RGL Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

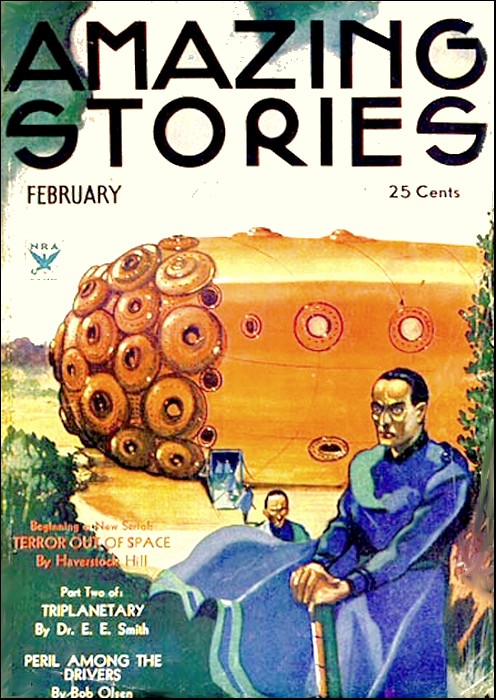

Amazing Stories, Feb 1934, with "The Time Jumpers"

OUR first experience with the time-car was harrowing.

It followed two experiments in which I had shot the contraption into the past and brought it back to the present again under automatic control. A very simple clockwork mechanism had served to throw the lever after I got out of the car, and then to reverse it again after ten minutes.

I had set the space-time co-ordinates for roughly 50,000 years, had hooked up the clockwork control, and stepping out, was about to close the door when Spot, a mongrel terrier, who used to make himself at home around the laboratory, frisked into the machine out of my reach and barked playful defiance at me.

In less than two seconds the car would start its maiden journey into the past. Spot wanted to play tag inside the car, and kept out of my reach. I didn't dare go in after him. I had no intention of risking my life in any time-traveling adventure until I had a better idea of what would happen.

There was only one thing to do. I slammed the door and let Spot make the experiment.

Two backward leaps carried me to the opposite wall of the laboratory. From there I watched in breathless fascination.

Spot was up on his hind legs at one of the heavy quartzine windows. I could see rather than hear him barking. I could see too the blue glow that flashed up in one of the vacuum tubes inside the car. There came a low humming noise that grew in pitch and intensity until I clapped my hands to my ears. Then I blinked, for the car was wavering and flickering, faster and faster as the hum faded into wave-lengths too short to affect my eardrums. It took on an intangible ghostly appearance. I could see right through its shadowy form. Then it was gone.

I RUSHED to the spot where it had stood, waving my arms in front of me, and even ventured to stand where it had been. There was no doubt of it. It had gone.

I don't know how many minutes elapsed before I backed away from that spot again. I had been too excited to look at my watch. But when I realized how dangerous it would be to be standing there when the car returned—if it returned—I not only backed away, but scrambled for the great outdoors, taking a position some hundred feet away in the field to stare at the laboratory doors, while my heart pounded away the slow, breathless minutes. If my calculations had been correct the car should return precisely to its former position. But they might not be exactly correct.

Nothing happened until I was conscious of the unpleasant feeling in my ears. Then the high whine became audible, and lowered in pitch until with a rumble it ceased, and I ran excitedly for the doors.

The car was there, not a foot out of position, but coated with black, dank mud nearly one-third of the way up. Spot was not at the window.

But Spot wasn't dead. I could hear his terrified yowls plainly even through the thick walls of the machine. When I threw open the door he slunk whimpering out, and not for several minutes did he recover sufficiently to begin jumping at my legs in an access of gratitude.

Maybe it was the operation of the machine; or maybe it was something he saw in the dim, distant past, into which I had hurled him so unceremoniously, that had terrified the dog. But at any rate, the important thing was that he had come through the experience safely. And, I figured, what a dog could do, I could do.

I left the co-ordinates as they were and sent the machine back again the next day, after I had rigged an automatic movie camera inside it. Again the time-car came back safely; but the film on development proved a disappointment. The exposure wasn't right, and it had registered only the faintest of impressions, of fern-like vegetation and great shadowy beasts. It was hopeless to even try to identify them.

IT was just a couple of days after this that Cynthia dropped in and nearly got us both into trouble. Cynthia is a kind of a cousin. At least I have always regarded her as such. She's the daughter of old Dr. Smith, inventor of the cosmic energy generator which is now so rapidly revolutionizing industry and transportation. He was also my guardian. I always called him uncle, and so Cynthia has always seemed like a cousin to me.

She used to stop in at my laboratory every once in a while to see how my "crazy" idea of the time-car was developing. She knew all about it, of course, because her Dad had been good enough to supply me with one of his generators after I had used up all my modest fortune in buying up the total world supply of dobinium. There wasn't much of it, just a few ounces that had been extracted from a meteor that fell in Arizona. It was valuable only as a scientific curiosity, for no experimenters but myself had ever found a practical use for it. Yet when induced to activity through a bombardment of rays from the cosmic generator, its emanations formed the basis of the complex reactions of pure and corpuscular energy by which I was able to cut the curvature of space-time and hurl a material object backward along the time co-ordinates.

Of course I had explained it all to Cynthia many times, and I believe she did grasp the fundamental idea of the thing in a vague sort of way. She couldn't be her father's daughter, without having some sort of scientific head. But she had always been a bit skeptical about it.

"Why Ted Manley!" she gasped. "You don't stand there and expect me to believe that you actually sent this thing backward in time, and then brought it back—I mean forward—or whatever you call it, into the present, do you?"

"Ask Spot," I told her. "He made the trip in it." Spot jumped and cavorted around, trying to share her interest with a stick that he alternately dropped at her feet and pretended to run off with.

She tossed her head. "I don't believe it," then more seriously: "Why Ted! You—you know the whole idea is so—so unbelievable! There must be some other explanation." All the while she was gazing at the time-car with a curiosity she had never shown before.

"May I get in it?" she asked at last, and as was typical with her, she jumped in and sat on one of the leather-padded seats without waiting for my reply. I followed her in and closed the door.

"It is simple enough to operate," I said. "All you have to do is set the space-time co-ordinates so the beam of the indicator light falls on the year you want to visit. The motion of the earth through space since that time has been calculated and the machine set for it. I never would have been able to do it if they hadn't let me use the Calhoun Calculating Machine down in Washington." I waxed more enthusiastic. "But that isn't all! You see this adjustment here? By simply setting the latitude and longitude dials you can bring the machine to any part of the earth you want to—"

"And what's this lever for?" Cynthia interrupted me as she reached above her head. The lever moved half an inch under the pressure of her hand. And we were in for it!

A SUDDEN droning hum, rising in pitch rapidly, made our teeth chatter and our ears hurt. Cynthia, her pretty little face a picture of horrified astonishment, shrieked as she glanced out one of the quartzine windows and saw the laboratory vanishing in a shimmering maze of vibrations.

"Now you've done it!" I groaned. "I don't know what the co-ordinates are set for, nor when or where we're going to land!"

Cynthia just had time to flash me a look of contrition, when again we felt the intangible pain of the vibrations, which lowered in pitch until they were audible and then rumbled to a quick stop. We turned frantically to the windows.

SAND dunes everywhere. No. Over to one side, where we could see between them, there was a glimpse of blue-green sea. The time-car was half buried in the sand, tilted at a slight angle. Otherwise everything seemed quite natural and we were in full possession of our faculties, having suffered no discomfort other than the terrible ringing in our ears and uncomfortable sense of vibration, which evidently had been due to the sound alone. Cynthia was still gasping for breath.

At length she gathered herself together and said: "Well, Ted, at least your machine goes somewhere! This looks like a deserted part of the Jersey coast to me."

"You'll find we've gone somewhen as well as somewhere," I replied, "but I haven't the least idea about—"

"Ted! Look! Look!" Cynthia grabbed my arm and pointed through the window toward the ocean.

A strange looking craft had run up on the beach even as we had been talking. It was a long, slender affair resplendent in brilliant colors, with a striped, square sail, and a row of shields along the rails. Long sweeps, glistening in the sun, were tossed inboard, and several armored figures leaped into the shallow water and waded ashore. They carried axes, and looked warily toward the dunes.

"Norsemen!" I muttered. "Now do you believe me, Cynthia?"

The girl gulped and nodded. "You win, Ted," she admitted. "It's—it's magic!—unbelievable! But, oh Ted, I'm kind of—frightened. Suppose something should—should happen!"

And as if enough hadn't happened already, one of the Norsemen spied our little time-car through the gap in the dunes. He pointed to us with his axe and spoke to another Norseman, evidently their leader. This one raised his arm, pointing first to the left and then to the right, and two compact parties of warriors trotted out of our line of vision, heading toward the dunes as though to top them at some distance to either side of us. A third group, under the command of the leader, waited, gazing in our direction.

There was nothing for us to do but wait, or flash back to the Twentieth Century. We were partly buried in the sand and it was impossible to open the doors.

AFTER a bit the Norsemen on the beach must have received a signal from those who had disappeared, for the leader waved his arm to the right and left. Then, with the remaining group he marched grimly toward us through the soft sand.

They paused about fifty feet away and exchanged startled glances as they caught sight of our faces pressed to the quartzine windows. The chief waved his axe and shouted something. They all came running toward the time-car, spreading out to surround it. And I didn't like the look on their faces as they closed in.

"I—I think we b-better be g-going," Cynthia suggested. I thought so, too, and reached for the reverse lever. But to my consternation the handle moved too freely, and the shaft didn't turn at all. The little set-screw had loosened, and must have been barely hanging in place by the last thread, for when I fumbled at it with clumsy fingers, it dropped out. And to make matters worse, I snatched at it instinctively and only succeeded in batting it out of sight somewhere on the floor.

I heard Cynthia's little gasp of fear as I dropped on my knees to search for it. It was not to be seen. In a panic I jumped to my feet again, wondering if I could turn the shaft with my fingers.

The Norse warriors were not a bit frightened by what must have appeared to be a weird metal box. Nor was there the least sign of friendliness in the bearded faces that pressed against the windows, or the fierce, hostile eyes that glared in at us with glances that roved curiously over the intricate set-up of coils, condensers, and the blue glow of the vacuum tubes.

Suddenly they withdrew a few paces, and an argument developed between the leader and another. They pointed toward us with their axes.

"Quick, Ted!" Cynthia whispered. "What's the matter? Throw the switch! Can't you see they're going to try to break in?"

It was true. The warrior who had been talking to the chief stepped up and took his position before one of the quartzine windows, planting his feet wide and swinging up his great axe for a mighty blow.

I gripped the starting shaft with my fingers until they hurt. I saw the Norseman's bearded lips curl back, and his muscles tense. I felt the shaft turn reluctantly.

Instantly the time-car hummed and vibrated. Slowly at first, it seemed, the axe swung downward. Then faster. The hum was a high whine.

Down came the axe in a powerful, slashing stroke as Cynthia and I shrank against the far side of the car. Straight through the side wall and quartzine window it clove, as though nothing were there to stop it. Amazement and panic flashed in the warrior's eyes. Then the shrill whine was descending to a hum that lowered quickly to silence. Through the windows of the time-car we saw the interior of my laboratory; and Spot, his tail between his legs, scrambling madly for the peaceful sunlight beyond the open doors of the building.

Cynthia was visibly trembling, and I know my own hand was none too steady as I helped her out of the car. She pushed me aside, weakly. With a sort of hollow feeling in the region of my stomach, and in a bit of a daze, I watched her as she walked a little uncertainly to the laboratory doors and inspecting herself in the tiny mirror of the frame, powdered her nose.

Then she turned and said: "We'll be better prepared for our next trip!"

CYNTHIA simply wouldn't hear of being left behind on the next trip. All my arguments as to the dangers involved fell on deaf little ears. I turned to propriety.

"But listen, Cyn," I protested. "Can't you see I can't let you do that? It would be highly unorthodox."

"Could anything be less orthodox than jumping into the past across time curves, or whatever you call them?" she countered. "Why strain the straw off the camel's back and then swallow the camel?"

"But you've got to remember that we're not really cousins," I insisted, "and it wouldn't be right to go off this—"

"Who's going to see us," Cynthia interrupted, "except a lot of people who have been dead for centuries maybe? Pooh for them! Don't be so completely ga-ga, Ted. We've known each other like a brother and sister all our lives, and if Dad could go off to Europe and trust me here during vacation, I don't see why—"

"All right. All right. We won't argue any more about it," I conceded. "Maybe we can make a short trip anyhow; start early in the morning and be back at night. What period do you think we should visit?"

Cynthia suggested Colonial days, or the American Revolution. "Think what a lot of hopelessly lost historical data we could gather, Ted," she said. We couldn't have gotten anything out of those Norsemen anyhow, even if they hadn't tried to smash us up. We couldn't have understood their language."

"No," I admitted. "But at least we established one thing. The Norse did get as far down as the Jersey coast. Do you remember how fine that sand was? I don't think there are any beaches just like that, with such fine sand, much farther north than the South Jersey coast, are there? And by the way—we were so excited we never checked up on how far into the past we went."

We looked at the time-car's control dials. They registered 968-237. That meant 968 years ago, and 237 days; or, as a rapid calculation showed me, June 7, 993 A. D.

"Maybe it was Leif Ericson himself we saw," Cynthia ventured.

"Maybe," I agreed, "but I don't want to be caught again by Leif or any of his friends; not cooped up in an iron box half buried in the sand that way. What we've got to do, Cyn, is to equip this car with a flock of rocket tubes, so we can shoot up in the air with it before we jump the time gap. Did you ever stop to think what might have happened if we had materialized in the year 993 under a pile of rocks or something? We can't always be sure what was at a given spot on the earth's surface at a given time. Maybe the ground level was way above what it is now, or way below. We might be buried—or drop a couple of hundred feet!"

"Any way you dope it, Ted, will be okay with me. Well, I'll be seeing you." And Cynthia hopped into her neat little sportster rocket plane and flashed away toward town.

IT took me several days to make the necessary changes in the time-car. Fortunately I had counted on the possibility of making them from the beginning, and had designed the car so that the rocket tubes could be readily attached.

History contains many references to flaming "stars" in the sky. Of course the natural thing to assume is that the ancients had so recorded the observation of meteors. Even to-day people talk of "shooting stars." But I chuckled as I wondered if any of these might have been—or would be—whichever way you choose to put it—my time car, riding down on its rocket blast, or shooting across the countryside.

Cynthia and I decided we'd try to land near New York about the year 1750. But the problem of costume bothered us. The things you can get from a theatrical costumer may pass pretty well behind the footlights in 1962, but we had a hunch they'd look pretty sad face to face with the people of 1750. In the end we compromised on a plan of representing ourselves as frontiersmen. That wasn't hard. Cynthia sewed fringes on our shirts and made fur caps with tails on them. She got herself a haircut like mine, and when we were all dressed up she might have passed for my younger brother. Both of us had spent plenty of time outdoors, so we were sufficiently tanned for the parts we determined to play. And for safety's sake we carried in concealed holsters a pair of neat little rocket guns that discharged tiny explosive rockets with no more noise than a slight hiss.

We roared aloft on a powerful blast, and after a careful survey of the sky to see that, there were no other craft near enough to take notice of our sudden disappearance in mid-air, we jumped the time-gap.

I THOUGHT I had set the co-ordinates for a spot on the Hudson, a few miles above New York. But either I made a mistake or there was some slight element of error in the mechanism, for we materialized over a wooded countryside that was not familiar to us. The forest, however, offered good concealment for the time-car, and we descended. It was something of a job to bring the bus down among the trees, but at last I maneuvered over a tiny clearing, and let her drop.

"Now that we're here," I said, "and all ready for the adventure, I don't quite like the idea of leaving the time-car. It seems too much like cutting off our only possible method of returning to our own century."

"We might have to stay here, and get married and become our own ancestors," Cynthia giggled. Then more seriously: "You've got a lock on it, haven't you? Lock the door and come on."

"You know, Cyn, that's a puzzling aspect of this time-traveling you just brought up," I said as we headed into the woods away from the machine. "Seriously now, just suppose we did have to stay here in this period, and we did get married and have children, and our own descendants were—I mean will be—hobnobbing with us back—I mean forward—in 1963!"

Cynthia thought this one over. Then she said: "I have a feeling something would happen to prevent that, Ted. I don't pretend to understand all this relativity thing. And I don't know more than the A B C of the space-time continuum. But I just have a hunch that somehow that sort of thing couldn't happen. I don't know just how to explain it. It's as though we don't really belong in this century—as though we're not really all here, even though the ground is solid under foot, and the trees are very real, and so on.

I don't know whether you noticed it or not," she went on, "but something very funny happened to us back there in 993. That Norseman's axe sliced right into the time car. The blade was way inside the field of the coils. But it didn't come back to the 20th Century with us in the car."

"Well that incident is easy to explain," I said. "I won't go into the mathematical theories involved, but I can give you a kind of a simile. It would be relatively as different a thing for the Norseman to go forward into the future as it would be for us to return back into the past. And our time-car isn't designed to carry anything forward into the future. But even if it were, you see, it could only be done along the co-ordinate of the time-norm and the Norseman would be dead some ten centuries as we arrived back in the 20th Century. We'd have nothing with us but his skeleton, if we had even that. See? You can't go into the future except along the norm, and that means the full ageing process, even if you accomplish it in a relative instant. It's quite different from our returning to the future where we already—"

"You needn't bother to go any further," Cynthia cut in. "I'm dizzy. But I still have that hunch that though we seem normal and feel normal in this period, we're really not entirely real and—Oh what's the use of trying to put it in words? Anyhow, we're not going to be caught in this century and have to stay here."

BUT something happened at this instant that made it look as though Cynthia was wrong.

Something whizzed blindingly between our head and thudded into a tree behind us, where it stuck, quivering. It was an Indian arrow!

For one startled instant we stood as though paralyzed. Then Cynthia cried out: "Back to the time-car, Ted! Don't let them get there ahead of us!" And we were racing madly back through the forest to an accompaniment of blood-curdling yells that seemed to come from every direction.

Now more arrows were whirring past our ears, and the yells were closer. Cynthia tripped over a projecting root, and had I not caught her, would have fallen flat. As it was, we lost precious seconds.

Just why neither of us thought to use the rocket guns, we had so carefully provided ourselves with, I don't know. I suppose it was because neither of us was accustomed to firearms and we didn't instinctively think of them. People act more by instinct than by reason in a crisis like this.

That neither of us was hit by the savages' arrows was due no doubt to the fact that the forest grew very thickly here, and it was difficult for them to get a clean sight on us as we ducked, dodged, jumped and skipped among the trees in our desperate flight.

We were back now, I thought, where the time-car should have been. But we must have veered off our path, for I could catch no glimpse of it among the trees ahead. There seemed to be no escape for us. The Indians were closer than ever, and flashing occasional glances over my shoulder, I glimpsed bronzed figures following, and felt that their purpose was not so much to overtake us as surround us.

Then suddenly the horrifying war whoops were stilled. And glancing back, I saw no bronzed bodies among the trees.

"Wh-what's the ma-matter?" Cynthia panted as she ran. "Aren't th-they ch-chasing us any m-more?"

"I-I do-don't thuh-think so," I replied. "But we—better—k-keep running!"

We continued our desperate flight a bit farther, but when there was no sign of pursuit we slowed down to a hurried walk, panting and gasping too hard to talk right away.

"I don't think we came nearly this far, from the time-ship," Cynthia said at last. "If we've lost it, Ted, we are in a tough spot!"

"Well, I'm afraid we have," I had to admit. "But I'm even more uneasy about those Indians. We must have looked like easy pickings to them. I wonder why they quit so suddenly?"

I had lagged a few paces to look back. When I turned to follow Cynthia I ran square into her. She was backing toward me, her arms outstretched to warn me, her gaze centered on a spot in the forest ahead where an indefinable patch of bright blue showed.

"Do you see it?" she whispered. "It's cloth I think. And I'm sure I saw it move!"

A voice, all the more startling because of its low, tense tone, made us snap our eyes suddenly to the left. "Stand where ye are!" it commanded, "and reach for no weepons!"

Only half concealed behind a tree a blue-coated figure stood, leveling a long rifle at us. Two or three others were moving softly out from their concealment toward us. I heard a faint sound to the right. There were more of them. We were surrounded.

"Reach for the sky, Cyn!" I said under my breath. "We're in a trap!"

Except that they were all badly in need of shaves, and their hair, which was arranged in little pigtails, looked kind of gummy, they didn't seem like a bad lot. Some wore buckskin leggings with their military coats, and others wore coonskin caps, and some had fringed hunting shirts. But there was an air of alertness and straightforwardness about them that relieved my mind considerably.

"Colonial troops!" Cynthia whispered.

"I hope so!" I replied.

Their leader stood before us now. "No rifles, hey?" he said. "Where did ye come from? Ye're not French!"

Hardly," I replied. "We-we got lost. And Indians chased us."

"They'd be Algonkin devils," he commented. "Allies o' the French. They'd had yer skelps before now if—but here! We got no time to waste. Hi there! Robinson! Altrock! Take these two pris'ners back to the Colonel, will ye! And mind ye salute him precise. What with these red-coated macaronis tramping all through the forest, the Colonel's startin' to set a heap o' store by cer-ee-monial!" And with that he was gone. His men, too, with the exception of the two into whose keeping he had given us, had faded silently into the forest.

And now a vague sound, of thousands of men tramping and crashing on through the forest in the distance, came to us from the other direction.

"Where are you taking us?" I asked one of the lads, for both were but youngsters.

"To th' Colonel," he replied curtly as they started us off down a trail in the direction of the crashing sound. And after a bit he made us draw aside while a long column of grenadiers in brilliant scarlet and white uniforms, marched by.

"British Redcoats!" Cynthia exclaimed.

"Aye" the boy muttered bitterly. "The rapscallions! One of these days the Colonies'll get tired o' their high-handed ways an—" A bit startled at his own temerity he let his remark trail off into incoherence.

Our two guards weren't so communicative. Besides, Cynthia and I were getting an eyeful of the Britishers. They weren't nearly so impressive, we found, as the pictures of them in the history books. The queues and powdered hair didn't stand close inspection, and the mixture of sweat and powder didn't improve the appearance of the rather ill-fitting scarlet coats. The officers, of course, had better-fitting uniforms and were much snappier in appearance. But all of them were pretty sorry looking from the knees down. The column evidently had forded a creek and splashed mud all over itself. And the high grenadier-hats frequently were knocked off by overhanging boughs, causing considerable confusion and evoking blistering comments from sergeants. Altogether it gave me quite a chuckle, and I saw the corners of Cynthia's mouth twitching.

Immediately after the grenadiers came a party of mounted officers. Most of these wore the scarlet of the British regulars, but there was one conspicuous in buff and blue, whose keen glance instantly spotted the two Colonials and ourselves. He leaned forward to say something to the rather pompous Redcoats ahead of him, who could have been nothing less than a general, and saluting, pulled out of position and rode over to where we waited, well off the trail.

"Robinson and Altrock, isn't it?" he inquired as the two lads executed smart salutes. "And whom have we here? Prisoners?"

"Aye, sir! The Cap'n sent us back wi' them, sir."

NOW I had been gazing at this big, deep-voiced officer, with a disconcerting feeling that I had met him before, which of course was obviously ridiculous, since I had spent all of my life, but the past hour or so, in quite another century. And I noticed too that Cynthia was looking at him with astonishment.

"General Washington!" she burst out at last. "The Father of His Country!"

He turned on her sharply: "What's this—what's this?" he demanded. "You know me? But what is this nonsense of 'General', and 'Father of My Country'? I am Colonel George Washington, of General Braddock's staff. But I don't understand the rest of your remark!"

Cynthia drew back in confusion as I whispered to her: "Sh! He isn't a general yet, and the Revolution has not been fought yet, Cyn!"

Washington heard some of this, I thought; and I fancied I saw a startled gleam in his eyes for just a moment. But if so, he had a good poker face. Even as I looked, his face was grave and calm. The two Colonials told him how they had picked us up in the forest, and mentioned the force of Algonkins that had chased us. He seemed concerned at this.

"We're halting a few rods up the trail," Washington said. "Bring your prisoners up there. General Braddock may want to question you, young men." His second remark was addressed to us. Evidently he had not penetrated Cynthia's disguise. He swung his horse about and galloped away.

Cynthia nudged me. "Why didn't you tell him?" she demanded.

"Tell him what?" I asked, still somewhat in a daze from the novelty of meeting a great historical character face to face, in the flesh.

"Why, about the ambush, stupid!"

"Oh," I said. "I forgot about that. But I will tell him."

IT was about twenty minutes later that we approached Washington for the second time. He stood alone with General Braddock. The other officers had withdrawn. Braddock's manner was a bit impatient with Washington, though in a friendly sort of way.

"How now, Washington?" he was saying. "What can these ragged Colonials of yours, and these two babes o' the woods, tell us that we don't already know?" Washington winced and frowned slightly at the reference to "ragged Colonials," but he said:

"If it please you, sir, they have to report a large force of French Indians ahead of us. The point is they must have known of our near approach or they would not have been in such great force, nor withdrawn so quietly and readily."

"Gad's 'Ounds, sir!" Braddock said testily. "But we already know Indians and French are ahead of us. And they must needs learn of our advance before we reach 'em! What of it all?"

"Just this sir!" I stepped forward and saluted. "It is the intention of the French to ambush you, and—"

"What!" Braddock roared. "Ambush British Regulars! Let them try it! We'll sweep straight through their ambush with cold steel!" He turned angrily away, and addressing Washington, said:

"Come. I'm sick of this assumption that any naked rabble of savages the French can gather together with bribes of beads and trinkets can halt the advance of regular troops. You hear me, Washington? We're going straight through to Duquesne.* Let me hear no more of any talk to the contrary." And he strode off, the very picture of stiff, military indignation.

* Now Pittsburgh.

Washington gave us a quick glance and raised his eyebrows significantly. He nodded his head slightly toward the forest.

"He means for us to scram," said Cynthia.

"How about it?" I asked the two Colonials. "Do we go free?"

"I reckon ye do," said one of the lads slowly. "Our orders was to bring ye to the Colonel. We ha' done that. There's no more orders, so belike we'd better be returning to our command." They headed into the trees and soon were lost to sight.

WE withdrew sufficiently far to be inconspicuous, and sat down to rest. "You see how it is, Ted," Cynthia said thoughtfully. "Here we are with absolute pre-knowledge of what is going to happen—about Braddock's defeat, I mean—we warn him in plain words. But does it do a particle of good? No. He just gets mad and walks away. Washington knows the danger, but there's nothing even he can do about it. As for us—it's just as I said. We simply don't belong in this period. I don't believe anything we could do could possibly change the course of history the slightest bit from what it is to be, because, you see, it already was—at least to us!"

"I guess you're right, Cyn," I said. "But you've got to admit that this is a lot of fun. Look at that old sergeant over there. How funny he looks in that badly fitting red coat, and the green grass stains on the seat of his pants. Yet I bet he's a real hard boiled egg in his outfit. None of them seem to see anything funny about themselves, or dream that they look to us like a bunch of comic-opera soldiers."

"No," said Cynthia, "and the tragedy of it all is that before they know it they're going to get bowled right over, just like a bunch of comic-opera soldiers—all except the blood and the slaughter—and—and there isn't a single thing we can do to prevent it." She sighed. "Well, Ted, we ought to try to locate the time-car before the slaughter starts. There's no reason why we should get dragged into it. It's not our fight."

I agreed with her. But before we set out we paused to look at a command of Iroquois Indians trailing silently, grimly past, on toward the head of the column. Then a bugle blew, sergeants shouted commands, and the column of Redcoats formed quickly and marched off up the trail.

AS nearly as we could figure it, our time car must be some distance ahead and off to the right of the trail somewhat farther on. And we followed intending to strike off among the trees somewhat farther on. And we followed slowly, because we wanted to be alone when we came to the machine. There was no use in having an audience to witness our return to the 20th Century.

But we were not destined to accomplish our purpose as easily as that. A crashing volley of musketry was borne back to us on the wind. Wild yells in the distance. More musketry fire, a bit more ragged this time. The sounds were coming nearer. Blood-curdling war cries of the Indians. The screams of terrified and tortured men. Musketry fire swelling into an almost continuous roll, and coming nearer.

"The slaughter will center chiefly on the trail!" I told Cynthia. "Let's beat it, quick! Straight to the right, away from the trail! And don't forget we've got rocket guns. We'll use them if we have to!"

Away we went through the trees, keeping a sharp lookout to the left, in the direction of the French. The firing was more behind us now, and was resuming something of its volley character.

"That's George Washington's work!" Cynthia panted, as we ran. "You know he was responsible for rallying the troops and preventing worse slaughter."

But as though to belie her words a wave of Redcoats, in mad panic swept down on us from our left. Some were cursing. Some laughing hysterically as they tripped and ran. They hurled their muskets and cross belts away, tossed aside their headgear. Some staggered and fell. One held up a bloody hand transfixed by an arrow shrieking insanely: "The Red Hand of O'Neil!—See the Red Hand of O'Neil!"

There was no sense in what they did. There couldn't have been a large force of pursuers. But these proud regulars, the pride of the British army, had simply cracked under the strain of battle conditions to which they were not accustomed. For the moment they were not disciplined troops, but fear-crazed animals, running in horror from some deadly terror they could not see.

I dragged Cynthia behind a great tree which, flanked by a couple of smaller ones quite close to it, formed a natural shelter, and held her, trembling in sheer horror, while the wave of panic-stricken troops surged by.

As a matter of fact there were no pursuers. Not at the moment, at least. We ran from one to another of the fallen Britishers. They were all dead except one; and he died in our arms as we tried to relieve his suffering with water from his canteen.

"Well, Cyn, I guess it's no use hanging around here," I said as we stood up. "We know already how complete this victory is going to be. If we don't find that time-car pretty quick, we're not going to get back to the 20th Century at all."

"Oh, how horrible and bloody it all is," Cynthia said. Her voice trembled. "The way we read it in our school histories, it didn't seem like this at all, did it? Just to think! This poor fellow probably has a mother and father waiting for him on some peaceful English countryside, looking forward to the day when he comes home from the wars and—"

"Come, Cyn," I said, taking her elbow and steering her gently on through the forest. "It's all very sad and terrible. But there's nothing we can do about it. And we have to get back to that time-car!"

SEVERAL times we heard distant shrieks and cries; and two or three times musket shots. Once a party of Iroquois, allies of the English, crossed our trail ahead of us. We could see them slinking through the trees, glancing back occasionally in the direction of the French lines.

"That means the French or the Algonkins can't be far away," Cynthia said. "What do you think we better do?"

"I don't know. If we only knew exactly where the time-car is," I told her, "I'd take a chance and try to crash straight through to it. These are the days of solid shot, you know. Not even explosive artillery projectiles have been invented yet. So unless we met an overwhelming opposition we ought to be able to scare off Indians with the explosive bullets of our automatics."

In the end I decided to climb a tree and see if we could get our bearings that way. I selected the tallest I could find, and finally made my way to the top, though I am quite sure that, had there been any Algonkins in the immediate neighborhood, they would have been attracted by the commotion I made.

All I could see in every direction was forest. No—was I mistaken? Did I see a flash, as though of the distant reflection of sunlight on glass, way over there? I couldn't be sure, but we had no better guide. So carefully noting the direction, I descended, and we set forth cautiously in that direction, pausing every few moments to listen carefully.

"I think we've come about the right distance," I said at length. "Let's circle about carefully. Isn't that a clearing over there?"

"I don't know," Cynthia replied. "That outcropping of rocks is in the way. You can't see very well what is beyond."

We made our way to the little ridge, and as Cynthia anxiously watched me, I crawled to the top, and exposing myself as little as possible, looked over.

There was the time-car, just as we had left it. I could see it through the trees about two hundred yards away. And gathered around it, touching and thumping it in obvious amazement, were some two dozen Indians. Even at this distance I could tell from their headdress that they were not the friendly Iroquois, but Algonkins.

Cynthia crawled up beside me and together we watched, hoping the Indians would pass on in their pursuit of the British column. But they didn't. Instead, when they had gotten through thumping and scratching at the locked car, they proceeded to squat and stretch themselves on the ground as though waiting for something, or someone.

"Do you suppose they can damage it?" Cynthia whispered.

"I hardly think so," I replied. "Not with tomahawks, knifes and arrows. None of them seem to have guns. A bullet might crack one of the quartzine windows, but I don't think it would break it. They're pretty thick, you know. The only trouble is there's no telling what a bunch of fool Indians will do. Suppose they took it into their heads to build a great bonfire around it?"

Then suddenly the savages were on their feet. The white uniform of a French officer had appeared among them. They gathered around him, gesticulating and pointing at our time-car. He stood with folded arms, ignoring the machine with a great air of dignity.

At length he held up his hand with a dramatic gesture and said something. The Indians backed away and subsided. Then he turned and gravely inspected the car, giving no sign, that we could see, of surprise.

"He naturally wouldn't," Cynthia murmured. "That's one reason the French were so successful with the Indians. They knew how to put on an act with them. Look, Ted! he acts as though a time-car were an every-day affair with him! Maybe he'll order them to go away and leave it."

"Not he!" I said. "He's caught sight of the coils and gadgets inside. He'll try to devise some way of breaking into it."

I was right. The Frenchman slowly drew his pistol from his belt and examined the priming. He was going to try to shoot the lock. Not that he could have broken in that way. But he might have ruined it and prevented our ever getting it open. The time for action had come. I raised my gun and took careful aim at the ground some thirty feet this side of him.

I squeezed the trigger gently. The slight hiss from the muzzle was lost in the detonation of the tiny rocket-bullet where it hit the ground.

For a split second the Algonkins remained as though paralyzed, each in the position he had been in at the instant. Then, as though full of coiled springs, they leaped madly in every direction away from the spot where the explosion had occurred. The Frenchman had whirled and faced us, or rather the point of the explosion.

"Come, on, Cyn!" I cried. "We'll have to wade right into 'em!"

"Shoot at the ground in front of them!" she suggested.

We went over the top of the rock, shooting slowly and deliberately as we went, virtually laying a barrage down in front of us.

The officer shrank back from the terrific explosions and raised his futile pistol. But his shot went far wide of the mark as he staggered back, blinded from the approaching explosions, and threw his arm up before his eyes.

That lad had courage, though. The detonating bullets, which were somewhat more powerful than the old-fashioned hand-grenades of 1917, were something entirely beyond any war experience he could ever have had back in the 1750's. But he didn't turn and run. He just backed slowly away among the trees, calling back to his Indians to turn and face the music. I could have blown him to bits any time I wanted to, but I didn't have the heart. As Americans this might have been our war. But we weren't Americans of that period, and somehow I didn't feel justified in doing a thing more than was necessary to win our way back to our own century.

STEADILY we approached the time-machine. The Frenchman was some three hundred yards away now, taking advantage of the shelter of the trees. We only caught occasional glimpses of him. The Indians were completely gone, probably a half mile away by now.

Finally my gun just clicked. The magazine was empty. "Have you any shots left?" I called to Cynthia.

She nodded. "A few," she said.

"Then give him a final barrage," I said. "I'll open up the car."

I leaped to the door of the time-vehicle and inserted the key. With a sigh of relief I opened the door and turned toward Cynthia. Her magazine was empty too, and she was running toward me. A bullet clanged against the metal panel beside me. Frenchy was still in the game, and coming back at us. He had sensed that we had run out of ammunition, and was coming on the run with no attempt at concealment.

In we jumped, and I slammed and locked the door while Cynthia threw the power switch. Would those tubes never develop their blue glow? The officer was plunging toward us at full speed, sword in hand. He had thrown away his useless pistol.

Cynthia's hand trembled on the rocket-blast lever. I glanced alternately at the running Frenchman and the vacuum tubes. There was a faint glow in them now.

"Don't throw it yet!" I cautioned her. "Not till the tubes develop full glow. There's nothing he can do to us with that sticker of his, but if he gets too close the rocket blast will burn him to a cinder!"

He was still thirty feet away when Cynthia finally pushed the lever over. A blast of flame mushroomed out from under the car as we rose on it. The Frenchman halted short, staggered back and threw his arm up to protect his eyes. Then we were roaring aloft, with him standing there gazing up after us in amazement.

"I wonder if this will go down in history?" Cynthia said. "I don't remember reading of anything like it, do you?"

"Not much," I chuckled. "Just let him try to tell a story like this when he gets to Fort Duquesne or to Quebec! Who'd believe him?"

I pulled the time-gap switch.

"Well," I said as we drifted down over my laboratory on reduced rocket blast, and, in the good old 20th Century, "I like adventure, Cyn, but that was a little too hot for comfort."

"It was a little exciting," Cynthia replied, "but scarcely aesthetic. Next time let's pick a more picturesque period of history."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.