RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

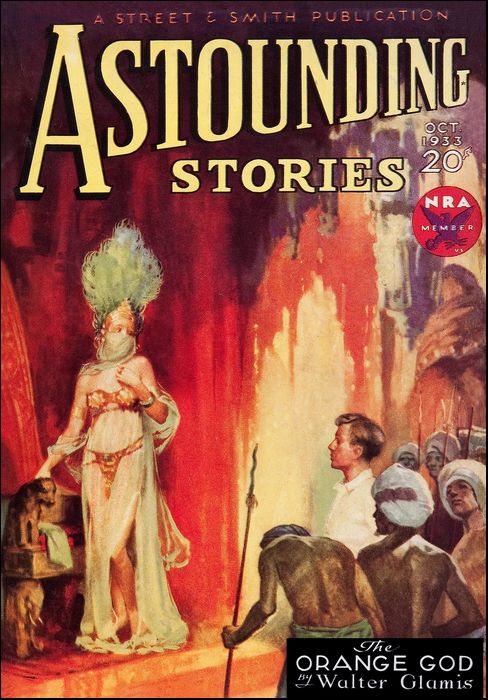

Astounding Stories, Oct 1933, with "The Orange God"

It was the figure in the center that drew his gaze.

THE Bagdad-Calcutta mail was less than an hour out of Peshawar when the storm came. It was inexplicable—this storm. One moment ten thousand square miles of Indian plain and shaggy, snow-humped Himalayas seethed under a copper sun; the next, a wall of darkness swept out of the east, blotting out sky and mountain and plain as though they had ceased to exist. The fast-flying ship seemed suspended in a lightless void; the spinning earth beneath was gone; the sun above erased. Even the motor's familiar roar was oddly hushed in the sudden quiet.

"Damn!" said Saunders, the pilot, and groped for the light switch. The instrument panel glowed into feeble illumination, as if it, too, were oppressed by the blackness. Two heads bent over simultaneously to stare at the gauges. Saunders, leathery and dour from too much solo flying, and Ward Bayley, the American passenger from Peshawar for the last leg of the trip.

"Queer, isn't it?" muttered Saunders, startled, but not yet afraid, as he jerked the plane upward in an attempt to clear the strange pall. The instruments seemed to be working all right.

But Bayley's face showed white in the dim, reflected glow.

"Not scared, are you?" asked Saunders, his voice edged with contempt. "We'll get out of it soon." He opened the throttle another notch.

"A little," the American admitted calmly. "I've heard rumors about this from the hill tribes on the Tibetan border; that's why I was in a hurry to reach Calcutta to consult with——"

The instrument board blanked out suddenly; the motor sputtered once and died. The plane did not seem to be moving; all around was black nothingness. Saunders swore and wrestled with the controls.

"Look!" came Bayley's voice.

Far in the distance, a million miles away, it seemed, a tiny pinprick of light stabbed the world. It danced up and down, like a pith ball on a jet of water; then it, too, went out. A moment later it reappeared, steady and fixed; and as the fascinated watchers strained aching eyeballs, it elongated swiftly like a traveling rocket, straight up, and up, and up—a shaft of orange light that flamed clear-etched in the void, cut off beneath where the earth might be if the earth still existed, and extending upward to an infinitude where alien universes once had form and substance.

Saunders was afraid now, horribly so. He could not see his companion. The plane, the world, had come to an end in everything but that endless column of light.

"God!" It was his only word. Bayley did not speak at all. He crouched grimly in the cockpit, waiting.

Then came the storm.

The ship was caught in a blast of overwhelming sound. It whirled and whirled around in dizzying circles, while the two men held on with a grip of death. The keel shuddered once, and the rudderless plane leaped forward, faster and faster, until the tremendous acceleration pressed unbearably upon the limbs and hearts of the crouching pair. The invisible wind screamed and howled; the plane fled faster and ever faster, straight for the motionless shaft of fire.

How long it lasted, Bayley was never to know. It might have been minutes, or hours, or days, even. The plane took a final great leap, and was immersed in the orange glare. A split second of dazzling comprehension, a strange look of exaltation on Saunders's prosaic face, and darkness again as the ship hurtled clear. Bayley tried to hold on to what he had seen, what he had understood, but the plane was dropping now, and the memory fled into the pit of his stomach. There was a quick, ripping sound, a crash, and Bayley's head collided violently with something hard.

He awoke—it might have been seconds later, it might have been hours—with a sharp pain in his left shoulder, and a dull throb to his head. His eyes opened unsteadily, and saw—nothing. The orange pillar of flame was gone, the storm was over; only blackness and thick silence brooding over chaos. He moved. There was jagged hardness beneath, rock and splintered fragments of the plane. Twinges of fire streaked through his shoulder.

"Saunders!" he called weakly.

The sound of his voice drummed in his ears. There was no answer. The pilot was dead, or still unconscious. Bayley closed his eyes wearily against the unbearable dark. Something rustled, something dry and crackly. He forced his lids open again. Nothing! The sound ceased.

A shriek tore jaggedly through his failing consciousness, cleared his head of the groping pain like a douche of cold water. He thrust himself upright with a superhuman effort. The shriek was repeated. A woman's voice in the last extremity of terror! The clogging veil split open in a long gash, revealing a mountainside in weird half light. A girl crouched against a huge rock, her hand outthrust in an agony of horror, every limb instinct with unutterable fear. Her face could not be seen.

She shrieked a third time, and Bayley staggered to his feet, ripping his side unheeded against a jutting strut. He took a wavering step forward, when the walls of the darkness rushed soundlessly together, blotting out mountainside and girl and the accents of horror as if they had never been. The world was void of light and movement once again.

Bayley stood rooted.

"Saunders!" he shouted, and the sound mocked him. Was he, Bayley, dead, too, and all this but a dream of the beyond? Terror flooded him; strange terror he had never known in a long, adventurous life. Something made a stealthy pad-pad close by. He started to run, stumbling, crashing, in the impenetrable blackness. The pad-pad behind him quickened and grew in intensity. He was being pursued. He ran on blindly. They were gaining on him. He tried a last desperate spurt, and his foot slipped. He was falling. He thrust his arms out wildly, caught at a projection, swung precariously a moment, and lost his hold. Down again into chaos, until something came up with a thud, and the blackness without gushed into his brain.

When Bayley recovered consciousness it was night—normal, natural night, with stars and a dim sliver of moon overhead. A great thirst tormented him; his left shoulder was stiff and caked, and his head ached oddly. He tried to move, and almost went toppling into the abyss. One leg was dangling clear. Clawing awkwardly, he managed to pull himself back to safety. For a moment he lay panting; then he looked cautiously.

He was perched amid the rotted roots of a tree that had long since whirled into the tremendous depths below. It was a sheer precipice; the feeble starlight disclosed no bottom. Bayley shuddered as he thought of what might have happened had he not caught in the matted roots. He looked upward.

The lip of the cliff slanted backward from where he lay, not more than fifteen feet above. He had not fallen far. The slope could be negotiated. Slowly, painfully, he pulled himself up over the roots, testing each hold with infinite caution, pausing when a stone dislodged beneath his unwary feet to hear the sound of its thud at the bottom of the gorge. But no smallest noise came up through the still night. At last he stood at the top, disheveled, clothes slashed and torn, blood caked stiff.

What had happened? Where was he? Where was Saunders? It had been noon when they left Peshawar; now, by the stars, it seemed close to midnight. What had caused that strange, weird storm, that supernatural column of light? He had been pursued, too. Did those invisible padding feet belong to animals or men? The girl, disclosed a moment by a rift in the black curtain, and swallowed up forever—what did it all mean? The questions beat furiously through his mind and evoked no answers.

Force of habit dictated his next moves. All his life he had wandered in the out-places of the world, amid strange tribes and savage customs, and caution was second nature to him. He dropped quickly behind a huge boulder that teetered on the edge, so that no hostile eye could spy him in the shimmer of the stars. Now he was able to take stock of his surroundings.

He was on the outthrust of a huge mountain, perched seemingly at the edge of the world. The ground descended slightly away from the cliff, then rose again in a long slope of a thousand feet, and ended abruptly in a towering granite wall, whose top was lost in the thin darkness. All around, to north, east, and south, tumbled mountain range on range, higher, more breathtaking than the Himalayas themselves. To the west, however, there was nothing; a pool of blackness that disclosed neither land nor sea.

Bayley shivered. There was only one range of mountains in the entire world that compared with this—the fabulous, sinister, almost unknown Gangi Mountains of northern Tibet. That meant that they had been swept a thousand miles east and north, over the Himalayas themselves, into a land of jealous seclusion, of strange lama rites, of unknown horrors. He would never get out alive!

His searching eyes raked the rumpled terrain of the shallow valley. There was nothing—no sign of the wrecked plane or of Saunders. A black cloud passed suddenly over the horned moon; its shadow raced gigantically over the valley, straight up the precipitous slope on the other side. Bayley's gaze followed it involuntarily. In spite of his caution, a low exclamation escaped him.

Something was moving in the heart of the shadow, a confused, wavering blob that seemed to be climbing the long slope. The cloud over the moon veered sharply to the east, and the obedient ground shadow moved with it. A procession disclosed itself momentarily—a long, thread-like movement of toiling doll figures. They were carrying something. Almost at the same time, toward the westerly slope, another group dissociated from the shadows, converging at an angle with the first. They, too, were carrying a burden. Then the cloud shifted back again; and the streaking shadow made one vast blob on the mountainside, blotting out all sight and sound in darkness as palpable as that first weird storm.

But Bayley had seen enough. It was not merely the processions. There had been something else. High up on the precipitous wall, the focal point of the converging parties, his eye had caught a light, a steady pin-prick of orange flame that seemed to emanate from the black mouth of a cave. The heart of the mystery of the night's strange, untoward events was there.

Bayley felt grimly for the gun under his torn, dirtied jacket. It was still in its holster, unharmed in the smash. He stepped out from the shadow of the protecting rock, and started down into the valley, gliding from rock to rock with the practiced ease of an Indian on the trail, careful to make no sound in his passage, merging indistinguishably with the blurred outlines of the rubbly steep. Whatever unholy mess was brewing, he was going to be present. There was Saunders, the pilot—he had been monosyllabic and dour enough, offended at the American the Peshawar officials had thrust upon him, but he was a white man. There was the girl, too. Her face had been hidden, but he was sure she was no Tibetan. Those stories of the frightened hill tribes came home to roost now; tales of strange rites and of a stranger god whom the lamas were worshiping in the hidden recesses of innermost Tibet.

He was past the valley now, and climbing steadily. There was no further sign of the two weird processions, but the orange flame gleamed steadily far above. The moon was gone; the cloud was spreading and blotting out the stars one by one. An hour of tortuous climbing brought him to the end of the trail. The granite wall of the mountain loomed perpendicularly overhead, a smooth, towering massif, unscalable, insurmountable. The unwinking flame had snuffed suddenly out.

Bayley searched desperately about. He must find a way in a hurry, before the shadows crept on him. Where had the processions gone; how had they scaled the tremendous cliff? There was not even a single hold on that smooth, vertical surface. The blackness was closer now, coming up in a wall of dead lightlessness. A last swift, despairing glance, and Bayley was engulfed. He seemed suddenly bodiless; a floating brain in a sea of nothingness.

But before the last sightless blotting out, he had seen something. Two huge boulders like giant guards at a portal, and a black hole that yawned between. It was only a dozen feet away, and he was facing it.

Without hesitation, he started forward, right arm extended, eyes closed to avoid the uncanny dark. Pebbles made odd noises beneath his feet. Then his outstretched arm hit with a thud. He felt around the smooth stone. He was on the verge of the opening. He paused a moment, cursing the fact that he had no flash. How deep was the orifice; was it a sheer drop or a path? There was no way of telling.

Bayley took a deep breath and inched his way in. It descended, but gently. A cold wind was blowing steadily outward. He kept close to the invisible side of the tunnel. It was going upward now. The wall seemed to angle sharply, and far ahead was a pale glimmer. There was an orange tinge to it. Bayley sucked his breath in with a gusty murmur, made sure his gun was easy-sliding in its holster.

There was light enough now to move a little faster. But the American redoubled his caution. He crept slowly along the wall. There was something artificial about its smooth, unbroken surface, about the well-worn condition of the path beneath.

The orange glow ahead grew stronger in intensity. There was movement beyond, and a confused murmur of sound. Bayley had his gun out, and his caution increased. He seemed but a shadow creeping along the wall. The flaming orifice ahead expanded; the murmurs took on shape and form. A chanting pulsed and fell. Drums throbbed in staccato unison.

Luckily the wall curved slightly as it reached the opening. Bayley threw himself down flat and wriggled forward, keeping to the curve. The sounds grew louder, the glow brighter. He inched his head warily around the bend, his gun extended a bit, ready to shoot at the first cry of alarm. The scene sprang full-orbed into view.

Bayley almost cried out, though his life hung by a thread. Never in all his wanderings had he come across such a sinister, blood-chilling sight.

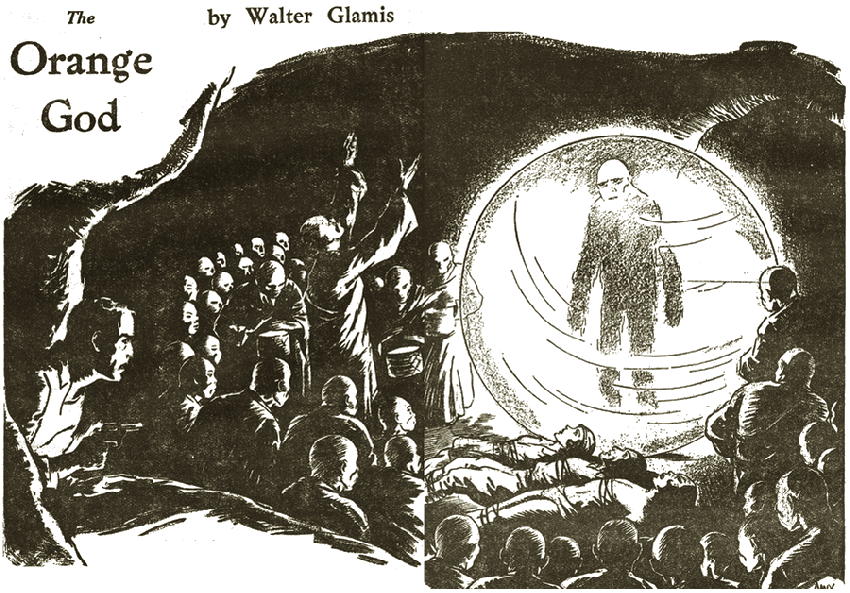

The great cavern, hollowed out to the shape of a perfect hemisphere, was aglow. Seated in concentric circles, like an audience in a stadium, were hundreds of Tibetans, lamas by the red robes of them, all facing inward toward the center, their dark faces aflame with the fires of fanaticism. Within the inner circle weaved a dance, red-clad figures swaying and drumming on tiny drums. A lama in a yellow robe, emblematic of a high order, face uplifted, back to Bayley, was chanting. "Om mani padme hum hri!" Bayley recognized that much; it was the sacred sentence of Lamaism.

But it was not the yellow lama, the drummers, or the crowded priests, that drew his startled gaze. It was the figure in the very center, the cynosure, the point of adoration of the assembled monks. Bayley had all he could do to stifle the shriek that rose to his lips, to control his limbs from jerking upright and carrying him in a mad race from that cavern.

A huge globe of crystal poised lightly on the ground. It was hollow, thin-walled, like a bubble. Within its clear depths, at the very center, unsupported, floated a figure. It was not a man. Bayley was positive of that—yet it held some vague resemblance to the human form. The body was elongated, and deep-orange in color. Sinuous appendages that might have been arms and legs hung limply down. The head was round and bald, and Bayley caught two round, unwinking orbs staring straight outward. The eyes, if eyes they were, were not malign. On the contrary, their inscrutable depths seemed filled with passionless wisdom, with infinite knowledge. Bayley had seen plenty of the leering, hideous idols the Tibetans worshiped in their religion. This was indubitably none of them. And it was alive!

The sphere glowed outwardly with a colorful iridescence, and immediately behind was the opening to the outer world through which Bayley had first noticed the flame.

Three figures lay bound on the ground before the globe. Bayley was just able to see them through a gap in the serried ranks. At the risk of discovery, he raised his head. His heart gave a great bound. One of them was a naked Tibetan, browned and dirty, his scrawny limbs trembling uncontrollably against the cords. The second was Saunders, his clothes in tatters, a red gash across his forehead. His dour Scotch features were more sullen than ever, eyes upturned to the great living idol. The third was a woman—the girl who had shrieked on the mountainside. She, too, was bound, prone on the ground. She was dressed in mannish clothes, breeches and puttees, and she wore a leather jacket. Her profile was pale and pure. A strand of glossy black hair escaped from under a close leather cap. She was not shrieking now, but Bayley caught a glimpse of even teeth clenched over a lower lip before he sank back to his hiding place.

The American's first impulse was to turn and run; his second to open fire. The first was rejected even before it was fully formed; the second was suicidal, and could achieve nothing. Yet something hideous was about to take place; of that he was sure. Wild thoughts flashed through his brain of that strange figure in the globe, of the weird ceremony.

But before he could evolve any plan, the chanting ceased; the drums stopped their monotonous throb. A hush fell over the cavern. The figure did not move, yet Bayley had a horrible intuition that it was speaking. Queer sounds beat within his mind; the tongue, the language, was unknown. It was not Tibetan; it had no counterpart on earth. Yet the Tibetan lama seemed to understand. He snapped out orders. Two red-clad natives stepped forward. They lifted the captive Tibetan, their countryman, high above their heads, while he struggled and twisted in his bonds. Bayley could see him plainly now. His hollow, dark features worked convulsively, foam dribbled from his lips, and scream after scream ripped through the stillness.

The supporting natives suddenly loosed their hold, and the unfortunate captive remained suspended in mid-air. His struggles ceased; he was rigid. The eyes of the sphered being turned to him. To Bayley, crouched and panting, there seemed a cool understanding in their depths. A bubble formed around the suspended Tibetan, a thin-walled globe. The light glowed stronger. It beat out of the opening into the void! Bayley had seen a star a moment before. Now a column of light extended out and up—up to infinity.

The sphere with its inclosed prisoner trembled and moved. It slid out along the orange column, as though it were a greased way. Higher and higher it fled, until it was a tiny speck in the glow; then it disappeared. Bayley again had that wild impulse to flee. This was not of the world of men and natural forces. But he was held, taut, cold, senses attuned like a fine violin.

The girl was being lifted!

She did not struggle. But, as she was turned in the movement, her finely chiseled face disclosed to Bayley blue-black eyes, large with repressed fear. A thoroughbred! Saunders, the dour, hard-bitten Scotsman, lapsed from his sullen silence—violently. He heaved at his bonds, his tongue loosened with a flow of hard, sulphurous profanity that would have warmed Bayley's heart under any other circumstances.

"Leave that girl be, you heathen swine!" he barked.

No one paid any attention to him; least of all, the orange creature of the globe.

The girl was halfway up when Bayley went into action. He flung himself erect, took careful aim, and shot at the great sphere. The roar of the .44 crashed, echoing through the cavern. Bayley raced forward, gun in hand.

At once the great sphere went black, and the entire cavern plunged into thick darkness. Bayley had a quick glimpse of startled lamas clambering to their feet. Then he was in the thick of a press of shouting, milling, sweaty, invisible bodies.

Left elbow stiffly advanced, gun clubbed, Bayley plunged on his way, straight for the spot where he had last seen the sphere and the bound victims. Cries of alarm gave way to screams of pain as he battered a path through the shaken mob. Hands clutched at his invisible progress, but he shook them off, and the gun butt rose and fell with deadly precision. Then he was through into a clearing. He stopped short. This must be the circle that had held the sphere. He groped around, finger on trigger for another shot. Back and forth he ranged in the blackness, arm blindly extended, while the clamor around rose to a solid roar of rage. A torch flamed in the distance. It was moving swiftly up the passageway. He must work fast before the light came, before the enraged lamas could locate him.

But the sphere was gone! There was no question about it. He ran in quick circles, and found nothing but thick darkness. The torch was nearing, bobbing and flickering with the speed of its carrier. Forgetting the mystery of the sphere, Bayley thrust desperately at the ground. He must free the girl first; then Saunders. But where was the girl? He was sure she had fallen somewhere around this particular spot, but his frantic groping disclosed nothing.

Just then the runner with the flaming wood burst into the cavern. A howl of triumph rose from a hundred throats. There was a rush of fantastic red figures to the area of illumination. Then the torch commenced bobbing forward. Its smoky illumination cast but a feeble light of long, flickering shadows, and the blood-lusting lamas who crowded in its wake seemed like a pack of demons on the trail of a damned soul. It wouldn't take long to discover the intruder.

The girl, like the sphere, had disappeared. Bayley paused. He could not orient himself to find Saunders. Seconds were precious now. A voice came up almost at his feet.

"Whoever you are, devil or man," it said in angry tones, "cut these cords so I can die with my fists going.

Bayley grinned and bent over, his hand questing. A large, wriggling body was underneath. He whipped out his penknife, flipped open the blade, slashed at interminable cords.

"Hurry, man!" the invisible voice expostulated. "They're coming fast."

Bayley sliced the last knot just as the searching, sooty flare caught at his bent form. The lamas saw him almost simultaneously. A howl of frenzied execration burst from the Tibetans. Arms upraised, they rushed forward. Steel glittered in brown fists.

Bayley ripped frantically, tugged Saunders to his feet. The pilot could hardly stand, so weak was he from the long confinement.

"Got a gun?" the American whispered fiercely. Saunders nodded. The sweat was pale on his brow, but he got at it somehow. His voice grew strong.

"Let the beggars have it!" he shouted.

The two guns flamed together. Steel-jacketed death tore through the massed onrushing ranks; the heavy slugs slammed and crashed through half a dozen brown-skinned bodies. The roars of hatred mingled with screams of pain and the groans of the dying.

"Think we can fight our way through the passage?" Saunders grunted as they fired again.

"Not a chance," Bayley said. "We'd be sliced for sure. Watch out! Here they come!"

The lamas had recovered from the first shock, and were coming with a deadly rush. The long, keen knives gleamed wickedly in the uncertain light.

Bayley had had experience with religious fanatics before.

"Can't stop them now," he said to Saunders as they pumped bullets into the compact mass as fast as triggers could jerk. Gaps appeared and filled up almost immediately. Suddenly the Scotsman stopped.

"No more bullets," he said casually. "It's been a pleasure to meet you. Good-by."

Bayley had two bullets left. The lamas were almost on them. He could hear the whistling of their breaths, see the glare to their eyeballs. The knives were plunging downward. Saunders had his gun clubbed, ready to sell his life as dearly as possible.

Bayley took a last careful aim and fired. In the background, the bearer of the torch howled dismally, and the smoking wood dashed to the ground, scattered sparks, and was extinguished. The cavern was in pitch darkness again.

"This way, Saunders," Bayley shouted, and threw himself sideways. A knife ripped down through his coat. Something red-hot seared his side, and warm fluid ran in a smear. The next instant he was the center of a struggling, howling mass. Luckily, in the dark no one knew his neighbor. The lamas were slashing at each other indiscriminately. Bayley tried to break through the weaving horde, but there was another rush, and he was borne backward, fighting desperately with fist and gun butt.

Back and back he went, ducking, weaving, feeling sudden stabs of pain as knives slashed at him and skinny hands gashed with razor-sharp nails. There was cold air on his back, a steady, strong wind. Bayley knew what that meant; his brow beaded with sudden horror. He tried to smash his way clear, but a solid wall of flesh pressed him remorselessly back.

Far away he heard a cry. It sounded like Saunders's voice, shouting words that were indistinguishable. Then something struck him—the concerted heave of fifty lamas. He was hurled back. His left foot tried to plant itself, found nothing. The wind was cold and dawn-fresh on his brow. Bayley staggered, clutched desperately. Then both feet went over, and he was falling. He had been pushed out of the cave opening, high up on the smooth, perpendicular wall of the mountain.

SAUNDERS found himself separated from the American almost immediately as the light crashed out. He heard Bayley's shout to follow him, but he was in the middle of as pretty a dog fight as he had ever experienced during the War. He smashed out with fist and gun, heard the grunts of pain, felt a knife wound in his shoulder, broke clear and dashed for what he thought was the direction of the tunnel.

He ran headlong into a wall, and the breath was knocked out of him. To the other side he heard the thuds and shouts of battle. He groped along, trying to find the path, when something gave way suddenly. He called out Bayley's name just as the wall opened. He found himself thrown into an irregular chamber in the rock, dimly illuminated with unseen light. Saunders shook his head and came to his feet with a bound. The wall had glided smoothly into position behind him. He was cut off from Bayley.

A whistling sound made him turn around sharply, and duck at the same time. That saved his life. A knife blade ruffled his hair with the speed of its flight, and ground with a dull thud into the wall beyond.

The lama in the yellow robe was standing close to a fat, obscene, potbellied idol that represented the Tibetans' degraded caricature of Buddha. He gibbered foul phrases as he plucked frantically at his sleeve, where another knife lay hidden.

Saunders's eyes slid past him to the mysterious girl, sitting rigidly upright on a cushioned dais next to the idol. She was not bound, and her eyes were open, but they had the peculiar stare of a person under the influence of drugs. Saunders's gaze jerked back to the lama. His arm was bent back! It held a knife.

The pilot raised his gun.

"Drop it," he said sharply. The gun was empty, and Saunders knew it.

The bluff worked, but in surprising fashion. The steel blade clattered to the ground, and the lama moved like a striking snake. He scooped up the immobile girl with one hand; the other went behind him. The Scotsman jerked forward with a cry of alarm, but it was too late. The huge belly of the idol swung open on hinges, disclosing a hollow interior. The Tibetan monk glided backward in a single flowing motion, the girl in his arms, and the idol closed with a brazen clang.

Saunders came crashing into a metallic, rounded idol just as mocking laughter floated hollowly up to him. He glared at the obscene visage, raised a huge fist to crash into its stomach, but withheld his blow. He would only break his hand. There must be a button concealed somewhere on the bulging belly.

He was fumbling clumsily when another sound burst on him. He whirled. The secret entrance from the greater cavern was open, and a horde of red lamas came pouring through.

THE AIR rushed upward as Bayley fell through the void. He knew it was a good thousand feet to the long, irregular slope beneath, yet he felt strangely calm. Events of over three decades of existence flashed through his mind as he dropped. The exploration of hitherto unknown portions of Afghanistan and the Gobi; the acclaim of learned societies; the last trek out of Nepal; the rumors of the god that had come to Tibet; the determination to seek him out after consulting with a learned friend in Calcutta who knew all the intricacies of Lamaism; the courteous air official at Peshawar; the dour pilot, glum at the thought of flying company; the strange storm; the god himself; and—the girl he had seen twice.

It was on the thought of her that he felt the sudden slackening of his speed. He looked upward. The orange sphere dazzled against the pale dawn light; the stars were burning low. Even as he looked, a cylinder of flame darted down toward him. It caught him in mid-flight, spun him round and round. Then he felt himself come to a breaking halt, hesitate, and start to rise again. He was being lifted through the air toward the waiting globe.

MARIAN TEMPLE came dizzily out from under the influence of the drug. By a tremendous effort of will she managed to force open leaden eyelids. She found herself lying in a luxuriously furnished room, the walls of which were covered with Isfahan carpets of intricate weave. The floor was piled thick, and the odor of incense hung dense in the chamber. At the farther end the yellow lama, his back turned, was engaged in mixing something in a brass mortar with a stone pestle.

The girl tried to rise, but the leaden weight of lethargic limbs held her down. She closed her eyes again to clear her head, then reopened them. Life was slowly flowing back into her numbed body.

The past twelve hours had been filled with horrors. Her lovely face, with the eyes that had been the toast of New York, was pallid now, drawn with fine lines of unending terror. From the time that their round-the-world plane had been drawn into the mysterious black storm over southern Siberia, she had not known a moment's peace.

This, she reflected bitterly, was the result of trying to be different. Bored to tears by the dull round of New York's gayety, she had snatched at Maxton's offer to take her as the first passenger on a globe-girdling trip. The papers had featured it—"Society Girl Seeks New Thrills."

She had them. Poor Maxton was dead under the crashed plane. The fantastic figures in red had risen out of the earth to seize her; the strange column of flame beat around her. The rest was mounting terror! The weird rites; the god in the crystal; the bound figures beside her; the sudden appearance of the white man. Then the battle—a bony arm lifting her, the sweetish capsule pressed between her lips, and unconsciousness.

She felt better now. She moved a leg cautiously, and the warm blood raced through it. She glanced around the room. The four walls stared back, unrelieved by door or other opening. Still, there must be one. The lama's back was still turned. She looked wildly around. There was no weapon handy. Yes, there was!—a small ointment jar of exquisite workmanship that stood on a pedestal at the head of her couch.

The girl slowly reached over for it, trying to make no sound. The grind of the pestle in the mortar filled in the rhythm of her movements. With infinite care she raised herself, raised the fragile jar. She hurled it.

As the missile left her fingers, the monk dodged suddenly. The precious vase thudded into a rare Isfahan, shivered into a thousand fragments. Yellow ointment streaked the reddish surface of the rug.

The lama whirled around, a scornful sneer on his brown parchment face. The skin was tight and smooth over high cheek bones; the lean, high nose was quite unlike the usual squatness of the Tibetans. His black eyes flashed commandingly. There was a knife in his hand.

In despair the girl looked around for another weapon.

"I shall have to kill you if you persist," the monk spoke surprisingly. "See!" He raised the keen blade and made a significant gesture across his throat.

The girl fell back.

"You speak English?" she panted.

He bowed mockingly. "Among many other tongues. I saw every move you made in here." He pointed to a tiny mirror set in the wall directly above the mortar.

Marian Temple stood erect. If the man knew English, then——

"What do you wish of me?" she asked. "If it's ransom, my people will pay——"

The lama interrupted scornfully. "Ransom! Ha! What do I need with that trash? Bits of gold that you Westerners kill and lie and cheat over!"

The girl was forgetting her terror in her curiosity.

"You've killed, too," she said pointedly.

"Yes, but for a different, a holier purpose. For power! Power over all men—the only real thing in a world of illusions."

"Why was I taken captive, then?" Marian asked.

The yellow monk smiled grimly.

"You will be the instrument of my power," he said.

She stared at him aghast. He did not seem insane.

"How?"

He threw up an arm.

"The Buddhas of Lamaism are outworn. Every lamasery has one; there is no merit in them. You are beneath one now. Can he breathe, or speak, or move? He is but an idol of wood and precious metal. I—I shall set you up, a warm, breathing, living goddess. You will be decked in gorgeous robes and gems. You will smile. The people will see—and adore."

Marian Temple tried to envisage herself as a goddess. Somehow she felt an odd sense of relief.

"Then the strange being in the crystal was just a mummery?" She breathed freely. That scene had lain like a hidden pool of terror in the back of her mind. "The whole ceremony was a fraud?"

The change in the lama astounded her. The arrogant, ambitious monk shrank fearfully away; his features worked horribly. There was a light froth on his lips.

"He—he was a god!" The words burst from him unwillingly. He was suddenly shrunken and old.

"Nonsense." Marian tried to put a positiveness into her voice that she did not feel.

The yellow lama glared at her. For one awful second she thought he was going to plunge the knife into her bosom. Then the words flowed.

"He came from above, I tell you, clothed in the globe and in light. Here to our monastery. The red monks bowed. I refused, and he struck me down. He ordered us to do his bidding. He spoke no language, yet I understood. I hated the god, but I dared not disobey."

Suddenly he laughed, mockingly, horribly.

"You are right," he told the terrified girl. "He is no god; he is but some mummery. The white man's bullet destroyed him." He advanced sardonically. "Goddess! You shall be worshiped, and I shall be the power in the land!"

The girl shrank back as far as she could. He came closer; she could feel his rapid breathing.

It commenced as a rumble and ended in an ear-splitting crash that sounded as if the mountain had been split asunder. The room heaved and rocked; the carpets fell violently off the walls. Luckily Marian was already flat against the wall; she was thrown, but not badly hurt. The yellow monk, however, was caught in mid-stride. He lay huddled against the farther side. The contents of the mortar, a greenish powder, spilled over his immobile face. Blood trickled slowly from the left eye.

The roaring ceased. The room trembled once more, as though the mountain had given itself a final shake, and there was silence.

The girl arose unsteadily, panting. Now, if ever, was her chance to escape. She took one step forward when a voice slashed through her brain. It was no outward sound, yet it said commandingly, imperatively: "Come!"

There was no denying the summons. She felt an irresistible impulse to obey. Her feet started to walk mechanically. The body of the lama rose slowly, rigidly, the green poison flecking his lips. It moved forward with deliberate, rigid steps.

He was dead—she was sure of that—the eyes were the eyes of a dead man, and the pallor of the face was a corpse pallor. Yet the dead man heard and obeyed!

She may have screamed. She was not quite certain of just what took place. The horror mercifully blotted out part of her memory. But she, too, went ahead, in back of the dead monk. Without a falter, he ascended a winding passageway, the girl directly behind. He pressed unerringly on the right spring within the hollow of the idol. The brazen belly opened outward, and they passed through—the dead man and the live girl.

The chamber of the idol was a veritable devil's caldron. The mountain-quake had sent huge fragments of ceiling rock thudding to the ground. The Buddha's head had broken off jaggedly at the neck, and the lolling, painted face leered wickedly up at them. But it was the procession that startled the girl almost out of her hypnotic obedience.

The red monks were marching. The living, the wounded, the dead; with faces rigid, with movements like mechanical dolls, they filed toward the opening that led to the great cavern where the god had been. In the very center of the strange procession strode Saunders, as rigid and as staring as any. He was bleeding from a dozen wounds. The lamas had not seized him without a struggle, and his dour face was set and hard. There was no flicker of recognition in his eyes.

The girl tried to faint, but a driving force impelled her on. Dead men walked along with her, corpses that moved their limbs up and down with regular tread. The living were but little better.

"If only I could faint and shut out all these horrors!" she moaned repeatedly—and walked ahead with steady pace.

They were through the orifice, streaming into the great cavern. The place was ablaze with orange light, and in the center, lightly poised, rested the great sphere. Within its bubble sheerness floated the god, the strange, elongated being with limp appendages and round, bald head. His eyes, Marian decided, had lost their inscrutability; there was a hint of weariness about them.

But more startling even than this was the sight of the stranger, the white man who had attacked the god and the lamas just as she was about to be sacrificed. He was standing close to the huge globe, nonchalantly, pistol in hand, and grinning! Yes, in the midst of that chamber of horrors he was grinning. A likable grin, thought Marian, the hypnotic power almost gone from her. He was tall, weathered, and lean.

The lamas, corpses and pseudocorpses, dropped heavily to the ground, and bobbed at once to sitting positions. The girl found herself constrained downward, next to the lama in the yellow robe. The glare in his eyes was fixed, the green poison on his lips, meant for others, had served as Nemesis. She shuddered and tried to move away, but could not.

Then the god spoke. Again there was no outward sound; the bald head did not move, nor were there any lips from which speech could issue; but the girl heard and understood plainly. There was the feeling of immense boredom.

"People of earth," he said, "insects of a tiny speck in the great void—of all the inhabitants on planets and suns, you are the dullest, the slowest witted, the least important. Sharkis will not thank me for the specimens I have returned for his curiosity. I am going. An infinity of worlds and an eternity of time await me; the very thought of your existence will be lost in the vastness. Sharkis will remember you no longer on my return. Farewell!"

The sphere glowed into a flame of orange, and the being within rotated once, slowly. Marian noted suddenly that Bayley's grin had not left him; that the gun was still in his hand.

A long, fiery cylinder extended outward like a released jack-in-the-box, through the orifice into the outer world—up through unimaginable distance to alien universes.

The sphere commenced whirling, slowly at first, then faster and faster. The strange being within was but a blur of movement. Then the rotating sphere commenced to slide up the path of light piercing the sky like a flaming sword. Out it fled into the early morning, where men toiled in the accustomed fields and women went about their homely household tasks; up the shining path through the pale-blue of dawn sunshine, until it was only a mote of shining dust in infinity. Then it was gone. The alien being was on his far-wandering travels again.

Within the cavern, as the ambassador from Sharkis spurned the earth from under him, there was an indescribable confusion. The strange hypnosis departed suddenly, and the upheld dead went limp, sprawling into loose-limbed heaps—corpses. The odor of corruption rose like a miasma.

The living rubbed their eyes, and were suddenly awake. A united susurrous of terror burst from the lama's throats, and with one movement they cast themselves prone on the rocky floor.

"The devil was with us!" they cried, and groveled in fear.

Bayley was striding toward the girl.

"Thank heavens you are safe," he said fervently. "I'm Ward Bayley."

"I—I'm all right," she gasped, with a little shudder. "My name is Marian Temple. Please—let's get out of this horrible nightmare."

"If we can," he answered grimly. His eye roved over the prostrate horde—the dead and the living.

"Saunders!" he shouted.

A figure tried to rise, and collapsed. Bayley was there in three steps, the girl right behind him. He caught the pilot in his arms. He was bleeding profusely.

"Not hurt much," muttered the Scotsman feebly, and fainted.

Bayley spurned a prostrate monk with his foot. His gun pointed threateningly. The lama sprang to his feet. Bayley spoke rapidly in Tibetan. The red one nodded and answered in short, explosive gasps. He was respectful. The others were rising now, staring at the three white people, but making no move.

"It's all right," said Bayley to the girl. "They think we're heroes. We've saved them from the devil. Come!"

He threw the large figure of the pilot easily across his shoulder, and followed the monk. The girl walked at his side, pulling away involuntarily each time they passed a dead lama. The other monks trailed after at a respectful distance.

Through many winding passages they went, illuminated by the flare of smoky torches, until they came to the monastery at the foot of the mountain.

There, for several weeks, they rested, while Saunders tossed in delirium, and Bayley had his own wounds dressed. The lamas tended all three with great care; they had routed the devil himself.

When at last Saunders was well enough to travel, the monks escorted them to the border of Tibet in a closed vehicle. No white man, they insisted, had ever set foot in this forbidden territory before; there were sights and sounds to drive them mad if they came upon them unprepared. Bayley smiled thinly, and did not protest.

In the jolting half light of the shrouded cart, Saunders did an unusual thing. He betrayed curiosity.

"What," he asked, "did you do to the being in the sphere to compel his departure from the earth?"

Bayley grinned.

"It was simple," he explained. "So simple as to be almost incredible. Remember when I took a shot at him and the globe disappeared?"

The girl nodded. It had saved her life, or, rather, levitation to an unknown universe.

"I only nicked a piece out of the substance of the sphere. When the lamas had forced me over the precipice, the ambassador from Sharkis was overhead. He was foolish enough to pick me up; thought I was a good specimen to send back to his master."

The girl was listening with parted lips. Her breathing came fast.

Bayley went on: "I found myself inclosed in a tiny sphere, filled with a peculiar fluid, not air, not liquid, but strangely exhilarating. The great globe was alongside, and the orange one stared out at me. I was desperate. Might as well die now as later, I thought, and, pulling my gun, I shot deliberately through my own inclosure, directly at the larger one."

Saunders said: "Gosh, what a chance you took!"

"It was the only way," Bayley answered simply. "The bullet drilled clean. I felt the rush of rarefied cold air into my chamber. But I watched the other. Something had happened. There was fear, actual fear, in the orange one's eyes. He seemed to struggle. The hole in his sphere plugged up almost at once, but I had seen enough.

"I pointed the gun threateningly, and said aloud, in English, that I could repeat the performance indefinitely. He understood, somehow, for there came to me a plea for mercy. I granted it on conditions. I learned afterward that guns were unknown elsewhere in the universe; that in spite of his almost supernatural powers, he feared a hole in his sphere."

"Why?" asked the girl.

"Our atmosphere was poison to him. The little whiff he got before he was able to plug it up almost killed him."

They rode along a while in silence.

Then Bayley chuckled softly.

Saunders stared at him glumly. His face was normal again; that is, dour and suspicious.

"What's the joke?" he demanded.

"I just remembered," said Bayley. "That pot-shot I took at the orange one was my last bullet. My gun was empty."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.