RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

"The World of Action," Hamish Hamilton, London, 1938

"The World of Action," Hamish Hamilton, London, 1938

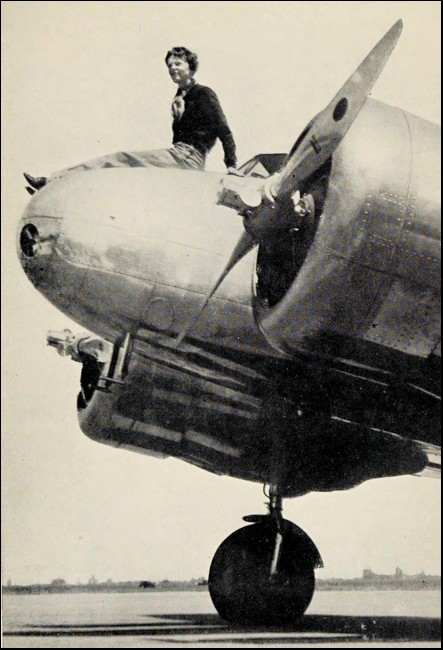

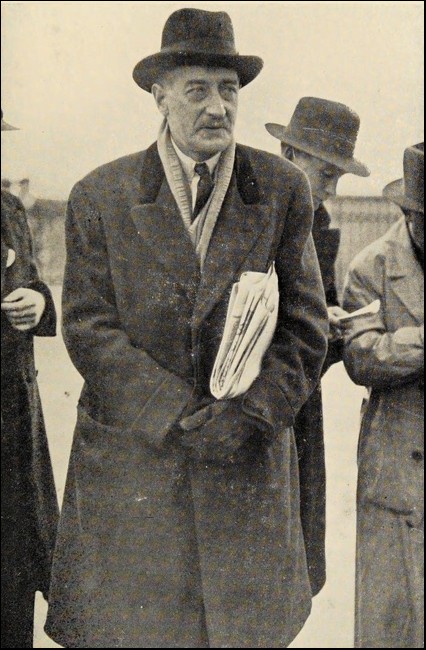

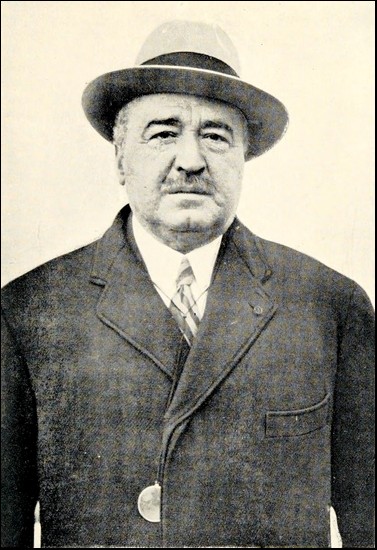

The Author. Pencil Drawing by James Gunn.

This is the autobiography of Valentine Williams, author of the "Clubfoot" novels and many other best-selling stories of sensation. Valentine Williams has journalism as well as novel-writing in his blood. He is the son of the late Chief Editor of Reuter's. He was born in 1883, educated at the famous Catholic public school, Downside, had a year in Germany, and went into Fleet Street at the age of eighteen. At twenty-one he was made Reuter's representative in Berlin, and he lived and worked there for several years. Then he was 'spotted' by Lord Northcliffe and became Paris Correspondent, and later chief war correspondent of the "Daily Mail". He has been all over the world as a foreign correspondent, fought in the Irish Guards during the war, and wrote the first "Clubfoot" novel when wounded. He married Alice Crawford, the distinguished actress. He has met a large number of eminent as well as many notorious people, probably even more than most journalists of his type, and, being a very intelligent man, he has made a remarkably good job of this book. Its field ranges over the worlds of diplomacy, literature, espionage and crime; it is full of interesting anecdotes, strikes the happy mean between boastfulness and false modesty, mentions stacks of famous names, and holds the interest from the first page to the last. Incidentally, it is also extremely well-written. It is a book that is not only well worth publishing but one that is almost certain to have a large sale.

Happy the man, and happy he alone,

He, who can call to-day his own:

He who, secure within, can say,

To-morrow do thy worst, for I have liv'd to-day.

Be fair, or foul, or rain, or shine,

The joys I have possessed, in spite of fate, are mine.

Not heaven itself upon the past has power;

But what has been, has been, and I have had my hour.

John Dryden. Imitations of Horace.

J'ai tant joué avec age

A la paume que maintenant

J'ai quarante-cinq: sur bon gage

Nous jouons, non pas pour néant.

Assez me sens fort et puissant

De garder mon feu jusqu' à ci,

Ne je ne crains rien que souci.

Allegory on the game of real tennis, composed by Charles d'Orléans, captured at Agincourt and held prisoner of war in England in custody of the Wingfield family, ancestors of Major Wingfield, the originator of lawn tennis.

Wisdom is better than weapons of war.

Motto of the Secret Service as quoted by Admiral Sir Reginald Hall, Director of Naval Intelligence at the British Admiralty during the World War.

IT is not easy to lay down precisely the age at which a man may with propriety publish his autobiography. If he bring it out while he is still youthful, he is apt to be rated vain and precocious, while to do so, forestalling old age, in his middle years, however full and varied his life may continue to be, is to risk branding himself a back number. It seems to me, however, that to await the evening of life for the gathering up and threshing of the sheaves, is to incur the greater risk. All too soon the lapse of time begins to blur the sharp outlines of remembered things, especially when every day the fresh encounters and impressions of a crowded life threaten to confuse the record. I agree with Patrick Henry when he told the Virginia Convention, 'I know of no way of judging the future but by the past.' To-day and to-morrow are the children of yesterday. When a man has a story to tell, the better time to tell it is before the march of events has robbed the lessons he has learnt in life of any value they may possess. There is such a thing as publishing one's autobiography too late.

I was a newspaper man, then a soldier and now I am a novelist, whose feet still turn to Fleet Street as inevitably as a river to the sea. I have touched life at many angles, the grave and the gay, the villainous as well as the sublime, making notes as I mingled with all sorts and conditions of men, the great as well as the humble, and finding humanity the most interesting study of all. Almost everything I know life has taught me and anything I may have to teach is drawn from life.

A writer never graduates. I am still learning my trade as a novelist, but, as I realise in retrospect, its rudiments I picked up in Fleet Street, in wars and revolutions, in and out of the chanceries and parliaments of Europe. As I can trace back plot and characters in my novels to incidents and encounters of my newspaper days when, with a belt of golden sovereigns round my waist, I would leave at an hour's notice for Spain or the Balkans or Italy, so I discern around me to-day innumerable threads connecting with the political and social life of the world as it was.

The past can take care of itself. It is the new values of the rapidly changing world we live in to-day that are important. A curious thing about them is that the closer we scrutinise them, the better showing they make. I shall not try to establish these values. My hope rather is that, in the course of this narrative, they may establish themselves by contrast with certain highlights I descried in the world as I have known it. To glorify the present with fire from the fountains of the past, as the poet wrote, seems to me to be a task to warrant a busy author indulging in a Sabbatical year.

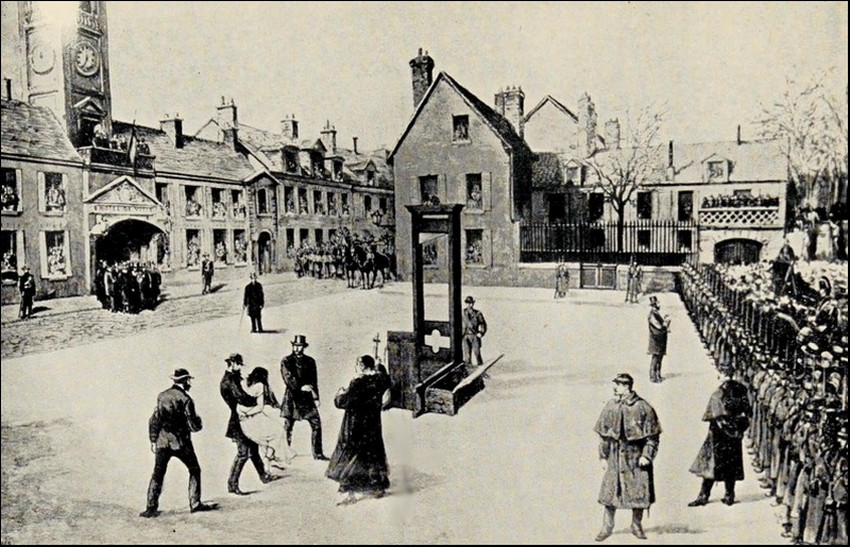

The continuity of history has always appealed to me. It fascinates me to look back and reflect, for instance, that to Pepys and Evelyn the reign of Henry VIII must have seemed a great deal more vivid even than the picture of their own day, as painted by those famous diarists, comes down to us. My father's father was born as far back as 1797 and I have worked it out that the black-draped block outside the Palace window in Whitehall, that frosty morning of January 1649 which ushered in the revolutionary history of modern Europe, could have been described to him at third hand.*

* Since writing the above I read in the Daily Mail of 31st December, 1937, a letter to the Editor from 'M.S. Southport' stating: 'I am the son of a father by a second marriage contracted late in life. I am 89. My father was 86 when I was born. His father was 78 at the time of my father's birth. My grandfather was born in 1684 when his father was 52. My great-grandfather born thus in 1632 saw Charles I beheaded.'

One of my earliest recollections is of being taken as a very small child to see my godfather, Valentine French, after whom I was named, lying in his coffin. He died in the year 1888 at the age of eighty-three and he could remember as a small boy the stage-coaches and post-chaises coming through the villages decorated with oak leaves in celebration of Waterloo. A similar link with Waterloo was furnished by a veteran member of Boodles I used to hear about, who liked in his old age to tell how, walking out as a child with his father along Pall Mall, they perceived a knot of people gathered cheering outside the old War Office (where the Royal Automobile Club now stands). A dusty chaise drawn by smoking horses stood there and from the windows of the conveyance protruded a sheaf of golden eagles—it was the Duke of Wellington's courier to the Prince Regent with the first tidings of victory.

The continuity of history! It has always diverted me to cast about for traces of it. During the War, when I was billeted at Vauchelles on the Somme with the 1st Guards Brigade, Baron de Gosselin, who had the château there, took me up to his bedroom and showed me, scratched on the window, the name 'Julie' and the date '1812'. The wife of a Russian officer, lodged at the château after Napoleon's withdrawal to Elba—she might not even have been his wife—had written her name there with a diamond. Twice—in 1870 and again in 1914—the Prussians were also the uninvited guests of the Gosselin family. Likewise when I was at the War, I saw at the Château d'Éperlecques, near Thérouanne, the rings driven into the château walls by the British 15th Light Dragoons when quartered there after Waterloo, to which, when I was at Éperlecques, the troopers of the 15th Hussars, as the 15th Light Dragoons afterwards became, were tethering their horses.

My own life may fairly be considered as a bridge between Stalin and the Chartists, inasmuch as my father could remember being lifted up as a child to see a Chartist procession go by. In 1839, when my father was born, Waterloo was as fresh in men's minds as the outbreak of the World War to-day. He could recall being taken as a schoolboy to visit the Great Exhibition of 1851, that characteristic manifestation of Victorian activities and aspirations at which Her Majesty sculptured in soap foreshadowed Wembley's offering of her great-grandson moulded in Empire butter. My father always spoke of his escort as 'a gentleman', a phrase which conjured up in my mind something portentously solemn and Victorian—all top-hat and whiskers and peg-top pantaloons—especially as, after dragging his small charge through miles of improving exhibits, his mentor conducted him gravely to a refreshment-room and there by way of lunch presented him with a glass of milk and one bun. That scurvy hospitality remained as one little boy's solitary recollection of the glories of the Great Exhibition—a warning to parents.

My father was George Douglas Williams and his entire career was bound up with Reuter's, the great British news agency, of which he was Chief Editor when he retired. His active life as a journalist embraced the whole upward curve of the world's progress from the welding of a nation in the American Civil War to the crumbling of Russia's dream of Far Eastern expansion. From childhood he was taught the love of literature and foreign languages by his father, a notable linguist. An early diary of my grandfather's, which he kept when leading the life of a country gentleman at Lansdowne, outside Bath, in the thirties shows that one of his recreations was to turn the Gospels into Greek or render the Latin and Greek classics into English verse. He had an excellent command of French, Italian and Spanish and among my books is his Don Quixote in the original, a fine copy bound in vellum which he purchased in Madrid during his 'grand tour'.

As a boy it .was my father's Sunday task to translate the Lesson into French, or Italian, or Spanish. Backslidings were duly corrected, after the Victorian habit, with a cane—my grandfather had a penchant for early morning executions. He was the strictest of disciplinarians and invariably addressed my grandmother—his second wife—as 'Mrs. Williams' or 'Ma'am'. His English was apt to be biblical in its bluntness. My father used to tell how once, when he found fault with the food at table, my grandfather turned to his spouse and said, Olympically, 'Your son is picksome, ma'am! Let him rather give thanks to his Maker that he has a sufficiency of coarse and abundant victuals to fill his belly!' He liked to deck out his table talk with classical tags in the original and after such a quotation had rolled sonorously from his tongue, he would usually add, addressing my grandmother, 'Which your son, ma'am, will have the obligingness to translate!'

His portrait, which I have, shows him in a red velvet waistcoat and gold chain, with a splendid head of wavy, jet-black hair, black whiskers and a firm, clean-shaven mouth. For many years the family lived in Camberwell Grove, a highly 'eligible' suburban retreat in those days—Joseph Chamberlain was born in Camberwell Grove. I have dwelt at some length upon my grandfather because, apart from the influence he exercised vicariously upon my bringing up, he represented a type of British paterfamilias at present as extinct as the smoking cap and the poke bonnet. He had his Law degree and, although he never practised as far as I know, retained almost to the day of his death his chambers in the Temple at No. 4 King's Bench Walk, where he liked to give oyster and porter parties for his friends after the play. At one time he lived at Ilchester, in Somerset, where he was locally known as 'Squire Williams' and I have the sabre he wore, as an officer of the North Somerset Yeomanry in the Corn Riots of the early thirties. In recognition of his services his tenants presented him with a Toby jug suitably inscribed, which is still in the family. One way and the other he must have been comfortably off, for he never earned his own living; but the money seems to have slipped through his fingers and he did not leave much beyond a house full of nice furniture, old china and silver when death overtook him. He died, like an English gentleman of the old school, of the gout at the age of eighty-one, four years before I was born.

It was from this background of Victorian discipline, stern principles and an unusually high level of culture that, in the year 1859, at the age of twenty, my father emerged into metropolitan journalism. As good a linguist as his father—he spoke and wrote French, Italian and Spanish fluently—well-read and fortified by an admirable literary judgment, thereafter, for more than forty years, he was immersed in the chronicling of the world's affairs.

He was essentially and entirely of the nineteenth century, that spacious age stretching from the closing convulsions of the French Revolution to the invention of the petrol-driven carriage—the present century, at the time of his death in 1910, was yet too young for him to have grasped its trend. Looking back upon that sturdy character which so greatly influenced me, I feel as though the last hand-clasp we exchanged, my father and I, linked up that Europe which was doomed to disappear in the fire and smoke of the Hindenburg Line with the new civilisation at present struggling to emerge from the chaos of economic disaster.

It is scarcely realised now what a thrill ran through the nation when, after Queen Victoria's long innings, a King ruled in England once more. My father voiced the general sentiment in a remark so Victorian in its implications as to be unthinkable in the mouth of an Englishman to-day. When one of my sisters asked him why he was so pleased to have a King again, he replied apologetically, 'I can't help thinking that man is a nobler animal than woman!'

He was a few years older than King Edward, and I was surprised to find with what a real shock the King's death came to him. I suppose that, to his contemporaries, the Prince of Wales was identified, even more than Queen Victoria, with the daily life of his time. My father died four months later, and I had the impression that the Royal passing-bell sounded like a Nunc Dimittis in his ears and the ears of many others of his generation.

Centuries of struggle, of happiness and suffering, of persecution and of emancipation, peer out of the dimness of the ages through the eyes of human beings. For more than forty years my father was recording world events and for almost three decades more I carried the torch which he handed on to me, and my brother after me. Millions of printed words, miles of columns of news print, represent the sum of the years of unbroken newspaper activity from 1859 on to the present day, standing to my father's record and ours, from the steamer-borne dispatches of the American Civil War to the airmails, the transatlantic telephone and the radio transmission of pictures to-day.

My father and the forces that moulded him have a definite place in the picture I am trying to paint, if only for the reason that the continuity of history is so clearly marked in our respective careers. He was coached in literature and languages by his father and in turn coached me: he was a special correspondent abroad in friendly rivalry with such famous newspaper men as the great de Blowitz, 'Billy' Russell, Archibald Forbes, and Laurence Oliphant, even as I was destined to be, in competition with Ashmead-Bartlett, Philip Gibbs, Henry Nevinson, Martin Donahoe, Percival Phillips, Frederic Palmer, Richard Harding Davis and Alexander Powell: like me he saw great European nations at war and wrote his dispatches under fire; and he met and spoke with Cavour, Bismarck, Thiers and Gambetta just as I, four decades later, was to meet and speak with von Bülow, Clemenceau, Delcasse, Briand, Theodore Roosevelt. He saw the French Empire crash, I the German: he was fascinated by the strange, haunted regard of Napoleon III, 'that great unrecognised incapacity', as Bismarck called him, even as I by the restless, unstable personality of William the Second; and it was only chance, as I recollect, that prevented him from attending the proclamation of the German Empire in that selfsame hall at Versailles where, forty-eight years later, I was to see the German eagle humbled to the dust.

As I have spoken of the continuity of history I will here digress to tell an anecdote. When I was head of the Daily Mail staff at the Paris Peace Conference, although I was unable to procure my wife an official invitation to see peace signed, I contrived, by means of a little judicious bribery, to smuggle her into the Galerie des Glaces. She was standing on a bench, looking out over the heads of the crowd, when a nice old gentleman, who was perched on a chair beside her, remarked in English, 'I suppose I'm the only person present who saw the German Empire proclaimed in this very hall on the 18th of January, 1871.'

It was the late Lord Dunraven (the American Yacht Cup challenger). He served as a special correspondent—of the Daily Chronicle, I believe—during the Prussian occupation of Versailles. From inquiries I made at the time I have little doubt that his surmise was correct. Some thought that Clemenceau must have been present on that historic occasion, but I ascertained that at the time he was Mayor of Montmartre and far too occupied with the confused state of national politics to get away to Versailles, even if he had wished to witness the crowning of Germany's victory.

The Europe of my father's manhood years was dominated, notwithstanding Sedan, by France: Russia was the bogy-man, barbarous and unintelligible, whose censors had the execrable taste to black out the leading articles in Mr. Delane's Times. Germany was an inconvenient upstart with whom it behoved Britain to walk delicately owing to tender recollections of the beloved Albert: Italy still a chaotic experiment: Turkey a sick man with Constantinople as the bone of contention among the impatiently waiting heirs; and the United States a rather vulgar relation.

To the day of his death my father's political outlook was coloured by his warm affection for France. Not only was he, by virtue of his upbringing, strongly drawn by the wit and elegance of French literature but also, like most men of his class and age, he was under the spell of Paris. For the Paris of the Second Empire, as he first knew it, was the centre of the civilised world and long after its lights were dimmed and the Tuileries laid in ashes, the prestige of its splendour lingered on. Moreover, my father's first foreign post was Florence, and the behaviour of the Austrians in Italy was not such as to predispose him in favour of the Teuton. He was never blind to the insensate folly of Napoleon and his Ministers and right up to Fashoda his besetting fear was lest French Chauvinism should again set Europe ablaze. But at the same time he clearly perceived the danger to England of Germany's rise to world power. The frightful humiliation of France, of which he had been an eye-witness, was a lesson he never forgot; and even before Lord Roberts uttered his first warnings of the German peril, my father kept his gaze constantly fixed on the other side of the Rhine. I was a schoolboy at the time but I remember him, as clearly as though it were yesterday, putting into my hands Rudyard Kipling's 'Recessional', published in The Times on the occasion of the Diamond Jubilee of 1897, and begging me earnestly to read it.

On September 9, 1870, a few days after the proclamation of the French Republic, my father wrote from Paris to his mother:

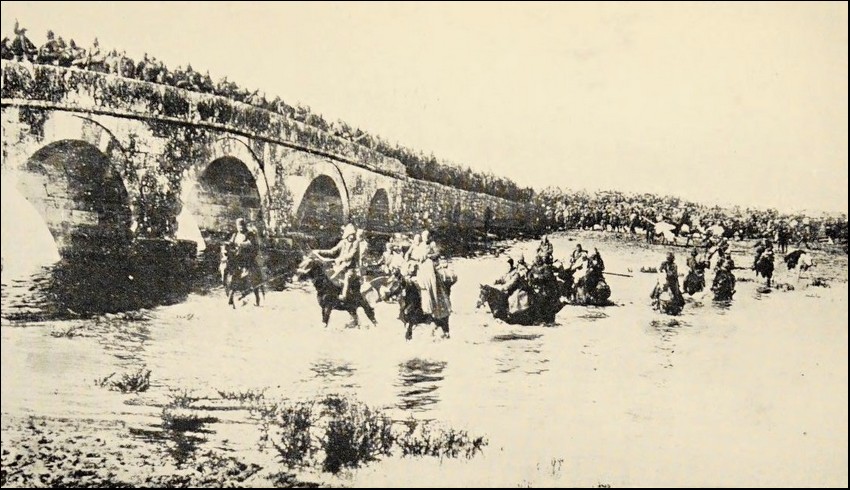

'Some days ago, I sent Father two papers containing a full description of the revolution which was accomplished here on the 4th of the month—Sunday. I was in the thick of it all, and if there had been any fighting might have come in for a bullet. But, although there was immense, frantic enthusiasm, all passed off without any violence or bloodshed. There was not a single head broken. I went early to the Chamber of Deputies that day—for important proceedings were expected after the terrible news of the defeat before Sedan and the Emperor's capture. And there was indeed an outburst. Early in the afternoon, immense multitudes rushed over the Pont de la Concorde and invaded the Chamber. The troops and National Guard fraternised with them and then arose formidable, sky-rending shouts which made one thrill and feel enthusiastic too. It was "Down with the Emperor!" and "Vive la République!" What a delirium it was! Men were kissing each other and laughing and weeping for joy. They were relieved, they said, of the nightmare of twenty years (the Empire): they could laugh again and be free. The scene in the Chamber reminded me of the descriptions of the National Convention in the days of the First Republic. The mob swarmed all over the place, on the floor of the house, in the deputies' seats, everywhere, and the confusion and the uproar were such as to defy description. Outside some twenty or thirty thousand people were singing the Marseillaise in chorus—and to hear that so sung is grand indeed. Thus the Empire fell in a day—fell from the weight of its faults and its awful ineptitude in the hour of danger. There is scarcely an example in history of so shameful a collapse as this of France before Prussia. The fatuity with which the Emperor rushed into war and the incapacity of the carpet knights and courtiers whom he made Marshals and Generals, are pitiable. It is only Dante who would know in what zone of the Inferno to put such a man. He has been well called here the sinistre histrion and the French are now paying heavily for their weakness and folly in accepting a master in Napoleon III.'

And a day later:

... What an eventful year this will be for the world! France cast from the first rank of Powers to the second, Germany risen up strong and mighty, the Pope overthrown; and who knows what else there may not be yet to come? England is behaving ignobly, pitiably, in all this, and I almost blush to be an Englishman at the present moment. We have no statesman and no policy and we refuse to raise our voices against the dismemberment of a faithful ally. England never abdicated so shamefully her place as a great Power and never gave such reason as now to those who accuse her of utter selfishness. We shall suffer for it bitterly one day and in our distress shall look around in vain for a single friend to help us. We think we are secure in our island and so let carnage and violence go on unchecked and allow ourselves to become the bye-word of Europe as the power that will talk but never fight to prevent wrong. In my humble opinion Mr. Gladstone, great man as he is, is quite at sea in foreign affairs, and the rest of the Cabinet are narrow-minded respectabilities and peace-at-any-price men.'

The continuity of history! Did not Englishmen hear in the Great War of another Power that 'will talk but never fight to prevent wrong'?

IN the year after Waterloo, in the picturesque German Residenz of Hesse-Cassel, there was born to poor Jewish parents a boy who was destined to become one of the outstanding pioneers of modern journalism. I have been told that the first Baron de Reuter's real name was Josaphat and that in his youth, before railways came into existence, he travelled the roads in Germany as a pedlar, with a pack on his back. What is certain is that in the very earliest days of telegraphic communication, with the foresightedness which ever distinguished this remarkable man, he perceived that a new era in journalism was at hand.

Up to the middle of the nineteenth century few newspapers had foreign correspondents of their own. Foreign intelligence was culled from foreign newspapers as and when they arrived through the mails or from letters forwarded by banking correspondents abroad. The first telegraph line in Germany to be open to the public was that between Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) and Berlin and in 1849 Paul Julius Reuter, as he then was, was established at Aachen where he had set up an organisation for collecting and transmitting telegraphic news. The enterprise and importance of the London Press and, especially, the development of telegraphic facilities in the British Isles soon drew his attention to England. He became a naturalised British subject and, when the first cable between Dover and Calais was laid in 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition, transferred his activities to London. There, on October 10th of that year, he opened at the Royal Exchange his first place of business in England, simply known as Reuter's Office. Such was the beginning of the great news agency which to-day covers the entire globe with its tentacles and the inauguration of the present world-wide practice of news syndication.

At that early period the work, which Mr. Reuter undertook himself with the aid of an office boy, was confined to the circulation of market reports and commercial news. Gradually, however, the business extended and 'Reuter's Office', having representatives in most of the foreign capitals, began to supply political and general news as well. At this stage of his career Reuter reverted to his old occupation of peddling, though now not ribbons and laces, but foreign news messages were his wares. Fired with faith in his idea and fortified with that patience which is the tribal badge, he spent long hours in the waiting-rooms of Fleet Street attending the pleasure of Olympic and distrustful editors. Many newspapers, in the first rank The Times, long refused to publish his news at all and those who found room for his dispatches did so infrequently and capriciously. In his old age Baron de Reuter, always an excellent raconteur, delighted to tell of the ups and downs of those early London days.

It was not until the year 1859 that 'Reuter's Office' established itself definitely as a prompt and reliable news-purveyor by the first of a long series of historic 'scoops'. By the astute use of the Paris-London telegraph—at that time Paris was still the only point on the Continent in direct telegraphic communication with London—Reuter circulated the first report of the ominous words used by the Emperor Napoleon III to the Austrian Minister to France at the New Year's Day reception at the Tuileries, which foreshadowed the Italian campaign and the long fight for the union of Italy. The Emperor's remarks, which were tantamount to a declaration of war, set Europe by the ears and convulsed the Stock Exchange, and Reuter's reputation was made. Thereafter, no London newspaper could afford to dispense with the Reuter news and even Mr. Walter's Times capitulated and made an agreement with Mr. Reuter for a daily news service.

It was about this time that my father, then drudging as an underpaid clerk in a shipping office in Leadenhall Street, chanced to read a newspaper advertisement offering employment of a literary character to a well-educated young man with a knowledge of languages. Inquiry showed that Reuter's Telegraph Office, by now removed to more commodious premises at 5 Lothbury, in the shadow of the Bank of England, was the advertiser. My grandfather accompanied his son to the latter's first momentous interview with his future employer and I have no doubt condescended mightily to the diminutive little German with the trailing 'weepers' and funny English who received them. In the upshot the applicant was engaged as sub-editor at a weekly wage, I think of a pound. It is characteristic of the cheapness of life in London in the Victorian era—for Reuter's compensated its staff adequately if not over-generously—that when my father retired as Chief Editor in 1902, the year after Queen Victoria's death, after forty-two years of unremitting and highly responsible labour, his salary was £750 a year, free of income tax—less than fifteen times his original weekly stipend. As a matter of interest I might add that, until shortly after the Great War, all Reuter salaries were paid free of income tax. O tempora, O mores!

Under the system which Mr. Reuter had initiated for the exchange of news with foreign capitals—a system which ultimately developed into a comprehensive plan of alliances with the official news agencies abroad, the Havas of Paris, the Wolff Bureau of Berlin, the Stefani of Rome, the Associated Press of New York, etc.—the bulk of the messages handled had to be translated—into English for the incoming, out of English for the outgoing. Foreign tongues are, notoriously, not the average Englishman's forte and Mr. Reuter, therefore, had perforce to rely to a considerable extent on foreign journalists, some of them already associated with him on the Continent, in forming his small staff.

A singularly motley crew he had gathered about him. The bohemianism of Grub Street and the Burschenfreiheit of Berlin and Vienna mingled together in the editorial rooms at Lothbury and the small night office, located handy to the telegraph companies, at 5 King Street, Finsbury Square. The most prominent and gifted of Mr. Reuter's helpers in those days was Dr. Englander, an Austrian Jew who, condemned to death for his share in the March Revolution of '48 in Vienna, had taken refuge in Paris. He seems to have been a fine journalist, and a notable polyglot, but of my father's many stories about him I am afraid I only remember the Herr Doktor's invariable habit of travelling in company with one of his 'nieces', of whom, it appears, he had an inexhaustible and attractive assortment.

As a very small boy—I cannot have been more than seven or eight years old at the time—I had an encounter with one of the 'Old Guard' at Reuter's, which I have never forgotten. It was a foggy November day, and, escorted, by the Chief 'Manifolder', as the clerks were called who made the copies of the messages for newspapers—by hand, of course, at that time—I had been to see the Lord Mayor's Show. When I was duly landed back in the editorial room at Reuter's, my father was busy and I was left to my own devices. At this moment an enormous man, bony and lanky and crowned with a mane of iron-grey hair, approached me.

'Young man,' he thundered at me in stentorian tones, with a strong German accent, 'do you perhaps know who I am?' 'No, sir,' I answered timidly. He pounded his barrel chest with his fist. 'I am Petri, Leutnant der Reserve, Seventh Corps, B.G.,' he boomed, and added, 'and can you perhaps tell me what "B.G." stands for?' I shook my head. 'Bloddy Cherman!' roared Lieutenant Petri, who had fought with the Prussians against the French at Metz, and shouted with laughter.

Thereafter, he bought me a bun and a glass of lemonade and subsequently invited me to visit with him a large toy warehouse in the City kept by a 'Cherman' friend of his. I was turned loose in this entrancing place, as it seemed to my juvenile eyes, and allowed to choose three toys for myself. The selection was not easy but I can still remember that I came away with a musical box, a toy stable and a gun. What a thrilling afternoon that was!

As news knows no clock, so Reuter's maintained a twenty-four-hour service, as, indeed, the agency does to this day. The night desk at that time was a solo turn and it fell to my father's lot, as the latest joined recruit, to fill it for months at a time. 'You have no idea how hard we used to work,' he used to tell me — a seven-day week and a twelve- or fourteen-hour day was the rule. He was still living with the family and, as there were no all night trams and no early morning tubes or buses, he had to tramp home through the dawn all the way from Finsbury Square to Camberwell. His route lay over London Bridge and I never cross that historic structure without a thought of that dark-haired young man, his brain buzzing with thoughts of Napoleon and Monsieur Thiers, Cavour and Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel, Herr von Bismarck and the Chancellor Beust, Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis, pausing at the parapet, as he told me he would often do, to doff his hat and let the early morning breezes from the Pool fan his brow.

In those days Mr. Reuter, married to a young lady from Berlin and father of three children, lived in Finsbury Square. The night office of the agency—at 5 King Street, as I have said—was situated at the bottom of the garden, with a private way through from the house, a patriarchal arrangement which fills me, who have known the stern utilitarianism of modern Fleet Street, with a gentle melancholy. It was Mr. Reuter's habit to pop in at the night office at odd hours, to hear what news had come in but also, no doubt, to assure himself that the editor-in-charge was at the post of duty. On one fatal occasion, in the early stages of the American Civil War, my father, who was on the night-shift, had flung himself down on the camp-bed which the management had thoughtfully provided for the use of the editor-in-charge between messages. He awoke from a deep slumber to see before him Mr. Reuter, in night-cap and Paisley dressing-gown over a long white nightshirt, shaking a dispatch at him. It was a message which the telegraph boy, failing to arouse the sleeper, had deposited upon his chest.

It was also the first intelligence of the Confederate victory at Bull Run!

'Ah, Mr. Williams,' said Reuter in his gentle way, 'the sleep of youth is so sweet, I cannot be angry with you!'

With their private aeroplanes and transatlantic telephone-calls and wireless pictures, modern editors are apt to be self complacent about their enterprise. But such pioneers of journalism as Paul Julius Reuter, John Thaddeus Delane and Gordon Bennett could still give them points. The outbreak of the American Civil War—the War between the States, they prefer to say below the Mason-Dixon Line—found the whole English-speaking world clamorous for news of events which were taking place across 3,000 miles of ocean. There was no cable—all news had to come, slowly and methodically, by mail. Crack Cunarders, like the Arabia and the Canada, took eleven days to cross the Atlantic: the U.S. mail packet Fulton four or five days longer.

Mr. Reuter never sat down under difficulties. Oriental blood in his veins there might be, but no 'Inshallah' for him: his motto, like Foch's, was 'Attack!' He could not bridge the ocean, but he could shorten the period news took to cross it.

His plan was to intercept the American mail steamer off the extreme tip of the S.W. coast of Ireland. The latest dispatches from the seat of war, enclosed in tin canisters, were put on board the mail-packet at the last possible moment at New York, and thrown overboard to swift vessels waiting off Crookhaven. If the packet passed at night, canisters burning a blue light were used, in case they fell in the sea, and exciting tales are related of the experiences of the Reuter cutters putting off in the teeth of a gale on their perilous mission. To expedite transmission of the dispatches to London Mr. Reuter had a special telegraph line constructed, over many miles of a wild, rough country which would otherwise have to be traversed by jaunting-car, from Crookhaven to Cork, where the dispatches were put on the wire to London. A similar arrangement was maintained at Southampton where The Times also met the American mail by boat and many exciting races for the telegraph office are said to have taken place between Mr. Reuter's boatmen and Mr. Delane's.

Mr. Reuter's enterprise was rewarded by a number of sensational 'exclusives'. The agency was first with the tidings of the release of the Confederate Commissioners, Messrs. Slidell and Mason, who had been seized on board the British steamer Trent by the Federal authorities and was able to give Lord Palmerston early intelligence of the adjustment of an incident which had brought Britain and the Federal Government to the verge of war. When Lincoln was shot by Booth at the Ford Theatre in Washington, Reuter's New York correspondent, by chartering a special boat, managed to overtake the mail-packet and fling a canister containing a full report of the tragedy on board. Thanks to his enterprise, the agency was a full week ahead with the news.

The conclusion of peace in the United States found Reuter's an established institution, and Reuter's telegrams daily occupied the place of honour in the columns devoted to telegraphic news in the English Press. The system was made as far-reaching as was practicable with the limited extent of communication then existing. Agents were appointed in all the important British colonies and the arrangements for the exchange of news with the other European news agencies improved and extended. In 1865 Mr. Reuter, wishing to provide more capital for the extension of his services and feeling, moreover, that the anxiety and responsibility of so vast an organisation were too great to be borne permanently by one individual, converted his undertaking into a limited company, of which he remained the Managing-Director. One of the first tasks upon which the new company embarked was the laying of a cable between Lowestoft and the Island of Norderney, off the Frisian coast of Germany, in the North Sea, which was destined to become the first section of the overland route to India. Four years later, when the Post Office acquired all the telegraphic lines then existing in the British Isles, the Government purchased the cable from the Company. Sir William Vernon Harcourt, M.P., represented Reuter's in the protracted negotiations that took place and the sum obtained for expropriation was so much in advance of what had been expected that a handsome bonus was distributed to the staff.

In 1871 the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha bestowed a Barony upon Mr. Reuter but it was not until twenty years later that, at the instance of Lord Salisbury, he was admitted to the recognised Foreign Nobility of England and allowed, together with his two sons, according to the German practice, to use the title in England. He retired from the Managing-Directorship of the Company in 1878 in favour of his elder son, Baron Herbert de Reuter, and died at Nice, a hale old gentleman full of years and stories, in 1898.

Baron de Reuter must have been a remarkable personality. Farsighted, tenacious, adjustable, the prevision he displayed in being the first to grasp the possibilities of telegraphic communication for the systematic and rapid distribution of news was also seen in the stubborn attempts he made to open Persia to British influence. In this connection a brief sketch of his career, issued by Reuter's at the time of its move to the Victoria Embankment in 1923, says: 'The magnitude of his conceptions is shown by his repeated attempts to carry out the concession granted to him personally by the Persian Government in 1872 for the construction of a railway from the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf with the sole object of serving the common interest of Persia and the country of his adoption. He was so ill-supported by the British Government, however, that Russian influence succeeded in stopping the work after a survey had been made and the first portion of the track prepared.

Nothing daunted, Reuter successively obtained concessions to construct railway lines (1) from Muhammerah to Ispahan; (2) from Schuster to Teheran; and (3) from Muhammerah to Teheran, but only received lukewarm support from the Imperial Government and was not able to proceed although the capital would have been readily obtainable. Persia remained closed to the commerce of the world and the line that would have tapped the more recently discovered oil-well district was never built. As a result of their unenlightened policy, the Imperial authorities, many years later, had to ask Parliament for a vote of two million pounds to ensure the output of Persian oil for the war-ships and vessels of trade. Had the railways been in existence when War broke out in 1914 the position of Britain in that part of the world would have been so strengthened that the whole progress of the Mesopotamian campaign might have been changed, if indeed it had been rendered necessary at all. Part of the Baron's scheme was to effect a junction at Kermanshah with a line that could have been constructed by the Tigris Valley to Bagdad, thus greatly increasing British influence in the Near East.'

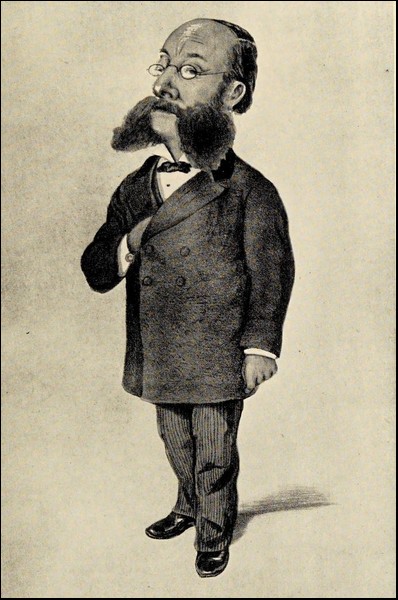

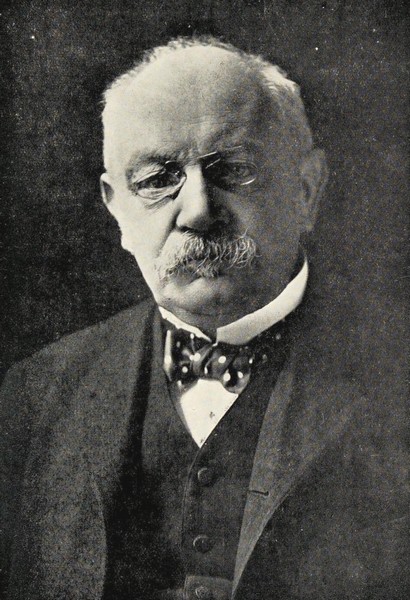

Baron de Reuter (Vanity Fair).

Baron de Reuter's original Persian concession was an immense monopoly, giving him the exclusive privilege of constructing railways, working mines and forests, and making use of all other natural resources of the country, besides farming the Customs. It was annulled in 1889, the Baron receiving the concession of the Imperial Bank of Persia in its place.

A small, dapper man, natty in his attire, with long 'favoris' framing the otherwise clean-shaven face, as you may see him depicted in Pellegrini's 'Vanity Fair' cartoon, Baron de Reuter was a well-known and popular figure in Victorian society. He enjoyed the friendship of the Prince of Wales, Sir Arthur Sullivan and many other notables of his era and his large house in Palace Gardens was the scene of frequent and lavish parties. Although thoroughly British in sentiment, he was to the last, in appearance and manner, the Paris boulevardier type, polished, witty and elegant. He spoke English with a strong German accent and always preferred to speak and write to my father in French.

If genius be the infinite capacity for taking pains, it also comprises the iron resolution not to be diverted from the appointed path. The genius of Paul Julius Reuter did not alone consist of being the first to perceive the possibilities of the syndication of telegraphic news; his greatness lay in his rigid determination that the name of Reuter should always stand for accuracy and reliability. By dint of his unfailing enterprise and natural astuteness he might have made money in those early days by paying more attention to speed and sensationalism and less to accuracy, for, throughout the history of journalism, there have been newspapers to which, as my father used to say, 'A tasty lie is more palatable than a tardy truth.'

But Paul Julius forestalled the modern slogan 'Truth in advertising' by recognising that to create a lasting market, his wares must not be counterfeit: it was he, and he alone who, by personal example and preaching in and out of season, founded the Reuter tradition which is a nobler monument to his memory than that which Fleet Street has forgotten to erect. In the whole annals of journalism nothing, in my opinion, is more strange than that an obscure Jewish pedlar, wandering the highways and byways, should have reared a structure based on foundations as solid as this. On several occasions the world has paid tribute to the Reuter name by accepting, on the faith of Reuter, news of sensational importance as yet unconfirmed from official sources. The Isandhlwana disaster, in the Zulu War, and the death of the Prince Imperial, and the Relief of Mafeking, perpetuated in Mr. Coward's play Cavalcade, were instances of this.

About Isandhlwana (1879) I found this note in my father's papers:

'The news reached Reuter late in the evening from Madeira—ordinarily it should have come by cable from St. Vincent. The telegram began in code, then in the middle contained a lot of English names. Zulu war news was then regarded with more or less languid interest in England. Five sheets had been received up to shortly before I a.m. In those days there were no tape machines to the newspaper offices and the messages were taken round by messenger. On this occasion, however, hansom cabs, then the quickest and most dashing form of London transport, were chartered, and the dispatch got into the newspaper offices before I.30 a.m. The Times had a leader.'

It might be a quarter of a century ago that The Times, quoting, as is still its daily usage, from its files of a hundred years back, reproduced an advertisement: '24 Old Jewry, a comfortable and desirable dwelling-house with garden.' To this solid City mansion, destined to be its home for more than half a century, Reuter's transferred itself in the spring of 1871, what time my parent was dodging bullets in the Paris Commune. The old house, from which Reuter's moved in 1923, is still standing, four-storied, narrow-fronted, with reflectors at the windows to lighten the gloom of one of the narrowest and most historic of London streets, but otherwise retaining very much the outward aspect of its original character as some erstwhile City worthy's home. I speak of it here because it is identified, more than any other place in London, with the history of the journalistic family to which I belong.

For we were a Reuter family. For a round three decades—from his return from Paris in '74 until his retirement in 1902—my father's desk stood in one of the two windows on the second floor of 24 Old Jewry, where the Editorial Room was situated. It was at 24 Old Jewry that my uncle, the late Harry Williams, in his day one of the best-known men in India and for many years Reuter's General Manager at Bombay, joined up, and my uncle, Arthur, who was in the Secretarial Department and was afterwards killed by a fall from his horse in the Market Square at Coolgardie, Western Australia. In that same Editorial Room, gloomy of aspect, low of ceiling with its old-fashioned mantel and open grate, at the age of eighteen I started 'subbing' telegrams and after me my brother Douglas later Reuter's General Manager in the United States, and Chief Editor, even as our father had been; and two of our sisters after us, in the War—it required a world conflagration to open Reuter's Editorial Department to women!

When Reuter's removed to Blackfriars, the greater part of 'No. 24', as we used to call it at home in my father's day, remained empty. Finding ourselves in Old Jewry one afternoon my brother and I decided to visit the old house. It was towards the close of a winter day and the steep and shabby stairs were thick with shadows, those stairs which so many generations of Reuter men have climbed.

Names and faces kept flashing into my mind as we mounted—Frank Roberts, friend of my father's boyhood, who died of cholera in Wolseley's Egyptian campaign: Pigott, who made a famous ride across the desert with the news on the same expedition: Guy Beringer, most charming of Bohemians, correspondent at St. Petersburg, who died from his treatment at the hands of the Bolsheviks: the brilliant but erratic Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett: George Adam, witty and cynical companion of my youth, who became Times correspondent in Paris. When we looked in at last on the Editorial Room and saw it bare and desolate and heard the mice squeak, I caught Douglas by the arm. 'Let's go!' I said. 'The place is full of ghosts!'

I WAS born in London, in the year 1883 and so grew up in a phase of civilisation which has almost completely passed away. My childhood was spent in a London in which horse omnibuses and cabs and the old steam Underground were the sole means of communication. The Underground was the first railway of its kind in the world. With its grimy, gas-lit stations and even grimier, black tunnels, encrusted with soot and perpetually swirling with clouds of sulphurous smoke belched by the locomotives, it was a regular pit of Tophet. Doctors said that the sulphur was good for the lungs, and there were stories of people with pulmonary complaints travelling regularly by Underground for the sake of their chests. The Underground in a fog, especially at one of the riverside stations like Mark Lane (the station for the Tower of London), was a nocturne in madder, with the station lamps glowing redly through the fog that seeped in everywhere, and the fog blending with the sulphurous fumes to make a mixture that caught the luckless passenger by the throat and half asphyxiated him. Once at Baker Street, on a quiet Sunday evening, I saw a horde of rats, the big, brown rats of the London sewers, playing about the rails. No one has any reason to deplore the passing of the old Underground: nevertheless the complete transformation of the system through electrification deprived London of one of its most characteristic and curious institutions.

In the absence of swifter and more convenient forms of transport and of motion pictures and greyhound racing, people living in the suburbs like our family had to content themselves with the more static amenities of the fireside. It was the age of evening parties, at which guests changed their shoes in the hall and those with musical pretensions brought their music and, suitably coaxed, performed; of dinner parties, of dances—always in the home. I have the clearest recollection of being excessively bored at many of these functions—in the present era of restaurant entertaining and night clubs young people, I fancy, have a much better time than we ever did.

Cycling, the humble precursor of motoring as a cheap and handy method of getting out into the country, revolutionised by the bearded Mr. Dunlop's invention of the air chamber tyre, did not enter upon its popular vogue, as a recreation for the masses, until after I went to school. There were many sons of well-to-do parents at Downside, the famous Roman Catholic school near Bath, when I was sent there in 1895 but in the school at that time bicycles were still the exception, the prizes of the envied few. I recall, however, that most of us took in a 2d. weekly called Cycling, which, personally, I would devour from cover to cover—I understood why when, years later, I heard that a young journalist called Alfred Harmsworth used to write the bulk of it.

My mother, who spent the first few years of her married life in Paris with my father, told me that when she first came to London to live in 1874 Welsh women in red cloaks and tall black hats still used to bring round the milk in pails slung from a wooden yoke across their shoulders. At that period few houses had water laid on above the ground floor or basement and the wages of a maid were £12 a year. In my childhood we had three servants at home, our beloved old nurse, Diddie, a cook and a housemaid. I am under the impression that Diddie's wages never exceeded £20 a year, and I remember two sisters from Norfolk, applying for jobs as housemaid and cook, who asked as wages £16 and £18 a year respectively. These, of course, were suburban prices. The year would have been about 1892.

My earliest recollection goes back to the Queen's Jubilee in 1887. I can dimly remember festoons of flags across the streets and more clearly, the front garden of our house hung with fairy lamps and Chinese lanterns at night. There was also talk of a coin called a 'Jubilee sixpence'. Diddie had one mounted as a brooch—rogues used to gild them and pass them off as half-sovereigns.

We lived at Notting Hill which, when my parents settled down there from Paris in the seventies, was a newly-developed suburb, where Watts, the painter, on his marriage to his young wife, who was to become known to fame as Ellen Terry, resided at that time.

As Chief Editor of Reuter's my father was liable to be sent for in a hurry when big news came in. There were, of course, no telephones in general use—the first I ever saw was a private line connecting a coal office with the Paddington goods yards, in the early nineties: even during King Edward's reign telephones in suburban houses were still the exception. So my father would be wired for—on Sundays or at night when he was away from the office—or, as often as not, a Reuter messenger would come out by Underground, all the way to Notting Hill, or, in a special emergency, by hansom.

The 'Rooter' messengers, as they were known in Fleet Street, wore a becoming uniform of grey with green facings which owed its inception, I have heard, to an adroit deal of old Baron de Reuter's in buying up the surplus stock of a British manufacturer of cloth for the Confederacy after the collapse of the South in the Civil War. Their caps with the long, old-fashioned peaks, too, resembled the kepi of that campaign. Years later, when I visited the great Confederate Museum at Richmond, Virginia, that shrine of broken hearts and dried tears, the sight of the cases filled with Confederate uniforms struck a familiar chord in my mind and I found myself thinking of the old Reuter messengers.

It would take my father something over an hour, from door to door, to get to the office, by Underground to Moorgate Street, which was his usual mode of travelling—about an hour and a half if he went by bus. I wonder whether anybody to-day ever reflects upon the tremendous amount of organisation which the wide network of services run by the different London horse-bus companies of those days involved. Horses had to be changed, for which purpose, at stated points, fresh horses with their ostlers were stationed and this meant that stables had to be provided all over the suburbs. Then, in the summer, the horses required to be watered en route and at steep hills, as at Church Street, Kensington, spare horses had to be kept in readiness, day and night, to help pull the laden buses up the incline.

The London bus horses which, at the period of which I speak, mostly ran in pairs, were a good-looking lot, splendidly groomed and cared for. I believe they were specially bred to produce a type of horse broad in the chest and long in the leg, so as to pull well. A certain number were earmarked for service with the Royal Artillery in the event of mobilisation and at the time of the South African War a story was current that, to start up teams with the guns, the gunners would slap the gun-carriage and cry 'Right be'ind!' after the manner of the London bus-conductors.

I can remember straw in the bottom of the buses in winter and the dim oil-lamps that lit their interiors at night, and the 'knifeboard' tops that survived on the famous three-horse Madeleine-Bastille buses in Paris long after their disappearance in London. There were seats beside the driver, two on either side of the little throne on which he perched, with his shiny top-hat and rug folded about his knees. The late Lord Rothschild made a practice of sending every bus-driver in London a brace of pheasants from his place at Tring at Christmas, in return for which on Derby Day each year ribbons in the Rothschild racing colours fluttered from every whip. It was customary when you rode beside the driver to give him a penny tip—I suppose in token of appreciation of his careful driving.

I recall the first appearance of the so-called 'garden seats' on the tops of buses—seats ranged one behind the other as at present. No women ever thought of riding on the knifeboard, but the introduction of garden seats changed all that. There used to be a queer, three-horsed bus—an Atlas, I think it was called—with a large glazed parasol permanently stretched above the driver—its route lay along the Tottenham Court Road. And I have a hazy remembrance of an exciting light green bus—exciting because it took one to the Zoo from Oxford Circus. It was a one-horse affair and had no outside seats and no conductor—you put your penny in a box inside. There was also a halfpenny bus that went across Waterloo Bridge.

When I first joined Reuter's in the year 1902 I used to cycle to and from the office through the heart of the traffic. Looking back it seems to me that at busy centres like Oxford Circus and the Bank there was as much congestion as there is to-day. And I would not swear that at present the current of traffic moves a great deal faster—the horse buses used to average ten miles an hour over their routes while the speed of a hansom with a good horse was about fifteen. A characteristic feature of City traffic used to be the small, red-jacketed scavenger boys who, with brush and pan, darted in and out of the horses' hoofs, scraping up the horse droppings.

Then as now the streets were noisy. The volume of sound remains substantially what it was, only the note has changed. In those days huge drays rumbled and unsprung carts crashed over the macadam, asphalt or wood paving; drivers cracked their whips and shouted at the horses; bus drivers and conductors called their destinations at every stop—'Benk! Benk! 'Ere you are, lady! A penny all the way!'; hansom cabs jingled bells like sleighs. If I had to select one characteristic sound to typify London at the end of the nineteenth century it would be the silvery jingle of bells mingled with the fast clop-clop of hoofs—the music of the hansom cab.

It is not my purpose to review the whole of the cataclysmic changes which the War brought in its train, not only in England, but everywhere. I am rather concerned with picking out, here and there, certain high lights as, glancing back over a period of half a century, I descry them. Of these one of the most clearly visible is the standardisation of women's types.

It was Alfred Harmsworth, I believe, who was the first to realise—at any rate in this country—that women are the most important consumers and therefore, the most diligent readers of advertisements. His Daily Mail, founded in 1896—'it's Park Lane or the poor-house, boys!' he cried gleefully, as the last formes were locked away on that momentous evening of May 29th which was to bring him fortune and a peerage and revolutionise the British Press—was the first newspaper to cater definitely for the woman reader. To-day all over the world advertisers are angling for the housewife's patronage.

In my youth as in this year of grace Paris created women's fashions. At that time, however, the latest styles were only for the wealthy and the less well-to-do had to wait until the wholesale trade had copied them and brought them within reach of the middle-class purse. The so-called lower classes—the shop assistants, the domestic servants—were content to dress themselves in modes that limped a long way after the prevailing fashion while the country folk—farmers' wives and the like—continued to follow styles which had been in vogue ten, twenty or thirty years before. So did many elderly women of means. The stage is a fairly good guide to current fashions. Well, when W.S. Penley wished to characterise a wealthy and eccentric old lady in Charley's Aunt, produced in the nineties, he dressed her in the style of the sixties, so that the audience should recognise her for what she was supposed to be, an elderly maiden aunt.

One result of this leisurely percolation of the Paris mode was that women's types were everywhere sharply differentiated. When my mother lived in Paris the streets in the morning, she used to tell me, were full of women, bareheaded with beautifully brushed hair, in stiffly pleated snow-white skirts or in their peasant dress bonnes out marketing. Such types were still to be seen in Paris when I paid my first visit there in 1903 but, save for a few Breton nurses in national dress, they are no longer to be encountered to-day.

At that period one could usually distinguish a German girl by the amplitude of her curves and the beauty of her tresses which most of them wore, à la Gretchen in Faust, braided about the head. Also German women were the worst-dressed in the world. On leaving school in 1901, for the purpose of learning German, I spent a year in a family at Cleves*, a small town on the Lower Rhine, known in history as the birthplace of Henry VIII's rejected spouse, Anne of Cleves. Cleves had about 15,000 inhabitants and I moved in such society as it boasted. Believe it or not, there was not a single girl or woman in that town that was dressed within two or three or even five years of the current mode. And Berlin, when I arrived there as Reuter's correspondent in 1904, was scarcely better. German women in those days had little money to spend on their appearance and those who had it, no taste. Both at Cleves and Berlin I met plenty of pretty and charming German women, but I could number on the fingers of one hand those with the slightest claim to chic.

* Now "Kleve".

The vastly increased importance of woman as consumer, coupled with the influence of the motion pictures, has changed all that. The popular Press throughout the world publicises the latest Paris trend almost before it has reached the showrooms of the couturiers and the moment a new style is launched, the wholesale trade, which has bought the model honestly, and the copyists, who have stolen it, get to work. More than this, the movies and the exquisitely turned out fashion photographs in the women's periodicals display types, not only of clothes but also of feminine loveliness, upon which, irrespective of nationality, the modern young woman delights to model herself. The result is that, wherever you go to-day, you are confronted by Greta Garbos, Marlene Dietrichs and Joan Crawfords, not to mention the much publicised society belles of Europe and America.

This catering for the woman consumer has altered the very countenance of the world's capitals. Oxford Street in London, Fifth Avenue in New York, the Boulevard Haussmann in Paris, are now the daily Mecca of hordes of bargain-hungry or desultory 'window-shopping' women, and the same is true of the shopping centres in every considerable city of the globe. As long as I can remember, Oxford Street was a busy thoroughfare, but even at Christmas-time, in the years of which I write, its pavements were never so congested as they are to-day.

William Whiteley, Universal Provider, device two globes, was the great department store in our neighbourhood; it was indeed one of the most considerable, as it was the earliest, in London. As a child I often saw the old Pasha himself, destined to be murdered by his natural son, with his frock-coat and long weepers, acting as a sort of super-shopwalker. Whiteley's used to pride itself on being able to produce anything, including, it is said, a consignment of fleas for Alfred de Rothschild's private zoo at Tring. I only know that, as a young reporter, I once traced an authentic case in which Whiteley's had supplied a best man at a wedding. The happy couple came from Cork and, knowing no one in London, applied to Whiteley's. That enterprising emporium came up to scratch and produced a shop-walker from the silk department, a very personable and unaffected young gentleman, as I remember, when I interviewed him at his lodgings near Westbourne Grove.

One of the most striking changes that has come over the British public in the period which has elapsed since my youth is in its attitude towards the Army. In my early days traces were still discernible of the Iron Duke's not always concealed opinion that the rank-and-file, as a whole, were a precious collection of scallywags, as in his heyday to a certain extent they were. Soldiers in uniform were excluded from the saloon bars of the public-houses and refused admission to any part of the theatre except the gallery. When I had a flat at Clement's Inn, shortly before the Great War, the outside porter, an ex-colour-sergeant of the Coldstream Guards, and a man of irreproachable character, told me that when, having enlisted, he went home to Yorkshire to show himself in uniform to the family, his father, a hard-headed farmer, met him at the door and sternly ordered him out. 'I'd sooner see ye dead in your coffin,' the old man cried, 'than think that any son of mine would disgrace himself by taking the shilling. Go ye back across that threshold and don't ye darken my doors again until ye've taken off that scarlet coat!' It was not actually until the South African War, which brought so many volunteers flocking to the colours, that this old prejudice began to disappear.

My earliest impression of the British Army centres about the rear view of the doughty old Duke of Cambridge, who was Commander-in-Chief for so many years that, if my memory does not betray me, they had to abolish the post in order to get rid of him. There was a good deal of it—of the rear view, that is—and the most conspicuous part of it was clothed in white buckskin breeches. In scarlet Field-Marshal's tunic, plumes tossing and sabre clattering, the old gentleman went cavorting across that salubrious champaign known as Wormwood Scrubs—at that time a regular place of exercise for the Household troops—screaming incoherently at the glittering staff about him. One small boy among the spectators was convinced that some major catastrophe had befallen for he had yet to recognise, from personal experience, the authentic note of frenzied objurgation in which, from time immemorial, senior officers in the Guards have voiced their displeasure. On the occasion in question his nurse's awed 'Look! It's the Dook!' identified for him that Prince who is affectionately remembered in the ante-rooms of British messes to this day as the author of a celebrated obiter dictum in regard to the deplorably promiscuous tendencies of young officers.

I caught a glimpse of Queen Victoria only once—you must remember that in the years within my recollection the Queen was very seldom seen in public—a little old lady in black satin with a mauve sunshade, round as a ball, emerging in a carriage from Paddington Station. It is interesting to recall that, on the Queen's arrival at or departure from one or other of the big London termini, the red carpet was spread all the way from the train to her carriage. I remember being struck by the curious almost acidulous reluctance of her smile, much boomed about that time in a press photograph labelled 'Her Majesty's Gracious Smile'. I was reminded of it, years afterwards, when I was received at the White House in Washington by President Coolidge. He, too, had the wry air of biting into a lemon when he smiled—he looked as if he had been 'weaned on a pickle', Alice Longworth, Theodore Roosevelt's brilliant daughter said of him. But his was a poker face in repose, whereas I thought that the Widow of Windsor looked downright peevish.

Queen Victoria was a respected rather than a beloved figure in my youth. She instilled awe and the nation was proud of her as an institution; but she was much criticised. My father was an ultra-loyal citizen, whom the rank sedition talked by some of our Irish friends in London at the time of the Boer War drove perfectly frantic. But he and others like him resented the Queen's almost complete withdrawal from public functions after the Prince Consort's death and were not afraid of saying so. They also disapproved of the way in which she kept the Prince of Wales sequestered from any participation in the business of State. The real fact of the matter is that the old Queen's conception of the monarchy grew, during her long and glorious reign, as much out of date as the installation of the Royal residences and raised a barrier between her and her people which only her death broke down.

MY mother was a seventh child, and as I was her seventh, I suppose I should attribute to that circumstance such luck, as life has brought my way. One can be grateful for having enjoyed more than a fair share of good fortune without questioning the truth of 'Jacky' Fisher's definition of luck as 'the careful previous calculation of what you will leave to chance'. Such, at least, has been my experience in life. Fate is a foul fighter and no fellow can guard altogether against its blows below the belt. But in my experience the consistently successful people I have known are those who habitually leave no contingency unprovided for except the little final nudge that tips the scale in favour or against. Émile Gaboriau, whom, as the father of the roman policier, all detective story writers should salute with a wide sweep of the hat, says in one of his novels, 'There is a master who without effort surpasses us all, and that master is chance.'

My mother's is among the oldest families in Ireland. The Skerretts of Finavara, in the County Clare, were one of the so-called Fourteen Tribes of Galway, settled on the shores of Galway Bay since the thirteenth century. Each of the tribes had its qualifying adjective by which it was traditionally described, as, for instance, 'the litigious Lynches' 'the sporty Martyns'. The Skerretts were always 'the positive Skerretts'. The name of Skerrett is said to have been originally Huscared which, I have heard, is Basque for 'black', and the first Skerrett is reputed to have come over to Ireland from Bilbao, in the Spanish Basque country, in the train of the Norman knights. That some trace of the Basque survives in our family is suggested by the fact that I who have inherited the ruddy complexion and black hair of my forbears, when staying at St. Jean de Luz some years ago was hailed as a brother Basque by the pelota players who frequented the humble and very typical Basque restaurant where I took my meals.

Skerretts have played their part in history. One, Nicholas, was Archbishop of Tuam in the sixteenth century and is referred to in old records as belonging to an Irish family 'even then very ancient'; while another, John Byrne Skerrett, who raised a battalion of Galway Fencibles, commanded a brigade in the Peninsular War under Wellington, was promoted Major-General and was killed at the disastrous night attack on Berg-op-Zoom in 1807. His heroic death and that of General Gore who fell with him are commemorated by a monument in St. Paul's. Branches of the family are scattered throughout the world. In the person of the late Sir Charles Skerrett, a Skerrett was Chief Justice of New Zealand and in the United States the Skerretts of Germantown, Pennsylvania, are descendants of a Skerrett who emigrated to Ohio about 1820. Years ago, at a luncheon party in Berlin given by the late Charles R. Flint, a well-known American business man, I identified a member of this branch, who happened to be my neighbour at table, by his signet ring which bore the seal, a squirrel, and motto 'Primus ultimusque in acie', of the Skerretts. He was Robert Skerrett, then in the Navy Department at Washington.

Early in the eighteenth century the senior branch of the family, which was my mother's, moved from Galway to Clare. The family seat of Finavara (which means in Irish 'Queen of the Sea') still survives, though shorn of its ancient glories. Four-square and stark it faces the Atlantic Ocean in what, until Henry Ford brought out his celebrated 'T' model and revolutionised transport, was surely one of the wildest and most inaccessible parts of the west coast of Ireland. Before they had a Ford in the village it was a three-hour drive by jaunting car from the railway at Athenry over rough roads that wound their way between stone walls fencing barren fields where goats picked a miserable living among the limestone rocks and the acrid turf smoke curled up into the soft West of Ireland rain from the tiny white-washed cabins. It was on this drive that, when a schoolboy, for the first and last time in my life, I heard 'keening' at a funeral. Villagers bore the coffin up a winding path to the churchyard and behind the bier a cluster of women wrung their hands and sobbed aloud on a curious, high-pitched note.

Seals play on the rocks at the foot of the lawn at Finavara, which broods over the grey-green Atlantic outstretched before it and the naked brown hills that sentinel the bay. From the drawing-room windows, 'Faith, an' ye cud see America if ye had the eyes,' Coly Fahy, the lodgekeeper's son, who used to take me fishing for mackerel and sea-trout, would tell me.

The peasants are Irish-speaking and at the local church the non-Latin prayers are recited, and sermons preached, in Irish. It was from an old tenant of Finavara, a certain Martin Minogue, that Lady Gregory derived much of the dialogue of her Irish plays. Martin was a character, and like so many of the Irish peasantry of that type, he revelled in being a character, and I have always had an uneasy feeling that, in rolling forth in his soft and caressing brogue the picturesque, poetic phrases in which he delighted, he was talking for effect—mind you, there's nothing entrances the Irish peasant more than a little, gentle leg-pull. In my young days Martin, who was a rare old humbug, was a great crony of mine. He had only one eye, and, as Dickens said about a similar lacuna in Mr. Squeers, popular prejudice runs in favour of two: I can still see him winking it at me and saying, 'Sure, an' isn't your honour's family an' me own th'ouldest in Ireland?'

The Major Skerrett who built the house—incidentally, it never had a bathroom or any water laid on above the kitchen or any light save lamps and candles—seems to have been a bit of a rake (he was known locally as 'the wicked Major'). My mother once told me that, when she was a small girl, a couple of harmless old peasant men, openly called Johnny and Paddy Skerrett, and bearing a marked resemblance to the men of the family, haunted the kitchens of Finavara and did odd jobs about the house. The major died before his only son, my grandfather, was born, so that the heir, succeeding as a minor, was known throughout the countryside, and especially in the hunting field, where he was a popular and familiar figure, as 'Minor Skerrett'. A sturdy figure with round face, blue eyes and bushy black whiskers, he farmed and hunted and went up for the season to Dublin where he owned a fine Georgian mansion in Mountjoy Square, now alas! given over to slums. He died of a chill caught out hunting, before I was born.

My grandmother, who married my grandfather at the age of seventeen, bore him ten sons and four daughters. She was a MacMahon, of old West of Ireland stock, and her family was friendly with Daniel O'Connell. In her old age she liked to tell us children how, as a young girl, she drove through the streets of Ennis with the Liberator. In the romantic fashion of those days the grateful citizens presented him with a laurel wreath which, with a courtly gesture, he placed on the dark hair of the maiden at his side, gallantly saluting her with a kiss.

The Hunger of 1845 all but ruined my grandfather, as it ruined so many Irish landowners. He gave all he could spare to his starving tenantry and as Deputy Lieutenant and J.P. co-operated actively in the relief measures instituted by the British Government. I have seen some of the elaborate and punctiliously worded letters he exchanged with sundry great English noblemen sent from London to administer the relief. The stone walls which to this day meander aimlessly up and down the barren hills upon which Finavara looks out speak of the purposeless tasks to which, under the austere, reforming eye of Queen Victoria's Ministers, the peasants were set, in return for food.

By that strange fatality which seems to hang over so many ancient Irish families, all but one of the ten Skerrett boys were in their graves before reaching the age of fifty. Several of them lie buried with my grandfather in the Skerrett family vault in the ruins of Corcomroe Abbey, a romantic and beautiful spot, where the peewits cry and the trees rustle their branches against crumbling arch and fallen pillar. They were all big men, handsome and with charming manners, living hard and drinking hard, after the manner of the Ireland in which their adolescence was spent, keen sportsmen, who shot and hunted and fished. They belonged to the Catholic gentry of Ireland, men of parts, who had received a classical education at good Catholic schools in England, so that they could quote a tag from Horace with the best: several of them took degrees at that renowned seat of learning, Trinity College, Dublin.

Their tragedy was that the estate, already impoverished by the vicissitudes of land tenure in Ireland and encumbered by debt was no longer able to support so many of them. Four entered the army, one was lost at sea, one, as in most Irish Catholic families, became a priest. The priest uncle was called Hyacinth, a Christian name that is less uncommon in Ireland than it is in England, and as 'Father Hycie' was widely known through Clare and Galway. To this day the old folks at Finavara love to tell stories about 'Captain Willie', the eldest son, who, on my grandfather's death, resigned from the army and took over the management of the estate. By all accounts he was the biggest and the jolliest of the brothers, with a chest measurement of 48 inches, I have been told. One of his wilder exploits, still talked of over the turf fires on winter evenings, consisted in driving a tandem at breakneck speed in the dark down Corkscrew Hill, a dangerous descent in the neighbourhood of Finavara, on his way back from Galway Races: anyone who has been to this celebrated West of Ireland race meeting knows that sobriety is not the strong point of the crowds attending it.

To-day there is no male Skerrett left to carry on the line, for the last male survivor, my cousin, Charles Skerrett, died in 1936, as a monk in Belgium, a Benedictine of the famous Abbey of Maredsous, without ever having married. And so the ancient line is extinct, and the old house, to-day a mere shell of its former self, gazes forlornly out over the bay where once the strapping Skerrett boys swam and fished and sailed the Banshee, the family ketch, in the wildest of weather across to Galway City for supplies.