforesaid."

Kenton broke into a delighted chuckle, "Ha! Got that blasted skalawoggle on the hip. Thought he was smart, huh! I've got an asteroid, too. I can claim his fell on mine." He rubbed his hands. "Ill take him all the way up to the highest courts; I'll spend thousands to—"

Horn scowled down at the book in his hands. "If I might venture to suggest, sir—"

"Go on and suggest, Horn." Old Simeon was in high good humor. He even smiled benevolently.

"There's a definition here of a falling body, sir. You didn't give me a chance—"

"Hah! What's that?"

It says:

"A falling body is defined as the lesser in mass of two bodies when two freely moving bodies in space collide or impinge on. each other in any maimer or form."

"I took the trouble to look up the respective masses, sir. Planetoid No. 891, the one that... ahem... used to belong to us, has a gross of seven hundred ninety-two thousand three hundred and eighty-one tons. Planetoid 640, sir, has a gross of twelve million five hundred eighty-eight thousand four hundred and thirty-seven tons."

Sally said: "This Kerry Dale seems to have you there, dad."

"Why... why," he gasped, "it's outrageous; I won't have it. Six million dollars of my hard-earned money going to that snipperwhopper! Can't you do something, Horn?"

"I'm afraid not. The law is clear. I'd suggest a settlement."

"Settlement be darned!" he stormed. "I'll—"

"You'd better, dad," Salty advised. "After all, six million—"

He groaned, sputtered and gave in. He composed a spacegram that he thought was a crafty masterpiece:

DALE.

PLANETS. VESTA.

YOU'RE A SPACE ROBBER AND A SCOUNDREL. WILL START SUIT AT ONCE AND WIN. TO AVOID SUIT I'LL PERMIT YOU TO SETTLE. OFFER YOU FIFTY THOUSAND CASH IN RETURN FOR GENERAL RELEASE. WILL PAY EXPENSES OF REMOVING MY PROPERTY. ANSWER AT ONCE OR SUIT GOES ON FILE.

KENTON.

In due time came the answer:

O.K. GIVE ME HUNDRED THOUSAND AND WE BOTH SIGN RELEASES.

DALE.

"Ha!" chuckled Simeon. "I thought that would scare the pants off him. For a measly hundred thousand he gives up clear title to six millions. Quick, Horn, draw the releases and shoot them on to Vesta with a draft for the money before the young fool recovers from his fright," The releases passed, were signed; the draft honored.

Simeon told his daughter happily: "There, you see, my dear, no one can get the best of your father. That young—"

A most agitated expert burst into the office; in his excitement forgetting even to announce his coming. He was Bellamy, chief expert of the Kenton Scientific Staff.

"A... a most terrible mistake has been made," he stammered, "a-about th-that asteroid."

"Ah!" murmured Sally to herself. "Maybe Kerry Dale wasn't so foolish as darling dad thought."

"What about it?" snapped Kenton impatiently.

"We miscalculated the orbits. We were so... ah... rushed, we didn't have time to send to Vesta for a copy of the Mammoth chart. I... I thought of it only yesterday. With the new factors on hand, I recalculated the elements."

A terrible suspicion grew on Simeon.

"They... they wouldn't have met," Bellamy went on unhappily. "They would have cleared by "three miles if the Flying Meteor hadn't pushed them together."

Sally ran to her father. For once she was seriously alarmed. He seemed to be having a. stroke. His face purpled and his breath wheezed. "I'll sue him," he gasped, "hi! get my money back. Ill bankrupt him for fraud, conspiracy; for—"

"Wait a minute, dad," said Sally. "You can't."

"Why can't I?"

"You gave him a general release."

For a long moment old Simeon glared at her. Then he fell weakly into a chair and a certain awed admiration came into his eyes. "The dingdasted young good-for-nothing! No wonder he sold out so fast and so cheap. He outsmarted me... me, Simeon Kenton." He rose. "Daughter," he said impressively, "mark my word, that young man will go far!"

But Sally wasn't there any more. She had slipped quietly out. She wanted to send a private spacegram of her own. It would read:

KERRY DALE

PLANETS, VESTA.

CONGRATULATIONS! KEEP UP THE GOOD WORK!

SALLY KENTON.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.