RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, Jan 1936, with "The Isotope Men"

THE long, bleak room was hushed with strain. The gray morning light filtered wanly through the high, barred windows and tinged with vague unreality the strange apparatus that crowded the floor.

Kenneth Craig shivered a bit as he stared through the grimy glass at the huge, somber walls that inclosed the prison in unbreakable embrace. He was hardly conscious that his eyes carefully avoided the complication of equipment that he had helped to devise and construct; he knew, however, that he dared not meet the gaze of the three men who shared with him the immensity of the dingy interior. Surely the emotion that suffocated him and caused his heart to pound with great hammer blows was visible on his countenance for all to see.

Somewhere a bell boomed faintly, beating out the hour with sullen strokes. Craig ticked them off shudderingly. One—two—three—four—five—six! A silence fell upon the men in the room. Some one cleared his throat nervously. A sound arose, faint, far-off at first, then swelling into a muffled clamor of many voices, howling, shrieking in subhuman accents of despair and bitterness.

Kenneth Craig knew what it was without being told: The vast susurrous that exhaled from hundreds of gray-faced convicts, each immured in his own cubicle of steel, when one of their own commenced the slow death march to the execution chamber.

Execution chamber! Ken stiffened, shuddered again. A wave of revulsion swept over him. It was a monstrous thing they were about to attempt; it was worse. A man had a right to die in peace, even if he were what this man was claimed to be. He had a right not to be subjected to an experiment that would burst the bonds which nature had immutably decreed, and produce—what?

For the moment Ken was no longer the eager, brilliant scientist who had worked under and with Malcolm Stubbs, world-famous physical chemist and biologist. He was just a very human young man who shrank from the moral consequences of the next few hours. Animals, yes! The results had been dazzlingly successful; that was why the governor had granted this particular, unprecedented thing. But a human being! Who knew what the incalculable consequences might be; who knew——

Stubbs was an imposing figure, tall, angular, face carved into bleak, uncompromising lines. A harsh taskmaster who drove himself as mercilessly as he drove others; a man whose fanatical devotion to science had withered every human emotion, every human attribute. The past year had not been exactly a bed of roses, Ken thought wryly, though there were hundreds of others who would gladly have given their right arms to step into his place.

Stubbs stood close to the huge quartzite tank that ran like an oblong, transparent coffin down the middle of the room. Coffin? Ken grinned wanly to himself. Even his smiles were getting macabre.

The prison warden shuffled his feet with a scraping sound. It was he who had coughed nervously. He was a thickset man of middle age, and he had been in charge of the State penitentiary for almost a decade. He had supervised and been present at a hundred executions during that period.

Surely, Ken thought, he should be immune to any qualms over what was about to take place. But he was obviously not. His fingers clutched convulsively at the keys that dangled from his belt, and his free hand mopped continually with a large, damp handkerchief at his baldish head. His eyes jerked like marionettes on a string from the forty-foot tank with the profusion of apparatus in back of it to the narrow, gray door.

The fourth man was the most placid of them all. He leaned easily against the wall, chewing with calm deliberation on an unlighted cigar. He was the prison doctor, short and somewhat dumpy, with pink, smooth cheeks and a correct, impersonal manner.

The muted howling from outside died away as suddenly as it had arisen. As if the inmates knew that it was all over, that the thing was done, irrevocably. Ken felt the palms of his hands go dry and hot. If only they were right; if only it were over! But they were mistaken. The electrocution chamber was only a few steps from "Condemned Row"; the current should already have surged through the body of the man whose life had been declared forfeit by the State. This place which they had transformed into a laboratory was at the farther end of the prison yard, and it took time for the slow, measured march.

No one but the four of them, waiting in hushed rigidity, and the governor, knew what was about to be done. Not the prison guards; not the inmates; not a single, solitary person in the outside world; not the condemned criminal himself.

"If this should leak out," the governor had remarked grimly when he signed the necessary documents in authorization, "it would be as much as my political head is worth."

He had been mighty reluctant, the governor had, and only the ruthless pressure Stubbs had brought to bear, and a certain awe which he had for science in the abstract had turned the trick.

For over a month Stubbs and his young assistant had worked in feverish secrecy, at dead of night, setting up their equipment in this abandoned workshop. The governor had insisted that the experiment take place within the prison walls, where, if necessary, the results could be quietly hushed up. An order had been issued the night before, routine, officially terse, barring reporters and spectators from the impending execution of James Horty, bank robber and murderer extraordinary.

THE door swung open. Ken whirled. His nerves were jangled. Warden Parker dropped his heavy keys with a crash. His hand trembled as he stooped to pick them up. Even Dr. Bascom stiffened from his slouch. But Stubbs, to whom this meant the consummation of years of insane, driving toil, did not move.

Two men in the blue of prison guards came into the room. Between them, manacled to their wrists, was a third. His face was as gray as the loose, ill-fitting costume he wore; his brutish, deep-set eyes disclosed the terror that seeped from within. Yet his head was flung back; a sneer of attempted bravado writhed at his lips. He owed it to the curious spectators, to the reporters, to his fellows out there in the world of sky and city streets and smoke-thick hide-aways, to put up a good show. "Jim Horty, dead game to the last!" The words danced before him and braced limbs that unaccountably wanted to sag beneath him.

His pig eyes darted around the room. The hot spot! Where was it? He'd spit contemptuously in its direction. That would be a new gag, would rate columns in the papers. All through the long, dreary hours in Condemned Row he had thought of that last, supreme gesture.

The steel links clashed indistinctly on his wrists. There was a dull roaring in his ears. Where was he? This was not the execution chamber. That big tank, filled with stuff that looked like jelly, all that funny-looking machinery around the room—what did it all mean?

For a moment a wild hope surged through his heavy, ape-like frame. Any change from the sinister routine meant only one thing: The governor had reprieved him. He would live—live!

Sure! There was the warden, the louse, and the doctor. Old "Crab-face" didn't look any too good—like he was scared of something. Of what? Horty looked wildly around again even as the door shut behind him with irrevocable clamor, and steel locks tumbled into place.

He began to sweat. It was a crummy sort of place. The execution room he could stand—he had hopped himself up for that. But all this—it gave a guy the shivers. Crab-face scared, "Doc," looking through him as though he wasn't there. And those other two fellows. Never saw them before. One bird, just a youngster, looked white around the gills, and there was pity in his eyes. Pity! For Jim Horty! There wasn't any reprieve then. But what——

His limbs trembled under him. He would have fallen if the guards had not held him up.

"What you gonna do with me, warden?" he croaked hoarsely.

Warden Parker shook his head. He did not like this himself. It was out of his line. Horty was entitled to a nice, clean shot of juice, just like the others. A couple of minutes, and it would be over, everything regular, and the normal routine of the prison would flow on. But this! Well, orders were orders!

"Sorry, Horty," he said almost kindly, "you're not in my hands any more. Mr. Stubbs has complete charge here."

Stubbs nodded. To Horty, his tall, angular frame seemed to grow and distort, and his eyes glittered with strange lights. "That's right, Horty. And you ought to be mighty thankful, too. You are about to become the subject of an experiment that will change the course of the human race, produce results incalculable in their consequence. Instead of dying ignominiously in the electric chair, to you has been granted the supreme honor of becoming the first of the new men!"

What was the old geezer talking about? Experiment! First of the new men! No electric chair! The warden looked more scared than before, and that young fellow——

A blinding light seared through Horty's brain, brought understanding. They were going to cut him up, see how his insides worked, like they did in hospitals to dogs and rabbits. Vivisection! That's what they wanted to do to him. He threw himself suddenly forward against his manacles, so suddenly that he almost dragged the guards off their feet.

"I ain't gonna let him cut me up," he screamed. "I got rights! The judge told me I'd get the electric chair. I'm entitled to it; nobody can take it away from me. Warden Parker, don't let him cut me up."

He was pleading now, sobbing, all his bravado forgotten, pleading for death, for anything but that tank and that machinery and that old fellow they called Stubbs with the eyes that burned right through him.

"It's the governor's orders," Parker answered helplessly.

The scientist took a step forward. "You fool!" he exploded. "Pm giving you a chance at a new life, at a life far beyond your stupid comprehension."

"I don't want it," the criminal screamed. "I want to die, like they told me. Get me my mouthpiece; hell help——"

"All right, men." Stubbs nodded coldly to the guards. There was no use in arguing further with the idiot. The experiment must go on according to schedule.

They handled the shrieking, struggling criminal expertly, impersonally. It was all in the day's work. They unlocked the handcuffs, threw him down on a pallet, stripped him of every shred of clothing. Then, oblivious to his shrieks and obscene cursing, they held him tight while Stubbs injected a hypodermic into his arm.

The shrieks grew fainter, thicker; then they died away in a long shudder. James Horty lay stiff, unmoving, unknowing.

KEN CRAIG was already at the huge quartzite tank. Now that the crucial experiment was already under way, he became once more the scientist. Human emotions dropped from him like a cloak. Every step of the procedure had been rehearsed a dozen times; had been practiced with animals on a smaller scale time and again. Most of the technique, as a matter of fact, was his. Stubbs was not good at that.

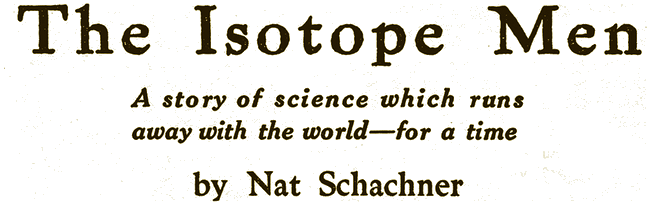

The great tank was forty feet long, ten feet wide, and five deep. It was filled almost to the top with a clear, lusterless jelly. Huge electrodes sank deep into the thin, quivering stuff at either end, and were connected by cables with an instrument board on the wall.

Ken pressed a button. A section of the glass top slid smoothly underneath, leaving the tank exposed just wide enough to admit a human body. Above it, suspended from a miniature crane, was a cradle of extremely thin, longitudinally stretched wires. At a gesture from Ken, the guards lifted the immobile body of the condemned man, deposited it carefully into the cradle.

Then he knifed a switch. There was a whir, and the cradle, with its strange burden, dipped slowly from unwinding chains into the transparent substance within the tank. Down, down, ever down, while the men in the room stared with fixed, unwilling fascination. Dr. Bascom forgot his pose of smooth boredom, leaned eagerly forward. The guards gaped blankly.

Ken was tremendously cool now; all his faculties concentrated on the work in hand. The jelly closed with a quiver over the descending form. Within its clear depths the cradled body showed like a prehistoric monster caught in a huge globule of ancient amber.

There was a tiny bump. The cradle had come to rest on the floor of the tank, close to the positive electrode. Ken pressed another button. The wires opened out underneath the rigid body, and the apparatus rose to its former position again. The glass section slid smoothly into place. The tiny click, as it closed, was loud.

The warden shivered, looked around. Professional routine jerked him out of his haze. It would never do for the guards to witness what was going on. They might talk.

"O.K., you two," he said harshly. "Get back to your duties." The men muttered something, went out hurriedly as if they were glad to be done. Even the tainted air of the prison corridors outside seemed sweet after what little they had seen in the converted workshop.

Stubbs moved quickly to the instrument panel. For an instant, his long, bony fingers clung with fierce grip to the bakelite handle of the master switch. His eyes burned through the transparency of the tank, fixed with a fanatical light on the quiescent body within.

The future of the world rested on the tug of his hand. If the experiment proved a success, his name would go rocketing down the centuries. Darwin, Newton, Einstein, Galileo would be pale, glimmering phantoms compared to him. Yet he hesitated. Things his young assistant, Ken Craig, had said, flashed through his mind. The youngster had pleaded with him not to go through with this final test. Had been damned persistent about it.

He, Malcolm Stubbs, had finally forbidden further discussion. The young whippersnapper, with his silly talk of outraged nature, of incalculable results. What of them? Science was its own justification. Nothing else mattered. Suppose what Craig had said were true? For an infinitesimal second a vague doubt disturbed his fanatic unity of purpose—then he was himself again. The switch knifed down.

A TREMENDOUS current surged through the electrodes. The jelly, at their base, stirred uneasily, blurred slightly with tiny bubbles. The seemingly dead figure of Horty hazed at the edges.

The great experiment had begun! The experiment that would change the face of the world, that would bring to pass disruptions and transformations beyond anything even Ken, in his vaguest and most inchoate fears, had ever dreamed possible. Could the four men in that laboratory have peered into the future—— But that was impossible, inconceivable. And wiser perhaps. If the human race could visualize perfectly the consequences of its acts, nothing would ever be done, ever accomplished. Mankind would die of dry rot and cowardly inanition.

Ken looked at his wrist watch. "Six ten," he reported. "At seven fourteen the reaction should be complete."

A choking gasp came from the warden. Terror leaped into his eyes as he pointed with trembling finger toward the innermost recesses of the tank. "My Lord, look!" he almost screamed. "Look at Horty——"

Ken had never taken his eyes away. The prison doctor's face was a mask of wonderment. Stubbs permitted himself a bleak, frozen smile. The experiment was proceeding according to schedule.

The body of the immersed criminal seemed to have widened out. Not bloated, in the way a dead thing swells when putrefaction sets in, but stretching in a flat, horizontal plane along the jellied floor of the tank.

The features were still there; the outlines of his nude form were still, recognizable, but they were curiously vague, curiously misty, as they groped away from the positive electrode, seemingly urged by some irresistible force in the direction of the negative cylinder.

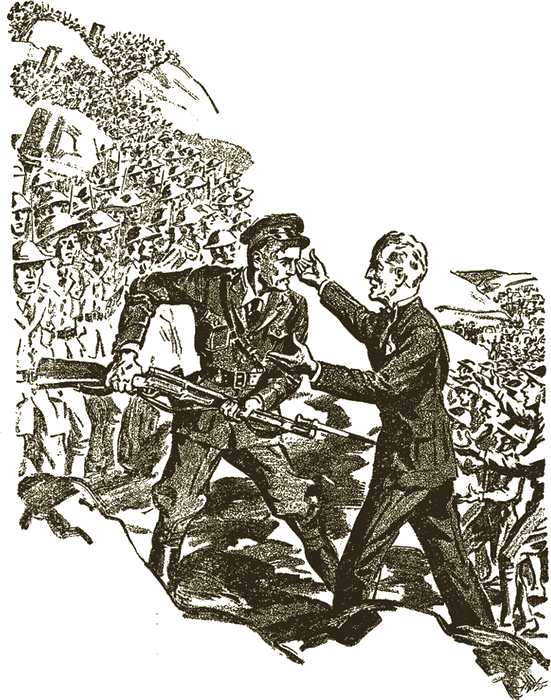

The features were still there but curiously misty,

as they groped away from the positive electrode.

Ken was suddenly weak inside. He could understand exactly how the warden felt. He had seen this happen many times with small animals, but a human being, even a murderer, was somehow different.

Stubbs' eyes snapped angrily. He did not like any display of human emotion during the course of an experiment. It complicated things unnecessarily and introduced an incalculable element which found no place in his scientific equations. The emotions altogether were signs of weakness, of addle-pated thinking.

"There is no need for expletives or dramatics, Mr. Warden," he observed with glacial frigidity. "I must insist upon a proper decorum from the spectators."

But Parker was beyond hearing the intended rebuke. His eyes were bulging on the tank. The jelly was quivering with strange forces. Invisible strains emanated from the positive electrode, heaved the transparent substance in long, internally contained billows down the length of the tank. The process was accelerating.

Jim Horty was no longer a solid, compact body. He had lost shape and substance. He was stretching out along the plane of vibration in a tenuous, ghost-like flow; he was blurred and misty and unrecognizable; he was a parallelepiped of former length and thickness, but already he was three feet wide and expanding visibly. Then, as Parker uttered a choked cry, something happened.

The misty, tenuous form seemed to divide along the longitudinal axis of his body, something like a cell reproducing by binary fission. To the extreme right and left, dense, formless masses made dark blotches within the jelly; in between, shading into the two heavier sections, was a thinner, more rarefied substance, through whose interstices the vague, adumbrating outlines of the tank behind were dimly visible.

Parker's face was gray and twitching. Stark horror swept over him in a blanketing cloud. He could stand it no longer, this thing that he was witnessing. With a shrill cry he wheeled, ran blindly toward the steel door, fumbled with palsied fingers at the bolts, and was out. For the first time in his life the warden had known fear; for the first time in his life he had violated the simple terms of his duty. He had quitted the side of a condemned criminal, had abandoned him to the hands of men not connected with the prison.

It was not until he reached the privacy of his own office, and dropped trembling into a chair that he thought of that. But Horty was no longer alive, he argued with himself. It was inconceivable, ghastly, what he had just seen. Not for a million dollars would he venture back into that place of horror. Let those inhuman scientists do what they wished, as long as he did not see.

BACK in the converted laboratory, Stubbs was faintly amused. A sardonic smile twisted his thin lips. "We're better off without him," he remarked to Dr. Bascom. "You don't feel the same way about an epochal experiment in science, do you?"

The prison doctor hastily stuffed into his pocket the large handkerchief with which he had been mopping his too-pink face.

"No, no, of course not," he replied hastily. "I wouldn't miss this for worlds," Yet Ken was sure that only professional pride kept him from following in the footsteps of the warden.

Ken forced his eyes away from the tank. Everything was proceeding according to schedule. There was nothing else to be done now but wait. And it was not a pleasant sight to watch. Silence, however, would be insupportable.

"I think Dr. Bascom would be interested in knowing exactly what we are doing," he told Stubbs.

The doctor glanced toward the tank, looked hurriedly away again. Perhaps, if he could focus his mind on cold, scientific abstractions, the quay feeling might pass away.

"I'd be honored," he replied eagerly. "I have only the vaguest ideas as to—that!" His short, pudgy arm extended in the direction of the tank.

Stubbs frowned. What did Craig mean by his fool suggestion? He knew how he, Stubbs, hated explanations, especially to a layman. A doctor? Bah, worse than a layman! His mind would be cluttered with a horde of outworn ideas, of old wives' superstitions masquerading in the guise of science. Nevertheless, he was an audience, and the experiment was going smoothly, and Stubbs was still human enough to be vain of his accomplishment. So he unbended slightly, and condescended to the doctor.

"A good many years ago," he began rather ungraciously, "I had a brother. When the War came, he was idiot enough to leave my laboratory, to throw himself into the trenches. When it was all over, he came back. But the War had done things to him. Your fellow medico diagnosed it as shellshock. That, no doubt, was the inducing mechanism, but the result was definitely what happens in a very inconsiderable number of cases.

"My brother was no longer himself; he was two other and distinct personalities. He remembered nothing of his past life; nothing of myself, his family, or friends. The two states were separate and sharply defined. He would alternate suddenly from one to the other, and in each State he would be wholly unaware of his other incarnation, so to speak."

Dr. Bascom nodded his head vigorously. He was interested now. This was something in his own field. "A clear case of dissociation of personality," he remarked. "Or what is sometimes called dual personality. Janet has listed any number of cases in his 'Major Symptoms of Hysteria,' and Morton Prince made a very careful, painstaking study of a single instance in his 'Dissociation of a Personality.' "

Stubbs said scornfully: "I've read them just as I've read every one else who pottered around on the subject. All they do is describe the effects, the end results, but not one of them went behind the effect to determine the cause, the reason."

"I don't think that's quite fair," Bascom objected. "There have been any number of theories. Freud, Jung and Adler claim that it is the unconscious coming to the fore, and masking the conscious personality. There are others who——"

"Bah!" Stubbs snorted. "I am a scientist, not a dreamer, a hider behind words. The unconscious! A word to becloud the issue. What, scientifically, does it mean?"

"Well——"

"Precisely," Stubbs interrupted. "Nothing at all. I delved deeper, seeking the true inner mechanism of the change. No wonder the medicos, psychologists, what not, were at a loss. The real explanation was out of their field completely. It was in mine, the field of physical chemistry. It was left for me, Malcolm Stubbs," he continued triumphantly, "to discover that mechanism."

Dr. Bascom gasped. He knew quite as well as Stubbs that the pretended explanation of dual, or multiple personalities, does not explain. If what this tall, angular scientist was saying was true, then the whole field of psychology, of neural medicine, would be changed.

"But how?" he asked.

Stubbs ignored him completely. He was just an audience, nothing more. "Did you ever hear of isotopes?" he demanded.

"Yes," the doctor admitted cautiously, "but I have only a vague idea of what they're all about."

"So do most people," the scientists retorted. "Up to quite recently it was thought that the so-called elements, like hydrogen, oxygen and lead, were really simple elements. That they could not be broken down any farther, except, of course, into electrons, protons, etc. But a good many workers were suspicious about the fractional masses of the supposedly simple elements. According to the periodic law, according to the electron theory, these masses should have been whole numbers.

"Then came startling discoveries, in which I did my share. These so-called simple elements were not simple at all. They were mixtures of two or more true elements, lying close together on the atomic scale, and so nearly identical in their physical and chemical properties as to be very difficult to separate. And each one had a whole number as its atomic weight. Thus, oxygen, in reality, consists of three isotopes, with weights of sixteen, seventeen and eighteen respectively. Carbon has two, nitrogen two, sulphur three, and hydrogen had its isotope also—deuterium."

The doctor smiled. "I've heard of that, all right," he said. "Even the newspapers give space to heavy water."

Inwardly, however, he was wondering what the devil all this had to do with the unspeakable thing that was happening in the tank. Out of the corner of his eye he caught a glimpse that made him avert his gaze quickly, and changed the smile on his face into a forced, sickly grin.

There was no evidence of the man they had called James Horty any more. He had been swallowed up, ingested seemingly into the horrible plasma that filled the quartzite interior, that was quivering now and bubbling in a veritable witches' broth. Faintly, halfway down the tank, was an amorphous cloud. Without shape, without outline, yet Bascom had the sickening sensation that somehow, somewhere within that slowly progressing mass, the material thing that had been Horty resided.

THE dense phantom trailed back through the jelly in a slowly thinning smoke, until only the straining eye could discern its presence. Then it thickened again, still more slowly, until, some five feet from the positive electrode, it coalesced into a thinner, rarer, smaller simulacrum of the more rapidly moving mass. There was that within its formless vagueness which appalled the doctor, more even than the farther one.

"Yes, I've heard of that," he repeated dully. He must say something, anything, to rid him of that last glimpse.

"It struck me suddenly," Stubbs went on incisively, "that in the isotopic elements lay, possibly, the answer to the problem of my brother, of all similar cases of dissociation of personality; even, perhaps to the unconscious that the psychoanalysts talk about so glibly."

"I don't see how," Bascom said, plainly bewildered.

"It is really quite simple," the scientist explained patiently. "The human body, protoplasm, bone structure and all, is composed chiefly of six elements. Carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulphur, and calcium, with a scattering of others. Every one of these has been dissociated into its isotopes. They exist, as far as we know, in indisseverable mixture. But suppose that isn't so. Suppose that some internal mechanism exists in the human body, in each cell, which under certain rare conditions, clicks, and dissociates the isotopes. We already know much about the genes of inheritance within the cell nucleus. We know that there are present, side by side, genes of opposing inherited characters. The stronger, or dominant gene will mask the recessive characters, as if they did not exist. Yet, in the next generation, perhaps, the recessive gene, by proper association, may in turn mask the dominant characteristic."

Dr. Bascom was listening intently now. Ken Craig had heard this exposition before. As a matter of fact, it was he who had suggested the analogy to Stubbs, had finally put him on the right trail. Naturally it was too much for an assistant to expect credit.

"Why then, I thought," Stubbs went "might not the isotopes of the elements in the human body act the same way? Those present in the largest quantity would be dominant, the others recessive. Less than one per cent are the isotopes; the other ninety-nine per cent what we had heretofore considered the entire element. Suppose, as in the case of recessive genes, something happens, and the minority isotopes suddenly mask the dominant norm. What would you have?"

The doctor's eyes bulged. "Why, I—I'd say you'd have a different personality. The other part of what we've called dual personalities."

"Exactly," Stubbs declared triumphantly.

For a while there was silence. Bascom dared not look at the tank. He was afraid. It was hard to digest what he had just heard. Then, diffidently, he ventured: "The theory sounds impeccable. But——"

"How put it into practice?" Stubbs finished for him. "Easiest thing in the world. The technique for separating isotopes is pretty well established by now. I've improved on it immensely. I've done more than merely shift isotopes within the body. I'm able to separate them entirely, make two separate human bodies, two separate entities, where one existed before, each composed of a unit set of isotopes. I've done what nature has merely fumbled at doing. I've taken the two personalities and clothed them in visible form for the first time in the history of the universe!"

BASCOM gasped. So that was what was taking place within the tank. He shrank away from its implications, even as Ken had done a while before. But Stubbs thought his gasp was one of awe for his genius.

"In that tank," pursued the scientist, "is a nutrient gelatin, properly treated to carry an electric current. The injection I gave Horty contained, beside a powerful narcotic, a saline solution to promote conductivity within his body. I am passing a current of extremely high amperage and low voltage through the gelatin. The body dissociates into ions, and, following the laws of electrolytic separation, these ions migrate through the gelatin very slowly from the positive to the negative electrode. But the speed of migration is not the same for the various isotopes of the same element. The lighter isotope ions move faster than the heavier ones. And the lighter ones are invariably those elements which make up ninety-nine per cent of the whole.

"In other words, the heavy, dominant personality will reach the negative electrode first; the lighter, recessive personality will lag behind."

"But they'll both be mere dead aggregations of atoms," Bascom protested. "You've murdered a man."

Stubbs smiled bleakly. His lips parted, as if to speak, when Ken, standing at the controls of the tank, absorbed in the drama within, shouted excitedly. "I think we've reached peak load, chief."

Stubbs rushed to the side of the tank. Bascom followed with lagging feet, oddly reluctant. The larger, heavy cloud was clustered now close to the base of the negative electrode. Outlines were gone, all trace that once it had been a human body. A mere mist trailed backward toward the positive electrode, faded almost to nothingness. Then it thickened gradually until, some five feet away, it became a small, thin cloud of migrating ions.

"Test it with the mass spectograph," Stubbs ordered, eyes glinting with strange lights. But Ken was already at the instrument. Two long tubes extended into the tank, three inches apart, and connected outside with the spectrograph. Their ends protruded exactly to the point at which the cloud of ions was vaguest.

Ken opened a valve. There was a hissing sound as a tiny amount of the gelatin sucked along the two tubes into the chamber of the instrument. He then adjusted sights, watched intently. When he lifted his head, it was hard for him to keep his voice matter-of-fact, coldly scientific.

"The division is complete," he announced. "All the light ions are in the right-hand sample, the heavier ones are wholly to the left."

Stubbs raced swiftly to the master switch, opened the interlocking knife edges. The current shut off; the gelatinous substance within the tank heaved, shuddered, and came to a deathly quiescence. The two blobs of matter hung motionless in its depths.

The scientist returned to a huge, camera-like affair that faced the tank. He swung it slowly until its great lens was focused sharply on the larger blob of matter. He pressed a button. A violet glow sprang out in a cylinder of radiance to bathe the formless mass of ions and their supporting medium with its eerie light.

"The experiment is through, finished." He turned to Bascom exultantly. "We've done it before with animals; now it has been successful with human beings. You've just watched something epochal, something that may mean the beginning of a new era for the world."

"I don't understand," the doctor stammered, staring at the still formless cloud. "Horty is dead, vanished, even though you did split him up into his component isotopes."

"Not at all. This machine is my crowning triumph. I call it the 'reintegrator.' That ray you see is a complex of a thousand different wave lengths. They come from a pattern within, a pattern which corresponds exactly to the form of the human body.

As they impinge on the disorganized ions, they exercise a selective influence, and compel the various atoms to migrate to the particular wave length to which it is attuned. There will be formed with the gelatin an exact replica of what had once been James Horty. Watch!"

Bascom watched, and felt the hair bristle on his neck, all over his body. Slowly, but surely, the vague, amorphous mass was taking shape and form. As the violet light continued to glow steadily and strongly within the tank, the cloud lengthened, shifted with internal movement, showed strange, wavering outlines. The outlines hardened; the mass grew darker and more solid. Before the doctor's aghast gaze creation was taking place. Legs appeared, arms, fluid as yet, but shaping into plastic form. Then a face—a terrible, hideous thing.

SUDDENLY the whole mass shuddered as if from some strange inner compulsion, and behold! Jim Horty lay motionless, nude, eyes closed, near the negative electrode, even as he had lain, hardly an hour before, at the base of the positive electrode.

Dr. Bascom gave vent to a strangled cry, jerked forward. There was no change, no slightest difference that he could see.

"Naturally"—Stubbs answered his unspoken thought—"over ninety-nine per cent of his physical elements are present. You wouldn't expect to notice any difference. Even a scale would show him only about a pound lighter than before."

"Is—is he alive?" Bascom whispered.

"Of course. There would be no point to the experiment otherwise. As soon as I remove him from the gelatinous base, and the narcotic wears off, he'll awake as though nothing had happened." Stubbs chuckled, and to Ken there was something inhuman about that chuckle. "Of course, he'll be a new personality. It may be a close approximation to his one, or it may prove entirely new. It all depends on how powerful his recessive personalities were, to what extent they masked this particular dominant. Remember, he is now composed of a pure set of isotope elements."

The doctor shifted his eyes fearfully to the tiny cloud of formless ions farther up the tank. "And—that?"

"The heavier, slower isotopes," Stubbs explained. "Less than one per cent of the total body, as you see. Yet containing the same relative proportions of the elements of Horty's body as the other. It was a much more difficult problem to bring that personality to life, but I solved it. The reintegrator will form the pattern of the body, just as in the other case. But it will be a mere ghost, a tenuous thing. Naturally, for one per cent of matter will be spread over a volume of space that normally holds one hundred per cent.

"But I will feed the necessary additional elements into the tank, and, under the influence of the pulsing waves, they will penetrate the area and arrange themselves selectively in their proper places. Food for the growing body, you might consider it. Within a few hours another James Horty will lie side by side with the one now visible."

Stubbs was already moving toward the reintegrator. But Ken Craig was there ahead of him. His face was white with strain, but his voice was steady.

"I've gone along with you this far, Mr. Stubbs," he said, "even though it was against my better judgment. I told you, and I still think, we are playing with incalculable forces, forces that may prove entirely beyond our control. Nowhere in nature have we found isotopes in their pure, elemental form. Always they are mixed in definite proportions with their fellows. There must be some reason for it, some stability that is thus acquired. We're trying to change all that. We're doing more; we're working with human beings, human characteristics, the most explosive possibilities in all nature. You know as well as I the status of cases of dual or multiple personalities. They are pathologic, diseased. There is always something wrong about them, something abnormal."

Ken took a deep breath, went on: "As I said, I was willing to go along up to this point." He pointed to the still immersed, still unmoving form of Horty. "That particular isotopic form is incalculable, but fairly safe within certain limits. It was the dominant, the norm to a large extent, of the being the world knew before as Horty. Very likely he will not prove appreciably different. But that other Horty, the one who still is a cloud of unrelated ions, the one-per-cent being whom you wish to build up into a whole man—what will he turn out to be? We have no way of telling. The animals we worked with could give us no answers. Their physical forms and properties were the same as those of their mates, but we knew nothing of their intellectual, their emotional processes.

"This Horty will be a pure recessive, something that never existed before in the history of the world. What monstrosity may he not turn out to be? What danger may there not be implicit in him for the rest of normal humanity?"

"Stuff and nonsense!" Stubbs interrupted angrily. "We've been over that ground before. The books are full of cases of dissociated personalities; my brother was an example. None of them was a monstrosity. You're letting your imagination run wild, Craig."

"But they," Ken argued, "were all compact within the same body. The other personalities, though dormant, must surely have had some braking quality, some restraining influence. Here we are separating them completely, removing all restraint, all inhibition. Remember the story of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde."

"Bah! A scientist citing fiction!"

"Sometimes," Ken answered seriously, "a novelist's intuitional genius hews mighty close to the truth."

Stubbs' face darkened. "I've wasted enough time listening to your silly croakings," he snapped. "Now get out of my way and let me go on with the experiment."

Ken squared his shoulders determinedly. Come what may, he would not permit that other Horty to be reintegrated. For a second the two men glared at each other. Then Stubbs moved forward.

"Just a moment." The scientist jerked around at this new interruption. It was Dr. Bascom, red of face, breathing hard.

"What is it this time?" Stubbs growled.

The prison doctor spoke rapidly: "In the absence of Warden Parker I am in charge here. Mr. Craig has said enough to convince me that he is right. I will not allow you to proceed any further."

"I have the governor's order," the scientist told him furiously.

"I've read it," Bascom responded quietly. "It states that James Horty be turned over to you for experimental purposes. It is not a pardon; it says nothing about remitting his execution as a condemned criminal. In the absence of higher authority I shall construe it myself. Horty must die according to law."

STUBBS' hands clenched violently; his eyes blazed. So menacing was his attitude that Bascom shrank against the wall. "Not," he ventured hurriedly, "that I'm stopping your experiment altogether. Horty must die. That—that part which is still unformed is Horty. If that dies, the law is satisfied. The other Horty is yours—to live, to do with as you please." One finger was close to a signal button. "If that is not satisfactory, I'll have to call the guards."

For a long moment Stubbs stood stock-still, clenching and unclenching his hands. The veins on his forehead swelled dangerously; his eye swept from defiant assistant to Bascom and back again. Ken had not moved from the controls.

"Very well then," he acquiesced suddenly. "Craig, help me lift Mr. Horty out of the tank."

Ken's withheld breath exploded with relief. That was better. He was sure Stubbs would soon realize the justice of his argument, agree with him. He sprang to the mechanism that actuated the crane at the negative electrode. The wire cradle dipped swiftly into the gelatin, closed beneath the immobile figure and lifted it, dripping blobs of jelly, out into the open.

The agitation of the jelly substance scattered the small cloud that had hung suspended in colloidal solution, roiled the ions into irreplacable confusion. The other Horty was no more, was now dead scientifically as well as legally. The letter of the law had been observed. Horty had died, under the auspices of the State, yet Horty still lived. A paradox which occupied some space in the prison doctor's thoughts, but none at all in Ken's. He was a scientist, not a lawyer.

Together, the two scientists heaved at the body, carried it to a specially prepared table. Light-radiant machines pulsed into action. Healing, life-giving radiations glowed over the rigid limbs.

The tension in the room reached insupportable heights. The three men watched eagerly, waiting. Would the isotopic Horty come to life, as the smaller, less highly organized animals had done? If so, what would he be like? Questions that could only be answered by the thing that still rested stolidly on the table. In the minds of at least two of the three the sharp dispute of a minute before was forgotten, a sealed book.

Seconds passed, grew into minutes; the minutes ticked off interminably. And still Horty did not move, did not breathe. Strange emotions stirred in. Ken. As a scientist he felt sickening despair at the apparent failure of the experiment. As a man, a human being, he was secretly glad There were implications in its success that he feared to face. His gaze clung to the extended body. It was Horty in every lineament and feature.

The man's eyelids fluttered suddenly under the beating light; his limbs twitched; the warm color of life infused his limbs. A simultaneous exclamation broke from the three men. They remained rooted to the ground, unable to move. It was a resurrection of the more than dead!

Jim Horty yawned, opened his eyes, looked bewilderedly about him. Slowly he raised himself to a sitting position on the table. He blinked in the dazzlement of the lamps.

Ken sprang forward, turned them off. "You're all right now, Horty," he soothed. "Take it easy. Here are your clothes."

THE man looked at him, then at the others with a puzzled, abstracted air, then he looked down at his ill-fitting stripes. He made a gesture of distaste, but he put them on obediently. Then he swung to the floor. A shudder rippled over him. He passed his hand over his eyes, as if trying to obliterate an awful vision.

"You know," he said slowly, and Ken noted with thumping heart that, though it was the voice of Horty, yet the diction, the modulations, had changed, become softer, more precise, "I had a dream, and it was a terrible one. I must have fallen asleep."

He looked again at his prison clothes, at Dr. Bascom. Then he smiled wryly. Somehow his brutish features were suffused with new light. "I'm to be executed, am I not? Well, I'm ready for it. The sentence was fair and just. I was a murderer. Funny though," and again that puzzled look crept into his eyes, "I must have been crazy, doing the things I did. Robbery! Murder! Why, I—I wouldn't hurt a fly! O.K., Dr. Bascom. Let's get over with it."

The prison doctor's eyes were literally popping out of his head. His mind whirled incoherently. His pudgy finger trembled toward the tank. "You—you were——" But the doctor couldn't go on.

"What the doctor is trying to say," Ken broke in sharply, "is that you have been pardoned. We just received word from the governor. You're a free man, Horty."

The reintegrated man stared at him incredulously. Then, surprisingly, tears rolled down cheeks that had never felt their channeled coursing before. "Thank God!" he murmured reverently. "It is beyond my deserts. My crimes were many and horrible, and should have been expiated. But now——"

His shoulders squared. Already the heavy, cunning set of his features was subtly changing, shifting with inner transformation. "New life awaits me. I feel things stirring here—inside." His hand went to his breast. "I want to learn, to do things to help my fellow men, to keep them from the paths that I once trod."

Ken thrilled with glad relief. The miracle had happened. This strange, new personality, this being who had sloughed less than a hundredth of his former being, was refined of all dross in the isotope reintegration. There was no question about it. Horty's tones rang with sincerity, with conviction. Ken's glance shifted to the murky diffusion in the tank, and shivered suddenly.

What unutterable evil must have inhered in that minute residue, to have masked this greater personality, to make Jim Horty what he had been—a vicious criminal without a single redeeming human quality! Stubbs must see now that he was right, had been terribly right all along. Never again would he attempt to associate that dissociated, discarded personality!

Meanwhile the scientist was staring with devouring eyes at this being who was incredibly his own creation. He felt drunk with god-like powers. Fame, power illimitable, beckoned dizzily. In his long, bony hands rested the future of the world. As in a glass, darkly, he saw the marvelous possibilities ahead. A race of beings, dissociated into pure states, no longer inhibited by clinging, dragging personalities! What might they not achieve!

But Ken had sensed the elements of danger, was even now revolving in his mind the means of eliminating them. Not so Stubbs. His single-track brain rejected all compromise contemptuously. His fanatical regard for science, for certain still inchoate thoughts, permitted no social elements, no humanitarian aspects to interfere with the course of pure experiment. Craig and Bascom had stopped him this once. A grim, unpleasant smile played over his angular features. Next time——

THEY TOOK Jim Horty back with them to the Stubbs laboratories on the outskirts of the metropolis. They hustled him out secretly, wrapped in a muffling overcoat, and whizzed him in a shade-drawn sedan down congested arteries of traffic. Dr. Bascom and Warden Parker had insisted on that. There was to be no publicity until they could communicate with the governor and clear themselves of official responsibility in this very complex and unprecedented situation.

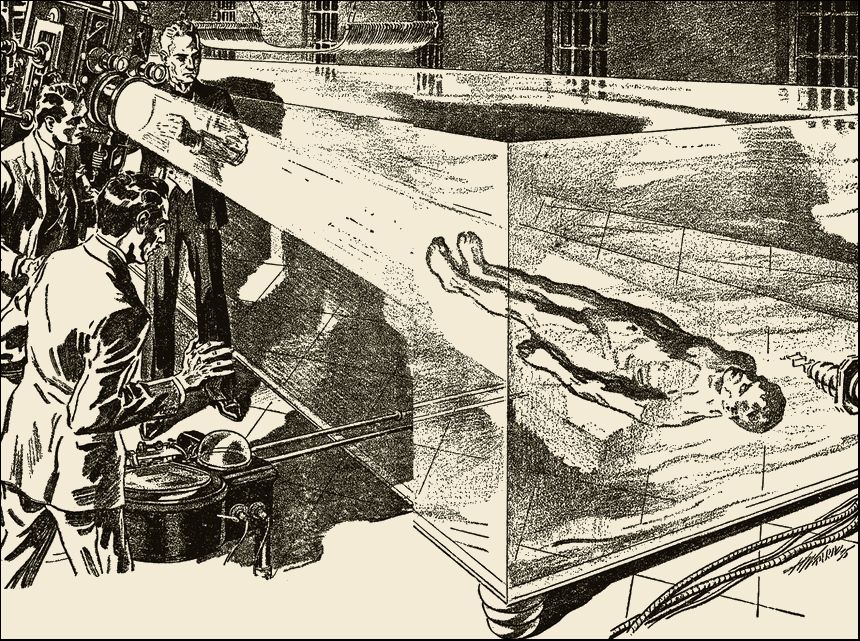

Yet they had not escaped unobserved. An enterprising reporter, who had smelled a story in the abrupt refusal to admit outside witnesses to the execution of the notorious Jim Horty, lurked outside the prison walls, waiting for something to break. He saw the huge gate swing open, the long, black-shrouded car slide through. Suspicious, alert, he followed his hunch, kicked the starter of his ancient car into life, and rattled after it in close pursuit. Traffic being what it was, he was able to keep the speeding car in sight.

When it turned into the side road leading to Malcolm Stubbs' heavily endowed laboratories he was sure he had made no mistake; when, his car half hidden by masking shade trees, he saw Stubbs and his assistant, Ken Craig, emerge, and solicitously help down a figure swathed in a huge coat, his excitement grew. When, just as the trio crunched up the gravel walk, the coat collar fell away momentarily to reveal the only too well-known features of the criminal, the news hawk knew he had a whale of a story.

One hour later, to the dot, wild headlines flooded the city streets.

JIM HORTY, NOTORIOUS MURDERER,

SPIRITED SECRETLY FROM JAIL

ON MORN OF EXECUTION.

SEEN IN CUSTODY OF FAMOUS SCIENTIST.

Within an hour and a half hordes of reporters were clamoring for admission to the laboratories; Warden Parker was denying himself to all and sundry; the governor, immured behind bodyguards in the executive mansion, had discreetly disconnected the long distance telephone. The story had broken with a vengeance!

But before all that happened, another drama, more personal in its nature, and less world-shaking in its implications, was taking place within the close confines of the Stubbs laboratories.

The three men had hurried into the living quarters. Horty sagged into a chair, still physically unstrung from the terrific transformation he had undergone, still mentally fumbling to express the inner changes that he felt.

Ken shrugged his coat off eagerly. He was brimming over with plans, with new experiments which opened before him in never-ending vistas at the triumphantly successful conclusion of this crucial test. He wanted to get into the laboratory at once, to suggest certain problems to Stubbs. He had forgotten completely the late unpleasantness in the converted workshop of the prison.

But Stubbs had not. He had sat stiffly in the car while Ken drove, wrapped in impenetrable silence, nursing his anger, maturing certain plans of his own.

"You had better put your coat on again, Craig." His voice was tinged with venom.

Ken stopped short. "Why?" he asked in some surprise. "Are we going out?"

"You are going out," Stubbs answered vindictively.

"What do you mean?"

"I mean, Mr. Craig," Stubbs retorted, "you are discharged, fired, no longer in my employ."

Ken braced himself. "I see," he said quietly. "You want your assistant to be a 'yes-man.' You want no brake on your inordinate ambitions. You are a great scientist, Mr. Stubbs, but you haven't the true scientific spirit. I saved you a little while ago from an experiment that might have ended disastrously, not only for us, but for the human race. You are now venting your spite on me for that; you are afraid that I might try to prevent you again. You are right. I would. I'm warning you again. Think long and hard before you even repeat what we have done so far. Make sure there are no secret defects; wait at least a year for them to appear. That is the way of science; that is what distinguishes research from charlatanry."

"Get out!" Stubbs growled, his voice thick with passion.

"Good-by," Ken answered evenly. "And remember what I said."

Slowly he turned toward the door.

It was a wrench, this being cast off at the moment of fruition. He knew that Stubbs wanted to hog all the limelight for himself. That did not matter. Ken preferred to remain in the background, even though he had contributed toward this particular bit of work more than Stubbs was willing to admit. But the epochal experiment was only beginning.

Horty, the pure isotopic man, was not merely a scientific problem; he was a human, a social problem. Stubbs was not the man to cope with that side of the situation properly. Ken felt a sinking sensation. What did Stubbs intend doing next?

Horty stared bewilderedly from one to the other during the altercation. Somehow his new personality instinctively trusted Ken Craig, and just as instinctively shrank from the cold angularities of Stubbs.

"Mr. Craig!" he called suddenly.

Ken stopped, turned, looked at him inquiringly.

Horty blushed—a novel sensation. His heavy features worked with strange emotion. "I—I would like to go with you," he stammered diffidently.

"No you don't," Stubbs snarled. "You stay here with me, as long as I want you. You're my experiment," he was shouting now, "and I'm not through with you by a long shot."

"But I don't understand," Horty answered helplessly. "I thought the governor had pardoned me, that I was free."

"Free? the scientist echoed sardonically, and laughed. It was not a pleasant laugh. "You're dead, Horty, do you understand? The legal part of you is back there in prison, scattered into indistinguishable atoms. You're just a resurrected chattel, a mere part of a man, an experimental creature."

A frightened look crept into Horty's eyes. "Is that true, what he's saying?" he appealed to Ken.

The young scientist controlled his seething anger with an effort. He had not known Stubbs could be so brutal. "Only in part," he said gently. "But I'm afraid you'll have to stay here until I can get in touch with the governor."

"The governor will back me up," Stubbs informed him nastily. "I have enough influence for that."

THAT afternoon, ensconced in the home of an old college friend, Ken saw the newspapers. The storm had broken in a torrent of headlines. Stubbs, in his eagerness for adulation, for fame beyond that of any living being, had broken his pledge of secrecy. The doors had been thrown wide open to the reporters. Stubbs had spoken on and on, had squeezed the last ounce of publicity from the interviews.

Horty had been exhibited, prodded, as though he were a guinea pig. Nowhere, in all the innumerable details, was there any mention of Kenneth Craig. It was Stubbs, Malcolm Stubbs, from beginning to end.

Bill Maynard threw the papers down with a chuckle. "You evidently were the janitor, or housemaid, in that establishment, Ken."

William Maynard had roomed with Craig at college before their paths diverged into their respective fields. He was a psychologist of repute, one of the younger generation who was pushing brilliantly to the fore. He dismissed as nonsense the mystical terms with which psychology was all too often impenetrably enwrapped. Psychology was a science, he proclaimed, or nothing at all. As such, its practitioner must have a good working equipment of the other sciences, and must discard as idle theory all that was not susceptible of rigorous proof.

Craig groaned. "That doesn't bother me one bit, Bill," he said earnestly. "I'm thinking of poor Horty for one; and the future of the human race for another."

Maynard sobered. "You're right," he answered thoughtfully. "This business is right down my alley. It's the biggest, most important discovery since—since—why, blazes, man, it's the biggest in the history of mankind! Making two human beings where there was one before. Splitting a man into his pure, component parts. It's tremendous; it's more, it's ghastly. I know a little something about the workings of the human mind. You can't take away what was an integral part without hell popping somewhere, sometime. Mark my word, we're not through with Horty by a long shot." Which was a prediction to be fulfilled in a most unexpected, astonishing way.

When Ken was finally able to break through to the governor, it was too late. Stubbs had brought his powerful influence to bear first. Ken was informed politely, but firmly, by a third assistant secretary, that the new creation that was Horty was the exclusive ward of Mr. Malcolm Stubbs, the great scientist. And that was that.

Ken lived in seclusion at Bill Maynard's for the next few weeks. His friend had generously given him the run of the house, of his psychological laboratory, and also sufficient money to provide for his modest needs and even more modest equipment. There were certain tests Ken wanted to make, even though he could not hope to duplicate the very expensive and elaborate resources of the Stubbs endowment.

For two weeks the sensation grew and grew. The fact that there was a War in Europe, pregnant with sinister possibilities of universal embroilment; the fact that the West had broken out in a rash of fierce, bloody strikes; the fact that China was going Communist and India was in revolt, were all relegated to inside pages, next to the obituary columns, and wholly overlooked by the average man.

Scientists trooped from all over the world to the Stubbs laboratories; countless thousands of sight-seers milled day and night before the heavily guarded portals, battling for a glimpse of the man who had been through the shadow of death, and returned, a strange, new personality.

The "Isotopic Man," he was christened by a phrase-making editor, and the name stuck. He was examined, prodded, exhibited, lectured on, his subconscious probed, his unconscious, too, by psychologists picked by Stubbs.

Bill Maynard applied for permission and was turned down. Horty was given intelligence tests; lie detectors were strapped to him; questionnaires, sensible and silly alike, bombarded his bewildered head. In short, he was not a human being; he was a guinea pig devoted to the cause of so-called science.

Ken fumed. Whatever chance there had been of calm scientific consideration of the results of their remarkable experiment was gone forever.

"He should have been placed in normal human and social surroundings," he raged into Bill's sympathetic ear. "Then and then only could we have determined whether a pure dissociated personality was advantageous to the individual himself and to society, or not. But now, with this horrible ballyhoo and roar of publicity, nothing that Horty may develop into will mean a thing scientifically."

THE uproar continued, grew to hurricane proportions. Stubbs revealed himself as a master of artful propaganda, as a genius for self-advertisement. The whole world laid all else aside, lapped up with insatiable thirst the endless bulletins that paraded from the Stubbs laboratories. The investigation of the imported psychologists, scientists, sociologists, what not, were put in printed form and sold by the millions.

Ken and Bill read them eagerly. The men were competent in their fields. The reports, as far as they went, were honest. There was no question that James Horty was a distinctly new personality.

The criminal, the cruel murderer, the man with the twisted brain and the low cunning of the underworld, had vanished. The new Horty was humble, kind, sensitive to the sufferings of the tiniest insect, eager to learn, and withal, mightily bewildered by the tremendous hullabaloo of which he was the center.

Bill read them through and tossed them across the room with a profane gesture. "Superficial hooey," he remarked disgustedly. "Tests any child could give. The all-important things have been left discreetly untouched. What, for example, has happened to the vacuum created by the loss of the heavy isotopic personality? He is not a whole man; he is only ninety-nine per cent of one. Has he been confronted with any moral situation which requires quick, volitionless decisions? How have his instincts been affected? A million and one problems that have been left untouched."

And were to remain untouched. For soon the Machiavellian hand of Stubbs disclosed itself—what he had been secretly planning for throughout the unprecedented exploitation.

One day the bombshell burst. The newspapers fairly shrieked with it. A hundred selected members of the unemployed were to be subjected to the dissociation apparatus of Stubbs, were to be reintegrated as pure isotope personalities. The way had been prepared; the proper officials had been convinced.

"Look what happened to Horty, the condemned murderer, the man whom society had given up as hopeless," Stubbs had argued to the high and mighty individuals whose consent was necessary. "If such a remarkable transformation occurred with such unpromising material, what might we not expect from men higher up on the scale. After all, these unemployed are a drain on the community. The reason they have lost out in the struggle for existence is because their separate personalities are constantly clashing constantly inhibiting each other, and making their net efforts futile."

This, of course, was a wild generalization on the part of Stubbs, based on no ascertainable evidence, certainly on nothing involved in the investigation of Horty's case. But the highly placed officials did not know that, and Stubbs was now a figure of international importance.

Furthermore, anything that would take these men off relief was eagerly to be grasped. Taxes were mounting heavily, and certain powerful business men were complaining. So consent was granted, all in the name of science.

Such was the power of propaganda that the idea was at once universally acclaimed. No one raised his voice in objection; no one, that is, except the selected hundred and their families. But their protests were swept aside as impertinent and showing a dangerous tendency toward radicalism.

"What do these ignorant protestors against the march of scientific progress expect?" one influential newspaper editorialized indignantly. "That they are to be kept on the relief rolls indefinitely, at the expense of more capable and more industrious citizens? Here is a chance for them to be remade, so to speak, so that they may earn their own livings, and not rely supinely on the bounty of others, yet they protest. Protest, forsooth! If anything proved the necessity of their submission to Mr. Stubbs' process, it is the very fact that they do object."

Ken Craig and Bill Maynard objected, too. But no one listened. One editor who took the matter up with Stubbs was told that Craig was a disgruntled employee whom he had been compelled to discharge for utter incompetency and worse, and thereafter Ken was persona non grata in all the forums where public opinion is plastically molded.

So, with a fanfare of trumpets and editorial handsprings, the great experiment went through. A huge tract of land was set aside for experimental purposes. High, barbed fences surrounded the hastily erected buildings; armed guards patrolled the grounds day and night. The disconsolate men were torn from their weeping families and hustled into the inclosure. A series of tanks had been set up, with a multiplication of mass spectrographs, reintegrators, electrical generators, healing rays, and other essential equipment. Stubbs was preparing for large-scale production. Funds were unlimited.

THEN came the fateful day. The unemployed were narcotized in batches, thrust into the tanks of gelatin. Duly they were ionized, dissociated, reintegrated. This time there was no Ken Craig to croak warnings. Furthermore, a certain military gentleman had been tremendously interested in the proceedings. Not, you understand, in their scientific aspects, and certainly not in the possible raising of the ethical standards or mental ability of the Isotope Men. It was the physical duplication, or triplication even, of available cannon fodder that caught his undivided attention.

Why, he argued, should this country wait for the slow, natural processes of birth and growth? Here, at one swift stroke, it was possible to double the man power of the nation. His mind dazzled at the glittering vistas it opened, of tremendous armies called literally into existence with the aid of a scientific wand. He saw himself in the role of a new Alexander, a new Genghis Khan. The economic and social dislocations to a country already staggering under a peak load of unemployment did not enter his simple calculations. He was a soldier, a machine geared to one task only—war! So Stubbs had the necessary backing for what he had secretly intended all along.

Accordingly, the reintegrators were focused on all the inchoate masses of isotope atoms as they moved with varying degrees of speed through the specially treated gelatin. In five of the hundred cases, three personalities had dissociated themselves under the selective thrust of the tremendous current.

The dominant isotopes, the ninety-nine-per-cent men, were easily handled. The technique had already been mastered, thanks to Ken's unheralded, unacknowledged researches. The one-percenters, or fractions thereof in the case of the triple dissociations, required more careful consideration. Here, though Ken had worked out the theoretic answers for Stubbs, more than once the great scientist fumbled, and wished vaguely that Craig was back.

Very carefully and very slowly the requisite elements were injected into the misty, ghost-like wraiths of the unformed men—in tiny dosages, in fixed, unalterable proportions. And all the while the reintegrators kept up their steady patterned beat of rays, molding the new material into the interstices of the sketchy personalities, filling them in gradually.

It was a delicate process, and Stubbs did not possess his former assistant's sureness of touch. As a result there were many casualties, personalities that vanished again into irretrievable conglomerations of atoms. And there were others that did not vanish, that actually came to life. These, because of the bungling technique, were such monstrosities, such frightening apparitions out of a mythical, wonder-working past, that Stubbs, secretly and in scared haste, destroyed them with powerful corrosives as they lay quiescent, immobile, within the transparencies of the gelatin.

For minutes after, he sat gasping and shuddering in his chair. He had been given an intimate vision of the innermost hells of deformity, of things that only a Doré or a Daumier could have drawn. Suppose, he thought with a shiver, these physical gargoyles he had just destroyed had mental counterparts, hidden underneath the normal human exteriors that lay in the other tanks. Was that whippersnapper, Craig, right, after all? Were these recessive isotopes pure, unmitigated evil, held only in check by the dominant personalities? Was he playing with forces that might prove uncontrollable?

It was only for a moment that these doubts assailed him, however. He even laughed sardonically at himself. He, the great Malcolm Stubbs, pausing in his triumphant career because of silly warnings. The experiment was successful. There was no doubt about that. Of the dominant isotopes, every one of the hundred was even now stirring back to life under the ministrations of discreet assistants, chosen more for their manual dexterity and humble fidelity than for brilliant scientific achievement. And of the recessive personalities, some fifty-odd were salvaged, expanding with the warm hues of life under the healing rays. An excellent percentage, Stubbs exulted in righteous self-satisfaction.

The hundred dominant isotopes were paraded for the delectation of a wildly acclaiming world. Scientists went to work upon them immediately. The results were astonishing. These had been originally men of average intelligence, possibly a trifle subnormal, according to the good American gospel that talent and industry must necessarily win material success.

NOW, however, their intelligence quotients ranged from 140 to 160, evidencing remarkable mental agility that fell just short of genius. Nor, this once, were the figures misleading. Placed experimentally at their former jobs, they outdistanced all their mates, shot meteor-like to the top of the heap. Labor-saving devices, efficient short cuts, machine improvements, were suggested by them in rapid succession. Their hands were deft, their brains nimble.

Big business was in an ecstasy. Profits increased mightily in the industries favored by their presence. It was possible to cut down on working staffs. As a result normal human beings found themselves swelling the ranks of the unemployed. A clamor arose for more of these marvelously efficient isotopes. This time it was not necessary to conscript subjects. Those who had been thrown out of employment volunteered eagerly. The number of applicants grew into the thousands, the hundreds of thousands.

Stubbs set up auxiliary laboratories, turned them out in machine batches. A driving fanaticism held him to his task. His ego expanded, inflated to tremendous proportions. His name was a household word; he was mightier than kings and dictators. The new isotopes were now of all classes.

Struggling authors, imitative painters whose work had never sold, routine laboratory technicians, plodding business men, dissatisfied with their present lot, went eagerly into the dissociation tanks.

Within a month the Isotope Men had made a bloodless conquest of the United States. Hacks became geniuses; petty storekeepers grew into captains of industry; obscure scientists developed world-shaking theories of Einsteinian proportions.

This made for unforeseen complications. The former leaders in the arts, in science, in industry, were being ruthlessly thrust aside by the coldly efficient Isotope Men. No longer were they the salt of the earth; now they were average, or even subaverage. A wail arose. Then one of the cast-off chemists, a former Nobel winner, had an idea. If the dissociation of personalities made geniuses out of normal, average material, what might it not do for those who were initially men of talent, of more than talent?

Tremblingly he submitted to the bath, while his fellows waited with bated breath. The result was astounding. The isotope chemist within a week had solved problems in his field that had been deemed insoluble. A new element was added to the list of those already known, and he announced that already he was on the trail of practicable atom-smashing.

Thereupon all doubts ceased. There was a rush of hitherto world-famous men for the dissociating bath. Stubbs' resources were taxed to the utmost. A new era was dawning for the earth. A race of supermen, god-like in proportions. Humanity transfigured, rising soon above the poor planet to which it had been chained, achieving the planets, nay, the stars themselves!

Certain small symptoms were unnoted in the accelerating rush of events. Symptoms, however, that held in themselves the seeds of destruction. But for the present the future was a shimmering mirage. Malcolm Stubbs was practical dictator of the world.

But he was no fool. Already he had noted that these creations of his were outstripping him in his own special field. In short order his carefully guarded secret process would be duplicated, improved on, and he, the only begetter and initiator—you see, he had by this time forgotten that Kenneth Craig had ever existed—would be shouldered aside just as the leaders in other fields had been.

For in this new world of Isotope Men there was no room for pity, for compassion, for the nice amenities of life. They were supermen, hard, efficient, ruthless—with the possible exception of Horty. No inhibitions held them back; no recessive isotope personalities acted as secret brakes. They were single-purposed, driving, subject to no doubts or indecisions. Sometimes they pushed to extravagant lengths on small matters that normal people would not have bothered with. The seeds of future difficulties were there.

Nor were they exactly happy. There were times when almost unbearable aches stirred through them, when every atom, it seemed, yearned vaguely for something that was missing, for something they could not find. These manifestations, however, were rare in the beginning; and of short duration. The spasms came and passed almost immediately.

So, one memorable day, to the hosannas of an excited world, Malcolm Stubbs, stiff and immobile under the narcotic, was carefully lowered into his own dissociation bath, and two new Malcolm Stubbs appeared in due course to the sight of all and sundry.

WE have not as yet discoursed on the recessive isotopes, the one-percenters who were fed and nurtured until they became seemingly whole human beings. There had been good and sufficient reason for this. In the first place, it took time and considerable effort to bring them to that state. In the second place, it had been deemed wise to secrete them from the general view, even from the sight and knowledge of their fellow isotopes, their complementary personalities, so to speak. For they had proved somewhat of a shock to Stubbs.

In every limb, in every feature, in every bodily mark and pattern, they were twins with their counterparts. So much so that it was positively frightening, so much so that at first there were several confused shufflings in which recessives were sent out into the world and dominants placed in camp.

The military gentleman had taken charge of this second batch. It would not do to have identical twins, between whom it was impossible to differentiate, walking and living in the same paths of existence. The possibilities for confusion, for worse, were obvious.

It would be somewhat of a shock for a man to see his mirror image approaching him in the street; family life would be subjected to certain alarming or ludicrous situations, and in industry, politics, anything might happen.

So the recessives were spirited away into a huge concentration camp in the heart of the Great Smoky National Park. By the end of six months there were a hundred thousand of them. The military gentleman was in ecstasies. He trained them and drilled them daily in the use of modern arms, in the minutiae of warfare. Soon, he figured, he would have enough to start on his career of conquest. Nothing less than the domination of the world floated before his vision. And that, mind you, without tapping the regular man-strength of the country, without dislocating in the slightest the normal processes of the nation.

These recessives, too, had undergone testings. Outwardly they were counterparts of their fellows. Inwardly, however, there was considerable difference. For one thing, they were not supermen. Their abilities did not run to the arts, the sciences, to all the differentiating talents that make of the human race an endless and infinite variety. Rather, there was a certain essential sameness about them all, a certain monotony that seemed to indicate a definite bedrock of the human race.

This bothered Stubbs vaguely at first. There was something terrifying in their primitive alikeness. They did what they were told, obediently, yet sullenly. Their intellects seemed subordinated to the emotions, to deep-seated instincts. This, of course, did not bother the military gentleman in the slightest. As a matter of fact it was cause for further congratulations. Ideal soldiers, he chortled, good cannon fodder!

Yet, underneath, flashing into manifestation like fireflies on a moonless night, and as suddenly extinguishing, were certain traits which escaped the testing psychologists. A certain secretiveness, a certain furtive cunning, a certain electrical sparkling between recessive and recessive, as if they were all mystically united in a common bond of racial integrity. But their drilling, and obedient marching went on.

The new Stubbs regained easily his former leadership. His bleak fanaticism intensified; all hesitancies, all former doubts, were gone. He became Dictator of the Americas. He took over, bag and baggage, the secret plans of the military gentleman for his own use, much to the latter's discomfiture. With inward raging and outer submission, that individual took subordinate command.

Once, and once only, did the new Stubbs feel at a loss. That was in the beginning, when the recessive Stubbs was brought before him. He had had sufficient intellectual curiosity to wish to see his counterpart, and he had felt an understandable aversion to a part of him being herded to the concentration camp.

But that one experience was enough. Every atom in his being flamed out toward that other Stubbs. It was the longing of a lover for his mate, a million times intensified, a wrenching, sickening force that left him weak and trembling and afraid.

Had Stubbs been a student of the classics, as was Craig, he would have known what had happened, would have realized immediately to what dreadful consequences his violent disruption of the human complex into its pure isotopes was inevitably tending. Plato, in his Symposium, expressed the situation in words and phrases that were a remarkable prophecy of what Stubbs had actually achieved.

In the eyes of the recessive Stubbs a flame also leaped; but it was not of longing. It was the flame of unquenchable hatred for this physical counterpart. Then, almost at once, it died into blankness.

Stubbs shivered. "Take him away," he cried to his assistants. "Send him to the camp. I don't ever want to see him again." Submissively, without even a backward glance, the other Stubbs shuffled out of the room, and was lost to his sight.

DURING this six months of world turmoil and tremendous, seething events, Ken Craig and Bill Maynard remained stubbornly aloof.

While the thousands rushed for the dissociation tanks, they stuck to their laboratory, normal, whole human beings. In the new regime of supermen they were anonymous individuals, inconspicuous for learning, for dazzling new discoveries. Yet they were content.

The feeling had grown on them through the great change that there was something radically and terribly wrong about it all. They could not put exact fingers on it, but every time they encountered an isotope man the feeling struck them with redoubled force.

"As if," Ken remarked, "there were a missing element. As if any moment the whole precariously balanced structure would tumble into disintegration before our very eyes."

Yet the months passed and nothing happened. More and more went into the baths. There was hardly a man of prominence, of recognized ability and talent, in the United States, who had not been dissociated into his various personalities. Only the dull average, the great mass of ordinarily anonymous people, were still what they had always been, a natural mixture of isotopes.

Not that they wished for that undesirable state. They clamored for dissociation; they besieged Stubbs with eager cries. It was physically impossible as yet to handle millions. Those who gave evidence of superman possibilities came first. Later, years later, the common hordes might have their turn.

Meanwhile Ken worked desperately in his laboratory, doing secret things with mice and guinea pigs and poor, scared rabbits. And always, at crucial points in the experiments, he came up against a dead wall, beyond which there seemed no further progress.

"Sometimes," he told Bill desperately, "I feel as if I too should dissociate. Perhaps my dominant phase might be able to solve the problems that puzzle me now."

Bill looked at Mm humorously. "That would be jumping out of the frying pan into the fire," he observed. "Better stay your own dumb self and take no chances. Besides, there is no necessity as yet for your researches to be brought to a head. So far, the isotopes seem to be inheriting the earth."

"I have a feeling that it won't last much longer," Ken declared prophetically, and plunged back into his work again.