RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

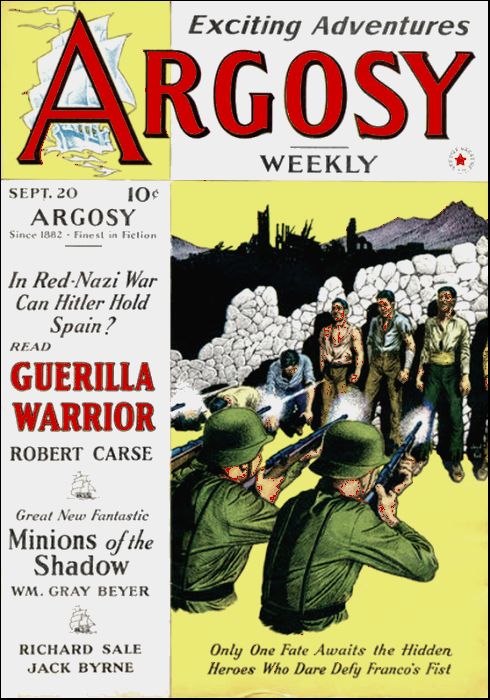

Argosy, 20 Sep 1941 with first part of Minions Of The Shadow"

Clean up the town, crusader; but remember that the Big Boss will shoot before he surrenders. Big Chief Omega (the demon shadow) may not be much good at cleaning up politics, but he can certainly make 'em livelier. Step right in here and see how history is revised while you wait.

OMEGA glared malevolently. Murder, obviously, was in his eye. The left one, that is; the right one refused to cooperate. It twinkled. But it seemed that the left one was really a true barometer of his intentions, for Mark suddenly noticed that a wicked-looking, curved scimitar had appeared in Omega's hand.

Mark watched, placid and unconcerned, as a horny thumb gauged the keenness of the steel edge. Nor did he so much as smile as Omega severed the thumb neatly at the first joint.

For the interested observer—had there been one—the scene was noteworthy. Omega, aged and wrinkled, and clothed in a flowing Roman toga, beret, and spiked baseball shoes, mirrored a combination of emotions. Indignation had followed Mark's request, but that had been followed immediately with apparently uncontrollable rage—centered, of course, in the left eye. The right continued to twinkle monotonously.

Mark faced him without a qualm, his strong face expressing exactly nothing—except perhaps, strength. There was, however, a certain purposefulness about Mark's very imperturbability. He was obviously waiting for an answer, and refused to be distracted by anything.

Not even the fact that the stump of the severed thumb immediately sprouted a hollyhock in full bloom, nor the even more startling fact that the disinherited thumb did not fall to the ground but rather soared erratically off in winged flight, affected him in the least.

It was the last, perhaps, which might have indicated to that interested observer a possibility of error in assuming that Omega's left eye was the correct one to believe. The twinkle, maybe, was the proper indication of Omega's state of mind. But almost as soon as this poor, befuddled observer had concluded that such was the case, he would have again revised his opinion. For Omega lashed out abruptly with the scimitar and snicked off the tip of Mark's nose.

At this point, perhaps, the interested observer would have gone quietly mad. For the partial proboscis also took wing and immediately engaged the thumb in mortal combat. It was a foolish thing to do, for the thumb was much larger and apparently more ferocious. It had grown a wicked pair of mandibles when nobody was looking. In no time at all it had the nose-end in a death grip, squeezing unrelentingly, in spite of the pitiful nasal whines for mercy which rent the air.

Yes, the opinion is herewith set forth that the interested observer would have lost his grip on whatever vestige of sanity remained.

The left eye continued to glare balefully as Omega growled: "I won't do it!"

Mark looked cross-eyed down the length of his nose, and was reassured to see that it was whole again. "I only asked a favor," he pointed out, in a slightly injured tone of voice. "I don't see why you have to get so upset. If you don't want to do it, say so. I won't ask you again."

"I did say so," snorted Omega. "I repeat: I won't do it!"

Mark didn't answer. He gazed sadly at the fallen gladiator which had been the end of his own nose. The thumb was still worrying the corpse, after the manner of a cat with a mouse. Some of the fire went out of Omega's left eye as he contemplated Mark's doleful expression. He quickly regained it, however, as Mark glanced up and shook his head sadly, the picture of disappointed disillusionment.

"Okay," he said, resignedly. "Forget it."

"It wasn't fair to ask," said Omega, now on the defensive. "You know the trouble I get in when I travel back in time. A friend wouldn't make such a request," he added, pointedly.

MARK suddenly, snapped out of his dejected attitude. "Now who's being unfair?" he wanted to know. "I only asked you to go back six thousand years or so. Back before I went to sleep. That wouldn't get you in any trouble.

"You told me you only got in difficulties when you go far enough back to meet yourself when you still lived in your original body. Like the time when you caught yourself merging with yourself and had to live your whole life over again. So you're just splitting hairs. That was over fifty thousand years ago."

"I know, I know," said Omega, plaintively. "But I was in existence six thousand years ago, even if I didn't have a body. And I wouldn't want to have to do it all over again."

"Your original form wasn't in existence then," Mark argued. "You were nothing but a disembodied intelligence at that time."

"Of course. But I was there just the same. How do I know I won't merge anyhow." He paused, apparently thinking of a new argument. "And if you remember back, my fine fellow, it was me that wakened you after you got that dose of sleeping potion that was masquerading as an anesthetic. Suppose I should go back, as you request, and suppose I merge with myself as I was then and suppose I get mad and refuse to awaken you again? You know it's no fun having to live your life over again, and doing everything exactly the same way you did it the first time, just to make history come out right. I'm not so sure I'd do it again. I like fun!"

Mark was silent for a long minute. The thought was appalling. If Omega should accidentally merge and refuse to awaken him from his long sleep of suspended animation, nothing he had accomplished in the fifteen years since his awakening would exist. It was confusing, in a way.

He had been awakened, hadn't he? And he had met Nona and married her and had two kids, hadn't he? How could all that be undone? He'd almost civilized the modern Vikings, and he'd freed The Land of the Brish, and he'd come back to present benighted America and made a pretty nice place of the modern city of Detroit.

Could all that be cast into the limbo if Omega decided to live his life in a different manner? It sounded slightly screwy, on the surface. He said as much.

"Oh it does, does it?" Omega's voice dripped sarcasm. "Well I'm a screwy guy, brother. Look—I'll take you back about an hour, and then we'll see what you say."

Mark braced himself, but it was too late. He felt a sudden sinking feeling, a complete absence of light, then a sensation of rapid motion. That stopped after a moment, and abruptly his vision returned. He looked around and discovered he was about a mile from where he'd been a second before. There was a stream beside him, cutting its way through a slight rise in the plain near the city. He looked toward the direction where he knew he had stood one hour before, but found that the rise blocked his view.

It was at that moment that he discovered he didn't have a body. Nor a head, either, for that matter. He was now no more than a disembodied intelligence. He could see all right, and he could hear, the rippling of the stream was quite audible. But no body! He also realized that Omega was in a similar state, though that was quite natural for him.

There was a difference, though. Ordinarily he couldn't sense the presence of Omega unless that being let it be known he was in the vicinity. But now he could sense him. Omega was right beside him. A certain tension—probably the thought waves which composed him—indicated his presence.

"How do you like it?" The question was only a thought, but he heard it as a voice.

"Be handy when it rains," he thought back. "But what does it prove?"

"I'll show you in a minute," Omega answered. "Right now you and I are a little distance down this stream. That's why I brought you up here. So we wouldn't merge with ourselves. And right now that other 'you' is making up an alleged mind as to whether to request me to take him back in time to visit some old acquaintances. And I'm making up my mind to refuse. Right?"

"The first half's right," Mark conceded. "Which means that you were reading my mind at the time. Shame on you."

"Dull reading," said Omega, with a mental sniff. "But the point is that one hour from now, our point of departure in time, you and the body I had assumed were standing at a distance of about twenty feet from that stream. Right?"

Mark didn't see what was coming, but he answered: "Right."

"All right, then. Now I'm going to use some of nature's abundant power to alter the course of the creek. Watch."

MARK watched and marveled. He knew that Omega, by mental control, could manipulate the sub-cosmic forces which pervade all space, but he didn't often get a chance to watch him do it. He saw tons of earth melt away as Omega caused a deep ravine to be cut through the little hill which stood between their present position and the place where they had been.

He refrained from looking toward that other Mark, afraid his disembodied intelligence would be forced by some unknown law to merge with that other self.

Instead he watched the ravine extend itself toward the creek. When they met, the inevitable happened. The waters of the stream were given an easier path to follow and they followed it. They flowed through the ravine.

"Now," said Omega. "Let's merge. Head down that ravine, and you'll find yourself merging, whether you want to or not."

Mark discovered that he needed no more than a thought to move his bodiless form. With Omega at his side he sped down the new creek bed, in advance of the water. As they moved, Omega extended the ravine along with them. But Mark didn't notice. He had sighted his own body, standing in conversation with the aged one in the Roman toga.

Unaccountably he felt drawn to it, and noticed that his speed had increased, hurtling him toward it. In a space of a few seconds he had reached it, and suddenly found himself looking through its eyes. He found himself stopping in the middle of a sentence he couldn't remember beginning, and turned to Omega in astonishment.

Omega grinned. "You could probably remember what you were saying at this moment, if you thought a while. But it doesn't matter. The point is: Are you going to stay here and get wet?"

Mark, suddenly alarmed, turned to face the creek. As he guessed, it was dry; or rather, slightly muddy. Glancing quickly back, he saw that the new course of the stream would pass directly over the spot on which he was standing. And furthermore, it would arrive in a matter of seconds. Hastily he moved away to higher ground.

Not that it would have been dangerous to remain, for there was only a foot or two of water winding its way downward. But he didn't relish getting his sandals soaked. Omega moved with him, grinning gleefully.

Mark stopped, safely out of range of the new creek, and faced the aged caricature of a man. "Are you imitating a gargoyle with Cheshire cat tendencies?" he asked. "Or has something gone over my head?"

"The latter, I assure you," Omega drawled. "It happens again and again. Perhaps I should remind you that less than a half hour has passed since we went back that hour. Now it should occur to you that already that hunk of protoplasm you inhabit is doing things it didn't do originally during that hour. And do you intend to be standing in the middle of the creek, getting your tootsies wet, when the hour is up? Or did I change history by changing the course of the stream?"

Mark scratched his head. It didn't itch, but it just seemed the thing to do. There was something he should grasp...

"Ah," he chortled. "But you took me along with you back in time, and when I merged with myself I made my body do something it hadn't done originally. Suppose I hadn't gone with you? Then I would have been at the original place at the end of that hour and—"

Omega chuckled gleefully. "Sure," he said derisively. "You'd still be standing over there in the water. You wouldn't be moving out of the way when it suddenly began to creep up your ankles. You'd stand there, getting wet for the next half hour."

MARK frowned. There was no doubt of it. Omega had changed history. Even at this very instant he had been standing in a different place. If Omega hadn't decided to demonstrate, he would be standing there a half hour from now. He was, in fact...

It was all very confusing. Suppose Omega hadn't made that little excursion in time. This creek was pretty well stocked with trout and he often fished at the very place where there now was a shallow furrow of drying creek-bed. A week from now, maybe tomorrow, he would be fishing in it. But Omega had made his excursion, and there wouldn't be any water in that furrow.

"Then I'm to infer that all these fifteen years I've lived..." He hesitated momentarily, but went on again. "And those two kids of mine—they'd just cease to exist if you went back in time and decided not to awaken me?"

Omega chuckled again, giving Mark a disquieting feeling that he was talking to omnipotence or something very near it. "Exactly," Omega said. "You, and all the things you have done would be as if they had never existed. Maybe they don't exist anyway," he added reflectively. "Maybe you're only here because I thought of you. Anyway, I guess you don't feel like taking a chance on oblivion, just to see a few of your old friends."

Mark looked at the new creek, musingly, then suddenly smiled. "I'll take a chance," he said. "Take me to my home town, just prior to the time of that operation which ended in my protracted nap. I've got a friend there by the name of Harvey Nelson. I'd like to see him."

Omega was startled, a thing which seldom happened. He looked at Mark searchingly for a few seconds. Then he smiled.

"I see," he said. "You lived in New York, about ninety miles away, at that time. So you figure you won't meet yourself. And I was watching the results of that operation, just for something to do. I told you that once, didn't I? But how do you know that I wasn't in your home town too, somewhere around that time? I get around, you know."

"Were you?"

It was Omega's turn to frown. "I don't believe—" he began. "Aw Mark, don't be foolish about this thing. If you go back, you'll only get more homesick. And you won't be able to make yourself heard, anyway. You haven't sufficient mental control of the forces involved. And even if you had, you'd only scare the pants off somebody. I can't give you another body, you know. Not in the past, at any rate."

"I could see and hear, couldn't I?"

"Sure," Omega said. "Just as you could a little while ago. But I advise against it. You'll wish you hadn't..."

MARK felt the same feeling of faintness, accompanied by the blackout, which he had experienced before. This time it lasted slightly longer, but ended just as abruptly. But the return of his vision didn't disclose anything as rustically beautiful as the landscape around the former creek.

It was beautiful, of course, but in a different way. Mark had to admit that the female figure which lay on the floor before his disembodied vision—it was quite comely.

And she was dressed to display all her pulchritude. There was only one thing wrong with her. Her throat was cut! He stared, stunned. For an instant he couldn't marshal his brain—or the ethereal pattern which functioned as a brain—to bring him up to the present, or even the past. The sight of such a lovely creature, cut off in the prime... Dimly he realized that someone was speaking.

"... Thanks a lot for your help. But keep yourself available in case I need you."

He looked up and saw the speaker. He was a small, dapper man who had the air of a professional of some sort. His words, however, indicated that he must be of the police. Mark was attracted by a movement at the door, and turned in time to see the backs of a man and woman pass through it. He recognized them immediately.

"That's Harvey Nelson," he exclaimed. "The girl's the one he's being going with for several years, but hasn't gotten anywhere with."

"Terrible English," Omega remarked. "Well, take a good look at him, because we're going back where we came from. I'm nervous."

Mark started to move toward the now-closed door, knowing full well he would pass right through it, in his present bodiless state, but abruptly stopped at the sound of another voice.

"Hadn't you better put a tail on him?" it said. "It'd be a swell gag to come back and discover a body you'd killed an hour ago."

The dapper man snorted. "You state cops," he said. "He'll be looking for a tail. I know where I can get hold of him. I'll put a man on him later, when he's not looking for one."

Mark shot a mental message to Omega to wait. "Nelson's suspected of this murder," he explained. "We've got to do something. Let's hear..."

"I'll bet his story will check," remarked another man.

The dapper man sneered. "We'll see," he said, enigmatically.

Mark was alarmed. "He thinks he knows something to use against Nelson," he told Omega. "I know these cops. If they've got a good suspect, they don't bother to look further, just marshal all the evidence they can, whether it's the right man or not."

Omega groaned audibly. "So what?" he inquired wearily.

"Let's go back further in time and see what caused the present state of affairs," Mark suggested. "Maybe we can take a hand."

"We?" asked Omega sarcastically. "Why it takes half my mental strength to drag you around with me. We're not in the present, you know. We're in the past, and it requires a special effort to even stay here. Unless, of course, we should happen to meet up with ourselves. Then we'd stay whether we wanted to or not. I tell you I'm getting nervous!"

"Calm yourself," said Mark. "We're almost a hundred miles away from our old selves. We're safe. We can't merge. Come on, be a sport. You wouldn't want to see an innocent man convicted of a crime, would you?"

"How do I know he's innocent? A friend of yours. Oh, all right. We'll go back a few more days and see what led up to this. But I don't mind telling you it's hard to keep in one spot very long, this far back in time, let alone change events to any extent.

"You must remember that after six thousand years, the fabric of time has set itself quite firmly. And to make any change which would nullify things which have existed so long requires a lot of energy. And besides, I'm a mere shadow of myself, this far back. All right, brace yourself!"

In the instant before oblivion again claimed him, Mark noticed a husky man in a blue civilian suit, leaving by the door Nelson and the woman had gone through. Then darkness descended.

FOWLER'S third chin took on a crafty look. It was, of course, only aping the rest of his face—if the thing could be called a face at all. Pembroke, the party leader, considered it more like a slightly deteriorated pumpkin, than a physiognomy.

True, the thing had a nose, and most pumpkins are totally without noses: and then too, there was the multiplicity of chins—another unpumpkinlike attribute. But, on the other hand, it did bulge on all sides, and had a slightly yellowish cast—probably something to do with the liver.

It was a versatile thing, sometimes mirroring a benign, paternal emotion; or again expressing deep-felt horror or repugnance—as when viewing with alarm—or possibly portraying cheerful martyrdom. It all depended on the subject being discussed.

Right now it was crafty, which meant that it was crafty all over, from the most elevated lock of snowy hair to the nethermost chin.

Pembroke shuddered slightly as he brushed the tips of his fingers together and regarded his highly polished nails.

"It's in the bag, boss," said Fowler's hearty voice. "Nelson will turn the trick. I've got him eating out of my hand."

He waved a hand.

"I hope you're right," said Pembroke. "You're well aware that we can't afford to lose this time. If Nelson won't play ball, we'll make him see things our way."

"No, no, no!" wailed Fowler, all three chins registering agitation. "Nelson trusts me. That's why he takes my suggestions. But for God's sake, don't try to force him!

PEMBROKE stroked the sleeve of his coat with finger nails which were beyond improvement as far as luster was concerned. "All right," he intoned. "You'll get a chance to work out on him first. Persuasion is the better course if it'll do the trick. But I can't forget that Nelson's been acting up a bit lately. That committee meeting last week..."

"Aw boss," entreated Fowler. "He didn't do that. I was looking right at him, and his feet were tucked under the chair. He never moved them!"

Pembroke shook his head doubtfully. "The committeemen didn't think so. And neither did the mayor. As soon as I pulled that bass drum off his head he pointed a finger at Nelson and said he'd been kicked."

"He must have tripped," hazarded Fowler. "Some of that metal work around the footlights was loose. And anyway, it made a hit with the committeemen. They got a kick out of old Picklepuss poking his head in that drum."

Pembroke allowed his face to come somewhere near a smile. "So did I," he confessed. "But the fact remains that Nelson was the only one who could have done it. He was sitting right back of His Honor. Then of course there was that matter of the governor's daughter..."

"She liked it, didn't she?"

"She didn't like Nelson denying it," retorted Pembroke. "Why I even heard the smack of that kiss myself!"

"You were sitting alongside her too, weren't you?" inquired Fowler meaningly. "It must have been pretty dark in that theater."

Pembroke flushed. "You're not insinuating that I—"

"No, no, no!" Fowler denied. "Only she's a pretty neat looking frill, just the same."

"Never mind that!" snapped Pembroke. "Now get out of here and line up Nelson. This election's got to go our way, or we'll be on the inside, looking out. Danvers must win the primary."

Fowler suddenly whitened. He knew the chief was right. There were certain things which hadn't been covered up too well. If a reform administration got in power, they'd start discovering things. There would be a howl which would bring St. Peter to the gates with a shotgun, ready to repel invaders. Fowler left the inner sanctum, quaking inwardly.

There was a very good reason for his concealed trepidation. He wasn't at all certain that he could bring Harvey Nelson around to his way of thinking. For Harvey Nelson had been acting a little queerly of late. Kept looking around him as if he heard voices, or maybe was afraid of something. Then, just when you didn't expect it, he'd pull some practical joke.

And he was clever about it too. Nobody had actually seen him do anything. He must have learned most of these tricks while he was on the other side. He'd never shown any sign of being a sleight-of-hand artist before. And he invariably denied pulling his tricks—and did it with such a bewildered air of innocence that everybody knew right away that it was an act.

BUT it really wasn't the tricks that had Fowler worried. Harvey had shown signs of questioning the wisdom of his suggestions lately. And that was bad. If Nelson ever learned the truth... Fowler hated to think of it. Yet he had to think of it. His bread and butter, not to mention his freedom, was at stake.

Harvey Nelson had always been such a trusting soul. He had looked up to Fowler as being a man of integrity and civic-mindedness, ever since he'd been a high-school student. It seemed incredible that Nelson could be losing his trusting faith in his guide and mentor.

In fact, it was this unshakable belief in Fowler's honesty, more than anything else, which had led Pembroke to place Nelson in his position as the leader of the most thickly-populated ward in the city. It was certain that he would allow Fowler, Pembroke's stooge, to guide him in his inexperience.

And he had. Harvey's popularity as a war hero and all-around athlete had enabled him to garner almost all the votes in the ward, directing them as Fowler suggested. But now...

That Art Museum thing, for instance. Nelson had asked why it had taken nineteen million dollars to complete a project which a local contractor could have put up for less than six million. That had been the present mayor's baby, and Nelson had helped elect him. Fowler had said that he was a man of integrity, and, now he was having trouble, in the light of some of the administration's acts, in making Harvey keep on believing that the mayor was a paragon of virtue.

Of course the mayor didn't matter. The party was going to kick him out anyway. But it was important that Nelson keep faith in Fowler's judgment, or they'd have plenty of trouble electing the right man in the coming election.

HARVEY NELSON was a sorely pressed man. It was getting so that every time he got near anybody, something happened. And everybody promptly blamed it on him. And those voices were bothering him, too. Voice, rather; it was always the same one. And the funny thing about it was that it always sounded like his own.

That, of course, he could keep to himself. In fact he'd better keep it to himself. People who hear voices are usually locked up in the silly-shanty. But these peculiar happenings were rapidly undermining his morale.

Fleetingly it occurred to him that perhaps everybody else was going crazy. But no, that was bad. Lunatics usually thought that, and he wasn't quite ready to admit that he might belong in that category. And besides, these things frequently happened when there were too many people around. The incident of the mayor, for instance, had happened in front of a thousand people. And even the mayor himself had thought that Nelson had kicked him!

Harvey shuddered a frame-racking shudder at the thought of it. He had quite a frame to rack, too. To think that he would be accused of kicking the mayor! He had nothing but the most profound respect for His Honor. Hadn't Jim Fowler himself vouched for the man's high ideals?

Of course there was this matter of the Art Museum; but then His Honor was nothing but the innocent dupe in that. He had certainly had no hand in awarding the crooked bids which the papers were always talking about. If, indeed, there had been any crookedness. The papers were always howling about something.

"It was crooked, all right," assured the Voice.

Nelson involuntarily spun around. He knew, even as he turned, that he would see nothing but the empty living room of his bachelor quarters. But the thing was so startling that it almost always caught him off guard. Except, of course, on those occasions when the voice seemed to come from a point in front of him, and he could see instantly that no one was there.

That was one of the peculiar things about the voice. It came, on different occasions, from all thirty-two points of the compass. It seldom repeated itself twice in succession from the same direction.

The desk lamp made Harvey's shadow huge and grotesque as he hunched over the papers on the desk. He read them over carefully before signing. Fowler had once said to do that, always. But then Fowler had said that he had checked over these particular papers, and that they were okay. He'd sign them, therefore, even though some of the items listed seemed to be a bit high.

His office as county commissioner required that he affix his signature to the new budget estimates, though he really didn't know what half the items were for. But Fowler did, and that made it all right. He ought to know; most of the county money went through his hands before it was finally paid out.

Harvey thanked his stars that he had such an honest man as Jim Fowler to help him with these complicated matters.

"He's as crooked as a ram's horn!" said the voice, disgustedly.

Nelson sat up rigidly. This was too much!

"He's not!" Harvey exploded.

Then he stopped, ashamed of his lack of control. He'd let his imagination get the better of him that time. He'd actually answered the phantom voice. The voice seemed to be as surprised as he at this slip.

"Well, well, well," it said. "So you finally admit that I exist. It's about time!"

Harvey shuddered again, but not for the same reason as before. He suddenly realized that he wasn't imagining this voice. It was real! He knew it because he was thinking rapidly while the voice was talking. Before, his mind had been comparatively at rest, and the voice had crept in between his thoughts. But now—

He couldn't think of two things at the same time!

HARVEY was a very level-headed man, not given to fancies at all. And when he faced a situation, he faced it, no matter how incredible it appeared on the surface. He'd run across some pretty queer things in France, and had learned to take new ones at their face value.

That, though he didn't know it, was one of the reasons why he was such a trusting soul. He didn't look for concealed motives, convinced as he was that everyone was as straightforward and honest as himself.

"Who are you?" he asked, shakily.

The voice didn't answer immediately. It seemed to be thinking over the desirability of revealing its identity.

"I'm your shadow," it finally said, a bit sullenly.

"My what?"

Harvey wheeled and looked at the wall. His shadow was there, all right, and the voice had come from behind him this time. Vainly he tried to remember where his shadow had been on some of the other occasions. But his mind was so chaotic at the moment that he couldn't be sure. Ordinarily he would have accepted the voice's words at their face value, but in the case of this entity which seemed to be given to making such obviously lying statements, he was a little wary.

"I don't lie!" said the voice, angrily. "I've tried, all right. I'd like to lie because it's one of the things you never do. But it seems that's one trait I've inherited from you. I'm glad there aren't any others."

Harvey thought that over carefully before answering. Whatever the voice was, it seemed that it could read his mind, and he didn't like that a bit. And it might be lying, in spite of the denial. He'd never heard of a shadow that talked. But then the old lady had never heard of a giraffe, either. And if the voice really was incapable of falsehood, then it meant that the mayor...

"It sounds a bit fantastic," he ventured. "Shadows are usually seen and not heard."

"I know, I know," said the voice. "I'm a bit puzzled about it myself. It's very seldom us shadows ever get strength enough to do anything. But I imagine it had something to do with that light outside the taproom, last week."

"What taproom?"

"The one on Fifty-Second Street, where you were hoisting them. There was a red neon sign with a blue ring around it. Then there was the full moon overhead. I think it was the combination of the three that brought me to life. Didn't you feel me heave up beneath your feet when I felt the strength flowing through me?"

Harvey scratched his chin reflectively. He did remember the pavement had seemed a bit unsteady that night, but had attributed it to the poor quality of the soda which had been mixed with his Scotch.

"How is it that Fowler's shadow didn't do likewise?" he wanted to know. "He was just behind me, and the same light must have struck him."

"Not quite," said the voice. "The moon moves along, you know. The combination must have been slightly different when he passed beneath the sign. Naturally a very delicate balance of light properties must be required to bring a shadow to life, or the thing would happen more often."

Harvey nodded. It all sounded very reasonable, he decided. But he didn't believe it, just the same. He was willing to accept a disembodied voice as belonging to one of the dear departed, but the idea of a shadow owning one was a little too much for him. Cautiously he turned in his chair, until he was facing the desk once more.

"I hope you don't mind my turning my back," he said. "One can't always have one's shadow in front of one, you know."

As he talked, he suddenly snapped off the desk lamp. A thin streak from a street light came from the edge of one of the curtains, but the room was otherwise in total darkness. If the voice was really his shadow, it would now be unable to answer, for there wasn't enough light to form a shadow.

"One is often skelly in one's reasoning," said the voice, from the other side of the room. "One casts a shadow, regardless of the dimness of the light which is shining on one."

Harvey swore and turned on the desk lamp. Then the thing was telling the truth. The thought suddenly appalled him. The voice had said that Fowler was a thief!

"AND I can prove it, too!" said the voice, exultantly. "The proof's right on your desk. Fowler figures on about ten percent of that appropriation to wind up in his bank account. The party fund will get ten more. And the taxpayers might get about fifty cents worth of value on the dollar—if they're lucky. Why don't you cut yourself in on some of that?"

Harvey listened in amazement. What a thought! If that voice really came from his shadow, the shadow certainly had none of his honesty and sense of fairness. But just the same, it might be telling the truth. Harvey Nelson turned to the papers on the desk, suddenly suspicious.

"What's crooked?" he muttered, lifting, the first sheet of the budget estimate.

"Payroll!" said the shadow derisively. "One million, four hundred thousand dollars!"

"What's the matter with that?"

"Nothing. Only that over a quarter of it is allotted to dummies. Men who don't exist. Why there's supposed to be thirty-five inspectors in the Bureau of Weights and Measures alone. How many did you ever see?"

"Well," hedged Harvey. "They're always out inspecting scales and such things. That's why I never saw them all at once."

"Phooey! You can check them, can't you? Go over to that file, and look over the list of names. There's one called Plotsky. Look at the address, and then check it with the city directory."

Harvey did as he was told, slightly mystified but willing to be shown. Plotsky, it seemed, lived in a house in the forty-one-hundred block on Second Street. The directory claimed that the block was devoted to the site of a cemetery.

"See that?" exulted the voice. "Fowler's so brazen he don't even bother to pick a real address. There's a lot of stuff like that. There's also plenty of corpses in that block who vote, too. All good party people. Why, with the in you've got..."

But Harvey was no longer listening. He dug into the budget estimate and started taking it apart, piece by piece. The voice kept quiet while he worked, and in an hour he had sliced half a million dollars from the total.

He made a separate list of the things he had cut. He wasn't sure of all of them, but some he had managed to check with the aid of his files. Tomorrow he would investigate the remainder, at his office. Then he would present the new estimate to the city council—the lowest figure since the turn of the century.

"WHAT'S the idea?" Mark inquired, with some asperity. "Do you have to plague the guy? All we want to do is to prevent him from discovering that body, so he won't be suspected. Even better—maybe you can prevent the murder altogether."

"You keep your disembodied nose out of this!" Omega retorted. "I'll do it my own way. And have a little fun in the bargain."

"But why all this stuff about being his shadow?" Mark wanted to know. "Can't you just—"

Omega chuckled eerily. "I've got to interfere a little bit at a time. So I invented the shadow idea to make it seem plausible to Nelson. There's got to be a sensible reason for not letting him act entirely of his own accord."

Mark snorted. "Sensible! A shadow coming to life!"

"I keep telling you that I don't have much power, this far back in time. Not near enough to take a significant incident and change it bodily into something else. I'm comparatively weak, so I've got to make little changes which will accumulate into a major variation from the events which really happened."

"Okay," said Mark, grudgingly. "But I don't like the idea of scaring people into thinking they've gone whacky."

UNFORTUNATELY for Mr. Fowler, he chose this particularly inopportune moment to visit Harvey Nelson. He was perspiring freely from the one-flight climb and wore a jovial smile as Harvey opened the door. It changed to a look of ludicrous surprise as a big hand grasped his lapels and jerked him inside.

"Explain this!" demanded Harvey, shaking the sheaf of papers in his face. "Explain these items I've marked off!"

Fowler sputtered incoherently as he examined the papers. His face took on a look of incredulity as he perused item after item.

"My gosh, boy," he finally breathed. "We've been duped!

Harvey suddenly lost his fury. "Duped?" he asked. "How?"

But Fowler didn't answer immediately. A very realistic storm cloud was gathering on his chubby face as he strode back and forth, stopping occasionally to glare at the offending papers.

"We've been duped, son," he said, finally. "And I think I know who is behind this dastardly thing." He paused and picked up the papers, stuffing them in an inside pocket. "You leave this to me, boy. I'll move heaven and earth to uncover the guilty person!"

Harvey Nelson suddenly felt as if a great burden had been lifted from his soul. The shadow, if not actually lying, had at least been mistaken. He ignored the small voice in his ear which said: "You're being duped, you dupe!" and showed the wrathful Mr. Fowler to the door. Nobody could have been more surprised than he when Fowler tripped on the top step and went bouncing down the stairs.

Mr. Fowler sputtered to a stop at the bottom landing. He looked up at the solicitous face of Harvey, an expression of hurt reproach on his own face.

"You tripped me, son," he accused. "After all I've done for you."

Harvey made hasty and horrified denials as Fowler went down the remaining three steps to the street, shaking his head unbelievingly. His jowls wagged to and fro, making him resemble a pug dog shaking himself after an unwanted bath.

Harvey mounted the steps and entered his apartment, wrath bubbling within him. He sat in the chair by the desk and faced his shadow, which seemed to be leering at him flatly, from the wall.

"You meddler!" he said in a quiet, deadly voice. "Fowler's an honest man. Now I've hurt his feelings, thanks to YOU."

The shadow chuckled gleefully. "That ain't all that hurts," it said. "But as for Fowler's honesty, phooey! He's a crook, just as I said before. I can't lie, you know."

"You can be mistaken," retorted Harvey, clenching his fist and wishing he could sock a shadow.

"I can, but I'm not," stated the shadow. "I can feel his thoughts as well as yours, and I know he's a crook."

Harvey came alert. "You can feel his thoughts? That's absurd!"

"No it's not. When I fall on him, his thoughts get all jumbled in with yours. I've noticed that about people ever since I came to life."

Harvey looked mystified. "What do you mean when you fall on him?"

"Just what I said," retorted the shadow. "When he walked back and forth across the room, after, you showed him those papers, he kept passing you. The light being back of you, I fell on him. And when I did, I could read his thoughts. Kinda mixed up, though."

Harvey stroked his chin thoughtfully. "What did he think?"

"He was scared, mostly. He kept thinking of what Pembroke would say. He was also trying to figure if it would be better to scrap the estimate and lose his graft, or to try to get rid of you, somehow, and put it through anyway. The last time I fell on him he'd made up his mind to burn all records of past years in your department, to prevent you from checking up. Then he figures to bring a bunch of men, at five dollars a throw, and introduce them to you as members of the various county bureaus under your control. He intends to account for all the dummies on the payroll."

HARVEY slumped back in his chair. All the wind had been knocked out of his sails. Values he had cherished all his life were being knocked into a cocked hat. If Fowler, his idol of virtuous selflessness, was made of clay, then what things could he accept as true?

Did nothing exist as it appeared on the surface? Did he have to suspect every hearty handshake, and assume that it masked a desire to knife him in the back? Did every honest face conceal evil and wickedness?

"Of course not," the shadow told him. "Lots of people are honest, the suckers. All you have to do is forget that a face reveals anything. That don't mean that you have to go around suspecting every thing you see. It don't mean that you have to figure that everybody who acts like your friend is really your enemy. People really like you, for some reason I can't figure.

"All it means is that you shouldn't allow yourself to be impressed either way by appearances or actions. Don't be so damned guileless, just remember that everybody is looking out for himself, then you can place a better value on people's motives.

"Come on, now; snap out of it, and let's go out and have some fun. I feel like kicking a few people in the pants, or their corresponding garments."

Harvey sat quietly, not answering, his eyes focused dazedly on the wall. He noticed abstractedly that his shadow was moving, apparently dancing up and down impatiently, while he himself was motionless. But his mind was too occupied on other matters to pay any particular attention to such antics.

"He's going to burn the records," he finally said, aloud. "I'll put a stop to that!"

He sprang to his feet, and failed to notice that his shadow failed to do likewise. Perversely it crouched. Suddenly Harvey felt himself slammed back into the chair. It seemed that a pile-driver had struck him somewhere south of the short ribs.

"Listen to me, Rover Boy," hissed his shadow. "You're not going to start any campaign of reform around here. If you tried, first thing you know Pembroke would have one of his thugs slide a shiv between your ribs. And then where would I be? Nothing doing, son. I want to have some fun out of your life. Get on your coat now, and we'll go out."

"YOU'RE making things worse!" wailed Mark. "Now that he suspects what's going on, he'll stick his neck out and Pembroke will take a slice at it."

"I'm stopping him from doing anything foolish, ain't I?"

Mark groaned. He knew what Omega considered fun. He'd seen several samples of it in the past hour or so, during which he and Omega had visited Nelson several times. These visits covered more than two weeks of Nelson's life, and already Mark could see the effect they were having on his old friend.

"But you're changing his very character," he protested. "That's not necessary."

"Sure it is," said Omega, calmly. "He's been asleep all his life. His character needs changing."

"I almost wish I hadn't started this thing," Mark moaned.

"All right," said Omega brightly. "We'll quit and go back to our own time. The air's better anyway."

"As if you cared about the air," said Mark, sulkily. "No! How about the murder? We can't leave things that way."

"All right, then. Stop trying to interfere. And—Oh oh! Watch this!"

HARVEY got groggily to his feet. His breath was coming in short gasps, occasioned by a partial paralysis in the region of the solar plexus. And his brain was not functioning any too well. It had come as a shock that his shadow could exert such force, and especially that it could be directed against himself.

"I'm tough stuff," gloated the voice. "And listen: when we get outside, don't talk to me out loud. If you want to say anything to me, just think it. Call me Omega when you want to think anything at me. Then I'm sure to pay attention."

Out on the street Harvey found himself directed around to the garage, where he kept his car.

"We're calling on your girl friend," Omega announced. "Nice girl, by the way. Though for the life of me I can't understand what she sees in you."

Harvey steered the car out of the garage, then suddenly shot down the street in second gear, rapidly accelerating. He was doing forty before he shifted into high. This wasn't Harvey's way of driving at all. He had always been a cautious driver.

But Harvey Nelson was a hard man to lick. And Omega couldn't drive a car and concentrate on Harvey's thoughts at the same time. It was possible, therefore, for Harvey to snatch a hand from the gear-shift lever and turn off the ignition.

Then he placed the hand on the steering wheel and strove mightily to bring the car to a safe stop. He succeeded, too, and learned a new fact about his shadow's powers. Omega could overpower him only so long as he operated unexpectedly. When it came to a slow tug-of-war test of strength, Harvey was the stronger. Omega maintained a sullen silence as Harvey started the car again and drove on at his usual discreet pace.

The sedan pulled up in front of an imposing apartment house and parked. Nelson suddenly began to have misgivings. This Omega person was obviously given to pranks of a most practical nature. And Harvey was always very decorous in the presence of the opposite sex. Especially Millicent.

"Don't worry," came the voice in his ear. "I won't do anything she won't like."

Omega accompanied this assertion with a suggestive wallop in the small of the back; and Nelson's wind went out with a blast which almost bulged the windshield. He panted a little and felt gingerly at the bruised portion of his ribs. But in spite of a throbbing in that region he felt reassured. Omega never told a lie, and it was altogether possible that he possessed enough personal honor to keep his promise. Harvey climbed from the car and entered the apartment house.

Omega had said that he wouldn't do anything Millicent wouldn't like. Now if he only stuck to that... Harvey entered the elevator cage before he thought of something which caused his misgivings to return.

"Omega!" he thought, as the cage began to rise. "Just what sort of thing do you suppose she likes?"

"Quiet," hissed Omega. "I know my women."

"How?"

"Easy. In the past week you've been around plenty of women. Whenever the light cast me on them, I could read their thoughts. You know—though I find no good reason for it—they all seem to admire you. Your tall, stalwart figure; that shock of sandy hair; those rugged, honest features, and especially those baby blue eyes. Son, if you weren't such a dope you could be cutting yourself in for plenty..."

TWENTY-TWENTY was the number on Millicent's door. Harvey rapped apologetically with his knuckles. At least he started to, but when the knuckles struck, they hit with resounding force.

"Don't be so damned timid," rasped Omega. "Women like their men to be masterful. Go in there like you knew you were welcome. Don't vacillate. Tell her you're going to take her out and hit the hot spots. I want fun!"

The voice chortled.

After a moment the door opened. Millicent, apparently on the point of retiring, was clad sketchily in a negligee which evidently hadn't been designed for warmth. Her face revealed her pleased surprise at the sight of Harvey, while the negligee revealed contours which shouldn't have been concealed anyway.

Harvey, about to open his mouth and apologize, for his unexpected call, suddenly felt himself catapulted across the threshold.

His arms, extended to catch himself, encircled her slim figure. She looked up into his eyes and tilted her face at the proper angle. Harvey kissed her. Long and lingeringly. The sensation wasn't at all disagreeable. But after a few seconds he evidently realized that this was anything but decorous behavior, and abruptly terminated the osculation. He stood, tongue-tied, while Millicent heaved a deep sigh.

"Why Harvey!" she finally exclaimed, after finding enough breath to do so.

"ALL you need now is bow, arrows, and diaper."

"Aw, the guy needed a push. He wasn't having any fun. Too busy thinking about the proprieties and such. Before I'm through, he'll know the facts of life."

"Could be... But two will get you five that Harvey Nelson teaches you something about sales resistance."

HARVEY turned a deep crimson. He fortunately caught himself on the point of lamely explaining that he'd tripped. That would never do now.

Millicent disengaged herself after a minute and sat weakly down on a divan. She stared quizzically at Harvey, who appeared about to sit beside her. But Mr. Nelson remembered something at that moment. Omega wouldn't make a good third on a divan. Harvey didn't trust him.

"Milly," he said, hesitantly. "Let's go out... Celebrate—or something."

Milly didn't need any coaxing. She left the room with the promise that it would take only a minute to put on her glamour.

Omega decided to intervene. "I've changed my mind," he said. "We'll stay."

"No we won't," Harvey muttered. "I've decided to go out now."

After a moment of silence Omega said: "All right. The night's young. We go out, but don't get any funny ideas about who's boss." A light dig in the ribs, accompanied by a wrenching twist of the nose, emphasized the words.

Harvey was about to try a little experiment with the lights when Millicent appeared, radiantly beautiful, and apparently as happy as she could be. She smiled at him as if they shared a delightful secret. He couldn't imagine what it was, but being a bit delirious himself, helped her on with her coat, and kissed her again before opening the door.

The sedan was about to pull away from the curb when abruptly the night was shattered by the raucous wail of a fire siren. It was followed roaringly by two red trucks, one containing sundry ladders, hooks and half-dressed men, and the other heavy with pumping equipment and bosses.

Harvey followed just as speedily with the sedan, Millicent raised a hand to stifle a scream as he cut around a corner in their wake, narrowly missing several cars.

And Harvey himself was doing the driving this time. Omega had nothing to do with it. He merely chuckled eerily in Harvey's ear, and murmured: "Doubt my word, would you? There goes the evidence—up in smoke!"

AS Harvey had feared, the fire engines stopped at one of the corner entrances to the City Hall. Men armed with portable fire-extinguishers and axes boiled through the entrance. With a scream of tires he brought the sedan to a stop beside them.

Harvey Nelson was suddenly undecided as to the next move. He knew who was behind that fire, though it wouldn't do any good to say so. He'd have to prove it, and he wasn't so sure that he wanted to. Warily, he headed the sedan away from the fire-fighting equipment. He was still in a fog of mental indecision as he absently, noticed a sign, "Club Patelli," and pulled in to the curb.

Two tipsy revelers, who had been about to leave the place, stopped abruptly. Harvey's topper had raised straight in the air and then sailed toward the hat check girl's window. The tipsy two applauded noisily. Neither noticed the expression of bewilderment on Harvey's face when the hat lifted from his head.

"Thassa dandy trick," complimented one of the revelers. "Show me how you do it?"

The hat obediently sailed out of the hat check girl's hand—which happened to be directly in Harvey's shadow—and returned to his head.

"You just raise your left eyebrow," Harvey explained. "Like this!"

The hat repeated its performance, going slowly and unerringly to the girl's hands.

"S'wonderful," said the stew, blinking furiously. "Gimme my hat, gorgeous."

Harvey and Millicent followed the headwaiter to a choice table by the dance floor. A bill of fairish denomination accounted for this. Harvey had decided to make the best of things, even if he went broke in the process.

Millicent leaned confidentially over a small table, after a waiter had disappeared with their order. "How'd you do it, Harvey?" she coaxed.

"That hat trick?" Nelson breathed deeply, inhaling a heady fragrance which must have been caused by perfume doused in her hair.

"I didn't do it," he said, weakly. "I'm haunted."

"Sissy!" Omega remarked, quietly.

"Nonsense," she said, amiably.

Harvey, already in a mental turmoil, was spared the necessity of elaborating. For at that moment Fowler appeared, waddling precariously between the close-set tables. There was an urgent light in his eyes as he spotted Nelson.

"Boy!" he puffed. "Am I glad to see you! Been calling all over town, Something terrible's happened! Everything in the office is burned up. We'll have to round everybody up and get to work on a new budget estimate. There's no use trying to dig into the old one and see who's been pulling the wool over our eyes. All the records are destroyed."

Harvey looked at him sadly as he puffed to a stop. Somehow he didn't have the heart to be mad at the man. Fowler had helped him over many a tough spot; and now, in spite of his proven perfidy, Harvey found himself trying to excuse the attempt at self-preservation.

He smiled disarmingly. "That's a tough break," he said. "You'll have to get to work on another. Make sure this is a straight one. I'll help you with it myself. We won't have any dummies this time."

Fowler straightened. His face adequately revealed his injured feeling. "Why boy," he said. "You don't think that an estimate of mine would be other than—"

Harvey waved a hand. "Of course not," he interrupted. "But I'll feel better if I check everything. See you at the office."

Fowler nodded unhappily and turned to leave. At that moment he felt the sudden contact of a shoe, speeding his departure in a very undignified manner. But he didn't look back, remembering the peculiarities he had already observed in his protégé.

FOWLER didn't let any grass grow under his feet. He left the night club and took a taxi directly to the home of one Felix Pembroke, the real brains of the Party. Pembroke got out of bed to receive him. Fowler babbled forth the events of the evening.

"You incompetent fool," said Pembroke finally. "He must suspect you had that fire set. You're the dumbest man I ever saw when it comes to covering your tracks."

"Some of your own tracks aren't covered so well," Fowler reminded him. "And that'll put us in a nice spot if we don't get our man in at the primaries."

Pembroke nodded grimly. "And I suppose Nelson will do the opposite of anything you suggest, from now on?"

"That's what I'm afraid of," said Fowler. "At the very least he'll check up on me. I was going to suggest that we put up a candidate who'll stand some investigating. Then we'll be fairly safe. Nelson won't turn from the Party. But he might support the reform candidate at the primaries. And if we have a man who can stand an investigation, we can trump up some stuff on the reform man, and he'll pick our man to support. How about it?"

Pembroke laughed mirthlessly. "Who?" he asked, sarcastically.

Fowler was stumped. He thought the matter over for several minutes. But every time he seemed on the verge of deciding on some prominent leader, he either remembered some shady episode which might be uncovered, or he realized that the man wouldn't appeal to the public. Either drawback might well be fatal.

Pembroke finally broke the silence. "Your plan's no good," he said. "We'll have to stick to Danvers. He can beat the reform man with the help of Nelson's ward. Mr. Nelson will have to toe the line, or else!

"In fact maybe it would better if Mr. Nelson became temporarily indisposed. You might be able to swing his ward, if you work hard enough... Sure! That's the solution! You've always relayed his orders anyway. We can do without his speeches, as long as the committeemen think he's still directing things up at the fifty-second ward. I'll get in touch with Bonzetti right away!"

Fowler paled. "No, no," he exclaimed. "Not Bonzetti! After all, the lad's been like a son to me. Give me a chance to win him over."

Pembroke shook his head. "Fool!" he said. "My way is the best. Not only will it insure the election but you can put through your original estimate for your department. Any other way you lose your gravy."

It was to Fowler's credit that he didn't hesitate. "That don't mean anything," he said. "I got plenty. Try my way first. I'll win him over. Give me a chance."

Pembroke appeared to think the request over very carefully. "All right," he finally agreed. "I'll give you a week. But remember this: If you fail, Bonzetti pulls his snatch, and you take over. And don't think you can buck me, either. A twenty-year stretch wouldn't do you much good."

Fowler left the house with his brain ticking over at a furious rate. He didn't like the crafty look he'd seen in Pembroke's eyes. It would be just like him to string him along and then send Bonzetti out to snatch Nelson anyway. The boss had a reputation for refusing to play fair with anyone—unless playing fair happened to be to his advantage.

Fowler got in the taxi, but sat still for a minute before naming a destination.

Suddenly he jumped out and mounted the terrace at the side of Pembroke's house. He padded softly to the French windows of the room he had just quitted. Then he scurried back to the taxi and ordered speed, back to the club where he'd come from. The cab started out with a jolt which set his jowls to quivering madly. Pembroke had been earnestly talking to someone over the phone when he had looked in the windows. That could mean only one thing. The boss was living up to his reputation. He had only pretended to give Fowler a chance to win Nelson over, so that he wouldn't go immediately to warn him.

And unless Fowler moved quickly, Bonzetti would descend upon Harvey Nelson like a particularly malevolent ton of bricks.

HARVEY NELSON had another visitor at his table, almost as soon as Fowler left. A stocky man, homely, and friendly as a puppy.

"I'm Joe Patelli," he announced, grinned broadly. "I run this place. Mind if I pull up a chair for a second, Mr. Nelson?"

Harvey felt a vague sense of familiarity as he looked at the newcomer, but it didn't quite congeal into actual recognition. Joe Patelli, therefore, must be a constituent and worthy of his attention for that reason alone. Harvey felt a sense of duty toward constituents: one of the many things which set him apart as a politician. He nodded and smiled.

"This is Miss Forbes, my fiancée," he said.

Millicent raised a quizzical eye-brow, but said nothing. She was slightly stunned at the abruptness of it, and could only muster a smile as Patelli made a gallant remark about Harvey's taste.

"I'm in your ward, Mr. Nelson," he added, abruptly. "Do you mind telling me who we're going to put in, this election?"

Harvey's eyes narrowed momentarily. "It's a little early yet," he said. "Why?"

"Well," Patelli said slowly. "I got a chance to open a place in the suburbs. If I thought the reform crowd was goin' to get a hold in town, I'd do it. With the city closed tighter than a drum, a place just out of town would be a gold mine. On the other hand, it would be a waste of money if Danvers got the election. I can't run two places."

Harvey nodded. "You figure the reform crowd would be bad business, eh?"

"No doubt of it. They'd have the blue laws working in no time. You know that. Pembroke couldn't tell them what to do. It would be better if the opposition got in, meaning no offense. They'll at least play ball. But the reform crowd has got us all worried. They've almost got the Party split now. I figure it's all up to you."

"But the reform crowd wants to put a stop to vice and gambling," Millicent pointed out. "That's why they're getting so much support. People are getting tired of present conditions, according to the newspapers."

"According to the newspapers," jeered Patelli. "Lady, I'm in a position to know what I'm talking about, and that paper talk is a lot of malarkey. Right now the papers are short of news and they're making a whole lot of fuss about practically nothing, just to have something to print. As soon as somebody commits a nice, juicy murder, you won't read anything about gambling and vice."

Harvey said, "What do you mean by that?"

"Well, you know as well as me, Mr. Harvey, that there ain't any big-time gambling in town," Patelli said. "Pembroke's too greedy. As soon as an outfit begins to show a profit, he holds out his hand. They kick in for a while and then he raises the ante. First thing you know he takes all the profit out of it. And if they don't kick in, he closes them up.

"I ought to know. He drove me out of business when I had my joint. Glad he did, though. I'm making just as much here, and perfectly legitimate.

"This reform stuff is a lot of malarkey. Will it do any good to close me up? They can do it by shortening my business hours. That'll take away the profit. So what do I do? I open up again, just outside the city, and get the same trade anyway.

"Only I pay taxes to some thieving little borough on the edge of the town. That's going to help the city a lot, ain't it? Taxes will have to go up in other directions and more business leaves the town. It'll make a morgue out of this burg.

"It's nothin' to me, understand. I make money either way. I'd just like to know, so I could buy that place or turn it down."

HARVEY stared at Patelli for a long minute before he spoke. He was once more going through a phase of mental renovation. Fowler had always spoken in the highest terms of Mr. Pembroke: pictured him as being a man of the same lofty idealism as himself. According to Fowler he had been elected to leadership in the Party because of his unselfish devotion to the cause of bettering city government.

Harvey had never liked the man personally, but had blamed himself for the dislike. He had Fowler's word that he was of the finest character. And that had been enough. It was likely that if he didn't already know of the perfidy of Fowler, he would have called Patelli a liar on the spot.

But with the disturbing knowledge that nothing Fowler had ever told him was to be relied upon... And added to that was the fact that Patelli was obviously concerned only with his own welfare, and making no attempt to influence him.

"I think you'd better stay here," said Harvey, thoughtfully.

"You're going to throw the nomination to Danvers?"

"Don't quote me," said Harvey. "I merely said you'll do better staying here. I guarantee that."

Patelli leaned back in his chair, a puzzled look on his face.

"I don't know what you mean," he finally said. "But whatever it is, it's okay with me. I'll turn down that offer. Thanks, Mr. Nelson." Patelli left the table, his face wreathed in smiles.

"You're a regular politician," Millicent remarked. "You didn't tell him anything, and he's happy. What are you going to do?"

"I don't know," said Harvey miserably. "Let's get out of here. I've got to figure some things out. We'll take a ride in the park. All right?"

"Of course," agreed Millicent. "I'll help you figure. I'm your fiancée, you know. Though I think it's a heck of a way to propose. You didn't give me a chance to turn you down!"

Harvey's knees suddenly began to quake. "I thought—" he stammered. "After all—"

"Yes, I know," said Millicent, quietly. "You kissed me, and I didn't sock you. So that proves something, doesn't it?"

"Doesn't it?" he asked, vaguely.

"Yes, dear," she replied. "It does."

OMEGA showed no inclination to take charge as Harvey pulled away from the curb and headed toward the park. By the time they reached the river drive Harvey concluded that he must have fallen asleep, if shadows ever do sleep, and forgot about him.

"We made up our minds all of a sudden," he ventured as Millicent showed no inclination to open a conversation.

"Uh huh," Millicent agreed, patting him on the knee. "Except that I made mine up about three years before you did."

"Huh? Oh, no you didn't," he contradicted. "I made up my mind the instant I first saw you. It just took three years for me to tell you about it."

"Darling!" cried Millicent, almost wrecking the car as she flung her arms around his neck. Then she suddenly sobered. "But that's not what you want to talk about. Danvers is a crook, isn't he?"

Harvey covered half a mile before answering. Then: "I'm afraid he is," he replied. "Otherwise Pembroke wouldn't want him. At the very least, he's a man who will take the boss' orders. Which means graft in all the city departments, as well as the county ones."

"Harvey! Don't tell me there's graft in your department!"

"It's lousy with it," affirmed Harvey.

Millicent clapped her hands. "Then we'll have a honeymoon in Bermuda," she said.

Harvey's mouth popped open. "What? Wait a minute! I had nothing to do with the graft. Fowler collected it for himself and the Party. All I ever got was my salary. And that's all I want!"

"Oh," said Millicent, in a small voice.

"He's a chump!" said Omega, suddenly waking up, and speaking from the region of the windshield.

"What?" asked Millicent, absently adjusting herself to the idea of a graftless politician.

"He's a chump!" Omega repeated.

"He is not!" said Millicent, instantly jumping to the defense. "I think graft is horrible. Who said that, Harvey?"

"My shadow," Harvey explained. "I told you I was haunted. He's been with me for hours."

"I've been with you all your life," Omega remarked severely, "And a very dull existence it's been." Millicent gave a short gasp and held a hand over her mouth to stifle a scream. Shadow apparently didn't notice her fright, for he continued without a break. "Milly, you'll find it hard to believe, but this guy don't even know what the inside of a boudoir looks like! Not only that but..."

He rambled on for several minutes in the same vein, while Harvey scowled and kept his eyes glued to the road, and Millicent gradually got used to a voice speaking from thin air and settled down to listen interestedly.

"... And right now he's harboring some silly notion of making a deal with the reform gang, in which they're to promise to confine their activities to actual law breakers, such as gamblers and vice dealers, and to leave harmless night clubs and Sunday sports alone. He thinks that the noble reformers will keep promises. What a man!"

"I think he's nice," retorted Millicent. "He's good inside, and that's why he thinks everybody else is good. A person who suspects everybody else can't be very virtuous himself, or he wouldn't get such ideas. So there!"

"Virtue, phooey!" Omega exploded. "Who wants to be virtuous? What's it get you? Virtue is its own reward! It's got to be, says I. You can't have a good time on it. It cramps your style. Look at Horatio, here. He could be mayor by now, if he wasn't so damn virtuous. He's popular enough, but Pembroke knows he wouldn't stand for anything shady. So what is he? I ask you. What is he?"

Millicent looked at Harvey appraisingly. "What are you, darling?" she inquired.

"I'm a guy who's going to find some way of stepping on his shadow," Harvey growled. "He's getting to be a nuisance."

"Oh yeah?" exclaimed Omega with singular lack of originality.

Millicent, suddenly thinking of something, gave a short gasp. "I think he'll be worse than a nuisance," she told Harvey. "Especially after we're married."

Omega chuckled malevolently. "I'm staying," he said flatly. "I'm having lots of fun."

"You are," said Millicent. "But I'm not. Harvey! I just thought of something... Why not try to put Pembroke out of business? Find some evidence of his crooked work, and force him to let you dictate Party policies. Then you can support Danvers and everything will be sweetness and light!"

Harvey looked thoughtful, while Omega emitted a disgusted snort.

"It's an idea," Harvey said. "I'd like to do something to make up for the years that I've been running a crooked department. It'll be cleaned up from now on, of course, but I'd be really doing the city a service if I could clean house in other departments. I think..."

"How about Fowler?" asked Millicent. "He might know something you could hold over Pembroke's head. Or show you how to discover something."

Harvey was silent for several minutes. Then he slowed the car and reversed its direction.

"He might be able to help at that," he finally said. "Suppose we postpone the night's festivities until some other time. I'd like to go over some things in my files..."

"WHAT'S all this got to do with preventing the murder? It looks more like things are leading toward a murder, rather than away from one. The way Harvey used to be, he'd never have suspected that anything was wrong with the city's management. Now he's all set to monkey with things better left alone."

"Tut, tut. You are always the one who's trying to reform things. Wouldn't you like to see the taxpayer get a square deal?"

"Sure, sure. But Harvey isn't the one to start a reform. Don't forget he was a friend of mine. Went to the same schools together. I don't like to see you pushing him toward a peck of trouble."

"Don't be silly. He was due to be involved in a murder before I interfered. Therefore, anything I've done tends to influence later events so that either the murder won't happen, or Harvey won't be involved. Q.E.D. Don't forget that creek."

"Sounds logical," Mark admitted. "But it looks to me as if he's stretching out his neck."

THE telephone was emitting a discordant jangle when Harvey let himself into his apartment. It had been ringing for some time, for he had heard it when he opened the door at the bottom of the stairs. He snatched it up now.

The voice at the other end was so excited that he didn't recognize it at first. After a minute it became coherent and he realized that it was Fowler, urging him to lock and barricade his door and wait until he arrived.

Harvey hung up, quite puzzled, but didn't bother to barricade the door. He did, however, turn out the lights and wait by the window. Nobody could enter the building without being seen from that vantage point.

Less than ten minutes passed when a taxi roared down the street and slid to a stop in front of the door. Fowler bounced out of the rear, stuffed bills into the driver's hand, and dashed for the door. Harvey let him in, whereupon he slumped in a chair to get his breath.

"What's the trouble?" Harvey, asked. "You're puffing as if you'd ran over here, instead of riding."

Fowler's respiration slowly returned to normal. "Thank God I've found you, boy. I've been chasing all over town for you. You're in grave danger!"

Harvey listened attentively as Fowler told of his interview with Pembroke, and of seeing him telephoning. "He was calling Bonzetti, sure as you're born," Fowler finished. "And it won't end with just kidnapping. Bonzetti will have to protect himself by killing you and disposing of your body in such a way that it will never be found. You've got to be on guard every minute!"

Harvey was silent for several minutes. Fowler was obviously terrified—which meant that regardless of his petty thievery and deceit in the past, he was still Harvey's friend. Nelson's scale of values underwent another sudden revision. For Fowler wasn't a man of great physical courage; yet he had knowingly risked...

"Jim," he said. "How would you like to be mayor?"

"Boy! You're delirious. Can't you understand that you're in danger? We've got to hire a bodyguard. One for me, too," he added.

"There isn't a single reason why you shouldn't be mayor. You've spent all your life in the service of this city. You've proven yourself to be a man of deep-seated integrity, and only interested in the public welfare. You've given unstintedly of your time..."

Fowler's eyes were assuming a decided poppish aspect. "Cut it out, son," he said. "There's no use being sarcastic."

"I'm talking about what the voters know to be a fact," Harvey explained. "Who knows any different?"

FOWLER looked a bit sad. "Pembroke," he answered. "He knows enough to put me behind bars. Though of course I've put away enough money to pay for good lawyers. I might get out with a light sentence or maybe none at all. But that would leave me broke. And Pembroke would hand over the evidence, the minute he found I was bucking him. He may anyway, if he thinks I've spilled to you."

"Don't you have anything on him?"

"Same stuff he has on me," replied Fowler. "Graft; diversion of public funds, and all that. But he's got it on me in black and white. All I could do would be to holler, and he'd cover himself with his control of the courts. Don't forget he owns a newspaper, too. He'd whitewash himself thoroughly, saying that I was trying to get revenge with my wild accusations."

"He won't come out with that evidence," Harvey stated. "I've got something that'll stop him. And he can't white-wash himself with Uncle Sam. He's an accessory to kidnapping, and that's a federal offense, with a death penalty attached."

Fowler's eyes popped and he sputtered futilely. It was almost a minute before he could speak coherently. "Have you gone nuts?" he finally exploded. "You can't prove an accessory before the fact, when the fact hasn't happened!"

Harvey nodded. "Before and after," he stated. "Because that kidnapping is going to happen."

Fowler groaned as he saw the lines of Nelson's jaw harden, and saw what was in his mind. "Boy, boy," he wailed. "Don't do anything so foolish. Bonzetti isn't any amateur. He's thorough and efficient."

Harvey snorted. "A petty gangster," he pronounced. "I'll be ready for him. And when he kidnaps me, I'll get a confession out of him, naming Pembroke. We'll use that as a lever to elect you. Then we'll clean up the city departments until they shine."

"THAT'S him, all right," Mark groaned. "Afraid of nothing and silly enough to buck any odds to uphold a principle. He hasn't changed a bit!"

Omega's mental voice was a bit dubious. "Hasn't changed... Oh yes he has. He's suspicious now. He used to be gullible. That's bound to change things. They won't happen as they would have."

"Of course they won't! He'll get murdered himself, instead of just being suspected of one!"

"Aw, quit worrying. I won't let anything happen to him."

FOWLER shook his head miserably. "It won't work," he said. "You'll never get away, once Bonzetti gets hold of you. He's dangerous, I tell you."

Nelson smiled confidently. "He never kidnapped me," he said. "Listen, Jim. We'd better make sure that this really happens. As it stands now, it's merely guesswork, based on a phone call you didn't hear. Suppose we tell Pembroke we intend to run you on an independent ticket. Knowing that without the fifty-second ward he can't hope to elect Danvers, he's sure to put Bonzetti to work. That's it! Call for me about nine in the morning."

Fowler left, a scared and puzzled man. He couldn't reconcile this new Nelson with the man he had always been able to wrap around his finger with a smooth line of chatter. Now Harvey Nelson was taking the initiative, ordering him around!

LIGHT streamed through the window when Harvey awakened, and the angle indicated that the morning was well on its way. Harvey blinked and tried to get his thoughts into focus. He was looking at the ceiling while so occupied, and hence didn't notice for some minutes that he wasn't alone.

"I'm surprised at you," said a voice which he recognized immediately as being his own, which meant that it was Omega's. "Going out of your way to get us kidnapped."

"What do you mean?" Harvey began, then stopped in amazement. He had involuntarily faced the direction of the voice, and was shocked grievously as a result. For Omega seemed to have taken solid form!

Harvey looked for several seconds before he realized the truth of the situation. Omega was sitting on a chair, clad in a neat blue serge suit, fawn-colored gloves, gray socks and brown shoes. White shirt and a brown tie with yellow stripes—something Harvey had been given for Christmas—completed the outfit.

Aside from the clashing colors there was only one thing wrong with the picture—the face. The face, in fact the whole bead, was that of a ferocious Indian of the old Wild West!

Harvey stared at it for some time before he recognized it. Probably that was because the bronzed neck protruded from one of Harvey's own collars, and the feathered headdress had been broken off and the shaven scalp covered by his favorite derby; for Harvey had seen that face a thousand times. It had, in fact, stared at him inscrutably every day for the past ten years. The face belonged to a life-sized clay bust of an Indian brave, and had adorned his mantlepiece ever since he had taken this apartment.

Harvey realized that Omega's impalpable presence had merely occupied the assorted articles of clothing, holding them—and the outraged bust—in then-proper positions. There was only one puzzling factor.

"How can you be over there?" he asked, looking behind him in the bed. "The light's casting you against the headboard."

"I've been practicing," said Omega cheerfully, getting up and walking back and forth. "I found that I'm also cast in a dozen directions by reflected ultra-violet rays. They're also light waves, you know, though quite invisible. It seems that I'm free to move about quite a bit, as long as I don't get too—Oops!"

The Indian's head suddenly fell through the suit of clothes and landed with a dull thud on the floor. This happened when Omega approached the opposite wall, some fifteen feet from Harvey. "Too far away," he continued. "I've been practicing walking for the last hour. Thought I'd better let you sleep."

As he talked, the clothes and the Indian head jerked themselves closer to the bed and laboriously rearranged themselves.

"Take it easy with that suit," Harvey cautioned. "It cost me fifty dollars. Say! I hope you don't intend to go around with me in that rig!"