RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

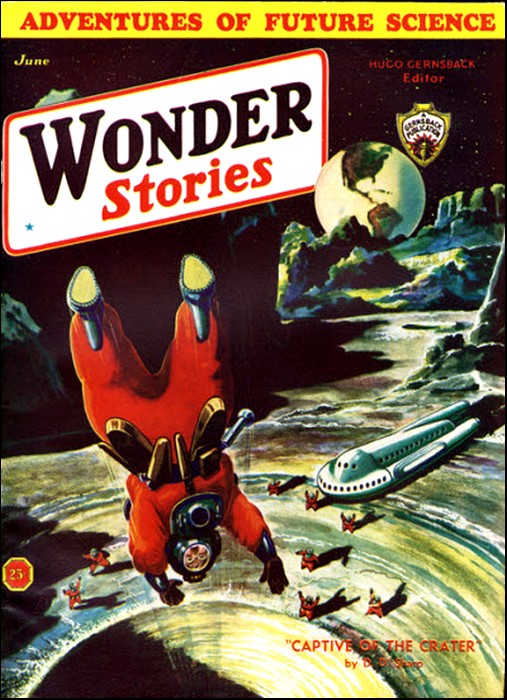

Wonder Stories, Jun 1933, with "The Final Triumph"

THE national bank holiday stirred the American people as few things have. It brought them face to face with those mystical things called money, bank credits, deposits and other things the man on the street has always taken for granted.

Mr. Schachner had written the final installment of his masterful "Revolt of the Scientists" around this theme. Scientists take a hand in this tremendous game of dealing with billions of dollars; with the lives of millions. Bankers for once find themselves confronted with forces that they are not trained to deal with. And the result .... we shall see.

Mr. Schachner has pictured very forcefully in this series what would happen should scientists decide to use their gifts in the creation instead of the destruction of lives and property.

THE fat loam of Iowa sank under the repeated thuds of marching feet. From all Pomona County there converged streams of men upon Pomona courthouse, choking the roads with unhurried clumping. Grim, gaunt men, cheeks hollowed from struggle and twenty cent wheat, with rusty rifles and pitchforks on their shoulders.

"Hiyer, Jim!" neighbor recognized neighbor in the tight-lipped flow. "Didn't reckon you'd come. The missus—"

"She ain't had nawthin' t' give the kids 'xcept bread an' moldy bacon rind this past six months. 'Sides, Ben Alley's kinsfolks."

Clift Saunders shook his head as he fell into step.

"Mighty strange, this foreclosure. First in years since the banks called this here moratorium. Ben's been paying his interest, ain't he?"

"The Lord knows how, but he done it. Now they up and want their money on the mortgage. Ben goes down t' the Pomona bank an' argues. Old Benton, the president, he shifts in his chair, looks uneasy, says somethin' about hard times, bad risk, and sticks to it. Ben says he ain't got the money. Benton talks foreclosure. Ben yells: "Foreclose and be damned' and stomps out. The sale's on t'day."

"Which it ain't goin' to take place," Clift remarked grimly, glancing around at the silent, pouring men. "Pomona County's pretty well riled up. Almost everybody's got an open mortgage on his farm, an' if Ben goes out, it'll be a start. Funny, though, old Benton getting hard like that. Maybe a taste o' rope'll be healthy for him."

"Not his fault," said Jim. "Georgie Withers, that's the paying teller down at the bank, tells my Sally the old man's all broken up about it. It was orders."

"Orders from whom?"

"Dunno. Georgie wouldn't say. Seemed frightened when I started to question. 'Pears he said too much!"

The great waste place around Pomona Courthouse was black with farmers, two thousand of them, faces turned to the courthouse steps, where by law Ben Alley's farm was to be auctioned off to the highest bidder to satisfy a mortgage of four thousand dollars. The steps were deserted, but the crowd waited patiently, gripping their weapons. There was no excitement, only a buzzing undertone that was more ominous than the loudest outcries. The sale was to take place at noon sharp, and it lacked ten minutes to the hour.

The sheriff of Pomona County peered out of a barred window. He glanced back at his white-faced deputies, spat casually, and turned to the portly, quivering man at his side.

"Them's folks we all know outside, Benton," he drawled. "Like you an' me an' Ben Alley. Those ain't popguns either; there'll be shootin'!"

The president of the Pomona Bank mopped his bald head. His complexion was pasty white.

"You've got a company of militia in the basement, haven't you?"

The sheriff shook his head.

"I didn't ask for them," he said slowly. "They came before dawn, in trucks. Showed me the governor's order. I don't like it, Benton. There'll be a heap o' people killed 'cause of your mortgage. Call the sale off; go easy on Ben."

"I can't," Benton groaned. "The Lord knows I didn't want to start this. It'll hurt business at the bank."

The sheriff stared at him curiously. "Then why—?" he began.

But Benton had seen again through the window the dark masses of men, the dull glint of sunlight on rusty rifle barrels, heard the ominous mounting growl as the minute hand of the courthouse clock twisted nearer to noon.

"I—I'll call him again," he gasped in interruption. "Wait for me, sheriff, I'm going to phone."

He was almost running out of the sheriff's office to the privacy of a phone booth in the corridor. The sheriff watched his portly frame disappear into the booth, spat thoughtfully, and remarked to no one in particular: "A mighty funny business!"

Which, or words to that effect, was what Clift had remarked earlier in the day.

Benton jangled the receiver excitedly. "Operator," he panted, "give me long distance."

It seemed ages before he got his number in far-off St. Louis. It was five minutes to twelve.

"First National? Put Mr. Redmond on; matter of life and death. Hello, Mr. Redmond. This is Benton, of the Pomona Bank. For God's sake, let me withdraw that foreclosure. You don't understand, you don't know! There'll be hell to pay! Five thousand farmers are outside, with guns. Sure, they'll shoot... National Guard? Yes, they're here. How did you know?... oh, I see, you had them ordered... Well, there'll be bloodshed just the same. I know the temper of our farmers... What, you won't permit it?... Then, by God, I'm going to call it off on my own... It's a damned..."

"If you disobey orders," said Redmond coldly, seated at his ornate desk within the Greek temple of his bank in far-off St. Louis, "I shall call in all the paper we rediscounted for you. That amounts to some two hundred thousand dollars, doesn't it?"

Benton knew when he was licked. His voice, ordinarily jovial and booming, was tired and old now.

"All right, Mr. Redmond. We'll go through with it."

"Sorry, Benton," said the St. Louis banker almost kindly. "It's not my fault. I get my orders also."

"From whom?"

But the St. Louis connection was already broken.

Back in the sheriff's office, the clock bonged twelve times.

"Well?" that worthy asked hopefully. Benton bowed his head without reply.

The sheriff sighed, took an extra hitch on his trousers, picked up the sheaf of foreclosure papers from his desk. "C'm on, Daley," he told the auctioneer. "And you boys," to the tight-lipped deputies, "stand on the top steps and don't show no weapons. Hope that popinjay captain downstairs don't go off half-cock." To Benton: "You're bidding the farm in, ain't you?" The president nodded speechlessly.

Out on the steps a dull roar went up. The sheriff began to read rapidly: "By virtue of the power vested in me as sheriff of the County of Pomona, State of Iowa, I hereby offer for sale, in accordance with a judgment of foreclosure duly made and entered—"

Three men pushed forward out of the crowd, and up the steps. A committee; Jim and Clift Saunders were on it.

"Stop, sheriff," Jim said harshly. "There'll be no sale today."

The sheriff spat a thin dark stream of tobacco juice across the weather-worn marble.

"It's the law, Jim," he answered mildly. "Neither you nor me kin stop it." He started to read again: "... in the Superior Court—"

Clift grabbed for the papers. The sheriff leaped nimbly back. "Now boys," he said placatingly. But the embattled farmers were already surging up the steps in a grim purposeful way. The sun was ugly on rifle-steel and bent tines.

The sheriff knew his people. "No bloodshed!" he cried to his deputies. "Into the courthouse and lock the doors." Benton and the auctioneer had already fled.

The interior marble echoed with clatter. The National Guard Company poured out, relined on the topmost steps. A half dozen machine guns thrust into position. Bayonets were fixed.

A little fat captain strutted pompously down two steps.

"Stand your ground, sheriff. The sale must go on." He glared down at the temporarily halted farmers. They had not expected this.

"And as for you men, clear out. I'll give you until I count ten. One... two... three..."

Jim turned and shouted something indistinguishable. The farmers milled inconclusively; trying to make up their minds.

"Four... five... six..."

A shot resounded. Someone in the rear ranks of the farmers had fired. The bullet hit no one.

The captain—he was a haberdasher in real life—lost his head.

"Fire!" he screamed.

There was a volley; the machine guns clattered! Jim and Clift fell, so did half a dozen others. The sheriff turned to protest his horror, but it was too late.

The farmers, grim at seeing their dead, came on with a rush. Another volley and then the two forces met in a swirl of hand-to-hand conflict. Blood dripped steadily from step to step, formed widening pools in the sullen earth. The sheriff was dead, the captain skewered on a pitchfork. Benton was hiding in the cellar, moaning over and over: "I knew it! I knew it!"

A plane winged eastward, traveling fast. Pat McCarthy, former expert of General Aviation, was the pilot and his passenger Cornelius Van Wyck, millionaire, explorer and adventurer. Both were members of the Council of the Technocrats, an organization of world-famous scientists who were attempting to remodel the world nearer their hearts' desire. Thus far they had been phenomenally successful. The Liquor Ring had been smashed,[1] the oil industry was under their sole control.[2]

[1] See "Revolt of the Scientists," WONDER STORIES, April, 1933.

[2] See "The Great Oil War," WONDER STORIES, May, 1933.

It was almost a year now since the petroleum industry had been taken over, and the results already were so patent that coal, copper and textiles had voluntarily submitted to the council, happy to have their moribund, dividendless state replaced by assured dividends, even though low and based on factual technologic values. Other sick industries were looking longingly in their direction. Only certain outside pressures held them in line.

The two Technocrats were flying back to their hidden base on the Maine coast with a report of their inspection of the newly acquired copper mines in the Montana fields. Even though the Technocrats were legally absolved from all past alleged crimes, it had been deemed wise to maintain the secret headquarters.

Van Wyck was jubilant. "Roode will be tickled with our report. Fellowes tells me he can correlate production with any demand we put upon him. And Randolph says he has the copper-hardening process completed. We'll have the steel industry on the run in six months if they don't come in."

Lee Randolph was one of the original Technocrats, former Chief Engineer of American Supermetals. Fellowes was a mining expert, one of the hundred odd technicians and scientists who had joined up after the council's sensational showing. The original group remained in control however.

But McCarthy had not listened to his companion's elation. He was staring downward at the flat Iowa terrain with creased brows.

"What's the matter, Pat?" Van Wyck asked, suddenly aware of his preoccupation.

"Something doing down below," was the brief reply. "I'm taking a look—see. Hold on."

The fast pursuit plane nose dived from the five thousand foot level with a great swoosh. The efficient silencer blanked all other sounds.

Van Wyck gripped his seat and peered over the steeply tilted side. The Roman rotunda of a courthouse bulked shinily beneath. Overflowing to the east was a horde of small, doll-like figures, swaying with unaccountable ripples and jagged movements. Tiny flashes spurted and tinier sounds came thinly to the diving aviators.

"A fight!" Van Wyck said hastily, and reached for the trips of his guns.

McCarthy levelled out at five hundred feet, and circled, trying to make out what it was all about.

Dead and dying were strewn in distorted attitudes over the plain; guns roared with booming concussion. He caught a glimpse of uniforms. Someone thrust up a rifle, fired at the plane.

"Shall I let them have it?" Van Wyck asked hopefully. McCarthy shook his head regretfully. "It's not our war. We'd better be going before some fool punctures us."

Van Wyck said determinedly: "Our war or not, I don't like militia uniforms; and they seem to be winning. Here goes."

Before Pat could stop him, he had picked up several small round bombs from the rack at his feet and tossed them over the side. They hit the earth with a dull thud and opened automatically on hinges. The liquid organic compounds sprayed into the air and oxidized into thick rolling white vapors. Almost immediately the struggling men were enveloped, and almost as immediately they wavered and sank dreamily to the ground, unconscious. Once more had the famous sleep gas evolved by Kuniyoshi, the Jap biologist, and Chess, the German psychologist, proved its worth.

"There's more in this than meets the eye," quoth Van Wyck, staring thoughtfully down at the suddenly silent, smoke-blown shambles. "I'm willing to bet this has some connection with the code radio we received this morning from Roode to come to World's-end.[3] It's the first full meeting we've had in months."

[3] The name of the secret, camouflaged base of the Technocrats on the Maine Coast.

Pat shrugged. "If it's more action, I'm for it. This being a big business man is too monotonous. I was thinking of handing in my resignation."

Van Wyck grinned: "Me too. Step on it."

A secret meeting was in session in a secluded, closely guarded office on Wall Street. No fanfare of publicity attended its deliberations, nor had any one seen these men enter. Yet the few who were present were men whose every word was solemn front-page news for a gaping public to digest. The real rulers of the country were here.

J.L. Claremont, iron-visaged and dominant, was probably the most powerful man in the world. Very rarely in the public eye, and content to have it so, his network of interlocking banks and web of affiliate companies controlled, if the truth were known, the greater part of the industrial and commercial life of the nation. A worthy subordinate was Willis N. Borden, head of the State National Bank and allied enterprises. A little to one side was seated Franklin Dennis, new chairman of General Power, Adam Roode's former employer. His fine aristocratic features were in sharp contrast to the fleshy, gross lineaments of his supposed rival, Harvey Belding, who perched precariously on top of a system of pyramided holding companies to maintain control of the great Mid-Continent Utilities Co.

Other internationally notorious captains of industry were present; notably Carter English, representing the Consolidated Railways; Robert P. Theodore of American Radio and Television; and J.B. Lawrence, of American Supermetals.

Lawrence was speaking earnestly, fist pounding the table, benign-seeming face aflame.

"I tell you, the impudence of those damned Technocrats is beyond belief. Imagine, only yesterday they served me with an ultimatum! Turn over the steel industry bag and baggage, or they'll run me out!"

He snorted and laughed in a false attempt at derision. But no one echoed him. These men listened solemnly.

"I understand," said Dennis quietly, "that they have developed a process for hardening copper. If that is so, with their control of the copper industry, I'd assume that they meant what they said."

Lawrence glared at him. "I suppose," he stated with heavy sarcasm, "you suggest that we yield humbly to their demands and beg for the crumbs that are left."

"No; I don't say that," Dennis stated even more quietly. "We are here to organize a plan of campaign to crush them, once and for all. But we must not make the fatal mistake of underestimating them. They are brainy, courageous men. I know Roode, and you, Lawrence, certainly ought to know Randolph. He helped make your industry what it is. Harmon has shown what he can do with oil. They have Van Wyck's millions in back of them, and oil, coal, copper and textiles, not to speak of the blind admiration of the people, who see in them and their gospel a way of escape from a decade of depression." He shook his head gravely. "We'll need every ounce of our resources to beat them."

"Bunk!" Borden, the banker, broke in violently. "Don't make demigods of them, Dennis, simply because you still have a sneaking liking for that old renegade, Roode. They've not met any real opposition as yet; just small fry. They'll be begging for mercy within a week."

"Stoneman was not small fry," English pointed out.

CLAREMONT smiled tolerantly. Instantly there was silence, and everyone leaned forward to catch the slightest intonation of this Power among Powers.

"Old Stoneman was pretty good in his day," he said. "But he is old and he stubbornly persisted in a dying industry. The world has swept past him. I've been listening to you gentlemen. You are afraid! Of what? A group of scientists, good enough in their field, but going out of their depth. What have they done? Oil? Coal? Both superseded by water power; Dennis and Belding, you ought to know that. If tomorrow we cut the price of broadcast power in half, we drive them out of business. Textiles? An anachronism, with rayon and fiber cloths in general use. Copper, I grant you, I overlooked. Control slipped out of my grasp. A paltry few millions to back them. Nonsense! In a month the very name of Technocrat will have been forgotten."

"Why not have the troops called out?" asked Belding eagerly. "Claim conspiracy, treason, rebellion, anything. The courts will back us up. You can do it, Claremont."

"Of course I could," the banker overlord replied with a touch of annoyance, "but I won't. You are all too crude; there is nothing of subtlety in your suggestions. Call out the army, and have a real revolution on your hands. It would give the Technocrats the chance of their life to raise the people against oppression, tyranny, what not. I'm handling this, and my own way."

His cold eye moved around the circle. There was respectful silence; no one dared dispute his domination.

"The time has come," he continued impressively, "to gain complete control of the country. Our present so-called democracy is a sham and a failure. We have shown that in the past; Technocracy is showing it now. The real rulers must have the outward power. We have left too many enterprises, too many industries out of our grasp. We must take them over, in one sweeping movement. Then we can starve the Technocrats out, crush them without open violence to arouse the nation. Legally! With proper ethical banking and business practice that the people are accustomed to; that they never had the brains to question."

"But how will you do that?" Theodore asked uneasily.

Claremont withered him with a contemptuous eye.

"Simple as A B C. We hold here, between us, working control of a majority of the nation's industries. They have a perfect right to refuse to sell their goods or service to anyone; that is good business practice. The industries which refuse to come in, are starved out. As for those controlled by Roode and his gang, there is to be no quarter. The whole country arrayed against them; no supplies, no credit. Let them make their own machinery, build their own buildings, grow even their own food."

"You forget the copper-hardening process," Dennis interposed again. "Perhaps they won't need our steel."

"You mentioned food, Mr. Claremont," said English curiously.

The banker smiled. "Why do you think I started mortgage foreclosures? To control food. It is even more essential than steel. No one can trace it to me. Every little bank or company with mortgages received orders from some other bank or company holding its paper. They in turn heard from others that held theirs. A few big ones took commands from a certain company that made it its business to obtain strong stock interests in them. That holding company is a dummy corporation for J.L. Claremont & Co.

His smile widened complacently. There were little murmurs of admiration.

"Test foreclosures," he went on, "were carried through successfully in widely scattered localities. Purely local affairs. They are accustoming the farmers to the end of the unofficial moratorium. Later they will grow in volume. We reinstate the farmers as tenants, subject to every control."

"There was trouble in one of them," observed Theodore.

Claremont passed it off.

"Just in Iowa. The militia captain was excitable; there was a battle."

"It had a curious ending," said Lawrence. "The papers are full of it. All the combatants suddenly went to sleep, wounded and all. No one knew what it was all about when they woke up; some claim to have seen an airplane circling above them."

The great banker said indifferently: "A mere natural phenomenon. The papers are playing it up."

"No," said Dennis suddenly. "It's deadly serious—to us."

A chorus of exclamations. Claremont frowned. "What do you mean?"

"This. Remember that memorable meeting of the Petroleum Institute?"[4]

[4] See "The Great Oil War" WONDER STORIES, for May, 1933.

"Yes," some one said.

"The Institute went to sleep in exactly the same way. Gentlemen," Dennis looked slowly around an intent circle, "the Technocrats have already taken a hand. They know somehow what we're up to and that was their answer."

Excited babble. Dark red suffused Claremont's features.

"You're right," he nodded. Then anger flared. "By God, we'll break them fast, without finesse. Let the farms wait." He pressed a buzzer.

A slim dark secretary entered.

"Miss Meehan, get me the portfolios on oil, copper, coal and textiles."

She withdrew silently, to reenter in some moments with bulky black leather cases.

Claremont ruffled through them.

"Ah," he exhaled satisfaction. "It will be simple. A total of eighty odd millions still outstanding in call and short term loans to Oil, sixty-eight millions to Coal, forty-nine millions to Copper, and thirty to Textiles. All held by banks and institutions we control, directly or indirectly, or can bring pressure on. Furthermore, outstanding merchandise bills total some fifteen millions; all due or to become due in thirty days. Our banks hold paper of most of these firms."

No wonder Claremont is what he is, thought Dennis. He has everything at his finger tips.

The banker closed the portfolios, leaned back with a gratified air. "Easier even than I thought. We call everything at once; loans, outstanding accounts. Flood them with demands today; start simultaneous suits tomorrow. Close all avenues of credit. Over a quarter of a billion due, in cash. It will be impossible for them to raise it, or anything near it. We apply promptly for receiverships; take over reorganization, work into control. The Technocrats are out—through; and legally! A horrible example to the men in the street of scientists trying to run big business!"

The others were fulsome in their flattery; even Dennis admired the scheme. It was impeccable, perfect! They dispersed jubilantly through surreptitious exits...

Such were the far-reaching consequences of Van Wyck's casual tossing of a few sleep bombs among the warring elements at a local foreclosure in Iowa.

At the same time a tall, monocled Englishman rose from in front of a queer photoelectric cell arrangement.

He was a recent tenant occupying a small office in the Wall Street building.

He clicked a button and the mechanism stopped whirring. He was smiling slightly. The Englishman, typically Oxford and Savile Row, was Lord Wollaston, the world's greatest authority on mathematics.

Some months before he had worked out conclusive mathematical proof of his pet theory that light, being an electro-magnetic phenomenon, or an ether disturbance, if you wish, could not be completely obstructed by the most opaque substances. Granted that most of the waves were turned back by solid, non-transparent substances, a certain number managed to squeeze through. One thousandth of one per cent, he found, for lead, one millimeter thick. Progressively smaller percentages for greater thicknesses. Of course entirely too small to affect the human eye or even the ordinary photoelectric call, sensitive to light from all sources. But—he went into consultations with Roode, atomic physicist, and Silversmith, radio expert.

This new type cell was the result. It was sensitive to the light emanating from a candle one thousand miles away, and most important of all, could be focussed.

In the present instance, he had carefully measured the distance from his rented office to the secret room where Roode had suspected the meeting was to take place. The instrument was focussed for that distance and pointed correctly. As a result only the light from the interior of the room, filtering feebly through a dozen walls, impinged on the sensitive cell. It reacted on a highly magnifying motion camera in the back of the box. This was Wollaston's own invention.

Accordingly he had a complete picture of what had taken place. Experts could decipher from the movement of the lips exactly what had been said.

Adam Roode surveyed his council grimly. His long lean body was tense. Everyone was there under the camouflaged roofs of World's End. No one had seen them come to that wild, deserted refuge on the Maine coast. Not even the new recruits to Technocracy knew of its existence.

Lord Wollaston's film had just been run, and Chess, the psychologist, had deciphered sufficient from the movements of the actors' lips to tell a coherent story.

There was somber silence. The full impact of Claremont's plan left them slightly stunned. Even Van Wyck, reckless fighter, was grave. These were weapons that could not be met with the machine guns and hydrogen bombs that had served so well against the Liquor Trust, or with the scientific weapons that proved successful against Oil.

This was something intangible—credit; money—and therefore so real as to be the mightiest power of all in modern civilization. His own millions gave him that realization.

Peter Dribble, Roode's assistant, and Van Wyck's particular friend, said with slight bitterness:

"So Van Wyck's sporting gesture with the sleep bombs precipitated matters. Claremont wouldn't have acted so fast if it hadn't been for that; we would have had time to prepare."

Peasley, world famous chemist, said sorrowfully: "I was hoping he'd keep his hands off until we were better entrenched."

Van Wyck started to say something heated, but Roode interrupted. His eyes flashed with their old fire.

"You talk like children. Claremont had already started to move. We were stepping on his corns. Don't you think I knew when we drafted the ultimatum to Lawrence that he would run to Claremont, who controls the Board of Directors? The foreclosures were his first step—an obscure one, I should say. As soon as we start war against Steel he would have to move faster. I welcome this complete openness. It gives us the chance to do things we otherwise would not have dared to do, for fear of the government, of alienating people to whom banks and bankers are still sacrosanct."

"But what can we do?" Dr. Myran, the surgeon, asked anxiously. "We can't meet a quarter of a billion."

"Of course not," responded Roode. "But we can counter-attack. We are prepared. Listen to this."

It was far into the night before the weary council broke up, but there was springiness in their steps as those who were to remain went to their sleeping quarters, and those with definite assigned tasks departed in silenced planes, taking with them strange looking boxes.

The morning of June 8th, 1940, Claremont's plan went into effect. The post office staggered under an unheard-of avalanche of mail. Millions of formal notices to every little business, every medium sized corporation and gigantic combine, every wage earner who had signed a note for a personal loan or endorsed one for a friend; every middle class person who had purchased an automobile or a radio or a vacuum cleaner on the installment plan; every farmer, home owner, and holder of real estate whose mortgage was open, overdue, or who had permitted the slightest default in interest, taxes or assessments; every purchaser of merchandise on credit; and of course, inconspicuously and naturally included, every industry controlled by the Technocrats.

John Jones, typical American small business man, cracked his three-minute eggs moodily. Business was rotten, nobody was paying his bills, and he had a hangover from a late poker session the night before in which he had been nicked to the tune of five bucks. Maybe the Technocrats were right after all.

"Good Lord, Madge, what's all this?" He stopped his steaming cup of coffee half way to his lips, and stared at the batch of letters his harried wife dumped silently in front of him. There were dozens of them. "Did I become president or something over night and the nation's sending congratulations?"

Madge shrugged work-worn shoulders.

"Looks more like bills to me."

"Bills!" he exploded. "I couldn't possible owe that much." Coffee was forgotten. His finger sliced through the envelope of the first one. It was from the building and loan institution holding the mortgage on their little home. A very polite note.

"We note with regret," it ran, "that you have failed to meet the water tax due May 15th. In accordance with Paragraph 9 of our mortgage, we are therefore compelled to declare the entire amount of the principal and accrued interest as due immediately, and to notify you that unless same is received not later than tomorrow noon, foreclosure proceedings will be commenced forthwith."

There was also the following cryptic addition:

"It is strongly suggested that in order to raise this sum or any part thereof, you immediately make demand for payment upon all persons who are in anywise in default on bills, notes, or other instruments due to you." John Jones was stunned. He looked with haggard eyes at his patient wife. "It—it's impossible! We've never paid our water rates until around July; the company knows that. They won't—they can't do this to me." He opened letter after letter with fingers that trembled uncontrollably. The milk company, telephone and electricity, all with formal urgent demands for immediate payment. The third payment on the shiny new car was two days overdue; accordingly, in accordance with Paragraph 10 of the conditional bill of sale, the whole amount was declared due and payable. A lending institution, for whom he had endorsed a friend's note in a moment of weakness, made sudden demand for the whole. And every letter ended with the same cryptic phrase.

John Jones ran out of the house that morning with food ungulped, leaving a tear-reddened wife and small unknowing children behind. The world was coming to an end! He must think; see what he could do at the office.

There it was even worse. Wholesalers who had carried him for months suddenly clamped down hard. That note at the bank, which he had discussed with the cashier only last week, and which was certainly going to be renewed, was just as certainly called.

Foreclosure, bankruptcy, ruin, the loss of everything he had worked so hard for, stared him in the face. He grabbed the phone violently.

"Mr. Glass," he said to the bank cashier, "you promised me—you know you did!"

"It wasn't a definite commitment," evaded Mr. Glass, who himself was wondering what it was all about. His desk was piled high with demands calling everything that was callable against the bank. The president had given abrupt orders for the cancellation of all credit, had even gone to the trouble of dictating the exact form of letter to be sent out. No explanation; but the cashier had observed he wore a harried look and locked the door of his private office when he was on the telephone. "Tell you what, Jones; why don't you dun all your own accounts in the same way—right now. Use our form letter. Maybe we'll see, if you do the right thing. Times are hard, you know, must lay our hands on every cent."

JOHN JONES hung up with a curse. All his wrath transferred to the people who owed him money.

"Miss L." he shouted, "bring your book for dictation, and get me the accounts ledger. The dirty so and sos, not paying their bills when I'm stuck like this. I'll fix them. Here, take a letter to Blank & Co.; say..."

And so it went in hundreds of thousands of homes and offices that Black June 8th. The nation was being called for payment to the tune of almost two hundred billion dollars! There wasn't that much money in the world, much less in the United States. To such a tremendous extent had the credit structure of the country reared its ungainly head, and made it possible for the masters of credit, to wit, the bankers, to cause their puppets to dance to a tune of their own making.

By ten A.M. newspaper extras were flaunting the streets; by ten-thirty a much bedevilled President was calling a hurried session of his cabinet to consider an unprecedented situation. The nation seemed to have gone mad simultaneously. Everyone demanding money from everyone else, in a sudden hysteria of fear. True, the depression had steadily widened and deepened, but why this crashing debacle?

Morse, Secretary of Treasury, ventured a timid opinion. He uttered the cloud-enshrouded name of J.L. Claremont. The President shut him up at once. Claremont responsible? Nonsense! He was a patriot, a public spirited citizen. Besides, this was beyond even his far-reaching powers.

But certain newspaper reporters, more realistic, hovered outside the august sanctum on Wall Street. Others of their brethren hurried from frantic interview to frantic interview with smaller fry; bank presidents, leaders of industry. Everyone was vague, most of them honestly so. Some one in a position to dictate had called them, forcing them to call others. Only the few of the Inner Council of Claremont knew.

By noon there were tremendous runs on the banks; by one o'clock the President, in solemn proclamation, had declared a banking holiday, to extend indefinitely. He had wished to declare a moratorium on all debts, but Chase, the Attorney General, had delivered himself of an opinion that such a course would be unconstitutional.

Claremont sat tight throughout the turmoil, smiling like a benevolent Buddha, and issuing orotund oracles to sceptical reporters. The situation was unexampled, he declared, but understandable. The credit of the country had been steadily deteriorating; people had purchased beyond their means, banks were compelled to draw in their horns. But let the country not fear. He, J.P. Claremont, was working night and day to reorganize the credit structure, put it on a sounder basis than ever, etc., etc.

"Baloney," muttered one reporter profanely under his breath, and kept on taking notes respectfully. The evening editions carried the statements; it restored a measure of confidence; prevented incipient revolution.

Claremont smiled even more broadly in the bosom of his Inner Council, invoked for the ostensible purpose of considering the situation in the interests of public welfare.

"Everything is working out according to schedule," he said. "The closing of the banks puts us in an even better position. The President doesn't know that I caused that idea to reach his ears. The cash of the country is tied up in our possession. Already the industries we are interested in have made overtures. With receiverships staring them in the face, they won't hesitate to accept our terms. Within a week, control will be in our hands."

"And the Technocrats?" suggested Dennis quietly.

Claremont's face hardened.

"They are through," he said. "We give them no terms, no quarter. Tomorrow, actions will be commenced against all corporations under their control for the appointment of equity receivers; foreclosures of property. My agents have instructions to work fast."

The door opened quietly. Miss Meehan, his secretary, said: "Mr. Roode and Mr. Van Wyck to see you, sir."

A bombshell could not have evoked more commotion. The Technocrats were bearding the lion in his den!

Claremont was the first to recover. "Show them in," he said. "Coming to beg for terms, eh?" His domineering gaze swept the circle, his strong gnarled hands opened and squeezed tight. "Well crush them, like that."

Dennis' aristocratic face was serious; it partook of none of the exultation of approaching victory that spread over his colleagues' countenances.

"Be careful, Mr. Claremont," he warned. "These men are most dangerous. If you would permit a suggestion—"

"Nonsense!" Claremont boomed. "I'll handle them. They'll be crawling."

Old Adam Roode, grimly set and more the down-east Yankee than ever, and Cornelius Van Wyck, carelessly smiling, were ushered into the room.

"Ah!" said Claremont with massive benevolence, "you come to—"

"We come for several reasons," Roode interrupted. He wheeled on Lawrence, the steel magnate.

"You have not answered our ultimatum," he said. "We demand an answer, instantly."

Even Claremont fell back at the colossal effrontery of the man.

"W-what?" Lawrence gasped. "Y-you have the nerve to repeat that insane gesture—now!"

"I take it then that you refuse," Roode told him brusquely. "Very well. We start production at once on our copper-hardening process. The market will be flooded with low cost metal every whit as good as your best steel. In a month you'll be begging us for mercy."

The lion started roaring. Claremont's poise was gone; he pounded the table.

"You'll soon sing another tune," he shouted. "You're here to take orders, not to give them. Your industries owe a quarter of a billion; tomorrow we start taking them over. You are through," he shouted more loudly, "through, do you understand? Your noble experiment is over."

Roode faced him unperturbed, while Van Wyck grinned at the others.

"So," said Roode softly, "our suspicions were correct. This whole mess can be laid to your door. You started it as a cloak to wipe us out of your path. We are a menace to your profits, to your power of life and death over the country."

Claremont hesitated, then plunged.

"And if it is, what can you do about it?"

"This," said Roode harshly. "We'll wipe you out unless our terms are accepted now, at once."

His long bony finger flicked out at each man in turn. "Lawrence, to turn over Steel; Theodore, his communication lines; English, the railways; Belding and Dennis," his face softened slightly at the sight of his old chief, then hardened again, "the utilities"; Borden he disregarded contemptuously, "and you, Claremont, all control over your banks."

A wave of derisive laughter swept the room. Belding's coarse face turned alarmingly purple in a very ecstasy of mirth; even Claremont permitted himself a slow chuckle.

Only Dennis did not seem to thoroughly enjoy the high comedy of the occasion. His eyes had never left the face of the scientist whose brain he had always respected; his own was deadly serious.

"I would suggest," his thin voice cut dryly across the general hilarity, "that we listen to Mr. Roode with attention." He turned to the scientist. "Suppose," he said, "your loans and general indebtednesses are extended to their normal business periods; would you be willing to withdraw all of your demands, including that on Lawrence?"

Claremont was on his feet, glaring.

"What infernal nonsense is this? Be careful what you say, Dennis, you've been acting suspiciously of late. Roode, you play your comedy well, but it is of no avail. You had better seek a nice quiet lodging place somewhere out of the United States, where the rent is not excessive. Your little period of strutting is over."

Roode said to Dennis, ignoring Claremont.

"You see how really shortsighted your colleagues are. You will have the pleasure of telling them so later on. But for your own peace of mind, matters have gone too far for us to have accepted your proposition. It is war to the bitter end." He flung to the others: "You are quite smug and secure about your power. But what is it based on? Money and credit! Money—that means gold in the last analysis; credit—mere scraps of paper; mortgages, notes, stocks, bonds, contracts; that is all. Without that, what are you? Nothing, nothing at all! Good day, gentlemen."

He stalked out of the lion's den with majestic tread. Cornelius bowed ironically, and followed.

Claremont pressed a whole battery of buzzers. Subordinates came scurrying in, orders flew thick and fast. The lion was exerting all his strength to crush these pernicious insects who dared talk back to His Majesty.

But Dennis shook his head. Now what had old Roode meant by his last retort? He was not accustomed to using random phrases.

Morning of June 9, 1940!

A hundred firms of lawyers scattered over the country rubbed palms together in high glee. The depression, the long lean years, were over as far as they were concerned. Stenographers typed madly, managing attorneys dug into form books for precedents, senior partners dictated the orotund sentences of legal phraseology, secretaries made cryptic pothooks in their notebooks, clerks dashed to the courts to file papers.

A thousand actions were beginning to grind their legal way, with a thousand different plaintiffs; but only a few defendants. Oil, Coal, Copper, Textiles, and the individual Technocrats!

Claremont was acting!

A well dressed, prosperous looking man walked briskly into the great banking institution of J.P. Claremont & Co. A long steel box was under his arm. He headed straight for the window marked "Vaults."

"I wish to rent a vault," he told the clerk. "A private vault, mind you, not a safe deposit box." He indicated the steel container under his arm with a laugh. "I was fool enough to accumulate a lot of worthless papers during the boom of blessed memory—you know, stocks like Steel and Telephone and Radio. Paid through the nose for them, too. It's a question of using them for wallpaper when wallpaper comes back into style, or putting them out of sight."

The clerk grinned understanding, albeit respectfully. He pushed out some papers for signature. The well-dressed man adjusted his glasses, read each document carefully, signed slowly, and pushed them back across the counter.

The clerk looked them over. Everything seemed in order. The name of the prospective customer was soundly Anglo-Saxon, the address impeccable, the two references men rated as triple A in Dun's.

"Everything is quite all right, sir," he said politely. "In two days your vault will be ready."

The well-dressed man grimaced, and indicated the box under his arm, "I must have it at once. You see," he explained, "I'm leaving on the evening boat for Nova Scotia. A month's fishing trip—for my health."

The clerk, who was a disciple of old Izaak Walton, himself, smiled and sighed. His fishing was confined to week-ends in the Catskills.

"All right," he said doubtfully, "under the circumstances. We usually check up references, but yours—. Here's the key." He thrust it out. "Shanley, take this gentleman down to Vault 36A."

A gray-clad guard ushered the well-dressed gentleman, still tightly hugging his box, into the bowels of the earth, past enormous steel doors literally covered with intricate mechanisms, fireproof, burglar proof and explosion proof. Millions of dollars in gold rested quietly within; the great bank's gold reserve. Claremont did not trust even the United States Treasury.

The new customer did not flick an eyelash as he went by. At the farther end the guard stopped, chose an intricate key from a bunch at his belt, swung open the steel outer door of a private vault. Inside was disclosed a second steel door.

"Your key opens that one, sir," the guard said.

The gentleman nodded, fitted his key into the lock, swung the door open. Inside was a cubicle of steel some three feet in dimensions, illuminated by a tiny electric light that shut off automatically as the door swung to again.

The guard lounged nonchalantly against the smooth steel side, and therefore did not notice the customer's thumb pressing against the lowermost corner of the box before he placed it carefully within the vault, making sure that the end of it contacted with the inner steel wall.

Then he locked the door, and straightened up with a sigh of satisfaction.

"I'm glad that's safe now," he said.

"You don't have to worry, sir," the guard assured him as he closed the outer door. "Nobody can touch that vault but you. You'll have to sign your signature next time you come, for identification."

The well-dressed gentleman smiled slightly. He was never coming back!

"Good day," he observed pleasantly.

"Good day, sir," answered the guard....

Later on in the day another man rented a vault under almost identical circumstances, except that his need for hurry was an operation he was about to undergo. He was given a vault on the same tier, but at the opposite end. The vast gold vaults were sandwiched in between.

Three men stood in contemplation before a complicated maze of apparatus in an old abandoned brewery in East Nineteenth Street, whose wall was flush against the East River. It may be remembered as the original Headquarters of the scientists when they organized and fought the Liquor Combine. Since then it had been broken into by the police and searched, but certain things had escaped their vigilant eyes. Such as, for instance, the concealed trapdoor which led down into the lock extending into the waters of the river.

On Ribling's death at the hands of the racket, his estate had sold the old brewery at auction. An obscure individual had bid it in cheaply, the deed was recorded, but the place seemed as blankly shuttered and deserted as ever.

The three men were Adam Roode, Alfred Silversmith, world-renowned radio expert, and Cornelius Van Wyck. Swinging slowly with the current in the lock rested a submarine, with a crew of two on board, waiting. "Everything set?" asked Van Wyck.

"Everything," said Silversmith, his dark eyes aglow. "Look," he pointed to a knife-switch set on a bakelite panel against a flare of blue-glowing electron tubes. "When I throw this switch, it sets a powerful beam-current in motion attuned to impinge on the mechanism in the boxes in the vaults. That mechanism is in two parts. One is a transformer capable of stepping up the intensity of the current a hundred thousand fold. The other, of my own invention, is a device which plays alternating electrical impulses through the steel walls and across the gap between the two boxes at an almost inconceivable rate of speed. In fact, they have been set to correspond exactly with the rate of vibration of certain definite orbits of electrons within the gold atom." "What would that do?" asked Van Wyck, the layman, deeply interested in the almost daily scientific miracles evoked by his colleagues.

Roode told him. This was his special domain. "The waves of energy, vibrating in unison with the electrons, will naturally amplify their vibration periods, and in so doing, kick them out of their orbits. They will then necessarily be lost to the atom. We have calculated carefully and set our vibration periods to knock off sufficient electrons from the gold atom, which has an atomic weight of 197.2, to bring its weight down to 119."

"But wouldn't the entire atom disappear?"

"No. Each orbit of electrons has a different vibration period."

"And the final result will be—?"

"Tin! A valuable element in itself but not nearly as valuable as gold. Furthermore it is not a medium of exchange, and that is what bankers are primarily interested in."

Silversmith was pacing impatiently. He took these things hard.

"Ready?"

"Ready."

The knife-edge contacted, the blue flares brightened, there was a loud humming sound, and powerful waves flung themselves with the speed of light to their destination.

THE machinery of the law, activated by the powerful catalysis of Claremont and his colleagues, for once, was whirling rapidly. Judges shut their eyes determinedly and signed orders for the appointment of receivers pendente lite, endowed with the most sweeping of powers. The basis for such a move was the allegation of insolvency, pending suits, and possible dissipation of assets to the irreparable harm of the plaintiffs, etc., etc., in the matter of Oil, Coal, Copper, and Textiles. Perfectly legal, even to the appointment of receivers who were henchmen of Claremont.

The newspapers smelled a rat, in fact, a couple of rats. The stench was terrific. Yet they dared not say anything, and wouldn't if they dared. After all, their owners' interests were tied up with the rest of the moneyed men against the Technocrats.

For strangely enough, no actions had been commenced against any other industry involved in the wholesale demands for payment except a few small too independent independents who were better crushed anyway. The big ones came into the vast weave being deftly thrown over the shuttle of the country's future. Their heads also realized the menace of the Technocrats.

Only the man. in the street did not realize what it was all about. He saw, and was carefully told, that J.P. Claremont, that great man, had stepped into the breach and saved the country from panic and worse.

Big business had miraculously freed itself from the nightmare, was being combined into a giant merger that would render impossible such a condition in the future; and so forth and so on. Only certain industries were too far gone, too rotten financially, to be saved under their present management. Needless to say they were the ones controlled by the Technocrats. But pending litigation would soon take care of that.

And so John Jones, whose note at the bank had been renewed, and whose home was saved by the gracious waiver of default by the building and loan association, nodded his head while he expansively smoked a good five cent cigar.

"I'll bet it was those Technocrat fellows all the time," he remarked sagely to his wife. "They're responsible for this panic. If we'd run them out of the country, the depression would be over. Yes, sir."

Forgetting of course that the depression long antedated the advent of the embattled scientists, and innumerable similar small details. But then John Jones, typical man in the street, believed everything the newspapers told him except the weather forecasts, and did not use his brains any more than he could help.

The great Claremont looked around the exultant circle of his council. He accepted their admiring congratulations with becoming modesty.

"We are completing a great work," he said. "The superholding corporation has elected us directors. We control seventy-five per cent of the nation's resources right now. Receivers are moving into possession of the Technocrats' properties. They have no defenses to the actions. Within twenty or thirty days, depending on the State, default judgments may be entered. The banks reopen tomorrow, but with restrictions. At their option, they may demand sixty days' notice for the withdrawal of moneys. That will effectually cut off any possible chance for the Technocrats to salvage even the smallest of their plants. The set-up is perfect."

"It looks that way," Dennis agreed in a doubtful tone. "But somehow I don't like their silence."

"Why wouldn't they be silent?" interposed Belding.

"They're licked and they know it."

There was a commotion in the outer corridor. Some one knocked hurriedly, imperatively on the door. Claremont frowned. There was a guard outside, and no employee had ever dared interrupt a meeting like this before.

"Come in," he said, inwardly determined to fire both employee and guard.

The door slammed violently open, and a man, his face drained white of all color, literally catapulted into the room. Over his twitching shoulder could be seen the anxious face of the vault guard.

Claremont frowned portentously. "What is it, Jenkins?" Jenkins was the confidential clerk in charge of gold shipments. The great banker had entrusted him that morning with the task of earmarking four and a half millions in gold coin for the Bank of England and thus close a very delicate and withal secret transaction.

Jenkins leaned heavily against the table, trembling like an autumn leaf. His mouth gulped continuously, yet no words issued.

"Speak, man," Claremont snapped. "Are you drunk?" With great effort the mouth opened again, and words issued gaspingly: "The gold! The gold!"

A cold hush broke over the assembled financiers. "What about the gold, you fool?"

"It—it's gone!"

Everyone was on his feet now. Claremont strode over, gripped the cowering clerk, shook him violently. "You're crazy, man. The gold gone! Where?" Jenkins almost slumped to the floor.

"It's not my fault," he quavered. "Yesterday I checked all the vaults. Eighty-five millions in gold coin to the penny. Today I went down to earmark the payment to the Bank of England—Shanley was with me, weren't you, Shanley?"—the gray-clad guard nodded in a frightened sort of way, "and I opened B vault, and the money was gone. I—I lost my head, I'm afraid; opened vault after vault." His voice fell to a whisper. "It was all gone."

Claremont's face was the face of a man who does not wish to believe. "You're drunk, the two of you," he said roughly. "How could eighty-five millions in gold coin disappear out of vaults? Were the mechanisms tampered with?"

Jenkins shook his head. "No sir. Everything was in order. The usual guards had been continuously on duty; nothing suspicious had occurred; no one even approached the tier except vault holders and in the presence of a guard."

Dennis bent forward slightly. "Were the gold vaults completely empty?" he asked softly.

"Why no, sir," Jenkins said surprised. "In my excitement I forgot to tell you. All the vaults are filled to the brim with a fine grayish powder."

Dennis made no effort to conceal his excitement. "Do you know what that powder is?"

"No sir. But Shanley," he indicated the guard, "recognized it. He used to be a miner when he was young. He says it's tin!"

There was a babble of confused sounds. Consternation stared openly on each face. Eighty-five millions of gold gone, and worthless tin powder substituted in its place!

Claremont's voice dominated the chaos.

"Jenkins, give immediate orders to close the bank doors. No one is to leave until I give the word. Shanley, round up all the guards, day and night shifts, for questioning. Borden, get Hearn's Detective Agency on the wire; I want Hearn himself and his best operatives down here in fifteen minutes. We'll thrash this matter out here and now. This is an inside job."

"It won't do you any good," said Dennis.

Claremont stopped his fierce pacing.

"What do you mean?" he roared.

"I mean that the Technocrats have acted, as they threatened to do."

"Poppycock! They're not magicians."

"No, but they are scientists, who are even more powerful. Remember what they did in the oil industry." Claremont's furious retort was checked by the insistent burr of the telephone. He picked it up.

"Mr. Roode wishes to speak to you, sir," said switchboard.

The great banker gulped, and then Roode said:

"Have you reconsidered our proposition, Claremont?" His watching colleagues saw his face mottle with apoplectic anger.

"No, damn you," he roared. "I'll see you in hell first. You've put your head into a noose this time. That gold—" He stopped with labored effort. His anger had made him say too much.

"The gold?" Roode repeated innocently. "What gold? Don't tell me my prediction has come true?"

"What's that?" asked Claremont unwillingly.

"That gold would eventually turn to tin. For years I've predicted that. The gold atom, you know, is a very unstable affair. Shouldn't have lasted even this long." "Then you were responsible?" said Claremont slowly, half awed. "This means jail for life."

"If you can catch me," Roode mocked. "By the way, tell Borden and the rest of your banking friends to look in their vaults. This gold disintegration disease spreads like wildfire. When you are ready to submit, use the radio. I'll be listening for you. Good bye." Claremont mopped a moist brow; then commenced to act with the thoroughness that had made him famous.

The telephone call was traced. A blind lead; it had been cut in on a main trunk wire near Yonkers. A general alarm was broadcast for the immediate arrest of each and every member of the Council of Technocrats. None could be found at their usual duties. Only subordinates in charge who maintained stoutly that their chiefs had left two days before without a word as to their respective destinations. Nation-wide check-ups on hoarded gold disclosed that the State National Bank and half a dozen others had suffered similar losses. A hundred and fifty millions in gold had vanished, leaving plebeian powdered tin in its place! At the insistence of Secret Service men nothing was touched, not the slightest speck, except a small quantity for analysis. They checked and rechecked the life history of every employee in the stricken banks; searched for finger prints, opened private vaults.

There they found something. Steel containers holding indistinguishable debris; the result of time bomb explosions. The names and addresses of the owners were checked. Responsible citizens, every one of them, but unanimous in vehement denials that they had rented the vaults or authorized any one else to do so. All trails blind alleys!

In spite of the most rigorous efforts at secrecy, the news leaked out. Rumors magnified the extent of the calamity. Nervous depositors descended on the banks throughout the nation in hordes, standing in long panicky queues for hours before they opened, for hours after they closed.

The Federal Reserve, the United States Treasury, rushed gold and currency shipments to the beleaguered banks, but could not stem the rush. There wasn't enough money in the world to stem it!

Claremont and Borden sat in conference with the President of the United States, his cabinet, the Speaker of the House, and certain key senators.

"This has gone far enough," said Claremont. "These Technocrats must be put behind the bars for life; hung, if necessary. Mr. President, you have been too lenient. Stoneman warned you; yet you did not act. He yielded, and you yielded. Now they have grown bold with immunity. A great nation lies prostrate."

"You've brought it upon yourself, and upon the rest of us," the President pointed out sharply.

"Had you not attempted to disrupt the credit facilities of the country in your attempt to gain control and crush these men, they might not have been driven to such desperate measures."

"It was necessary," Claremont defended himself. "They intended to act anyway. You do not seem to understand what they are aiming at. Nothing more nor less than a dictatorship over the world. You might as well abdicate your powers now, unless you are ready to act to the hilt, without regard to so-called constitutional rights. It is a state of war."

There was a murmur of approval from the senators.

"I'm afraid you are right," said the President wearily. "They have gone too far this time."

Within an hour the President issued a ringing proclamation. In view of the actions of certain malefactors and criminals, and by reason of certain unfounded rumors that had spread therefrom, now therefore, by virtue of, etc., etc., he hereby declared the doors of all banks to be closed pending reorganization and the restoration of national confidence; an embargo placed on gold shipments, the nation to be considered off the gold standard; a new national currency to be issued based upon combined bank assets as of June 1st, 1940 (a clever device to retrieve the value of the strangely transformed gold on June 10th), and an exhortation to all law-abiding citizens of the nation to ferret out and capture certain fugitives, to-wit, etc., etc.

The nation reacted to this momentous proclamation in various ways. Solid citizens, whose assets were suddenly frozen by the closing of the banks, roared for blood; the Technocrats' blood. Hanging was too good for them. But the employees of Oil, Coal, Copper and Textiles, having had a close view of the Technocrats and their methods; remembering increased salaries when the other industries were taking substantial cuts, spoke out loyally and vehemently. Not a man of them would betray his chief. The farmers, too, were solidly in opposition; they were rightly suspicious of Claremont and his associated bankers.

As a result, within twenty-four hours, there was chaos. Heated words led to blows, blows to weapons; armed partisans appeared as if by magic, and riots seethed and billowed resistlessly up and down the nation. Police, troops, were powerless.

In the meantime, the greatest man hunt in history began after the vanished Technocrats. But they were snug and safe in their camouflaged retreat on the Maine Coast.

World's End! Beneath the canopies of seemingly unbroken pine tops the scientists were assembled.

"Haven't we about shot our bolt?" Dr. Meyran, the surgeon, asked. "With the country off the gold standard, further transformations have lost their efficacy. It was a smart stunt on Claremont's part."

Roode shook his head vigorously. "Not smart enough. We've only begun to fight. With gold as a medium of exchange out of the way, the rest of our task is considerably simplified."

"Meaning—"

"That we attack paper next," Roode explained. "Credit, always the life blood of commerce, now stands alone. There is no gold cushion for it to fall back upon. Checks, promissory notes, negotiable instruments of all kinds, mortgages, bonds, stocks, contracts; what are they all but promises to pay, fundamentally based upon the signatures of the men or corporations who do the promising. Remove those signatures, and what is left? Nothing—mere printed phrases without the obligation to back them up. It is nonsense to assume that any one will pay grinding mortgage debts if there remains no evidence that he is legally obligated to do so."

"You have discovered a method of eradicating these signatures?"

"Peasley has. An old, familiar method, but refined so as to be very much more efficacious than the tedious incomplete former methods. But let him tell you about it."

Peasley said modestly:

"It's all very simple," he explained. "The fundamentals have been in use for many years. The average blue or black writing ink is essentially ferrosoferric tri-oxybenzoate held in extremely fine suspension, or if you will, in plainer language, iron gallate. After writing, and exposure to air, this compound oxidizes to ferric gallate.

"The best of the ink eradicators now in use is a mixture of oxalic acid in dilute solution and powdered tin. It dissolves the ink, and bleaches it out completely. This is well known. My particular contribution is merely to activate the oxalic acid to such a degree that a minute spray of it, reacting with powdered tin, will be sufficient to eradicate every vestige of ink within a hundred foot cube. Printed matter, printing ink being essentially carbon black ground into mineral oil, will of course not be affected."

"But how will you get these unwieldy materials into the banks and use them?" Dr. Meyran protested, slightly bewildered.

Peasley smiled. "The Secret Service was kind enough to help us out by ordering the reduced gold, now tin powder, not to be disturbed. They call it 'clues.' But I must really disclaim all credit. That should go to young Dribble who worked out the plan of operations, and to Van Wyck and McCarthy, who have volunteered to put it into effect. It will be most dangerous, I assure you."

THE banks were closely guarded. Claremont listened to Dennis' warnings this time. He remembered uneasily that cryptic utterance of Roode's paper—credit paper. Picked United States soldiers guarded the closed banks night and day; trusted guards were stationed within the gloomy vaults, ceaselessly watching untouched gold, stacks of currency, the vast accumulation of paper which on the face of it was worth very considerably more than all the precious metals in the world. Some one had calculated back in 1932 that the then credit structure of the United States alone amounted to the dizzying sum of half a trillion dollars.[5]

[5] Stuart Chase, in "A New Deal."

Claremont expressed his utter confidence. Gold wasn't the essential he formerly had believed it to be. The Technocratic industries were safely in his control; the Technocrats run into the ground. True, they hadn't been captured yet, but with the tremendous search that was in progress, it was only a matter of time. At that, it might all turn out for the best. He held all the strands of the web in his hands.

The pursuit plane, McCarthy at the controls, Van Wyck as observer, nestled out of the night sky on noiseless vanes. It was past midnight and the financial district of the city was deserted. Wall Street was a pool of quietness. The cordon of troops around the granite-walled bank of Claremont did not see the dark shape dropping to the flat roof. There was no jar as it landed.

Very quietly the two men removed a tank of specially activated oxalic acid from the plane, carried it to the center of the structure. Van Wyck produced a long steel pencil with an osmi-iridium tip; it was a cutting tool. The tip glowed into intense heat as he made contact. It bit into the stone and steel understructure as if it were so much butter. Within five minutes a hole six inches square gaped into the interior.

In the meantime McCarthy had rigged up a tube from the tank with a fine spray attachment. The nozzle was inserted into the opening and a powerful pump sent the oxalic contents shooting into the hollow of the building in the form of inconceivably minute particles. Then he set a metal disk into position in the opening, clamping it firmly to the sides.

Van Wyck waited a minute to make sure that the tiny droplets had time to spread through all the bank; then he spoke into the tiny communication disk strapped to his chest. It carried his low tones on a tight beam to Dribble and Silversmith, waiting in the interior of the old brewery.

"We're all set," he said. "Start the juice."

Silversmith threw a switch. Powerful impulses leaped through the intervening ether. They traveled on a focussed beam straight for the flat metal disk inset in the roof of Claremont's bank. The disk, a highly magnetic field, broke up the beam into circling waves of force. These impacted upon all finely divided matter within the area; notably the powdered tin within the vaults, the droplets of oxalic acid permeating the building, the omnipresent dust motes, and of course, atmospheric oxygen and nitrogen.

The impulses, weighted with tremendous electro-positive and electro-negative charges in rapid alternate oscillation, broke up these fine particles into mutually repelling molecules.[6]

[6] For example, the molecules of tin, an electro-positive element, finding themselves so to speak in an electro-negative bath, dispersed outward in an effort to neutralize their valences. The immediately ensuing beat of a negative wave thrust them into wild confusion, with the result that the tin powder dissociated into a horde of flying, plunging molecules to which the comparatively coarse interstices of the steel vaults presented no confining boundaries. And a similar process in reverse sent the negative oxalate "radical," the atmospheric gases, into a veritable frenzy of penetrative motion.

The whole process took only a minute. At the end of that period molecules of oxygen, nitrogen, oxalic acid and of tin were everywhere within the bank, even to the innermost recesses of the vaults containing all papers and documents.

Dribble timed the process, and at the end of ninety seconds shut off the waves. The electro-disturbance having been withdrawn, the molecules coalesced into normal conglomerates, and the inevitable chemical reaction occurred between tin and oxalic acid. It fell in impalpable fine spray upon the precious papers, and bleached all ink marks to invisibility...

The guards in the bank first noticed the process in the form of strange drafts of air that quickly grew to hurricane winds. Then came burnings of the throat, followed by rasping gasps as the tin and oxalic acid spewed forth. They quickly donned gas masks—Dorgan had prided himself on that foresight—but the masks proved worse than useless. The charcoal and chemical containers could not filter out molecular tin.

Choking, they blindly stumbled out into the street, giving the alarm.

McCarthy was already in the plane. Van Wyck shoved the empty tank into the cockpit, hoisted a leg.

"Look out!" McCarthy yelled. Van Wyck, accustomed to quick movements, threw himself sideways and rolled into the plane in a tumbling sprawl. A bullet roared in the night, spat viciously against the side. Someone shouted; there was another shot. At the same time the drumming sound of an airplane motor was heard overhead. A trap had been sprung!

McCarthy grinned widely. Disdaining the use of his helicopters he took off on a short slanting run. He barely missed the coping around the roof, swung upward over the city.

There were many figures on the roof now, shooting a perfect fusillade of shots. They spanged and flattened ineffectively against the armor-plate sides. A great shape dived for them out of the sky, thrumming and hammering with the speed of its flight.

Van Wyck, crouched low at the trips of his guns, murmured admiringly. It was a daring suicidal dive, so close to the roofs of New York. Their own plane was building up speed at terrific acceleration.

The diving plane—Van Wyck saw the familiar emblem of the United States Army gleaming on aluminum hull—levelled off skilfully, and the next instant machine gun bullets beat a rapid tattoo on the racing plane.

"Let them have it," McCarthy yelled, as he pointed the nose upward in a breath-taking zoom.

"Can't," Van Wyck replied, watching the pursuer swerving wildly around to get on their tail again. "That's a U. S. plane. Won't do to kill army aviators; don't want to anyway."

"All right then," McCarthy chuckled. "We'll show them a clean pair of heels."

The ship leaped forward under driving power, leaving their laboring pursuer far in the rear. As they hit ten thousand feet, it was nowhere to be seen.

McCarthy idled her a bit, circling over the city.

"Shall we make a try for the other banks on our program?"

Van Wyck shook his head. "No. They're prepared. They almost got us this time and they're forewarned by now."

McCarthy shrugged. "Okay. We'll pick up Dribble and Silversmith; and then shoot for World's End to report."

Claremont stood with a stunned air inside the great bank. Guards, policemen, Federal men, swarmed in a scurry of confusion. Everything seemed intact; the great vaults were unharmed, unopened; yet every document, every paper, had had all traces of ink removed. They were worthless scraps of paper now; these notes and contracts and bonds that yesterday had represented a market value of almost half a billion dollars.

Clues there were. The powdered tin had somehow disappeared out of the closed vaults; the floors of the bank, the desks, everything, was covered with a fine coating of dust-like powder. Hasty chemical analysis disclosed it to be tin oxalate, and of course its presence explained the eradicating agent used. But how had the tin come out of foot-thick walls; how had tin and oxalic penetrated foot-thick steel? That was an insoluble problem. The consultant scientists shook their heads puzzled, and murmured in awe-struck tones at the wizardry of their outlaw brethren. More than one staid chemist and physicist, respectfully answering Claremont's ejaculated questions, had daring thoughts revolving within his mind. At the first opportunity he would join the scientists, drink humbly at the fountain of such knowledge.

Claremont raged and blustered, his usual poise completely gone. General Perrin, in control of the New York area, listened with impatience. He had been placed in complete charge by the President at the first news of the disaster.

Claremont stopped his fevered pacings, wheeled on him.

"What have you done so far?" he accused. "Nothing, nothing at all! What's the good of the army, of the government itself, if they can't protect the property rights of its citizens? These scoundrels are making a mock of us all."

Perrin held his temper with great effort. His nerves were already rasped by Claremont's recriminations, the clamor for speedy action, and also his professional pride was hurt by these elusive scientists who struck with ease whenever and wherever they wished.

"We're doing all we can," he explained patiently. "We know how they attacked; one of our planes almost got them."

"Almost—" said Claremont with heavy irony.

"The outlaw plane was twice as fast," said the general. "Captain Stearn said they left him standing. We've also found their base of operations in this city; Ribling's brewery. They'll never use that again, even though the birds had flown by the time my men arrived."

"They'll use other bases then," Claremont said gloomily.

"No doubt!"

After that there was nothing more to say. There was silence in the office; each immersed in his own thoughts.

"If only we could locate their real base," said Perrin as if to himself, "Every army, every navy plane, is combing the East. Sooner or later they'll be found."

"And in the meantime," Claremont replied, commencing his leonine pacings again. "Roode has given us twenty-four hours to submit, or he'll go after the other banks." He wheeled on Perrin. "Do you know what that means? We're ruined; the country's ruined." In his egotism the welfare of the country and his own welfare were inextricably interwoven. "Half a billion's gone now; God knows how much damage they can do."

Again silence.

The door opened quietly. Claremont's secretary came in soft-footed: "A radio for General Perrin," she said.

"The Signal Corps operator asked me to bring it in to you."

Perrin took the slip of paper. It was in code. With a side glance at Claremont, he commenced deciphering.

The pencil made squeaking sounds on the paper.

He jumped up quickly, his countenance aflame.

"Mr. Claremont," he almost shouted, "we've got them! Here, read this." He thrust his decipherment upon the bewildered banker.

"NX4, Lieut. Winthrop reporting. Have discovered enemy base. Camouflaged by painted canvas. Noted plane entering. Position, Maine Coast, north Bar Harbor, Lat. —, Long. —. Keeping under observation, await orders."

The general literally pulled the great man along.

"Come along; you'll have a chance to see the U. S. Army in action."

The radio fairly sputtered code; telephone and telegraph worked overtime. Within an hour five hundred planes were converging on the doomed base of the scientists; troops hurled northward by fast trains and buses; tanks swung ponderously over rutted roads; the North Atlantic fleet tore under full head of steam along the rocky coast. General Perrin was taking no chances.

Within three hours Perrin, and Claremont who had insisted on being in at the kill, were dropped from a fast plane at the rendezvous, some fifteen miles from the beleaguered base. Already some five thousand troops were awaiting their commander, and more kept pouring in every minute. The sky was a pattern of circling planes, keeping their prey under vigilant watch. The fleet flung out in a wide-spreading net, belching black smoke. Huge gray battleships far out, fearful of the rocky coast, and trim low-slung destroyers steaming close to the line of breakers, tugging at the leash, waiting for the word to go into action.

Perrin surveyed all preparations with justifiable pride.

Light field artillery was being unlimbered; preliminary sights taken.

"What do you think of the army now?" he asked with a chuckle.

Claremont witnessed the ordered confusion, the great guns, the disciplined troops with bayonets fixed and trench helmets. It was impressive.

"Let them have it, general," he said viciously.

Perrin looked at him with something of surprise.

"I'm giving them a chance to surrender," he said coldly. "Wheelock!"

An aide-de-camp saluted smartly.

"Take this message to Major Mullan, 3rd Signal Corps. Tell him to send it out at once."

"Yes, general."

Within twenty minutes the ether was full of the message, broadcast on ten different wave lengths.

"Adam Roode and associates! You are ordered to surrender unconditionally within thirty minutes. Unless you reply within that period, we shall proceed to the attack. Hugh Perrin, Major-General, U. S. A."

The nation listened in on its radio sets. Technocracy was at bay, doomed! Portly citizens rubbed their hands in glee; settled back in comfortable chairs to await developments. The result was predestined. These super-criminals, these thorns in the sides of all right-thinking men, were about to be violently removed.

But other men, farmers, workers, the downtrodden, muttered viciously, struggled into coats, left tearful imploring wives at the loudspeakers, dashed out to the general store, the corner cafe that had taken the place of saloon and speakeasy, meeting house and crossroads. There they met others of similar minds; volunteer speakers harangued vehemently from upturned keg, table top, and platform; men's minds worked into frenzy. The sole hope of a new deal, a way out, for the submerged, was about to be ground into blood and earth.