RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

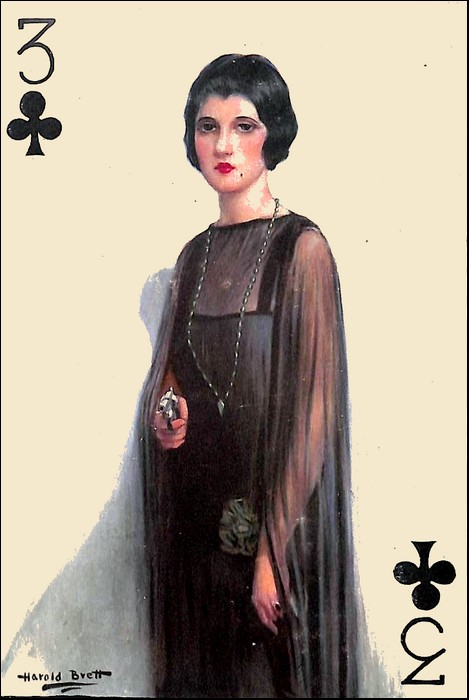

"The Three of Clubs," Houghton & Mifflin, Boston and New York, 1924

"The Three of Clubs," Houghton & Mifflin, Boston and New York, 1924

"The Three of Clubs," Houghton & Mifflin, Boston and New York, 1924

What mysterious significance has the three of clubs? Stuck in a menu-holder, it marked a corner table at the old Munich Hofbräuhaus, where sundry quiet men conversed in undertones. The Austrian, Von Bartzen, found it fallen face upwards between his elbows at Monte Carlo. It was at Borchardt's restaurant in Berlin that Colonel Trommel, late of the Great General Staff, discovered it lying by his plate. Godol, the Hungarian, had it from a match-seller in the Arcades in Milan. And perversely it united the love and fortunes of Godfrey Cairsdale and Virginia Fitzgerald.

Valentine Williams has never been more successful than in this story of wild adventure in the English secret service. "The Three of Clubs" is a swift and thrilling romance of love and mystery, a game of international intrigue played for colossal stakes and with all Europe for the gaming-table.

THE three of clubs....

From the cards strewn amid the brimming ashtrays and torn score-sheets of the abandoned bridge table I have picked it out to freshen in my mind the story of Godfrey Cairsdale and Virginia Fitz-Gerald, which here, in the quiet of the evening, I have sat down to write.

Such a common little card.... Not opulent like a diamond, not romantic like a heart, or even mysterious like a spade.

Just a plain, ordinary club....

And yet, when at Venice, from a window above the private landing-stage of the Danieli, on the narrow canal that quietly laps the dank and frowning walls of the Piombi, it fluttered down to a gondola, the white hand that picked it up trembled as it divided the black curtains.

When, in the baccarat rooms at Monte Carlo, the Austrian, von Bartzen, sitting absorbed in the play, found it fallen face upwards between his elbows, the blood ebbed from his face and, though he was whining, he left the Casino on the instant.

It was at Borchardt's restaurant in Berlin that Colonel Trommel, late of the Great General Staff, discovered it lying by his plate—Borchardt's, that stronghold of the old Prussian Army, where in bygone days one saw field-marshals' batons hanging up in the cloakroom among the spiked helmets and swords. And Trommel abandoned his oysters on the spot, and, having borrowed a hundred thousand marks from the head waiter, made straight for the train.

And there were others....

At Stuttgart, in the restaurant of the Hôtel Marquardt, the exquisite von Winterbaum, survivor of Richthofen's famous "flying circus," saw it protruding from the lining of his hat, and his face paled beneath its tan.

Godol, the Hungarian, had it from a match-seller in the Arcades at Milan. He did not stop to ponder the oddness of the intermediary or regret the brief holiday he had planned by Como's blue waters; but, turning his back on the pigeons wheeling in the Piazza del Duomo, headed instantly for the chilly north again.

Stuck in a menu-holder, it marked a corner table at the old Hofbräuhaus at Munich where, in the greyness of a December afternoon, sundry quiet men quaffed their beer and conversed in undertones. For weeks its three black clover-leaves haunted the mind, waking and sleeping, of a certain broad-shouldered Englishman, Him Whose Name Must Never Be Spoken, who, all unconsciously, helped most strangely to shape the lives of the two young people whose story I shall here set down.

Less famous than the nine of diamonds, which men call "The Curse of Scotland" in everlasting execration of the name of Campbell, this humble pawn of the pack has played its part in history.

The three of clubs, too, has lived its little hour....

FROM the distant ballroom resounded the slow and plaintive rhythm of the tango. For his great reception in honour of the Arms Conference the Ambassador had sent specially to his estancia for this band of native players, black-haired, sad-eyed, who seemed to pluck their very hearts from the strings of their guitars. The brooding melancholy of the vast spaces of the Argentine, the romance of love beneath the stars, the throbbing passion of old Castile, were interwoven in the strange sad melody that, with its monotonously recurrent beat, went forth for official Washington to dance to.

They were playing bridge in the long gallery adjacent to the library. Through the open door the young man and the girl who sat on the Récamier couch, surrounded by His Excellency's Elzevirs, caught fragments of the players' talk—the lingua franca of an international conference. "Hearts": "Je passe!" "Double hearts": "Caro mio, a voi"; "Prince, my fan..." and among and above it all, mingled in the muted strains of the music, the confused sound of many voices, the scarcely perceptible aroma of tobacco.

"And you're really sailing in the morning?" said the girl, regarding her companion through her long lashes. "It won't seem like the Conference without you..."

"My dear," he replied, "if you only knew how I hated to go. But they're thinning out the Delegation, and I'm wanted at home...."

His voice shook a little. Suddenly his two arms went out. His hands rested on the girl's shoulders.

"Jenny," he said, "I must speak. I can't go home without telling you. My dear, I love you so.... I love you... ."

He drew her passionately towards him. The girl did not resist. Her face was close to his.

"Jenny," he asked, "do you care.... at all?"

She remained motionless, impassive, but there must have been something in her eyes that emboldened him, for he leant down and kissed her on the lips. This time she responded and, with a little sigh, settled down in his arms.

"My dear," he said. And again: "My dear...."

He would have kissed her again, but she put up her hand.

"Jenny, dear," he asked, stroking her hand, "could you marry an Englishman?"

The girl looked up at him and smiled fondly.

"What I like about you, Godfrey," she said, "is that you always seem to read my thoughts. My dear, that was just the question I was asking myself. I believe I could marry you. But could I give up my work, my country.... this?"

He kissed the tips of her ringers. "I should never let you regret it," he said. "About money and all that, you know I'm comfortably off, even according to your standards, and if anything happens to dear old Jack, I shall succeed to the title...."

"I wasn't thinking of that, Godfrey," the girl broke in.

"I know. But these things matter in marriage. And the first thing your uncle will do will be to enquire into my circumstances. It appears there's a slump in English fortune-hunters in America, he was telling me the other evening...."

The girl laughed merrily.

"Oh, Godfrey, how frightfully rude of him!"

The young man grinned.

"Oh, I don't know," he said. "Only cross-examination by the indirect method, I suppose. But, Jenny, won't you let me speak to Uncle Andrew?"

The girl shook her blonde head.

"No, Godfrey," she replied. "Not until I know my own mind. We mustn't make a mistake, you know. I care for you too much to risk that. And some woman has made you very unhappy once in your life already...."

He looked up quickly. His eyes were very sad.

"How do you know that, Jenny?" he asked.

"By... by everything about you," she answered. "You probably don't realize how narrowly you've escaped becoming a woman-hater, Godfrey. The first time we met I simply loathed you...."

"I was damnably rude, I admit," he said, smiling fondly at her.

"No, not rude," the girl corrected him. "Unsympathetic, cold, and, worst of all, full of allowances for our poor feminine understanding...."

This time he laughed outright.

"By Gad, Jenny, what an ambassador you'd make! It seems a shame to rob the American Diplomatic!"

"Some of us Americans think they have no brains to spare, believe me!" the girl remarked comically.

He took her hand again.

"Jenny," he said earnestly, "aren't you going to give me any hope?"

Slowly the colour mounted in her cheeks.

"Godfrey," she pleaded, "don't make me answer now. Give me a little time!"

"To-morrow," he replied, "I go back to a world where the sun will never shine for me. Jenny, you've made Washington seem like Paradise. Whether you take me or not, I shall always think of dear old Washington as some enchanted garden, a fairyland of happiness. There was a time in my life when I thought I should never know happiness again. But you have proved me wrong, and the thought of that happiness escaping me once more is almost unbearable...."

"Godfrey," she said softly, and took his hand. "After Christmas I am going to Europe with Aunt Marcia. She lives in Paris, you know, so we are going by the French line to Cherbourg. If you will meet me in Paris, I will give you your answer then!"

He bowed his head.

"Very well," he agreed. "But, Jenny, dear, won't you let me give you a ring? You have nothing of mine to wear except that rotten little watch. And that was a bet!"

"Oh, Godfrey, it's charming!" cried the girl, looking at the tiny platinum watch on her firm white wrist. "I simply love it. And I won't have a ring of yours until I'm entitled to wear one!"

"Still," the young man persisted, "I'd like there to be tangible link between us, something to span invisibly the thousands of miles of tossing water that are going to separate you from me...."

For an instant she let her clear blue eyes rest on his face. Then slowly she drew from her left hand the only ring he had ever seen her wear. It was a flat narrow band of gold, perfectly plain. He knew it for an heirloom in her family, handed down from those Leinster FitzGeralds, that race of splendid men and lovely women from which she sprang. Silently she held the ring out to him, turning it so that he might see the inscription engraved within.

His face lit up as he took the ring. "In Fay the" was the motto it bore in characters half obliterated.

He kissed the small gold circle and slipped it on his little finger.

"Let that be the link between us!" she said in a low voice.

Then he took her in his arms again....

And now she had come three thousand miles to give him his answer. Leaning back in her chair, Virginia FitzGerald contemplated her neatly shod feet below the fur edging of her frock. She still seemed to feel the shivering and swaying of La France which had landed her at Cherbourg that morning out of the grey winter fury of the Atlantic. But she had no sense of discomfort, only a feeling of peat lassitude, a desire to rest quietly, not from the fatigues of the voyage, but from the surge of new impressions which each return to Europe brought her.

It took her always a day or two to get back into the ways of Paris. This time it was two years since she had been over, and the period, which had included the Arms Conference at Washington, had gone far to change the face of Paris as she had known it in the days of the Big Four.

For now, at the hour of le five o'clock, the lounge of the Ritz, Virginia decided, looked quite its old self. Gone were the muddy khaki, the horizon blue, the unreality and the hysteria of the Peace Conference. As from some vast storeroom, she reflected whimsically, had returned the monocled, waisted young men, the elegant women whom the war had whisked away. The creamy sheen of pearls on white necks, the flash of diamonds on soft bosoms, a woman's belongings on a tea-tray—a gold mesh bag, an enamel cigarette-case, two purple orchids, piled picturesquely in a heap; the deft, impassive waiters, the darting blue-and-silver pages, the discreetly modulated music, denoted the return to normalcy.

Outside, on the Place Vendôme, Napoleon, who had seen Zeppelin and Gotha rain fire on the city and had watched winged death come swooping without warning from the distant forest, still gazed from the lofty isolation of his column across the rain-swept gardens to where his majestic tomb lay beneath the golden dome. Far below, at his feet, before the Ministry of Justice, the muddied cars of war were now replaced by the glittering limousines of peace, whose chauffeurs yawned and stamped and gossiped beneath the yellow lights of the hotel portico.

Paris! All her life she had loved it. The spacious spirit of the great Rodin now brooded over the Convent of the Sacred Heart where, as a little girl in a pigtail, she had learnt her first lessons from the gentle nuns. Paris has an elusive charm, a charm that requires to be wooed. Virginia felt that she was not of, but as yet merely among the elegant throng that filled the warmed air of the Ritz on this January afternoon with chatter and low laughter, with the fragrance of its perfume, the exotic scent of its cigarettes.

She recognized, but was too occupied with her thoughts to bestir herself to greet many of those present—an Italian ambassador, a Rumanian princess, a French general, a Greek financier: for her work as confidential secretary to old Andrew FitzGerald, of the State Department, her uncle and guardian, had given her more than a nodding acquaintance with the Almanach de Gotha. But to-day, she told herself, she would banish the outer world from her ken, reserving herself uniquely for her meeting with Godfrey.

She glanced at the little platinum watch. The first train from London was in, the hotel porter had said. The second train must have arrived by this. She had thought that Godfrey might have met her at the Gare Saint-Lazare when the Cherbourg boat special came in. If he had come by aeroplane he could have done so. But perhaps the bad weather had suspended the air service.

She had cabled to him from New York that she would arrive at the Ritz in Paris on January 5th. The inability of Aunt Marcia ever to make up her mind, combined with an attack of influenza which had sent the worthy lady to her bed for a week, had played havoc with Virginia's plans. Their decision to sail by La France was taken suddenly, at the last moment, and she had not had time to write to Godfrey and arrange things. But they were in constant correspondence, and she knew from his letters that he would be in London over Christmas, having been transferred back to the Foreign Office from Budapest, where he had been posted after the Washington Conference.

It was curious that he was not there to meet her. Yet he had had her cable. The American Beauty roses, with their unsigned message "In Faythe" on the card attached, which she had found in their stateroom on La France, had told her that. He must have cabled to order the flowers. But why had he not cabled to her? Why was he not here?

SHE put the problem from her mind. His cable might have missed her; he would telegraph; perhaps he had written: maybe he was detained on business and would arrive in person any minute. Her faith in Godfrey was absolute. Her happy, practical nature had no knowledge of the doubts and fears that haunt so many lovers. She thought pleasurably of their coming meeting. How would Godfrey fit into the European background? Would he survive the confrontation with the mind picture of him which she had carried about with her all these months?

Godfrey I Dreamily she turned her mind back to their first meeting. The recollection brought a smile to her lips. An important communication from the State Department to the British Delegation had gone astray. Both sides denied liability. The Honourable Godfrey Cairsdale, Second Secretary in His Britannic Majesty's Diplomatic Service, attached to the Delegation, had been deputed to investigate the matter. His rather acid comments had been referred to Miss Virginia FitzGerald, confidential secretary to the Honourable Andrew FitzGerald, of the State Department.

When he had called she had not known his name or, indeed, anything about him. She had found herself confronted with a tall, athletic-looking young man, with crisp, dark hair and a straight Grecian nose whose arched nostrils corroborated the evidence of high spirit seen in the keen, luminous eyes. He had been polite—in fact, his manners were delightful—but severe, with a suggestion of scornful compassion addressed to her sex which had exasperated her.

A word from her would have settled the whole thing. Had she not in her hands absolute proof of the receipt of the missing document at the British Delegation headquarters? But it had pleased her to play with him, watching him grow more and more heated as she remained cool and unmoved.

"You do not seem to realize, Miss FitzGerald," he had said at last, "that my Chief is excessively annoyed at this. He requires me to clear the matter up. I don't wish to tell him that I have received no assistance...."

Then, sweetly, she had exploded her mine. She had produced the British Delegation's official receipt. With inward amusement she had watched him flush up with embarrassment and anger—anger with the idiotic clerk who had muddled things up, anger with her for leading him on.

But they had met again and often enough to have laughed together over their first official encounter. Godfrey Cairsdale was something in the nature of a discovery to Virginia. Of course, she had met Englishmen before, but never one quite like him. In every outward characteristic he was essentially British, impeccable good form in demeanour and clothes, extremely insular in his outlook (as she frequently told him), laboriously careful to suppress the manifestation of many of the emotions that large-hearted, impulsive America carries on its sleeve.

Yet there was plenty of character at the back of the rather impassive mien which Godfrey Cairsdale turned to the world, intelligence well above the ordinary, keen humour, a sense of romance. Rather to her surprise Virginia learnt—little by little, from others, for he was hard to persuade to speak of himself—that he was a first-rate linguist, an Honours man at Oxford, and that a small book of his on Roman archaeology was spoken of with respect by no less an authority than the Director of the Metropolitan Museum. On the other hand, his golf approached the first-class standard and his play in a friendly game of tennis at the New York Racquets Club against the brilliant and graceful Kinsella had enthused the dedans.

And passion smouldered behind those steady grey eyes of his. That night in the quiet library at the Argentine Minister's at the reception to the Conference, when Godfrey had put his arms about her, he had told her of his love in a voice that he could scarcely master. She had been strongly, strangely drawn to him.

But she was in love with her liberty. She did not approve of marrying out of one's own nation, she told herself. Always she had before her the example of Aunt Marcia, who, at the age of eighteen, had left her Southern home to marry a French nobleman, the Marquis de Kerouzan. Only his death occurring just before the war had put an end to that gentleman's innumerable extra-connubial escapades which, during his lifetime, had followed one another like beads upon a rosary. In falling out of love with her husband, the Marquise de Kerouzan had fallen in love with Paris. She paid frequent visits to America, but in Paris she made her home.

Aunt Marcia was not in Virginia's secret. Nor was Uncle Andrew. In fact, the girl had confided in no one. To tell the truth, she was by no means certain of what her answer to Godfrey Cairsdale should be. Plenty of young men had been and were in love with her, rich young men and poor young men, socially eligible young men and frank adventurers. But none had been able to offer her sufficient inducement to make her even contemplate abandoning the strangely fascinating work of diplomacy to which her uncle had introduced her. None, that is, except Godfrey Cairsdale....

For three months she had been searching her heart for her decision. Ultimately she had disposed of the problem by telling herself that when she saw Godfrey again the answer would just have to come of itself. Undoubtedly, she had missed him. She had been strangely lonely in Washington after his departure. And the thought that she was about to see him again thrilled her unexpectedly....

A small procession approaching her table interrupted her train of thought. It was headed by Clement, the maître d'hôtel, walking sideways like a crab, his two arms gracefully balanced in the manner of a male dancer of the Russian Ballet, one hand pointing, the other beckoning. These gesticulations were rendered necessary by the extremely slow progress among the crowded tables of the Marquise de Kerouzan who, her plump, good-natured face wreathed in smiles, struggled gallantly along in Clement's wake, a small page, almost vanishing beneath a huge sable wrap, at her heels.

Like most fat people, Aunt Marcia was kindliness personified. Though her figure was plump and stumpy, her French often amusingly erratic and permeated by a little Southern drawl, her devotion to the Republic of her birth uncompromising, mainly through sheer good-nature she held an established position in that curious oligarchy known as "Le Tout Paris," or as we might say, "The Upper Ten." And Society, as assembled at the Ritz for tea, warmly acclaimed her on her return. Every five seconds she stopped to let a man kiss her hand, to exchange a greeting with some mondaine or to throw a smile or wave recognition to some acquaintance in the background. Each time she stopped, the diminutive chasseur, blinded by his furry burden, bumped into her.

"There!" said the Marquise, cautiously lowering her bulk into a chair. "Why, Jenny, if that isn't sweet of you to have waited tea for me! Clement, du thé avec du citron pour Mademoiselle et moi. Et des petits fours, n'est-ce pas?"

"Trčs bien, Madame la Marquise!"

In a lightning motion the maître d'hôtel bowed and in a flood of swift French dispatched half a dozen waiters flying to execute the order of this honoured guest.

"Well, well, my dear," remarked the Marquise, settling herself down comfortably in her gilt bergčre chair, "I love America and I'm surely proud to have been born an American. But there's no doubt about it—I'm nobody there and I'm somebody here. And that's a very gratifying feeling for an old woman as ugly as I am!"

Virginia laughed.

"I never saw anybody like you for inventing excuses for liking Paris," she said.

"And rightly, my dear. I've had a long experience of the world, and I'm quite clear in my own mind that France is the only country where people know how to live. Dearie me, how glad I shall be to get back to my own apartment! Isn't that Lord Dalburnham over there? Wiry, how wizened he's getting to look! And that hussy with him! He's old enough to be her grandfather! Bonjour, Duc!"

A grey-haired man with a red rosette in his button-hole bowed over her hand. The Marquise presented him to Jenny. The girl gave him her hand distractedly. She was wondering about Godfrey. The last train from London got in at nine something. Would he come by that?

"Why!"—Aunt Marcia's voice broke in upon her meditations—"if it isn't Clive Lome!"

The Marquise had put up her lorgnette to look at a blond young man who had stopped at their table, an attractive smile on his youthful face. He had a lissom, well-knit figure, and his morning coat was beautifully cut. The grey silk handkerchief which protruded from the outside pocket matched his carefully knotted tie with its pearl pin.

Aunt Marcia introduced him to Virginia. "His dear mother is one of my oldest friends," she explained.

The boy—he was obviously very young—looked his frank admiration of the girl's exquisite colouring as they shook hands. Her complexion was rose-leaf in texture and her shining hair, the colour of ripe com, admirably set off the perfect serenity of her expression.

"Sit down right there and tell me all about yourself, Clive Lome," commanded Aunt Marcia. "The last time ever I saw you was one fourth of June at Eton. My, if you haven't grown up since then! What are you doing in Paris?"

"I'm on my way back to Vienna," said the boy. "I've just had a fortnight's leave."

"Clive's in the Diplomatic," Aunt Marcia explained to Jenny.

At that the girl's interest quickened at once. He might know Godfrey. She resolved to watch for a favourable opportunity to ask him.

"And how's dear Lady Lome?" asked the Marquise.

"Top-hole, thanks awfully! She's in town for the winter. You ought to pop across and see her, Marquise. She'd be no end bucked if you would..

"Young man," said Aunt Marcia bluntly, "it will take me at least a month of chilly apartments and sulky servants to find out that, after Paris, I like London best. But I've been away for nearly eight months and, for the moment, wild horses wouldn't tear me away from Paris. How are all my London friends? What are Jock Corrington and his wife doing?"

"Oh, cat-and-dog, the usual married game!" remarked young Lorne.

The Marquise put up her lorgnette and scanned him severely.

"Anybody who takes as much trouble with his clothes as you do has no business to be a cynic," she said. "Come and dine with me at half-past seven and amuse Virginia," she added abruptly.

"I'd love to," said Clive eagerly, "if I can come in my travelling things. My train goes at ten-forty. I'm only stopping a day in Vienna to collect my traps as they're pushing me down to Budapest for a spell. They're short-handed at the Legation there..."

"We'll dine in the apartment," said Aunt Marcia. "Come how you like!"

They had a very well-chosen meal in the Louis Quinze sitting-room of Aunt Marcia's suite. Clive Lome was extraordinarily good company, and, like most English public school products, extremely self-possessed with quite definite opinions on everything. He seemed to know nearly everybody who was anybody in London. Between Aunt Marcia and him scarcely a character escaped unscathed. Aunt Marcia's idea of amusing Virginia was not altogether as altruistic as it had sounded.

But the girl was content to remain with her thoughts. She had left word at the desk that, if any one should ask for her, she was dining upstairs. Her eyes scarcely left the ornate clock on the mantelpiece. How slowly, it seemed to her, the hands crept round! Every time the door opened she looked to see the blue-and-silver uniform of a page. But each time it was the waiter serving them at dinner.

Nine o'clock came.... nine-fifteen.... nine-thirty. The London train must long since be in. But there was no sign of Godfrey. Now she suddenly remembered with a shock that Clive Lome would be leaving soon to catch his train. She must question him about Godfrey. She began to watch for her opportunity....

At last the moment came. It was Aunt Marcia who asked the question ultimately. They had been talking about people in the Foreign Office.

"Do you know Godfrey Cairsdale?" said the Marquise.

Hoping that neither would notice the flush that crept over her face, Virginia leaned forward to catch the young man's reply. But the Marquise had not finished.

"Such a charming Englishman," she said. "And so talented! They thought very highly of him at Washington, didn't they, Jenny?"

"Yes, I know old Godfrey," Clive replied. "We were at Eton together though, of course, he left long before I did."

"Have... have you seen him lately?" asked Virginia.

"Why, no!" answered the young man in a matter-of-fact way. "Nobody has!"

Virginia laughed nervously.

"What do you mean exactly?" she asked.

Clive Lome looked in surprise from the Marquise to the girl.

"But haven't you heard about old Godfrey?" he demanded.

Under the white damask of the cloth Virginia FitzGerald twisted her fingers nervously together. What was she going to hear? Her voice seemed to be far away as she said:

"You forget we've been on the water for the past six days, Mr. Lome!"

"Of course, of course," replied the boy. "Anyhow, they've kept it very dark.... for what reason none of us can make out!"

With maddening deliberation, as it seemed to the girl, he paused to light a fresh cigarette from the stump of the one he had been smoking. She was afraid to speak for the moment. She could not trust her voice. But Aunt Marcia plunged into the breach.

"Clive Lome," she said, "I hate riddles. What's happened to Godfrey Cairsdale?"

The young man dropped the end of his cigarette into his coffee cup.

"He's disappeared!" he said.

THE Orient Express went rushing through the night. Across the plains, in and out of the valleys, through slumbering towns and villages, it crashed and rattled and thundered, now awakening the echoes as it roared stupendously over iron bridge or culvert, now scaring up the wild game as it sped, a long arrow of yellow light, through the snow-clad forest.

Above the glare of the furnace a shower of sparks trailed out in a fiery wake as the great train, swaying rhythmically on its bogies, tore through the darkness. Comfortably warmed, brilliantly lighted, with its snug beds and soft linen, its well-kept table and choice wines, and its select company of prosperous travellers, it came speeding out of the wealthy West into the pinching poverty of Central Europe.

They had been late—two hours late—in leaving Vienna. The Austrian engine-driver, who had taken over from his German "colleague" at Salzburg, was doing his best to make up for lost time. It was a bitter night. On the heels of three days' snow a thaw had followed, and the air that struck into the engine-driver's cab from the snow-covered slopes fleeing away on either hand was raw and keen as a knife.

But within the train all was warm and cosy. People were settling down for the night. In most of the long sleeping Pullmans the peacock-blue blinds were now drawn. Here and there a porter in his list slippers passed noiselessly down the soft-carpeted corridor, his arms full of blankets and pillows, on his way to make up a bed. The train was very full.

Diplomats returning to their posts; politicians hurrying about the new Europe busy with the internecine squabbles of the little States; officers rejoining the Army of the Black Sea from leave; business men lured in mid-winter from the ease of London, Paris, or New York by the bait of Hungarian ore or Rumanian oil, or by the more shadowy promise of Turkish or Persian concessions; women who left a trace of perfume on the warmed air or showed the gleam of a white arm, the toss of an aigrette, through a compartment door; sallow-faced Greeks, an enigmatic Turk or two—the nationality and profession of this cosmopolitan band of travellers were as varied as the itinerary of the train on its four-day run from Paris to Bucharest.

Little by little, as the numbered kilometre stones beside the track slipped by, the lights were dimmed, sounds of life died away. Now and then, above the rhythmic thumping of the wheels, came a burst of voices, a sudden laugh, the popping of a cork.

Squatting on a battered leather suitcase on the floor of Compartment Nos. 5 and 6, Clive Lome contemplated with obvious satisfaction the glass of bubbling liquid in his hand.

"Here's how!" said he with reverence, raising his glass to his companion who sat on the lower berth facing him.

"Happy days!" came the time-honoured response and they drank in reverent silence.

When Clive placed his glass on the floor at his feet, it was empty. He wiped his lips with his handkerchief.

"By George!" he remarked with feeling, "I wanted that, Euan, old boy! That infernal mix-up at Vienna about my sleeping-berth almost finished me! I thought I was going to be left behind. If I hadn't happened to strike you, I believe I should have been!"

"I can always give a pal a doss down on this train," his friend returned. "Whenever I travel by it this double berth compartment is reserved for me. At Christmas and those sorts of times one wants the space. The bags are pretty heavy about then. I haven't got much of a load to-night. I'll clear some of these off and make room for you. Mind your head!"

With a sweep of the arm he raked from the berth on to the floor a great pile of white and green canvas bags, labelled and sealed up in scarlet wax. He was a small, dapper man with a brown, weather-beaten face, a very fearless, bright blue eye and a humorous mouth. He looked as hard as nails, and one might have well mistaken him for a cavalry officer. His clothes, like his personal luggage, were of good quality, but well-worn. The initials "E. McT," inscribed on his battered suitcases stood for Euan MacTavish, known in most of the capitals of Europe as King's Messenger and a great character. He spent three fourths of the year in trains and, as he used to say, his home was where he put his kit-bag down.

"Funny meeting you like this," remarked Clive, stretching out his long legs. "We were talking about you only the other night!"

"Who's we?" demanded MacTavish, lighting a cigarette.

"The Marquise de Kerouzan and I. You remember her. She's a dam' good sort. I was dining with her at the Ritz on Monday evening before I got on the train for Vienna. She had a devilish pretty niece with her, a Miss Virginia FitzGerald. Have you met her?"

"My dear old chap," observed MacTavish dryly, "in this infernal life of mine my female acquaintanceship seems to be restricted to ambassadresses, chambermaids, and occasional houris—mostly elderly and obese Germans—at night restaurants!" Clive Lome laughed.

"You're a caution, Euan," he retorted, "you and your houris! I bet you've got a wife in every capital on your round, you old devil! But this FitzGerald girl is an absolute topper, a lovely creature. By the way, Euan," he reflectively added, "you know everything—this girl was asking me about Godfrey Cairsdale. She seemed rather interested in him. What is at the back of his remarkable disappearance, do you know?"

From under his shaggy eyebrows the King's Messenger shot a sharp glance at the boy's disingenuous face.

"He's merely on leave, I understand!" he answered. But there was a tentative note in his voice.

"Rot!" responded Clive with vigour.

"Why so emphatic?"

"Because," Clive replied, "if he had gone on leave Godfrey would have had the common decency to write to Aunt Susan—Lady Preston, you know—and tell her he couldn't dine at her house on New Year's Eve. He left her with thirteen at table and a girl too many and the Lord knows what else. Aunt Susan was frightfully shirty. Besides, if he's on leave, the Office don't know anything about it!"

"Don't they, by Jove!" blandly remarked MacTavish. He picked up a heavy gun-metal hunting-flask which lay on the folding table.

"What about another spot before we turn in?"

The boy shook his head.

"We get to Buda at some unearthly hour," he said. "I shall never be able to get up in the morning if I start soaking whisky...."

With careful deliberation the King's Messenger measured himself out three fingers.

"Your first trip to Buda, Clive? Young Lome nodded.

"Cheery spot," commented MacTavish, reaching for a bottle of Teinacher water, of which, as an experienced traveller, he had laid in a stock at Stuttgart, "good horses and dam' fine women. Funny, how the two always go together! There's great shootin' in Hungary, too! Let's see! You're handy with a gun ain't you?"

"Not too bad," the boy admitted modestly.

"You toddle along to the National Casino; that's their swagger club—sort of Turf and White's rolled into one—and ask for Count Hector Aranyi. He's a thunderin' good chap, a great sportsman and rather a pal o' mine—or used to be, before the late unpleasantness. He's got some deuced good shootin'—his place is somewhere about where we shall be passing presently, between Buda and the new Czecho-Slovak frontier. He lives like a king—huge park, family retainers, regular palace! Mind you look him up. He'll do you A1!"

"I certainly will!" said Clive.

After a pause he added: "To get back to Godfrey Cairsdale, Euan: can you imagine why he should want to go off like this? Do you think he's got into a mess?"

"How do you mean?"

"Well, stumer cheques. Or a turn-up with a bookie. Or something like that!"

MacTavish put back his head and gave vent to a dry chuckle.

"That doesn't sound a bit like old Godfrey," he replied. "Look here, young Clive, you're just starting in diplomacy, ain't you? Well, here's a tip from an old 'un. It ain't mine; but it's a bit of sound advice that a wise old bird once gave my defunct Guv'nor. 'In diplomacy,' he said—he was an ambassador with over thirty years' service—'in diplomacy never ask a question unless you're sure there's goin' to be an answer!' And now I'm for peeps!"

And, as if to elucidate his nursery allegory, the King's Messenger proceeded to remove his coat.

Clive Lome seemed rather bowled over by this oracular enunciation. He remained silent for a spell. Then he said slowly:

"But, look here, Euan, I promised this Miss FitzGerald I'd make some enquiries about old Godfrey for her. What am I to tell her?"

"Oh, tell her he's gone fishin'!" retorted MacTavish, with his dry chuckle. He seemed rather pleased with his answer, for he repeated to himself, "gone fishin'," several times with evident appreciation.

Clive was about to reply when there came a discreet tapping at the door.

MacTavish swung round sharply. "Hullo, hullo, what's that?" he said.

He glanced at his wrist.

"Not time for the Customs yet..." he began, when Clive interrupted him.

"By George!" the boy exclaimed, smiting his brow, "I clean forgot! It's Vali!"

"Now isn't that jolly!" said Euan very sarcastically. "And who the devil's Vali?"

"She's just a girl I know. I met her in Venice last month. I ran into her again on the platform at Vienna to-night and asked her to look in on me for a drink before she went to bed. She's on her way to Hungary.... a jolly good sort; you'll like her!"

Before Euan MacTavish could frame the rather voluble comment which rose to his lips, the compartment door was noiselessly pulled back. Under the dimmed lamp in the swaying corridor a tall, slim girl stood. Her hair, like her eyes, was raven black and her small red mouth pouted deliciously. Her heavy fur coat, loosely slung about her, revealed a trim, well-shaped figure in a neat white blouse and travelling skirt of serge.

"Vali!" cried Clive joyously. Taking her two hands, he drew her into the compartment. He was about to close the door again when the girl, with an imperious gesture, stopped him.

"It is not—how do you say?—convenable to be shut in at one o'clock in the morning with two men. But I could not find you before, Mr. Clive. Now I stay only for two minutes—because I promised to come!"

Her English was fluent with the pretty little Viennese sing-song inflection.

"Euan," said Clive, "let me present Baronness Vali von Griesbach!"

With very charming dignity the girl stretched out her hand. The poised grace of all her actions was very marked.

"You are not angry I make you a little visit?" she said to MacTavish.

"I'm delighted to see you, Madame la Baronne," said Euan. "Will you have a drink? I'm afraid there's only whiskey!"

The girl rejected the offer, but asked for a cigarette, which MacTavish produced.

"You'll have to sit on my knee, Frau Baronin," cried Clive from his perch on the suitcase, "there's nowhere else!"

"I shall sit beside your friend!" the girl retorted sedately.

MacTavish slung a stack of red-sealed valises on the floor. To assist, the girl laid her hand on a worn brown leather pouch that lay on the bed resting against MacTavish's thigh.

"No," said the King's Messenger, gently but firmly, removing the small hand, "I'll keep that!"

The girl sat down on the bed. MacTavish quietly removed the pouch to his other side.

"That will give you more room!" he said. Vali, who had been peering about like a little bird among the various bags, clapped her hands and exclaimed:

"You are a Government Messenger, hem? like the Feldjäger who used to travel with dispatches for our King?"

"Something like that, Madame!" Euan answered.

She turned to Clive.

"You call me always 'Baronin," she said. "But he... he has eyes. He calls me 'Madame la Baronne.' MacTavish gave his dry laugh.

"I knew you were Hungarian by your colouring," he explained. "And when you spoke of 'our King'..."

"I am Hungarian!" proclaimed the girl proudly.

"Are you, by Jove!" observed Clive from the floor. "And I always took you for a Viennese!"

Vali's eyes flashed blankly at him.

"Ah, ça non!" she cried. "I am Magyar"—she struck her breast in a gesture of infinite majesty without, as it seemed to MacTavish, anything of the theatrical in it—"to the heart!"

As she lifted her white and rounded arm the wide sleeve of her blouse fell open displaying a long and puckered scar above the wrist. Shivering a little, as though the night air were beginning to strike chill, she gathered her fur coat about her shoulders and rose to her feet.

"I leave you now, my friends," she said. "Mr. Clive, when I come to Budapest..."

"But aren't you going there now?" the boy asked.

"No. I stay with friends, near Hacz. I leave the train soon—at Szob, at the frontier. B-r-r! What a night, hein? for a drive! When I come to Buda I send you a little word to the Legation!"

"Splendid!" vociferated Clive. "We'll go to dinner at the Hungaria and hear that gipsy fellow what's-his-name play!"

She gave her hand to MacTavish.

"Good-night!" she said, and let her burning black eyes rest for an instant on his rugged face. "Good-night.... and bon voyage!"

With a little laugh, an imperceptible shrug of the shoulders, she moved to the door. Her red lips, just parted, showed her white, even teeth. There was something of the sinuous vitality of a panther in her movements.

Clive went out with her into the corridor, now wrapped in silence.

"Do not disturb yourself, Mr. Clive," she bade him. "I am only a little way from you—see, it is here, the last compartment, at the end of the wagon!"

Nevertheless, he followed her along the rocking corridor as far as her door. There she turned and offered her hand. It was warm and soft, and, thrilling to her touch, passionately he sought to draw her to him. But she was too quick. With her free hand behind her she had pressed down the handle of the door and now, with a little laugh, she slipped inside, there was the snap of the lock and Clive was left with his face to the glass panel.

"Well, Til be damned!" ruefully remarked the young man. But he turned and slowly retraced his steps to his compartment.

"It's as cold as a money-lender's heart in here!" came a muffled voice from the top berth. "Shut that blinkin' door, Clive, for the love o' Mike!"

Euan MacTavish was already tight rolled in his blankets in the upper bunk.

Clive sat on the edge of his bed and began to unlace his shoes.

"What do you think of Vali, Euan?" he said.

"I'm just thinkin' about her, old boy. There's something about her that sort of lifts her above the common run of Hungarian women. All Hungarian women are chic and fesch and that kind o' thing. But, damme, this girl's got poise and-and dignity. Where did you say you met her?"

"In Venice... . when I was going home on leave the other day!"

"H'm. And what does she do?"

"Nothing. Just travels about."

"Any husband?"

"Not that I noticed."

"Funny," said MacTavish, yawning prodigiously, "I can't help thinkin' I've seen her before somewhere.... yes, put out the light when you like. I should turn it to 'dim'."

There was a click and the light went ut. In place of it a tiny blue bulb from the lamp in the roof threw an eerie glow over the two men in their bunks and the luggage and dispatch bags oscillating on the floor.

Rocking and swaying the Orient Express sped on through the night.

CLIVE awoke suddenly. He was dimly conscious of a feeling of considerable discomfort. Slowly he opened his eyes. They encountered only a black mass that seemed to press down upon him—the upper berth. All about him resounded the jarring, rattling, bumping of the train, to which accompaniment he had fallen asleep; but, as he listened, it seemed to him that its steady rhythm had, somehow, altered its beat. The thumping of the wheels was now more spaced out and a long, quivering, grinding sensation made itself felt and heard simultaneously. The train was slowing down.

How cold it was in the carriage! Shivering, Clive drew the bedclothes about him. He shrank before the icy breeze that played upon his face. By the eerie light of the blue glass bulb glimmering in the lamp in the carriage roof he could see his breath hang like smoke in the chilled atmosphere. With a shrugging movement of the shoulders he turned over in the narrow limits of his bunk. Damnation! How freezing the air was!

Presently an irregular banging sound forced itself upon his sleepy senses. For a little while he struggled, as one does when only half awake, against the inevitable. Then at last he sat up with a jerk, receiving that smart crack on the head which is the prerogative of the occupant of the lower berth. He swore blindly to himself as, one hand pressed against his aching brow, he forced himself to realize that the door was open and swinging free and that, till it was closed, there would be no further sleep for him that night.

He had lain down in vest, trousers, and socks. He put up an unwilling hand, found the button and switched on the lamp from dim to bright. Lazily he dropped his feet to the floor and had taken a pace towards the door when he stopped in surprise.

The top berth was empty.

The compartment looked just as Clive had left it when he had gone to bed. There were his clothes swaying gently to and fro on their hooks on the lavatory door, there in the racks was their luggage, and there—he duly noted—in the corner, Euan's red-sealed dispatch bags lay. Euan, the boy decided, must have waked, as he had done, chilled to the bone, and had gone off to row the contrôleur about the heating.

But now, with long-drawn-out tormented groans, as steam and compressed air hissed out of the brakes, with a grinding of wheels and rocking of bogies, the train had come to a halt. Clive stood still and listened. All manner of little subsidiary noises made themselves heard as though, like a runner that falls prone and panting at the goal, the Orient Express were relaxing itself in every limb after its long dash through the night. From the corridor a glacial draught struck into the compartment as though a window or door were open. Clive went outside and looked up and down. There was no sign of Euan and no human sound was audible. The young man returned to the compartment and shut the door.

He looked at his wrist watch. It was a quarter-past four. He sat down at the end of his bunk, raised the blind, and tried to peer out of the window. He wondered where they had arrived. But the pane was opaque with an intricate pattern of frost crystals. He tugged at the strap and let the window down.

He found himself looking out at close range upon the majestic winter landscape. There was nothing like a station visible anywhere. The train seemed to have stopped in the midst of a pine forest. Immediately in front of the window, illuminated by the light at his back, a low flat-faced stone was set up, bearing in white paint against a black background the numerals "224." Clive knew it to be one of the kilometre stones that mark the railway line from Vienna to Budapest.

All around them was the solemn silence of a winter's night. The trees, glittering from crest to base in their shining mantles of hoar frost, grew to within a few paces of the railway metals. Between the forest marge and the train there was a thick carpet of snow. Clive could see where the steam escaping from the pressure brakes had driven long black fingers into the white surface.

To his nostrils rose clearly the air of the forest, icy cold, impregnated faintly with odours of resin, of damp leaves, of moss, an eager and a nipping air that made him catch his breath. There was no moon. The shimmering white trees in the foreground and all the dark mass of woods behind seemed to stir restlessly beneath the softer breath of the thaw, their branches dripping with a tinkling sound or trembling gently beneath the weight of the frost.

Shivering in his thin silken undervest, Clive was about to shut the window when a noise farther down the train caught his ear. Some one was tugging at a glass. The young man thrust out his head. A dozen paces down the train, about where the end door of the Pullman would be, he dimly descried a figure standing in the snow between the forest and the train, a vague silhouette terminating in some kind of peaked headdress, probably a fur cap. At that moment, protestingly, the heavy train began to move forward once more. In the same instant Clive saw the figure beside the train shoot forth a hand, holding a letter or a paper towards the window opposite him. Almost simultaneously a dark object fell from the train at the stranger's feet.

Clive saw it bulk black against the snow as it rolled upon the ground, saw the figure stoop, then straighten up to face the train. As the train, gliding, with gathering speed, into its stride, brought Clive, peering from his compartment, level with the stranger, the beam of light from Clive's carriage fell, for an instant, on the face of the unknown.

To his unspeakable amazement Clive recognized Godfrey Cairsdale.

He had only had the briefest glimpse; but it was sufficient. He would know Godfrey Cairsdale anywhere. For that one fleeting instant he had seen him clearly, beyond possibility of mistake. He wore a high-peaked Russian cap of black fur, one of those short heavy pea-jackets, fur-lined and with a fur collar which men wear on winter shooting excursions in Austria and Russia, and top-boots. His face was rather drawn and set; but in his eyes there was that fearless, laughing light which gave his face one of its most distinctive features.

Clive Lome was no fool. He had gathered two things clearly enough from his brief conversation with Euan MacTavish about Godfrey Cairsdale: first, that MacTavish knew a great deal more than he was willing to admit about Cairsdale's disappearance; and, second, that MacTavish intended to keep his own counsel on the subject.

Who had received the letter which Cairsdale had handed up to the train? Obviously MacTavish, who was, probably, even now at the door at the end of the corridor. Who had dropped the package out to Cairsdale? Obviously again, MacTavish, who had brought it from London for him. But what, in the name of everything, was Godfrey Cairsdale doing in a Hungarian forest at dead of night in the depth of winter? How had he got there and where did he live?

Clive Lome shook his head dubiously. The whole thing was beyond him. What would that pretty Virginia FitzGerald say when she heard his story? From her conversation he had rather gathered that she was expecting to meet old Godfrey in Paris. Pretty poor taste on his part to prefer rampaging round Hungarian forests at midnight to entertaining a girl like Virginia FitzGerald at the Ritz!

The boy stretched himself languorously.

"Well," he said to himself, "old Euan can have his blooming secrets! They won't keep me out of bed for another minute!"

There came the quick patter of feet, the rustling of whispers from the corridor. Clive looked up. Just outside the door a voice said in low tones, but quite distinctly:

"Il y a un médecin, je crois, au numéro neuf. Faites vite, nom de Dieu!"

Clive stood up abruptly. A sudden premonition of evil overwhelmed him. Swiftly he plucked the door open. A conductor stood there with a lantern. The man's face was pale and distressed.

"What's the matter?" demanded Clive tensely.

"I look for a doctor, sir! A gentleman, he is taken ill!"

"Who is it? Who is it?"

"An Englishman, je crois.... je ne sais pas!"

Clive snatched his overcoat from its hook, and, scrambling into it, pushed past the man and strode rapidly along the corridor. Instinctively he went towards the end of the Pullman whence the package had been flung to Godfrey Cairsdale. A blast of cold air blew down the passage. The train was roaring through the night and Clive was flung from side to side as he groped his way forward. . And then he came to a dead stop. Two uniform attendants were bending down over something on the floor. Just beyond, the end door of the Pullman banged and crashed wildly. As Clive came up, the two men rose. Then he saw what their forms had concealed. At their feet, motionless on his face, lay Euan MacTavish.

VIRGINIA FITZGERALD had been a week in Paris when Clive Lome's letter to her from Budapest arrived. Aunt Marcia had moved into her apartment; but Virginia, rather to that lady's chagrin, had declined to leave the Ritz. She was not sorry to be rid for a while of the rather boisterous atmosphere of masseuses and milliners, coiffeurs and chiropodists, in which Madame de Kerouzan delighted to live. She excused herself, therefore, on the plea that she might very shortly be going over to London.

Such had been, in effect, her intention immediately after their dinner with Clive Lome. His disclosure about Godfrey had disquieted her, and the brief conversation she had managed to have with him in the hall of the hotel before he left to catch his train had only added to her bewilderment.

Godfrey Cairsdale, Lome said, had come over from Budapest about the beginning of December. After his arrival in London it had become known among the young men at the Foreign Office that he was not returning to his post in Hungary. Godfrey had called several times at the office; as far as Lome knew, he had last been seen there on December 31st.

On New Year's Day, the morning after Godfrey's unexplained absence had played such havoc with Lady Preston's dinner-party, Clive rang him up at his rooms. Mr. Cairsdale, the valet reported, had gone away on the previous afternoon without leaving any address. The man disclaimed all knowledge of Mr. Cairsdale's whereabouts. He had packed a suitcase for Mr. Cairsdale and put it on a taxi, and that was all he knew about it.

Rather mystified, Clive dropped in on Godfrey's elder brother, the Earl of Stratfield, at Buck's Club. But Jack Stratfield was equally vague as to his brother's movements. He and Godfrey had dined together at Ciro's a few nights before, and Godfrey, who was in perfectly good spirits, had said nothing about going away. On the contrary, he had appeared to believe he would be in London for some time.

Thoroughly puzzled now, Clive tried the Foreign Office. He drew blank again. Godfrey's immediate colleagues, like the people in the Central Europe department, which handles Hungarian affairs, knew nothing of his having left London. In any case he had notified no change of address, which he would certainly have done if he had left town.

"I was pretty well stumped by this," Lome had told her, "but, as an off chance, I thought I would put the question to Felix Denzill—he's a cousin of the Mater's, you know, and one of the Under-Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs, rather a big pot. I had intended to go and see him, anyway, to say good-bye before returning to Vienna, so I asked the office-keeper to take in my name.

"I was shown in at once. Old Felix had a visitor with him, a big, broad-shouldered fellow who looked rather like a naval officer in plain clothes. He didn't introduce me, and the stranger wandered over to the window and looked out into the Park while we talked. Felix asked about the family and so forth. When Aunt Susan's name cropped up, I told him how old Godfrey had let her down.

"I seemed to notice that he sat back a bit when I mentioned Godfrey's name. So I put my question to him point-blank:

"'What has become of Cairsdale, sir?' I asked him.

"Then I noticed that the big man in the window had pricked up his ears. Instead of answering my question, Felix Denzill sings out across the room to his pal:

'"What did I tell you?'

"Then, turning to me, Felix says:

"'If any one asks you, you can say he's on leave!'

"'Indefinite leave!' adds the big man in his gruff voice.

"'But look here,' I said, 'he's not on leave!' That riled the pair of 'em a bit, and they started sort of scrapping about it.

"'I told you it wouldn't wash,' says Felix. 'This place is a regular sounding-board. You've got to give some explanation. And stick to it!'

"'Perhaps you're right,' the big man agreed. 'Anyway, I leave it to you!'

"And with a nod to Felix and me he picked up his hat and walked out.

"'Cairsdale has had to leave London,' Felix said, when his visitor had gone, 'for—er, ahem—private reasons. And I suggest to you, Clive, that the less you discuss him with your friends the better it will be.'

"And not another blessed word," Clive wound up his story, "could I get out of him. On leaving his room, however, I asked the messenger who the fellow was who had been with Sir Felix. The man looked a bit uncomfortable and then said something about he' didn't rightly know.' He was lying, of course; but I wondered why he had been ordered to keep the identity of a visitor a secret..."

Virginia would have best liked to start for London on the spot to endeavour to tear aside herself tins web of mystery woven about Godfrey's disappearance. She could see, too, that Clive had a vague suspicion in his mind, though he was too well-bred to voice it to her, that some scrape lay at the root of Godfrey's surreptitious departure.

But, as the French say, night brings counsel, and on the following morning Virginia's practical good sense flatly rejected this plan of going to London to make investigations on her own account.

A stranger and a woman at that, she would, she knew, have no earthly chance against the conspiracy of official silence surrounding Godfrey's movements. At any rate for the present, she must contain her soul in patience and wait. In Clive Lome she had at least secured an ally, and at Budapest, which had been Godfrey's last post, information might be forthcoming to account for his inexplicable failure to keep his appointment with her.

Now, as she sat in the lounge at the Ritz and read Clive's letter, she felt glad that she had waited. For the letter with its extraordinary account of Clive's recognition of Godfrey Cairsdale on the railway at Kilometre 224 gave her her cue for action, that action for which her soul pined.

"There's only one thing more," Clive wrote in conclusion in his boyish, unformed hand, "and that is to ask you to keep this to yourself. Strictly speaking, I have no business to write to you anything about it. But I promised to let you know if I had any news of old Godfrey. The whole thing has been hushed up in the most extraordinary fashion. They have managed to keep it out of the newspapers, too. MacTavish, whom I went to see in hospital here, declares I dreamt the whole thing about seeing Godfrey. He says he only went to the door of the train to get a mouthful of air and was suddenly struck down from behind.

"He thinks it was one of these train robbers one reads about. The fellow, he says, must have been interrupted by the arrival of the guard, for, MacT. says, nothing of his was taken. He lost a lot of blood, but really had a miraculous escape, for the point of the knife was turned by the metal work of his braces and the wound is not serious. I was sent for by the chargé d'affaires—the Minister is not here—and threatened with the most frightful penalties if I breathed a word to a soul. So I hope you won't give me away. Let me know if there's anything more I can do...."

It was curious, but her sensation on reading Clive's letter was one of relief. Only now did she realize how Godfrey's inexplicable silence had preyed upon her mind. But here, at least, she was faced with a concrete situation. For, though Clive scrupulously refrained from drawing any conclusions from the curious story he had set forth, the hand of the British Secret Service was plainly evident to her in the mission which had carried Godfrey away from the haunts of civilization. But then Lome was hardly more than a boy. He had grown to manhood in post-Armistice days. She could understand that to him and all his generation Secret Service was no longer a tangible reality, but merely a romantic legend of those four historic years.

She herself, she realized, though in the four years that had elapsed since her twenty-first birthday sue had been immersed in foreign politics, felt strangely out of her depth in the murky waters which Clive's story disclosed. Two years of the staid respectability of Washington, of America's smoothly running civilization and unemotional politics, had dimmed her vision of Europe. She had forgotten, she told herself, the perpetual surge of warring nationalities within the narrow confines of the European continent. It came almost as a shock to her to be reminded that if war had been banished from the face of the earth, it was only to smoulder the more fiercely in the hearts of the peoples.

A little furrow of perplexity appeared in her smooth white forehead. Godfrey was on a dangerous mission. That much was clear to her. She made no doubt that the object of the attack on MacTavish had been to obtain possession of the letter which Clive had seen Godfrey hand up to the train. In all the circumstances of the case, she decided, there could be no other plausible motive for this swift, murderous assault. And the importance of this document, whatever it might be, was shown in the circumstance that it had all but cost the King's Messenger his life.

But why had MacTavish and not Godfrey been attacked? Obviously because they suspected, but could not definitely locate, Godfrey's presence. She put it to herself in this way. The enemy organization had discovered that a secret agent was sending out reports from some point on the itinerary of the Orient Express. In such a case it would clearly be simpler to concentrate the investigation on the train rather than on the extensive area it traversed. In other words, the recipient must first be discovered before the sender could be identified. And in due course the investigation had been narrowed down to MacTavish who had been shadowed throughout the journey.

Had MacTavish been robbed of the report? With a little pang she realized that the point was immaterial. If her reasoning were correct, the enemy organization was more concerned to identify the agent than to intercept one specific report. And the incident at Kilometre 224 had told them what they wanted to know. It had definitely located the activity of a British secret agent in this particular neighbourhood. Godfrey was then in imminent peril...

She looked again at the date of Clive's letter. He had written on the morning of his arrival in Budapest—January 8th—and forwarded the letter by the diplomatic valise to Paris. And this was the 13th. For five days, then, the secret of Godfrey's identity had almost certainly been known to the enemy, a secret which his own Government had been at such extraordinary pains to maintain inviolate.

Virginia rose quickly to her feet, slim, straight-limbed, and lissom in her plain, fawn tailor-made. She must act and act at once. But how? She realized very clearly that she stood on the threshold of a secret shared by only a very few; that if she sought to penetrate farther, she would probably do so at her own peril. On the other hand, she might let things rest where they were and wait for Godfrey to come to her.

But a phrase in Clive's letter haunted her: "Poor old Godfrey looked a bit under the weather, sort of haggard and hunted, don't you know?" he had written in his loose, graphic way. She had a vivid mental picture of Godfrey turning away from the lighted train to the snowy stillness of the forest. To face what?

No! She could not remain inactive while he was in danger. He might resent her action, but she would risk that. And at the unromantic hour of ten on a sunny winter's morning, in the prosaic surroundings of a modern hotel lounge, revelation came to Virginia FitzGerald. She knew that she loved her Englishman, and that the unseen force which was driving her to follow him into danger sprang from her instinct to share his life.

"This," she said to herself, and crossed briskly to the reception desk, "is where Virginia comes into the war!"

Within three minutes Virginia had the hotel staff moving. There were endless difficulties in the way of obtaining the requisite passport visas for a journey to Budapest; she required that her passport should be in order by 4 p.m. that day. The Orient Express, which runs only tri-weekly, had been booked up for weeks in advance; she announced her intention of boarding the train at the Gare de l'Est at seven-forty-five that evening. And because her mind was made up and because she was a woman, and a very attractive one at that, the French genius for improvisation asserted itself, the impossible was accomplished, and shortly before eight o'clock that evening she sat and watched the spluttering arc-lamps of the Gare de l'Est slide by as the great train thumped over the viaducts above the busy Paris streets.

She had wired to Clive to meet her at Budapest. She had feared to face Aunt Marcia, so had posted her a letter before starting, telling the Marquise that she was going to Hungary "for a change" and asking her to forward letters to her at the American Legation. She had long since established complete independence of movement vis-a-vis Aunt Marcia; but she did not wish to stand cross-examination as to the motives for her sudden decision.

For half an hour that afternoon, at the Wagons-Lits offices on the Boulevard des Italiens, her golden head might have been seen in close proximity with the dark poll of an attentive clerk as they pored over the railway maps of Europe. She had learnt little or nothing about Kilometre 224 save that it lay in the forest between Szob, the frontier station, and Hacz, and that the train made a momentary halt there to allow a local express to pass at a crossing ahead. It was easy to identify the spot, she was told; it was the first stop after the train left the frontier station.

With eager anticipation she awaited the coming of the second night after their departure from Paris. She told herself she would hope for nothing lest she might be disappointed. In the restaurant car she carefully scrutinized the faces of her fellow-travellers to see if she might identify anybody who might possibly be a King's Messenger. Only one man, she decided, might answer to the description; but her hopes were dashed when she heard him describing to a companion a business trip he had paid to some glass-works in Belgium.

Szob, with its naked platforms and hissing arcs, found her nervously impatient at the long halt for customs formalities. When at length the train pulled out into the darkness, she posted herself at the end door of the Pullman, on the right hand of the train from which side Clive Lome had seen Godfrey. Even before the train had begun to slow down, she had lowered the window, peering forth over the whitened countryside.

The moon shone coldly out of a clear sky. As the train drew up, the belt of forest in which it halted lay spread out before her almost as bright as day. No human figure was discernible in the narrow corridor that lay between the train and the trees. She looked to right and left. If any messenger were waiting for Godfrey, he gave no sign. She seemed to be alone in her watch.

She strained her ears, her eyes, for a sound, for a movement. But nothing broke the peace of the night; and the vista of snow gleaming white between the dark tree-trunks remained undisturbed. Then, from the wheels beneath where she stood, a brake sighed with a rush of steam; the noise was repeated the length of the train; there was a little quivering movement along the corridor and she knew her journey was being resumed. Slowly she regained her compartment.

GODFREY CAIRSDALE stepped briskly out of the shadow of the living-room into the dazzling sunshine of the veranda. In the early morning hours a sharp frost had succeeded to the thaw of the previous days, and all around him the forest, gleaming white beneath a deep blue sky, sparkled in the noonday sun.

The air was exhilarating. He inhaled deeply, standing with arms outstretched at the veranda rail, looking out along the glittering vista of forest track that ran from his front door away to the serried ranks of pines marking the horizon. After the strain and fatigue of the night, the eager breath of morning had a tonic effect on his nerves.

It had been close on five o'clock, in the icy, impenetrable blackness of the winter morning, that, over the crackling ruts of the forest ride, he had painfully made his way back from Kilometre 224 to the villa. Thank the Lord, for nine days he would have respite from these cross-country journeys to the railway. It was Thursday morning. Not for more than a week would he have to fare forth again to the forest clearing to await the passing of the Orient Express.

He was in holiday mood on this invigorating morning. He felt and looked in the very pink of condition. For a week he had lived in the heart of the forest, out of doors all day, either working at the Roman remains with Dr. Nagy, the archaeologist from Hacz, the neighbouring town, or taking long tramps through the forest between the villa and Schloss Kés, or, with axe and billhook, helping Milos, his Hungarian servant, to fell and split the wood for the fire.

His eyes and skin were clear, and under his khaki shirt, collarless and open at the neck, his muscles were hard and firm. Not even the gnawing anxiety winch had been his inseparable companion since that memorable interview in London on New Year's Eve could interfere with his growing sense of intense physical fitness. He seemed to have sloughed away, as a snake discards its skin, the grossness of city life, the stuffy atmosphere of the Foreign Office, the club; his nerves had grown steadier as he found when at dusk he prowled silently about the park of Schloss Kés, studying the ground, planning for the ordeal that stood before or stole away after nightfall to his secret rendezvous with Max Rubis.

At the door behind him a wheezy voice croaked in Hungarian:

"His Honour's breakfast is served!"

Cairsdale turned to reenter the house. Old Milos, with his wizened face and grizzled head, wearing the frogged jacket and top-boots of the Hungarian peasant, smiled a toothless "Good-morning" as the young man stepped from the veranda into the living-room. It was a long, rather dark apartment, the walls roughly wattled over the heavy logs of which the two-room villa was built. Its furnishings were of the most exiguous.

There were no pictures. A few antlers, roughly mounted, each inscribed with a date, a huge boar's head affixed to an oak board, and a stuffed fox, in a glass case hung above the fireplace, were the only decorations. The furniture, cheap white wood stuff from Vienna, and a few basket chairs, was scanty. Skins of a bear, of wolves and foxes were laid here and there about the rough deal floor. The bedroom, to which a curtained door gave access, contained nothing but a bed, a chair and a table. Though in the neighbourhood the shack was known as "the villa," it was more like a small shooting-box, a mere shelter which at most could provide a rough shake-down for a few guns wishing to make an early start after game.

In the open hearth of the living-room a great fire of logs hissed and spluttered. There was an agreeable odour of burning resin. Before the fire on a small round table spread with a red-and-white cloth, breakfast was laid—eggs, white bread and butter, coffee, marmalade. On a corner of the table stood the battered brown leather pouch which, but a few hours since, had dropped at Godfrey Cairsdale's feet from the Orient Express.

Godfrey picked up the wallet and unceremoniously emptied its contents on the floor.

"So, Milós," he said to the old man, "your stores for the week!"—he stopped and began handing up a number of packages—"coffee, tea, sugar, biscuits, bacon, marmalade. Cigars!—those are for me, And here! Some tobacco for you!"

Mumbling his thanks, his arms laden, the old man retired with the supplies while Godfrey sat down to breakfast. There was a bundle of newspapers in the pouch and he glanced through them in leisurely fashion as he made his meal. When he had finished, he took from the table a tin of tobacco and, having filled his pipe, proceeded to light it with a pine splinter from the fire. Then, with his long legs stretched out to the blaze, he sat and smoked awhile in reflective silence.

Presently he rose, and from the inner pocket of his short fur coat, which hung over the back of a chair, he drew a thin slip of paper. With clouded face, for the twentieth time since at dawn he had first unearthed it from its hiding-place in the tin of John Cotton at his elbow, he read the message, the message which the Orient Express had brought.

"Two clubs, no change," it ran; "stand by for seventeenth as usual."

This much was typewritten. Cryptic enough to the uninitiated, it did not apparently mystify Cairsdale. It was to an addition written in by hand at the foot of the message that he devoted his attention.

"V.F. at Ritz Jan. 5," it said. That was all.

But it was enough for the lover. It was the first tidings Godfrey had had of Virginia FitzGerald since her cable of December 30th, announcing her departure next day for Europe, had sent him into a paroxysm of joy. He puffed at his pipe and scrutinized the paper. The writing was unfamiliar. To what kindly hand did he owe those few scrawled words? That there was some one who would do as much for Jenny! To think that not even yet did she know why he had failed to keep their solemn tryst in Paris on January 5th!

He turned his thoughts back to that extraordinary interview at the Foreign Office to which a telephone message had unexpectedly summoned him on New Year's Eve. He would never forget it. By shutting his eyes he could visualize so clearly every detail of the Under-Secretary's room, the great mahogany desk with its pile of crimson dispatch-boxes, the tall windows overlooking the foggy Park, the array of reference books on the mantelpiece above the blazing fire.

Sir Felix Denzill had a visitor, a burly, cleanshaven man with an odd suggestion of the sea about him, whose keen eyes, firm mouth, and incisive way of talking proclaimed the habit of command.

"This is Cairsdale," was the rather informal introduction of Sir Felix who, usually the pattern of convention, omitted to name his big man, nodding, gave Godfrey his speak.

The question was rapped out like a burst from a machine-gun.

"Yes," said Godfrey.

"You are interested in archaeology?"

"Yes."

"Would you be inclined to undertake a Secret Service mission?"

"Yes," replied Godfrey, without hesitation.

The big man turned to Sir Felix.

"He'll do!" was his comment.

He pulled out a long silver cigarette-case.

"Mind if we smoke?" he asked Sir Felix. He passed his case to the two men.

"There's somethin' brewin' in Hungary," he began, settling himself back in his chair. "Just what it is we don't know—yet. It's a movement working up to some kind of a military outbreak so much seems to be clear; and when it comes, it'll be a big 'un. The fact that the notorious Colonel Trommel is mixed up in it is sufficient guarantee of that.

"A castle in Hungary—Kés, it's called; it belongs to a Count Gellert, near Hacz, on the main line from Vienna to Budapest, not far from the Czecho-Slovak frontier, seems to be the head-quarters of the movement. At least all the threads back there. There are three heads, symbolized by the three of clubs...."

"The three of clubs?" echoed Godfrey.

"The three of clubs no less," rejoined the big man. "It is by means of this card, apparently, that the warning orders are sent out to the different groups of the organization. Five days ago our agents in Berlin, Brussels, Berne, Monte Carlo, Milan "—he ticked the names off on his fingers—"and one or two less important places which, for the moment, I don't remember, began reporting that men known to be prominently involved in this plot had suddenly departed for such storm-centres of militarism as Munich, Stuttgart, and Budapest. And in four cases they are known to have had warning by means of a three of clubs surreptitiously passed to them..."

"But surely," Godfrey observed, "if these men are known to you, you could easily have them laid by the heels...."

"The same idea roughly," rejoined the big man blandly, "occurred simultaneously to every one of my agents. But it won't do, young fellow. It's too soon to move. We aren't in deep enough yet. If we ran the net out now, we should fish up only the small fry—the big chaps farther out would get away. I'm after the heads! And you've got to fix 'em for me!"

Godfrey raised his eyebrows. This very positive person was, he thought, assuming a great deal.

"Who are the heads?" he asked. The big man chuckled.