RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

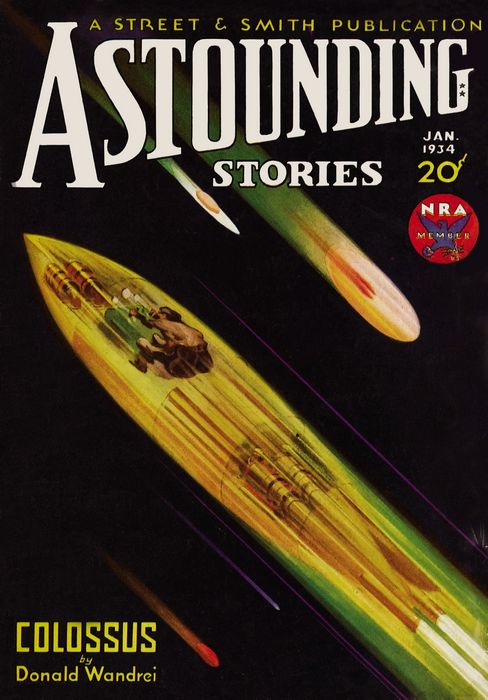

Astounding Stories, January 1934, with "Redmask Of The Outlands"

THE CITY-STATE of Yorrick was a huge cube of blackness on the shores of the ocean. On one side stretched the interminable Atlantic, billowing and sun-bright; on the other, the almost as interminable forests of the Outlands. In between lay a sudden cessation of light, of matter itself—a spatial void of smoothly regular outlines.

The oligarchs of Yorrick had builded well to protect themselves and their millions of subjects from outside attack. Against the warped, folded space that inclosed the three levels of the city, powered as it was by the gravitational-flow machines, the most modern offense was impotent. No weapon conceived by man could break through.

The oligarchs laughed and took their ease in the pleasure palaces on the top level of the beryllium-steel, quartzite city. The space-warp made an impregnable defense against the assortment of city-states which dotted the American continent. Whatever diverse forms of government they possessed—oligarchic, democratic, dictatorial, communist, socialist, fascist—they achieved paradoxical unity only in a common, mutual, ineradicable hatred. This of course was a heritage from the Anal break-up that destroyed the world state back in 4250 A.D.

Civilization ebbed and flowed for centuries until strong men, and strong groups of men, drew apart into the vast forests that had overlaid the continent, and builded themselves great cities—self-contained, self-powered, self-sufficient—into which the weaker elements fled perforce for safety. The Outlands were left—gloomy, close-branched depths where the sunlight barely percolated, where wild beasts lurked and wilder men roamed—outlaws.

The oligarchs of Yorrick gave themselves up to every form of luxurious idleness, to sybarite arts and dalliances. Not all of the great families had degenerated, though. The Marches, for instance, from time immemorial held executive power with strong fingers; and Charles of the Marches was the greatest of his line. It was he who had sealed the levels hermetically, and caused emergency power equipment to be moved to the third tier. The technics and scientists of the second level were loyal, no doubt, but it was wise to be secure from all surprises.

The workers of the first level—the sprawling, rabbit-breeding mass of them, who tended the great whirring machines in the tunnels that tapped the sea itself for power—were brutish and submissive enough. But the oligarchs had not forgotten the great uprising of 5310, when the sudden rush of blinking owl-like workers had almost wiped them out.

So Charles sealed them in, and forever cut them off from the outer world. All their simple lives they worked, ate, quarreled, and spawned in artificial light, propping the foundations of the other levels, keeping the space-warp intact, preparing the synthetic food pellets, tending the atomic integrators that built up complex elements and compounds from sea water. Visor-screens raked every nook and cranny of the lower levels—privacy was a thing unknown. Automatic high-pressure chutes kept steady streams of consumer goods pouring onto the third.

THE third level was open now to the outer sun. The oligarchs preferred natural sunshine to artificial rays, the fresh winds of heaven to ventilating systems.

There was unusual activity on the broad crystal ramp—movement, color, and bustle. A great ship nestled in the ways, its bright metallic sheath tapering to steel-nosed rapier points. Around it clustered a dozen smaller ships, squat and heavily armored—the battle fleet of Yorrick.

The final group disappeared into the entrance port, the gangplanks rolled up in visibility against the side, the oligarchs in their brightly fashioned garments ebbed away, and the slide-ports moved into position.

Communications-Technic, B-54, watched the visor-screen from his cubicle on the second level. A ticker buzzed and Captain Arles, A-6, molded into form on the screen. The captain nodded curtly.

"We are ready. What's the last report from the Outlands?"

B-54 pressed a button. A telautograph at his side sprang into a series of dots and dashes. It was connected with the range-viewers that constantly swept the Outlands. B-54 studied the cryptic symbols, turned to the visor-screen. His voice was formal, expressionless.

"Beg to report series of vibrations from Point 6-9-4-3."

The captain's bluff, pock-marked face went grave. "That's on the Pisbor Channel?"

"Yes, sir."

The captain thought rapidly. There was precious freight aboard the Arethusa—human, as well as cargo. Of course the convoy was adequate protection, still——

"Contact Pisbor at once," he ordered. "Swing the channel on Route 2. We must take no chances."

"Yes, sir."

B-54's fingers flew. The captain's features faded from the screen; another's took their place. It was the communications-man of Pisbor, blank-faced, almost robot-like.

"Hello, Odo," said B-54. "Last-minute change. Switch contact to Route 2."

"I take no orders from Yorrick," said Odo stolidly.

"You will," B-54 told him. "Your own man, Ambassador Gola, gave the word."

B-54 chuckled at the ludicrous change on the robot features. Panic, haste, fear! It was worth the lie. Odo swung a lever; B-54 pressed a button. The powerful beam-waves bent southward in a huge arc, forming a guarded channel for ship passage along the longer Route 2.

"Contact."

"Contact!"

Odo was gone; instead, the technic saw the cradled field of the Arethusa and its convoy. He closed a switch. At once the great vessels lifted up into the sunlit sky, slanting steeply, borne along on the powerful surge of the beam-ray.

A spark of human longing gleamed in B-54's eye. It was penal to keep the screen open longer than duty required. He took a swift glance at the mirrored sky he had never seen in actuality, snuffed at the incredible fragrance that did not exist for him, sighed, and snapped off the screen. As he did so, technic C-31, in a neighboring cubicle, laid down the impregnable ceiling of the space-warp. He, too, had received warning of unusual vibrations in the Outlands.

THE Arethusa bowled easily along the invisible channel. At five hundred miles an hour, even by the long way, the ship should not take much more than an hour to reach Pisbor. The battle cruisers surged alongside in close-knit array, hemming her in, protecting her with their heavily armored sides and powerful cosmo-units.

Captain Arles, however, was worried. His blunt, seamed fingers drummed an erratic tattoo on the table before him. The others in the luxuriously equipped lounge looked at him irritably. He was there on sufferance only; a technic seated with presences.

There were four of them: Charles of the Marches, a tall, commanding man, with the arrogance of lineage stamped on his strong curved nose, on his firm molded lips, in the flash of his eye when crossed. Next him was his daughter Janet, a slight wisp in comparison with her father, rather pretty in a weak sort of way.

Across the stellite table, half facing her and half turned to her father, very respectful in his demeanor, yet with a faint sneer on his dark, ugly features, was Gola, personal ambassador from Carlos, and dictator of Pisbor. His mission had been eminently successful, yet he did not seem pleased.

The last man slouched carelessly in his chair, eyes half closed. He was big and blond and his lips were smiling. Yet Comrade Ahrens had suffered failure in his mission. He had been unable to prevent the proposed marriage. The very presence of his companions on the Arethusa was positive proof of his failure. He would have to report to his comrades of the Soviet council of Chico, the great communist city-state on the shores of the northern lake, that the marriage was going through.

Janet of the Marches was speeding swiftly to Pisbor, to be united with the elderly Carlos in holy matrimony, thereby uniting two powerful city-states in alliance for the first time in centuries. The delicate balance of power was about to be destroyed, and there was good reason to fear that the coalition meant menace to his beloved city.

"Stop that infernal drumming, A-6," Charles said sharply.

The captain flushed. "I'm sorry, magnificence. It shall not happen again."

Comrade Ahrens leaned forward, speaking softly. "Captain Arles has something on his mind?" He did not approve of numbers for men.

The captain flashed him a grateful look. "Yes, sir," he said.

"Well, what is it?" Charles said impatiently.

"It—it's about the Outlands, magnificence."

"Dangerous, I suppose," Gola sneered.

The captain squared his shoulders. He spoke earnestly. "They are, sirs. Before we started, there was a report of vibrations on the Pisbor Channel. That's why we routed through Washeen. I'm afraid——"

"Of what?"

"Those vibrations, sirs, were characteristic of Redmask!"

There was a startled murmur.

"Redmask!" The dread name swung around the table like a multiple echo. The grim, implacable outlaw who raided the air-channels, from whose pursuit there was no escape! Before his coming, the outlaws had been a scattering of petty pirates; now they were organized, dangerous. Within the year, five ships had been lost; none ventured along the airways except under convoy. No one had ever seen Redmask's face—he took his name from the flexible, blood-red globe that always encased his head.

"Redmask!" Charles reiterated, and cast Gola a meaningful look. One of the reasons for his journey was to discuss with Carlos joint action against the outlaw. Comrade Ahrens caught the side glance and smiled comfortably.

"Bah!" continued the oligarch. "Our battle cruisers will take care of him." He pressed a button under the table, spoke rapidly.

"Send wine in, and the jester. We wish to be amused."

Almost before he finished, two men stepped through an opening slide-door. One was young and dressed in the single brown garment of a worker. His head bent obsequiously over a tray on which rested a cluster of rose-red cubes. He hurried from one to the other, offering the cubes with averted gaze, as if his very look would contaminate the presences.

They swallowed the tiny wine pellets, and a sparkle came into their eyes with the coursing of the concentrated stimulant through their veins. Captain Arles sat stiffly, ignored in the general chatter. Technics were not allowed to drink. As the worker bowed low before Janet, she trembled violently, so much so that the concentrate dropped from numbed fingers. The worker stooped, picked it up, and withdrew hurriedly from the lounge, brushing against the man who had entered with him.

Janet's eyes followed the worker, startled. There was a flush on her cheek, an animation that had been missing before. She did not even see the jester.

Nevertheless he was well worth looking at. He lounged against the door edge, a shock of tawny hair retreating from bright-blue, ever-roving eyes. Grimness tugged at the corners of his lips, nor was there any subservience in the easy flowing grace of his posture. Underneath his arm he carried a wooden case of curious shape.

Charles turned and saw him. "Ha, here is the jester," he said jovially. The wine had loosed his usual aloofness. "Give us a song; one of your regular home and country and patriotism type. We wish to laugh."

The jester's eyes glinted. "I am not your slave, Charles of the Marches," he said coldly. "I play what and when it suits me, not your drunkenness."

Gola jumped furiously to his feet, his hand reaching under his yellow tunic.

Charles caught his arm, smiled. "He's amusing, the jester. A democrat, you know; from Washeen."

Gola sat down again. "One of those, eh? Licensed fools, throwbacks! Too stupid to realize that the world has progressed beyond them. Ready to starve for their independence; for their individualism. Bah!"

"I hear you raise natural crops," said Comrade Ahrens curiously. "Dig in the soil with spades and plows, and depend upon muscular toil and the vagaries of sun and rain."

"Yes."

"Why? Synthetic foods are easier to make; the machines do the work."

"That's just it," said the jester. "We prefer to work ourselves; we are not bound to machines."

The company roared. Even A-6, technic, permitted himself a contemptuous smile at the crazy democrat. Refusing the blessings of science, of organization!

"You are right, Charles," gasped Gola, wiping the tears out of his eyes. "He is an amusing wretch."

"I hear the crops failed you this year at Washeen," interposed Comrade Ahrens. "The machines never fail."

The jester stared with bright blue eyes, fathomless.

"Yes," he said at last in a low tone. "They failed. None of you will help."

Janet spoke up suddenly: "Why don't we do something, father? We can't let a million people starve."

"Don't bother your head with what doesn't concern you," the oligarch growled. "They are individualists. They refuse to be organized, to submit to a decent form of government. Let them stew in their own folly."

"Hear! Hear!" yammered Gola.

Charles made a quick gesture of distaste. He did not like Gola; he was certain he would not like Carlos, the dictator. The marriage was purely a matter of cold, calculating policy.

"Enough of that," he said. "Let us have music, jester."

The jester glanced surreptitiously at the time signal on his wrist. It lacked a minute of nine o'clock. As his eyes rose, he caught a simultaneous gesture on the part of Comrade Ahrens. The communist had been intent on the time, too. The big, blond man looked away quickly; he seemed to be waiting in strained unease.

The jester smiled thoughtfully, opened his curious wooden case with maddening deliberation, and took out—a violin! The instrument was of incredible antiquity, the only one of its kind in the world. Inside the case could still be seen dim lettering— Antonius Stradivarius fecit 1715.

The resined bow poised in the air, waiting. The time signal on his wrist flashed—precisely nine o'clock. The bow descended, caressed the gut of the priceless old violin in the opening strains of an ancient, ancient song—Schubert's Ave Maria. The delicately weaving melody floated smoothly through the lounge, the ecstatic prayer of the human spirit, the accumulated longings of all mankind for the unattainable.

For a moment there was a hush. Janet hung on the notes with parted lips. Her encounter with the worker had softened her, made her amenable to the sentiment implicit in the olden piece. How different from the intricate cerebral elaborations that were considered music in Yorrick!

Charles listened with a smile. It was quaint, primitive, and therefore amusing. Gola was frankly bored; if one must have a meaningless succession of notes, let it at least be something brassy, fiery with martial wind, such as was blared out by the unhuman machines at Pisbor.

Comrade Ahrens was not listening. In the first place, music had no place in a well-organized scientific state; in the second place it was already after nine o'clock.

The lovely yearning strains rose and fell, casting a magic spell over player and girl. Then the bow caught harshly against the gut, made an eerie screech. The floor heaved unsteadily; there was the dull thud of a bump.

Captain Arles jumped to his feet, his eyes wide with alarm. The others were on their feet, too. Only the jester seemed unperturbed. He tucked the violin back into its case, snapped the lock.

There were confused noises outside, the tramp of many feet.

The captain sprang to the visorscreen switch. Charles muttered an oath and reached for the tiny cosmo-unit at his belt.

"No one is to move," said a deep bass voice.

A-6 froze in his tracks, Charles dropped his hand to his side, and Gola cowered away from the figure in the slide-door.

"Redmask!" gasped the technic.

The figure bowed mockingly and stepped into the room.

"Himself!"

Behind him poured a dozen men—wild, powerful-looking fellows. Men of every race, fugitives from every city-state, outlaws with prices on their heads. Conite disruptors trained on the presences, making resistance suicidal.

THE figure that held all eyes, however, was Redmask himself, the fabulous sinister outlaw of the airways. He was tall and lithe, his slender body encased in a green-leather jerkin, his head hidden under a blood-red globe of penetron.

"We've no time to waste," resounded his deep bass. "Charles of the Marches, Janet of the Marches, Gola of Pisbor, and Comrade Ahrens of Chico—follow us."

Janet's hand went to her heart. "Where are you taking us?" she quavered.

The deep voice chuckled. "To the Outlands for ransom. Don't be afraid, pretty one. You won't be harmed."

Charles stood straight and arrogant. "You are mad, Redmask. This time that globe of yours has placed your head in a noose. The battle fleet will blow you to nothingness."

The hollow chuckle resounded again. "Yorrick's fleet proceeds calmly along. It suspects nothing.

You forget my ship is equipped with invisibility magnets to bend the light around us. We'll be far away by the time the Arethusa's signals work again. Get going."

The outlaws sprang to their victims, prodded them along with deadly disruptors.

Comrade Ahrens burst out suddenly: "This is an outrage. You'll be made to pay heavily for this. Chico——"

"Shut up," growled a shaggy-haired Outlander, "or I'll blast you!"

A man picked up a stellite chair, heaved it at the visor-screen. The instrument was smashed into fragments.

At the sound some one flung himself into the room. It was the worker who had served the wine cubes. He stared wildly around, saw Janet prodded by ungentle shoves. An anguished cry beat from his throat: "Janet!"

The next instant he was upon the captor, thrusting at him with bare hands. The man staggered, flung him off with a heave of powerful shoulders. A savage oath snarled on his lips; he raised his disruptor.

"Don't!" cried Comrade Ahrens involuntarily.

The man lowered his weapon with a growl.

"Lucky for you you're a worker, not a damned oligarch. Next time I'll kill you."

Then they were out, the slide-door closed behind them, jammed by a blow into immovability.

The worker sprang to the door, beast upon it, crying out, "Janet! Janet!"

The captain remained rooted to the spot, palsied by the vision of Redmask. The jester stared at the smooth surface of the door as though the answer to a curious riddle lay there. His brows were furrowed. Only indomitable self-control had prevented an outcry at the sight of Redmask and his outlaws. Ignored by the raiders, the unimportant democrat had noted everything; the hesitating walk of Redmask, the strange behavior of the worker.

Suddenly he made a gesture of annoyance. He ripped the violin out of its cover, fairly flung the bow across the strings in a wild dance or saraband.

"Are you mad?" ejaculated the technic.

But the player paid no attention. The bow raced on, the notes poured out in a glittering spray, until a final flashing crescendo brought the piece to a close. The jester's brow was dewed with sweat as he replaced his precious instrument in its case.

The worker swung around with a tortured, furious face. He was no longer stooped; his voice held a commanding ring.

"A-6, smash that door down; get a signal through to the battle fleet. Your life depends on it. You, fool, lend your shoulder. We've got to break through."

Captain Arles took a short step forward. "You forget yourself, worker."

The man wiped his face with a brown sleeve. The stain vanished. Pale oligarchic features emerged.

The technic moved back, bowed almost to the floor. "Edward of the Hudsons! I didn't know——"

"Of course you didn't. All together now."

The three bodies crashed solidly against the jammed door. There was a creaking of metal, an outward bending. The next concerted heave, and they were through. Members of the crew surrounded them with a babble of words. Edward pushed imperiously past. In seconds the captain organized discipline out of terror, had rigged up an emergency set. Though he worked with breathless speed, Edward, pale and agonized, lashed him on with excoriating words.

At last the screen gleamed clear. Outside the scene was peaceful, undisturbed. The battle fleet swept easily along, hemming in the Arethusa, guarding it with squat, armored bodies. The Outlands were a rippleless carpet of green. Nowhere was there a sign of the bold raider, of Redmask and his captives.

In seconds more the scene had changed. The armored cruisers shot into emergency power, rocket tubes roared into flaming combustion. Out of the channel they flung, scattering in mad search for an invisible ship.

"They'll never find it," said the jester. "I would suggest——"

The young oligarch turned on him furiously. "Who are you to suggest?"

A queer smile played around the democrat's lips. "Only a jester," he remarked calmly, "but a free man nevertheless. I am trying to help. Without me you will never find your lady."

The oligarch searched his face. Their eyes held. Some strange bond of sympathy passed between them. Edward came to a sudden decision.

"I accept your help," he said. "We love each other—Janet and I. Charles, from motives of policy, pledged her to Pisbor's dictator. I could not let her go alone; I disguised myself—I thought——" His voice broke off, his pale, slender hand caught the muscular jester by the shoulder. "We must find her!"

"Trust me," said the democrat. "My real name, if it makes any difference, is Stephen—Stephen Halleck. I have my own reasons for finding this—Redmask. Give orders to proceed to Pisbor as if nothing had happened."

Edward started to say something, shrugged his shoulders. Stephen, jester, democrat, whatever else he was, radiated confidence. And no other course seemed of any practical value.

PISBOR labored under unprecedented excitement when they arrived. The great dome of impermite lay dazzling in the sunshine. The electron-stripped element, fabulously heavy, was as impenetrable to offensive weapons as the space-warp of Yorrick, the web-curtain of Chico. A section rolled open as the Arethusa approached, closed automatically behind it. The battle fleet remained disconsolately outside. The dictator, even with marriage ahead, was taking no chances.

The Arethusa had hardly touched its cradle when Edward of the Hudsons flung out. All thought of disguise was gone; command clung naturally to him. Stephen was a few respectful paces behind. As democrat and licensed jester, he was innocuous, privileged to roam as he pleased. Captain Arles and the crew remained on the ship, sealed in by the vigilant guards of the dictator.

Stephen stared curiously around, though it was not his first visit to the city.

Within the orbed confines of the impermite dome were scattered blockhouses, cubed barracks built of penetron, the synthetic translucent substance that could be rendered transparent only by the infra-red beam-ray of the dictator. Thus no smallest act of his subjects escaped his scrutiny; an invaluable deterrent to conspiracies. As further protection, it was possible to cross-rake the thoroughfares between the blockhouses with deadly conite disruptors.

The squares of the city were black with Pisborites, all staring upward through the dome at the massed fleet of Yorrick. They were powerful-looking brutes, broad-shouldered, low to the ground, with long animal-like arms. Their squat faces were dull, uninformed with intelligence, degraded through long centuries of subservience. Even now, with the strange spectacle of the Arethusa within, and the battle cruisers outside, the apathy of their countenances was unmoved, their talk a low chattering.

A voice ripped out of the air, unhuman, metallic; a machined combination of syllables not issuing from human larynx.

"Let the strangers ascend to my presence."

Edward looked up in astonishment. It was his first visit to Pisbor. It was then he noted the great black-shining globe suspended from the topmost round of the dome. A small oval ship came slanting down to drop at their feet. A port opened, and a man gestured for them to enter. The port closed and the vessel ascended, coming to a cradling jar against the surface of the sphere.

Their conductor unhooked a tube from his belt, flashed it over their bodies. At once they sprang into X-ray illumination. The solid flesh seemed to melt away, leaving only dark-shadowed skeletons behind. Edward exclaimed angrily, but Stephen checked him with a smile.

"It's a search beam," he explained. "The dictator makes sure that no one approaches his august presence with weapons."

The tube flicked off, and flesh clothed them solidly again. They were ushered into the great sphere, the dwelling place of the dictator. This was a city in miniature. Stores of supplies, food pellets, weapons, enough for a long siege, filled half the curving sides.

Picked Pisbor men, trained for special duties, glided around, catfooted. Complicated machines shone white against the black, operators vigilant at the controls. Power came from the solar rays, transmitted intact through the impermite dome.

Even in here the dictator was apart. At the top of the sphere was a smaller replica, suspended. A swinging ladder dropped down, dangling.

"Climb to the presence," said the unhuman, metallic voice.

Edward's brow darkened. "Damned if I will! I am an oligarch of Yorrick."

Stephen whispered: "There was an ancient saying, 'When in Rome, do as the Romans do.' "

"Never heard of it, but——" Edward was sensible for an oligarch.

They swung themselves aloft and entered the smaller sphere. The jester held tight to his ever-present violin.

Light gleamed dazzlingly, making them blink. The dictator was in semidarkness. Carlos, thirteenth dictator of Pisbor, lived in constant fear of treachery. Around him now were his most trusted underlings, yet at night even they must descend, leaving him alone. His fingers never strayed from the arms of his chair, where button controls unleashed terrible weapons at a touch.

AN old, incredibly old, man he was, with wrinkled, parchmented skin and pouchy folds, clad in gorgeous finery that served only to mock his ugliness. Only the eyes showed life—they glittered with hard ruthlessness.

He glanced indifferently over the jester, fastened his eyes with strange intentness on the young oligarch. Edward stood proud and straight under the scrutiny.

Suddenly the clawed fingers moved on the arms of the chair. The metallic voice issued, though the dictator's lips did not open. This was an artificial sounding board; the dictator had been dumb these many years.

"You come from Yorrick?"

"Yes."

"Where is Charles of the Marches, and Janet, my bride?" Edward controlled himself with an effort. Janet in the arms of this hideous caricature of a human being—better death, better even her present predicament.

"They have been captured by Redmask," he answered steadily.

The hard unwinking eyes stared with mask-like quality.

"Redmask!" repeated the voice. "Yes! I know him. Once he was my slave; now he is a traitor." Stephen's lips twitched.

Edward asked: "How do you know?"

"His mask. It is penetron; the secret of its manufacture is my own. The slave stole it."

"You must help, Carlos," said Edward impatiently. "There is no time for much talk. Equip your fleet for instant service. I shall return to Yorrick for more ships and more men. We must root out Redmask once and for all."

The dictator sat like a graven mummy. "Softly, Edward of the Hudsons. I know my task; orders have already been issued. Let us talk about you."

"What about me?"

"The safe conduct of the Arethusa calls for two oligarchs only; Charles and Janet of the Marches. There is no mention of an Edward." The young oligarch flushed. "At the last moment, too late for the identification signal, Charles asked me along."

"The story is thin," retorted the inexorable voice. "Why, then, are you dressed in worker's brown?" Edward took a deep breath, determined to bluff it out. "Very well, then; you disbelieve an oligarch of Yorrick. The Arethusa leaves at once."

"Not until I give the order."

The hot-headed youngster took a step forward. "You dare hold me a prisoner? The Yorrick fleet will blast you."

The withered mask broke into a bony grin. "Impermite will withstand even your battle cruisers. In the meantime——"

A fleshless finger depressed a button. At once Edward congealed in forward movement. Stephen could see the furious astonishment on his face as he strove ineffectually to move. A paralysis ray held him tight. Two Pisbor guards sprang forward, caught at him to prevent his falling.

"Take him away," said the voice. The helpless oligarch was lifted unceremoniously like a sack of Washeen flour and hurried down the swinging ladder. The jester's eyes caught the imploring glance of the young man, but there was no answering gleam, nothing but mild indifference.

He turned to the motionless dictator. "And I, Carlos?"

The toothless mouth split contemptuously. "Make me laugh, jester. I am gay with consummation of my plans."

The democrat looked at the grinning death's-head in front of him; tilted his firm-molded face, laughed long and vigorously.

"Laughter, is it, then, oh Carlos? That means music."

"Music! Ha, ha!" the mechanical voice grated. "That squeaking and squalling of your barbarous instrument sounds more like a Pisbor man with a bellyful of opine. Now there's a thought. Assail my ears with your scrapings. Yes, that will amuse me!"

Stephen looked at his time-signal. Only seconds to ten o'clock. He had gauged it correctly. He uncased the precious Stradivarius and, without more ado, drew his bow across it. A martial air sprang forth, an air that had been composed in the twenty-sixth century. Tanks lumbered into battle over quaking ground, rocket-cruisers took off with dull roars of flame, soldiers marched with grim, even tread, shells whined and ricocheted, groans mingled with the shrieks of the dying. The bow glissaded and twanged, the violin quivered with the tumult it created. Then, suddenly, a plucked note as of death snapping the cord of life, and it was over.

The dictator nodded his head approvingly.

"Now that, jester, was almost music. If it were not for the wretched squeaking of your instrument, I would almost have thought it our own."

Stephen bowed humbly. "I am sorry. I thought to make you laugh."

"It is just as well. Descend to the city. To-morrow you leave. You know the rules."

THAT night the jester roamed, unmolested, the squares of Pisbor; a licensed fool, a lowly democrat. He watched the well-fed bodies of the Pisbor men, saddened at the memory of famine in his own city of Washeen. Yet none of its citizens, he reflected proudly, would yield one jot of their free, independent life, even with death the result, for this bestial, degraded, bodily comfort; not even for the regimented, birth-to-the-grave-ordered life of the communes.

At two in the morning the squares were deserted, the domed city dark. Yet he roamed on with seeming aimlessness. For once his violin was not with him. A round, inconspicuous button on his tunic glowed redly in the restless sweep of the infra-red search beam. The democrat moved swiftly out of range. He did not wish Carlos or his underlings to know of his wanderings.

At length Stephen came to his destination; a smooth-walled building on the periphery of the city. It was the dread prison of the dictator. He glanced swiftly around. No one was in sight. The telltale button was dark in the shadows. He bent over, touched a hidden spring in the heel of his thick-shod shoe. A tiny sliver of beryllium-steel, needle-pointed, darted a half inch out. He banged the heel sharply and jarred the microscopic grid-plate into activity. The needle point glowed redly.

Lounging idly against the wall, eyes intent on the darkened square and on the button of his tunic, he moved his heel over the translucent metal of the wall. Once a change of guard passed, and he shrank into the deeper shadows. Once the restless, questing beam of the dictator glowed the button into redness. A quick side movement jerked him out of range. Three feet horizontally near the ground, two feet up with lifted heel, three feet back again, parallel, and two down. As the cutout plate fell forward, he caught it neatly, laid it softly on the ground.

Stephen threw himself flat, wriggled into the black interior. Inside, he stood up, groped experimentally. The wall gave him his bearings. Where was Edward in this morgue-like place? He did not know, and every passing moment was precious.

He moved slowly along, feeling his way. Suddenly his fingers touched something soft. There was a startled grunt, an exclamation, the beginning of a shout.

The democrat lunged forward desperately. By sheer luck his hands caught at a throat, throttled down until there were only wheezy, choking gasps. The body sagged. He released one hand, ran it over the man's waist. Something dangled. He unclipped it, twisted. A pencil beam pierced the darkness. It moved up the man's body, held on the mottled, distorted face of a Pisbor guard. The eyes were glassy with terror.

Stephen dropped his hand suddenly, caught at the conite disruptor on the belt, hefted it significantly.

"Not a word, not a sound, if you wish to live," he said in a fierce whisper.

The man nodded dumbly.

"Take me to the man from Yorrick who was brought here to-day."

The guard nodded again, cowering away from the pressure of the tube. Silently they glided through corridor after corridor. At last the Pisbor man stopped in front of a black surface.

"Open it," Stephen whispered.

The guard moved his hand over the surface, and the wall seemed to melt away. They stepped in.

"Who is there?" came a voice.

"Sssh, it is I, Stephen."

The pencil beam held on an astonished oligarch. Edward's lip curled in searing contempt.

"I might have known a democrat has no honor," he said bitterly.

"You misjudge. I am here to rescue you. Don't waste time. Get into his clothes."

Incredulity gave way to flooding relief. Without a word the oligarch helped strip the frightened fellow of his yellow-skirted garment, doffed his own. With swift, sure movements he donned the coarse material next his delicate skin; shredded his own worker's brown into long strips, while Stephen wove them into strong lashings to truss and gag the Pisbor man.

They left him there and moved cautiously into the corridor, using the pencil beam only for momentary guidance, until they emerged, breathless, from the oblong section into the open square.

"Thanks," said Edward, taking a deep breath. He extended his hand. "You are a man, even though——"

"A democrat," Stephen finished wryly, but took the proffered hand nevertheless. "The hardest task comes now; to get out of Pisbor."

"Easy," said Edward confidently. "We'll head for the Arethusa. Once inside, Carlos won't dare hold me. It would mean war with Yorrick."

Stephen shook his head. "I'm not so sure. He has deep plans I haven't fathomed yet. No. We're not going to the Arethusa. Follow me."

THE young oligarch followed. They skulked through square after square, meeting no one.

At one place, the jester burrowed suddenly into a pitchy hole, lifted a familiar case.

"Without my violin I would be lost."

They went on again, until they came to the cubicle nestled against the impermite shell, from which the exits were controlled.

Stephen stopped his companion. "Now this is what you have to do." He whispered his plan.

Edward nodded and stepped boldly up to the cubicle. His uniform was the uniform of a Pisbor guard; pencil beam and conite disruptor swaggered at his belt. His left arm had a firm grip on the jester, who dragged his feet as though unwillingly.

"Who is there?" called out the control guard at the scuffling sounds.

Edward held his face in shadow, thrust the jester violently inside.

"Orders from the dictator. Cast this wretched fool into the Outlands. He does not amuse Carlos any more."

The control man was a superior type. "Keep away!" he shouted angrily to the lurching democrat. His left hand fingered a disruptor. "This is strange. The dictator switched no orders to me. Come forward, guard; let me see you."

The oligarch came forward, weapon thrusting. The control man cried out, jerked at his belt. Stephen dived suddenly, caught his hand in a crushing grip, twisted him to his knees. In seconds he was bound in his own shredded garments, and the jester, who seemed familiar with the mechanism, swung the proper lever. A small section rolled open in the impermite, just as the button on his tunic glowed red. Stephen jerked aside, but the beam followed, and held. At once the sleeping city filled with clamorous sound.

"Run for it!" he shouted, shoving the bewildered oligarch ahead of him. Together they dived through the opening into the starless, moonless black of the Outlands. Stephen's foot barely cleared when a blinding ray slashed through the control cubicle. Had either one been in its path, he would have been crisped to a cinder.

The cool fresh air smelled sweet.

"Run as you never ran before," said Stephen. "The whole city will be swarming after us in seconds." Already the pounding of feet, the lift of sodden voices, tore through the exit gate.

There was a clearing of a hundred yards around the dome. Beyond was the thick entanglement of the forests. The fleeing pair bent heads low and scudded like scared rabbits. The city spewed forth armed men. A bellow to halt, and the searing flash of disruptors crackled through the air. Then the pitchy gloom of the trees infolded them.

The jester ran lightly, Edward barely managing to keep the phantom form in front. The noise of pursuit died in the distance; still they ran. At length Stephen came to a halt in a little clearing. He seemed to know the place.

"We are safe now," he said.

Edward sat down and panted. "If only we could signal the battle fleet."

"No good. They cleared for Yorrick at midnight. There'll be war."

The oligarch looked fearfully around at the rustling darkness. He was brave, but the city men were not accustomed to the woods—and the Outlands were dangerous places.

"What shall we do then?"

"Wait!"

Five minutes they waited, then an owl hooted. Edward jumped; his nerves were on edge.

Stephen hooted back. A pause, then another hoot, closer.

Men flitted like shadows into the clearing. A light glowed suddenly, throwing the glade into warm relief. Edward blinked and thrust up his weapon. These were outlaws; he would go down fighting.

Stephen said: "You are safe.

These are friends."

There were a round dozen of them, wild-looking fellows, all in green jerkins. Men of Pisbor and Yorrick and Chico, as well as other cities of the continent. No democrats among them. They held assorted weapons and glanced curiously at the young oligarch, but made no move.

"Just a moment," said Stephen, and took one who seemed their leader aside. Their voices came muted to Edward. The conference was soon over. Half the men melted unobtrusively into the night at a nod; the others waited.

The jester turned to Edward with a grim smile. "The matter is becoming more and more complicated. We had better be on our way."

Edward rose, faced him. Once more he was the oligarch, the holder of men's destinies in his slender hands. The rustling Outlands had frightened him, but men—never!

"Stephen Halleck—democrat—jester—whatever you are," he said with great clearness. "Before I move a step, you must explain—everything."

The jester shook his head. "Not—everything. This much, though. I am in fact a native of Washeen, a jester according to the lords of the cities. These outlaws are my friends; I sympathize with their human desire for freedom. They are willing to help me—and you, because you, an oligarch, have offered your hand to me in friendship. They hate this Redmask as much as I. It is your only chance to save Janet and the others."

Edward was no fool. There was more to it than just that. He pondered quietly and said: "Very well. Let us go."

THE men rose and the glow died out. They threaded their way with the ease of long experience through the forest tangle. A voice challenged suddenly; some one answered. Edward felt the ground giving way; they were dropping as if on a platform. The ground halted, some one tugged at his elbow. He moved to one side. There was a creaking sound, followed by silence.

Then there was light. He blinked and looked around. He was inside a huge, artificially hollowed cavern, fitted to hold an army, stored with many months' supplies. Men sat on the ground and chatted. Others slept, and still others labored in various ways. A veritable city in the bowels of the earth.

"One of the many strongholds of the Outlands," Stephen murmured in his ear. The inevitable violin was still tucked under his arm. "You will of course never reveal their secrets when you return to Yorrick."

Edward drew himself erect. "The word of the Hudsons. But—I thought Redmask ruled all the Outlands."

The jester smiled strangely. "These men do not recognize Redmask. But they are calling; things must be in readiness."

They made their way rapidly through the groups toward a tiny flier of peculiar shape. Instead of the usual cigar or oval frame, this one was hemispherical. One side was flat and a disk plate protruded.

The men watched them curiously as they passed, hushing their voices, but making no outward sign or comment. The gangplank was down. They climbed into the ship, and the port closed behind.

An outlaw met them in the little cabin.

"What are the orders?" he asked Stephen.

The jester chuckled. "Who am I to give orders! Your chief has told you where we must go."

The man laughed hastily, a bit uncomfortably, Edward thought.

"Of course, of course!"

He moved to the controls, did things. There was a slight humming sound; Edward felt the ship lifting. Stephen rummaged in a locker, and brought out close-fitting breeches and shirt of blue cellophose.

"Put these on," he said.

The oligarch obeyed without question. "Are we outside already?" he asked after a decent interval.

"Yes."

"Mind if I put on the visorscreen?"

The jester smiled. "I'm sure there'd be no objection."

The oligarch forked the switch before the blank screen. The gray dull surface turned impenetrable, light-absorbing black.

Edward was annoyed. "The screen is out of order."

"Not at all. Look!"

The democrat slid open a port. Edward peered out; saw nothing but the same palpable black. There seemed to be a total extinguishment of light.

"What does it mean?"

"You forget. The outlaws have invisibility magnets. That is why they are able to attack the airways, even under the nose of a convoy. Remember how this Redmask slipped unseen into the Arethusa."

"What is the principle of it?" the oligarch asked curiously. "None of the city-states seem to have it."

"There is a very good reason for that. Redmask himself invented it. The idea is simple. Super-powerful magnets deflect the light waves that flow toward the ship, cause them to bend around and meet again on the other side. Which means that there can be no reflected light from the ship to provide visibility, and no void in space to show as a blank spot. It also means that no light waves from the outside can come into the ship, or impinge on our retinas, so that while we cannot be seen, neither can we see."

"Clever!" said Edward admiringly. "I should have gone in for science if I hadn't been born an oligarch. But we are flying blind, then."

"Not quite. We have spy instruments that bring us the most delicate vibrations. The magnets reflect only light wave lengths. We swerve automatically from obstacles; we are held automatically to our course."

"Spy instruments!" the oligarch echoed. "Those are Yorrick's secret."

"You forget," said Stephen a bit grimly, "the outlaws are fugitives from many cities; once here they keep no secrets."

The helmsman came over, spoke in a low voice to the jester. He turned to Edward.

"News! The full battle fleet of Yorrick is over the Outlands. Half are searching for trace of Charles and Janet; the others have met a fleet out of Pisbor in battle. It's in progress now."

The young oligarch's eyes flamed.

"War! With me cooped up here, instead of at my post! Turn back at once."

"No." The answer was decisive. "We'd be cut down as soon as observed, once we lifted our magnetic flow. Furthermore, you could do no good. The whole fight is silly. Even if either fleet be totally destroyed, the barriers of the defeated city would still be impregnable against the victor. Janet's fate does not depend on the outcome of the battle; neither does Redmask's."

Stephen frowned. "I wonder why——"

"What?"

"Why did Carlos send out Pisbor's fleet?" He sighed. "It's very confusing."

THE flier settled softly to the ground.

"Invisibility magnets off," reported the helmsman.

"We are going out," said Stephen. "Snap them on again as soon as we are gone; wait here for us. In no circumstances move from the spot, unless you receive the proper signal."

"Where are we?" asked Edward.

"You'll see." The jester picked up his violin case. "My stock in trade," he explained. "Without it I would not even be a jester."

They stepped out into the early-morning air. The sun was just floating up over the treetops. The dawn was pearly with mist. In the distance towered a city. It shimmered in the mist, far more than could be laid to its account. To one side stretched a large body of water, broken into irregular patches by the intervening trees.

"Recognize it?"

Edward shook his head.

"It's Chico."

The oligarch stared at the magically dancing city. He knew now what the vibration-like movement was. The Web-ray of polarized short waves, shorter even than cosmo-units, impenetrable to any weapon or mode of attack. Behind it, safe and secure, was the greatest commune on the continent. The city of Comrade Ahrens, captive along with the Marches, and Gola, the Pisbor ambassador.

He turned on the democrat in sudden anger.

"Why did you bring me to Chico?" he cried. "Redmask would not be here; his haunts are east of the Alleghenies."

"This Redmask is an ubiquitous fellow," Stephen remarked cryptically. "He seems to have the faculty of being in several places at one time. In any event it would be interesting to note Chico's reaction to Comrade Ahrens' kidnaping."

Edward looked down at his blue cellaphose. It was the costume of the commune.

"I see," he said slowly.

THE reaction of Chico was unmistakably definite. The city was buzzing like a nest of angry hornets. Comrade Ahrens had been one of its ablest and most powerful members.

There was no trouble about the two wanderers. The guard lifted the Web-ray readily enough. The jester was known, treated with a species of kindly contempt. Edward, in the garb of a communist, passed easily in the general excitement. They entered at once into the ground floor of the city.

The commune was a single building, of ultra-cellophose stiffened by feralum girders, to permit the beneficial rays of the sun to penetrate every nook and cranny without dazzle. The great structure extended over five miles square and towered a full two hundred stories high.

Every unit of space and every activity was carefully planned. Ten stories deep into the bowels of the earth were the atomic disintegrators, the machines that swallowed handfuls of crushed rock and spewed forth resistless power. The first ten upward-thrusting floors were storehouses; then came the laboratories, synthetic factories, the sleeping quarters, administration centers, rest and recreation solariums; and, overtopping all, the incubators and schools.

For marriage was a eugenic institution; love had no part in mating. Nothing was left to chance in the communist city-state. The council decided how many new children were necessary to carry on effectively the work of the commune, and gave orders accordingly. They decided in advance of birth what niche in the scheme of things the prospective youngster was to fill, and varied the inheritance-changing rays. From birth to death everything was planned, regimented.

Because the city was in a turmoil of excitement, the pair were able to roam from floor to floor with unwonted freedom. Ray-messages crackled along all the airways—to Yorrick, to Pisbor, calling upon them for united efforts in the search for the missing captives, thereby breaking the isolation rule of centuries. Wild broadcasts to Redmask, too, threatening unutterable retributions if Ahrens were not forthwith released.

A carefully casual search of the city disclosed nothing. Stephen mopped his brow, looking thoughtful.

"It is certain they are not here," he said at length.

Edward stared his surprise. "Did you expect to find them in Chico?"

"I don't know." Stephen sighed. "Let us go back."

Once more they were in the Outlands, plunged in the great billowing forest, headed for the invisible ship. They were about a mile out from the city when the jester stopped his companion with a gripping arm.

"Sssh! Do you hear that?"

Edward strained his ears, heard nothing. Then, faintly, so faintly that it seemed only a murmur of the wind, came a thrumming, throbbing sound.

"Ships far off on the airways," he said.

"No. That sound doesn't come from the air. Listen again."

Edward inclined his head to cup every available vibration. "Why," he exclaimed, "it—it's in the ground!"

Stephen nodded. "Exactly!"

Edward went down on his hands and knees, placed his ear to the bare earth. "There must be another outlaw cavern below here." His face went grim. "Perhaps we have located Redmask."

"Perhaps," agreed the jester. "I've never heard of these quarters before."

The oligarch rose, gripped his conite disruptor. "How do we get to them?" he asked softly.

Stephen was already coursing over the ground. "It depends on whether this cavern follows the usual pattern."

An exposed root of an aged oak caught his attention. It was shaped like an S before it curved back into the soil.

"It does," he said joyfully. He tugged three times at the bellying middle; quick, sharp jerks. Nothing happened.

"Strange," he muttered. "I could have sworn—— Perhaps——"

He tugged again, varying the number of pulls. Still nothing. He rose, face clouded with disappointment. In so doing, his toe caught in the tough fiber and he sprawled headlong. Left hand still holding the precious violin, his right reached frantically out to cushion the fall. His fingers caught in the leathery vine that clung to a neighboring oak, jerked to hold him aloft.

Edward gave a sudden cry of alarm. Stephen pulled himself erect, turned to see a section of earth on the other side of the root sinking slowly. The oligarch, startled, was crouched to jump up to solid ground.

"Stay on!" yelled the jester, and made a flying leap into the deepening pit. "It was the vine," he said, peering into the darkness to see the smooth walls of an elevator shaft. "That's a new trick."

"Have you a weapon?" Edward whispered fiercely.

The jester hugged his violin case tight.

"No," he said. "That is why I come and go freely, unquestioned."

The platform, a steel square, and covered with a foot of earth and grass to conform to the ground above, came to a noiseless halt. The two men stepped into a dark chamber. As they did so, the platform, released of their weight, moved upward into position.

"How shall we ever get out?" asked the oligarch.

"We've plenty to do before that," Stephen told him grimly.

VERY cautiously they moved to the end of the chamber, feeling their way along. A passage way made a darker blob. It turned and twisted, then, ahead, shone a glimmer of light. The murmur of voices came muffled. They crawled forward, Edward panting slightly, clutching his disruptor. If only he could find her.

Stephen pulled him suddenly down. They were at the edge of a cave, artificial without doubt, but not as large as the one into which the oligarch had first been brought. The even glow of the radon illumination made a setting for a group of figures toward the farther wall.

The young oligarch made bitter clucking sounds, strained forward. The jester clamped him down hard with his free hand. "You fool!" he whispered harshly. "You'd be burned down before you moved two feet. Don't you think I knew what was down here?"

The proud oligarch took the epithet without resentment. He was only a very human, anguished lover now.

"But Janet," he implored. "If we don't do something——"

"Nothing will happen to your Janet, yet, but if you don't let me handle this my own way, none of us will ever see the sun again."

Edward sank back to the ground, veins cording in his neck against the instinct to rush the outlaws. Janet was seated at the farther end, back to the wall, bound. So, too, were Charles, her father; Gola, the Pisbor ambassador, and Comrade Ahrens. Facing them, backs to the watchers, were a dozen men, clad in outlaw green. The tall man, standing a little apart, swaying slightly on widespread legs, held dramatic attention.

"Redmask!" Edward breathed with sullen hate. There was no doubt as to who it was. The terrible, fear-inspiring penetron globe enshrouded his features. No one except a few trusted lieutenants had seen Redmask's face and lived.

A voice rose shrilly. It was Comrade Ahrens speaking.

"You must not kill us. We will do what you wish. Chico will back me up."

The man in the red globe sounded hollow and deep.

"You are not the only one. The others must follow suit. Either all agree—or all of you die."

There was terror in Gola's eyes, but he said sullenly: "I've told you before; I can promise nothing. The dictator cares little for me or any one else."

"You can communicate with him and find out. If not," ended the globed one ominously, "death will not be easy."

Gola snatched eagerly at the hope. "I will do that, surely. I'll write; I'll tell you what secrets of Pisbor I know."

Charles of the Marches sat straight and immovable. His quiet even tones cut across the cavern like an edged sword.

"If this business depends on unanimity, we may as well prepare now for death. I for one shall never consent to Redmask's damnable terms, nor would I permit Yorrick to carry them out, if agreed to." His voice grew stronger. It was the oligarch, with centuries of tradition behind him, unspoiled by the new deliberating luxury, who spoke.

"Your plan, Redmask, for an outlaw, is superlatively clever. It calls for practical continental domination on your part. Yorrick and Pisbor and Chico are to remove their guard defenses, and the secrets we have each closely held are to be exposed for your inspection. In such circumstances it would be only natural for you to become master within a month. Clever, but blind to certain defects.

"Carlos will not yield power because of Gola; Yorrick will not submit because two oligarchs might happen to die a bit sooner than their natural life span calls for. As for Chico," he glanced contemptuously at the bound communist, "I fail to understand what hold Comrade Ahrens has on an equal community of five million. It just won't wash, Redmask. You might as well free or kill us now."

Ahrens spluttered indignantly: "Speak for yourself, if you wish to die. As for me, I can give guarantees Chico will protect my life."

Stephen, prone and listening intently, muttered to himself: "I never expected Ahrens to turn coward."

Edward writhed in anguish. "For God's sake, let's do something! Janet will be killed."

"Not yet. I want to hear more."

The man in the red mask chuckled. "You needn't worry about the others. The dictator is an old man; he is set on having your daughter for wife." Edward ground his teeth in silent rage. "He will do a lot to marry an oligarch. He won't read between the lines as you did. As for Yorrick, I know that, if you wished it, the oligarchs would follow your lead. They have not your Spartan fortitude. Remember, Janet dies under torture if you refuse."

"I refuse." There was a finality to the simple words.

Redmask moved purposefully over to the bound girl. In his hand was a needle-ray that could burn fine, horrible criss-crossings over the body.

Janet screamed.

Edward of the Hudsons bounded to his feet and, roaring indistinguishable things, flung himself into the cavern. Stephen, caught unawares, jerked out a hand to stay him, missed.

"The fool!" he groaned.

The young oligarch had gone berserk. The conite disruptor pumped its deadly stream of contact pellets. Wherever one touched, the surrounding matter disintegrated into energy, leaving great gaping holes.

THE attack WAS a complete surprise. Men jumped to their feet, reached frantically for weapons. Even as they did so, man after man staggered, screamed, and broke in two, magical gaps where legs, arms, torsos should have been. The man in the red globe pivoted unsteadily around, groped blindly as if he could not see, threw himself flat on the ground.

But the surprise element was over. With half a dozen of their number dead, an outlaw flung himself to one side, jerked out a tiny parabolic reflector; pressed. A blue radiance hurled through the air, infolded the oligarch.

The disruptor dropped from his suddenly nerveless fingers; his whole body stiffened into stone. The survivors dived for him with roars of rage. Comrade Ahrens' voice rose high above the tumult.

"Don't kill!" he shrieked. "I agree to all terms."

The man in the red globe rose unsteadily to his feet, barked out a command. Sullenly the men held their rigid captive; lowered deadly weapons.

"Bind him. Bring him to me."

Stephen had snapped open his case, was fingering his priceless Stradivari us. Now he replaced it tenderly and closed the lid.

Arms bound behind him, the young oligarch was roughly propelled forward. He could not speak or move. The paralysis ray held him helpless.

Janet shrieked: "Edward!"

Charles strained at his bonds, his wonted hauteur gone.

"Edward of the Hudsons! How did you come here?"

Silence. The man in the globe swayed irresolutely.

Gola muttered: "Damned if he doesn't look like the worker on the Arethusa."

The red-masked one said. "Give him the anti-injection."

An outlaw produced a hypodermic, jabbed it into the bare arm. The flesh turned slowly warm.

"Yes, it is I," said Edward very calm and very quiet. The paralysis had left him.

The brow of the bound oligarch clouded. "You were disguised, Edward. You tried to cross my plans."

"Why not?" the young man burst out passionately. "You knew Janet and I loved each other."

"Father, we do! I don't want that horrible old man." The words tumbled from the girl.

The oligarch looked from one to the other. There was silence at his gathering wrath. It seemed forgotten he was bound, a prisoner.

"This will cost you dearly, Edward," he said tonelessly. "It was necessary for Janet to marry Carlos. Much depended on it. What mattered your little calf love! Oligarchs should rise superior to personal desires. I shall see to it that you are eliminated."

"Don't, father! Don't!" Janet screamed hysterically.

In a way, it was ludicrous. Yet for a moment no one thought of it that way. Then Ahrens giggled nervously. That broke the spell.

The tall man in the penetron globe said sarcastically "Don't order the elimination of others until your own disposition is decided on. Edward of the Hudsons, you come in good time. Unless you lend your voice to convince Charles and Yorrick, you will have the pleasure of watching your loved one suffer."

Edward flung himself against the restraining grip of his captors. "Let her alone, you scoundrel," he panted.

The red-masked one seemed not to hear. The needle point came up.

Stephen thought it was time for him to act. He got up, tucked his violin case under arm, and walked quite calmly into the cavern.

The outlaws whirled at this new interruption, weapons ready to burn the rash intruder down.

Ahrens cried out: "The jester!"

Others took up the name.

Stephen walked coolly on. "Of course the jester! Who else? Poor harmless jester, who is everybody's friend."

The man in the mask said angrily: "How the devil did you get in?"

The democrat raised his eyebrows in mock surprise.

"Why, by the front door. It was open."

"You fool! You've let yourself into a place from which there is no going out."

"Why not?" Stephen seemed astonished. "Everybody knows the jester; he is everybody's friend." His voice was singsong. "He wanders in city-states and in the Outlands; he knows the outlaws' lairs and says nothing. He is only a democrat, a man whose city is despised by all. He plays his ancient instrument wherever he goes; no one bothers him. He gives joy to those who understand and mirth to those who do not. See!"

He snapped open his case, took out his fiddle. Bow touched gut lightly.

"Stop it, you fool!" the masked man said angrily. "We've no time to waste on nonsense."

STEPHEN, however, had begun his song. The strains rippled through the great rocky cavern with the richness of old carpets from Isfahan. A strain from forgotten days when music was warm, glinting melody, pulsing under the touch of human fingers, not cerebral integrations of sound. The weaving, haunting, magical Waldweben from Siegfried.

A man came running out of a side chamber. His garb was the outlaw green, his face contorted. He jerked to a stop, saw the tall figure of the jester, heard the once-immortal melody. Terror snatched at his features.

"Stop him!" he cried hoarsely. "For God's sake stop him! He is the——"

"Yes, stop him. And that goes for all of you."

The new voice was ominously cold, unhuman. It came from the passageway.

Every one whirled. Stephen stopped, put his instrument carefully back into the case. Carlos, dictator of Pisbor, was in the chamber, seated in his chair of state, aloft on the shoulders of four men of Pisbor. His long claw-like fingers rested on rows of buttons. Behind him crowded his men, conite disruptors leveled.

"Drop all weapons!" came the mechanical voice. "Stay where you are."

There was nothing else to do but obey. The outlaws growled throatily as the falling metallic weapons made a clattering sound.

Gola cried out in hysterical delight, tinged with a film of fear: "Master!"

Charles said quietly: "You come in good time."

Carlos let his cold eyes wander over the scene. His time-withered countenance was impassive. He made no gesture to release the bound captives. The mechanical voice grated metallically.

"We all seem to be here; every one. Three oligarchs from Yorrick, esteemed most highly by their city. Gola of Pisbor, of most inconsiderable worth to me." The poor ambassador cringed in his bonds; somehow he had failed in the dictator's eyes.

"Then we have with us Comrade Ahrens," continued Carlos with tapping fingers. "He is rumored to be the prime mover in a city of equality." The communist met impassivity with easy calmness. His features betrayed nothing.

"Not to speak of the jester," the strangely alert eyes strayed over him thoughtfully. "Curious; I must consider him later. For there are also a stray scum of outlaws, and"—all twisted heads to the man in the red globe—"there is Redmask. A very dangerous outlaw, I was given to understand. I am interested in him and his silly mask. Of penetron, I believe?"

The red globe nodded without speech. The voice grated on without expression: "My secret; the secret of Pisbor. Take it off, that I may see what slave of mine set up to be the bad man of the Outlands."

The man shrank unsteadily away from the sound of the voice.

"Take it off, I say."

The outlaw who had cried out at the sight of Stephen now raised his voice eagerly.

"I have information for you, Carlos. Spare my life and give me fitting reward, and it is yours."

Stephen turned slowly, saw for the first time the face of the recreant outlaw. Hard lines ridged themselves on his forehead. Clutching his violin tight, he poised on balanced feet for instant action.

"I make no conditions with any one," came from the dictator. "You shall give your information without terms."

"But my life at least," said the man despairingly.

"No terms," repeated the inexorable voice.

"I throw myself on your mercy!" cried the wretch. "I shall tell." His eye swung fleetingly around the groups. "That man——" His hand raised to point an accusing finger.

Stephen raised himself on the balls of his feet, ready for the last mad dash. But the accusation was never made, the gesture never completed. A green flash streaked across the cavern, an infinitesimal moment ahead of a puffed report. The outlaw gave a shrill scream; his body seemed to explode. Bits of flesh rained bodily through the cavern.

The jester exhaled slowly, settled back on his firm feet. His life had been saved by a miracle.

There was turmoil in the cavern, much shouting and seeking. The unhuman sounds of the dictator cut sharply across it: "Who killed that man?"

Silence. Then:

"I did," said Comrade Ahrens very calmly.

He twisted his bound hands; a Dongan projector appeared from under his blue shirt. The rounded nose pointed wickedly at the chaired figure of the dictator. Cries of alarm, weapons thrust up to cover the communist.

"No good," he declared contemptuously. "My finger lacks the tiniest pressure on the trigger. Shoot, and the finger contracts."

"Don't shoot," said the dictator. The seamed face twitched convulsively, the fingers trembled as they clicked out the voice.

Ahrens threw his head back and laughed. Then, surprisingly, he dropped the Dongan projector on the ground.

"It has no more shells."

Red color Hooded Carlos—shame and rage equally mingled.

"You shall pay dearly for this," the mechanical voice droned.

"Perhaps," returned the communist indifferently, his eyes far away in thought.

Stephen and the outlaw chief had both been forgotten. Now it was Charles of the Marches who interrupted.

"Don't you think, Carlos," he inquired acidly, "it is time for you to release Janet and myself from these bonds? It is true the discussion is most interesting, but we'd much prefer to listen to it with untrammeled limbs."

THE dictator looked at Charles with speculative eyes, swung to Janet's fear-stricken body with a quickened glint. Edward, hitherto sullen and silent, strained against his bonds. The jester glanced swiftly at his time-signal, frowned, strained his ears to cup the tiniest sound, frowned more deeply, edged toward the passageway.

"No, Charles," said Carlos, "it is not yet time. You see, conditions have changed a bit. I had not intended in any event going through with the compact as stated. Once you and Janet were in Pisbor, you would not have gotten out without new terms."

The oligarch spoke quietly: "I anticipated that possibility. That was why I brought the battle fleet along."

"The fleet did not enter."

"Then the Arethusa would have remained outside also."

The dictator nodded his head in admiration. "You are clever, Charles, cleverer than young hotheaded Edward who stuck the Arethusa into the trap. I begin to feel that Redmask did me a service by kidnaping you. As it is, I have the Arethusa and its very valuable cargo—radium is the one thing we lack and cannot make synthetically. I have Janet just the same, and I have you without strings or disgusting talk of broken faith.

"You see, Charles, Yorrick declared war on me when I refused to let the Arethusa out. A scout plane of mine, spying on Chico, saw Redmask's ship materialize, and notified me. Now I shall dictate terms to all of you. First, Edward of the Hudsons must die. I am certain he attempts to rival me in the affections of dear Janet, and that is not permitted. Amu!"

A Pisbor man stepped forward.

"Shoot him."

The conite disruptor whipped up.

Janet shrilled: "Let him live, Carlos. I'll do anything—anything," Her voice trailed, and she sagged against her bonds. She had fainted. Edward stared proudly at onrushing death, eyes unafraid.

Stephen strained his ears, heard something, a faint, far-off sound. Too late, he reflected bitterly. Edward would die. He must do something. Acting suddenly, he let out a great shout, spun on his heels, and dived for the passageway.

Amu's finger hung nervelessly on the trigger. He whirled to see what had happened.

"Stop the jester," said the dictator. "He must not escape."

Disruptors whipped red flashes across the cavern, dematerializing huge segments of rock. Stephen zigzagged as he ran. One touch of a flash, no matter how glancing, meant instant death. Feet pounded after him; the aim of the startled guards was improving. He made the passageway, darted along. He would never get out unaided. He could hear the swift rush behind; whole sections of wall disintegrated in front, to one side, behind.

Another sound came to him, the noise of more pounding feet. Was he trapped or was it——

He ran recklessly on. He would see soon enough. At the last bend before the lift-platform a swarm of men eddied round the curve. Men in the outlaw green, men with weapons thrusting forward. A shout sprang up from them at the sight of the jester.

Stephen gasped convulsively: "Men of Pisbor; kill them. Seize those in cavern—alive."

Their leader, a blue-nosed individual, nodded, and a surge of men eager for battle carried them around the jester in the twinkling of an eye. The last of the rushing men thrust something in the democrat's free hand.

He leaned weakly against the cold rock, quieting down laborious pantings. Behind him there was the noise of sudden shock, of fierce shouts and screaming agony, of the hurtling press of men in deadly conflict. The passage filled with acrid fumes, with blinding sooty flashes, with the terrible dust of disintegration.

Stephen went swiftly into the platform chamber, hid his violin in a wall niche, made certain adjustments.

A TALL man, broad-shouldered, stepped quietly into the great cavern. His head was completely inclosed in a blood-red globe; his step was sure-footed and certain. Within, the invaders were in complete control. Men of Pisbor, men in outlaw green, lay sprawled over the smooth rock floor, never to move again. Weapons of the fifty-fifth century never wounded—contact always meant death.

The dictator had been unceremoniously jerked out of his chair. He lay dumbly mouthing on the ground. His ancient face was a twisted mask of rage and fear. The survivors of Pisbor were herded to one side, the first group of men in outlaw green sullenly to the other. The bound captives were still in their bonds, overwhelmed with the varying changes of fortune that seemed to sink them each time deeper into hopelessness.

A sudden silence greeted the appearance of the orbed figure. Then an ear-splitting shout of triumph from the massed invaders rang through the vault.

"Redmask!"

The dread name was caught up by the walls, rebounded and reechoed like rolling thunder. The figure nodded in acknowledgment, strode forward.

A simultaneous gasp issued from the captives' throats, a moan of terror from the beaten outlaws. A figure staggered in, tried to shrink from sight.

Edward gulped, his eyes moving unbelievingly from figure to figure. Alike as two peas—two tall men clad in outlaw green, two globes of blood-red hue masking the features beneath.

Two Redmasks!

"For God's sake, which is which?" cried Charles, icy calm forgotten.

Gola stared and said nothing; Ahrens was mute.

Redmask spoke "Take off your helmet, impostor." His voice was hollow, bass.

The psuedo Redmask lifted trembling fingers, worked at the fastenings. The globe lifted, fell crashing to the floor. Revealed in the midst of his fellows stood a dark-browed man, blinking against the sudden light, features writ large with approaching doom.

Redmask stared quietly at him; his red orb terrifyingly impersonal.

"Do not fear," he said contemptuously. "You will not be harmed. You were only a tool." He turned to the man's fellows, the pseudo-outlaws. "Nor will you others."

The wretches burst into eager clattering of thanks. The impostor cried out: "I'll tell everything."

"You don't have to," Redmask remarked coldly. "I know everything. Charles of the Marches, I knew your plans. A case of overweening ambition. To join Yorrick and Pisbor together you would have sacrificed your daughter. You were certain you would be able, once united, to wrest control from Carlos."

Charles looked steadily at the dread figure.

"Your analysis is correct," he admitted.

Redmask turned from him with a gesture of annoyance.

"You, Gola," he stated, "are small fry, yet even you intrigued. You hated Carlos, your master, and aspired some day to overthrow him. You feared the proposed marriage, because alliance with Yorrick would have made your plans impossible."

Gola cowered in his bonds, making unintelligible noises. Redmask turned to the dumb dictator.

"The all-powerful Carlos seems but a poor thing without his chair. No voice, no strength; helpless like a snail parted from its shell. Your schemes were twisted, tortuous, like your ancientness. I am certain you boasted of them in your little moment of triumph."

Redmask swung from him. His voice gathered sweetness.

"Unbind Edward of the Hudsons and Janet of the Marches."

Outlaws sprang to do his bidding. Unhindered, Edward went to the terrified girl, put his arm protectingly around her.

"What will you do with us?" he demanded in challenging tones.

Redmask chuckled. It sounded hollow in the globe.

"A good deal. First, I shall ensure your marriage. Charles of the Marches will have to agree. That is the first of my conditions."

The oligarch bowed his head. "After what has happened, I consent to that. I say nothing of other conditions."

EDWARD gulped in unbelieving wonder. His arms tightened around the girl. "Redmask," he said, "outlaw, outlander, thief, murderer, whatever you may be, know that you have gained a friend in Edward of the Hudsons."

Redmask chuckled again. "It is an honor." He turned to Comrade Ahrens, and a shadow seemed to fall over the shadowless light. His voice was grave, low-pitched now.

"You know what I have to say?" The communist raised his head firmly. "I know. Human or devil, I know not which, somehow you have achieved the truth."

"Yes. It was you who planned everything. You feared the approaching marriage of state between Janet and Carlos. You knew it spelled trouble for your city of Chico. The balance of power was about to be destroyed. The combination inevitably must attack Chico, seek suzerainty over the continent. You decided to forestall it. You planned exceedingly well. You arranged this cavern, dressed your men in outlaw costumes, fashioned a penetron mask for your man to impersonate me. It would be easy to throw complete blame on me. You managed to steal even the idea of the invisibility magnets from me. One of my trusted assistants was your spy. Where is he?"

Comrade Ahrens pointed to blobs of flesh spattered over the rock. "He tried to betray me, too, a while ago."

Redmask smiled quietly in the secrecy of his globe.

"I thought as much. Now tell me the rest. What did you intend doing with your captives?"

"I took a leaf out of the thoughts of these others. Chico never held plans of conquest, but what I learned made me decide to act quickly. It was a case of striking first or being overwhelmed. With these as hostages I hoped to compel Pisbor and Yorrick to remove their defensive walls, or, at least, to learn their secrets from my prisoners. Chico through me was to pretend to do likewise." He spoke with sudden earnestness. "Remember, this was my individual scheme. Chico knows nothing of all this."

Redmask nodded. "I believe you." He faced them all, voice suddenly stern: "Now I am laying my conditions down to you. On their fulfillment depends your lives. From you, Ahrens, I wish the return of the invisibility magnets, the penetron mask you fashioned, without, however, the uniway transparence that provides for sight."

The communist nodded his head in weary assent.

"From you, Carlos, the radium shipment of the Arethusa. From all of you——" There was a stir of listening. Charles set his teeth obstinately—"from all of you; that is, from Yorrick, from Pisbor, from Chico, food pellets enough to feed five million for five years. The outlands are short of supplies."

"That is a large order," said Charles slowly, "but—what else?"

"Nothing! Upon delivery to the points I indicate, all of you are free, free even to resume plotting against each other."

Incredulity lighted up their faces.

"You mean——" began Charles.

"What I said," Redmask bit his words off sharply.

There was a rippling murmur of relief. The writhing dictator's toothless gums stopped mumbling.

"Of course we accept," said Charles as spokesman. "And I want to tell you——"