RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"BULLY" HAYES was a notorious American-born "blackbirder" who flourished in the 1860 and 1870s, and was murdered in 1877. He arrived in Australia in 1857 as a ships' captain, where he began a career as a fraudster and opportunist. Bankrupted in Western Australia after a "long firm" fraud, he joined the gold rush to Otago, New Zealand. He seems to have married around four times without the formality of a divorce from any of his wives.

He was soon back in another ship, whose co-owner mysteriously vanished at sea, leaving Hayes sole owner; and he joined the "blackbirding" trade, where Pacific islanders were coerced, or bribed, and then shipped to the Queensland canefields as indentured labourers. After a number of wild escapades, and several arrests and imprisonments, he was shot and killed by ship's cook, Peter Radek.

So notorious was "Bully" Hayes, and so apt his nickname, (he was a big, violent, overbearing and brutal man) that Radek was not charged; he was indeed hailed a hero.

Dorrington wrote a number of amusing and entirely fictitious short stories about Hayes. Australian author Louis Becke, who sailed with Hayes, also wrote about him.

—Terry Walker

A TROPIC night with scarcely a movement under the bamboo-

thatched verandah, The shapes of half a dozen water-weary divers

were visible in the swinging hammocks; several trepang fishers

from the Malay prau Lambero Dynna, lay huddled in the cool

beach sand under the weather side of the house. A Burghis boy and

a snoring Dutch skipper, from one of the Company's luggers

obstructed the doorway; their chafed wrists end swollen necks

spoke of india-rubber diving jackets and submarine work among the

rich oyster swathes of Torres Straits.

Captain William Hayes strolled in from the darkness of the pier, where his schooner, the Three Moons, was undergoing repairs. He glanced shrewdly at the sleeping figures and entered the bar, where Mr. Ebenezer Wick, the Customs officer, was mixing a pink-coloured drink in a long glass.

'Rooting about the sea-floor for shell doesn't seem to improve these men's appearance.' Hayes nodded briefly to the huddled shapes on the verandah outside. 'When I begin to look like Bafio, the dago, I'll load my diving-boots with scrap-iron and stay in thirty fathoms.'

Bafio, the Italian 'skin' diver, crouching in a far corner of the bar, was not lovely to see: his reef-torn hands and feet, the bulging veins of neck and face, spoke of the torment endured by the naked divers, too poor or shiftless to buy a common rubber suit and helmet.

'Blind in one eye, too,' added the buccaneer, stooping over him. 'Got scrapping with a family of Japanese wrestlers last year. How did it happen, Ebenezer?'

The Customs officer explained at length how Bafio had caught a lugger full of Japanese poaching on his shell preserves one evening at the beginning of the pearling season. In his unthinking rage the Italian had challenged the oyster-thieves to a finish fight on the deck of their own lugger. And the little brown men accepted the invitation swiftly and with glee. They crowded him like a troop of pocket tigers, fought him throat and heel in a howling bunch until they lay on each other gasping and exhausted. It was a sanguinary little fight. Three of the Japs retired with broken limbs; while Bafio succumbed to a sudden garotte-hold and thumb-twist that left him short of an eye.

'Those big men don't impress me.' said Hayes, when Ebenezer had finished. 'Some of 'em are too blamed slow to race an oyster. If I had to storm Valhalla to-night, I'd ask for a packet of small men to stand by one.'

The buccaneer picked his way among the sleeping forms until he reached a spare hammock at the verandah end. Twisting a nipa leaf about a green cigar, he lay back and smoked thoughtfully, while the tide fretted and whispered over the endless stretches of sand. Mr. Wick sat beside him somewhat obsequiously, for in that lone region, where infinity throbbed between jungle end sea-line, the voice of the white man was like music in Hades.

'You don't remember Oedler, the freak-agent, who walked through Queensland years ago looking for chow giants?' went on Hayes thoughtfully. 'He spent eighteen months hereabouts trying to run down a white aboriginal—albino, I suppose—and was nearly speared for his trouble.

'Oedler stood on the beach at Bowen one day and signalled me just as I was crossing the bar in my schooner the Daphne. 'I've some passengers for you, Hayes,' says he, 'If you've any accommodation.'

'At that time I would have accommodated a family of baby elephants If they'd been offering. I knew Oedler in Sydney, when he was running a five-horse circus—used to paint his own nose when he couldn't afford a clown—until the people got to like him for his pluck. They like pluck in Sydney, especially when it runs about a circus with vermilion on its nose.

'He stood on the beach with the broken end of an old trombone in his hand, and blew speeches at me for thirteen minutes. I gathered from the noise he made that he was the proprietor of a family of freaks, and wanted to take them to a big circus in Shanghai.

'Now I was willing to carry baby elephants, but I didn't want any long haired Circassian ladies abroad my schooner, nor any spotted men from the jungles of Borneo. I had carried show-people before, and I always managed to quarrel with the spotted man. They put on airs.

I once took a professional fasting man from Rockhampton to Sydney, and his appetite caused a famine onboard. We finished the trip on mangoes and tolled seagull.

'Oedler seemed annoyed when I asked it he'd got any fasting men in his collection of freaks. He blew denials at me through the trombone.

'I needn't be afraid about this company,' he said. He was willing to cover their appetite with a five hundred dollar insurance risk.

'Then he blew some more explanations, and finished by asking me to keep calm.

'I thought it over for two minutes, while he performed a solo about the passage money and the twenty per cent, reduction usually allowed to travelling-circus people. I decided to take him.

'He retired to the little wooden hotel that lay behind a cane field, while we ran the schooner closer inshore and made fast to a floating oil drum used for a buoy. The mate, Bill Howe, dusted out the state-room, and persuaded most of the cockroaches to go to bed before the freak family came aboard.

'Nobody ever complained about our cockroaches. They were the most obedient insects that ever owned a three-hundred-ton schooner; and they always knew when Bill was angry. He came on deck wiping his brow.

'All clear and roomy below?' says I.

'Heaps of room, Cap'n, if the 'roaches will only keep to their end of the ship,' says he. 'They're sure to feel a bit hurt at me drivin' 'em from the state-room.'

'I never understood Bill's kindness to insects. Some people said he drank heavily in the old days, and broke one of his feet jumping on a blue centipede that didn't belong to this earth. You never knew for certain what Bill was jumping on.

'We sighted Oedler doming from the hotel followed by his freak, family. The lady was about three feet high, and walked with some dignity beside Oedler. A girl of eight or nine led the way, bowling a hoop as she ran towards the beach.

'Nothing queer about these little freak people,' says I to the mate. 'I've seen shorter women looking after a husband and a family of thirteen.'

'Wait a bit, Cap'n.'

'Bill leaned over the side and pointed to something moving round a corner of the cane-field. It looked like a tree at first, swaggering along; but a peep through the glass showed that it was a man, all legs and body and head. When he drew level with the others on the beach we saw that Oedler only reached up to the third button of his waistcoat.

'Family giant,' said the mate. 'Wonder if he unscrews at the knees or comes to pieces?'

'The crowd came alongside ,in a shift and the midget lady was first up the narrow gangway, followed by the girl with the hoop. Oedler panted after them, and introduced us. The midget shook hands warmly with me, and said she hoped we'd have a nice passage to China. Then, standing on her toes beside the rail, she asked me to help her big husband aboard. He was not used to climbing up ships, she said.

'The unwieldy show giant sat in the skiff staring at the steep gangway as if it were a blamed fire-escape.

'Bit gone in the knees, p'r'aps,' says Bill. 'Maybe he don't unscrew after all.'

'Now, Mr. Longbody,' says I, 'when you've finished growing you'd better come aboard.' I didn't want to hurt his feelings, but I was afraid he might come to pieces if he stayed in the sun too long.

'Come along, David dear,' shouted the midget lady. 'Everything's quite safe. The gangway won't fall.'

'The giant looked up at us like a frightened schoolboy, then gathered himself together as though he was going to shin up a lightning-conductor. I've seen landlubbers claw the side of a ship and perform like acrobats when climbing abroad from the water, but I've never seen a circus giant lie on his chin and ears to do it. He seemed frightened of the water under him, frightened of the spars and rigging above, and his eyes bulged as he stuck midway up the narrow steps and refused to come farther.

'Bill Howe tried to lasso him, while the cook stood by with a boat-hook and pushed him off when he threatened to bump. There was a bit of a swell on, and when Bill got the noose over him, and the cook fastened him with the hook, he came aboard head first into the pantry,

'The crew crowded round to get a glimpse of the freak-man. From foot to head he was a pile of muscle and simplicity. Oedler had found him and the midget lady performing inside a threepenny bush circus near Charters Towers. He was paying their passage to Shanghai on the chance of hiring them to one of the British or American show people.

'The giant's name was David Clipp. His mother was an Australian bush-born woman, his father a Devonshire farmer who'd settled in Queensland somewhere in the 'fifties.

'The little girl with the hoop was the result of David's marriage. I guess she was shyer than a wood-pigeon at first, but she soon got to know the sailors. They used to spend most of the mornings making oakum dolls and painting the blamed ship any colour that suited her fancy.

'The midget kept to herself during the trip north. Like most women who marry giants, she was pale-faced, and a bit eerie. The sort of creature that would have gone well in double harness with a poet—if she'd been two feet taller,

'Big David seemed out of place on my three-hundred-ton schooner, The cabin was three sizes too small; we had to saw planks out of the walls to allow his legs to straighten whenever he sneezed or turned in his bunk.

'We stopped three days at Thursday Island, and took aboard more passengers for New Guinea and the Philippines. Most of them wanted to climb over the rail when they saw David come out of the stateroom. They a mistook him for Fo Fum, the man-eating giant in the story-books. Several of the crew were over six feet, but they were mannikins beside David Clipp.

'I never had much faith in giants; they're mostly a shingle short, and useless as workers. David was the most peaceful chap you ever saw —and the laziest. When he slept on deck it was pretty hard to pass without treading on his face or hands. Bin, Howe used to walk barefoot over his neck and brow, and nothing particular happened.

'We reckoned, after a while, that the big fellow hadn't any feeling in his face—the mate said it was as useful as a doorstep when he wanted to reach the taffrail or poop. You din't know how big or small a man can be until you sail with him in a three-hundred-ton schooner.

'At Sumbawa we stuck on a sand-bar, and the whole crew got out to heave her over. We sweated for three hours with pulley-blocks and boats doubly manned without shifting her a foot. David leaned over the rail watching us solemnly with his big childlike eyes. Then it occurred to him that something was wrong. Without a word he climbed down and stood waist deep under the schooner's stern. Resting his shoulder against her side, he heaved, and lifted until the veins of his forehead and throat bulged.

"Heave,' says he.

'We heaved, and the ribs of the schooner whined and cried out as she slipped off the bar. Nobody complained about the size of David's feet and hands after that affair. But he had his weak spot—his heart was no bigger than a mallee hen's. When a thing moved towards him without notice he grew pale and over- thoughtful. He was afraid of things—of the sea, and the big-voiced sailor-men, or a sudden scuffle between a couple of quarrelsome deck hands.

'North of Batavia a big old-man cyclone struck us, It flung us on our beam-ends, and fluted about us like a white wolf, for eight hours. The sea became yellow as whisky, and the lightning seemed to leap at us from the bed of the ocean.

'I found David in his bunk, his grey face peeping from the blankets, the fear of the almighty sea in his eyes,

'Come out and give the men a hand,' says I, tugging at the bedclothes. 'Four of them are hurt badly. Two have been washed overboard, Come out!' and I hauled at the clothes pretty smart.

'Shifting a blamed iceberg would have been an easier job. Only his set face and bulging eyes could be seen. His wife and child sat in a corner of the cabin, staring like sheep at me and the mountain of flesh wrapped in the bunk-clothes.

'The little girl sized up tho affair sooner than the mother. She crept to the bunk and touched David's arm.

'Daddy,' says she, 'the Captain wants you to go on deck. The crew are hurt.'

'I stood over him half savagely, and shook him roughly, for I saw that he was trembling like a little child.

'Your father's no good to me, my girl,' says I. 'It's a man I came down for.'

'We were through that bit of weather, and the calm days that followed gave us a chance to Jury-rig and repair most of our battered top-hamper. David would never meet my eye afterwards. We called him the big soap man, and the cook threw potato peelings over him whenever he passed the galley.

'One day my cabin-boy, a Sydney rat of twelve, kicked him out of the stateroom because he had burnt a hole in the table-cloth with a match. David took the kick meekly, although a flip from his hand would have broken the lad's neck.

'There's a lot of tragedy about the wives of these big wastrels and cowards. Their wives understand, and their children cry over it. For every white boy and girl likes to think their daddy is a brave man, who can take care of little children and weak women.

'Oh, we were sorry for that midget lady with the quiet, dreamy eyes, and guess there wasn't a man on the schooner who wouldn't have stopped a bullet to shelter the little lassie, who had the misfortune to be the daughter of a big, aimless coward.

'Matters grew worse when the little dreamy-eyed woman came to me one day and began explaining her big man's failings.

'Captain Hayes,' says she, 'you are misjudging my husband. He is kind and gentle to me, his wife, and he loves his child as dearly as any man, What do you want him to do? Other men beat their wives and children. He is tender and—and—'

'Gone in the heart, ma'am,' says I, sorrowfully.

'What do you expect of him, Captain Hayes?'

'Nothing, ma'am,' says I. 'I'm sorry for him. We're all sorry for you. The world's got no use for white-lipped cravens.'

'Guess that struck home, and I shouldn't have said it. But a sailorman can't paint a white coward red! He can't theorise about a weak heart and call it a tiger's beating inside the breast of a man.

'After that we, left David alone. Sailors got tired of nagging a harmless thing that won't bite back. We simply stepped on his face when he was in our way; the cook gave him pan-grease when he passed the galley, or a drop if hot water to keep his feet from feeling cold.

'It was the year old Admiral Tung's fleet of black junks was raising Cain among the China traders south of Hainan and Bangkok.

'We sighted a high-pooped dragon-headed junk at dawn, about a week after leaving Manila. It stood against the sky-line frowsy as an unclean bird, its ragged lateen sails slanting vulture- like, ready to pounce on the first unguarded vessel that heaved in sight.

'She saw us, and her sails swooped round with a clatter and a bang. Guess there wasn't enough wind to elevate a thistledown, but she came with the speed of a small typhoon, her long sweeps eating up the miles like the wheels of an express train,

'There was no wind to dodge them in that tropic sea. They began by dropping small shot around us, but no one ever yet accused a Chinese pirate of straight shooting. It isn't their game. Years of study and careful instruction go to the making of a good gunner, and the junk-men never pinned their faith in cannonading tactics. It's the way they grapple and swarm over your decks that makes 'em hard as wolves to repel.

'They were up with us in half an hour, and their heavy three- pronged grappling anchors were clanking over our sides before we bad collected our small stock of arms and ammunition. They opened on us with a volley of stink-pots that fumigated the air for miles. Our jury-rigged mainsheet went overboard like the broken wing of a flying-machine the moment their stiff lateen sails collided with our rigging.

Our jury-rigged mainsheet went overboard like the broken wing of a flying-machine.

'Then from nowhere in particular came the buzzing of small bullets and the humming rattle of chain and bolt shot that fairly rooted the sticks out of us. It seemed for a minute or so as if the big dragon was blowing hot scrap-iron into us. A piece of chain knocked me endways, and I lay in the scuppers with a broken arm and a cashed rib that sent a taste of death into my mouth.

'I'd seen many kinds of shambles in the 'pelago, and I'd run my schooner into a black vendetta in New Britain once, when you could have built a winter residence with dead Kanakas. But these Chows got us before we could say Amen.

'David's little girl was standing under the bridge watching the strange black flag fluttering above us, and the curious yellow men swarming over the dragon-headed poop. A musket flash lit up her face suddenly: I saw her turn and fall in a heap almost beside me.

'The junk ground against our counter until her big brass dragon bulged over the rail. The enormous lateen sails seemed to shut out the sun when the swart-faced blackguards swung hand over hand across our stern. Some of the crew fired and took shelter in the galley, where the mate was busy loading fowling-pieces and pistols.

'David came up from below just as a driven beast walks. His big body stooped suddenly as he looked at the little white shape huddled under the bridge, A blood spot showed on her face and pinney; there was blood on her hand where she had put it up, as though to touch the swift, noiseless bullet when it struck her.

'His face seemed to slacken; his eyes grew round as two pieces of money; his pain and astonishment showed like a fever-sweat on his brow and chest.

'He took up the child and carried her below quietly. And amid the yelpings and clatter of the boarding junkmen he spoke unmoved to the little woman shivering in the cabin doorway.

'Mounting the stairs again, he stood under the broken poop where the colliding junk had torn the bridge-stays asunder. A six-foot length of broken stanchion lay on the deck. He picked it up slowly, and it whistled the air when he thrashed it up and down to test its strength and weight.

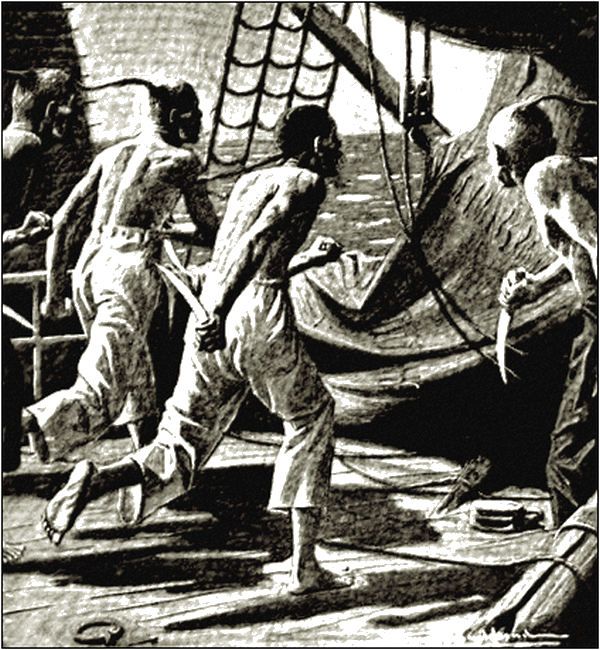

'The litter of broken spar-ends and shredded sails prevented the junkmen from seeing David until he ploughed his way aft to where the slant-eyed devils were pouring below in quest of loot and treasure. A few had gained the stateroom, the smashing of glass and furniture told us that they were hunting for opium and loose dollars in the lockers and cabin drawers.

'Another crowd swarmed over the rail, their short crooked knives rippling in the tropic glare, They did not see David until he broke through the litter of spars and fallen tophamper, Then they yelped at sight of the man, at his white lips and round eyes, the foam that fell like tiger-froth from his big soft chin. No god, black or white, had ever looked at them with the eyes of David Clipp.

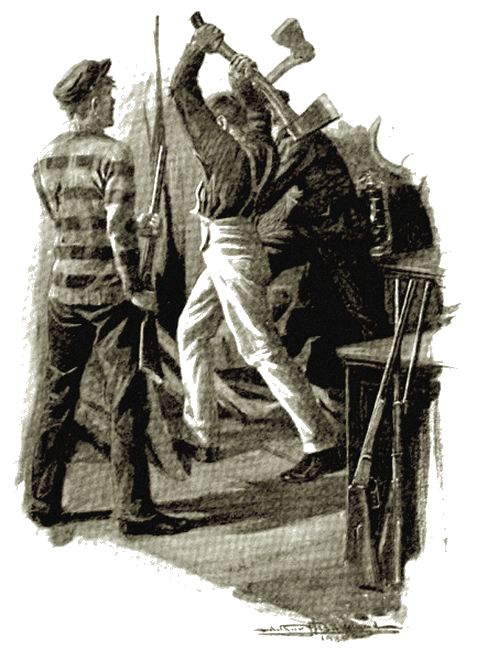

'They drew together until they were a solid bundle of knife- points, and considered him. He stood seven paces away, his shoulders stooping, his lips mumbling what seemed to be a child's nursery song. There was no hate in his eyes, only the grey stare of the Northern baresark, His muscles shook and heaped under the white flesh as he sprang at the bundle of knife-points. The bar bit and slogged into the reeling line of steel. He was across the deck and back again nimble-footed as a schoolboy, cleaving and braining with a horrible left-to-right sweep of the bar.'

The bar bit and slogged into the reeling line of steel..

Hayes paused awhile and re-lit his half-smoked cigar.

'The Chinese pirate is no coward,' he continued huskily. 'He's got to be brave, or he'd starve at the game. But he likes all the soft fighting he can get, although he'll face the lightning of small guns until he's half blown out of the water. Deck fighting is pirates' business; shoulder to shoulder, knife to knife, they hit you in a pack; and if you haven't been trained to whip wolves and tigers It's much easier to lie down and present 'em with your funeral expenses.

'But the crowd that swarmed over us had never been hit at short range with, a six-foot bridge-stay. They'd never been hit to leg or brained on a dry wicket. David played 'em singly and in bundles. They broke, and scurried like rats to the schooner's rail, they fought each other in their wild haste to dodge the giant's murderous blows. Like a bear among puppies he killed them In groups before they reached the rail. Their short knives were useless against his paralysing onslaught.

'His great height and proportions filled them with superstitious fear. Some cast themselves into the water, mutilated and crippled; others crawled into the alley-way holding up their hands in token of surrender.

'David leaned on his weapon panting and weary; around him a dozen battered shapes, unable to rise or speak, Below in the stateroom were a crowd of yellow ruffians stripping and smashing everything within reach. Their shoutings ceased for a while, as though they'd grown suspicious of the silence on deck. Three of them came to the foot of the stairs and looked up.

'David was leaning on his bridge stay above, breathing heavily. The junk had sheered off on the starboard tack, firing into us wildly from time to time, and killing one of my Liverpool mainsheet men named Johnson.

'It was about time for me to give an order, 'Now, lads,' said I, crawling to the crowd in the galley, 'give the big fellow a hand to clear out the chinkies below. Down the hatch with you, and rip away the bulkhead partition, and chase the yellow scum upstairs into his arms.'

'The men were below before the order left me. I heard the axes at work beating in the planks that separated the fore-hold from the stateroom. While above, in the hot sunlight, stood David Clipp, the sweat of battle on his big throat and brow. But the light of his baresark rage had gone from his eyes; his jaw hung, and his knees grew slack as a sick man's.

I heard the axes at work beating in the planks

that separated the fore-hold from the stateroom.

'The pause in the fight had given him time to reflect over the mutilated shapes huddled around him. It was the silence that touched him most; if someone had struck at him or cried out from the heap of skull-battered men his courage would have held fast. To make things worse, a squat, bull shouldered junkman crawled from the heap exposing his face and body pulverised into a shapeless mass of bone and flesh. He looked at David long and steadily, and his head nodded.

'David's face whitened as the eyes looked into his; he reeled across the deck dragging the bridge-stay after him.

'Quick!' I called to the lads below. 'Our Davy's turning cold.'

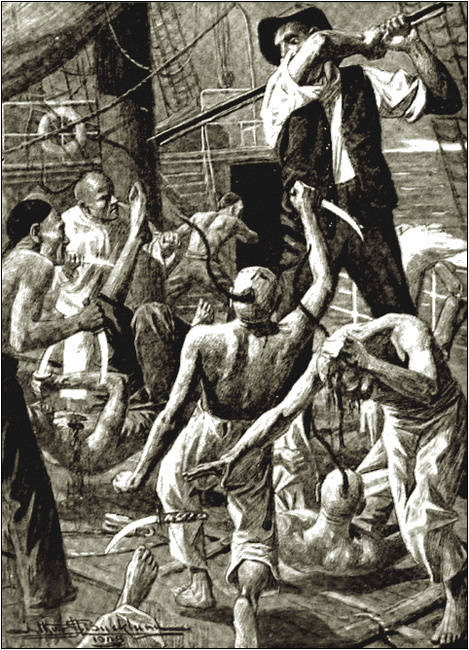

'The horde of looters in the stateroom turned like trapped wolves as the bulkhead partition crashed in, leaving a hole big enough to ram a dozen gun-barrels through. They crowded up the stairs, but stayed half-way at sight of the shambles on deck, and the blood-weary giant leaning against the mast.

'He saw them, and his legs shook with fear. There was no time to curse his fainting courage. If the yellow devils were allowed to gain the deck or their second fighting wind they were hardy enough to hold the schooner until the high-pooped junk grappled with us again.

'They came up the stairs two abreast, measuring David foot and eye, like jackals driven towards a sick lion. The sight of their short crooked knives was more than he could stand. A hoarse whimper came from him. He looked at them once over his shoulder, and, quick as a frightened dog, slunk for'ard, leaving the stairhead clear.

'The devil take you, David!' said I.

'Just here a cry came from below, and I knew it must be from the woman sitting beside the little child in David's cabin. Her voice rose like a wail, as though she had just realised her loss,

'The sound of her voice brought David round with a jerk he listened for the cry to repeat itself as the yellow looters streamed up from below. Their rat-like instincts told them that the big man's courage ran in streaks. They leaped yelping at him as he turned, But David, the coward, was not to be caught by a bundle of loin-cloths and a dozen stabbing arms. The woman's cry had stiffened his courage. Pivoting nimbly, he met them with a straight swing of the bar, followed by a murderous in-and-out chopping that broke them into a limping, howling mob.

'It was the first time I had ever seen a show-giant cross-cut with a six-foot bridge-stay, and my ears caught the dull whooping sound of iron striking against flesh and bone.

'A half-maddened junkman ducked cunningly and ran in under the whirling bar, his strong hands clutching at David's ankles. The, giant sprang three feet in the air and his right foot came down on the ruffian's face, squeezing it to the slippery deck. I crawled from the house, pistol in hand, but I was afraid to fire for fear of hitting David. And it seemed to me that the fight only lasted about ninety seconds; it was over while the blood was hot on the bridge-stay.

I crawled from the house, pistol in hand.

'My crew came up with a rush, from below, but the work was over; and they crowded round David, who had flung himself face down on the deck beside the pigtailed heap of Mongolians under the rail. One lay with knees updrawn and fists thrust out, another was doubled over the stern-rail, where the bridge-stay had broken his back as he tried to crawl over.

'David groaned and covered his face as they pressed round him; he had cast the bridge-stay overboard, and his eyes had the look of one who had been licking, the floor of Gehenna!

'Come, come, my lad,' said the mate; 'smarten up a bit and go below.'

'They gave him a stiff nobbler of spirits, for we knew that he would cry like a child the moment he faced his wife in the cabin.

'The junk had drifted far to lee-ward. The few fighting men who remained on board had witnessed the little Homeric fight on the schooner's deck; and, to a man, they were in no mood to face another swinging six foot bar, that piled up the dead faster than grape-shot or modern ammunition.

'They carried me below, and I saw David's wife bathing the shot-wound on the little girl's face. The big surprise came when the child showed signs of life; and before night she pulled round, looking quite cheerful. The bullet had touched her right cheek between eye and ear, and David sat on the cabin floor and hugged her when she asked for a drink of water.

'We were picked up two days later, in an unseaworthy state, by a Hong Kong passenger steamer. There was a Calcutta doctor on board, and he looked after David's little girl like a white man and a father.

'We were landed at Swatow in better health than when we started. And, barring a slight scar on the right cheek, the girl was as lively as ever.

'David went to Europe with his agent, and fell in with Barnum's people. I heard afterwards that he was the butt of the circus. The dwarf and the 'smallest man on earth' treated him unmercifully. They used to nail his boots to the floor and sew up the sleeves and lining of his clothes.

'I was told that a crowd of stable boys and circus mannikins gave him a terrible drubbing one morning, at the back of the elephant sheds. They said he wept like a girl while the young fiends laid on him with switches and brooms.

'Guess I'm pretty careful about hitting giants these times, especially the big, soft-eyed men who tremble when you show them your boot-end. You never know when they will rush round and paint the deck vermillion with a bit of broken furniture or a bridge stay.'

Hayes rose somewhat wearily from his hammock. Day was breaking along the surf-fretted east, where a dozen pearling-luggers stood motionless against a lip-red sky. Smoke from the trepang huts floated across tho bay. One by one the pale, water-weary divers limped from the verandah, yawning and rubbing their reef-chafed bodies. Bafio, the one-eyed, followed to the boat, waiting to carry them to the Vanderdecken Reef, where the golden-edge shell lures white and brown man to the uttermost depths.