RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

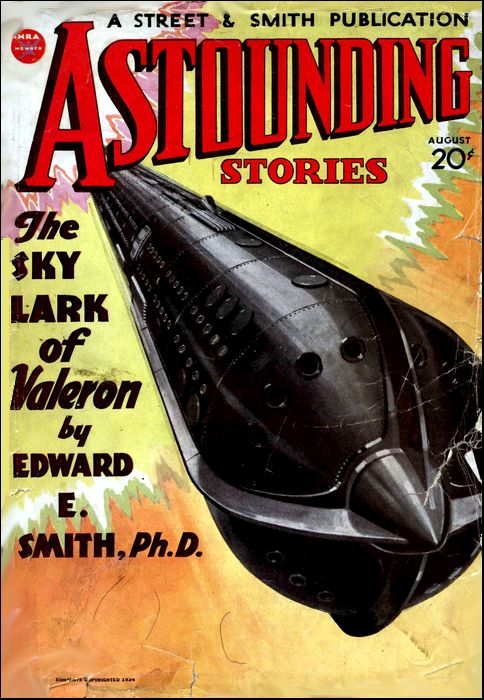

Astounding Stories, August 1934, with "Stratosphere Towers"

THE two men stood in silence on the observation rim of Solar Tower No. 1 and surveyed the barren reaches of the Roba el Khali, twenty miles below. Even through the filtrine panels, the sun-drenched sands of the great empty Desert of Arabia slashed the vision like a fiery sword. Directly overhead, a molten sun burned unimpeded through the thin stratosphere.

There seemed no life anywhere on the smooth convex bowl of the earth. Not even a cloud beneath to break the monotony of hundreds of square miles of emptiness. Only the great stratosphere tower, lonely and aloof, spurning the desert from its five-mile base. It thrust its impermite walls upward like an elongated hourglass, tapering smoothly to its narrowest diameter at an altitude of fifteen miles; then it flared out again like a funnel until it made a yawning cavity three miles across at the top.

Within the gigantic inclosing bubble of transparent impermite, the sliding facets of which were now open, a network of strong light girders crisscrossed the gap. Hundreds of tubes radiated upward from their support like a floral spray, each of them topped by a three-hundred-foot lens which glittered blindingly under the strong embrace of the sun.

The curving interior of the tower was a bottomless pit through which great tubes and cables plunged in intricate orderliness. The smooth circumference of the tower was a double shell, several hundred feet in cross section, and elevators pierced its thousand floors on the long upward rush to the observation rim near the peak. Suspension cat-walks thrust their slender fingers across the interior void to render the central cables properly accessible.

The year 2540, half a century before, had seen the last ton of coal mined out of Antarctica. One hundred years before that, oil had disappeared from the underground reservoirs. Accelerating exploitation denuded the earth of all former sources of power. And in the twenty-sixth century the machines did everything. The handicrafts were forgotten arts. One week of idle, moveless machines, and the teeming billions who had spawned over the continents during the age of plenty would perish in helpless agony.

For once the nations of the earth acted in concert. Nationalist hatreds, chauvinistic designs, ambitious rivalries, were perforce laid aside when the reports of the geological surveys came in. An international council was formed, the project of the utilization of solar heat was examined and found feasible, and feverish construction of two great solar towers to tap that inexhaustible supply began in the year 2510. No. 1 reared its stratosphere height in the neutral area of Arabia; No. 2, the antipodal tower, in Mid-Pacific, on an artificial island bisecting the equator.

It was a race against time; The tremendous towers took fifteen years to build. Disaster was circumvented by a scant five years. Now, however, as long as the sun flamed in the heavens, the problem of power was solved.

The vast energy of the solar orb pierced through the rarefied blanket of air above the towers with barely perceptible diminution, smote the burning lenses at the temperature of boiling water, slid down the great tubes in ever-increasing concentration through an ingeniously arranged series of subsidiary lenses, until, twenty miles below, the hundreds of spearheads of focused energy met in climactic fusion.

Only the stripped atoms of the impermite chamber could safely hold the resultant supernal flame. Only within the cores of the very hottest stars were temperatures comparable to this. Hundreds of thousands of degrees danced and roared their fury at the incredible restraint, but the resistant impermite tubes sluiced the flaming energy safely into the bowels of the earth, into a complex array of machines and thermocouples and dynamos, there to be transformed into subtler, but no less power-charged, electricity.

Twelve hours each day, for fifty-odd years now, the sun had flamed energy into the vast cells of the underground storage batteries, from which reservoirs it was broadcast on tight directional beams to thousands of local stations, there to be used as required for regional needs. No. 1 Tower supplied the western hemisphere, and No. 2 the eastern.

Displaying fine sagacity, the international council of scientists had laid down very simple and very stringent rules for the governance of the towers. The nations guaranteed their unconditional neutrality. Control was vested solely in the several hundred scientists and technicians who inhabited the towers.

These formed a self-perpetuating, self-governing corporation, subject only to the supervision of their own elected chief scientist. Each year a selected group of children, chosen by rigorous intelligence tests without discrimination from all the nations of the world, were brought into the confines of the towers, to be trained to the highly specialized duties that awaited them at maturity.

Above all else, they were imbued with a fanatical devotion to science and to the towers themselves; to the thesis that the towers had been built for the benefit of all mankind and not for the selfish purposes of any one group; to the plan that the power was to flow forever to all who required it, without regard to national, racial, or other distinctions. On them, it was insisted, rested the destinies, the very lives, of the sprawling millions outside. No monk of the Middle Ages ever submitted to a more rigorous code of behavior.

To prevent seizure of the towers by any group or combination for private ends, the walls were made of impermite, that curious element of closely packed protons which was impregnable against any offensive weapons known to the twenty-sixth century. The formula was evolved by the scientists themselves and destroyed upon the completion of the towers.

THE two men on the observation rim were obviously worried. They stared down through the filtrine panels with frowning concentration.

The younger man said: "There's no sign of any trouble below, Benton."

Christopher Benton shook his head gravely. His gaunt kindly face was seamed with responsibility. He was the chief scientist of Tower No. 1, and Hugh Neville, the younger man, was his personal assistant.

"The desert wouldn't show it, of course," he said. "But beyond——"

He pressed a button. A visor screen sprang into life over the bulging filtrine panel. A man glanced inquiringly up at them from its pictured depths. He was thickset and blond, with weak blue eyes behind glasses. He was seated before an instrument board on which there were banked rows of signal lenses and under each a tiny switch.

"What luck, Eric?"

"None so far, sir. I can't contact a single station. See!" he pointed. "Every switch is on. I've kept them that way ever since the first break. Yet not a lens lights to show contact. I've checked our own circuits and found everything all right. The signals are going through. The trouble is outside."

"How about Solar Tower No. 2?" Eric Mann said slowly: "No answer there, either."

Neville jerked forward. "Good heavens! That means——"

Benton made an almost imperceptible gesture that stopped the other short.

"Thank you, Eric. Keep on trying," the chief scientist said and snapped off the screen. The Teutonic features of the communications man faded quickly from the white oblong.

"We had better keep our surmises to ourselves a while, Hugh," Benton said heavily.

"But what could have happened to the Pacific Tower?" the younger man protested. It was evident that inaction sat uneasily on his broad shoulders. "A breakdown? They have emergency equipment. And the local stations! Our power output recorders show that they are all taking their usual loads, yet they can't, or won't, answer our signals."

"Since last night they have doubled their intakes," Benton corrected gently. "I've been expecting something like this for years."

"What?"

The chief scientist did not answer. Instead, he knifed the switches that connected the series of telescopes and sound gatherers which ringed the observation rim to the visor screen.

"They have a range of five hundred miles," he said. "Perhaps they'll bring us an inkling of what's taking place in the outside world."

The screen lighted up again, and the men leaned forward in breathless fascination as the scenes slowly passed in review. First Northern Arabia—the desert had bloomed under a century of irrigation, and great white cities nestled between the golden glow of interminable orange groves.

Even as they watched, the largest of the cities seemed to heave itself bodily into the air and rain back to a shattered earth in a tumbling ruin of disintegrated domes and minarets and marble columns. Twelve minutes later, through the sound amplifier, came the booming thud of the explosion. Then even as the screaming air waves blasted their way through the observers' eardrums, the scene shifted. The next telescope in the series had taken up the tale.

LONG before the sound had come through, however, Hugh Neville was on his feet, his face white, his fists clenched. "That's Haji, a hundred and fifty miles away. Gone up, smashed, with three hundred thousand inhabitants! What does it mean?"

"What I had feared." Benton's shoulders sagged under a seemingly unbearable load. "War!"

The visor screen had shifted to the muddy waters of the Persian Gulf. All seemed peaceful on the slowly swelling sea. A few knife-like prows of cargo vessels, completely inclosed, cut through the waves at a terrific rate of speed under the impact of the surging power from the tower's broadcast.

"Nothing brewing out there," Hugh said confidently. "Perhaps it's only a local squabble. Ibn Saud, Haji's ruler, had enemies."

He had hardly finished when little black specks appeared on the edge of the lighted screen. They moved with the speed of lightning across the waste of sky, growing as they did so into a horde of huge stratosphere planes that plunged with breathless rush for the cargo ships. Little brown pellets dissociated themselves from the hurtling planes, fell with agonizing slowness straight for the doomed vessels.

The cargo vessels saw the approaching menace and submerged, diving desperately for safety. The bombs smacked into the sea, and the waters rose in a gigantic waterspout. The farthest ship had delayed getting under a trifle too long. Its fragments rode the crest of the spout. Not a sound came through except the quiet slap-slap of the waves of fifteen minutes before. It would take that long for the roar of the bombs to reach the amplifiers. And again the screen changed to the third of the telescopes in the series.

The scene now was the broad Arabian Sea. The long billows were deserted. But, high overhead, squadrons of planes were locked in flaming warfare.

The lower atmosphere was a pelting hail of crisped, shattered, unrecognizable things. The amplifiers resounded with the noise of earlier battle. Then, click, and Aden and its Gulf swam restlessly over the screen. Aden was a man-built Gibraltar, the mightiest fortress in the eastern waters, the last stronghold of a once-great empire. Its great blocks of ferro-concrete rose frowning from the sea; its walls shimmered with defensive vibrations.

It was being besieged—by sea and by land and by air. Great fleets darted past in zigzag procession, churning the water with their speed, belching black darkness to envelop and make themselves inkily invisible; the stratosphere disgorged hundreds of bombers that went whistling at a five-hundred-miles-an-hour pace over the beleaguered stronghold, dropping tons of deadly delayed-action explosives.

On the land side, great tanks, like monstrous caterpillars, and shimmering with their own defensive vibrations, jumped ditches and canals, leveled off uneven terrain, surged at eighty miles an hour against the gaunt pink walls. The noise was indescribable.

Sheeted flame completely enswathed the city. The shells and disruptors exploded in a fury of sound. The heat rays bit into the ferro-concrete, sizzled in futile fury.

For the protective screen of positron swarms was holding. Here and there a combination of offensive powers crashed through the curtain, and huge chunks of ferro-concrete went hurtling inward. Then the unending stream of positrons swerved back to its original position. The defenders, through lightning-swift gaps in their defensive screen, hurled projectiles out at the attacking forces. Ships, planes, and tanks crumpled and smashed, but there were plenty more to take their place.

Click! Aden went blank, and the coast of Africa heaved into view. All along its steamy indented shore line, fronting the brick waters of the Red Sea, was ruin and desolation.

Benton seemed suddenly aged. "This is no local war," he said. "The whole world is aflame. The nations are at each other's throats. With modern weapons, that means an end to civilization, an end to everything man has been working for during the centuries. It is a pity!"

Hard fires burned in Hugh's eyes. "We can put a stop to it," he said quietly.

The older man looked at him in surprise. "How?"

"Very simply. Shut off the power broadcast."

BENTON shook his head as if he had not heard aright. He repeated the words with gasping intonation: "Shut—off—the power—broadcast!"

Their meaning seemed to penetrate slowly. He peered into his assistant's face. Perhaps he was joking, though such a sacrilegious jest was in the worst possible taste. But the young man's countenance was grim, hard.

Anger flamed then through the chief scientist. "You are mad, Hugh!" he exploded. "Shut off the power! You, my assistant, second in command, to suggest such a thing, even as a joke!"

"I was never more serious in my life," Neville returned calmly.

Benton shook his head in sorrow. "Since the towers have been built, no one has dared entertain such a treasonable proposition. Why, man, our oaths, our life's training, our whole reason for existence as scientists and custodians of the towers, have been dedicated to the proposition that the power must never cease, for an instant even, that it is the common property of all mankind, of all who wish to use it."

He placed his hand on Hugh's shoulder and spoke more kindly: "Now let us hear no more of it."

Neville shook his hand off and faced Benton with restrained anger. "If this is what training from birth and the constant reiteration of catchwords has done to us, then it is better that some one blow the tower and all its complement of routine-befuddled scientists to smithereens. It is all very well to repeat mouth-filling phrases—service to humanity, power to all without distinction of race or creed or condition! Swell! But don't you see, Benton, those phrases are hollow mockeries now, deadly, dangerous?

"By continuing to broadcast our power, we shall be as directly responsible for the destruction of civilization, for the blotting out of a world, as though we personally were out there heaving bombs and wielding conite disrupters. It is the power we furnish which makes their weapons possible. Stop the broadcasts and the war must stop. Within a week the nations will be on their knees, ready for any terms we care to impose. It is high time trained scientists take over. The politicians and statesmen have made a botch of things."

Benton said harshly, his features twisted into only remote resemblance to their ordinary kindly wisdom: "Take care, Neville. You are exceeding all permissible bounds. It is unheard-of for a tower scientist to breach the confidence which has been reposed in him. I as chief can listen to you no longer. Go to your duties and let us hear no more of it! Otherwise I shall be compelled to divest you of your emblem as a scientist and expel you into the outer world of men."

Hugh fell back a trifle. His eyes fixed in wide surprise on Benton. "You would do—that?" he said slowly.

Only once since the building of the towers had that ultimate punishment been invoked, and that was in the first ten years. The culprit had been a member of the first group, a man reared in the outer world, not one steeped from infancy in the traditions of the towers. Yet even he, shamed beyond endurance at the disgrace, had committed suicide.

Benton said in a low, barely audible voice: "Yes." For he loved the young man who was his assistant. Then, with fine inconsecutiveness, he added: "Besides, Tower No. 2 could supply the entire world in an emergency, even though we should quit operating."

Hugh started eagerly: "I could——"

A throbbing of supercharged motors beat from the local sound amplifiers into the filtrine-inclosed observation rim. Both men turned to gaze out through the panels at the star-studded sky, then down at the curving earth.

Far below, at the ten-mile level, a black speck swarmed over the western bulge. It grew rapidly on the sight, became distinguishable as a two-seater speed plane, hurtling full tilt for the tower under the impact of its electrically impelled motors.

Behind, barely twenty miles away, a fleet of battle planes rose like a cloud of bees over the horizon, droning with rapid vibration. The observation rim thundered with the multitudinous roar of many engines.

Benton snapped off the amplifiers, and the racket ceased abruptly. He sprang to the switch which controlled the domed bubble over the concentration lenses. The transparent impermite panels slid smoothly into place. The tower was wholly covered now, impregnable against outside assault.

Then another switch. The heavy blond features of Eric Mann looked at them from the visor screen.

"Contact those planes," Benton ordered. "Find out their identity. Demand to know what they are doing in tower territory. Don't the idiots know it is forbidden?"

"At once, sir." Eric plugged the local signal. His head was cocked at a listening angle; his features were impassive.

He looked up. "They don't answer, sir."

Neville said bitterly: "Perhaps they know the tradition of the towers. Service to all, even when you invade the neutral area. Perhaps they even have grandiose ideas. They may think they can capture the tower."

"Keep quiet!" Benton said sternly. His face showed conflicting emotions. "Eric!"

"Yes, sir."

"Signal them again. Warn them, if they don't answer or leave at once, we'll——"

BENTON left the phrase hanging in air. Too late he realized the ridiculousness of threats. The tower held no offensive weapons. Appeal to the nations? They were mutually at war, and such an appeal would be worse than useless. Hugh's idea? He banished it resolutely. Every one knew that the scientists of the tower would continue to furnish power even in the face of a threat to their own safety. It was taken for granted, as a matter of course, even as the air they breathed. Such was the overpowering weight of tradition.

Eric stared from the screen. His face was no longer impassive; his pale eyes gleamed behind the glasses.

"The battle planes do not answer, sir. But the single-speed plane in front has just signaled. It's the code word, sir, the code of the towers."

"Good heavens!" Benton gasped.

"He's asking for entrance, sir. What shall I do?"

Benton said harshly: "It's a ruse; some one has betrayed the word. Keep the landing port closed."

The speed plane was not more than fifteen miles away. Little puffs of smoke dissociated themselves from the following battle squadron. The puffs made white tracers through the rarefied air, leaped the intervening gap and exploded in great white clouds immediately to the rear of the lone flier.

Neville jumped. He spoke rapidly at the visor screen. "Open the landing port at once, Eric. Let him in; he's being fired at."

Mann's eyes sought Benton's doubtfully.

The chief came out of his daze. "Neville's right," he said hoarsely. "It must be one of our men."

Ten miles below, in the smooth round of the tower, a section of black impermite slid open. The speed plane hurled itself through the stratosphere, was caught in the short guiding beam of the port, swung cradling along the ray into the interior, and cushioned to a halt on the smooth white tarmac within.

Hardly had the impermite slide closed to an unbroken surface behind it than an inverted cone of flame seared through the atmosphere and blasted greedily at the tower.

Conite disruptors had been employed against the internationally neutral tower, the first overt act since it had been built. The flames licked harmlessly against the compacted protons, however, and soon burned out.

"They'll pay for this!" Neville cried fiercely. "What nation do they belong to?"

Benton looked haggard and weary. "I do not know," he muttered. "The planes are painted black and have no distinguishing marks."

The heavily armed vessels swerved suddenly in a great arc and vanished back over the distant horizon. It was as if they, too, had realized the temerity of their crime, or, Hugh thought, the uselessness of their weapons against the tower.

Benton spoke into the screen: "Send the occupants of the plane up to the observation rim at once."

WITHIN a few seconds the elevator rushed smoothly to the platform; the beryllium door went wide, and two men stepped out. Neville surveyed them curiously; he had never seen either before. But then the scientists of the towers rarely ever left their posts, and then only on approved and specified journeys.

One of the new arrivals was tall, slender, and wiry; the other shorter, yellow-skinned, and his eyes were shaped like almonds. Both men's eyes were red-rimmed with fatigue, and their clothes were rumpled as though they had been slept in.

"Identify yourselves, gentlemen," Benton commanded.

The tall young man essayed a grin. "I am Bob Jellicoe, the gentleman to my right is Atsu Mira, and we were both very recently associated scientists in the confining duties of Solar Tower No. 2."

"You are most welcome, then," the chief scientist said cordially. "I am Christopher Benton, and this is Hugh Neville, my assistant. What——"

Neville interrupted: "Out with it, man! What has happened to your tower?"

Jellicoe looked slowly at his comrade, the little man.

That slant-eyed person shrugged, opened his hands a little, and answered politely: "It was captured!"

Benton cried out: "The tower captured! By whom? How is it possible?"

Jellicoe's fatigue-stricken eyes burned. His voice was harsh: "It is not only possible; it is done; it is finished! A traitor within the gates, if you want to know. We were warned in time of the outbreak of war, so that when the hydroplanes swarmed around the tower, we were prepared. All ports were closed, and Rallitz, our chief, signaled furiously that if they didn't get out of the neutral zone at once, the power would be shut off."

Neville stole a sidelong glance toward his own chief. He saw the slowly mantling flush.

"They started arguing," Jellicoe went on, "but Rallitz was adamant. The commander of the fleet swung his vessel around as if to obey. We relaxed our guard a bit then, I'm afraid, for we didn't notice until they were close in that the momentum of their swing had brought them almost alongside.

"I was standing next to Rallitz on the observation rim at the time, and we saw them clearly through the filtrine magnifiers. The old chief spluttered guttural oaths and sprang to the power switch. He clamped it down so hard that it almost broke.

"But the ships kept on coming. The secondary switch on the rim had not worked. Even as we watched helplessly, the lower-level section opened to admit the battle planes. The tower had been captured without a fight."

"Poor Rallitz!" Benton muttered. "I met him once or twice. I never thought that he would forget the tradition of the service."

"What do you mean?" Bob Jellicoe exclaimed.

"He tried to shut off the power, didn't he?"

Jellicoe and Neville exchanged glances. Hugh's was charged with exasperation.

He made a little gesture. "Never mind that," he said. "What nation captured the tower and who was the traitor who admitted them?"

"It was," replied Atsu Mira, "the Midcentral nation, and the traitor—we do not know."

"The Midcentral!" Hugh puzzled. A vision of heavy blond features arose in response—Eric Mann, for instance. "Were any of the men members of that nation?"

Benton cried out in reproof: "You forget, Neville, that in the towers we have no nationals; every man is a tower scientist—and nothing else."

"That is, of course, true," Jellicoe said formally. "But the tower was captured—and it was an inside job. The only national of Midcentral in the tower, however, had a perfect alibi. He was with Rallitz and myself on the observation rim at the time."

"How did you get away?" Hugh asked.

Jellicoe grinned and turned to the little yellow-faced man. "That was Atsu's fault."

Mira bowed deprecatingly.

"Rallitz had darted for the main elevator before I had a chance to stop him. He was swearing that he'd fight the scoundrels with his bare hands. The port slammed in my face, and he dropped downward." His face sobered. "Poor firebrand! They must have killed him. I went for the second elevator and tried to beat him down. I couldn't let him go it alone. But on reaching the lower stratosphere port, the car stopped. Atsu was there; with a speed plane on the tarmac. He explained that it would be useless to fight, and we could get away to warn you. I saw the point, and here we are."

Benton took a deep breath. "And the rest of the world?"

Mira said quietly: "Everywhere is war! Everywhere nation against nation. What is called, I think, a dog fight. We saw cities wiped out, countries ruined, valleys filled with poison gas, tanks exploding, waters dotted with blazing ships, the stratosphere raining fragments."

"It was a miracle we came through," Jellicoe broke in. "Our single plane was an outlaw; every one's hand was against it. Luckily it had plenty of speed. Our closest call was just as we got to your tower. That fleet belonged to Northcontinent."

The visor screen buzzed, and Eric Mann looked out at them.

"A message from the chancellor of Northcontinent," he said tonelessly. "He wished to speak to you, sir."

Benton's eyes glittered. His shoulders straightened. "Switch him on!" he snapped.

THE features of the communications chief faded, and those of a tall, thin man with bold aquiline nose and piercing look took their place. He was seated at a desk in a hermetically sealed chamber. Neville knew him from screen conversations on more amicable occasions.

The chancellor came to the point at once. "Benton," he surveyed them all in one swift glance, "the neutrality of the towers has been broken. In case you do not already know it, Midcentral has Solar Tower No. 2 in its control."

"I know that," the chief scientist said, very low.

The chancellor watched him keenly. "Rallitz betrayed the tower into their hands."

Bob Jellicoe sprang toward the screen, fists clenched, his face dark with anger. "That's a lie!" he exclaimed. "Rallitz was himself betrayed. He is dead, killed, fighting to save the tower."

The chancellor's, eyes pierced him through. "Take care, young man," he said coldly, "how you give me the lie. Who are you?"

Jellicoe restrained himself. "I am, or was, one of the scientists of Tower No. 2. I've just come from there. And since when does a tower man take orders from any one?"

The chancellor shrugged and turned his gaze back to the troubled face of Benton. "He is insolent. Perhaps he, then, was responsible——" He broke off with a meaningful pause. "But that is neither here nor there, Benton. Midcentral has the tower. Already they have cut off power from all stations except the ones they control. The rest of the eastern hemisphere is helpless, starving. Within a week they'll all be dead or under the domination of Midcentral. Within a month the whole world will have fallen into their clutches. You know what that means—a tyranny such as this earth has never seen."

Benton said: "What are you leading up to?"

The chancellor leaned forward. "This! We must fight fire with fire. Give me control of your tower temporarily. I could then concentrate all your output into my battle armament, force the rest of the western hemisphere to join forces with me. Within the month we shall have beaten Midcentral to its knees and recaptured Tower No. 2."

"And then?" Benton's tone was barely audible.

The chancellor's grin was falsely hearty. "Oh, and then—ah—of course, the towers will be given back to their rightful holders, the scientists, and the world will have the peace again that Midcentral has ruthlessly violated." Neville said tensely: "You are lying again, chancellor. Once the towers are in your clutches, you will never let them go. You will use them to set up your own tyranny over the entire world. There is little difference between your schemes and those of Midcentral."

The thin man's face went black with rage. "Why, you—you infernal puppy," he stuttered, "I'll break you in two for that!"

Hugh remarked very gently: "That is a game I would like to play with you."

"Stop it!" Benton commanded. He looked steadily at the screened visage. "Chancellor, you forget things. You forget the very purpose of the towers, the oaths we took, the ideal service to all humanity we are sworn to give. Without fear or favor, without discrimination to any one, the power must go out. What do your insane quarrels matter to us, who man the towers?

"Mankind must and shall continue to live, in spite of your wars. The lives of every man, woman, and child on this earth, the billions who have always known that they need not want for food and comfort and shelter while the towers operate—we cannot let them down now, to suffer and die, because of the selfish aims of their political heads. The power will continue to go out, to all who need it."

"But," argued the chancellor reasonably, holding himself in with a tremendous effort, "Tower No. 2 is producing only for Midcentral. The others will die in the eastern hemisphere. Is that fair or-just?"

"They will not die. We shall extend our sending radius to cover the whole earth; we shall ration the power to all. It may mean a little less to each, but it can be managed."

The chancellor made no further effort to restrain himself. His rage poured out. "You stiff-necked idiot! I gave you the chance to join me; to remain in charge under me. Now I'll take your tower and make you wish you were never born. You and your silly, schoolboy traditions! Bah!"

The screen snapped off abruptly. The chancellor was gone.

BENTON'S nostrils twitched white. He pressed a button. "Eric," he said rapidly, when the communication chief appeared on the screen, "make certain all ports are closed tightly. Cut off all subsidiary switches except your own. You will be personally responsible for their operation. No one is to enter or leave the tower hereafter, under any pretext, without my personal authority.

And, Eric——"

"Yes, sir."

"Step up our sending radius to include the eastern hemisphere. Ration the power broadcasts so that every station receives an equal share."

Jellicoe started forward. "But that would mean——"

Benton halted him with a gesture. "With one exception, Eric. Cut off all power from the stations controlled by Midcentral. Your board will give you the list. Do you understand?"

For the first time the broad expressionless features showed emotion. A red flush crept slowly up behind his ears. "I understand."

Benton said sharply: "Eric Mann, you were born a Midcentral, were you not?"

The man leaned over his instrument board, fiddled aimlessly with the controls. They could not see his face.

When he spoke, all tone had been wiped out of his voice: "I am a tower scientist, sir. I have no other country."

"Good! Please remember that." Then the screen was blank again. Atsu Mira said softly: "Excuse me, please. But Tower No. 2 was lost from inside. Midcentral will try for this one, too. So will Northcontinent. Maybe you trust this Mann too much?" Benton drew himself up proudly. "In this tower we are all scientists; nothing else. You heard what Eric said." The little yellow man shrugged politely and made his face blank.

But Neville took up the challenge. "There is something in what Atsu says. Eric may be all right, but there are over three hundred of us. Some of the men may still have what used to lie called patriotic emotions for the countries of their birth. Technically, looked at from that standpoint, we are all mutual enemies in here and should be at each other's throats, praying for victory to our particular land——"

"Neville is right," Jellicoe broke in. "The chancellor of Northcontinent was not just making threats for effect. He has something up his sleeve. He knows the tower is impregnable to direct frontal attack. Perhaps he has already established communication with one of the scientists inside your walls."

"Never!" Benton exploded.

He turned on his heel, strode angrily to the main elevator, stepped inside, slid the port into position behind him, and dropped with breath-taking speed toward the lower levels.

The others watched him go.

"I still say that we should cut off the power," Hugh said steadily.

"It would be the best plan," Atsu murmured.

"We can't very well do that now," Jellicoe objected. "It would mean that Midcentral would meet with no opposition."

"I forgot the second tower."

They stared at each other helplessly. Outside, the world was flaming red war. Civilization was on the,-verge of a total eclipse. Yet they could do nothing about it, except keep up the traditions of the service, as Benton insisted. "Sooner or later," Hugh remarked bitterly, "there'll be no stations left to transmit power to, and no people to receive its benefits."

Bob Jellicoe said suddenly: "There is only one way."

"What is that?"

He looked around carefully. "Any screens open?"

"None. You will not be overheard."

"This is my plan: When it gets dark, I'll sneak my plane out and head back for my tower. I ought to get there before dawn. I'm sure the scientists were left at their posts—under guard, of course. It would take a year at least to train outsiders to the jobs. Now we have a secret identification signal between us—aside from the regular code. When the control man hears it, he'll know what to do.

"Once inside, I'll be a pretty poor sort of a chap if I can't throw a couple of monkey wrenches into the machinery. You may take it for granted that by this time to-morrow Tower No. 2 will not be functioning."

"And then," Neville added, his face aglow, "I'll pull the same job here. It may mean a broken heart for Benton, but it can't be helped. Before repairs can be made, the whole world will beg for peace. We must balance a week's suffering against the destruction of all mankind."

"That's swell!" Jellicoe said cheerfully. "It's up to you now to get me out."

"Maybe," Atsu interposed deferentially, "it is better that I handle this situation. My honored friend, Neville, is under what is called a cloud. If tower open and friend Jellicoe escape, contrary to orders, it is good for Neville to have what is known to the vulgar as an alibi."

"That's an idea," agreed Jellicoe. "You had better let Atsu handle the works, Neville. Benton would remember your expressed views and clamp down hard if you couldn't account for every minute of your time."

Hugh groaned, but saw the point.

"Thank you very much for esteemed confidence." Atsu bobbed his head. "It is almost twilight. Explain essential workings of machinery—maybe slight difference from ours; also where each man in charge is."

IN the vast underground department of the tower, the day shift was nearing its end. Soft blanketing twilight enveloped the sleeping sands of the outside desert. A faint mist swept in from the Arabian Sea, obscuring the ever-burning stars. It wrapped itself around the sky-piercing tower to a height of five thousand feet. Up above, fifteen miles of impermite walls loomed in eternal silence, bracing the thin clear stratosphere where the stars hung luminously by night and by day.

Within the topping bubble the sun still shone, and the gigantic lenses still concentrated the last slanting rays down through miles of tubes and lenses into the furnace hells of ultimate fusion.

The vast complex of machinery far below still pounded and whirred, converting the inexhaustible heat into electrical surges. But within minutes it would be night even in the stratosphere, and the machines would slowly idle down to quiescence, shining sleeping monsters that would wait for another morning to spring again into beating life.

Then the night shift of technicians went on duty, the scattered few who kept certain essential duties alive during the long hours until dawn and guarded key centers. The communications board was of course the most important of these.

Already the day men had gone to their quarters. Philippe Thibault came sprucely into the communications room.

Eric Mann looked up at his dandified, yet vitally alert, assistant.

"Hello, Philippe!" he greeted. "Is it time?"

"But of course, Eric. Catch you forgetting your shift is up."

"There's a reason," Mann remarked slowly. He seemed to have difficulty with his speech. "Benton has given strict orders, made me personally responsible for their execution. I have still about an hour's work. Tell you what, Philippe. Come back at nine o'clock to relieve me. By that time I'll be through. Then you can take over. How does that sound?"

"Magnificent!" Thibault gestured vivaciously. "To tell you the truth, Eric, I was just in the middle of an exciting spy story—now I'll be able to finish it."

The communications chief smiled faintly behind his glasses. "Those eternal spy stories of yours! The feeble efforts of weak imaginations. I'm surprised you read them."

Thibault said good humoredly: "They give one vicarious excitement. Life in the tower gets tedious now and then. And as for feeble efforts—listen to this!"

"By nine o'clock, then," Eric reminded him and bent over the board.

"Sorry!" Philippe chuckled and went out of the room.

He strode whistling through the dim cavernous interior, threading his way with sure knowledge between ponderous machines, exchanging short greetings with the few scattered custodians, each seated comfortably in his own pool of light. He did not notice the slight figure that glided noiselessly from shadow to shadow, avoiding the areas of illumination, pressing against a looming machine until Philippe had passed, then darting swiftly to the cover of the next one.

Philippe entered his elevator, shot swiftly to the mid-belt of dormitories, already in his mind's eye anticipating the mounting excitement of the spy story that awaited him.

ATSU MIRA was but a shadow among shadows as he wormed his way into the darkened communications room. A brilliant spot of light flooded the board to the farther end and splashed over the bent, absorbed blondness of Eric Mann. The room was desperately silent, filled with the brooding hush of danger. Atsu paused, tensing his muscles for the last swift spring across the composition floor. He held a compression disk lightly in his hand.

Mann stirred and grunted impatiently. Atsu stiffened in his stride, waiting. A little red signal lens glowed on the board. It was too far away for Mira's straining eyes to determine what station it came from. The communications chief made a feverish little sound with his teeth; his hairy hand sprang out and did a surprising thing—he clicked off the visor screen.

A swift guilty glance around barely missed the intruder's crouching form. Mann scooped up a silence unit, adjusted its electrodes two feet on either side of him. Only then did he plug in under the glowing signal.

Atsu waited. He was curious. He saw Mann's head cocked in listening attitude, saw the queer mixture of fear and greed that flamed in the broad squat face under the spotlight, saw the thick lips open and close rapidly.

He knew that Mann was talking to the unknown station, but he could not hear what was being said. The silence unit took care of that. It was a simple contrivance to insure secrecy; the pulsing orbit of waves that circled between the electrodes damped the sound waves so that they were inaudible outside a limited area.

Eric Mann shook his head several times as he talked soundlessly; then he listened again, and the greed in his face overshadowed the brooding fear. He nodded, reached up, and plugged out the station.

As he did so, Atsu acted. His quick pantherish rush brought him upon the unsuspecting communications chief before he had a chance to move. A slight but muscular hand clamped the compression disk over the thick, fleshy lips. Mann saw the descending disk and screamed. But the still effective silence unit made the yell inaudible in the outer chamber.

Then he slumped suddenly in his chair. The disk on pressure had released a fine spray of powerful narcotic. Eric Mann would sleep for at least an hour under the dose.

Atsu worked swiftly. He lifted the heavy figure with surprising ease, carried it to a darkened spot in the room, and dumped it down unceremoniously. Then he glided back to the board. In his mind's eye he had fixed the position of that erstwhile glowing signal lens. He stared at its blank rotundity now, read the name of the station underneath. He started violently, looked at it again. He passed a bewildered hand over his face and shook his head. Could he have made a mistake? Might it not have been a lens or two off either way?

No! He had fixed it too definitely before he had attacked. His yellow features went grim and thoughtful. He swiveled hastily around, raked every cranny of the room for skulking shapes, thrust his head out of the silence unit. No one was around; not a sound filtered in from the vastness outside.

Satisfied, and with a slow grin mantling his ordinarily impassive blankness, he knifed the switch which opened the exit port of the lower stratosphere landing unit.

BOB JELLICOE fiddled impatiently at the controls. He was seated within the hermetically sealed body of the speed plane, waiting for the port to open, for the guiding beam to thrust him out into the stratosphere. Through his viewport of filtrine he could see the taut, anxious features of Hugh Neville, eyes glued to the smooth round of the impermite wall.

The minutes sped by, and still nothing happened.

Bob jerked open the filtrine panel, thrust his head out. "Now what the devil's taking Atsu so long?" he muttered. "I should have been out of here twenty minutes ago. As it is, I'm shaving dawn too close at the other end for comfort."

Neville turned his head. "I'm afraid he's run into trouble. I should have gone myself; my presence down there would have excited no suspicion."

"If I don't get out in ten minutes, there's no use my even starting," Jellicoe said resignedly.

Neville's square jaw tightened. Without a Word he moved toward the elevator.

"Hey! Where are you going?" Bob cried.

Hugh flung back over his shoulder without pausing: "Down to the communications room. Atsu or no Atsu, you'll be out on time." And the elevator slammed shut.

Bob cursed and lifted his eyes. The air-lock signal was glowing. That meant that within thirty seconds the inner slide would open and both plane and air in the chamber swoosh out along the guiding beam into the rarefied stratosphere.

He ducked his head hastily into the cabin, sealed the filtrine panel just in time to feel the gliding movement of the plane, see the yawning black of outer space. Then he was out, cradled along.

"Atsu did turn the trick!" he told himself exultantly as he switched on the current for full speed ahead.

The plane leaped forward into the high reaches of the night like a rocket.

Neville hurried grimly through the cavernous depths of the tower. Had Mira slipped up? Had Eric become suspicious and raised the alarm? Was the whole plot even now being exposed?

The silence of the darkened vastness somewhat comforted him. There had been no hue and cry. He encountered no one, but then he had taken care to avoid the fixed guard posts.

He came swiftly to the communications room, listened. Not a sound from within. Very quietly he stepped inside.

ATSU MIRA waited with the impassiveness of his race until the flashing lens showed that the speed plane had passed out of the tower, then he switched the port back into position. What he had told Jellicoe and Neville he would do had been accomplished. Now, according to plan, it was his duty to restore Eric Mann to his seated position in front of the board, spray him with the counter-narcotic he had in his pocket. Within a minute the sleeping communications chief would be wide awake, and all memory of the attack and the potion erased from his mind. It would be as if he had nodded at his job for a fleeting instant.

Instead, Atsu Mira searched the hoard carefully until he found the signal lens he wanted. He switched in underneath, making sure that the silence unit was still functioning.

A guarded voice swirled within the limited confines of the electrodes: "Stillwig!" It was a code word.

Atsu grinned delightedly. "K-4."

"Good! You are at the controls?"

"Yes."

"You will proceed according to plan?"

"Of course! By to-morrow noon Tower No. 1 will be out of commission." He chuckled. "And the assistant in command himself will do the work. I have so arranged it."

"Splendid! Do not delay. Good-by."

"Wait! I have information. Jellicoe, who flew me here, is on his way back to Tower No. 2. He has a secret code word to obtain entrance from his friends inside. I could not find out what the word was. Take all precautions. He must not enter."

The invisible voice was coldly cruel: "We shall take care of him."

"Another item of importance. I may be mistaken, but I am almost positive I caught Eric Mann, the communications chief of this tower, talking secretly to a station which belongs to——"

Atsu's supersensitive nerves felt the impact of watching eyes. Long training made him act smoothly, efficiently. His hand flicked to the switch, shut off the telltale glow of the station signal, glided to the control of the silence unit. Then, without haste, he arose, turned around.

His eyes widened at the sight of Hugh. "Neville!" he whispered. "You should not be here. You will not be able to plead what you call alibi."

"You took so long, I came down to find out what caused the delay."

Atsu bowed formally. "It took little time, but Atsu Mira never fails. Friend Jellicoe already speeding to destination; there in corner is honored body of cow-like chief. He is peacefully asleep."

"Good!" Hugh approved. "Now we shall wake him up, and he won't be any the wiser."

Atsu put his finger to his lips. "Sssh!" He stared apprehensively around. "What's the matter?"

"Treachery!" whispered the yellow man. "When I enter, I find Mann with silence unit set up, talking to certain station. I sneak up on him to give him whiff compression disk, but too late. He already switched off station. But I see which it was."

Hugh eyed him sharply. "That's Eric's job, talking to the outside world. What's the treachery in that?"

Atsu moved closer, whispered: "It was Tower No. 2 our friend was making talk with."

Hugh jerked. "Are you sure?"

Atsu bobbed his head. "I am most positive."

Neville passed his hand over his brow as if to clear away a mist. "Treachery!" he murmured. "Within the towers—first No. 2; now here. The tradition of the towers! Bah! Poor Benton, with his loyalty and passionate devotion—how it will hurt!" He smiled quizzically. "Yet in a way, Atsu, we, too, are technically disloyal. In our case, however, it is for the greater good of all mankind."

"Of course!" Mira agreed politely.

"But Eric! Selling out to Midcentral. Or was it so-called patriotism for the land of his birth—the instinct that Benton was positive had been rooted out of the scientists?"

Mira listened attentively, but did not answer.

Neville gripped his arm. "You did not hear what was said?"

"No. The silence unit was in operation."

"Then we cannot be sure. Listen, Atsu. Not a word of this to any one. We must give Eric the benefit of the doubt and keep careful watch. Neither he nor any one else must know our suspicions."

Atsu bowed. "You are my chief."

"Give me a hand with him."

Together they lifted the limp body, set it in the chair, its head lolling over the desk in front of the board. Atsu took out a tiny squirt, sprayed the colorless fluid over the drugged man's face. Almost at once the color crept back into the flaccid cheeks.

Hurriedly they slipped out of the room, just in time to avoid the whistling approach of Philippe Thibault. Eric was already stirring.

At the mid-belt of the tower, Neville and Mira parted, each for his own quarters.

"To-morrow!" Hugh said.

"To-morrow!" Atsu echoed softly. "Perhaps, though, we watch friend Mann to-night?"

"It's not necessary. Thibault is on duty now, and I'll answer for his honesty. Eric, if he really meditates treachery, won't have a chance to do anything until to-morrow." His jaw hardened. "I'll see about him personally then. Good night!"

But a change came over Hugh as he watched the retreating back of the little yellow man. Something strange glittered in his eye. He swore softly to himself. For he had paused an appreciable moment in the doorway to the communications room before Atsu had sensed his presence.

His fingers drummed nervously against the wall of the elevator. Then, with a quick gesture, he closed the slide, pushed the button for the five-mile drop back into the depths of the tower. He must get to the bottom of this mystery before dawn.

BOB JELLICOE flashed through he stratosphere on his journey half around the world at a tremendous rate of speed. The power waves from the tower he had just quitted surged through the plane's converters, actuated the superchargers that compressed the thin atmosphere, sent the propellers spinning at thousands of revolutions per second. Europe spread like a great map below. He switched on the infrared magnifying ray, sprayed it over the unfolding continent.

The ground lighted up with a pale red, featureless light, in which everything looked flat and wraith-like. But the beam was invisible from below, even to those bathed in its illumination, and therefore safer than the ordinary search ray.

Jellicoe sucked in his breath at the spreading panorama. Where great cities had once stood were now scorched ruins, still smoldering, vast holes in the ground, deserts. Those few which remained shimmered with the blue defense-vibrations. In places the very ground itself burned with the unquenchable fires of the Dongan pellets.

His invisible beam caught and held on great hordes of fleeing people, streaming along the roads, stumbling in blind panic over shell-torn fields, falling never to rise again, crushed under the rush of the fear-maddened multitudes—a mass migration of men, women, and children who had never before known the bitter realities of warfare.

Even in the night there was fighting. Monster tanks locked in mortal combat; flames seared thousands out of their path. The darkness was torn by star shells and sudden blasting cones of fire. Huge battle fleets appeared out of nowhere, hurtled downward in headlong race. Once Bob had to dive sharply to avoid a head-on collision; another time a vagrant pellet exploded out off the tip of his plane.

Then, with backward-seeming rush, the Atlantic gleamed far below. Yet even here there was no peace. Huge submarines cleaved the green depths, grappled furiously with other shining silver fish; they rose to the surface and darted after cargo vessels like monstrous bugs, or burst through the water to rise into the air with a great unfolding of wings.

In the depths of the sea, on land and water, in the air, the war of extermination raged. Every man's hand was against his brother. Such suicidal mania could not continue. Within a week, unless somehow stopped, the fratricidal warfare would mean the end of civilization and reversion to the beast; or one nation, by annihilation of the others, would force its will upon the world. That nation, thought Bob grimly, would necessarily be Midcentral.

The Atlantic fled away beneath; then the welded unit of North America vanished like a dream, and the blue Pacific rolled interminably. Bob turned south, pushing his plane to the utmost. It was still dark.

A hundred miles away he saw the great hourglass-shaped tower, stretching its dim gauntness up into the heavens. Below, the predawn mist hid the Pacific, made it a tossing world of smoke. He checked his speed, rapped out the secret word on his transmitter. His comrades would understand.

He idled the plane along at a bare hundred miles an hour, waiting for the answer. White search beams plucked like questing fingers from the observation rim, far overhead, but he had no difficulty in avoiding their sweeping paths.

His heart hammered furiously. Why was there no response? Had his mates gone over to the enemy? More likely that they were watched, or that a Midcentral partisan had been placed in charge of the all-important communications board. Of course, that was it! He remembered the unknown traitor. In which case——

His receiver buzzed. He almost shouted his joy. Good old comrades! They had heard and understood. Naturally it was not the answering code word i there were enemy watchers.

He put on speed again; slammed directly for the mid-section of the tower. Already the great topping bubble was blazing with the morning sun. Within five miles the guiding beam caught him, held him on an even course. The impermite wall opened before him; the plane slid in and halted on the smooth white tarmac. He slid open the filtrine port, thrust himself stiff-leggedly out into the dimness. Only a pilot light glowed.

"Thanks, old mates!" he said to the silent, clustering figures. "I knew you wouldn't fail me."

Then, for the first time, in the dimness, he noted a certain strangeness about the figures, the thick silence. These were not his comrades, these were—— He sprang backward, trying to somersault into the plane port.

It was too late. The figures converged on him in a swift, silent rush. Strong hands clutched at him, pulled him down. He tried to struggle, but there were too many of them. Something hit him heavily on the head; there was an explosion of stars, and he went under, unconscious.

HUGH NEVILLE, brows knitted, made his way swiftly and openly into the communications room. This was a job he would have to unravel alone. He dared not call upon Benton, his chief. In the first place, he had nothing but certain suspicious actions to go upon; in the second place, it would effectually put an end to his own scheme.

By noon to-morrow Bob Jellicoe had promised the stoppage of Tower No. 2. And Jellicoe struck Neville as being a man of his word. It was up to him, then, to throw his own tower out of gear. If he didn't, it meant that Midcentral would be helpless at the mercy of her foes, notably Northcontinent. He did not want that. The only effectual method of saving civilization was a quick peace without victory; and that meant he must do his part.

Philippe Thibault looked up quickly at his entrance, guiltily shoved the book he had been reading under the desk. He grinned apologetically at the assistant chief.

"Sorry, sir! But there's nothing stirring to-night." He indicated the lightless board. "So I thought it wouldn't harm to——"

Neville said: "I'm not here to snoop, Philippe. I come on very grave matters, and you've got to help me. Above all, absolute secrecy is essential, even from Christopher Benton himself."

"Eh, what's that?" Thibault was startled and showed it.

Hugh said rapidly: "When you came on the shift, did you notice anything about Eric? His manner, his demeanor, I mean."

Thibault's shrewd features sharpened. "Well," he admitted reluctantly, "he did seem a little thick and hazy; vague, if you know what I mean."

"I know all that; it's other things I'm interested in. For instance, the silence unit that was set up on the board. Did he say anything about that?"

"Eh! How did you know——"

"Never mind how I know," Hugh retorted impatiently. "What did he do or say?"

"W-e-ll, he seemed a bit upset; I'd say he was considerably excited. He pushed it down off the board quickly, as if he didn't want me to see it."

"A-a-h!"

That meant Eric himself had set up the silence unit, not Atsu. Then perhaps the little yellow man was right—Eric was the traitor. Yet Atsu had spoken to some one within the zone of silence before Hugh had entered the door. That, however, might be explained. He might have been trying to establish communication with Tower No. 2, to find out things. But, then, why hadn't he said something about it to Hugh?

It was all very complicated. He sighed and was aware that Thibault was watching him curiously.

"Listen, Philippe. Don't ask me questions, but I want you to contact Tower No. 2. Put up the silence unit. We mustn't be overheard. And I want you to disguise your voice like Eric's; pretend you are he."

Thibault stiffened. "Sir," he said formally, "I am under strict orders as handed down from the chief scientist himself. No one is permitted the use of the communications board except Eric Mann and myself. Tower No. 2 is now an enemy station. Furthermore," he went on more warmly and more humanly, "I'll be damned if I'll play such a dirty trick on my chief."

"Your personal feelings and devotion to duty do you credit, Philippe," Neville approved. "But this involves the fate of both towers, not to speak of the future of the world itself. We've got along together in the past, haven't we?"

"Y-e-e-s."

"Trust me this once, then."

Thibault looked a long time into Hugh's clear eyes and sighed heavily. "I am committing a breach of duty, but I'll——"

Without another word, he reached for the silence unit, plugged it in. Then, while Hugh thrust his head into the circumscribed circle of sound, he switched contact with far-off Tower No. 2. The visor screen was off.

"Who calls?"

Cold, clipped words swirled around them.

Thibault altered the pitch of his voice. It was a perfect imitation of his chief.

"Eric Mann." He achieved the effect of whispered urgency. "I forgot to tell you something. Listen!"

"Eric Mann? You forgot to tell me something?" The bodiless voice sounded puzzled, angry. "Now what the devil do you mean? I never spoke to you. Who are—— Eric Mann! Hold on a second." Breathless silence, then: "You're communications chief of Tower No. 1, aren't you?"

"Of course; you know that."

The voice was suddenly wary. "Well, what is it?"

Hugh reached over and snapped off the connection. They stared blankly at each other.

Thibault said quietly: "I still don't quite understand, but if it was a test, you've made a mistake."

"Yes," Hugh agreed slowly, "I made a mistake. Eric is loyal. Now, Philippe, I'm making another test. This time I'll do the talking. Contact the tower again."

"Who calls?" It was the same cold, clipped voice.

Hugh slurred the words: "Atsu Mira. Very sorry, but some one suspicious. Found him calling you. He call no more—any one. I must tell you——"

Hugh allowed his voice to trail off to inaudibility. There was silence for two pounding seconds.

"Atsu Mira! Never heard of you." The far-off speaker raised his tones in seeming anger. "What the devil is this all about, anyway?"

Neville broke contact, switched off the silence unit.

Thibault gaped at him. "Now what in the name of Saturn's rings——"

Hugh was a study in complete bewilderment. "I don't know any answers," he interrupted rather peevishly. "Either I'm all wrong, or else——Philippi," he said earnestly, "forget everything that has just happened; erase it from your mind."

"And why, pray, should the assistant communications chief erase matters relating to the tower from his mind?"

BOTH Neville and Thibault sprang to their feet, whirled around. Christopher Benton came slowly into the room, his usually kindly face stern and hard. His swift glance took in the silence unit, the guilty starts.

Hugh went white. "Benton!"

"Yes, Benton, chief scientist in charge of this tower. The man who loved you and whom you have betrayed. You and your fellow conspirator, Thibault. I saw the signal light. You were communicating with Solar Tower No. 2." Hugh stiffened under the lashing voice. "It does sound bad, doesn't it? And what is worse, I can't even explain just yet. I can only ask you to trust me; to accept my word without explanation that what I am doing is for the best interests of the tower, of the world. And Philippe has no knowledge of my plans; he did only what I beg you to do now—trust me blindly for a while."

The old man's eyes smoldered with mingled fury and sorrow. "You always were glib of tongue, Neville. I don't believe a word you say. From this time on, you are no longer a scientist of the tower; you have disgraced the brotherhood. To-morrow your cases will be dealt with properly. Until then——"

He took out a tiny whistle, blew on it. The sound pierced the silences of the underground, sent its impulses beating up the sound tubes to all the dormitories of the mid-belt.

Hugh took a step forward, put out an imploring hand. "You are destroying the tower."

Men rushed in; guards, weapons in hand, scientists, some half dressed. They came in increasing flood, ranged around the great room, curious, excited at the strange summons. On the outskirts Hugh noted Eric Mann in a sleep suit, licking his thick lips, and Atsu Mira, fully dressed, calmly impassive as ever.

Benton stilled the confused babel with a stern, imperious gesture. "Hugh Neville and Philippe Thibault are under arrest and stripped of association with the scientists. They have betrayed the high trust that was in them. Eric Mann, you will take immediate control of the board, until I can arrange for trustworthy relief."

Mann came forward respectfully, his face twitching. "What have they done?" he asked hoarsely.

"They attempted communication with Midcentral at Tower No. 2."

A low growl of horror swept the massed scientists. It was the unforgivable sin.

Guards sprang to either side of the prisoners. Hugh held his head high, though despair seethed within. Just when it was most necessary that he have a free hand, he was to be confined, disgraced.

As they were led through former comrades who now shrank away from contaminating contact, Hugh caught sight of Atsu. That worthy's eye dropped in a significant wink.

DALZELL, commander of the Midcentral forces in the Pacific Tower, stared at the board where the signal lens from Tower No. 1 had twice flashed, and twice been abruptly cut off. His bulldog face was screwed into puzzled inquiry. First, there had been a purported message from one Eric Mann, cryptic, mysteriously cut off. He knew him only by name. Then, more disturbing, the voice, or a good imitation, of Atsu Mira. But Atsu never used his name; invariably it was his code symbol, K-4.

What did it mean? His black brows grew blacker. One thing only; that Tower No. 1 was suspicious and was fishing for more definite facts to justify their suspicions. Atsu might not be able to perform as he had promised.

Dalzell was accustomed to swift decisions. "Hellwig!" he barked.

The colonel clicked heels and saluted. "Highness!"

"The stratosphere fleet leaves in thirty minutes. Fully equipped, all weapons. We attack Tower No. 1 on arrival. Atsu may still find means to help us from inside."

"Your highness' will is done."

"Another thing, Hellwig: Leave orders concerning Jellicoe's capture on his arrival. He is to be held for my return."

ERIC MANN burned with a dry fever. His eyes glittered behind his glasses; he licked his lips continuously. He was alone again in the communications room. His head still ached from the strange arrest of Neville and Thibault; he felt fearfully that somehow it affected him.

It was too late now to withdraw; he must go through with it. Yet even the tempting vision of power and fortune that had been skillfully dangled before his eyes no longer was the driving motive. It was fear—fear of impending discovery that hounded him on to further treachery.

This time he locked the door before he signaled. The light showed contact.

"Chancellor!" he whispered, even though the silence unit was functioning. "It's Eric Mann."

"Well?"

"Things have happened here. I can't explain now, but you must accelerate your plans. To-morrow will be too late. I may not be on duty. You must attack at once."

The chancellor was also a man of instant decisions. He sensed the urgent terror in the traitor's voice.

"The fleet leaves in thirty minutes. Remember what you have to do. And, Eric—if you perform your part well, I shall double my previous offer."

HUGH NEVILLE paced feverishly up and down the narrow limits of his cell. Thibault had been placed separately. Hugh's thoughts were whirling. Something was brewing, of that he was sure, and he was helpless. Yet who was the traitor within the gates? If Atsu was honest, then it must be Eric; if Eric was blameless, then it must be Atsu. A vicious circle without a ray of light. Excepting only one: The reason why the calls to the other tower had failed. The informant assuredly had a code name of identification, and of course he had not used it. The only result was that Midcentral was now on guard.

He did not sleep, but kept on pacing.

He glanced at his time signal. It was almost four in the morning. What was happening outside? The walls of his cell were impenetrable.

He stopped suddenly. Something was scratching faintly. He listened. The noise continued. Then the slide door disappeared smoothly into its recess. A man stepped through.

"Atsu!" he exclaimed.

The yellow man's finger was at his lips warningly. "No noise, please. So sorry what happened. But dared not interfere. Waited my chance. Now follow me."

"But how did you unseal the door? It has a photo-electric circuit, which only Benton's image will break."

Atsu grinned. "I find that out. So I take liberty to invade honorable scientist's room in his absence and discover a stereo-image of him. I enlarge in stereo room to proper proportions and hold honorable image before cell. Foolish cell don't see difference."

They had already glided out of the punishment chamber, were making their stealthy way to the elevator. No one was in sight. Hugh's muscles were tensed for impending action. He felt ashamed of his former suspicions of the yellow man.

"Thanks!" he said simply. "What has been happening?"

They were dropping with tremendous velocity to the lowest level.

Atsu said earnestly: "I try again to listen to Eric Mann. But impossible. He lock door. You know—I think——"

"What?"

"That he know what is called game is up. That you suspect; that you soon convince honorable chief. So he signal Midcentral to come with fleet, and he let them in."

Which was a shrewd guess, except that Mira knew it was Northcontinent to whom Mann had sold out. He did not want that to happen. It would smash Midcentral's dream of conquest if the rival nation controlled the tower. What he did not know, however, was that. Hugh had spoken to Dalzell, using Mira's name, and that Dalzell, worried, was even now speeding with a great fleet to the attack.

Hugh thrust his jaw forward. "We'll put a stop to that idea," he declared grimly.

They threaded their way carefully to the dim underground. The scientists had gone back to their duties, or to bed, disturbed at the seeming treachery of two of their comrades.

Hugh tried the door carefully. It was locked, from the inside. He knocked commandingly.

Nothing could be heard through the soundproof door.

Then it slid open, and Eric stood there, confused, stammering. "I—I was afraid of more trouble, sir, so I just——"

He saw then the grim features of the man who was supposed to be safe in the detention cell and sprang back. He opened his mouth to yell.

Hugh moved with the swiftness of a pouncing panther. One long arm shot out to catch him in a strangling neck hold, the other clamped firmly over the parted lips. The sound died down to a gurgling gasp.

Atsu Mira glided sinuously into the room, catfooted for the board.

"Wait!" Neville twisted his victim in front, propelled him across to the chair. "Lock the door first. We have a long job on our hands."

Atsu paused, turned back. It wouldn't do to arouse suspicions now. He must act circumspectly and with care.

ERIC was like putty in Hugh's powerful hands. He fell like a lifeless sack into the chair in front of the board. His face was blue with congestion, and his breath came stertorously under Neville's strangling grip. Hugh relaxed a trifle.

Eric put his hand gingerly to his bruised and lacerated throat. His eyes were wide with fear, but he said nothing.

Atsu had come back and was staring down at him blandly.

"Now!" Hugh said with deadly intonation. "It is our turn, Eric. You will talk and talk fast."

"I don't know what you mean."

Atsu interrupted smoothly. "Why bother with traitor? We know he communicated with enemy; we know he tell them come; he betray tower to them."

Eric stammered: "No—no! It's a—a lie; I didn't!" His voice rose to a scream. He was pitiable.

Atsu went on relentlessly: "I myself stand in open door, see you call enemy station. You have silence unit in operation."

Eric stared at his accuser with frightened gaze. He opened his mouth to deny it, met the yellow man's mocking eyes, and choked off into inaudible mouthings.

"You see, friend Neville, how it is? Let us waste no time on this scoundrel. Let us kill him, as he deserves."

The wretched man slumped to his knees. He was frantic with terror. "Mercy!" he implored. "Let me live.

I will tell you everything. It is true I——"

Hugh caught the swift movement of Atsu's hand. He swiveled, leaped for the driving steel. A quick jerking twist and the long, keen-bladed knife went thudding to the floor. The yellow man ground out an unintelligible oath and rocked back on his heels, nursing a sprained wrist.

"None of that!" Hugh said sharply. "What the devil do you mean by trying cold-blooded murder?"

Atsu wiped his face of all emotion. "So sorry," he said blandly. "But righteous anger swept me away."

Hugh swung back on the cowering wretch. "Let's have it."

The words tumbled eagerly: "It happened yesterday. He contacted me, when I was alone. He made dazzling offers if I would open the tower to his forces. He promised that no harm would come to any one. In a moment of folly I yielded. But during the night, my conscience bothered me. I determined to back out, not to do it. When Benton's whistle called, and you were arrested, I felt that you knew something, and I became so frightened, I—I didn't know what I was doing. I called him, and—and the fleet is on its way. When I get the code signal, I'm to open the ports at all altitudes." Hugh gripped the still kneeling man's arm with a fierce grip. "The attack will take place when?"

"In thirty minutes."

Hugh flung him away. "Midcentral knew how to pick its dupes."

Eric sprawled against the desk. He lifted his bruised head. "Midcentral?" he echoed blankly. "I had nothing to do with Midcentral. It was the chancellor of Northcontinent who spoke to me. It was because Midcentral was in control of Tower No. 2 that I agreed. I felt they would force each other to a quick peace."

Hugh swerved on Atsu, but the yellow man forestalled him.

"So sorry," he said. "I must have mistaken the signal lenses. But difference, if any, unimportant. Must keep enemy out. One nation bad as another."

"Of course," Hugh agreed readily. But his glance flicked over the board. The signal lenses of the Pacific Tower and of Northcontinent's station were at opposite ends. He said nothing, however, and sprang to the controls.

He checked the signals with speed and efficiency. All the ports were closed. Eric lay on the floor where he had fallen, holding his head in his hands, groaning. Atsu hovered to one side, bland, inscrutable. He had wriggled nicely out of that. Let Neville pull the chestnuts out of the fire and burn his fingers in doing it. Then he, Atsu Mira, would act, even as he had done at Tower No. 2.

HUGH switched on the observation-rim telescopes, contacted them in slowly revolving series with a special visor screen. It was already dawn in the high stratosphere.

Far off, to the northwest, at the extreme limit of visibility, a cloud of black specks seemed moveless in the lower stratosphere.

Eric had told the truth. Northcontinent was hurtling to the attack.

Hugh swore fiercely. Atsu leaned forward with masked eagerness. At the same time he edged toward the fallen, forgotten knife. His plan was clear. Kill the two men in the room, wreck the communications board. Then to the key centers of the tower, to smash the delicate actuating apparatus. He would find them, he was sure.

He bent over to flick something off his shoe. When he arose, the knife was hidden in his wide-flaring sleeve. He moved on stealthy feet toward the unsuspecting scientist. He was almost behind his victim. Eric was sobbing quietly in the corner, still crumpled together.

Hugh reached over and threw a switch. The ravaged features of Christopher Benton turned full from the screen. He had not slept. His face twitched as he saw the occupants of the communications room.

Atsu snarled to himself, retreated a step. What did the fool mean by this?

The chief scientist jumped to his feet. His hand reached for the whistle hanging on a chain from his neck.

"Benton, don't touch that whistle," Hugh said rapidly. "Now I can explain. We have been betrayed—by Eric.

The fleet of Northcontinent is almost at the tower. Look at the other screen." Benton's hand clutched the whistle, stayed. His eyes went to the visioned screen, saw the dots. They were larger now. His eyes came back.

"You broke from your cell. You had confederates outside, then. Ah, Atsu Mira! I understand now. You've gained control of the board somehow, and you boast to me. You dare call Eric the traitor, but you——"

"Eric Mann, lift your head," Hugh interrupted. "Tell him the truth."

The miserable scientist raised himself on one arm, looked with shame-swept eyes at his chief, and said in a low voice: "It was I who betrayed you." Then he let his head fall again.

Benton staggered slightly, shocked, bewildered. Yet strangely there was a flicker of relief, of joy even.

"Hugh! I don't understand."

"We have no time. The fleet is approaching. Make sure all ports, the rim, the machinery, are manned by trustworthy men. There may be more backsliders in the ranks."

The chief scientist pulled himself together. His whistle shrilled. The sound vibrated through every nook and cranny of the vast tower, carried through the cunningly constructed sound tubes. Even in the communications room it blasted its warning.

Men sprang from sleep, darted into the corridors, confused, querying. It was the second summons of a thrill-packed night.

Hugh's eyes flicked back to the televisor screen. The automatic rotation of the telescopes had clicked past the northern view, and swept now over the southeastern area. Water foamed at the bottom of the screen, but high above, coming swiftly over the Red Sea, was another fleet, great, grim, battle planes! "Midcentral!" he cried.

Red swastikas emblazoned the under wings. The truth flamed through him and he turned sharply. He was not fast enough. Atsu struck.

The blade, poised for the broad of his back, sliced through the left shoulder, crunched against bone. Hugh fell backward, hitting his head against the hard floor. The blood pulsed from the wound, dripped down his side. He was motionless, eyes wide-staring.

Atsu balanced a moment, watching Eric. But the erstwhile communications chief was still sprawled as he had been flung, moaning softly. With a contemptuous gesture, the yellow man switched on the direction finder, sent a tight beam hurtling toward the approaching planes on the southeastern visor screen.

"Stillwig!" The code word.

"K-4! In complete control of tower, excellency."

"Splendid! Open ports for our entrance."

"Not yet. Northcontinent's fleet is moving on the tower from the northwest. Your paths intersect in five minutes."

There was silence. Then: "Can you turn off the power? The enemy fleet will crash."

"And you?"

"We're riding the beam from Tower No. 2."

"So sorry, excellency. The scientists are on guard. The key positions are protected. I dare not stir from the communications room."

"Very well. We shall fight it out then. We have the larger fleet. As soon as Northcontinent crashes, open the ports."

"Yes, excellency."

Atsu snapped off all connections except the tight beam and the telescopic screen. But not before the mid-belt lens had flared, and Benton's startled features flashed on the local screen. Then they were gone.