RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

The Popular Magazine, October 1908, with "The Gold-Throwers"

"BULLY" HAYES was a notorious American-born "blackbirder" who flourished in the 1860 and 1870s, and was murdered in 1877. He arrived in Australia in 1857 as a ships' captain, where he began a career as a fraudster and opportunist. Bankrupted in Western Australia after a "long firm" fraud, he joined the gold rush to Otago, New Zealand. He seems to have married around four times without the formality of a divorce from any of his wives.

He was soon back in another ship, whose co-owner mysteriously vanished at sea, leaving Hayes sole owner; and he joined the "blackbirding" trade, where Pacific islanders were coerced, or bribed, and then shipped to the Queensland canefields as indentured labourers. After a number of wild escapades, and several arrests and imprisonments, he was shot and killed by ship's cook, Peter Radek.

So notorious was "Bully" Hayes, and so apt his nickname, (he was a big, violent, overbearing and brutal man) that Radek was not charged; he was indeed hailed a hero.

Dorrington wrote a number of amusing and entirely fictitious short stories about Hayes. Australian author Louis Becke, who sailed with Hayes, also wrote about him.

—Terry Walker

TWO Chinamen sat in the house of Willy Ah King, gold-buyer and dealer in illicit pearls. Before them on the marble-topped pak-a-pau table lay a piece of rough chocolate-coloured stone the size and shape of an ordinary egg. From time to time they balanced it in their palms with the craft of geologists, rubbing and moistening it with their lips until it sparkled at many points.

"There is more gold in it than dirt. The yang-jen who own the mine are surely blind."

"What are the barbarians digging for if they cannot see gold in this stone?"

"The bottom reef," answered Willy Ah King. "They know nothing of ore- values. They break this schist from the surface-crop and throw it aside as worthless. Unless they see yellow metal shining in the stone they have no belief. The field is crowded with sailor-men, who look for nuggets instead of treating their rich alluvial."

The Chinamen addressed each other in their throaty Nankingese, with occasional outbursts of celestial wit, pointed as steel, and aimed at the stupid sailor barbarians who owned the mine at White Marble.

With an iron "dolly" they smashed the egg-shaped stone until it lay fine as powder at the bottom of a mortar. Placing the powder in a tin dish, they washed and sluiced it with water until only a long furrow of gold remained in the dish.

Willy Ah King drew away from his two friends as though the magnitude of their discovery had appalled him. A morbid, slant- eyed thief was Willy, his four jewelled fingers resting on his ox-like hips. Only the day before one of his coolies had stumbled across the egg-shaped stone lying at the back of a mine owned by Captain Hayes. It had rolled down accidentally from a small heap of tailings packed away at the windlass head.

The coolie, an experienced fossicker, had straightway brought the stone to his master, with the news that a hundred weight or more had been dumped aside as valueless by the white sailor fools in charge of the mine.

"But how shall we get this stone from under the barbarians' eyes? All day and night the white captain and his four workers watch their claim. If we are caught stealing it they will shoot us like pigs. Yet, if we wait too long some of their friends will tell them its value. The barbarian captain has the eye of a dog, the tooth of a tiger."

"And a heart to squeeze," snarled Willy Ah King. "The stone is ours. I was born to make a fool of this Hayes. You will see... to-morrow."

Emu Creek sweltered in the glare of a Queensland noon. From every drift and gully came sounds of pick and spade. White men and yellow stripped to the waist slaved in malarial mud on creek, bank, and flat. A mile from the town, almost shut in by Leichardt pines, a wind lass stood over a wide-mouthed shaft. Captain Hayes sat on an upturned bucket and wiped his face and eyes.

Two months of Titanic labour, tunnel ling and cross-driving beneath a poisonous growth of jungle roots and in-dripping creek slime, had resulted in a heap of chocolate-coloured stone, that lay at the head of the mine. Five hundred yards away on their line of reef other men were cleaning up thirty ounces of gold a week, while a few had obtained as much from a single bucket of wash dirt. Hayes was assisted in his work by his mate Howe and a Frenchman named Louis Blin. Blin's scanty knowledge of reef-work had been gained in the nickel mines of New Caledonia. Compared with the quick- moving, excitable Frenchman, the mate was a slow worker, and he leaned on his pick in the wet under-drive to complain of the slush, that fell thick as porridge from the roof of the tunnel.

"Better to 'ave kept to the old schooner, cap'n," he growled more than once. "The sea gave us bread and meat; the land offers us a blamed heap of stones."

"The earth's got a softer bosom than you think, Bill," responded the buccaneer. "When we hit the reef at the next cross cut we'll be tearing out the nuggets with our hands."

At that moment a small Chinese boy appeared, running swiftly in their direction. Twenty yards in his wake appeared a full- grown aboriginal carrying a wommera. The boy ran straight for the mine, and at sight of Hayes standing at the windlass he screamed a word that brought the others hurriedly to the edge of the claim.

Bill Howe clambered up the windlass rope and gaped at the on- coming black fellow. Panting and almost frantic with fear, the boy flung himself at their feet. "Myall man wantee killee me!" he choked. "You savee me quick. He follow me one two mile tloo bush an' sandhill."

"Wait till the black beggar comes closer, cap'n," whispered Howe. "When ever I'm low-spirited Providence always provides me with a nigger."

Hayes leaned from the shaft-head and addressed the approaching aboriginal. "If you show your black nose in here, my son," he said coldly, "I'll flatten it with a bullet."

"Waste a bullet on that spindle-legged grub-eater! Not much, cap'n." The mate stooped, picked up a piece of chocolate-coloured quartz from the tailings and hurled it at the black fellow's head. Ducking cleverly, the myall placed a tree between himself and the loud-voiced mate.

"Yah! you gibbit China boy!" he shouted defiantly. "Mine thinkit him one yellow debil. Baal."

Another piece of brown quartz struck the tree with terrific force. Hayes laughed boisterously each time the shining black body danced round the trunk to avoid the mate's well-aimed shots. Struck on the foot and hand, the enraged myall seized a large white stone and hurled it with a boomerang force in their direction. The shot told, and the mate reeled backwards as the stone collided With his shoulder.

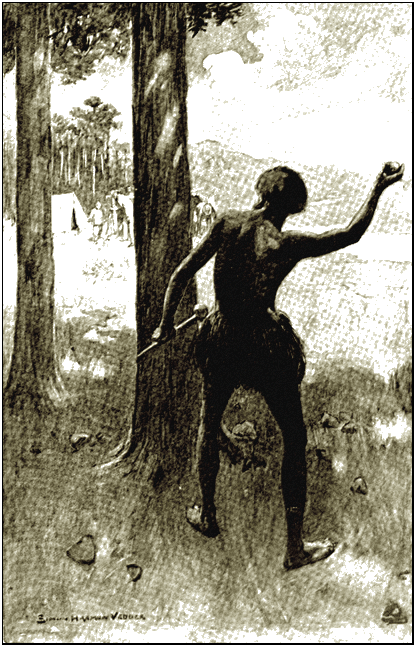

Struck on the foot and hand, the enraged myall seized a large

white stone and hurled it with a boomerang force in their

direction.

The myall yelled joyously, and stooped for another piece of rock. Hayes ducked nimbly, as it smashed with the force of an exploding shell against the windlass. "I don't want to gun an unarmed man," he said huskily; "but this fellow will wreck our mine if he stays long enough." Hereat the buccaneer joined the quartz-throwing duel with great vigour, hurling huge knobs of chocolate-coloured stone at the enraged aboriginal.

Driven from cover of the trees, he retreated with angry side- glances in the direction of the township. The white men breathed for a moment and regarded the Chinese boy silting near the windlass.

"You welly good to savee my life," he said meekly. "Me cally water Horn cleek any time you like. Me helpee you workee." His eyes shone with gratitude. The buccaneer patted his head reassuringly and warned him against wandering in the scrub, where the treacherous coast- blacks kept a sharp look-out for plump little Chinese boys, who fitted so nicely between their red-hot cooking-stones.

The sun vanished over the jungled headland, and from the rotting mangrove swamps came hosts of viperish mosquitoes, driving the white men into their tents. A few slush-lamps flared around the big camp of Mongolians, indicating their ever-present pak-a-pau shops and opium "joints."

Two pig-tailed figures stole across the sandhills and crouched in the shelter of the Leichardt pines, where the duel of stones had occurred only a few hours before. On their shoulders were two empty sacks. Moving craftily between the pines, they examined carefully the scattered pieces of brown quartz before dropping them into the bags.

The voices of the white men reached them. Occasionally the shadow of the buccaneer swung across the lamplit tent whenever he rose from his seat to point an argument to his friends. Groping in the stiff spear-grass, the two celestials slunk from shadow to shadow, until the last knob of quartz was safely stowed in their bags. Then they departed silently as chicken thieves.

At the first streak of dawn Hayes and the Frenchman were astir. Blin took his turn at the windlass bucket, while the mate prepared the dynamite for blasting the reef in the lower workings. Several bush tracks led from the town to the mine. Jungle and mangrove swamp shut out the north and far west; flocks of pigmy geese trailed towards the reed-choked waters at the creek mouth. An inquisitive emu thrashed through the near scrub, filling the morning silence with its strange booming note.

A solitary swagman emerged from a near bush track and halted within a few yards of the mine. By his dress, Hayes knew him for a wandering German looking for work, one of the numerous handy men who eke out a living in the small Gulf towns.

Camping within a few yards of the mine, he busied himself with his fire and billy, without addressing a word to the three men at the windlass head.

As the day advanced the German amused himself mending his tattered clothes, crooning softly as he plied his needle and thread. From time to time Louis Blin paused to listen, a deep frown wrinkling his sunburnt face. From a soft, crooning note the German's voice rose lo a well-defined song, that soon rang with patriotic fervour through the scrub-covered gully:

Lieb Vaterland magst ruhig sein! Lieb Vaterland magst ruhig sein! Fest steht und treu Die Wacht, die Wacht am Rhein!

The Frenchman listened, and his face crimsoned suddenly. "You... get — from—here!" he snapped. "Take ze noise away."

The German stitched away with great vigour, his back half- turned to the mine.

"Der Deutsche bieder, fromm und stark," he chanted carelessly.

Blin swung round, with angry blood in his listening face. "Ze pig come here to insult," he choked.

The German turned lazily at the moment a piece of chocolate- coloured quartz whizzed past his head. His attitude changed instantly. "Himmel! I gif you somedings for dot!" he roared.

Before Hayes could interfere, the two were bombarding each other with the ferocity of implacable foes. Stones and quartz flew about the mine-head. Each time Blin hurled a piece of heavy chocolate-coloured quartz from the heap of tailings the German responded with stones from the edge of the gully.

Hayes stepped forward and thrust the Frenchman aside. "Enough," he growled. "The fellow's a bit mad."

The mate emerged and spoke soothing words to the half-frantic German. A piece of tobacco presented feelingly brought about an honourable peace. The pelting had been of the wildest description, and neither man was hurt.

At midday the German departed, swearing in a high-pitched voice that Blin was the finest fellow in Queensland.

"Didn't I say he was mad?" Hayes returned to his work underground, where a tunnel was being driven at a depth of fifty feet.

Late that night the two Chinamen again crossed the sandhills, filling their sacks with the chocolate-coloured quartz that lay where the German had camped.

"There is still a small heap of gold- stone within the mine," whispered one in his fluent Nankingese. The German dog earned the money we gave him to-day. We must not send him again. The barbarians would suspect—"

"It is not easy to find the stone in this dark," answered the other. "Only for its great weight and colour I could never separate it from the other rocks."

The following day brought a cool sou'- easterly breeze from the Pacific, and the three white workers at the mine lingered over their breakfast before descending into the damp heat of the tunnel below.

"It isn't a bad world," said the buccaneer, sipping his coffee and inhaling the pure air from the sea. "I must say that most of us don't understand each other, or there'd be no need for cheap ammunition or bailiffs."

"I always said it was a good world," broke in the mate enthusiastically. "There's times p'raps when it'll sell you a cheap 'orse or forget to bring back your umbrella; but nine minutes out of every ten the world is playin' dead honest. I can prove it."

The mate had risen from his seat and was about to approach the windlass; turning sharply, he pointed to something wandering between the near sandhills. "Goats!" he cried hoarsely. "Of all the pests that crawl into a man's life!"

Even the buccaneer swore loudly at sight of the mischievous herd of tent- raiders swarming over the scrub-lined hummocks. No more voracious quadruped exists than the half-bred angoras that infest the mining camps of North Queensland. Clothes, food, and articles of every description vanish in their wake. Nothing is sacred from their insatiable appetites. And the miner in his desperation is often compelled to sit up half the night to protect his food-supply and wearing apparel.

Five gaunt animals were already skirmishing round the mine; others soon appeared on the distant hummocks, until it seemed as though half the goats in the district were being driven towards them.

Their approach was met by a fusillade of chocolate-coloured stones that turned their leaders in an opposite direction. Others ventured near, but the three men poured a terrific volley from the mine head, driving the stragglers to the shelter of the bush.

"Ate a pair of my watertight boots last week," panted the mate, hurling a final piece of quartz at the receding goats. "Blamed mystery how any four- legged creature can find pleasure and enjoyment eatin' watertight boots. The only pair I had, too," he added dismally.

Hayes confessed that the harmony of camp life had been disturbed by the unaccountable inrush of goats. "Seems to me," he said slowly, "that we're doing a lot of stone-throwing lately. I haven't shied a pebble for years, not since I was a boy; yet the last two days I've been knocking the scenery to pieces with lumps of quartz. Funny, isn't it?"

An hour later they received a visit from an old Victorian miner named Jardine. He entered the mine enclosure and shook hands warmly with Hayes. Some bond of friendship lay between the two men, for they chatted briefly of the days when gold wardens and mounted troopers were unknown in certain parts of Queensland.

Jardine cast his shrewd, experienced eyes over the claim, and smiled at the rough methods employed by the three men of the sea: the rickety windlass, the uneven cross-cutting, the badly timbered sides of the shaft, that permitted the water-flushed sides to cave and bulge dangerously over the workings below. Then his glance fell on a scrap of chocolate - coloured quartz lying at his feet. He touched it with his lips, polished it on his rough sleeve until the sudden friction gave it a strange, prismatic brilliance.

"Phew!" he whistled. "It's fairly loaded. More like pure bullion than quartz. How much more is there?"

The buccaneer was about to light a cigar; he turned swiftly, and the match fell from his clay-covered hands. "I guess you haven't come here, Ned Jardine, to tell me that there's gold in stuff like that."

Without answering, Jardine took a hammer from a tool-chest and smashed the piece of brown quartz into fine dust. Scraping it into a dish, he washed it methodically until a glittering deposit of coarse gold seamed the edge of the dish.

"Only one metal in the world shines like that, Hayes," he said quietly. "Where's the rest? Where did you shovel it?" he asked eagerly.

Hayes remained staring into the dish at the shining grains of gold, and a sudden fury swept over him when he recalled the quartz-throwing incidents.

"Why ... we broke a hundred weight or more off the face of the reef," he said hoarsely. "Never thought the infernal stuff was worth handling. Yester day we amused ourselves throwing it at a cranky German and a black fellow."

Stepping from the mine, Hayes examined the ground where the German had stood the morning previously. Not a vestige of the chocolate-coloured quartz remained. Many tons of white stone lay around, flung from different pot-holes and shafts, but Hayes searched in vain for a scrap of his own alluvial.

"What made you get rid of it?" Jardine followed him somewhat incredulously. "It's the richest specimen stuff I ever handled — fit for the mint almost."

"Because it was beautiful stuff to hit a noisy German with: heavy as bullets.... Shoo!" The buccaneer returned to the mine and sat on an upturned bucket gloomily. "Something fishy about the whole performance," he muttered. "First a black fellow and a Chinese boy, then goats. Licks me, though," he added disjointedly, "where the stuffs got to. The niggers wouldn't pick it up. Now, who would take it?"

"You've been throwing away your gold, that's certain, Hayes. And somebody seems to have been watching for it," said Jardine reflectively. "It looks like a Chinese trick anyway. They tried it on me at Bendigo once, but I threw 'em some bullets instead."

Hayes clenched his fists, then laughed sombrely. "There's only one Chinaman in Queensland who could engineer a little scheme like that. He stole some pearls from my lugger last year while I was away hammering the police at Thursday Island. Guess I know the man by his style of thieving."

"You've thrown away your mine, Hayes. There's no more gold in that hole you're sinking." Jardine crossed the hush track slowly. "Never throw quartz from a mine until some of it's been through the battery."

After he had gone Hayes leaned over the shaft and addressed a few words to the men below; then, with a hasty glance around, he hurried towards the township at Emu Creek.

For one moment the listening head of a Chinaman appeared between two huge boulders and withdrew sharply. Ten seconds later the owner of the head was racing through the scrub with the speed of a camp horse. Long before Hayes had reached the creek bridge the head was nodding and the tongue wagging over the counter of Willy Ah King's buying room.

The big celestial gold-buyer looked annoyed; the scales clattered from his hands when the story of Jardine's visit to the mine was recounted. "The barbarian dog will come here. He will suspect me first." He turned from his counter and drove the horde of coolie clients into the street.

"No more business to-day," he snarled. "There is going to be murder. A mad dog is coming here to bite me. Begone!"

A dozen yellow hands locked the buying-room door. Willy Ah King ambled tiger-like to the rear of the house.

Hayes crossed the bridge hurriedly and skirted the edge of the gully, where seven hundred coolies were cradling and dollying stone. A score of eyes followed him as he swung past, heavy- browed, the devil in his eye. The house of Willy Ah King was reached by a side lane. A pair of iron plates had been fastened across the windows and door; the whole street appeared to have been suddenly deserted, save for the screechings of a sulphur- crested parrot chained to a verandah post.

Walking alongside the fence that skirted the rear of the house, the buccaneer vaulted over nimbly and found himself in a pig-infested compound. A half-bred dingo snarled at him from the back verandah; over the door hung a scarlet mask with pointed ears and goblin eyes. . .. The sound of hammering reached him, followed by the squeaking of a Chinese fiddle.

The heads of half a dozen coolies appeared at the upper window and stared sullenly at the white intruder; they withdrew reluctantly, and the sounds of hammering began again. Willy Ah King emerged from a near passage, slow-footed, uncertain of his man, fumbling at a brass-hilted knife half-hidden in his capacious sleeve.

"Why you blake into my house, Haye?" he began darkly. "Why fo'?"

"Those goats," said the buccaneer softly, "and about a hundredweight of brown quartz. I'm waiting, King."

"Goats?" Hayes could only admire the artistic elevation of the celestial's eye brows. "Why, you talkee bunkum, Haye. I no savee goats."

"And that German you trained to yelp his 'Wacht am Rhein' at my French workman. Own up you paid him to come round."

"Watchee Rhinee! I no savee. You go away, likee goo' fellah."

The door was about to slam, but the toe of the buccaneer's foot stopped it. In a flash he was in the passage on the heels of the gaping Chinaman. For a fraction of time the two men faced each other in the dark, the one panting like a trapped wolf, the other serenely alert, as one caressing each moment of his life.

"That bit of steel you're wearing in your sleeve, King, . . . don't."

A scuffling of feet overhead followed the buccaneer's swift entry. There were sudden tappings and signals from the hutch-like interior. Naked Chinamen scrambled up narrow flights of stairs, big- hipped men with a crazy fear in their blood — a fear that sometimes whipped them to the fighting point.

No white man south of Torres had ever ventured under the scarlet mask that hung over the big Chinaman's private door. But Hayes had been skilfully tricked, and his vanity cried out. "I'm going to be rude, King," he whispered. "I'm going to do the bareserk act in your gold-room. I'll strip you of everything bar the lamp-fittings."

"You!" The big celestial quivered from heel to throat. "If I put up my finger, Haye—"

"I'll shoot it away, and there'll be one less to thieve with. Up with your finger, Ah King."

The Chinaman breathed heavily, like one in doubt, his sleek hands fumbling in the dark. "You annoy me at the wrong time, Haye," he said thickly. "Yesterday my poor father die. ... I bury him to-day. My house is shut up, you see."

"Oh!" Hayes pondered briefly; the sounds of hammering above ceased. Some one with a broom was heard sweeping the floor carefully. "I never saw your father, King. Dead, you say?—well, you have my sympathy, anyway."

"You come upstair." The big Mongolian led the way up a steep flight of steps that opened upon a low-roofed apartment furnished with sleeping mats and a score of bunks. Naked Chinamen sprawled like leopards in the dark recesses. The thick slavering of an opium pipe broke the silence.

Standing on a table in the centre of the room was a large, coffin-shaped box; wild flowers had been thrown over it. A smell of burning roots and oil smoke filled the close air; busy hands fed a small fire with strange-smelling herbs and scented wood.

"My father died last night, Haye. He welly good man. He come from China to live here. Him catchee dengue fever and shiver himself to death."

"When you die, Ah King, there won't be time to shiver. Something cold and small will hit you where your food goes down."

"You takee some coffee with me, Haye," purred the big Chinaman. "Plenty cigars up here. You smokee li'lle while. Your mind foments; it no sleepee."

Several swart shapes crept in from the outer passages and watched the white man standing at the stairhead. They made no more sound than panthers as they floated in a half-circle about the coffin. The sunlight slanting under the bamboo eaves played on their naked torsos. From chin to loin-cloth they bore the savage scars of a dozen river fights: the flesh lay white where the old kris stabs had healed. And they stared long and silently at William H. Hayes, until their master spoke again.

"You takee coffee, captain. You feel much better byemby."

"I've known men who never felt any thing between the coffee and eternity when they drank it in your house, Ah King. I'm blind maybe on my business side, but I've a dog's instinct for smelling out a poisoned drink."

The buccaneer's words fell like shot upon the listening coolies. Their sullen immobility, their fixed crouching attitudes gave them the appearance of metal figures in some Chinese work of art. Not a finger stirred.

"You invited me here," went on Hayes, "to see your dead father. I'm sorry the lid is screwed down, but I feel confident that your lamented parent is snug and comfortable. The next thing, I suppose, is to bury him."

"You came heah to find your stone, Haye," nodded the big Chinaman evasively.

"That's because I was over-hasty, Ah King. The death of your esteemed parent has softened my views. Sorrow has fallen upon me like a cheap mantle from a bargain sale. Let me think."

"Goo' day, Haye, goo' day," murmured the Chinaman, advancing towards the stair head. "You come again any time you likee. Me too honest to stealee your gold."

"But the funeral," rasped the buccaneer, nodding towards the big coffin. "I've been invited. Don't disappoint me; I'm a terror for funerals."

"Hi, yah! You makee me mad!" stormed the overwrought celestial. "I have no patience. I chance one big fight, if you no go quick." His fat jewelled fist trembled in the air; his great sides heaved with rage and bewilderment.

"The funeral," insisted Hayes. "Speak one word to that yellow pack about fight and I'll pile the six of them alongside your father."

The coolies standing at the coffin measured him foot and hand, judging to an inch the space that separated them from his erect form. And in the fall of an eye they knew that the two navy revolvers bulging from his pockets would cut them down ere they could pin him heel and throat. They had fought unarmed ships, plundered white missionaries in their own land.... But this baying intruder was not a missionary, and they liked not his tricks of foot and hand.

"The funeral," he repeated softly. "You'll carry that coffin from here to your own cemetery. And you'll do it decorously and humbly, for the dead man's sake. I am ready."

Without a glance at their palpitating master the six coolies obeyed the voice. The coffin was lifted from the table and borne down the stairs into the compound. With his hand on the big Chinaman's sleeve, Hayes drew him into the street.

The Chinese cemetery lay on the slope of a pine-covered hill about a mile from the township. Scores of Mongolian diggers threw down their tools and joined the strange funeral procession. Wind lasses were deserted, and from gully and creek bend poured an army of inquisitive coolies, eager to discover why the big barbarian Hayes was walking behind their dead.

The buccaneer paid no heed to the yellow swarm pressing on his rear. Many were armed with kris-shaped knives, others carried pick handles, while a few aboriginal spears and wommeras showed among their ranks. A rumour that the white barbarian intended to mock their celestial Obsequies passed among them.

The bearers trudged over the quartz- strewn flat until their white stone joss house was visible through the dark cypress pines. At Chinkies Hill they halted, glancing swiftly at their master.

Hayes ran his eye over the mounds of earth and stone that marked the resting- places of many high-caste Manchu and coolie adventurers. . . .

One fact impressed itself as he searched the endless cairns and spaces — no grave had been prepared.

"What mockery is this?" he demanded suddenly.

A mutter of astonishment flashed through the lines. Scores of inquisitive Chinamen sought for the open plot of ground that should have been prepared for the sacred relics of their dead country man.

Willy Ah King addressed the crowd in the vernacular. He said that the white man had forced the funeral before his preparations were complete. Picks and spades were produced, a trench was dug in the shade of the cypress pines, and Hayes noted that the ground chosen was just outside the area allotted for Chinese burial purposes.

A quantity of fireworks and some roast pig were handed around. At a sign from a Buddhist priest the coffin was lowered into the trench. Half a dozen spades filled in the earth amid a sharp enfilade of snake-like crackers.

The big Chinaman remained by the filled-in trench as though lost in meditation He was aroused suddenly by the sharp hammering near his foot. Glancing down he saw that Hayes had driven a miner's peg at each corner of the grave.

The buccaneer's action was apparent even to the ignorant swarm of coolies watching his movements. The driving-in of the pegs had, according to Queensland law, converted the grave into a mining area.

"See what the white dog has done!" Willy Ah King stood trembling before his astonished countrymen. "Our graves are not sacred. The bones of our ancestors defiled. Kill him!"

A knife slipped from his broad sleeve and took refuge in his fist. For his weight and height the Chinaman was nimble-footed as a wolf; twice he feinted with the dexterity of a Malay and drove his long blade full at the white man's throat.

Hayes slanted forward, caught the stabbing wrist in mid-air and held it until it cracked. Pushing his knee against the breathing hulk he forced it to the ground.

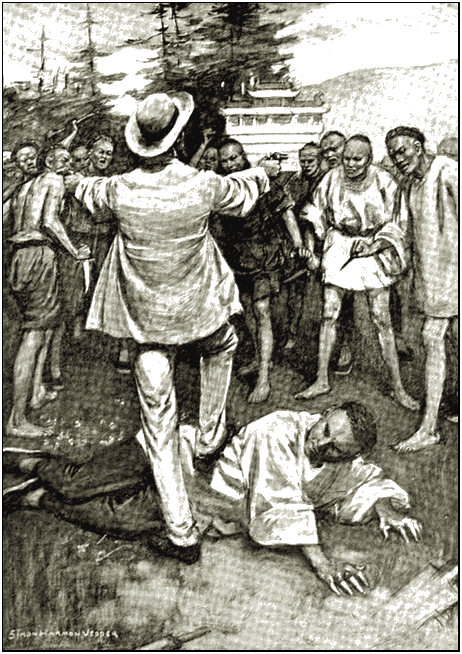

"Now." He faced the bristling horde of coolies, and his heavy revolvers leaped wickedly into line. "I don't want to molest the bones cf your ancestors, my children. I want to show you that this overfed rascal is a stupid impostor. His father was not buried here to-day, you savee — him not in the box." He pointed to the filled-in grave.

He faced the bristling horde of coolies, and

his heavy revolvers leaped wickedly into line.

"One big lie! One fool lie!" screamed the Chinaman. "You no touchee my father underground. You no touchee!"

Driving a spade into the soft earth, the buccaneer flung out piles of loose sand stone until it stood in a heap beside the grave. A sudden stir on the outskirts of the crowd made him look up sharply. The gold warden, accompanied by two mounted police, rode through the panting lines of naked coolies. Halting in front of Hayes, the warden, a grizzled army veteran, smiled ominously.

"Captain Hayes," he said sharply, "who gave you permission to interfere with the grave of an inoffensive Chinaman?"

"Grave!" The buccaneer continued throwing out earth with the speed of three navvies. "Who said it was a grave? It's a claim, with my pegs at each corner. Here's my licence." He waved his certificate at the suffocating officer.

"Stand out of that grave!" commanded the warden. "There are hundreds of witnesses to prove that a man has been interred here to-day."

"I guess if you'll tell me that man's name I'll go quietly to gaol. Come now," continued the buccaneer, resting on his spade, "you are warden and police magistrate here. If a man was buried you were surely notified. Where's the medical certificate?"

The warden grew calm and reflective. "No death has been recorded," he admitted slowly. Then to Willy Ah King, "Why did you not notify me concerning this affair?" he demanded.

"I no savee your law," responded the Chinaman evasively. "This fellow Haye, he bully me allee day."

"Did he bully you into making your father die?"

The big Chinaman was silent.

Hayes drove his spade under the box and raised the head from the loose earth. A couple of white miners sprang into the trench as though to render assistance. The buccaneer ejected them with a suddenness that sent them back white- lipped and apologetic.

"I don't want a pair of smarties putting in a claim for shares," he explained to the warden. "Please stand aside. I'm playing at miners' right."

At that moment his mate, Bill Howe, pushed through the crowd, followed by the Frenchman and a couple of kanakas.

The box was raised from the trench; a blow from a spade opened the lid, revealing a hundredweight or more of tightly packed chocolate-coloured stone. Hayes nodded to the warden. "Gold quartz from my claim at the White Marble."

"Stolen, eh?"

"There are degrees of theft," laughed the buccaneer. "Guess I won't press the charge anyway."

It was clear now that Willy Ah King had been caught unawares. Having gained possession of the rich stone, he had waited a favourable opportunity to send it to the crushing mill on the flat.

The buccaneer's swift entry into his house had driven the crowd of celestial gold-buyers to their wits' end, for they believed that the big-voiced barbarian was accompanied by a gang of white miners ready to search the place. In his panic Willy Ah King had secreted the rich stone in a coffin— there is always one on hand in every Chinese establishment — believing that the white men would not dare to investigate too closely.

The forced funeral, and the swift exhumation that followed, had paralysed the gang of Chinese gold-thieves.

The coolie mob scattered suddenly, and ran like an unleashed pack across the hillside. Turning, the warden and troopers saw Willy Ah King racing towards the distant township. A strange sound, like the yelping of dogs, filled the air — Hayes had heard it before in Tonquin when the yellow rioters flung themselves upon the French bayonets. Over the sandhills streamed the furious mob, straining, foot and heart, to overtake the man whose greed had defiled their hallowed ground. The last coolie vanished in a cloud of flying stones and dust.

Nodding to Hayes, Bill Howe, assisted by the kanakas, raised the big box of quartz to their shoulders and moved slowly down the hillside.

"When I threw my gold mine at those blamed goats it was anybody's property who cared to pick it up. No need for the chow to have invented his dead father," said Hayes to the silent warden. "There wasn't enough emotion about that funeral to convince a black fellow."

"Resembled a procession of burglars," responded the warden wearily.

"It was," admitted the buccaneer as he followed the coffin- bearers over the hill.