RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"Victory Adventure Book," Collins, London, 1916

THERE was dismay on Bob Silver's usually cheery countenance as he burst into the study which he shared with his chum Antony Lyle.

'I say, Tony, it's all up!' he exclaimed in a tone of despair.

Tony, a tall, dark boy, with a resolute face, looked up from his book.

'What's up, Bob?' Then catching sight of the other's expression, 'What's the matter, old chap?' he asked more seriously.

'Everything. I've just had a letter from Uncle Richard. He can't have us after all for these holidays. He has been called away to America by some horrid business. There's nowhere for us to go. Oh, Tony, we shall be stuck here at Meripit for the whole of the holidays!'

'It does seem like it,' answered Antony seriously. 'All our people being away in India makes it pretty difficult, doesn't it? Still, I've had to spend the holidays here before, and though it's pretty quiet, one can have some sort of a time.'

Bob gulped.

'I know, but I was counting on such a jolly good time this summer. Uncle Richard was going to give us some top-hole fishing, and he said there'd be a couple of ponies for us. It's beastly to get turned down at the last minute like this.'

Tony nodded. 'It is, old chap. But didn't your uncle suggest anything else?'

'No, but he sent ten pounds, and said that he hoped it would help us out.'

'Help us out—Tony paused and considered a moment. 'By jove, so it will. Tell you what, Bob. Why shouldn't you and I go off and get a bit of fishing on our own?'

Bob's eyes widened.

'What a ripping idea! But I say, Tony, ten pounds won't go far to keep the two of us for the whole seven weeks. We couldn't take rooms, let alone stay at a hotel.'

'Of course we couldn't,' answered Tony dryly. 'I wasn't thinking of that. But what about a tent? We could go and camp up on the moor where the fishing is free. We'd have plenty of money to hire a tent and buy all the grub we wanted. And we could get milk and butter from one of the farms. What d'ye think?'

'Think—why, that it's the most gorgeous notion I ever heard of,' declared Bob enthusiastically.

IT was only three days to the end of term. All their spare time during those three days the two boys spent in preparation for their excursion. They hired an old but sound bell tent in Tarnport for half a crown a week; they bought tea, sugar, bacon, and a good stock of jam and tinned stuff. They got four old army blankets very cheap, and these and other odds and ends they arranged to have sent by rail up to Moorlands station on the moor.

Tony did most of the business part. He was a year older than Bob, and, though not so square and sturdy, was much more practical.

Early on the morning of breaking-up day they started, and by eleven o'clock were stepping out of the train at Moorlands station.

'My word, this air smells good!' said Bob, sniffing the keen breeze with much appreciation. 'Where are we going, Tony?'

'Out Stonebrook way. Farmer Cornish is going to drive us. Ah, here's the trap.'

A weather-beaten moorman had just driven up, with a rough pony in the shafts of a two-wheel trap.

'Jump in, young gents,' he said. 'I got all your stuff in already.'

They did not waste much time in doing so, and Cornish drove them straight out to Bear Hill Farm, where they made an excellent luncheon on pasties, cider, and cheese. Then they went out prospecting for a good site. It was not long before they found just what they wanted—a sheltered hollow set amid the heather-clad hills. It was not far from the brook, yet high enough to be fairly dry. By nightfall they had got everything to the spot, had set up their tent, and, lighting their fire, contentedly cooked their supper.

'We'll have trout to-morrow, Tony,' said Bob, as he finished his last mouthful of bread and jam. 'The water's just about right. I say, this is fine, isn't it? No one to bother us and—'

'Hallo, who's this?' he broke off sharply, as a tall figure strode suddenly into the circle of firelight, and, stopping short, stood towering over the boys.

'What are you doing here?' demanded the visitor harshly.

For a moment the two stared up without answering. The newcomer was a most curious-looking personage. His face was thin and haggard, his eyes, very large and dark, reflected the firelight in the strangest way. His hair was longer than usual, and he had a rough beard and moustache. His clothes, too, were old and much worn; yet they looked as if they had been cut by a good tailor. Neither of the boys had ever seen any one in the least like him before.

'What are you doing here?' he asked again.

'Camping,' answered Tony quietly.

'Camping? You are spying. Clear out at once. I won't have you here.'

The boys exchanged glances.

'Mad,' was the word Bob's lips formed.

Tony answered. 'We are not spying or anything, sir. We are just fishing. We thought this was open moor, free to any one.'

'It is not. It is my leasehold. You will go at once. Do you hear?'

Tony thought it best to humour him.

'I am sorry we are trespassing. We didn't know. But surely you will let us stay here to-night?'

'Not another minute. How do I know what you may be doing in the dark? You were sent here by Mannering. Don't deny it.'

'I never heard of the gentleman,' answered Tony. 'We come from Meripit.'

The other glared. 'I don't believe you. I know Mannering's tricks. Clear out now at once.'

Tony got annoyed at last.

'Look here, sir. We have no proof that you own this place. What is your name?'

'Grattan—that's my name. You don't believe I own the ground? I'll soon prove it. One of you come to my house and I will show you my deed. Ah, even Mannering can't steal that from me.'

Tony turned to Bob. 'I'm afraid we've got to move,' he said, biting his lip.

'Where to?' growled Bob, very much annoyed.

'You can go anywhere above the stone wall half a mile north of this,' answered Grattan with unexpected civility.

'Can't we stay here to-night, sir?' asked Tony. 'It's pretty late to make fresh camp. We will shift first thing in the morning.'

'No,' answered Grattan sharply. 'You must go now.'

There was no help for it, and the two began to pack up and strike tent. It was pitch dark and very chilly when the two boys, tired out and cross, crawled into their blankets in a hastily pitched tent on the high ground to the north.

WHEN daylight came they found that the new camping ground was exposed to every wind that blew, and the worst was that there was no shelter except on boggy ground down by the brook.

'This is rotten,' said Bob, looking round disconsolately.

Tony frowned. 'What beats me is what on earth Grattan wants with such a desolate patch of moor.'

'And who's Mannering?' added Bob. 'And why is Grattan so hot against him?'

'Tell you what,' said Tony. 'We'll go up to Bear Hill for our milk, and ask Cornish. He'll tell us.'

Cornish gave a great laugh when he heard their story.

'Too bad,' he said. 'I'd ought to have told you about Mr Grattan, but I didn't ever think he'd kick up a rumpus. He's got the lease all right. Mining lease it is. 'Tis the old Heelbarrow Mine, and he's got some notion in his head as there's good ore there.'

'Is he working it?' asked Tony.

'No. Seems he ain't got the money.'

'And who's Mannering?' added Bob. 'And why's Grattan so hot about him?'

'Mr Mannering lives over to Torcrest. A rich man he be. But what the trouble is atween him and Grattan I don't rightly know.'

'Then I suppose there's nothing for it but to stay where we are?' said Tony.

'Not unless you likes to camp in my newtake. But I reckon that's a bit far from the river, ain't it?'

'It is,' said Tony. 'Thanks all the same. Come on, Bob. Let's get our breakfast and make the best of it?'

Fried eggs and bacon did them both good, and, as the day was fine with a soft westerly wind, they got their rods out and started to fish. As they did not want any more trouble about trespassing they went upstream.

THE air was delicious, the sun bright and warm, the hills were purple with heather, and as the fish were coming well the two soon forgot their troubles, and began thoroughly to enjoy themselves.

About a mile up they came to a long deep pool with a waterfall at the top. Bob took the lower end. Tony began to put his flies across the top.

Bob heard a shout.

'Hi, Bob. Landing net. Quick! I've got a beauty.'

Bob dropped his rod and ran. He saw a fine trout of nearly a pound leap high out of the broken water. The line was screaming off Tony's reel. Again and again the fish jumped, shaking his head furiously in an effort to free himself from the hook. Bob sprang out on a rock with the net ready in his hand.

Five minutes' desperate excitement, then at last Tony managed to work the fish in close to his chum. Bob slipped the net under, and with one quick flick flung him out

'My hat, but he's a whopper!' he exclaimed as, after killing the fish, they stood over him, gloating on the crimson-speckled beauty. 'Prime condition, too!'

They were so interested that they never noticed a curious drumming noise until it was close upon them. Suddenly Tony sprang to his feet, and glanced round.

'Look out, Bob!' he yelled. 1 Look out!'

Bob looked, and saw, not fifty yards away, a whole herd of a score or more of Highland cattle charging down upon them. Their shaggy heads were carried low. Their savage eyes glowed. They were coming straight at the boys.

'Follow me!' cried Tony and made a leap for the rock upon which Bob had been standing when he landed the fish. From that he jumped to another farther out.

Bob followed, and the two reached a great, smooth granite boulder, which reared its gray head from the centre of the pool, just as the old bull which headed the herd came dashing into the edge of the pool.

'The brutes!' muttered Bob breathlessly. 'I say, Tony they're coming after us.'

It was true. The bull was wading out, snorting furiously as he came. The others stood upon the shore, tossing their heads and bellowing.

Tony waited until the bull was almost up to their rock. Even then he was not swimming. His long sharp horns were within a yard of their legs.

'We'll have to take to the water,' said Tony 'Come on.'

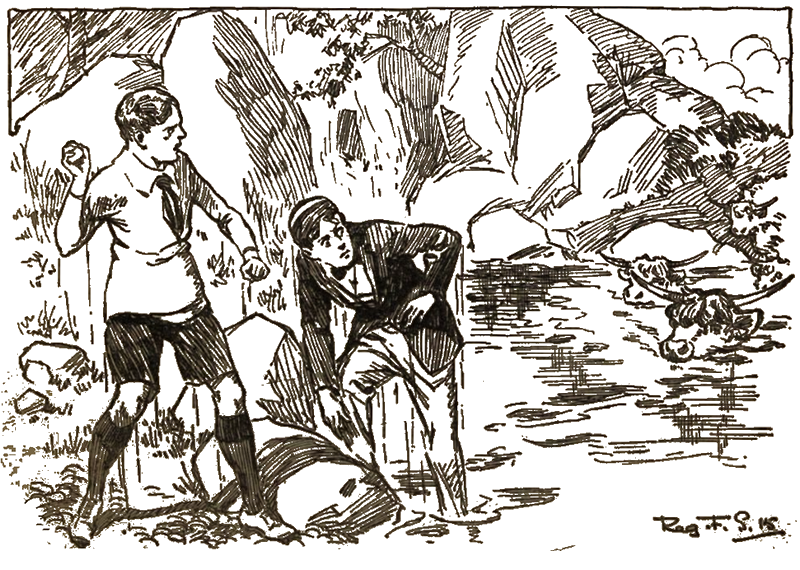

He sprang in nearly up to his shoulders, and Bob followed. They struggled across and gained the opposite bank, which was of peat and about a yard high. Here they thought they would be safe, but nothing of the kind.

The bull came swimming after. The boys stoned him vigorously, but could not stop him. What was almost worse, the rest of the herd were in the water forging their way across.

The boys stoned him vigorously, but could not stop him.

Arms in, heads up, the two boys ran side by side, sprinting for their very lives. But the ground was fearfully rough, all covered with matted heather and loose stones. The herd gained rapidly.

'If we could only get to that steep place!' panted Bob.

'It's no use. We'll have to run for it,' said Tony rather breathlessly. He realised that they were both in very considerable danger.

The ground rose beyond the brook, but not very steeply. Before they had gone more than a couple of hundred yards the whole herd were thundering in pursuit

'They'll have us first,' answered Tony grimly.

The rattle of the troop came nearer every moment. The two boys were nearly done. Bob stumbled, but Tony saved him from falling.

'Hi! Hi-yi! Hi!' It was a most extraordinary yell that suddenly rang out quite close at hand, and all of a sudden a man shot up like a jack-in-the-box from behind a clump of furze, only a few yards away to the right, and, waving his arms frantically, rushed between the boys and the cattle.

Instantly the whole of the herd swung off after him, as, running with amazing speed, he went straight off at right angles to the course the boys had been taking.

'He's mad!' gasped Bob, choking.

'Go on, you two! Go on!' waved the man, glancing back over his shoulder.

'Get on. I'm all right!' he shouted again, as they still hesitated.

'He means it. Come on,' panted Tony.

They dashed on and gained the rocky place in front. They scrambled up a few yards, then paused and looked round. A most extraordinary sight met their eyes.

The man, whom they saw now to be Grattan, was standing coolly in the middle of a hollow covered with reeds and rushes. The cattle were all around him, but not very close. They kept plunging forward, then stopping as if afraid to advance. They were bellowing with rage.

'Why—what—?' began Bob.

Tony burst out laughing.

'Don't you see? It's a bit of bog he's on. It will hold him, but not the cattle. I say, that's smart.'

Grattan waved to the boys. Then he shouted.

'When you have got your wind back, one of you come down and draw them off. No hurry.'

'All right!' came Tony's answer, and at his voice the cattle tossed their heads, and two or three faced round.

Tony deliberately climbed down, and, going a few paces from the foot of the cliff, began dancing about and shouting at the cattle. It was not long before these tactics proved successful. First, the old hull wheeled, and made a fresh charge, then the rest came galloping furiously after him.

Tony waited until they were pretty close, then made a run and a scramble, and with Bob's help was soon on a ledge well out of reach.

'Now we'll get a bit of our own back,' chuckled Bob, and, picking up a stone, let the ugly-tempered bull have it well between the horns. It drove him nearly mad, and he raged up and down, making frantic efforts to charge up the bank. But it was too steep, and he fell back every time.

Meantime the boys sent down a regular rain of stones, and kept the herd really busy whilst Grattan, jumping coolly from tuft to tuft, got out of the bog, and, making a wide circle, came over the top of the bank behind the boys.

'That's enough,' he said. 'Better come along up now.'

'Thanks, we will,' answered Tony. But, when they got to the top, Grattan was gone. They could see nothing of him at all.

'He is a queer bird!' exclaimed Bob.

'He certainly is,' agreed Tony. 'But anyhow he saved our lives for us. Now let's circle back and see if we can get our rods without those brutes spotting us again.'

They managed this in safety, and went back to their camp.

'Hallo!' said Bob, as he entered the tent. 'Some one has left a letter for us."

A sheet of paper was pinned to the centre pole. Tony took it down.

'You can fish in the water from Heelbarrow down. (Signed) Theodore Grattan,' was what he read.

'Short,' said Bob.

'But very much to the point,' answered Tony 'He's not such a bad old bird after all. Just a bit loony on one point. Tell you what. Let's take him some fish tomorrow if we can get any.'

IT blew that night, and twice they had to go out and tighten the tent pegs. It was very cold and uncomfortable, and they both wished devoutly that they had a better camping ground. However, the wind dropped towards morning, and after breakfast they went off to take advantage of the new bit of river.

It was better than the upper water, and they did very well. By three in the afternoon, when the fish seemed to have stopped rising, each had a pretty good basket, so, putting up their rods they started off to find Mr Grattan's residence.

It lay in a sort of gorge running back from the river valley, a savage, gloomy place with steep sides covered thickly with screens of loose granite. In one place a great mound of reddish rubble was piled thirty feet high, the dump from the old mine.

A house stood beyond this, an ancient square building made of huge blocks of lichen-covered granite.

'What a place to live in!' said Bob. 'Why, it's got hardly any roof!'

'That's not it,' answered Tony. 'See, there a little wooden bungalow beyond.'

'Ah, that's more like it,' said Bob. 'I wonder if he's at home?'

They waded knee-deep through the heather which grew almost up to the door, and Tony knocked. After a minute's pause, the door opened, and there stood Mr Grattan.

He did not speak, but stood glaring suspiciously at the boys.

'We brought you a few trout, sir,' began Tony courteously. 'I hope you will like them. And we wanted to thank you for taking off the cattle yesterday. We should both have got killed but for you.'

'Hm, you ought to have been looking out for them,' grunted Mr Grattan. 'Any one would know they were dangerous.'

'We didn't even know they were there,' explained Tony as he took half a dozen trout out of his creel.

'Come in,' said Mr Grattan. It was a command rather than an invitation. 'Like some cider?'

'Very much, sir,' answered Tony with a smile.

The door opened straight into a little sitting-room. It was much better furnished than the boys had expected. There were some nice pictures, good arm-chairs, and neat matting on the floor.

Their host went into the other room, and came back with a jug of cider and glasses.

'Your very good health, sir,' said Tony raising his glass.

'It's a long time since any one has wished that,' said the other dully. 'There are some would be glad to see me dead.'

'We're not among those, sir,' answered Tony with a smile.

'No, I believe you are not. I took you for spies of that scoundrel Mannering at first.'

His face darkened as he spoke. He looked positively savage.

'We never heard of the gentleman until Farmer Cornish mentioned him,' said Tony.

'And what did Cornish say?'

'Precious little, sir, except that he was a rich man and lived at Torcrest'

'He's a swindler—worse than a swindler; he'd murder me if he dared,' said Grattan violently.

'Ah, you think I'm crazy,' he went on, with a shrewd look at the boys. 'I can tell you better. Listen to me. I own the lease of this old mine. I bought it because I know that there is good ore left, and that it will pay to work it. But I am a poor man. I had no money to pay for the working. I went to Mannering and asked him to lend me enough to open up the old workings. He promised to provide money in return for a partnership. His terms were very hard, but I agreed. The papers were drawn up and I came to live here.'

He paused, then went on with a snort of disgust.

'Bah, I was a fool to trust him. The next thing was that he refused to put up the money. He offered to buy me out. He had the insolence to offer me five hundred pounds for what is worth at least twenty thousand.'

'But can't you get some one else, sir,' suggested Tony.

'No. Because I am tied by the agreement I have signed. He and his lawyers have tricked me. I am bound hand and foot'

'Well, he can't get the ore if you can't. That's one comfort,' put in Bob.

'You are wrong, boy. He is starving me out. I am almost at the end of my resources, and he knows it. Next Christmas I shall be unable to pay my ground rent to the Duchy. Then the lease lapses. Mannering will take it over, and I—I shall be ruined!'

He spoke with a bitterness that made a deep impression on the two boys.

'That's rotten luck, sir,' said Tony. 'I wish we could do something to help you.'

'Hm, you're not bad fellows,' said Grattan. 'But I've talked a deal too much. Go back to your tent and forget it.'

But neither Bob or Tony was likely to forget what they had heard. They talked of it a lot that evening and afterwards.

THE next few days were very bright and hot The water ran low and clear as glass. Fishing went off, and they amused themselves with long tramps in various directions.

A week passed, and they had seen nothing of the hermit, as they called Mr Grattan.

Then came a night with a strong cold wind, and they sat in their overcoats over the camp fire.

'I wish to goodness the hermit had given us leave to go back to our first camping ground,' grumbled Bob, pulling up his coat collar. 'This is rotten. I think I shall turn in. It's the only way to keep warm.'

'Yes, the wind is cold up at this height,' agreed Tony. 'All right. Let's rake the fire out and turn in.'

Ten minutes later the fire was out, and the boys were snug in their blankets. Bob was soon asleep, but Tony lay listening to the moaning of the wind over the hills.

Suddenly he sat up.

'That wasn't the wind,' he muttered. It was steps.'

He crept out quietly. It was not dark, for there was a moon behind the thin haze of cloud. He heard the steps again, and presently made out the figure of a man walking along the fisherman's path by the brook. At first he thought it was Grattan, but presently saw that the man was much shorter and squarer in build. He noticed, too, that he walked with a slight limp. He stopped just opposite the tent, then turned and crept up to it. Tony slipped silently back and lay down. He wanted to know what was up. The man trod softly, and Tony's heart beat rather faster than usual as he realised that the stranger was actually peering in through the flap. He was just going to spring up, when the man turned and went away again. As soon as he was back on the path, Tony roused Bob, and told him.

'Get your boots on,' he said. 'We've got to follow the beggar. I'll lay he's up to some mischief.'

Bob was all agog in a moment, and presently the two boys, each armed with a stick, were creeping away in pursuit of their mysterious visitor.

Presently the two boys were creeping along in pursuit.

They followed him down the river until they came opposite the old mine. Then he turned up the gorge, and was lost to sight among the thick gorse and boulders.

'He's after Grattan,' whispered Bob in high excitement.

*I believe you're right,' agreed Tony. 'We'd better warn Grattan anyhow. But go quietly. We might collar him with luck.'

Bending double, they went quickly along the path leading towards the mine. They had passed the dump and were in sight of the bungalow, when Tony suddenly gripped Bob by the arm.

'Look!' he muttered. 'Look!' He pointed as he spoke up the valley.

A couple of hundred yards beyond the mine house, a small spot of crimson light had suddenly appeared. It rose almost instantly to a brilliant flame, which bent under the whip of the wind, and then began leaping along the ground.

'Great Scott!' gasped Bob. 'He's fired the heather.'

'Yes, and he's doing it farther on. See, there's another flame. Come on. We must stop that. The whole place will be burnt out,'

Both started running as hard as they could go, and just as they reached the spot a third fire started. As the flame flashed up they both, by its light, distinctly saw a big heavily-built man in a dark suit rise to his feet and run straight away up the valley.

'Whoop!' shouted Bob, rushing in pursuit.

'Steady, Bob!' cried Tony. 'Let him go. Our job is to put the fire out. Grattan will be burnt out if we don't. Here, you go and rouse Grattan. I'll try and beat it out.'

Bob raced back towards the bungalow; Tony whipped out his knife and cut a green branch from a thorn-tree, and set to work on the burning heather.

It was too late. By the time he had beaten out the first blaze the second and third were quite beyond him. The heather and gorse, dry as tinder, were turned into torrents of crimson flame. Sparks flew in crackling showers, and the rocky sides of the grim gorge glowed in the tremendous flare. Driven by the wind, the blaze travelled straight down upon Grattan's wooden bungalow.

Tony saw that the only chance of saving the place was to start a back-fire—that is to burn off the heather just around the house so as to leave no food for the first fire. He turned and ran back swiftly.

There was no light in the windows, and to his amazement he saw no sign of Bob. He pounded frantically on the door, and out came Grattan in trousers and shirt.

'What's up now?' Then as he saw the fire, he gave a horrified exclamation.

'I'm done for,' he groaned.

'No, not yet,' answered Tony. 'Here give me some matches. We can burn back and save the building, and I want two wet sacks.'

Grattan had sense enough to see that the boy knew what he was about. The matches and sacks were produced in minute.

Tony handed him one sack, and took the other.

'I'm going to light here at the corner,' he said quickly. 'You go to the other. You must burn a belt at least six feet wide. Beat it out as it burns. Quick as ever you can. We shall have to work hard to do any good.'

Work they did. The next ten or fifteen minutes were one breathless, furious fight. The heather was like tinder, and the gusts blew sparks in every direction. And all the time that they were burning around the building, the main fire was racing down on them, lighting up everything with its crimson glare.

There was no sign of Bob. Grattan had seen nothing of him. As Tony wielded his wet sack, pounding away frantically at the ever-spreading flames, he kept on wondering what could possibly have become of his chum. He longed to go and look for him, but knew that, if he left this work for a single minute, the dwelling was doomed.

The heat increased every moment. Clouds of pungent smoke swept down, stinging his eyes, making him cough and choke. Red tongues of fire leaped through the heather.

The fire was on them. Sparks rained on the bungalow. If it had not been for the space which they had already burnt clear, nothing could have saved the building. As it was, the woodwork was smouldering in half a dozen places, and, but for the fact that Grattan had water laid on from the old mine on the hill-side, the place must have been burned down.

Tony carried one bucket after another, and splashed the contents against the walls. He was dripping with perspiration, and aching all over with the strain.

At last the smoke thinned, and he took a moment to look round. To his intense relief, he saw that the long, red line of flame was already well past, and sweeping away down the gorge.

'We're all right, Mr Grattan,' he shouted. 'The house is safe.'

'Yes, thanks to you, my lad,' answered Grattan warmly.

'And now I must find Bob,' said Tony quickly. 'I can't think what has happened to him.'

'I hope no harm has come to him,' Grattan replied. 'Go on. I'll be after you in a minute.'

The clouds had blown away, and the moon threw a clear light on the black, smouldering desert, which an hour before had been a mass of thick heather, moor-grass and gorse.

'Bob! Bob, where are you?' shouted Toy as he worked to and fro across the burnt ground.

'Here! Here I am, Tony!' came the answer in a curiously muffled voice. Tony stared all about, but could see nothing.

'Here in the hole. I can't get out,' came Bob's voice again.

A moment later Tony was standing on the edge of a narrow cleft in the ground. The top was not a yard wide, but it seemed to open out below into a regular chasm. He heard a scuffling sound from the depths.

'Are you hurt?' he asked anxiously.

'Bit bruised,' came the gruff reply. 'You'll have to get a rope, old man. It's beastly deep. The top was all hidden with the heather. I never saw it till I fell into it.'

'All right. Wait a jiffy.' Tony ran back, and in less than two minutes he and Grattan were at the spot with a rope and a lantern, and very soon Bob was hauled safely out of his subterranean prison.

'The bottom's all stones,' he said, as he ruefully rubbed his bruised knees. 'A great pile of small stuff. Looks as if some one had been hiding road metal there. Well, I'm jolly glad you saved the house anyhow.'

'Small stones, you say?' exclaimed Grattan with sudden interest. 'Here, hold the rope. I'm going down.'

He slipped over the edge and dropped lightly into the dark pit.

'Give me the lantern,' he said sharply, and Tony handed it down.

Next moment came a shout which made both the boys start.

'Got it—got it at last,' Grattan cried delightedly, and presently came scrambling out of the hole. His eyes were shining, his face glowed with triumph. He took a couple of dark-coloured lumps of stone from his pocket, and held them out for inspection.

'Why, I thought you'd found a gold mine,' said Bob in a very disappointed tone. 'What good are they?'

Grattan laughed. 'They're the ore, my boy—the ore, and rich as they make it. And there are tons down there. I don't know who hid it, or how, or why, but there it is—tons of it. I can sell this for cash, and carry on and open the mine. You two have done me a better turn than you have any idea of.'

'I'm jolly glad of that,' answered Bob. 'All the same, it was really the chap who tried to burn you out that did it'

'The man who set the fire. Did you see him?' exclaimed Grattan eagerly.

'We did,' said Tony, and described him, Grattan chuckled delightedly. 'Why, it was Mannering—Mannering himself. Oh, we've got him now. With your evidence, he'll never dare go to the; courts. I'll make him tear up his agreement altogether. I'll run the whole thing myself.'

He paused, then went on in a different tone.

'Here, you two come back to the house. You'll want a wash and something to eat And, see here, you'd best come and put up with me for the rest of your stay on the moor. There's plenty of room, and I shan't bother you. Will you come?'

'Rather!' answered Bob and Tony in one breath.

MR GRATTAN proved himself an ideal host, and the boys enjoyed every minute of their stay. Before their holiday was over the gorge was already busy with workmen, and Mr Grattan himself seemed to grow younger and more cheerful every day.

When the last day came, and Cornish's cart waited to take them to the station, their host bade them a warm farewell, and, just as they were going, slipped an envelope into Tony's hand.

'Don't open that until you get to the train,' he said with a smile.

When Tony did open it he found that it was an agreement, making him and Bob partners in the Heelbarrow Mine, each to have one twentieth of the profits.

That was two years ago. To-day their shares are enough to pay their school bills and to give them a better allowance of pocket money than any other boys a Meripit.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.