RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, July 1936, with "Pacifica"

NOT one in a thousand of earth's teeming millions had ever heard of the island of Kam prior to the year 1985. It was merely another of those inconspicuous speck's of thrust-up volcanic slag and lava that dot the wide stretches of the Pacific, to the despair of cartographers and the delight of ships weary of sailing the interminable blues and grays.

The volcano had long since ceased its smoky activity, and the weathering of uncounted centuries had softened its hard, truncated outlines, worn down its scoriaceous lava and basalt rock to crumbling, fertile soil. The vagrant, spore-laden airs and tropic, precipitant moisture had done the rest.

Yet, in the year 1985 the hitherto unknown Kam leaped violently into the focus of the world's attention, and held the very pith and center of the newscasters' animated headlines for a long quarter of a century—held them with such increasing fervor and intensity that by the end of the crucial period everything else was relegated to the limbo of casual comment and hasty summaries forgotten almost before the last words had droned from the televisors.

There had been a flare of revolution in China. The subject race, groaning within the iron barriers which the Eastern Empire had raised against their starving billion of people, had risen from the abysses of despair and been crushed back again in a hideous welter of blood and ruin.

A new dictator had appeared in Europe to contest for a division of power with the overlord and had won a compromise.

A strange projectile had been discovered buried deep within the soil of the Mojave Desert, which, when opened, had been found to contain documents of strange, unearthly material and inscribed in a tongue not known to humankind. It was obviously an attempt at communication from another world. Every day the scientific laboratories of the several nations, working at feverish speed, announced new and important discoveries in science, most of them, unfortunately, in the way of more powerful and more destructive instruments of war.

But these events, which, prior to 1985, would have engrossed the whole attention of the human race, were now dismissed with impatient shrugs, while the listeners at the newscasts settled down to further and interminable discussions of the mighty drama that was taking place on Kam.

By the end of the year 2110 the emotions of the world were aroused to an almost unbearable pitch. The climax of a quarter century of incessant toil, of the straining resources of the five great political segments of mankind, was in sight.

The date had even been set for the ultimate, the supreme trial. On the success or failure of that event depended the fate of countless millions of earth's overflow, on it depended whether or not instant and bloody wars, more horrible than any in all earth's history, would be unleashed in the last desperate struggle for expansion, for a place in the sun.

A place in the sun! Dreadful phrase, that far back in 1914 had led to unutterable anguish—a mere metaphor then—but now a grimly real thing, with definite meaning and content.

For the blessings of advancing science had turned into a curse and a nightmare. Not because of anything inherently wrong in the vast structure that man's noblest thought had raised as a shining tower to the stars, but because man's inner nature—in the mass, that is—had not kept even progress with his intellect.

DISEASE had been definitely conquered. The non-filterable viruses had been discovered to be the simplest form of life—single organic molecules—and their properties thoroughly explored. A unit serum, injected into babes at birth, gave effective immunity against germ and disease for life.

The span of mortal years had been considerably lengthened by a new method of cleansing the human blood stream of cumulative waste, thus retarding the calcifying and other hardening processes.

Cancer, a thing of normal cellular growth running wild, had been controlled by inhibitory solutions of the organic salts of osmium and iridium.

Heart surgery had developed to a stage where transplanted tissues could be grafted on to leaky valves without that delicate organ missing a single beat.

Man refused to die, yet he did not cease to propagate. The dictators saw to that, and in sheer self-defense, the solitary democratic unit of the Americas and Great Britain was perforce compelled to follow suit. For each of the dictators, animated alike by ineradicable lust for power and greed for aggrandizement, urged upon their supine subjects the need for bigger and ever bigger families: boys to man the rocket fleets, the underwater cruisers, the swift battleships; girls to keep the munition plants at full blast, to till the soil, to breed more fodder for the insatiable machines in endless, repetitious cycles.

The result should have been obvious even to the purblind. The human race increased by leaps and bounds; it swarmed to bursting over the hitherto unoccupied territories of the planet; it planted colonies on the desert wastes, on the inhospitable ice of arctic islands and the vast, subzero reaches of the Antarctic.

Soon even that did not help. Tens of millions teemed where only millions had lived before; the continents were continuous stretches of hundred-storied cities; agricultural lands were more precious than radium mines.

Science battled valiantly to feed and adequately care for the swarming ant heap of humanity, but it was a steadily losing fight. There was only one thing left: war! War with frightful engines of destruction; was to rid the earth of its excess millions; war to conquer and eradicate so that one's own people might find room to expand in the new-made wastes.

The dictators set to work. Carefully engineered incidents occurred. It required but a spark to set the entire world ablaze. The Americas protested in vain, offered to lead a great movement for restriction of births. The dictators would not listen. Their folly had outrun them. Besides, they rightly suspected each other, fearing secret accouchements, the rearing of potential soldiers in sub-rosa establishments, and the consequent dislocation of delicate balances of power. War loomed ominously near.

THEN it was that Adam Breder came forward with his astounding plan. The nations gasped, listened with diminishing skepticism, and halted temporarily their vast mobilizations. Had it been any one else who evolved such a fantastic scheme, he would have been pronounced mad and forthwith shut up in an asylum. But Adam Breder could not be treated in such a manner. His fame as an engineer transcended the bounds of nationalist hatreds.

It was he who had driven a tunnel under the twenty-mile-wide waters of the English Channel to connect England and France. It was he who had made a fertile, well-watered land of the burning sands of the Sahara, by an ingenious system of huge underground caves into which the diffuse subsurface waters could filter and collect, and be ultimately raised to irrigation ditches by mighty pumps.

It was he who had performed the incredible feat of building a dike that extended out into the Atlantic from the farthermost spit of Newfoundland, and which diverted a portion of the Gulf Stream as it flowed past on its eastern journey toward Europe, back against the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, thus making those bleak lands mildly tropic and capable of supporting extensive populations.

In fact, had it not been for his genius, the inevitable day of suffocating overpopulation would have been reached a decade earlier, and the world have been in ruins by 1985. Now he came forward again, with this final measure to stave off starvation and death from an overpopulated world. It was so breath-staggering in its vastness of conception and daring of theory that even Adam Breder's reputation was barely sufficient to gain it a hearing.

It was nothing more or less than to raise an entirely new, virgin continent out of the slime and ooze in which it had lain enshrouded for uncounted millions of years!

"Look!" He had stabbed with his long, musicianly finger at the huge map spread over the wall. "Once upon a time all this area was a vast, fertile continent. Now it is a waste of waters dotted by islands that are only the peaks of mountains too high to be entirely submerged."

He swung around to the representatives of the great powers of the world. His voice grew strong with the enthusiasm of the seer, of the genius who is a single-track enthusiast.

"A waste, gentlemen! A sheer, inexcusable waste! Down there, less than two miles beneath the shrouding Pacific, lies a continent, a million square miles of land! Restore that to the surface, and all your problems are solved. Room for your excess populations, unimaginably fertile soil, manured with millions of years of dripping organic ooze, lush, tropical climes! Good Lord, gentlemen, I don't see how you can hesitate an instant."

WALLACE, the British-American representative, smiled wanly. That was just like Breder, of course—a great engineer, yes, but a child in all other matters, in spite of his seventy-odd years.

He looked around at the others, noted their sidelong, suspicious glances as they weighed and probed each other from under veiled lids. He knew exactly what was passing in their minds, the lightning calculations that were being made, the half-skeptical, half-greedy plans that were forming in their subtle brains. Wallace sighed. Almost he wished that Breder was, in truth, a madman, a futile visionary.

Breder was staring anxiously, almost pleadingly, around the circle of the great, seeking in vain for approbation of this latest and most-daring vision of his. Wallace broke the tense silence with which the others masked their thoughts. "It sounds good, Breder," he said, "but a bit incredible. Raising a submerged continent out of the Pacific, two miles up. You've done great things before, I know, but this—well, just how would you do it?"

Breder flared, subsided quickly. He was like that, so engrossed in his schemes and calculations that it seemed impossible for them not to be as simple and luminous in their plain truth to others as well as to himself. He was always forgetting the unaccountable stupidity of laymen, whether they were poets or ditch diggers or statesmen.

He looked again at these closemouthed gentlemen who, in the persons of their immediate superiors, ruled the world. There was manifest contempt in his gaze for their profound ignorance of science. Good Lord, he must explain, talk baby talk so that they might understand! The rightness and swift shorthand of mathematical equations were not for them.

"The theory," he said slowly, "is very simple. The practice, I grant you, might prove difficult, but," and he lifted his ascetic, finely chiseled head with unconscious arrogance, "you don't have to worry about that. I can overcome all physical difficulties." And such was the magic of Breder's reputation that no one of the watchful representatives murmured dissent, even in his thoughts.

"You may or may not know," the engineer went on, "that the solid surface on which we live and have our being is not an accurate sample of the entire earth. It is, in fact, only a crust, and a mighty thin one at that. Through various methods, notably by observation of earthquake tremors, it has long been known that this solid crust is only some sixty miles in thickness."

N'Gob, the African, shivered. He had not gone in much for science. "And what's underneath? Fire?"

Breder smiled. "No. That's a theory which has been discarded ages ago. In fact, after a certain depth of basalt and other materials, the central core of the earth is composed almost exclusively of the heaviest metals, chiefly iron and nickel. But this is the point. They are under tremendous pressures, and naturally, the deeper we go, the greater the pressure from the overlaying masses. At 100 miles down it is 600,000 pounds per square inch; at 800 miles it rises to 7,500,000 pounds, and at the center of the earth it reaches the incredible figure of 45,000,000 pounds to the square inch. These are pressures that we never have been able to duplicate in the laboratories—pressures that even at 60 miles down, make of rock and metal something new, something unknown on the surface." The Eastern Empire diplomat looked bored. He was not interested in this. What was vital to him was another matter. Should Breder prove to be right, who would control this vast new territory that would rise dripping from the ocean's bed, almost at the very doorstep of his master? But he murmured now only a polite: "And what is that?"

"A plastic material," the engineer answered quickly. "A single homogeneous unit so compressed that it no longer possesses the properties of solids as we know them. In fact, for all intents and purposes, the core of the earth partakes of the nature of a liquid—a liquid, it is true, tremendously heavier than water—yet essentially the same in its obedience to the laws that govern fluids."

Wallace nodded. Of course, he had known that. So had the other delegates, with the exception of N'Gob. There was nothing new or startling about this thesis. The principle of isostasy, that is, the condition of equal balance of rock weights all over the earth, showed that the earth's crust was a solid floating on a plastic core. But what was Breder driving at?

THE ENGINEER saw his gesture, smiled. "I'm coming to the meat of the matter," he said. "What I've told you is elementary, so is the next principle I am going to enunciate. But no one before has ever put the two together and envisaged their possibilities."

The South European delegate stirred impatiently. The dictator was waiting at the televisor for complete details of this interview, and time was passing. It was not good to keep the dictator waiting. "What is your second principle?" he demanded.

"Pascal's law."

They looked blank at that, even Wallace. Somewhere in the back of his head stirred faint memories of schoolboy days. He had heard the name before, knew it related to physics, but for the life of him he could not specify now what it was.

Breder shook his head scornfully. He never could understand that these men were diplomats, not scientists, that things once learned could ever be forgotten.

"Pascal's law," he explained, "is the fundamental law of hydraulics. It states simply that pressure applied anywhere to a body of confined liquid is transmitted undiminished to every portion of the surface of the containing vessel. Do you see the connection now?"

"Hanged if we do," N'Gob said bluntly. He was more direct in his acknowledgment of ignorance than the others.

Breder groaned inwardly, set himself to put things in the easiest possible terms. "I'll try to restate it in practical terms. If you apply a force of one pound to one square foot of the surface of a liquid contained in a vessel whose total surface area is 1,000 square feet, that one-pound force will be transmitted by the liquid so as to act with a force of one pound on each square foot of the container. In other words, the total force exerted by the original pound will be 1,000 pounds. It's the motivating principle of the hydraulic press. Now do you see?"

Wallace groped vaguely. "I—I'm afraid I don't," he murmured apologetically.

"The entire earth is such a container," the engineer went on. "Its central core is fluid, plastic; the outer solid crust is the containing surface. Suppose I apply a concentrated force to a limited area of the inner core, even to a square yard. That force will surge through the unimaginable density of the central earth, will beat with undiminished power against every square yard of the earth's surface.

"Pascal himself saw this dimly when he exclaimed that a vesselful of water is a new machine for the multiplication of force to any required extent, since one man will by this means be able to move any given weight. Yes, gentlemen, with the proper concentration of force at the proper point, I can lift even a million of square miles of ocean bed upward for a distance of two miles to create a new continent."

They leaned forward eagerly, puzzled. These men were trained in the tortuosities of diplomacy, not in the luminous simplicities of science.

"But where is the proper point?" demanded the North European.

Breder grinned. "Sixty miles beneath the surface of the earth, on the island of Kam," he answered promptly.

"Sixty miles down," gasped N'Gob. "How will you ever get there?"

"By boring a hole."

NOW he had his sensation. Every one spoke at once, even the inscrutable representative of the Eastern Empire. It was impossible, absurd, even for a man like Breder. Sixty miles, when the furthest depth yet reached was a paltry seven miles. The increasing heat, the pressure—there were a million and one obstacles.

Besides, what would hold the continent up? The principle of isostasy, of equal balance—this was Wallace's contribution to the turmoil. And how limit the force? If Pascal's law were true, if the core were really plastic, wouldn't the entire earth's crust lift bodily, with unimaginable consequences?

Breder cut sharply across the babble of voices. "Gentlemen," he said with quiet arrogance, "I did not come to you with a half-baked idea. I have considered it for a year, tested every angle. Let it be sufficient when I say that I have invented the necessary apparatus to bore through solid rock and basalt for that distance and more; that I can take care of any conditions of heat and pressure that may arise.

"As for Wallace's more scientific objections, I have made a careful survey of the area of the sunken continent. The reason it sank, eons ago, the reason it is now a highly volcanic temblor region, is because at present it violates the very principle of isostasy he mentions. Underneath, my instruments disclose a huge vault, filled with an upthrust from the central core of the tremendously heavy and compressed nickel-iron fluid.

"To compensate for its weight the continent sank and the lighter ocean waters rushed over it in a vain attempt to create a balance. It was not successful. The entire region is very unstable; the volcanic eruptions and numerous earthquakes testify to the attempt of nature to create once more a condition of stability, of isostatic balance.

"By raising the continent once more, by pressing the heavy core fluid out of the fault, the balance will be restored. This fault, to all intents and purposes, is itself a closed container, cut off by basalt formations from the much deeper inner core. That is why only the submerged continent will rise, and not the whole earth."

IT took months before the mutually jealous nations of earth finally agreed upon the scheme; months of scientific fact finding, bickerings, and jockeying for advantageous positions. This last was the most important.

The Eastern Empire had clamored for complete control of the hypothetical continent of Pacifica. It was, they argued, strategically at the threshold of its domain; most of the islands that would be obliterated and fused in the new land belonged to them. Kam, however, the scene of the proposed operations, was a British-American possession. And, they went on with bold effrontery, it was necessary to their national needs. Their populations, dominant and subject alike, were more procreative, than all the others combined.

It was this exactly that the rest of the world feared. Negotiations were abruptly broken off. The war clouds gathered again. Mobilizations recommenced. Then, suddenly, unexpectedly, the Eastern Empire yielded. It agreed to all demands; the partition of the area, when and if raised, equally among the five great powers; the demilitarization of the new continent, and mutual guarantees as to its inviolability; a birth-control system, universally applied, so that with this increased area for colonization, the future would be insured against further population pressure.

Wallace shook his head in the secrecy of his conference with the president of the British-American Union. "I can't understand it, sir," he admitted. "The emperor of the East has given in too suddenly and too completely. It isn't like him at all. I'm afraid he has something in reserve, something that may spell trouble."

The president was old and war-worn. "Chu-san is a young man. He expects to live a long time," he murmured cryptically. "But at least we have a breathing space. For the twenty-five years that Breder has calculated it will take to finish the job there will be no war. For that much we may be thankful. After that——" He shrugged his shoulders and turned away. He would be dead by then, thank Heaven, and younger and more vigorous men would arise to deal with the future.

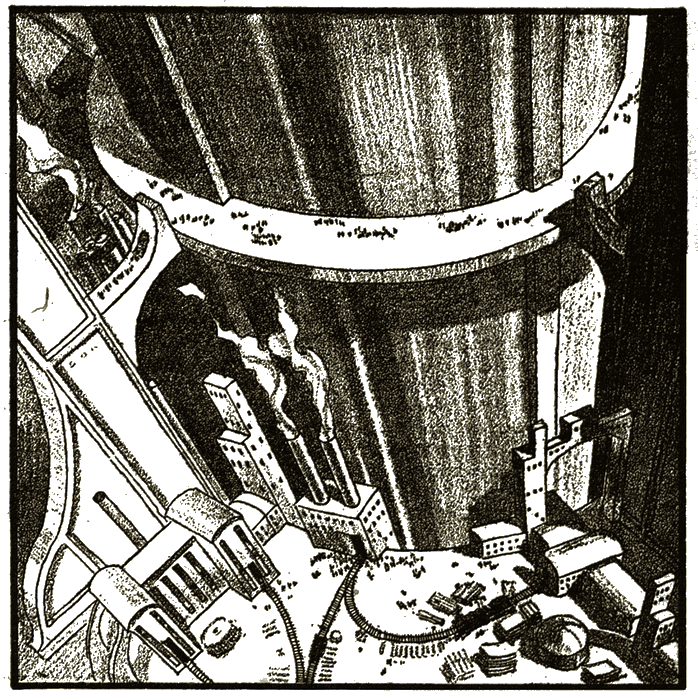

Adam Breder started work, happily content. The squabbles, the political implications of his colossal task, disturbed him not at all. It was purely and solely an engineering problem with man's brains pitted against the senseless resistance of nature. Five hundred millions were voted him, ten thousand men put to work. The island of Kam became the busiest spot in the Pacific. Cargo planes, great submersible freighters, shuttled to and fro like swarms of speeding insects.

The engineer had chosen his spot well. The old volcano was silent, but its shafts still pierced deep into the bowels of the earth. It made things a bit easier. Day and night, restlessly, remorselessly, the work went on. Deeper, ever deeper, bored the great carbostele drills of Breder's special invention. They went through granite, basalt and the toughest metals like so much butter.

Deeper, ever deeper into the earth it bored, through

rock and granite that had never seen the light of day.

Down, always down, day and night, weeks and months and years. The former seven-mile record was soon surpassed. They were boring now through the great underlying granitic structure of old earth, through rock that had never seen the light of day since time began.

THE spearhead of the working force crouched behind the great drills for not over two hours at a time, then they were hauled in fast elevators to the surface for long rests. Behind them came the mopping-up crews, widening the tremendous shaft to the required dimensions, facing cracks and weak spots with cement of a special formula that hardened quickly to the toughness of the surrounding granite, installing communications, elevators, removing the tunneled rock for dumping in great scows far out on the Pacific.

The worst problems that Breder encountered were those of adequate air supply, and the steadily mounting heat and pressure. But these had been solved by him theoretically long before the first drill bit into the volcanic shaft, and worked just as effectually in practice.

Air was pumped down under pressure through a subsidiary tunnel, and expanded at the bottom before being released. This not only provided a constant supply of clean, sweet air, but solved the other difficulties as well.

The swift expansion of the gas produced subzero temperatures—a principle thoroughly understood back in the nineteenth century—and the immensely cold currents of air were conducted along the walls of the shaft so as to cool the pressure-hot surfaces and at the same time reabsorb sufficient heat so as to render it breathable to the workers. The waste products of respiration and excess air were then forced to the surface by a series of pressure pumps and exhaust fans so that there was always constant circulation, sea-level atmospheric pressure and normal temperatures. It was a triumph of delicate balance.

Not that there weren't other problems, gigantic, heartbreaking. But Breder took them all in his stride. Unfortunately they grew worse as the years of ceaseless toil went on, and greater and greater depths were reached.

Breder was getting old. It was not alone his age, but he had refused to spare himself. The man seemed never to sleep; at all hours of the eternal day that reigned artificially at the bottom of the thrusting shaft he was on the job, exhorting, directing, calculating in his mobile office, meeting Cyclopean emergencies with swift decisions.

There was, for instance, the terrible time when a vast pocket of lava, cut off unimaginable ages before from the quiescent volcano, erupted suddenly along the probing drill, and rose with hideous speed up the tunnel vent. But Breder was prepared. Huge locks of fire-resistant material, with interlocking gates, kept even pace behind the whirling drills, two hundred yards above.

At the first clamor of the warning alarms, the great gates slid impenetrably shut, and the seething lava beat in vain against the asbestopor material. But two hundred men had been caught and crisped to ashes, and a million dollars' worth of material had to be replaced.

Breder shook his gaunt head indomitably and drove on. It happened not once, but several times. There were mutters of revolt from the scared workmen as they went down and down, ever closer to the central core. But the engineer was ruthless and the special international police backed him up. What were a thousand lives to the completion of his task, to the future welfare of millions of people?

The engineering problem involved concerned him far more. Some of the lava pockets were limited in area, and could be skirted by cautious exploratory shafts. But others seemed indefinite in extent, vast lakes underlying the rocky structure. Here he employed a new technique.

He literally froze a cylindrical core of the magma by injecting inexhaustible jets of glacial air into the bubbling mass. It was tedious, terribly slow. An inch at a time, a foot a day, but steadily the solid core expanded to safe proportions, and within it the devouring drills went on and on until solid granite was once more reached. One molten pocket took over a year to penetrate.

AT the twentieth year of the Gargantuan task, Breder suddenly collapsed. He was well over ninety now and the terrific driving strain of those two decades had finally worn down even his superhuman energy. He was a shrunken old man, a mere palsied ghost of his former self. The doctors examined him, and pronounced him in no immediate danger, but they ordered him peremptorily off active duty.

A great wail arose from the nations of the world. The shaft had reached the incredible depth of almost fifty miles. There was still over ten miles to bore, but the difficulties were piling up in geometric progression with each foot of progress. Granite had yielded to basalt, the pockets of lava were becoming increasingly numerous, the gravitational increase of weight was becoming more pronounced, the problems of ever-lengthening communications with the surface, the ever-increasing temperatures, air supply—everything was rapidly approaching a climax.

There was also still ahead the supreme task of all. Breder himself had admitted that the driving of the shaft was child's play to what would necessarily follow when the inner plastic core was reached. While it was true that his delicate torsion balances and the results of electrical echoes had disclosed a tremendous thrust of nickel-iron from the very bowels of the earth along the entire bed of the Pacific, that was to be the new continent and had once been an ancient land, still there was room for error.

Furthermore, even if everything went according to schedule, the proper point of application of pressure, the installation of the superpowerful engines required, the almost superhuman mathematics necessary to calculate the infinite factors involved so that catastrophe might not ensue, pointed inexorably to the guiding hand of a man of almost god-like proportions. And the world knew of only one such—Adam Breder!

But the old engineer knew better. He had been quietly grooming a successor right along for just such an emergency. During the long twenty years his corps of assistants had grown, expanded and shifted from time to time as young engineers joined up eagerly, finding this tremendous enterprise the one bright ideal in a world of otherwise tawdry nationalist hatreds and iron dictatorships and pitiful human suffering.

His staff, at the moment of his breakdown, was quite cosmopolitan. There were engineers and technicians from almost every country in the world. But the inner circle of his trusted assistants numbered four, Nijo, the Easterner, was the senior in points of years and length of service. He had been at Kam from the inception of the project, a short, squat, middle-aged man, with veiled, slumberous eyes and the inscrutable expression of all his race. But his brain was razor-sharp and his energies adequate to any task imposed.

Nevertheless Breder had never liked him. There was something secretive, coldly contained, about the man that made the engineer uncomfortable, and no one else before or since had been able to do quite that.

There was also Gregori, a North European, tall, fair-haired, placid to the point of sheer bovinity. Yet there was no one in the world, not even Breder, who could equal him in the handling of intricate mathematical equations.

OVER Kai-long there had been a prolonged struggle. He was Chinese in origin, a round-faced, yellow-skinned representative of a subject race, whose coal-black eyes flamed always with ineradicable anger.

On his head the Eastern Emperor had laid a price; he had fled his native land after an abortive revolution and sought sanctuary with Breder. The old Scotchman had granted it to him promptly; more, he had placed him on his staff at once. Kai-long had a reputation as an engineer.

Complications arose immediately. Chu-san demanded his delivery as a rebellious subject. Breder stubbornly refused. An attempt by Eastern members of the police unit on the island to seize him forcibly was met-with armed resistance by the others of the international force. Great Eastern bombing planes blasted their rockets out over the Pacific. The chancellories of the other nations went into alarmed huddles.

But Breder cut the Gordian knot. Dramatically he announced that if Kai-long were seized or harmed in any way, he, Breder, would personally detonate the entire tunnel and bring to naught the toil of years and the expenditure of uncounted millions of dollars. Whereupon Chu-san incontinently backed down.

For the pressure of his hordes was bursting the boundaries of his empire. Unless the promised Pacifica were soon lifted to the domain of reality, they must of necessity spill over into regions already crowded beyond endurance. And that meant immediate war, for which he was not yet properly prepared. So he nursed his rage in the privacy of his Himalayan fastness, and bided his time. Regularly he received reports on a directional-beam code from the island of Kam that tightened his lips, and brought his brooding plans closer to eventual fulfillment.

Kenneth Craig was the fourth of the inner circle of Breder's staff. He was the youngest of them all, barely twenty-one, when he joined up. And he at once proved to be the most popular, even among diverse nationals, to whom an American had always been something of a term of contempt for weaklings, who still believed in the will of the people and other empty, mouth-filling phrases.

Kai-long, older than he, and miles apart in temperament and racial outlook, became his closest, most-devoted friend.

Gregori smiled his slow smile whenever he passed. The workmen adored him. Only Nijo held aloof, as he did from every one else, going his solitary way, doing his work with high competence, yet spending all his spare time in the privacy of his own quarters.

Old Breder was a gruff taskmaster to this eager young engineer with the infectious grin and candid eyes. But, underneath, human affection for the first time invaded his grizzled frame. He sensed at once that here was a youngster with a mind as keen as his own, a grasp of engineering principles that was little short of astounding, and tremendous capacities for leadership. He set to work at once to groom him for the inevitable day.

THE DAY had come. Adam Breder announced that Kenneth Craig, now twenty-seven years old, was his successor, the man to complete the job that had slipped out of his aged hands. The North-European dictator fumed. It should have been Gregori, he declared. The South European did not care one way or the other. No man of his was in line, anyway. But Chu-san almost had a stroke. Nijo had been the logical new chief, and all the plans of the Eastern Empire had been carefully based upon that consideration. Now they would have to be changed.

He vented his almost insane wrath by ordering the execution of twenty thousand Chinese chosen at random. The bloodletting, the cries of the tortured, soothed his anguished spirits. Then he set to work again, scheming, redrafting his disarranged plans.

A certain secret code message from Nijo even brought an unpleasant smile to his lips. Perhaps, after all, there might be definite advantages in the unforeseen appointment. The white glare of publicity would not beat upon Nijo or upon the Easterners at Kam.

As for Kai-long, his emotions were divided between unselfish joy for the elevation of his young friend and blazing anger at the unprovoked and hideous slaughter of his beloved people.

"Some day, honored Ken," he told his new chief with clenched, pudgy fists, "I shall revenge my ancient people for all the wrongs they have suffered."

Ken Craig clapped his shoulder with kindly intent. "I know it's damnably hard," he acknowledged, "but there's nothing you can do at present. We have a job ahead of us to finish. After that——" He stopped short, but his meaning was clear. The completion of the interminable shaft, the raising of Pacifica, superseded everything else. They were engineers first, members of nationalist divisions of the human race second.

Kai-long nodded with somber sadness. "You are right, as always, honored Ken. I shall wait." He moved closer, looked around to see if any one were listening. They were alone in the surface office. "Watch that son of the devil as the vulture watches from the sky for signs of carrion."

"Meaning——?"

"Nijo!"

Craig laughed. "You're letting your racial antipathies run away with you," he warned. "Nijo's a great engineer. He's the senior here in point of service; there's never been a time when he hasn't done his job well and efficiently. In fact, I wonder why Breder passed him up to put me in charge."

"The venerable Breder did not trust that devil," the Chinese engineer retorted. "Old eyes sharpen as they wait for the sight of their ancestors. That is why he chose you——"

"O.K.!" Craig said hurriedly. He knew what was coming and had no appetite for flowery Oriental praises. "But don't step on his corns. I need him." Kai-long obeyed with religious fidelity, but he could not suppress the smoldering hatred in his glance whenever Nijo passed. If the Easterner noticed, he made no sign, nor did he seem to resent the fact that a mere youngster had been promoted over him. He performed his allotted tasks with the same quiet competence and efficiency as before. Perhaps, however, he spent more time in his room now, working his hidden light-beam transmitter, and drawing up careful notes.

Had there been any doubt in the minds of the world as to Kenneth Craig's ability to take over, they were soon dissipated. The work took on new energy, new driving force. Problems that seemed insurmountable were overcome almost as soon as they were presented.

Adam Breder stubbornly refused to be removed from the scene of his life work. A private sanatorium was built for him on the ocean shore, where he could rest his waning spirit with glimpses of blue sea and snuff the tropic breezes. Craig visited him respectfully at least once a day, sought his advice with loving care.

AT LAST, in 2009, the huge shaft passed the sixty-mile limit. The business of the world was practically at a standstill. The nations of the earth waited with bated breath for the expected news. Only in the remote mountain regions of Asia was there activity, and no prying alien eyes were permitted to witness it.

Then, one day, the great news broke. The inner core of nickel-iron had been reached. The drills had broken the earth's sheathing crust of granite and basalt, had penetrated the plastic, unimaginable materials of earth's center.

Had not Craig been prepared and prompt to act, disaster would have overwhelmed the long years of effort. For the liquid-flowing metals, under pressure of almost 400,000 pounds to the square inch, thus suddenly released from the weight of sixty miles of overlaying rock, swept the drill to oblivion, ripped up through the opening with overwhelming force.

But Craig was ready. For a week now the men had worked behind the capping plate, directing the course of the great drill through televisor screens. As the dark, furious metal seethed up, the hundred-yard thickness of carbostele capping, hardest of all alloys, faced with asbestopor, the perfect heat-resistant and insulator, clamped into place.

The shock of the onslaught was incredible. Millions of tons of heavy metal, fluid under the resistless pressure, leaped in frenzied fury against this puny obstacle to freedom. The thunder of the roaring waves was deafening, the carbostele cap quivered and groaned under the mighty impacts. The workmen crouched with blanched faces behind its flimsy protection. One grimy chap broke into screaming panic for the conveyor elevator that would whip him to the surface.

Craig caught him just in time, whirled him back into the ranks. One move like that and the contagion would spread into a bloody scramble for safety. He shouted bitter commands, but his words were smothered under the smashing thunder of sound. But the sight of him, grim, alert, by the conveyor, Kai-long and Gregori ranged alongside, guns glittering in their hands, spoke with far greater emphasis than any words.

White-faced, shaking, the men returned to their posts. Craig, now that the human crisis was over, hurried to his instruments where the titanic battle was recorded in electrical language. With grim, tight mouth and haggard eyes he watched. Would everything hold? Would the theoretic limits of safety include the actual? Matters that only the next few minutes could tell definitely.

If the answer was negative—— He grinned wryly to himself at that. For only a split second would the knowledge be his. There would ensue such an eruption as the world had never seen since the days when Dinosauria and Brontosauri roamed the steamy swamps. An eruption that would blow the island of Kam and all its works off the face of the earth, that would spurt fluid nickel-iron for miles into the air and rain destruction on hundreds of thousands of square miles of land and ocean.

The instruments jerked and danced with macaber movements. The needles strained to the limits of observation. Strains and stresses and forces registered that the human eye had never before observed in any laboratory. The din was almost unendurable. Then, slowly, as the puny mortals watched their handiwork, the needles began to drop back. Back, ever back, until they quivered to quiescent zeros.

THEN, and then only, did Craig think to take breath. Cheer after cheer, frenzied with release from the shadow of death, broke from the lips of the workmen. Kai-long shook hands in Occidental fashion, but with the solemnity and dignity of his own race. Gregori squeezed his hand in a bear grip that almost crushed his bones. They had won the first great battle, the first test of their work.

Craig said "Thanks!" simply in the sudden hush. Without another word he pressed the visor-screen control. Old Adam Breder's face flashed before him, startled. "What is it, son?" he wheezed. He was old now, terribly old.

"We've reached the core, sir," Craig reported quietly, "and the cap held. The credit is all yours, sir, from beginning to end."

The aged engineer tottered upright on the screen. A glory transfigured his withered features; his shoulders snapped back, youth seemed to flow back into his veins.

"It works," he cried out in strong, firm tones. "I knew it would work. The rest will work too. Pacifica!" he shouted, "the land of Adam Breder, the land——"

He caught at his throat suddenly, wavered, pitched forward on his face. He lay quite still, a seared and empty husk from which a once indomitable spirit had fled. His work was done.

For a week the island of Kam mourned their lost chief. The nations of the world converged to do him honor. There was a surfeit of glittering uniforms and long, tedious speeches, then the great engineer was buried on the shore of the island to which he had dedicated a quarter of a century, at the meeting place of sea and land. He had wished it so.

Work began again, as needs it must. Time was pressing. The specter of starvation stalked the swarming multitudes of humanity. Deficiency diseases took their toll for the first time in years. Only the successful emergence of Pacifica could solve the problem.

Craig threw himself heart and soul into the task. The course of the underlying fault was carefully mapped. It fulfilled expectations in every respect. A vast layer of nickel-iron had thrust itself upward into the very heart of the basalt region and had somehow been pocketed off from the deep, true core. It extended under the bed of the Pacific for a million square miles, roughly approximating the archipelago of scattered islands that stretched from Hawaii southeasterly to Papua and due east to the coast of Asia.

It was this area which held a considerable number of still active volcanoes and was subject to periodic earthquakes. This was understandable now. The nickel-iron substratum, closer here to the surface than anywhere else, had created a condition of great instability, of constant shifting of the crust in vain attempts to rebalance the load.

Craig drove a series of radiating tunnels from the main shaft to pierce the plastic core at different and widespread points. In each a cap of carbostele was firmly set. Powerful engines, originally designed by Breder and refined upon by Craig, were laboriously lowered from the surface and installed.

Centered within each carbostele plug was a plunger, extending down the longitudinal axis, its hundred-foot diameter at right angles to the pressure of the metal ocean within the orifice of the tunnel. The engines were connected with the plungers. They were, to all intents and purposes, mighty hydraulic presses of a size and compressive power not hitherto employed.

FINALLY, the great day arrived. The last bit of machinery had been installed, the last anxious test had been made. The world seethed with excitement. Delegations from every nation on earth arrived with pomp and ceremony. The island was divided into sections; each delegation kept to itself, eyed the others with mutual distrust. The international police force staked out neutral zones, exerted itself to avoid all possibility of a clash.

The sea was cleared of all ships, of all submersibles. Even rocket planes were forbidden the air over the designated reaches of the new continent. It was not known just what the ultimate effects of the experiment might be.

As for the islands that dotted the expanse, they were evacuated of all inhabitants, of all valuable possessions. Temporarily they were crowded into continental quarters already overcrowded. The coasts of America, of Asia and of Australia awaited the denouement with increasing anxiety.

Craig had calculated the displacement of waters by the uplift of Pacifica to be approximately 500,000 cubic miles. This vast amount would ordinarily lift the general level of earth's intercommunicating oceans more than 18 feet. But this, while leaving most of the coast lines unaffected, would play havoc with such low-lying regions as the Chinese water front, the tidewater regions of Eastern America, the mouths of the Nile and the Amazon.

But Craig was quite confident that there would not lie any such rise. For inevitably, in such a vast upheaval, fissures would necessarily appear within the newborn continent, and the excess waters, or sufficient of them to reduce the total displacement to manageable proportions, would cascade into the bowels of the earth to fill the hollows caused by the rising crust. Perforce they must, to achieve proper isostatic equilibrium, for doubtless the pocket of nickel-iron, pressing with renewed force against-the confining underlying layer of basalt, would pierce through to seek the inner core from which it had so long been divorced.

Nevertheless, he was grim and taut on that last day. He hardly heard the speeches; the formal ceremonials of the occasion passed over unheeded. There were so many factors involved, so many things that might miscarry. The failure of any one of them, the slightest misstep, and irremediable disaster would pour forth upon a stricken world, instead of the blessings that were so confidently expected.

Kai-long saw the fine lines of worry that lined his chief's face and squeezed his hand affectionately. "Do not fear, honored Ken," he murmured. "Everything is on the knees of our potent ancestors. They will not permit us to fail. The revered Adam Breder is at one with them, controlling the fates in our behalf. Why should our humble selves then doubt the result?"

Craig grinned in spite of himself. Kai-long was a man of science, an engineer among the best, yet in times of crises he reverted to the ways and traditions of his race, seeing no incongruity therein. The greater the crisis the more sincerely and completely he reverted. This then to him must be an extra-special crisis.

"You're right at that," Ken admitted. "We've done all that mortal man can do. The rest is up to our ancestors or fate, or whatever you want to call it."

He glanced at his time signal. "We'd better hurry. It's hardly an hour to noon. It'll take us that long to get down below and make the last-minute adjustments."

AT the bottom of the tremendous shaft everything was tense, electric. The zero hour was at hand. Soon, too soon, they would know whether or not a quarter of a century of unprecedented effort was wasted and fruitless. Mingled with these sentiments, intertwined with a clouded vision of the social and political implications to the world in general of success or failure, were more immediate anxieties.

No one of the little band of engineers clustered at the switches that controlled the radiating battery of gigantic plungers had any illusions about the precariousness of their position. The forces they were about to unleash, if successful, were of an order more terrible and awe-inspiring than any yet procured by man, or, for that matter, by nature itself in the uncounted eons since the earth had achieved a habitable crust. Forces that partook of a cosmic sweep and convulsiveness.

What might be the result? No one of them could safely predict the answer, not even Kenneth Craig himself. Only Adam Breder had possessed the calm confidence of the wholly impersonal engineer, and he was dead. Earthquakes might rack the world, volcanoes might burst forth through the ocean's heaving bosom with uncontrollable fury. More closely home, the sixty-mile tunnel might prove woefully insufficient under the unimaginable strains.

Everything that human ingenuity, that human genius could do, had been done to buttress its smooth walls, to line it with heat and pressure-resistant materials, but——

The little group looked soberly at one another as the final moment approached.

If anything went wrong, they were trapped, hopelessly, irrevocably, under sixty miles of whelming rock and fluid metal. Yet no one stirred, nor was any panic visible on their countenances.

There were four of them only: Ken Craig; Kai-long; Gregori with his slow, amiable smile; and Nijo, silent and inscrutable as ever. The Easterner, whatever else might be said about him, was not lacking in courage.

Craig checked his time signal, relayed final instructions to the surface, said in matter-of-fact tones: "Very well, gentlemen."

Simultaneously the complicated battery of engines started to turn, great flywheels to spin, electromagnetic fields to push and pull with mighty forces. Simultaneously the great plungers, one hundred yards long and one hundred feet in diameter, strained through the capping carbostele like unleashed beasts of prey.

The banked instruments quivered and moved in sympathetic eagerness. The pressures of the groaning engines built up. One hundred thousand pounds to the square inch, two hundred, three hundred, three fifty! Yet the plungers, shivering from the terrific thrusts, did not move, did not slither even a fraction of an inch within their casings.

Gregori gripped a stanchion with powerful fingers. His placidity was giving way to excitement. "They're not budging," he said.

Craig answered shortly. "Of course not. How can they? There's over 400,000 pounds pressure to be overcome. We'll have to build up beyond that."

Emotion flickered anxiously over Kai-long's slant features. "Do you think the engines can do it, honored Ken?" he queried.

"Without doubt," Craig retorted with a confidence he did not quite feel. Nijo kept silent, as always, but nothing escaped his deep-set, half-veiled eyes.

Three sixty, seventy! The rate of increase was slowing down. The fields grew mightily, the metal rods spun and gyrated. The whole chamber quivered with powerful, opposed forces. Four hundred thousand, read the pressure dial! A sigh heaved from the waiting men. Another five thousand—ten!

FASCINATED, all eyes turned to the great plungers. They were moving in their machined sockets, slowly, it was true, an inch at a time, but inexorably.

Kai-long called on his ancestors, Gregori whooped, and even Nijo hissed with suddenly released breath. As for Craig, his heart seemed akin to the forcing pistons in the motors. The second step had been conquered!

The hydraulic plungers were moving with accelerated speed now, as the pressure behind them rose to greater and greater heights. Then, suddenly, they were home, ramming the immensely compressed plastic mass beyond with indescribable impact. Almost 360,000 cubic feet of fluid nickel-iron was being forced outward into the vast underlying pocket, already filled to the brim, was beating with simultaneous equal pressures of more than 600,000 pounds to every square inch of the vast totality. Pascal's law was in operation on a scale undreamed of even by its originator!

Craig was surprised to find himself trembling. The atmosphere of the underground chamber was tense, vibrant. Nothing seemed to have happened. The earth did not shake, nor did the smooth-lined walls groan with the titanic pressure. He moved quickly to the controls, reversed the motors. The plungers yielded sullenly as the pressure dropped, giving way unwillingly to the potent enemy they had just bested.

Once again, as the huge cylinders quivered to a position of rest in their casings, the engines took up the positive beat. Once more the plungers rammed home. A cycle had been established. Forward with irresistible thrust into the plastic nickel-iron, back to position, forward again, systole and diastole, beat and double beat, pounding on earth's interior core with repeated blows.

Yet still nothing happened. The seconds became minutes, the minutes grew. The little group of engineers looked at each other sidewise, afraid to meet their comrade's eyes in the dawning admission of failure. There was not even a tremor to show that earth's too-solid crust was moving under the stupendous lifts.

A tear rolled slowly down Gregori's face, unashamed, unnoticed. Nijo's enigmatic features for the first time showed startlement, alarm even. If Breder, if Craig, had been wrong, then all Chu-san's plans were at an end. But their young chief gritted his teeth, cried harshly: "It must—it must work, if only for Breder's sake."

The engines spun, the plungers moved—in and out, in and out, ten minutes, twenty minutes, half an hour. Yet the banked instruments, carrying the tale of earth's remote crust, did not by so much as the tiniest quiver show the end result.

"There must be an air vent somewhere within the pocket," groaned Gregori, "through which the pressure is released."

"There cannot be, esteemed sir," Kai-long retorted. "Our instruments showed none, nor could such a vent have existed without eruption long since."

Craig, who had stood like a statue, frozen to despair at this seeming failure of all their toil, cried out suddenly. "What a fool I've been! I've forgotten—we've all forgotten—that the waves of propagation of the inducing force through the plastic mass have a definite velocity—about six miles a second. It takes time therefore for the——"

THE televisor signal buzzed vehemently, insistently. At the same time the dial needles jerked over the face of the instruments. A man's face materialized on the shiny surface of the screen. His features were contorted with excitement, with alarm. It was Jenkins, assistant in charge on the surface of the island.

"Mr. Craig! Mr. Craig!"

"What's the matter?"

"Kam is rocking on its foundations. The ocean is boiling like a seething cauldron. All hell is popping loose. The men are scared; they say the world is coming to an end. We'll all be killed. Look!"

The man thrust his head back over his shoulder, wheeled with gaping mouth and final scream. Then he lunged backward and out of the range of the televisor.

Even as he ran, the sound of the tumult pierced the miles of solid rock, crashed with a rumbling, frightful sound in the confined walls of the underground chamber.

The earth shook and slanted dizzily. The walls heaved and convulsed with unleashed forces. The engines swayed in their moorings, snorted, and spun irregularly. The din of a tortured, upheaving world deafened their ears, smashed through their consciousnesses in a red haze of rending fury.

Craig staggered, caught at the solid stanchion of the televisor for support in a world where all things were in convulsion. His bleared eyes held dizzily to the still-functioning scene above. There was no sign of Jenkins, of any one else.

But within the narrow range of the screen the world was crashing. Great chasms yawned where equipment-covered slopes had been, the ground moved and writhed like a long, sinuous snake. The Pacific belied its name with unbelievable fury. There was no sky, no sea any more. All things were blotted out in a crashing chaos of gray, spume-crested mountains that flung up to the very heavens, dissolved with breathtaking velocity, and piled up again in hideous uproar.

Even as Craig watched in confused, bewildered paralysis, planes leaped like long silver dragon flies into the visor screen, red blasting rockets lashing out behind. They bucked and swirled in cyclonic air thrusts, steadied, and streaked across the screen and beyond with reckless acceleration.

It took the staggering American but a moment to realize what had happened. The workers of the island, the diplomatic observers of the nations, the staff he had left in the main power houses, had fled, had deserted him and his comrades, miles beneath the surface, to the elemental fury of the earth jinni they had rashly invoked. There was no one on the island of Kam to direct the thrusting machinery, to confine and control the mighty lift of a continent!

Ken's brain cleared magically. Disaster loomed momentarily, not only to themselves, but to a cowering earth. Even as he sprang forward the screen streaked violently, went blank. Somewhere along the line there had been a break.

Kai-long was at his side, screaming above the uproar. "Turn off the power, honored Ken, before it is too late. Turn off——"

But Craig shook his head in swift denial. His hand was already on the swaying conveyor. "We can't give up now," he shouted. "The process must go on. The motors are automatic; they don't need us. The surface does. Besides, if the power stops, we're doomed, trapped. Come on."

He swung into the elevator, gestured frantically to the others. Gregori and Kai-long crowded in beside him. But Nijo made no move. In this crisis, this elemental crash of earth and sea and rock, no fleeting emotion betrayed his inner thoughts.

"Hurry!" Craig cried again. "We have no time to lose."

But Nijo answered softly, and somehow his voice pierced the rending noise. "Some one must stay below, Kenneth Craig. As you have justly said, the process must go on. There is no returning from the path. But the engines may falter in their appointed task. A human hand must direct, a human mind must oversee. I am only an inconspicuous being. My life does not matter. I shall remain. You are needed on the surface."

"Nonsense," Craig shouted angrily. "If any one stays, it is my place."

Nijo stepped swiftly forward. His brown hand darted out, flicked at the button. The conveyor jerked upward before Craig could move to stop it. It seemed to him as he fell backward at the swift acceleration that there was a faint, self-satisfied grin on the Easterner's face. Then it blotted from view.

"He is a brave, devoted man," he said reproachfully to Kai-long as the conveyor shot swiftly upward, swaying and bumping with the vibrations of the inclosing walls.

But the Chinaman was unconvinced. "I do not know," he muttered to himself. "There is something strange——"

Beneath, Nijo smiled triumphantly. He glanced sharply at the instrument board, at the still-heaving plungers. Everything seemed in order. Then he proceeded to do certain things, methodically, purposefully, as if in accordance with a long-preconceived plan. When he was through, he carefully took out from the capacious pocket of his smock a tiny but powerful transmitter, wired it into the current supply. He spoke very low into the microphone, heedless of the thunder around him——

Far off, high on the Mid-Asian plateau, Chu-san heard and was satisfied. A dozen visor screens sprang into life before him. A dozen uniformed Easterners bowed abjectly from the silvery depths. Swift orders crackled. They bowed again and faded from view.

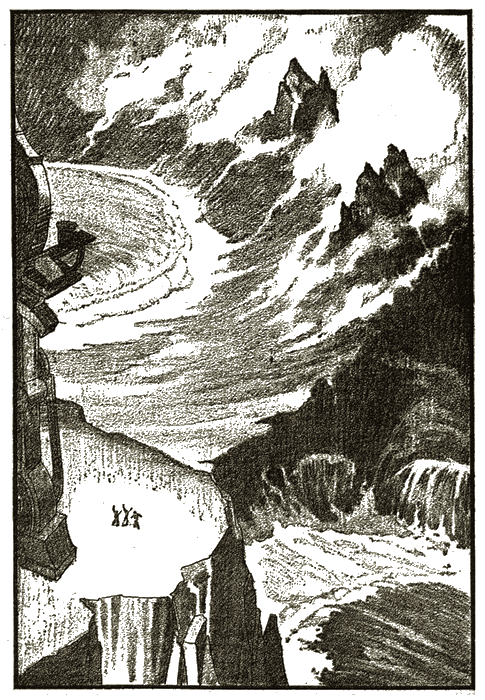

CRAIG and his two assistants flung out of the cage into a world of turmoil and confusion. Not a human being had remained on the island; every one had fled in terror from the gigantic cataclysm. It was, in truth, a sight to shake the stoutest heart.

Kam rocked underfoot like the deck of a ship in a hurricane. Earthquake tremors followed each other in quick succession. The top of the ancient volcano was gone, tumbled into the devouring sea.

Everybody had fled—the island rocked—

the volcano was gone. devoured by the sea—

Fortunately it had smashed down the untenanted side of the island, carrying along with it only some accessory storage houses. Huge fissures yawned in the revealed bedrock, extending downward unplumbable distances. A great gale howled overhead, whipping speech from their mouths, forcing them to edge their way along with thrusting shoulders.

The ocean tumbled and heaved like a giant in travail. Huge walls of gray-green water lashed mountain high upon the doomed island, tore away tons of slithering rock. Far out, so far it seemed a mirage, the great Pacific seemed to split and shudder away from the black, protruding back of a tremendous, prehistoric monster.

Craig saw, and seeing, knew the answer. "Pacifica!" he yelled to the howling elements. "The continent is being born!"

Then he was within the comparative shelter of the main power house, panting, slithering. Heedless of his companions, he went swiftly from machine to machine, from instrument to instrument. Luckily, they were anchored on bedrock far beneath, and the building itself was on a rise of ground where the ominous tides had not yet reached.

There were repairs to be made, adjustments of delicate parts jarred out of position by the racking tremors. They set to work at once, taping, securing, making connections more firm. The power was still intact, the panels showed that the plungers sixty miles below were functioning with unimpaired efficiency. Nijo, alone in the underground, had not let them down.

"Good man!" Craig muttered admiringly, and plugged in the televisor. He had found the break, had repaired it. He would order Nijo to the surface, peremptorily. There was no sense in his taking such frightful chances. But the screen remained blank, in spite of his splicing. With a curse he fought his way back to the tunnel shaft.

He would go down, bring him up by main force, if necessary. But the conveyor had unaccountably gone out of commission also. He could not know that Nijo had deliberately disconnected both, cannily foreseeing some such move on the American's part. It was essential that he remain below.

Kai-long shook his head privately to Gregori. "I do not like this, esteemed sir. I do not trust this Nijo; I do not trust any Easterner. They are all treacherous."

Gregori only stared. It was the Chinaman's bitterness against the oppressors of his race that spoke, of course. In his placid, easy-going way he hinted as much. Kai-long subsided, baffled. He did not dare say anything to Craig. Several times before he had been sharply reprimanded.

IT took almost a week for the Gargantuan task to be completed. Only three men saw it through from beginning to end; were privileged to witness the birth of a new continent, the upheaval of a land that had lain submerged and blind under whelming ocean for eons of time.

It was an awe-inspiring sight. For a week the sea boiled and heaved in the throes of a mighty parturition; for a week the island rocked and groaned, while fierce storms pelted their devoted heads. But slowly the primordial ooze came up from the depths, shouldering the waters away with dripping slime and the skeletal ribs of an ancient world.

As it rose, Kam lifted too, riding the monstrous plains of this new earth with mountainous crags. It was fortunate that it happened thus. Or else the retreating sea would have long overwhelmed them, or the stench of the steamy, miasmic plains have stifled them with odorous effluvia.

Then, one day, the shudderings ceased, the tumult of the outraged elements died. The sun poured out of a brassy sky once more, sucking greedily with its tropic radiance at the muck beneath. Great, steamy clouds rose endlessly upward, veiling the plains in perpetual shroud, billowing like a shoreless sea against the sloping sides of the two-thousand-foot mountain that had once been the island of Kam.

Craig turned to his exhausted fellows. "It's over," he said with conviction. "Pacifica has achieved stability. We've won!"

As far as the eye could see through the rifts in the perpetual steam there was only land. The stink of the underocean ooze was indescribable. But that would not last long. The heat of the sun was drying it out rapidly. Within a few months muck and slime would have changed into a soil of unparalleled fertility, hundreds of feet in depth—a veritable Garden of Eden for the agriculturist.

In his mind's eye Craig could envision this vast territory as the future granary of the world, as the habitation of millions of earth's dispossessed. Breder was dead, but his spirit lived on in this tremendous monument to his genius.

Yet there was no exultation in Craig's voice. For one thing, Nijo was without doubt dead. Not only had all their attempts to communicate with the bottom of the shaft failed, but at the very moment that the convulsions had ceased, the instruments also recorded the sudden stoppage of the automatic plungers.

Was one the cause or the effect of the other, or was the coincidence accidental? In any event, Nijo was dead, otherwise he would have found the means to repair any ordinary break. The power lines through the shaft still functioned.

Besides, they were cut off from all communication with the outside world. From the very beginning, on their first emergence from the tunnel, they had discovered that the transmitters were dead, the receivers as well.

That was bad enough, but what made the whole affair suddenly sinister was Gregori's discovery that they had been deliberately tampered with, in such fashion that repair with the equipment at hand was impossible.

Kai-long sang his eternal hymn of hate. "The Easterners did that before they fled," he declared vehemently. "They took every plane, so that we couldn't escape. It all ties up, honored friends: Nijo down below; this vandalism up above. Something is brewing."

Craig and Gregori, however, paid no attention to his Cassandra croakings. The fact remained that Nijo was even then quite likely dead, a martyr in the line of duty. And the problem of continued existence was a pressing one. There was not a minute of that long nightmare week when they did not expect immediate death. It was a miracle that, battered and tossed about by titanic cataclysms, they remained alive.

They stared soberly down upon the great, shrouded, prehistoric plains. In each mind were the same unexpressed thoughts: What had happened to the rest of the world? Had the sea, instead of disappearing into yawning fissures to replace the plastic pocket, spilled over on the coastal plains? Had terrific earthquakes shaken the cities of the earth into ruins? More urgent still—were the rulers of the world even now sending forth rocket cruisers to scout the new-made land, to seek for them on their solitary peak in the midst of still drying corruption?

THEIR situation was fast becoming desperate. Their food supply had given out. Most of the stores had been washed away or had disappeared forever into the gaping fissures. Water there was none. The springs which had formerly watered the island were irremediably gone, and it would be long before the oozing plains would dry sufficiently to retain the returning rainfall in lakes and streams.

On the eighth day the last precious gill of water was distributed, the last morsel of condensed food gulped down dry. Silently they stared out into the sullen-clouded heavens, peered into the vaporous swamps below. It was like a new planet, untouched by life in any form. Nowhere was there a sign that somewhere else mankind swarmed in great cities, lived and loved and bred and hated. They were alone, more completely cut off from humankind by impassable ooze and the destruction of all means of communication than if, in truth, they had been marooned on some far-distant planet.

Gregori said suddenly, in flat, unemotional tones. "I see rocket planes heading this way."

Craig and Kai-long jerked around, crying simultaneously: "Where?"

The North-European engineer pointed wordlessly. They followed his gesture. Far off to the east the clouds had parted. It was early morning. The newly risen sun poured through the rift his dazzling shafts, slanting in long streamers over primordial swamp.

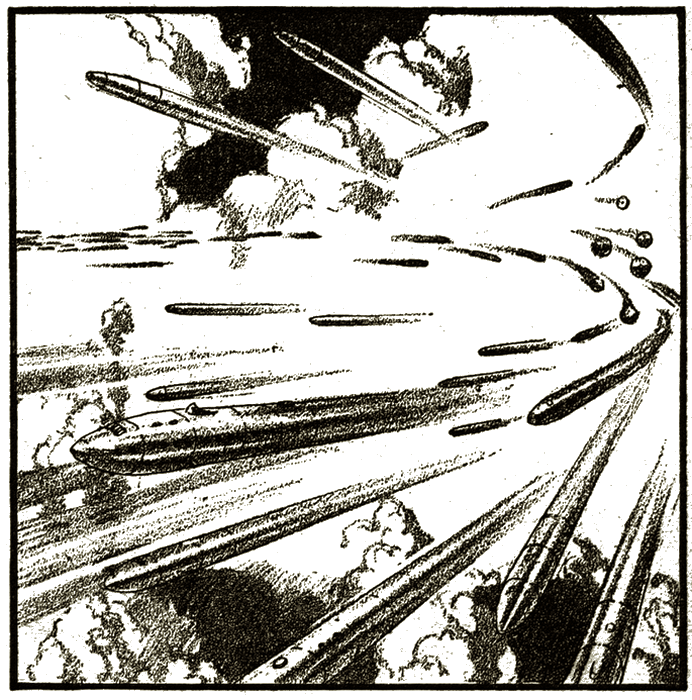

Across the blare of light, black spots moved swiftly, purposefully—hundreds of them. On they came, hurtling directly for the towering island of Kam, streaming behind them sword flashes of flame, bringing within their lean bellies men and the civilization of this year of grace, 2010!

On they came, directly toward the island,

streaming behind the sword-flashes of flame.

Again Gregori spoke. "I knew they'd come," he said simply. Things were uncomplicated like that for his placid faith in humankind.

But Craig frowned and squinted sharply against the molten glare of the sun. Strange that a rescue squadron should run to the hundreds of ships; stranger too that those long, lean lines connoted battle cruisers.

Kai-long rose with bitterness in his slitted eyes, hate in his voice. "Those are the squadrons of Chu-san," he cried. "There is trouble ahead."

They looked again. There was no question about it now. As the great planes grew into form and solidity, they could see the hornet-like stripes of black and yellow that betokened the armament of the Eastern Empire.

Craig shook off his own private doubts almost angrily. "What difference does it make who rescues us?" he demanded. "Chu-san's forces were nearer to us. Naturally they got here first."

Kai-long stared at him quietly. His face had become placid, enigmatic. He too was an Oriental. "It is no use," he said softly. "The minds of the Westerners are like those of young children. They do not understand the tortuous channels of the Easterners' thought." He got up, pulled his loose-fitting coat tightly about him, salaamed with grave solemnity.

"Farewell, oh honored friends," he said. "It is not for my humble self to sully the triumphant approach of the mighty Chu-san."

THEN he was gone, vanished from their sight. One moment he had stood before them, bowing almost to the ground; the next he had disappeared soundlessly behind the ridge the temblors had thrown up.

"Come back, Kai-long," Gregori called in alarm, lurching forward in pursuit.

"You're crazy——"

Craig caught at him, held him firmly. His brow was furrowed with secret doubts. "Let him go, Gregori," he said. "Kai-long is not crazy, nor a fool. You forget he is a fugitive rebel in the eyes of Chu-san. The Easterners would make short shrift of him if they ever caught the poor devil."

Gregori stared, bunched the muscles on his great shoulders. "They'd never dare," he said.

"Dare?" Craig echoed with an uneasy laugh. "Who could stop them? You forget, Gregori, might, in this year of civilization, 2010, makes right." He shaded his eyes at the fleet. Already they could hear the roaring blasts of the rocket tubes. "And just at this present moment," he added, "Chu-san has all the might."

The battle cruisers cradled to the sloping terrain in cushioning jets of fire. Exit ports slid open, and slant-eyed men of the East poured out in disciplined formation.

Craig moved forward to meet the black-and-gold bedizened commander. For himself and Gregori he had no fear, but he was worried about Kai-long.

Sooner or later——

He extended his hand. "I am glad you came," he said heartily. "Our provisions are completely exhausted."

The Easterner ignored the proffered hand. He barked out orders in the singsong syllables of his race. Soldiers scattered obediently—some to the mouth of the great tunnel, others to the various buildings that were still intact, while a group with suddenly showing dynol pistols filed ostentatiously to either side of the two engineers.

Craig's eyes narrowed. "What's the meaning of this?" he demanded.

For the first time the commander permitter himself a grin. "It means, oh barbarians," he declared brutally, "that you are both under arrest and subject to the blessed will of his august presence, the Emperor of the East, soon to be lord of all the world."

Some one near Craig growled like a wounded bear. He spun around to see Gregori, blue eyes flaming, great hands outspread, jerking forward. His arm shot out, clamped on the lunging man with a grip of steel. Just in time, for the dynol pistols were centered on the North-European engineer, ready to fire.

"You fool!" he whispered sharply. "Don't you see they're aching for a chance to wipe us out. You're furnishing them with the best excuse."

Still growling, Gregori pulled back, while Craig faced the commander with steady eyes. "You can't get away with this," he declared. "It means war with the British-American Union, with North Europe, with the rest of the world. Your master is biting off more than he can chew."

THE EASTERNER spat contemptuously. "Bah! You are fools, unfit to wash the feet of our race. All these years you toiled and labored—for us. Did you really think we'd permit this new and mighty land you have so kindly raised from mother ocean to be turned over to others? Idiots, imbeciles! We hugged ourselves in secret and laughed at your childish faith in treaties. When Nijo gave the word, we came."

Craig nodded quietly. "I thought as much. That was why he planned it so he could remain below. He used a beam transmitter to communicate with you."

Kai-long had been right, and he wrong. He told himself that without rancor, without bitterness.

"But still it does not matter," he went on. "You've seized Kam temporarily. It won't be for long. Within days, or weeks at the most, the other nations will send exploring expeditions. You will surprise and destroy the first, but later overwhelming armadas will proceed against you. You cannot defeat the combined resources of the world."

The commander smiled subtly. He did not seem at all alarmed at the American's dire prognosis. Then their attention was distracted by a commotion at the entrance to the shaft. Soldiers were prostrating themselves flat on their faces before the plain-smocked figure of Nijo.

The Eastern engineer ignored their genuflections, came toward the group around Craig. His saturnine features were immobile, his eyes veiled, as always, as they rested on his former comrades. Gregori ripped out an oath, but Craig said nothing. There was nothing to be gained by losing his temper now.

The commander of the air fleet fawned on the newcomer. "Welcome, most illustrious one," he greeted Nijo effusively. "Our master is most pleased with your efforts; he has been so gracious as to direct me so to inform you. I hasten to lay our humble lives at your feet to trample on and do with as you will. The master so commands."

Nijo disregarded the protestations. His black eyes fixed somberly on the commander. "You have failed in your duty, Ala Beg," he said coldly. "Your fleet was due yesterday, even as I had ordered. Had these barbarians not been utter fools, they would have suspected us before this. By wrecking the power house, our carefully laid plans must have failed. It was not your fault that did not happen."

The commander's features went dirty-gray. "There were storms and blasts of steam from the seething land," he explained trembling. "It would have been certain death to venture from our hidden ports before this."

"Death?" echoed Nijo contemptuously. "You, a mere weapon in the hands of the mighty one, speak of death as an excuse! Beware lest the master make you implore death to come and release you from your unworthy life."

Craig stepped forward, fists clenched, eyes bitter-slitted. "You, Nijo," he blazed with fierce scorn, "have planned this from that first day, twenty-five years ago, when you joined Breder at the behest of your scheming dictator. All these years you concocted this treachery in the distilled venom of your mind. This work, that was to us a sacrament and a consecration, that was to be the salvation of a world in distress, the harbinger of a newer and more glorious day, was to your slimy Eastern mind merely a way of aggrandizement for your vile ambitions."

NIJO stiffened. For a moment lightning leaped in his inscrutable eyes. The commander pressed forward eagerly. "Let me kill the dog for his sacrilegious language," he begged. Anything to ward off the wrath that had been expended on himself.

But Nijo waved him aside. The flames had died; once more he was his usual cold, contained self. "Take heed how you speak, Kenneth Craig," he said without heat. "I hold no hate for yourself, nor for that North-European oaf who was your assistant. Your lives are in my hands; I besought that much from the mighty one and he deigned to grant them to me. Take heed lest you throw them away unwittingly. You are engineers—good ones. So am I. But my duty to my race far outweighs the petty considerations you speak of so rashly. Take them away, secure them properly, but do not mistreat them," he ordered.

Soldiers sprang to their sides, seized their arms. Craig did not attempt resistance. It would have been suicidal. But one parting shot was to be his. "Kai-long was right all along. He said——" The American stopped quickly, and bit his tongue. But it was too late. The damage had been done.

For once Nijo was shaken out of his immemorial calm. His sullen features writhed with hatred. "Kai-long!" he cried. "That offspring of a pig, that rebellious slave! Quickly," he snapped to the commander, "where is he?"

The man looked bewildered, spread his hands placatingly. "I do not know, illustrious Nijo. There were no other dogs of foreigners here but these two."

The Eastern engineer wheeled on his prisoners. "Where is he?" he threatened. "Speak with quick, truthful tongues or it will be the worse for you."

Craig kicked Gregori's foot in surreptitious warning. "Poor Kai-long!" he said sadly. "He was drowned and washed to sea the very first day we emerged. A great tidal wave broke over us."

Nijo surveyed him sharply. Craig's features were screwed up in seeming sorrow. Gregori's face was a placid blank. The Easterner was only half satisfied with his scrutiny. "If you are lying——" he stared, and left the threat hanging unfinished. "Search the mountain," he rasped to the soldiers. "Search every nook and cranny. Your heads will fall if he is alive and you do not find him. As for these, away with them. I have other and more-important work to do."

A WEEK passed—a week of agonized expectation each day of the firing squad, of anxiety for Kai-long, of wonderment as to the outer world. They were not brutally treated, but day and night heavy chains weighed them down in the small chamber underneath the power house where they were confined. A huge, surly Easterner was always on guard, fingering his dynol pistol with significant gestures.

They dared not ask directly about Kai-long. In the face of repeated questionings they had stuck stoutly to Craig's original story. The fact remained that he had not been found. But, Craig realized with a sinking heart.

That might only mean that he had deliberately committed suicide rather than fall into the hands of his enemies. It was impossible to evade a well-organized search in such narrow limits.