RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

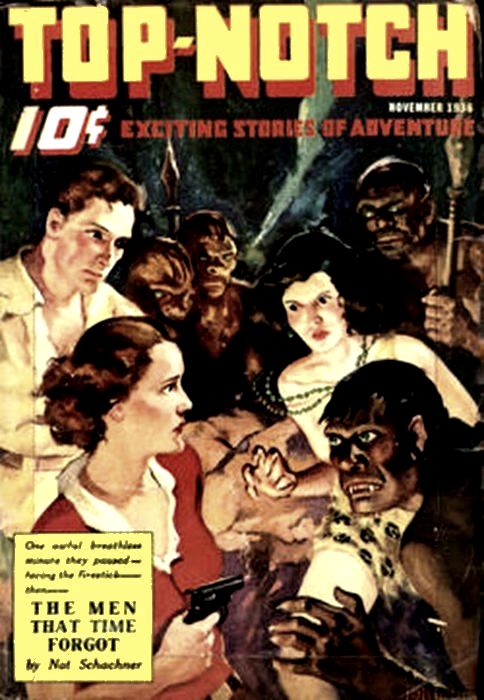

Top-Notch, Nov 1936, with "The Men That Time Forgot"

First Neanderthalers, who should have

been dead for fifty thousand years. Then—

IT was not much of an earthquake. The plastered walls of the mayor's single reception room and extraordinary office sprayed with tiny cracks, and a fine, white powder sifted gently to the baked, clay floor.

Outside, the ground shivered and shook itself a bit; the trees swayed suddenly, though the air was still and breathless, and the Hautes Pyrenées rumbled with complaints. Then it was all over.

In fact, Don Gordon would hardly have noticed the faint trembler had not his three-legged stool been tilted precariously backward at the time. At the particular moment he was dividing his attention between the singularly unreceptive mayor and the girl who sat in the farther corner, listening quietly and with an embarrassing hint of amusement to his perforce public sales talk to the mayor.

The Hautes Pyrenées was not exactly the best market in the world for American oil for the lamps of France and American gasoline for the tiny Citroens. But Don Gordon, ex-mining engineer, and down on his luck, had been glad enough to snag the agency when the former holder had disgustedly taken to drink.

Monsieur Perron, Mayor of Aureville, a little village nestled on the flanks of the soaring Pyrenées, had been his first call. The mayor, fat, his pork-fed ruddiness crisscrossed with shrewd, peasant wrinkles, was more than a public functionary. He owned the only garage for miles around, and dispensed kerosene and executive decrees with the same even-handed justice.

Don had a job on his hands, and he knew it. The competitors of his company had for years monopolized the poverty-stricken territory, and, he had a shrewd suspicion, were accustomed to grease well the perspiring palm of the mayor for the privilege. His discourse, moreover, on the advantages of American gas was still further embarrassed by the miraculous apparition of the girl.

She had come in quietly in the very middle of his peroration, and as quietly taken her seat on finding the mayor busy. Don fumbled, floundered and tried to jerk into high-gear salesmanship again.

It was difficult. His brain had divided into two compartments. What the devil was an obviously American girl, beautiful beyond any girl he, Don, had ever seen, doing in this God-forsaken neck of the woods? Evidently Perron knew her—he had bowed politely and murmured words of greeting on her entrance.

Don felt the tanned back of his neck grow red as he quoted figures, prices, flash points, octane ratings—all the salesman's usual patter—to a most uncomprehending Frenchman. In spite of himself, his eyes tailed to catch another glimpse of the beautiful vision. The surreptitious glance crossed hers—Don gulped and tilted his chair in utter confusion. Lord! she was good to look at, though the devil imps of amusement danced out of her too-innocent eyes and twisted her petaled lips into an upward quirk.

JUST then the earthquake struck.

The unstable stool tottered, crashed, and Don sprawled backward on the hard, clay floor. The pudgy mayor sprang up with an exclamation of alarm. The girl, however, had not moved; but Don's burning ears caught the swift surge of irrepressible laughter, then a choking sound as if a handkerchief had been stuffed into a mocking mouth. Ruefully he climbed to his feet, glanced angrily at the suddenly demure figure on the farther seat, stared in puzzled fashion at the still sifting plaster.

"Earthquake!" he grunted. "A baby one, and I fell for it. Look, Monsieur Perron"—he grinned ingratiatingly at the mayor—"it is nothing. A little shake of the ground, and it's all over. Moi, I've been in man-size ones in Chile, Japan, and even dear old California. This one was—pouf!" He dismissed it with a wave of his hand and some exceedingly barbarous French. "Now let's get back to business."

And all the while he was both wishing the girl to Jericho for her impudence and admiring her cool unconcern in what had been, after all, a rather frightening moment. "Now," he continued rapidly, "the American Gasoline Corporation will meet all competition by——"

He stopped short. "Great Scott, man!" he rapped out in good homespun English. "Pull yourself together. It's all over. Le tremblement de terre—c'est fini! Do you hear me? Fini!

But the mayor was beyond words. His heavy jowls sagged; his mouth gaped wide to show discolored stumps of teeth; his dew-lapped cheeks were a dirty gray.

"Why," declared Don disgustedly to the walls, to the girl, "he's scared out of his wits!"

There was no question of that. Twice Perron moved his thick lips, and no sounds issued. His little, cunning eyes were wide on the grimy window, staring in utter fear at something in the far distance. Don spun on his heels to follow that despairing glance and saw only the precipitous upthrust of the forested mountain.

"Well——" he began in some contempt for the driveling imbecility of the man.

The girl was on her feet, moving swiftly, gracefully, toward the seemingly stricken mayor. "Monsieur Perron," she cried in faultless French. "You are faint. Let me help you!"

But the mayor had finally found his voice. The dammed-up speech burst out torrentially. "It has come!" he cried wildly. "They are stirring, ces bêtes: they are coming out! We are lost—lost!"

He waved his short, fat arms to an anguished heaven, and darted out of his own house into the glare of the dusty road, crying "Lost! Perdu!" Outside, the clatter of feet became a rapid diminuendo, while the mayor's voice was a dying outcry in the wilderness.

Don ran to the door, stared out in utter bewilderment. The sleepy little village had awakened to screaming life at the mad flight of its mayor. As he ran, waving and shouting, hovel doors flung open, and a stream of humanity—old men, stout countrywomen, half-naked children—poured after him.

The men in the fields flung down hoes and spades, abandoned plow handles, and joined the pelting throng. Their shouts of terror receded on the lazy air until a bend in the road, as it disappeared atop a fairly level plateau, hid them from Don.

He swung back to the girl. "What's the matter with them all?" he demanded. "Have they gone mad? A little earthquake——"

SHE was even more beautiful than his quick side glances had disclosed. Her eyes were blue with a hint of gray to steady them; her molded features and throat, open to the hot French sun, were warmly tanned; her body was straight and lithe in riding breeches, shiny leather boots, and white sport shirt.

"A little earthquake, yes," she agreed. There was no longer any amusement in her voice; her eyes followed the terrified villagers with concern. "But the Hautes Pyrenées are not given to earthquakes, and they are afraid."

Still Don did not understand. "But it's over," he persisted.

She turned and faced him. "You are a newcomer here, Mr. —?" she asked irrelevantly.

He grinned. "Don Gordon is the name. My first trip to this neck of the woods. I'm trying to sell gasoline to the heathen," he added ruefully.

"I gathered as much," she answered, with a hint of cool satire. Then the concern on her face deepened. "That is why you do not understand these people. I do. I've lived with them for some months."

"Is it permitted to ask how an American remains in a hole like this for any length of time, Miss—uh—?" he asked gravely.

"Joan Parsons," she told him with simple dignity. "I've been sketching—the people, the country, the caves, listening to their stories, collecting their superstitions." She looked up at him suddenly, defiantly. "I intend writing a book."

Don grinned. He had her now. Her confounded cocksuredness was shaken. Evidently her family had objected to such nonsense from a girl who should be fluttering the hearts of all unattached males—and a good many attached ones as well—on the society firing line in New York, Palm Beach, Newport, Bar Harbor and points north, south and west.

But all he said was "Indeed?" with an upward inclination that brought an angry flush to her cheeks and rewarded him completely for the humiliation of her mocking laughter before.

"Indeed!" she echoed determinedly, and almost stamped her foot. But her eyes suddenly riveted on a thin trickle of smoke that lifted slowly into the motionless air above the plateau. A confused murmur of voices, swelling to a faint, concerted chant drifted down the slope to a seemingly deserted village.

"Oh!" It was more of a prayer than a gasp. Her eyes widened and an indefinable fear sprang into them. Then, with amazing litheness, she was at Don's side, her hand on the sleeve of his khaki shirt. The touch tingled through him, and surprise deepened at the sight of her deathly pallid face, the swiftness of her breathing. "They're going to do it, Mr. Gordon," she cried. "They're scared out of their wits. I would never have believed——"

"Do what?" he demanded, not moving a muscle. He did not wish to disturb that propinquity.

Her fingers dug into his arm. "It's the earthquake," she explained rapidly. "They think it's a sign, a portent. This is Cro-Magnon country—you know, those wonderful caverns in which the skeletons and the marvelous art of that primitive and long extinct people were found."

He nodded. Who in all the world had not heard of Cro-Magnon and Neanderthal men?

"The Aurevillers are cut off from the world," Joan Parsons rushed on hurriedly, her eyes fastened to that thin trickle of smoke up the mountainside. It seemed to be growing in volume. "Superstitions, folklore, fester here and grow rankly. Even before the caverns were opened, their great-grandfathers told of a race that lived in the bowels of the mountains, imprisoned because they had sinned against the ancient gods. Shepherds heard the rumble of their movements, the obscene growl of their anger, and took to their heels, deserting their flocks. The next day the sheep and cattle were gone, vanished, swallowed up by the mountain. There are even stories of children, young girls who wandered on Thunder Mountain—Mont Tonnere—and were never seen again. The finding of the Cro-Magnon remains only confirmed what they already knew. And all through their folklore ran a dark thread—that some day the restless, evil folk beneath would break through the prisoning rock."

Don laughed in some surprise. Almost, she had infected him with the shuddering feel of reality in those silly tales. Her face was pale and her lips parted, as though she, too. believed.

"So the earthquake meant a jail release for the Cro-Magnons?" He grinned. "Old stuff, Miss Parsons. Every race and every land has the story. The Titans heaving and turning over Mt. Vesuvius, the Trolls of the Scandinavians, the dark underworld gods of Africa—— Your friends of Aureville are just plagiarists. They'll pray a bit up there, exorcise the evil spirits with some holy water, and come back relieved of their fears. You're taking it too hard—Joan."

THE smoke had become a thick, black column. The faint chant swelled to a strange, barbaric chant. Somehow the sound chilled Don—this was no chant of the church, no stately, rolling periods—Don had never heard such weird tonalities before, such jarring ululations.

The girl passed over the use of her first name. She fell away from him at the sudden shift in the chanting, her face pale as death. She sucked breath sharply. Then her eyes blazed, her hands clenched. She turned swiftly to the man. "Don—Mr. Gordon, we've got to stop it!" she panted.

"Stop what?" he wanted to know. Yet somehow the faint adumbration of what was taking place on that hidden plateau had come to him, and chilled him to the bone.

Joan was already at the door. She turned a moment, silhouetted against the lazy brightness of the June sun. Yet even as she spoke, a sinister shadow fled over the peaceful countryside, drenched it in a blood-red light.

"The people of Aureville are still pagan at heart," she said steadily. "The old beliefs, the old forms, crop out in times of stress and fear. Up there"—and her slim, straight arm pointed to the lance of smoke, ruddy in the eerie light of a setting sun—"a druid altar still exists. And Mayor Perron, public fonctionnaire, communicant in good standing of the church, pretends to trace his ancestry to the druid priests. Now do you understand?" But the last words whipped back over her shoulder. She was running swiftly up the curving road, up the steep ascent of Thunder Mountain.

For the moment Don fumbled with his thoughts. He dared not yield to the stealthy horror that invaded his being. Druids, pagan altars, Cro-Magnon, grisly superstitions, whirled in kaleidoscopic array. It was incredible—this was the twentieth century and France one of the most civilized, enlightened countries in the world. Good Lord, the girl was mad! But every precious instant took Joan Parsons farther away, nearer to the source of that spine-tingling ululation, closer to the sinister pillar of smoke.

A great fear suddenly enveloped him—a fear for this girl he had just met, who had laughed at his sprawling discomfiture. "Come back!" he shouted. But she did not hear, or hearing, refused to heed. She was running with the swift, ground-eating stride of an athlete.

With a smothered oath, Don raced after. As he pounded up the dusty path after the fleeing figure, his brown, sinewy hand went instinctively to the flat bulge in his hip pocket. It was a habit born of the far countries to tote a gun, even in peaceful, gun-discouraging France.

He gained on her steadily, but not rapidly. She was fleet of foot. He called on her to turn back, to wait, without result. Then he grimly bent to the task, straining every nerve, every muscle, to catch up with her before that last turn where the road debouched upon the hidden plateau. The smoke was a bloody pillar of fire by now, as though green wood had finally burst into flame, and the chant had become a weaving, toneless clamor.

"Joan!" he cried desperately.

The girl poised an instant on the brim, her head jerking back as if in terror, then she lunged forward and disappeared from view. Even as she did, a scream ripped through the darkening air. The sun was a blood-red ball, impaled on the highest peak of the mountain. Darkness came rapidly in these mountain uplands. Another scream, then a fierce confusion of cries. The ground swayed slightly, shook itself down with a guttural, rending growl. A second earthquake!

That had been a woman's shriek; a sharp, shrill cry of fear. Don's blood pounded tumultuously in his veins as he fairly flew up the slope. It had not been Joan's voice, but—— The flat automatic glinted in his hand. Then he was around the bend and had burst on the level plateau.

His head snapped back; his last leap froze almost in mid-air. Before him was a scene such as would have sent the chill blood beating back to his heart had he stumbled on it suddenly among the head-hunters of New Guinea, or in the jungles of the voodoo priests in the Congo. But in la belle France——

THE sun was down, and the prickling stars were out. The grim loom of Thunder Mountain thrust its craggy lift in black mass behind the tiny plateau. Directly in the center, a half dozen monoliths of granite made a ring. Outside, the grass grew lush and wavy; within, the dun earth was bare. Heaped fagots made an inner circle. Flames leaped upward to thrust back the darkness. and the dense smoke of green, sizzling wood made fiery shadows.

Around the monoliths, at a discreet distance from the burning embers, shapes leaped and gesticulated and swung around in a never-ending dance. The murky light blazed on their faces, contorted with fear, filled with a shouting ecstasy of dread. Around and around they weaved and bobbed, into the night and back again: The villagers of Aureville, the dull, stolid folk of glebe and hearth and domesticity, rapt out of themselves by the rooted instincts of ancient superstition.

All this Don took in with one swift look: then his horrified eyes clung to the dim figure—half shielded, half outlined by the circling flame and smoke. The figure of a girl, struggling against invisible bonds that held her rooted to a gigantic block of stone within the very center of the charmed ring. Joan? No; for even in that instant of shocked hesitation, a girl in breeches and white sport shirt darted out of the night and into the maze of dancing shadows, beating at them with tiny fists, crying out against them by name.

A fat. gross man caught her as she Would have leaped through the shell of flame, flung her back with a torrent of mingled French and strange, harsh words. It was Monsieur Perron, no longer Mayor of Aureville, no longer a fat, shrewd peasant, but transformed, his face terrible with sweaty grime and soot—a druid priest. "You little fool!" he cried. "You'll spoil it all. Go back, before I——"

Joan was on her feet again, lancing like a swift dragon fly through the screaming melee. Her hair was loose and wind-blown, her face that of an angry Valkyrie. Perron whipped his left hand from behind his back. Something glittered in the bloody shadows. Joan cried out. swerved. Even as site did. the girl within the blinding flames screamed again.

Don acted. The automatic leaped level, dropped back again. It was not time yet to shoot. Instead, he dived forward. head lowered, shoulder hunched for a spine-jarring tackle. He crashed into the gross body of the mayor with terrific force; there was a startled grunt of pain; the steel blade described a wide arc and fell fussing into the circlet of flame, and Perron jerked over and backward into the seething mass of the villagers.

WITH barely a stagger, Don crashed onward through the blazing fagots, over the dun. bare earth, and hurtled directly for the bound figure of the girl. Surprisingly, a voice greeted him, cool and steady, although somewhat hurried. "Quick, Don. Help me loosen the poor thing."

He shook the smoke and cinders out of his eyes. Joan was there ahead of him, her slim white fingers tugging frantically at the looped cords that held the struggling peasant girl to the ominous granite.

"Monsieur, monsieur!" she was moaning. "Take me away. I am afraid. I do not want to be the bride." She was flaxen-haired and pretty, but her cheeks were wet with weeping and her eyes were terrified.

"We'll get you out of here in a jiffy," Don assured her, as he leaped to Joan's side. The ropes fell away rapidly. But inwardly he was not so sure. The jar of his tackle had ripped the automatic out of his hands, and he was defenseless against the mob of screaming, superstition-maddened votaries of an ancient faith.

Even as they caught the fainting girl between them, his eyes widened on the shallow hollow atop the huge, carved granite, the smooth, worn runnel that led from it directly over the edge. Echoes of the elder ritual tightened the grim lines around his mouth. A swift picture of a leaping, howling horde of celebrants—even as these now raising shrill cries outside—etched in his mind; a tall, fanatical, white-bearded priest silhouetted against the stars, his sear hand lifted high. A long, sharp blade in swift descent; a smothered, gurgling shriek from the hapless victim on the stone; a gush of dark blood flowing through the runnel, dripping gruesomely into a basin beneath. Vision of forgotten sacrifice, seemingly come to life again in horrible similitude.

"What will we do now?" Joan asked quietly, as she patted the hysterical girl.

"Do?" Don echoed grimly, eyes narrowed on the dim figures beyond the flames. "Make a run for it. Come on."

His booted feet kicked vigorously at the fagots, sent brands and sparks scattering into the night. Through the narrow lane he trod, fists doubled, shoulders hunched forward, lips snarling. Behind him, Joan followed closely, supporting the trembling girl. For himself, Don thought, a quick smashing rush might get him through; but with the two girls——

The mayor was on his feet again, his villagers huddled around him. The mad ecstasy was gone from their faces; instead, the soot of the expiring fire painted strange terror and haunted fury.

Perron lurched forward, bleeding, wrathy. "Bêtes d'Americains!" he screamed, shaking his fist. "You have spoiled everything. The bride is no longer a bride. The underground folk will be angry; they will come for us. You have brought woe to Aureville."

Don watched him warily. He did not seem armed. The others were like frightened sheep, peering behind them uneasily into the dark. He raised his voice so all could hear.

"Beast, eh? You and you and you are beasts." He stabbed out with accusing finger at the peasants. "You call yourself Christian folk, yet you grovel in hideous superstitions; you would have murdered this poor girl in your cowardice. Scatter!" he cried out in a tremendous voice. "Begone! If you go to your homes quietly, perhaps I shall not tell the gendarmerie what I have seen."

Tensely he waited for the inevitable rush. Joan stood proudly at his side. The rescued girl was weeping quietly.

A hubbub of confused voices broke from the throng. They were individuals once more; men, women, children even; blank comprehension on stolid faces.

Perron exclaimed in astonishment. "Murdered! You are fou, Americain! It is but a ceremony to appease the evil spirits who grow restless down below. My father's father once made them cease their grumbling by similar means." He laughed most convincingly. "Marie!" he demanded of the cowering victim, "tell him it was but a ceremony—but a—ah—ritual. You would not have been harmed."

Marie burst into a storm of blubbering. "In truth, monsieur, so I was told. But then—the so wild flames, the dark, the noise, then the shaking of the ground—and—and I was certain I saw——"

She broke off with a strangled shriek. "There they are again—they have come!"

With a strength born of mad fear she broke loose from Joan's protecting arm, hurled herself through the shrinking mob like a ship through parting waves, and ran, shrieking and crying, into the enveloping darkness. A babble of voices followed her clattering footsteps; alarm danced with red shadows on every face.

The mayor spun around like a wounded bull; then his eyes widened on something on the blank loom of the hill. Rage gave way to terror; he flung his arm upward as if to ward off some dreadful sight; then, with a howl, he too catapulted into the night, on the trail of the girl, slamming down the mountainside as if chased by a legion of devils.

Some one cried out: "The ground has opened. The black folk are coming!"

THAT started the panic. A frenzy possessed them all. The wails of children mingled with the deeper shouts of the men, the shrill sopranos, of women. They knocked each other over, trampled in wild haste over the bodies of their fellows. The cupping hills resounded with their cries.

Then—there was nothing but the dying embers, the dim-seen monoliths, the black night, and the stabbing stars overhead. The villagers were but a faint echo of far-off feet and muted sounds.

It had all happened in an instant. Don and Joan were alone within the druid circle, astounded at the kaleidoscopic turn of events. Involuntarily Joan had shrunk against him at the first outcry—she was trembling. His hand went out in the semidark, touched her shoulder.

"It's O.K. Nothing to worry about. They just scared themselves with their own fears."

"I—I don't know," she whispered. "For the moment I thought I saw something out there—moving."

"Nonsense," he assured her heartily. "You've lived with these people too long, and became infected with their superstitions. It's ridiculous—an underground world belching forth immured beings. But I'm glad it's over. I can tell you now—I was a bit scared for a while."

She clung to him frankly. "We—we misunderstood. I remember now—that tale of Perron's grandfather—how he soothed the unquiet spirits with this ceremony of the bride. It was all pure pantomime."

"Of course," Don agreed heartily. Why worry her with his own thoughts: The knife in the mayor's hand, the expression on his face!

"We had better be going," he observed lightly. "It's dark, and the path is treacherous. We'll have a time of it." He linked his arm in hers—and she did not draw away.

The heaped wood was char and dull-red embers now. The monoliths, the grim central altar, were blurred, significant shapes. Thunder Mountain was a back-drop of Stygian hue. The Hautes Pyrenées were a frozen storm of black waves. The plateau was deserted.

Deserted? Even as they stumbled into the lush grass, Don caught a glimpse—or thought he did—of something dim and huge. He looked again—and it was gone. He smiled wryly to himself. He was getting the jitters, too. Soon he'd be seeing Cro-Magnons—— But unconsciously he hastened his step. His heart kept thudding in spite of gritting will power. The girl's voice drifted anxiously out of the gloom. "What's the matter? Did you see anything?"

"Who, me? Nothing at all," he lied. "But we'd better hurry. It's getting chill. These mountain nights——"

It was quite hot, in fact. The June air lay sultry and breathless. But Joan made no comment, and kept even pace. "Good girl!" Don thought admiringly. It was slow going through the tall grass, and they had to feel their way by instinct toward the dirt path up which they had raced earlier in the evening. Their feet went swish swish, and Don's heart kept time. He was jumpy; he groaned. Those damned old wives' tales——

JOAN stopped short, pressed against him. "Did you hear that?" she whispered.

He cocked his ears. "Nary a sound," he assured her. "It's the confounded grass." But he, too, had heard it. A faint rustling to one side, as of some one stealthily stalking them. Ordinarily he would have put it down to some night-prowling animal, but the beasts of the Pyrenées do not slink through the darkness in groups.

This one did! There had been other noises, as of grass parting, to the other side, in the rear. Once he could have sworn he had heard a tiny mutter of words—the night was otherwise so still. But that, of course, was his own jumpiness. He laughed shortly.

They resumed their slow progress, though his heels itched desperately to hurl him forward in a sudden dash for the road and the low-lying village. Damn it! There they were again, those sounds. Almost he felt hot breath over his shoulder. Only by sheer will power did he refrain from whirling and lunging out. He would only scare Joan by such silly stunts.

The girl stopped again, gripped his arm tight. Her face lifted to his in the faint starlight, a brave cup of loveliness. "There's no use fooling ourselves any longer, Don," she remarked quietly. "There's something out there, following, stalking us. We—we're surrounded."

He looked down at her. "Yes," he agreed evenly, "as you say—there's no sense in pretending. I've known it ever since we quit the druid ruins. And they're not animals, either. Only wolves travel in gangs, and they don't act the way—uh—these do."

"Don!" she cried out sharply, quickly. "They're coming—they're—oh!" Her voice crescendoed into a choked, gurgling sound.

Don spun around, fists balled into tight knots. He lashed out with every ounce of strength in his corded muscles, felt them sink into flesh. Then he was overwhelmed under a fury of powerful bodies. Hands pinned his; a club crashed his skull into shattering oblivion. As from a great distance he heard Joan's trailing shriek—then the stars fell upon him with blinding suddenness——

A BLAST of cold air on damp forehead, the painful, dragging progress of bruising limbs against rocks and scraping soil, brought a measure of awareness to Don's pain-swept senses. He opened leaden eyes. The stars were still overhead, but the surrounding darkness was peopled with hurrying, formless shapes. He struggled, and the jerk on his pinioned arms almost wrenched them out of their sockets.

Hairy bodies pressed closer. Animal smell, musty and faintly foul, stifled his nostrils. The torture of twisted muscles slapped him back to full consciousness. Somehow he forced his bumping legs upright, pistoned them along to the swift, noiseless movements of his captors. They were a compact pack, surging forward with purposeful strides.

Don twisted his head vainly to see who or what they were, but the gaunt shadow of the mountain prevented more than half hints and sketchy outlines. But they were enough to sicken him with sudden horror.

The things that had taken him prisoner were neither men nor four-footed beasts. They loped up the rocks with easy, sure-footed stride, hunched forward and swinging with the motion of great apes. Don was no weakling himself, but the two who gripped him dragged him up the steep formations as unconcernedly as if he were a mere husk of feathery lightness. Thick, coarse fur covered their bodies, wire-rasped Don's arms.

He stopped struggling, kept even pace with his captors. They made no sound, either of speech or padding feet. Only the scrambling shoes of Don disturbed the sullen night. He forced his mind to coherent action. He was not dreaming: the splitting of his skull, the aching bruises on arms and legs were too keen for that. But his thoughts edged fearfully away from the true explanation.

It must be some gigantic jest—he clung desperately to that. The villagers, for reasons unknown, had hurried into secreted ape costumes, were engaged in a queer masquerade. He called out Perron's name, gasped out halting French, demanded that they cease this silly business. But the vague, hulking shapes did not answer, and claw-like fingers tightened already painful grips. Then a hairy paw slapped ham stingingly across the face.

The slap woke him to quick fury. With a sudden wrench one arm was free. It swung up and around, to dart forward, crashing. Halfway toward its goal, the tight fist poised, sagged, and dropped aimlessly to his side.

Wan silver had just flooded Thunder Mountain. The moon had risen. Brave as Don ordinarily was, he could not repress a chilling gasp of fear. What he had dreaded most, what he had fought off with childish, fantastic explanations, was in fact only too true. The moon peeped down on creatures that had not peopled the earth for fifty thousand years or more. Creatures that were neither apes nor men. Shaggy beings, whose hair hung like wool over huge, powerful limbs—brown, simian faces in which no spark of human understanding shone—low, sloping foreheads—pendant arms that almost swept the ground.

Then he saw their eyes, or rather, that they had no eyes. The sockets were blank and fleshy, devoid of organs of vision. They were blind! Unnumbered generations, spawned in the eternal blackness of the bowels of the earth, had finally sloughed off the useless appendages, and developed doubtless in their stead the tactile sensibilities of the bat.

The shock of discovery deadened him to all pain. Perron had been right; the superstitious nonsense, fart. The earthquake had broken through the prisoning crust, had liberated these ancient being, who, unimaginable centuries before. had been driven underground and sealed in by some cataclysm.

Cro-Magnons? Impossible! For they had been well along the road of evolution, while these hairy, silent beasts were hardly removed from the ape. Neanderthalers! Men of the Old Stone Age; monstrosities which the deep bowels of the earth had held intact!

A LOW moan awakened him from his dazed condition. He was being hauled unmercifully up the sheer fate of a cliff. The Neanderthalers climbed like monkeys. It was cold up here. But the faint human cry twisted him around, almost caused him to break loose and fall headlong down the rocky slide.

"Joan!" he cried hoarsely. Good Lord! He had almost forgotten her in the wild confusion of dulled senses and swift-marching events. He saw her now, dimly outlined in the pallid reflection of the moon. A slender, curved body slung limp, unmoving over the sloping shoulder of one of the brutes. She stirred at his cry, turned her head weakly.

"Don!" she whispered. "What—who—are these——" Then she was silent again. She had fainted.

A quick, short bark from the leading brute brought the pack to a halt. A fissure yawned before them; an irregular crack whose edges were freshly splintered. An earthquake fissure, black, ominous, extending inward to unknown depths. A cold wind gushed forth, stirred tire dampness of Don's matted hair.

Another bark, of different intonation. The lead Neanderthaler was gone, swallowed into the unknown. Don's captors jerked forward, dragging him with them. He struggled, heaving with all the strength of his muscular body, but not for an instant did the ape-men cease their forward progress.

With a grin of despair he relaxed. Joan had just disappeared into the crevice, still unstirring on a bestial shoulder. Now he must follow, even if by some sudden twist he could have broken away. But he could not restrain the sharp, keen suction of his breath as they jumped into the pit. Ages of falling. then the jar of unseen landing wrenched his spine.

Down, ever down, they hurried in silence. following the twisting, irregular crevice. The blackness was insupportable; strain as he would Don could not see the tiniest glimmer of light. But the pack seemed to have no trouble in finding its way. Eyes here were at a disadvantage. Sure-footedly they padded over cold, damp rock, avoiding projecting walls and jagged edges with uncanny certainty. And all the while the cold, fresh wind blew upward steadily.

Suddenly, at a grunt of command, the party halted. Water tugged at Don's ankles, swift and inky. The roar of an underground river echoed as from far-off walls. There was a guttural bark, and Don felt himself shoved violently forward. He thrust out his arms wildly to right himself, and then the rapid waters closed over his head.

He came up gasping, spluttering, the cold of the underground stream an icy constriction around his heart. A faint strangling cry reached him. He turned desperately toward the sound. An invisible hand struck at him, forced him under. By the time he had come up again, all sounds had ceased.

Fear clutched him, almost paralyzed his limbs. What had happened to Joan? He cried out her name, and the mocking stone picked up the name and tossed it back at him. Had she drowned; had she——

The swimming Neanderthalers splashed loudly, and rough, hairy arms dragged him erect. His floundering feet touched slippery bottom—then they were on solid rock again. They had forded the river.

But his savage captors gave him no rest. He was pushed and heaved and prodded along; down, always down. They were tireless and accustomed to the depths. He staggered along, hopeless, bloody, no longer caring. He was certain Joan had died back there in the bottomless stream. He had heard her smothered cry, and no further sound. He had met the girl only short hours before, yet already the world would be as lightless without her as this underground dungeon.

The passageway seemed to widen; they were no longer in the earthquake fissure. The air was still surprisingly fresh, but the wind had died to a sluggish breeze. It was drier, too. The ape-men were moving more slowly now; in a more compact group.

Their silent feet were even more silent now—they seemed to be wary; and clutching hands fell away from him to grip around huge clubs. He stumbled into the swinging bludgeons more than once; and as he did, a faint chatter as of fear came from the wielder, a sudden swerve away from him. At each slight cry, a low growl from up ahead brought immediate silence. The Neanderthalers were obviously afraid—but of what?

DON, alert once more, tried to figure it out. Once they all flattened themselves quickly against invisible rode Something huge and unwieldy lumbered by, snuffling and softly trumpeting. From the sound of its passage, it must have been immense. A musty odor pervaded the darkness.

In Africa, Don had smelled similar effluvia when a herd of elephants had passed to the windward. He hardly dared to breathe as the huge animal swung by. What mammoth from an earlier era had been shut up in this strange underworld with the Paleolithic men?

He could well understand the fright of his captors. Their clubs would have been but sorry weapons against the crushing bulk of the great ancestor of all the elephants. They started out again after the animal could no longer be heard, but their tread was even slower than before. They were afraid of something else, something even more frightening than a hairy mammoth, something near whose haunts they were approaching perilously close.

The small hairs suddenly prickled all over Don's body. Ahead, the impenetrable darkness seemed to have lightened, to have become shot through with faint streaks of dim silver.

Moonlight? Here in the depths of the earth? He lifted his head quickly, filled with swift hope. They had been traveling downward at an unknown angle. Perhaps they were coming to another fissure that the freakish earthquake had opened, leading directly to the outer and lower slope of the mountain. In which case——

He tightened his muscles grimly. The fear seemed to have deepened on the blind, shaggy brutes. He could hear little whimpers, little snuffling sounds as of withheld terror. Their empty sockets had somehow sensed the far-off prickle of illumination and it represented a source of danger. They swerved to one side, seemingly down a second passageway, plunging into a blackness more profound than before.

Don edged stealthily away. No one held him now; the inclosing Neanderthalers were moving fast, snuffling, moaning, anxious to get away as fast as possible from the perils of that pale break in the darkness. They seemed to have forgotten their captive. It was now or never.

He blinked, stared, was unable to suppress a stifled gasp of surprise. From the direction of the thinned dimness, long sweeps of yellow light flared out, swept over suddenly, revealed rocks of a narrow passageway. Fantastic shadows danced and raced over jagged stone walls; then blinding radiance flooded the depths. From around a bend came sounds—the noise of swift movement and muted voices.

Joyous release flooded Don. A band of men—torches—searching the erupted underground world. His absence—that of Joan—had been discovered. A rescue party had climbed Thunder Mountain, found the second fissure.

The Neanderthalers cowered from the leaping glare of the still-invisible torches. A wild panic seized them. The quick, frightened bark of the leader could not stop them. Like a pack of great apes they rushed, chattering and whining, into the deeper crevice. Don was bowled over by the sudden rush, sent tumbling and rolling, into the depths.

He clawed blindly to his feet, hurled himself against the swift tide. It was in vain. The blind beasts were a compact horde, smashing their way downward, harried by an unknown, irresistible dread.

Don went backward, clawing, fighting, smashing himself again and again against a rush that would not be denied. Already the lower passageway was twisting downward, away from all hope of rescue. The torch party had not as yet seen the Paleolithic men.

Smothered, exhausted, desperate, Don lifted his voice in a great cry. "Help! Help! This way!" The sound boomed and reverberated through the rocky chambers like repetitious thunder through an invisible array of passageways. There was an answering shout. New strength flooded Don's battered body. He had been heard.

A WILD howl of animal execration burst from the pushing, tumbling ape-men. All semblance of order was lost in the last mad rush to plunge down into the Stygian depths. Don pressed himself flat against the damp stone wall, heart hammering with the joy of anticipated rescue. There had been a strange note to that answering shout to his cry for help, but its true meaning had not penetrated his brain.

Another sound, however, low though it was. pierced his buzzing ears like a knife slash. For an instant he was pressed against the wall in frozen incredulity. while hulking brutes stumbled blindly past. Then he jerked into action. The cry had been feeble, but unmistakable. Joan was still alive, being carried into the farther depths from which there would be no return.

He catapulted forward into the Hind darkness, straight for the spot where he had heard that last faint moan. He smashed headlong into a rushing, hairy form. There was a squeal of fear, a flailing arm caught him off balance, sent him staggering in a new direction. Stunned, blinded, careening off rushing bodies, he staggered helplessly, crying: "Joan, Joan!"

Miraculously he heard her in all the roaring tumult of flight. "Don! Help! He's carrying me off."

He hurled himself toward the sound in one last desperate lunge. An invisible hulk whirled at his coming. A snarl of anger met his battle shout. Shaggy ape-man and khaki-clad modern slammed headlong into each other. Don's fist sank deep into an unseen stomach; a great paw grazed over his head.

It was a weird battle in the bowels of the earth. Don had the advantage of superior skill; the Neanderthaler of accustomed darkness and immense strength. Another blow, and Don went staggering. But he returned to the onslaught, grim, wary. Joan was struggling futilely on her captor's shoulder, clutching his hairy arms, seeking to break the force of his swings.

The rest of the Neanderthalers were gone, scuttled to remote depths. The torches raced closer. The pad of feet, the wild shouts were growing in volume. Then they bad turned the corner of the angling tunnel. Light streamed in upon the scene, illuminated the struggling figures. With a howl of terror, the ape-man dropped his burden, raced with ungainly, yet swift pace into descending darkness.

Don, bleeding, battered, hurried to the sprawled figure of the girl. "Joan!" he panted anxiously. "Are you all right?'

She rose lithely to her feet. "Quite!" she answered bravely. "Just shaken up a bit." The smoky glare etched her face into a cameo of sudden, wide-eyed fear. She shrank against Don's tall form. Her slim hand fled to her throat. "What—are—they?" she whispered huskily.

DON whirled at the terror in her voice. Involuntarily he thrust forward to shield the girl from the menace that raced upon them. A new despair prickled his scalp, tightening the bands about his heart. These were men who were advancing rapidly toward them, holding piny torches high above them to lighten the murky tunnel; but they were men such as Don had never seen before. A guttural shout whipped up as they perceived the two trapped humans at bay in the passageway, and they surged forward on the run.

Joan dung to Don's protecting arm. "What are they?" she repeated.

"We're either dreaming together," he groaned, "or just gone crazy. First Neanderthalers who should have been dead for fifty thousand years, and now the——"

There were a dozen of them—tall, magnificently proportioned and muscled; foreheads high and lofty, noses broad and flaring, cheek bones accentuated and tawny. Yellow tiger pelts slung at a sharp angle from shoulder to brawny loins. The leaders carried torches; the others held spears ominously level—pointed, flaked flints, bound to long sticks by rawhide thongs.

Resistance was hopeless. Yet Don got in one solid blow before his arms were pinioned behind him, and fastened swiftly and skillfully with tight leather strips.

Joan was a prisoner at his side in the twinkling of an eye. A half dozen ran unhesitatingly ahead, down the rough, winding tunnel, in pursuit of the vanished ape-men, their torches streaming sparks and back-flung smoke in rhythm with their rapid lope. But a sharp whistle from the tall, leonine being who had pounced on Don with crushing embrace brought them as swiftly back.

A great chattering broke from the group at the strange sight of the two dwellers of the upper world; hands plucked at their garments curiously, as if to feel the texture.

Joan held herself erect, proud, though she flinched every time a great brown hand passed over her.

Don struggled furiously to get to her, cried hoarsely; "Let her alone, you devils!"

Futile efforts, futile words. For obviously these strange creatures of another race, another time, knew no English. A hulking figure cuffed him. Glowering looks turned on him. But the leader whistled sharply again; torches lifted high, spears couched into position, and the party whirled in disciplined order to retrace their steps up the steeply narrow tunnel. Rude hands urged the prisoners along.

"Out of the frying pan into the fire!" Don said bitterly.

"But what are they?" the girl panted for the third time.

This time Don answered. He glanced sidewise at the giant whose sinewy arm forced him at a rapid pace up the slippery rock. "Cro-Magnons!" he said succinctly. "Beings of a much higher degree of civilization than the Neanderthal ape-men. We've stumbled into a world that time had sealed and then forgotten all about."

They were in the main tunnel now. It had leveled out and the torches showed rapidly expanding walls. Already the ceiling was dim with flickering shadows.

"What—what do you think they intend doing with us?" Joan tried to keep the quaver out of her voice, and knew she had not succeeded.

"Keep us as curiosities for a while, and then let us go," Don lied with false cheerfulness. He had no inner illusions. The Cro-Magnons had left remarkable artistic evidences, but that did not mean that essentially they were not savages—an earlier stage of evolution.

THE walls flung back suddenly; the rock ceiling soared out of sight, and a joyful whoop broke from the hurrying tribe. Pale moonlight filtered through from somewhere high above, to disclose a huge, interminable cavern.

Far off in the distance could be dimly discerned walls and radiating passageways. The ground was level, hard-packed clay. Overhead, like the dome of an incredibly lofty cathedral, sprang the rocky roof of this vast underground domain. A dozen gaps pierced the vaulted ceiling, through which shafts of silvered illumination diffused into the interior and shed a wan glow.

The torches flickered and went out The Cro-Magnons hastened their steps across the rock-bound cavern, forcing their prisoners to keep even pace. In the distance a fire leaped redly, sent bloody shadows ebbing into the farther reaches. Giant shapes silhouetted blackly around the crackling flames, squatting on their haunches. They leaped up at the shout of the returning raiders, streamed irregularly toward them with answering whoops of exultation.

"Welcoming the returning heroes," Don commented dryly.

The cries gave way to grunts of astonishment as they came closer and saw what manner of captives their brothers had made. They crowded forward in their eagerness, gesticulating and chattering, anxious for a nearer view of the strange beings that had been brought back, in place of the Neanderthalers they had been led to expect.

But an angry command from the leonine leader thrust them away into a respective circle. The feeble moonlight from the overhead vents silvered their mobile faces, gave them an air of intellectual inquiry that perhaps the more brutal sun of the outer world would not have justified.

The procession started again, and Don and Joan were jerked roughly into motion. In the distance, dim against the shadowed walls, Don glimpsed figures; motionless, lofty, as though rooted to the ground.

Here and there, as flame or moonlight pricked sections of rock into prominence, he caught other tantalizing half views of bright-colored surfaces—startling representations in ochers, purples and greens, of bisons, saber-toothed tigers, hairy mammoths and reindeer, drawn with vigorous fidelity and precision, and an attempt at linear perspective that astounded the observer.

A wild boar loomed hugely, with eight legs in bent attitudes of motion, to give a kinetic impression of speed.

But they were prodded past at too rapid a pace by their impatient guards for Don to obtain more than the most sketchy of glimpses. At length the fire was reached. Heaped embers, glowing strangely like coal and fossil peat, blazed and crackled in a shallow depression in the clay bottom.

Savory odors smote Don's nostrils, awakened inner pangs. He had not realized how hungry he was. Great joints of meat roasted in the bedded embers, tended by shambling, shaggy figures whose movements were limited by leather thongs around their prehensile feet in such a way that only short, mincing steps were possible.

One turned his face blindly toward the approaching horde, jerked back with a certain cowering fear to his task of turning the joint.

Joan gasped with mingled pity and repulsion. The sightless sockets, the squat, ugly features, the brute blankness, betrayed the Neanderthaler, blood brother to those who had ventured through the earthquake crevice into the outer world, and who had been forced underground, and had fled, chattering with terror at the apparition of the Cro-Magnons.

"Slaves!" Don told her grimly, "captives of raiding parties, even as ourselves. We've a swell future to look forward to."

"If that were only all," Joan whispered, staring.

THREE figures had continued to sit near the fire, squatting on their haunches, thrusting claw-like hands out over the flames, as if to cup their grateful warmth. They had disdained to join the rabble who had streamed to greet the conquering heroes; they disdained even now so much as to turn their heads to view the source of all the commotion.

But the tawny leader forced the two human beings, captives of his spear, forward, and prostrated his great length on the hard earth before them. Only then did they deign to look at them, at the creatures he presented to them with rapid guttural speech. Yet they did not lower their arms or move their scrawny bodies from the enveloping heat of the fire.

They were incredibly old—these imperious three. Their faces were shriveled, their jaws toothless, and a coarse gray fuzz covered their shrunken limbs and grotesque pot bellies. The eyes of two were bleared and rheumy, but those of the middle figure, whose face was a painted mask, bedaubed with ocher and green day, were incredibly alive and fiercely brilliant.

"The old one of the tribe," Don decided. "Probably the high priest." Instinctively he felt that their fate depended solely on the will of this hieratic being of an elder era.

Their eyes clashed with a locking of indomitable wills. Don met his gaze steadily, betraying no fear on his impassive countenance. The unblinking stare of the old one left his lineaments, as though he had been drained dry of the desired information, and traveled to the straight, slim figure of the girl.

Her clothes were torn and soggy with water and mud, but her head was proud and high. Except for a faint flush on her cheeks, she might have been but a disinterested spectator of perfectly normal, upper-earthly proceedings.

For the first time the high priest lost his iron control. His flaccid lips parted to betray raw, toothless gums; his thin, dry-stick arms swung away from the life-giving fire with a strange gesture; a low, cracked grunt escaped him.

There seemed wonder, startled recognition in his probing, knife-like glance. Slowly he tottered to his feet, his comrades rising with him and wagging parchment heads. Like three old vultures they sagged forward, thrusting themselves almost into Joan's face, peering as if they would never have enough.

Joan met the repulsive scrutiny with all the courage she could muster, trying hard not to flinch, to betray her loathing.

Don lurched forward, straining wrists against confining leather. If those evil old creatures intended——

A backhanded slap of a powerful hand sent him reeling back. The leader of the raiders—the tawny one—had risen from his prostrate position before the trio, was growling malignant gibberish at him. Don shook his head, spat out the sweetish blood that trickled in his mouth, grinned tightly.

"O.K.!" he said slowly. "I'll remember that slap when the time comes."

A dark scowl spread over the Cro-Magnon's face as if he had understood; the spear lifted significantly in his hand.

But the ancient men did not need this byplay. All their attention was centered with a strange intensity on Joan. Harsh consonants, unrelieved by the liquid softness of vowels, quavered between them in obvious consultation. Suddenly they seemed to have determined on their course.

To Don's utter astonishment, to the complete bewilderment of Joan, the high priest sank on his haunches, bent forward, and groveled before the taut, proudly erect figure of the girl. His colleagues followed feeble suit. Three outstretched creatures, foreheads knocking dully against hard clay, arms extended forward and downward. "Ng n' gm!" they quavered in unison.

At the sound of the harsh syllables the horde of watching men of another time fell prostrate, banging heads hard on clay, pointing like hunting dogs directly toward Joan. A mighty shout swelled upward to the distant rocky vault: "Ng n' gm!"

JOAN shrank from them in fright. The armor with which she had encased herself against the terrors of the underworld collapsed at this groveling manifestation, at the strange phrase that pulsed about her. Imploringly she turned to Don. "What does it mean?" she asked huskily.

He stared at the prostrate multitude. "Only one thing," he decided. "The old one has come to the conclusion that you are a goddess or divine person of sorts. It's a swell break for you. Pull yourself together, Joan, and act the part. If they think you're afraid, they'll turn on you."

"I—I see." Her head went on; her body stiffened; her look became imperious, as if in fact she were divine. It was a marvelous bit of acting, which caused even Don, who had suggested it, to blink and stare admiringly.

But one Cro-Magnon had not fallen prostrate before the goddess. He was the head of the party that had taken them prisoner. He stood haughtily erect, massive, trunk-like arms folded insolently across the yellow tiger skin that covered his chest, lips compressed, eyes scornful. Don saw his defiant posture, spoke in quick, even tones to the pseudo-goddess.

"Do something, anything. Joan; but make him kneel and worship. If you don't, he'll break the spell of your divinity for the others."

The girl nodded, stiffened again. If there was the least tremor of fear in her bearing, Don could not detect it. Her eyes flashed; her slender, white arm went out imperiously toward the recalcitrant Cro-Magnon.

"Down!" she commanded. "Down like the others!" Her voice crackled like the swift lash of a whip. Don strained forward, waiting breathlessly for the result.

There was none. The Cro-Magnon did not move. If anything, his attitude was even more insolent than before. The thin edge of dread entered Don's soul. If he got away with it, all was lost.

Already the prostrate figures, seeing that no lightning had struck the audacious one, raised their heads, stirred uneasily. The old one was halfway to his knees. The air in the huge, twilight chamber was deathly tense. Don tugged fiercely at his bonds, trying to free his hands against the inevitable. Even the blind Neanderthal slaves paused in their ceaseless ministrations to the blistering fire, cocked hideous heads. The only calm, quietly undisturbed person in the great cavern was Joan. Her slim hand dropped from its threatening position, slid smoothly into the deep side pocket of her breeches.

Don groaned. She had admitted defeat, made the one gesture that brought it unmistakably to the savage intelligences of the Cro-Magnons.

The stirring yielded to a scraping, scrambling sound. They were heaving to their feet. The slack lips of the old one were opening, to issue furious commands. He had lost face before those he had swayed for uncounted years; and the goddess who had proved not a goddess must suffer for his mistake.

Don poised on the balls of his feet, determined to catapult himself like a battering-ram toward the tawny insolent who had done this to Joan.

The girl's hand came out of her pocket, and in it something glittered that brought a stifled gasp to Don's incredulous tips. It pointed at the still-standing Cro-Magnon. Her finger tightened.

Flame belched forth; there was a puff of smoke and a sharp report that sent the echoes flying in endless reverberations over far-distant walls. The bullet whizzed by the tawny figure's head, so close that the shaggy mane of his hair ruffled and lifted with the wind of its passage.

Consternation brought lightning change to his scornful features. With a startled howl of anguish he cast himself down and forward, hanging his forehead against the clay, moaning wild, abased phrases of pleading that the angry goddess stay her stabbing flame and spitting thunder against him. the meanest of her votaries.

With one concerted cry, the others of the tribe, half to their feet, fell flat on their faces again in ludicrous haste. Only the old one, triumphant even in his fear, sang toothless praise before he carefully lowered his aged form to the ground.

"Good girl!" Don shouted. "It's a pity you missed him. And—where did you get the gun?"

With cool deliberation she returned the sinking weapon to her pocket. "I always carry one—for protection." She answered the last question first. "And I missed him deliberately. I—I couldn't bring myself to kill, even to save my own life."

Joyfully Don walked over to her. No one interfered; no one dared lift his head from the earth.

"Swell!" he complimented. "You have them eating out of your hand with that shot. It's powerful magic to them. Get these thongs loose from my hands before they come to, and give me the gun. I won't be afraid to use it," he assured her grimly.

Her fingers were deft and skillful. "There!" she declared, as the leather fell away. "Thank Heaven you're free again. As for the gun"—she smiled strangely up at him—"that was the last bullet in the chamber. I was afraid even that wouldn't fire because of the wetting we got in the underground river."

Don stared, whistled softly. "You are a brave girl," he murmured. Something in his tone brought a quick flush to her cheeks, caused her to avert her eyes.

Rut the frozen tableau was moving again. The groveling Cro-Magnons were scrambling to their feet, as if they had made due and sufficient obeisance to the goddess who had spoken to them with a tongue of angry flame. Only the tawny rebel still lay on his face, not daring to rise.

"What do I do now?" Joan asked uneasily.

"I don't know," Don confessed. "You'll have to watch your step, and follow the leads of the old one as fast as he furnishes them. Even a divinity is hedged in with numberless taboos that must not be broken."

"And you?" she queried with a little catch in her voice.

"Don't worry about me," he retorted confidently. "I'll take care of myself—— Hello!" he broke off. "What's that?"

THERE was a quick patter of naked feet from beyond the fire. Out of the outer darkness, into the red circle of flame, a young girl burst—long, jet-black locks streaming with the rapid wind of her motion.

She skidded to a slapping halt directly before the three old priests, black eyes snapping, face contorted with fury. Her thin, straight lips opened with a shrill flood of guttural, rapid invective poured out upon the high priest himself. She stamped her bare feet in an ecstasy of anger, shook a clenched fist directly under his bony nose. Her supple, yet unhealthily pallid body—as if too long denied the influence of a benign sun—was innocent of all clothing; except for a slender girdle of skin about her loins. She could not have been over twenty-one. In her blazing anger, she had not noticed the couple who stood rooted to the ground at the sight of her.

"She—she's white!" Joan gasped.

"And French," Don supplemented in startled accents. "How in blazes did she get here?"

Joan drew a shuddering breath. Her face was suddenly drained of blood. "I—I'm afraid I know," she said very low. "Those stories of young girls wandering on the mountain and vanishing were not mere folklore. They must have seized her when she was a little child. She speaks their language. But that was long before the earthquake. Where do——"

Don stared up at the dying moonlight. The tremendous vault was now only a shadowy adumbration. The moon must be setting. "Probably fell through one of those openings. Landed on some ledge by a miracle, and was found by the Cro-Magnons."

"Don"—the girl spoke rapidly—"we've got to save her, get her back to her people."

He did not answer. His eyes narrowed on the lurid picture. The red circle of fire, fed by the constant ministrations of the Neanderthal slaves. The blind brutes themselves, hairy and shambling. The Cro-Magnons, crowded forward like spectators at a fight—magnificently built, yet primeval savages nevertheless.

The three old ones swayed, half aghast at the sudden eruption of the girl. The girl herself, shaking with passion, seminude, blazed at them with an incomprehensible torrent of gutturals.

Just then the high priest seemed to take new courage. He wheeled, pointed a skinny finger at Joan, and made what was an unmistakable gesture of dismissal to the newcomer. She pivoted like a cat to follow his pointing finger, and stopped short in mid-flow. Her eyes widened in astonishment at the sight of the two strangers. For the moment she fell back aghast. Joan made an impulsive movement toward her. "Poor thing," Joan cried sympathetically. "We must——"

Don caught her arm with surreptitious gesture, halted her just in time. It would not do for the Cro-Magnons to observe the restraint. "Hold everything!" he whispered softly. "One false step and it might mean your life. That girl was the goddess whom you displaced!"

But already the deposed one had read Joan's gesture with feminine intuition. The momentary fear yielded swiftly to furious scorn, a harsh cackle of derision. Her fingers went up, snapped contemptuously—the single memory of a normal childhood on the sunny slopes of the Hautes Pyrenées.

The Cro-Magnons stirred uneasily. Even the high priest paled. A magical sound, obviously; one that was impossible for their thick, clumsy fingers to imitate.

She smiled cruelly, tossed her black hair. Confidence returned. She advanced toward Joan, hands clawed like a cat. The Cro-Magnons waited tensely. Which would prove the goddess—the old or the new?

DON fell quietly away from Joan's side. She must fight this out on her own. His intervention would be disastrous. But as he slid away, he whispered urgently: "You've got to prove your superiority. Act up."

Joan's glance swung miserably from the advancing girl to Don. "I—I can't," she wailed. "It might mean her death. Poor thing!"

"It will surely mean your death if you don't," Don ripped out. "Hurry!"

She extended her arm unwillingly. "Arrêtes-toi!" she commanded.

But the other did not stop. The French phrase had long been forgotten, and the tremor in Joan's voice inspired confidence in her ability to remove this attempted usurper from her path. Snarling, she increased her pace.

Don clenched his fists in agony. He did not dare go to Joan's rescue, yet she would not have a chance in physical combat with the savage girl. Then inspiration came to him.

"Quick!" he called out "The gun!"

"It has no bullets," Joan answered despairingly. For the first time she realized that the French child had long tees submerged in the abysmal brute. There was no mercy in that snarling face. Death Leered openly at her.

"No matter!" Don shouted. "For Heaven's sake, use it!"

A dozen yards separated her from the catapulting, screaming god. Hoarse gutturals of anticipation spewed from the Cro-Magnons. The tawny one was grinning evilly, barking swift syllables to the deposed goddess. His flint-tipped spear was in his hand, poised threateningly. It was in line with Don.

Don tensed for a swift spring—first to Joan's rescue, then a quick demivolt, a flying tackle at the tawny one before the spear could find its mark. And then would——

He grinned wryly. He had seen the muted glance of understanding between the former goddess and the tawny one. No wonder the latter had attempted to dispute the new.

Joan pulled herself together in the face of sudden death. The glittering weapon snapped from her pocket in a blur of speed. She leveled it at the plunging figure with dramatic gesture, mouthed meaningless gibberish with tremendous emphasis. A low mutter of fear rose from the underground race. They had heard that shiny firing speak before, and had seen it spew forth flame and smoke.

The girl hesitated in her wild forward surge. The gun meant nothing to her; bat the suddenly imperious figure of the goddess who had displaced her, the quick, backward shrinking of her former worshipers, puzzled her. Her savage senses could not quite untangle the situation. But only for a second. Rage at the newcomer, the upstart, blinded her to all considerations. A momentary stagger, and she leaped forward.

Don moved fast, so fast he barely stopped himself in tune at the great, terrified cry of the lawny one.

"R'th!"

The girl slid almost under the nose of the steely weapon before she could halt. Her dusky features turned to the Cro-Magnon; surprise, submissiveness, passion all commingled.

"Og!" she demanded.

Og—the tawny one—had dropped his spear with a clatter. His eyes bulged from their sockets in fear. His great, hairy arm shook convulsively as it pointed to the gun in Joan's hand. A storm of trembling gutturals stuttered from his lips.

He, Og, had witnessed the potency of that strange magic. Let R'th beware! It would spit angry flames at her; he himself had almost died. The new one was a powerful goddess, and the shiny magic was her power. Go now, R'th! Later, he, Og, would talk with her!

R'th's eyes widened on the death-dealing magic, shrank back. All the Cro-Magnons had fallen flat on their faces, worshiping, groveling before Joan. The high priest, with his ancient consorts, bobbed and weaved like jittering pendulums. They had been vindicated. The old one grunted derogatory phrases at R'th. Had she, in all her career, done anything to disclose her magic as had this new divine person? Go quickly, discarded one, before she feel the weight of her wrath.

R'th spun on her naked heel, eyes smoldering with repressed madness. She glowered at the adoring circle, spat venomous words, and ran back of the fire, howling like a she-wolf in travail. The farther darkness swallowed her up then even the howling ceased

The color fled from Joan's face Slit swayed. Now that the crisis was over all her strength had ebbed. Don was at her side, aching to take her in his arms. But he dared not He must do nothing to break the illusion of Joan's divinity. On that—and on that done, their lives depended. "Steady!" he warned. "You performed swell, but you can't let down."

She smiled bravely. "I know," she acknowledged. "But that poor girl——"

"That poor girt—and our friend Og—spell trouble." he told her grimly. He cast a swift glance around. Og, the tawny one, had disappeared. His jaw hardened. "We've got to get out—somehow. Meanwhile, keep a stiff upper lip."

ROUGH hands seized him violently from behind. The onslaught was so sudden, so silent, that he did not have a chance. Before he could heave his shoulders, before even Joan could cry out, he was flat on his back, his hands bound with stout leather strips, his feet immovable.

The old one bobbed in front of him, keen eyes bright and flaring like those of a cat in the semidarkness. The fire was a slow, dull bed of embers now; the rest of the great underground world had vanished into unrelieved blackness.

Joan darted forward impulsively, crying out his name. But a wall of Cro-Magnons, vague hulks over which the dying fire still trembled, ranged between their mortal prisoner and their goddess She beat small fists against their shaggy hulks in vain. She even drew her empty gun, leveled it. They did not harm her, yet neither did they give way. Evidently even the magic of the goddess must be powerless against the taboo of the prisoner. Don rolled over, raised his voice. "I'm all right. Joan. They're only locking me tip for the night."

It was a guess, but seemingly a correct one. For, as Joan withdrew, they gestured humbly for her to lie down near the fire. Grunts of satisfaction arose when she understood, and obeyed. The Cro-Magnons made a wide, respectful circle, squatted in the dark, and were soon silent in sleep. Near Don, however, a half dozen guards nodded over spear points, jerking erect as heads slumped down on the sharp flints.

For a while Don fought sleep. He worked surreptitiously at his bonds, and only succeeded in rasping the skin off his hands. Then he lay, staring into the unfathomable dark, seeing only the faint glow of scattered coals.

It was a strange situation. Two moderns captive in the hands of a prehistoric race—a race that had dwelt for ten-, of thousands of years and habituated itself to life in the sunless bowels of the earth.

Perhaps somewhere in the spray of caverns, loam existed, in which fungi, grain of sorts, grew to feed man and beast. The sealed-in mammoths, reindeer and bison, furnished meat. And there were the Neanderthalers, to be hunted in their remoter lairs, made into slaves.

What would be the end? Would they ever escape, or would Joan become eventually like that girl, R'th. The name had once, no doubt, been Ruth, lisped in frightened, childish accents. Trouble ahead—R'th—Og—blind Neanderthalers—high priest——

He was awakened by much stirring and grunting and heaving around him He opened his eyes, instinctively tried to jump up. He fell back with a groan. His feet were numb, his bound hands prickled with retarded circulation. He could not see a thing—he was swathed in a shroud of blackness deeper than any starless night on outer earth. There was no fire. Yet the Cro-Magnons seemed to have no difficulties. They yawned, grunted, and moved about noisily, and sure-footed.

Somewhere, close by, stone clashed on stone. A spark leaped out—and another. A dull smolder, then a burst of flame. A torch had been lighted. It passed rapidly from hand to hand, illuminating in its passage the sleep-sodden faces of the Cro-Magnons. Torch after torch burst into flame, and the darkness fled back a little. An island of murky light in an ocean of chaos.

Don felt himself being roughly lifted to his feet, the thongs that bound his legs removed. In the smoky glare of the torches cold meat and a hollow stone of water were offered him. He ate greedily, drank with gusto. New strength flowed back into his limbs.

He looked around, tried to find Joan. There was no sign of her. He called out her name. There was no answer; nothing but the guttural rasp of Cro-Magnons. He called louder, listened anxiously. Still no answer. Sudden fear assailed him for the girl. What had they done with her? But the ruddy, illuminated faces about him gave him no clue. He tried with a sudden jerk to break away. A spear jabbed viciously out of the gloom, sent a sear of pain through his side. He was surrounded with grim Cro-Magnons, enringed with spears. Violent shoves hurled him forward; impatient tugs dragged him along. They were taking him somewhere. But where, and for what purpose?

He stumbled on, aching in every limb, feeling the blood ooze from his wound. He no longer cared what happened to him. But Joan——

It was chill and damp in the immense cave, but the chill that froze his heart was of a different order. He tried to remember what he had read about the archaeologists' guesses as to the religion and rites of the Cro-Magnons. Gods? Goddesses? What happened to them? But all that would come to him was the memory of certain sculptured figurines, found in the upper caves, obviously female, and obviously involving the cult of fertility. His thoughts were not pleasant. Suppose Joan——

THEY were moving rapidly. The darkness was still impenetrable, fleeing only a short distance to either side from the flare of the torches. He did not know where he was going. Certainly he'd never be able to find his way to the fissures which the earthquake had opened to the outer world. Yet only the thought of Joan obsessed him. Or, too, and the girl, R'th. Both were still missing. Nor had he seen anywhere the high priest or his associate old ones.

After what seemed hours of weary stumbling, the cavalcade suddenly stopped. A hush fell on the huddled group. One by one they extinguished their torches. A guttural whisper ran up and down the ranks. Breaths sucked in. Even the spears that had nudged Don along with their cruel points dropped softly to the stony floor. Yet the shaggy, powerful bodies hemmed him in, making escape impossible, even if his hands were free.

He stared in vain. The darkness was profound. Like a dead black wall; the more so from the quenched dazzlement of the torches. What were they waiting for?

What was that? Almost directly ahead, a vague splotch glimmered in the profound, a thing without shape or movement. The glimmer deepened, strengthened into a pale phosphorescence. Then, as he stared in astonishment, the void took form and glowed brighter and brighter, until—and Don's sudden sharp gasp matched the murmurings of awe from the crouching Paleolithic men—a statue burst into unmistakable view.

Of marble it seemed, a noble woman, graciously proportioned, whose smooth nudity glowed and pulsed with warm, phosphorescent life. The classic head was thrown back in sheer ecstasy, and the molded arms were upthrust in invocation to the invisible heavens. The features were unbelievably of a womanhood well advanced in evolution; the wide-spaced forehead, the calm, serene eyes, the classically chiseled nose, the tender lips. A masterpiece of art, that Phidias himself or Michael Angelo would have been proud to claim.

For the moment Don forgot everything else but the glory of that sculptured marble, the poised, proud lift of that ecstatic figure. A figure against a back-drop of sheer nothingness—phosphorescent, alive!

Where had it come from? By what strange means had it been placed in the bowels of the earth? Certainly it was not of Cro-Magnon or Neanderthal fashioning.

Don felt rather than saw the tense attitudes, the bird-like quivering of the Cro-Magnons. They were worshiping, adoring. Of course! Even he, a member of a higher race, of an advanced civilization and culture, was stirred to his depths by the loveliness of tine statue, the eeriness of the surroundings.

But there was something about it that was vaguely disquieting, something hauntingly familiar. Something that shouldn't exist——

He shifted quietly in the dark. Even when he brushed against a hairy body, the Cro-Magnon did not stir. Nothing existed but that phosphorescent marble. Perhaps then Don could bare drifted stealthily away, and made good his escape. But he was not thinking of escape. The vague unease was growing steadily stronger. Only by shifting his angle of vision could he determine definitely——

He stood stock-still. A short cry rasped from his throat, shattering the awful stillness. The Cro-Magnons started up, buzzed angrily around him. Spear heads lifted, ringed him round again. But Don felt neither Hint pricks nor blows. A superstitious dread pervaded him. Momentarily he was one with the Paleolithic beings who surrounded him—stirred by the same terrors that stirred them, feeling the scalp prickle on his head, and flesh grow ridged and hard on his body.

It was unbelievable, horrifying in its implications; but his dawning suspicion had been only too readily verified. Now, as he faced the statue full, it burst upon him with a blinding light.

The lovely marble figure, sculptured by an unknown master at least two thousand years before, was no other than Joan Parsons!

There was no question about the resemblance. Joan's lovely slimness and lithe limbs—that forehead, those eyes, the nose, the lips. It was more than a mere resemblance—it was Joan herself! As though the ancient sculpture had taken a plaster mold from the modern girl's living body, and infused it with poured marble!

It was incredible, impossible! Not in a million, million years could such exact duplication have taken place by chance. Yet how else explain it? For one shattering moment a horrible thought seared across his brain—and vanished—leaving him Limp and shivering. The statue was Joan, somehow immersed in calcifying salts and immured in eternal stone. Rut, no; it was obviously chiseled marble. Yet——

A GREAT shout clamored up from the Cro-Magnons; sudden, electrifying, startling. Spears clashed; stone hammers crashed an atone. Don whirled, stumbled, righted himself.

A dazzling shaft of light had pierced the sable darkness like a flaming sword. From high overhead it came, from the vaulted arch of the cave itself. Don blinked smarting eyes at the swift illumination, opened them again. The statue had faded into a dim glow beside the strong white blaze, it slanted down the dim air, impinged upon the cavern floor, upon——

Don's cry ripped high above the guttural clamor of the Cro-Magnons. His throat was a dry constriction, his veins congealed ice. A moment's stupefied horror, then he charged, head down, wrists chafed and raw from straining at his bonds. "Joan!" he screamed. "Joan!"

It was light now in the cavern. The wide ray of sunshine, darting through a pot hole from the outer world, diffused a haze of misty light over a considerable distance. Moment by moment, other orifices in the upper rock brought scattered illumination from the rising sun. It was day.