RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

The Pall Mall Magazine, September 1908, with "The Opium Dealers"

"BULLY" HAYES was a notorious American-born "blackbirder" who flourished in the 1860 and 1870s, and was murdered in 1877. He arrived in Australia in 1857 as a ships' captain, where he began a career as a fraudster and opportunist. Bankrupted in Western Australia after a "long firm" fraud, he joined the gold rush to Otago, New Zealand. He seems to have married around four times without the formality of a divorce from any of his wives.

He was soon back in another ship, whose co-owner mysteriously vanished at sea, leaving Hayes sole owner; and he joined the "blackbirding" trade, where Pacific islanders were coerced, or bribed, and then shipped to the Queensland canefields as indentured labourers. After a number of wild escapades, and several arrests and imprisonments, he was shot and killed by ship's cook, Peter Radek.

So notorious was "Bully" Hayes, and so apt his nickname, (he was a big, violent, overbearing and brutal man) that Radek was not charged; he was indeed hailed a hero.

Dorrington wrote a number of amusing and entirely fictitious short stories about Hayes. Australian author Louis Becke, who sailed with Hayes, also wrote about him.

—Terry Walker

Dear Hayes,

The Chinaman Kum Sin is due at Emu Creek early this month. He chartered a bull-headed junk from a firm of schooner-breakers in Sourabaya. His manifest shows some silk trade and fancy notions for the islands. Some where between the garboard strake and the bulkhead partition are fifty or sixty packets of Indian opium—Government stuff—not mentioned in his bill of lading. I don't think you've got a chance with Kum Sin unless you place him between two cooking fires and pile on the wood —and that isn't your way of dealing with the silent, opium-smuggling chow. Times are hard, Hayes; pearl is selling at three hundred dollars a ton. Kum Sin's little cache of opium would be worth five thousand. Try for it, and don't forget that I expect a commission.

Barney McKee.

Thursday Island.

HAYES handed the letter to his first mate, Bill Howe, and

sighed wearily. "McKee's right," he said, when the mate had

finished reading it by the binnacle light. "I wouldn't put a chow

between two cooking fires. Not me! "

"You ain't that kind of man," agreed the mate, handing back the letter. "You had a chance last year, in Samoa, to burn down Willy Ah King's place, and you didn't."

"There's no sense in lighting up a Chinaman's store these times," grumbled the buccaneer. "It leads to all sorts of unpleasantness."

"But you threw a blazing tar-barrel into Sam Lee's trade house at Nukahiva, cap'n," declared the mate, with a sudden change of manner. "It was a terrible burst up! You never suspected that he had dynamite stored inside. The explosion turned the Consul's hair green, and we had to put to sea without stores."

"We all make mistakes," admitted the buccaneer sadly. "It happened in my salad days, when the sight of a Chinaman tearing across a burning roof with his cash-box under his arm appealed to me."

Hayes paced the narrow deck in silence, his eyes wandering over the distant sand-hills, where the lazy town sprawled from the pier to the edge of the mangrove-skirted creek. "I'm going to be a better man in future, Bill," he added sombrely. "No more Chinese bonfires, no more vermilion nights. I'm going to try modesty and forbearance. There's no sense in yelping round the world persuading mule-headed consuls I am honest. No one ever believed me. And if I forget to hold up a cargo tramp occasionally, or bully some poor old French gunboat, people say I'm losing my nerve."

"They do, cap'n," nodded the mate.

"It's a blamed lot harder to be a coward in these parts than it is to steal a nine-inch gun from the deck of a British cruiser. I'm sick of being brave; one of these days I'll run away from some blatherskiting, ten-stone German, just to show that I don't value public opinion."

"They'd say you were luring him into a quiet place to raise a hundred dollars from him," added the mate slowly —"that's what they'd say."

"Of course they would," grunted Hayes. "It's a terrible thing to live down your reputation. And assuming," he went on, "that the ten-stone German didn't put up the hundred dollars, it would be hard to persuade him that it wasn't me who had bumped his forehead on the foot-walk and flattened the kerb with his face."

"He'd never believe you, cap'n," said the mate earnestly, "nor anybody else."

Hayes brightened suddenly. "Makes me feel good to think that I've bumped a few nasty heads in my day. Still, I intend living a reasonable life in future. I'll leave Chinamen alone. I'll keep to my own schooner and give shore-life a rest."

THREE days after the above conversation a big, squat vessel,

half junk- and schooner-rigged, hove, like an unclean bird,

across the mouth of the inlet. She was manned by Tonquinese and

Malays, lazy-eyed rascals, more accustomed to the ways of a

swift-sailing prau than the slow, wind-shuffling junk-

schooner.

Captain Hayes, loafing on the beach at Emu Creek, observed her closely, and after a brief survey of her villainous crew decided to wait until she was berthed alongside the pier before paying his respects to her captain.

Night comes swiftly along the jungled seaboard of North Queensland. Darkness fell before the vigilant pearling luggers and trepang dredgers could hang out their riding-lights. The pier was almost deserted, save for the solitary customs official wandering occasionally up and down.

It was nearly midnight before Hayes ventured on the pier. Halting at the foot of the junk's rickety gangway, he whistled a peculiar melody familiar to every pearl-thief and opium-smuggler west of Torres.

There was no reply from the junk's interior; her ancient timbers creaked and whined as the tide lifted and bruised her sea-worn shoulders against the piles.

"Ahoy there! Anybody aboard?" The buccaneer paused, his foot on the greasy gangway, and listened: a prolonged snore came from the depths of the fo'cs'le, followed by a slavering sound, as though a thick fluid were being drawn through the stem of a pipe. An oil lamp flickered dully under the bamboo stays, where cases of fruit and smoked trepang lay piled in great disorder. An odour of sun-dried dugong lingered in the air.

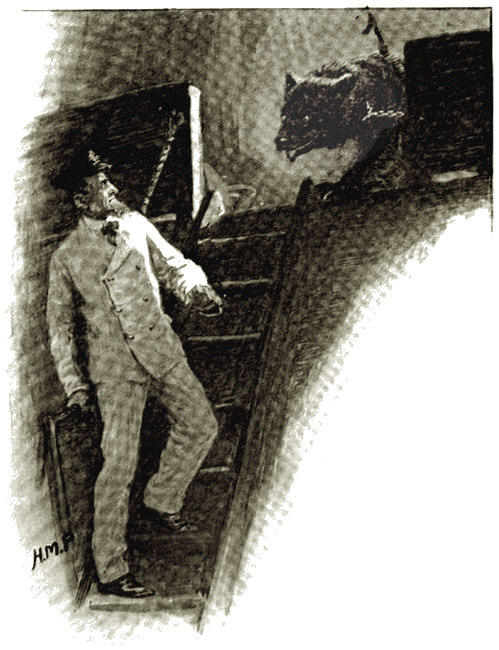

Peering for'ard, Hayes was conscious of two moon-coloured eyes watching him from the heaped-up garbage. The clink of a chain broke the silence; a muffled snarl seemed to run along the deck, while the chain thrashed violently against a restraining cleat.

The buccaneer retreated nimbly down the gangway, paused a moment as the head of a black bear lolled over the junk's side, watching him intently. "Phew!" Stooping suddenly, he picked up a piece of ballast stone lying on the pier, and hurled it at the moon-coloured eyes.

The buccaneer retreated nimbly down the gangway.

The chain rattled loudly, but the black head vanished with magic brevity. In its place appeared the swart Mongolian captain, naked to his loin-cloth. He regarded the buccaneer with a drowsy, inquisitive eye. "Wha' fo you tlow blicks at my bear?" he demanded icily.

"To hit him," breathed Hayes. "He nearly bit me."

"You go 'way un' leave um bear alone! " The wrathful voice of the Chinese captain fell shrilly upon the hot silence. "Him no bitee if you takee your legs off my ship. Go 'way."

"If you say anything about my legs and where they ought to be," thundered Hayes, "I'll turn your blamed junk into a scrap heap."

The pigtailed head vanished swiftly down the fo'c's'le stairs; the chain clinked and rattled as though the bear was trying to follow the Chinese captain below.

HAYES returned to the town and entered a dingy, half-lit

shanty kept by a German whisky-seller named Schultz. A crowd of

divers and shell-openers were playing dice over the counter.

Everybody gaped at sight of the buccaneer standing in the doorway. Schultz wiped the counter and put away the glasses with sudden energy.

"Boys," Hayes smiled genially, "don't mind me. I'm not drinking."

"There's some champagne at five dollars a bottle, cap'n. We'll be glad if you'll join us," said one earnestly.

"No, boys, not to-night. I'm turning over a new leaf. Drinking leads to a sore head and only spoils your nerve. I want to make the town laugh to-night, boys. I want to make it feel innocent and young; I want it to put aside its unholy thirst and play with a bear."

"Oh, say, bully, you've been lyin' in the wet. You've seen things walking up your coat. Try some whisky; it'll wear off."

"My bear won't, boys. It's got a chain, and it's fastened to the big iron cleat on Kum Sin's junk." Hayes regarded the crowd sorrowfully. "I didn't think you boys would let a Chinese circus come into port without providing it with some music."

The pearl shellers and bÍche-de-mer fishers who ply their calling on the northern limits of Australia are laughterless and sullen by nature. The business of scouring the sea-floor in quest of shell among the giant reef-eels and carpet- sharks of Torres Straits is not conducive to high spirits and the making of jests. But at that moment each man felt called upon to display a certain interest in the bear chained on board Kum Sin's evil-smelling vessel.

"Ef we could get it into the bar," ventured one, "we could give it beer until it made the right kind of noise."

"You vill nod pring a pear indo my bar," protested the German proprietor. "Id vas nod a licensed menagerie."

"Oh, we don't want to poison the creature, Dutchy," broke in another. "He ain't done us no harm."

"Tell you what, boys," Hayes wiped his brow thoughtfully. "First we'll get the bear, then we'll walk it round to Hung Chat's gambling den and lower it through the roof onto the big table where the money is piled. And the man who follows the bear will be able to wash his hands in English gold and American dollars.

In ten seconds the bar was deserted. Outside the crowd collected in a silent group and proceeded towards the pier.

"Say, Hayes!" cried some one, "what variety of bear is it? Not one of them Yankee buffalo eaters, eh?"

"No," drawled the buccaneer; "it smelt like the black Indian species, the sort that roots out honeycomb and oversets jam pots. Now, if we had a beehive, boys, we could drop it into Kum Sin's fo'c'sle. You can't beat a swarm of black Italian bees for cleaning out a crowd of dirty chinkies and Malays."

THE pier was almost in darkness when they advanced stealthily

upon the slow-heaving junk. The customs officer emerged from the

shed inquisitively. "Now, you fellows," he said huskily, "don't

get fooling with that Chinese schooner. It gives the port a bad

name. I saw Hayes up there not long ago," he added, "and whenever

he's ashore we always want a few extra police in the town."

No one thought fit to answer, for at that moment the bear's outline was visible walking down the junk's gangway, followed by Captain Kum Sin holding the long chain.

"Steady, lads," whispered a voice; "no hustling, or the animal might get one of us." A long trawling-net, belonging to some fishermen, hung on the pier rail. In a flash it was secured, and whipped around and over the bear the moment its feet touched the pier. With a scream of dismay the Chinese captain scrambled back to the fo'c's'le and vanished below.

The bear writhed and struggled in the double folds of the net as they bore it hurriedly down the pier. The customs officer regarded them indignantly. "I warn you," he began angrily, "that you have no right to forcibly remove anything from this pier." His lantern flashed on the black object struggling within the net. "Yah!" he withdrew in disgust to the shed. "Can't you enjoy life without stealing bears?" he cried angrily. "A hot night like this, too."

The crowd rushed past, yelling insanely, while they dragged their unwieldy burden towards the town.

"Where's Hayes?" ventured the leader of the party. "Haven't seen him since we left the pub."

"Must be hiding," gasped the man who held most of the bear in his arms. "Funny he isn't here."

The buccaneer waited in the shadow of the customs shed until the bear had been safely trapped; he watched them cross the sand ridge leading to Schultz's whisky bar before venturing across the pier.

Then, with an utter disregard for Malay kris or Chinaman's pistol, he clambered aboard the junk and dived into the fo'c's'le.

In his day Hayes had inhaled the black odours of many Sydney and Calcutta crimp houses; he had loitered within the plague- darkened byways of Madras and Bombay; but nothing that defiles the air or sea could equal the rancid warmth that floated up from the junk's fo'c's'le. A tawny light enveloped the hutch-like enclosure. Spluttering oil lamps burned at each bunk-head, and from the reeking interior of each coffin-like aperture peeped a bald pigtailed head. Occasionally a pair of "cooking" needles flashed out, turning and rolling the tiny black pellets over the sizzling lamp-flame. In the topmost bunk squatted Kum Sin, glassy eyed, owlishly despondent. Something had happened....

His eyes slanted towards the intruder, and his yellow skin grew luminous as polished metal in the hot lamp flare.

"Why you come here?" he asked thickly.

"Because I'm a commission of inquiry," said the buccaneer from the stairs. The game is up, Kum Sin."

The captain of the junk blinked; an old bullet scar on his right cheek seemed to grow livid in the yellow, lamp-poisoned atmosphere. "You steal um bear. You know ebblyting. Why fo' you worry me?" he asked.

The buccaneer crushed forward half a pace, like one exploring an inferno. "That opium cache, Kum Sin. You know it's contraband hereabouts. Where is it? Tell... don't blamed well gibber like a pantomime frog."

The painful silence that followed was not to the white man's liking. He almost feared the voiceless Mongolians sprawling inside the narrow bunks. They moved or turned sullenly as beetles... there was always a clenched hand pressing over the eyes as though to soothe the throbbing numbness of the brain. A pair of long needles clicked over a blue lamp-flame as they roasted and twined a stringy opium pellet. One narrow-skulled Tonquinese, lying on his side, yawned as though the devil of ennui were strangling him. Captain Kum Sin yawned in sympathy; a film came over his eyes.

"Seems to me that you people aren't listening," rasped Hayes. "My voice hasn't brightened the ship worth a cent, and I'll swear there's music in it."

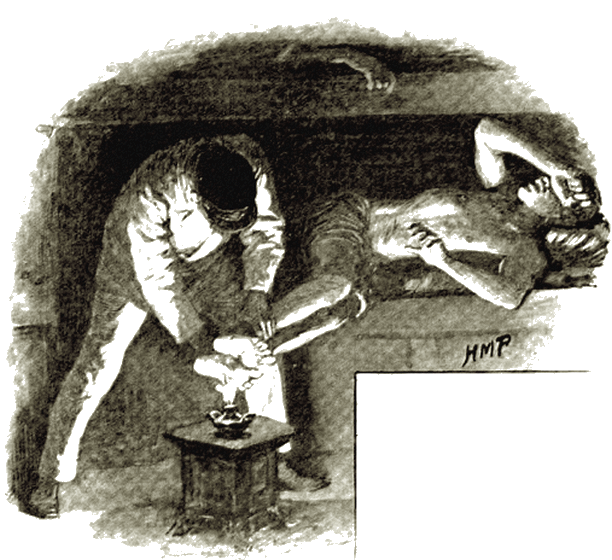

Seizing Kum Sin's ankles, he hauled his legs from the bunk, and gently, very gently, held his naked soles over the lamp- flame. For three seconds Kum Sin appeared unconscious of what was happening; then his face creased and his eyes bulged. He struggled fiercely, but the iron fingers gripped his ankles until the flame spluttered and grew dark. A drop of sweat fell from the Chinaman's brow.

He held his naked soles over the lamp-flame

"Hi, yah! " he stammered hoarsely. "You lettee go. I speakee."

"The buccaneer tossed the heels into the bunk; the flame of the oil lamp grew brighter and burned steadily. Hayes regarded him, from the centre of the fo'c's'le, hand on hip.

"Realising that I'm a man of affairs, and that the lamp warms the heart as well as opium, you will kindly oblige with a speech, Kum Sin. I'm waiting," he added sombrely.

"If I takee one big pill now I feel um no lamp-fire," snarled the tortured Chinaman. "What you do then?"

"Guess I'll put a flame through you that will singe the whiskers off your soul."

Kum Sin rubbed his instep thoughtfully with drug-blackened fingers. "Opium all gone," he said after a while. "Bear cally it away. No use touchee me any more. You catchee bear."

The beaten tracks of language appeared palely inefficient when called upon to carry the buccaneer through the first outbreak of surprise and indignation. Then he grew calm and his mind nimble, when he remembered the great white blank that sometimes sweeps over the minds of Chinamen. "What's the bear got to do with the opium?" he asked. "It couldn't take the stuff ashore."

The yellow figures, crouching within the bunks, smiled wearily at the perturbed white man. Kum Sin's mouth twitched.

"Him only half a bear. One part skin, one part Chinaman."

"Oh!" Hayes appeared lost in thought for several moments.

"Half Chinaman, half bear, eh? Kind of missing link." His face lit up sud denly. "P'raps you'll tell me which part belongs to the bear and which to the Chinaman."

"All bear outside," grinned the junk captain. "One li'lle Chinaman named Bing Boh inside. Bing makee welly good bear. He learn tlicks in Amelican show one time ago."

"If you are going to load me with a lot of bear lies, Kum Sin, I shall have to fill the air with a smell of burnt instep. I can forgive anything but bear lies," added Hayes bitterly.

"Me speakee tluth," gurgled the China man. "Me hard-pushed to get opium ashore. Custom man sleepee on the pier and watchum junk allee day, allee ni'. Me lead um bear down pier by one big chain. Custom man go sleepee. All li, welly smooth. Nobody about. If pleeceman come me show him bear in the dark. Him no come too close—no feah."

Hayes broke into laughter, kicked a half-recumbent Malay into the bunk, and hurried upstairs. At the pier-head he met Ebenezer Wick, customs officer and Government representative.

"Hello." Hayes led him into the shed sorrowfully. "About that bear."

Mr. Wick felt his hair a trifle abstractedly and re-lit his smouldering pier lantern. "The poor creature's been ill-used, I reckon. And the sooner that crowd of yours understand it the better. There's a resident magistrate in this town, Captain Hayes," he said significantly.

Mr. Wick's fondness for animals was well known throughout the Gulf, and he had often allowed sailors and schooner captains to bring dogs and pets ashore, in defiance of the Queensland harbour regulations. There were times, however, when his good nature was imposed upon.

"I'm in sympathy with the bear, too, Ebo," admitted the buccaneer hastily. "1 was once a member of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Bears. Yes, I'm angry, too, Ebo," he insisted, "and sober."

"Well, the bear ain't hurt no one," continued Mr. Wick sternly. "Most peaceful animal you ever set eyes on. About sundown, Captain Kum Sin asked if I objected to him exercising his bear up and down the pier and beach."

"You didn't mind, Ebo?" broke in the buccaneer.

"Why should I? Poor, harmless thing, chained up in that smelly fo'c's'le head since they left Sourabaya. I don't say I'm gone on bears, but there's no extra charge in this port for a little kindness and humanity."

"And Kum Sin, being fond of bears, promenaded it pretty often —eh, Ebo?"

"Yes," drawled the customs officer, "pretty often: a dozen times, I should say. I was having a nap in here, and every time I woke I could see the China man exercising his animal. It did seem a bit funny at first," continued Mr. Wick, "but any man who has been on shipboard with animals knows how they pine to stretch themselves. A man doesn't want an extra big brain to understand the poor brutes."

"Every time you woke you saw the Chinaman and bear strolling past," mused Hayes. "Well, I'm—" Without a glance at the customs officer he dashed from the shed towards the township.

INSIDE Schultz's bar he found himself peering over the heads

of the crowd at the naked head and shoulders of a Chinaman

protruding from the skin of a black bear.

The bewildered celestial was endeavouring to explain the situation in pidgin English, when Hayes plunged his hand into the capacious interior of the skin and drew out a thick cake of opium wrapped in sun-dried banyan leaves.

A dozen inquisitive hands hauled the Chinaman from the loose- fitting bear's hide. The inside was rifled and searched until seven more cakes were discovered within the huge pockets that lined the interior. The buccaneer made swift calculations.

"Eight two-pound cakes a trip—twelve trips per evening —make one hundred and ninety-two pounds. Opium, the pure stuff, is worth forty dollars a pound here abouts. Total, seven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars. Not bad for one night's work."

The trapped Chinaman gesticulated hysterically. "You no lockee me up. My master, Hung Chat, send me aboard um junk to cally away opium. He buy um bear-skin long time now; he makee me plactise inside bear-skin until I run about plitty smart. Welly goo' to bling opium ashore, he says. You talkee to Hung Chat."

"He's only the tool of the big hasheesh syndicate at the gambling-house," Hayes indicated the chattering celestial contemptuously. "Every time he walked ashore as a bear he made six hundred and forty dollars for his bosses."

The Chinaman was hurried into a back room: Schultz locked the door and barred the window securely to prevent his escape.

"Now, boys," the buccaneer addressed the crowd briskly, "I never pretend to beat a chow at this contraband game, but if one of you will walk round to Hung Chat's gaming house and tell him we've captured his hear we might persuade him to buy it back."

"I'll go, cap'n! " cried a thick-set diver, with rubber-chafed wrists and swollen hands. "I'll ask two hundred dollars for the bear."

"Two thousand," corrected Hayes. "Money down or no bear. Tell him if he doesn't hurry up we'll send the Government officer round with the bear and contraband in custody."

The diver departed hastily, while the buccaneer outlined a scheme whereby the local hospital would benefit to the extent of two thousand dollars after the gang of Mongolian smugglers had been forced to disburse.

HALF an hour later the diver returned hatless and triumphant.

He had been received by Hung Chat in person, he said. There had

been a furious scene, but the Chinaman promised to pay the two

thousand dollars providing all evidence of his guilt—the

contraband and bear-skin—were delivered to him within an

hour.

Hayes listened, and pondered for the space of thirty seconds. "We must return him his bear, boys," he said after awhile, "but no contraband. Now who's going to be the bear?" he added, glancing round at the eager crowd. "Don't all speak at once. It isn't often you get a chance to play your proper parts in life. Who'll climb into the hide and go with me?"

"I'm as much a bear as any man here." Bill Howe edged forward. "Mind, it's for the 'orspital," he growled warningly. "No larks, cap'n."

Hayes gathered up the warm bear-hide, and regarded the mate pensively. "Bit of a struggle to get your feet in, Bill," he said dubiously. "A man like you takes a special size in bear-skins. Wish Hung Chat had gone in for a hippopotamus hide; it would have fitted you like a glove."

The mate struggled into the hot, hairy covering, while the yelping divers buttoned and laced it about his head and shoulders. Out in the road they stroked and offered liquid refreshments to the great four-footed shape that waddled and made strange noises whenever they became too familiar.

Hayes led the way. "Boys," he cried warningly, "don't follow! Keep your eyes on that opium pile inside the bar."

The bear followed him along the dark, hot road beside the sweltering mangroves, where the tide had piled the blue mud to the edge of the footwalk. "Bit warm inside, Bill?" Hayes spoke with his chin in the air. Not a breath stirred the oily waters of the bay.

"What you said about the hippopotamus hide wasn't over-civil," panted the bear, "before that crowd of beer-swilling shellers, too."

"I only meant that a nice steady job as a hippopotamus would suit you, Bill. You'd hardly expect me to say that you could crowd that bulk of yours into a rabbit-skin."

"I'm doing the 'orspital a turn," came from the hot interior of the bear-hide, "or I'd get out."

They passed on swiftly. One or two trepang fishers, loitering on the beach, stared incredulously at sight of the buccaneer tramping beside a shaggy, unwieldy animal that addressed him at intervals in muffled undertones.

THE house occupied by Hung Chat was a low-roofed affair,

surrounded by close-planted acacias and casuarinas. It was the

haunt of wealthy Chinese merchants, who came at all hours to

indulge in a yen-yen and cook a little opium over the

silver lamps in the silk-cushioned back rooms.

A small fat Chinese boy in an orange-coloured kimono opened the door. He smiled at the buccaneer, and led the way down a narrow, unlit passage that gave out mysterious odours of scented woods and perfumed oils. A room with a screened lamp and plush- covered divans stood at the end.

The buccaneer entered without sound, and nodded familiarly to an under-sized Chinaman squatting on a pile of cushions. "Good- night, Hung Chat; nice mess you've made of it rushing your unholy contraband past Her Majesty's officials," he began. "You put a lot of simple faith in a blamed old hearthrug blown up to look like a bear."

Hung Chat sat back and blinked. A touch of fear crossed his eyes. "Bad job, you think, Hayes? I hope you are my friend," he said, after a pause.

"Of course I'm your friend. I wouldn't let any one touch you with a gallon of rosewater. Still, I'm afraid you've overdone it this time, Chat."

The Chinaman picked at his nails thoughtfully. His face seemed to grow old and withered; it was as though the shadow of a gaol had crossed his vision. And Hung Chat, with his silken ways and delicate palate, was in no condition to face the horrors of a North Queensland prison. His manicured fingers trembled slightly; he turned his withered, opium-ravaged face to the buccaneer. "What you think I better do, Hayes? What you advise, eh?"

"Buy the bear—it's in the passage. Two thousand dollars will clear your character."

"Two thousand!" There were screams unuttered in the Chinaman's dozing eyes. The skin of his face seemed to warp like hammered brass. "By cli, you cuttee my throat, Hayes! You squeezee me to the heart."

The buccaneer leaned across the divan and spoke to the perfumed, slant-eyed face. "There's a gaol at Shark Island, where the white warders sit on the wall with guns. There are sixteen cells—ten of them are filled with kanakas and black Arunti tribesmen: you know what they are. And don't forget the hominy, and the breakwater you'd help to build with your soft hands, and the long-bodied water-rats that would prowl over you at night. How do you like it, you brain-destroying parasite?"

Hung Chat crawled from the divan, and turned to an iron safe in a corner of the room; the keys rattled in his hands as he opened the door. Here and there one saw piles of opium cakes bulging from the shadows, hinting at the nefarious trade in which he was engaged.

A cash-box was jerked to the table in front of Hayes. Hung Chat opened it feverishly, took out a roll of bank-notes, and spilled a parcel of sovereigns into a leather bag at his side.

The sudden clinking of a stirrup-iron, the unmistakable sound of a horse champing its bit outside reached them. The Chinaman stood rooted; then his lean hand swept over the cash-box convulsively. "Wha's that?" he stammered.

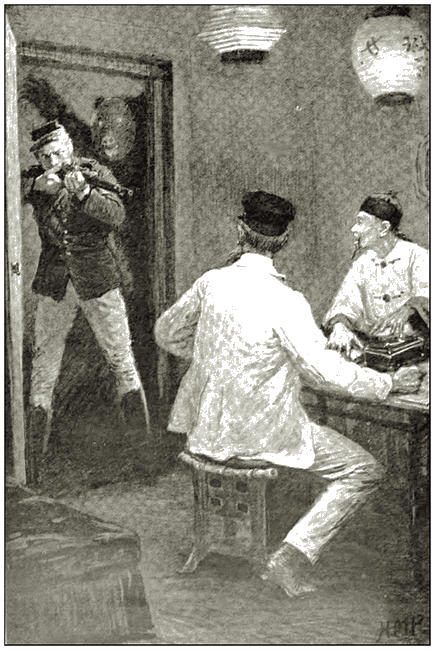

Three sing-song words happened in the vernacular from an outside room. The buccaneer found himself staring into the barrel of a carbine.

"Don't move, Captain Hayes. And you, Hung Chat, keep your hands down—in the Queen's name."

The peaked cap and uniform of a Queensland trooper showed in the darkness of the passage. His spurs jingled as he stole half a pace nearer; but not for a moment did the short, wicked barrel move from its position.

"I'm sorry you're mixed up in this affair, Captain Hayes." The young trooper spoke quietly, like one certain of his men. "This opium traffic is going to be put down."

The buccaneer swore under his breath. The carbine would cover him until the handcuffs were snapped over his wrists —and then... nothing would save him from penal servitude within some filthy, fever-ridden gaol....

"I'm sorry too, Hennessy," he answered pensively. "Sorry that you are going to arrest me in company with this—beast." He indicated the chattering, fever-stricken opium-dealer.

A slight, imperceptihle movement happened within the dark passage —the Dantesque shadow of a bear fell across the wainscot: two huge paws enveloped the trooper, holding him until his joints cracked under their fierce pressure. Hayes snatched the carbine from the paralysed arms.

Two huge paws enveloped the trooper.

"Ef you're goin' to make trouble, Hennessy"—the bear stooped over the helpless trooper—" I'll hug the soul out o' ye. We're only playin', mind; it's all guff an' pantomime, so don't start squealin'."

"I'll arrest the three of you the first time I meet you outside," choked the young trooper. "I'll get you singly."

"Hennessy"—with deft hands the buccaneer extracted a pair of handcuffs from his pocket, saying gravely—"I must do you the honour first, while my hairy friend passes a cord round your ankles. So... that will do nicely."

Hung Chat remained half-hidden in the shadow of a beetle- covered screen. He made no gesture, uttered no sound until the handcuffs snapped over the young trooper's wrists. A long-drawn sigh escaped him; it was as though the shadow of Shark Island gaol had lifted.

"Don't—don't leave me here with that Chinaman, Hayes!" The trooper rolled helplessly on the thick-carpeted floor. "You remember what happened to Cardigan?"

THE buccaneer halted half-way down the passage. He had heard

only a few weeks before of a trooper being caught alone by a gang

of Chinese gamblers, while attempting to arrest one of their

number on a charge of murder. The yellow men had carried him into

the distant scrub, where a couple of stout pegs had been driven

into a nest of furious black ants. After stripping him they

fastened him, neck and heel, to the pegs, and quietly departed. A

few days later a party of miners came upon an ant-ravaged

skeleton whitening in the sun.

Hayes pondered a moment, while the bear growled something in his ear. Returning swiftly to the room, he unlocked the handcuffs and ankle-cords, and assisted the trooper to rise. No word was spoken.

The Chinaman watched the new turn of affairs with bulging eyes. Darting round the table he gesticulated fiercely to Hayes. "Why you let him go? Wha' fo', wha' fo'? Why you no hold him like this?" He drew his hands together as though strangling an unseen enemy.

Trooper Hennessy bent his head slightly. The buccaneer touched his shoulder. "I'm going. Here's your carbine, and the bear has asked me to offer his apologies."

Pausing a moment in the passage, Hayes looked back at the motionless trooper. "You know your business, Hennessy. There's your contraband"—pointing to the piled-up cakes of opium —"and there's your Chinaman. Don't say I tied you up and allowed a horde of silk-whiskered vampires to crucify you on an ant-heap. Good-night, Hennessy."

"Good-night, Captain Hayes."

Hurrying from the silent house, they half ran down the tree- skirted road leading to the pier. An unmistakable chinking sound accompanied the bear's movements. Hayes halted and glanced at the skin-covered head beside him. "What's that jingling inside you, Bill?" he demanded sternly. "Did you—?"

The mate plunged his hand into the capacious folds of the pocket-lined skin, and hauled out Hung Chat's bag of sovereigns. "The 'orspital money, cap'n. We promised to hand it over to the sick people in that fever-trap of a buildin' near the creek."

The buccaneer gazed longingly at his schooner's light, riding beyond the breakwater, and his thoughts went out to the white penitentiary at Shark Island. "Bit risky hanging about the town after what has happened, Bill," he said, half aloud. "The black police will be swarming in at daybreak. Don't you think we'd better—?"

"Keep our word to the 'orspital," grunted the bear. "Mostly sick women an' little black piccaninnies, cap'n."

Hayes frowned. "Guess I'm a bigger blamed fool than you when it comes to throwing a Chinaman's gold about. "We'll keep our word to the hospital."

And they did.