RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

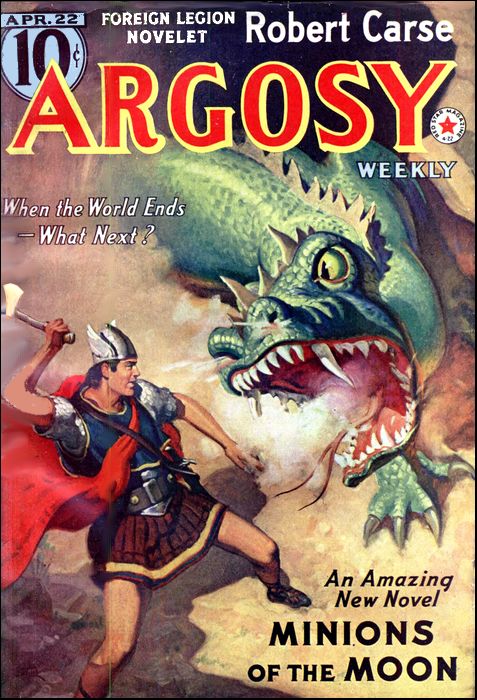

Argosy, 22 April 1939 with first part of "Minions of the Moon"

Mark Nevin was a healthy young man whose appendix, of all prosaic things, led him into unbelievable adventure. For, Mark's doctor had perfected a tremendously powerful anaesthetic, and after sleeping peacefully for twenty-two days, Mark slipped quietly into a state of suspended animation. He didn't wake up until the Year A.D. X2, and the first thing he did was to make friends with the Man on the Moon and Miss America of the Day After Tomorrow.

THERE seemed to be no rhyme or reason to anything, Mark reflected sleepily. In the first place, no such healthy specimen as he had any business with an inflamed vermiform appendix. And certainly there was no sense in old "Chisel-chin," the physician, making him sign a bunch of papers giving authority to administer his new anaesthetic. He could have used it without asking permission, and nobody would have been the wiser. He hadn't asked the consent of the guinea pig he had tried it on in the lab.

Mark chuckled, half awake. It seemed to have worked, he decided, for here he was coming out of it, sans pain—which meant sans appendix.

Something was wrong however, he mused, almost rousing himself to the task of lifting his eyelids. One thing that bothered him was a strong musty odor, one of the few not usually found in a hospital. Another annoyance was the hardness of his bed. He was almost convinced that he had been placed in some dungeon under the hospital, after the operation. Fine way to treat a paying guest!

A sudden and confirming drop of water splashed on his forehead, snapping him completely awake. Somebody would hear about this, he vowed, opening his eyes. An impenetrable blackness was the reward of this effort.

Attempting to rise, he received a jarring thump on the head and fell back. With a surge of panic he realized he was in a coffin! A questing hand had encountered nothing but hard, cold stone on all sides. His own breath, condensing on the lid of the coffin, had caused the drop of water!

Buried alive! He fought to calm himself. The whole thing was probably a dream anyway—a result of the anaesthetic. People had such dreams when under the influence of ether. And besides, they didn't use stone coffins any more...

It had to be a dream. Yet why was he so lucid, and why did he feel that trickle of water advancing, inch by inch, down the side of his face? Sensations were never so clear in dreams.

And how long had he lain there, assuming this were not all a figment of the imagination?

Abruptly he stirred, pressing his elbows against the sides of the coffin. A swirling cloud of dust choked him. The cloth of his shroud had disintegrated, giving rise to the musty odor and the dust which he had disturbed. Centuries must have passed since the operation!

With a burst of frenzy he pressed upward against the lid of his coffin. Quite unexpectedly it raised. A full foot of it extended past the hinges, effectively counterbalancing its great weight. He sat up.

A LARGE, domed, stone vault met his surprised gaze. Two small windows admitted cheerful beams of sunlight. He shielded his eyes, stung by the sudden transition from complete darkness.

Cautiously he climbed from the coffin, half fearful that his legs would crack or collapse under a weight they had not borne for many years. He was surprised and relieved to find that after stretching he seemed as well and strong as before the appendix trouble. A hasty examination disclosed that the incision had healed nicely and left but the thinnest of scars.

And here was a strange situation, Mark decided. Instead of being alive and well, he should be quite defunct. It was only logical to expect his body to be in the same deplorable state as the grave clothes which fell in dust as he moved. His eyes chanced upon the hinged top of the coffin. Whoever had designed that counterbalanced lid had evidently expected it to be lifted from the inside. Most irregular indeed.

A more thorough inspection of his surroundings revealed several additional irregularities. The vault, he noticed, looked more like a locker room than a tomb. Its walls were lined with shiny, stainless-steel cabinets, the doors of which were sealed with wax. There were so many of these that the only bare spaces were those occupied by the two small, paneless windows and a door.

On impulse he strode toward the latter with the idea of seeing what the world looked like outside. He caught himself up short, however, when he saw his reflection in one of the shiny surfaces flanking the door.

"That will never do," he said aloud. "There just might be someone around who objects to nudism. Maybe I had better explore those lockers. Should be some clothes inside if my guess is right."

The sound reverberated hollowly inside the vault, causing him to shiver in spite of the warm breeze which was entering one of the windows. His eyes cast about for some implement with which to dig the hardened wax from the cabinet doors. He found what he sought—an ice pick of stainless steel, which would serve the purpose, nicely-hanging from a hook above one of the cabinets. With this discovery he found another thing he hadn't seen before. The compartment beneath the ice pick was inscribed with the legend:

OPEN THIS ONE FIRST.

Mark obeyed the instructions without delay. Removing the wax turned out to be simple. Long strips of it lifted out of the cracks as he slid the pick around the edges of the door. When the last chunk had been pried loose, he stepped aside as he tugged on the door handle. The precaution was the result of a last-minute thought that he might be greeted by a cloud of the same kind of musty dust that he had stirred up in the coffin. Obviously time had passed—lots of it—since he had been placed in this tomb, and any ordinary fabrics in the cabinet might well be in the same condition as his grave raiment.

HIS apprehensions proved to be groundless, however, for the cabinet contained a phonograph and a large rack full of records. Mark noticed that a record was already on the playing disk so he wound the machine and started it spinning. The welcome voice of old "Chisel-chin" with its nasal twang, blared forth from the horn:

"At the present time, which is twenty-two years after the administration of the drug which placed you in a state of suspended animation, there is no discernible change in your body. The flesh is soft, the blood fluid; and X-ray photographs show all internal organs to be in perfect condition. Following the operation you remained unconscious for more than two weeks—quite sufficient time for the incision to heal—before gradually falling into the state of suspended animation in which your body now lies.

"It is my belief that you may awaken some day, although every attempt of mine to bring you to life has failed. When this may occur there is no way of guessing. A hundred years may pass, or even a thousand. It is with this thought in mind that I have spent the last few years in preparing a resting place for your body which will survive the ravages of time, and stocking it with supplies which will enable you to live under any adverse conditions which may prevail.

"I say this because in recent years the world has gone from one devastating conflict to another, and with no end in sight. There is every possibility that you will awaken to find a world of barbarism, in which mankind has fallen to a low state. This is only a guess, but I have provided you with weapons of the latest design with which to defend yourself.

"There are also hunting rifles using cartridges of small caliber, but far higher in velocity than any in existence in your time. Your marksmanship will render these small bullets as effective as larger ones in the hands of a less experienced person.

"Knowing this, I chose weapons of light caliber because of the smaller space needed to store a large quantity of ammunition. In the cabinets on the far wall, is enough to last a lifetime. It is interchangeable in side-arms and rifles except in the case of the tiny hand-machine-gun you will find. This weapon is to be used at close quarters—less than a hundred feet—and fires slugs smaller in size than the needle in this phonograph. They barely penetrate the skin at full range, but a person hit by one drops instantly. The tips of the needles are coated with a poison which causes instant coma, lasting several hours. Be careful how you handle them.

"There are several cabinets filled with clothing of all kinds, made of the spun-glass fabric which has become popular in recent years. This cloth is durable and not apt to disintegrate with time, being of inorganic origin. Other compartments will reveal a supply of preserved foods in glass jars, quantities of distilled water—just in case you aren't able to find natural water in the vicinity—and tools and implements of varied uses. The records in the rack may furnish you amusement, if you find yourself bored.

"In stocking this vault, I have included everything a man might need to survive in a hostile environment. It is my sincere hope that the nations of the world will settle their difficulties and you will awake in a world of peace and progress, but from present indications it would seem that such is not to be. These cabinets you see about you are an old man's best efforts to atone for a great wrong.

"Goodbye and good luck, my boy."

FOR a long minute, Mark allowed the record to spin, after the voice had ceased, then bestirred himself to turn off the machine.

"You did a good job, doc," he said, addressing the phonograph. "But you forgot to mention just where the heck this tomb is situated. But I guess it doesn't matter. I'll see for myself."

Picking up the ice pick he started to chip away the wax which sealed the next cabinet. He was beginning to get thirsty and hoped to uncover some of the distilled water mentioned by the doctor. The task was barely started when a voice suddenly shouted in his ear: "North America!"

Mark instinctively ducked and whirled to face the speaker. No one was there! He leaned weakly against the cabinet, bathed in cold perspiration, and wondered if his long sleep had affected his brain. Then, when there was no repetition of the astral voice, he resumed his chipping, muttering aloud. Abruptly he was interrupted again.

"Stop mumbling, my fine-feathered corpse!" the voice scolded. " 'Tis not seeming. And besides, it's a nasty way to treat a guest. If I were you I wouldn't let my eyes pop out like that. Somebody might step on them."

Mark, by this time firmly convinced of his own insanity, decided to humor himself.

"No self-respecting corpse would entertain an unattached voice in the privacy of his own tomb," he stated, returning to his task. "You must bring your body when calling. It is one of the first rules of etiquette."

"The nerve of the cub!" the voice complained, talking to itself. "And me an old man when his ancestors were hanging by their tails. All right, you perambulating cadaver, here's a body for you."

MARK resignedly turned around to see what new trick his senses were going to play on him. There, balanced on one foot atop the coffin lid arms outstretched, in a pose that might have done credit to an aesthetic dancer—a slightly cracked one—was a well-muscled masculine figure, gazing with a silly expression at the ceiling. Mark walked around the apparition and examined it critically. No, really; this was going too far.

"Look here. That won't do," he said firmly. "You'll have to get another. That's mine you're wearing now."

The figure floated gently down, seated itself on the edge of the coffin, and assumed the attitude of Rodin's Thinker.

"You humans are the most specialized sort of beings I've ever encountered," he marveled. "I've been studying your race since early Grecian times, and I've never seen two exactly alike. For instance, I remember a man who used to write poetry in a Scotch dialect, and he bemoaned the fact that a person never could see himself as others saw him. And here I give you the opportunity to do that very thing, and you complain."

"Nobody ever saw me in a pose like the one you were just in. You're what I would call a phony facsimile. You look like me, but you don't act like me. Say, don't you have a body of your own?"

"Alas, no," the phantom admitted sadly. "I once had a beautiful body, too. Eight legs, three pairs of the most gracefully undulating tentacles you ever saw, and a chitinous armor which was my special pride and joy."

Mark clucked his tongue in sympathy. "Must have broken your heart to part with it, old man. But it seems to me it must have looked like a spider, if you don't mind my saying so."

Mark's facsimile jumped to his feet, and struck a calculatedly bellicose pose. It muttered angrily and glared. "I don't like the way you said that. Take it back?" he challenged. Then suddenly changing his mind, sat down and fell back into the Thinker attitude. "As a matter of fact, my race did resemble the arachnids, though we had none of their objectionable habits. Then too, we had six tentacles, far more efficient members than anything owned by a spider—or a man either, for that matter. We could do things a man wouldn't even attempt with his silly hands and their stiff-jointed fingers."

Now it was Mark's turn to be angry. "Don't be absurd. If you ever saw anybody play a piano, you wouldn't talk about stiff fingers. Why, I've seen—oh, I don't know why I'm arguing with you. You're only a figment of my imagination. I'm going to find something to drink."

The embodied apparition again leaped to his feet, glaring at Mark, who unconcernedly resumed his wax-chipping. Ignored, Mark II began pacing in circles around the coffin and muttering to himself.

"What a vanity," he fumed. "Me, a figment of his imagination. It's more likely he's a figment of my imagination. I'm crazier than he is. Always have been." He stopped to address Mark the first in a patiently instructive tone. "You're digging at the wrong door if you want water. That one is full of preserved fruit. The next cabinet has corn and beans. The one on the far right contains water. So if you think I'm an hallucination, see if I'm not right."

Mark looked at his replica in astonishment. "You mean you want me to prove that you're not a mere fragment of a temporarily disordered imagination? But if I do, that means you must be a specter or a ghost, and I won't believe that either."

"I don't care what you believe," Mark said sulkily.

The last of the wax was loosened and he opened the door. Shelf upon shelf covered with jars of preserved fruit met his gaze. Mark was astonished, to say the least, but he contrived to hide it from his visitor by quietly closing the door and starting to work on the door at the extreme right.

"For a mere hallucination," he remarked, chipping away with a great show of nonchalance, "you do seem remarkably accurate in your predictions."

"I notice you're working on the one with the water," Mark said, sarcastically.

AND water it was. Mark was not really surprised this time. After finding the fruit he had realized that this nightmarish creature knew what he was talking about. There were too many other things that might have been in that cabinet to attribute the phantom's wisdom to guesswork. The phantom knew; but just how he knew was a mystery yet to be solved.

Mark dug the wax stopper out of a three-gallon bottle and let a quantity of refreshing, but flat-tasting water trickle down his throat. Then with the remainder he washed the clinging dust from his body, while the facsimile looked on with an expression of amusement on his—or rather Mark's—face.

"What are you going to dry yourself with?" he inquired loftily.

Mark looked about him helplessly, then brightened up. "If you will stop showing off and tell me which locker my clothes are in, I'll find something."

"Not necessary," Mark said, reaching out his hand. In it appeared a long, fuzzy, bath towel. Mark controlled an urge to gape, and took the towel.

"Thanks," he said, applying the creation, which seemed to absorb water quite as well as one manufactured in the usual way. "You'll have to teach me that trick sometime. But right now I wish you'd tell me just what you are, and why you insist on haunting me."

The phantom hopped up and down in fury. Most of the time his feet didn't touch the ground, but that didn't seem to bother him, not in the least.

"Insults!" he howled. "Nothing but insults! I'm not a ghost. I refuse to be considered a ghost!"

Then, as if he took perverse pleasure in self-contradiction, his flesh slowly became transparent and finally melted away, leaving nothing but the bony framework, which proceeded to drape itself in the familiar attitude, atop the coffin lid.

"Don't do that," Mark begged. "It's—it's disgusting."

"I shall do it if I like," the skeleton answered, snappishly cracking a fleshless knuckle. "It's cooler."

Mark sighed resignedly and sat down on the far end of the coffin, determined not to be surprised at anything that might happen from now on. He noted with interest that the skeleton had a neatly-healed break in a collar bone. The visitor surely was carrying out the duplication to ghoulish perfection. Mark remembered receiving that break in the last quarter of a college football game during his senior year, and was pleased to see that it had knit so well.

"It's a long, sad story," began the skeleton, in a hollow voice. "My race was born, and lived out its life on the Earth's satellite. It is remarkable, when you think of it, that a race could evolve far enough to reach a high state of development on that little planet. Gravitation being slight, the Moon lost its atmosphere at a fast rate. The entire habitable life of the planet lasted hardly longer than one geological age of the Earth.

"My people advanced rapidly, I suppose, because we worked as a unit. No dissension; no individual ambitions. Every one of us strived for the advancement of the race, not for his own betterment.

"But things happened rapidly on my world. Eventually we had to burrow underground and establish great sealed caverns in which life could continue independently of the fast failing air supply on the surface.

"BUT just as my race had evolved rapidly, it declined also at a fast pace. The time came when, out of the vast millions which once roamed the planet, there were only a few dozens of us left; and these few had almost completely lost the power to reproduce.

"I was one of these, in fact one of the last to be born. At an early age I showed signs of being a little—well—" the skeleton smirked modestly—"unique. I saw no sense in co-operating with the others in finding a way to increase our reproductive capacity. It was my contention that a million ordinary people were of no more use than a few high-grade specimens. Quantity was not to be more desired than quality. My aim was to find a way to preserve the lines of the few who remained.

"Nobody agreed with me, of course, so I had to work alone, solving the problem without aid." His tone now became happily martyrish. "I devised a radioactive fluid in which a brain could live, immersed, forever. For several million years, anyway. The body would have to be abandoned, of course. The others finally accepted my idea, inasmuch as they had failed to reach their own goal.

"Unfortunately it didn't work out so well in their cases. They had absolutely no sense of humor. Their lives had always been so serious that when they were freed from the eternal struggle for existence, they were unable to satisfy themselves with abstract thought. The sustaining necessity to solve vital problems had been removed.

"For a time they occupied themselves by inventing imaginary problems, and then joining in finding the solutions. But this was just silly and eventually they began to fall into periodic stupors, each of longer duration, until finally their brains ceased to function altogether. At least there has been no thought radiation from any of them for over fifty thousand years."

"They still exist then?" queried Mark.

"Oh yes. They can't die, in a physical sense, as long as they remain immersed in the fluid. They still lie in their containers in the interior of the Moon, protected from any possible harm by a spherical wall of force which we created as a stasis in the fabric of space shortly after we abandoned our bodies.

"That was the only project that I ever joined the others in accomplishing. It was a great idea. The whole planet could disintegrate without harming the brain containers. The stasis can only be dissolved by the agency which created it—the combined thought force of many powerful brains!

"I suppose I may as well believe you," Mark sighed. "Here you are, sitting on my coffin, looking like the breakup of a hard winter, and your brain really resides on the Moon. But I must say I wish you'd just quietly passed out the way your pals did, instead of going about shedding sweetness and light in people's tombs—particularly mine. I don't suppose I could persuade you to go away."

THE skeleton ignored him. "The main point in which I differed from my contemporaries lay in the fact that I had a sense of humor," the skeleton went on. "Maybe you've noticed. I'm a psychological mutant. My mind was never geared to the eternal struggle for existence, as theirs were. I could never believe that just living on was of much importance. A race of beings content to inhabit a small satellite of a minor planet of a fourth-rate sun, struck me as being pretty small potatoes. To coin a phrase." The skeleton giggled.

"After we had forsaken our bodies," he went on, "and our brains had taken up residence inside our wall of force, I couldn't join the others in their pointless games. I had to have something to amuse me. So naturally I went exploring. Not physically, of course. My race had mastered thought long before I was born. By projecting my ego where I wished, I was able to observe life on the other worlds, some of them far outside the solar system."

"Wait a minute," interrupted Mark. "Am I to understand you are really doing your thinking from the brain on the Moon, and these creations of yours—the body you just had, the awful thing you're wearing now, and the towel—are mere hypnotic suggestions which you have impressed upon my brain by means of projected thought waves?"

"Nothing of the sort," the skeleton snapped, "You couldn't dry yourself with a hypnotic suggestion."

Mark pondered this for a moment. "No," he admitted, "but I could imagine I had, if you hypnotized me into thinking so."

"And catch an imaginary cold, I suppose," remarked the skeleton sarcastically. "You have the wrong idea. I wouldn't hoax anybody into seeing things that don't exist. It's hard enough to believe the things that do exist. That towel is just as real as any matter is. So was the copy of your body, and so is this skeleton.

"Of course matter isn't so very real, at that. Matter is only a function of space. So is energy. Space is the only real thing. Energy—regardless of its form—is merely a wave in space caused by some action of matter. And matter is merely a concentration of space-in-motion, the motion being caused by energy. It's all very simple."

"Yes, of course," agreed Mark. "Only I don't understand it."

"You will when you've lived a few more thousands of years. As for doing my thinking from the Moon, I don't. When I choose to go exploring, my intelligence leaves the brain and travels instantaneously to the place I wish to go. Then, if I want a body, I merely create one from the energy waves which abound in space. But no matter what form of body I may acquire, I always retain the senses and powers with which a free intelligence is endowed."

"How convenient," Mark commented. "But if you can do all this independent of your brain, it wouldn't matter much if your brain were destroyed, would it?"

Rattling nimbly, the skeleton jumped to its feet. Mark winced.

"Gracious me!" the skeleton exclaimed. "I never thought of that. Here I've been jumping in and out of that brain for thousands of years—and never considered that I might not need the pesky thing at all. I'll have to think this over. Goodbye for now!"

ABRUPTLY the voice ceased and as it did the skeleton collapsed in an untidy heap on the floor. Mark sensed immediately, with a certain feeling of loneliness, that the intelligence had left for parts unknown. The pile of bones proved that the brain's creations were of real matter and only disappeared when he purposely destroyed them.

"Well," Mark thought, "he left me with a set of spare bones, at any rate."

A rush of memories—of people he had known, places that were familiar to him, and things he had held dear—came to trouble him as he found himself alone once more with his thoughts. He was glad now that he had been pretty much alone during that earlier, far-off part of lifetime. There was no wife to mourn, no sweetheart. That would have made it harder. It wouldn't be an easy thing to suddenly realize that a girl—the girl whom you had last seen alive and lovely and young was now nothing but a crumble of dust, dead for hundreds, perhaps thousands of years.

Gloomily Mark attacked the wax on another of the cabinet doors. Finishing this one, he went on to the next and the next, trying by means of sheer activity to close his mind to thoughts of a world long dead.

Before he had removed the wax from the last of the doors, he was wondering in what part of the world his tomb was, and how many centuries had passed since the operation... "Did I ever tell you about my operation?" he could ask. "Well, it was about four thousand years ago..." A fine thing.

His visitor had hinted that he was still in North America. That was indefinite but he supposed it didn't matter. Everything would be different anyway. The phantom had claimed that Mark would understand the complex nature of space, matter, and energy when he had "lived a few more thousands of years." That might imply that he had already lived a few thousands of years. On the other hand if he were to assume that it did, he must also assume that the specter was speaking seriously and really meant that he had thousands more years to live. Which, of course, was pure rot.

It obviously wouldn't do to put too much faith in anything the creature had said, he decided, inasmuch as it had freely admitted being more or less crazy. "Just a goofy ghost," he tried to tell himself, firmly averting his eyes from that messy pile of ribs, tibia, clavicles, vertebrae and bony etcetera on the floor.

A GLANCE through one of the small windows revealed that the nearby country was heavily wooded and the ground covered with dense underbrush. This decided him on what to wear, and he set about to select it. The first three cabinets he examined contained ordinary street apparel. The old doctor had evidently held out some hope that the old civilization might continue after the wars were over.

But the next five lockers indicated that this hope had been none too strong, for they were stuffed with clothing designed for outdoor life. Two more of the cabinets were filled with underwear and another contained shoes and boots. In a short time Mark was dressed to cope with the surrounding forest, and equipped with weapons to take care of any wild life he might encounter.

In addition to the highly efficient automatic pistol, he carried a stainless-steel hand-axe fastened to his belt. The underbrush would make this a valuable tool. A small pocket compass should prevent getting lost, and the tiny, needle-throwing machine-gun nestling beside it in a jacket pocket might come in handy in dealing with any hostile humans he might meet in his travels.

Mark really didn't expect to find the world greatly changed, but he certainly wasn't taking any chances. For all he knew his period of suspended animation might have lasted only a hundred years or so. It was hard to say just how long it might have taken for his grave-clothes to disintegrate. The clothing he was now wearing showed no signs of age, but then of course he had the doctor's story that they were made of some new fabric of glass, although they certainly didn't look it. As far as the incident of the spook was concerned, he wasn't at all sure now that he hadn't dreamed up the whole upsetting incident. He fervently prayed that it was so.

Considering everything he decided it wouldn't be at all unlikely that he would find a civilized community a few hours' walk from the vault.

The doctor's fear that the wars going on at the time of his record, would leave the world devastated and civilization wrecked, were very likely exaggerated. He had heard the same fears expressed many times before, and nothing of the kind had happened.

As a last preparation before venturing forth he took a long swig from the bottle of insipid water. He had no intention of returning to the tomb until he had done some extensive exploring in the neighborhood, and there might not be any streams handy. As he returned the bottle to the cabinet his eyes passed fleetingly over the compartments containing the food supplies. He wondered if he shouldn't eat something before he left, but decided he wasn't particularly hungry.

The forest was an impenetrable tangle of trees in all stages of growth. Mark noticed that the underbrush wasn't nearly as thick as he had supposed. The window, he remembered, had shown him only a small view and in that direction there were several dense clumps of foliage.

He was about to replace the hand-axe when he changed his mind and tucked it back in its belt-strap. It would be worth carrying for use as a trail marker.

The sun, although he couldn't see it through the tall trees, seemed to be southeasterly, which indicated that it was before noon. This left him plenty of time to explore before dark drove him to shelter. Without any particular reason, for one direction is as good as another when you have no idea where you are, he decided to follow Mr. Greeley's advice.

A FEW hundred years ago—or was it a few thousand—Mark had possessed a unique propensity for getting into trouble. His small inheritance had made it possible for him to get along comfortably without any sort of salary. And he had found it impossible to live a routine existence. Athletics had provided a suitable outlet for the surplus energy; but he has also been cursed with an overwhelming curiosity concerning almost everything on earth. As a consequence he had often poked his handsome nose into places where people displayed alarming readiness to bash it flat. This instinct had apparently survived the years of suspended animation, for westward was the one way he could have chosen that would lead him into trouble in practically unlimited amounts.

This fact was not to come to light until Mark had covered quite a few miles. Indeed it seemed as he trudged along in the forest that never in his conscious lifetime had he encountered a more peaceful portion of the earth.

Sunlight filtered, here and there, through the dense, leafy canopy overhead and made bright patches on the ground, lending cheer to the grayish twilight which pervaded the lower reaches of this vast woodland. The songs of unseen birds among the branches, and the occasional squirrel who sat back on its haunches to gaze in frank curiosity, only to dart suddenly up the bole of a tree at his approach, combined to lull Mark into a dreamy—and utterly misguided—sense of security.

So rapt was he in his lyrical contemplation of nature's beauty that he went on blissfully for quite a distance before he remembered that he had completely neglected to mark the trees to indicate his trail.

He stopped, half minded to retrace his steps, when it occurred to him that he had been walking in a straight line since the last mark, and it should be easy to bridge the gap on his return. To make sure, he marked several trees close together in a line in the same direction, then continued on, satisfied. The precaution was entirely useless. But he didn't find that out for quite a while. In fact if he could have foreseen what lay ahead, it is likely that even Mark would have locked himself in the tomb and refused to budge a step.

Merrily whistling a tune which had enjoyed tiresome popularity at the time of his operation, Mark's springy tread carried him momentarily closer to disaster in one of its milder forms.

He was wondering if it might not be a good idea to climb one of the higher trees and get a bird's-eye view of the surrounding country. For all he knew his path might lead him endlessly through the woods, while a short distance to the right or left might lie the edge of the forest. He was on the point of climbing a likely looking tree when he was startled by a raucous yell and the sudden appearance of a score of half-naked, black-bearded men. Most of them were brandishing crude spears, but some of them were armed with knobby clubs.

With a draw which would have done credit to Wild Bill Hickok, Mark snapped his pistol into action.

The nearest of the attackers let fly with his spear just as the automatic left its holster. Mark dodged and fired. The savage collapsed like a puppet when the strings are dropped. But in the next instant Mark was felled by a club which struck him behind the knees. Firing wildly, he hit two others before being pinned helpless beneath the weight of a half-dozen vile-smelling bodies. He struggled for a moment, but he stopped when he found he wasn't getting anywhere.

THE leader, an unkempt hulk of a man, placed the point of his stone-tipped spear at Mark's throat and jabbered to the others to release him and form a circle about him. Lying flat, with the spear-point teasing his Adam's apple, and a dozen more aimed in his general direction, Mark decided that he was outnumbered. The savages evidently didn't intend to kill him, or they certainly would have done it by this time. That being the case, he might as well wait for a more auspicious moment to get away. The little gun in his pocket, with its load of several hundred poisoned needles, would take care of this nicely—if they failed to search him.

When the leader saw that his captive was going to be philosophic about the matter, he withdrew his weapon and motioned Mark to get up. The pack drew closer to inspect the specimen they had bagged, but the leader growled something and they stepped back, muttering in protest.

A series of moans and groans from a point outside the circle gave evidence that one of the victims of the pistol was still alive, but the savages paid no heed to their disabled comrade.

The leader's eye was caught by the shiny, stainless steel axe, and he yanked it from its strap, hefted it, and placed it in the band at the top of the short skirtlike garment which was his only attire.

Mark submitted with the mental reservation that when the time came he would take it back with interest—in the form of a piece of the thief's hide.

The gun had disappeared. Mark remembered it had been knocked from his hand when the pack had jumped him, but it didn't seem to be anywhere in sight now. He supposed one of his attackers had purloined it before the chief had had a chance to see it. He piously hoped the unwashed devil would shoot himself with it.

The leader grunted a series of commands to his crew and they prepared to march off through the forest in a direction to the left of Mark's former course. Mark gave a relieved sigh as he realized that they weren't going to search him, and his tiny gun was safe.

He decided that his captors were unfamiliar with any wearing apparel more complicated than the crude loincloths they wore themselves. It was unlikely that they would think of the possibility that clothes might conceal weapons.

Two of the savages walked behind him, prodding his spine with their spears; while the rest of them gathered in front and on either side.

The leader looked at the two motionless figures of the men killed by Mark's bullets, saw they were dead, and turned to the wounded man. The man stopped his groaning and looked up with eyes filled with a sort of fearful pleading. The leader prodded him with a foot and grunted a command. The wounded one lifted a hand and answered in a whine. The chiefs next act was to skewer the man neatly with his spear. He roughly withdrew it and ordered the party on its way, ignoring the final thrashings of the victim of his cold brutality.

SEETHING inwardly, but unable to do anything about it, Mark trudged along to the accompaniment of an occasional prod from the spearmen behind him. They seemed to be having a lot of good, innocent fun, but fortunately their spear-tips were not very sharp and the jabs were seldom delivered with sufficient force to pierce the skin. Mark gave no sign that he so much as felt them—he remembered his James Fennimore Cooper and the savage's reputed admiration for stoicism—but this failed to deter the torturers in the least.

They were evidently carrying on just for their own amusement and didn't seem to care how Mark felt about it, one way or the other. As a matter of fact, the pain wasn't so great and after a while he found it possible to ignore it completely and think of other things.

There was, of course, the language to consider. What he had heard of it seemed to consist of a series of guttural, grunting sounds, wholly unlike anything in his experience. Certainly it was not any dialect of English, Spanish or French.

Of course there were some pretty primitive Indian tongues, but these lads were certainly not Indians, even if they obviously were savages. They were altogether too hairy. They looked more like gorillas, he noticed, except that a gorilla wasn't so ugly.

No, they certainly weren't Indians; so they must be some kind of reverted white men; and their language, therefore, must be the degenerate remnant of some white man's tongue. Possibly even English.

This was disheartening, since it plainly indicated that he had been in the tomb for a lot more than a mere hundred years or so. And if one group of humans had chased themselves back to the Stone Age, all mankind might very well be at the same level. Little Mark, he thought glumly, and His Time Machine. Little Mark and The Shape, for Pete's sake, of Things to Come...

Their weapons, he saw, were even more primitive than those of the most backward peoples of his own time. Stone-tipped spears and rough-hewn clubs. No metal—not even bows and arrows. The Australian bushmen had been better equipped. They at least had the boomerang, which was a pretty scientific instrument; and they were accepted as the most primitive of the earth's dwellers. Well, it seemed they had lost their claim to distinction. Meet the new champs.

This thought, and a few others that suddenly popped into his head, provided him with something that in a sufficiently murky atmosphere might pass for a purpose in life. This was how he looked at it. First: that at the end of any war or other catastrophe which might disrupt civilization, certain groups—aggregating millions of people, perhaps—would survive, separated from each other by distances not easily spanned, due to failure of ordinary means of transportation and communication. These groups would be faced with a flock of problems incident to continued survival. Some sort of government would be needed; food supplies must be provided, and clothing and housing against the inevitable approach of winter.

Each group would have so many things to do—things of immediate importance to its own continued existence—that no time could be wasted trying to contact the others. Another deterrent to communication would be the fact that in each community the leader, or clique of leaders, would be too jealous of the power gained to risk it by inviting overtures from other groups. This had happened after the fall of the Roman Empire and had very likely, happened again.

Each of these groups would thrive in a manner dependent upon the facilities at its disposal, the leadership available and the type of people to compose it. These factors would vary to a great degree in different groups, and in some cases civilization would not lose much, while in others retrogression would take place immediately and speedily. Mark was of the opinion that he had fallen into the hands of one of the latter, one which had slipped about as far as man could slip.

His hope was that somewhere there was a people who retained the culture which this bunch had lost, and he intended to start searching for them as soon as he made his escape.

The second thought that cheered him was that even if the first thought was wrong and the world was completely populated with people like the ones he was mixed up with now, he would at least have a lot of fun looking for the other kind, even if they didn't exist. For Mark had always found the hunt more exciting than the kill.

THEY eventually emerged from the forest and started across a broad plain. The destination of his captors was now in sight, a mile or two from the edge of the wood. Here lay a scattered group of mud huts, baking in the heat of the midday sun. There were about a hundred of them, a disordered cluster of decidedly unwholesome appearance.

Mark decided immediately that his visit was going to be of very short duration. As they drew closer, a vagrant breeze carried to them a tasty bouquet of decayed garbage and close-packed humanity.

The proddings of the two at Mark's back became more insistent, and he obligingly increased his pace. The whole pack seemed anxious to arrive home as soon as possible to show him off. A clamor arose from the huddle of dwellings—Mark could not bring himself to think of them as houses—and a straggling crowd hurried to meet the conquering heroes. From that point on, Mark's escort closed its ranks, completely blocking him. They seemed suddenly intent on shielding him from the curious gaze of the horde.

At least that is the way he interpreted their action, and he didn't like it a bit. Not that he particularly wished to be admired, but when one considers that his captors had probably not had one bath between them in all their odorous lives, it is understandable that he preferred them not to crowd so close. As a matter of fact, he had guessed wrongly as to the meaning of their maneuver. They were merely protecting him from the exuberant spirits of the good villagers, who probably would have torn every piece of clothing from him and perhaps a bit of flesh as well.

In a few minutes Mark found himself thrust through the gate of a circular enclosure of ten-foot pikes, set a few inches apart, and secured from further separation by strands of tough vines. The gate was slammed shut and fastened by a simple latch which he could have opened by simply reaching hand through the pikes, except that a guard was stationed to see that he didn't.

For a few minutes the hut-dwellers fought with the guard to open the gate and get in, but seeing that he had the situation well in hand they eventually desisted. This conclusion wasn't reached, however, until several victims of the guard's club lay unconscious on the ground. Paying no attention to these casualties, the crowd proceeded to relieve its high spirits by throwing garbage, stones and clods of dirt at the captive.

They soon tired, however, for the pikes were set too close together to make this sport worthwhile. A good proportion of the stones thrown bounced back and hit others in the crowd, which started a few minor riots, much to Mark's savage delight. Mark was really surprised at the amount of venom these brutes uncovered in him.

He gave so much attention to the crowd that it wasn't until it had quieted down that he noticed there was another tiny enclosure, similar to his own, just a few paces to the left.

His audience was milling about so much that it was some time before he was able to see whether or not it was occupied. None of the quaint villagers were molesting the other corral and for that reason he supposed it was empty. Of course, it might also be that the enclosure had an occupant who had been there for so long that he had lost popular appeal. His fickle public had deserted him in favor of a newer attraction—Mark—who was thinking he should have been in vaudeville.

FINALLY the crowd parted and he obtained an unobstructed view of the other pen. For a second he caught his breath, speechless. There was an occupant, all right, and it wasn't a man. His fellow prisoner, as far as he could see through the close-set pikes, was a woman, and a decidedly lovely one at that.

It might be mentioned at this point that Mark had never been anything that could be thought of as a ladies' man. And since his last brush with a member of the opposite sex, in the course of which he had been both annoyed and thoroughly disillusioned, he had been exceptionally wary and distrustful of all womankind. So when he saw this lovely creature regarding him steadily with one clear, brown eye—the other being behind a pike—there was a long, breathless instant in which he could do no more than stare dumbly back at her. It was during this endless instant that one of the fun-loving citizens managed to toss a clod of earth through the bars with commendable aim. The missile landed athwart Mark's nearer ear, sprinkling clumps of dirt inside his shirt.

"Lovely people," he finally remarked, wondering if the vision would grunt in reply. He wanted to tell her swiftly not to reply. Gibberish from those lips would have been sacrilege.

"Yes, aren't they?" she returned, in accents clear and unmistakably English. "You should feel honored. They've deserted me completely."

"Oh!" blurted Mark, "I didn't expect you to speak English."

The lady straightened up, indignantly. "You didn't think I might be one of those?" She inquired haughtily.

Mark glanced confusedly at some of the unclad slatterns who made up a good proportion of the crowd which was now listening open-mouthed to the conversation of the prisoners.

"No, no," he hastened to assure her. "It's just that I've been asleep for a few thousand years, and I didn't think the language had survived that long."

She looked at him quizzically for a minute before replying. "You have been asleep for a few thousand years," she repeated. "How interesting. I hope I'm not intruding."

With this observation the young lady turned her back and gazed absorbedly through the opposite side of her prison. She quite evidently regarded Mark as being an unmitigated liar slightly on the boorish side. Ordinarily Mark would have been glad to see the end of the conversation, even on that basis, but this time he chose to deceive himself with the thought that here was his only chance to learn something about this new world, and therefore he must convince her that he was all right.

"Please forget I said that," he begged. "It's perfectly true but we'll drop it if it bothers you. I hope I'm not stealing your thunder."

She turned around. "You certainly are," she said. "Although when I was captured this morning, most of the creatures were out in the fields. But those who were home managed to make quite a turnout. Look at me, would you?"

MARK would, gladly. The girl's clothing covered slightly less than one-fifth of her well-formed anatomy, and consisted mainly of an abbreviated pair of shorts, and something eye-fillingly narrow that seemed to be a cross between a shirt and a brassiere. It covered her shoulders and had sleeves three inches in length which made it resemble a coat—but it fell justifiably short of concealing the lower ribs. The material was satinlike.

Mark gaped as the girl showed him those portions of her skin which had been bruised, soiled, and otherwise damaged by the missiles of the savages. His best offering in sympathy was a dry clucking of his tongue.

"Of course," the girl remarked, "these brutes probably do that to make their victims more tender."

"Tender?"

"Yes. I suppose they will give you another treatment. You will probably be too tough to suit them."

Mark was silent for a minute trying to figure out this last. "I'm a bit dense," he admitted, "but do I gather that these people intend to eat us?"

The girl looked surprised. "Of course," she answered. "Didn't you know? They always eat captives. It's part of their charm."

Mark suddenly felt weak in the knees. This was more than he had bargained for. Something would have to be done, he decided, and groped for the needle-gun inside his jacket pocket.

"You don't seem very concerned," he observed.

"Oh, but I am," she insisted. "I'm so scared I'm beginning to jell."

"You don't look it," Mark accused.

"Naturally not. From childhood my people are trained to be stoical. You see, it frequently happens that one of us gets captured by these wandering tribes. And that nearly always means torture. A person who shows no fear or pain gives very little entertainment for the torturers. So they soon get tired and kill him, which is a boon for the captive."

"You aren't very fussy about boons, are you? Wouldn't it be a lot more sense to build a wall around your city and thus prevent these captures?"

"Our city has a wall," she returned. "But our farm and pasture lands are too big to go inside it. And the cannibals are too clever to attack an armed body of our citizens. They always pounce on just one or two and make off before a rescue can be attempted."

MARK was aware that as they talked the mob of savages gradually lost interest and drifted away. There were now only a few remaining. He suddenly realized that no more likely moment to escape was apt to turn up. His guard was absently scratching himself sleepily and watching two boys engaged in a wrestling match. The other guard was, just as sleepily, contemplating the beauties of his prisoner.

This effrontery, Mark decided, entitled him to be the first to sample a few of the needles. He put the idea promptly into action. He fired. The guard stiffened, looked startled, and crumpled to the ground. The girl, without so much as batting an eye, reached a hand through the pikes to unfasten the latch, while Mark turned and treated his own guard to a short burst from the gun.

This one stiffened also, but declined to fall. Instead he looked reproachfully at his attacker and calmly unlatched the gate.

"To think," he said sadly, "that after all I've done for you, You'd try to shoot me. Shame on you!"

"The Goofy Ghost!" Marked exclaimed, and the guard looked more reproachful than ever. He didn't like to be considered supernatural.

Mark noticed that the girl was having trouble opening the gate against the dead weight of the fallen guard. As he went to help her the erstwhile apparition strode in front of him, calmly picked up the obstruction and tossed it, without effort, through the side of the nearest house. With a loud crash the flimsy, baked-clay wall fell to pieces, preceding the other wall and the roof by only an instant.

"Now you've done it," Mark groaned. "That'll raise the whole colony. Let's get out of here!"

His prediction came true before the noise of the collapsing dwelling had died out. Already men were running from the nearer huts, and the two boys who had been enemies only a moment before were now united in screaming and pointing toward them as they fled.

WITH gleeful strokes the phantom plied his club in a sincere determined effort to decapitate as many of the townsmen as possible. Any that managed to escape his gleeful swings were taken care of by the needlegun in Mark's steady hand.

The girl ran nimbly between them.

Of all the spears which were hastily thrown at them, only two registered hits. One of these was tossed at pointblank range toward the phantom's borrowed body. It shattered itself on his club and a moment later the thrower fell before that same club. The other spear, however, entered the phantom's back and stayed there, swinging to and fro, unheeded. Mark noted this fact idly, thinking it scarcely worthy of comment.

Once a burly figure rounded one of the dwellings and leaped directly in their path. He was no more than a yard away when he appeared. Mark's pulse gave a jump as he caught the flash of his own axe descending toward his head! In a split second, he discarded the thought of using the needle gun. No drug could act quickly enough to stop that streak of razor-keen steel. With a quick sidestep to the right, he put all his weight into a crushing left uppercut. The axe dropped as its wielder fell unconscious. Mark retrieved it, recovered his stride just in time to direct a stream of needles into another of the brutes.

The edge of the settlement was reached without further mishap, and they continued trotting toward the forest. Occasionally the phantom's feet would leave the ground and he would float along for a few yards before coming down and running in a plausible manner. At these times, Mark noticed, the girl's face lost its usual placid expression. Her training had prepared her for no such antics as these.

Once inside the wood they stopped and watched the settlement for signs of pursuit, but evidently the barbarians wanted no more to do with these unusual people.

"I tried out your suggestion," remarked the phantom, allowing the punctured body to fall to the ground and speaking from a point in the air where the head had been.

The young lady, who had seated herself comfortably, looked around, wide-eyed, but said nothing.

"You mean you destroyed your brain?"

"Yes, completely. It was a bit of a gamble, but I had to know."

Mark was silent for a moment. It seemed this goofy ghost had an awful wad of courage to risk extinction just to prove something that didn't need proving at all.

"Suppose you take another body now," he suggested, "and tell us how you happened to be occupying that other one."

With an abruptness that astonished even Mark, who was becoming used to such things, the phantom appeared in a brand new body, this one moderately handsome.

"You didn't have to try to look like an Adonis," Mark complained.

"So that's the way it is?" said the Adonis sagely, with a glance at the girl.

"Not exactly," Mark said nervously. "But just the same you might play fair, you know."

"Well, maybe this will suit you better." And so saying the handsome physique began to age before their eyes. It was an infirm and decrepit Adonis who grinned at them now.

"All right. And stay that way," said Mark. "And now suppose you explain yourself. And while I think of it, suppose you give us a name. I'm tired thinking of you as the Goofy Ghost."

"You don't for a moment imagine I like to be thought of that way? It's insulting, that's what it is," declared the apparition in a quavering voice. "Suppose you call me 'Omega.' You couldn't say my real name. Wrong kind of vocal apparatus. And incidentally you two should really be introduced. Allow me to present Nona Barr, who recently ran away from home rather than marry a certain gentleman. Nona, I think you will find Mark Nevin a pleasant fellow, even if he is about six thousand years older than you."

NONA acknowledged the introduction with a little curtsy, and then for some reason incomprehensible to Mark, blushed a deep crimson. He grinned, hoping to put her at ease, but could think of nothing to add to his, "How do you do?" Nona, to cover her confusion, turned in wonderment to Omega.

"How did you know my name and that I ran away from home?"

"Been watching you since you were born. I knew the Eugenics Council had made another mistake when your mother and dad were married. You were bound to have that spark of independence that they have been so diligent in exterminating. So I watched you with interest, saw the spark flare up half a dozen times, and finally break into flame when they tried to marry you to that nincompoop."

At this point Mark interrupted with: "She can't understand that you have watched her all her life without knowing what sort of person you are. And while you're telling her that suppose you explain how I was asleep for six thousand years. She thought I was lying when I told her."

Omega thoughtfully removed the remains of his former body, explaining that he had acquired that lump of human clay by the simple expedient of copying one of those whom Mark had killed during his capture. He had then joined the marching captors, telling them that he had not been killed, but knocked out. As for being placed as Mark's guard, that had been a matter for volunteers and he had been the only one to offer.

Omega seemed to be wound up, for after exhausting the subjects of his own and Mark's history, he went on to describe to Mark the civilization of which Nona had been a member.

It was a socialistic sort of affair with certain governmental powers vested in various councils, These councils had the final authority in matters falling within their jurisdiction. Thus it happened that when the Eugenics Council had decided that a mate for Nona must have certain characteristics—known as "gene determinants"—and found that there was but one man who filled the bill, there was no choice for her but to take that man or run away.

"The idea itself is a good one," Omega stated, "if they had been intelligent enough to work it out properly. The rapid progress of my own civilization was partly due to careful selection. Supermen could be created in the same manner. But this council invariably misses the important characteristics and instead fosters such points as stoicism—which is commendable, but not particularly important—and the ability to knuckle down to superiors—which makes for unified action, but stifles independent thought. Taken by and large they have used eugenics for selfish purposes rather than for scientific progress.

"And don't get any funny ideas, Mark. Your genes wouldn't suit the council, either. They wouldn't even admit you. You'll just have to find somewhere else to go."

MARK glared savagely at the ground, and wished Omega had a little self-restraint. If there was any courting to be done, he'd do it himself, without any suggestions from an antiquated. Which reminded him that he was six thousand years old himself.

"And now that we are acquainted with each other," Omega was saying, "what's next on the program?"

"I'm hungry," Nona declared, after the fashion of women from time immemorial.

"Just a minute, and I'll see what's in the kitchen," Omega said, groaning as he hobbled toward a nearby patriarch of the forest.

"Where is he going?" inquired Nona. "He's a dreadful old man."

"I'm not going to try to predict anything he might do. But a good guess would be that he is going to step out from behind that tree with an armful of groceries. He's full of surprises."

But an armful of groceries was much beneath Omega's abilities. In a few minutes he came shuffling forth, carrying a table, heavily laden with food. Wisps of steam curled up from under silver covers and fragrant odors rose into the air. Two chairs floated madly through the air behind him.

"Don't show any sign of surprise," whispered Mark. "He's vain enough now."

Nona hastily composed her face and calmly sat down in a chair that Mark captured for her.

"Thank you," she said sweetly.

Omega looked searchingly at her, then at Mark, who was trying to hide a grin. "So that's it!" he exclaimed. "Spoiling my fun. We'll see about that."

Mark lifted the covers, one by one, and disclosed a series of dishes designed to whet the most jaded of appetites. Although he, strangely, had not been the least bit hungry since his awakening, the sight and aroma of this food made him ravenous.

"Now if you people will excuse me for a few minutes," Omega said, his body gradually fading as he spoke, "there is a little matter I must attend to."

THAT should have warned Mark, but when the vanishing act was completed he forgot about his benefactor, and fell to helping Nona. Except for being slightly aggressive, the girl's table manners were reassuringly correct. Mark's first mouthful—a forkful of tender roast beef—revealed to him what Omega had in mind when he had said, "We'll see about that." The beef tasted like stewed onions! And Mark hated stewed onions.

A glance at Nona told him that she had noticed nothing wrong. Obviously this was Omega's work. Mark determined to eat the stuff if it killed him. The next mouthful—mashed potatoes laden with gravy—tasted like sour milk.

A roar of laughter blasted forth from a point nearby. Nona, startled, dropped her fork and stifled a scream.

"Don't be alarmed," Mark advised. "It's only Omega and his depraved sense of humor. He's making my food taste like swill and I'm eating it to spite him."

He conveyed another forkful to his mouth, prepared for anything. He was fooled this time. The beef tasted like beef. "It's all right now," he announced. "I guess he's left."

"I hope so," she said. "This food is so good, and he makes me nervous. I can't eat when I'm upset."

"He's not a bad sort," Mark declared, thoughtfully, "except for his habit of being as confusing as he can manage. But I guess we'll have to get used to it. He seems to be interested in both of us."

"Yes, so I've noticed."

Mark speared a slice of pickled beet. "There was something I meant to ask you," he said, trying to remember, and carrying the beet halfway to his mouth. "Oh yes... How do you account for the fact that after several thousands of years your language is no different from mine, and yet that of those oafs in the village is just so much Greek?"

"That's simple," Nona said through a mouthful of mashed potatoes. "You see, after the last great war, records of which are preserved in our museum, my ancestors gathered in the ruins of a great city. They managed to survive on stored foodstuffs until they were able to grow their own. Some semblance of the former civilization was retained, for among them were wise and intelligent leaders.

"A government was organized and later a system of education instituted. Textbooks were found in the ruins, and they naturally preserved the written language; and phonograph records and machines for playing them were also discovered. Copies of these are still used today. And it has been the continued use of these ancient records which has preserved the language, though I dare say there are hundreds of words, of a technical nature, which have dropped out through disuse, and possibly some which have been created to meet new conditions."

"VERY logical," commented Mark, placing the slice of pickled beet, which had been hovering in mid-air, in his mouth. There followed an explosion of considerable violence, which was perfectly natural, in view of the fact that the beet had all the delicate flavor and bouquet of slightly used gunpowder. "Damn," said Mark, feeling to see if he'd lost any teeth.

Nona jumped to her feet, and bent over him solicitously. This anxiety over his welfare was not entirely unwelcome. In fact he rather liked it, though he was too honorable—or too stupid—to prolong it needlessly.

"I'm all right," he gasped. "That was Omega again. The darned clown fed me a firecracker. Omega," he shouted, "behave yourself, won't you please?"

Nona looked angrily about, but Omega remained unpleasantly invisible.

"I don't think it's fair," she said, stamping one foot. "He gives you this meal and then spoils it for you. Wait till I get my hands on him."

"Leave him alone," begged Mark. "Don't be fooled by that lad. He might have the sense of humor of a twelve-year-old, but he has brain-power such as the Earth has never seen. This stuff you have see him perform is only child's play. His tricks are the manipulation of the basic stuff of the Universe—matter and energy.

"Those bodies of his represent energy wrested from radiations which pervade space, and transformed into matter in exact duplication of the tremendously complex structure of the human organizer. No, there was never a brain like his developed on the Earth."

A modest cough came from behind them. There was Omega, superannuated as they had last seen him, looking very serious.

"You are wrong there, my friend," he stated. "There are two minds right now on this earth, each of which is as well equipped as I. I'll admit they are not natural but that doesn't alter the fact that they are very powerful."

"How are they not natural?" inquired Mark.

"They're artificial, of course," replied Omega, scornfully. "I'll tell you about it. A little less than six thousand years past—you were asleep at the time—a certain Russian biologist became aware that his life expectancy was nothing to brag about, due to the fact that his country was gradually being destroyed in the course of the last war, and decided upon a bold experiment.

"He had discovered the very same fluid that I had earlier developed for the purpose of preserving my brain and those others who were the last of my race. And he had also discovered how to join the nerve-ends of two brains so that one—the more powerful one—could blanket out the ego of the other and have control of both brains. His bold experiment consisted of hooking together in this manner twelve brains!

"For his key-brain he chose the preserved one of a former laboratory associate who had met with an accident. This man had been exceptionally clever and the Russian hoped that he would gain control of the others, who were ordinary men and women.

"The biologist had no trouble acquiring these brains, for he was working directly for the government and was given all the condemned prisoners he wished, with which to experiment. He had duped officials into thinking that he was developing a new germ culture for use as a weapon, and needed live humans to try it on. His real purpose, of course, was to make himself immortal, which he actually did!

"The associate easily gained control of the other brains and soon found himself possessed of powers of which he had never dreamed. He suddenly realized that he had now regained all the senses he had been deprived of since his crushed body had been destroyed and the brain preserved.

"The twelve-brain-power mind was able to communicate, by means of thought waves, with the biologist, who informed him of his aims. These consisted of removing his own brain and connecting it with fifteen others and preserving the whole batch in a suitable container. The biologist, being a very selfish man, wanted to have the more powerful mind. The associate had been a very loyal workman when he was alive and had a certain amount of gratitude in his present state. He therefore agreed to perform the operation, but with only eleven brains.

"He didn't fancy the biologist being any more powerful than he, even if he was grateful. He didn't know then that the extra ones would have been of no use. His knowledge was still very limited. He was like a man who has suddenly lost his memory, but still has all his other mental faculties.

"He knows nothing, but has the power to reason and to acquire knowledge quickly. As a matter of fact, five brains connected in this manner would have given a maximum thought capacity. Intelligence was not increased by adding more."

"Wait a minute," Mark interrupted. "I know the biologist needed help to remove his own brain, but how could the associate do it without any hands?"

"My, my, my," Omega said sadly, peering nearsightedly at Mark. "I gave you credit for more imagination. I'll show you. Now if you will look over there you will see a fully equipped surgical laboratory."

Mark turned his head and stared. Sure enough, there it was, operating table, trephining apparatus and a number of gadgets unfamiliar to him. On the table lay the sheeted figure of a man. Then, without any volition of his own, he found himself bending over the figure and operating!

In a matter of minutes his flying fingers, had caused the strange instruments to remove the entire dome of the skull and expose the palpitating brain within. Abruptly the whole layout vanished and he was looking into the slightly dazed brown eyes of Nona, who did not yet realize that it was Omega, controlling Mark's body, who had performed the operation.

Mark nodded. "Of course. I should have guessed. I'm stupid."

"Not at all," returned Omega. "The biologist was no more intelligent than you. He didn't know at the time he presented his problems to the associate that the feat could be accomplished so easily. He expected advice as to how to build a mechanical device for the purpose. But the operation was a success and both batches of brains are alive today, each thinking as a powerful unit."

FOR a minute no one spoke. The story, Omega's feats, in fact everything which had happened since Mark's appearance on Nona's horizon, seemed like a fantastic dream or a fairy tale. Things really didn't happen that way. The last real thing which had happened to her had been the reception she had been given by the savage tribes-people. She remembered that with a shudder.

But more disconcerting than any of the other weird happenings was the man, Mark.

There were no men like him in her experience. He was like the heroes in the ancient stories. She remembered, with a delighted shiver, the way he had grinned when Omega introduced them.

The men in the city didn't grin. There was nothing to grin about. Even in their leisure moments, the men she knew thought of nothing but of how to do their work more efficiently, in order to please the overseers. That, of course, was the fault of the eugenics system. Subservience was bred into her people. It was not their fault. But it didn't alter the fact that they were very dull company.

"Then I suppose," Mark commented with labored irony, "that when you have tired of watching the amusing, but far from intellectual, pursuits of lesser people, you indulge yourself in communion with these great brains?"

"Far from it," denied Omega. "Neither is a character I should dare to cultivate. When they were mere men, they were ambitious and ruthless. And they remain the same. Both are greedy for knowledge, which is commendable in itself, but they have no decency in acquiring it.

"Several times they destroyed capable leaders of different communities just to see how well the people could make out without them. Malicious curiosity, and nothing more. Later they amused themselves by pitting one community against another in conflict. Actually enjoying the resultant suffering.

"No, my friend, I don't desire any communion with such as they. On other planets, in other galaxies, there are minds whom I admire and with whom I sometimes communicate. But these two earthborn monsters don't even know I exist. Lately they have left the people of this planet to their own devices, to acquire knowledge of other worlds. And everywhere they go their infernal experiments wreak havoc."

"But haven't you done anything about it?" inquired Mark. "Surely with your vast power, you could destroy them. They certainly deserve it."

Omega shook his head sadly. "I'll grant you they are still too young to cope with me individually, but combined I'm afraid they would be too much for me. I've never dared to take the chance. As it is, by keeping them in ignorance of my existence, I have frequently circumvented them when their insatiable appetite for creating trouble has threatened to ruin some promising civilization." Omega's mockery and irresponsibility had vanished; his tone had become that of a beset father, trying to protect his children.

"Well, something should be done," Mark insisted. "Suppose they come back and decide to give the Earth another going over? They do come back, don't they?"

"If you mean do they return periodically and inhabit their brains, as I used to do, the answer is yes, they do. It's a matter of psychology, I suppose. I know I should never have gotten the idea of destroying my brain if you hadn't suggested it. And naturally they have never thought of it either, and probably never will. So of course they will come back, just when, there is no way of knowing. Possibly not for centuries. It's nothing for you to worry about."

"No," Mark admitted, glancing at Nona. "I suppose not. It just occurred to me that as long as those two are in existence nobody could ever be sure of a quiet, decent life."

"What's the difference?" countered Omega, with a glance toward Nona. "You can't expect to live quietly and decently anyhow. Someone always pops up to gum the works." He beamed. "I remembered that phrase," he said proudly.

Mark didn't seem to hear him.

"Well, be that as it may," he said, "the idea enters my mind that it will be dark soon and we are totally unprepared to spend the night in these woods. We'd better rig up some sort of shelter. Unless of course, you'd like to transform yourself into a six-room bungalow."

Omega cocked a weather eye toward the sky which was already becoming slightly gray with approaching twilight. "It won't rain," he stated. "And it won't be cold. You don't need a shelter. I would advise that you travel in a general southerly direction. There is still an hour or more of light and the further away from our late friends the better."

"You speak as if you were leaving us."

"Don't feel too sad. I'll be back again when you least expect me."

Mark laughed. "I'll just bet you will."

"So long, Mark." The sly smile on the withered face died out and the eyelids dropped. Mark hesitated for a moment, then placed one finger on the bony chest and gave a light push. The stooped figure teetered and then fell with a thud. Nona stepped forward, alarmed, but he reassured her.

"He's just absent-minded. Forgot his body."

THE going was a bit rough in the new direction, but that fact didn't bother Mark in the least. Helping Nona over obstructions was just as pleasant a way of putting in his time as he could wish for. Her grateful smiles of thanks were ample payment for the scratches he got separating thorny undergrowth for her.

"Have you any idea at all where we are going?" he inquired.

Nona hesitated before answering. "I'm not sure, but I think the nearest place in this direction is New Haven. It is not directly south, but more to the west. We must not go there, though."

"Why not?"

"Because the city is friendly with mine and would keep me prisoner until they could return me to the council."

"We don't want that," Mark declared. "You said this city was New Haven. Then we should be somewhere south of Hartford. Was that the city in which your ancestors settled?" He remembered New Haven on crisp fall afternoons. Feathered hats. Chrysanthemums. Programs for a quarter.

"Yes," she replied. "New Haven is our closest neighbor and we often send caravans to exchange goods. But I've never been there. Women are not allowed to travel. Only armed men make up the caravans."

The sky was growing darker and the little light which penetrated through the trees was scarcely sufficient to enable them to pick their way through the dense forest. Mark spotted a clear space, devoid of vegetation, beneath a giant evergreen. This, he decided, would make an ideal place to spend the night.

"It just occurred to me that it has been quite a time since I've done any tramping through a New England woods. So far today I've seen no dangerous wild life, except for those unpleasant cannibals. But of course that doesn't prove anything. How about it?"

Nona's eyes widened, he frowned. "Oh gracious, I thought you knew! There are wildcats—thousands of them! Nobody ever goes near the forest after nightfall. Even the armed caravans will travel miles out of their way to get away from them. But you can kill them, can't you? You're so wonderful. They won't come near us when you use your magic, will they?"

"Magic?"

"Yes, the magic that you used against the savages. You pointed your finger and they fell dead. Even Omega wasn't that smart. He had to use a club."

Mark winced realizing that the girl thought him some kind of wizard with all sorts of weird powers. He was flattered, of course, but sporadic caution caused him to try to get things on a reasonable plane. "That wasn't magic. All it was was this needle gun. It's so small you thought it was my finger. It shoots needles, tipped with poison that stuns the victim for several hours. Simple, see?

"But I'm afraid it might not work against wildcats. Maybe the needles couldn't penetrate their fur. Maybe I'd better build a fire."

AS he talked, he had been fumbling in his pockets, although he knew that he would find no matches. That was one thing the old doctor had not thought of. Or maybe he had. There might have been a means of making fire in one of the cabinets, an old-fashioned tinder box or some such contrivance, for ordinary matches would have crumbled to dust with the years. He hadn't searched as carefully as he might have. His fingers encountered a spare clip to fit the automatic he had lost. A sudden train of thought snapped him into action. Tinder box—gunpowder...

An eerie scream rose in the still air, sending a shiver down his backbone, and confirming Nona's story. Removing a cartridge from the clip, he used the point of a clasp-knife to pry the bullet loose. Then he carefully selected some dried leaves, crumpled them, and mixed in the powder from the brass cartridge. Some small, dried twigs completed the tinder. Then in the fast fading light he managed to find a hard rock, about the size of his hand.

"Hold your breath," he requested, and struck the blunt end of the steel axe a sharp blow. Nothing happened. "I should have joined the Boy Scouts," he mourned, striking another futile blow. The third, however, produced a shower of sparks, although none of them landed on the tinder. On about the tenth try the tinder flared with a sudden greenish flame and continued burning merrily while Mark piled on heavier twigs until he had a sizable blaze. He was surprised, naturally, but took care not to show it.