RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

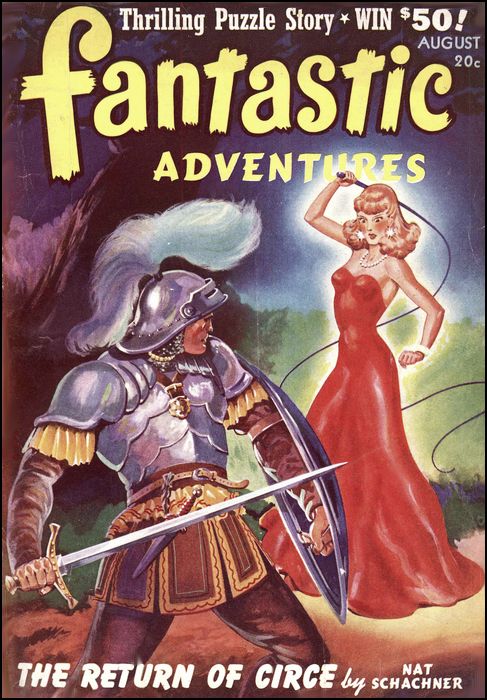

Fantastic Adventures, August 1941, with "The Return Of Circe"

Once again the loveliest enchantress of all time casts

her spell over men; and terror engulfs modern New York.

GORDON KEIL, so Mrs. Jenkins, his housekeeper, testified later, seemed strangely drunk on his return home the night that he vanished.

"Drunk?" echoed Detective Strang, cocking his head to one side in surprise. "That's funny. I've been scouting around among his friends. There ain't but one thing they all agreed on; and that was that Keil never touched a drop in his life. Wouldn't even taste cider, for fear it might of somehow fermented.' Now you go and say—"

Mrs. Jenkins pursed her thin lips in a hard, straight line.

"I know all that better'n you, mister. Once he caught me takin' a bit of a snifter in my own room—it's my stomick needs it; I gets queer spells like—anyhow, he almost fired me.

"But this here last night I'm telling you about, Mr. Keil acted drunk if I ever saw one. He just got out of the car an' walked right by me like he never saw me before, when I opens the door. His face was all flushed and there was a glitter in his eyes.

"I says to him nice and friendly: 'Did yer have a nice week-end out at Miss Kirke's?' But he sails by me like I was dirt under his feet. Me, what's babied him and put up with his nonsense this past ten years."

"Hmmm!" grunted Strang. He knew these hatchet-faced women. Give them a chance and they'd overwhelm you with words. "What'd he do next?"

"Went up to his room. Took the stairs three at a time, like-he was a boy, threw his hat sailing over the banister, and locked himself in." The housekeeper sniffed. "An' him with rheumatic twinges an' ulcers in his stomick an' hair that woulda be gray as a doormat if'n he didn't dye it once a month."

Strang disregarded the clinical details. Gordon Keil was the fifth man that had disappeared into thin air within the past month or so, and the Commish was pounding his neck for results.

"So that was the last you saw of him, eh?"

"Yes, sir."

"Wasn't it possible he went out again, and you didn't notice?"

She shook her withered head vigorously.

"He couldn't of. My room is downstairs next to the door. It was pretty hot, so I had the door open. I'd of seen him."

Strang scratched his nose.

"But damn it, there's no other way out. The upstair windows are all barred with steel gratings. You say you went up to his room about an hour later?"

"Yes, sir. I always do afore goin' to bed. Sometimes he takes a glass o' buttermilk for his stomick afore he goes to sleep."

"And the door was open, that he had shut when he went in?"

"Not only that, but he was gone. I searched everywhere—bathroom, the guest chambers, everywhere. Nary hide or hair of him."

Styang got up and paced up and down in exasperation. He was getting nowhere very fast; same as with the other cases. He whirled suddenly on the old woman.

"You sure there wasn't a sign of him around?"

"Well," she admitted reluctantly.

"Now that you mention it, I did find his wallet on the floor, and some loose change; like as if they had dropped from his pocket and scattered all over."

The detective snorted. Now maybe he was getting somewhere.

"Why didn't you tell me that before?"

"I didn't think is was important," she mumbled.

She thought she'd get away with the dough, thought Strang. Aloud he insisted.

"Anything else? Think hard!"

The woman looked suddenly uneasy. Her defiant, self-righteous look fell. She twisted her gnarled hands. Aha! thought Strang. She done him in herself. She's breaking; she'll confess!

"Come on, spill it!" he snarled. "I ain't got all day."

Mrs. Jenkins' glance was piteous.

"I swear I didn't touch a drop, even though my stomach was all misery. But I sneezed!"

Strang stared.

"Sneezed!" he repeated in bewilderment. "What the hell!"

"I'm this here now allergic," she explained. "Get a dog within a block o' me and I sneeze something terrible. There had been a dog in that there room not many minutes afore." She seemed to shrink into herself. "An'—an'—Mr. Keil ain't kept a dog for ten years. He knowed I couldn't abide them."

"Well, I'll be damned!" ejaculated Detective Strang.

BUT Gordon Keil had not been drunk that night. At least not on mundane liquors compounded of alcohol and other earthy ingredients. He was intoxicated—yes—but with a divine afflatus, with the ichor of the ancient gods.

He sailed by Mrs. Jenkins as he would have ignored at that moment the ruling monarchs of earth. Walking swiftly on clouds as he did, how could he be expected to note the inconspicuous passage of ordinary mortals beneath? His own exaltation lifted him up the stairs, not his feet.

An aging man, was he? Rheumatic twinges, eh? Dyed hair and stomach that was full of holes, hey? Nonsense! He was youth personified, virile beyond all other men; a Hercules for strength and a Mercury for speed.

As he shut the door and paced up and down his room the events of the weekend whirled with a sort of divine dizziness in his brain. Dea Kirke had smiled on him; Dea Kirke had invited him to her palatial Westchester estate; Dea Kirke had loved him!

He savored each little link in the chain of circumstances with a greedy running of his tongue over quivering lips. It was Wednesday last that the incredible had happened. He had sat morosely at an inconspicuous table at the Club Tabarin, fingering the glass of warmed milk and nibbling with distaste the dry thin Melba toast that represented his diet. He was solitary, alone, fed up with life. Then Dea Kirke entered.

Her entrances were always dramatic. She came in like a goddess—a darkhaired, full-blown beauty that caught the breath of the beholder. It was impossible to judge her age; she might have been twenty or she might have been two thousand. Like Cleopatra, the serpent of old Nile, she was timeless in her surpassing loveliness.

The satin smoothness of her ripe olive skin showed no trace of the passage of years, her deep-pooled eyes could ship from limpid liquidity to the flashing coruscations of embered fires with lightning-like rapidity. Her raven tresses were gathered in a simple, Grecian fillet at the nape of her neck, curiously old-fashioned, yet curiously effective. Her lips were ripely voluptuous and her bare arms firmly, yet softly molded.

For six months now Dea Kirke had been the sensation of New York. She had come like a visitation out of nowhere and took the town by storm. Mysteriously and fascinatingly foreign, her antecedents wholly unknown, she purchased out of seemingly inexhaustible funds a lovely estate near Armonk, in the Westchester hills. There she began to breed dogs.

But the word dog was too pale and innocuous a term for the magnificent animals that soon swarmed her kennels. Nothing like them had ever been seen before. They swept the Westchester Kennel Show clean of every prize. The judges raved. The other contestants likewise raved, though in different fashion. And every man within sight promptly fell in love with the compelling Dea Kirke.

NOW she came down the broad central aisle of the Club Tabarin, escorted by a strikingly unusual looking man. He was of medium height, barely as tall as the woman whose arm he held with such obviously passionate adoration. His powerful frame was faultlessly clad in black, silken-braided trousers and well-cut tails, but his face, framed in a broad, gray beard, was tanned and weatherworn with the passage of many suns and of many winters. A curious knowledge lurked in the finedrawn corners of his eyes and his nose was squat like that of Socrates. A French ambassador, one might have decided offhand, or a Balkan diplomat. But no one was deciding anything about him just then. All eyes devoured the lady on his arm. The headwaiter literally bowed himself into a knot as he greeted them; all conversation stopped at chattering tables. Men forgot the gilded partners they had brought with them; women bridled and suffered ineradicable pangs of envy. The dance floor shivered to a stop, and the orchestra seemed ludicrously frozen into an eternal soundless note. Admiration, desire, passion enveloped her as she moved in the wake of the flustered headwaiter to a table next that where Gordon Keil sat and sipped his arid drink.

If she were aware of the aura of desire with which the night club was suddenly impregnated, she showed no signs of it. She sank gracefully into the chair which the waiter solicitously pulled back for her; her companion dropped heavily into the other. They examined menus and ordered.

Gradually the stricken place stirred back into life. Men reluctantly averted their eyes to the accompaniment of low-pitched, but bitter complaints from their womenfolk. The orchestra resumed its ministrations, a sultry torch-singer came out into the spotlight and sang a sultrier song. The dancing couples took up their swinging and well-bred knives grated politely against food-filled dishes. Dea Kirke had made another of her inimitable entrances.

But Gordon Keil just sat and stared, the silly glass of milk forgotten in his hand. Her eyes lifted and met with his. A warm, frightening shock tingled down into his veins, brought back reckless youth and surging madness to the worn-out man. So that it did not even seem strange that she beckoned to him.

He rose spryly, almost ran to her table. Her depthless eyes were overpowering magnets, blessed pools in which to drown.

"Why, it is Gordon Keil," she said, and her voice held siren songs of melody. "I thought I recognized you, my poor boy, sitting there so forlorn. You remember, we met at that stupid party of the Van Wycks a month ago?"

Keil did not remember. In fact, he did not know the Van Wycks. In fact, had he ever met the lovely Miss Kirke before, it would have left etched memories in his brain. Therefore he only stammered and look vacuous.

SHE dazzled him with a smile. Her ripe, molded lips opened and showed white, dazzling teeth; tiny, yet sharply pointed. "Of course, Gordon," she said dulcetly. "You were interested in Doberman-Pinschers."

He stammered again. His knowledge of dogs was confined to poodles and wire-haired terriers. He wasn't even quite sure just what a Doberman-Pinscher was. Mrs. Jenkins couldn't abide dogs; so he never bothered much with the so-called friend of man.

The dazzling smile became a sunburst; it bathed him in a glory that befuddled while it stirred his senses.

"I was just thinking of you, Gordon." She turned to her companion. "Wasn't I, Ulysses?"

The man's face was black with suppressed anger. Yet he said smoothly.

"I believe you made some mention of Mr. Keil."

"Oh, by the way," she smiled, seemingly not noticing her companion's sulkiness, "this is Ulysses."

"Ulysses S. Grant?" Keil giggled.

"No; just Ulysses. An old friend of mine."

"A very old friend," the bearded man added grimly, with a strange side look at Dea Kirke.

"Don't mind him," said the girl calmly. "He's merely devoured with jealousy every time I talk to a personable man."

Keil bridled and straightened his tie. The last addled bits of his brain scrambled into mush. He no longer even wondered how the magnificent Miss Kirke had come to know his name, Ulysses glowered and shrugged his shoulders resignedly.

"I was saying," she went on, "that I have just obtained some perfectly exquisite Doberman-Pinschers. Knowing your interest in this particular breed, I wondered if you would be willing to spend the weekend at my estate—my kennels are on the grounds, you know—and let me have the benefit of your expert advice."

Her eyes seemed to enlarge, to swallow him whole in their seductive depths. In a daze he heard his voice replying thickly:

"I'd be delighted, Dea."

There! He had daringly called her by her first name. But she did not take it amiss. Rather, she positively beamed on him.

"Good!" she applauded. "Ulysses will call for you at seven sharp on Friday evening."

The bearded man growled; then looked alarmed.

"Fine," he corrected. "Not before."

Dea's full-throated chuckle was a rippling melody.

"But of course, my friend. I forgot for the moment." A long look passed between the pair; a look that Keil was to remember when it was too late.

PACING up and down his room now he tried to recapture that eventful weekend. It seemed almost frightening. The lovely lady, the glamorous Dea Kirke, had been strangely complacent. She had murmured passionate words of love to him during the sun-dappled days, but with shades drawn and doors securely locked, while outside a furious pack of baying dogs patrolled the spacious lawns and split the air with their clamor.

Sometimes he emerged from his swooning delight to listen with a curious unease. They sounded as if they wanted nothing so much as to tear him to pieces. In particular, one huge brute of a mastiff. There was also a curious giant of a man...

But her soft, clinging arms pulled him back, and all else was forgotten.

As night fell, however, the clamor ceased. Sinister quiet enfolded the place. Ulysses, absent all day, appeared as if by magic, his age-old eyes smoldering with strange fires. Abruptly Dea left Keil, doors and windows unlocked to the fragrant night, and vague alarms coursed through the lover she had left to his own devices.

The recollections brought the weary blood pumping once more through his veins. This evening, before a sullen and silent Ulysses drove him back to town, he had sworn eternal devotion to Dea. She listened to him with a faint smile.

"I'll remember that," she promised.

"But when will I see you again, darling?" he demanded passionately.

"Sooner than you think," she told him cryptically.

I can't live now without her, he thought to himself. Back and forth, around and around, he padded, a strange restlessness spurring him on. Padded! Why had that word sprung abruptly into his mind? He tried to stop himself. He couldn't.

Around and around the room he went, long-striding, almost at a lope. He blinked his eyes. By Heavens! he hadn't turned on the light! The room was in pitch darkness, yet he hadn't noticed. He, who always managed to bump clumsily into furniture even in full daylight, was now avoiding with instinctive ease unseen corners and sharp angles of cluttered bed, dressers, lounge and chairs. His eyes were wide and piercing; the darkness held no secrets from them.

Curious too, how he had suddenly become aware of certain subtle odors. His nose twitched and snuffed greedily. Each item in the room exuded a distinctive effluvia that he at once, without knowing exactly how, tabulated and catalogued.

A long, drifting smell lay across the room like a pall. That, he knew, and wondered how he knew, was Mrs. Jenkins, who cleaned his quarters every morning at nine. He could even tell what objects she had picked up or brushed against in the course of her ministering peregrinations.

WHEN he heard sharp sounds—the spatter of coins and metal keys upon the floor. Instinctively his hand fumbled for his pocket. They must have fallen out. But his hand was curiously clumsy. His fingers seemed stuck together; they could not enter the narrow folds. Then, even as he fumbled, the fold disappeared, melted away into a uniform rough fuzz.

Little alarm bells jangled in his brain. Again he tried to stop himself, to bring his padding lope to a halt. But he couldn't. His body drove forward, restlessly, bending over and over as if under an unbearable weight. His hind legs were becoming more and more unsteady. Hind legs! Why had he thought of that? And his ears! They were pricking up, twitching, sensitive to every vagrant wisp of air.

Suddenly he fell forward. His arms dropped to the floor with a sense of utter relief. He bounded ahead, swishing his tail. It was this last appalling fact that brought home the truth to him. His human brain froze with terror; then submerged under a welter of primeval instincts.

He was a dog! Lithe, long, blackly muscular, with sensitive snout and alert ears—a Doberman-Pinscher!

The dog ran snuffing around the room. A long, drifting smell called to him. It quivered in his nostrils; it beckoned with maddening desire. It led through the door, down the stairs, along the night-silent streets, over country roads to a certain magnificent kennel in the Armonk hills. His lean litheness wriggled with an ecstasy to be off, to follow that superb scent.

The door was ajar. In his earlier shape, without knowing why he did it, the man Gordon Keil had twisted the knob and resumed his half-pad, half-pacings.

The Doberman-Pinscher clawed open the wood with its paw. Down the stairs it bounded; a silent, bullet-like shape. Crouched low, a flitting shadow, it eased through the outer door, fortunately open because Mrs. Jenkins couldn't abide the heat. He saw her, rocking and fanning herself in her room; she did not see the low-slung, noiseless animal.

Out on the hard pavement the dog leaped northward with a whine of anticipatory delight, following that delectable scent all the way to its lair.

THE Garden was packed to capacity.

Home of fights and hockey games, of basketball and exhibitions, it now housed the premier blue-ribbon event in all dogdom. Nothing could be more doggy than the Universal Kennels show; nothing more aristocratic or exclusive. Every breeder, every exhibitor in the world pointed their best animals for the great event. A prize winner passed by the vigilant eyes of the judges had to be a world-beater, and its proud owner walked haughtily and superciliously among common mortals for years to come.

The huge arena was alive with color and movement. Tanbark covered the exhibition rings and the runways so that delicate pads might find the going soft and comfortable. Assorted aristocrats of dogdom, brushed and curried and sleeked to within an inch of their lives, sat each on his separate dais, awaiting the fateful approach of the judges. Huge mastiffs, bored English bulls, slim, fleet borzois, long-haired spaniels, impudent terriers, snarling chows and friendly airedales—grouped by classes and age.

The place was a weird conglomeration of yips and bayings and shrill barkings. Alternately proud and worried owners moved hastily among their pets, soothing the excitable, stirring up the phlegmatic, giving a last surreptitious primp to stray hairs and ruffled ears.

Chet Bailey patted a huge, tawny mastiff on the head.

"Buck up, old boy," he reproved him affectionately. "I know it's hard luck for you to run smack into that Ulysses brute in your first competition, but I'm rooting for you."

The great dog looked up into the gray eyes of his master as though he understood and whined. There was a certain similarity between master and dog, though the mastiff was built on gargantuan lines and his owner was lean and lithe like a fleet greyhound. But both had magnificent, rippling muscles that played under corded skin, and both had fighting faces, grim and stubborn with the determination never to acknowledge defeat.

Jessica Ware rested her gloved hand lightly on the dog's muzzle and evoked a low, deep growl of pleasure.

"Aren't you giving up too easily, Chet?" she demanded. "Every breeder who's seen this big, lovable old plug-ugly of yours thinks he's a champion."

The young man's gray eyes smiled at her, but there was no mirth in them.

"Sure he is; but Miss Kirke's Ulysses is in a class by himself. He's walked away with every show he's entered. Look at him over there."

There was no question but that the mastiff called Ulysses dominated the show. He was a magnificent beast—huge, calm, wise with a wisdom beyond that of the mere mortals who gaped and pointed and examined his fettles, his slim, steel-sprung haunches, his broad, mighty chest, the firm, smooth forepaws.

The girl stared at him with troubled eyes. The dog stared back calmly. Its eyes seemed to probe her, to weigh the human before him.

Jessica turned away with a little shiver.

"I got a strange feeling just then," she told Chet. "As though he were a bit contemptuous of us all. As though he considered us—humans and dogs alike—beneath him."

Chet forced a grin.

"Any dog breeder would agree with him. He'd tell you that a thoroughbred is the one perfect thing in this transitory, incomplete world." He stroked his own dog's head again. "Poor Warrior; I'm afraid you're going to be licked."

THIS time Warrior disregarded his master's hand. His great head swung in the direction of his rival. His powerful legs crouched under him as if for a spring, the short, wiry hairs became wire-bristles all over his body, and his red-flecked eyes retreated deep into their muscle folds. A deep growl, fierce with hate, rumbled in his chest; his fangs retracted in a long snarl.

"Hold him!" the girl cried suddenly. "He's all set to jump."

Chet's whipcord hand shifted to a firm grip on the collar.

"So he is," he said, surprised. "Down, Warrior! You'll get nowhere starting a fight. Take it easy, old boy."

The huge dog whimpered, but obeyed. Yet the hair continued to bristle and his wrinkled muzzle to quiver.

"He's never done that before," frowned Chet. "Usually he regards other dogs with a superb indifference." He bent down and snapped a chain from its rooted peg to the collar. "Safety insurance," he explained.

Jessica shuddered.

"He had the same feeling about that other dog that I had. Something sinister almost."

"Don't let your imagination run away with you," Chet advised. "He's uncannily perfect; but he's still a dog. Come on, darling. Let's take a last look at Pinafore before the judges start. Thank heavens Miss Kirke hasn't entered a Doberman-Pinscher. That means I have a good chance." He looked long at the girl. "If Pinafore wins, we get married tomorrow."

Jessica flushed. She was enough to stir any man's pulse even in repose; but when soft, pink color flooded her cheeks, the blood made a millrace in Chet's veins. Her body was slim, compact and vibrant with life. Her piquantly tilted nose contrasted charmingly with the serious intelligence that informed her wide gray eyes. Her short, golden-tinted locks always gave the impression of ruffling, sportive winds. Her chin was femininely rounded, yet strong and decisive nonetheless.

"I don't know why our happiness must wait upon a blue ribbon in a dog show," she said at length. "Even if Warrior or Pinafore doesn't win—"

"Please don't let's go over that again, darling," Chet retorted wearily. "I may be a failure, a has-been; but I'll never marry you to live on your money." His jaw went grim. "I've staked everything on this last chance. I know dogs pretty well; I've loved them all my life. Let me get a blue ribbon in this show, and dog fanciers all over the world will swamp me with orders. But if I don't—" He shrugged, and the lift of his shoulders was more eloquent than words.

Jessica shook his arm in exasperation.

"You a failure!" she cried. "Who saved the South Pole Expedition from disaster? Who threw a bridge across the San Pedro Canyon when every other engineer declared it was impossible? Who—"

Chet stopped her with a wry grimace.

"All past history, my love. Predepression, so to speak. The world is not interested in what you once did. It's what you're doing now that counts. And I'm raising dogs."

"For that awful Miss Kirke to beat," she stormed. "I hate her."

"That's not sportsmanlike," he reproved. "She has a knack—an uncanny knack. And—she's beautiful," he finished with a grin. "But come on; let's put the bankroll on Pinafore. At least he has a chance."

THE Doberman-Pinscher was beautiful. Black as midnight, long as an arrow, clean and sound in every limb. He wriggled joyously at the sight of them.

Chet took a deep breath.

"Thank heavens the ubiquitous Miss Kirke has no Pinscher—" he repeated.

Jessica's manicured nails dug suddenly into his arm.

"Hasn't she?" she wailed. "Look, Chet, look!"

The young man whirled; a sinking sensation at the pit of his stomach.

Already that breathless murmur, that swaying sound as of trees in a wind, warned him what to expect.

Dea Kirke was making another of her splendidly timed, spectacular entrances.

But Chet had no eyes for the siren face of the woman. He stared aghast at the dog who trotted submissively at her side, held in place by a slender leash. It was a Doberman-Pinscher, but such a specimen of the breed as he had never seen before.

Its coat was a burnished flame; its ears were sharply pointed and quivering with life. Its jowls, its deep chest and slender throat, the proud lift of its delicately poised legs, convinced him at once. Poor Pinafore, greatly bred as he was, didn't hold a candle to this phenomenal animal.

In a daze he heard Jessica's anguished cry:

"Oh, Chet; is that dog entered?"

"I don't know," he countered grimly. "He's not on the printed list. But I'm going to find out."

He went swiftly over to the group that had gathered as if by magic around the woman and the dog. The chief judge was among them.

"It's a bit irregular, Miss Kirke," he heard Kurt Halliday say doubtfully. "But if there is no objection'—"

"I'm sure there won't be any," Dea murmured, giving the white-headed old judge the full benefit of her smile. "Ah, here comes Mister Bailey. Ask him."

Chet disregarded the subtle intonation in her voice, pushed his way through the throng.

"What is the meaning of this, Mr. Halliday?" he demanded.

The judge stroked his thin white hair with distracted fingers.

"Why—uh—Miss Kirke wishes to enter her dog, this—uh—Doberman-Pinscher, in Class A competition, Division 3." He seemed flustered. "I know—uh—it's against the rules, but Miss Kirke has explained. The dog was shipped from the Island of Melos, and she didn't think it would reach here in time. That was why it wasn't entered. But as long as it came—" He made weak, washing movements with his hands.

"The rules are definite, Mr. Halliday," Chet said coldly. "All entries must be registered at least two weeks before the show, and the entry fee paid."

"You needn't worry about the fee, Mr. Bailey," retorted Miss Kirke. "As for that silly rule about entries, surely you wouldn't take advantage of a technicality like that. All the other contestants have agreed to waive the rule. Haven't you, gentlemen?"

HER beauty turned on dazzling full, like a million-candle-power searchlight. The men blinked in adoration. Freddie Gross, owner of Laddie II, said vacuously.

"None at all, Miss Kirke. It's a pleasure to waive every rule in the place for such a lovely woman as you."

"Thank you very much, Mr. Gross," she beamed.

"And that goes for me, too," George Lesser, owner of Jerry III, chimed in eagerly.

"And for me—and me—and me—" chorused the other contestants.

The judge lifted his arms.

"There you are, Mr. Bailey," he stammered. "Of course, you still have the right—"

Jessica thrust her way through to Chet.

"Don't do it," she whispered fiercely. "You know it isn't fair. Those men wouldn't do it for you, or for anyone else in the world but that—that woman."

Chet felt suddenly icy calm. He saw how it was. He knew what the papers would headline tomorrow. He knew that he'd be accused of bad sportsmanship, of taking advantage of a technicality. The victory would be ashes in his mouth. In a steady voice he said: "All right, I'll waive the rule, if the others do."

Halliday heaved an audible sigh of relief.

"Good, then that's settled. Come along, Miss Kirke; I'll place your dog. By the way, what's his name?"

Dea hesitated. An enigmatic smile flitted over her lovely countenance.

"Call him 'Chinese Gordon'," she said at last. Then to Chet: "Thank you! You are a gentleman—and a very personable young man."

But Chet had already turned on his heel; was stalking away, with Jessica holding bitterly to his arm.

"You let that—that hussy blind you with her charms; the same as she has done with everyone else. Oh, Chet!" she wailed. "You refuse to marry me until you have made money of your own; and now you've thrown away your last chance. You don't love me; you—" She stumbled as they went up the narrow corridor to the boxes. He caught her fiercely, almost shook her.

"You don't understand, Jessica. Every breeder, every dog fancier, would have me labeled as a bum sport. I'd be ostracized. The blue ribbon that Pinafore might have won wouldn't have meant a thing." His brows knit. "That story about the dog being en route from Greece doesn't go down with me. She could have entered him just the same, and withdrawn the name if he didn't arrive in time." He was speaking now to himself more than to Jessica. "I wonder where she really picked up such a worldbeater at the last moment. I thought I knew every pedigreed Doberman-Pinscher in America."

MATTERS went just about as Chet had expected. Dea Kirke's entries in all classes took the honors. There was not even the semblance of any competition. The judges lingered long and lovingly over her dogs, gave hasty, cursory examinations to the others, and announced the results. It was true that they lingered a moment over the mastiff, Warrior; but Ulysses won by a comfortable lead. As for poor Pinafore, he was literally swamped by the newcomer, Chinese Gordon.

Chet expected it, but he couldn't help the sensation of sickness that overwhelmed him at the final results. He had banked so hard on this Show. Jessica, next to him, was clenching her hands. He wasn't quite sure, but she sounded as though she was saying most unlady-like things under her breath.

Ulysses, the giant mastiff, was now being led out into the center of the arena. Dea Kirke, smiling that enigmatic, alluring smile of hers, had him on leash. Kurt Halliday raised his thin, veined hand for silence.

"The judges," he announced, "have unanimously decided to award the grand ribbon of honor for the best dog in all classes to the mastiff, Ulysses, owned by Miss Kirke. And may I add, that in all our years of breeding and judging, we have never had the privlege of examining such a perfect—superlatively perfect, I might say—specimen."

He turned to the girl, beaming.

"Miss Kirke, it gives me great pleasure—"

"The old fool!" Jessica flared with feminine illogic. "He's old enough to know better."

Chet tried to be fair.

"There is no question about it. Ulysses is—"

A deep-throated growl interrupted him. A huge, tawny shape shot like a bullet across the ring, straight for the calmly massive, unconcerned winner of the Grand Award.

"Warrior!" Chet shouted and left his seat like another bullet.

Instantly the great Garden was in an uproar. Shouts, screams, cries of alarm, a stampede by the timid and the frightened for the exits. A hundred dogs, infuriated by the clamor, lent their shrill voices to the din, strained at leashes to be in at the unexpected roughhouse that was impending.

Attendants came running across the tanbark, holding short, thick clubs in their hands. Dea Kirke turned, her eyes wide with a curious gleam. She did not seem in the slightest frightened at the apparition of hurtling death. Ulysses, the mastiff, swiveled on his haunches, bared his fangs with a snarl of defiance. There was an almost human quality to the sound. Kurt Halliday took one look at the oncoming dog and fled, his pipe-stem legs wobbling ludicrously as he ran.

WARRIOR meant business. Head low, powerful jaws agape, he bounded forward. Chet raced across the churning ring from the opposite direction. Once those two giant dogs locked in conflict...

"Down, Warrior!" he yelled. "Down, I say."

He might as well have saved his breath. The infuriated mastiff, ordinarily gentle and obedient, paid no attention to his master's commands. His deepset eyes were fixed in furious hate on the enemy.

Just as he sprang, Ulysses jerked loose from his leash, hurled forward to meet him. Dea Kirke, cheeks flushed, eyes glowing, clapped her hands.

"Why, its like old times," she cried.

Excited laughter was in her voice. "Go it, Ulysses, go for the Trojan Warrior."

Warrior lunged, his great jaws snapping. But they snapped on impalpable air. The mastiff, Ulysses, just at the moment of impact, had sidestepped nimbly, pivoting on stiff, straight legs. As the bewildered Warrior slid past him, he whirled, raked long teeth across sliding haunches and flashed back.

The outraged Warrior growled terrifyingly, clawed around to meet this strange, lightning-like attack. He charged again. Once more Ulysses leaped to one side. This time, however, he was not quite fast enough. A fang ripped across his jowl, leaving a long, red trail from mouth to ear.

A great roar burst from the injured dog. He leaped after the still-sprawling foe, all tactics forgotten. His teeth sank deep into Warrior's haunch. The great mastiff swung around, howling, seeking a hold with snapping jaws.

Then human beings were upon them both. Chet grabbed Warrior's collar, yanked with steel-strong muscles. The attendants laid heavy clubs methodically upon both animals, rapping smartly upon tender snouts. Ulysses broke away at once, whirled out of range. Warrior, doglike, struggled furiously to get once more at his enemy. His left hind leg was badly mangled. But Chet held him in a tight, firm grip.

"Down, Warrior!" he said sharply. "What's gotten into you?"

"It was your dog's fault, Mr. Bailey," panted one of the men. "We saw it all. He broke his chain and came out like a bat out of hell."

"I know," Chet acknowledged. "I'm taking all the blame. If there was any damage to Miss Kirke's dog, I'll make good."

To himself he was wondering how he could possibly pay. The dog, Ulysses, was worth a fabulous price. Any disfiguring scar would throw him out of future competitions. And he didn't have a cent. His last few dollars had gone into paying the entry fees. As for poor Warrior, he could never be exhibited again.

Dea Kirke's cheeks were flushed. Her dark eyes sparkled with strange, shifting lights. If Ulysses were superlative among dogs, her beauty outshone that of all womankind. She laughed suddenly.

Chet whirled in surprise. Across the arena he heard the anxious call of Jessica, hurrying to the center of disturbance; but all his nerves were suddenly tingling to the electrifying ardors in Dea's eyes.

"You needn't worry about Ulysses, Mr. Bailey," she said softly. "I wouldn't have missed that splendid charge of your Warrior for anything. You know—I like him—and you!"

HER glance was suddenly demure.

Her long lashes lowered to veil the sparkle in her eyes.

Chet's heart began to turn flipflops. Jessica seemed queerly faroff.

"Why—why, thanks a lot," he stammered. "You're taking it in a very sporting fashion."

She made a little gesture. Her lips quirked maddeningly.

"There are other dogs. To tell you the truth, I was beginning to weary of old Ulysses. He's been rather a bore for some time. Look!" she added as if on the impulse of the moment. "He's ruined your dog, Warrior. I'd be glad to show you just how I breed such marvelous animals. Would you care to be my guest for a week? We could put you up tonight. At the end of that time you'd know the technique perfectly."

Chet was astounded. Other breeders had clamored for a chance to see Dea Kirke's kennels, and had been turned down flat. True, she had entertained weekend male guests before; but none of them had been dog-fanciers. There had been Sam Wahl, for instance. Chet knew him slightly. Poor Sam had disappeared when he came back to New York. The papers mentioned something about the possibility of a defalcation in his books at the bank, but the police hadn't uncovered it as yet.

"Why—certainly—I'd be glad—" he heard himself saying.

Then Jessica burst in upon them. Her warm brown hair was tousled and her lovely face was compact in a tight, hard knot. Warrior tugged at Chet's restraining hand and growled furiously. Strangely, his eyes were fixed no longer on the Watchful Ulysses, but on Dea Kirke herself. His short hairs bristled, the muscles crawled and bunched under his bloody pelt, and there was hate and fear equally mingled in his gaze.

"I don't think, Chet," Jessica fought to hold her voice steady, "that you ought to accept Miss Kirke's invitation. She's done enough damage to you already."

Chet stared.

"Why, how can you say that!" he gasped. "If anything, I'm the one to blame. Warrior—"

"Warrior knew what he was about," the girl blazed. "You can trust his instinct. Look at him now. He senses that there's something wrong about that—that woman and her precious Ulysses." Her tone grew imploringly. "Please, Chet, don't go. I—I'm afraid."

"I think your friend is a trifle overwrought, Mr. Bailey," Dea said with a sympathetic air. "Of course, if you don't wish to come—"

Chet pivoted angrily on Jessica. "You're most unfair. I'm surprised at the way you're acting. Here Miss Kirke is acting like a sportswoman, and you choose this time to defame her." He swung back to Dea. "I shall be very pleased to accept your kind invitation," he said warmly. "I'll meet you after the Show."

"Chet, darling!" But he did not stop to listen to Jessica's anguished cry; he stalked stiff-leggedly away, holding the huge, unwilling mastiff firmly by the collar.

THE sun was beginning to gild the long, wavering line of the Palisades as the sleek limousine purred over the hilly stretches of the Old Country Road.

Dea Kirke seemed curiously uneasy as she glanced with calculating eye at the faint streamers of twilight. In the front seat, next to the chauffeur, Ulysses whined anxiously. To Chet, along with other strange incidents of this queer trip, it seemed that the whine held a peculiarly human note of urgency.

The woman leaned forward toward the open glass slide between front and rear compartments.

"You'd better hurry, Phemus," she said. "It's getting late."

The chauffeur twisted in his seat.

"I'm doing seventy now, Miss Kirke. But don't worry. We'll get back before the dark comes fully."

Chet noted that he pronounced her name as though it had two syllables—Kirk-ee. That struck him as strange; but certainly not as strange as the appearance of the chauffeur himself.

Phemus was huge—a veritable giant. His massive head grazed the roof of the unusually high-ceiled car. He must, thought Chet, be at least seven feet in height, and built proportionately. His eyes were frighteningly round as a saucer and baleful in their unwinking glare. Chet wondered how he had even managed to get a driver's license; wondered in fact if he had any license at all. But he seemed skilful enough at the wheel.

Chet was beginning to feel a trifle uneasy himself, in spite of the subtle, tingling warmth that pervaded him at this close proximity to the voluptuous woman at his side.

The car picked up speed. It was doing eighty now over the deserted road, swaying smoothly from side to side. He felt the woman flung against him, and her flesh was infinitely soft and all-pervading. In the delicious sensation he forgot to ask why, if they were in such a hurry, they had chosen this longer, lonely route rather than the straight, well-traveled Bronx River Parkway.

Armonk nestles in the fold of a hill. They swung off on a winding, dirt road that had the appearance of being but seldom used. The speed of the car became more urgent, the hurrying tension within more evident. The dog, Ulysses, no longer whined. He seemed to be moaning. In the gathering dimness Chet suddenly blinked. The great mastiff head was blurring on the seat in front—or was it some queer trick of the fading light?

Dea said encouragingly.

"We're almost there, Ulysses."

The dog whined in answer. It sounded as though a human being were having difficulty over the word:

"Hurry!"

The dirt road came to a dead end. A high stone wall, surmounted by barbed wire, stretched to invisibility through the tangled woods on either side. An arched portal, barred by a massive grilled gate, was directly in front. As the car hurtled forward without slackening its speed, Chet tensed his muscles for a crash. Was the chauffeur Phemus, mad?

BUT the gate swung open as they roared down upon it, and they went through in a spatter of gravel. A man stood at the gate, watching. Chet's nerves were jumpy. Again his eyes must be playing tricks on him. For the guardian of the gate towered in the gloom up and up and up. All that he could see in the half-light were a pair of giant legs—calves like the columns that upheld the great temple of Karnak; thighs that disappeared into the darkling sky.

It must have been his nerves, of course—or the light. For even as the car ripped through, the truncated mass shrank suddenly and formed a shriveled old man, bald as an egg and clad in a flowing black robe spangled with silver stars and crescent moons.

The limousine skidded with a squeal of brakes. The front, right door flung violently open while the car was still in motion and the dog, by now a blurry mass, bounded out and melted into the close-pressing trees. Even as it did, darkness came with a rush. The last sunset glow in the west faded and the stars pricked out.

The little old man came forward.

"You shaved it pretty close that time, Dea Kirke," he reproved. "The next time you will come too late, and then Ulysses—"

His voice was rusty and creaking like the hinges of an unoiled gate. His sharp-pointed face was hollowed with the ravages of innumerable years. He too pronounced the woman's name as though it were di-syllabic.

"It wouldn't matter much," she responded indifferently. "I am getting rathered bored with him, Atlas. Besides—"

The old man peered inside. His sunken eyes glowed in the darkness.

"Hello!" he said. "You've brought another visitor with you. Aren't you ever glutted?"

Her laugh was like the tinkling of ice in a glass.

"Never, Atlas. This is Mr. Chetworth Bailey, a breeder of dogs and a famous adventurer to boot. I intend to call him Chet."

Chet murmured some deprecating words. He was a bit dazed, and alarmed. It was bad when one's eyes began to play disconcerting tricks. First it had been the dog, Ulysses; then it was this little, weazened chap called Atlas. He'd have to go to an oculist when he got back to town. Perhaps he needed glasses!

Curious, too, the names of these people; these retainers and dogs with whom Dea surrounded herself. Greek—out of the old mythologies. The dog, Ulysses. The chauffeur, Phemus. Obviously a shortening of Polyphemus. Atlas. He grinned to himself. No connection there. Atlas had been a fabled giant who upheld the world on his brawny shoulders; and this—

He stopped right there, remembering that strange vision of columnar legs whose body was above the clouds. But that was nonsense, of course. Dea was a Greek by origin; she had acknowledge as much in connection with the Doberman-Pinscher, Chinese Gordon. And her marvelously classic beauty bore it out. Naturally she would cling by preference to the ancient Greek names.

THERE were no lights on the grounds. Only the dim stars showed the path on which they walked. They were alone—he and the woman. Phemus had driven away, and Atlas was gone. So was the mastiff, Ulysses. Deep silence enveloped them. A heady aroma breathed in his nostrils. With an effort he drew a trifle away from Dea.

"Where are your kennels?" he asked inanely.

"I don't need any," she replied. "That's part of my system. The dogs roam loose over the estate."

"But, good God!" he gasped. "You can't allow thoroughbreds to—"

The night seemed suddenly to close in on him. From all sides, as if by magic, they appeared. They rimmed them in a compact circle. Their tongues lolled redly in the starshine, their eyes gleamed like burning torches. From the smallest to the largest they moved stealthily forward, haunches close to the ground, ears pricked up, slowly but relentlessly narrowing the gap.

Tiny, vicious Pekes next to monstrous Irish wolfhounds, hairless Mexicans beneath the huge paws of Newfoundlands; chows, terriers, flopeared bloodhounds, bassets, skyes, pointers, Dalmatians, English bulls, shepherds—all the dogs that breeders had ever managed to rear and some that Chet had never seen before. Magnificent animals—every one of them—yet terrifying now in the way they stalked the humans who had ventured into their midst.

Hate and fear mingled strangely in their slow, bristling approach; overpowering lust to kill and rend alternating with a groveling dread—not of Chet, the man; but of Dea Kirke, the lovely woman!

Instinctively Chet sprang in front of Dea, trying to shield her. Instinctively his hand went to his pocket; came away empty. He had no gun with him.

"They're on the kill," he said low, but sharp. His eyes darted around for a path to safety. But the circle was close, impenetrable, and it was narrowing every moment of hesitation. There was a tree, however, close to where they had stopped. In another moment or so that too would be submerged under the approaching pack.

"Quick!" he whispered. "Get to the tree; but don't run. We'll have to climb it, or they'll tear us to pieces. Something's happened; I've never seen animals act like that before."

Her laugh rose startlingly on the night air, and the sound brought a terrifying response from the dogs. A chorus of sharp, explosive sounds, wholly unlike the barking of normal animals or the growl of stalking hunters. Rather it was the pentup fury of condemned men whose vocal cords had snapped under the commingled terror and helpless fury that held them in bondage.

"I do not run, or walk, from my dogs," she said calmly. Without haste her hand moved to her gown. It was a clinging, form-fitting—and form-revealing—dress of Nile green, yet Chet had not noticed the narrow, almost invisible pleat that ran from her hip down to the hem. She opened a tiny flap and pulled out a small, slender whip.

She cracked it sharply. It made a whistling, high-pitch sound that seemed to puncture Chet's eardrums.

"Down, you scum, you vermin of all times! Back, slaves, before I make you feel the bite of my lash! Away, before I sink you into the limbo of forgotten things! What, you seek to spring upon your mistress? Have you forgotten—?"

THE dogs slowed to a halt, stifflegged, bristling. Their jaws slavered with eagerness, yet a gathering dread glowed in their reddish eyes. She lifted the whip threateningly.

At the second sight of it they broke and fled. No sound issued from their throats, but terror winged their pads. As eerily as they had appeared, so now they vanished. Chet took a deep breath. It hurt his lungs. He had not realized that he had not breathed for long seconds, that every nerve and muscle had been tensed against the long, ripping springs he had expected.

"Whew-w!" He mopped his brow, wet with something that was not the dew of night. "I thought sure we were goners then." He whirled on Dea.

"For God's sake, what manner of dogs do you raise? They hate you worse than they hate death itself."

She favored him with a strange look.

"Now how did you happen to know that?" Then she smiled. "You're right. It's not death they fear, but rather this whip. They know exactly what it means when I use it." She thrust it deftly back into its sheath. "Some day they hope to catch me without it." Her smile held a new quality in it. "They've waited a very long time—most of them. But let's waste no more time on those brutes. We're almost at the house."

The night was warm, yet Chet shivered a bit as he went with her toward the turreted and battlemented castle that loomed before them in a park-like opening among the trees. It looked strangely incongruous in its Westchester setting—like a misplaced bit of medieval Europe. As indeed it was.

Chet remembered now. Some extravagant millionaire who, to please his romantic bride, had transported stone by stone, and lintel by lintel, a hand-hewn chieftain's hold from its Macedonian pinnacle to the peaceful hills of his Westchester estate. Hardly had it been laboriously reconstructed, however, when the young bride died; and the bereaved husband sickened at its sight had placed it on the market for sale. Dea Kirke had purchased it.

The great inner hall was truly baronial. Its arched stone vaulting sprang upward to the dimness of the roof, and innumerable recessed crypts melted into the shadows. No modern electric lights illuminated the interior; instead, huge torches of polished metal jutted from the buttresses and shot forth streamers of dazzling flame.

In the center of the floor's vastness a Small table was laid with gleaming napery and sparkling glassware. Huge, faceted bowls groaned under heaped fruits of exotic hue—pomegranates, wine-purple clusters of grapes, ripe, black olives, golden-skinned apples, figs with tender, bursting skins. A roasted boar elongated fiercely on a bronze platter with tiny yellow plums for eyes and tusks dripping a golden nectar. Haunches of venison, baby lambs spitted whole, plump partridges and other birds whose stripped identities Chet did not know, flanked the crisply browned boar. Wine of royal hue gleamed in tall goblets, and over all a peacock spread its magnificent, iridescent feathers, like a guardian spirit at the feast.

Two chairs were drawn up to all this splendor.

In one of these sat a man. His face was broad and squat, and a gray beard rimmed it in. Experience and the wisdom of much adventuring lurked in the tanned wrinkles that seamed his countenance and in the gray depths of his eyes. He rose impatiently at the sight of them.

"By Zeus!" he ejaculated, "I thought you'd never come."

DEA'S face was an inscrutable mask.

"The dogs thought to catch me unawares again," she said.

He moved toward her anxiously.

"You take too many chances, Dea. Some day they'll be successful; and then—"

She flung herself into one of the chairs.

"They weary me! I think I'll get rid of them all; ship them into the oblivion that they dread. It would serve them right."

The man nodded.

"I've begged you to do that these many centuries. I wish—"

He stopped; indicated Chet, who stood speechless and wondering, with a jerk of his head.

"Let him have his wine," he said bitterly, "and tumble him into bed. At least the nights, are mine, according to our compact. Zeus knows I have endured much for their sake." His voice trembled with thick longing. "Come, oh Kirk-ee!"

He flung out his arms in a pathetic gesture, turning his face to the left as he did so. A jagged rip from mouth to ear, recently wounded, glowed redly across his cheek.

Chet jerked forward angrily. Bewilderment and growing unease gave way to irritation. His fists were tight balls of muscular distaste.

"Now look here," he exploded. "I don't know who you are, and I don't give a damn! But I am no child to be disposed of as summarily as you seem to think. Miss Dea invited me here, and by God—"

The woman's voice was lazy, unhurried; but it cut across their smoldering passions like a sword blade.

"Stop it, my Chet! Stop it, Ulysses, you fool! You have been given credit for greater wisdom than to pout like a half-grown boy. Remember that I am mistress; now as always."

"Ulysses!" echoed Chet, and anger fell suddenly from him. His hackles rose and his blood prickled. He stared at the long, red mark with quickening horror. "Ulysses!" he repeated.

"An old friend," purred Dea. "You're thinking of the mastiff, are you not, my Chet?"

He forced himself into sanity, though the palms of his hands were wet.

"I was," he acknowledged. "Of course—"

"Of course!" she laughed, and her laughter was the music of many bells. "A mere coincidence. The dog Ulysses ran to join his fellows."

"A mere coincidence," Chet repeated obediently. But the hackles of his skin would not down. That new-made wound across the cheek—!

A shadow deepened the man's eyes. An age-old sorrow that swept through them and disappeared.

"Remember also our compact, Dea," he warned.

She rose with sinuous grace.

"I am weary of your remindings. Take care you do not overdo them. This night I yield to Chet Bailey."

HER smile enveloped the young man in folds of lapping languor. He forgot his fear; he forgot everything but the awareness of her beauty, her siren splendor. The memory of Jessica Ware receded into a faint, blurred wraith of far-off days.

"Sit with me, and partake of this simple repast, my Chet."

As one in a dream, suffocating with the throb of his veins, Chet sat down. The girl sat opposite, her eyes fixed on his, engulfing him in their liquid depths.

Ulysses trembled; anger flamed in his face. Then smoothly, as though a curtained drop had slid into position, it cleared. A crafty smile played over his lips, lurked in his much-enduring eyes.

"You are right—as usual, oh Kirk-ee," he said. "Permit me to drink the bond of fellowship with your latest guest."

There were three goblets of wine on the table. One held a golden-red liquor that flashed and coruscated in the flame of the torches. The second was a pale amber, beaded and winking at the rim. The third was a dark, rich purple, bloodied with the juice of sun-dappled grapes. He picked up the golden-red goblet, poured into a crystal glass.

He offered it with a courtly gesture to Chet.

"Here, my young friend; to your health and speedy metamorphosis." He stared at the glass. "How reminiscent is the color! I once saw an Irish setter with just such a golden sheen. But he was not magnificent enough for our Kirk-ee's kennels." He thrust it into Chet's hand. "Drink!"

With a mighty wrench Chet broke loose from his thrall. His brain cleared. Warning signals jangled in his temples. He jerked the lifting glass away from his lips.

"What sort of balderdash is this?" he cried. "Do you think—?"

Dea came at him with the silent speed of a serpent. She plucked the glass from his rigid fingers, dashed its contents onto the stony floor. Anger made terrible lights in her eyes.

"Beware, Ulysses!" she said furiously. "You are trying my patience beyond all reckoning."

The man fell back.

"I did but the usual thing," he mumbled.

"Begone! I am deathly weary of you. I am tired of your ageless jealousies. Tomorrow you shall drink the golden wine."

For a long moment their eyes clashed with lightning fierceness. Chet jerked forward protectively. But Ulysses suddenly smiled, bowed, and walked with dignified strides out of the hall. He did not look backward.

The flaming wrath wiped clean from Dea's lovely countenance.

"Pay no attention to him," she advised softly. "He is jealous, that is all. He shall annoy us no further. That drink he proffered you is inferior stuff. Its color is lovely, but its taste is sour and slightly rancid. I use it only as a decorative affair."

She picked up the amber-colored goblet, poured into another glass.

"Drink this, my Chet. I can vouch for this Melian wine. It is made of straw-colored honey gathered by the bees of Hymettus and of ambrosia such as the ancient gods themselves took greedily from the cupbearer, Hebe. It will fill your veins with intoxicating dreams beyond mere mortal delights."

HE knew that he should not drink it.

He knew that the whole setup was wrong; that this maddeningly beautiful woman and her pack of dogs had no right to be alive and breathing in the year 1941 A.D., in the United States of America. He knew now why the man, Ulysses, had that gash across his face. He knew—or rather, in the confused mists that dulled his ordinarily sharp and keen-edged perceptions—he knew that he ought to know.

Therefore he hesitated, fingering the seductive glass with its beaded amber liquid. She seemed to read his thoughts. She met his gaze with candid innocence. She poured another glassful from the same goblet while Chet watched suspiciously, seeking some trick of legerdemain.

She lifted it to her rosy lips, drank it down with a sigh of pleasure.

"Now do you see, my Chet?" she queried. "You need not fear."

It was true. There was nothing to fear. She had drunk the same liquor that she had proffered to him. He suddenly felt ashamed of himself. Ulysses, mad with jealousy, had tried to drug him with a dangerous drink. But Dea had saved him. Yet he had been suspicious. All these things could be explained—everything! Tomorrow, when he had rested and his mind was clear again, she would explain. Bah! Such things as had crept darkling into his brain would vanish with the risen sun. They would laugh and make merry over his eerie fantasies.

He lifted his glass, clinked it gallantly against her empty one, toasted: "To a lovely woman; to the loveliest I know—except one!" Then he drained it down.

The heady wine ran like liquid gold through his veins. It was marvelous stuff! Nectar and ambrosia indeed! Distillant of the gods!

Dea's face darkened at his toast; then broke into a faint smile.

"You refer, my gallant Chet, to the girl, Jessica Ware?"

"Yes."

"A very gallant lover," she said enigmatically. "Now let us eat."

They ate.

Her chair pushed close to his. Her hand touched his fingers casually as she carved the roast. Her thigh brushed against his body and made his heated blood to race. As she bent forward, her bosom betrayed its whiteness to his gaze.

The wine had been a potent drink; it flushed his cheeks and slurred his speech. It ran insidiously through the nooks and crannies of his being, and lifted with responding surge to the lady's overpowering charms. Her lips were temptingly curved; they parted with breathless invitation. He was slipping, falling into a chasm of beckoning delights. Her soft, warm arms moved toward him; her head bent slightly back and her eyes glowed. He swayed forward.

HE did not see the look of triumph that invaded her lovely eyes, the tiny, sharp teeth that hid behind her ripe, red lips. The image of Jessica receded wraithlike, despairing, thinning into misty smoke. Every fiber of his heated being yearned toward the delectable woman whose body slipped toward him with frankly open invitation; every guardian sense was clouded with wine and excitation. His hand went out fiercely, possessively... paused at the very moment of possession.

His blurred eyes went wide while little warning signals jangled in his brain. Was he seeing things? Had the potent drink so befuddled his senses? Dea's face was changing!

Her slim, straight nose, classically beautiful, subtly broadened and flared at the nostrils even as he stared. Her creamy olive skin, smooth as old velvet, crinkled into folds and pockets and turned yellow as discolored parchment. Little black bristles began to sprout from her upper lip. The tiny white teeth grew long and yellow and curved out over a quickly pendulous lip. Her eyes, those pools of unfathomable jet, narrowed and retreated into layers of fattening flesh. Little dartles of red streaked them as they blinked upward at his startled face. Her body grew compact and barrel round; her outstretched arms shortened swiftly and the seeking fingers coalesced.

He shook his head sharply, trying to clear away the fumes that gave him this nightmare. But the vision refused to change; became momentarily more dreadfully distinct.

She peered up at him in surprise out of those little red eyes.

"Chet!" she said. "What is the matter? Why do you shrink suddenly from me? Am I not lovely and desirable beyond all other women? Am I not—?"

At least that was what she thought she was saying. But to Chet it began with a series of explosive grunts and ended in a shrill, quavering squeal. There was no doubt about it—Dea Kirke, the magnificent woman who had taken New York by storm, was turning into a pig!

She fell forward from her chair, her sharp-pointed fore-hooves making a clumsy clatter on the floor. Her curled little tail quivered. Her sow-belly dragged pendulous dugs. She lurched toward him with a horrible travesty of sensuous longing.

Chet fell away from her in a revulsion of mingled fear and loathing. He was cold sober now. Good God! This lumbering sow, in whose piggish countenance he could still trace the fading remnants of a travestied Dea Kirke—he had almost taken her into his arms; had almost—

From outside he heard a man's sudden laughter. He whirled. Ulysses stood etched a moment in the oblong frame of the door, his broad, powerful frame glowing in the reflected flare of the torches, the night darkly sinister behind him.

"What does all this mean?" Chet cried out. "What hellish brew have you two concocted between yourselves? Let me out, I say."

Ulysses made no move. His voice was vibrant with scorn and self-contempt.

"Look at her! Look at the foul thing you thought to love—that I have loved her nigh three thousand years—because I cannot help it. She was bored with me, was she? She wished to install you in my stead, and cast me aside as she had cast every other mortal aside except me these many centuries? She knew me as a much-enduring man; but she forgot I am also a man of many wiles. I tricked her this time; I—"

FROM behind there came a great squeal; a furious, yet agonized snouting that trumpeted past Ulysses and hurled its mingled anger and anguish far into the night.

Hardly had it died before a new sound took its place. A sound as of monstrous feet thumping, shaking the earth with measured tread.

Fear sprang suddenly into Ulysses' eyes. The triumph was clean-washed from his cynical, self-flagellating face, leaving it a sallow-gray.

"Now Pallas come to my aid!" he mouthed. "He comes—the Father—to wreak vengeance for what I have done!"

He turned and fled incontinently through the door, speeding like a startled hare along the battlemented wall until the trees swallowed him up.

The thumps became huger and more earth-shaking. Great oaks bent outward as though they were slight reeds pushed aside by a careless-walking lad. The solid ground flattened and heaved with thunderous groans. The squeals of the bellied sow became more urgent.

Chet rubbed his eyes. Out there, in the scudding moonlight, two legs stalked toward him. They were as much around as the monster sequoias he had seen in California. The great feet, shod in yard-long sandals, crushed the smaller trees like splintering matches in their wake. Up and up Chet's gaze traveled—up to mighty thighs and giant torso that lifted to the darkling clouds which swirled around the moon. He saw no more. The clouds hid the rest. He wished to see no more.

Chet Bailey had never been afraid in his life. Not when a lion sprang out at him unawares from a bush cluster in the African veldt; not when he lost his dogs and sled with food and tent equipment down a deep crevasse on a solitary mush across Antarctic wastes; not even when his plane dropped a wing as it roared over the sawtooth mountains of Alaska.

But now he was afraid. Afraid with a hammering terror that pounded his flesh into pulp.

He turned and almost collided with the yammering sow. He skated to one side, darted madly across the polished floor, straight for the steeply curving stairs that went up into the reaches of the transplanted castle.

Below he heard voices. One was creaking, like the hinges of an unoiled gate, yet strangely gentle and soothing.

"There, there, daughter Kirk-ee, do not fear! Shortly you will return to your proper form. Though sometimes I wonder which it is—this, or that other. Your mother..."

The voice—it seemed to Chet like that of the little old man at the gate—paused and sighed.

"But never mind! How did this happen?"

The answer came in mingled grunts and squeals that gradually shaped into forming words and shifted into human tongue.

"It was Ulysses, father Atlas!" cried Dea Kirke. "He tricked me, even as he tricked me on the Isle of Aeaea. He added the drug to the drink, knowing exactly which I'd take. Father, rid me of him once and for all."

Chet's breathless speed took him out of earshot. He had to get away! What a fool he had been! Dea Kirke! Dea meant goddess! Kirke—di-syllabled—was the Greek pronunciation of Circe!

AN open chamber invited at the end of the hall. He flung himself inside, closed the door behind him, and hurled toward the slitted window. The outer stones were rough, he remembered. With gripping toes and fingers he should be able to clamber down and thread his way stealthily through the clustering wood toward the wall. Another climb and he would be out—out into the normal world of use and wont, solidly planted in 1941, anno Domini!

He leaned out over the deepset embrasure and fell back with a shudder.

The dogs sat outside in a tight, circumscribing ring. Back on their haunches, forelegs stiff, tongues lolling wickedly in the ragged moonlight, phosphorescent eyes glowing eagerly upward. A little growl of anticipation rippled around the beasts at the sight of him. They licked their chops.

There was no escape that way. Or any other! Suddenly calm, Chet surveyed the room. It was a bedchamber, magnificently furnished. A huge medieval bed with overarching silken canopy was soft and inviting with deep-tumbled featherbeds and gayly decorated cushions. Rosy little Cupids pursued amorous Psyches on the tapestried walls; and a wild boar bared its slavering tusks at bay before the lifted spear of a youthful Adonis.

But Chet could see no more. His eyelids weighted down. A drugged drowsiness fogged his senses. He tried to rouse himself. Fast-dimming consciousness warned him that it was dangerous to sleep. But his limbs sagged and his head drooped. He barely had strength enough to drag himself to the bed and fling himself into its cushioned comfort. Hardly had his limbs sunk nerveless before he was asleep.

His sleep was a long, shifting nightmare. All the creatures of unclean imagination paraded before him—chimaeras, griffons, gorgons with snaky locks, blind worms that crushed worlds in their writhing folds, harpies that chewed with dripping jaws on human flesh, assorted fire-breathing dragons and wild-eyed sphinxes. They glowered at him and came on in serried rows, jaws champing in horrid anticipation.

He tried to escape them; but every way he turned they sprang into being in his path. Their fetid breaths were in his nostrils, their fangs gaped wide. A clear, despairing voice sheared through their close-knit ranks, calling his name. A shudder rippled through them at the sound. They misted and disappeared as though the rising sun had pierced a fog.

The voice called him again. He knew the voice! With a glad cry he flung toward it.

"Jessica! Thank God you have come! Forgive me for—"

THE morning sun was dusting through the slitted embrasure as he leaped from the bed. There was the voice again of his dreams. Jessica's voice, bitter with that smoothly veiled contempt that only one lovely woman can bestow upon another, yet urgent with a fierce undercurrent of dread.

"I demand to see Mr. Bailey," she was saying. "We were to be married today. Don't hide him from me."

Dea Kirke's voice was equally smooth, yet cutting like a whiplash.

"It is a pity, my dear Miss Ware," she answered with irony, "that you have to search like this for the eager groom on your wedding morn. But I assure you Mr. Bailey is no longer here. Early this morning he remembered an appointment he had in town for noon. My chauffeur took him to the station."

"That's a lie!" Jessica cried. "It's just a week since he came up with you to this closely guarded estate of yours. No one has seen him since; he's vanished—just as half a dozen men have already vanished."

"By Atlas and Poseidon!" Dea's edged tones were like sharp little knives. "Do you realize what an accusation you are making? Those men to whom you doubtless refer all returned to their own homes. They were seen by their friends, their relations. If they chose to disappear afterward—"

"I know exactly what I'm accusing you of," retorted Jessica. "I'm accusing you—"

A masculine voice interposed hurriedly.

"Now, now, Miss Ware," soothed Detective Strang, "we mustn't say things we can't prove. I've checked those other cases with Miss Kirke, and everything was explained satisfactorily."

"To you, perhaps; but not to me. I know Chet. If I haven't heard from him, it's because—" Her voice choked off into sobs.

"Look, Miss Kirke!" Strang said with placating gesture. "Just to satisfy Miss Ware, would you mind if I searched your place a bit? Of course, I've got no search warrant, and you've got a right to refuse; but—"

Dea's laugh was merry and frank.

"Not at all, my dear Mr. Strang. My place is at your disposal. Go right ahead."

Chet was still drowsy and befuddled with his nightmares. The voices drifted up to him, making no sense at first. What did Jessica mean? A week since he had come here! What sort of nonsense was that? He had come only last night. And why did Dea deny his presence? Surely she knew he was up here. The window was open. In a second, if he wished, he could make his presence known to those below. In fact, that was what he was going to do!

"Jessica!" he shouted, and bounded toward the narrow casement. "This is a silly stunt! Why have you come—?"

But no voice issued from his throat. Instead, a dog barked furiously somewhere close by. He whirled. There had been no dog in the room with him. There still was none. Evidently the dream was thick upon him.

He shouted again. Again no words came forth, and that damned dog barked louder in his ears. He swung around, stiff-legged, glaring. If this was some sort of a jest—

His nose twitched suddenly, and his eyes raked down. He leaped high in the air, stunned, bristling; came down spraddling on four hairy, padded paws. Something swelled the corded muscles of his throat; issued in a fearful whine.

The realization froze him in his tracks, carved him into a marbled statue. He was a dog! A glossy-coated Irish setter, with reddish-golden mat, slim, long legs, long, sensitive muzzle and great, floppy ears.

DOWN below he heard human voices.

"There's one of your dogs howling, Miss Kirke. Wants to get out, I suppose."

"They always do," she agreed with easy calm. "Sometimes I shut one of them up in a room for training purposes."

For a moment that seemed eternity Chet was glued to the floor. His muscles were taut like drawn bowstrings. His breath came in snuffling little whines. His heart pounded madly within a shaggy breast. His ears perked up to cup the slightest whisper of sound. His brain seethed with stifling anticipations.

He was a dog—an Irish setter! Another in the string of magnificent animals with which Kirke—or Circe—had surrounded herself! The drugged drink which Ulysses had cannily switched on him had done this. For a week he had slept unknowing, while his human body shifted gradually to canine form. No wonder Dea was willing to let Jessica and Strang search for him. They'd never—

Like hell they wouldn't! With a grim bark he leaped forward, straight for the door. The long, lean setter took the stairs downward five at a time, a smoothly functioning, magnificent animal.

He whipped through the great entrance hall just as the outer portal opened and two women and a man entered. One was Dea Kirke—lovelier than ever. She was clad in a long, sleekly clinging morning gown of green silk, and her perfectly molded face was innocently smooth as that of a newborn child. Yet Chet saw, or thought he saw, the lurking semblance of that drop-bellied sow with broad, pink snout in her sinuous curves, in the droop of her ripe-red lips and curling lashes.

The man with them—Detective Strang—was rather stout for a detective; with grizzled hair and little eyes that peered everywhere at once. He held his black bowler embarrassedly in his twisting hands. There was an apologetic air about him at this unwarranted intrusion.

But Chet's eyes fastened hungrily on the other girl. Jessica's cheeks were pale with anxiety and fear. Her slim, taut body quivered as in a strong wind. Her gray eyes were hollow with nights of weeping.

"I want every cranny searched, Mr. Strang," she said huskily. "I'm sure he—he—"

"Of course," soothed the detective. "But I don't believe—He broke off at the sight of the hurtling dog. Involuntarily his hand reached for his gun. "There's one of your dogs loose, Miss Iprke!" he said sharply. "Is—is he vicious?"

Chet slid to a halt before Jessica. His silken paw clawed at her dress. His large, liquid eyes tried desperately to speak to her. He forced speech from his unaccustomed throat.

"Jessica, darling, you were right! Your intuition was perfect. I am Chet, who loves you more than anything else in this world. Help me, darling! Make Strang understand. She is Circe, the enchantress. Her dogs are men, changed by foul drink to what we all are. Help! Help!"

JESSICA reached down and patted his desperate head with gentle fingers.

"Why, he's not vicious!" she said. "He's a lovely setter; the most beautiful animal I've ever seen. Look at those great, speaking eyes. Listen to him bark and whine, as though he were trying to tell me something. There's something almost human about such a splendid animal as this."

Strang made a grimace.

"I don't care much for dogs. Not since one brute of a Chow took a hunk out of my leg when I put the cuffs on his master."

Dea smiled angelically on the detective.

"Perhaps," she murmured, "my pets would do the same for me if you—ah—tried to take me prisoner."

Chet redoubled his efforts. He wriggled his body; he whined frantically; he poked his muzzle into Jessica's hand. God! Couldn't she see? Couldn't she understand? Couldn't their mutual love break through the barriers and bring the imprint of understanding on her brain?

Alas! The barrier was insurmountable. He was a dog—nothing else to her. Her mind was clouded with anxiety, with eagerness to find her lover, unknowing that he was under her hand, desperate with effort to tell her who he was.

She patted him mechanically.

"He's taken a liking to me," she said. "But we'd better get on."

"Right," said Strang. "We haven't all day."

He moved quickly toward the walls, sniffed expertly around, shifted furniture, tapped every hollow-seeming spot, sought hidden traps.

"Nothing here," he said finally with a sigh. "We'll try upstairs now."

Dea watched him work with an enigmatic smile.

"My house is open," she invited. "You'll not find Mr. Bailey. Poor fellow! I'm really sorry for him."

Chet turned suddenly. A deep growl stirred in his throat. His hackles reared. Why hadn't he thought of that before? Here, before him, defenseless to his fangs, was the author of his transformation. If she were dead—

He sprang like a suddenly released spring. Straight for the throat of the lovely Dea Kirke. The growl became a roar. His lips retracted from snarling fangs. A red eagerness for that smooth white expanse, for the thin, blue vein that pulsed enticingly in a ravishing hollow...

Jessica screamed. Strang cursed and reached for his gun. But Dea only smiled. Her white hand did not seem to move, yet like a flash the slender whip lifted in her fingers.

"Back, slave!" she said. "Back or you writhe in eternal torture."

The whip whistled once. In midflight Chet felt an unbearable pain piercing his eardrums, his hate-filled eyelids. Molten fire ran like quicksilver through tortured veins. He fell to the ground, writhing, agonized.

She lifted it a second time. "Begone!" she said. "That was but a fore-taste. This time there will be no surcease, no escaping."

Chet groveled weakly on the floor. The terrible fire that burned him was subsiding, but he knew without further telling that the second time that terrible whip would crack, he was doomed to all eternity. He knew now why the pack of hating dogs had vanished at the sight of it. He knew now why they were her slaves, wretched in their animal forms, yet unable to revolt.

Jessica cried:

"The poor thing! He was friendly and gentle with me. You are his mistress; yet—"

Strang held his gun watchfully.

"You'd better shoot him, Miss, and be done with it," he advised. "I've seen 'em like that before. He hates your guts; an' he'll get his opportunity some day when you ain't looking."

Dea smiled her ravishing smile.

"He's not broken in yet. But he will learn."

Chet darted to his feet and raced howling through the open door, out into the park-like grounds. Ungovernable terror sped his pistoning legs. Circe was right. Another session with that magic whip, and his spirit—that dauntless spirit which had carried Chet Bailey, the man, through every physical danger—would be broken forever.

AT the edge of the wood he met the giant, Phemus. The man whistled to him. He swerved fearfully. The man whistled again. It had a friendly sound. The great eyes, that had seemed so frightening that night he had driven them up, glittered with sympathy.

"Come here, old fellow," roared the giant. "You're the last one she's taken in, ain't you?"

Chet stopped, barked tentatively. He was hungry for human sympathy, for the sound of a human voice. It was true that Phemus was not exactly human. Those great saucer eyes of his, his shaggy locks and uncomplicated mind. Not very intelligent, perhaps; stupid enough, in all conscience; but good-natured.

Chet came closer. The giant bent down, and patted his head with a huge ham of a hand.

"Yes, sir," he roared. "You ain't the first, an' you won't be the last. She collects men, she does, that she-devil.