RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

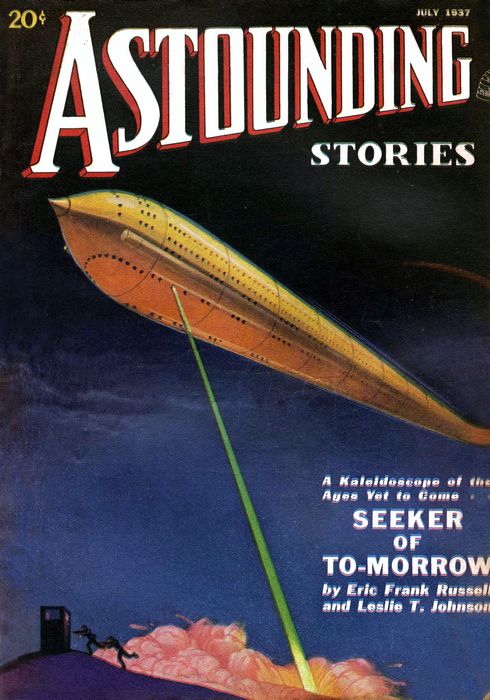

Astounding Stories, July 1937, with "Sterile Planet"

Man—the favored and latest offspring—had done this—even as——

THE DEEPS were alive with movement. Vague shapes shifted stealthily through the water-scoured gorges, climbed with feral certainty up the Continental shelf. The sun had long since set over the dun plateau of the interminable desert beyond, but the oasis of New York, set on its eerie perch, glowed in the darkness like a jewel of many colors.

Inclosed within its gigantic bubble of force, shimmering with a thousand hues, its central tower surging upward almost to the limits of the shielding screen, its lesser structures spaced at regular intervals over the fifty-mile radius of lush, green fields and close-cultivated crops, New York slumbered peacefully, unwitting of the threat that was gathering in the Deeps.

Earth was a dying planet. Yet the year was only 4260 A.D., not, as might have been imagined, a hundred million centuries thence. The sun rode as high in the heavens as ever, resplendent in all its pristine brilliance. But it shone on scenes of unimaginable desolation. Where once dense forests had swayed to kindly breezes, where once ripe, golden grain had interspersed with the green of many grasses, where once limpid streams had tapped the snows of mountain flanks and poured their life-giving floods to limitless oceans, where once populous cities, sprawling villages and isolated farms had dotted the planet's surface with the busy hum of activity, now there was lifelessness, death, drought, the fierce aridity of sun-baked wilderness.

Man, the favored and latest offspring of evolution, had done this—even as had been prophesied in the early twentieth century. Deaf to all warnings, heedless of the future, he had denuded the forests, plowed up the soil, meddled recklessly with the delicate balances of nature. This, in his vanity, he had called the march of civilization; and an outraged earth struck back. As civilization marched, so did the deserts.

The matted roots of the trees, the tangled bottoms of the prairie grasses, no longer held the rain in their intertwined fingers, to soak slowly and gently into fertile loam. Instead, the falling waters ran off in quick, scouring torrents, digging huge gullies in the land, bearing countless millions of tons of crop-bearing soil into the oceans. Then drought came, and heat, and dust storms, that lifted the dried and powdered remnants to the heavens, scattered them afar, leaving naked to the parching sun the sterile sands beneath.

The process widened and deepened, even while man fought back blindly, unwilling to sink his selfish, immediate purposes in the larger, remoter good. The streams became torrents, the rivers floods that inundated, vast watersheds, scouring more and more of the fertile mulch away, dumping it into the recipient oceans, choking them, filling them up with residual silt.

Then the waters retreated, and the rains ceased. For the exposed, porous earth drank thirstily and deep of the lakes, the streams and the rivers. These sank out of sight. The falling rain made chemical combination with the elemental rawness of the underground; the oceans evaporated and were not replenished; the skies became cloudless, burning glasses to continue and hasten the process. The deserts were on the march!

MEN fell back before their resistless sweep, huddled in the remaining well-favored places, fought one another for a foothold, harried and maimed and slew for the too-scanty food. The strong drove out the weak; the cunning evicted the simple; the ruthless slaughtered the mild, and gained for themselves temporary possession of the few oases that were left on all the earth.

But they had learned their lesson. Unless drastic measures were taken, even these still fertile spots must yield to the inevitable onslaught of the deserts, must lay forever exposed to the hatred of the dispossessed. Wherefore a certain number of scientists, men of the requisite knowledge and attainments, were graciously permitted to remain and employ their talents for the common weal.

They labored well and mightily, fighting a desperate battle against time. The oases were located in places where certain peculiar underground formations, vast, cupping strata of impermeable rock, had caught and held the ancient waters and made of them tremendous reservoirs. New York, lower Westchester and adjoining Connecticut, had such a rocky basin, a thousand feet beneath. San Francisco and its hills had another; so had Capetown; a few square miles in the Crimea; the overhang of Cornwall; Lake Tahoe; the easternmost end of the Caspian—— In all, there were not over a dozen small segments of earth where man could still find the precious fluid in underground basins.

Here the scientists reared huge bubbles of force, screens of close-knit electromagnetic vibrations, shimmering with a ceaseless play of iridescence, intangible, yet more solid and repellent than the hardest rock or steel; permitting, in regulated, tempered form, the sun's light and heat to enter, but interposing an insuperable barrier to all other vibration lengths, to the coarser molecules of tangible things.

Within these shelters the scientists evolved miniature worlds of a more primitive time. The precious waters were raised to the surface by powerful pumps, spread with careful anxiety over the hoarded topsoil.

Crops were grown in the most scientific manner, from pedigreed seeds and roots, bathed in the forcing rays of ultraviolet generators. The soil's virility was renewed with alternate fields of leguminous, nitrogen-fixing plants, with fertilizers extracted directly from the atmosphere. Meat and dairy products were obtained from strictly regulated herds, pastured on the fallow, clover-bearing lands.

Air was renewed by cautious filtering through the screens, keeping within, by special absorbents, every molecule of the precious water vapor. The plants exhaled oxygen and moisture, which latter was condensed, at proper intervals, within the orbed round of the impalpable domes by ionizing discharges of frictional electricity, and dropped back to earth in gentle showers of rain. At stated periods, when the coast seemed cleared, strongly armed expeditions took off in rocket-firing planes for the vast desert regions, where iron and copper and coal and oil still discolored the otherwise featureless terrain. They mined these essential materials in frantic haste, while wary guards stood watch with death-dealing weapons.

All in all, it was a circumscribed, precarious existence. New York housed barely a hundred thousand beings, the other oases even less. All told, not a million members of earth's once teeming, magnificent civilizations were crowded into these shelters, where life could still go on and man evolve.

BUT, though the people of the oases made hasty, desperate trips into the limitless deserts for the supplies they needed, there were other vast areas of earth's surface where they dared not penetrate, which they avoided with shuddering horror and the instinctive repulsion of long-imbrued tradition.

These were the Deeps!

The oceans had dried up, their waters lifted to the heavens by the burning rays of the sun, precipitated on the hungry deserts, and there absorbed beyond all recovery. But the mingled salts had remained behind, and now, as the seas retreated and laid bare their ancient, hidden beds, their tremendous concavities and sunken valleys and mountain ranges, the dried mineral salts formed dazzling coatings of bleached white, fifty to a hundred feet thick, forming a crust in which all life suffocated and died.

In the deeper reaches, however, those countersunk gorges and sinks known earlier as the Deeps, some water still lingered and festered. So thick it was with brine, so fully saturated, so remote and shaded from the absorbent sun, that no further evaporation could ensue. In these stagnant marshes coarse sea grasses grew, and certain fishes and mollusks, adapted by long centuries of slow change to such repellent quarters, moved sluggishly.

Always a miasmic mist hovered over the surfaces of the sinks, shrouding them, hiding the struggle that went on interminably beneath. Yet the Deeps were not devoid of human kind. The hordes of the weaker, who, long eras before, had been thrust out from the ever-narrowing oases, sought shelter on the fringes of the receding seas, followed the briny waters as they shrank farther and farther into the remoter depths, found final resting place on the shores of the quiescent sinks in the very bowels of the ancient ocean beds.

There they spawned and reverted early to a primitive savagery. The coarse grasses made their cereals, the fish and mollusks their animal food. But the greatest delicacy of all was the newly evolved protoplasmic blobs of amorphous matter that put out pseudopods in the tideless sinks. Somehow, such is the inherent vitality of human kind, the population of the Deeps had grown-by the year 4260 A. D. to a hundred million—a hundred million, in whose fumbling brains lingered the tradition of their ancestral expulsion from the oases, in whose savage breasts burned an ineradicable hatred for the fortunate inhabitants of those segregated Paradises, an inextinguishable longing for their possessions.

Woe to the oasis dweller who ventured from the protection of the screen, and fell into the hands of the ever-lurking denizens of the Deeps. Woe to the luckless rocket plane, winging its way high over the sunken salt beds in infrequent intercourse with the other far-flung oases, whose power failed and was compelled to seek forced landing near the mist-shrouded Deeps.

AND now, unknown to slumbering New York, the coastal depths were swarming with countless thousands of skulking creatures. Great, hairy, feral men they were, unkempt, shaggy, nostrils flaring with the hunt, swift of foot and nimble of step, armed with primitive weapons formed from the bones of long-wrecked vessels, with the precious freight of tumbled rocket planes.

A million wild men climbed up the steep Continental shelf and crouched in salt-incrusted valleys, panting for the signal that would precipitate them upon the looming play of colors that was their goal. For strange things had been happening in the wide-scattered Deeps. Like beasts, they had spawned and bred beyond all the primitive sources of food supply. Hunger and gaunt want stalked their ranks, drove savage bands from their lurking abodes upon the hitherto tabooed areas sacred to other tribes. Internecine war flared and died and flared again. The precious food supplies were ravaged and destroyed. Famine devoured its own.

Then a miracle occurred: a god appeared, or so he seemed to the awestruck millions. And with him came a subsidiary god. Out of the most sacred of the Deeps of old Atlantic—the Nares Deep, north of ancient Porto Rico, and descending to the incredible depth of over 27,000 feet beneath the once universal level of forgotten oceans—came the two gods, attended by a small but haughty band of attendants and warrior deities.

There had been legends about them—this secret tribe who ages before had found a home in the horrifying depths where the concentrated sun beat mercilessly upon thick, gummy air and pressures of many atmospheres. Tales of an impenetrable veil thrust over the sacred chasms, through which unwary prowlers had gone and never returned, of rumblings and tremblings that emanated from the pall and the clankings of metals on metals. A strange place, to be avoided on peril of fearsome consequences.

But now the gods had emerged. In their hands were curious weapons, similar neither to the primitive arms of the dwellers of the Deeps, nor like unto those wrested intermittently from the denizens of the oases. Their slender bodies were swathed in glittering, flexible garments and their faces hidden with terrible, god-like masks. In low, swift planes of an elder day, their messengers sped from Deep to Deep, exhorting the startled tribes in archaic language, preaching the message of revolt against the selfish masters of the oases, preaching the senselessness of communal slaughter.

The message spread like fire through stubble grass. The hungry hordes drifted stealthily by night from the farthest deeps, toiled up and down great mountain ranges, skulked by day within the shadowed gorges to avoid the scouting planes of the oasis men, gathered for the final assault on New York—a million brawny savages, driven by famine, animated by ancient injustice, led by a small, compact group that stood apart, dominated by a masked god and his subsidiary deity.

The night was dark, breathless. A faint moon gilded the sunken mountain-tops, failed to penetrate the fantastic deeper valleys. The salt ridges of the Continental shelf, pitted and scarred by a myriad gullies and holes, showed motionless and dim, disclosing no wit of the clinging hordes, alert for the ultimate signal.

The leader raised himself warily, stared at the beautiful hemisphere of tenuous fires that housed the faerie towers of New York, started to lift his arm. The slighter, slenderer figure at his side caught it with restraining fingers, pressed silver mask close to his, and whispered inaudible words.

He hesitated a moment, shook his head in denial, raised his arm again. Blue sparks flew upward into the darkness from the wand in his hand. At once, like insubstantial wraiths, the waiting hordes moved forward, wave on wave, toward the city of selfish plenty. The god had given the signal!

HIGH in the topmost observatory of the central tower, Brad Cameron kept watch. He was obviously angry. His gray eyes snapped as he checked the detector screens, made certain that the power flowed evenly through the electromagnetic mesh. His jaw was good, his nose straight, his mouth as sensitive as an artist's, but the smooth rippling of flat-banded muscles beneath his garments as he walked, the set of his shoulders, belied all possibility of effeminacy. His companion, an older, dark-visaged man, watched his irritation with a certain gloomy understanding.

"Another night wasted with this silly watching," Brad snapped, as his pacing round brought him to the screens which gave on the Deeps. Any untoward movement in those down-plunging abysses, any unusual vibration, must register on the sensitive surfaces of the plates. But they were darkly blank. "Those poor devils out there haven't the courage, the organization, to attack our defenses. Would to Heaven they had!"

Jex Bartol paled, lifted warning finger. "You're talking treason, Brad," he whispered in frightened accents. "If Doron Welles, our leader, should hear Brad's lean face hardened. "I've already told him," he answered more quietly. "We're pretty damn selfish, locking ourselves up, a limited number of aristocrats, within impenetrable walls of force, partaking of all the good things of life, while out there millions of our fellow creatures are starving and dying."

"But they're savages, worse than beasts," Jex protested in shocked accents. "Remember what they did to the passengers of the Caspian plane that fell in their clutches only last week."

"I know," Brad retorted gloomily. "Tore them to pieces and ate them raw. But whose fault is that? They're ravenous, desperate, and we made them so. Our ancestors drove them out centuries ago, to live or die—we didn't care which, as long as we were safe and snug with water and food."

"That's all ancient history," Jex said reasonably. "Earth's story from earliest times is but a repetition of old injustices. It can't affect the present. Talk sense, Brad. What would you have us do? Open our screens and let the hordes of the Deep in? Even if they didn't slaughter us at once, even if by some miracle they acted like human beings—which I seriously doubt—how long could the resources of all the oases take care of them? You know the answer. We'd all starve and die of thirst in a month—and that would be the end of life on this planet. Would you wish that?"

"N-no!" Brad admitted unwillingly. He recognized the force of his friend's arguments, had wrestled them out with himself in the stillnesses of the night. Yet they had not lessened the suffocating feeling of impotence he had always felt when thinking of the swarming savages who inhabited the Deeps. He could not, from earliest childhood, accustom himself to the hard, defensive mechanism of the others.

To them the Deeps men were foul degradations, monstrosities spawned by the fetid swamps of the ocean bed, creatures to be killed mercilessly on sight, beings without a spark of human intelligence or human emotion. Nor could Brad accustom himself to the smug self-satisfaction of the oases, to their contentment with a limited, circumscribed life, their awareness that the scanty supplies of water must inevitably disappear by slow evaporation, by absorption into the surrounding terrain. That—they shrugged—must take some thousands of years. Why should they.—whose life span was but a hundred years—bother about the remote future? The adventurous spirit, the feeling of pity, of upward striving, that, in part, had actuated earlier civilizations, had died. And with it had died the true reason for man's existence.

YET brad retained this last precious instinct: thought of life as something more than a settled, prescribed path. He longed with an ineradicable longing for something more than the limited terrain of New York, or the occasional flying visits to other oases as self-contained as his own. The illimitable vastness of the deserts, the precipitous drops of the vanished oceans, arid as they were, cruel as they must be, tugged at his errant feet with a sense of freedom, of glorious adventure.

"No," he repeated. "But there's another possibility."

"What is that?"

"To recreate life in the deserts, to bring back the oceans, to make this planet once more habitable, as we know it was in the past."

"Why should we bother?" Jex asked in some amazement. "Even if it were possible, and we know that it is not. It would mean endless toil, endless sacrifices on our part, and to what end? We are comfortable as we are; we don't need more territory, more food, more amusements than we have."

Brad looked at him sadly. "Jex Bartol," he said, "you're as bad as the rest of them—almost as bad as Doron Welles himself. Don't you understand? We might as well be dead as live the selfish, petty lives we do. Our civilization is stagnant; we've hardened in a mold." He laughed harshly. "Perhaps you are right. We're beyond all hope; it is better to let the human race die out in another thousand years or so, to let earth become a sterile orb, an empty planet revolving around a blind sun, rid at last of the disease called life. But there were moments, Jex, when I thought you understood, when I thought you might help——"

Pain showed in his friend's somber eyes. "What help could I give," he answered gloomily, "even if I were insane enough to agree? Doron has decreed that——"

Brad was swiftly at his side, his face aglow. "Blast Doron!" he cried joyfully. "I knew I could count on you."

"Are you mad?" Jex whispered feverishly. "Don't you know Doron has eyes and ears in every cranny of New York? Do you wish to be cast out into the Deeps, and left to the tender mercies of those very savages you're so much concerned about?"

"Don't get scared, old man." Brad grinned. "Long ago I made it my business to spy out all Doron's little gadgets for snooping on his most loyal and submissive compatriots." His grin widened. "It's a funny thing, but an accident happened about five minutes ago. Every one of them in the observation tower has gone strangely blank. Now listen to me. I've been working in secret for the last year—ever since Doron ordered me to stop my pernicious experiments. With your help I could——"

He stopped abruptly. His eyes widened past his friend's shoulder, fixed on the detector screen that gave on the Continental shelf. A shower of blue sparks sprayed upward over the sensitized surface, died down almost at once to unrelieved blankness.

"Hey!" Jex grunted. "What's wrong?"

But Brad had already sprung to the controls, thrust every ounce of power humming into the secondary coils. The shimmering of the outer field increased in intensity, wrapped itself round with pulsing vibrations of shattering force.

It was death to stumble into their invisible path.

"I don't know," he answered finally. A puzzled frown wrinkled his forehead; his eyes were narrowed on the screen. It was still blank. "I saw something—blue sparks that flared up out there in the Deeps, died down at once. It looked like a signal."

Jex stared at the moveless plate, smiled darkly. "You must have imagined it. The detector would have picked up even the faintest vibration."

"I tell you I saw it."

Jex cast him a queer look. "Think the Deeps men are going to attack, eh? Suppose they do. Isn't that what you were hoping for only a minute ago?"

Brad shifted his feet, did not relax his intense watchfulness. "Don't rub it in. I'm sorry for the poor devils, but they wouldn't know it. I'd go with the rest of you."

"At least you're frank," Jex murmured.

But Brad wasn't listening. "Suppose," he broke in abruptly, "they have a screen, like our own, to blank all vibrations. Our detectors would be useless. Suppose even now——"

"Don't," remarked Jex reasonably, "be an ass. Your imagination is running altogether wild to-night. Those hairy, brainless beasts fashioning a screen?"

Brad turned on him fiercely. His eyes burned. "Suppose," he retorted, "they've received help. Suppose some one else from another oasis has been dreaming the dreams I dreamed. Suppose he slipped out into the Deeps, organized them——"

"Stuff and nonsense!" Jex said impatiently. "No oasis man would be a traitor to his own kind. Would you be a party to the slaughter of every one you knew, to the end of the oases?"

Brad's jaw was a hard rigidity. "Of course not," he growled. "That's why I'm giving the alarm."

His hand reached for the button that would fling a brazen clamor throughout the wide circumference of New York, that would bring the sleeping thousands tumbling out of their beds, and send the guards in swift aero-cars to the flame guns and Dongan blasters. Within generations such an alarm had not been sounded.

"STAY your hand, Brad Cameron!"

The cold, passionless accents seemed to come out of thin air. They brought Brad and Jex whirling on the balls of their feet like pirouetting dancers.

They had not heard the smooth rolling back of the entrance panel, the cat-like emergence of the speaker.

"Doron Welles!" croaked Jex.

The leader surveyed them both with unblinking eyes. He was a small man, smaller than either of them, but he held himself with an arrogant poise that gave the illusion of height. His lips were thin and set in a straight line, his nose pinched and bloodless, and he never smiled. For twenty years he had ruled New York, as his father had done before him, and his ancestors for five hundred years previous.

For the oasis people were an easygoing race, shorn of all initiative, of all the sterner qualities that had been bred out of their soft-lapped, limited environment. They submitted willingly, nay, gladly, to orders, to a shifting of responsibility. Brad Cameron was an exception, an alien sport. Even Jex, subjected for long hours to the fiery tirades of his friend, had not quite lost that fatalistic shrug.

Doron fixed Brad with his pale, expressionless eyes. "You have been ever a source of trouble, Brad Cameron," he said evenly. "First it was forbidden experiments—experiments that would, if successful, have inevitably disrupted the even tenor of our existence, have thrown us open to certain disaster. Then you set yourself up as an advocate of the degraded creatures of the Deeps; and even, to our face, dared question our authority.

"Worse still, wherever you have been of late, strange accidents have taken place—always accidents, so you assure me—whereby your activities are withdrawn from the necessary and lawful scrutiny of your leader. For some time I have pondered your case. You are a spot of contagion which may spread and do evil. Therefore——"

Brad grinned wryly. He had been expecting this for some time. But first——

"Spare your breath, Doron," he said tightly. "You may never get around to it. The Deeps men are attacking."

Doron Welles swung swiftly, yet without haste, to the banked screens. The secondary current raced through the outer shells, but the plates themselves were still quiescent.

"If you are trying to delay your sentence——" he commenced.

But even as he spoke, the detectors sprang into turbulent life. Signal after signal blazed into being, shouted ominous warnings to the three men in the room.

The first wave of attack had rolled up to the shell of force, was hammering with flaming weapons and twitching bodies against the impalpable fields.

BRAD leaped to the alarm button, jabbed it with stiff fingers.

At once the oasis of New York burst into a jangle of great sound. In every sleeping cell, in every nook and corner, in every tower and laboratory, in the depths of the pump rooms, the long-disused alarm sent the echoes scurrying and clamoring.

The city awoke, stumbled blindly out into night, fearful, soft, unused to war and violence, trying vainly to remember dim instructions, positions to be assumed in such an event.

Doron was a brave man, and swift in his decisions. "Get to your allotted posts at once," he said calmly. "I'll deal with you later." Then he was gone, back to his aero-car, hastening to take command of the defenses.

Jex stared at his friend and groaned. "What will you do now?" he asked.

"Do?" Brad echoed cheerfully, swiftly buckling a flame gun to his belt. "Fight, of course." His face was transfigured; his eyes glowed. Here was balm for his restless spirit, adventure, the shock of untoward events. In a trice he had forgotten his former qualms, his brooding sense of injustice.

"I don't mean that," Jex countered impatiently. "We're safe enough against any primitive weapons the Deeps men can bring to bear. I mean Doron's sentence. He never changes a decision once made."

Brad paused in his outward flight, looked strangely at his anxious friend. "Jex," he answered soberly, "I'm afraid there's more to this assault than you think. The Deeps men never dared make a frontal attack before; they never massed the hordes that our screens indicate. Perhaps Doron will never have a chance to execute his sentence."

"You mean the Deeps men may win?" Jex demanded incredulously.

Brad did not answer. Instead, his hand went forward in an ancient gesture. They shook hands. Jex was speechless. Then Brad was gone, out of the observatory, into his parked aero-car on the landing space outside. His last glimpse of his friend was one of open-mouthed amazement—an awkward, undramatic picture with which to feed the memory. He never saw Jex Bartol again.

At the rim of the abyss Brad found wild turmoil and confusion. The men of the oasis, roused from sleep, blind with fear, scurried wailing and helpless from post to post, wasting their flame discharges on their own wall of force, missing completely the synchronized slits that formed and reformed with scientific precision for their benefit.

The great Dongan blasters were better manned; here a trained band of guards took command, sent infernos of destruction hurtling out into the night. Brad took his station quietly, calmly, before a synchronized slit, pressed the trigger of his flame gun as fast as fingers could twitch.

There was no question about it—the Deeps were in motion. Before him stretched the transparent, multicolored thinness of the defending mesh of electromagnetic vibrations. So tenuous, so impalpable, a mere racing whirl of shimmering rainbow, that it seemed incredible it could hold more than an instant against the incalculable hordes who washed up against it in surge on surge.

Star shells sent up from the oasis burned bright day into the Deeps—a swift slant of a hundred feet from the outer rim of New York, crusted with salt; then, far out, where the old Continental shelf ended, a great drop into depths unfathomed, into the very bowels of the earth.

Yet from those dreadful depths spewed out, in ceaseless billows, an endless spawn of men, hairy, semi.naked, snarling with savage hate, brandishing weapons of modern make and ancient resurrection alike. On they came, thousands, hundreds of thousands, millions!

THE great Dongan blasters caught their crowded, swarming ranks, tore wide gaps of destruction; the flame guns, in the hands of those like Brad who kept their head, spurted liquid fire on screaming, writhing bodies. But still they came, billowing, interminably inexhaustible.

Their weapons blazed futilely against the mesh of force, splashed huge blobs of flame along its curving surface; they threw themselves in desperate madness against the thin transparency that held them from their enemies, and piled up in smoking heaps on the secondary screen that Brad had established. Yet, with a reckless bravery that Brad could only admire, they clambered up and over the dead, seeking somehow to break through by sheer weight of numbers.

And ever and anon, the synchronized slits did not close fast enough, and a thin sheath of destruction seared through screeching defenders, crisped far off buildings, to powdered ash.

Brad squinted at his weapon, found it empty, recharged its catalysts from a placement tank, sighted coolly through the slit as it opened, squeezed. Flame caught furious faces, carried them howling into char and liquefaction.

"You are doing very well, Brad Cameron," a calm voice said in his ear.

Brad flung a hasty look to one side, saw Doron Welles, slight, erect, imperturbable, thin lips compressed, carefully waiting for his breach to flash wide. Then he took aim, fired. Strapped to his chest was a tiny microphone, into which, between shots, he spoke in level accents, sending orders to all the harried fronts, receiving information from his panicky lieutenants.

"Thank you," Brad retorted with a grin. "You're not doing so bad yourself."

The leader frowned. "You need not think," he said precisely, "by disrespectful adulation to swerve me from the sentence I shall impose on you."

Brad grinned mockingly. "Far from it. Only—I don't think you'll get the chance."

Doron swung half around, weapon covering Brad. "Just what," he rasped, "do you mean by that?"

But Brad disregarded the threatening flame gun. "Look for yourself," he said soberly. "Something's happening—at Station 15."

Doron's eyes followed his gesture suspiciously. His small eyes narrowed; in one swift movement he was on his feet, racing toward the beleaguered station, purring swift orders into his microphone even as he ran. Brad was at his side, running easily. In spite of himself, he confessed a certain admiration for Doron Welles. He was a man.

"I suspected something like this from the beginning," Brad jerked out as they raced along, side by side. "I knew the Deeps men couldn't have planned such a terrific attack by themselves. They've been organized—and skillfully—by some one intellectually our equal—or superior. Their massed assault has been a blind; the real siege was concentrated on Station 15."

Station 15 was the portal through the defense screen which gave on a narrow, subterranean plain where the Rockaways had once shelved off gradually into the depths. On this plain stood a group of a hundred men or so, clad in jet-black, flexible garments, their faces hidden behind black, anonymous masks. But two of them were differently attired—in shining, glittering garments, and masks of silver splendor. One, seemingly the leader of the band, was heavy of body and broad of shoulder; the other was slight and slender and springy of carriage.

BEFORE them, on a rolling platform, a disk whirled around and around on a cradled axis, and, as it spun at incredible speed, a shining wall of transparent force built up in front. As the platform steadily advanced, the frontier of energy moved along until it made contact with the defending vibration mesh. There was a blinding flash of incandescent energy, a sizzling, roaring sound that blasted all the other noise of battle into quietude, a flame that leaped high into the night toward the tingling stars—and the impregnable bubble that surrounded New York sagged and pressed inward.

Already the guards who manned the Dongan blasters whirled from their weapons, fled screeching and howling toward the interior city. Already the first thin gash showed ominously black in the multi-hued screen.

Brad ripped out an oath, flung himself upon the nearest abandoned blaster. Without a word, Doron stationed himself at the second.

Outside, the strange invaders pushed forward in triumph, the two shining figures in the lead. The tear was getting wider. The howling Deeps men swerved from their assault, pelted madly toward Station 15. The Continental shelf was a tossing, heaving bedlam of racing savages.

"Shoot as you've never shot before," Brad shouted. "They'll be upon us in a minute."

Doron turned prim face upon the man he intended to punish. It bespoke stern disapproval. Even in the face of swift annihilation Doron Welles could not forget matters of punctilio.

But his Dongan blaster spoke, and spoke again. There was no need to wait for slits to widen and close. The rip was wide enough for ten men to plunge through abreast. Brad's mighty weapon belched forth its cargo of destruction in quick, staccato phrases. Wherever the hurtling disruption met the lunging, unprotected savages of the Deeps, it cut wide swaths of frightful death in the close-packed ranks. But it battered harmlessly at the countervailing screen, making no slightest dent in its shining surface, and diffused into flashes of impotent energy.

On and on pressed the field of force; behind it rolled the generating disk; and on and on sped the little band of masked invaders, sheltered from all harm.

Even in the face of inevitable defeat, of sudden annihilation, Doron Welles did not, by so much as a twitching muscle, reveal concern. The Dongan blaster smoked and roared and blasted away as ever.

Brad thought quickly. The breach was growing wider. In seconds now——"Keep going, Doron!" he yelled; "Don't let up a moment." Even as he howled out his advice, he flung away from his weapon, seemed to abandon the battle in jittering flight. But he had a plan, and he wished all attention to be distracted from him.

The source of the enemy's power was the disk which built up its overwhelming shield of force. It could not be reached by frontal onslaught. But, in the swift advance, the angle of attack had shifted slightly to one side, making a thin, acute angle with the farther reaches of Station 14. There, ready at hand, on its swivel platform, rested a deserted blaster.

Crouching against observation, Brad raced for its quiescent bulk. He clawed around the edge of the platform, straightened cautiously, hidden from view. He grunted his satisfaction. It was just as he had thought. The conquering enemy screen was a thin edge toward him. By careful aiming, he could sheer along its inner veil, barely impinge upon the rotating disk.

But he must work fast. Already the line of attack was swinging in, would pivot the impenetrable screen to a wider angle. Feverishly, yet with fingers that did not tremble, he rotated the platform through a ten-degree arc, sighted his weapon, jerked all the charges in one vast explosion from the firing chamber.

The great blaster belched its multiple swath of flame; lightning bolts crashed out into the void. The gun vibrated with a cataclysmic roar, burst into a thousand pieces. Brad was flung sprawling from the platform. Bruised, battered, deafened by the mighty blast, he jerked groggily to his feet. A hoarse cry of joy rushed from his. lips, stifled almost at inception.

HIS aim had been true. The whirling disk was no more; the mesh of interwoven energy it had set up was gone. But the men who had controlled it were leaping for the steadily narrowing breach in the defensive bubble. Soon the pulsing currents from the central power station, no longer rendered impotent by the counterbalancing screen, would flow into the gap and make it whole again; but before it could, the strange, masked figures would be inside the shield. And only Doron stood in their path.

Brad flung forward, jerking at his flame gun. On they came, black, terrible figures, led by two in shining silver. Doron pointed his blaster calmly. It roared. The stocky figure in gleaming metal seemed to shatter into a thousand shards. Behind him half the men in black whiffed out of existence.

Brad heard a shrill cry of anguish from the slighter, slenderer figure in flexible silver. For a moment it hesitated, swayed uncertainly; then it darted on again, toward the fast-closing breach. But it came on alone. For behind, the survivors in black milled inconclusively, aghast at the fall of their leader, at the terrible decimation of their ranks.

Doron Welles, with a slight sneer, reached bloodless fingers for the pressure trip again. But in that moment Brad had seen, and seeing, jerked forward with a terrible cry.

The mask had been ripped loose from the slender features, had revealed to his startled gaze the delicate lineaments—of a girl—a girl of aristocratic loveliness, with warm, blue eyes and rippling, golden hair, a girl of unbelievable grace and breeding!

Doron saw her, too, but no pity showed in his thin lips, his cold, expressionless eyes. His hand did not waver from the trip. Brad could have shot him down, did not. Instead, his body was an arcing catapult, his fist a slamming thunderbolt. It caught Doron, untouchable leader of New York, behind the ear. He fell in a heap, without a sound.

The girl was already within the breach. She did not know that she had no followers. Her eyes met Brad's. She knew he had saved her life. Instinctively, Brad acted.

In a single second the flowing wall would close behind her, beyond all opening. The girl was trapped; and Doron Welles was merciless. She had attacked his domain, and must suffer the consequences. Nor would he remit his proposed sentence on Brad. Further, Brad had knocked him down, had committed the unforgivable offense.

Brad swept forward in a single motion, caught the startled girl in his arms, smashed blindly on—just in time. He flung out into the shelving Deeps, rolled over and over down the long incline, the girl locked tight and warm in his arms, right into the huddled mass of the company in black. Behind him, the barrier of New York was irretrievably whole again.

He flung up his arm as a black mask bent over him. A shining weapon swung viciously down. The girl struggled in his grasp, cried out something. The weapon faltered. Then his whirling, tumbling body crashed into a jutting rock. Stars split the darkness. He lost consciousness.

IT was obviously all a dream, or worse. He had died and gone to—well, it did not matter. He had a distinct memory, in his semiconsciousness, of having been swiftly transported in a shining aero-car of strange construction, over subterranean mountains and fathomless gorges, over tremendous fields of crusted salt, over recessive deeps, where miasmic mists veiled incredible crawling swamps—but always down, down, down to the uttermost bones of a skeleton planet.

Dimly, he was aware that the girl was at the controls, her hair a golden glory overtopping the silver flexibility of her garments. Near them fled other cars, piloted by men in somber black. With a sigh, he relaxed. Obviously, the attack on New York had failed, had been abandoned. He had been responsible for that.

But where were they taking him? His brain was still a fog from the shattering blow he had received. The depth pressure grew more and more heavy, buzzed in his ears, weighed on his heart. Each inward breath was a painful effort. Then, deep beneath his swimming eyes he saw a pall, a layer of dense, unrelieved black, impenetrable to the prying rays of the moon, making a tideless sea between terrific upthrusts of baneful mountains.

The car tilted even more steeply, plunged headlong into the inky shroud. The pressure grew insupportable. But before he again passed out of the picture, Brad knew where he was being taken. He had heard strange legends from captured Deeps men of this subterranean retreat of the gods, of the invisible tribe who lurked in these terrifying depths——

She was speaking to him, and her voice was like the plangent tone of waterfalls, of silver bells striking in unison. He was seated in a great, underground cavern, carefully sealed against the terrific pressure of the Nares Deep, made breathable by ingenious generation of air currents, lighted to ah even daylight by glow machines operated by the flash extinction of positrons with electrons.

All about them were evidences of a vigorous, well-advanced civilization, higher even than that of the oases. To one end of the vast cavern was a lake, its black waters sullen in a rocky rim.

Around it, spreading over fifty acres, nurtured by a battery of overhead heat and ultra-violet ray machines, were crops—wheat, rye, lettuce, asparagus, soy beans, com, beets—sturdy, close-grown, luxuriant.

And everywhere machinery hummed and buzzed, machinery of complicated parts—some of them recognizable to Brad, others strange in design and function. Comfort was everywhere, luxury of a more Spartan mode than that of the oases. And everywhere the men and women of this underground world, strong of body, alert of visage, efficient in movement, tended the machines, harvested the crops, nursed the hurts of those who had been wounded in the assault on New York.

BUT Brad's gaze always came back to the face of the girl before him. She had told him her name—Ellin Garde. She was more breath-takingly beautiful than he had thought, with candid eyes in which sorrow and troubled grief still held sway. Her lips trembled as she told her story; yet her voice was steady. Her words were the words of the universal language that had ruled the earth from before the great drought; yet they were queerly archaic, liquid, polysyllabic.

"We were some of those whom your ancestors drove out from the oases to die of thirst and hunger in the Deeps, Brad Cameron," she said. "We were too civilized, too philosophical, perhaps, to fight with weapons for our homes. Weston Garde, my ancestor, went with them. He was a very great scientist."

"But why?" Brad protested. "I understand the scientists were invited to remain."

She lifted her head proudly. "The Gardes were always on the side of the oppressed," she told him coldly. "It is true they asked him to stay, to build protections for them, but he refused. He went out into exile, along with those who had been driven to a seeming certain death. At first he tried to help all of the dispersed. It soon proved impossible. There were too many; and in the ferocious struggle for a bare existence, they quickly reverted to the brute, fought and slew and drove each other from the slimy swamps that still remained.

"Sick at heart, Weston Garde gathered about him a chosen group, found this hidden cavern in the deepest part of the old Atlantic, this well of still-sweet water. Here he tried to build anew his civilization, to recreate and advance what had been his ideals on earth. To keep out the ranging tribes of savage men, he screened the entrance with a dense fog of his own contriving, skillfully scattered the legend of taboo, of godhead. Some day, he hoped, these legends might prove valuable."

A spasm of pain fled over her face. "They did; though I wish now they had never been instilled. For they have brought about the death of my brother."

Brad leaned forward remorsefully. He ached to take her in his arms, to comfort her. "He was your brother then—the figure in the silver mask?" he asked gently.

She nodded her head. Her eyes were brimming with tears, but they did not waver. "Poor Haris! It was his idea, and the memory of Weston Garde urged him on. He was an idealist. The thought of those poor, starving brutes outside kept him from sleep. The reports we received through the spies we sent out into the Deeps were horrible—of men and women and children dying by the hundreds of thousands, of food supplies, such as they were, exhausted, of cannibalism rearing its ugly head.

"And all the while you, selfishly safe within your domes of force, surfeited with food and water and all the amenities of life, paid no heed to this logical end of your ancestors' greed."

"You, also, were equally comfortable and remote from the struggle," Brad pointed out.

ELLIN flashed up at that. "How dare you compare us?" she cried. "We had never been guilty of the foul injustice of the oases; we, too, were in exile." Then her indignation died; she nodded her bright head pathetically.

"Poor Haris thought of that as well," she said. "It made him more restless than ever. Finally, he determined to lead the dispossessed against their former homes, to compel a redivision of what rightfully belonged to all. He convinced our comrades that he was right. He was a marvelous orator. He built and perfected his screen of thrusting force—and he sent emissaries to arouse the dwellers of the Deeps. He would have succeeded, too, if it hadn't been for—for——"

"For me, you mean," Brad completed the sentence for her. He took her hand. It lay small and unresisting in his. "I know, yet I am not sorry—even though it meant your brother's life. For, like all idealists, he did not think things out very clearly. In the first place, he could never have controlled the savage hordes in the flush of their victory. They would have butchered every man, woman and child in the oases, for the remote sins of their ancestors. In the second place, even with the strictest precautions, with the most scrupulous conservation of every bit of food, of every drop of water, of every item of machinery, it would have been impossible to provide for all the teeming millions of the Deeps.

"Now almost a million are adequately housed; let us say five million, all told, could have been taken care of. There are a hundred million more. What would happen? The strong would rise and slaughter or dispossess the weak, even as in the past, and once more the cycle would start its weary round."

She looked at him, wide-eyed, startled. "We—we hadn't thought——"

He laughed, tenderly. "Of course not! Idealists never do."

She buried her head in her hands. "Then it was a mistake from the very beginning," she whispered in a still, small voice. "My brother's death, the death of so many brave comrades, of those poor, starving savages who depended on us for guidance—it was all in vain." She lifted her head; her eyes flashed. "I hate you, Brad Cameron," she cried vehemently. "You have taken away the only comfort I had: the thought that they were martyrs in a worthy cause."

He gripped her slender shoulders, said roughly: "Hold fast to that belief, Ellin. It's a fine, heart-warming belief. And I'm not so certain that it's wrong at that."

"What do you mean?" she demanded eagerly.

"Just this. For several years I've been working on the problem. Doron Welles forbade me to proceed any further. My plan, nebulous then, might, he thought, disrupt the peaceful seclusion of his domain, precipitate the oases men into a world of struggle, of sacrifice, of incalculable hardships. You, Ellin, and your brother, were not afraid; neither am I.

"Your desperate battle to gain salvation for the degraded men of the Deeps, though it cost Haris' life, and the lives of thousands of others, did this much: it released me from my bondage to the slave instincts of my community; it brought us together to pool our resources; and it forced a measure of organization, of discipline, upon the men of the Deeps." He smiled whimsically. "That latter will prove to be most necessary."

SHE stared at him, as if seeking to read his thoughts. The men of Nares Deep, hearing him, stopped their tasks, drew nearer to listen.

"You have a plan," she said slowly, "to—to do what?"

Brad weighed his words. "I have," he answered, "and it's nothing smaller than to rehabilitate the earth, to make it once more livable and fertile for the outlawed denizens of the Deeps."

Now he had his sensation. They dropped their work frankly, crowded around, skeptical, serious. It was incredible what this stranger promised. For a thousand years they had lived immured in this sunless cavern; for a thousand years the few oases had been walled off from the rest of the world; for more than a thousand years the earth had been a vast, lifeless tomb.

Ellin started up, fell back in despair. "I'm sorry, Brad," she whispered, "but I can't believe it."

"Yet it's simple enough," he assured her. "The principles involved are elementary; all that is required is a vast labor power, and certain scientific equipment. The first the Deeps men shall furnish us; for the second, I shall rely on your scientists for aid."

"But——"

"I'm coming to it. The earth itself is ruined beyond all hope. The topsoil is gone forever, leaving only sterile sand and rock behind. But where did this life-breeding soil depart?"

"Why, into what once were the oceans. But——"

Brad grinned. "I know what you're going to say. It's buried beneath countless tons of salt. Well, what "of it? I told you I needed tremendous man power. We'll dig the salt away, transport it to the desert plateaus of earth—not all at once, but first from the level beds, where it is not more than a few feet thick. Surely we can fashion sufficient power diggers and conveyors to release ten thousand square miles of territory within a year.

"Underneath, we shall find the most fertile, the most inexhaustible soil this planet has ever seen, even in the halcyon days of its youth. Not only does the lost topsoil of earth lie there, but also millions of years of dropped decay of plant and animal life, of dead plankton, of foraminiferous ooze.

"With this as a base, we could within the following year feed all the Deeps men on adequate rations. Meanwhile, the work will progress until all the Deeps are cleared. Actually, Ellin, since the Deeps represent about four fifths of earth's surface, there would be more habitable land than there has been since the world began."

"You forget, Brad," she protested faintly, "that there must be water before crops can be grown."

"I DIDN'T forget. I was coming to that as the next step in our rehabilitation program. The earth, as a matter of fact, never lost its water."

"What?" From all sides came exclamations of disbelief.

"Exactly. The water of the oceans, the streams and lakes of old, was not driven out into space; it simply sank into the arid soil and became unusable. Some part, it is true, entered into chemical combination with earth's elements, such as iron, and could only be recovered by Herculean efforts. But the most of it combined with thirsty salts and oxides and became fixed as water of crystallization. Copper sulphate and sodium carbonate are examples of such salts. But the combination is an unstable one; a mild heat will release the imprisoned water in the process known as efflorescence.

"We have the means to induct sufficient heat into the deserts abutting the Continental shelf to bring the water tumbling out of these buried salts and oxides. Place batteries of electrodes in the given areas at the desired depths, set up your disks of revolution, our solar converters, generate electromagnetic swirls of energy. The resistance of the soil between the electrodes will convert the energy into heat.

The water will filter through the loose sand, precipitate itself by ancient gullies into the Deeps. There we can channelize the precious fluid, use it for irrigation. Year by year, the area under civilization, the water supply, will grow larger and larger, until, who knows, in some future era clouds will form and rain descend; crops will grow and forests stretch interminably, even as in forgotten ages."

A great shout burst up from his listeners at the thrilling vision he had evoked. Ellin placed her slender hand on his; her eyes looked deep into his own.

"It will not be a matter of a day or a year," Brad said somewhat unsteadily. "It means all the days of our lives, and perhaps the lives of the children who shall come after us."

"Our children?" she repeated softly, and flushed. But she could say no more. Her further words were oddly smothered against Brad's lips. A brave new world was to be born, and they, and those who gathered around them, were harbingers of an earth remodeled. What man had destroyed in his selfishness and greed, man could restore with sacrifice and courage. The future seemed very near to them just then.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.