RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

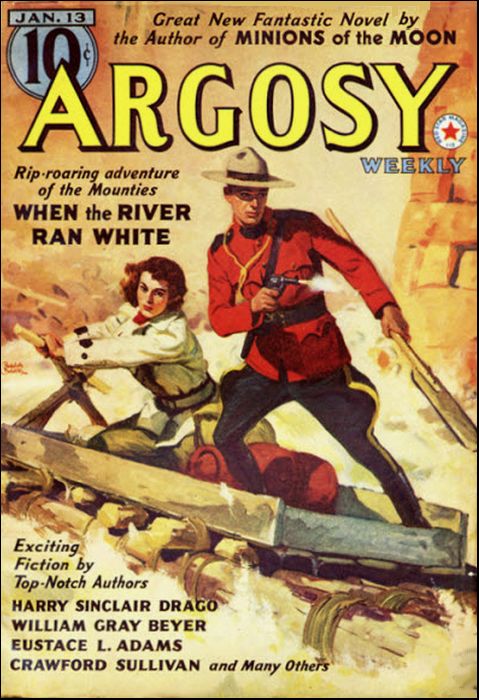

Argosy, 13 Jan 1940 with first part of "Minions of Mars"

Rip Van Winkle was a mere cat-napper compared to Mark Nevin who went to sleep in 1939 and woke up six thousand years later. That was confusing enough without being elected by a prankish, disembodied intelligence to be the father of the future race, and chosen by a smooth-tongued rebel as king of a crazy country Mark had never even heard of. A sparkling and fast-moving tale of adventures in the Days to Come...

MARK NEVIN, away back in the twentieth century A.D., had a stomach ache. Then his doctor diagnosed his ailment as appendicitis and persuaded Mark to be the first to try his new anaesthetic. Something slipped, and Mark slept peacefully on in a blissful state of suspended animation.

While Mark was napping, a cataclysmic war broke out that shattered civilization.

Things were a little better when Mark finally did come to, but he might have fared badly just the same but for the intervention of one Omega, a disembodied intelligence.

He selects Mark to be the father of the neo-man and chooses the lovely Nona as his mate, which is agreeable as Mark has already fallen in love with her. He imparts a radioactive element to their blood.

With Mark as leader, Omega enlists an army of Vikings to wipe out two malignant intelligences which threaten to destroy the world. Victorious, the Vikings, Mark and Nona take their leave of Omega and sail for home.

A LONE figure stood atop the little knoll and gazed in perplexity at the distant city. Eyes shaded from the glaring light of the rising sun he seemed to be seeing a sight beyond understanding. He turned back and as he did so, the golden light of the sun caught the play of powerful muscles under his bronzed skin. Brief leather trunks, as pliable and almost as close-fitting as his own skin, were held by a broad belt from which hung a shiny hand-axe. He wore no other clothing except a helmet, adorned with wings and considerably battered.

His face was as strong as his smoothly muscled body. The clear, blue eyes were baffled, haunted by a persistently elusive memory. He seemed to have forgotten everything he ever knew. It had taken him, for instance, more than a day to remember his own name. It had only come to him a few hours ago. Mark Nevin. And now, as his hand brushed the axe in turning, he caught the fleeting recollection that he had been known as Mark the Axe-thrower. The axe-thrower—idiotic! But of course there was the axe—but whom did he throw it at—and why?

Experimentally, he drew the axe and let fly at, a sapling fifty yards away. It was a tremendous throw, but he didn't know that. Nor was he much surprised when the axe sped true and sheared through the four-inch tree. His only emotion, as he retrieved the weapon, was a certain satisfaction that he had earned his name. Mark, the Axe-thrower, it was. Whatever that meant.

Briefly he inspected the axe before returning it to his belt. There was something he should remember about it; something he couldn't quite grasp. The weapon was a solid piece of metal. Its entire surface was gleaming with a tarnish-proof luster. Stainless steel, he would have called it if he could have remembered the term. But he couldn't.

There was some association here, but no amount of concentration would bring it to the fore. Only the dim thought struggled to the surface, that here was a thing of great antiquity. And he wondered how he knew that. For the axe was as shiny as one made and polished an hour ago. One thing he did know, and that was that he must not distrust these vague recollections of his. There was a lot to remember, and he had the uncomfortable feeling that someone, somewhere, depended on him to remember.

HE could see that someone and he knew her name. She had been with him since his first conscious memory yesterday morning. The vision of her loveliness had been with him in the salty water as he swam toward the land he was now exploring. Even then he had known her name—Nona.

But no amount of thinking had brought the slightest added knowledge. It was very irritating to recall her so perfectly, and not actually to know the slightest thing about her.

Discontentedly, he turned and faced the distant city. There he would find human beings. And it was most likely that among humans he would find the thought associations that would stir his tantalizing memory.

There were no workers in the tilled fields about the city. Nor any movement in the harbor on his left. The sun made long shadows of the masts of these vessels, and the rippling of the waves turned the shadows into writhing snakes. But there was no other motion.

There was an explanation for this gloomy quiet, and a simple one at that. It was still early, and the inhabitants of the city were simply still in bed. But even if this simple fact had been explained to him, he would have found it strange. For Mark was not the same as other men in this respect. He didn't waste the sun-less hours of the night in stupor. He was as active then as he was in the daytime.

Mark was not even aware that normal men needed sleep and food. For in the short day and night of his conscious existence he had done none of these things, and had felt no loss. He was a self-sufficient machine, and he felt marvelously fit and vigorous as he strode rapidly toward the city.

Mark, with the childlike trust of the innocent or the not-quite-bright, made no attempt to be stealthy.

He was walking beside a broad, cobbled path. This was an ox-cart road, he recognized, and then wondered how he knew. There were no ox-carts to be seen. And certainly in the day and night of his memory he had seen no such conveyances, nor the roads on which they traveled.

Somewhere beyond that day and night such things must have been familiar.

The sight of the cobbles seemed to touch some familiar chord, and experimentally he stepped on them. They were uncomfortable to his bare feet, and he moved back to the smooth dirt by the side of the road. Then the struggling memory came to the surface.

It was the smooth feel of the caked dirt which carried the association. For an instant he seemed to see a road stretching endlessly into the distance. Rushing along its hard, smooth surface were wheeled vehicles, traveling at breakneck speed.

The vision passed, and with its passing came the realization that the road he had seen and the automobiles moving on it, were things of antiquity equal to that of his axe. Such things no longer existed, he was acutely aware. And yet he felt that even with the knowledge that thousands of years had gone since their existence, nevertheless he had seen such roads and traveled in such cars. This was getting more unnerving at every second, and he decided that unless he could remember everything at once, it would be more comfortable not to remember anything at all.

The cobbled road led directly between two buildings at the edge of the city. It continued as a street, narrow and shadowy. Mark walked on, intent on finding men. And men he found, though not quite in the way he had expected. He had gone perhaps a half-mile, when abruptly a horde of yelling maniacs catapulted from an alley and bore him to the ground!

THERE had been no warning, and the thing was so sudden that he hadn't had time even to let out a yip of protest. Then he was lying wonderingly beneath a ton or so of evil smelling humanity and waiting patiently for further developments. He felt no more resentment, than he had felt pain from the beating he had taken.

His assailants were more surprised than he. Surely, thought they, a man of such tremendous physique would require mighty strenuous subduing. Disappointed and a little relieved, too, they lifted themselves off their prisoner's body. Two of them eased their feelings by cuffing him as they rose. The blows, while vigorous, caused only a momentary twinge and Mark blissfully ignored them. He was busy watching the astonished expressions on their faces, as he sprang, unmarked and, unhurt, to his feet.

This was not a new experience, he realized, noticing that several of his attackers were holding short clubs in their hands. Sometime in the past men had attacked him with weapons and had been surprised that he had emerged unscathed. For the first time he sensed the fact that he was in some manner different from other men. That for some unaccountable reason he was hardier and less easily damaged. This, he decided, was probably a good thing.

"Hooray?" suddenly demanded the foremost of his captors. "Mac or Mic?"

Mark frowned momentarily. Then he grinned. For into his continually astonishing brain had popped the knowledge that a Mac was a Scotchman and a Mic, an Irishman.

"Yank," he answered, and then wondered why he said it. In his head came the sound of a baseball popping off a bat, although Mark didn't realize what it was.

"No such!" declared the other. "Soo!"

Whereupon his attackers closed in fore and aft, and marched him down the street, clubs held menacingly. Mark was still grinning as he walked between them. He wanted to go into the city anyway.

His eyes fell on the leader of the crowd and he was surprised to note that the beefy one was carrying his axe. He hadn't known he had lost it, but realized that it had probably been wrenched from his belt during the short scuffle. Somehow the axe didn't seem a dangerous weapon in the leader's possession. He wondered if he was also immune from damage by axe-cuts. It annoyed him that he couldn't remember why he was different from normal humans.

Right now he resolved not to let the axe get out of his sight. He knew that somehow it was connected with the past, and that he mustn't lose it.

Here and there as they marched, a sleepy-looking head would poke out of a window to see what the night-watch had caught. Mark grinned at them, one and all, and usually got a startled look in reply. His captors were very military in their manner, assiduously keeping in step. They were burly and dressed in ill-fitting uniforms of coarse cloth, and armed with daggers which were fastened in their belts, in addition to the short clubs.

Mark with his vast splotches of ignorance, could not, of course, know that it was not exactly military in the most rigorous tradition for the guards to chatter like monkeys as they marched. Some of the words and expressions they used were unfamiliar ones, but most of their conversation Mark was able to translate into intelligible meaning. This puzzled him for a while, but as their words became more understandable he forgot about it. They were talking English, he knew, and the reason it sounded strange was probably that they spoke a dialect he had never heard. It didn't occur to him that he was listening to English as it was spoken several thousand years after he had learned the language as a boy.

The conversation centered about him. Guesses were being made as to what manner of man he might be; and why he hadn't suffered from the cudgel blows they had administered; and finally as to what disposition might be made of him by the local magistrate. Quite a few guesses were made concerning the last, and they varied all the way from slavery in the fields to burning at the stake. One fellow, on Mark's left, voiced the opinion that the proper punishment for his crime of breaking curfew, should be a term in the king's army.

"That's no punishment!" exclaimed the man next to him, although he didn't say it in quite that way. "The army lives high."

"I know it," replied the other, complacently. "But when I tell the magistrate what I saw, that's what he'll say, too."

"What did you see?"

The first man carefully drew forth his knife. Mark noticed that it was stained with a bluish streak along its cutting edge. The stain seemed to sparkle with an iridescent sheen. The second guardsman looked at it stupidly.

"That's where I sliced him on the shoulder," explained the first man. "Look at the shoulder. The left one."

MORE curious than they, Mark twisted his head to look at it too. There was a smear of the same bluish substance, but no cut. It had healed in such a short time that only a teaspoonful of blood had been spilled. One of the watchmen was also looking at the smear spot, his face portraying a certain amount of awe intermingled with profound respect.

"It's only a scratch," he murmured. "What bothers me is that blue stuff. You don't suppose he bleeds blue, do you?"

"It was no scratch," his friend insisted. "You know I always take a good slash when the sergeant isn't looking. Now wouldn't this lad make a soldier?"

The other shrugged. "Blue," he muttered, unhappily. "Gorm."

Mark's brow was creased in a deep frown. Dimly he was grasping another section of his vanished past. Blood, he knew, should be red, not an iridescent blue. And this blood of his, which refused to follow the rules, had something to do with his differing from normal mortals. Was he really the freak these idiots seemed to think him?

He hardly noticed when they turned into a large courtyard, and stopped before a huge door of oak, studded and banded with iron. The sergeant hammered on it with his club, while the rest of them relaxed as if they expected a long wait.

Mark's mind was going like blazes. Because he was remembering. Remembering a period of intense pain. He was remembering also the serious face of old Doc Kelso, who wanted his permission to use his new anaesthetic in the performance of the appendectomy he must undergo. It was all coming back...

Abruptly he was snapped to the present. A club-blow between the shoulder blades almost knocked him down. He caught himself, however, and spun round in fury. Blast them, just as it was all coming back, too. He stopped short at the sight of a dozen drawn daggers. Perhaps it wouldn't be smart to test the peculiar power of his blood against so many of those knives. After all, why become hash merely because of overconfidence? And in that moment of hesitation he was forced through the now open portal.

Mark caught a fleeting glimpse of a small room with a table at which were seated three soldiers playing cards. A fourth was swinging open another massive door of oak. Mark was given a shove through this one also. A short, dark corridor led them past a series of barred doors, from behind which Mark heard a variety of snores, all in different keys. Before he had a chance to wonder where he was being led, he found himself thrust forcibly into an unoccupied cell.

The door clanged shut and the sound of retreating footsteps mingled with the nasal serenade.

IN the course of the world's history there have been many methods of propulsion through water. Fish have used fins and tails almost since time began. Squid-like creatures utilize rocket propulsion, by swelling a muscle-lined bladder with water and then squeezing it out again. Man's earliest attempts involved the use of both hands and feet in swimming. A more advanced effort consisted of lying prone on a short log and paddling with the hands. Then some inspired genius hit upon the idea of hollowing out the log and paddling with shaped paddles.

From this crude beginning the evolution of boats probably has paralleled very closely the cultural advance of the race. For with the improvement in boats came an interchange of ideas between groups far removed from each other. Thus it was that when man had attained his highest cultural status during the waning years of the twentieth century, travel over and through water had also reached its peak of efficiency.

But when the peoples of the world decided to war upon one another, as these boats were the ultimate in transportation, so was this war the ultimate in destruction. Thus it was that with the end of the war man found himself cast back almost to the point when he was propelling a dugout with a paddle.

That was the last war for many a year; it was so completely destructive, so devastating, that when it had at last burnt itself out, man had sunk to such low estate that he could think of nothing to fight about except the immediate necessities of life.

But ships, ever the measuring-rod of man's progress, had again started their slow evolution toward the ultimate perfection they must some day regain. And the culture of man was keeping step.

The first morning rays of a golden sun caught the upper portion of a huge, sagging square-sail, and touched it with fire. A man from the tenth century would have found the ship to have some familiar characteristics, but only a person living in the eightieth century would have recognized it for what it was. A vessel of the north-country sea-rovers—peopled by yellow-haired giants who would rather do battle than eat—and who had prodigious appetites.

The ship was becalmed, and this was a vessel which need never be becalmed. Its sides were lined with a single row of long oars, now cocked at an angle, so that the blades were well out of the water. The rigging of the sail, which was far more scientific and manageable than any used by tenth-century Vikings, allowed it to make use of the slightest current of air, and in any direction except straight ahead.

APATHY reigned among the voyagers on this ship. No definite course of action had been decided upon. A difference of opinion existed concerning whether they should return to their home port or continue the fruitless search that had occupied them for the past day and night. There was the urge to keep searching but in each was the knowledge that it was futile. For no man could swim in the open sea for a day and a night.

Leaning against a short section of rail, and gazing with tragic eyes out over the waves, stood a young woman, beautiful even in her grief. The yellow-haired Norsemen, sprawled wearily about on the deck, glanced occasionally at her, and then quickly looked elsewhere. It was her man who had been lost, but they were able to feel her grief almost as acutely as she. For the lost man was Mark, the Axe-thrower, favored of Thor, and the personal hero of every man on board.

Nona's lovely body reflected the weariness she endured as she left the rail and made for her cabin. But hers was only a fatigue of mind, manifesting itself in a body that was really tireless. Her blood was charged with the same cell-renewing element that made Mark the perfect physical machine that he was. But so grueling had been the waiting and hoping that she imagined fatigue where no fatigue could be. Wearily she slumped into a soft chair. Hope had fled, and there remained only a numbing, tearless grief.

Then abruptly she sprang to her feet, one hand stifling an involuntary scream. Across the room, squatting in a corner, was a creature that would have raised terror in the stoutest of humans.

Superficially the thing was an enormous spider, fully two feet across the body. Superficially, insofar as it possessed eight legs attached to its bulbous cephalothorax. But different, in that it had six tentacles, three on a side, on its upper surface.

Each of these members was about three feet long and was divided at the end into two flexible prehensile fingers. And different also, by reason of the segmented, chitinous armor which covered the body. But, spider or no spider, the thing was a witch's fancy, the hideous product of a creator gone mad. Nona thought perhaps she ought to scream anyway. So she did.

"Calm yourself, girl," came a voice from the general direction of the creature. "It's only me... Omega. I just wanted to see how a human would react to the sight of one of the former inhabitants of the moon. This was my original body, you know. I assume you're not exactly in favor of it?"

Nona slumped again into the chair. "Oh, it's you," she said irritably. "Don't you know this isn't any time for your silly tricks?" She winced at the sight of him.

"And whatever that thing is you're wearing, please destroy it."

"It was destroyed more than five hundred centuries ago," said the voice. "You know that. You might call this thing an astral projection—it's been dead so long. But really it's only a figment of your imagination."

"It's certainly no figment of my imagination, you celestial prankster. No self-respecting girl would ever work up a thing like that."

"You certainly did imagine it," Omega snapped pettishly. "I made you. And I'm not very pleased at the way you react to my natural body. I considered it quite handsome at one time. But then, I might have felt the same way about yours when I was young. But I've seen so many forms of life in the last five hundred centuries that they all seem natural to me now..."

While he talked, Omega caused the vision of the spider-like creature to vanish, and in its stead Nona saw the bent figure of an aged, bearded man. At the sight of this senile being she closed her eyes and relaxed. Then she burst our crying. Omega cocked a sympathetic eye at her. He hated weepy women, but if Nona had stooped to tears, there was a reason. "Nona, what's wrong?" he queried, gently.

"Mark..." She choked as she tried to tell him. "He's... he's dead!"

"Dead! What's he mean, the young loafer? He knows he can't die—it would upset all my plans. I'll show him! Where's the body? I'll bring him back..."

He stopped short as Nona, still sobbing, waved an arm toward the two portholes at the side of the cabin. Through them he could see the sunlit waves of the North Sea. Then, surprisingly, he chuckled.

"Fell overboard, eh?" He chuckled again, Nona looked at him in astonishment. "That's all right then. Now start at the beginning and tell me what happened."

NONA'S eyes widened in sudden hope, for Omega was something close to omnipotent to her, and if he said that Mark might not be dead...

Abruptly she broke into speech, nearly incoherent at first, but getting clearer as hope calmed her nerves. She told of the storm which had come up during their trip to Stadtland, on the coast of Norway; of how the wind had driven the ship toward the south and west, far off its course.

Mark had made her keep to the cabin, and when he was lost she had known nothing of it until the storm had abated. Sven, the captain, had broken the news to her in the morning, and since then the ship had been searching, fruitlessly.

"Well, what are you worrying about?" demanded Omega, his wrinkled face beaming with an impish grin.

"He... Can't he drown?"

"Of course not. Drowning is suffocation, And how can a man who doesn't need air suffocate?"

"But Mark and I both breathe. And if I try to stop, my lungs go to work as soon as I stop thinking about it. I suppose it's the same with him."

"Of course," Omega agreed. "But that is only because there is a nerve center in your brain which controls such involuntary actions. The fluid which I injected into your veins didn't stop that from working, but it did remove the necessity of having a constant supply of oxygen. Therefore Mark's respiration would continue normally, but it wouldn't matter to him whether he was breathing air or water, or strawberry jam. He doesn't require oxygen for the function of his body.

"I told you once that your body and Mark's are burning the power from the radioactive element in your blood. You need no other fuel to keep you alive. No food and consequently no oxygen to support the combustion of that food. All you require is water, and Mark is getting plenty of that. Yes, indeed, I imagine he's getting enough water to last him a lifetime." He grinned happily.

"But it is sea water," objected Nona. "Wouldn't that..."

"No—it wouldn't," Omega said, impatiently. "I can't explain the exact nature of your present body chemistry. You couldn't understand it. But you know very well that you have lived without eating since I gave you that injection several months ago. So you should be willing to take my word that sea water is as safe for Mark as spring water."

Nona was smiling quietly now. Where another woman might have let herself go into hysterics from reaction, Nona's temperament forbade such a weakness. Normally calm and placid, she was busily telling herself that she had known it all the time. That Mark couldn't be dead. Only the grueling hours of constant searching could have made her temporarily lose hope. But even so she wanted to hear more assurance from Omega.

"It's October," she pointed out. "Cold and exhaustion..."

"Nonsense! Mark can't become exhausted. Not for several thousand years to come, anyhow. Radioactivity supplies his energy, more than he can use by muscular activity. He could swim the Atlantic without tiring! And as for cold..." Here Omega hesitated. "Take a look in that mirror." He leered at her unnervingly.

Nona obediently crossed the cabin to a highly ornamented full-length mirror, Her reflection showed a beautifully formed body, which womanlike, she briefly admired, even lifting a hand to tuck away a stray, ebon curl. She noted, too, the trimness of her attire. A short jacket of satiny material, which came as low as her lower ribs; then an expanse of tanned skin, beneath which was a loose-fitting pair of shorts of the same shiny cloth. But that was what all the women wore in the summer. The only difference was in the colors and—

"I see it's dawned on you," said Omega. "The temperature is somewhere near freezing. Even the tough lads out on the deck are better clothed than you."

"You mean that our blood protects Mark and me from cold?"

"Of course. You would have noticed it sooner or later, if I hadn't told you. Radioactivity doesn't depend on temperature, and as a result your sensory nerves aren't giving you any warning of discomfort because of the low temperature. Your chemistry operates with equal efficiency over a wide range of heat fluctuation."

"Then Mark is safe. But where is he?"

"How should I know? Suppose you go on deck and tell Sven to point the ship toward Norway. Tell him you've had a vision or something, and that you know that Mark is alive and will rejoin you, later. He worships Mark, and that will be a kindness. You can say that Thor himself has revealed that he has given Mark a mission to fulfill, and that he will return when he finishes.

"Sven will believe that a lot quicker than an explanation of the real facts. And in the meantime I shall go and find your missing husband. And keep your chin up. I dare say it's a very lovely one, although being a spider I wouldn't know."

There was a twinkle in Omega's aged eyes, to match the impish grin, when he abruptly vanished.

NONA sat still for a moment, smiling toward the place which Omega had just quitted. Then she opened the cabin door and stepped out. A moment later a flock of sea gulls which had been perched in the rigging, took sudden wing, startled by the wild shouts of joy that were rising from the deck.

Yet if Omega had returned and told them of the thing he had just discovered, those shouts might have turned to groans. Omega, a disembodied intelligence of the first order, had been perfectly confident that he could touch Mark's mind at once.

Such a mental feat was a problem of simple accomplishment to one of his intellect. Fifty thousand years of projecting his mind to the far ends of the universe, had given him a mind power not surpassed anywhere. His over-active curiosity concerning the myriad of life-forms that infest the endless number of worlds in a dozen galaxies, kept him always alert and always a dynamo of mental energy. And yet he couldn't contact Mark!

The mind-pattern that was Mark, had temporarily ceased to exist. For that mind pattern was not complete without all its memories. If a disembodied intelligence can shudder, Omega came very close to it. For in that instant, the thought came to him that the only answer could be that he was dead, after all.

And Omega had become very attached to Mark.

In Mark and Nona he had pictured the means of populating the earth with a type of human far superior to the product that nature had blindly created. He had chosen them as Adam and Eve for this race of the future because of the dominating good in their characters. And now, it seemed, Mark had ceased to be.

But in the instant that this thought came into existence, Omega's brilliant mind rejected it. There could be another reason for his failure to contact the mindpattern that he knew as Mark.

Since their last intercourse, Mark might have changed. His ideas, his fundamental philosophy of life might have altered for some reason, and thus created a mindpattern that was unrecognizable. Omega rejected this also.

Only one alternative remained. Mark had been washed overboard. It was likely that he had received a sharp blow on the head as he went over. If this had happened, then it was possible that the blow could have damaged his brain. And the mindpattern had changed as a consequence.

BUT this complicated things dreadfully. Concussion could cause a partial or even complete loss of memory. Fracture might do either, and in addition might result in irreparable damage to the brain tissue. Mark may have changed only to the extent of losing some of his memories, or he may have been reduced to a hopeless idiot. Either way Omega must find him. For he alone possessed the knowledge to restore him.

Not knowing the extent of the pattern change, Omega would have to mentally visualize a pattern containing Mark's present dominant characteristics. Then he would have to make contact with any being possessing that pattern. There was every chance that no living being would respond to such an imagined mindpattern. And if one did, it would probably be the wrong man.

Yet it was the only way. He might have to project a million of them before he hit upon the proper one. But with an energy that was definitely not human, he set about the task.

For two days he labored mightily at his problem. He visualized patterns of the most simple structures, then advanced to others containing some of the memories that he knew were Mark's. Nothing resulted.

Exasperated, he went back again to the more simple patterns, thinking he might have failed to imagine some little detail. Then ahead again to more complicated ones.

Omega knew all about Mark. He had delved into the innermost recesses of Mark's memory until the mind and character of Mark were as familiar as his own. Each pattern he was forming contained more memories than the last. He had reached the point in the memory chain where Mark had met Nona, when he suddenly realized that he couldn't hope to succeed by the present method.

There was one pesky thing he had forgotten. And that was that Mark, wherever he was, now had some new memories of which he knew nothing. Since the time he had fallen overboard Mark had been experiencing things that Omega couldn't know about. This, of course, wouldn't make any difference ordinarily. Omega could always contact a familiar mind-pattern, even though years of time had passed and new experiences had partially changed its former structure. But that was because the new memories were only a small portion of the total memories of the pattern. In the present case the new memories would constitute almost, the entire pattern.

But there was another way. And though Omega cringed mentally at the thought of trying it, he knew very well it was the only course he could take. The method lay in an ability he had discovered shortly after he and the other members of his dying race had cast off their bodies and had taken residence in the imperishable brain containers which now rested on a dead and airless moon. He, differing from his compatriots, hadn't been satisfied to stay there, whiling away the ages in abstract thought. His ego had ventured away from the brain which had given it birth, and he had gone forth to explore the universe.

He could think himself instantly to the far corners of the universe. He could construct and inhabit any sort of body he wished. And he had full control and use of the vast stores of energy which are everywhere in space.

And then, almost accidentally, Omega had discovered that he could travel about in time, as well.

He had tried it, gingerly at first, and found that there were decided limitations. He could observe past happenings but could take no part in them. He couldn't take a body and mingle with the beings he was interested in, because he hadn't really been there when the things had happened. Nor could he force himself backward in time beyond the date of his own birth.

That fact had handicapped him, for he was young then, and therefore, couldn't go back very far into the history of any race he might be studying. But as far as it went, the ability had its uses.

But he had come to grief when he had tried to clear up a hazy point in the past of his own race. The event which he had wanted to watch had taken place within his own lifetime, and, in fact, was connected with some of his own past operations. The trouble came when he had run across his own former body in the course of his study.

The two identities, being so near alike, had merged! He had been forced to live his lifetime all over again, up to the point where he again existed as a bodiless entity. That had been a great nuisance and a hideous waste of time.

The experience had taught him an extreme caution in connection with this special ability. True, he had used it again a few times, when his curiosity had overcome his caution, but each time he had been half frightened to death for fear he might run into himself again.

And now, after thousands of years of aimless perambulating, the thought of having to repeat himself over again gave him a disembodied fit of ague.

He would, however, try it once again.

This process was, if anything, a longer one than the business of trying to match mind patterns. It was a simple thing to place himself in the position the ship had occupied during the storm. And he had the satisfaction of observing Mark's head strike the ship's rail a glancing blow as he was washed over. That would teach him to be more careful.

The fact that Mark almost immediately began to strike out in a firm, distance covering stroke, proved that he was not greatly damaged. But the fact that he didn't once look around for the ship and try to reach it, also proved that he had no memory of it.

In the few moments from the time his head struck the rail until he began to swim, he had regained consciousness, devoid of memory!

And here began Omega's troubles. He couldn't speed up the course of events which had happened and were unchangeable. He couldn't observe them at high speed as one would a moving picture of the same events. He had to watch them as they happened.

Until Mark had found some spot where Omega could be reasonably sure that he would stay for a few days, he didn't dare jump back to the present and start a search for him. Mark might in the interim have moved to a distant point.

Then, just when Omega was satisfied that Mark would very likely remain for a few days in Scarbor, inasmuch as he had followed him as far as the edge of the city and witnessed his capture, events started happening which made him decide he had better watch for a while longer.

MARK gazed around the gloomy interior of his cell. It was devoid of furniture, though it wasn't entirely unadorned. In one corner there was a contraption of chains and manacles fastened to the wall. On the floor underneath was a pile of human bones and a jawless skull. Mark gulped. "Hello," he said to the skull. "Fine day." But the skull only grinned, with a knowing look to its empty sockets.

Whenever Mark straightened up, he banged his head on the ceiling. The cell had a foul smell, too. Altogether he was disinclined to stay for any great length of time. His eyes returned to the skull, he leaned over, picked it up, and looked absently into the eyeless sockets. They seemed to look back at him with a prophetic expression. He hastily returned the thing to its place on the top of the heap. No, he wasn't going to like this place.

Mark crouched on the chilly floor and tried to remember more about himself.

He didn't succeed very well, because every time he was on the track of something, the vision of the lovely lady intruded. And every time he saw her, she became clearer and more desirable, until she was like an ache in his heart.

Little memories came back.

Once he saw her breaking twigs and arranging them as if to build a fire. Again she would be swinging along at his side, as they made their way through a dense wood... That woman who was so desirable, was his! There was no doubt of it now. And he must find her. Somewhere in the confused past lay the clue that would lead to her. He must remember!

He sank deep in thought.

As the morning sun rose higher in the sky, it became lighter in the cell. Mark was startled out of his reverie by the sight of another row of cells, on the opposite side of the corridor. The one directly across from his contained an unkempt individual who was leaning against the bars of the cell door, regarding Mark with a, quizzical expression. A fiery shock of red hair threatened to cut off his vision, although he evidently could see through it, for he grinned when he realized that Mark saw him.

MARK grinned back. He thought he should say something, but couldn't think of anything. Red-head broke the silence. "A new customer," he observed. "What are you in for?"

This one spoke in a new dialect, but Mark translated it automatically into the English of his youth.

"I don't know," Mark confessed. "They just grabbed me and hauled me in."

"Didn't they beat you up?"

"No, just a few blows with their clubs."

"You're lucky. You must have broke curfew, and they usually jump a curfew breaker and beat him up before he knows what's happening."

"Why?"

"Serious offense," explained the other. "They're all so scary in this place that they pass laws to keep everybody off the streets after dark. The only ones who break curfew are thieves and murderers. And the night-watch always beats them up—when they catch them."

"I see... But they didn't catch me after dark. The sun had been up for quite a while."

"It's still curfew time now," informed the red-head. "The gong rings at about eight at night, and then it doesn't ring in the morning until about seven. There it goes now!"

A deep-throated chime filled the air of the cell-room with its throbbing vibration.

"I'm Murf," volunteered the red-head. "What's your name?"

"Mark."

The sound of the gongs had awakened other inmates of the prison.

In the cell next to Mark's a man called to Murf. He spoke in a clipped accent, and rolled his r's. Mark decided he was a Scot, known here as a Mac.

"Have you thought of anything?" he inquired.

"No, Oateater, but I will," said Murf.

"And what'll ye use to do it with?" retorted the Scotchman. Then he laughed heartily. "That last one you tried will go down in history. You might not have been sick when you pretended to be, but you surely were afterward. What with the flogging, and all." He laughed again, and Mark wondered vaguely if there was something the matter with his sense of humor too. But Murf wasn't laughing either.

"It would have worked," maintained Murf, "if the man had been carrying the keys."

"You were too busy having a convulsion to look."

"All right. All right. Have a good laugh. But when I do get a good scheme, don't expect me to waste time opening your door."

This quieted the Scot. Mark wasn't sure what was meant by their conversation, and he didn't get time to figure it out. His attention was distracted by an unholy clamor further down in the cell block. Men were rattling the cell doors and shouting for food.

Presently the massive door from the courtyard swung open, admitting three men and a flat cart. Two of the men were obviously soldiers. They were armed with swords and daggers, and wore breastplates of lacquered armor. These were two of the four guardsmen he had seen briefly the night before. He was to learn later that these prison guards were soldiers in the service of the city constabulary forces. They were of a slightly higher order than the members of the night-watch, a separate branch of the same force. They were better armed and better paid. Besides their soft berth, as guardsmen, they were occasionally called out for duty in quelling civil disorders beyond the capacity of the night-watch.

The soldiers took positions at each side of the door while the third man pushed the cart to the center of the corridor, and distributed the wooden plates.

Mark received his ration and looked at it distastefully. Even if he had wanted food, he certainly wouldn't have wanted that mess.

"Murf," he called, his voice competing with a medley of eating sounds.

"Umph?" answered the red-head, chewing mightily.

"It just occurred to me that I'm guilty of the crime of breaking curfew, even though I never heard of it. What's the penalty?"

"Drawin' and quarterin'," replied Murf, swallowing a prodigious chunk of meat.

Drawing and quartering.

MARK nodded. Then he realized that he didn't know what drawing and quartering was. He asked Murf. Murf tossed back his hair.

"Listen! I told you that curfew breakers were either thieves or murderers. Therefore they're treated as such. Drawn and quartered!"

"I heard you," Mark said. "But what is it?"

"Say, where did you come from? That's standard punishment all over."

"Oh," said Mark. "Is it?"

"You're a funny one," declared Murf, looking at him sharply. "But if you want to know—they nail you to a wall with spikes through your hands and feet. Then they stick a knife in your belly, reach in and grab one end of the mess that's in there, and draw it out slowly. That's the drawing part. It lasts for a while and you don't die right away if the fellow knows his job.

"You understand that? Well—

"Then they cut you in four. That's the quartering part. I'm against it, myself. And there's only a slight chance of getting any other sentence. Sometimes the magistrate gets a notion to vary the monotony by having a man burned at the stake, or hung, but it's usually drawin' and quarterin'."

"Sounds messy," was all Mark said.

The redhead went back to his meal with a relish. He finished, wiped his mouth on a sleeve, and skimmed the wooden plate in the direction of the big door. Mark had been inspecting the rusted bars of his cell door, but looked up at the sound of the clattering plate.

"Are you still hungry?"

"I'm always hungry," replied Murf.

Mark nodded and grasped two adjoining bars of the door. No strain showed in his face, but the sinews of his arms stood out like steel cables and the muscles of his shoulders knotted and threatened to push through his bronzed skin. Slowly the two bars bent. As they did so, the lower ends lifted out of the holes in the bottom of the door.

No other man could have maintained that terrific pressure even if he could have exerted it. But the radioactive element which supplied Mark's energy was constant, and built up broken-down cell tissue in an instant.

Eventually the bars bent so far that they were clear, and Mark jerked them asunder with a savage wrench.

Then he bent over, picked up his plateful of garbage and calmly stepped through the opening. He handed the dish to a pop-eyed Murf. Murf took it, numbly.

"Look," he finally whispered, "I'm not so hungry now. Do you suppose you could do that to my door?"

Mark nodded. "I don't see why not." It didn't take so long this time, for he had noticed how the bars lifted through the holes. He took his grip further down, and the job was accomplished in half the time. Murf stepped through, the plate of food still in his bands.

A sort of subdued bedlam arose when the other prisoners saw what had happened. Each prisoner whispered his demand to be released, too. Mark had no intention of taking time to operate on any more cell doors. He was searching for an exit.

Abruptly the clamor ceased. Mark had found the window, but he turned to see what had happened. He saw Murf with his hands raised for quiet.

"It's broad daylight," he told them. "And if the whole gang breaks out, they'll nail us right away. But the two of us can make it. There won't be any trials until after the holidays, so you're safe for a while. If you'll swear allegiance to my cause, we'll come back on the first moonless night and turn you loose. What say?"

Another hushed murmur, not quite as loud as the last, and Murf darted down the corridor to join Mark. He looked up at the window, about nine feet off the floor. It also was barred. As if the two men had rehearsed the thing for months, they went into action.

Mark leaped for the bars, grasped them, and Murf moved against the wall, placing his shoulders under Mark's bare feet. Standing thus, Mark was able to exert pressure. It took a little longer, for the bars were fastened deeply into the stone of the jail wall.

It was a matter of several minutes before the two fugitives found themselves safely in an alleyway back of the jail. Murf was panting with excitement and exertion, and seemed anxious to get away from the immediate vicinity as quickly as possible. Impatiently he tugged at Mark's arm, muttering urgently, as he regained his breath.

"Calm yourself, friend," admonished Mark. "They don't even know we've escaped, as yet. But if we attract attention by hurrying too much..."

"You're a cool one," Murf said. "Who are you, anyway?"

"I don't really know," Mark admitted. "I've got to find out. That's why I couldn't stay in there any longer."

"Oh, sure. You wasn't worried about being kilt at all."

MURF glanced at the winged helmet, which Mark still retained, and an expression of sly cunning crossed his face for the briefest instant.

Mark missed the look, for they had reached the end of the alley and he was inspecting the street before them. There were several pedestrians about, and one ox-cart was progressing slowly in their direction. Mark noticed that there seemed to be no uniformity of dress among those on the street.

There were a few women, apparently of the poorer class, and in the next block he could see two men who were probably soldiers. Across the street was a party of four men, partially intoxicated, whom he took to be sailors returning to their ship after a night of carousing. Except for the fact that all those in sight had more clothing on than he, it was probable that he could pass unnoticed on the city streets.

"Don't worry about it," said Murf, at his question. "This is a shipping town, and they're used to seeing all kinds of people. Even Vikes like you."

"Vikes?"

"You don't even know that, do you? You're a Vike. I can tell by the tin hat. But it's all right. The Brish and the Vikes are at peace right now. Just the same we had better get you some different clothes, because they'll be looking for a Vike when they find we escaped."

"But they didn't know that when I was captured. They asked me if I was Mic or Mac."

"The night-watch is stupid," Murf explained. "But when they tell the prison captain what you looked like, he'll know. So we'd better get rid of that hat."

Regretfully Mark tossed the winged helmet back into the alley, and they proceeded at a leisurely pace down the street—away from the prison.

"Where shall we go?" inquired Mark.

"Leave everything to me," advised Murf. "I've got friends in this city. They'll take care of us." Murf spoke in a tone that any twentieth century ward-heeler would have recognized at once.

Mark decided he might as well go along. He would meet new people, and that would help him remember. Even now his mind was coping with a vagrant memory. It had to do with Murf's assertion that he was a Vike. Earlier in the day, he had told the night-watch that he was a Yank, and though he didn't know why he had said it, it had seemed to be right at the time. But now the word Vike seemed to strike a responsive chord. It wasn't quite right, his memory insisted that the word was "Viking," and it had an air of familiarity.

Suddenly bedlam swooped down upon them.

Around a corner swung an ornate carriage drawn by sleek horses, and flanked on either side by a mounted soldier. Without warning, the horses suddenly reared, kicked at the traces, and dashed madly down the street!

THE mounted soldiers, taken by surprise, were slow to act, and the carriage had a good start before they thundered in pursuit. Their mounts were swift and they were gradually overtaking the runaways, when an excited shout arose from the people lining the street. Directly ahead of the careening carriage was the ox-cart, effectively blocking the way. The soldiers could never close up the gap in time to prevent the crash.

Mark caught a fleeting vision, through the window of the carriage, of a terror-stricken girl with an infant clasped to her breast. Abruptly he went into action.

The nearer horse was opposite him when he made a prodigious leap and landed astride its back. The frightened horse almost went to its knees. Mark made a frantic snatch for the reins of the farther horse as it slewed about, threatening to dash them all against a building. His lightning grasp was sure and in another instant he had brought the heads of both horses back. They came to a stop with several feet of safety short of the impending crash.

Before Mark could realize that he was really quite a remarkable fellow, an excited crowd had rushed him and raised him aloft, shouting and parading around the carriage.

Bewildered, Mark began to notice things. This joyous throng seemed to think that he had done an heroic thing. That might mean that the woman in the carriage was a person of great eminence, and beloved to those who were honoring him.

He noticed on the second time around the carriage that the door was opening and a man, resplendent in a handsome uniform, was getting out. The crowd abruptly stopped and placed him on his feet before the uniformed man, then respectfully stepped back.

The man held out his hand. Erect, still pale from his experience, he gave an impression of intelligence and culture above that of the others around him. There was a kindliness about his eyes that was at once engaging and yet seemed to hide a certain ever-present sadness.

"Your name, my friend?" he asked.

"Mark." He hesitated. "Should I know yours?"

Surprise appeared on the man's face before he could control it. "Perhaps you should," he replied, smiling. "I am Jon, Duke of Scarbor. And I wish to extend my sincere thanks, on behalf of Her Highness and myself, for your heroic act."

Mark nodded, embarrassed and not certain if the customs of this land required him to speak or act in any specified manner toward a man who was obviously one of the ruling class. He liked this man, Jon, and didn't wish to offend him.

"As a token of gratitude, it is my desire to reward you in a way that would be most pleasing to you. Suppose you name the reward. Anything within my power."

There was only one thing he desired, Mark was ruefully thinking, and no man could grant that—the return of his memory.

"There is nothing," he said. "Anyone with the opportunity would have acted as—"

Murf, suddenly pushing his way through the crowd, interrupted him. "Your Highness," he panted, dodging the hands of those who would have stopped him, "there is a reward that would please this man!"

THE Duke waved aside the soldiers who pounced on the red-head before he came within six feet of the carriage. "Speak," he commanded. "What is this reward?"

Murf leered at the soldiers. "A pardon!" he answered, and grinned at the wondering glances of the crowd. "This man comes from a far country. Without knowing of the curfew laws he entered the city too early in the morning. The night-watch clapped him in prison about an hour before the gong. And Your Highness knows the penalty for curfew-breaking."

The Duke shuddered. "Quite. But if he was placed in prison how is it that he is now free?"

"Upon being informed of the penalty he must suffer for his innocent trespass, he escaped. But he will be tracked down without Your Highness' pardon."

The Duke smiled. "I am in your debt for this information," he said. "You have shown me how I may avert a wrong. But how is it that you know all this?"

Murf glanced nervously about as if wondering whether to make a run for it, then squared his thin shoulders. "I also was unjustly imprisoned," he said, trying to look as virtuous as possible. "When I told this man how I was borne false witness, against, he took pity and freed me also."

The Duke's eyes twinkled. "A Mic, eh?" he chuckled. "Always unjustly accused, always downtrodden; but never without a likely sounding story. However, I am in your debt. There will be two pardons and quickly."

A cheer went up from the crowd as the Duke reentered the carriage. But the smile of approval from his pretty wife probably weighed far heavier in his scale of values. Neither could guess that as a ruler, he was inviting disaster.

Mark and Murf were both lifted to the shoulders of enthusiastic men and carried behind the carriage back to the prison. This time they entered the office of the captain, which was much better than being forced through the courtyard to the cell-block.

A short time later Mark hurried toward the alley from which they had earlier emerged to the street. Murf scurried after, quite puzzled. He wasn't kept in suspense long. With a dive Mark swooped into the alley and came out a moment later, smiling happily. He brushed same mud from the gleaming surface of the helmet he had retrieved, and placed it jauntily on his head. Then he patted the axe which had been returned to him. Murf shook his head, mystified.

"It looks like losing them gimcracks is the only thing about the whole business that really had you worried," he remarked.

MARK nodded. He didn't explain that the axe and the helmet were the only concrete links between him and the past. Nor that it was his hope that the sight and feel of them would stir his memory. And it is just as well that he didn't, for then Murf might have seen that he lost them again. For canny Murf was cooking up a plan, whose ultimate success depended on Mark's innocence and gullibility.

"Why did you lie?" Mark inquired. "You didn't tell me you were falsely accused. And I'll bet you weren't."

Murf laughed. "No. Sure, it just sounded better that way. His nibs didn't believe me anyway. But I couldn't tell him that I was guilty of treason. He wouldn't have pardoned me for that."

Mark thought for a minute. "Then you took a chance of being sent back to prison when you spoke up for me."

Murf waved a hand airily. "Sure. Sure. It was a gamble, but it turned out all right. And I paid back a debt. You got me out, and I got you a pardon."

"Still, you took a dangerous chance. Treason is a grave offense. Now I'm in your debt." Through Mark's gratitude ran a tiny dark thread of suspicion. Beware the Irish bearing gifts.

Murf glanced away to hide triumph in his face.

"Forget it," he said. "Come on with me."

Mark saw no reason why he shouldn't.

The way led through a squalid section of the town, and little attention was paid to Mark's singular dress—or lack of it. There were sailors from far lands, fish-peddlers with their carts, laborers, an occasional lady of the street, and innumerable strutting soldiers.

Once an armorer in the doorway of his shop stopped Mark and asked for a look at his axe. Mark handed it to him and wondered at the man's excitement.

"The ancient metal!" gasped the armorer. "Where did you get it?"

Mark shook his head, uncertainly. "I've always had it," he answered.

"But it's made of the ancient metal, which does not rust! It is found nowhere but in the ruins of the cities of our ancestors. Modern steel-men cannot duplicate it. How much will you sell it for?"

Mark hesitated, and Murf decided to take a hand. "What will you pay?"

"A thousand coppers!"

Murf turned to Mark. "It's a good price," he said. "You can get an ordinary axe for ten. You'll need money. You haven't any, have you?" He looked hopefully toward Mark's single pocketless garment.

Money... medium of exchange... with which one could buy the necessities of life. No! he decided, abruptly. "I need the axe, but I don't need money. Sorry, no sale."

Murf shook his head and they went on their way. Mark was becoming acutely aware of the fact that somehow or other he required no "necessities of life."

THEIR destination was a haberdashery shop. The proprietor, a wizened man with shrewd eyes, was both surprised and upset at sight of Murf. He came round the counter, closed the door and pulled curtains across the windows.

"Murf!" he exclaimed, in tones he might have used upon being told that an epidemic had struck the town. "You mustn't come here! They're sure to find you. It will jeopardize the cause!"

Murf laughed. "Hush your blather, man. Is your leader as stupid as you? I have been pardoned. This is Mark, who will some day be our king!" This last announcement came as a distinct surprise to Mark, who had some remembering notion of the word's meaning.

Murf went on rapidly, while Mark listened with incredulous ears. Murf's story proved him to be an accomplished liar and an adept at the perhaps forgotten art of the buildup. The haberdasher, who was named Smid, listened with avid interest, now and then glancing admiringly at Mark.

"He is a fit leader," Murf concluded, pompously. "One who will administer justice, not persecution."

Smid nodded. "And one who will inspire the cooperation we need from our loosely-joined allies. The other groups have never fully trusted you, you know." His eyes twinkled maliciously.

Murf nodded. "My cursed red hair," he said. "They've always thought I was with the Mics, just because my grandfather came from Eire. The dolts! But they'll trust this Vike, for the Vikes are not intriguers. If they wanted anything from the Brish they'd descend in their ships and take it."

Smid nodded and seemed perfectly willing to accept Mark at face value. Mark, who found his attitude unbelievably naive, followed Murf into the living quarters in the rear.

"Look," he said. "Would you mind explaining all this? I don't know what this is all about, and I'm pretty sure I don't want any part of it. It seems to me you might have the decency to consult me about it before you go around slamming crowns on my head."

Murf looked at him incredulously, and then changed his expression to a sympathetic smile. "I had forgotten," he said. "You don't know that I'm giving you a chance to help the downtrodden and oppressed. Man, you have not the right to refuse at all. 'Tis your sacred duty. Listen to me."

AND Murf explained. From his deft and Celtic tongue rolled an eloquent depiction of the terrible conditions of the land. Of the unbearable taxation of the poor, and lavish ease and luxury of the nobles. Of the inhuman penal code, torture, corruption, squalor—all dripped persuasively from his flow of words until at last the bewildered Mark was more than half convinced, and sure only of not being sure of anything.

Even apart from his obligation to Murf, Mark really felt that this might be a cause to warrant the aid of any red-blooded man. This thought brought him up short. His blood was blue.

Not that it changed his ideas, but it reminded him that he must not lose sight of the fact that he was different, and that he had to find out the reason for the difference. He knew that there lay the clues that would lead him to the lovely lady of his half-awakened memories.

"But you said I would some day be king," he said.

"Of course. The various groups who are working for the betterment of this country, are loosely joined because they lack a real leader. You will supply them with one. They will unite under your leadership."

How was Mark to know that Murf was a master of the patter of the soapbox agitator? He sounded sincere enough and clever words are delicate but often irresistible webs to trap and hold fast the innocent.

"But it doesn't make sense," Mark insisted, yielding inch by inch. "I am an outsider, not even familiar with the country."

"Makes no difference," said Murf. "The Brish are a people who require an impressive leader, or they won't move. They must have a king, even though that king has to relegate all the duties of his kingship to more capable men. The Brish need him as a symbol. And your part in the coming events will be to bind our members under your leadership, and let them revere you as their deliverer. And in the meantime, I, as your lieutenant, will plan the moves to be made."

Mark said nothing.

Murf, who had stripped and was busily washing off some of the prison grime, sensed something of Mark's thoughts. "Your position is an honorable one," he pointed out. "It will further a cause which might otherwise lack the impetus to get it started. If I am willing to continue the work without hope of reward, even of recognition, you should be. To you will go all the glory and adulation. But to remove the yoke of oppression from my people, I consider it a small sacrifice. Surely you can have no objection." His tone was convincingly pious.

Mark suddenly felt ashamed of himself. "I'll work with you," he said simply. "But there is one thing I must insist upon."

"What is that?"

"When this work is done, you must take over yourself. I can't be tied down here. I must be free to take up my life from the point where I lost it. Some day I'll remember, and then I shall leave."

THE days that followed were busy ones for Mark. Murf and Smid contacted members of rebellious groups in the Duchy of Scarbor, presented Mark, and proceeded to win them over to the idea of a new leader. The idea took hold with unanimous enthusiasm. Stories of Mark's unjust imprisonment, his miraculous escape and the adroit manner in which he had grasped the opportunity to obtain his, and Murf's, pardon, had traveled ahead of them.

The story had lost nothing in the telling, having already been considerably embellished by Murf. He had credited Mark with having planned the whole episode, and with admirable modesty had toned down his own part in it.

Mark allowed this, though inwardly cringing at the deception, for he realized that he was playing a necessary part. Occasionally there would be doubters, who found it impossible to believe that a man's arms could be strong enough to bend stout iron bars. So Mark would patiently show off for them, feeling a little silly. On request, he gave exhibitions of axe throwing, in much the same fashion as twentieth century politicians had gone about kissing babies and submitting to initiation into Indian tribes.

In the course of his campaign Mark ran across many evidences of poverty and oppression, and his anger mounted along with his growing urge to do something about it. Murf and Smid were delighted at the success of his efforts to bring all the rebellious factions under his leadership. His speeches, prepared by Murf, were delivered with fervor, and conviction. Mark was no orator and got fussed when a crowd cheered Murf's canny platitudes, but it was all in the day's work.

The Duchy of Scarbor, of the four that comprised the country of the Brish, was the most important nut to crack. It was the largest and most thickly populated, and it harbored some of the more powerful of the ruling nobles. The Duke of Scarbor, he learned with a twinge of sympathy, was a mere figurehead, forced to do the bidding of the other nobles. They controlled the army and owned the greater part of the land. And although Jon, the duke, made efforts to alleviate suffering among the poorer classes, he was invariably overruled. The nobles, interested only in their own welfare, considered it good policy to keep the people properly to heel.

Lunn, the province to the south, was the capital of the country of the Brish. It was presided over by Aired, Emperor of the Brish, who was the father of Jon of Scarbor. He too, was popular with the people, but helpless to do anything for them. His hands were as thoroughly tied by the Council of Peers, as were his son's by the ruling nobles of Scarbor. This Council, it appeared, were representatives of the various nobles of the four Duchies, empowered to act in their behalf.

But though his success in organization was such that the rebellious factions of the Duchy of Scarbor were solidly united in a matter of days, Mark was troubled by a sense of futility. Time's passage had not produced the desired effect on his memory. The associations which should have reminded him of incidents in his past were failing of their purpose. Could it be that he was living a life so foreign to his former one that there were no parallels, no similar occurrences that he might match up and start a train of recollection?

THERE was only one thing to console him in his constant quest for knowledge of his past. During the long nights when his companions rested and slept, he was able to think more clearly. Each night he was in a different place, as they campaigned about the country, but his surroundings meant little to him. For no matter where he was, he could always conjure up the vision of Nona, the woman he knew was his.

And lately he was able to associate her with the presence of another person. Who this person was he couldn't quite grasp, but the feeling was there that it was someone who had played an important part in his former life. And Nona was clearer, too. Sometimes he could hear the low throbbing of her laugh, and it never failed to leave him with a sensation of happiness and desire.

The Duchy of Scarbor had been thoroughly canvassed and thoroughly organized by the end of the second week of the harvest holidays. The final week of the holiday period was to be devoted to games in the great arena. These games were a gesture of the nobles calculated to take the minds of their subjects off their troubles.

Murf and Smid decided that inasmuch as the following days would bring a return to normalcy, it was high time to strike their blow.

First all prisoners must be released from the jails. Most of these would immediately join the cause and swell their ranks. It was decided that the first jail delivery would be made from the prison from which he and Mark had escaped.

Murf laid his plans with admirable thoroughness. Instead of going about the business furtively, he dressed several men in uniforms corresponding to, those of the night-watch. Mark was attired in a sergeant's outfit, except that he insisted on keeping his axe.

Boldly they marched through the streets long after curfew, headed for the jail. The night was cloudy and the moon obscured. This fitted their plans, for after the jailbreak it would be necessary for the prisoners to scatter and find concealment with friends, and every minute on the streets there would be danger of being sighted by genuine patrolmen.

The plan went off like clockwork—up to a certain point.

Reaching the prison the party entered the courtyard and stopped before the huge oaken door. Mark hammered on it with the butt of his axe. The door was supposedly impregnable to anything less devastating than a battering ram, and could only be opened from inside the guardroom. The inner door was equally formidable from the side of the cell block. It also could be opened from the guardroom only.

But evidently the authorities had never considered that a weakness was present in the fact that the guards were in the habit of opening the outer door whenever the night-watch brought in a prisoner. The open-sesame was the hammering of the night-watch sergeant's club.

After a moment the door swung outward. Before the startled guard knew what was happening, he was felled by an enthusiastic club. His three companions were downed before they could move.

A ring of keys hung on a nail beside the inner door. In a matter of moments Mark had swung open the inner door and released the prisoners. A search of the prison revealed several other blocks of cells, one to match each key on the ring. The locks on the doors of each row of cells were opened by a single key. Over two hundred prisoners were released in the course of less than a half hour.

THE thing had been accomplished with the utmost quiet. Mark was congratulating himself on their efficiency when he received a rude jolt. In the guardroom were only three unconscious men!

Hastily he gave orders to leave. He didn't know how much time had elapsed since the missing man had regained consciousness. He may have already summoned help. Why hadn't he taken time to bind them or at least have left a guard over them?

But there was no time now for regrets. He swung the outer door open, and realized at once that the damage had been done. The sound of a large number of running men echoed down the street!

They were nearing the archway that led into the courtyard. In the few seconds that remained, Mark put into effect the only plan that had a chance of success. He deployed his men in the shadows at the sides of the archways. The door to the guardroom gaped open, illuminated by a glow from the oil-lamp within.

It was Mark's hope that the approaching men would head immediately for the door, and that they would fail to see his men in the darkness outside.

The sound of slapping sandals was growing louder, and Mark's heart sank as he heard the occasional clank of armor. Sword-hilts striking against breastplates! These were soldiers coming, not poorly armed watchmen. His eyes, accustomed to the darkness, could see the grim expressions on the faces of his men, indicating that they had interpreted the sounds as he had.

But the way they held their clubs and knives told him, that even though outnumbered and outclassed in armament, they would give a good accounting of themselves if it came to a fight.

The foremost of the soldiers dashed through the archway and continued, without breaking his stride, toward the lighted door. His eyes, partially blinded by the dim light, missed the men crouched in the shadows. Those who followed dashed right after him.

A steady stream, numbering at least fifty armored soldiers, crossed the courtyard at a run. Mark was elated at the success of his strategy. He was calling for his men to break cover and make their escape when abruptly a laggard soldier puffed through the archway. He was a heavy man, and had little breath left when he confronted Mark's party. But what small amount of wind he retained, he used in a hoarse yell as he drew his sword and swung it at Mark.

Mark stepped out of range of the swing and then felled the man with an axe blow as his momentum carried him past. But the yell had done its work. The last two of the soldiers to dash into the prison had heard it and were calling to those who had gone before.

One man went down without striking a blow, but the other three were cutting at him viciously. His own men were not slow in sizing up the situation, however. In a body they dashed forward and belabored the three with heavy clubs. The soldiers were driven back through the portal. It slammed shut with a thud.

MARK realized that he was holding a lion by the tail. He leaned against the door and kept it closed against the pressure of the soldiers on the other side. But there was no way to secure it. The bolts were on the other side of the door, In a few minutes, as the men on the inside found that the prison was empty, they would all be pushing.

"Back to headquarters!" he ordered. "Walk! Don't attract any attention. I'll hold the door until you get a good start."

"But what of you? They'll get you!"

"Do as I say! If we all make a break for it, they'll trace us back to headquarters. Go quietly and no one will notice you. I'll meet you there."

Reluctantly, the spurious night-watch obeyed. His way was the only solution.

Mark, his back braced against the door, counted the beats of his pulse.

He had to give his party a start sufficient to carry them far enough away that they could not be reached if the soldiers should spread out in a search for them.

At the count of five hundred, indicating that about seven minutes had passed, he suddenly released his pressure from the door, and sped across the courtyard.

The door swung violently open and five men went to their knees. Those in the rear scrambled past them and took up the chase.

But by the time they reached the archway, Mark was a dwindling figure in the distance. At their best speed the soldiers followed. It was a hopeless chase, for in the space of a few blocks the murkiness of the night had swallowed up their quarry, leaving no evidence of his passing.

They scattered, trying to pick up the trail, but finally had to give it up. The search ended at a spot several miles removed from the location of the rebel headquarters, for Mark had purposely led them in the opposite direction. But the real chase was only beginning...

A VIKING ship of the eightieth century, while a model of efficiency for its day, was no speedboat. And so it was that after two weeks of sailing, Nona's ship was still plowing earnestly but sluggishly through the North Sea. It had been a long voyage, especially without the companionship of Mark. Even at his noblest and most irritating, Mark was more fun than any other man. And she missed him. She fretted too; knowing Omega's capacity for getting Mark into trouble, she almost wished he wouldn't find Mark. Omega, you see, was the typical friend of the family, only instead of luring Mark off on disgraceful benders, he was more apt to drag him into perilous crusades to save the world.

Most of Nona's life had been spent so far from the sea that her only knowledge of it had come from books. And the few months that she had traveled on the water had been in Mark's company. Without him, she found she didn't like the sea so very much. It was too unruly, too desolate—and too darned big.

Her mind kept returning to the morning when she had found that he had been washed overboard. She experienced over and over again the wild grief of that moment, and the hopelessness of the subsequent search.

Long days had passed without hearing further from Omega and the strength of her hope was wearing thin. So omnipotent were the powers of Omega that if her husband still lived, the Selenite should have found him long ago. Daily the conviction was becoming stronger in her mind that the visit of Omega had been a figment of her overwrought imagination.

On the fifteenth day land was sighted.

Among the Norsemen there came a stir of excitement. Sven, the captain, climbed the mast and took his place beside the lookout. It was up to him to determine their position. For although they had set their course to bring them to their home port at Stadtland, there was no guarantee that the land sighted was within a hundred miles of that point. Norsemen navigated by instinct—they were very proud of their intuitive sea bearings. But in point of fact, instinct seemed to be merely another name for trial and error.

Sven, who did know every jutting cape and twisting inlet along the coast of his own land, even if he was pretty blank on other coasts, quickly discovered that the ship had made an extraordinarily lucky landfall and lay within one day's northward travel of its destination.

Nona watched listlessly as the crew bent enthusiastic backs to the long oars, aiding the feeble wind that refused to belly the great sail. The sight of land had brought no stir to her breast, in spite of the weary weeks that had made her utterly fed up with the sea.

For although an honored place in Norse society would be hers, by reason of Mark's attainments, the prospect seemed savorless without him to share it.

Of late she had spent most of her time shut in her cabin. The cheerful faces of the crew irked her. They felt none of the doubts that were making her miserable. She had told them, as Omega had suggested, that she had been the recipient of a message from Thor the Thunder God, who had told her that Mark was engaged in fulfilling a mission that would take him several weeks, but that he would return to them when it was accomplished. The Vikings, who revered Mark as the chosen of Thor, found the deception quite believable, and felt no more anxiety for Mark's safety.

This gullibility gave Nona a low opinion of their intelligence, and she found it impossible to endure their light-hearted conversation. She was not by any means certain that she would ever again see the face of her husband.

Another thing that made her visits on deck become shorter as the days went by, was the fact that they made her miss Mark all the more. Invariably he had been with her when she left the cabin. As a pastime he had taught her the use of the axe and short-sword. Garbed in the heavy leather trapping of the Norsemen, to protect them from cuts that might spill too much of their radio-active blood, they would spend hours cutting and slashing at each other, in mock combat.

AT first they had been very careful not to hurt each other, and had used axes and swords with dulled cutting edges. Mark, during this phase of her tuition, had concentrated on the finer points of the art, teaching her to fend off axe slashes with deft parries of the shortsword held in the left hand, and to deliver effective counter-slashes.

And for some time he had dealt his blows lightly, afraid of hurting her. But as her skill increased and it became apparent that she was as proof against injury as he, her strength and agility made him extend himself more and more.

The time soon came when they battled with such skill and fervor that the crew looked on aghast at the apparent intensity of the conflict.