RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

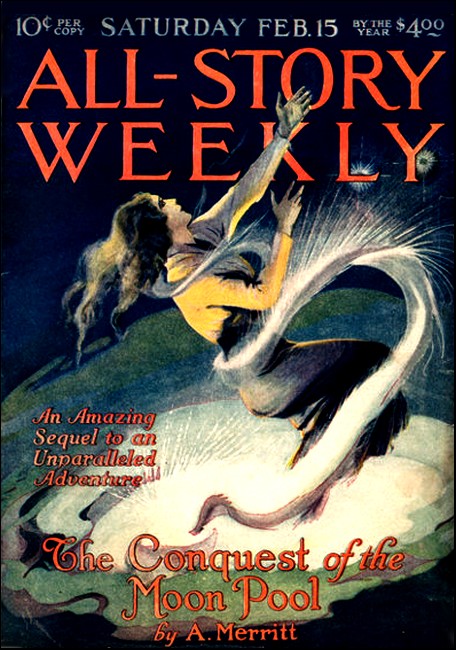

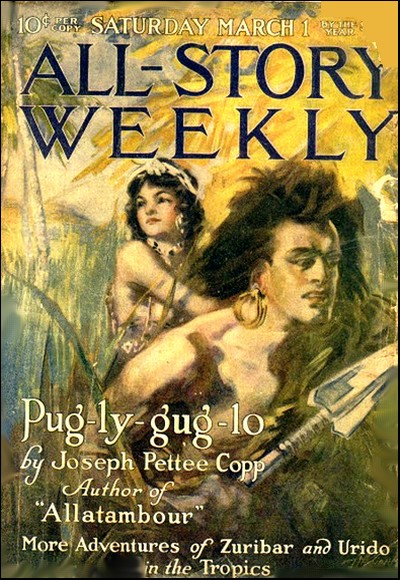

All-Story Weekly, June 22, 1918,

with first part of "The Conquest of the Moon Pool"

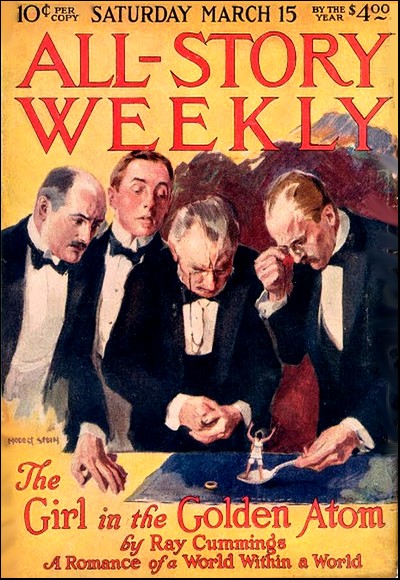

All-Story Weekly, with parts 2 to 5 of "The Conquest of the Moon Pool"

Beauty incomparable—devilish malignity

unspeakable—

what dread secret lay in wait in the lair of the Shining One?

AS I begin this narrative, I find it necessary to refer, briefly, to my original recital which appeared under the title of "The Moon Pool," of the causes that led me into the adventure of which it is to be the history. The adventure which would forge the last links in 'the chain to bind the Dweller.

I have told you of that dread night on the Southern Queen, when the monstrous,' shining Thing of living light and mingled rapture and horror embraced Throckmartin and drew him from his cabin down the moon path to its lair beneath the Moon Pool. I had promised him I would solve the mystery. But I had delayed keeping this promise for three years, believing nothing could really be done, and fearing my story would not be believed. At last, however, remorse drove me into action.

Had I set forth for that group of Southern Pacific islets called the Nan-Matal, where the Moon Pool lay hidden, a day before or after, I would not have found Olaf Huldricksson, hands lashed to the wheel of his ravished Brunhilda, steering it even in his sleep down the track of the Dweller. Olaf whose wife and babe the Dweller had snatched from him. Nor would I have picked up Larry O'Keefe from the wreck of his flying boat fast sinking under the long swells of the Pacific. And without O'Keefe and Huldricksson that weird and almost unthinkably fantastic drama enacted beyond the Moon Pool's gates must have had a very different curtain.

The remorse of a botanist, the burning, bitter hatred of a Norse seaman, the breaking of a wire in a flying-boat's wing—all these meeting at one fleeting moment formed the slender tripod upon which rested the fate of humanity! Could that universal irony which seems to mold our fortunes go further?

But there they were O'Keefe and Huldricksson and I; Larry O'Keefe and Olaf Huldricksson and I, and Lakla of the flower face and wide, golden eyes. Lakla the Handmaiden of the Silent Ones, and the Three who had fashioned the Dweller from earth's secret heart—each thread in its place.

And so humanity lives!

And now let me recall to those who read my first narrative, and make plain to those who did not, what it was that took me on my quest; the enigmatic prelude in which the Dweller first tried its growing power.

You will remember that Dr. David Throckmartin, one of America's leaders in archeological and ethnological research, had set out for the Caroline Islands, accompanied by his young wife, Edith, his equally youthful associate, Dr. Charles Stanton, and Mrs. Throckmartin's nurse from babyhood, Thora Helverson.

Their destination was that extraordinary cluster of artificially squared, basalt-walled islets off the eastern coast of Ponape, the largest Caroline Island, known as the Nan-Matal. It was Throckmartin's belief that in those prehistoric ruins lay the clue to the lost and highly civilized race which had peopled that ancient continent, which, sinking beneath the waters of the pacific, Atlantis-like, had left in the islands we call Polynesia only its highest peaks.

Dr. Throckmartin planned to spend a year on the Nan-Matal, hoping that within its shattered temples and terraces, its vaults and cyclopean walls, or in the maze of secret tunnels that running under the sea threaded together the isles, he would recover not only a lost page of the history of our races, but also, perhaps, a knowledge that had vanished with it.

The subsequent date of this expedition formed what became known as the Throckmartin mystery. Three months after the little party had landed at Ponape, and had been accompanied to the ruins by a score of reluctant native workmen—reluctant because all the islanders shun the Nan-Matal as a haunted place—Dr. Throckmartin appeared alone at Port Moresby, Papua.

There he said that he was going to Melbourne to employ some white workmen to help him in his excavations, the superstitions of the natives making their usefulness negligible. He took passage on the Southern Queen, sailing the same day that he appeared, and three nights later he vanished utterly from that vessel.

It was officially reported that he had either fallen from the ship or had thrown himself overboard. A relief party sent to the Nan-Matal for the others in his, party, found no trace of his wife, of Stanton, or of Thora Helverson. The native workmen, questioned, said that on the nights of the full moon the ani or spirits of the ruins had great power. That on these nights no Ponapean would go within sight or sound of them, and that by agreement with Throckmartin they had been allowed to return to their homes on these nights, leaving the expedition "to face the spirits alone."

AFTER the full of the moon on the third month of the

expedition's stay, the natives had returned to the Throckmartin

camp only to find it deserted. And then, "knowing that the

ani had been stronger," they had fled.

I had been a passenger with Throckmartin on the Southern Queen. I had been with him when that wondrous horror which had followed him down the moon path after it had set its unholy seal upon him had snatched him from the vessel. He had told me his story, and I had promised, Heaven forgive me, that if the Dweller took him as it had taken his wife and Stanton and Thora, I would follow.

He had told me his story, and I knew that story was true—for twice I had seen the inexplicable power which Throckmartin, discovering, had loosed upon himself and those who loved him. That unearthly Thing which left on the faces of its prey soul-deep lines of mingled agony and rapture, of joy celestial and misery infernal, side by side, as though the hand of God and the hand of Satan working in harmony had etched them!

I first beheld the Dweller on that first night out from Papua when it came racing to claim Throckmartin.

We two were on the upper deck. He had not yet summoned the courage to tell me of what had befallen him. Storm threatened but suddenly, far to the north, the clouds parted, and upon the waters far away the moon shone.

Swiftly the break in the high-flung canopies advanced toward us and the silver rapids of the moon stream between them came racing down toward the Southern Queen like a gigantic, shining serpent writhing over the rim of the world. And down its shimmering length a pillared radiance sped. It reached the barrier of blackness that still held between the ship and the head of the moon stream and beat against it with a swirling of shimmering misty plumes, throbbing lacy opalescences and vaporous spiralings of living light.

Then, as the protecting shadow grew less, I saw that within the pillar was a core, a nucleus of intense light—veined, opalescent, vital. And through gusts of tinkling music came a murmuring cry as of a calling from another sphere, making soul and body shrink from it irresistibly and reach toward it with an infinite longing. "Av-o-lo-ha! Av-o-lo-ha!" it sighed.

Straight toward the radiant vision walked Throckmartin, his face transformed from all human semblance by unholy blending of agony and rapture that had fallen over it like a mask. And then—the clouds closed, the moon path was blotted out, and where the shining Thing had been was—nothing!

What had been there was the Dweller!

It was after I had beheld that apparition that Throckmartin told me what would have been, save for what my own eyes had seen, his incredible story. How, upon a first night of the full moon, camping on another shore, they had seen lights moving on the outer bulwarks of that islet of the Nan-Matal, called Nan-Tanach, the "place of frowning walls," and faintly to them over the waters had crept the crystalline music, while far beneath, as though from vast distant caverns, a mighty muffled chanting had risen. How, on going to Nan-Tanach next day, they had found set within the inner of its three titanic terraces, a slab of stone, gray and cold and strangely repellent to the touch. Above it and on each side was a rounded breast of basalt in each of which were seven little circles that gave to the hand that same alien shock, "as of frozen electricity," that contact with the gray slab gave.

And that night, when sleep had seemed to drop down upon them from the moon, but before the sleep had conquered him, he had seen the court of the gray rock curdle with light. Into it had walked Thora, bathed and filled with a pulsing effulgence beside which all earthly light was shadow!

He told me of their search for Thora at dawn, when the slumber had fallen from their eyes, and of their discovery of her kerchief caught beneath the lintel of the gray slab, betraying that it had opened, and opening, closed upon her. Of their efforts to force it, and of the vigil that night when Stanton was taken and walked "like a corpse in which flamed a god and a devil" in the embrace of the Dweller upon the shattered walls of Tanach, vanishing at last through the moon door, even as had Thora. And the muffled, distant, mighty chanting as of a multitude that hailed his passage.

After that, of the third night, when his wife and he watched despairingly beside the moon door, waiting for it to open, hoping to surprise the shining Thing that came through it, and surprising, conquer it. Of their wait until the moon swam up and its full light shone upon the terrace. Of the sudden gleaming out of the little circles under its rays and of the sighing murmur of the moon door, swinging open as its hidden mechanism responded to the force of the light falling on the circles. And of his mad rush down the glimmering passage beyond the moon-door portal to the threshold of the wondrous chamber of the Moon Pool.

ABSORBED, silent, marveling, I listened as he described that

place of mystery—a vaulted arch that seemed to open into

space; a space filled with lambent, coruscating, many-colored

mist whose brightness grew even as he watched; before him an

awesome pool, circular, perhaps twenty feet wide. Around it a

low, softly curving lip of glimmering, silvery stone. The pool's

water was palest blue. Within its silvery rim it was like a

great, blue eye staring upward.

Upon it streamed seven shafts of radiance.

They poured down upon it like torrents; they were like shining pillars of light rising from a sapphire floor. One was the tender pink of the pearl; one of the aurora's green; a third a deathly white; the fourth the blue in mother-of-pearl; a shimmering column of pale amber; a beam of amethyst; a shaft of molten silver. The pool drank them!

And even as Throckmartin gazed, he saw run through the blue water tiny gleams of phosphorescence, sparkles and coruscations of pale incandescence, and far, far down in its depths he sensed a movement, a shifting gleam as of some radiant body slowly rising.

Mists then began to float up from the surface, tiny swirls that held and hung in the splendor of the seven shafts, absorbing their glory and at last coalescing into the shape I had seen and that he called the Dweller.

He had raised his pistol and sent bullet after bullet into it. And as he did so, out from it swept a gleaming tentacle. It caught him above the heart; wrapped itself round him. Over him rushed a mingled ecstasy and horror. It was, he said, as though the cold soul of evil and the burning soul of good had stepped together within him.

He saw that the shining nucleus of that which he had watched shape itself from vapors and light had form—but a form that eyes and brain could not define; as though a being of another world should assume what it might of human semblance, but could not hide that what human eyes saw was still only a part of it. It was neither man nor woman; it was unearthly and androgynous and even as he found its human semblance, that semblance changed, while all the while every atom of him thrilled with interwoven rapture and terror.

Behind him he had heard the swift feet of his wife, racing to his aid. Love gave him power, and he wrested himself from the Dweller. Even as he did so he fell, and saw her rush straight into the radiant glory! Saw, too, the Dweller swiftly wrap its shining mists around her and draw her over the lip of the pool; dragged himself to the verge and watched her sink in its embrace, down, down through the depths—"a shining, many-colored, nebulous cloud, and in it Edith's face, disappearing, her eyes staring up at me filled with ecstasy supernal and infernal horror—and—vanished!"

Then, far below, again the triumphant chanting!

There had come to Throckmartin madness. He had memory of running wildly through glimmering passages; then blackness and oblivion until he found himself far out at sea in the little boat they had used to cruise around the lagoons of the Nan-Matal. He had bribed the half-caste captain of a ship that picked him up to take him to Port Moresby, from whence he intended to go to Melbourne, hoping to find some who would return with him, force the haunted chamber, and battle with him against the Dweller.

And oh that third night I cowered in the corner of his cabin and saw the Dweller take him!

For three years I was silent, and then, obeying a sudden, irresistible impulse, I started, alone, for the Nan-Matal to make reparation. For Throckmartin had not entirely believed that his wife was dead, nor Stanton nor Thora; rather he thought that they might be held in some unearthly bondage.

And he had, too, a vague belief that the deep, underground chantings that had accompanied the disappearance of the Dweller with its victims, pointing clearly as they did to the existence of other beings or powers in its mysterious den, held a vast threat against humanity. How true was his scientific clairvoyance, and yet how far from the amazing, unthinkable truth, you are to learn. It was my own conviction that in both he had been right; and it was this conviction which now forced me onward at all speed toward the Carolines.

I delayed my departure from America only long enough to get certain instruments and apparatus that long brooding over the phenomena had suggested might be useful in coping with them.

Nine weeks later, with my paraphernalia, I was northward bound from Port Moresby on the Suwarna, a swift little copra sloop with a fifty-horse-power motor auxiliary, and heading for Ponape—for the Nan-Matal and the Chamber of the Moon Pool and all that it held for me of soul-shaking awe and peril.

WE sighted the Brunhilda some five hundred miles south

of Ponape. Soon after we had left Port Moresby the wind had

fallen, but the Suwarna, although far from being as

fragrant as the Javan flower for which she was named, could do

her twelve knots an hour. Da Costa, the captain, was a garrulous

Portuguese. The crew were six huge, chattering Tonga boys.

The Suwarna had cut through Finschafen Huon Gulf to the protection of the Bismarcks, and we were rolling over the thousand-mile stretch of open ocean with New Hanover far behind us and our boat's bow pointed straight toward Nukuor of the Monte Verdes. After we had rounded Nukuor we should, barring accident, reach Ponape in not more than sixty hours.

Beneath us the slow, prodigious swells of the Pacific lifted us in gentle, giant hands and sent us as gently down the long, blue wave slopes to the next broad, upward slope. There was a spell of peace over the ocean that was semihypnotic, stilling even the Portuguese captain who stood dreamily at the wheel, slowly swaying to the rhythmic lift and fall of the sloop.

There came a whining hail from the Tonga boy lookout draped lazily over the bow.

"Sail he b'long port side!"

Da Costa straightened and gazed while I raised my glass. The vessel was a scant mile away, and must have been visible long before the sleepy watcher had seen her. She was a sloop about the size of the Suwarna, without power. All sails set, even to a spinnaker she carried, she was making the best of the little breeze. I tried to read her name, but the vessel jibed sharply as though the hands of the man at the wheel had suddenly dropped the helm—and then with equal abruptness swung back to her course. The stern came In sight, and on it I read Brunhilda.

"Something veree wrong I think there, sair," the Portuguese said in his curious English. "The man on deck I know. He is captain and owner of the Br-rwun'ild. His name Olaf Huldricksson, what you say—Norwegian. He is eithair veree sick or veree tired, but I do not understand where is the crew and the starb'd boat is gone."

We were now nearly abreast and a scant five hundred yards away. The engine of the Suwarna died and the Tonga boys leaped to one of the boats.

"You Olaf Huldricksson!" shouted Da Costa. "What's a matter wit' you?"

"Wait!" I cried. I ran into my cabin, grasped my emergency medical kit and climbed down the rope ladder. The two Tonga boys bent to the oars. We reached the side and Da Costa and I each seized a lanyard dangling from the stays and swung ourselves swiftly on board. Da Costa approached Huldricksson softly.

"What's the matter, Olaf?" he began and then was silent, looking down at the wheel. My gaze followed his and we shrank together involuntarily. For the hands of Huldricksson were lashed fast to the spokes of the wheel by thongs of thin, strong cord. They had been bound so tightly that they were swollen and black. The thongs had bitten so into the sinewy wrists that they were hidden in the outraged flesh, cutting so deeply that blood fell, slow drop by drop, at his feet. We sprang toward him, reaching out hands to his fetters to loose them. Even as we touched them, Huldricksson grew rigid with anger that had in it something diabolic. He aimed a vicious kick at me and then another at Da Costa which sent the Portuguese tumbling into the scuppers.

"Let be!" croaked Huldricksson; his voice was as thick and lifeless as though forced from a dead throat, and I saw that his lips were cracked and dry and his parched tongue was black. "Let be! Go! Let be!" The words beat upon the ears heavily, painfully. It was the dead alive and speaking!

"I go below," said Da Costa nervously. "His wife, his little Freda, they are always wit' him. You wait." He darted down the companionway and was gone. Huldricksson suddenly was silent, slumping down over the wheel, forgetting us.

Da Costa's head appeared at the top of the companion steps.

"There is nobody, nobody," he said. "I do not understan'."

Then Olaf Huldricksson opened his dry lips again and as he spoke a thrill ran though me, stopping my heart.

"The sparkling devil took them!" croaked Olaf Huldricksson. "The sparkling devil took them! Took my Helma and my little Freda! The sparkling devil came down from the moon and took them!"

It was with utmost difficulty that we loosed the thongs, but at last it was done.

WE rigged a little swing and the Tonga boys slung the great

inert body over the side into the dory. Soon we had Huldricksson

in my bunk. De Costa sent half his crew over to the sloop in

charge of the Cantonese. They took in all sail, stripping

Huldricksson's boat to the masts and then with the

Brunhilda nosing quietly along after us at the end of a

long hawser, one of the Tonga boys at her wheel, we re-resumed

our way.

Suddenly I was aware of Da Costa's presence and turned. His unease was manifest and held, it seemed to me, a queer, furtive anxiety.

"What you think of Olaf, sair?" he asked. I shrugged my shoulders. "You think he killed his woman and his babee?" he went on. "You think he crazee and killed all?"

"Nonsense, Da Costa," I answered. "You saw the boat was gone. His crew mutinied and tied him up the way that you saw."

Da Costa shook his head slowly. "No," he said. "No. The crew did not. Nobody there on board when Olaf was tied."

"What!" I cried, startled. "What do you mean?"

"I mean," he said slowly, "that Olaf tie himself!"

I bent over the sleeper. On his face was no trace of that unholy mingling of opposites, of mingled joy and fear, that the Dweller stamped upon its victims. But with Da Costa's revelations the security I had felt in my theory of the prisoned wrists crumbled. Huldricksson's words came back to me—"The sparkling devil took them!" Nay, they had been even more explicit—"The sparkling devil that came down from the moon!"

They sank upon my heart like weights, carrying subconscious conviction that resisted all my efforts to dismiss. I lifted the sheet from Huldricksson and went over his body minutely, turning it from side to side. The Norseman was, as I have said, a giant, and his mighty, muscled form was clean and white as a girl's. Nowhere was there a trace of that cold, white stain which was the mark of the touch of the Dweller and that had been, on Throckmartin, a shining cincture girdling the body just below the heart.

Throckmartin had believed, and I had believed with him, that the thing I had gone forth to find had no power outside the islet of the moon door and that it was only by virtue of that mark it had been enabled to follow him. But was this true? Huldricksson had been steering straight for Ponape, not away from it—and there was no trace of the Nan-Matal's dread mystery upon him.

As I sat thinking, the cabin grew suddenly dark, and from above came a shouting and patter of feet. Down upon us swept one of the abrupt, violent squalls that are met with in those latitudes. I lashed Huldricksson fast in the berth and ran up on deck.

A half hour passed. Then the squall died as quickly as it had arisen. The sea quieted. Over in the west, from beneath the tattered, flying edge of the storm, dropped the setting sun.

I watched it, and rubbed my eyes and stared again. For over its flaming, portal something huge and black moved, like a gigantic beckoning finger!

Da Costa had seen it, too, and he turned the Suwarna straight toward the descending orb and its strange shadows. As we approached we saw it was a little mass of wreckage and that the beckoning finger was a wing of canvas, sticking up and swaying with the motion of the waves. On the highest point of the wreckage sat a tall figure calmly smoking a cigarette.

We brought the Suwarna to, dropped a boat, and with myself as coxswain pulled toward what I knew now was a wrecked hydroplane. Its occupant took a long puff at his cigarette, waved a cheerful hand, and shouted a reassuring greeting. And just as he did so a great wave raised itself up behind him, took the wreckage, tossed it high in a swelter of foam, and passed on. When we had steadied our boat, where wreck and man had been was—nothing.

I scanned the water with anxious eyes. Who had been this debonair castaway, and from whence in these far seas had dropped his plane? There came a tug at the side of our boat, two muscular brown hands gripped it close to my left, and a sleek, black, wet head showed its top between them. Two bright blue eyes that held deep within them a laughing deviltry looked into mine, and a long, lithe body drew itself gently over the thwart and seated its dripping self at my feet.

"Much obliged," said this man from the sea. "I knew somebody was sure to come along when the O'Keefe banshee didn't show up."

"The what?" I asked in amazement.

"The O'Keefe banshee. Oh, yes, pardon me, I'm Larry O'Keefe. It's a far way from Ireland, but not too far for the O'Keefe banshee to travel if the O'Keefe was going to kick in."

I looked again at my astonishing rescue. He seemed perfectly serious, and later I was to know how exasperatingly, naïvely, and entirely serious he was on that subject.

"Have you a cigarette?" said Larry O'Keefe. "Mine went out," he added with a grin, as he reached a moist hand out for the little cylinder, took it, lighted it on the match I struck for him, and then gazed at me frankly and with manifest curiosity. I returned the gaze as frankly.

I saw a lean, intelligent face whose fighting jaw was softened by the wistfulness of the clean-cut lips and the roguishness that lay side by side with the deviltry in the laughing blue eyes. Nose of a thoroughbred with the suspicion of a tilt. A long, well-knit, slender figure that I knew must have all the strength of fine steel; the uniform of a lieutenant in the Royal Flying Corps of Britain's navy.

He laughed, stretched out a firm hand, and gripped mine.

"Thank you ever so much, old man."

I liked Larry O'Keefe from the beginning, but I did not dream how that liking was to be forged into man's strong love for man by fires which souls such as his and mine—and yours who read this—could never dream.

Larry! Larry O'Keefe, where are you now with your leprechauns and banshee, your heart of a child, your laughing blue eyes, and your fearless soul? Shall I ever see you again, Larry O'Keefe, dear to me as some best-beloved younger brother? Larry!

PRESSING back the questions I longed to ask, I introduced myself.

A second later we touched the side of the Suwarna, and I was forced to curb my curiosity until we reached the deck. Da Costa greeted us eagerly, and was plainly gratified by the military salute which O'Keefe bestowed upon him.

"You haven't seen a German boat called the Wolf about, have you?" he asked with a grin, after he had elaborately thanked the bowing little Portuguese skipper for his rescue. "That thing you saw me sitting on was all that was left of one of His Majesty's best little hydroplanes after that cyclone threw it off as excess baggage. And by the way, about where are we?"

Da Costa gave him our approximate position from the noon reckoning.

O'Keefe whistled. "A good three hundred miles from where I left the H. M. S. Dolphin about four hours ago," he said. "That squall I rode in on was some whizzer!

"About an hour ago I thought I saw a chance to dig up and out of it. I turned, and blink went my upper right wing, and down I dropped. Engine began to work lose, and just as I knew something had to come along quick or the banshee of the O'Keefes was due for a long, swift trip from Ireland, I sighted you."

He hesitated. "Where are you bound, by the way?" he asked.

"For Ponape," I answered.

"No wireless there," mused O'Keefe. "Beastly hole. Stopped a week ago for fruit. Natives seemed scared to death at us—or something. What are you going there for?"

I saw Da Costa dart a furtive glance at me. It troubled me. I had, of course, told him nothing of the real reasons for my journey, stating simply, when I had employed him, that I wished to go to Ponape where the scientific work I had planned might keep me many weeks. What did the man know, I wondered, and what was the explanation of his remarks in the cabin and of his manifest unease? O'Keefe's sharp eyes had noted the glance and, misinterpreting it and my consequent hesitation, flushed in embarrassment.

"Oh, I beg your pardon," he said. "Maybe I oughtn't to have asked that?"

"It's no secret, lieutenant," I replied, somewhat testily. "I'm about to undertake some exploration work there. A little digging among the ruins on the Nan-Matal."

I looked at the Portuguese sharply as I named the place. I distinctly saw a pallor creep under his skin and then he made swiftly the sign of the cross, glancing as he did so uneasily to the north. I made up my mind then to question him when opportunity came. He turned from his quick scrutiny of the sea and addressed O'Keefe.

"There's nothing on board to fit you, lieutenant," he said, looking over the tall figure before him. "But perhaps we can find something while your clothes dry. Will you come to my cabin?"

"Oh, just give me a sheet to throw around me, captain," said O'Keefe, following him. Darkness had fallen, and as the two disappeared I softly opened the door of my own cabin and listened. I could hear Huldricksson breathing deeply.

I drew my electric flash, and shielding its rays from my face, looked at him. His sleeping was changing from the heavy stupor of the drug into one that was at least on the borderland of the normal. Satisfied as to his condition, I returned to deck.

O'Keefe was there on deck, looking like a specter in the cotton sheet he had wrapped about him. A deck table had been cleated down and one of the Tonga boys was setting it for our dinner. Soon the very creditable larder of the Suwarna dressed the board, and O'Keefe, Da Costa and I attacked it. The night had grown close and oppressive. Behind us the forward light of the Brunhilda glided and the binnacle lamp threw up a faint glow in which her black helmsman's face stood out mistily. O'Keefe had looked curiously a number of times at our tow, but had asked no questions.

"You're not the only passenger we picked up today," I told him. "We found the captain of that sloop, lashed to his wheel, nearly dead with exhaustion, and his boat deserted by every one except himself."

"What was the matter?" asked O'Keefe in astonishment.

"We don't know," I answered. "He fought us, and I had to drug him before we could get him loose from his lashings. He's sleeping down in my berth now. His wife and little girl ought to have been on board, the captain here says, but—they weren't."

"Any signs of there being a fight?" asked O'Keefe.

I shook my head, and again I saw Da Costa swiftly cross himself. "We'll have to wait until he wakes up to get the story," I concluded.

DA COSTA at last relieved the Cantonese at the wheel. O'Keefe

and I drew chairs up to the rail. The brighter stars shone out

dimly through a hazy sky. "Are you American or Irish, O'Keefe?" I

asked suddenly.

"Why?" he laughed.

"Because," I answered, "from your name and your service I would suppose you Irish, but your command of pure Americanese makes me doubtful."

He grinned amiably.

"I'll tell you how that is," he said. "My mother is an American—a Grace, of Virginia. My father was O'Keefe, of Coleraine. And these two loved each other so well that, the heart they gave me is half Irish and half American. My father died when I was sixteen. I used to go to the States with my mother every other year for a month or two. But after my father died we used to go to Ireland every other year. And there you are. I'm as American as I am Irish.

"When I'm in love, or excited, or dreaming, or mad I have the brogue. But for the every-day purposes of life I like the United States talk, and I know Broadway as well as I do Binevenagh Lane, and the Sound as well as St. Patrick's Channel. Educated a bit at Eton, a bit at Oxford, a bit at Harvard. Always too much O'Keefe with Grace money to have to make any. In love lots of times, and never a heartache after that wasn't a pleasant one, and never a real purpose in life until I took the king's shilling and earned my wings; always ready for adventure—Larry O'Keefe."

"But it was the Irish O'Keefe who sat out there waiting for the banshee," I laughed.

"It was that," he said somberly, and I heard the brogue creep over his voice like velvet and his eyes grew brooding again. "There's never an O'Keefe for these thousand years that has passed without his warning. An' twice have I heard the banshee calling—once it was when my younger brother died an' once when my father lay waiting to be carried out on the ebb tide."

He mused a moment, then went on: "Ah' once I saw an Annir Choille, a girl of the green people, flit like a shadow of green fire through the Carntogher woods, an' once at Dunchraig I slept where the ashes of the Dun of Cormac MacConcobar are mixed with those of Cormac an' Eilidh the Fair, all burned in the nine flames that sprang from the harping of Cravetheen, an' I heard the echo of his dead harpings—"

There was a little silence. I looked upon him with wonder. Clearly he was in deepest earnest. I know the psychology of the Gael is a curious one and that deep in all their hearts their ancient tradition and beliefs have strong and living roots.

"You can't make me see what you've seen, lieutenant," I laughed. "But you can make me hear. I've always wondered what kind of a noise a disembodied spirit could possibly make without any vocal cords or breach or any other earthly sound-producing mechanism. How does the banshee sound?"

"O'Keefe did not laugh.

"All right," he said. "I'll show you." From deep down in his throat came first a low, weird sobbing that mounted steadily into a keening whose mournfulness made my skin creep. And then O'Keefe's hand shot out and gripped my shoulder, and I stiffened like stone in my chair—for from behind us, like an echo, and then taking up the cry, swelled a wail that seemed to hold within it a sublimation of the sorrows of centuries! It gathered itself into one heartbroken, sobbing note and died away! O'Keefe's grip loosened, and he rose swifty to his feet.

"It's all right, Goodwin," he said. "It's for me. It found me, all this way from Ireland."

There was no trace of fear in face or voice. "Buck up, professor," laughed O'Keefe. "There's nothing for you to he afraid of. And never yet was there an O'Keefe who feared the kind spirit that carries the warnin'."

Again the silence was rent by the cry. But now I had located it. It came from my room, and it could mean only one thing. Huldricksson had wakened.

"Forget your banshee!" I gasped, and made a jump for the cabin.

OUT OF the corner of my eye I noted a look of half-sheepish

relief flit over O'Keefe's face, and then he was beside me. Da

Costa shouted an order from the wheel, the Cantonese ran up and

took it from his hands and the little Portuguese pattered down

toward us. My hand on the door, ready to throw it open, I

stopped. What if the Dweller were within? What if the new power I

feared it had attained had made it not only independent of place

but independent of that full flood of moon ray which Throckmartin

had thought essential to draw it from the blue pool!

The Portuguese had paused, too, and looking at him I saw my own cravenness reflected. Now, from within, the sobbing wail began once more to rise. O'Keefe pushed me aside and with one quick motion threw open the door and crouched low within it. I saw an automatic flash dully in his hand; saw it cover the cabin from side to side, following the swift sweep of his eyes around it. Then he straightened and his face, turned toward the berth, was filled with wondering pity.

Da Costa and I had stepped in behind him. Through the window streamed a shaft of the moonlight. It fell upon Huldricksson's staring eyes; in them great tears slowly gathered and rolled down his cheeks; from his opened mouth came the woe-laden wailing. I ran to the port and drew the curtains. Da Costa snapped the lights.

The Norseman's dolorous crying stopped as abruptly as though cut. His gaze rolled toward us. And then his whole body reddened with a shock of rage, and at one bound he broke through the strong leashes I had buckled around him and faced us, a giant, naked figure tense with wrath, his eyes glaring, his yellow hair almost erect with the force of the passion visibly surging through him. Da Costa shrunk behind me. O'Keefe, coolly watchful, took a quick step that brought him in front of me.

"Where do you take me?" said Huldricksson, and his voice was thick as the growl of a wild beast. "Where is my boat?"

I touched O'Keefe gently and stood in front of the giant. He glared at me, and I saw the muscles of the gigantic arms flex and the hands below the bandaged wrist clench. He was berserk—mad!

"Listen, Olaf Huldricksson," I said. "We take you to where the sparkling devil took your Helma and your Freda. We follow the sparkling devil that came down from the moon. Do you hear me?" I spoke slowly, distinctly, striving to pierce the mists that I knew swirled around the strained brain. And the words did pierce. He stared at me for a moment. I heard O'Keefe murmur: "Good stuff! That's the idea. Humor him." Huldricksson stared at me and thrust out a shaking hand. As I gripped it I saw his madness fade, while his great chest heaved and fell. "You say you follow?" he asked falteringly. "You know where to follow? Where it took my Helma and my little Freda?"

"Just that, Olaf Huldricksson," I answered. "Just that! I pledge you my life that I know."

Once more Huldricksson searched me with his glance; once more turned and absorbed O'Keefe in the blue of his eyes.

"A man, ja," he muttered. He pointed to me. "And you—a man ja! But not the same as him—and me."

"I tell," he said, and seated himself on the side of the bunk. "It was four nights ago. My Freda"—his voice shook—"Mine yndling! She loved the moonlight. I was at the wheel and my Freda and my Helma they were behind me. The moon was behind us and the Brunhilda was like a swan-boat sailing down with the moonlight sending her, ja.

"I hear my Freda say; 'I see a nisse coming down the track of the moon.' And I hear her mother laugh, low like a mother does when her yndling dreams. I was happy, that night, with my Helma and my Freda, and the Brunhilda sailing like a swan-boat, ja. I heard the child say, 'The nisse comes fast!' And then I heard a scream from my Helma, a great scream—like a mare when her foal is torn from her. I spun around fast, ja! I dropped the wheel and spun fast! I saw—" He covered his eyes with his hands.

THE Portuguese had crept close to me and I heard him panting

like a frightened dog. O'Keefe, immobile, watched the Norseman

narrowly. His hand fell and hate crept into his eyes; a bitter

hate; that winged and white-hot hate that makes even the gods

tremble.

"I saw a white fire spring over the rail," whispered Olaf Huldricksson. "It whirled round and round, and it shone like—like stars in a whirlwind mist. There was a noise in my ears. It sounded like bells—little bells, ja! Like the music you make when you run your finger round goblets. It made me sick and dizzy, the bells' noise.

"My Helma was—indeholde—what you say—in the middle of the white fire. She turned her face to me and she turned it on the child, and my Helma's face burned into my heart. Because it was full of fear, and it was full of happiness—of glyaede. I tell you that the fear in my Helma's face made me ice here"—he beat his breast with clenched hand—"but the happiness in it burned on me like fire. And I could not move.

"I said in here"—he touched his head—"I said, 'It is Loki come out of Helvede. But he cannot take my Helma, for Christ lives and Loki has no power to hurt my Helma or my Freda! Christ lives! Christ lives!' I said. But the sparkling devil did not let my Helma go. It drew her to the rail; half over it. I saw her eyes upon the child and a little she broke away and reached to it. And my Freda jumped into her arms. And the fire wrapped them both and they were gone! A little I saw them whirling on the moon track behind the Brunhilda, and they were gone!

"The sparkling devil took them! Loki was loosed, and he had power. I turned the Brunhilda, and I followed where my Helma and mine yndling had gone. My boys crept up and asked me to turn again. But I would not. They dropped a boat and left me. I steered straight on the path. I lashed my hands to the wheel that sleep might not loose them. I steered on and on and on—

"Where was the God I prayed when my wife and child were taken?" cried Olaf Huldricksson—and it was as though I heard Throckmartin three years before asking that same bitter question. "I have left Him as He left me ja! I pray now to Thor and to Odin, who can fetter Loki!" He sank back, then, covering again his eyes.

"Olaf," I said, "what you have called the sparkling devil has taken ones dear to me. I, too, was following it when we found you. You shall go with me to its home, and there we will try to take from it your wife and child and my friends as well. But now that you may be strong for what is before us, you must sleep again."

"You speak the truth!" he said at last slowly. "I will do what you say!"

BESIDE the sleeping Norseman, when the little Portuguese had

turned in, I told O'Keefe my story from end to end. He asked few

questions as I spoke; only watched me with a somewhat

disconcerting intensity. In the main his inquiries dealt with the

sound phenomena accompanying the apparition of the Dweller. He

made a few somewhat startling interruptions dealing with

Throckmartin's psychology. And after I had finished he

cross-examined me rather minutely upon my recollections of the

radiant phases upon each appearance, checking these with

Throckmartin's observations of the same activities in the Chamber

of the Moon Pool.

"And now what do you think of it all?" I asked.

He sat silent for a while.

"Not just what you seem to think, Dr. Goodwin," he answered at last, gravely. "Let me sleep over it and, like the captain, I'll tell you tomorrow. One thing of course is certain—you and your friend Throckmartin and this man here saw—something. But"—he was silent again and then continued with a kindness that I found vaguely irritating—"but I've noticed that when a scientist gets superstitious it—Dr—takes very hard!

"Here's a few things I can tell you now, though," went on O'Keefe, while I struggled to speak. "I pray in my heart that the old Dolphin is so busy she'll forget me for a while and that we won't meet anything with wireless on board her going up. Because, Dr. Goodwin, I'd dearly love to take a crack at your Dweller.

"Good night!" said Larry O'Keefe and took himself out to the deck hammock he had insisted upon having slung for him, refusing the captain's importunities to use his own cabin.

Half laughing, half irritated and wholly happy in even the part promise of Larry O'Keefe's comradeship on my venture, I arranged a couple of pillows, stretched myself out on two chairs and took up my vigil beside Olaf Huldricksson.

WHEN I awakened the sun was streaming through the cabin porthole. Outside a fresh voice lilted. I lay on my two chairs and listened. The song was one with the wholesome sunshine and the breeze blowing stiffly and whipping the curtains. It was Larry O'Keefe at his matins.

I opened my door. O'Keefe stood outside laughing. Behind him the Tonga boys clustered, wide-toothed and adoring. Even the Cantonese mate had something on his face that served for a grin and Da Costa was beaming. I closed the door behind me.

"How's the patient?" asked O'Keefe.

He was answered by Huldricksson himself, who must have risen just as I left the cabin. The great Norseman had slipped on a pair of pajamas and, giant torso naked under the sun, he strode out upon us. We all of us looked at him a trifle anxiously. But Olaf's madness had left him. His face was still drawn and in his eyes was much sorrow, but the berserk rage had vanished. He stretched out a hand to us in turn.

"This is Dr. Goodwin, Olaf," said Da Costa. "An' this is Lieutenant O'Keefe of the English Navy."

Huldricksson bowed, with a touch of grace that revealed him not all rough seaman—and indeed, as I was later to find the Norwegian had been given gentle upbringing and a fair education before the wanderlust of his race had swept him into these far seas.

He addressed himself straight to me: "You said last night we follow?"

I nodded.

"It is where?" he asked again.

"We go first to Ponape and from there to Metalanim Harbor—to the Nan-Matal. You know the place?"

Huldricksson bowed, a white gleam as of ice showing in his blue eyes.

"It is there?" he asked.

"It is there that we must first search," I answered.

"Good!" said Olaf Huldricksson. "It is good!"

The Suwarna hove to and Da Costa and he dropped into the small boat. When they reached the Brunhilda's deck I saw Olaf take the wheel and the two fall into earnest talk. I beckoned to O'Keefe and we stretched ourselves out on the bow hatch under cover of the foresail. He lighted a cigarette, took a couple of leisurely puffs, and looked at me expectantly.

"Well," I asked, "and what do you think of it now?"

"Well," said O'Keefe, "suppose you tell me what you think, and then I'll proceed to point out your scientific errors." His eyes twinkled mischievously.

"I think," I said, "it is possible that some members of that race peopling the ancient continent which we know existed here in the Pacific and which was destroyed by a comparatively gradual subsidence, have survived. We know that many of these islands are honey-combed with caverns and vast subterranean spaces too great to be so called. These are literally underground lands, running in many cases far out beneath the ocean floor. It is possible that for some reason the survivors of this race of which I speak sought refuge in these abysmal spaces, one of whose entrances is on the Island where Throckmartin's party met its end.

"As for their persistence in these caverns, we know the lost people possessed a high science. This is indisputable. It may be that they had gone far in their mastery of certain universal forms of energy. They may have discovered the secret of that form of magnetic etheric vibration we call light. If so, they would have had no difficulty in maintaining life down there, and, indeed, shielded by earth's crust from the natural forces which always have surface man more or less at their mercy, they may have developed a civilization and extended a science immensely more advanced than ours. And unless they have also developed a complete indifference to conquest and an inflexible determination never to come forth from their world, they must always continue to be a potential menace to our world."

I paused. His keen face was now all eager attention.

"Have you ever heard of the Chamats?" I asked him. He shook his head.

"In Papua," I explained, "there is a widespread and immeasurably old tradition that 'imprisoned under the hills' is a race of giants who once ruled this region 'when it stretched from sun to sun' and 'before the moon god drew the waters over it'—I quote from the legend. Not only in Papua but in Borneo and Java and in fact throughout Malaysia you find this story. And, so the tradition runs, these people—the Chamats—will one day break through the hills and rule the world; 'make over the world' is the literal translation of the constant phrase in the tale. Does this convey anything to you, Larry?"

"Something," he nodded. "Go on."

"It conveys something to me," I said, "especially in the light of what Throckmartin heard and saw and what Huldricksson and I witnessed.

"It is possible that these survivors are experimenting with their science, and that what I call 'the Dweller' is one of their results. Or it may be that the phenomenon is something that they created long ago and control of which they may have lost. Or again it may be some unknown, energy that they found when they entered their subterranean realm and which they have learned to control or which controls them.

"This much is sure—the moon door, which is clearly operated by the action of moonlight upon some unknown element or combination in much the same way that the metal selenium functions under sun rays or the electric light, and the crystals through which the moon rays, pour down upon the pool their prismatic columns, are humanly made mechanisms.

"Set within, the ruins they would seem to argue for the ancientness of the work. But who can tell when moon door and moon lights were set in their places? Nevertheless, so long as they are humanly made, and so long as it is this flood of moonlight from which the Dweller draws its power of materialization, the Dweller itself, if not the product of the human mind is at least dependent upon the product of the human mind for its appearance."

My pride in this analysis was short lived.

"Wait a minute, Goodwin," said O'Keefe. "Do you mean to say you think that this thing is made of—well, of moonshine?"

"Moonlight," I replied, "is, of course, reflected sunlight. But the rays which pass back to earth after their impact on the moon's surface are profoundly changed. The spectroscope shows that they lose practically all the slower vibrations we call red and infra-red, while the extremely rapid vibrations we call the violet and ultra-violet are accelerated and altered. Many scientists hold that there is an unknown element in the moon—perhaps that which makes the gigantic luminous trails that radiate in all directions—from the lunar crater Tycho—whose energies are absorbed by and carried on the moon rays.

"At any rate, whether by the loss of the vibrations of the red or by the addition of this mysterious force, the light of the moon becomes something entirely different from mere modified sunlight—just as the addition or subtraction of one other chemical in a compound of several makes the product a substance with entirely different energies and potentialities.

"Now these rays are given perhaps still another mysterious activity by the transparent globes through which Throckmartin told me they passed in the Chamber of the Moon Pool and whose colors they take. The result is the necessary factor in the formation of the Dweller. There would be nothing scientifically improbable in such a process, Larry.

"We know the extraordinary effect of the Finsen rays, which are only the concentration of the chemical energies in the green and blue of the spectrum, upon malignant cell growths in the human body; and we know that the X-ray can dissolve the normal barrier of matter for us, making the solid transparent. We do not begin to know how to harness the potentialities of light. This hidden race may have learned; and learning, may have created forms with powers undreamed by us."

"LISTEN, Doc," said Larry earnestly, "I'll take everything you

say about this lost continent, the people who used to live on it,

and their caverns, for granted. But by the sword of Brian Boru,

you'll never get me to fall for the idea that a bunch of

moonshine can handle a big woman such as you say Throckmartin's

Thora was, nor a two-fisted man such as you say Throckmartin was.

You'll never get me to believe that any bunch of concentrated

moonshine could handle them and take them waltzing off along a

moonbeam back to wherever it goes. No, Doc, not on your

life."

"I've told you that what you call moonshine is an aggregate of vibrations with immense potential power, Larry," I answered, considerably irritated. "What we call matter is nothing but a collection of infinitely small particles of electricity—electrons; and the way the electrons are grouped makes of matter man or wood or metal or stone. Light is a magnetic vibration of the ether and is probably composed of similar particles of electricity but functioning in another way from the particles that make matter. Learn the secret of making light and you come close to learning the secret of matter.

"Why, if you could take all the energy out of the sunshine that in one minute covers one square foot of earth, you could blast all the earth to bits. And your wonderful radio is nothing but vibrations, yet it carries words around the world with almost the speed of light itself—"

"No," he interrupted. "You're wrong."

"All right O'Keefe," I answered, now very much irritated indeed. "What's your theory?" And I could not resist adding; "Fairies?"

"Professor," he grinned, "if it's a fairy it's Irish and when it sees me it'll be so glad there'll be nothing to it. 'I was lost, strayed or stolen; Larry avick,' it'll say, 'an' I was so homesick for the old sod I was desp'rit,' it'll say, 'an' take me back quick before I do any more har-rm!' it'll tell me—an' that's the truth."

I forgot my chagrin in our laughter.

"But I'll tell you what I think," he said soberly. "Back at the first battle of the Marne, there were any number of Englishmen who thought they saw the old archers of Crecy and Agincourt, dead these half dozen centuries, twanging phantom bows and shooting down the enemy by the hundred. And you can find thousands of Frenchmen who saw Joan of Arc and Napoleon regularly. It's what the doctors call collective hallucination. Somebody sees something a little queer; his imagination gets to work hard because his nerves are pretty well strained anyway, he says to the next fellow: 'Don't you see it?' and the next fellow says, 'Sure I see it, too!' And there you are—bowmen of Mons, St. George on his white horse, Joan in armor, and all the rest of it."

"If you think that explains Throckmartin and myself, how do you explain Huldricksson, who never saw Throckmartin and didn't see me before the Thing came to the Brunhilda?" I asked with, I admit, some heat.

"Now don't get me wrong," replied Larry. "I believe you all saw something all right. But what I think you saw was some kind of gas. All this region is volcanic and islands and things are constantly poking up from the sea. It's probably gas; a volcanic emanation; something new to us and that drives you crazy—lots of kinds of gas do that.

"It hit the Throckmartin party on that island and they probably were all more or less delirious all the time; thought they saw things; talked it over and—collective hallucination. When they got it bad they most likely jumped overboard one by one. Huldricksson sails into a place where it is and it hits his wife. She grabs the child and jumps overboard. Maybe the moon rays make it luminous."

"But that doesn't explain the moon door and the phenomena of the lights in the Chamber of the Pool," I said at last.

"You haven't seen them, have you?" asked Larry. "And Throckmartin admitted he was pretty nearly crazy when he thought he did. Well!"

For a time I was silent.

"Larry," I said at last, "whether you are right or I am right, I must go to the Nan-Matal. Will you go with me, Larry?

"Goodwin," he replied, "I surely will. I'm as interested as you are. If I'm reported dead for a while, there's nobody to care. So that's all right. Only, old man, be reasonable. You've thought over this so long, you're going bugs, honestly you are."

And again, the gladness that I might have Larry O'Keefe with me, was so great that I forgot to be angry.

DA COSTA, who had come aboard unnoticed by either of us, now

tapped me on the arm.

"Doctair Goodwin," he said, "can I see you in my cabin, sair?"

At last, then, he was going to speak. I followed him.

"Doctair," he said, when we had entered, "this is a veree strange thing that has happened to Olaf. Veree strange. An' the natives of Ponape, they have been very much excite' lately. An' none go near the Nan-Matal now, for they say the spirits have got great power and are angree because of that othair partee which they take.

"Of what they fear I know nothing, nothing!" Again that quick, furtive crossing of himself. "But this I have to tell you. There came to me from Ranaloa last month a man, a German, a doctair, like you. His name it was Von Hetzdorp. I take him to Ponape an' the natives there, they will not take him to the Nan-Matal, where he wish to go. So I take him. We leave in a boat, with much instrument carefully tied, up. I leave him there wit' the boat an' the food. He tell me to tell no one an' pay me not to. But you are a friend an' Olaf he depend much upon you an' so I tell you, sair."

"You know nothing more than this, Da Costa?" I asked. "You're sure?"

"Nothing! Nothing more!" he answered. But I was not so sure. Later I told O'Keefe.

The next morning we raised Ponape, without further incident, and before noon the Suwarna and the Brunhilda had dropped anchor in the harbor. Upon the excitement and manifest dread of the natives, when we sought among them for carriers and workmen to accompany us, I will not dwell. No payment we offered would induce a single one of them to go to the Nan-Matal. Nor would they say why.

They were sullen and panicky, and I think the most disconcerting thing of all in their attitude, was the open relief they showed when they learned that a British warship might steam in, seeking O'Keefe. It indicated that their fear was deep-rooted and real, indeed.

We piled the longboat up with my instruments and food and camping equipment. The Suwarna took us around to Metalanim Harbor, and there, with the tops of ancient sea walls deep in the blue water' beneath us, and the ruins looming up out of the mangroves, a scant mile from us, left us.

Da Costa's anxiety and uneasiness were almost pitiful. There were tears in the eyes of the little Portuguese when he bade us farewell, invoking, all the saints to stand by and protect us; and the sorrow in his face and the fervor of his parting grip were eloquent of his conviction that never again would he behold us.

Then, with Huldricksson manipulating our small sail and Larry at the rudder, we rounded the titanic wall that swept down into the depths, passed monoliths, standing like gigantic sentinels upon its shattered verge. We turned at last into the canal that Throckmartin, on his map, had marked as the passage which led straight to that place of ancient mysteries where the moon door is portal of that dread chamber wherein the Dweller made itself manifest.

And, as we entered, that channel we were enveloped, by a silence; a silence so intense, so weighted, that it seemed to have substance; an alien silence that clung and stifled and still stood aloof from us, the living.

Standing down in the chambered depths of the Great Pyramid I had known something of such silence, but never such intensity as this. Larry felt it and I saw him look at me askance. If Olaf, sitting In the bow, felt it, too, he gave no sign. His blue eyes, with again the glint of ice within them watched the channel before us.

As we passed, there arose upon our left sheer walls of black basalt blocks, cyclopean, towering fifty feet or more, broken here and there by the sinking of their deep foundations. And only where they had so broken, had the hand of time been able to crumble them. From these dark ramparts the silence seemed to ooze, and my skin crept as though from hidden places in them scores of eyes, ages dead, peered out at us, like ghosts of a lost Atlantis.

In front of us the mangroves widened out and filled the canal. On our right the lesser walls of Tau, somber blocks smoothed and squared and set with a cold, mathematical nicety, that filled me with vague awe, slipped by. Through breaks I caught glimpses of dark ruins and of great fallen stones that seemed to crouch and menace us as we passed. Somewhere there, hidden, were the seven globes that poured the moon fire down upon the Moon Pool.

Now we were among the mangroves and, sail down, the three of us pushed and pulled the boat through their tangled roots and branches. The noise of our passing split the silence, like a profanation, and from the ancient bastions came murmurs—forbidding, strangely sinister. And now we were, through, floating on a little open space of shadow-filled water. Before us lifted the gateway of Nan-Tanach, gigantic, broken, incredibly old. Shattered portals through which had passed men and women of earth's dawn; old with a weight of years that pressed leadenly upon the eyes that looked upon it, and yet in some curious, indefinable way—menacingly defiant.

Beyond the gate, back, from the portals, stretched a flight of enormous basalt slabs, a giant's stairway indeed; and from each side of it marched the high walls that were the Dweller's pathway. None of us spoke as we grounded the boat and dragged it up upon a half-submerged pier.

"What next?" whispered Larry, at last.

"I think we ought to take a look around," I replied In the same low tones. "We'll climb the wall here and take a flash about. The whole place ought to be plain as day from that height."

Huldricksson, his blue eyes now alert, nodded. With the greatest of difficulty we clambered up the broken blocks, the giant Norseman at times lifting me like a child, and stood at last upon the broad top. From this vantage-point, not only the whole of Nan-Tanach, but all of the Nan-Matal lay at our feet.

TO the east and south of us, set like children's blocks in the

midst of the sapphire sea, were dozens of islets, none of them

covering more than two square miles of surface; each of them a

perfect square or oblong within its protecting walls. Behind

these walls were grouped ruins—houses, temples, palaces,

all the varying abodes of men. On none was there sign of life,

save for a few great birds that, hovered here and there and gulls

dipping in the blue waves beyond.

We turned our gaze down upon the island on which we stood. It was, I estimated, about three-quarters of a mile square. The sea wall enclosed it like the sides of a gigantic box. It was really an enormous basalt-sided open cube, and within it two other open cubes. The enclosure between the first and second wall was stone paved, with here and there a broken pillar and long stone benches.

The hibiscus, the aloe-tree and a number of small shrubs had found place, but seemed only to intensify its stark loneliness. It came to me that this had been the assembling place of those who, thousands upon thousands of years ago, had gathered within this citadel of mystery. Beyond the wall that was its farther boundary was a second enclosure, littered with broken pillars, fragments of stone and numerous small structures; and the second enclosure's limit was the third wall, a terrace not more than twenty feet high. Within it was what had been without doubt the heart of Nan-Tanach—an open space three hundred feet square; at each of its corners a temple.

Directly before us, black and staring like an eyeless socket, was the entrance to the "treasure-house of Chau-ta-Leur" the sun king. The blocks that had formed its doors lay shattered beside it. And opposite it should be, if Throckmartin's story had not been a dream, the gray slab he had named the moon door.

"Wonder where the German fellow can be?" asked Larry.

I shook my head. There was no sign of life here. Had Von Hetzdorp gone, or had the Dweller taken him, too? Whatever had happened, there was no trace of him below us or on any of the islets within our range of vision. We scrambled down the side of the gateway. Olaf looked at me wistfully.

"We start the search now, Olaf," I said. "And first, O'Keefe, let us see whether the gray stone is really here. After that we will set up camp, and while I unpack, you and Olaf search the island. It won't take long."

Larry gave a look at his service automatic and grinned. We made our way up the steps, through the outer enclosures and into the central square. I confess to a fire of scientific curiosity and eagerness tinged with a dread that O'Keefe's analysis might be true. Would we find the moving slab and, if so, would it be as Throckmartin had described? If so, then even Larry would have to admit that here was something that theories of gases and luminous emanations would not explain; and the first test of the whole amazing story would be passed. But if not—

And there before us, the faintest tinge of gray setting it apart from its neighboring blocks of basalt, was the moon door!

There was no mistaking it. This was, in very deed, the portal through which Dr. Throckmartin had seen pass that gloriously dreadful apparition he called the Dweller; through it the Dweller had borne in an embrace of living light first Thora, Mrs. Throckmartin's maid, and then Dr. Stanton, his youthful colleague. And through it at last had gone Throckmartin, down the shining tunnel beyond, whose luminous lure led to that enchanted chamber into which streamed the seven moon torrents that drew the Dweller from the wondrous pool that was its lair.

Across its threshold had raced Edith Throckmartin, my lost friend's young bride, fearlessly flying down that haunted passage to aid her husband in his fruitless fight against the Thing—and out of it he himself had rushed, a merciful darkness shrouding consciousness and sight, after he had watched her sink, slowly sink, down through the blue waters of the moon pool, wrapped in the Dweller's coruscating folds, to—what?

And then there seemed to drift out through the stone to face me that inexplicable being of swirling, spiraling plumes and Jets of sparkling opalescence, of crystal sweet chimings, of murmuring sighings that Throckmartin had told me stamped upon the faces of its prey wedded anguish and rapture, terror and ecstasy commingled, joy of heaven and agony of hell, the seal of God and devil monstrously mated. The Thing that my own eyes had seen clasp Throckmartin in our cabin of the Southern Queen and draw him swiftly down the moon path.

What was that portal, more enigmatic than was ever sphinx? And what lay beyond it? What did that smooth stone, whose wan deadness whispered of ages old corridors of time opening out into alien, unimaginable vistas, hide? It had cost the world of science Throckmartin's great brain, as it had cost Throckmartin those he loved. It had drawn me to it in search of Throckmartin, and its shadow had fallen upon the soul of Olaf the Norseman; and upon what thousands upon thousands more, I wondered, since the brains that had conceived it had vanished?

Did the Dweller lurk behind it in wait for us? When we found its open-sesame would we find within truths of our world's youth to which the riches of Ali Baba's cave were but dross? Was there that within which would force science to recast its hard won theories of humanity, of its evolution, of its painful progress from, brute to what we call man? Or would we loose upon the world some nameless, blasting evil, some survival of our planet's nightmare hours, some supernormal, inhuman thing spawned by unthinkable travail in a hidden cavern of mother earth?

A barrier of unknown stone—fifteen feet high and ten feet wide; and yet it might bar the way to a lost paradise or hold back a hell undreamed by even cruelest brains! What lay beyond it?

SWIFTLY the thoughts raced through my mind as I stood staring

at the gray slab and then through me passed a wave of weakness.

And not until then did I realize the intense, subconscious

anxiety that had possessed me.

I stretched out a shaking hand and touched the surface of the slab. A faint thrill passed through my hand and arm, oddly unfamiliar and as oddly pleasant; as of electric contact holding the very essence of cold. O'Keefe, watching, imitated my action. As his fingers rested on the stone his face filled with astonishment. In Huldricksson's eyes was mingled hope and despair. I beckoned him; he laid a hand on the slab and swiftly withdrew it. But I saw the despair die from his face, leaving only eagerness, a sudden hope.

"It is the door!" he said. I nodded. There was a low whistle of astonishment from O'Keefe and he pointed up toward the top of the gray stone. I followed the gesture and saw, above the moon door and on each side of it, two gently curving bosses of rock, perhaps a foot in diameter.

"The moon door's keys," I said.

"It begins to look so," answered Larry. "If we can find them," he added.

"There's nothing we can do till moonrise," I replied. "And we've none too much time to prepare as it is. Come!"

But stark lonely as was that place, I felt, as we passed out, as though eyes were upon me, watching with an intensity of malevolence, a bitter hatred. Olaf must have felt it, too, for I saw him glance sharply around and his face hardened. I said nothing, however, nor did he; and a little later we were beside our boat. We lightered it, set up the tent, and as it was now but a short hour to sundown I told them to leave me and make their search. They went off together, and I busied myself with opening some of the paraphernalia I had brought with me.

First of all I took out two Becquerel ray-condensers that I had bought in New York. Their lenses would collect and intensify to the fullest extent any light directed upon them. I had found them most useful in making spectroscopic analysis of luminous vapors, and I knew that at Yerkes Observatory splendid results had been obtained from them in collecting the diffused radiance of the nebulae for the same purpose.

It was my theory that the mechanism operating the moon door responded only to the force of the full light of the moon shining through the seven little circles which Throckmartin had discovered set within each of the bosses above it; just as the Dweller could materialize only under the same full-moon force shining through the varicolored lights. Obviously the time, then, of the door's opening and the phenomenon's materialization must coincide.

With the moon only a few days' past Its full, it was practically certain that by setting the Becquerel condensers above the bosses I could concentrate enough light upon the circles to set the opening mechanism in motion. And as the ray stream from the waning moon was insufficient to energize the pool, we could enter the chamber free from any fear of encountering its tenant, make our preliminary observations and go forth before the satellite had dropped so far that the concentration in the condensers would fall below that necessary to keep the slab from closing.

I took out also a small spectroscope, easily carried, and a few other small instruments for the analysis of certain light manifestations and the testing of metal and liquid. Finally, I put aside my emergency medical kit.

I had hardly finished examining and adjusting these before O'Keefe and Huldricksson returned. They reported signs of a camp at least ten days old beside the northern wall of the outer court, but beyond that no evidence of others beyond ourselves on Nan-Tanach. Moonrise would not occur until nine-thirty, and until then there was no use of attacking the moon door.

We prepared supper, ate and talked a little, but for the most part were silent. Even Larry's high spirits were not in evidence; half a dozen times I saw him take out his automatic and look it over. He was more thoughtful than I had ever seen him. Once he went into the tent, rummaged about a bit and brought out another revolver which, he said, he had got from Da Costa, and a half-dozen clips of cartridges. He passed the gun to Olaf.

At last a glow in the southeast heralded the rising moon. I picked up my instruments and the medical kit; Larry and Olaf shouldered each a short ladder that was part of my equipment. With our electric flashes pointing the way, we walked up the great stairs, through the enclosures, and straight to the gray stone.

By this time the moon had risen and its clipped light shone full upon the slab. I saw faint gleams pass over it as of fleeting phosphorescence, but so faint were they that I could not be sure of the truth of my observation. The base of the gray stone bisected a curious cuplike depression whose perfectly rounded sides were as smooth as though they had been polished by a jeweler. This half cup was, at its deepest, two and a half feet, and its lip joined the basalt pavement four feet from the barrier of the great slab.

WE set the ladders in place. Olaf I assigned to stand, before

the door and watch for the first signs of its opening—if

open it should—and the big sailor accepted the post

eagerly, thinking, I suppose, that it would bring him nearer the

loved ones he now was sure were within. The Becquerels were set

within three-inch tripods, whose feet I had equipped with vacuum

rings to enable them to hold fast to the rock.

I scaled one ladder and fastened a condenser over the boss; descended; sent Larry up to watch it, and, ascending the second ladder, rapidly fixed the other in its place. Then, with O'Keefe watchful on his perch, I on mine and Olaf's eyes fixed upon the moon door, we began our vigil. Suddenly there was an exclamation from Larry.

"Seven little lights are beginning to glow on this stone, Goodwin!" he cried.

But I had already seen those beneath my lens begin to gleam out with a silvery luster! Swiftly the rays within the condenser began to thicken and increase, and as they did so the seven small circles waxed like stars growing out of the dusk, and with a queer—curdled is the best word I can find to define it—luster entirely strange to me.

I placed a finger upon one of them and received a shock such as I had felt on touching the moon floors only greatly intensified. Clearly a current of some kind was set up within the substance when the moonlight fell upon it. And now the lights were glowing steadily. Beneath me I heard a faint, sighing murmur and then the voice of Huldricksson:

"It opens—the stone turns—"

I began to climb down the ladder. Again came Olaf's voice:

"The stone—it is open—" And then a shriek that came from the very core of his heart; a wail of blended anguish and pity, of rage and despair—and the sound of swift footsteps racing through the wall beneath me!

I dropped to the ground. The moon door was wide open, and through it I caught a glimpse of a corridor filled with a faint, pearly vaporous light like earliest misty dawn. But of Olaf I could see nothing! And even as I stood, gaping, from behind me came the sharp crack of a rifle. I saw the glass of the condenser at Larry's side flash and fly into fragments; saw him drop swiftly to the ground and the automatic in his hand flash once, twice, into the darkness.

Saw, too, the moon door begin to pivot slowly, slowly back into its place!

I rushed toward the turning stone with the wild idea of holding it open. As I thrust my hands against it there came at my back a snarl and an oath and Larry staggered under the impact of a body that had flung itself straight at his throat. He reeled at the lip of the shallow cup at the base of the slab, slipped upon its polished curve, fell and rolled with that which had attacked him, kicking and writhing, straight through the narrowing portal into the mistily luminous passage!

Forgetting all else, I sprang with a cry to his aid. And as I leaped I felt the closing edge of the moon door graze, my side. And then, as Larry raised a fist, brought it down upon the temple of the man who had grappled with him and rose from the twitching body unsteadily to his feet, I heard shuddering past me a mournful whisper; spun about as though some giant hand had whirled me—and stood so, rigid, appalled!

For the end of the corridor no longer opened out into the moonlit square of ruined Nan-Tanach. It was barred by a solid mass of glimmering stone. The moon door had closed!

And where was Olaf Huldricksson? And who was the man at our feet who brought this calamity down upon us? And what were we to do, prisoned, and my bewildered brain told me, hopelessly prisoned, without food, in the very lair of the Dweller itself?

"LARRY!" I cried, turning to O'Keefe, "the stone has shut! We're caught!"

O'Keefe took a brisk step toward the barrier behind us. There was no mark of juncture with the shining walls; the slab fitted into the sides as closely as a mosaic.

"It's shut all right," said Larry. "But if there's a way in, there's a way out. Anyway, Doc, we're right in the pew we've been heading for, so why worry?" He grinned at me cheerfully, and although I could not accept his light-hearted view of situation, I felt a twinge of shame for my momentary panic. The man on the floor groaned, and O'Keefe dropped swiftly to his knees beside him.

"Von Hetzdorp!" he said.

At my exclamation he moved aside, turning the face so I could see it. It was clearly German, and just as clearly its possessor was a man of considerable force and intellectuality.

The strong, massive brow with orbital ridge unusually developed, the dominant high-bridged nose, the straight lips with their more than suggestion of latent cruelty, and the strong lines of the jaw beneath a black, pointed beard all gave evidence that here was a personality beyond the ordinary. The hair was closely cropped on the square head, and the short, stocky body with its deep chest and abnormal length of torso as compared to the legs, indicated extraordinary vitality.

Unscrupulous, I thought, looking down upon him, remorseless, crafty, and with a brain as unmoral as is science itself.

"Got another one of those condensers the Heinie here broke?" Larry asked me suddenly. "And do you suppose Olaf will know enough to use it?"

And then it dawned upon me that O'Keefe could not have heard, as I had, the Norseman race into the moon door's passage before the door had closed! I arose swiftly.

"Larry," I answered, "Olaf's not outside! He's in here somewhere!"

His jaw dropped.

"Didn't you hear him shriek when the stone opened?" I asked.

"I heard him yell, yes," he said. "But I didn't know what was the matter. And then this wildcat jumped me—" He paused and his eyes widened. "Which way did he go?" he asked swiftly. I pointed down the faintly glowing passage.

"There's only one way," I said.

"Watch that bird close," hissed O'Keefe, pointing to Von Hetzdorp—and pistol in hand stretched his long legs and raced away. I looked down at the German. His eyes were open and he reached out a hand to me. I lifted him to his feet.

"I have heard," he said. "We follow quick. If you will take my arm, please, I am shaken yet, yes—" I gripped his shoulder without a word, and the two of us set off down the corridor after Larry. Von Hetzdorp was gasping, and his weight pressed upon me heavily, but he moved with all the will and strength that was in him.