RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

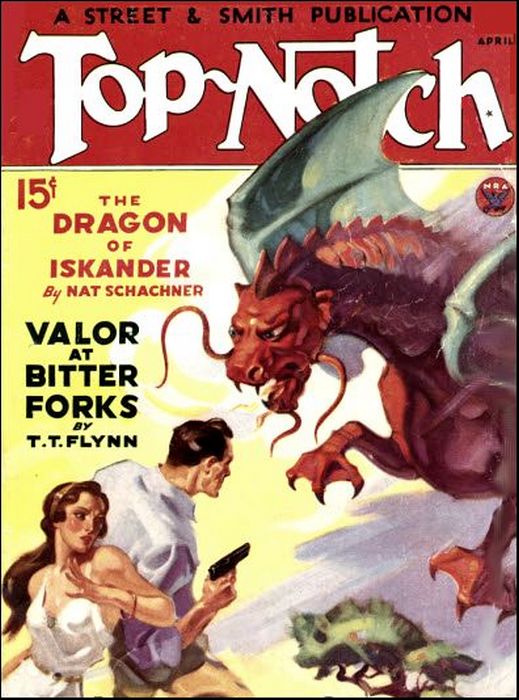

Top-Notch, April 1934, with "The Dragon Of Iskander"

IT was long past midnight. The expedition lay encamped in a gigantic hollow of moving sand. A blood-red moon drooped over the mountains. The Kazak guards drowsed.

Ambar Khan grunted, muttered fearfully to himself. He did not like the Gobi. It was a place bewitched. He paced steadily back and forth, his rifle thudding softly before him.

To the west stretched the fabulous T'ien Shan, the Heavenly Mountains, the Snow Mountains, the Ten-Thousand li East-by-South Mountains, grim ramparts of Chinese Turkestan. The expiring moon impaled itself on a splintered peak. Something moved across its face swiftly.

Ambar Khan groaned, called on Allah, and stared again. The moon plunged into darkness, but the thing glowed by its own light. Down from the mountains it swooped, breathing fire and flame. Soft, roaring sounds sped before the monster. Ambar Khan caught a glimpse of lashing tail, gigantic claws, and elongated neck, and shrieked. He knew now what it was. A rifle shot hushed the murmurings of the Gobi. The next instant Ambar Khan groveled in the sand, blinded with terror.

Owen Crawford sprang out of the deep Sleep of exhaustion, every sense alert. The camp was in an uproar. Camels grunted and squealed and kicked at their hobblings, dogs yelped in short, excited barks; the Chinese camel drivers and pack porters wailed in unison.

"Bandits!" thought Crawford, and flung himself out of the tent, gun in hand.

Behind him padded his personal servant, Aaron, man of Tientsin, fat and over forty. His feet were bare, his breathing asthmatic, his walk a waddle, but his heart was valiant, and the gun in his pudgy fingers did not waver.

Outside, the blackness of the night was hideous with noise and movement. The singsong wail of the Chinese clamored high above the deeper gutturals of the Kazaks. Crawford raised his voice in a shout, to bring swift order, to organize against the invisible enemy.

A tall figure loomed to one side. "This is no attack," said Andros Theramenes, Greek by race, assistant archaeologist.

Another figure rose to the left.

"Nay, it is worse," Kang Chou, Chinese governor of Turkestan, agreed.

"Then what——" Crawford began, and gasped into silence. He, too, had seen it!

The monster was dropping fast. A bullet would have lagged behind. Down it came upon the camp with a terrifying swoosh. Crawford staggered back and swore involuntarily; his gun hung loose from nerveless fingers. It was hideous, impossible, a myth out of the fabulous past!

Down, down it came, a thing of sinuous, scaly body, with a glittering metallic tail that lashed the air into little whirlwinds. The huge reptilian head glared balefully out of two, round, unwinking orbs; great claws, affixed to short, extended legs, were like steel hooks ready to rend and slash. Fire vomited forth from red-pitted nostrils, from yawning bloody mouth, from leathern wings and tail. The frightful din of its passage muted the clamor of the camp.

Then it struck.

The great claws curved around the canvas of the tent Crawford had just quitted, swept it under the hideous bosom, and the beast was up again, a meteoric monster of fire, homing for the Heavenly Mountains.

CRAWFORD shot once, but the bullet was futile. Already the winged anachronism was a rapidly diminishing swath in the blackness, hurtling over the gloom-shrouded peaks. In seconds it was gone, quenched, as though it had never been.

The camel drivers cried out together in one loud voice, "The Holy Dragon," and rose tremblingly to care for the plunging, snorting animals.

"Lights!" called Crawford.

An electric torch was thrust into his hand. He flicked it into an oval of white radiance. Aaron, his servant, showed ghastly white, muttering inaudible prayers to his ancestors; Theramenes, tall and reddish-haired like the northern Greeks, betrayed no change in his ordinarily reserved and calm demeanor. Only his eyes glittered strangely.

"It was your tent the Dragon struck at," he said slowly. "Had you not fortunately run out——" He stopped and shrugged his shoulders suggestively.

"There would have been a new leader to this expedition," Crawford said grimly. He flashed the torch suddenly full on the Chinese governor. "Kang Chou, what do you know about this?"

The habitual mask of centuries overlaid the Oriental features, in which there was no trace of fright. "You have heard the camel drivers," he remarked courteously. "It was the Holy Dragon, the guardian spirit of the T'ien Shan. Beyond the memory of our ancestors has it dwelt in the inaccessible mountains; so runs the childish patter of the people. It swoops from its nest on occasion; its prey always a vigorous, comely woman, a female child, a young camel, a sheep. The natives worship it."

Crawford stared. "Never by chance a man or man child?"

"Never."

The American archaeologist looked at the bland governor thoughtfully. It was passing strange; this untoward interest of the Chinese in his excavations; the unheralded visit of the governor to his camp; the weird visitation of the Dragon. What was the connection; what did the fiery monster portend? The blow, as Theramenes had pointed out, had manifestly been struck at him.

"Andros," he ordered, "keep an eye on the tents. I want to see what damage's been done."

His assistant said quietly: "I shall watch in the proper places." That meant he had understood. The Chinese governor and his retinue were to bear close supervision.

Crawford toured the encampment quickly, efficiently. Already lanterns were bobbing back and forth, throwing flickering yellow blobs of light on the confusion. The damage, aside from the complete loss of his tent, was not great. Two camels had broken their hobbles and were gone to the desert. A man had fallen flat over a peg and broken a leg. But Ambar Khan, who had first seen the Dragon and raised the alarm, was dead. His arms were outstretched, his face hidden in the sand. Crawford turned him over and swore fiercely. The man's throat was slit neatly from ear to ear. The blood was not yet congealed. He had been murdered.

OWEN CRAWFORD strode back and forth with quick, nervous strides in the narrow confines of Theramenes' tent. His lean, weathered jaw was out-thrust, his gray eyes snapped with belligerent fires past a bold aquiline nose. He talked rapidly to the Greek archaeologist, while Aaron, placid once more, brewed fragrant tea over an alcohol lamp.

"The expedition must go on," Crawford declared. "Some one, something, is trying to stop us. Poor Ambar Khan paid the penalty for warning us in time."

Theramenes shrugged. "Why?" he asked in his perfect, yet slightly slurred, English. "You have permission from the Canton authorities for your excavations. We've already found a buried city on the edge of the desert, showing Hellenistic influences, but the Chinese never bother about relics alien to themselves."

Crawford spun around. "Exactly! That's what makes Kang Chou's interest the more strange. There's been a leak. He knows my real plans."

There was a slight sneer to the Greek. "Still harping on that theme? Alexander never marched this far north. He never saw the Heavenly Mountains."

"So say the history books. But I've traced his passage step by step. Somewhere in the T'ien Shan I'll find the evidence." Crawford paused, looked a moment curiously at his assistant. "You are a Macedonian yourself, aren't you?"

Theramenes' laugh was a bit forced. "Why, yes. Why do you ask?"

"No particular reason," Crawford answered.

He had never quite warmed up to the Greek. All his plans had been for a solo exploration, but wires had been pulled at the last minute, and Theramenes was attached to the expedition. It had been merely a polite request, of course, but the request of the American Museum had all the force of a command. They footed the bills. Theramenes knew his work thoroughly, Crawford was compelled to admit. His intuitive flashes concerning the early Greek civilization in Central Asia were sometimes little short of marvelous. But Crawford felt something was held back; some queer, outlandish strain in the man not attributable alone to difference in race.

The Greek seemed anxious to change the subject. "What do you make of that Dragon?" he asked.

Crawford's face went sober. "I don't know," be admitted. "We saw it, all of us. It took my tent; that couldn't have been dreamed. A Dragon in the twentieth century! It sounds impossible."

"It isn't." There was a deadly seriousness in the Greek's voice that the American had never noted before. "There have been legends for centuries about that Dragon, about far more horrible things in the T'ien Shan. We've seen the one; let us credit the others. Let us turn back before it is too late. Once in the Heavenly Mountains, we shall never return."

"You are at liberty to resign from the expedition," Crawford said coldly. "I intend going on."

His assistant's eyes flashed dangerously. They were not the eyes of a coward. "Very well, then. I do not intend to resign. You are the leader, and I obey."

Crawford said: "We start in an hour."

THE evening shadows were lengthening as the little party toiled over Dead Mongol Pass. The snow lay many feet deep on the treacherous road. On the other side was Chinese Turkestan, but Crawford was looking for a certain narrow gorge that led to the north, deeper into the Heavenly Mountains. No one had ever ventured far in that direction; Chinese and Kazaks both had frightful tales of what lay beyond. The Dragon had disappeared to the north.

The expedition was encamped at the foot of Dead Mongol Pass, waiting for their return. With Crawford on this last exploration were Theramenes and Aaron; then another, an unwelcomed, unbidden member, Kang Chou, governor of Turkestan, had blandly announced his intention of proceeding with them. Crawford fumed and stormed, and gave in. The governor had powers; if he wished, he could tear up the Canton documents. He came alone; threats of death could not force his soldiers to accompany him into the dreaded mountains.

Up to the very top of the bleak, windswept pass they toiled, with two weeks' provisions on their backs, and rifles on their shoulders. There they found the little gorge they had been told of. It was but a rift in the rock, barely six feet wide, and angling to the north.

Crawford plunged in without hesitation. The path zigzagged, but always to the north, and always upward. Night found them still in its narrow confines, its walls a thousand feet high. Shivering with cold, they managed to make a fire of gnarled roots and rotted boughs that the storms had swept over the cliffs, and went to sleep. All night long the wind howled and bit with northern fury; and ghosts gibbered and shrieked.

In the morning they started again. Theramenes was even more silent than his wont, but his stride was tireless and his swing that of a born mountaineer. Aaron struggled and. puffed, and the fat loosened on him great beads of sweat. Kang Chou walked easily, which was strange for a pampered Chinese lord, and the bland smile never left his face. All that day they went on and on, the gorge never widening, never narrowing, the high walls towering in shivering gloom.

Then, as the slanting rays across the narrow sky above proved evening almost at hand, the gorge suddenly tightened. Five feet, four, three, barely room for a rotund body like Aaron's to squeeze through; then closure and jagged granite to interminable heights. Pitchy blackness slowly infolded them; a mocking star beamed faintly in the inverted depths above.

Theramenes broke the stunned silence. They could not see his face, but to Crawford's supersensitive ears there was faint mockery, triumph, in the slurred accents.

"We have reached the end of a mad venture. The gorge has no outlet. Let us turn back."

"Yes, master, now, at once!" cried Aaron. "The demons will be coming out soon."

Kang Chou's voice floated suavely. Was there regret in it? "I had thought—I was mistaken. It must be another road. We must start again—from Dead Mongol Pass."

Crawford bit his lips at the collapse of his plans, looked up at the black, forbidding mass. Had the dying Kazak lied, or wandered in delirium?

"We will camp here," he assented dully, "and go back in the morning."

"We would but waste time," said Kang Chou. "The road is safe, and it is early. We can travel several li before making camp."

"No," said Crawford positively. "We stop here."

He tripped the trigger of the flash. As the white light sprang forth, something thrust at him violently. The torch clattered stonily to the ground, and a hard, unyielding substance smashed against the side of his head.

Crawford dropped, stunned from the blow. There was a dull roaring in his ears, and dim echoes of shuffling feet and startled cries. His hand flung out to protect himself, and came in contact with the smooth, round cylinder of the flash. His fingers closed convulsively, seeking the trigger.

The confusion increased, the cries redoubled. Some one caught at his hand, tried to bend it back. Just at that moment the trigger clicked, and the opposite rock glowed into being. The invisible hand abruptly let go.

Aaron caught at the flash, turned it anxiously on his master.

"You all right? A rock he almost kill you."

Crawford's gaze slid past the frightened fatness of his servant, saw both Kang and Theramenes bending over him with equal anxiety on their countenances.

"A close shave!" said the Greek. "Lucky it was a glancing blow. The side of your head is bruised. A bit higher, and the rock would have hit square."

Kang Chou said: "Praise to your ancestors! A dislodged stone is a terrible thing in the mountains."

Crawford rose unsteadily to his feet. He was a bit dizzy. He felt his head. There was a lump on his right temple; it was sore to the touch, but there was no blood.

"I'm all right," he said. It was no rock that had grappled with him for the torch. What was behind all this? Who was ready to commit murder to prevent him from continuing his search? Kang Chou? Theramenes? Aaron? Some one else, who had preceded him, hidden in the clefts in waiting?

He took the flash from his servant, swung its wide beam carefully over the ground. There was dead silence behind him. Nothing showed, only the rubble-strewn floor of the gorge, the gigantic walls hemming him in on three sides. Not a break in the rough, hewn surfaces, not a recess in which an assailant could hide.

THE silence tensed. Some instinct made Crawford swing the light upward. The white radiance traveled up the blockading cliff, jerked to a sudden halt. The American sucked in his breath sharply. Some ten feet up the smooth surface, a black hole yawned.

"Stand against the rock, you fat crow," he said to Aaron.

The servant's face was tragic, but he obeyed. The American vaulted lightly to his shoulders, swayed a moment, and caught at the lip of the recess. Theramenes held the light steady.

Crawford pulled himself up and disappeared. They waited anxiously below. In some seconds his head and shoulders appeared.

"It's a cave, all right!" he shouted down. "How far back it goes, I don't know. The torch will show that. Come on, you fellows; I'll give you a hand."

Crawford played the flash around. They were in a cavern; the ceiling some dozen feet up, the width not over twenty, but the long stream of the light did not show any termination to the corridor.

"We will explore it at dawn," said Theramenes. His voice was excited; his usual calm was gone.

"We'll explore now," Crawford told him. "Daylight won't make any difference in here."

"But——"

"Come on," said his chief.

And the four of them moved cautiously forward, rifles ready for instant action. The subterranean corridor wound on interminably, the questing beam disclosing only dripping, icy walls.

Then suddenly it opened up—a vast, vaulted chamber in which the puny gleam lost itself in the immensities. Crawford called a halt. Which way now?

Theramenes pointed to the left, Kang Chou was equally positive the road was to the right, so Crawford forged straight ahead. There was no talk; each had an uneasy feeling of presences in the great chamber, of mocking figures watching their slow progress. The thin light but accentuated the threatening darkness.

Aaron clutched at his master, uttering a little strangled cry. "Look, look ahead! The big devil himself!"

The party came to a quick halt. There, before them, was the end of the vast cavern—a perpendicular straight wall of rock. But the steady beam disclosed legs, gigantic Cyclopean legs, straddled at a wide angle, braced against the granite. Up went the light, and a huge torso sprang into view, massive, powerfully muscular. Up and up, until at the extreme limits of illumination, a face stared down at the startled explorers; calm, majestic in its majesty, a giant of ancient times, amused at the puny mortals who had dared penetrate his secrets.

Crawford's eager laugh broke the spell. "A statue!" he cried out, half in relief, half in excitement. Awe crept into his voice as he examined the great figure. "Theramenes, do you recognize it?"

The Greek shook his head. He was beyond words.

"Man, it's a replica of the Colossus of Rhodes. Exact in every detail, as the dimensions have come down to us. Now do you believe my theory? Alexander and his troops were in this cavern, sculptured that form."

Theramenes examined the Colossus. "You are right," he said at last. "It is authentic. Greeks only could have done that."

"There is an opening between the legs," remarked Kang Chou, unimpressed by the looming giant. He had other matters in mind.

It was narrow; barely room for a man of Aaron's girth, and the stars shone dimly in the depths.

Some urge made Aaron dart forward. He thrust his head and shoulders through, drank in the cool night air. A whistle resounded in the cavern, a peculiar shrill piping that sent echoes reverberating.

"What is that?" Crawford asked, startled.

There was no answer. The next instant Aaron screamed; there was a muted roaring, and his body was jerked violently through the opening.

CRAWFORD rushed forward, too late. A quick lunge just missed the last disappearing foot, and he caught at the jutting side only in time to save himself from plunging into tremendous depths. Far away, blazing a cometary path through the black night, was the Holy Dragon. Long streamers of fire trailed rearward. Then it was swallowed up, gone. Of Aaron there was no trace.

"What happened?" Kang Chou's soft unemotional voice sounded unpleasantly in the American's ears.

Crawford did not answer. Instead his gaze shifted downward. His body stiffened, an ejaculation of surprise tore itself out of his throat. The two men crowded eagerly over his shoulder, but there was nothing to see. A white mist swirled and billowed in great leaps, filling the great depression in the twinkling of an eye—a sea of smoke that disclosed nothing.

Gone was Kang Chou's Chinese impassivity. He literally clawed at Crawford's shoulder. "What was it you saw?" he screamed. "Tell me—tell me what——"

Theramenes glowered in silence. His brow was black in the electric flash, his lips compressed.

Crawford turned. His face was like granite, grimly hard. He shook off the grasping hand. "I? I saw nothing, Kang Chou."

"You lie, foreign devil!" screeched the Chinese governor, dancing in rage. "You saw, and you think to keep the secret. Tell me, or——"

An automatic appeared in the yellow hand, slipped out of the ample sleeve. Theramenes moved with silent speed. A wrist of steel grasped the well-fleshed hand, wrenched. A howl of pain, and the gun made a clangor on the stony floor.

Crawford said, "Thanks!" and did not move. He had disdained to duck, or switch off the steady flash in his hand.

Kang Chou glared at the two archaeologists, holding his arm. Then the mask slipped back into place. He bowed low.

"I was hasty," he said suavely. "You have seen—nothing."

It was Theramenes who asked: "What happened to Aaron? Did he fall?"

Crawford grimaced with pain. The fat, asthmatic servant had been dear to him. "The Holy Dragon took him."

The Greek made a gesture of commiseration. "What now?"

"We wait until morning, and then start——"

Sleep was fitful in the black, damp cave. Watches were divided, but there was little slumber Once Crawford thought he heard stealthy movement, but quick illumination of the torch showed nothing except Theramenes leaning on his rifle on guard, and Kang, a little to one side, snoring uneasily. After that, there was no further noise.

AT the first hint of dawn, the trio crowded between the great sculptured legs. They looked out on a long, deep valley, hemmed in on all four sides by towering, precipitous mountains, tumbling range on range as far as the eye could see. The Heavenly Mountains, the Ten-Thousand li East-by-South Mountains, had guarded their secret well. And downward—it was the Greek who grunted. For the heavy clouds lay like a waveless ocean. The bottom of the valley was invisible.

Crawford wrinkled his brows. There was black bitterness in his heart. Aaron was dead, and must be avenged.

"We are going down," he said.

"How?" asked the governor. His eagerness was carefully restrained. No mention was made of his outburst of the night.

"There is a ledge," Crawford explained. "It slants down into the mist. Room enough for one man at a time, if we are careful."

"Shall we wait for the mist to clear?" asked Theramenes.

"No. I know these valley clouds. They last for days at a time."

Without further ado they prepared for the perilous descent. Packs were tightened, rifles lashed to keep both hands free. A mouthful of tinned food, a swig of warmish water from canteens, and they were ready.

Crawford led the way, lowering himself carefully from the orifice. It was less than five feet to the ledge. On one side was a perpendicular wall, lost in the immensities above; on the other a sheer precipice, lost in the immensities below. The slant of the path was steep, but negotiable.

The American spoke in low tones to his assistant. He did not want Kang to hear.

"This path is artificial. See how smooth it is, how the stone is hewn."

"I've already noticed it," the Greek answered quietly.

Slowly, cautiously, they edged their way downward. Two thousand feet, and the white mist enveloped them. They were ghosts flitting noiselessly on insubstantial air. Even their voices sounded hollow. On and on—for hours it seemed—edging their way along, grasping the solid wall for safety, avoiding the unseen outer edge. A world of smoke, of writhing forms, of lost souls. No sign of an ending, no sign of a break in the clammy clouds. Down, and down, until to the bewildered explorers it seemed as if earth's center itself should have been reached.

Momentarily the mist parted, and closed as swiftly. Crawford swerved, but not fast enough. The cry of warning smothered in his throat. A clinging heavy cloth enveloped his head, sinewy arms held him immovable. He tried to struggle, but a cloying exudence from the bag stole into his brain, drowsed him into numbing calm. Behind him he heard a choked-off yell and then white silence.

CRAWFORD awoke with a dark, furry taste in his mouth and a drugged throbbing in his head. For a moment he had difficulty in focusing his thoughts—then he remembered. The second vision he had had at the bottom of the valley, the swift noiseless attack. He opened his eyes. He was in a huge chamber, hewn with infinite pains out of solid rock. Damp dripped slimily from encrusted walls, and a dim light filtered through from a tiny opening high on one side.

A dungeon, thought Crawford, and tried to rise. Something retarded his movements, made metallic sounds. He looked down. There were chains encircling his legs, holding him hobbled. He examined them with interest The metal was bronze, exquisitely worked, and chased in a running design that caused Crawford to forget his predicament in an involuntary whistle of astonishment.

As if his low-pursed whistle were a signal, a door opened silently at the farther end of the dungeon, and a girl entered. The archaeologist forgot his chains in the greater astonishment. She was dressed in pure white; a single garment caught at the waist with a bronze pin and falling in graceful folds around small, sandaled feet.

In her hands she held a tray of bronze, with heaped food and a goblet of dark-red wine. But it was her face that held Crawford's attention. Those classic features, that straight, chiseled nose, the harmonious brow with the thick plaits of warm brown hair low on the forehead, the firm, full lips—how strangely familiar! Where had he seen this girl, or some one like her, before?

Then she smiled as she moved noiselessly forward, and the red lips parted slightly. That was it—he remembered now. A small, Greek figurine of white marble, representing Artemis the Huntress, that he had discovered near Antioch on a former expedition.

The girl placed the tray in front of him, straightened, beckoned to him to eat, and was gliding away. Crawford came out of his semi-stupor to call quickly:

"Wait a minute! I want to talk to you."

She turned at the sound of his voice. She shook her head with a puzzled air and said nothing.

He tried again; this time in Chinese. It worked no better. Mongol, Kazak—to no effect. The girl was frowning now and moved away again.

In desperation, afraid almost of its effect, knowing it to be impossible, Crawford spoke rapidly—in Greek. The girl paused irresolutely, turned half a classic profile in his direction. Her brow was furrowed with perplexity. It was obvious that the sounds awoke some echo in her, and it was also obvious that they were unintelligible.

Crawford fell back exhausted. He was almost glad she had not understood. It would have been too bizarre, too fantastic for a hard-working, practical archaeologist of the sober twentieth century.

She was going now, the door was open; when the blinding answer burst like a time bomb in his mind. He shouted to catch her swift attention, in unaccustomed syllables that resounded like the surge of the open ocean.

"Mistress, do not go. You must tell me where I am and who you are."

This time it was not modern Greek, the clipped, degraded speech of a fallen race, but the pure, ancient tongue, briny with Attic salt, the speech of Homer and Sophocles, of Sappho and Pindar.

The effect was startling. The girl whirled around, her eyes wide open, a little liquid cry in her throat. Her rounded bosom rose and fell with the vehemence of her feelings. She started to speak, and checked herself forcibly.

Crawford felt he was dreaming, that the effects of the drug had not yet worn off. The attempt at Greek had been sheer insanity, an intuitive, unreasoning flash. What was a girl, dressed in the ancient Greek mode, wearing the ancient Greek costume, and responding to the sound of the pure Greek tongue, doing in the T'ien Shan ramparts between Turkestan and the Black Gobi? What connection did she have with the Holy Dragon? Questions that clamored for immediate answer.

"You understand me?" he queried haltingly. Hardly ever had he used the Attic Greek for speech.

She nodded, gazing at him with a queer compound of fear and curiosity.

"Why, then, do you not answer?"

She shook her head in a decided negative.

"You are not permitted?"

To that she smiled again.

Crawford considered. "Your name at least," he implored.

The smile widened to a little tinkling laugh. "Aspasia!" she cried in a ripple of sound, and fled.

The door closed silently behind her, and the archaeologist was alone with his chains and his food.

The meat was roast mutton, prepared with spices; the bread of a curious oaten compound; there was a handful of figs, and the wine was sweet and heady.

When he had eaten and drunk his fill, he threw himself back against the straw-covered, stone pallet to which he was chained. He must think this thing out. From the first appearance of the Holy Dragon, the glimpse of the white i temple withheld from his companions, to the appearance of Aspasia, each adventure seemed more astounding, more incredible than the preceding one. His companions! Poor Aaron was dead, a victim to the terrible Dragon; Theramenes and Kang Chou—what had happened to them? Dead, perhaps, even as he would be soon. Crawford had no illusions about his fate; whoever it was who inhabited this incredible valley would never let him return alive to inform the outside world of what he had seen.

He examined his bonds. They were strongly linked, and so skillfully wound, it was impossible to wriggle out. A curiously intricate lock held them fast to a bronze ring imbedded in the rock. Escape just now was out of the question.

HOURS passed. He must have slept, for the tramp of metal-shod feet thudded down upon him unawares. Two men stood over him; tall, large-limbed men, sheathed in bronze armor, helmeted, with spears taller than them-! selves resting with the butt ends on the ground. The fairer-haired of the two bent over and placed a key in the lock of the American's chains. A grinding noise, and the bands fell away.

The darker warrior upended his spear, pricked Crawford roughly with the point. The archaeologist staggered to his feet, irritation at the brutal treatment lost in the amazement of seeing two exact replicas of ancient hoplites in the flesh.

The fair man made pantomime for him to go forward; the dark and crueller one urged him on with prods of the spear. Through the open door they marched, into a long corridor, rock-hewn, and illuminated with a yellowish glow from no visible source. The metal sandals of the guards clattered as they walked. On either side Crawford could see solid, timbered doors, leading to other chambers, no doubt. But the guards urged him on.

At the end of the corridor was a door. The fair one opened it. They stepped out into sunshine and warmth; from the position of the sun over the mile-high mountain walls, it was not much past noon.

The archaeologist cast eager glances to right and left as he was pushed stumbling along. There was no mist in the valley now. At the farther end stood the temple he had first glimpsed from the mouth of the cave before the swirling mist hid it from view. It was a noble structure, in the Doric manner. White gleaming columns, unornamented, evenly spaced to uphold a flat marble roof. But there was more, far more.

The valley was approximately five miles long and three miles wide. A stream meandered down the middle, terminating in a lake at the opposite end from the temple. In between were fertile fields with waving corn, cattle peacefully grazing, and sheep. Hundreds of people were at work in the fields; men, women, and children. They straightened up to stare curiously as Crawford was marched past.

All were dressed in the flowing graceful Greek garments; their features ranged from purest classic Greek to a mongrel mixture with slanted eyes and high, yellowish cheek bones. Here and there stood a woman, of unmixed Mongol blood, still with the terror of her capture in her fathomless eyes.

The archaeologist walked as in a dream; it was too much to digest at once. Their destination was obviously the temple. As they clanged over the marble approach, he managed to cast a hasty glance backward.

Two things caught his eye before the dark guard turned him roughly forward. One was the abode of his imprisonment. Purely Buddhist this. A rock settlement hewn out of living rock in terraces on the almost-perpendicular flank of the mountain. A ming-oi or House of a Thousand Rooms. The other was a strange-looking monster floating quietly on the waters of the far-distant lake.

Then he found himself walking through a forest of columns, past a great, sculptured figure, bearded, majestic, that Crawford immediately recognized as Jupiter Ammon, and out into an open court, before a throne.

The guards raised their spears high. As one they cried in ringing Greek:

"Hail, Alexander! Hail, Ammon's son!"

Crawford stood stock-still. A man sat on the throne, a man out of the past. Alexander the Great himself, grown old, if the medaled representations did not lie. The same commanding brow, the same stern expression and chiseled nose, the flowing locks, snow-white by now, peeping out of a plume-surmounted helmet; burnished armor on the still brawny chest, a gem-tipped spear grasped in the right hand. On either side were ranged soldiers, in full panoply of war, Macedonians, the front rank kneeling, spears extended, the second rank standing, longer spears bristling through. The ancient Macedonian phalanx!

The great temple rang with an anti-phonic response: "Hail, Alexander! Hail, Ammon's son!"

The figure on the throne spoke. His voice was harsh, commanding:

"Know, stranger, I am Alexander, he who conquered Tyre and Sidon, Darius and Porus. The world was at my feet, and shall be so again. Prostrate yourself, stranger, for I am divine."

Silence crept through the marble columns, yet Crawford remained erect.

Slowly he spoke, shattering the quiet, fumbling for the Greek:

"I know now what took place. Alexander led his troops to Samarkand. Thence he turned south, but a phalanx, raiders or deserters, wandered northward and were lost. Hostile tribes hemmed them in. Day and night they fought, until they found refuge in this valley. With them were captive native women; thus they lived and flourished through the ages, cut off from all mankind. You," he pointer! to the seated warrior, "are not Alexander. He died in Babylon. You are the son of an obscure captain of a phalanx."

For a moment there was a stunned lull. Not in two thousand years had Alexander been thus defied.

A voice carried unexpectedly from behind the throne. The voice was English, the tones amused, mocking: "You are right as usual, Owen Crawford. The man is an impostor, but his power is great. The doctrine is Pythagorean; one Alexander dies, his soul inhabits another."

Andros Theramenes, Greek archaeologist, assistant to the expedition of the American Museum, stepped out into full view.

The storm had already burst—a low growl from a hundred throats that sprang into a roar of beating sound, mingled with the clash of arms.

"Death! Death to the sacrilegious animal!"

The two guards held their spears pointed at the American's breast. Alexander had half risen from his seat, the corded veins knotting on his temples. The gem-tipped spear rose slowly. At the peak of the arc, the spears of the guards would plunge.

Crawford held himself balanced, ready to move with lightning speed. His plan of action was mapped. At the first drawing back of the spear held by the dark guard, he would lunge to one side, twist in a demi-volt, wrest it Out of his hands, and be through the entrance of the temple in a flash. After that——

It was not to prove necessary, however. Theramenes leaned familiarly over to the outraged Alexander, said something in his ear. The old Macedonian sank back in his throne, lowered the fateful spear.

"Let the stranger wait," he said. "We shall decide his destiny later. Ho! Bring in the man with the yellow face."

Crawford relaxed, exhaling with some effort. Death had stared him in the face, and passed him by—for the present. There was drama here, drama that required careful reading.

A LITTLE ripple of movement took place at the rear of the throne, that widened as Kang Chou was thrust forward, under guard. His silken jacket was torn, but his impassive smile was bland as ever. He stood before Alexander, betraying no astonishment at the strangeness of the scene. Nor did he betray by a flicker his recognition of Theramenes.

"Speak, yellow face! It is the divine Alexander who commands you to speak. For what reason did you dare penetrate our fastnesses? Fear you not the Holy Dragon?"

The Chinese governor moved not a muscle. He had not understood. Theramenes, himself with the slant eyes of an impure blood, hastened to translate.

Kang Chou heard him out and answered in his own tongue. Once more Theramenes translated.

"I had heard rumors of your august, all-powerful presence in the T'ien Shan," said the governor. "Your Holy Dragon is as a god to our folk in the outer land. I come to pay honor and tribute to the divine Iskander, and to offer an alliance. I am Kang Chou, governor and war lord of Turkestan. I, too, have many soldiers and fear not the government of Canton." His glittering eyes roved over the sturdy Macedonian warriors. "Together we can go far."

Alexander thrust back his head and laughed, a full-throated laugh.

"Ha! That is good! This yellow man from the outlands proposes affiance to me, Alexander, son of Jupiter Ammon, conqueror of the world!" His eye flashed with fanatic fires. "Know, yellow face, Alexander spurns all alliances; once more the world will tremble at the rush of his armies. The Macedonian phalanx is ready; ready to conquer as of old."

To Crawford, almost forgotten in the new turn of events, it seemed as if a flicker of annoyance passed rapidly over Theramenes countenance as he turned to translate.

Kang Chou listened attentively. This time his speech was vigorous, direct, without the customary Oriental circumlocutions.

"Tell the mid foci," he said, "together we can conquer, if not the world, at least all China. It is the Holy Dragon that I need. My plans are made. Without me he is helpless. Tell him if I do not return to Turfan, my generals have instructions. Five planes will bomb this valley out of existence?'

There was no perceptible pause as Theramenes turned and began his translation. Crawford strained his ears suddenly; was he hearing aright? For he had overheard the Chinese, and this was the Greek. Theramenes was saying smoothly:

"The yellow man professes himself overwhelmed at your magnificence. He wishes to apologize for his presumption and begs only that a humble place be made for him in your retinue so that he may serve divinity itself."

"That is better!" Alexander nodded with a self-satisfied air. "Perhaps we shall permit his worship. Take him out and see that he is guarded well."

The pseudo-archaeologist turned rapidly to Kang.

"Obey in all respects," he said in Chinese. "Myself shall come to talk with you later."

His face a mask, as though he had not heard, the governor was led out of the temple.

Theramenes swung around to Crawford. His eyes mocked the American, his voice hinted at a sneer. "This, divine Alexander, is the stranger I warned you of."

"Ah, yes, the man from beyond the western gates of Hercules. He who had surmised our secret."

"Yes. I learned of his plans in time. I managed to join his foolhardy expedition. Not for nothing have I made frequent journeys into the outland on the back of the Holy Dragon. He suspected nothing. Now he is delivered into your hands."

"You have done well, Theramenes. Alexander is pleased. Aspasia shall marry you; my command will be sufficient."

A crafty look crept into the assistant's face.

Crawford judged it time to intervene, before his mouth was stopped forever. He had been silently piecing the parts of the puzzle together; now the picture was tolerably clear.

"Beware, Alexander!" he cried out suddenly in a loud voice. "This man Theramenes meditates evil——"

Fast as he was, the pseudo-archaeologist was even faster. "Shut his sacrilegious mouth, guards!" he shouted in stentorian tones.

Brawny hands choked off further utterance. Crawford did not struggle.

"Take him to his dungeon," Theramenes ordered, "to await the commands of the divine Alexander."

The American was whirled roughly around, and dragged, rather than permitted to walk, through the valley. Back into the rock cell, locked into the chains, and the final bolting of the outer door, brought chilling realization that Theramenes would never now permit his freedom.

Crawford lay in the dim light on the moldy straw, cursing himself for a thick-witted, blundering fool. A few minutes of whole-hearted self-excoriation brought some measure of comfort, and he sat up. If only he could unlock or saw through the chains! He examined them once more, stared at the edge of the stone pallet. Given time and infinite patience the bronze might wear through by rubbing back and forth. But it meant days, and Crawford felt his fate would be decided within the day.

SUDDENLY his sharpened senses heard something; the soft, slow opening of the dungeon door. He crouched against the pallet, his chained legs dragging, determined to meet death fighting.

The door swung wider, and a figure glided in. Crawford barely choked off an exclamation. It was Aspasia, and her finger was to her lips in the ancient gesture for silence.

"Do not make a noise, if you wish to live," she said in low, urgent tones. "I trust you, stranger, more than I do Theramenes." Her features darkened. "My father commands me to marry him; I hate him; I fear his ways. The olive is not more bland, nor the serpent swifter to strike. I heard all in the audience chamber; I heard your accusation. Tell me more."

Crawford stared at the eager girl, her classic repose flushed into warm tints. Something stirred queerly within him; something more than the faint possibility of escape.

"There is not much more to tell," he stated quietly. "Theramenes deliberately mistranslated Kang Chou's threats when the proffered alliance was refused by your father; he whispered to the yellow man to wait for his talk. I am certain he meditates treachery."

Aspasia nodded vehemently. "I am sure of it. He is high in the councils of my father; there is no one he trusts more. It is he who was alone permitted to spy the outlands over years; it is he who has fed divine Alexander with thoughts of conquest. The outlands, he reports, are weak and ripe for the thunder of the phalanx."

Crawford laughed shortly. "Therein he lies," he told the girl. "Mighty as the Macedonians are, they are but a drop in the ocean of humanity. There is some other reason for his urging."

Aspasia flushed. "He is ambitious," she said unwillingly. "Often has he promised me a throne were I but his mate."

"Find some way to loose my chains," Crawford urged. "There is no time to be lost."

"I brought a key with me," the girl acknowledged, and bent over.

So intent were they that the opening of the door roused no suspicion.

"Hold!" commanded a cold voice. "Move once, and die."

Aspasia started to her feet with a little cry; Crawford jerked at his chains fruitlessly.

Theramenes stood in the doorway, a spear poised for throwing. Next him stood Kang Chou, the snout of a revolver steady in his yellow hand.

The pseudo-archaeologist smiled unpleasantly. "Your Oriental wisdom is most subtle, Kang Chou. I foresee great deeds for our alliance. We are just in time."

The Chinese governor smiled softly. "Drop the key—over here." He pointed with the gun.

The words were not understood, but the gesture was. Aspasia threw over the key and straightened up, her eyes flashing with ancient hauteur.

"What is the meaning of this?" she demanded.

Theramenes grinned. "The very question I would ask you. Think what your father, divine Alexander, would say to his daughter freeing a prisoner."

A wild hope flashed through her.

"Take me to him, then. He shall be judge."

"Not so fast!" he warned, and shut the door. His easy mockery changed to cold, wintry fury. "I heard your speech with this outlander. You will be given no chance to betray us. You remain my prisoner until——"

"Until what?" she asked.

"Until we are through," he ended cryptically.

Crawford said in deadly tones. "Listen to me, Theramenes. You harm Aspasia the least bit, and you sign your death warrant."

The Greek raised his eyebrows mockingly. "Threats?" he sneered. "From a prisoner, whose fate is already decided! Pray, Owen Crawford, to whatever gods you sacrifice to, for you have not long to live."

He raised the spear by the middle, hefted it once to test its balance. Aspasia gave a cry and threw herself forward. Theramenes brushed her aside with a quick heave of a powerful arm, into the close grasp of Kang Chou. Crawford ground his teeth in silence and strained at his bonds.

The spear was raised again. There was death in the backward movement of the hand. The muscles tensed for the quick heave. Aspasia screamed once.

The door banged violently open. Theramenes whirled, the spear darting for the thrust.

"Hold, mighty Theramenes!"

AN armored warrior plunged into the room, his face suffused with fast running, his breath whistling in stertorous pants. It was the dark-haired guard, the brutal one.

The Greek stayed his arm. "What is it, Nicias?" he demanded, thunder-browed.

Nicias leaned a moment against the damp rock. "We are discovered," he gasped at last.

Theramenes took a step forward, shook the bearer of the ill news furiously. "You lie! Who has betrayed us?"

Nicias cowered away from him. "I do not know," he cried. "But Alexander is even now gathering the phalanges. I received orders; I am thought loyal. At the first opportunity I fled, to warn you. Master, what shall we do?"

Terror was written large on the face of the wretch. Alexander's vengeance was apt to be lightning swift.

"Peace, fool!" commanded Theramenes. "If only——"

Aspasia said exultingly. "My father is still the divine Alexander. He overheard your speech with the yellow man. He learned the barbarous language secretly from a captive woman. His vengeance will be terrible."

Theramenes' furrowed brows cleared instantly.

"Thanks, Aspasia, for your explanation," he mocked. "Then Alexander knows very little; knows nothing of the Dragon. Quick, Kang Chou, we have not a moment to lose. The time is but hastened, that is all. You, Nicias, bind

Aspasia. bolt the door, and follow us. We need every man. Your life depends on strict obedience."

With that he darted out of the door, the Chinese governor at his heels.

Nicias drew out from his tunic thin, flexible bronze links, and fastened the unresisting girl with the skill of long experience to a firmly imbedded ring on the opposite wall from Crawford. At the door he grinned cruelly at his two captives, slammed it shut. Their straining ears heard the sound of bolts being shot, the retreating clatter of the metal sandals; then there was silence.

Crawford gave another ineffectual heave and stared across at Aspasia. "What," he asked, "is the Holy Dragon?"

The girl shuddered against the dampness of the wall. "I do not know," she admitted, "except that it is a terrible monster. Only Alexander himself and Theramenes knows the secret of governing it—and a few men sworn to silence on penalty of death."

"How strong is your father?" Crawford inquired irrelevantly.

The girl straightened proudly. "He is the mighty, the divine Alexander. He has lived two thousand years; the wisdom of the Greeks is his; he will crush the revolt as though it were a fly under a catapult."

"Does she really believe that nonsense?" the American wondered, and carefully avoided pursuing it further.

"But his phalanges are honeycombed with treachery," he argued aloud. "And the Dragon."

All Aspasia's pride collapsed. "That is true," she said weakly. "Theramenes will use the Dragon. If only we were free!"

"If we're not free in the next several hours," he told her, "it will be too late." Already outside the thickness of their door they could hear muted shoutings, the clang of running feet. The ming-oi, the House of a Thousand Rooms, was emptying its occupants; whether as loyal men or as rebels, the captives had no means of determining.

The revolt had begun.

Crawford groaned and strained fruitlessly. The bronze links bit painfully into his flesh. He tried rubbing again:-! the stone edge, and succeeded only in rasping his legs into raw sores. There was fighting outside, and he was trussed up like a fowl for the slaughter, he and Aspasia.

The uproar grew; there was the faint noise of spear on shield. The opposing forces were locked in battle. Within the ming-in was silence.

The two captives stared hopelessly at each other.

It was Aspasia, as nearer to the door, who first heard the faint fumbling.

"What is that?" she cried.

The fumbling continued, as of some one inexpert with locks. Then the door swung open, slowly, an inch at a time. Crawford tensed; what new horror was coming through now?

THE girl saw it first, cried out in fright. She shrank back against the wall.

A figure inched slowly around the barricade; a tattered, torn, bleeding figure. Grime and blood were mingled in equal proportions on the paunchy form, great raking gashes Showed on flesh through slashed clothes.

The intruder turned slowly, and Crawford cried out:

"Aaron!"

The torn, broken figure thrust up its head, and grinned. "Master, my ancestors are good. I have found you." The American gaped at his servant, returned from the dead. "I thought the Dragon——"

Aaron shuddered. "The Dragon, he terrible! He dropped me in a pit." The man of Tientsin swayed and groped to the wall for support. He was weary and pain-stricken. "That pit, I never forget. Bones and rotting bodies, of others he dropped. It was deep I fell, but I was not killed. All night and day it took, I climbed out. I met a woman, woman of the Gobi. She took pity, hid me, told me where you prisoner."

Crawford flamed into action.

"The key, Aaron!" He pointed to the flung bit of bronze unregarded on the floor. "Open our chains; we have work to do."

The servant lumbered weakly to the key, picked it up, and with, many a groan, unlocked his master. At the girl he looked doubtfully, but unloosed her, too, while Crawford stamped to bring circulation back into his veins.

There was the old exultant ring to his voice. To Aspasia, in Greek, he said: "We shall fight for your father."

To Aaron, in English: "Have you still your gun?"

Aaron searched through the voluminous folds of his slashed fragments of clothes. Crawford watched with growing fear. His own gun had been taken away. At last the yellow hand emerged, bringing with it an automatic.

The American reached for it with a cry of joy. broke it open, spun the cylinders. It was fully loaded. He felt better now.

"The Dragon, Aaron! What was it?" Fear clouded the paunchy servant's eyes. "I did not see. Its claws caught me, held me tight in the long journey. I hung face downward; I could hear the noise of its nostrils, the flames of its breath were hot around me, but I saw it not."

Crawford made a gesture of annoyance. "Then we'll have to find out for ourselves. Come!"

Out of the door they went, into freedom, into deserted corridors. The ming-oi was empty. A door stood open to one side. Crawford glanced in. The next instant he was inside, and out again in a moment, with a spear.

He hefted it lovingly, thrust the automatic back to Aaron.

"Now we're both armed."

Then they were in the valley. It was a bloody, yet stirring picture that presented itself to them.

THE pleasant green fields were trampled down as if an army had beaten them with flails. The meandering stream was choked with corpses, through whose sprawling forms the water trickled and spread. Farther up, near the temple, a battle was in furious progress—opposing armies, almost equal in numbers, on whose bronze armor and gleaming shields the warm sun sparkled with almost unendurable brilliance.

The formation of the phalanges had been broken; it was confused, man-to-man fighting now. Spears thrust home, dipped, and rose again, reddened at the tip. Short, heavy swords hacked furiously down, cutting through helmets and shields and breastplates with shearing force. Shouts and ancient Greek battle cries mingled with the groans of the dying. No one yielded; the tide of battle ebbed and flowed; men died as they stood.

Grim war as only the Greeks once fought! Platea and Marathon arid Thermopylae. It was thrilling; it was magnificent!

Aspasia cried suddenly: "My father!" A tall figure, on whose shield a huge ruby gathered the rays of the sun and thrust them out again in blood-red waves, was in the very thick of the battle, laying about him with a short sword that cleared men out of his path like grain before the reaper.

"We must help him," she said, and started forward.

Crawford held her with a restraining arm. He was looking the other way, where the stream ended in the lake, on which the monster had floated earlier in the day.

It was still there, quiescent, its claws concealed, its long tail no longer lashing, the sun reflected from the metallic scales of its body, breathing no fire or smoke.

"That is where we are needed," Crawford said grimly. "Your father will have to take care of himself a while longer."

Spear swinging in hand, he started on the run. They had gone a hundred yards, when Crawford stopped short with a groan.

"Too late!" he said. "The Dragon has started."

The trio stared in silence.

The great beast was belching flame from every pore, its tail lashed into venomous life. Hie waters of the lake were tossed into foaming spume. The Dragon started to move, slowly at first, as the flames from its tail lengthened, and red-pitted eyes and widespread nostrils spewed smoky glares; then faster and faster, until with a bound it was in the air.

Higher and higher it fled, the great claws distended beneath as though seeking its prey; then it swerved, and like the wind was careering down the narrow valley, belching and roaring, straight for the tangled, locked armies.

Crawford jerked the girl suddenly toward him, thrust her behind the concealment of an overhang of the ming-oi.

"Down, Aaron!" he shouted, throwing himself flat. "It must not see us." Crouching in their precarious shelter, they watched with growing horror the tragedy that followed.

The fighting troops had seen by this time the swift approach of the monster. They were brave, these descendants of the Macedonians, as brave as any men of any age in the world, but they had been brought up to fear the mysterious Dragon. It had roared on occasion out of the valley and brought back terrified, tongue-tied captives; it had swooped on condemned criminals and dropped the m from heights into the terrible pit of the dead, but never had any except the few initiates seen the monster at close hand.

Now it was coining to attack—whom? Neither side knew; few of the rebels, chiefly of blood filtered through Kazak captives; were in the closest counsels of Theramenes.

So it was that at the sight of the plunging, fiery serpent of the air, the contending armies broke. Loyal troops and rebels alike threw away their arms in a wild stampede for safety.

The great Dragon swooped with the noise of a thousand thunderbolts. Straight down to within fifty feet of the plain, then it straightened out and fled parallel in huge concentric circles. Its belly opened into a veritable fountain of detonating flame that seared the ground to blackened stone and crisped the running men to char and ash.

Suddenly the belching ceased, and once more the Dragon swooped. Aspasia cried out in helpless horror. For the great claws extended and caught on a man—a man who remained on the field of battle, proudly erect, disdaining to run, a man whose shield was centered with a blood-red ruby.

The claws retracted and Alexander disappeared. The Dragon swept upward in its headlong flight, back in the direction of the lake.

"My father!" moaned Aspasia.

Crawford held her in a steely grip. His brow was furrowed, puzzled. Suddenly it cleared. "Of course!" he almost shouted.

"What, master?" Aaron asked. He was trembling uncontrollably.

Crawford disregarded the question. "Give me your revolver; take the spear," he said urgently. "Whatever happens, whatever you see, guard Aspasia. If I fail, hide, and run for the mountain during the night. Good-by."

He stood up, stepped from behind his shelter, exposed to full view of the swiftly flying Dragon.

"Don't!" Aspasia screamed. "It will kill you as it killed my father. I, too, shall die then."

She struggled to rise, but Aaron held her by force. His master was mad, but he had given orders, and they must be obeyed.

AT first Crawford thought the Dragon had not seen him; that it was continuing to the lake of its sojourn. But in mid-flight it swerved, circled once to check its tremendous speed, dropped perpendicularly with steely claws hideously outspread. For a moment Crawford was shaken; would the monster sear him with fire and flame? But the great scaly belly remained cold; only from tail and nostrils gushed streamers of blazing smoke. The monster wished to capture him, even as it had Alexander.

Crawford stood relaxed, steeling himself against the ripping thrust. His gun was pocketed, out of sight.

The Dragon came on with a rush. The wicked, razor-sharpened claws reached down, bit ruthlessly into his naked flesh, whirled him aloft into the air with a screaming of wind and snorting roars. Below, Aspasia promptly fainted, and Aaron invoked all his ancestors on behalf of his doomed master.

Crawford felt the blood dripping steadily from his sides, every movement exquisite anguish, but he squirmed around until he was staring up at the belly of the fabulous beast. It was scaly, unbroken, and rippled with the similitude of life. Behind, he could see the huge tail lashing through the atmosphere.

In all his life Crawford had never experienced the sinking sensation he now felt in the pit of his stomach. Had he been mistaken? If so, he was as good as dead. A revolver bullet would be but a flung pebble to this fiery Dragon; he would be dashed to splintered bones in the pit of the dead.

Then it happened!

The great belly yawned open like a gaping mouth; the claws that held Crawford retracted, thrust him into the darkness inside. The steely prongs released their cruel bite, withdrew, and the belly closed around him—like Jonah in the whale.

The pain of his wounds dizzied Crawford. He staggered, fell. Then there was light. The semi-darkness sprang into illumination. All around him was a soft, steady roaring.

The archaeologist came to his feet again, unsteadily. He was in a small, ovoid chamber, metal-sheathed; at either end were strange instruments of a type he had never seen before. There were voices, too, of men; the sound of Chinese diphthongs, of the rolling Greek of Homer.

Theramenes regarded him with a thin-lipped smile. "You are a hard man to keep put." The American idiom sounded incongruous in his slurred English. "What do you think of our Dragon?"

"I've known its secret for some time," Crawford lied quietly. "It's a rocket plane."

"You are indeed intelligent."

"The Chinese have reported the worship of the Holy Dragon for centuries. Who invented it?"

"My ancestor, twelve times removed. He found bitumen in the lake, refined it for fuel. His descendants are the hereditary captains of the Dragon."

He might have been lying, but it didn't matter. Crawford's head had cleared, but he swayed in pretense of faintness. His wounds ached horribly; the blood went drip, drip, down his sides.

"What do you intend doing with me?" he asked faintly. He had not been searched; no one knew that Aaron had escaped with a weapon.

"Do?" Theramenes said. "Throw you into the pit of the dead. This time you will stay put. You and the Alexander who thought he was divine."

For the first time Crawford saw the old man, lying in a pool of blood to one side. His breathing was labored, stertorous. If Crawford read the signs aright, he was dying. No help could be expected from him. The American half closed his eyes, to simulate exhaustion; from beneath locked lashes he warily surveyed the scene.

There were three men in the crew, besides Theramenes and Kang Chou. All armed, no doubt, the latter two with guns. Five against one! It would be a chance that he must take.

Theramenes said: "The devil! Aspasia, I had almost forgotten her. We shall turn back. She must be where we found the American."

Now was the time to act, if ever. Crawford felt real nausea at the thought of those cruel claws gashing that tender flesh. His hand stole unobtrusively to the pocket where the automatic rested.

But Kang Chou, with the guile of the Oriental, had not been deceived by his play acting. "He is shamming!" he cried in warning. "Look out!"

CRAWFORD completed his move in split seconds. His hand tore at the pocket, leaped out, gun muzzle in front, finger pressing against trigger.

A shot rang reverberating in the narrow confines. Kang Chou had fired first. Something burned across Crawford's arm; then his pistol spoke. It smashed the pointing gun out of the Chinese governor's hand, then the bullet deflected and plowed through the wrist, breaking it. Kang Chou cursed horribly and sat down.

Crawford whirled, balancing lightly. Just in time, for the Greek renegade was pressing home the trigger, a light of insane hatred in his slanted eyes.

Two shots rang out, almost simultaneous in their report. The wind of it tugged at the American's ear; but Theramenes stared in wide surprise, then slid slowly to the floor, a bluish round hole in his forehead.

Once more Crawford whirled to meet the rush of a Macedonian, spear drawn back for the fatal hinge. Just then the Dragon took a sickening plunge; the steersman had left the controls. The spear whizzed harmlessly past, to clang metallically against the concave walk Crawford braced himself, and shot. The man screamed and fell.

"Back to your posts!" the American shouted at the remaining pair.

With a wild rush they obeyed. The fight was gone out of them. They had never seen a gun before, nor known of its terrible execution. Theramenes had kept the secrets he had learned in the outer world to himself.

The Dragon was plunging and swinging erratically, its rocket jets, cleverly concealed in nostrils, eyes, mouth, and tail, roaring and sputtering. The steersman swung swiftly on a series of rudders; the great beast shuddered and steadied into smooth, slanting flight.

"Land her!" Crawford ordered, and gave directions.

The cowed Macedonians obeyed. Kang had stopped cursing salty Chinese oaths; he sat holding his shattered wrist, his face philosophically calm.

Aspasia and Aaron came running in through the opened belly, eyes wide with astonishment. Then the girl saw her father. With a cry she dropped to his side.

The old Alexander's stern, pain-wracked face softened into a smile. He was only a weary old man, about to die.

"Do not cry, my daughter," he whispered with evident effort. "It was my mad ambition that was responsible for the tragedy to my peaceful land. Theramenes, the traitor, urged me on. He is dead; so am I."

Aspasia flung herself upon him, sobbing. "No, no! You shall live, you must."

His smile held rare quality. "It is too late! The gods are calling me; the ancient gods."

He half rose. His voice was loud: "Jupiter Ammon; your son comes!" He fell back, dead. To the last he was Alexander, Iskander, the divine!

ASPASIA cried quietly, while Aaron patted her hand clumsily. Craw lord looked out of the tiny porthole. The scattered remnants of the rebels had reformed, were advancing on the Dragon, five phalanges strong. Brave men, t bought the American admiringly.

He turned to give orders to take off, when something else caught his attention. He stiffened incredulously. The air was full with droning noise. Five airplanes, bombers of an American make, were winging in battle formation over the inaccessible valley of the Heavenly Mountains.

The placid calm of Kang Chou wreathed into a smile. "It is my turn now," he remarked. "Those planes are mine, from Turfan. I left instructions. The pilots are foreigners, reckless fools who fear neither man nor devil. They come ahead of time, to seize the Dragon. It will be useful to convince my countrymen I am a good ruler."

But Crawford was not listening. Already the airplanes had deployed over the armed forces. Bombs dropped with deadly precision. The valley lifted and heaved. The temple was shattered into wind-borne fragments, the ming-oi, House of a Thousand Rooms, was Wasted from the side of the mountain. The strange, anachronistic civilization of two thousand years was being effectually wiped out.

Then a pilot saw the resting Dragon. The planes wheeled, came in a long, slanting rush. Crawford jumped into action, roaring orders. The terrified Macedonians saw the oncoming death, sprang frantically to the rudders.

The great monster shuddered throughout its sinuous length; jerked forward as the rocket tubes burst into roaring flame. Along the ground it bumped interminably, while the combat planes whistled with the speed of their flight

The leader was almost upon them. Crawford could see the helmeted face of the pilot reaching for the bomb trip, when the Dragon gave a great lurch and left the ground. It was up in the air, gathering speed.

The bombers whirled around, darted headlong for the fleeing prey. Machine-gun bullets whined and zipped; a pellet of steel ripped through the outer shell, ripped out again through the opposite side.

The Macedonians needed no urging now. The rudders controlling the rocket jets swung wide. The acceleration fairly hurled the great beast through the air. No plane could hope to keep pace with the hurtling Dragon.

Four of the bombers were dropping fast behind; one, the leader, held to the pace for a grim half minute. Kang Chou half rose, his mask ripped off.

The pursuing pilot saw that he was losing ground; in desperation he sent a last wild fusillade toward the fleeing monster. One bullet found its mark. It crashed through the belly, caught Kang Chou in the chest.

He spun around once, mouth half open, sprawled forward, arms outspread.

The Dragon lifted high over the encircling peaks, flaming and snorting at every pore; over the accustomed trail to Dead Mongol Pass, toward the encampment of the expedition in the hollow of the Black Gobi.

For some reason Crawford felt curiously happy as Aspasia nestled against his shoulder. No words were spoken; there was silence except for the curious throbbing of the unknowing Dragon.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.