RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

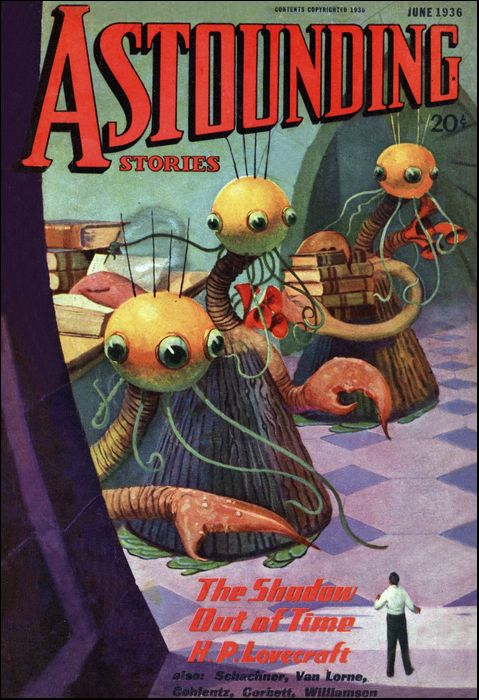

Astounding Stories, June 1936, with "Reverse Universe"

They were resting on the surface of a fantastic, unbelievable world. Surface? Rather the concavity of the inside of a shell, stretching slowly upward—

THE huge space ship was traveling fast—faster than space ships had ever traveled before—so fast its speed approximated the limiting velocity of light. Yet to the crew immured within its metal hull there was no sense of motion, no sense of anything but a fixed, immutable suspension in a void that had neither form nor meaning.

For the thousandth time Richard Talbot, first officer of the Pathfinder, peered through the view ports in the quartz-inclosed conning tower. For the thousandth time the monotonous, death-quiescent universe stared back at him, mocking these puny mortals who in their swollen pride had sought to penetrate her close-held secrets. Space, black with a blackness unknown to Earth, enshrouded them in palpable embrace. Against a far-flung back drop, equidistant whichever way he turned, were the stars, millions of them—frozen, diameterless points of light, shedding no luminance, unshimmering, remote.

The spider line on the forward port bisected a slightly larger star, a trifle greater than its myriad fellows; the spider line on the after port held with unwavering intensity on a faint, somewhat inconspicuous glimmer of reddish light. At least, thought Talbot with a little shiver, their course was straight. For the little gleam behind was the Sun, from whence they had come, and the white glow ahead was Alpha Centauri, their destination.

He stole a look at the other man in the tower. Captain John Apperson amazed him, now as always. He stood there, legs wide to sustain his powerful, thickset body, hands clasped behind his back, staring with fixed rigidity through the forward port. Never once had Dick Talbot seen him deviate from this position; never once had he turned his craggy head with its great shock of iron-gray hair and grayer beard to the right or to the left; never once had he deigned to seek with questing, homesick eyes the dim, faint star they had quitted years before.

He was unhuman, thought Talbot, with a queer mixture of admiration and adumbrating repulsion. He was not a normal man with normal longings and hesitations. He was incredible, a piece with the incredible universe in which they seemed a moveless entity. He was dressed as always in the carefully spick-and-span, bright-blue uniform of a captain of the solar spaceways.

The crew had long since abandoned all attempts at spruceness and neatness. They slouched around in dungarees, performed their simple tasks with unstrung lassitude, forgetful of personal cleanliness and unshaven beards, spending their interminable leisure in endless sleep or muttered conversation. Earth and all the other planets, of course, were invisible, had been invisible since the first desperate taking off from icebound, uninhabited Pluto.

Talbot cleared his throat noisily. The captain did not seem to hear. All his life was concentrated in his eyes, in the fanatical gaze he fixed on the tantalizing star ahead, the ever-beckoning, ever-remote Alpha Centauri. Sometimes the first officer thought privately that Captain Apperson had gone mad with the dreadful space madness that occasionally afflicted green hands even on the comparatively short interplanetary hops.

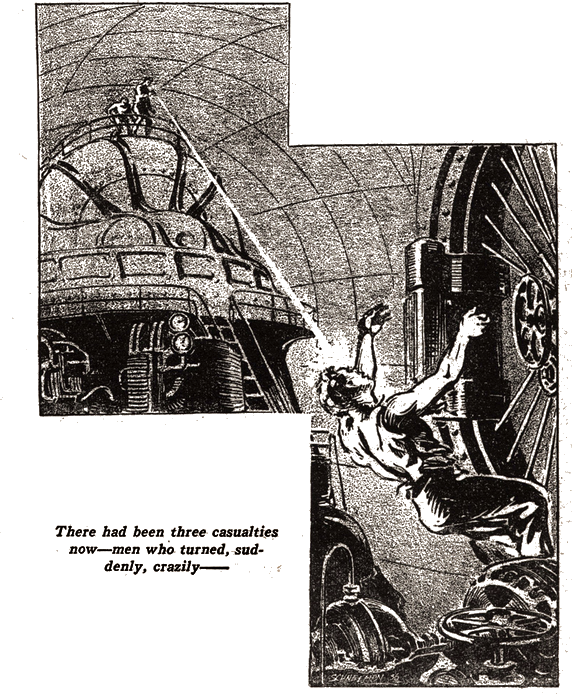

There had already been three casualties among the crew—men who had suddenly turned on their fellows screaming and amuck—one in fact had almost opened the air locks before he had been detected and killed. The three bodies, sewn in canvas shrouds, were now solitary bits of flotsam far behind in the unimaginable reaches of space.

TALBOT cleared his throat again. He touched fingers to his cap. He was a bit resentful of that. It was the first time in all his ships that a commander had insisted on that meaningless routine of discipline from his first officer in the privacy of the conning tower. Captain Apperson was notorious for his iron-bound, martinet discipline. That was the reason the Spaceways Exploration Council had chosen him for this tremendous flight into the unknown.

"I wish to report, sir," Dick Talbot said formally, "that the daily inspection shows all equipment to be shipshape, the instruments in perfect order, and the course undeviating."

"Very good, mister," Captain Apperson growled without turning his head. It was an implied invitation to retire. But Talbot held his ground, his lean young jaw firm, his gray eyes snapping.

"The mechanical equipment is all right, sir," he emphasized, "but I'd like to talk to you about the crew. They are——"

Apperson's eyes were still fanatically engrossed on that far-off goal, but his voice was icy in its interruption. "I believe I placed Second Officer Solon Fithian in charge of personnel," he said deliberately. "Any reports concerning the crew must emanate from him." Damned old martinet! Talbot raged to himself, but kept his voice calm. "I'm sorry, sir," he insisted, "but Mr. Fithian does not seem to notice. There's trouble brewing. The crew is scared, space sick, homesick if you wish. They feel that if we continued, not a one will return alive. They resent, too, the harsh disposition of their comrades who went mad. I've heard snatches of talk, felt the sullenness of their looks, seen muttering groups break up as I approach.

I'm afraid, sir——"

Now the captain wheeled. His eyes were a cold blue, icy as the waters from newly melted glaciers. "Mutiny is the word you wish to imply, isn't it, mister?"

Talbot met his withering glance with level gaze. "Yes, sir," he agreed. "Unless something is done at once to remedy conditions, such as——"

The old captain's face turned a beet-red. His gnarled hands clenched and his voice was thick with passion. "You forget yourself, mister," he roared. "Your job is navigation, and mine is to run this ship. I intend doing it without any suggestions from you or any one else. Do you understand?"

Talbot flushed under his space tan. "I understand," he said steadily. "You are the captain and in command. But no captain in all the spaceway has ever spoken to men like that and gotten away with it. You'll listen to me and like it, sir, even though you put me in irons afterward, or cast me out through an air lock as you did those poor fellows your vaunted discipline drove to madness. Let me tell you——"

APPERSON'S finger was stabbing a button on the controls. His face was apoplectic. The slide door opened softly behind Talbot, and a smooth, silky voice thrust its even thread across the raging torrent of the young first officer's anger.

"Your orders, Captain Apperson?"

Talbot whirled to face a slight, dark man with delicate, womanish features and eyes that had a queer habit of staring through their objective with unfocused lenses.

"Mr. Fithian," Apperson growled abruptly. "I have received reports of grave unrest among the crew. Mutiny"—he laughed harshly—"was, I believe, the word used. You're the personnel officer, mister. What have you to say?"

Solon Fithian gaped in startled fashion. His unfocused eyes roamed stealthily past Talbot, fixed on the spider line bisecting the white glow that was Alpha Centauri. "Why," he declared in his soft, shocked voice, "it's impossible, sir. The crew is quite contented and obedient, sir. I haven't had the slightest trouble. But who"—he broke off and again his glance slid past them—"could have brought you such a tale?"

"The first officer," Apperson rumbled, "your superior in command."

The knuckles on Talbot's hands were white, but he held himself under control. "It is a tale, Fithian," he stated sharply, "that it is surprising you know nothing about."

The second officer's left hand was behind his back, but Talbot, in the rush of his scorn, did not notice. Only later did he remember that surreptitious gesture.

"In fact," Talbot continued, "I called the condition to your attention before this, and you promised to investigate. The crew is on the verge of mutiny, yet you pretend to Captain Apperson there is nothing wrong."

Fithian laughed, shrill and high and womanish. He seemed to double up with laughter; he went off in uncontrollable spasms that filled the conning tower with beating waves of sound. "Stop it, mister!" the old captain thundered. "What do you mean by this unseemingly cackling in my presence?"

The second officer straightened up, eyes gliding past Talbot with a curious absence of mirth; then he doubled up again with shrieks of wild laughter. "I—I'm sorry, sir, but I—I can't help it. Mutiny—that is funny, sir. Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha-ah!"

Apperson stepped forward, gripped him by the shoulder, and shook him violently. "Have all my officers gone crazy?" he snapped. "Stop it, mister, or I'll clap you both in irons, and run the ship myself."

The quartz-inclosed space was a welter of rolling echoes, loud voices and still-screeching laughter. Thus it was that Talbot did not hear the approach of stealthy feet along the inner catwalk until it was too late.

They came on with a rush, filling the tiny conning tower with their hulking, unwashed bodies. Flame projectors snouted in their grubby fingers—weapons that should have been under seal in the arms compartment—and hatred glared from their half-mad eyes.

Talbot's hand darted down toward his belt where his needle ray dangled, stopped with a jerk. A half dozen projectors were trained on him, ready to blast him out of existence.

"That's better," snarled the leader, a big, shaggy fellow with tawny beard and twisted nose. "Now get over there, all of you, away from the control board. One peep or move out of any of you, and you'll get a bellyful, see!"

THE First Officer backed obediently away. No sense in committing suicide. But his lithe frame flexed imperceptibly, seeking an opening.

Captain Apperson did not stir. "What is the meaning of this?" he demanded in a terrible voice. "Get back to your posts, every man of you, before I put you all in irons for the rest of the voyage."

"It is mutiny, my dear captain," a silken voice purred. "Just as the faithful Talbot had tried to report to you, and you in your stupidity would not believe." Fithian moved forward like a cat, a sneer on his small, dark countenance. "You've given orders long enough, Apperson," he said. "From now on it's my turn."

Captain Apperson turned and stared at his erstwhile subordinate for a full minute. There was contempt, biting scorn in his stare; then he turned away silently, his gesture unmistakable.

Fithian started, and his dark face flamed. Venomous hatred glowed in his eyes. "You've sealed your own fate, Apperson," he whipped out. "I was going to give you a chance, but now—— All that we wanted was your consent to turn back. This trip of ours is pure suicide. Two years we've been gone, and there are more than two years to go. The men are going mad, one by one, and you've done nothing to stop it. You and your lousy discipline!"

"That's right," shouted the leader of the mutineers. He was Marl Horgan, tender of the forward jets. "You treat us like dirt, like scum on the surface of Venus. We're men and we've got rights. We ain't going any farther. There's just enough fuel now to turn around and get back to the solar system."

The old captain looked at him as if from an Olympian height. "Fool!" he said deliberately, "the lethal chamber awaits every man of you, back on Earth. You know the penalty for mutiny."

Horgan grinned. "It ain't gonna be mutiny," he declared meaningly. "Just one of those unfortunate times when the captain ups and dies, and the other officers naturally decide to give up and turn back. We'll all be wearing deep mourning for our beloved captain; won't we, mates?"

There was a delighted roar of mirth from the crowding crew. Fithian smiled a secretive smile.

Apperson surveyed them calmly. He straightened up, brushed off his immaculate uniform with a steady hand, buttoned the top button precisely. The waves of hatred that beat upon him left him unperturbed; he had only the consciousness of duties well and properly performed.

"If you think," he said, "that I'm going to beg for my life, you're damned mistaken. Get it over with."

The flame projectors moved upward. He faced them unafraid. Talbot let his hand drop stealthily. One swift tug at his belt and——

"No you don't," Horgan growled. "One move like that and you join the captain."

"You have to get rid of him, too, men," Fithian said.

THE members of the crew looked at each other uneasily. Horgan's seamed forehead was heavy with unaccustomed trouble. Talbot had been rather popular with the men.

"There ain't really any call for that, is there, Mr. Fithian?" Horgan asked almost pleadingly. "Air. Talbot's been pretty white to us fellows. We'd sort of hate to blast him out."

The crew growled assent. They were ordinary men, driven to cruelty by harsh, unyielding discipline, and a touch of space madness.

Fithian's face was sallow with fear. "Don't you understand?" he cried vehemently. "Talbot alive means the lethal chamber for all of you back on Earth."

Horgan frowned heavily. "We got no grudge against you, Mr. Talbot," he said. "Give us your word of honor you won't blab on us, and we'll let you be."

"Of course he'll talk," Fithian shouted hysterically, "no matter what he tells you now."

"We can trust his word," Horgan retorted confidently. "Can we, mates?"

"Sure can," they flung back.

Talbot looked at them with a wry smile. "Thanks for your faith in my given word," he answered quietly. "It is not misplaced. That is why I can make no such promise. Furthermore, Captain Apperson is our commander. He is an honest, efficient captain. Whatever errors he may have committed were not out of malice toward you men; they were for what he conceived to be the best interest of the ship. I am therefore compelled to share his fate, whatever it may be."

There was a hasty consultation after that. From where they stood, under vigilant guard, Talbot could hear the excited murmur of voices, shot through with Fithian's treble and Horgan's angry bass. Their fate depended on that babble of argument.

Horgan coughed hastily. "It's this way, Mr. Talbot," he addressed himself to the first officer, ignoring Apperson. "You make it pretty hard for us."

"Omit the flowers and get on with it, Horgan," Talbot said quietly.

"We decided," the rocket tender plunged, "to put you both off in the space boat. There are enough provisions stowed on board for both of you for six months, or thereabouts; and there's enough fuel in the rocket tubes at least for a landing."

Talbot looked him squarely in the eye. "You know what that means, Horgan: Eventual drifting to death in interstellar space. There's no possible place in the universe we could reach with that supply of fuel and food."

The rocket tender avoided his gaze, shuffled his feet uneasily. "It's the best we can do—that or shoving you out into space without a suit."

"That would be quicker," Talbot retorted.

"We'll take the space boat," Captain Apperson interrupted. It had been the first time he had spoken since the irruption of the mutineers. Talbot looked at his commander in astonishment. Had the man gone mad—or chicken-hearted? Surely quick, merciful death was preferable to the horrors of slow, tortured agony in the illimitable wastes. But Apperson's bearded features were as stony as ever.

TALBOT watched the red jets of fire pierce the black curtain of space like lancing swords. It was spectacular; it was breathtaking in its dazzling effects, but he was not given to aesthetic appreciations at that particular moment.

Slowly, the dull, almost invisible hull of the great space cruiser turned under the repeated blasts of the rocket jets. Space was a fan of brilliant flames. The tremendous maneuver required a hundred million miles of turning area and almost all the reserves of fuel to swing the Pathfinder on its long, backward trek to the outpost on Pluto.

Suddenly the huge cruiser was gone, swallowed up in the vast emptiness of the universe. The two men were alone now; alone as no one had ever been since the beginning of time. Encased in a tiny space boat, built for emergency use in the comparatively crowded lanes and short hops of the solar system, abandoned in an amplitude of infinite space time, trillions of miles from the nearest star.

Talbot turned his face from the rear port in despair. It was now almost a half hour since the prison boat had been cast off from the magnetic plates of the parent cruiser. Up to the end he had hoped against hope that Horgan and the crew might relent, that they still might swing back to pick them up.

Of Fithian he had expected no such yielding. But there had been a certain hunted fear, a sympathy in the eyes of some of the men that might possibly have flared into action before the thing was done irrevocably.

Now, he realized dully, that last futile hope was gone. The great ship had faded from view, was even now fifty million miles away, speeding back to Earth with a plausible story concocted in the brain of Solon Fithian.

Earth! Home! Talbot felt a lump in his throat as his eyes burned on that faint, inconspicuous prickle of light, almost lost among its innumerable fellows. He thought of green fields and swarming cities, blessedly soothing to the sight after the monotonous glare of space. He thought of the men of the spaceways, brave, warm-hearted, loyal, whose hands had clasped his in greeting in every port of the solar system.

He would never see them again—not one of them. Better to open the air locks and die now. It would not be pretty. Space suicide was a torture of choking lungs and bursting tissues, but it was over in a few minutes. He swung around to his fellow victim. Now that he thought of it, he had not heard a word from Apperson since they had both been hurriedly thrust into the cramped quarters of their prison ship.

The captain turned almost simultaneously with him. No emotion showed on his stern, bearded face. His uniform was still neatly buttoned, his bearing erect.

"You will be good enough to get our bearings, mister," he said in precise, expressionless tones.

"Yes, sir," Talbot said briefly.

Some fifteen minutes later he lifted his head from the scribbled calculations before him. Apperson had stationed himself before the forward port, legs solidly spraddled, hands clasped behind his back, eyes glued in silence on the spider line that bisected the arrow of their flight.

"We are," observed Talbot, "almost equidistant between the Sun and Alpha Centauri—about twelve and a half trillion miles either way. Our present rate of speed is 158,000 miles per second, approximately that of the Pathfinder before the mutineers cast us off. Our directional angle is some twenty-three degrees minus on Plane A from Alpha Centauri. But what of it, captain? It doesn't matter at all where we are. We're hopelessly, irretrievably lost."

APPERSON did not turn from his strange vigil. "You will please confine yourself, mister, to furnishing such information as I require," he snapped. "Be good enough to fire the right-hand rocket tubes until our course is true on Alpha Centauri." He hesitated perceptibly, then proceeded calmly. "Mister, then you are to fire all rocket tubes continuously to achieve maximum acceleration."

Talbot sprang to his feet. Good Heaven, the man was mad! Something had snapped in that martinet brain at the imminence of death.

"Do you realize," he demanded, "that even at the limiting speed of light, we'd reach Alpha Centauri about two and a quarter years from now? We have provisions on hand for only six months—not to speak of the fact that the air-renewing apparatus on these space boats works properly for a period considerably less even than that.

"Furthermore, our present speed is the maximum obtainable. From this point on the inertial lag of increased mass builds up rapidly and more than compensates for the forward thrust of the rockets. And granting even the impossible—that somehow we reach Alpha Centauri alive—our fuel reserves would have been exhausted and we'd have no means of navigating to a landing on any problematic planet that may revolve around it.

"No," he continued more calmly, "my advice as man to man—we are no longer superior and subordinate, mind you—is either to open the air locks and get it over with, or swing back to the solar system on the remote chance that some expedition has set out to follow in our tracks."

Captain Apperson swung around. His face was contorted with suffering, his eyes blazed with the fixity of monomania.

"Give up the voyage!" he mouthed hoarsely. "Never! Not once in all my long career have I ever abandoned a course once set; not once have I failed to bring my ship through. I promised the council I'd get to Alpha Centauri, and by the eternal truths of the universe, I intend to do just that!" He pounded with knotted fist on the metal stanchions. "Dead or alive, crash or no, this ship to which I have transferred my command lands on Alpha Centauri—do you understand that, mister?"

Talbot stared at him a moment. It was the broad, uniformed back of the captain that held his gaze. For Apperson had pivoted again to his rapt immersion on that far-off sun, still only a point of light in the universe.

The man was mad, of course. Talbot could see that quite cleanly. It would have been a comparatively easy matter to spring on him now, and tie him to innocuousness. But a thrill coursed through the young first officer. It was a madness so exalted, so intent on its ultimate goal, so imbued with passion and driving force and heedlessness of obstacles that it partook of a nobility akin to the gods themselves.

For the first time he understood Apperson. A lonely old man, cut off from his fellow officers by his fanatical devotion to what he conceived his duty, hiding his loneliness by a fiercer attention to details and the minutiae of discipline, hugging to his bosom with mad, secret pride the reputation he had achieved until it had become an overwhelming obsession.

The mutiny must have been a terrible blow to the old man's innermost being. Only one thing could salve that wound: getting to Alpha Centauri! Even in death, a wasted, rotting corpse within the hurtling tomb of the space boat, somehow he would know that he had reached; and knowing, the suffering spirit that was his would be laid to rest.

"I understand," Talbot said very softly. Without another word he moved to the control board. The rockets filled the chamber with their subdued roaring. Slowly the spider line on the forward port shifted over the stars of the universe, held fixed and immovable on the brighter speck. Their course was set on Alpha Centauri!

That was simple navigation. The next step was another matter. With a shrug of his shoulders Talbot fired rear and side rockets, forced every ounce of fuel into the sheathed tubes to build up immense acceleration. The little ship quivered and jerked under the terrific impacts. The strain on metal plates and welded seams rose far beyond the calculated safety limits. The noise was unendurable.

THE velocimeter moved slowly over the dial. One hundred and fifty-nine thousand, one sixty, one sixty-one, one hundred and sixty-two thousand miles per second. And there it held, in spite of the reckless pumping of fuel, in spite of Talbot's utmost skill in navigation. Lorentz's theorem held good! At extremely high velocities the inertial mass approaches the infinite so rapidly that not all the thrusting power in the world can compensate for it. And Talbot knew it.

Somberly he turned to Apperson. "You see," he said, "the thing is impossible. We cannot fight the laws of nature."

"Nature be damned!" the old man barked. "Feed more fuel into the tubes. We must break through the speed of light if—if——" For the first time he faltered, felt the slow paralysis of doubt.

"If we are to make Alpha Centauri before we die," Talbot gently completed the sentence for him. He saluted with formal gesture. "I beg to report, sir, that the fuel tanks are dry."

They were still driving ahead at constant speed. Newton's First Law of Motion took care of that. In the tremendous emptiness of interstellar space the gravitational forces of the universe are extremely feeble and tend to balance themselves to a state of equilibrium. Allowing, as Talbot had done, for the proper motion of the star toward which they were heading, they would reach their objective. But they would reach it in not less than two years—a year and a half too late!

Captain Apperson was suddenly old and shrunken. All his life he had been a practical navigator, with the practical man's fine scorn of the theoretical scientists. Mathematics, abstruse reasoning, he left to his first officers. That was their business; his was to run a ship, to enforce iron discipline.

He had heard, of course, of the limiting velocity of light, but it meant nothing to him. It had never been tried out in practice. The interplanetary lanes did not readily lend themselves to such enormous speeds. "Give me a clear road and plenty of fuel," he had always argued, "and I'll build you up speed of half a million, a million miles a second if necessary. What's there to stop it?"

Now, for the first time, he was face to face with the reality. And it had let him down. A cherished illusion that he had hugged to himself during years of space travel had exploded. He was frightened. Were all the other iron laws of his being but similar illusions? He shrank from that, affrighted.

Then he straightened. Very slowly, very methodically, he brushed his immaculate uniform. At least one illusion must be preserved. Let the universe itself know that one thing at least within its confines was invariant. Captain John Apperson always reached his goal. What matter if physically he were dead; somewhere, far off or near, his spirit would know! Once more he was the autocrat of the spaceways, listening to his subordinate's report.

"Very good, mister, he replied with rigid formality. "Keep her to her course."

Talbot felt suddenly very tender to this lonely old man. He had sensed the terrific struggle in that uniformed bosom. Death meant nothing in the face of such an indomitable spirit. He saluted again. "Yes, sir."

THEY did not speak much after that these two, but a sense of kinship held them close. Days on weary days of Earth time passed and fled. Time held no further meaning, nor did space. They were a seemingly moveless ball suspended in the infinite void. The glittering back drop of stars mocked at them and showed no change.

Talbot checked over their supplies. They placed themselves on ironclad rations of food and drink. Even so they could not survive over six months. He tested the air renewal machinery, tightened leaks, gained maximum efficiency. Perhaps that too would carry on for a similar period. And all the time Apperson held to his eternal vigil at the forward port, seeking ever with hot, devouring eyes that infinitely remote point of light that had become a challenge to death itself, to the very meaning of the universe.

The days grew into weeks, the weeks into months. The velocimeter showed even speed—one hundred and sixty-two thousand miles per second. The pointer seemed frozen in its place. Yet here, in the frightened reaches of space, it was the quiescence of death—not even the slowest crawl of a worm on that far-off, tiny planet they had almost forgotten——

Talbot sat on his accustomed chair. They had just finished their very simple meal of condensed pellets. They were constantly hungry now, but that did not matter. Apperson was at his interminable watch at the forward port. Talbot stared back at the place where the Sun should be. It was impossible to see it any more.

He sat and stared at the blur of stars. His clean, chiseled features were lined now and a bit haggard. It was not easy to do this day after day, knowing too well the inevitable end. If it had not been for the old captain—— He took a deep breath, forgetting for the moment the shallow breathing they had practiced to conserve the air supply. Good Heaven! He must not think! That way lay space madness!

Then it happened. One second the after port had been clear, and space a spangle of innumerable stars. The next moment blackness enshrouded the quartzite lens, a blackness that was impenetrable, the very nadir of nothingness.

Talbot sprang up with a cry of alarm. In that instant the space boat bumped, shivered all over as if it had struck an invisible reef in the mid-emptiness of space. Out of the corner of his eye Talbot saw Apperson wheel, eyes wide with surprise. Then there was a tremendous crash, and the waters of oblivion flowed over his head.

HE awoke with nothing more than a slight headache. For the moment nothing seemed changed. The interior glowed with its normal cold-light illumination, everything appeared in its proper place. Nothing was damaged. What had happened then? He wrinkled his brow in puzzlement. Ah, yes, he remembered! The strange, sudden blanking out of space, the shattering bump, unconsciousness. But what had it been? Certainly there had been no meteor in space, no planet or star. Their instruments would have warned them of that.

He sat up. Captain Apperson had staggered to his feet, was looking at him intently, with queer, affrighted eyes. Why? He felt all right—nothing wrong, no injury, no hurt. Then why——

A scared, choking sensation overwhelmed him. He uttered a strangled cry. Great Heavens! What was the matter with the old captain? He stood there, as he had always stood, nothing changed, nothing——

With a bound Talbot was on his feet, eyes popping. That medal on Apperson's uniform, the one he kept burnished always and treasured as his life! It had been given to him by the Planetary Council for a particularly gallant rescue on the danger zone of the asteroids. It rested, securely fastened, on the right breast of his uniform!

Nothing extraordinary in that, surely, even though Apperson, the soul of order and accustomed wont, always wore it on the left. But the inscription thereon, that Talbot knew by heart, had seen countless times—FOR VALOR ON THE SPACEWAYS—was a jumble of strange symbols now. Dazed, unbelieving, the answer dawned in Talbot's unwilling brain. The inscription was reversed; the very letters themselves read backward; as if—as if it were a mirror image of the true medal.

"You've noticed it, too," the old man said hoarsely. "Thank Heaven, then I am not mad!"

Talbot gaped at him. He understood now why Apperson had seemed so strange, so abnormally wrong. Little things, ordinarily not noted, yet sunk deep in the subconscious by daily association, marred the ideal symmetry of the human form, differentiated between left and right—moles, scars, part of hair, arch of eyebrows, contours of nose. Captain Apperson had been reversed! Left was right, and right was left, even as the medal on his breast. He was the mirror image of himself!

"You, too," groaned the old man. "Everything else! Look!"

It was true. Apparatus that had been on the right stood now to the left, the after port had exchanged places with the forward port, the control board——

Talbot jumped, peered in astonishment. The gauges read from right to left, as in ancient Hebrew script, but it was not that. The velocimeter had caught his incredulous eyes. The needle had lunged far over the reversed figures of the scale, was quivering with ecstatic pressure against the guard at the farther end. The land printed figure was the limiting speed of light. If the instrument did not lie, they were traveling at a rate far in excess of that ultimate speed which the universe itself had seemed to set on man's utmost efforts.

Talbot seized the commander's arm in a grip that bit deep with excitement.

His voice was awed. "Do you know what has happened?" he demanded.

Apperson was still examining him with puzzled eyes. "I can't say that I do," he muttered, shaking his shaggy, reversed head.

"This means," the young man explained rapidly, "that all our theories have been wrong—utterly, completely wrong. Somewhere in the universe, perhaps in another time, another space, beyond the reaches of our most powerful telescope, a superforce of unimaginable intensity burst the bonds of space time.

"Something was caught in this huge flux of force—a planet, a sun, a whole universe perhaps—and catapulted into mighty acceleration. The inertial lag built up, rapidly approached the infinite. But the irresistible force was not to be denied. It hurtled the infinite mass over the limiting velocity—how far beyond, our finite instruments do not, very likely cannot register."

Talbot went on with increasing enthusiasm. "Observe closely. A paradox occurred. At the velocity of light the mass became infinite, but, in obedience to the Fitzgerald Contraction Theorem, the length of the speeding body became zero. The inertial mass was wholly width without length, a line of infinite substance.

"But, as the speed increased, another phenomenon occurred. Instead of zero length, by the inexorable workings of the FitzGerald Contraction, the length of the moving body became negative, a minus dimension. The greater the velocity over that of light, the greater the negative length. Which meant"—he gestured around the space boat, at themselves—"that we turned inside out, so to speak; that we were reversed, forward with backward, left with right.

"Apperson," he continued impressively, "that planet or universe overtook us, crashed into us. We are in it now, being carried, Heaven alone knows where?"

"B-but," the commander stammered, clinging with straining effort to the one thing he could understand, "why didn't we see it coming? We both were watching. Our instruments, too, didn't register any approach."

"Because," Talbot explained, "the onrushing planet was invisible. It had to be, aside from any consideration of its possible existence in a fourth dimension of space—an inside-out dimension, as it were. Its velocity was greater than the velocity of the light waves that should have heralded its approach. It was faster than its own light, you see."

Apperson darted suddenly to the port. "Look!" he mouthed and could say no more. In two strides Talbot was at his side. Then he, too, gasped.

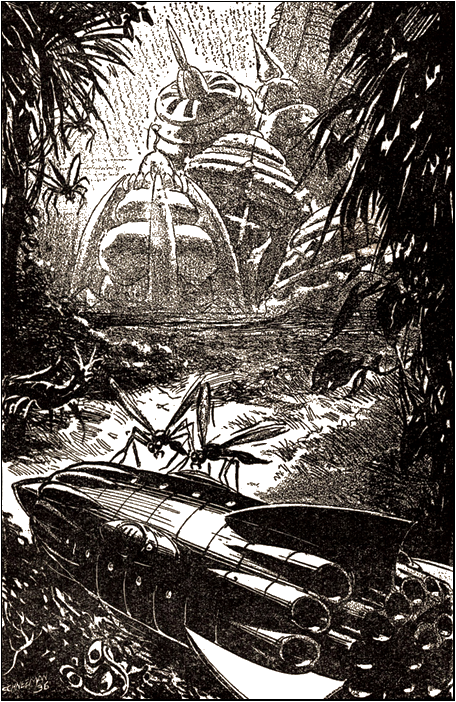

THEY were resting on the surface of a fantastic, unbelievable world. Surface? Rather the concavity of the inside of a shell, stretching slowly upward in a long curve until what should have been a horizon was shrouded in the far mist. A sourceless golden light pervaded the weird landscape, drenched its strange, myriad forms in warm illumination.

Queer monsters scuttled in the distance over ingrowing vegetation, too far away for accurate sighting. Lofty towers hung at unbelievable angles on the very verge of the horizon mist, wavering to their straining vision as if they were but bright illusions.

Talbot said with fierce enthusiasm. "There are beings on this world, beings of a high order of intelligence and civilization, who reared those marvelous structures."

But Apperson was not listening. "Look!" he pointed a trembling finger. "Look at those!"

They must have been insects or insect-like creatures. They had come up swiftly around the curving sheath of the space boat, and they hovered with graceful, pointed legs and fragile, evanescent wings over the quartz of the port.

"Like gigantic May flies," Talbot murmured. "Those flitting insects of Earth that live but an hour or two. A short life but a merry one. Hello! What's happening?"

Before their very eyes the darting insects were shriveling, getting smaller and smaller. The sheen on their flashing bodies grew more lustrous and dewy. Then, suddenly, the wings collapsed, the creatures dropped slowly to the ground, twisted into curious fuzzy balls, became moveless. Almost immediately the cocoons unraveled, and fat, slimy grubs crawled out and scuttled into the surrounding grass.

The young man started back from the port with a little cry. "Why—why," he gasped, "if it weren't absolutely incredible, I'd say life has reversed itself here also. The full-grown insect became a cocoon, the cocoon a grub. If we could follow the grub, should we discover that it had matured into the natal egg?"

Apperson was bewildered. It was too much for him—this topsy-turvy business. Talbot stopped in mid-flight, stared at him. Was it imagination, or was the gray of the old man's beard growing steadily darker? Were the innumerable wrinkles of age on his countenance smoothing out, unfolding or——

Grimly, without another word, Talbot hastened to the tiny laboratory. He must hurry! Already he felt a strange new laxness about his own limbs, already certain memories were slipping like wraiths from his mind.

The experiment he performed was simple and took very little time. Yet when he came out to face his commander there was no further question about it.

The gray of beard and hair was definitely deepening into black. Nor had there been any question about the results of his experiment. His lungs exhaled oxygen, inhaled carbon dioxide!

It was true then. In leaping past the limiting velocity of light, not only had dimensions been reversed, but life processes themselves! Existence paradoxically began with death, proceeded through maturity to youth, then on to birth! They were getting younger every minute. The Fountain of Youth, long sought by wasting age, existed in this universe of superspeed.

"We've got to get out of this at once," he snapped to Apperson. He dared not tell him why. The old man, already younger, would never consent to his plan. Yet they must get away, and that immediately.

The velocity of this hurtling planet must be in the millions of normal miles per second, shuffling time processes at a like breathless pace. In a day or two of normal Earth time Apperson might become a lad of fourteen, while he, Dick Talbot, who once had been twenty-five, would reverse into an infant in arms.

In another day—— He went to work grimly, unheeding the captain's clamorous demands for explanation. He had no time to waste—every second was precious—nor dared he provide age with vain after regrets for what might have been.

Talbot opened the forward reserve tank. There were two of them, filled with fuel. He had not used them, Apperson unwitting, back there in that other universe—just in case!

Streamers of flame blasted out. The ground leaped from under them, the space boat jerked forward with tremendous acceleration. Every drop in the tank poured into the jets. There was a loud crash, a searing, rending concussion. Talbot fell violently to the floor, and the darkness enveloped him.

THIS time when he awoke, it was to aching bones and bruised flesh. It was dark. The lights had gone out or blown from the smash, but a faint prickle of points in the distance brought him bolt upright. Some one groaned near by, stirred.

"Are you all right, sir?" he asked anxiously.

The captain groaned again in the darkness, then growled with all his old asperity. "Of course I'm all right. But what the devil did you mean, mister, by shaking us up like that?"

Talbot disregarded the complaint. "Look at those stars out there," he exclaimed joyfully. "We're back again, in our own space and time. That blast shot us right out of the alien universe. Sorry to have shaken you up, sir, but it was the only way. I had to build up tremendous acceleration in the opposite direction to neutralize the supervelocitv of their system, to bring us once more under the limiting velocity of light."

He could hear Apperson fumbling for the switch that turned on the emergency lights. He waited with keen anxiety to see what the illumination would disclose. As they sprang into being, he breathed a huge sigh of relief. Everything was normal again. Right was right and left was left, the very medal was in its accustomed place. But one thing had not changed: the darker hue in the old man's beard, all unknowing to him; the younger resilience in his own limbs. That must forever be kept a secret from Apperson.

The commander surveyed him with icy deliberation. "You have brought us back," he agreed. "But we face again a slow, certain death. In that other world——"

Talbot grinned. "I figured on that, sir. That superworld was traveling fast, faster than we can ever possibly know. And it smacked us from behind, in the line of our own flight. Look through the forward port, sir."

A sun was rising, a great white, dazzling orb. From behind its molten disk a green-tinged planet swam, its rounded edge luminous with a wavering band of light.

"Alpha Centauri!" It was more than a cry; it was a prayer and a triumphant vindication both at once.

"Exactly," Talbot said. "With a planet that we can land on. I've still a tank of fuel left. From the looks of it, there is an atmosphere on the planet—perhaps even beings somewhat similar to ourselves."

He relapsed into the formal phrases of a first officer on a well-disciplined space flier. "I have to report, sir, that we have reached our destination. Prepare for landing."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.