RGL Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

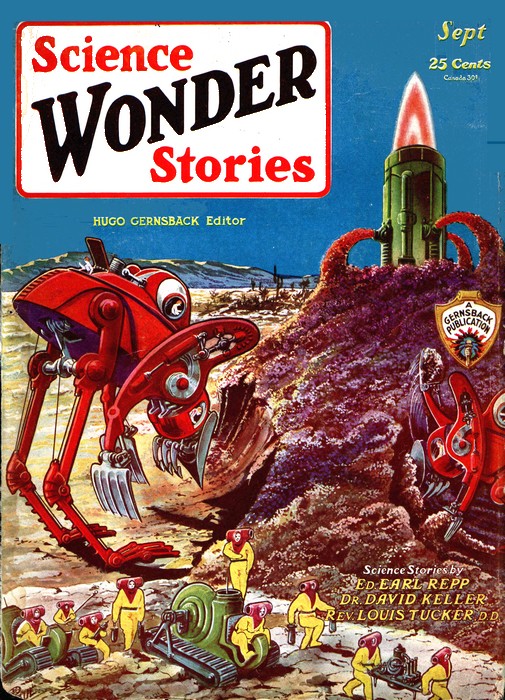

Science Wonder Stories, September 1929,

with "The Onslaught from Venus"

HERE is the versatile author of "Armaggeddon 2419 A.D." and "The Air Lords of Han," with a brand new thrilling story.

There are those authors whose chief claim to our attention is their imagination and those who in addition are inventors of no mean degree. The present author is a combination of both, and in addition, he knows how to create action stories that are difficult to match anywhere.

Mr. Phillips has a knack of inventing new instruments that are as new to literature as they are to science, and there is no denying that his scientific creations are plausible and will be duplicated when the various arts have caught up with his scientific prognostications.[*]

It is always most interesting to us to speculate on what would happen if some alien intelligence from another world—granting that it exists—would invade this planet. Many authors have tried their hand at such a theme, but few are as forceful and versatile in picturing such a conflict as is the present author.

In addition to this, he shows convincingly the importance of terrestrial conditions as they will be experienced by alien invaders.

[* The editor was right in this surmise. Two weapons predicted by Nowlan are drones (described as small helicopters a "little bigger than a cigar box") and bunker-busting bombs like those dropped by the U.S. Air Force on the Iranian underground nuclear facility at Fordow on 22.06.2025. Nowlan describes these as follows:

"Penetrative rocket-bombs were developed—great projectiles to be dropped from aircraft, which after falling a safe distance would automatically develop their rocket power and plunge earthward with acceleration and momentum many times that of gravity, to penetrate far into the ground before they exploded." —R.G.]

WHEN half the population of the planet Venus hurled itself across the void of space at our own world, believing they were going to find a new home here, I was one of the first prisoners they took. As a matter of fact, I fell into their hands before one of them had set foot on Earth, when their first "bulb" was still 18,000 feet above it. It was a cloud bank that proved my undoing.

We of the Air Guard had had our warning, but were uncertain as to what to expect. The observatories of the Rockies, Alps, Andes and Himalayas had noted the mysterious objects bursting out of the cloud envelope of Venus, on orbits obviously calculated to bring them within the Earth's gravitational influence.

There could be no question but that some human-like intelligence was back of the mystery. The observatories flashed their warnings to the Central Astronomical Board, which in turn reported to the Supernational Commission of the Caucasian League, in Geneva.

But the board went astray in its interpretation of the phenomena. Its theory was that the several thousand hurtling bulbs or spheres photographed by the observatories were projectiles containing explosives or some other agency of destruction. Actually they housed front 400 to 2,000 men of Venus apiece, fleeing their planet. They were trying to escape annihilation by volcanic forces that had gotten out of control after several centuries of increasingly ambitious use.

About half the population of Venus lacked the courage to face the terrors of interplanetary space in a desperate gamble for continued existence. Presumably they perished in the Doomsday which followed, and which was visible to our observatories as terrific disturbances and upheavals in the Venusian cloud envelope.

Of the other half, who exchanged their few remaining weeks of existence on Venus for the desperate chance of hitting a pinpoint in space, and finding it habitable after hitting it, relatively few reached the Earth. Had a majority done so I question whether we could have withstood them so successfully, with their terrible weapons.

We would have overwhelmed them by sheer numbers in any event, of course, but men would have died by the hundreds of millions and the rest of us would have returned to the dark ages if we had not been able to overcome them before they deranged that delicate balance of production, commerce, finance and social structure that we call civilization.

From what I learned as a prisoner, our astronomers actually discovered only fifteen or twenty percent of the total number of "bulbs" launched. Altogether more than 47,000 of them were hurled toward the Earth, carrying about 45,000,000 Venusians (the total population of their planet being only slightly over 100,000,000.)

Only 1,600 of these "bulbs," with "crews" aggregating 1,400,000 actually reached Earth. Thousands of them were shattered by collisions with meteoric bodies. Thousands more were deflected from their course by unforeseen gravitational influences exerted on them and they hurtled on into space past the Earth. Still other thousands were estimated by the invaders themselves to have missed the target through errors in calculation, and the imperfection of hurriedly constructed space "guns."

But to begin at the beginning, I was patrolling the air lanes above Northern Mexico, about a hundred miles south of the Texas line, with "Tubby" Baines handling the radio and telescopes, while "Eggy" Morris sat at the guns of our Randall. This was then the newest type of plane in the Air Guard, a ship of remarkable balance and steadiness for those days, with an easily sustainable speed of 300 miles an hour, and a cruising radius of 6,500 miles.

As far as the eye could reach, and the scopes too, for that matter, the air was filled with patrol ships, each circling the territory of its beat and waiting for we knew not exactly what.

The "bulbs" were due to arrive at any time now. From one end of the continent to the other, and throughout Europe, the Supernational League's Red Cross Division had been mobilizing relief organizations. City populations had been ordered to scatter temporarily into the open. It would not do to have one of these bulbs hit closely-massed millions, if they were explosive.

Our orders in the Air Guard were indefinite. We were to patrol, watch, report and stand by for further orders. We were to spot any hits of the interplanetary projectiles, so that relief might be rushed to points needed with the least delay. We were all at a pretty high tension.

Far above us, to the South, was a big cloud bank, and it was in the middle of the afternoon that Tubby sang out to me the general order he had just picked up. All Randalls were to rise out of position, and head South a hundred miles at whatever level was necessary to carry us above the cloud blanket. Observations, it seems, indicated that most of the oncoming bulbs were falling toward the Tropics.

I nosed upward in a long easy slant that took us into the cloud bank. Once in it we could not see forty feet ahead, but I kept the Randall rising at full throttle, for I knew there would be no other plane within miles at this level.

I CAN'T tell just how it all happened—it took place so rapidly—but I was conscious that our plane was entangled in a vast mass of billowing, canvas-like material. It closed around us in overwhelming folds as we buried ourselves in it and brought up with a sickening lurch.

Tubby's face bore an expression of ludicrous surprise as he spread-eagled over my shoulder, sailed over the rail, and disappeared, scratching desperately for a hand-hold as he slid down a trough in the billowing fabric. That was the last I ever saw of him.

I have no recollection at all of what happened to Eggy. I never saw him again.

For a moment I clung to the rail as the Randall slowly turned over. Then I lost my hold, and slid with increasing momentum down one of the folds of that vast enveloping fabric—a human insect, lost in a chaos of drifting canvas 20,000 feet above the Earth.

My hand touched a rope. I held desperately to it, and found it with my other hand. A short distance below me in the fog I heard a crash, evidently the Randall colliding with something bulky and metallic. Then silence.

Gradually the sea of canvas straightened out. I knew then that I was clinging to the edge of a vast parachute. But my whole mind was centered on self-preservation. I had no time to wonder. I went down the rope hand under hand, until below me in the mist loomed a section of a great metal dome. With my feet planted on this more substantial support I paused to regain my breath and gather myself together.

It did not yet occur to me that I had found one of the interplanetary bulbs. Like everyone else, I had it set in my mind that these would turn out to be explosive projectiles. Moreover I was completely dazed with the suddenness of it all.

Mistily, the metal dome curved downward in one direction. In the other I saw a railing a few feet away. I threw myself toward it and climbed over with a sigh of relief. The whole structure was swaying sluggishly, and was sinking, I was sure. But it had not fallen below the cloud as yet.

Then a hatch nearby flipped open.

Three men climbed hastily out. They were clad in what looked like divers' suits, covering them from shoulder to foot; and over their heads were large goggled helmets.

My surprise evidently was equalled by their own, for they paused to survey me amazedly through their big goggles. Then one of them signalled the others, and all three of them leaped upon me like wildcats. Taken utterly by surprise, I went down under their rush. I was hustled down through the hatch, which clanged over my head, and literally rushed down a corridor into a compartment that looked like a combination of control-room and engine-room on one of our own big dirigibles.

The ship, for now I knew I was aboard some sort of strange aircraft, was crowded. My captors had to fight their way down the corridor with me. Some of the crew through whom they pushed were clothed in "divers'" suits and goggled helmets like themselves. Others wore sleeveless, belted tunics that reached the knees, and they looked to me as though they had emerged from flour barrels. Their skins were dead white, as white as Grecian statues. But their eyes were yellow and their close-cropped hair a tawny orange.

In the center of the control room was a big instrument table, at which a marble-white man sat, surrounded by illuminated screens upon which appeared shifting pictures. Occasionally he would reach over and twist a lever, or flip a switch. My captors stood respectfully waiting for his attention. Finally he looked up and stared at me with piercing yellow eyes that looked out from a finely chiselled face that might indeed have been marble from its total lack of color.

But he had little time for me then. He waved his hand and turned back to his instruments. My captors hustled me off to a little compartment, where I was locked in.

Later came a slight jar. The ship had come to rest on the ground. There was a clanging of doors, and rushing of feet, a babel of voices and harsh commands; and the sound of heavy machinery being hauled around.

My captors re-appeared, and literally dragged me down a spiral companionway to the lower decks of the ship, and thence into the bright light of day.

I LOOKED around in amazement. I had emerged from a great metal sphere about 600 feet in diameter. Around me was the greatest activity. Some fifteen hundred helmeted figures had spread out over the plain. Split up into disciplined groups, they were busily setting up what appeared to be numerous searchlights and squat, broad-mouthed anti-aircraft guns of complicated design.

In the sky above gathered a host of planes of our Air Guard, circling around, puzzled by what they saw below. Had they only dropped their bombs then, much bloodshed among our own people could have been avoided, but quite naturally in this day of civilization, they did no such thing.

They had reported to Washington and had received orders to make friendly overtures to the strange newcomers. One of the planes dropped below the formation and began to spiral down.

A few feet away from me one of the squat guns coughed. A blinding flash appeared some fifty feet away from the circling plane, which was irresistibly sucked into it. There was a miniature thunder-clap, and the twisted, incandescent wreckage of the plane dropped like a stone.

Another gun coughed hollowly, and another blinding glare of light appeared, this time in the middle of the formation above. It sucked in three planes; and their broken, twisted remains also plunged earthward.

Then our planes dived, their motors roaring. There was a sudden consternation among the white-skinned men around me. Guns coughed frantically. Hastily-aimed bombs flashed, blinding even when seen against the bright sky. Two more planes collapsed, but the rest dived on.

More guns coughed. The attention of my guards diverted for the moment, I hurled myself headlong toward the nearest gun, whose crew was about to discharge it. I caught the feet of the creature whose hand was reaching out toward the firing mechanism, upset him, and rolled instantly to my feet, tugging at the automatic in the holster on my thigh. I got it out in time to fire point blank at another who leaped at me. He reeled, and I noticed as he went down that though the skins of these strange people were white, their blood was red enough.

I took toll of seven before they finally pinned me down, and my little diversion at least kept one of their guns out of action while the planes sprayed the groups of soldiers with a leaden hail, cutting them down by the score. Then the planes zoomed again to comparative safety.

By now, however, the invaders' machines that looked like searchlights got into action. They spread fan-like beams of iridescence overhead. These beams the operators quickly wove into an interlocking network, making virtually a continuous cone of pulsing light, its base the circle on which the machines had been set up, and its apex about a thousand feet in the air.

The planes of the Air Guard returned to the attack, this time dropping bombs as they passed overhead. I broke into a cold sweat. I knew the power of those bombs, and figured my life in terms of split seconds.

Then an amazing thing happened. The downrushing bombs bounced off the cone-curtain of light as though from an invisible rubber wall, and exploded harmlessly. Not even the fragments showered around, for these too bounced off in their turn. But the invaders were close to panic from the ear-splitting force of the explosions, and they manipulated their coughing guns in very ragged fashion.

Through the uproar their leaders rushed about angrily, beating them back to the posts they had abandoned. I saw more than one of them strike down a man with his short, heavy sword.

Not until the Air Guard planes had expended all their ammunition did they withdraw to the 10,000 foot level, where again they circled watchfully.

Altogether seven planes of the Air Guard had been shot down. About three hundred of the men of Venus lay killed and wounded within the circle. All these casualties, however, had been suffered prior to the formation of the protecting light-cone which had thrown off bombs and bullets alike, rendering the second attack of our planes quite futile, although seemingly terrific.

INTENSE activity on the part of the invaders followed the withdrawal of the Air Guard squadron. A vast mass of machinery was removed from the sphere, which actually was taken apart in the process. Its plates and beams had been cleverly designed as interchangeable parts of other machines and constructive apparatus. Quickly interchangeable at that. I don't think it took more than an hour or so for the thousand men of Venus who were not casualties, or assigned to the task of ministering to the wounded, to completely demolish the great bulb in which they had arrived on Earth.

In its place there arose giant cranes and complicated machines which began to dig and handle materials in huge masses, with uncanny skill and accuracy.

In the center of the circle was erected a cylindrical apparatus, which proved to be a boring machine. By some complicated process that was beyond my comprehension it began to dig a great well, the displaced earth literally flowing from openings in the side of the thing. As the mound of earth grew around it, the cylinder automatically rose in the center of this mound.

Other machines which squatted like huge metallic insects, occasionally raising themselves on leglike levers to change their positions, reached out with great extension arms that terminated in universal-jointed paddles or "hands," each probably fifteen feet across, and scooped vast quantities of the earth toward the outer part of the mound.

Before long the removed earth assumed the proportions of a hill. The circular battery of fan-ray machines was moved outward, the number of machines being augmented by constantly assembled additions.

Then I noticed that the character of the earth flowing from the boring machine was changing. In a few minutes molten lava was pouring out of the broad-lipped spouts. There ensued unusual activity on the part of the shovel-handed machines, whose operators, with a skill that held me enthralled, manipulated the liquid stone, absorbing the heat from it with accessory apparatus, and shaping it as it hardened.

Night fell, and the glow of the lava lighted the scene weirdly, tinting the dead-white bodies of the invaders. By now they were mostly stripped. With the setting of the sun they had begun to remove their protective diver-like suits and goggled helmets, and for the most part were clad only in full-cut short trousers, not unlike kilts, that extended in pleats from highly ornamented, broad belts to a point several inches above the knee.

There were many women among them. In fact, about a third of them were women, but there was no distinction between their dress, or lack of it, and that of the men. Both men and women wore their tawny yellow hair close-cropped. Nor did there seem to be any division of labor among them that was based on sex. All were working under high pressure at various machines, except the executives, those who were tending the wounded, and the three guards who never let me get beyond their reach. They permitted me free movement, however, within the confines of the circle so long as I did not approach any of the machines too closely, or get in the way of the bustling parties.

That more would be heard from our planes that night I know well. The traditions of the Air Guard, particularly the American Division, did not embrace much consideration of the principle of watchful waiting.

I had just looked at my watch—it was nine o'clock—when something white, a little weighted parachute floated down right through the cone of the fan-rays, which spread a faint iridescence through the air above us. A white-bodied girl approached it hesitatingly, inspected it where it lay, and at last reassured, picked it up and ran with it to the commander.

I knew what it was; a note, an ultimatum, offering truce or war to the invaders. When the commander looked casually at it, handed it back, and with a word waved the girl away, I had a pretty good idea of what would follow. The Air Guard would be watching through their night scopes, and probably would get a good view of his action, for he was standing well in the open, and in the glow of the lava.

A moan from above swelled into a roar. My heart skipped a beat. It was one of those two-ton inflammite bombs. The bombs dropped previously were as pills by comparison. That it would burst through that inverse magnetic film of the fan-rays by sheer momentum, I had no doubt.

But it didn't. With a horrible whooping shriek, it rebounded to one side and detonated two or three hundred feet away, the shriek and the stunning detonation blending in a vast ear-splitting sound.

The fan-ray film threw off the big steel "can" and its fragments, but it offered no resistance to the force of the explosion. The people of Venus nearest that side of the circle were literally blown from their feet, and lay mangled and bleeding.

There followed a period of silence no less stunning than the explosion. Then the invaders leaped to work. Under snarling, barking commands of their leaders they rushed to replace several of the fan-ray machines that had been blown from their mounts, while the operators of the remainder raised the angles of their beams to make the cone as large as possible.

Fluttering and swinging down through the film came another little parachute message. Their commander did not have to know any Earth language to grasp its meaning. But he did not seem to. Or if he did, no other course than ignoring it entered into his calculations. Again he waved aside the bearer of the message angrily.

The invaders once more were near panic, but their discipline held. Suits and helmets were donned hastily. The coughing guns were manned, and began to hurl their queer suction bombs upward into the black night. These projectiles, I noticed, passed freely through the fan-ray film.

AROUND the circle machines were hastily manned to drive diagonal wells into the ground. In these the ray machines were placed for safety. The work that was accomplished in the next ten minutes was astounding. The men of Venus were almost ready for the heavy bombardment when it broke, and their suction bombs were flashing with blinding rapidity against the dark sky above. I could well imagine that our Air Guard were having no picnic with them. Their flashing would have served to half blind a pilot.

Then "hell" dropped from "heaven." One by one, at intervals of less than a second the two-ton bombs fell. They were thrown off at various angles from the cone film, but being set for contact detonation did not rebound to great distances.

I threw myself to the ground, with my arms wrapped around my head, and lay there half-stunned. I lost consciousness at the expiration of a short interval, I don't know how long it was before I came to. But as I staggered to my feet, those about me were doing the same. There was no indication of our planes overhead, and the faint iridescence of the cone film was unbroken. Many of the machines sprawled about, overturned and wrecked. And at several spots within the circle I could see parts of our planes which evidently had been wrecked by the coughing guns. Fully half the original fifteen hundred invaders were now casualties. But the remainder tirelessly took up the task of repairing the damage and carrying on their construction work. And such wonders did they accomplish with their strange machinery that dawn rose on a terraced, castle-like structure of solid and cooled lava, circular, about a thousand feet across, and rising to a squat tower in the center, the top of which was some two hundred feet above the level of the plain. An encircling ring of fan-ray machines, buried deeply in a diagonally-cut trench, spread their cone-shaped, faintly visible protection above the structure, and far enough away from it to render the explosion even of such bombs as had been hurled during the night relatively harmless.

I was dragged within this fortress, and locked in a bare cell, from which I had a restricted view through a narrow porthole facing the north.

Within my range of vision a few sentries covered from head to foot in their peculiar suits, patrolled the terraces, pausing now and again to gaze through instruments that looked like complicated reflex telescopes mounted on tripods. But the main body must have been within the walls, sleeping off their exhaustion, for aside from the sentries I saw no one. Exhausted myself, I dropped to the hard floor and fell asleep.

A GREAT deal of history was made in the two months I was held prisoner. But I learned little until afterward of the manner in which the invaders, who had peppered the world with colonies similar to the one in which I was incarcerated, finally consolidated their strength in the tropical sections of Central and South America.

Most of their "bulbs" had descended about a thousand miles north or south of the Equator. Several had landed in the United States. Some of these had been overwhelmed at once, when their crews showed fight, and before they could assemble and bring into action their fan-ray machines or their coughing guns and suction bombs. Others had managed for several days to stave off the Air Guard and Land Guard cordons which closed around them. One had held out as long as two weeks.

Once their fan rays were in operation they were most difficult to subdue. In each case where the Air Guard did not succeed in annihilating them at the outset with inflammite "pills," they finally had to be overpowered by massed infantry attacks.

In these attacks our Guard suffered tremendous losses, for as they passed through the fan-ray zones their rifles and side arms were wrenched from their grasp by the repelling effect of the inverse magnetic forces. The men were forced to cast aside all equipment containing metal of any description, and to meet the soldiers of Venus with bare hands, rocks, and such hastily-improvised clubs as they could get a hold of as they advanced; whereas the planetary invaders, already safe behind their magnetic film, were not handicapped in the use of metal weapons, and their deadly vacuum grenades.

The European divisions of the Caucasian Federation were not, on the whole, so successful as the American in coping with the invaders, while in Asia, and other parts of the world, the invaders had things pretty much their own way.

Later, as they assembled their aircraft, and got their earthly bearings better, they abandoned their outlying lava forts, and mobilised in the tropical regions of the Western Hemisphere, where the weather conditions were more suited to them, and where they achieved such concentration of forces that the most powerful of the hastily organized attacks of the American Air Guard, reinforced from Europe, were decisively repulsed.

Then ensued that lull in hostilities that preceded the final conflict.

But all this is a matter of general history, whereas this account is primarily concerned with my own experiences.

THE first week of my incarceration was rather dull. My jailer was a middle aged man of abnormal cerebral development. Most of the food he brought me turned my stomach; filthy messes of partially decomposed animal and vegetable matter. There were certain vital physiological differences between the men of Venus and those of Earth, and, as a matter of fact, the fare that was brought me was in full conformity with their standards of wholesomeness and palatability.

My jailer pestered me continuously, forcing me to utter the names of everything he could point out to me or show me pictures of. They had some very clever photographic process that enabled them to take telescopic pictures of great clarity and accuracy.

From the names of objects, he probed me for words denoting action, and so on, until much to my surprise, at the end of no less than a month, he addressed me one day in halting, but unmistakable English.

"Your speech has been very hard to learn," he informed me, "because it is so involved, and much less direct than ours; though it has the advantage that you have fewer words to remember."

This was the gist of his speech. I don't remember the exact words he used, except that they were very funny, and also very ingenious in the association of ideas through which he made his meaning clear.

But after this he did not bring my food any more. Instead a young girl was assigned to the task. She informed me haltingly that she was learning my speech.

"Let me teach you," I suggested. She smiled at this, but shook her head negatively.

"I can learn more quickly from the miorurlia," she said.

And at the end of another week she was speaking better English than the man had.

She told me I was considered something of a prize, for though their colonies had captured several thousand Earth men, most of them had rated low in intelligence, and they had only two or three altogether who spoke English.

Her name, she said, was Nyimeurnior. She quizzed me untiringly about life on the Earth, and since her questions covered the entire range of engineering, medicine, sociology, history, commerce and industry, as well as political economy, I was rather hard put to give satisfactory answers. But in turn she freely discussed her own race with me.

She found it difficult to understand why the food they had been giving me was nauseating to me, and this led to a long discussion of many physiological differences between Earth men and the men of Venus. That there were such differences I was not unprepared to learn, since there were such differences in physical appearance.

On the whole, the invaders were a trifle smaller of stature and bigger of head than ourselves. Their foreheads were higher, their eyes a bit larger, and their noses, mouths and chins, though regular and beautifully molded, a bit smaller in proportion. At that, however, I have seen Earth men who could have passed for these people, were it not for the difference of coloring.

They were as dead-white as marble statues, except for tawny yellow eyes and hair. And I might mention that they had no hair anywhere upon their bodies except upon their heads, where it grew thickly. Both men and women wore it cropped very short. This dead-white skin of theirs was thicker than ours, but was also very soft, and normally should have been moist, not from perspiration, but from the absorption of moisture from the air. This absorption rather than excretion appeared to be the principal function of their pores.

They could, of course, and actually did, drink a great deal of water during their life on Earth, but the sensation was very unpleasant to them, and they drank only of necessity, because their pores could not absorb from the relatively dry atmosphere of the Earth the amount of water they needed.

THEY needed considerably more heat, also, than our climate furnished anywhere except in the tropics. This was the reason for their decision to withdraw those colonies which, like the one in which I was held prisoner, were located in more temperate regions. It was also the reason why they contemplated no immediate conquest of the Earth, but planned to remain on the defensive in their tropic strongholds until such time as they might better adapt themselves to Earthly conditions, and increase their numbers. In the meantime, however, it was their intention. Nyimeurnior told me, to keep the Earth men busy with destructive air raids.

They had anticipated finding the Earth's atmosphere different from their own, of course, and knowing that it would be considerably drier had equipped themselves with waterproof suits which covered them from, head to foot.

These suits served the purpose of humidors. They were also an absolute essential as a protection from the Earthly daylight. Our atmosphere, lacking the fog filters of that of Venus, lets through certain rays of the sun which, though almost a necessity of life to Earth beings, are rank poison to Venus animal and plant life.

"Does the sunlight never break through the cloud layers of Venus?" I asked Nyimeurnior.

"Not ever," she replied, quaintly. "Our daylight is very bright, and very warm, because Venus is so much closer to the Sun than Earth. But the air is very full of water, like the fog you tell me you have in other parts of Earth, and like these clouds that sometimes pass above us here, and it is never you are able to see for greater distances than what you call a quarter of a mile. Before we came to Earth we knew sunlight only from sending—what do you say?—scientific expeditions up through the clouds many, many—that is, a very great distance."

Exposure to sunlight, even for a very short time, was deadly to the people of Venus. I had occasion to observe this for myself later. It did not burn them in the way that over-exposure does Earth men, for they had no pigmentation in their skins whatever. But it did pull the blood right out through the pores, so that after a time they became horrible spectacles. But even more deadly than this was its toxic effect upon them. It deranged their nervous systems, and stimulated them to a hysterical fever, which was quickly followed by a torpor and, if relief measures were not applied promptly, by death.

A half an hour unprotected from the rays of the sun would turn the hardiest man of Venus into a dried-out, blood-caked corpse. An hour or two hours in normal daylight, out of the direct rays of the sun would do the same, though they suffered little discomfort in going abroad when it was storming or the skies were heavily overcast.

Naturally they were not happy in the Earth atmosphere. Nyimeurnior told me that they wore very little clothing on Venus, and hated the feel of the humidor suits they were forced to wear out of doors in the daytime on Earth. But there was no help for that. They simply kept under cover all they could during the day, in their artificially humidified structures, adopting a schedule of night work. But even at this, the chill of the night outdoors was playing havoc with the health of the community, and before many more days, she informed me, they would abandon the lava fort, and migrate in the airships they had built since my incarceration to the city which other communities were even now completing in the fastnesses of the tropical forests of Brazil.

"I cannot understand, Nyimeurnior," I said one day, "why your people refused all overtures of peace. Our Earth nations are not bloodthirsty. We do not kill for the sake of killing. There have been many wars in the past, owing to the fact that men cannot always agree on everything, but in the main Earth men live at peace with one another, and I know they would be willing to live at peace with your people if you would show the right spirit. There is much in which we could help you, much that we could teach you; as there is much that we could learn from you. It would be to the mutual advantage of both races."

The girl looked at me queerly. Her pretty little mouth closed in a grim line. She made no reply whatever, but arose and left my cell immediately, evidently in anger.

I never thoroughly understood this attitude on their part; nor have I ever heard that any one else ever did. During the time I was prisoner I tried to suggest the idea of a truce to their leaders as frequently as I could. But it seemed as though their consciousness was utterly and mysteriously barred to its consideration. The only reply I ever got was a blow in the face, or a look betokening a suspicion that I was mentally unbalanced. Don't ask me why. I can't explain it. But certain it is that, from the day the first bulb fell into our atmosphere until that final day when our armies, millions strong, surged irresistibly through the Brazilian forests, not once did they make an overture of peace, or indicate, that they would accept any mercy from us. They simply could not grasp the idea, that was all.

For several days after I made this suggestion to Nyimeurnior she would not speak to me. She brought my food (healthful Earth food now, not the sickly messes they had given me at first), and left as quickly as possible. It was as though I had offered her some gross personal insult that had filled her with a loathing of me.

THIS didn't bother me much, however. To those who had any personal contact with the invaders, I don't have to explain why. But, for the benefit of those who never saw one at close range, I might say that though I found the girl interesting, and though I could even go so far as to refer to her as "pretty," anything like a romantic interest in her was an utter impossibility.

Imagine, if you can, being in love with a girl with a dead-white, moist, clammy skin, like the belly of a scaleless fish, bloodless lips, and smoky, yellow eyes that somehow reminded you of those of a cat, although the shape of the eyelids was human enough.

No. Nyimeurnior's attitude did not disturb my emotions in the least, though it piqued my curiosity greatly.

Gradually, however, she appeared to forget the "insult." Her interest in information about the Earth served to renew our conversations. Perhaps she was ordered to resume them.

She told me about their airships, mushroom-like affairs in which the space for the crew and cargo corresponded with the stern, and the elevating machinery is built into the umbrella-like superstructure. They could rise in a straight vertical line, like helicopters, move slowly and gently, or hover motionless. Speedy aircraft, she explained, would be suicidal in the fogs of Venus.

I was amazed at her description of the manner in which they were supported. Air on the upper surface of the "umbrella" was destroyed by electronic action, thus forming an up-sucking vacuum. It was "recreated" electronically on the under surface of the umbrella, thus forming a supporting cushion of compressed air which, though constantly dissipating, was being replenished with equal rapidity. It was only necessary to vary the speed of the process to rise or fall. Automatic compensators constantly adjusted the vacuum and pressure at various points on the umbrella surface, always keeping the ship in perfect balance. If anything went wrong with the electronic apparatus the ship merely came down like an ordinary parachute. Horizontal propellers furnished motive power.

With the clear air of Earth through which to fly, she said, their engineers were increasing the ratio of motive power, and her own community had succeeded in obtaining a speed of 130 miles an hour with its ships. This was less than half the speed of our Air Guard patrol planes, and less than three-quarters that of our bombers.

"We are saving you to teach us about planes," Nyimeurnior said.

"Saving me from what?" I asked.

She looked at me in surprise. "From death, of course," she replied. "Why should we be wasting food and trouble on you if we could not make use of you?"

"Would you not spare my life from motives of mercy?" I asked.

"'Mercy?'" she repeated questioningly in her peculiar pronunciation, "that is a word we have not spoken of before. What does it mean?"

I tried to explain to her, but quite unsuccessfully. The best she could make of the idea of sparing an enemy of whom no profitable use could be made was that it was a manifestation of ignorance or insanity. I began to realize that these people had no conception of charity, sympathy or kindness as spontaneous emotions, although they approximated the practical manifestations of the emotions from a motivation of expediency.

I delved further, and found that they were unfamiliar with love, except as an intellectually selfish emotion. A husband was kind to his wife, for instance, because he needed her help and cooperation, and realized that she could give this more efficiently under the influence of consideration and comforts than with a mind or body deranged by harsh treatment. If she lost her usefulness to him he put her away on a sort of pension arrangement. He did not kill her because that would make other women fear him, and he might have difficulty in getting another wife. On the other hand a wife was helpful and considerate of her husband because she realized it was to her interest to cooperate fully with him.

And naturally, the most kind and considerate of the young men and young women were in the greatest demand as husbands and wives.

But back of all their courtesy and consideration was nothing but an acutely developed self interest, tied up with a peculiarly keen appreciation of the values of cooperation, and an ability to weigh and balance those values, undisturbed by emotion, far in advance of any similar ability on the part of Earth men.

They had only one true emotion—physical fear. They were very susceptible to it. As compensation they had a high order of intellectual courage. The fact that they had risked a journey through space attested that. But their physical susceptibility to fear in moments of emergency was a far greater handicap to their balance and judgment than is the case with the average of Earth men. Fear tended to paralyze rather than stimulate them to action. Intellectually they steeled themselves from early childhood against this weakness, but with only partial success.

It was quite plain to me as a result of this partial insight into their psychology gained from Nyimeurnior, that I had my choice of ultimate death, or playing traitor to my country, my world and my fellow man by teaching them to make and fly airplanes.

For strange as it may seem at first thought, Earth men, despite the comparative newness of their mechanical civilization, held an advantage in the air, from a military point of view, with their swift, darting planes; though it may be conceded that for general convenience and comfort the Venus "umbrella ship" was superior.

Having developed their navigation of the air along totally different lines for centuries, the newcomers had nothing more than an elementary grasp of the principles underlying the construction and use of planes.

I HAD no intention however, of either turning traitor or sacrificing my life. So I began to maneuver for a chance at freedom. Not long after I had come to this conclusion I was take before the Nyapacleur or commander of the community, whose position, with allowance made for the highly organized and mechanically perfected civilization of Venus, was not unlike that of a feudal baron. That is to say, he held the power of life and death over the entire community. The members, according to the Venus theory, owed all their necessities and comforts, as well as their very lives, to the skill and strength of his leadership. They, in turn owed those lives to him if ever he should choose to call for them.

This Nyapacleur's name was Lourmon. He was the same before whom I had been taken for a brief instant in the sphere which had brought the community from Venus. Nyimeurnior and my first jailer, whose name I learned was Founyi, acted as interpreters.

The room in which he gave me audience was not unlike an office. He sat at a kind of desk, on which, however, the usual mass of papers was replaced by a number of mechanical contrivances which I judged were various forms of recording and reporting devices.

The air in the room was warm, and highly humid. Lourmon, naked except for the peculiar belt and shorts the invaders wore, and a kind of sandal, was such an incongruous figure, from my Earthly point of view, that I could not help smiling. Imagine, if you can, a near-Grecian statue come to life and leaning carelessly over a table piled with modern scientific instruments.

He glanced at me keenly, and spoke a few words in that soft, slurring tongue of theirs which was a form of language which no race on Earth has yet developed except for purposes of writing. By that I mean that it was not the original or natural speech of these people, but a species of "shorthand," through which entire sentences and paragraphs might be summed up in a single word, or two or three words. One of my great regrets is that I had so little opportunity to learn it.

These few words Founyi translated into nearly five minutes of his slow English, reviewing in detail the account of my capture, referring more briefly to the journey of the invaders through space and the reasons which led them to attempt it, outlining their determination and confidence in their ability to exterminate Earth men and take over the world for themselves, and setting forth my individual helplessness and the wisdom of endeavoring to make myself a useful slave if I desired to preserve my life.

While Founyi was translating, Lourmon, clearly impatient at the handicaps of such a slow and clumsy language, was abstractedly manipulating the levers of a little apparatus which was presenting to him a series of pictures on a little translucent screen. At the end of Founyi's speech he looked questioningly at me, as though taking my consent for granted.

I had decided to appear to agree, for only in such a source could I see any possibility of being permitted enough freedom of movement to plan for my escape. But I did not want to seem to give in too readily. It would be more convincing, I thought, if I were persuaded only reluctantly, after more elaborate threats and promises. In this, however, I made a blunder.

Lourmon leaped to his feet in a rage when I did not instantly agree.

"M'yarrip!" He fairly snarled the word at me.

"He says," Nyimeurnior explained calmly, "that you are a fool, but that since you are only an Earth man he will give you one more chance to think it over and make better use of what little intelligence you have. He does this, not from any motive of 'mercy' or justice to you, for as a prisoner you are not entitled to any rights or claims whatever, but on the contrary are indebted to him already for several weeks' existence. He does it merely because he needs information you can give him, and he is willing to sacrifice even his dignity on the chance that you will ultimately give it to him freely. But this sacrifice of dignity in not ordering your execution immediately he will hold against you as a debt. If you do not change your mind you will be tortured, and the secrets of the Earth airplanes dragged from you!"

I was so amazed at the volume of meaning the girl translated from the Nyapacleur's single word, that I forgot to play my role, and instead of consenting at once, stood there with an open mouth, like the fool Lourmon had called me, trying to figure out how much language actually had been packed into two syllables, and how much was, so to speak, "embroidery", added to it by the girl from her knowledge of the situation.

Lourmon made a vicious little gesture, and my two interpreters led me back to my cell.

"You're not such a low mentality as he believes you," the girl remarked. "Unless I too have misjudged you, you will accept. If you decide to before the next mealtime, just knock on the paneL The guard outside will be instructed to take you to Lourmon, who will not need any speech from you but just a sign of assent." With that she stepped from my cell to the corridor and shot the panel across.

THIS arrangement, I thought, would give me my opportunity. I glanced through the tiny window of my cell. A brilliant morning sun flooded the half mile or so of bare plain and the rugged, rocky country beyond. Why should I wait to build up little by little any elaborate plan of gaining more and more freedom of movement within the "castle" until finally I could make an opportunity of escape? It would be better to risk all on a bold stroke.

After the first day the sentries had given up patrolling the open terraces in the daytime, even in their cleverly constructed humidor suits. Two of them had died from it. Instead, I had been informed by Nyimeurnior, they were safely ensconced in little turrets, which they could enter only from within the fortress, and from these they scanned the sky with their telescopic instruments, carefully shielded with ray filters, for signs of the Earth men's airplanes, turning their attention occasionally to the rough country surrounding the little plain on which the fortress was located.

Once I got clear in the open sunlight, the invaders would certainly find it difficult to pursue me. My danger would be chiefly that they might launch an umbrella ship after me.

Indecision is not a frequent fault among us of the Air Guard. I rapped on the door at once, hoping that my guard would be a big fellow for his race, and be wearing his humidor suit.

Footsteps approached, and the panel swung back. He thrust his head in the cell and beckoned me to follow him.

I seized and jerked him into the room. It would have been easy to knock him out with a blow on the jaw if it had not been for his helmet. But I finally managed to knock this off as we scuffled and then a few well directed blows put him out.

I stripped the fellow of his humidor suit. Luck was with me, for though he was not as large as I, his suit was a bit large for him, and with some difficulty I was able to squeeze into it. Placing the helmet over my head, I belted on his weapons, which consisted of a short sword and a couple of what I took to be small vacuum grenades. Then I stepped boldly through the panel door into the passageway. Nobody was in sight.

From a distance, some place below, there came to me through the network of corridors and up the ramps which was used in place of stairs, the sounds of a large body of men marching. Gradually this sound lessened, and since at the same time I heard a confused clamor through the outlet ventilators, I judged that a detail of men had been sent outside the castle.

This was strange, for it was broad daylight, and the sun was shining brightly. I knew that something important must be afoot to take the soldiers of Venus out into the sun, even with the protection of their humidor suits and helmets. After some search through the deserted upper levels of the structure, I found a lookout turret from which I could get a good view of the surrounding plain.

It was a typical view of that section of Mexico; a broad plain quivering in the sunlight, for the most part arid and bare, but with occasional islands of rocky protuberances and patches of poverty-stricken mesquite.

Far to the West, at a point which was practically the limit of my vision, I saw another of the lava fortresses. The sky above it was filled with little flashes of light, and puffs of smoke, indicating that an attack was being made upon it. As I gazed a giant dirigible of the Air Guard, in its low-visibility war paint, swung broadside on to my line of vision, materializing, as it were, out of an empty sky.

There followed a series of detonations so heavy that I could actually feel the air vibrate. But apparently not even these heavy bombs could break through the fan-ray film which the invaders had spread above themselves. The little flashes and smoke puffs continued both aloft and below.

I glanced downward at the gate of the fortress, which I might mention here was not unlike that of a medieval castle, if you can imagine one of those old European fortresses done over again in modern factory construction style.

A column of soldiers had issued forth, and was winding its way across the plain in the direction of the beleaguered fortress. But what interested me most keenly about the column was the method used of protecting it from air attack. In the center marched a column of infantry. To either side of them a column of fan-ray machines, which lumbered along on lever-like legs, with a motion not unlike the lurching of our own tanks, their generators all turned outward, spreading a fan of rays, almost horizontal, over the tops of still two other flanking columns of machines. These outside columns played their rays upward and inward over the center of the column, the two films of rays crossing and furnishing complete protection.

The only way in which that column could be reached by steel projectiles of any description was from the ground, at flat trajectory.

So interested did I become in the attack on the column which I was certain would follow, that I forgot the pressing need of making my escape, and stood there gazing.

From somewhere behind and above there came a steady hissing roar. Four Venus airships came into view, taking up their positions to the rear of the column at a height of about a half miles. Nyimeurnior had described these ships to me, but this was the first I had seen of them. They were upright cylinders, some fifty feet in height, and about thirty feet in diameter, crowned by an umbrella-like structure a hundred feet in diameter, and several feet thick. It was from the top surface that the air was being "electronized" into vacuum, to be rematerialized on the concave under surface.

If it were not for the light projecting and bracing steel beams which helped to hold the affairs rigid, and also provided landing gear which would not offer the same resistance to the air as a solid platform, the things would have looked like giant floating mushrooms.

They too, floated in what was practically an envelope of inverse magnetic rays, the generators being so placed as to cause the beams or rays to cross in every direction. They hung in the air above the column, calmly awaiting the swooping attack of our Air Guard.

When it came it was sudden enough. Seven squadrons of planes dove head-on at the Venus ships, spitting a steady hail of projectiles, zooming successively when they had almost reached the fan-ray film.

But it did no good. The projectiles bounced off that nearly invisible film like rubber balls from a concrete wall.

I WANTED to shout at them to use non-metallic projectiles, to which I knew these rays would offer no resistance, but of course it was ridiculous to suppose they could hear me. As a matter of fact I could not even signal them, for I was shut up in the lookout turret.

It was the frantic desire to get this information to my own side which finally prompted me to tear myself away from my point of vantage. Even as I did so I saw one of our planes collide with the magnetic wall, and hurtle down, a crumpled thing; while another caught within the effective radius of one of the suction bombs, also crumpled and fell.

Leaving the lookout turret I hurried down through the corridors and ramps with little fear that my disguise would be penetrated; soldiers I encountered several times. I had learned much of the manners, customs and courtesies of these people from Nyimeurnior, and gloved and helmeted as I was, I was covered from head to foot. Nothing but the most searching gaze through my helmet goggles! would have revealed the fact that I did not have a dead-white skin.

At last I reached the passage through which the column had passed but a short time before. There was a sentry on guard just inside the big gate, which still was open, but he was gazing out after the departing column. I simply elbowed him aside and trotted out over the plain as though I were a tardy member of the expedition, hurrying to catch up to the column. I stole a glance back over my shoulder. The plan had worked. He had not been alarmed by my action.

I was careful, however, not to catch up to the column, but bore off toward the North when I was sure no attention was being paid to me. Then I removed the helmet, and stripped off the humidor suit, which was a great relief. I think that a half an hour longer in that moisture-proof garb, under the blazing Mexican sun, would have drowned or smothered me in my own perspiration.

From somewhere to the Northwest an artillery barrage was laid down on the invaders' column. For a moment I had a thrill of elation. From the confusion it produced I thought it had succeeded in crashing through the magnetic wall. But it had not. There was the usual result, shells bouncing harmlessly off and exploding in the air above the column. The confusion evidently was produced by the surprise of the bombardment and the noise, for the battery was a long distance away, and well hidden.

For a while the column halted, and the men cowered. But few seemed to take any real alarm. In the end the machines resumed their sluggish progress, while the infantry staggered and crouched their way forward, quite safe from the explosions above them, but far from enjoying it

Farther on, the column was ambushed by a detachment of our infantry. Simultaneously another attack was launched on it from the air. But no success attended the efforts of the Earth men.

A number of the Venus ray generators were raised on extension platforms and the direction of the rays depressed. And I could see that not even a flat trajectory fire could reach the column. As the climax of the attack the planes above withheld their fire, and the Ground Guard threw three waves of infantry against the column, but only to wither away under the suction bombs of the coughing guns with which the Venusians met them. The Earth forces withdrew at last, after suffering considerable loss, and the men of the column, probably with frazzled nerves, but with little physical damage, continued to wend their tortuous, painful way across the plain, and entered the other fortress.

All this time I had been making my way Northward, until finally I passed out of sight of the two castles. That night I built a code signal fire, and inside half an hour was picked up by a high-angle plane which dropped down beside me.

AS a result of radio orders I was sent to Washington at once to report to the Ordnance Board. The knowledge I had gained of the invaders, their methods and their machines proved invaluable. Not that the Air and Land Guard General Boards had not already determined the fact that special projectiles and equipment would be necessary to penetrate the defensive rays of the invaders; but I was able to verify many of their conclusions, correct certain others, and generally expand the fund of knowledge that already had been gathered by the Intelligence Division.

I had a busy two weeks hopping from one office to another on special detail, and events moved swiftly in those two weeks. I was myself amazed at the speed with which new guns and new non-metallic shells and bombs were being turned out, and the ingenuity shown by the scientific departments of the Guard and by manufacturers in developing a non-metallic bayonet.

Troops had to be equipped with canteens, belt buckles, head gear, and buttons and fastenings on their uniforms which had no metal in their construction. The rifle, it was determined, could not be abandoned, but non-metallic cartridges were developed. The theory was that in passing through the magnetic film of the Venusians for hand-to-hand fighting the troops would drop their rifles, and use the detached sword-bayonets.

Naturally these things could not be produced overnight, nor could the troops be trained in new tactics overnight, but so intensively was the work of manufacturing and drilling prosecuted that at the end of two weeks many regiments of the Land Guard had been reorganized, and about a tenth of the Air Guard had been supplied with non-metallic bombs.

During this period, however, the two fortresses with which I had been concerned were abandoned, their communities drifting lazily and safely Southward in their mushroom ships, as did many others, finally settling in the interior of Brazil.

Perhaps I should pause here to summarize the sequence of events up to this point.

Nearly two weeks elapsed between the arrivals of the first and last of the bulbs. Seventy-two of them landed in the United States, 11 in Canada, 3 in Scandinavia, 1 in England, 27 in France, 81 in Germany, 19 in Italy, 107 in the Balkans, and hundreds in the tropic belt all the way around the Earth.

Throughout Western Europe the League's land and air forces got into relatively quick action against them. As fast as new spheres descended they were walled in by rings of troops, and roofed over, as it were, by clouds of aircraft. The one which fell in England was destroyed after two days. In France nine were successfully bombed before they could get their inverse magnetic rays into operation. The crews of the others managed, under fire, to erect their fortresses, but were so worn out by the never-ending bombardments to which they were subjected, that they were finally overcome by the charging waves of infantry who had been armed with wooden clubs and short spears. Twelve communities fled Southward in their air ships, but ran into atmospheric conditions that were horrible to them in Northern Africa, where the lack of humidity caused them terrible losses.

Of the hundreds that landed in Africa, the majority perished. The remainder made their way either Eastward or Westward around the Equator to the fastnesses of the Brazilian jungles, where they constructed their great stronghold.

At the end of three months none of the invaders remained anywhere in the civilized sections of the temperate zones. The story of those invaders who established themselves in such lands as Tibet and Siam, and how they ultimately perished, has not all been unearthed yet from the ruins.

Fifty-seven of the colonies that fell in the United States were destroyed. The others fought their way through our air forces toward the Tropics.

Then there ensued a period of two months in which the invaders and Earth men were content to let matters rest while they took stock of the situation and prepared for the greater struggle to come.

The men of Venus did very little of the raiding they had intended, according to the plans Nyimeurnior had explained to me during my incarceration. Time and again our air fleets coursed over the Brazilian forests, but seldom did they find evidence of the enemy's works. The invaders had learned well to conceal themselves under the leafy protection of the jungle. They had learned too, to raise no lava fortresses where they could be seen from above, and also to conceal the flow of their volcanic wells.

They had little chance of meeting us successfully in the air now, for our air fleets had been given bullets and projectiles of non-metallic construction, against which the fan-rays of the invaders were of no avail, and it became more a matter of sport than anything else among us of the Air Guard to sight a mushroom ship, or squadron, and shoot it down. Their suction bombs were destructive, but we could move too fast for their ships and outclimb them easily.

However, according to the best estimates, there were close to one million of them now established in the Brazil jungles, where they were busily readjusting themselves to Earth conditions, constructing their ingenious machines and developing their resources in preparation for a future outbreak which we all feared would be far more devastating than the effects of their haphazard and uncoordinated activities at the time of their arrival upon Earth.

The paucity of information on their movements in the jungle was ominous. Terror-stricken Indians staggered into the Brazilian military outposts with tales of wholesale and mysterious slaughter, of mists that travelled purposefully through the jungles, from which ghost-men emerged to slay.

Brazilian military reconnoitering parties went out and failed to return. Once a mist cloud moved out of the jungle and enveloped an outpost. When it retreated, according to the story of a soldier who had been outside the lines, the entire garrison had been massacred.

Yet these mists were never observed above the tree tops.

THE Brazilian Government had made its formal appeal to the League for help, according to the League Constitution, and a gigantic army, recruited from all the nations in the League, was to surround the vast jungle territory.

Ten million men were to be used, for though they would be opposing only about a million of the enemy, they would be fighting for nothing less than the existence of the human race, and would be facing the unknown.

This was the general situation. And while this immense army was being mobilized and equipped, a call was made for volunteers who had had contact with the enemy, to attempt the highly dangerous work of penetrating the Brazilian forests as scouts and spies. And I, having no better sense, volunteered.

That was why I found myself ensconced one night in the upper branches of a tree far in the interior, in a section where I had finally found evidences of activity. I wore an imitation "humidor suit," that was an imitation only in its clever arrangement for ventilation. It was in fact, a real Venus garment which for the moment was suspended on my chest like an old-fashioned gas mask, but was in reality, a gas mask, and several other things besides. In my hands I held a little box, a tiny radio broadcasting set. Scattered around me through the forest at strategic points, were carefully concealed bombs and flares, each tuned so that by pressing the proper button on the box I might set off any particular bomb or flare by radio impulse. I had spent the day planting these mines, among which were a number of gas bombs.

All these arrangements were precautions of self defense. I had no intention of carrying on a campaign single-handed. But I had picked the spot for several days patient observation, for it was here that I had noted several fresh trails that appeared to my unwoodsmanlike eye to converge and come to an end for no reason whatever in a little clearing not far from the tree in which I was hiding. A quarter of a mile away, carefully hidden, I had one of our new helicopters, developed by the Air Guard, a machine that was powerful and as nearly silent in its operation as any device using an air propeller could be, and far beyond sight a great dirigible was awaiting my communications.

But since nothing at all happened that night, and no sounds came to my straining ears except those of the normal animal life of the jungle, I determined the next night to try an experiment.

I waited until after midnight, and then pressed a button on my radio control box which resulted in a terrific explosion about a quarter of a mile farther on in the jungle. I got the flash of it even through the dense growth of the jungle, and my tree trembled with the force of the detonation.

Immediately there was a series of purplish flashes in the sky above that spot, which merged into a continuous mass of pulsating lights, as the preliminary thunderclaps grew into a continuous roar. My experiment had proved profitable. I had learned something. I knew those flashes and thunderclaps as the product of the "coughing" guns of the enemy. But the power of this barrage exceeded by far anything I had seen while a prisoner among them. As suddenly as the uproar had begun it ceased. And silence once more settled over the jungle.

It was evident that I had stumbled into the neighborhood of a Venus artillery post, and no mean one. My bomb had been mistaken for one dropped from an airplane. The next day I searched for the location of that battery, but could not find it.

The night following I slept, but devoted the day after that to another painstaking search of the jungle. At last I found a spot where the foliage of the trees above me appeared to have been shredded and torn. I searched the ground carefully. My patience was rewarded by the discovery of a beautifully-designed camouflage, a screen of moss and leaves which concealed a pit. The battery was buried underground, and fortunately for me, must have been unmanned and unguarded at the moment, although this did not surprise me, knowing as I did how the invaders hated our atmosphere in the daylight, even when wearing their humidor suits.

The gun crew, I was sure, was also somewhere below ground, probably sleeping, and the sentry, who must have had some post of vantage from which he could see the sky, was evidently so placed that he could not observe the floor of the forest.

As quietly as I could, and I must admit, with some fear, I slipped away to where one of my bombs was concealed, and carried it carefully to the pit, where I concealed it in some undergrowth nearby. That night I took up a new post in a tree from which I could see the mouth of the pit and detonated another of my bombs some distance away.

The phenomena of several nights before was repeated in the air, but I did not watch it this time. I kept my attention centered upon the mouth of the pit. The screen had been blown aside, and so fast was the buried gun firing (it seemed to be only one) that its discharges blended into a continuous, faintly luminescent column that tore through the upper branches of the trees.

After a bit the gun ceased firing. About a quarter of an hour elapsed. Then a faint light appeared near the mouth of the pit, by which I could observe the figures of a half a dozen invaders. Two of them were naked-white in the soft, warm tropical night, but the others wore their suits and helmets.

One of them was placing a new screen over the mouth of the gun pit. Others were carefully gathering up the debris torn from the trees above.

My first instinct was to slip to the ground and creep up on them. I felt that in the darkness it would not be noticed that there was an additional member of their party, and I might be able to follow them underground. But caution prevailed and I determined first to communicate my discoveries to the dirigible somewhere in the sky above.

We had planned an ingenious method of doing this. With the first grey light of dawn I felt my way back through the jungle to the spot where I had left my helicopter, for my radio would not have been powerful enough to reach the ship, nor would I have dared to use one for a continuous message. The enemy might have picked it up and located me. The small amount of power, and mere instantaneous spark that I used to detonate my bombs did not matter.

From one of the compartments of the helicopter I took a tiny model of the same sort, equipped with a little chemical engine. The whole thing was little bigger than a cigar box. I wrote my report and attached it to the model, which I shot vertically into the air. When it was five thousand feet up, it would automatically broadcast a range-finding signal, and emit a faint smoke trail, which would enable one of our planes to pick it up. It would rise under its power for many hours, then drift down on a little parachute, and finally, if not picked up by the time it drifted below the 5,000-foot level, it would burn, destroying the message.

I SLEPT the rest of the day, for I expected to be very busy that night. After nightfall I returned to my post near the gun pit, but did not climb the tree. Instead I hid behind its vast trunk, and pressed the button that would detonate the bomb I had placed near the gun pit.

It blew a great gash in the ground, and must have put the gun out of commission, for no roaring barrage followed, but a short time afterward ten or twelve soldiers broke through a screen of creepers, and by the faint light of hand lamps excitedly inspected the crater my bomb had torn at the edge of their gun pit. They jabbered laconically in their strange "shorthand" tongue, frequently pointing upward.

I circled and came up behind them, joining their party, yet not getting too close to the others as I made a pretense of searching the ground, and looking fearfully up toward the sky, where only a couple of stars were visible through the dense foliage. After a bit their leader, a man bigger than the rest, who had not donned his humidor suit, grunted a command, and one by one they disappeared through the screen of creeping vines.

I approached with the rest, but hung back a bit, hoping the commander would go in ahead of me. But he did not, and in the end he grunted an angry command. He must have become suspicious as I passed him. Possibly he had been counting, and realized that he had an extra man. At any event, he reached out and grasped my arm.

But I was on the alert for such a danger. Twisting quickly I drove my fist against his unprotected jaw, and he went down like a log. And pushing my way through the screen I found myself in a cleverly concealed passageway which slanted down below the ground level. Following the lights of the others around a couple of turns I came upon a section of corridor that was dimly lighted. After a bit we came to a junction of several corridors, and the men turned sharply to the left down a small tunnel. I paused a moment to take stock of this structure and if possible get my bearings. My little compass made several things clear.

The tunnel the men had followed evidently led back to the gun pit. A main corridor, much larger, stretched away in a great curve to the South. Another curved gently Northward. And toward the West a third one, larger than any of the others, slanted downward at a sharp angle. In the big chamber where these corridors came together—which incidentally reminded much of one of our old subway stations in New York—were a number of big, complicated pieces of machinery. They were not in operation at the moment, however. From down the big West shaft came a distant murmur, which little by little grew in intensity, until I finally thought it advisable to seek cover. I hid behind one of the machines.

The murmur grew into a roar. The roar increased. And there shot out of the tunnel into the big "station," where it came to an easy but quick stop, a great projectile-like car. It had no wheels, but apparently rode on two systems of magnetic devices, one running like a spine along the top, the other like a keel along the bottom.

As I noticed this, the car settled down a few inches, and rested with a bump on the lava-like floor. Several doors in the side opened, and a stream of soldiers began to troop out. At the same moment several of the gun crew came running out of the small corridor. They made their way immediately to the commanding officer of the newcomers, evidently a man of high rank, from the breadth of the belt he wore and the numerous insignia appearing on it, and made their report in some excitement. They knew by now, of course, that their battery commander was missing.

He replied angrily. I gathered from his impatient gestures that he was reprimanding them for not returning to the jungle to seek their officer. And I realized I was facing a crisis.

But I dared not come from behind the machine to join the throng at this juncture, for none of them was in a humidor suit, and I would have attracted unwelcome attention instantly. I was forced therefore, to watch the squad which rushed off at once toward the exit to the forest, and see my retreat cut off.

It struck me that, strategically speaking, it was high time for a diversion if, on finding their commander outside, they were not to start an immediate search of the tunnels. So I drew my radio detonator out and pressed one of its buttons, then another, and finally a third.

There was only one explosion, which came to my ears faintly and muffled from a point some three hundred yards away in the forest. The other two bombs would make no noise. One was a smoke bomb which would so smother their hand lamps that they would hardly be able to see their hands before their faces. The third was a gas bomb, and would give those who breathed its fumes something new to think about, I hoped, for as long as they were able to think.

As I expected, a detachment of only twelve men or so was sent out to investigate. Another detachment, armed with tools and implements of various descriptions, ran down the corridor toward the gun pit, and soon the sound of their apparatus was clanging in my ears. A party from the gun pit came back, and after reporting to the commander, who was pacing up and down impatiently, ran to one of the machines near that behind which I was hiding.

They swarmed over it, manipulating little wheels and levers. And to my surprise the mass of machinery, which reminded me something of a small newspaper printing press, lumbered to lever-like feet, and shambled away down the tunnel to the pit.

Every few moments the commander glanced impatiently toward the forest-exit corridor. Finally he motioned to one of the girls in the ranks behind him (for as I mentioned before, they seemed to make no distinction as to sex when it came to labor or military service) and she ran off toward the exit. But she did not return. Nor did any of the others. I opined that my gas was working nicely, and now bitterly regretted that I had failed to fill my pouch with gas grenades from my helicopter.

At last the officer barked an order. The rest of the soldiers broke ranks, unstrapped their humidor suits from their belts and donned them. Another order and they all moved briskly away toward the exit, trailing their short spears. I slipped into the rearmost ranks and went along with them, for my purpose now was to regain my helicopter, and send up another message to the dirigible, explaining what I had seen of their corridors, and system of underground structures.

THE head of the column passed out through the screen of creepers. Others followed. Then suddenly the column recoiled. Some of those nearest the screen sank down gasping and choking. Others staggered and leaned against the walls.

Through the confusion I could see that some of them had torn away the foliage of the screen, revealing the piled up bodies beyond. At this moment a gust of wind sent a billow of the black smoke surging into the corridor. The rest of the column turned and fled from it, crowding back down the corridor.

I chuckled as I crouched to let them pass, my gas mask in place, for I remembered the rumors that had reached us of these people leaping from white fogs that roamed the surface of the jungle. The black fog and deadly gases of Earth laboratories were reversing the terror.

As the last of the fleeing enemy disappeared around the bend in the corridor, I arose and made my way to the outer blackness, where I stumbled around for more than an hour before I won free from my own black fog and gas, and located my helicopter.

At dawn I shot another baby "heli" up with my report, and filled my pouches with gas and smoke grenades. I wanted to return and get a more comprehensive idea of the extent of their corridor systems, for I was convinced by now that the whole invader's population had taken to burrowing into the Earth. In digging their volcanic shafts it would be no impossible task for them to adapt their wonderful machines for fashioning the lava product into underground corridors and chambers instead of the castles or fortresses they had first built above ground. If this were the case, our armies were going to have some little task ahead of them in digging them out.

I did not have an opportunity to pursue my investigations further at that time, however, for I had hardly turned from my helicopter when I became conscious of the slight, continuous buzz in my radio box that was the prearranged signal ordering my return to the dirigible.