RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Blue Book Magazine, September 1932 with "The Last Throw"

WHILE convalescing from shell-shock suffered during the First World War, the English journalist George Valentine Williams, who served as a captain in the Irish Guards, took up writing "shockers" on the advice of the prominent genre writer John Buchan.

With The Man with the Clubfoot (1918), Williams introduced Dr. Adolph Grundt (or "Clubfoot"), who became one of the great "master criminal" villains of thriller fiction of the 1920s and 1930s and launched Williams on a lucrative career as a crime writer.

Between 1918 and 1946 Williams published twenty-five crime genre novels and two short story collections.

Many of these works are master criminal thrillers in the Edgar Wallace/E. Phillips Oppenheim mode (some with Clubfoot, some not), but some are detective novels (or at least "mystery" yarns) as well.

The famous Man with the Clubfoot reaches the end

of his tether—a stirring Secret Service drama.

IT was in Spa—where in the last autumn of the war the wires of the whole vast organization of the German armies in the West ran together, where all through those dripping November days that ushered in the collapse of Prussian dreams of world dominion the mud-bespattered cars and motorcycles came roaring in from the front with their fresh tidings of disaster.

Each evening after dark Grete would meet me in the woods, where in happier days the cure guests had laughed and flirted along the leafy promenades now bare and desolate. The prying eyes of a German Feldgendarm might well have taken us for lovers as we strolled along with our heads together—Grete in her shop-assistant's black, and I in my shabby waiter's attire. For little Grete, blonde and slim and graceful, was as charming a companion as a fellow could have wished to find—and as for me, well, I was thirteen years younger than I am today.

Yet an eavesdropper would have heard no talk of love between us. We spoke in breathless whispers of the rout of the German armies, the lengthening shadow of revolution behind the front, the Kaiser and his chances of retaining the throne. For Grete Danckelmann and I were the eyes and ears through which the American and British Governments respectively were following the inexorable march of events at German General Headquarters. The All Highest was lodging in the town behind the machine-guns and sandbags of the Villa Fraineuse and Spa swarmed with secret police. We went in constant peril of our lives, knowing that one false step would land us before the firing-squad.

A week before, an airplane had set me down at dawn in the Ardennes, whence—in the tattered jeans of a Belgian farmhand looking for work—I had drifted down, through the retiring German troops, to Spa. A Belgian in the French Intelligence who kept a café had been warned of my coming, and took me on as a waiter. Having solidly established himself with the German authorities as a strongly pro-German Fleming, my employer—his name was Sylvestre—was able to secure me a permit of residence from the Kommandantur. It was he who put me in touch with Grete.

Being of German-American parentage, the German background was familiar to Grete Danckelmann and, unlike so many German-Americans, she spoke the language flawlessly. As soon as America entered the war, she had registered for employment with the United States Secret Service and, after six months' intensive training at Washington, was sent to Europe. There she disappeared into Holland, where as a German refugee from Brazil, she set to work to build up a German identity. A few months later she was in Germany, then Belgium, and when the call came and the State Department was clamoring for reliable reports from German G.H.Q., she was chosen to go to Spa. No ordinary woman could have carried it off as she did, for even German civilians had trouble about getting permits to visit Spa. But little Grete had a way with her, and the end of October found her as a properly accredited German citizen in the employment of a German florist in the Rue Royale.

ON the afternoon of the ninth of November, a date to become famous in history, she was late at our daily rendezvous.

I was feeling nervous and overwrought. All day long the little town had reverberated with rumors—of mutiny at Kiel, of revolution in Berlin, of the new Chancellor's insistence upon the Emperor's abdication. There was thunder in the air. I divined that tremendous decisions trembled in the balance; but they were being made behind closed doors. Of what use was the elaborate organization we had built up for sending reports away —when we had nothing to send?

I was immensely relieved when presently I descried Grete's slender figure hurrying through the trees.

She was paler than her wont and unusually excited, for her. Her first words were, "The Emperor—"

"Well?"

"He's gone!"

"When?"

"Four days ago!"

"But all day yesterday he was here giving audiences. The communiqué says so."

"That's the bunk. Listen! Yesterday Marie, one of our girls, was out at Roselaer—that's an estate about eight miles from here: it's been shut up since the war. Marie's aunt, Madame Doppel, keeps the lodge—she gives Marie butter and eggs from time to time. But when Marie reached Roselaer early yesterday morning the aunt was out. So Marie went for a stroll in the grounds. In some shrubbery she saw the Emperor—"

"He often drives out to the country, doesn't he?"

"Let me finish! Marie dashed back to the lodge and found that Madame Doppel was back. When the old lady heard of Marie's adventure, she was terrified ; and after a lot of persuasion she told Marie that the Emperor had been living there in the greatest seclusion for the past three days."

"There must be some mistake!" I exclaimed.

"Madame Doppel told Marie that last week a stranger called at the lodge and said the Kommandantur was taking over the château, and that if the old lady wanted to avoid trouble she'd better keep her eyes and mouth shut. That night she heard a car arrive and the very next morning, when she was gathering firewood in the park, she caught sight of the Kaiser in the shrubbery!"

I shrugged my shoulders. "You know what these Belgians are. For them any general with a twisted-up mustache is the Kaiser."

"Marie has seen the Emperor frequently, like everybody else at Spa. She's certain she saw him, and she says her aunt is just as positive. Besides, all kinds of generals have been out to Roselaer during the past three days. She says the Kaiser never goes out except for a short walk in the early morning, and he seems to have only three people with him—two of the secret police, and the third a man whom Madame Doppel saw once looking out of a ground-floor window." Grete paused and looked at me. "What do you make of it? Is he getting ready to bolt?"

"Possibly. But he's here at Spa, I tell you."

She wrinkled up a rebellious nose. "I wonder! I've looked up Roselaer on the map. It's out toward Pepinster. What do you say we investigate?"

Transportation for spies was not included in the scheme of things at Spa. "And foot it there and back?" I said crossly. "It's a damned long walk just to vet a cock-and-bull story like this!"

Grete laughed. "I didn't say anything about walking. I can raise a bike. What about you?"

"Sylvestre would lend me his," I admitted with some reluctance. "But—"

THERE were no buts, however, when little Grete had made up her mind. The pass-control at the exits to the town after dark was stringent. But the food smugglers had their ways of getting out which the young woman, with characteristic German thoroughness, had taken the precaution to ascertain. Less than two hours later, we were creeping through the park of Roselaer, our bicycles hidden at the foot of the outer wall, which we had scaled.

The night was as black as pitch and we floundered about considerably, until the lights of a car showed us the direction of the drive. We headed that way, and steering clear of the avenue presently struck a path through a shrubbery which brought us in sight of the château. It was a compact mansion with an open space in front where three or four cars were drawn up—the chauffeurs' voices reached us as we lurked behind a screen of young firs. The front of the house was dark and silent.

I put my lips to my companion's ear. "No sentries," I whispered. "He's not here. Let's get out while we can." But she shook her head and pointed. Then I saw there was a light in a window at the side of the house.

"Come on," the girl murmured resolutely. "I'm going to have a look."

MY heart misgave me as I followed her. Whatever that lonely house concealed, if privacy were of importance, the secret police were not likely to be far away.

And to reach that lighted window we had a stretch of turf and a gravel path to cross. However, we made it safely. Neither blinds nor curtains were drawn. Keeping in the shadow, we drew near the window. Then dropping to our knees on the flower-bed below it, we raised our eyes to the level of the sill.

The sight we saw fairly took my breath away. The Emperor was there alone. He was striding restlessly up and down the carpet, his useless left hand tucked away in the pocket of his field-gray tunic, his right hand toying with a button.

THIS was the first time I had seen him since the days before the war. He seemed thinner and older and beneath the flat cap he wore his hair was almost white at the temples. But the restless eyes, the sallow skin, and, above all, the studied regal pose—these were authentic. I could not take my eyes off him, even when he turned and faced the door expectantly. I was aware that the girl at my side was tugging at my sleeve and whispering. But all my attention was given to the room. No longer to the Kaiser, however, for the door had swung wide and a vast man stood on the threshold.

I suppose I should not have been surprised to see him there, for who was more qualified to watch over the monarch's safety than the head of his personal secret service? But in the thrills of the week I had spent at Spa I had almost forgotten my old adversary—the terrible Dr. Grundt, better known as the Man with the Clubfoot. The sight of him now, framed in the doorway, square-built, huge of bulk, and lowering, made me tingle with suspense.

The closed window shut out all sound. But it was obvious that Clubfoot was in a highly excited state. He seemed to radiate defiance and menace, and so strong was the man's personality that, like the radio beam, his mood penetrated through brick and glass to us outside. We could not hear what he was saying, but his gestures were brusque and imperative—I was astonished to see what little account he made of the imperial dignity.

At length the Emperor moved to the door and they went out together.

All this was the matter of seconds. As soon as I saw them depart, I turned to Grete, who was still trying to attract my attention.

"Some one in the shrubbery," her lips formed. "Let's go!"

We sprang to our feet. There were steps in the shrubbery and other steps approaching from the front of the château. I cast a hurried glance about us and spied a glass door in the side of the house a few yards distant. It was a thousand-to-one chance, but I grabbed Grete and pushed her toward it. The door yielded to the handle and we slipped inside.

We were in a dark lobby with a door at the farther end. Tensely we stood there listening. The footsteps drew nearer and then two figures were silhouetted on the glass panel of the door. Two men whispered there. Grete and I exchanged one look and by common consent backed toward the door at the end of the lobby. Fortune favored us again. The door yielded easily to my touch....

The room in which we found ourselves —a small study—was dark save in the center, where a shaded lamp on the desk cast a circle of light. At first I thought the room was empty; then I saw that a man stood at the desk, a telephone-receiver to his ear. With a sinking feeling I recognized Grundt. He had his back to us and seemed completely engrossed, listening in silence to an excited voice that came squeaking out of the receiver.

I don't mind admitting that Grete's wits were sharper than mine. She had caught me by the wrist and dragged me across the heavy-pile carpet to a curtained window recess, before I caught the sound of feet in the lobby we had just left.

I heard Grundt's voice at the telephone. "Nonsense!" he vociferated wrathfully. "He's leaving for the Second Army now. He'll spend the night there and show himself to the troops tomorrow. Adieu!" The receiver was slammed down.

I RISKED a peep through the curtain. Two burly individuals—characteristic secret-service types—had entered from the lobby. Said one: "Herr Doktor, there's some one in the park. We found two bicycles hidden outside the chateau wall. Has the Herr Doktor heard or seen anything?"

Grundt stirred out of a profound reverie.

"Herr Gott, man, what has that to do with me? You have your orders—if you see anyone, shoot! Now get out—in five minutes we shall be gone, anyway!"

The spokesman touched his hat. "Very good, Herr Doktor!" The two men went out. A small hand seized mine and wrung it hard—that handclasp was like a sigh of relief uttered in unison.

Clubfoot's gruff voice brought me back to my spy-hole.

"Ready?" he demanded.

The Emperor had appeared in the door. Cloaked and helmeted, he made a somber, imposing figure. "Any news?" he asked in a toneless voice and came into the study.

"Nothing fresh," the big man growled. "If they can hold him tonight, we can get away with it!"

Before I had time to ponder the strangeness of this rejoinder, a bewildering thing occurred. The Kaiser had an unlit cigar in his right hand. Now, as Grundt was talking, I saw His Majesty draw his left hand from the pocket of his military greatcoat and pick up a box of matches from the desk. And the hand he used was as normal and as serviceable as his right, as was demonstrated by the ease with which he manipulated the match-box. Even with my knowledge of disguise I found it hard to believe the evidence of my senses. This seemed to be the Emperor, yet it was not he! For the Emperor's left hand and arm had been withered and useless from birth.

In a flash I guessed the truth. This bogus War Lord was Grundt's counter-stroke against the growing movement at G.H.Q.—to which, it was whispered, even Field Marshal Hindenburg had been won round—in favor of the monarch's abdication. Clubfoot's puppet was to rally the troops and lead them back to combat the revolution at home while the wayward and vacillating Kaiser was kept out of sight or otherwise disposed of. All these past days the understudy—some actor, I surmised—had been getting into the skin of his part under Grundt's tuition in the seclusion of Roselaer.

IT was Grundt's last throw, a masterstroke worthy of the master mind that conceived it, and likely to commend itself to the large number of officers in high commands at the Front who, I knew, were incensed by the steadily increasing effacement of the Supreme War Lord. No doubt the military visitors to Roselaer were in the cabal.

But now Grundt, followed by his fellow-conspirator, hobbled out. It was our chance to escape. Silently I opened the casement behind us. We listened. The drone of cars came from the front of the château, but in the gardens all was still.

"Now!" I whispered, and I hoisted Grete up to the window-sill.

At that instant the telephone woke all the echoes of the room. Grete was clear of the sill; her face looked up pallidly at me from the darkness outside. Then I heard a shout, a rapid step, behind me and realized in the same moment that the draft from the window must have parted the curtains and disclosed me to some one who had entered. I had got a leg over the sill when I was seized from the rear. I fought desperately, but two of them were at me and a pistol thrust into my ribs decided the issue. My gun was plucked from my pocket and I was dragged back into the light.

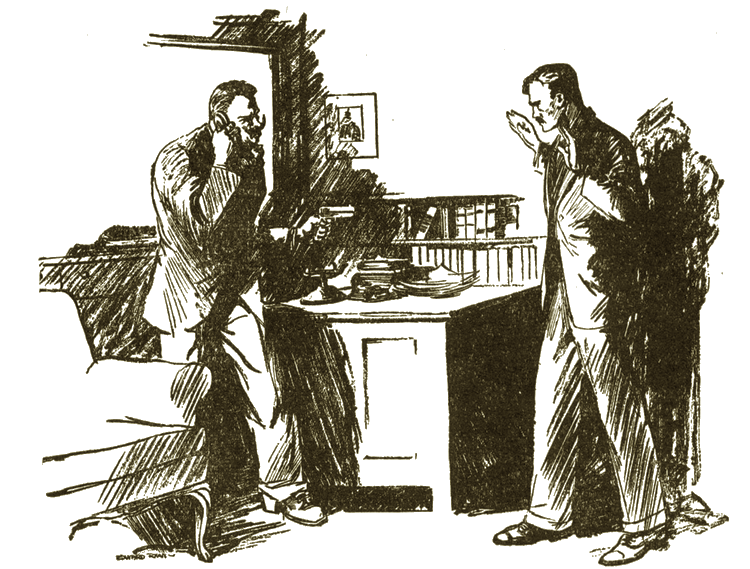

GRUNDT, his features distorted with rage, was at the telephone. "I'll wait for your call," he rasped and hung up. "There were two of them, you said," he snarled at the men who held me. "Get out and find the other. And when you find him, shoot him! You can leave our friend"—his bulbous lips parted in a cruel smile as he drew a big automatic from his coat—"to me!"

My mind was racing madly. Clearly they had not seen Grete: she must have had time to get away. But she was loyal and brave—I was desperately afraid she might think it her duty to wait for me and so bring disaster upon both of us. My heart thumping, I trained my ears for any sound from the park.

Grundt's voice seemed to come from far away. He was chattering like an angry baboon. "Schweinehund, scum!" he raved. "You tried to interfere with my plans once too often. I'll teach you not to poke your nose in where you're not wanted—and the lesson will last you for life!"

"Scum!" he raved. "You tried to interfere once too often.

I'll teach you—and the lesson will last you for life!"

And then the telephone whirred again.

Holding me covered with his gun he lifted the receiver. His eyes, scarcely human, were fixed on my face. But as he listened I saw the fury die out of them and a look which gradually turned from one of incredulous amazement to one of abject despair take its place.

"The Republic proclaimed? It's not possible!" he roared. "He's abdicated—you let him? Himmelsakrament, it's not true! Give me until morning—only six hours—and I'll undertake to line up the whole mass of combatants behind him What? What's that you say? Damn this line—I can't hear.... He's leaving for Holland? Tonight? You've got to stop him!.... What do you say? Gone? Gone already?".... Then silence.

Blindly, fumblingly, he restored the receiver to its hook; then, with a savage snarl, he flung his pistol at my feet and sank into a chair. He had suddenly grown old and broken—and if I could ever have found pity in my heart for Grundt, it was then.

"Clavering," he said, "my master, whom I was proud to serve, has run away! Take up that pistol and kill me, for my day is done. The army is in revolt, the monarchy has fallen, the Republic sues for peace—and Prussia's Soldier King is in flight. This is, indeed, the end!" The massive head drooped on that barrel-like chest and I saw a tear roll down his cheek.

And then I heard a shot in the grounds outside.

In two bounds I was at the window. One of Clubfoot's bulldogs stood below the window facing the shrubbery, taking aim with his revolver, which yet smoked.

I jumped straight down on his back, bearing him to the ground. His shot went roaring into the night.

I jumped straight down on his back, bearing him to

the ground. His shot went roaring into the night.

He rolled free and was scrambling to his feet, jerking his pistol up to fire again, when I reached him. The swing I landed him on the point of the jaw gives me a thrill of satisfaction to this day when I think of it. He folded up with a grunt, and leaving him sprawled out on the gravel, I darted toward the shrubbery.

Grete was there behind a tree, her lips compressed with pain. Her arm hung helplessly by her side. "Through the shoulder," she murmured faintly. "I shall be all right—"

"Why didn't you get away when you had the chance?" I demanded reproachfully.

She smiled at me. "We were partners," she said—and fainted.

There were soldiers in the grounds now, waving bottles and shouting: "No more war! Long live the Republic!" Two of them helped me to bring my companion down to Madame Doppel's, where we remained quietly until, with the signing of the Armistice a few days later, the first Allied officers arrived at Spa....

This story ends, as all real stories should, with wedding-bells—though they did not ring for me. I functioned merely as best man at Grete's wedding in London, a few months later, to a charming young lieutenant of the United States Marines. The cross of the Order of the British Empire which I was able to procure for her looked very effective on the corsage of her wedding-gown.

AS for the Man with the Clubfoot, you shall take leave of him, as I did—crumpled in his chair among the ruins of Prussian autocracy to whose service his whole life had been given.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.