RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

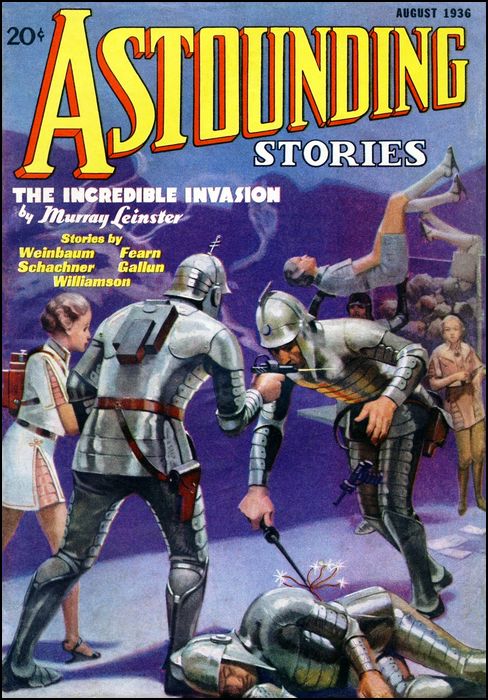

Astounding Stories, August 1936, with "The Return Of The Murians"

THE space vessel was traveling swiftly. Behind it stretched the vast, frightening reaches of interstellar space. Before it, like a faint, far-off beacon in the insensate void, a small red star glowed murkily.

For over five thousand years they had voyaged on and on, steadily, ceaselessly, two hundred and fifty miles a second, eighty billion miles a year. Time had ceased to hold any meaning; space itself was. an interminable nothingness in which they seemed suspended forever and ever. Only the cold, impersonal instruments, biting their records into indestructible drums, held the secret content Of their mighty odyssey.

Five thousand years! A half millennium since they had departed in haste and disorder from the single, inhospitable planet that circled the vast majesty of Sirius and its tiny, infinitely heavy companion alike. An eternity in itself.

Out into space they fled, navigating with painful fumbling, growing old, procreating their kind, learning anew with blood and tears the expert secrets of space travel, accommodating themselves once more to the little world of their ancestors' contriving, the only home they, and uncounted generations before them, had known.

Five thousand years, in which they lived and died and propagated; five thousand years without sight or sign of solid ground or the fresh, keen winds of heaven, without, snow or rain or mountains or oceans. "Night" and "day" were words whose meanings were long forgotten.

They were born into a gleaming round of metal and the circumscribed depths of the eternal void, and ultimately were cast out through the ports to drift in frozen entombment, ghastly, distended corpses.

This was their world, their planet—this swift-traveling, yet seemingly moveless vessel. They knew no other, knew nothing of the wilder, freer life, except for tales distorted by the mists of time and many tellings, legends that smacked, perchance, of wish fulfillments for that earlier Golden Age of their ancestors.

BUT now, for the first time, since remote Sirius, the void was taking form and substance, was concentrated into that murky redness straight ahead. For years they had steered for that beckoning flare. And now it was a disk, tiny, it is true, but perceptible to the naked eye.

The forward telescope showed it to be a star of the second order, a moderate sun already past its prime and succumbing to slow, degenerative processes. But no matter how they searched, they found no trace of satellites or swinging planets, solid bodies on which perchance they might find room and freedom and surcease from the frightening monotonies of an endless space.

The denizens of the great ship crowded round the instruments. A low, repressed excitement pervaded their veins, made them restless, dissatisfied. Was here the paradise of the olden tales, or was it but another barren star, incapable of supporting life?

With low, soft words, more whipping than any lash, Warlo, their leader, drove them back to their forsaken tasks. Life had become well organized, blessedly routine. It must go on. Obediently they scattered, each to his work, but oppressed with strange longings, with swift side glances through transparent ports at the small dim star that hung redly in the void; welcoming them to—what?

They were strangely human, this voyaging race. Only their color betrayed their different origin: A warm, golden skin that held within its shimmering depths the sun-dappled sheen of ripe, golden limes. Features more delicate and more clearly etched, perhaps, than those given to the ruder mortals of the planet Earth.

Warlo, his tawny beard and high forehead granting him a nobility his slighter frame could not, turned wearily back to his instruments. On him devolved the management of the space ship, the government of its thousand-odd inhabitants. Their strangely remote ancestors had builded well. The long ellipsoid of still unrusted, still unpitted metal was almost a mile from stem to stern, and half a mile in diameter at its widest point. It was a world in miniature, a closed cycle in which nothing was wasted, nothing dissipated.

The radiant walls still glowed as of old, though somewhat dimmer, and furnished light and the stimulating rays without which life cannot exist. One half of the ship—toward the stern—held earth and loam—in which strange plants—succulent, nourishing—grew and flourished. Stranger animals, small but fat and tender, grew to maturity in crystal-inclosed runs, bred their young, and paid the eventual penalty for all toothsome, subordinate forms of life.

By careful, exact measuring a delicate balance was established between plant and animal, between carbon dioxide and oxygen, between warmth and cold. A delicate balance, that called for unceasing, unremitting attention on the part of the leader and his corps of scientists; a balance, that, once broken, would lead to irremediable disaster.

A YOUNG man and a young girl stood close to Warlo as he busied himself with his instruments. Their golden, chiseled features were smooth and unlined, and they resembled each other. They were brother and sister.

Rone, the young man, asked suddenly of Warlo. "Still no sign of an inhabitable planet, father?"

The old, tawny-bearded leader looked at him with somber eyes. "No sign even of a barren one, son," he said briefly, and became absorbed once more in his charts.

"But that would be terrible," breathed the girl, her eyes wide with concern. "It is our last chance in the universe. We could never survive another long passage to the next star." She stared out at the white majesty of Alpha Centauri, more awe-inspiring in its tremendous distance than the nearer murkiness of the approaching Sun. "Almost three thousand years away," she murmured with a shudder. "Another eternity! And the radioactivity of the ship's walls is fading with accelerating rapidity."

"Won't last another two hundred years," affirmed Rone with a shrug. "After that—well, it's a comfort at least to know we won't be here to see the final smash-up of the race of Mur."

"How can you talk like that?" the girl demanded indignantly. "What matter our puny selves! It's the tradition, the old glories of the race that count. To think that our ancestors created this, that for unaccounted thousands of years the race of Mur has known no other home but a tiny closure in space—for what? For a dream, a vision, an unconquerable desire that this race of ours, without a counterpart in the universe, shall once more root itself on a lordly planet fit for us, to seek new heights of unimaginable civilization. It must not, it shall not die!"

"Sorry, Banda," Rone replied. "But you yourself admit this is our last chance, and a pretty rotten chance at that."

Warlo surveyed his children with stern glance. Already their high-pitched voices had attracted attention. Curious ears from the farther end were straining. "Silence!" he commanded softly. "Only you and the council of scientists know that secret. The others must not know, now or later. They have not our fiber to carry on in spite of inevitable disaster." His beard was stiff and grim. "There must be planets around yon faint star. There must!"

"We're still a year's journey away, and eighty billion miles," Rone broke in. "It is too far to be sure as yet. There might be a dozen and we would not know."

"Of course, my son," said Warlo.

"Suppose," Banda asked suddenly, "we find a proper planet. Suppose, however, that it is already inhabited with some form of intelligent life. What would we do in a case like that?"

"Not much chance." Rone grinned. "In all the legendary history of our race, there is no record of intelligent beings anywhere in the universe. The crystal hordes of Sirius were elemental, unhuman."

But Warlo said slowly. "I have considered that. In such an event, my daughter, we shall exterminate them, and take possession of their planet for ourselves. There is no room in a single world for two ruling peoples. One must go."

"But that would be barbaric, cruel," Banda cried out in shocked tones. "Surely we have no right——"

"Speak not to me of right," her father thundered in his beard, so loud that his people stirred and reared their heads from their tasks. "We are the race of Mur, and we have searched for eons for a final resting place, a solid habitation in which to recreate the ancient glories of our race. Nothing must come between us and our goal—neither opposing peoples nor natural forces nor the soulless universe itself. We must, and by our eternal ancestors, we shall triumph!"

NIGHT blurred the raw violences of the city of New York, made of its jagged outlines a thing fantastic, remote. Yellow lights pricked the dim loom of the upthrust buildings, vied in their exuberance with the cold, pale stars above.

Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Street, the crossroad of the world, was a roaring, surging tide of theater-going humanity. The public library was a squat monster, repository of the accumulated knowledge of the human race and the domicile as well of tattered derelicts, seeking its warm corridors against the outer cold.

Paul Mellish and Mark Sloan breasted he human tide with jesting words. They were in a hurry. The show was scheduled for eight thirty, and it was almost that now. Yet they savored the invisible breath of humanity, the raucous splendor of New York, with avid inhalations.

It was a long time since they had tasted civilization. Paul Mellish, in his forties, dark-faced and a bit well-fleshed, had just returned from the astronomical expedition that had established an observatory in equatorial Africa, on the frozen peak of the mountain of Kilimanjaro. He had been gone three years.

His companion, Mark Sloan, was younger and fairer of hair and skin, though burning desert suns had cast his features into bronzed leanness. He, too, had been in the far places of the Earth. He was an archaeologist, especially interested in tracking down all signs and remnants of the slightly fabulous continent of Lemuria.

Mellish sniffed deeply. "Give me," he quoted, "the tainted airs of New York, the effluvia of reeking humanity, and to the devil with tropic suns and 'antres vast and deserts idle.' Gosh, but I'm glad to be home, and for once forget what a telescope looks like."

Mark Sloan grinned. "I still hold for good old Lemuria, and the fabled Age of Gold. I'd exchange this sordid mess any day for that. But look, Paul. Even in materialistic New York you can't escape your vocation and pet aversion." Mellish grunted. A little ahead, crowded against the railing of Bryant Park, was a sight familiar enough to the hardened inhabitants of New York—a long, silver, gleaming tube, balanced on a great tripod, its nose snouting in eternal search into the immutable heavens. It was an itinerant telescope, set up on the sidewalk, bearing its legend:

See Jupiter and its moons. See the Great Red Spot. Only a dime a look.

Above, aloofly unaware of such prying curiosity, soared the white splendor of the giant planet.

"Bah!" said Mellish. "A peep show, a titillation for the ignorant! Come on, Mark, we're late for our show. Lord! I haven't seen one in ages and ages." But as they came abreast, some one was peering through—a woman, who had deposited her precious silver in the ascetic palm of the gentle and rather futile-looking attendant who squatted nightly before his beloved instrument.

Her head jerked up suddenly, and she stared with compressed lips at the commercial inviter to the stars. "It's a fake!" she exclaimed violently. "Trying to put things over on poor, unsuspecting people like that."

The frail old man shrank a bit from his customer. She was obviously not a woman to be trifled with.

"I—I don't understand you, madam," he quavered.

"Don't pretend ignorance," she said loudly. "Your silly old instrument is a fake. That ain't Jupiter; it ain't nothing. You pasted a picture on the glass, something long and narrow, pretending that's Jupiter. Look, you didn't have sense enough even to point it to the right spot. I want my dime back, you faker, or I'll call a policeman."

Sure enough, somehow the telescope had been jerked from its fixed position, was vainly scanning a totally different portion of the sky, barely clearing the sky-piercing tower of the Chrysler Building.

"I'm—I'm sorry," gasped the old man. "You must have kicked the tripod. Here—let me fix it for you."

But the woman—she was broad of beam and highly rouged—sniffed loudly. "I kicked it indeed. A pretty story. I suppose I pasted that picture inside, too. Like a silver egg, all shiny. Look!" she shrilled to her appreciative, rapidly growing audience. "There ain't any star up there, and he shows me an egg." There were guffaws at that.

INVOLUNTARILY, the two men had paused in amusement to listen to the altercation. They, too, turned and stared. The sky above the Chrysler was innocent of planets or bright stars. Certainly, there were no eggs.

Flushed, embarrassed, the man fumbled for a dime, pressed it on the woman. "Here, please, go away." Then his wasted hand reached for the polished tube, to swing it back to its stance on Jupiter.

"Come on," said Mark, "we're late."

But Mellish had jerked away. "Hold that," he cried. "Don't touch it." Already he was shouldering his way through the crowd.

The owner of the telescope looked up in surprise, with a bit of fear, perhaps. "You're not the police, mister?" he quavered. "What that woman said isn't true. I—I'd never do such a thing. I'm a real astronomer. Look, I belong to the Association of——"

"Don't worry," said Mark. "I just want to see what she saw, or thought she saw. My name is Mellish, Paul Mellish."

The old man stared at him raptly. "Paul Mellish!" he whispered. "Of course I've heard of you. Why, certainly, you may look. It's an honor I never dreamed of."

But Mellish was not listening. Already his eye was glued to the eyepiece, his practiced hand making quick, expert adjustments on the focus.

Mark's hand was heavy on his shoulder. "We're missing the first act entirely," he protested. "A 'peep show,' eh? A 'titillation,' is it? A busman's holiday, you really meant."

Mellish was still not listening. A sharp exclamation had burst from his lips; his eye seemed to bore itself into the lens.

The poor telescope man fluttered about in a haze of adoration. The great Mellish himself—and in person—looking through his instrument.

Mark looked at his wrist watch with a resigned shrug. Just like an astronomer, he grinned wryly. The crowd had scattered, seeking new excitements.

"Well?" he asked after a decent interval.

Mellish lifted his head. His dark face was aflame. "By Heaven," he cried, "the lady was right!"

"You mean, it is a pasted fake?"

"No, you silly fool. It's a celestial object, in a place where none should be. And it's ellipsoidal in shape. A new asteroid, perhaps, of an unusual type, or——" He shook himself almost angrily. "But that's too absurd!"

"What's too absurd?" queried Mark. Mellish did not answer. He was writing furiously in a little notebook the readings of the declination and hour circles attached to the telescope, jotting down the exact time from his watch.

"Sorry, old man," he muttered finally to Mark, "you'll have to take in that show alone. I've got to get over to Columbia. They have a pretty good instrument there."

MARK sat grimly through the last two acts of the light musical they had picked. Somehow the savor was gone.

After the show, Mark went to their hotel room. Mellish had not come in. But there was a telegram:

SORRY STOP THE COLUMBIA INSTRUMENT WAS NOT POWERFUL ENOUGH STOP I'VE GONE ON TO HARVARD BY NIGHT PLANE STOP WILL KEEP YOU ADVISED STOP PAUL MELLISH

Mark Sloan drifted impatiently around town for two days, waiting. They had planned this vacation together by cable and wireless, and now—— He called the Harvard Observatory.

They were polite, but evasive. Yes, Paul Mellish had been there, but he was now on his way by plane to Mount Wilson, where there was the 100-inch Hooker reflector.

"But what in Heaven's name is it all about?" Mark exploded.

Sorry, but they really didn't know. And, perforce, he was compelled to hang up.

Well, he thought angrily to himself, Mellish isn't the only one who can go crazy on a vacation. He had a wealth of material in his trunk on the lost continent of Lemuria. It would require a week of assorting and arranging. He had been too busy gathering specimens and data on his endless search to get around to it. A week, say, of utter retirement and quiet would do the trick—a certain remote lodge he knew in the Adirondacks, a summer camp, closed now. Its owner was a close friend.

It took a half hour to get wholehearted permission, another half hour to pack, and an hour later, a very determined young man, with trunk checked through, was on board the Montreal Express, roaring through the outskirts of New York.

FOR a week, Mark Sloan plunged into his work. The situation was ideal—a hunting lodge, fronting a wide lake, frozen solid almost to its shallow bottom, white with soft, new-fallen snow. Rolling mountains cupped them in, the only level stretch for fifty miles. It was solitary, remote. He was attended only by an elderly housekeeper who was taciturn and quite deaf.

Mark arranged his materials, went over his notes, studied his specimens in growing excitement. He forgot everything else, forgot even Paul Mellish. A picture was gradually piecing itself together—a picture of an ancient civilization, incredibly old, preglacial in time—the lost continent of Lemuria! There were little things he had found, worn and pitted by the passage of Heaven knew how many centuries, that only a high order of intelligence could have produced.

But one specimen in particular drew his fascinated attention—the broken, rough-edged remnant of a golden disk. He had dug it up on a tiny, unnamed islet in the Pacific—an islet that had not even been charted on the earlier maps. Perhaps some suboceanic convulsion that lifted it to the surface with recent years. Such emergencies have been known to occur.

It was an intricately carved bit. There were configurations on it in no known language of Earth; there was the incised figure of a being, provocative, tantalizing, broken off at a point where form and meaning trembled on the verge of explanation. It was infuriating. Mark felt his breath come and go a bit faster every time he turned the timeworn plate over in his hand. The riddle seemed insoluble. He began writing out a report, based on his explorations. He knew he was dealing with a controversial topic—this lost civilization of Lemuria—that a storm would be aroused by his conclusions; but that made the game all the more fascinating.

So it was that he did not know what was going on in the outer world. Pie could not have been more removed had he been on the high plateau of the Gobi or in the white wastes of Antarctica. He had laid in a sufficient supply of food; and no one came to break the silent tenor of the days. Nor had he left any forwarding address.

How then was he to know what the veriest savage in a remote rubber station in the Congo was already aware of; what Tibetan lamas in their odorous lamaseries, Arabs in their black felt tents, Ethiopians resting on their arms, cowboys on dude ranches, men in the mines and men on relief, knew and hearkened to with various emotions?

The whole Earth was in a temblor of excitement. Newspapers screamed 120-point headlines, the radios had special announcements every fifteen minutes, cutting across sponsored programs with ruthless disregard for property rights, in order to promulgate to a gasping world the very latest reports. Every astronomical observatory in the world was a swirling focus of activity, every amateur trained his homemade instrument on the strange celestial visitant.

Paul Mellish had started it, and the affair had grown from day to day until nothing else mattered. It was definitely established by now. It no longer required the great Mt. Wilson instrument to show the exact nature of the visitor from the skies. No longer could it be considered an asteroid, of strange shape and tiny size, following an eccentric orbit.

No! Even the Dyak in the Borneo jungle had heard what it was—a space ship, huge, ellipsodial, driving at terrific speed from the vast unknown, heading directly for the planet Earth. Closer, closer, it came, while observers followed every second of its flashing flight, calculating, checking, wondering.

At first there had been enthusiasm, unbounded, optimistic. The imagination of mankind was fired. The dream of centuries had come true. Communication between the worlds! Interplanetary travel! Extraordinary civilizations on Mars, far in advance of our own! Of course, they were from Mars. Lowell had insisted on that; Schiaparelli had anticipated just the event.

Scientists, etymologists, went into huddles. Mathematical methods of communication were hurriedly puzzled out; mathematics, of course, must be a universal instrument. Nations prepared huge welcomes for the distinguished visitors; the mayors of prairie towns hurriedly ordered free keys to the nonexistent gates of their anonymous communities.

BUT soon the first flush died. It was pointed out that Mars was then looping around the other side of the Sun, as was every other outer planet of the solar system. The strange visitant was heading for us as the port of first call, as it were, straight from the unimaginable depths of interstellar space. The thought was frightening; the implications grew more and more on thoughtful minds.

Who could envisage the nature of beings who must have traveled for thousands of Earth years? Where had they, come from? What was their purpose? Grim men looked about at the parlous state of their own planet, where beings of similar type, indistinguishable from each other to other-world eyes, were yet hating and torturing and murdering each other with great gusto and ineradicable fury.

They considered the white man invading the continents of so-called savages, and imposing this civilization with horrible results; they contemplated the spectacle of man, the superior, devouring the flash of cows and sheep and pigs; of the way of a wolf with a deer, of a fox with a chicken. All of them were life forms; all no doubt more closely akin than beings from Sirius or Antares with the denizens of Earth.

Fear and terror grew; both developed into overwhelming hysteria. Committees of welcome disbanded silently; orders for keys were cancelled. The dozen-odd wars between civilized man and his fellows were hurriedly patched up, racial distrusts, religious bigotries temporarily laid aside. A common peril faced them all—a peril all the more terrible because its very essence was unknown. Catastrophe approached the Earth, 200 miles per second, over 17,000,000 miles a day. In two days more it would strike!

The armies of the world quickly mobilized. Tanks limbered into action, battleships belched smoke, ready for sailing orders; bombing planes and waspish pursuits waited in serried ranks for the signal to take aloft.

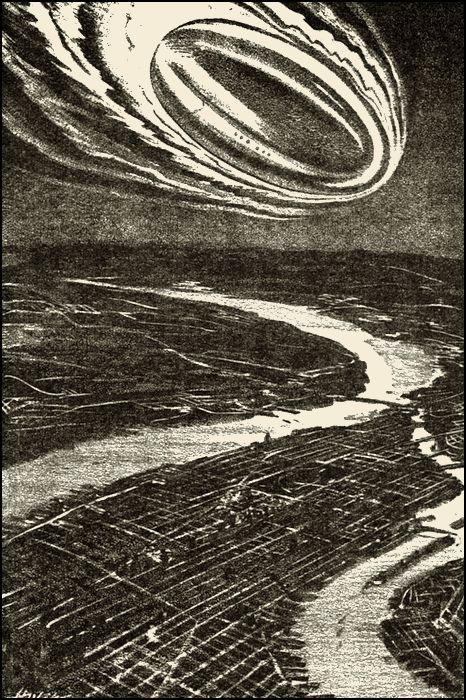

Then, on the night of January 10th, with every telescope in the world trained on its hurtling progress, the great metal ellipsoid braked its speed, whined through resistant atmosphere, and arced in a smother of flame and cometary splendor over northern New York, to disappear from the sight of man.

Then, with every telescope in the world trained on it, the great

metal ellipsoid braked its speed and arced in a smother of

flame and cometary splendor over northern New York.

A thousand photographic plates were rushed to development; a thousand visual observations poured into central headquarters in New York. Parabolic arcs were plotted, sines and cosines rattled off nimble fingers. A red pin was stuck into a map. Orders flashed out on radio, sang through telephone and telegraph. Tanks lurched forward into the night; heavily laden airplanes zoomed and departed in squadrons; helmeted soldiers entrained. The armies and fleets of the world converged on the designated spot.

MARK SLOAN had just crept into his heavily blanketed bed. It was late and his senses were numbed from too much work. He had written a good deal that evening, fumbling on the track of explanations that didn't quite come off. He was tired; so almost immediately he fell asleep.

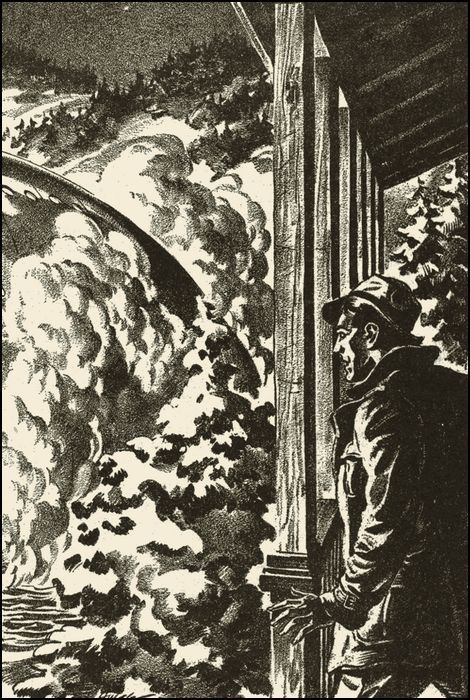

He was awakened somewhat later by what seemed an Earth-shaking cataclysm. He bounced out of bed to the thunder of screaming air, the blast of millions of pieces of artillery, followed almost immediately by a crashing, rending sound that caused the solid building to totter and sway. Outside, the frosty night was a sheet of blinding flame.

Somehow he dressed, hurtling into his clothes in seconds flat. Then he was racing through dark halls, catapulting through the door onto the log porch that fronted the lake.

He did not know it then, but the poor, elderly housekeeper was dead, already stiffening in her bed, the victim of a heart that had been unequal to the shock. As he shot out into the clear, cold air, he skidded to a halt with a cry of surprise.

Out in front there had been a lake, frozen to a depth of many feet. It no longer existed. In its place was a huge, unbelievable mass—an ellipsoid of metal, tremendous, impossible, filling the whole of the basin with its bulk, hissing, glowing with the impact of steaming ice and water on fire-hot flanks.

Out in front there had been a lake— It no longer existed.

Even as Mark stared in stunned bewilderment, little sections in the sides opened silently, and dark, ungainly monsters rose straight up into the steamy exhalations, hovered in the air as if trying to get their bearings.

Mark shrank back instinctively, with the caution of a wild animal in the presence of the unknown; but it was too late. The aerial monsters had evidently seen him. Simultaneously, they darted down for him, with a swoosh of complaining atmosphere, caught him even as he tried to race back through the door he had just quitted.

Struggling, twisting vainly, he found himself lifted high into the frosty night, like a young lamb in the talons of an eagle. Consciousness left him——

WHEN he came to, it was to a queer nightmare sense of a long sleep in which his brain had been prodded and probed, in which impalpable energies had flowed unceasingly to grant him an awareness, a knowledge that had not been his before his capture. He struggled to his feet, dazed, bewildered. No one held him; his limbs were free and unfettered.

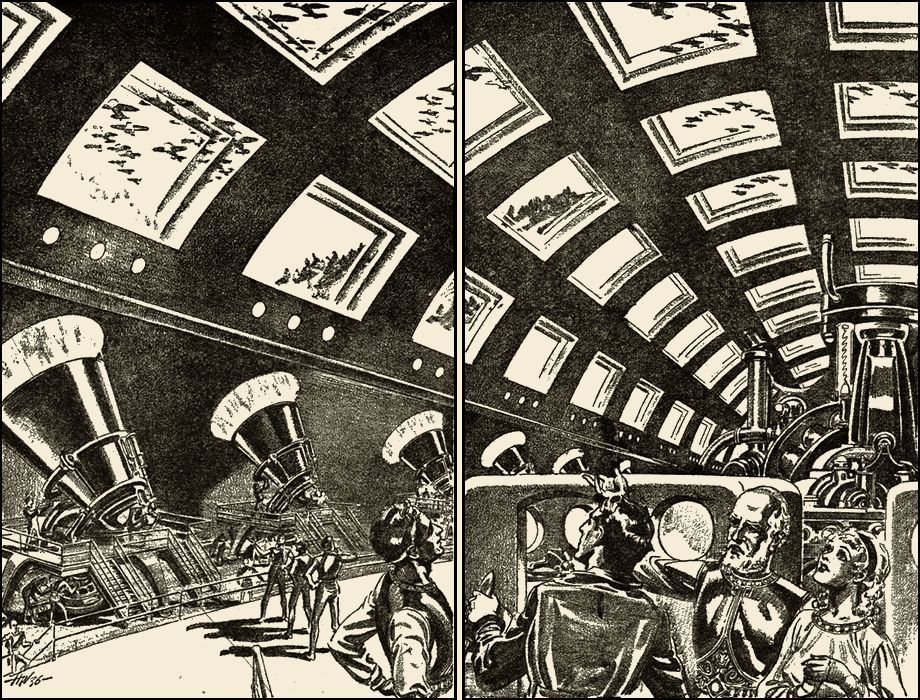

He seemed to be within an enormous arch of metal, a great flat dome that stretched interminably for tremendous distances. Everywhere was color and movement and ordered activity; machines that were totally incomprehensible; strange, growing things; an apparatus somewhat like a helmet attached by wires to a screen from which even now sound and symbols were slowly fading. It seemed to him, dimly, that the helmet had been clamped to his own aching head, that currents had flowed into his mind while he had slept. It was a world within a world, a tiny cosmos inclosed in the orbit of this monstrous structure.

THREE figures stood immediately in front of him, watching him with patient eyes. Mark blinked suddenly. Was he dreaming or were they real? Had his brain suffered shock or the impact of a fractured skull, and were these the creatures of some incredible, delusive fantasy, the visions of another world and time?

Yet in shape and form they were human, albeit somewhat slighter in stature and more delicately molded of feature. It was their coloration, aside from the glitter and cut of metal-shimmering garments, that made them of another race than the denizens of Earth. They had warm, golden tint, curiously attractive, that made his own bronzed body seem somehow pallid and unhealthy.

The oldest had a tawny beard and high, bald forehead; his eyes were penetrating, yet disconcerting in their scrutiny, as if, thought Mark a bit uneasily, he, Mark Sloan, were a new species to be studied scientifically and catalogued.

The second was also male, a younger edition of the older, beardless and delicately smooth of face. His gaze was faintly amused, mocking even. But the third somehow caught Mark's breath, so that he had difficulty for the moment in his respiratory functions. She was obviously a girl, slender, yet subtly rounded. Her face was a perfect oval, the golden orange of her skin a miracle of tinting. She was indescribably beautiful, exotic.

"It is time that you awakened," said the bearded figure. "There is so much we must know from you, and quickly."

Mark started. Somehow he understood the liquid syllables, yet the language was not of Earth. He prided himself on his knowledge of the polyglot speech of mankind.

The young girl smiled. "You learned our tongue while you were asleep, oh man of this strange planet." She indicated the helmet with a nod of her head.

"It is the method we employ to teach our children. A succession of images and speech impinges on the receptive centers of the brain. It saves much time and trouble."

Mark collected himself with an effort. "But I do not understand," he protested. "Who are you? Where do you come from? What is the meaning of this huge structure, and why was I taken prisoner?"

"Softly," rebuked the old man. "We have no time for explanations. It is enough that we are the people of Mur, far wanderers in the universe, come at length to a planet that seems ideally fitted, from the hurried tests we have already made, for the colonization of our once glorious race."

Mark stiffened. "Colonization?" he echoed. "This planet is already inhabited. We have two billions of human beings like myself to crowd its surface. There is not much room for newcomers, unless"—and he looked doubtfully around at the people of Mur, who were moving with ordered efficiency along the spaced ports, shifting and tightening funnel-like bits of apparatus into position—"you are but these few, and are willing to accept a restricted area for your colonization. In that case I am fairly certain our governments could make some provision for you."

The old man's golden, seamed face turned a hue of greenish mold. The strange syllables of his speech crackled and spat. "You forget, young man, that the children of Mur come not as humble suppliants to the obviously primitive denizens of your world. They come as masters, who have sought for countless thousands of years for such an haven as this. Our race is prolific, once the inhibitions of our confined quarters are removed, and they will people this universe-sent planet within a generation."

Mark restricted his growing anger with an effort. After all, he reflected, he was a prisoner and subject to sudden death if he offended his captors.

So he only said. "And what, pray, do you intend to happen to the present luckless inhabitants, once your people of Mur spawn over the Earth?"

"Get rid of them; exterminate them," the old man answered promptly. "We are sufficient to ourselves. We require no lower order of beings for slaves."

"Father!" the girl burst out suddenly. "How can you talk that way? Our guest will think——"

"S-s-sh!" warned the young man uneasily.

But her father had heard, and the dull green of his features mottled. "Keep quiet, Banda!" he snapped. "What are you saying in your folly? This young native is no guest. He serves our purpose. When we are through——" He paused, but his silence was more eloquent than any further words.

MARK paled. He could fill in the lacuna himself. Nevertheless he was grateful to Banda, the girl. Her magenta eyes showed compassion; her little fists were clenched with suppressed emotion.

He turned steadily to this ruthless bearded one, who had come from outer space. "You may kill me, if you wish," he said calmly, "but you will find me of no service in furthering your nefarious plans. Nor will you find your little war of extermination as simple and easy as you seem to think. You have here less than a thousand. We, the natives, are some two billion."

The bearded leader smiled. "They are as easily destroyed as a single one. We have weapons."

"So have we," Mark retorted. "Possibly we are as civilized as you. You have erred in accepting this rugged wilderness of ours, to which chance has led you, as a sample of our world in toto. You are wrong, as you shall soon see."

For the first time doubt, hesitation, showed on the Murian's face. "Weapons?" he repeated. "That is what you are to tell me. What manner of weapons have your people?"

Mark grinned and shook his head. "Enough to destroy you and all your kind," he answered confidently. He firmly believed in what he said—for how could this puny handful, even though they had mastered the secrets of space travel, overcome the massed might of the nations' armaments?

Yet somehow the thought gave him no exultation. In spite of their leader's declared intention of conquest and extermination, there was something strangely lofty and superior about him and his kind. Especially the girl. Banda, who, since her rebuke, had taken no further part in the conversation, but listened, with tight lips and sidelong glances, in a manner that left him no doubt where her sympathies lay.

The bearded Murian frowned. "What are they?" he insisted. "We have means of making you tell."

Mark looked him squarely in the face. "None of them will work. If you persist in your cruel adventure you will find out in due course, but not from me. My advice, given in all friendlineess, is to take off from Earth once more and seek your home on Venus, where doubtless there is no inhabitant race, and where conditions should prove livable." The Murian did not twitch a muscle. "Rone, my son," he said calmly to the young man at his side, "take this stubborn primitive to the dissector chamber for scientific examination."

"No, no!" Banda threw herself forward, in between her brother and the stranger captive. "Rone! Warlo, my father, you must not! Don't you see? Fie is right, this native. He is brave—and civilized, even as we. We are interlopers, invaders. They had lived and cultivated their planet since time began. Let us take his advice, seek this other, uninhabited world of which he speaks. Please, father!"

Warlo looked impassively at his pleading daughter. Without raising his voice, he repeated. "Rone, take him to the dissector chamber."

Mark tensed his lithe frame desperately. He'd be damned if he'd go. Rather fight and die here, than in that place of which the girl seemed in such horror. Rone moved toward him, his face as impassive as his father's, but his greenish eyes were filled with queer reluctance. Mark balanced on his toes, ready to leap with fists flailing.

BANDA'S cry held them all in moveless tableau. "Father, look! Those machines!"

All eyes swerved to a gray metal plate. It had illumined suddenly, was glowing with depthless space. Within its seemingly dissolved interior the outer world was visible; sky and snow-capped mountains and the Adirondack wilderness. The air was filled with great, droning planes, the roar of their motors plain to be heard—huge bombers, heavily laden, flying in perfect formation, each bearing on its underwing the painted American flag.

A thrill of pride and exultation coursed through Mark. His brave countrymen were coming to the rescue, speeding to the defense of a world endangered by the appearance of this strange visitant from space.

"Now you shall see what the Earth men are capable of," he boasted somewhat vaingloriously. It did not matter that he would also die in the inevitable salvo of undiscriminating bombs. His life was cheaply sold for the salvation of Earth. But the girl! Without quite knowing why he felt this way, he added rapidly and in a whisper. "You had better run for it, Banda. Get out of this ship and as far up the mountain as you can before they begin to bombard us."

Her violet eyes flashed as she raised her slight body to its fullest height. "I am not afraid of death, oh stranger. Nor is any Murian. Nor do we fear the weapons of a barbaric race."

Mark moved back, deeply offended. He had meant well; yet she had lashed at him with scornful, superior speech. He'd be damned if he'd lift another finger to help her, the snooty, overbearing——

He grinned suddenly. After all, she and he were in the same boat. Danger, the exigencies of the occasion, had brought a narrow patriotism, a pride of race, to the foreground. In the war of opposing civilizations, of strange races, culture, wisdom, calm judgments, all went by the board. Only the primitive passions remained, the bitter desire to hurt, to kill.

Warlo studied the fast, roaring bombers with inscrutable eyes. "Flying machines," he remarked finally, as if to himself, "crude in construction, inefficient, but nevertheless the product of some inventiveness. Your people, young primitive, have advanced somewhat along the road of knowledge. Well, we shall soon see."

He issued calm orders. Rone moved swiftly off. The swarming denizens of the space ship took positions at the queer, funnel-shaped machines at the ports. The metallic surface of the hull crackled with lambent fires, sheathed in blue flame.

OVERHEAD the great armada circled in a long, sweeping round. A plane detached itself from the rest, dived and came skillfully to a landing, not far from the partly submerged behemoth.

A pilot emerged, khaki-clad, pistol in hand. Behind him, covering his advance, were the snouts of machine guns. He came up to the frightening bulk of the vessel, unafraid, arrogant. Mark watched him through the transparent side port, breathless, admiring.

The aviator lifted his voice. "Hello in there, man, beast, or whatever you may be! In the name of the United States of America I order you to come forth and give an account of yourself."

Warlo asked blankly. "What did he say?"

Mark interpreted. "He is the representative of my nation," he explained. "He wishes to know who you are, and what you wish."

"Tell him," answered the Murian, "we are the new masters of his planet. If he and his fellows surrender peaceably, perhaps we may find some inconspicuous portion of this world where, in our mercy, we may grant them lodging. If they resist, we shall exterminate them all, root and branch. Speak into the metal plate."

Mark did so. He could see the violent start of the American aviator as his voice reached him through the hull, the look of amazement on his weathered face.

"I'm Mark Sloan, a prisoner in the ship," Mark said in English. "These people have voyaged from outer space, and they intend to take over Earth for themselves, and exterminate the human race. I don't know just what weapons they have, but they seem confident of their ability to do so. For Heaven's sake, radio your fleet commander to bomb us out of existence at once, without any further parleying or notice. A sudden attack may do the trick."

"Well, I'll be damned," exploded the American, moving warily back. "So that's their idea, eh? We'll blow the idiots to kingdom come. But say, how about you? You'll be killed, too."

"Don't mind me," Mark urged. "Quick! There's no time to lose. They're getting suspicious."

Outside, the flier saluted his invisible compatriot. "O.K., Mark Sloan! I'll remember the name." The aviator's hand went behind his back in surreptitious signal. Sparks crackled bluely from the plane's aerial. Then he turned, raced back to his ship, clambered in. In seconds it was zooming upward, at an angle to escape the oncoming bombs.

Mark turned to find Warlo's eyes fixed on him. There seemed a glint of amusement in them. "Young Mark Sloan," he said surprisingly, "you and your kind are not as savage and inferior as I had first thought. There are certain elements of nobility, even in your rather primitive brains."

Mark stared. "You understood what we said?" he exclaimed.

"Of course. While you slept and learned the language of Mur, I availed myself of the opportunity to learn reciprocally your halting, inadequate tongue. I wished merely to study the reactions of your people; that is why I pretended ignorance."

"It doesn't matter," Mark exulted. Through overhead transparencies he saw the massed bombers, the gaping of trip hatches, the tiny black spheres accelerating by the hundreds, straight for the huge bulk of the space ship. "In seconds you'll be wiped out, bag and baggage." In his excitement he spoke English. "Behold the end of Mur, who thought to conquer Earth."

Warlo smiled. He did not seem perturbed at the sight of those tiny globes. How could he know what powerful explosives were contained in those innocuous-seeming pellets?—Mark thought, watching in breathless fascination the onrush of the bombs. In another instant, dissolution, death, the end of everything!

CLOSER, closer! Now! Involuntarily he closed his eyes, braced himself for the annihilating roar. Nothing happened! He opened his eyes, dazed, to see Warlo's irritating smile, Banda's gaze wide on him. He looked up incredulously.

The bombs were gone. In their place, hovering over the metal skin and its lambent, sparkling fires, were little puffs of smoke. The powerful explosives had been dissipated harmlessly by the protective sheath of electrical energy.

Warlo raised his hand—and Mark swore, then cried out and

swore in mingled rage and astonishment. Shafts of golden haze

leaped from the funnels, impinged on the diving bombers—

Warlo raised his hand. The Murians at the funnels barely moved. But shafts of golden haze leaped from the funnels, impinged on the diving bombers. Mark cried out and swore in mingled rage and astonishment.

The hurtling squadron, scores on scores of huge, armored planes, shimmered an instant in the innocent-seeming haze, then vanished. Once more the sky was blue and clear overhead. But the great armada was gone, and left no trace.

"Your weapons, my young hot-head," remarked Warlo, "are a bit crude compared to those of Mur, as you may have observed. Your race has evidently not yet learned the secret of synchronized vibrations, that hurl electrons out of their energy states and scatter them in space."

"Damn you! Damn you!" Mark swore recklessly. More than a thousand of his own kind had been obliterated in that act. Rone's delicate mouth mocked him wordlessly; but Banda's gaze was full of pity and deep understanding——

IT is not the purpose of this history to detail the thronging and cataclysmic events of the next few weeks. That has been done, and better, in the learned and voluminous accounts of the historiographers.

Suffice to say that the American nation, hearing of the catastrophe from the lone surviving plane of the messenger, girded its loins grimly, and sent wave on wave of planes, tanks, heavy artillery, all the armament of modern warfare, against the invader. Nor were they alone in their unremitting efforts. The nations of the world cooperated for the first time in human history, drawn to a common brotherhood by the common menace.

But, alas, no Earthly weapon could penetrate that web of force, so fragile seeming in its shimmering tenuity, yet so unbelievably repellent against Big Bertha shells, flame throwers, reckless, suicidal tanks alike. And time and again, those thin, vaporous, golden rays darted out and wiped out, in one huge vanishment, men and guns and tanks and planes and rocks.

During all this time Mark Sloan continued a prisoner. There was no escape possible. It was a strange relationship that gradually evolved between himself and his captors, the Murians. He should have loathed them, burned with a fierce ardor for their immediate destruction. Had they not already slain huge numbers of the people of Earth? Was it not their avowed purpose to take over and repopulate the planet?

One part of his being did so respond. But there was another side, the scientist in him, yes, even the philosopher. The invaders were without doubt superior in civilization and knowledge to the Earthmen. An unwilling admiration grew on him for these Murians as he learned to know them better, as he argued and reasoned with Rone and the others.

In calm, dispassionate moments he could even understand their point of view. Put human beings in like circumstances on Mars, for instance, and they would do even as the Murians. The strange saga of their long voyagings through the universe fascinated him, the misty story of their vague point of origin stirred strange echoes within him.

They, too, from Warlo down, receded from their original contempt for Mark and his fellows to an awareness of certain potentialities in the human race.

The reckless, unremitting courage with which new armies hurled themselves to certain destruction aroused their admiration.

Finally they yielded a point to Mark's persistent arguments. They established a neutral zone of one hundred miles around their still immovable vessel. Beyond that they would harm no human for the while, provided no attempt was made to penetrate the forbidden area. It was Mark who radioed the terms of the truce to a desperate world. He bade them take courage. Perhaps, he said, he might prevail upon the invaders to——

Warlo smiled at this broadcast, but said nothing. Mark turned wearily back to the Murians to resume his interminable pleas. There was Warlo and the council, grim, tawny bearded beings, to convince. Nor did he seem to make any headway against their patient, but logically implacable reasoning. But he had two converts: Banda and her brother Rone.

They seconded his pleas, enabled him to obtain another short respite for his harried people when the first truce expired. Unfortunately, they were youngsters in the eyes of the council, and of little weight.

ONE day in council session, tired, weary of the futility of his reiterated pleadings, Mark absent-mindedly thrust his hand into his pocket, to feel something hard and jagged. Idly, without knowing what he did, he took it out, turned it over and over in his hand, while he pursued his arguments with the frozen-faced elders.

Banda's excited voice broke into the conference. "Father!" she cried sharply. "See what Mark Sloan has in his hand—your symbol of authority."

Mark, immersed in his emotions, stared stupidly up for the moment. The phlegmatic Murians had jerked to their feet, their golden faces flaming with fury. Even Banda's features were stricken, as at a sacrilege committed.

"Kill the thief! Slay the false Earthman!" Cries of rage, of passion, arose on every side.

Warlo thrust himself forward. His face was a terrible, set mask. His hand was out. "Give me that, oh viper that we have permitted to live too long," he lashed. "Almost, your cozening tongue has persuaded me, but now——"

Mark was astounded. What was the matter with the Murians? He had never seen them act this way before. "I don't understand," he stammered, unwittingly clutching the tarnished half disk in his hand. "What have I done?"

"Done!" thundered Warlo. "In your madness you have stolen the sacred disk of our ancestors, the one link we have—mutilated though it be—to that ancient Golden Age of Mur, when we were a mighty civilization, rooted to a great planet—before that ineffable day when the few escaped from the impending, unknown doom."

Mark unclutched his hand, stared at the golden, time-worn plate with its strange, un-Earth-like characters and the partial figure of a god. He had dropped it into his pocket that night while working on his thesis, and had forgotten about it since.

A great light burst upon him, so dazzling in its implications that everything else swept into oblivion. By Heavens, it must be so! Mur—Lemuria! The strange characters on the disk, the seated half god, golden, delicate of form. The strange legend of the space wanderers. It all tied up.

He rose, towered over his accusers. "Warlo," he snapped, "I have discovered your secret. It is unbelievable. This that I have is not yours; it never was. You still have your sacred emblem. Look for it and you shall see I speak true words. This is its other half, its counterpart, broken from its mate uncounted eons ago, when Mur, or Lemuria, was a mighty nation. I found this, here on Earth, on this planet. Welcome home, sons of Lemuria, to your ancient abode."

No longer were there thoughts of decorum, of position of superior to inferior. The Murians crowded around like little children. A messenger was hastily dispatched to find the sacred symbol. All through their voyagings they had clung to it, their last link with ancient glories. All other records had been lost, abandoned on the iron planet of Sirius.

When the mutilated disk was brought, and tremblingly fitted to the one that Mark possessed, there was pandemonium. For thousands of years they had wandered through the universe, knowing no home but their ship, and now fate had brought them back to the planet their remote forefathers had quitted—and it was unaccountably still intact.

MARK tried to explain that. Lemuria had lived and flourished before the ice age! It had actually sunk beneath the waves and been completely destroyed. Ice and floods and geologic convulsions all pointed to some tremendous catastrophe—a disaster that didn't quite come off, as expected. The Murians had no records to disclose its nature.

Perhaps, Mark argued, some wandering body had come from uncharted space, had swung close to the Sun and its attendant planets. Perhaps all calculations showed an ultimate crash and extinction. Something went wrong. The sidereal visitor sheered and went on its way, leaving a convulsed Earth behind, but not annihilation. Nevertheless, the remaining population of Lemuria had sunk into the ocean, and only stray fragments of their passing were left to puzzle the archaeologists.

The disk had been worshiped, no doubt, as a sacred thing. When a portion of the race cast off into the unknown, they had broken the symbol in two, so that the adventurers might also have with them the sacrosanct token, even as Greek colonists much later were to carry fire from the sacred hearth of the mother city.

"And now," queried Mark, after the excitement of discovery had died somewhat, "what do you intend to do, Warlo? Earth is the home of your ancestors, and we, its present people, are in some measure your cousins, descendants of a common stock. Surely you do not wish now to exterminate us as aliens, as the natives of a strange planet. Let me take it up with the peoples of Earth. I am certain some method can be devised for your settling on a reasonably large tract of land. Perhaps in Africa, perhaps in——" He fumbled in his mind, seeking unsettled areas.

Warlo smiled. "There are many objections. I see you are doubtful about the scheme yourself. We have been cooped up too long; we require more space for the unfolding of our culture than there is available in peace and decency on this planet.

"Furthermore, I am afraid we have awakened certain hatreds by the slaughter of Earth's peoples that could never be forgotten. And then, too, I have sensed that there is not much amicability among your own kind; that they are as ready to spring at each other's throats, as at ours. If they should ever discover the secret of our web of force and our orange ray, I am afraid much harm might be done."

"Then what will you do?" Mark demanded with a sinking heart.

Warlo looked at him gravely. "I think," he said slowly, "we shall avail ourselves of your suggestion. We take off to-night for the planet Venus. Our instruments disclose beneath its outer cloak of clouds a proper atmosphere, land and water in abundance. The Murians will have room to spread, to evoke once more the ancient glories. As for you, Mark Sloan, deliver our message to your people. They need fear us no longer. You are free to go."

A wave of exultation swept over the young archaeologist. Earth was saved, and he had been instrumental in the doing. He was free, free again!

Then he saw Banda. Her lovely, delicate face was turned to him; her eyes were pools of strange meaning.

He took a deep breath, faced Warlo and the council of elders. His voice was quiet, conversational. "With your permission I should like to join the Murians in their new venture on Venus," he said. "We can radio your message to Earth, and I, alone, possess the records of your history."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.