RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"BULLY" HAYES was a notorious American-born "blackbirder" who flourished in the 1860 and 1870s, and was murdered in 1877. He arrived in Australia in 1857 as a ships' captain, where he began a career as a fraudster and opportunist. Bankrupted in Western Australia after a "long firm" fraud, he joined the gold rush to Otago, New Zealand. He seems to have married around four times without the formality of a divorce from any of his wives.

He was soon back in another ship, whose co-owner mysteriously vanished at sea, leaving Hayes sole owner; and he joined the "blackbirding" trade, where Pacific islanders were coerced, or bribed, and then shipped to the Queensland canefields as indentured labourers. After a number of wild escapades, and several arrests and imprisonments, he was shot and killed by ship's cook, Peter Radek.

So notorious was "Bully" Hayes, and so apt his nickname, (he was a big, violent, overbearing and brutal man) that Radek was not charged; he was indeed hailed a hero.

Dorrington wrote a number of amusing and entirely fictitious short stories about Hayes. Australian author Louis Becke, who sailed with Hayes, also wrote about him.

—Terry Walker

"HARD up! I guess we hadn't enough dollars to buy a pound of salt."

Captain Hayes sprawled in a hammock on the verandah of the Sourabaya Hotel, where the big surf thundered over the glittering stretches of beach.

Half a dozen captains, Australian and Scandinavian, slouched in the palm shadowed verandah, all more or less interested in the big-voiced man in the hammock. On the verandah steps sat a little black Jew pearl-buyer from the Gulf of Papua, a tattered sarong drawn about his lean shoulders.

"A sailor is hard pushed," continued Captain Hayes, "when he sits down on the Equator and eats up a cargo of Chinese eggs. We were bound from Swatow to Calcutta in my old schooner The Daphne, and we hit the biggest calm that ever fell on the Bay of Bengal.

"Before leaving Swatow an old Chinaman named Kum Sin packed the eggs in a tank of lime and stowed 'em away for'r'd. He said the people of Calcutta were yearning for preserved eggs. Of course I didn't believe him, but seeing that he only demanded a few ounces of opium in exchange it looked a likely investment for me.

"Well, this wind-blight fell on the Bay of Bengal, and held us for seven unholy weeks. I carried an Australian crew, lank, beef- eating men, with the appetites of whales. Food seemed to make 'em hungrier. After cleaning out the pork casks and licking up a consignment of tinned fish, one or two of 'em began to talk mutiny.

"I promised myself, when a boy, I'd never pull a gun on a hungry mutineer, so I called the cook and asked him if he couldn't make soup of the empty pork barrels—I'd seen it done on a South Sea whaler, and nobody was ever the worse for it.

"The cook looked at me for sixteen seconds, and then let himself go. He told me it was the first time he'd ever sailed in a wood-boiling ship. He asked me if I'd like some stewed hen-coop for dinner; he said he could put a couple of empty bird-cages in to give it a nice flavour. Then he offered to fry the india- rubber deck-hose if I'd allow him to sweeten it with three ounces of cucumber.

"There was too much levity about that cook, and there was no need for him to have dragged in his bit of cucumber. I felt almost justified in lowering his wages; it was better than hitting him on the face with a deck-scraper.

"My first mate, Bill Howe, stepped forward and pointed out that a tank of preserved eggs was stowed away in the schooner's fore-hold. 'About four hundred gross,' said Bill dismally.

"I advised 'em to try a few and not make gluttons of themselves. Nobody ever accused me of swallowing tank-eggs in tropic weather, although I've seen Chinamen eat 'em by the handful.

"We opened the tank and lifted 'em out of the lime: some were no bigger than pigeon eggs; others had been laid by big Chinese geese, and were nearly a pound weight. The cook boiled the first lot, and for three days the schooner looked as though we'd passed through a storm of egg-shells. Everybody said they liked eggs. Flannaghan, the carpenter, admitted they were a bit strong in the yolk, but nobody cared so long as a slight breeze was blowing.

"The crew went aloft, their pockets bulging with hard-boiled tank-eggs, and, whenever one of 'em slipped and fell, you could hear the eggs bursting around him.

"On the fourth day the cook started to curry 'em, for a change. He said it gave the men's appetites a chance. Too much boiled eggs made Jack a dull boy. The smell of curried tank-egg floated around the ship for nine days; it used to hit me between the eyes like the breath of a land-agent. The boys didn't seem to mind until Flannaghan swore he could hear the eggs crowing at daybreak. Reports like these had a demoralising effect, and the next day each man came to me and declared that he had to kill his eggs to prevent them making a noise in his face.

"I lived on a cheese diet for six weeks in North Queensland once, but it was wholesome and refreshing compared with curried tank-eggs. Day after day the cook served 'em up boiled and fried, frittered and scrambled. He did all that was possible to turn an egg into something else, till the crew howled whenever he appeared carrying 'em down the alley-way.

"Day after day the ocean lay around us, milky, white, and greasy, with the sun flaring overhead like the front window of Tophet. The men loafed under the fo'c's'le awning, a pea-green look in their eyes that turned to yellow whenever the cook came out of the galley and asked them if they'd like some eggs.

"Things were looking from dull to middling when the sky changed suddenly, and the whip-end of a monsoon hit us from the sou'-east. For eight days we slammed around, with a blamed whisky-coloured typhoon sitting in the sky pumping down rain and belting the sticks out of us. After eleven days of it, we made, as near as I could reckon, the mouth of a big estuary that looked and smelt like the Ganges.

"We lay at anchor, not a biscuit-throw from the shore, and the great Indian sandbars piled themselves around the schooner as the tide ran out. A couple of adjutant birds stood on separate mud- banks where the big-snouted crocodiles basked at the foot of an ancient gate.

"We wanted stores for the run home to Australia, and a suit of sails to hang the wind on. None of the boys had seen their pay for nine months, and the first mate had to borrow my sea-boots to go ashore in.

"Higher up the river we made out the dome of a white-walled palace showing against the sky. It was a comfortable-looking place, with the early sun streaming over its copper and gold roof-ornaments. I reckoned if a company of smelters could have boiled the palace down there'd have been enough bullion in the pot to start a mint.

"Higher up the river we made out the dome of

a white-walled palace showing against the sky."

"'We'd better take a walk ashore, Mr. Howe,' says I to the mate. 'Maybe there's a few metal gods about that ain't screwed down. Many a poverty-whipped white man has come back from a walk through India with his pockets full of gold door-knockers.'

"We pulled ashore in the dinghy, and strolled up the river for a couple of miles to where a mob of drab-coloured little buffaloes were swishing about in the wet paddy fields. We passed through a dog-haunted village, followed by a crowd of natives who waved their arms and called me and Bill names for crossing their fields.

"An old priest with sheets in his hair hung in our wake and refused to go home. He pointed to our schooner down the river and made objectionable speeches in Hindu.

"Then we ran into a long-footed Brahmin, who salaamed and hit the earth three times with his brow before speaking.

"'You have come,' says he at last, 'to visit his highness Petima Singh?'

"'We're moving that way,' says I. 'Maybe you'll run ahead and tell him we're about to arrive. Tell his highness that we have dared the perils of the sea to gaze upon his medium-sized face.'

"The old Brahmin skeltered ahead with the news of our arrival. We followed down the hot road, where the crows swarmed in front of us and settled on the walls of a dead city that lay hidden in the piled-up sand and river garbage.

"The palace with the dome stood in the centre of a courtyard. The floor of the yard was inlaid with blue and yellow tiles; a couple of stone elephants leaned against the gateway; and the white marble columns were as thick as ghosts in a ruined abbey.

" Keep your eye on the loose gold and silver, Bill,' says I. 'Anything that isn't screwed down will be treated as cargo.'

"We followed the old Brahmin across the courtyard until he stopped at a big black door, carved and gilded from knob to hinge. A servant opened it, and we passed through into a wide hall that sparkled with fountain spray and splashing water. A pair of peacocks walked away as we entered. Bill pointed to the foot of a white throne at the end of the hall, where a big Indian cheetah lay licking its chest and yawning like an overfed tiger.

"Somebody hit a gong until it buzzed and called up a crowd of coolie servants, who salaamed in a mob before me and Bill Howe. One of them, a kind of serang with a three-prong caste-mark on his brow, addressed me in his best Sunday English.

"'You are Heslinger, the wrestler, are you not?' says he. 'His highness has long expected you.'

"I looked hard at the man and smiled peacefully, because I didn't want to answer his question in a hurry. I like time to breathe between one lie and the next. You never know whether these Indian princes are going to present you with a gold snuff box or a policeman.

"'I'm travelling under a theatrical nom-de-plume at present,' says I at last. 'Heslinger will fit me, anyhow.'

"He salaamed again, and clapped his hands. 'You are in time for the games, most noble Heslinger. His highness Petima Singh will speak to you in a little while. Pray rest yourself,' says he.

"It came to me in a flash that we had walked into the palace of a sporting rajah, who was expecting the arrival of a troupe of professional white wrestlers. Lots of these nabobs engage English and German athletes to appear at their festivals and durbars.

"I didn't quite see, though, what was coming next. But it seemed good enough to fall in with a programme when it had been drawn up by a prince with a gilded dome on his house. There were not many sailors south of Port Darwin who cared to try a Cumberland hold with me. I'd learnt a few wrinkles from the Jap shellers in the Straits—enough jitsou and garotte holds to stave off a sewing-machine agent, anyhow—and I didn't mind taking Heslinger's place in the bill if the man I had to meet was willing to make it a fair go.

"I turned to the native with the caste marks on his brow, and called him aside. 'Who is the gentleman that's billed to meet me?' says I off-handedly.

"'It is Gezirah Khan, the Cabuli,' says he. 'He arrived here two days ago. His fame as a man-killer has travelled beyond the Himalaya. He has wrestled at the Court of the Amir, and at many Indian durbars before our Imperial Viceroy. In his last bout at Delhi with Mastro Sahib, the Italian, he strangled his man in thirty seconds.'

"'Where is he now?' says I casually.

"'In the palace yard, pining to meet the noble Heslinger,' says he.

"'If you can prevent the noble Gezirah Khan from pining too much, we will be pleased to look at him before business commences,' says I. 'His smile mightn't agree with us.'

"He hurried away with my message, and we sat in the hall watching the big, lazy cheetah sunning itself in front of the rajah's white throne.

"'This is going to be a big thing, Bill,' says I.

"'I hope it won't be worse than the tank-eggs, cap'n,' says he. 'No man could wrestle an undersized fowl after a trip like ours.'

"The furniture and scenery of the courtyard pleased me more than Bill's words. A swarm of blue-haired apes ran along the wall carrying tiny gold chains on their arms and wrists. They sat watching us for a bit, chattering and pointing like little native men and women. The smell of flowers and the sound of falling water made us feel drowsy after our long walk from the schooner. I was more than half asleep when the door swung open, and the clatter of sandalled feet filled the passages.

"The cheetah looked up and bared its lips half playfully, then bounded across the yard, purring like a giant cat. I stood up as the servants trooped in from the passages, waving several acres of feathers in the air; in front walked his highness Petima Singh.

"He was a small, ladylike young fellow, with thin legs and a long, hatchet face. A necklace of rubies hung from his small neck; there was grease-paint on his lips and cheeks; and from head to heel he was a mass of sparkling stones. I reckoned you could have pawned him for one hundred thousand dollars without touching him with the acid.

"He looked at me sharp and quick, judging my reach and gripping-power in the slant of an eye; and as I looked down at him I saw the big yellow cheetah fawning at his heels.

"'Heslinger,' says he coldly, 'who is your friend?' He nodded towards Bill standing beside me.

"'His name is Professor Marvaloni, your highness,' says I, salaaming. 'He is my understudy and trainer.'

"His highness threw his eye over Bill, then stepped up to me and passed his thin hand over my chest and biceps. 'Your weight, Heslinger?' says he sullenly.

"'Fourteen stone and a touch, your highness; I'm as hard as a blacksmith, and quick as your pet cheetah. Still, I'd like to see the man who's matched against me,' I put in.

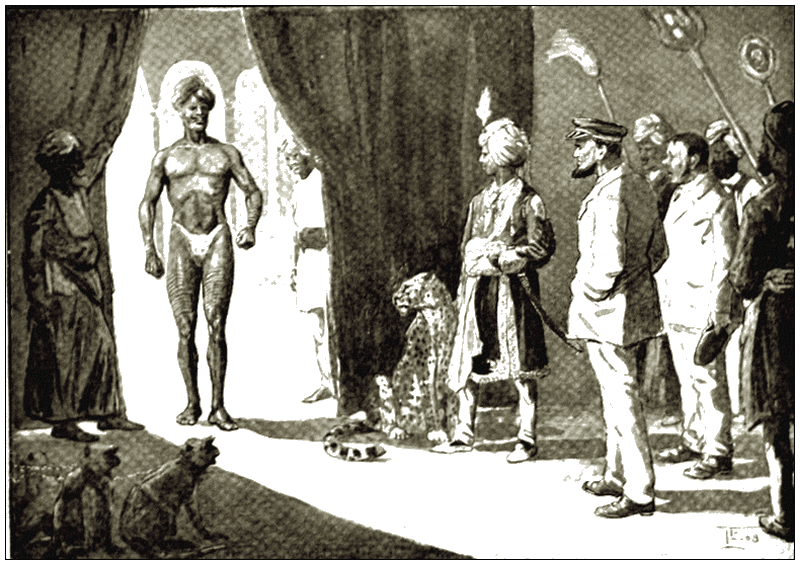

"His highness smiled like the cheetah, and nodded to one of the servants. 'Bring forward the illustrious Gezirah. Let the white sahib look upon the tiger of our northern hills, whose grip is death, whose muscles are stronger than English steel.'

"I heard Bill groan behind me. 'If you'd been feedin' on anything but tank eggs, cap'n,' he says, 'I'd put my last half dollar on you.'

"The servants ran out, and the curtains in the main hall were pulled aside smartly. I looked up and saw a coffee-coloured Pathan striding down the passage. He was stripped to his loin cloth, and stood seven feet in his bare soles. From heel to chin his body shone with grease and good condition. Heaving himself into the centre of the hall he folded his arms and bowed like a blamed actor.

"He was stripped to his loin cloth, and stood seven feet in his bare soles."

"'Bully,' thinks I, 'you've met men in your day—but this is an avalanche with grease on it.' His thighs and arms were bound up with bull-hide thongs, the muscles of his jaw and throat stood out in solid bunches.

"'Gezirah Khan,' says I, looking into his eyes, 'I will do you the honour when his highness names the hour and place.'

"He looked over at me, and I saw his big white teeth behind the thick heavy lips. 'There will be no honour, white man, only death for one of us.' He strode across the hall, and his muscles seemed to leap and jolt as he stooped to pick up a thick chain one of the servants had thrown near him. Seizing it be snapped it asunder with a lightning jerk of the hands. Doubling the chain he broke it again, and flung the bits at my feet.

"'Thank you, Gezirah Khan; I've seen that trick done among camel-men and circus pimps,' says I.

"The Afghan blood rose to his head and eyes; he appeared nettled at my words. Catching up a stone table that stood in the centre of the hall, he raised it in the air as though about to snap it with his huge hands.

"'Enough, thou ....!' His highness turned to him a bit sharply. 'These feats of strength are out of place, Gezirah Khan. Tricks of foot and body, deeds of skill, we desire to see. To- morrow you shall wrestle the white man here, after my swordsman has competed with the Japanese fencer Yamish Wari, from Tokio.' His highness nodded to the servants. 'Take these athletes and give them food. The white man is hungry; he has come from over sea.'

"I was taken with Bill up a long flight of marble stairs to a big living-room overlooking the courtyard. The servants brought us fruit and hot-baked loaves, with some coffee and tobacco thrown in.

"Bill ate like a starved dingo, and looked at me from time to time as though he'd made up his mind about my funeral.

"'You never did 'ave much luck in pickin' your man, cap'n,' says he. 'That black feller's high enough to wrastle a bunch of lightning rods.'

"'You've seen me wrestle, Bill,' says I. 'You saw me handle Barney Cafferty, the Irish policeman, in Sydney, last year. You won't deny that I repaired a broken footpath with his head.'

"Bill waved his hands at me sorrow fully. 'I've seen you wrastle, cap'n, and I've known you to roll men into bundles an' put 'em out of harm's way. But this Gezirah Khan is goin' to lift the veil for you; he's goin' to lead you into the valley of the shadder; he's goin' to turn you into an angel with a broken neck, Cap'n Hayes.'

"Bill always made me feel tired, and I didn't like his reference to the angel with the broken neck. All day the palace was guarded by crowds of servants trained in the use of arms. Bill wanted me to climb down the courtyard wall and get back to the schooner as soon as it was dark, but I felt that I'd sooner face the Afghan than be caught sneaking from the palace.

"The servants told us there was to be a combat of elephants the following day within the palace grounds. Visitors from all parts of India were flocking in to see the fun, and the native papers were whooping about their black man-eater Gezirah Khan and the fool Sahib Heslinger who had come to die in his arms.

"I lay on a settee and tried to sleep, but the night came up hot as a furnace, and the moon seemed to walk into the room and blind the eyes. Every time I dozed, the black figure of Gezirah Khan, with his heavy jaw and huge hands, seemed to be standing over me.

"I got up savagely, and strolled in my bare feet to the verandah overlooking the courtyard. A bit of a breeze was moving the stiff palms that stood in rows about the square. The marble columns and the white shrine at the end looked ghastly in the moonlight.

"A jackal yelped along the river bank, and the village pariahs fluted back in chorus; in the south, as far as you could see, there was nothing but the slow-moving Ganges and the smoke from the ghat.

"Below me, on the eastern side of the palace, was a latticed window with a carved stone god of Indra squatting on top. Through the hot night I had heard the voices of women talking and singing. It was all Bengali to me; but now and then I caught a voice that spoke in English to the others. They were telling each other about the durbar, and the great wrestling match between the white English lamb and the Cabuli tiger Gezirah Khan.

"They must have known that I was quartered in the apartment overhead, for whenever I strolled along the balcony they made great efforts to let me hear their talk. Good thing for them that the prince was at the other end of the palace entertaining his guests.

"I stooped over the balcony once, and quick upon it a small voice called me by name, and stopped short as though something had frightened her. A strip of filigree lace stuff fluttered through the half-open shutter. I heard the jingle of wrist ornaments.

"'Heslinger Sahib, art thou above?' says the voice. I was pretty certain that it belonged to one of the educated zenana ladies, and I was not the man to allow the thoughts of a wrestling-match to spoil an hour's flirtation. Stooping over until my chin almost touched the head of the stone god above the window I answered in my best manner:

"'Heslinger is here, lady. Your voice is sweeter to him than drops of wine or golden-lip pearl. Speak.'

"'It is this, Heslinger... listen!' (I could hear the tinkle of her jewellery, and I breathed the scent of her hair when she settled near the casement.) 'Gezirah will kill thee at sunrise, sahib, just as he killed my father in Benares seven years ago.'

"'I am not your father, lady of the harem, neither will Gezirah kill me at sunrise,' says I.

"Her words nettled me, for no white man likes a lady to tell him that he will die at the hands of a big, greasy Pathan.

"'Gezirah will kill thee, Heslinger. There is death in the joint of his middle finger.'

"'In the joint of his middle finger!' I rapped out. 'The gods have been good to the black man, lady, if he can slay people so easily. It generally takes an axe and a pound of bullets to hurt men like me.' I didn't let her hear the last bit—it wouldn't have been polite.

"I reckoned, by the way she leaned against the lattice, she was heart and tongue in my favour. 'Beware of Gezirah, for he will first blind and then stifle thee, Heslinger.... The black ring he wears is made of iron. It is hollow... full of red poison given to him by Azar the Cabuli witch-doctor. It touched my father in the first fall, and he rolled at the feet of Gezirah... blind, vomiting. Remember, Heslinger, or thou wilt die blind at the feet of the Afghan.'

"I heard the lattice window shut with a snap. Then a zither instrument started to twang and fret inside the shuttered zenana.

"Peering beyond the courtyard wall I could just make out the turbaned mahouts bustling about the grey-roofed elephant sheds at the back of the coolie lines.

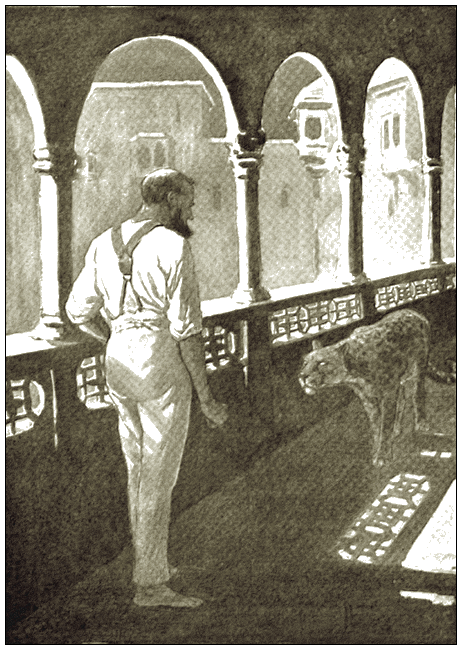

"Something moved behind me—some thing with a long, cat- like body and flaming eyes. The shadow of it sent the blood leaping from my heart. I watched it as it drew nearer and crouched at my feet, its eyes staring into mine.

"It was the rajah's cheetah prowling around for something soft to roll against or play with. The brute seemed tame enough and half friendly. I stooped and rubbed its leopard-like head gently, while its big forepaw dabbed at my hand playfully. "'Down, beast!' I said quietly. 'Down!' It wanted to fawn and roll against me, and the weight of its body almost knocked me off my feet. I turned across the balcony and looked below suddenly. A shape was moving to and fro in the shadow of the colonnade, with the regularity of a sentry on guard.

"It was the rajah's cheetah prowling around

for something soft to roll against or play with."

"I began to count the steps for want of something to do, like a man who could not rest or sleep. Up and down went the shape, and when it reached the end of the passage it stayed to fill its lungs with air.

"I leaned over the balcony and waited. The shadow passed down the aisle, stopped and returned, and I saw that it was Gezirah Khan exercising and stretching his great limbs from time to time. His arms shot up and down and over his head, whirling around in the moonlight like a spring-fitted machine.

"I had no wish to meet or avoid the man; but I hated him and his blackguard strength. I hated his merciless eyes and his long garotter's hand. He would kill me at dawn, I felt certain. I was untrained practically, and I'd been living on salt meat and eggs for three months, yet I didn't want to be beaten before a crowd of Indian princes and sporting nabobs. Gezirah would amuse them by playing with me for a little while until they tired; then he would end the game by slowly strangling me or breaking my neck.

"I took a turn up and down the balcony to clear my head and to kick myself for jumping into a fool's position. The real Heslinger was probably on his way to meet the Afghan, and he would arrive in time to attend my funeral, I thought.

"Slipping softly to the balcony I peeped cautiously over. Gezirah was standing beneath, driving his long black arms up and down, shooting them in and out with lightning speed. The sight of him almost made me sick.

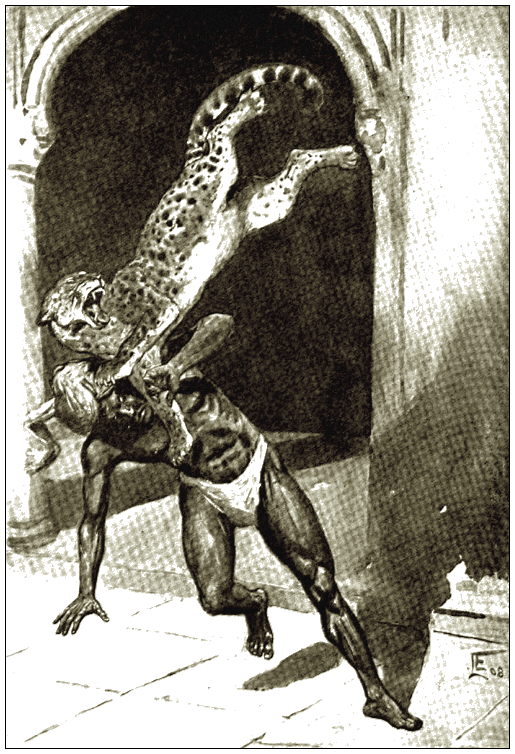

"Turning again sharply I nearly fell over the cheetah rolling at my feet. Without stopping to think I put my arms round its throat and body, and heaved—heaved it over the parapet on to the head of the Afghan below.

"His body was half bent as the clawing, snarling mass struck him full on the neck. Man and beast rolled in a yelling heap across the courtyard, cheetah on top, Afghan below—Afghan on top, cheetah below—that's how the fight went on.

"The clawing, snarling mass struck him full on the neck."

"The pair were as well matched as anything on earth could be. The cheetah fought because it was hurt and frightened; the man gripped and hammerlocked, with the fear of death and the big yellow teeth tearing at his throat.

"Gezirah flung it to the ground and tried to kneel on its wriggling body, cursing in his Mahommedan lingo as the powerful brute smote him chest and hip with its heavy paws. It was the unholiest scrap ever put up between two fighting animals, but the man won in that long up-and-down scramble.

"He fastened the cheetah throat and paw to the courtyard pavement, and he lay on its squirming body and shouted for help.

"The mahouts came running in and dragged the pair asunder. I saw Gezirah stagger to his feet and reel across the courtyard as the elephant-men hauled the cheetah through the open gate.

"I turned in and slept till daylight. There was a commotion in the courtyard when I strolled down, stripped to the waist, ready for the contest. I whistled as I exercised up and down the yard, where the doves cooed on the roof of the white shrine, and the peacocks spread themselves in the morning sun.

"One of the servants hurried up to me after a while, his eyes bulging with news. 'There will be no wrestling—match, Heslinger Sahib,' says he.

"'No match!' says I. What do you mean?'

"'Gezirah Khan is hurt,' says he, wiping his brow. 'He was attacked by his highness's cheetah at midnight and badly mauled. He will not wrestle again for months. He is very sick and sore, sahib.'

"Half an hour later Petima Singh came to me with an apology in his small eyes. 'The match is postponed, Heslinger,' says he. 'My cheetah has spoiled Gezirah Khan. I would have given much to have seen you at death-grips with each other.'

"'Pardon me, highness,' says I. 'Do I suffer by this sudden breach of contract? I have come far to meet this Gezirah Khan. My crew are unpaid, my stores are low. Your highness will see that I am not a sufferer?'

"'Speak, dog!

"His narrow eyes clouded for a moment; then he turned to one of his saises. 'Give Heslinger five hundred rupees,' says he; 'and provisions for his schooner.' He threw me a nod as he passed out.

"I met Bill Howe tearing down the steps into the courtyard, a dazed look in his eyes, as though he'd only just got out of bed. 'Cap'n,' says he, holding my arm, 'did you lick him?'

"'I would have if the cheetah hadn't,' says I.

"We got aboard the schooner at mid-day, but before leaving I promised his highness that I would wrestle Gezirah Khan whenever he was fit and well.

"The servants carried the stores aboard, and as much rice as we could stow in the fore-hold. Standing in the break of the poop, towards dusk, I noticed a covered bullock-cart trundling along the river bank in the direction of the palace. Half asleep inside was a bullet-headed, big chested German, his great legs sprawling across the cushioned seat.

"I hailed the driver smartly, and the cart pulled up. Stepping down the gang way, I saluted the German as he thrust his head from the door.

"'Good evening, Meinheer Heslinger,' says I politely. 'I trust you are in excellent condition."

"He looked at me sulkily, and I could see the muscles flinching under his silk coat as he craned forward. 'My name vas Heslinger,' he growled. 'I haf not der bleasure of your acquaintance, anyvays. What do you vant mit me?'

"'Permission to bask for a moment in the sunshine of your magnificent countenance,' says I humbly. 'You may now proceed.'

"He swore impatiently as the bullock cart passed down the road towards the palace. By the time he had reached the outer gate we were well under way.

"Still, I'd like to have been there when they announced his arrival to little Prince Petima Singh."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.