RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

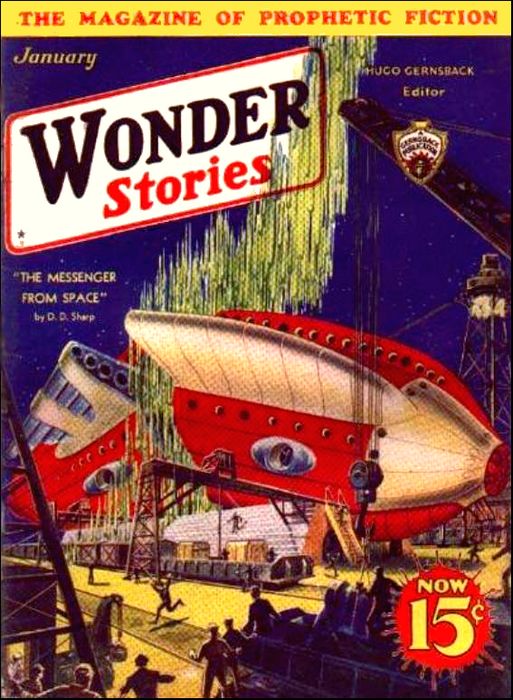

Wonder Stories, Jan 1933, with "The Memory of the Atoms"

SUPPOSE that in the dark unknown past there resided a secret of incalculable value to the race, what might be done to recover it if all records were lost? That, in a sense, is the background of this unusual story. We know that in a sense we never forget anything of our personal experiences. But do we remember what our forefathers have passed through? And if we do how might we recover that memory? And if tremendous wealth and fame were the stake, what drama, what passions might be aroused? This exciting story portrays such an intrigue for great stakes.

AT the sound of the buzzer, Emery Mackington looked up at the televisor screen on his desk and closed a tiny black switch. The prim, repressed lineaments of Miss Selden, his private secretary, appeared on the screen.

"Dr. Blake is here." Her voice was flat, emotionless.

"Good! Send him in."

Mackington shut off the apparatus and turned toward the door. His keen, sharp features were alert, tensed on the coming interview. Riches, power, fame even, depended on its outcome. His eyes were narrowed a trifle, coldly calculating, as he nodded to the man who came quietly into the room.

"Have a seat, doctor," he said cordially to his visitor. They shook hands and Harvey Blake dropped into a chair facing Mackington. He was a tall young man with sandy hair and quizzical, faintly smiling eyes. The fingers that held his shapeless hat were as long and sensitive as a musician's.

For a moment there was silence. Mackington stared thoughtfully out of the vita-crystal window at the diffused panorama of New York. A good half mile away soared the gleaming, terraced tower of the Radium Trust, a worldwide combine that held a strangling monopoly on that fabulously precious element. Equidistant to the east rose the tall smooth spire of the Metropolitan University, where Blake lectured on Mind Therapy and maintained his splendidly equipped research quarters.

Long, spidery, filament-bridges wove an interlacing web between the upper stories of the spaced structures, over which gyro cars spun noiselessly and rapidly.

Far below stretched a checkerboard of gardens and shaded walks, through which were wont to stroll leisured citizens of the New York of 2052. But today, as Mackington's eyes wandered downward, the great gardens were deserted. Instead of the usual strolling crowds, only an occasional moving dot could be seen, and that dot scurried along as if fearful of monstrous things lurking in the adjoining shrubbery. Something brooded over the city, something that even the sparkle of the afternoon sun could not dispel.

"Well?" Blake asked interrogatively, after a decent interval.

Mackington turned abruptly.

"Sorry," he apologized, "but it gripped me for a moment. That terror-stricken, dying city below and the sinister bulk of the Radium Trust gloating over it, battening on its misery, growing incalculably rich."

There was more than mere virtuous indignation in his bitterness. Mackington was one of the few independent radium dealers the Trust had permitted to exist. But when a strange cancerous-like plague of extreme virulence swept the Western Hemisphere, the Radium Trust promptly clamped down on its monopolistic sources of supply; sold the precious radium salts that were the disease's only check, at exorbitant, sky-rocketing prices. So that Mackington was left to stare dismally at silent offices. Only Miss Selden remained of all his employees.

Blake nodded sympathetically.

"I know," he agreed. "It's a terrible situation. That is why I am willing, eager even, to assist you in your plans.

But—"

Mackington placed his hand decisively on his desk. His rather cunning features wreathed into a triumphant smile.

"Success!" he interrupted. "I've found her!"

"Her?" Blake echoed in surprise.

"Yes, why not? You don't seem pleased."

Blake smiled doubtfully. "Naturally I'm glad you have located a direct descendant of Herbert Wingrove. But," he hesitated, "I rather hoped it wouldn't be a woman."

"There is too much at stake for us to be finicky," Mackington replied rather tartly.

Blake did not answer directly. "Who is she?"

A rather interesting case. A young girl of twenty-four, rather good looking, and—out of work. Some scientific training—not much—and on the verge of starvation." He rubbed the palms of his hands together. "Rather fortunate, eh doctor," he said meaningly.

Blake felt a faint distaste.

"Did she have her proofs?" he asked.

"Ample. Had all of her records from the beginning of the Public Record System." He read from a sheet on his desk. "Her name is Florence James. Her father was Carver James, chemist, killed in an explosion six years ago; her mother's maiden name was Mary Wingrove. Mary was the daughter of Frederick Wingrove, who was the son of Thomas Wingrove, son of Herbert Wingrove, born 1918, died 1964." He looked up triumphantly.

"Seems convincing enough," Blake reflected. "Did you tell her why we inserted a public notice in the News-Sheets for direct descendants of Herbert Wingrove?"

Mackington's eyes narrowed. "Of course not," he snapped. "We can't afford to frighten her off."

The young doctor's jaw tightened, his friendly smile vanished. "We've been over that before, Mackington. She must be told. The results of the operation are too doubtful for me to have any one's fate, much less a woman's, on my conscience, without her full and unreserved consent."

Mackington flushed angrily. "And I'm telling you for the tenth time, Dr. Blake, it will spoil everything. Of course she won't consent; no one in her senses would. Better let me handle the situation; I have a very plausible story all prepared."

Blake stared at him levelly. "I shall not perform the operation," he stated in flat, controlled tones.

For an appreciable interval their eyes clashed, then Mackington shrugged his shoulders in a gesture of surrender.

"Very well, let it be as you wish. But your silly quixotism is endangering the lives of countless thousands of poor unfortunates, not to speak of our own personal fortunes."

"Let me be the judge of that," Blake said coldly.

Mackington threw the switch of the televisor. His eyes masked furious fires. Miss Selden's prim features flashed on the screen.

"Please have Florence James, who is now in the General Waiting Room, come to my office at once."

"Very well, Mr. Mackington." The screen went blank.

The two men sat back in their chairs and waited. Nothing more was said between them; both were absorbed in their own private thoughts.

The door opened timidly and a girl entered. She was slight and slender, with a pale thin face from which two large frightened eyes glanced hesitantly at the men. Her green and gold costume was patched and shabby with age, yet fiercely neat. Strands of dark chestnut hair strove rebelliously to escape from under a brimless turban.

Mackington came forward to greet her. "I am glad you are prompt, Miss James. I want you to meet Dr. Blake."

Blake bowed without taking his eyes off the girl. He felt a vast upwelling of pity for this poor, undernourished girl. She was pretty, he decided, despite the unmistakable stamp of malnutrition. And her face held more than mere prettiness; there was a certain poise and dignity and quiet charm about her.

"Please sit down," he said gently.

The girl sank gratefully into the chair he pushed forward. Mackington remained standing, his hands thrust carelessly into the pockets of his gaily colored tunic. His appraising glance turned from Blake to the girl, and back to Blake again.

"Miss James," Mackington spoke briskly, "you answered our appeal for descendants of Herbert Wingrove. Your papers are in order and appear satisfactory. You are no doubt curious as to the reason for our interest. Let me explain. The world is in the grip of a terrible plague. Only the use of radium salts can check the disease. Yet the Radium Trust demands such exorbitant prices for its supplies that very few sufferers can obtain the healing element."

The girl spoke low. "My mother died two months ago because we couldn't afford to pay the price."

"Exactly," Mackington went on smoothly. "Yet nothing can be done about it. Every known radium mine in the world belongs to the Trust. The very government is its creature. And the people are dying like flies, human sacrifices to greed."

Florence James looked up at him inquiringly. "But what—?"

"I'm coming to that. Some time ago I was reading some old books on Alaska. In every volume published during the 20th century I found references to a fabulous deposit of radium ore. Mere current rumors, possibly, but the various stories bore a startling resemblance to each other. Tracking these rumors back, through contemporary newspapers, I came at last upon their point of origin.

"In the year 1947 a man named Herbert Wingrove was found delirious and nearly dead in a little known pass of the Endicott Range in the frozen marshes of Northern Alaska. His rescuers mushed him into Fort Yukon, where for weeks he raved in delirium. The burden of his ravings, repeated over and over again, was the discovery of a great radium mine, incalculably rich in ore, in the secret fastness of the Range. When he recovered, however, his mind was blank. In spite of eager questioning, all memory of the supposed mine was gone. Yet his Eskimo servant, found dying some fifty miles from the point where Wingrove had been rescued, gasped something about a rich mine, miles of luminescent pitchblende, and then died, without a word as to its location."

The girl was sitting up now, her lips parted with repressed excitement.

Mackington went on. "Of course there was a stampede. Thousands joined a new rush for the mythical radium mine; hundreds succumbed to cold and hunger and wintry storms; yet no trace of the mine was ever discovered. Wingrove himself denied to his dying day any knowledge of what he had disclosed in his delirium. His mind remained a blank as to all his wanderings through the Endicott Range. When he finally died in 1964, the excitement had slackened; the radium mine became just another fabulous tale brought in by crazed prospectors. But I am convinced that the mine exists, and that it is of enormous wealth. We want the location of that mine."

Florence had listened in a daze to this ancient story of her ancestor. She had never heard of it before, yet....

"But I... how can I help... there are no family records..."

"We want you to understand first of all, Miss James," Blake interposed, "that Herbert Wingrove never made legal claim to his alleged mine; therefore any new discoverer could effect ownership."

Mackington put up a protesting hand, then thought better of it.

"We must make this clear," Blake went on relentlessly, "because you as sole surviving descendant of Herbert Wingrove, are essential to our plans for recovering the mine. It is necessary therefore that we trust each other implicitly. We are offering you a third share in any radium deposit we may find, the other shares to be divided ratably between Mr. Mackington and myself. I want it also definitely understood that one half of the total output, before any division of private profits to ourselves, be turned over without cost to recognized governmental institutions, medical clinics and research laboratories, for the common benefit of mankind."

"I refuse to be a party to any such absurdity," Mackington broke in violently. "Let them pay for the stuff; it is ours."

"Those are my terms," Blake said coldly. "I shall not take a step further unless they are strictly adhered to."

Florence looked in bewildered astonishment at the wrangling men. Squabbling over a mine that might have no real existence; or if it had, lost in the vastnesses of bleak mountains. If it weren't for her dire personal necessities, she would have slipped quietly out of the office, convinced that she was dealing with madmen.

"But, gentlemen," she cried, "I accede to any terms you may see fit to impose, but I—I confess I do not quite see the proposition. Of what help can I be? I—I thought when I answered your notice in the News-Sheets, there would be some present employment," she fumbled painfully for words, "some present salary, no matter how small, to—to keep alive with."

"My dear Miss James," cried Blake ashamed, "of course you will be on a salary basis while you are with us. A substantial one, I might add. And the terms stand too. Mackington agrees." That worthy glared, but said nothing.

A feeling of relief flooded the girl. Let them be madmen, anything, so long as they paid, kept her from the borderline of starvation on which she had hovered since her mother's death. Time and again she had prayed that the cancer plague might smite her too, relieve her of her hopeless despondency.

Blake smiled slightly as though he had read her thoughts.

"You must think us mad," he said pleasantly, "and with reason. But before I proceed with our story, let me introduce myself once more to give a solid-seeming foundation for what will sound like a fantastic dream. I am Dr. Harvey Blake, the Mind Therapist."

Florence half rose to her feet, awed. At their first introduction she had not connected the rather ordinary name of Blake with its rightful connotations. This pleasant, unassuming young man!

"Dr. Blake, the Mind Therapist," she repeated. "Why, the whole world rings with your miraculous achievements in Mind Therapy."

Blake waved it aside modestly. "I'm afraid the world overrates me. However, let us proceed with the matter in hand. You've no doubt heard of my work with high frequency currents to stimulate the memory cells of individuals."

Florence nodded eagerly. Even the popular News-Sheets carried full details of his epoch-making experiments.

"You know then my general theory," he pursued, "that the memory of no event is ever really forgotten; that it remains dormant in our brain cells, and requires only the proper chemical, or let us say electrical stimulation, to recall it to life. I have been rather successful in a great number of cases. Men suffering from complete amnesia have been brought back to normal; the memory of past events, of childhood memories, of infancy even, have floated to the surface under my instruments. There is no question that were Herbert Wingrove alive today, I could very readily extract from his unconscious the exact memory of his lost radium mine."

"I haven't the slightest doubt of it, doctor," the girl cried. "But now, what can you do?"

Blake smiled. "There have been other experiments," he said slowly, "experiments I haven't seen fit to divulge to the world yet. It is my belief that the germ plasm carries with it the concealed memories of all one's ancestors. Hence, on proper stimulation of the brain cells of a descendant of Herbert Wingrove, yourself, I shall recover, not only your own memory, but the submerged memories of Herbert Wingrove."

The girl gasped. "You mean to say..."

Blake nodded gravely. "That with good fortune you yourself will inform us as to the exact location of the lost radium mine!"

There was a long silence in the room. Florence felt dizzy; the room swayed around her. Unbelievable, impossible! yet this young man with the kindly eyes and pleasant smile was the great Dr. Blake. If he propounded fantastic things, they must be so. Then the full implications burst upon her. Wealth, unimaginable wealth; no more endless cravings for food, for clothes that were not patched and shabby; freedom to enjoy life, to travel, to hear great music; freedom for humanity from the dreadful plague that had taken such enormous toll in lives and suffering; the end of the Radium Trust's blood-flecked monopoly! Her temples throbbed; she raised her head suddenly.

MACKINGTON'S eyes were gloating with the satisfaction of one who sees the goal in sight. The girl was about to speak.

"Before you commit yourself," Blake interposed hastily, "let me warn you. My new experiments have so far been made only on animals; none on human beings. The operation for the recovery of an ancestral memory is infinitely more delicate and dangerous than the one whose technique I have perfected for the mere overlaid memories in an individual's consciousness."

Mackington started a protest. "Really, Dr. Blake, there is no need—"

But the Mind Therapist waved him aside. "There is need. Miss James must be fully cognizant of what she is to undergo. If the operation does not prove successful, and at the present stage of my experiments, I cannot be assured of success, then Miss James will be made into an irremediable idiot, a gibbering hopeless thing to whom death itself would be a welcome release."

The girl faced him bravely.

"You will perform the operation personally, Dr. Blake?"

"I would entrust it to no one else," he assured her. "And the chances of failure?"

"About even."

Strange how steady her voice was. "Then I accept. I am ready to submit to the operation whenever you are ready."

Blake grasped her slim hand with something like tears in his eyes. He had almost dreaded her acceptance.

"If it had only been wealth for ourselves, even for you who need it so much, I would never have dreamt of subjecting you to such a frightful ordeal; but there is the fate of humanity at stake. Even if the Radium Trust released its monopoly on radium, there is not enough being mined today to treat the plague-stricken multitudes. Unless new sources are discovered, the cancerous infection will soon be beyond control."

"I am not afraid," she said in low tones, her hand still resting in the firm warm grip of the young man. Their eyes met, and Blake dropped her hand, every fiber tingling. This was going to be more difficult than he thought.

Mackington, the business man, interrupted. He pushed a paper across the desk to her.

"This is a contract form of our arrangement. Will you please read it, and if it is satisfactory, sign here."

Florence tried to fix her attention on the long legal document before her. But the phrases jumped across the paper, the words became blurred.

She looked up helplessly at Blake. He smiled and nodded his head. Florence affixed her signature to the line at the bottom. Mackington carefully blotted it, pressed a button on his desk. The televisor remained blank, but almost immediately the door opened, and Miss Selden, the private secretary, came noiselessly into the room. Her face, severely plain and angular, held no expression.

"I want you to witness these signatures," Mackington said, holding the documents in such a way that only the names were visible.

The woman nodded, and after the task was finished, quietly left the room.

Mackington folded one copy of the document and handed it to the girl. "This is yours. Be sure to guard it well; don't divulge its contents to anyone, not your dearest friend. If our secret becomes known, the Radium Trust would be on our trail at once."

Florence smiled. "I have no friends," she said simply.

Blake felt an unreasoning desire to tell her he was her friend. Instead, he said: "Please report to my laboratories in the Metropolitan University tomorrow at nine. They are in Section 6—Suite 2434. We shall start at once."

After she left, and Mackington had bid him farewell with an eager, avid air as if incalculable riches were already in his grasp, Blake wondered at something very slight and trivial. How had Miss Selden appeared so promptly in Mackington's office at the summons? The outer anteroom was some four rooms beyond. And the televisor had been blank; that meant she had not been at her desk at the time. But it was a mere fleeting wonderment that was promptly forgotten.

Yet had he been able to follow the prim Miss Selden into the recesses of a private televisor booth that afternoon, his flickering suspicion would have been fanned into open flame.

She was dialing a secret number. A face stared up at her from the televisor, cold, unwinking.

"Your number," a voice demanded.

"K 23," she answered rapidly.

"Good!" A bodiless hand thrust athwart the screen, removed the shrouding mask. A slightly rubicund face with thick sensual lips and heavy jowls gleamed on the lit screen. Yet the eyes were ruthless, domineering. Norris Benson, General Manager of the Radium Trust, had not achieved his commanding position by following the ordinary course of business ethics, slight as they are. In normal times he permitted a few independents, like Mackington, to nibble at the edges of the industry. Thus he avoided any legalistic proof of monopoly, and gave a complaisant government the necessary excuse for not acting. But at the same time the Trust did not desire such small fry to develop into serious threats. Accordingly Benson managed to insert into the offices of every independent a member of the Trust's very efficient spy system. Miss Selden, as private secretary to Mackington, was in a specially favored position.

"I have news, Mr. Benson," she spoke rapidly. "Mackington was in conference today with Dr. Blake, the Mind Therapist, and a girl named Florence James. I listened in. It's about a lost radium mine in Alaska that is supposed to be richer in ore than all the rest of the world's deposits put together." She went on with a detailed account of the conversation, the proposed operation to be made upon Florence James to recover her ancestor's memory of the location of the mine. While she spoke, a telautograph at the other end made a durable record of her report, signed it with a televised photograph of the speaker. There were no loose ends in the Radium Trust's organization.

Benson heard her through without remark. It was but another evidence of the reason for his eminence in the Trust that the fantastic story evoked no exclamations of disbelief. His face maintained its rubicund blankness, but his thought processes were lightning swift.

After a brief silence he spoke. "You will receive tomorrow, by tube delivery, a letter with our superscription, addressed to Dr. Blake, yet bearing the Section and Suite number of Mackington. This will obviously be an error on our part. See to it that Mackington gets hold of it. That is all, K 23."

The televisor went blank, and Miss Selden departed for her bachelor quarters in Residential Apartments No. 12, a bleak smile on her angular features.

Florence James wended her way through the formal gardens of the city toward the tiny unlisted old-fashioned cottage on the outskirts. There would be only a slice of hard, dry bread and a modicum of tea awaiting her, but she did not care. Visions of future comforts, of leisured ease, intertwined inextricably in her thoughts with a certain tall, pleasant young man with quizzical eyes and long, sensitive hands. The coming ordeal held no terrors, such was her abounding confidence in the wizardry of Blake.

As she hurried along—she had no money for gyro-passage—oblivious of the deserted air of the paths, the furtive, terror-stricken expressions on the few human beings who had braved the grim outdoors, something happened that brought her to a sudden, overwhelming realization.

A huge gyro-bus, completely enclosed, dull black in color, oblong, sinister, poised on its monorail in front of a great terraced Residential Apartment. A lank, cadaverous man, dressed in rusty black tunic, sat at the controls. He was speaking into a microphone affixed to the control board, in a grating voice that comported well with the general malodorous air of the ensemble.

"Deliver your bodies into the drop-chutes for incineration. No plague corpses must be held, under stringent penalties. By order of the Council for the Americas."

Over and over he repeated the gruesome refrain.

Florence shuddered violently. Gone were her rose-colored visions. She knew only too well the meaning of this formula. Every apartment cubicle in the vast towering structure was hearkening to the dismal summons. The call went out on the government wavelength to which every televisor must maintain an open circuit.

The cancerous, infectious plague had reached such formidable proportions that the great network of government hospitals were choked with patients; unnumbered thousands were perforce compelled to fight the deadly tumorous growths in the recesses of their own homes. The supply of radium, limited in any event, was still more limited by the rapacious attitude of the Radium Trust. And thousands died each day, warty with bulging excrescences, blue-green in decomposition.

The ordinary channels for removing the dead had broken down lamentably. Thus it was that, to avoid a still fouler pestilence, this desperate method, reminiscent of the primitive Black Plague days of ancient London, was being employed.

Even as Florence was held fast, in horror-stricken attitude, the top of the sinister gyro-bus opened outward; extended a funnel-like projection under the chute-opening in the wall of the Apartments, and thump, thump, bump, bump, body after body careened into the doomful carrier.

The hideous noise broke the spell that held the girl fast-bound. She screamed and fled, down one path after another—heedless of passers-by who drew back in alarm from possible contaminating contact—unresting she ran until she had reached her own bare, poverty-stricken surroundings, and thrown herself gasping upon the miserable pallet upon which her mother had breathed out her last, only a few months before.

"Mother, mother," she sobbed with hot, remorseful tears. "I am selfish, unworthy. I thought only of my own miserable needs, of avaricious wealth, and not of yourself, of poor suffering humanity. Let Dr. Blake tear me asunder if necessary, but let him discover the secret of the mine, so that the healing element may be made available in abundance to all the sad plague-stricken multitudes of earth. I do not desire anything but that. Do you hear?"

In the great white-lit operating theater of the Metropolitan University Dr. Harvey Blake was in earnest conversation with two white-gowned surgeons. They were his assistants, enormously skilled in the delicate manipulation of skull-trepanning.

Already Florence James lay white-faced, barely breathing, on the long, vitrine operating table. Local anesthetics had effectively dulled her nerve centers, yet left untouched the sensitive neurons of her brain cells.

Mackington lounged against the further wall with a feline expression, hands in tunic. Upon this snip of a girl depended fame, fortune, power.

Blake approached the recumbent girl.

"You are quite comfortable?"

Her head was strapped back, her chestnut hair shaven from a frontal area three inches in circumference, yet she managed a brave smile.

"Very well then. We shall begin."

The chief assistant, masked in aseptic white, focussed his magnifying spectacles carefully, adjusted fine screws on the radio knives attached to power-driven apparatus.

The second assistant wheeled into place a squat rectangular machine from which thick rubberized cables ran to a power-plug set in the wall. On the machine's upper surface were a bewildering array of sensitive meters, shiny chromed knobs and controls and a long movable cable that terminated in an extremely fine curved needle.

Blake checked the connections and adjustments with a hand that trembled slightly. He tried to attribute his unwonted excitement to the epoch-making experiment, to humanitarian impulses for a stricken world, to the prospect of increasing his own personal fortune even; but deep down within himself he knew it was for the poor, brave girl lying white before him. With an effort he nodded to his assistants to go ahead.

Holding the radio knife steady on its path, the first assistant made a careful incision that slit open the scalp on the shaven area. Then he laid the folds back deftly, exposing the skull. The radio knife was adjusted for greater penetration; and he went to work. Round and round the gleaming instrument bit, deeper and deeper it went. Blake was openly nervous now, even Mackington leaned forward with bated breath.

For ten minutes, the power-driven knife sliced through the bone. Nothing was heard but the slight humming of the apparatus. The girl's face was pallid, but so perfectly had the anesthetic been administered, that she betrayed no sign of pain.

Then as the thin tough blade sheared through the last section of occipital bone, at the exact adjustment for the thickness of the skull, the instrument stopped in its appointed course with a slight click. The surgeon leaned forward, disengaged the still quivering knife, and gently removed the circular section of bone. The masked face peered down at the exposed tissues; then nodded to Blake that all was well.

Blake exhaled a long sigh. His part, the most important and infinitely the most dangerous, had come. He could not tell how long his carefully husbanded nervous energy would last.

Moving to the surgeon's side, he stared down at the exposed greyish convolutions. He touched the girl's arm.

"You still wish to continue?"

"Yes." Her lips barely formed the word.

Blake turned to his high-frequency machine and snapped a switch. A motor hummed into life, filling the room with its song of power. He adjusted a micrometer knob, watching as he did so the dial of a frequency meter, listening intently to the increasing whine of the motor. He turned next to the output meter, twirled a knob until its needle crept toward a red line and quivered there in static ecstasy.

Then he scrubbed his hands in a wash basin filled with antiseptic fluid, dried them on a sterile towel, and lifted the fine curving needle.

"You understand," he said gently to the girl. "You are to relax completely, and keep your mind as free from disturbing thoughts as possible. Memory pictures, faint at first, then stronger as you let your mind drift, will float into your consciousness. At first they will be merely memories of your own past; do not disclose them; we have no wish to pry into your private life. But as soon as they relate to your father or grandfather, let me know at once."

"All right," she whispered.

His hand was steady now. The least quivering of the needle and irreparable harm would be done. He bent over, and very carefully brought the almost invisible needle tip into contact with the outer periphery of Berning cells. These tiny delicate structures control the memory functions. The outer layers hold in their convolutions the memory of the individual. This part of the operation was routine and had been performed by him time and time again. But deep within the slightly viscous layer lay the racial memory cells. At least that was Blake's theory, seemingly substantiated by his work on pedigreed mice. It was extremely difficult to get through the first layer of Berning cells without destroying them, and harder still to avoid coming in contact with certain motor cells that lay side by side with the inner layer. The least touch meant horrible idiocy, paralysis.

With tense fingers he applied the most delicate of pressures, shifting the inclination of the needle ever so slightly.

A cloud seemed to pass over the young girl's face, a startled look compounded with ineffable sadness.

"A memory has come to you of your own past?"

Florence shuddered. "Yes; it is terrible."

"Never mind," Blake soothed. "Just let the memories drift along."

FOR half an hour thereafter, while Blake skilfully shifted the needles from point to point, probing ever deeper with infinite care, trying to penetrate the individual memory cells to reach the racial memories without injuring their delicate structures, the girl went through a kaleidoscope of her earlier days. Some were sad, some pleasant, some that brought a look of horror to her careworn countenance, others that drew her lips into reminiscent little smiles.

Blake's face was drawn and tense now; beads of perspiration started out on his forehead, were instantly swabbed away with antiseptic towels by his assistants; the fine point of the sparkling needle probed ever deeper, yet still she had not progressed beyond her own thoughts.

Then suddenly, her face changed subtly. She seemed to be listening to far-off things; to be sensing unknown perceptions. Mackington took a step forward in his eagerness, but Blake, holding the powered needle steady, warned him off.

"What do you see?" he asked softly.

There was a moment of hesitation. The young girl's voice came as from a distance.

"A large room; a lecture hall; a young man sits leaning forward; he is absorbing the words of the lecturer; he looks like my father, only younger..." her voice died away.

An exclamation of triumph barely escaped Blake's lips. The three men looked on in hypnotic fascination. For the first time in the history of the world racial memories were being evoked from a living subject.

Blake shifted the needle ever so slightly; inserted its point a trifle deeper. The motor cells, dangerous to disturb, lay not a hair's breadth from the Berning cells he was probing. His face was white, his forehead gleamed with droplets of moisture faster than they could be wiped away.

"Try again," he breathed.

Once more the peculiar mask settled on the girl's face.

"My mother, a tiny girl in peculiar dress, is playing with her dolls, singing them a song."

Blake nodded. As the needle dipped deeper, events in past lives moved in rapid sequence. Back in time, back through the ordered, dignified life of her grandfather, Frederick Wingrove, back into the secret, twisted, not quite law-abiding pageant of Thomas Wingrove's colorful career. Interesting sidelights on ancient manners and customs were evoked as incidental to his turbulent life on the outposts of society. Florence lingered over them with a half-shocked smile playing around her pale lips. Incident after incident poured out in never-ending stream.

All very interesting and valuable, it was true, but Blake shook his head impatiently, and delved deeper. A little scream of pain from the girl and he released the pressure. Again details, and more details, of stout old Thomas Wingrove.

Mackington was leaning forward in his eagerness, almost impeding Blake in his work, a look of baffled rage on his countenance. Damn old Thomas, damn Blake! So near to the goal and yet so far. Why couldn't the girl leap that last barrier, come to Herbert's life?

Once more Blake went deeper, gently. Again the girl screamed. He set his teeth, withdrew the needle, turned off the power switch, mopped his pale forehead.

"Enough for today," he said resolutely.

Mackington was literally yelping.

"Confound you, why do you stop? We were on the verge of success. Another minute, and the girl would have told us what we're after."

"At the cost of her life," Blake returned sternly. "Look at her."

Florence had fainted, her lips were slightly parted; her breathing low but steady. The chief assistant was already at work. Very deftly he applied a silver plate to the trepanned portion of the skull. Then he folded back into the place the retracted scalp, and bandaged the whole tightly into place. Then and not until them, did he apply restoratives.

Mackington stepped aboard a gyro-car and was conveyed swiftly along the filament-bridge to the forty-second floor ramp of the General Laboratories Building. He was seething with resentment, all the more bitter because he knew it to be unjustified. Why had Blake stopped short just on the verge of success? Granted that the girl was screaming; let her scream another minute or so. Then they would have had the location of the mine. If the girl died, why—there would be more for his share. Blake was a stubborn ass—or was he...?

Absorbed in such unpleasant reflections, Mackington entered his own office. He did not notice the look of fright on the ordinarily repressed face of Miss Selden. The letter from the Radium Trust was in her hands, but Mackington had gone straight to the operating room in the Metropolitan University that morning, instead of first looking in at his office, as he had said he would. Had the operation been a success; had the secret of the mine been already disclosed? Then the letter could serve no useful purpose, and her spying had been a failure. Benson listened to no excuses.

She dared not ask Mackington what had happened. She was not supposed to know. Yet the black look on his keen features was heartening. It did not augur of complete, success.

She held the incriminating letter out to her boss.

"There is a letter here for Dr. Blake," she said. "It was wrongly addressed to your office."

Mackington took the letter absently. His thoughts were still seething.

"It is very strange, sir," she slid in cunningly, "but it's from the Radium Trust. I wonder what business they have with him."

"Eh, what's that?" Mackington lifted his head sharply, startled out of his black mood.

His private secretary patiently repeated her observation.

He took one swift glance downward at the superscription. There stared back at him in neat gravure: "Radium Products of the World."

Muttering something unintelligible, he dashed through the door, unheeding of the slow look of triumph that followed him, threw himself panting into his chair.

All the inchoate, hitherto absurd suspicions suddenly crystallized into tangible form. A long moment he stared at the sealed letter. Then he got up suddenly, his face set and determined. There was no slightest hesitation in his next movements. They carried him into a small laboratory. There he steamed the flap open, drew out the folded photostat insert.

It was a reckless, embittered man who leaped out of the gyro-cab in front of Nursing Residence No. 1, in which Florence James had been installed by Blake. Mackington brushed aside all opposition on the part of protesting nurses, forced his way into the pleasant sunny room. Florence was seated in an adjustable chair, gazing thoughtfully out of the wide flung window, her head swathed in bandages. Aside from a certain pallor that could be attributed to her former undernourished condition, she did not seem any the worse for her experience.

She looked up startled at Mackington's tempestuous entrance. That individual drove straight to the heart of the matter. The rage within him did not permit of polite preliminaries.

"He's a traitor; a double-crosser!" he shouted at her, waving a blue photostatic letter.

"Why Mr. Mackington," she gasped. "What do you mean? Who is a traitor?"

He calmed down. "Blake!" he retorted bitterly.

The blood drained from her cheeks. She stared at him with unfathomable eyes.

"I don't understand," she whispered, as if to herself.

"Here; read this and you'll understand only too well." He almost threw the damning document at her. "This was wrongly addressed; came to my office."

She took the blue watermarked sheet with fingers that trembled in spite of herself. The graved scroll on the top stared back at her in accusing letters of fire, "Radium Products of the World."

With an effort of will she read the rest, though the letters jumbled and pied dizzily before her eyes as the meaning slowly penetrated.

Dr. Harvey Blake,

Metropolitan University.

Dear Dr. Blake:

We are very much interested in your proposed experiment upon the racial memory of one Florence James, direct descendant of Herbert Wingrove. If the same proves successful, we agree to finance an expedition to discover the lost radium mine, and further agree to take title to the same in the name of Radium Products and your own as tenants in common. It is understood by us that title to the mine has never been vested in any person or corporation to date.

We wish you every success in your interesting experiment and trust to hear from you immediately upon completion thereof.

Yours very sincerely,

RADIUM PRODUCTS OF THE WORLD,

Norris Benson, General Manager."

Something shriveled within Florence; something that had been alive and laughing only seconds before. Her eyes focussed on infinity, blank, unseeing.

"Harvey Blake," the name was a whispered prayer, "you—did—this! I can't believe it." She turned suddenly on Mackington. "It's not true; it's not true," she cried, her voice like small beating hands. "He is too fine, too honorable."

Mackington stared down at her in amaze. Why, the girl was in love with the scoundrel! He felt a momentary twinge of pity, then it was thrust aside by his righteous rage, by the practical business man.

"A fine honorable man," he sneered, "trying to sell us both out to the Trust! The letter is plain enough, isn't it?"

She drew a weary arm across her bandaged forehead. "Yes it is," she whispered. Then suddenly she dropped her head into her arms; great dry sobs tore at her.

"That won't get us anywhere," Mackington told her roughly. "I have a plan; listen. We'll just turn the tables on the scoundrel. He tried to sell us out; we'll leave him out in the cold. Tomorrow he continues with the operation—"

"No," she sobbed thickly. "I don't want ever to see him again."

"You must," he said relentlessly. "There is no one else in the world who can perform it. When you finally achieve the memory of Herbert Wingrove, and of the mine, talk at random; fake up details of another location, make it hundreds of miles away from the true site. He will send the Trust off on a wild goose chase; in the meantime you and I will get to the real location, and claim it in our own names. By his treachery we shall gain a half share apiece instead of a paltry one third."

She lifted her head, her eyes flashing. "Do you think I care one bit about the horrible old mine. All the money in the world couldn't tempt me to see that—that—wretch again."

Mackington was taken aback. Queer beings, women! One could never tell about them. He must try another tack. Then he smiled shrewdly.

"Forget about the money," he said smoothly. "I myself am not interested in financial rewards. But think of plague-stricken humanity. Think of the men, women and children covered with horrible bloatings, their bodies turning a ghastly blue-green, suffering the tortures of the damned, all for want of healing radium. What do our personal likes and dislikes count against the tragedy that has overwhelmed the world, and to which we have the key in our own hands."

She looked at him with a long, slow look. The picture of the black gyro-bus and its horrible freight was etched in her memory. She shuddered and rose, grasping his hand firmly.

"Very well, Mr. Mackington. It shall be as you say. Humanity needs the mine; they shall have it, entire, I do not claim one pennyweight."

Mackington smiled inwardly. "Poor fool!" A scheme was slowly forming in his ever-fertile mind.

Once again Florence James lay on the white operating table under the brilliant beating light. Her face was drained of color, partly from the ordeal she was undergoing, partly from the nerve-racking experience of seeing Blake in the flesh, pretending that nothing had occurred to change their relations.

The needle was probing back again in the life of old Thomas Wingrove. Time and again Blake stopped the pressure, asked if Herbert had appeared on the scene yet. She answered in the negative wearily. An hour passed, and Blake's brows were drawn together in deep furrows. He could not keep the girl under the torture much longer. Defeat stared him in the face. There seemed an impassible barrier over which the racial memory could not pass. His hand was weary, leaden-weighted.

Then it happened, the thing he had been dreading all along. The needle slipped from nerveless fingers, plunged erratically into the thick layers of hidden Berning cells. His sharp cry of horror brought his assistants and Mackington jumping forward.

"I've killed her!" he cried despairingly. He grasped for the half hidden needle, to repair the irreparable, when Mackington shouted:

"Leave it alone. Look, look at her!"

Blake's trembling hand paused in midair; they turned to the prostrate girl. Her eyes were open now, lit up with eager inner fires. She was seeing something, something she had not seen before.

Mackington's voice cracked with insane eagerness.

"You have penetrated; you are remembering the life of Herbert Wingrove?"

Her mouth was parted, her breath coming rapidly.

"Yes, yes," she gasped. "It is all very plain."

Cunning returned to the man.

"Don't talk yet," he warned. "Wait until the memory is completed; then you'll tell us. You might lose the connecting thread otherwise." He winked at the upward staring girl.

Long minutes passed, through which Blake lived uncounted lifetimes. Victory at last in his grasp, coupled with fear for the girl, for that deep-plunged needle.

Then she breathed heavily, said weakly: "All right now."

Blake leaped forward, drew the errant needle out from piled layer on layer of cells with infinite pains and marvelous skill. It was only when the glistening point appeared that he heaved a sigh of relief. Miraculously no motor cell had been impinged upon.

The assistants stepped forward now, replaced the silver plate, sutured the scalp in place over it, and bandaged it all again. Later, if no further racial memories were required, the removed skull bone, that had been kept fresh and healthy in certain saline solutions, would be skilfully riveted into its former position, the scalp resutured, so that there would be no visible sign of the operation.

Half an hour later, Florence sat in a comfortable chair, pale but composed. Blake and Mackington were the only ones in the reception chamber.

"You poor child," Blake said softly, "you have been through Hell. Thank Heaven it is over now. Tell us what you remembered.".

The girl turned an unfathomable look upon the unconscious young man, shuddered slightly, and stated in slow composed sentences:

"I had been seeing Herbert Wingrove for some time, but only as the father of Thomas. Then suddenly my mind seemed to take a great jump. I was Herbert Wingrove, staggering wearily through a frozen tumbled land of mountains and precipitous chasms. A heavy pack weighted me down, an Eskimo servant stumbled along at my side. I suffered from hunger, from the bitter freezing cold. Our provisions were exhausted; there was no fuel, no timber, no brushwood in all that iron land with which to build a fire. We staggered out upon a grim plateau, swept bare of snow by the perpetually howling gales. The ground pitched and heaved into jumbled frozen attitudes; fantastic shapes lowered down on us at every step. The going was indescribably rough. The saw-toothed, towering mountains, cloud-enshrouded, kept sentinel watch on every side.

"I was at the end of my resources; civilization hundreds of miles to the south; I knew I could never reach it alive. Then the Eskimo pointed. Something glittered in the tumbled rock waste. I approached. The rock was essentially granitic, through which velvet-black lustrous veins ran of conchoidal fracture. I recognized it at once. Pitchblende. But that was not all. The whole surface of the mineral glowed with a soft phosphorescence. And whichever way I turned, the rocks on that strange plateau were heavily veined with pitchblende, and the phosphorescence shone out at me with beckoning lure."

The two men were leaning forward, following her story with taut interest.

"I knew at once what I had found," the girl continued, still in the memory-person of Herbert Wingrove. "I stood like one in a daze, then I shouted, screamed, danced insanely around my bewildered Eskimo. I had stumbled upon a whole plateau of pitchblende, or uraninite, and the phosphorescence showed that it was literally loaded with radium. I made a hasty survey, tried to calculate the amount of radium-bearing ore, but my mind staggered, refused to believe. There were millions of tons on the surface of that plateau; the radium contents would be absolutely fabulous in amount.

"Then I heard my Eskimo shout a warning. I glanced around. A blizzard was sweeping down the surrounding mountains, the snow was hurtling toward us in thick white blankets; the storm wind shrieked and howled.

"It was imperative that we get out of that trap before it was too late. We shouldered our packs and staggered along the back trail. Then the storm hit us, enfolded us in its icy, blanketing maw. The rest is dim. I lost sight of the Eskimo; I stumbled and fell blindly onward; then I sank into a smothering drift, and knew no more." Florence stopped. Blake's voice was tense. "But the location of the plateau; did Wingrove know where he was?"

The girl looked at him strangely, cast Mackington a swift sidelong glance, and answered slowly.

"Yes, he did; he carried compass and sextant with him. He took his bearings before the storm overtook him."

"What were they?"

A perceptible moment of hesitation, then:

"It was in the Endicott Range, just south of the Amuktuvuk Plateau; Latitude 67° 20' 18" N., Longitude 148° 12' 42" W."

Blake scribbled the figures down excitedly. Then he lifted his head.

"You have been marvelous, Miss James. Because of you the world will be able to combat the plague; the Radium Trust will be broken, and all of us, though that is not so important, will be unimaginably rich. Mackington and I shall get to work organizing an expedition at once. In the meantime you will require rest, careful nursing and plenty of good, wholesome food. Let me see you to the Nursing Apartments; I shall give orders how you are to be taken care of."

"It is not necessary, Dr. Blake," the girl said coldly. "I shall manage to get along without your troubling yourself on my behalf. Mr. Mackington, will you see me home?"

"Certainly, Miss James. I shall be glad to."

SHE rose, gave him her arm, and they walked out of the Reception Chamber, leaving a very much puzzled young man looking after them. He shook his head in wonderment: "Now what did I do to make her act that way?"

But think as hard as he could, there was no answer. He sighed, arose, and went into his library. There he took down an atlas, leafed through it until he came to Alaska. His pencil made a tiny circle around the indicated latitude and longitude. Then he tapped his teeth thoughtfully with the butt end of the pencil, and frowned.

From the girl's memory account, Wingrove could not have traveled very far in that terrific storm after the discovery of the radium mine before collapsing. Yet the newspaper reports that Mackington had delved into distinctly stated that the rescuing party had mushed into Fort Yukon with the delirious prospector. Why?

Fort Yukon was over 150 miles away, over the roughest sort of terrain. Yet here, staring him right in the face, was the little town of Coldfoot, less than fifty miles away from the indicated plateau. Surely the rescuers knew the country. Then a thought struck him. Possibly the town of Coldfoot did not exist back in 1947. He went rapidly to a historical atlas, found the map of the year 1935. There was Coldfoot, unmistakably in existence.

He frowned harder than ever at that. Then the picture of Florence James rose to blot out all other considerations.

At the Nursing Apartments Mackington turned eagerly to Florence.

"You were great," he said enthusiastically. "You put him off the track completely. Of course the location you gave him was false."

The girl turned a haggard, worn face to him from under the enswathing bandages.

"Yes," she admitted wearily, "it was." She was holding herself in, afraid to give vent to her emotions. If she did, she would crack irremediably. The world was a place of darkness, and nothing mattered. Blake, that pleasant boyish scientist, with his heart-warming smile, a treacherous, unscrupulous scoundrel! Impossible, her heart cried, but there was the letter!

She came out of a haze to hear Mackington's insistent voice. "What were the true bearings, Miss James?"

Slightly over eager, she thought, but nothing mattered.

"Latitude 65° 13' 21" N., Longitude 147° 31' 11" W." she said wearily.

He carefully masked his triumph as he jotted the figures down. Poor, simple minded fool, he thought, how easily she fell into the trap. Split with her! What for? He had depended upon Blake for the financing of the expedition; he had no money of his own. Now that was out. Well, he would take a leaf out of Blake's book. He'd go to the Radium Trust.

They would be glad to finance him, give him the same terms they offered that scoundrel Blake. No, he'd demand more. Sixty-forty would be his proposition.

While his thoughts raced thus, he was saying smoothly to the girl:

"Now you just rest up after that terrific ordeal, and leave everything to me. I shall pretend to Blake that I am aiding him in organizing his expedition; meanwhile I shall be secretly at work on our own. It will take about a week. Then I'll slip away, head for Alaska, and stake the claim in both our names. That will be our revenge."

"I shall go with you, of course," she said quietly.

"Eh, what's that?" Mackington was startled. This did not fit into his plans at all. "My dear young lady, this will be no picnic. The country is rough and wild up there; you have a long convalescence ahead of you."

"Nevertheless I shall go along," she repeated, and there was that in her eyes that convinced Mackington there was no use in arguing.

He shrugged his shoulders in pretended surrender.

"If you insist."

"I do."

He left, cursing under his breath. But on his way to the office of the Radium Trust, his eyes brightened. He had found a way.

He had no trouble in gaining admission to the inner office of Norris Benson. That worthy evinced no surprise at the announcement of his name; he had been expecting some such result of his machinations.

Benson stared speculatively at the sharp, cunning features of the man before him. Shrewd enough, he estimated, but too shrewd for his own good. A man like that could easily be overreached.

At the same time Mackington's thoughts were busy. His restless brain was figuring out a new way. Make the Radium Trust finance the expedition; then hoodwink them as well as the girl. Then the whole mine would be his; to what dizzying flights of power could not such fabulous wealth carry him?

He cleared his throat.

"Mr. Benson," he commenced.

"You are Ellery Mackington," Benson interrupted in a cold, expressionless voice. "You dealt in radium on a small scale at our sufferance. Then the plague came, and considerations of public interest compelled us to cut off your supplies. You delved back in history, found mention of one Herbert Wingrove and a lost radium mine. You enlisted the services of Dr. Blake, noted Mind Therapist, found a descendant of Wingrove's in the person of Florence James. Dr. Blake has operated for two days; today he discovered the exact location of the lost mine. Blake has already sold out to us; now you are trying to do the same thing. It is all of little moment to us, as we already know where the mine is, and can get there ahead of you all."

Mackington staggered under the shock. All his fine plans tumbled in ruins about him. How had the Radium Trust gotten wind of everything so quickly? Blake of course! Blake must have come here immediately, divulged the secret. At that his lip curled; he even smiled. Blake had given Benson the false location!

Benson saw the smile, and being a man of ready wit, felt that Mackington possessed certain information that even Blake had not laid hands on. For his last shot had been merely a shot in the dark. He knew Blake was supposed to be in touch with him. Blake had completed his operation that morning; Miss Selden had notified him of that. Therefore the information had been obtained; yet Mackington smiled. The man was cleverer than he had anticipated.

Mackington rose formally.

"In that case there is nothing for us to discuss. I bid you good day."

"Just a moment." Benson held up a restraining finger. "Blake has given us the location, but we know it is not correct." He was stabbing shrewdly now, his hard eyes watching Mackington's face like a hawk. "You have hoodwinked him; you know the truth."

The look of startled wonder on Mackington's face convinced him that he had guessed rightly. The man passed it over, laughed easily.

"You are quite right, Mr. Benson."

The General Manager continued on his careful, tortuous way.

"We had other sources of information. That is why we knew Blake's location to be false. I admit we haven't the exact dead center of the mine, but we know its general locale."

He had read up on old newspaper reports; found out where Wingrove had been discovered by the rescuing party. He mentioned the Endicott Range casually.

"We are correct within a radius of twenty-five miles. Our stratosphere planes will have no difficulty in locating the mine within hours."

A great fear enveloped Mackington. Perhaps it was true. Neither he nor Benson knew that the plateau was completely enclosed by high peaks, was but one of hundreds exactly similar in characteristics; that airplanes might search for weeks without discovering the right one.

"I am willing to discuss terms with you," he said warily. "I have the exact dead center."

Benson permitted no trace of inner exultation to appear on his fleshly features.

"Let us get down to business, then," he said dryly.

An hour later Mackington emerged, a smile on his lips and rage in his heart. A fifty-fifty division was the best he could obtain. The girl was out of the picture completely; he never troubled his head about her. Blake! He snapped his fingers. The man could do as he liked; the most he would get for his pains would be a wild-goose chase.

He had been sufficiently canny, too. In spite of Benson's skilful maneuverings, he stubbornly refused to disclose the ultimate secret.

"Prepare a fast stratosphere plane," he said flatly, "fully equipped for the Far North. I shall be on board, and direct the plane to its proper destination. I trust you as far as you trust me."

Benson granted his demands readily, too readily perhaps. It was arranged that the plane take off the next day at noon. Benson watched him go out, threw the switch on his televisor. The ground-manager of the Company's airport appeared on the screen.

"Jenks," he snapped. "Prepare a plane for the Far North, full equipment, to take off at noon. Mr. Mackington will present himself for passage. Use the Skybird." It was an old, but serviceable plane.

"And, Jenks, get ready the Meteor also, same equipment, full crew. I shall be on board. We take off a half hour before. Understand?"

The man answered very deferentially: "Yes, sir."

Benson snapped off the current, relaxed in his chair. A faint smile curved over his sensual lips. The Meteor was the fastest plane in the service!

Florence James had passed a terrible night. The image of Blake, with his sandy hair and long sensitive fingers, obsessed her restless tossings. His gray, quizzical eyes seemed unwontedly grave; were reproaching her for something. She rose in the morning with something like relief.

Blake was a traitor, she told herself over and over again, but it was cold comfort. Perhaps, perhaps there was an explanation. She thought of the letter, of Mackington. She conceived a violent distrust for the man; she berated herself for disclosing the secret to him. Something drove her; she must thrash the matter out at once, finally.

She dressed with feverish haste; her head was dizzy, the bandage in place, but she disregarded everything. She would see the two of them, have Mackington denounce Blake, hear his answer.

A nurse appeared, stared at her startled. But Florence brushed her aside with a strength ordinarily beyond her, fled through the corridors out into the open.

It was five miles to the General Laboratories Building, but she had no funds. She must walk the whole way. The sun was high overhead now; it must be near ten.

At twenty minutes to twelve, half fainting, inexpressibly weary, she appeared in the anteroom of Mackington's offices.

"I must see Mr. Mackington at once," she managed to gasp.

Miss Selden surveyed her coldly. "Sorry, Miss James, but he hasn't come in yet."

"Where is his home, then?"

"I am not permitted to disclose Mr. Mackington's private residence," the secretary said primly. She was fully aware that even now Mackington was on his way to the Radium Trust's flying field.

Florence swayed slightly, gathered her strength. She would go to see Blake alone then. The gyro-car landing beckoned alluringly, but she had no money. Therefore she entered the swift, downward-plunging elevator. The operator was a negro, with all the sunny, garrulous disposition of his race. He had seen Florence on her previous visits.

"Mornin', Miss," he greeted her with flashing grin. "Too bad you missed Mistah Mackington. He done left only ten minutes ago."

The girl straightened sharply. The car was rushing smoothly toward the ground.

"Mr. Mackington was here, in his office this morning?" she cried.

"Sho' was. De gyro-man at de landing say he left in a great hurry. Took de car to de flying field o' de Radium people. Yes, ma'am."

A clear white dazzling light illumined every hitherto dark corner in the girl's brain. Pain, opened skull, bandages, everything was forgotten. She saw the whole plot in all its devious ramifications.

"Stop the car!" she cried.

The startled negro obeyed, unthinking.

She gripped his arm with surprising strength.

"Sam, have you a half dollar?"

"Why, why, yessa; sho' have."

"Give it to me, Sam!" Her peremptory tones brooked no opposition. "And run me back to the gyro-landing as fast as you can. This is a matter of life and death, Sam."

"Yessa, Miss," the trembling darky replied.

Blake was pacing up and down the confines of his private office, worried. Mackington had an appointment to meet him there at eleven and had not shown up. Communication with Miss Selden obtained the putative information that he had not come in as yet. Then there was Florence James. Blake realized now that this thin, worn girl held a strange interest for him. Yet she had turned unaccountably cold at the last operation, treated him with a cruel brusqueness that seemed foreign to her nature. Then the location of the mine as related by the memory-recovery of Herbert Wingrove—there was something suspicious about that too.

All in all it was a very uncomfortable young man upon whom Florence burst in, her head a mass of bandages, her face aflame with urgency.

"Why, Miss James," he gasped with instant solicitude. "You are very ill; you should never have come."

She brushed aside all mention of her personal condition.

"I have news," she cried pantingly, "terrible news! Unless we do something, at once, the mine will be stolen."

He stared at her in amazement.

"What do you mean?"

She went over the story very rapidly, the color mantling to her cheeks at the readiness with which she had suspected Blake of complicity. But she told her tale bravely, omitting nothing.

"It was only when I heard just now that Mackington had left for the air field of the Radium Trust that I understood. He has set me against you, and himself sold out."

She grasped the young scientist's arm in forgetful eagerness. "We must do something. If the Radium Trust get the mine, it will be all over. Humanity will never benefit from its discovery."

Blake, the scientist, became at once the man of action. His jaw set grimly, his eyes blazed with unwonted fires.

He spoke rapidly. "Mackington no doubt is piloting a Radium Trust plane northward by now. There is only one thing left to do; follow, try and get there first. If not," he crossed to his desk, snapped open a hidden compartment, extracted a tiny dynol pistol which he slipped into his pocket. His unspoken words were eloquent.

"You have a plane?" Florence asked eagerly.

"Yes; my own." He snapped the televisor into action.

"Miss Kay," he said quickly, "get the plane garage; tell them to put every man they have on my plane. It's to be fueled for long range flying; plenty of food and rig out my altitude suit."

"Tell them to make it two suits," Florence interrupted.

Blake turned from the visor. "What for?"

The girl's chin jutted out determinedly. "I'm going along."

"You're crazy!" he exploded rudely.

"Crazy or not; I'm going! Don't waste precious moments," she cried angrily. "Remember, I haven't told you the correct location yet; and I won't unless I'm on the plane."

The two glared at each other for a moment, then Blake surrendered unconditionally.

"You little fool!" was all he said. But into the visor to his waiting secretary: "Make it two suits complete."

It was nearing midnight. The northern sky was a black void, pricked by lambent stars. Far below billowed and heaved an ocean of gray-white cloud masses, thick and ominous, completely obscuring all signs of the earth beneath.

Blake peered anxiously with red-rimmed eyes through the bottom crystal port of the enclosed cabin.

"Can't see a thing," he said to his companion, "but the induction compasses set us at approximately the right location. The Endicott Range must be below us."

He was tired and haggard from the long hard flight at maximum speed from New York. For almost nine hours he had kept a steady stratosphere course of five hundred miles per hour. At no time had he glimpsed the plane that carried Mackington and the emissaries of the Radium Trust.

The girl sat beside him, taut, wan, but upheld by inner fires.

"Why don't we go down, then?" she challenged.

"There's a blizzard raging below," he explained. "It will be almost certain death to try and land in this mountain country during a storm."

"But Mackington is ahead of us. Perhaps he's landed already. Don't you see?" she cried despairingly. "It was all my fault; this terrible mess. We must get down there before him."

Blake set his teeth. "Very well, I'll chance it. I'll fly you to Coldfoot, set you down. I won't have you risk your life. Then I'll come back, and if Mackington's already on the ground, well, one of us will not be in a condition to stake out his claim."

"I won't allow it," she retorted vehemently. "I am going with you."

They quarreled bitterly, ridiculously, over that, wasting precious moments, while the plane circled and circled in the frozen reaches of the stratosphere.

Florence had thrust her head angrily to one side at an especially impassioned plea of Blake's. It brought her line of vision direct with the southward opening port. Her sight thrust angrily out, swung aimlessly, and held suddenly taut. Forgotten her anger, her quarreling.

"Look, Harvey," she cried. She was pointing excitedly.

Blake leaned over from his controls, stared out.

A plane was diving downward from the fifteen mile level, not five miles away. It glimmered faintly in the pale starshine. Unhesitatingly it held its dive; it reached the massed earth clouds below, cleaved through them at terrific speed, was swallowed up in smothering billows.

"Mackington!" Blake shouted, and swung his plane around. He had beaten the traitor then in the race north, and had lost his advantage in foolish quarrelings. He cursed under his breath, and set his controls. He was going down after, girl on board or no.

Then Florence cried out again. Swooping down from the eighteen-mile level like a hurtling meteor, glowing faintly with the friction of its dizzying speed against the thin atmosphere, came a huge airplane. Down and down it plunged, on the tail of Mackington's plane, until the clouds swallowed it too.

"The Meteor!" Blake ejaculated. There was only one plane in all the world that could act like that; the famous racing plane of the Radium Trust.

"Good God!" Blake cried again. He could see the plot in all its ramifications now. Conspirator was double-crossing conspirator. Mackington was in the first plane, unwitting that he was followed. Evidently he had been cautious; refused to disclose the bearings. The second plane held armed men, ready to beat Mackington to the plateau in landing, or if necessary, snuff him out like an ancient candle and take possession in the Trust's sole name.

Blake flamed with battle lust, the urgings of bygone ancestors. He jerked his pistol out, laid it on the seat beside him, swung hard on his controls.

The plane turned with a sickening swoop, dived headlong.

"What do you intend doing?" Florence cried. She was alarmed now, ready to back out, woman-like, not for her own sake, but for fear of the danger to Blake. She realized now what he meant to her.

"Going for them," he answered briefly, and relapsed into silence.

The ominous cloud masses rushed upward at a dizzying rate, then the nose of the plane smacked wetly into the upper layer. The next instant they were in a world of unrelieved grayness, flying blindly through layers and layers of the ocean of frozen, dripping mist.

Blake watched his instruments. At the five thousand foot-level he threw out of his tail dive into a more gentle slant. They were through the upper cloud layers now, were enfolded in a howling Arctic blizzard. The gale screamed against them; the dull leaden air was thick with drumming sleet and great white flakes of snow.

Beneath stretched a terrain that was lunar in its jagged desolation. Somehow they had missed the encircling mountains, were slanting down toward a grim plateau. Not an inch of its surface was level or smooth; it was a tumbled, jagged waste literally bristling with huge needle-pointed rocks that glittered icy in the driving snow. It was madness to land on such hellish terrain even under the most favorable conditions; it was suicide in this whistling gale of driving sleet and snow.

Then Mackington's plane blundered into view, ghostly, ice-covered in the raging darkness. It dipped and came up again, swung around in hesitant circles.

Blake leveled off his flight, to watch what his antagonist would do. Then a thunderbolt dived out of the cloud roof straight at the unconscious plane. A streak of fire spurted out of the side of the Meteor, impinged dazzlingly against the cabin of Mackington's plane. There was a red flare, a shower of fused glowing metal, and the doomed plane hurtled downward to destruction.

Florence cried out in horror, and Blake swore. The Radium Trust was ruthless in achieving its ends. Not only Mackington, but even their own pilots, had been murdered in cold blood.

Blake zoomed hastily upward, into the blanketing storm. Fortunately the Meteor had not seen him. Then he snapped on the invisible penetration beam. He swung it around until it caught and held the Meteor in its invisible light. An image sprang into life on the screen inset above the controls; Blake could now follow his antagonist's movements without his being aware that he was watched.

The Meteor leveled off, dipped suddenly for the plateau, swung sharply upward again. The pilot was not intent upon committing suicide. They achieved-a five hundred foot level, circled slowly over the circumscribed plateau, obviously looking for a possible landing place. But there was none. The splintering needled rocks thrust wickedly up at every point. Even with the gyros to steady one's plane down, the lashing gale would inevitably dash it against jagged edges to destruction.

Three times the Meteor circled, then it seemed to give up the task. It soared to the thousand foot level, held poised against a backdrop of gray-white flakes. The plane seemed to be waiting for something.

Blake looked upward and understood. The storm was slackening in its force. Already there were rifts in the tumbled clouds overhead, stars swam into suddenly opened blue depths, swirled back into mist again. The sleet had ceased its drumming, the great soft flakes were thinning out. In half an hour the wind would have died, the sky become cloudless. Then the Meteor would discover their presence, machine-gun them out of existence. If there were anything to be done, it must be done now.

Blake turned, shook the girl's hand silently. She understood.

"I am ready," she said simply.

Blake dived until he was only a hundred feet above the upflung needles. Then he leveled, thrust out his gyrocopters. The great vanes whirled madly around, slackening his forward movement. Down they drifted; the sharp icy points seemed to lure them downward to destruction.

Florence closed her eyes shudderingly; Blake swung suddenly, hard. There was a sharp splintering crash, a jagged tooth ripped grindingly through the light steel wall of the cabin, and they were thrown violently.

Bruised, but otherwise unhurt, the two clambered to their feet, buried their heads in great fur parkas. The icy blasts were rushing into the cabin. Blake surveyed the damage hastily. The plane was pretty thoroughly wrecked; it would never fly again.

He grimaced; "We're in for it now. But first, let us stake out our claim."

He picked up the prepared notice of claim, boldly graven on a light steel plate affixed to a pointed steel rod, and with difficulty they opened the slide-port, clambered outside.

The fury of the gale was diminishing fast; tattered banners of the storm scudded high overhead. The poised Meteor was dimly visible.

Blake hammered the claim into the icy ground, took a swift glance upward.

"They'll be seeing us soon," he said grimly, "and then...

"What?" Florence asked bravely.

"They'll gun us out of existence the same as they did to Mackington, unless .... come in quickly, Florence."

He literally pushed the astonished girl into the wrecked cabin, where he worked feverishly at his radio controls. There was tense silence in the little cabin as he labored on; then:

"Thank God, it works."

He sent out his call on a directed beam: "Fairbanks.

Fairbanks." Monotonously, over and over again. Ghastly minutes of waiting, with the ever present terror of the great plane overhead. Then finally, the signaled answer.

The pair sighed simultaneously. They had been near the snapping point. Fairbanks could send swift planes to help; the Record office would file their radioed claim. Blake explained to an astonished operator on the guarded beam. One half the mine to be donated to the government; one quarter each to Florence James and Harvey Blake, discoverers.

"We are wrecked," he ended. "Send swift armed planes for rescue. Bandits are attacking us."

"Right," came back the welcome answer.

Blake stopped sending, looked quizzically at the girl he loved.

"I'll tell you something later, when we have time," he promised. "The Meteor is due to pay us a visit any moment now."

They hastened outside. The plane was dropping for them out of the sky. The bulk of their plane had been discovered.

"I expected it," Blake shouted above the dying tumult of the storm. The hunted pair dashed through the wind-piled snow, floundered among drifts and jutting pinnacles until Blake dragged the panting girl suddenly downward. They were in the shelter of a great overhang, somewhat protected from icy blasts and prying eyes.

Even as they crouched, tracers of fire streaked downward, followed by the staccato rat-a-tat of machine guns. The wrecked plane gave a convulsive heave.

Blake smiled grimly. "We got out just in time. The Patrol from Fairbanks will be here in half an hour. The Radium Trust is about due for a final reckoning."

"And the plague-stricken world will have unlimited radium," the girl added softly.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.