RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Astounding Stories, May 1935, with "Faceted Eyes"

"THE impact of X-rays upon the genes changes either the genes themselves or the pattern of their arrangement in such a way as to produce these mutations," Dr. Miller explained to me as he led the way, through a maze of fruit-fly cultures, electrical apparatus and miscellaneous biological equipment, to his untidy desk. We were in the huge genetics building shortly completed by Southwestern University, primarily to house and do honor to Miller's work in this field.

"My early studies showed that Drosophila could be made to change his characteristics along certain lines," he continued, gesturing to photographs on the walls. "We could change his bristles, his body markings, and so on. All this work was just childish exploration."

(It had won him a place as the ranking geneticist of North America!)

"My recent work, which I shall publish next month, will revolutionize our ideas of heredity, of the role of genes and the cytoplasm, our prospects even of eugenic control of the human racer!"

"Look," he continued, drawing me to a series of vastly enlarged photographs. "What would you say to a fruit fly with only four legs?"

"But," I expostulated, "it has always been thought that the phyletic structural characteristics were controlled through the cytoplasm, not through the genes."

"Exactly," was the answer. "But I have succeeded in screening my radiations or modifying them in such a way —to be entirely frank, the physics of the thing is still not plain—as to change the obscure molecular or crystalline structure in the cytoplasm and thus overturn the entire concept of cytoplasmic continuity!"

The pictures were things of bizarre appeal. Almost one would have thought they were faked; at least, one familiar with the traditional ideas about the limits of radiation-induced mutations. Here was a fruit-fly that clearly had only one eye, an enormous multi-faceted gem. Flanking it, another seemed to have overleaped the body segmentation so characteristic of the insects, having a one-piece body and legs jointed only at the hip and knee.

"Here is a real beauty," Miller interrupted my gazing, "I had a permanent exhibit made of it because of its unique mutation."

On the wall, protected by a sealed heavy glass case, was a delicate mounting of one of his specimens, fronted by a magnifying glass so that it was always on display.

"Why," I gasped, "it has the inner structure of a mammal." It was obvious, even to a hasty inspection, that here was an insect possessing organs never associated with its class. The reproductive system was entirely alien to that with which I was, in my status as an instructor in elementary biology, vaguely familiar. On the other hand, it had no indication of assuming a vertebrate skeletal type.

"This beauty"—Miller, a scientific aesthete, always referred to his best specimens as beauties—"first set me on the track of my most radical experiments. I had found a critical range of frequencies within which cytoplasmic mutations generally occurred. Now, by systematically varying the temperature and length of radiation, I find that there is a set of optimum conditions at which every mutation follows the same general rule!"

He paused, and I took my cue. "Yes," with an attitude of expectation, "what was this general rule?"

"Every mutation at these conditions was a change which could only be described by saying that the insect was trying to become human!"

Naturally, I protested this. I accused Miller of letting his imagination run away with him. I even gently insinuated that he should take a vacation, go up to his cabin on the Guadalupe River headwaters and take a long rest. He fumed and fretted, but finally seemed to make a difficult decision.

"All right," he said, "I'll show you. I've been intending to destroy the thing, but if I keep an eye on you, I don't believe it can harm you, and then you will be a witness that it was actually alive. Otherwise, heaven knows what chicanery I'll be accused of!"

MOVING to the stair door, he began to open it. I was surprised to see that it was fitted with a heavy four-letter combination lock and the door had been reinforced with steel insets, although it was already a heavily-paneled oak door. Without explanation, he led me down steel stairs to a basement room without windows. In a corner an iron-barred cage contained what seemed to be a well-grown gorilla.

"Why, Newt, I didn't know you went in for keeping—" I began, when he shut me off abruptly.

"Don't look at the eyes! Understand? Don't—look—at—the—eyes!"

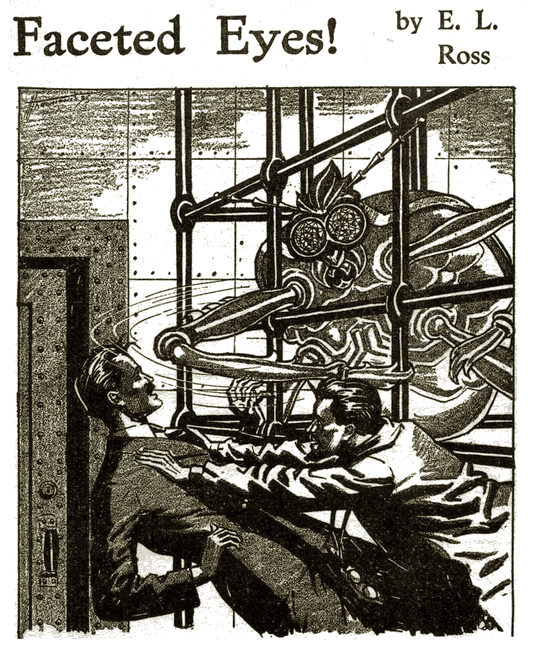

But this instruction was my undoing. I scarcely got an impression of the rest of the creature. For my gaze swung involuntarily to the eyes and could not leave them. They were great, glowing hemispheres, many-faceted after the fashion of insect's eyes, but staring with an intense concentration that struck me like a physical blow. In those eyes I saw a giant brain striving for knowledge, and an organism struggling up from the abyss—the ceaseless quest of life for greater and greater complexity, the unending drive toward superiority, the vast, unread history of an evolution deeper and wider than our biologists had ever dreamed of—the pettiness of human knowledge, and the futility of human minds

I was knocked to the floor by the impact of Miller's charge as something like a heavy brown club whistled through the air at the level my head had occupied.

"Thank Heaven I came to my senses in time," he gasped. "If that—that—arm had struck you, you'd been brained!"

I could scarcely comprehend what had happened. Rapt in my concentration on the shining eyes of the beast, I had walked right up to the cage and, but for Miller's timely assault (delayed because he, too, had momentarily fallen under the spell until I walked into his line of vision), would have been brained by the monster within. My stomach squirmed at the thought of my narrow escape. We had, of course, scrambled back out of reach of the deadly swinging flails and carefully avoided looking into those menacing eyes.

"Hypnotic mirrors," I exclaimed half-unconsciously. "They work just like the mirror devices used in some hypnotic experiments Hill has been doing in the psychology lab. But much more effectively—because of the infernal glow they have, I suppose!"

Sobered and convinced by Miller's demonstration of his weird mutation from a harmless fruit fly, I followed him back up the stairs to the main laboratory. Here a hasty conference quickly brought us to a decision to destroy the monstrosity at once. Miller explained that he had had a narrow escape once before—hence his precautions to keep the beast in, and others out— but that he believed the hypnotic effect much stronger than before; practice or mere growth. We might have stopped to debate the old problem of heredity vs. environment, but the situation called for action. I recalled my .45 automatic locked in a cabinet across the quadrangle, and left to obtain it. Neither of us thought that this might be a hopelessly inadequate weapon!

Out of breath from my dash to South Hall and back—I'm not so young any more, I guess—I rushed into the laboratory to come upon a scene of havoc and confusion. A huge X-ray apparatus had been smashed by blows as of a crowbar. Elaborate glass structures, fine wiring grids and connections had been swept as by a huge broom from the tables to the floor, and crushed. The lab was a scene of utter chaos.

The door to the stair was open. A full-length window had been pushed out of its frame.

My heart stopped in panic. I knew what had happened as if I had seen it. Miller must have gone downstairs while I was away! I dared not think further, The thing was loose. That incredible thing which must not live. It was too big to move fast—but—

Trusting that the monster had gone out the window, I dashed down the stairs to find what I knew was there. Newt's body was literally smashed to a pulp. By what ruse the beast had gotten his attention, compelled him to open the combination lock on the cage door and thus escaped, I was never to know.

THERE was no time for grief and less for speculation. Somewhere on the university campus a destructive machine of remarkable potentialities was on the loose. It was essential that I do something to stop it, and to warn others. It took minutes—or so it seemed—to get police headquarters on the phone

"Hello! Sergeant? Warn your men near the university that a dangerous animal is loose. About the size of a gorilla. Tell them to shoot to kill!" I hung up, frantic to go out and exterminate the thing. By my failure to warn the police of its eyes, I was the unwitting murderer of two brave men. I found their bodies as I raced about the campus; each had died without firing a shot.

Remembering its peculiar heredity, I sought in vain for a clue to its instinctive activities which might help me find it. Chance came to my aid. Running into a narrow, dimly lighted passageway between two buildings, I saw the monster's bulk just vanishing at the other end. Reckless, I dashed after, but reason came to my aid and I paused, looking round the corner before turning. The beast had its back to me, as it crouched behind a bank of shrubbery. Taking careful aim at the point which I thought would correspond to its heart —though realizing that this creature might be constructed on unheard of lines—I pressed down the trigger and held it. Then I saw that which brought terror to my soul—the heavy, steel-jacketed slugs, traveling a distance of less than twenty feet, glanced off the hard, chitinous armor as if from a battleship. In utter despair I fled as the huge brute turned and lumbered slowly in my direction. Thank Heaven it had none of the speed of movement of most insects!

Having distanced the thing, I stopped to look about in desperation. To my ears came the welcome siren of a squad car. I ran to the drive where they must enter the campus. There was a machine gun in the car and we decided to try this against the armor-plated enemy.

It failed. By dint of carefully keeping my eyes on the ground and hitting one of the policemen a terrific blow on the cheek when he lapsed into the hynotized stare and started walking robotlike to death, I saved our forces without loss—but also without victory.

The situation was becoming desperate. We considered hand grenades and high explosives, but left them as a last resort because of the buildings and delicate equipment of the university. Poison gas was discarded as too dangerous and perhaps unsuccessful. We could not take time to experiment on Drosophila in search of an effective gas!

Then I had another brilliant idea. "Sergeant Wilton," I called to the head of the police squad, "since the eyes of this thing are its best weapon, can't your men stay at a suitable distance and shoot them out? Keep one man with his eyes averted by each man who is to shoot. Maybe this will work!"

Did the hellish monster hear and understand my words? Or did it add clairvoyance to its devilish hypnotic skill? Try as we would, we could not lure the beast into a position where the group could shoot at it. It had backed up into a kind of L-shaped court from which no escape was possible, but where we could not attack without incredible danger.

We were at an impasse. Starving the brute out might take weeks, for its peculiar metabolism was unpredictable; and even though this was the summer vacation and the campus was relatively deserted, we could not take chances on having the thing escape again and perhaps reach the town.

It was while I desperately reviewed all my memories of this hectic day, trying to hit upon the weak spot—the Achilles heel, of the monster—that the flash of insight came to me. "Its eyes are like hypnotic mirrors," I had exclaimed. Hypnosis—the control of one man's behavior by another. Instantly I had formulated a new plan of attack.

On the telephone I learned that Clark Hill, the country's greatest expert on hypnosis and suggestion, was in his laboratory. To find him, explain the horrible situation, describe my plan, enlist his cooperation, was the work of minutes. If he had been skeptical, much time might have been lost—but he had seen some of Miller's lesser marvels of mutation.

I insisted on being the subject, both because I was a first-rate pistol marksman and also because I felt myself to blame for the deaths of two policemen already, and wanted no more blood on my own head. Hill, intrepid scientist, dared to go with me. It was necessary that he should, but I would not ask him. He insisted.

Placing me in a comfortable position—if that is possible on the stone bench we used—Hill proceeded to hypnotize me. The method he used was simple direct suggestion, familiar to all students of the science. The rest of the story I describe as it was related to me afterwards.

"You have often shot at electric light bulbs for fun," Hill stated to me when I was in the hypnotic trance. He knew this to be true. "Now I am going to show you two glowing bulbs and I want you to shoot them. You will shoot very calmly and carefully. You must not miss! You will remain absolutely under my control at all times. You can have no thoughts, make no movements, except those I permit you to make.

"Your only thought is to be of shooting out those light bulbs. You will think of nothing else, do nothing else."

Reloading my automatic, we crept forward until we reached the corner of the L. Hill re-emphasized his hypnotic instructions; we rounded the corner. Hill, despite my warnings, could not overcome his scientific curiosity. Specialist in hypnosis, he wanted to see with his own eyes this weird freak of laboratory science collaborating with nature which possessed such supernatural powers.

My gun halfway to a level, it paused: I had been instructed to shoot the light bulbs—but now something was between me and them. I could not see my targets. One of the minor miracles of the day happened just then. Hill, walking the machinelike walk of the monster's victims, found his progress blocked by a pile of ashes and rubbish which had just been shoveled from a basement window. Still facing the thing, he walked sidewise to avoid the obstruction.

At last I could see my targets. My gun, already in position, spoke rapidly. The bulbs, glowing brightly in the dim light, were extinguished. Hill suddenly reverted to normal consciousness within six feet of one of the most deadly monsters ever to walk the face of the earth —but a monster deprived of its most dangerous weapons. He beat a hasty retreat.

The thing, blinded now, huddled in a corner by the court. Like Samson, it was still too powerful for direct attack. A fifty-pound iron bar, dropped from the four-story building's roof, penetrated the armor, paralyzed the giant nervous system. A squad of policemen, augmented by ourselves and a couple of frightened janitors, improvised a battering ram and applied the final stroke by breaking the huge neck.

The remains were burned. Every one present was sworn to secrecy, but rumors even more weird than the reality were circulated. But we denied them. It was the only thing to do.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.