RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"BULLY" HAYES was a notorious American-born "blackbirder" who flourished in the 1860 and 1870s, and was murdered in 1877. He arrived in Australia in 1857 as a ships' captain, where he began a career as a fraudster and opportunist. Bankrupted in Western Australia after a "long firm" fraud, he joined the gold rush to Otago, New Zealand. He seems to have married around four times without the formality of a divorce from any of his wives.

He was soon back in another ship, whose co-owner mysteriously vanished at sea, leaving Hayes sole owner; and he joined the "blackbirding" trade, where Pacific islanders were coerced, or bribed, and then shipped to the Queensland canefields as indentured labourers. After a number of wild escapades, and several arrests and imprisonments, he was shot and killed by ship's cook, Peter Radek.

So notorious was "Bully" Hayes, and so apt his nickname, (he was a big, violent, overbearing and brutal man) that Radek was not charged; he was indeed hailed a hero.

Dorrington wrote a number of amusing and entirely fictitious short stories about Hayes. Australian author Louis Becke, who sailed with Hayes, also wrote about him.

—Terry Walker

"LIKE a thief in the night," said Captain Hayes, lowering his

glasses. "Bet a handful of dollars it's that plug-headed labour

schooner of Lewin's."

Leaning over the trade-house verandah, the buccaneer stared again at the dark, unlit vessel moving through the narrow reef entrance. The surf flew in heaps where the stiff-crested palms broke the knife-like edge of skyline. The unvarying boom of the breakers, the loud after-crash and the swooning silence that followed, was heart-music to the man who regarded Eight Bells Island as his own.

The sudden entry of this stark, voiceless craft into his lagoon cast a sullen spell over Hayes. It stole upon him like an unclean thing dripping blood and tears from its sea-weary planks.

The clatter and jolt of her anchor chains beat harshly upon his cars. A solitary light flashed from her port bow and vanished as though a rough hand had snatched it away. Five minutes later a dinghy shot from her side and made for the white strip of beach under the trade house window.

The buccaneer's night-glasses surveyed a lank, white figure as it clambered from the dinghy and strode leisurely towards the house. Turning from the verandah, Hayes spoke softly to a kanaka in the doorway and pointed to a large pink-shaded lamp hanging in the front room. A few moments afterwards the verandah was lit with half a dozen purple- and orange-coloured lanterns.

A great silence lay upon the island, a few fires still burned in the village behind the dark belt of palm woods facing the eastern side of the lagoon.

Hayes winced slightly as the lank white figure halted on the verandah steps. The schooner's appearance in that lonely, out-of- the-way archipelago surprised and vexed him. Between himself and her owner a quarrel still lay unsettled, and the buccaneer wondered whether there would be peace-offerings or a little friendly shooting.

The schooner's mission was clear to him; one glance at her villainous outline, and the armed shapes squatting on her hatches, made manifest her bleak, unwholesome calling.

The visitor halted at the verandah steps uncertainly, and regarded Hayes standing in the full lantern-flare motionless but savagely alert. Neither spoke for a while, but the silence seemed alive with unuttered threats.

"Well, what's the trouble, Lewin?" Hayes met the steely, almost lifeless eyes that stared at him from the shadow of the house palms. "Lost your crew?"

"I'm short of water, Bully. Left the Kingsmill two months ago, and we've been stewing in dead calms for three weeks. Our tanks are empty. I thought maybe you'd oblige me with a few hundred gallons—if it isn't asking too much."

"What's your cargo?" drawled Hayes: "bÍche-de-mer?"

"Cotton trade and few cases of square face."

"Don't lie to me, Captain Lewin; don't lie to me about that skulking kanaka-hell out there. You slink in here without a light, the fear of the gunboats in your vitals,—you and your cotton trade!"

Hayes paused and regarded him frostily. "First time the British gun boats meet you they're going to shell you at sight, Lewin. The smell of your schooner poisons the outer seas—you slaver!"

Lewin's hand played with his lantern jaw thoughtfully, until his sea-blackened lips puckered half humorously. "I like your tune, Bully." His words fell thick and raspy, like one who had not held speech with man for years. "You always had a good baritone voice. Try a hymn, or that Judas Maccabaeus thing you used to sing at the band concert in Coconut Square. Yah, I'm tired, Bully!" Lewin strode to the verandah, threw himself into a chair, and yawned.

The buccaneer suppressed a smile with difficulty as he eyed the lean, pale-eyed miscreant before him. "Guess you're looking thinner than a stick in a cyclone, Ross. How about your niggers? Got 'em battened down, as usual, licking the nail-heads to cool their tongues?" He nodded towards the schooner's black outline.

Lewin moistened the frayed edges of his cigar abstractedly. "We've had a time," he said softly. "You know what it's like out there, eight hundred miles between drinks, and not enough wind to dry your eye." He smoked on sullenly for a while, then glanced over his shoulder at the schooner. "All night and day I listened to 'em howling like dry-mouthed hyenas in a sand pit. What could I do?"

The "blackbirder" held out his hands for a moment as though appealing to the white-browed giant before him. "If I'd been a young man fresh from home I'd have sat down and cried perhaps."

A SOFT breeze stirred the face of the lagoon; the eyes of both

men went out to the lean black vessel anchored within gunshot of

the trade-house. A low, wailing murmur stole across the starlit

expanse, the strange pent-up sobbing of human voices, of weeping

men and children, followed by thudding sounds, as though a gun-

butt were smiting naked bodies and limbs.

Hayes flinched as though a knife had touched him. "Any women aboard?" he asked huskily.

"That's why I'm asking for water. D'ye think I'd have come in here if the fear of death hadn't sent me, Hayes?" The blackbirder breathed gently and glanced at the sky.

"You'll let me stay a couple of days to pull myself together. It will give the niggers breathing space, too."

"The water's yours for the asking, Lewin. But you'll quit here at daybreak. You're defiling my clean lagoon with your kanaka- trap."

"Give me forty-eight hours, Hayes. It's the last trip I'll ever make in the trade again."

"If I were a magistrate, Lewin, I'd give you forty-eight inches of rope for breakfast. Thank your stars I've been in the trade myself. Thank your stars I happen to be a bit of an outcast, too."

A SOFT footfall came from the house passage; a young girl

crossed the verandah and stood hesitating near the rail. Hayes

turned, and his eyes softened strangely. "Come here, Hetty. I

want to introduce you to Captain Ross Lewin."

The girl approached somewhat timidly; her eyes seemed to flinch from the gaze of the brooding slave-runner. "My niece, Hetty Bond," said the buccaneer slowly. "She's over on a visit from Sydney. It's a long time, Lewin, since you and me met decent people from the outside world. Suppose—"

The buccaneer paused, hand on hip, and grinned maliciously. "Suppose I ask this young lady to pass judgment on you? She's fresh from school and civilisation. You and me, Lewin, are so used to this kind of thing"—he nodded towards the unlit schooner—"that a little outside opinion might do us both good."

The slave-runner blinked owlishly; his sprawling legs seemed to twist and slacken as he leaned back in the chair. "Go on, Hayes. Say your say if it amuses you."

The buccaneer handed the night-glasses to his niece, smiling grimly. "Take a good look at that schooner, Hetty, and you'll see a couple of kanakas lying on the hatches."

The girl gazed half-puzzled as the schooner's outline took sudden shape before her, its dirty decks, its unclean galley, and the black objects crouching tiger-like on the hatch combings.

"What are they nursing those rifles for," she asked steadily, "in a quiet haven like Eight Bells lagoon?"

"They're Captain Lewin's watch-dogs, Hetty. If you could step below you'd see a picture that would blight your young eyes and hold you till you died. There are eighty men, women, and children barracooned below. Captain Lewin has brought them from the Kingsmill group. They're intended for the Fiji plantations, and are worth from fifty to a hundred dollars a head—landed. The schooner has been wind-bound for three weeks, with all that crowd below, and only a pint of water a day for each man and child. The children being pretty weak didn't get any in the scramble, eh, Lewin?"

The blackbirder's legs sprawled and twisted again; his small, sun-shrivelled eyes seemed to glow from their roots. He made no response, although the big silver ring on his middle finger tapped the verandah rail a trifle impatiently.

The girl looked up, and the blood flushed in her checks for a moment; her breath came in little heart-choking gasps that left her eyes full of sharp misery and dread. Hayes held her arm gently. "I did that kind of thing once, Hetty, but not Captain Lewin's way."

Tearing herself away, the girl reeled across the verandah, and with a sob ran down the trade-house passage, crying aloud as she ran.

BOTH men listened to the quiet, faraway sobbing that came from

her room. Hayes paced the verandah slowly, his thumbs locked

behind his powerful back. "That's what civilisation thinks of you

and me, Lewin. That's what half the world would do if it saw your

schooner tonight—run away and cover its head like little

Hetty."

"Give me some whisky, Hayes. This is my last trip in the Daphne, I swear it!"

The kanaka servant brought a bottle and placed it before the blackbirder. Hayes gave an order to another islander, waiting in the shadow of the trade-house, to carry water aboard the schooner.

Returning to the verandah, he dropped into a chair and watched Lewin gulp down the spirit like one who had passed through the eighteen Gehennas of Mencius. The long silence was only broken by the rattle of oars as the trade-house whale-boat plied to and from the schooner with its water-filled casks.

"Perhaps you'd like a friendly game of dice, Ross; or maybe you'll give us a song." Hayes helped himself to a little of the whisky somewhat sorrowfully.

"Howling at niggers has spoilt my voice," grinned the slave runner. "I want oiling; I'm too husky and wind-dried to sing."

"Try the dice," said Hayes smoothly. "Oil yourself with a little pleasant excitement. You won six hundred dollars from me in Apia two years ago."

"I've no currency, Bully. I put my last coin into my venture." He gestured towards the schooner abstractedly. "And I don't want' to borrow money to gamble with."

"Niggers are as good as money these times," drawled Hayes. "You put up a kanaka and I'll call him fifty dollars. A few of 'em would be useful to me if I win, and my ready cash won't hurt you if your luck's in."

The blackbirder untwined his legs; suddenly his dozing, sea- weary eyes wakened at the prospect of a little play. "Where's the bones?" he asked sharply. "I've eighty-two islanders on board, all told. They're worth their weight in silver to those Queensland sugar planters." He coughed and fingered his chin abstractedly. "I'll see the colour of your money before we start," he added shrewdly.

"My dollars are brighter than your niggers' heels, anyhow," laughed the buccaneer. He passed into the trade house briskly, and the waiting slave runner heard the jingle of the safe-keys within, followed by the creaking of the heavy iron door. His eyes grew large when Hayes returned, dice-box in hand, a bag of dollars under his arm.

Lewin examined the dice critically, casting them across the verandah table to satisfy himself that they were evenly balanced and free from loading.

THE sobbing in the outer room continued until it seemed to

disturb and irritate the lank, shamble-footed blackbirder. Hayes,

with a nod to his visitor, tiptoed down the passage to the little

side-room, where his niece sat half crouching in a chair.

"Hetty." He touched her shoulder tenderly. "There's a chance to-night of me lifting those niggers out of that schooner. Perhaps I oughtn't to have told you what I did."

"Oh, uncle, that man will never let you take those poor people from him! I saw his eyes, and they frightened me."

"He's as smart as steel with the dice, I'll admit, Het; but his eyes won't hold those niggers if I throw sixes, my lass."

"Are you playing for their liberation, Uncle Willy? And if you win?" she asked tremulously.

"I'll make him empty 'em from his dirty schooner on the clean white beach in front of the trade-house. And if he's one nigger short I'll—I'll turn off his gas at the meter," he grinned.

Returning to the verandah, Hayes lit a cigar cheerfully. "Throw for 'em in couples and call 'em one hundred dollars. You shake first, Lewin, because you are so nice-mannered. I'll pay in Chilean dollars or American greenbacks."

The blackbirder took up the dice feverishly and spun them across the little bamboo table. "Five!" Again be cast, and four were added. His last throw brought his score to fifteen.

The blackbirder took up the dice feverishly

and spun them across the little bamboo table.

Hayes played jauntily, casting high at each throw. Ten followed, eight and seven finished his rubber.

"Two niggers for you, Bully. How'll you take 'em—men or women?"

"Men."

THE game continued in the uneasy flare of the wind-tossed

lanterns. Hayes scored repeatedly, but no word of satisfaction

escaped him at each fresh win. Lewin sat back in his chair

wolfing the end of his cigar. Occasionally his luck turned,

allowing him to win back half a score of human lives, but Hayes

was not to be denied. He played with the nerve of a sharper until

the last kanaka stood marked to his credit on the closely

pencilled card at his elbow.

Lewin flung the dice-box from him and grinned silently, a lifeless sharp-toothed grin that spoke of the famishing windless spaces of sea over which his schooner had crawled.

"You've won, Hayes; eighty-two of 'em." He finished the whisky in the bottle and stretched his legs far under the table. "No luck for me, it seems, after hauling 'em from one hell to an other. I s'pose that niece of yours will make pets of 'em as soon as they're landed?"

Hayes made no reply. A crunching of feet on the coral outside, followed by a peculiar cry, took him across the beach to the jetty, where the whale-boat lay under the steps. Amati and Pao, his kanaka boatmen, awaited him silently. Something in their fear-stricken eyes turned him cold as ice.

"All the water aboard the schooner?" he demanded sharply. "Speak up, men. What's wrong?"

Pao made a sign towards the schooner, and grunted a single word in the vernacular. Hayes reeled backwards as though some one had struck him between the eyes.

"Pao speaks true, O captain," half whispered Amati. "Long before we put the water aboard we saw them lowering their dead over the side."

"There are two white men aboard," choked the buccaneer. "Did you see them?"

"I saw them, O captain," answered Pao; "but they would not speak to us as we lay under their chains. We heard the crying of many people below. We heard a voice call out that the scourge was killing them very fast."

"That's why he came in here," snarled Hayes. "It's one of his little jokes, I suppose—bringing his smallpox schooner into my lagoon. Damn him!"

LIKE a panther in his wrath he returned to the verandah, and

found it deserted. Peering into the darkness, he listened to the

slow savage laugh that came from the lagoon edge.

"Good-bye, Hayes. I'm going to send your eighty kanakas ashore. You'll find 'em useful."

"I guess they've come to the right island," answered the buccaneer lazily. "Eighty-two I make it."

Lewin's white figure was visible for a moment as he sprang into his dinghy two hundred yards from the trade-house. Leaning on his oars, he looked back at Hayes, and in the tropic silence each word rang with blade-edge clearness. "You flung your little niece at me like a Methodist parson, Bully. The sight of me made her sick, eh? It was nice of you to exhibit me in that way... slave owner, murderer, island blackguard. You wait, Hayes; I'll give you something in return that will freeze the heart in you"—the voice paused a moment as though taking breath—"like her eyes froze mine. Good-night, Hayes."

"You damned Herod!"

The oars splashed as the dinghy shot towards the schooner and faded suddenly in the soft darkness of the night.

Hayes leaned over the verandah and gritted his teeth. Lewin's threat to land a horde of disease-smitten kanakas on his island left him cold and speechless. Of the scourges black and yellow that some times swept over the Pacific, smallpox was the one he dreaded most. He had seen islands decimated, whole settlements turned into wind-blown skeleton heaps by a mere breath from a passing ship.

With a half-shaped thought flitting through his brain, he slipped into a palm thatched shed at the rear of the trade house and glanced round. From floor to roof it was stored with oil drums and naphtha tanks, salvaged some eighteen months before from the wreck of a storm driven barque.

The two kanaka boatmen followed silently, and at a word from the white man they rolled a naphtha tank from the shed through the white beach sand until it lay half submerged in the lapping water. A few blows from an axe stove in the side, and the naphtha ran with a soft glucking sound into the lagoon.

"This idea of pouring oil on the troubled slave-owner fits me," grunted the buccaneer. "He'll find that two can play at raising Cain."

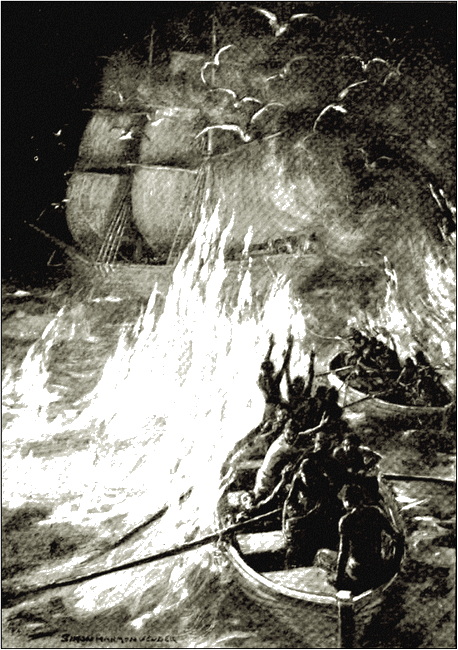

THE tide was ebbing; the slow-moving water cast up a prismatic

sheen where the naphtha flowed and spread over the lagoon

surface. Hayes, with the eye of a navigator, measured the

distance from shore to schooner, and told himself that the out-

drifting oil would float round Lewin's vessel within half an hour

at least.

A light winked dismally from the narrow poop, the clamour of voices, the wailing and curses of the terrified crew grew louder each moment. Boats were being lowered from her starboard side; black shapes were flung headlong into the thwarts until they lay in a squirming huddle above the gunwales.

Lewin stood by the windlass, his lank white shape silhouetted against the dark figures that staggered and crawled up from below. A kanaka with a broken oar drove the upstreaming mob towards the gangway. The crowded whale-boats threatened to fill as the last batch were tumbled aboard.

Lewin made no sign, uttered no command, but his lean, sinewy figure dominated the inferno of writhing shapes. A child's hand, a woman's upturned face crawling from the unlit pandemonium below, moved him not. His eyes were fixed on the strip of beach under the trade-house window where Hayes stood directing the movements of Pao and Amati.

A couple of candlenut torches flared in their hands. Seizing one hurriedly, Hayes stooped and held the flame over the naphtha- coated surface of the lagoon. Instantly the water bubbled with many tongues of violet-hued flames, that sped with a fluttering, gulping noise along the water's edge.

A flock of sea-fowl rose screaming against the sudden flare of light; the cry was answered by the sleeping gulls on the outside reefs. The lagoon seemed to flower with amber and purple balls of fire that roared and wheeled from beach to beach in wind-driven circles.

Lewin paused near the afterhouse, shading his eyes. Foot by foot the wide encircling zone of fire was drawn irresistibly towards him by the outgoing tide. Gripping the wheel, he roared out an order to the half-paralysed crew standing in the break of the poop.

It seemed hours before the small bow anchor was hoisted, ages ere the dew-drenched sails clapped noisily in the rising wind. The schooner hung in stays and whined like a sore-driven beast until the freshening wind drove her foot by foot towards the narrow reef entrance.

It was now a race between schooner and flames. Clouds of oil- smoke drifted skywards, blotting out the slow-moving schooner from the shore. A long blade-like shadow swept under the slaver's keel, smearing the unruffled deeps with its phosphorescent trail. A sailor crouching in the foresail boom knew it for a terrified shark slinking towards the open sea.

The whale-boats, with their freight of bewildered natives, clung desperately to a rope trailing from the schooner's stern, their fire-illumined eyes watching for an opening in the cyclone of blazing oil and smoke.

The whale-boats, with their freight of bewildered natives,

clung desperately to a rope trailing from the schooner's stern.

From each reef end and inlet came fresh streams of floating fire. It seemed as though Hayes in his fury had utilised his vast store of oil in expelling the disease-smitten vessel from Eight Bells lagoon.

The flame-driven schooner slewed for the reef entrance and wore through, foot by foot. Smoke poured from her timbers; her yards dripped fire and burning cord-ends. Above and around them the sour oil-smoke wove a terrible garment; it seized the eyes and throats of the crew and drove them choking and stammering among the shuddering forms in the hold.

Lewin, his coat wrapped round his face, clung doggedly to the wheel until the south-east trade carried him to the open Pacific.

DAWN found the fire-blackened schooner making east, a horde of

sullen islanders crawling about her deck. Hayes watched her

through his glasses from the reef end, where the gulls floated

and cried over the lanes of surf-washed coral.

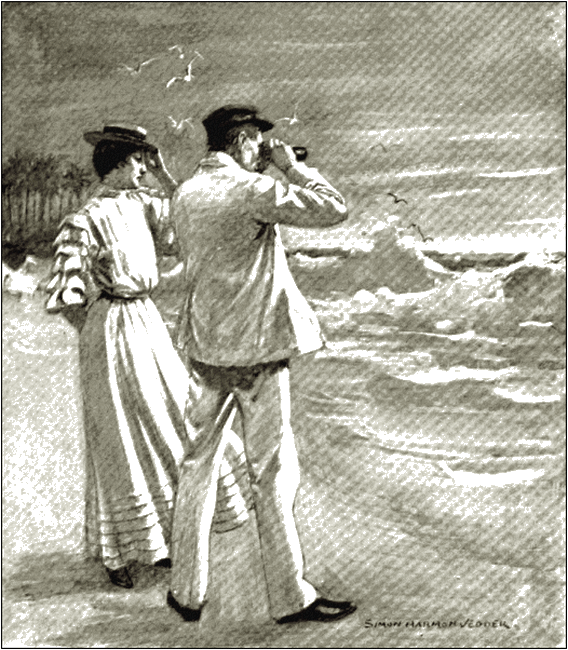

Hetty Bond stole from the trade-house and stood beside him, the wind in her hair, salt in her eyes where the mountainous surf flung itself against the outer barriers of the lonely atoll.

Hetty Bond stole from the trade-house and stood beside him.

"That's the last of 'em anyhow," said Hayes grimly. "Guess I couldn't see my way clear to let him turn my island into a morgue."

"It seems inhuman, almost fiendish, to serve those innocent natives as you have done!" answered the girl. "Was there no other way?"

Hayes lowered his glasses sharply and looked into her tear- filled eyes. "There was another way, Hetty: I could have accepted delivery of those eighty kanakas sick unto death. But we've no medicine, no doctor, and Lewin would have scattered them over the island before I could have raised a finger. See here!"

He pointed across the limestone barriers to where the huts of the village nestled beyond the wooded headland. "There are seven hundred women and men and children in that village, happy and God-fearing in their way—mission station and all thrown in. Now, I ask you, Hetty—are you listening?—I ask you whether it would have been fair to allow Ross Lewin to land his scourge-stricken rabble hereabouts. It is a disease that runs like a hound and kills wherever it stays. In two months —less—there would have been a big lonely cemetery stretched across this atoll, with you and me and a missioner in the middle of it; seven hundred quiet heaps of sand and coral to mark the spot," he added slowly.

The gulls cried and floated over the surf-washed reefs; the smoke of many cooking fires rose from the distant village and hung in streamers across the woods and plantations.

"Looks peaceful, doesn't it?" Hayes spoke thoughtfully, his smoke-blackened face to the village. "Not one of 'em dreamt last night how close they were to a big unholy funeral."

The swart fire-driven schooner slanted over the horizon and was gone. The girl sat and listened to the sea fretting against the reefs, and to her it sounded like the far-off crying of imprisoned souls.