RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"BULLY" HAYES was a notorious American-born "blackbirder" who flourished in the 1860 and 1870s, and was murdered in 1877. He arrived in Australia in 1857 as a ships' captain, where he began a career as a fraudster and opportunist. Bankrupted in Western Australia after a "long firm" fraud, he joined the gold rush to Otago, New Zealand. He seems to have married around four times without the formality of a divorce from any of his wives.

He was soon back in another ship, whose co-owner mysteriously vanished at sea, leaving Hayes sole owner; and he joined the "blackbirding" trade, where Pacific islanders were coerced, or bribed, and then shipped to the Queensland canefields as indentured labourers. After a number of wild escapades, and several arrests and imprisonments, he was shot and killed by ship's cook, Peter Radek.

So notorious was "Bully" Hayes, and so apt his nickname, (he was a big, violent, overbearing and brutal man) that Radek was not charged; he was indeed hailed a hero.

Dorrington wrote a number of amusing and entirely fictitious short stories about Hayes. Australian author Louis Becke, who sailed with Hayes, also wrote about him.

—Terry Walker

THE game of "watching the bank" was being played at Emu Creek with relentless persistence. At the first news of gold, crowds of South Sea adventurers had swarmed into the Straits, where their swift-sailing schooners fluttered like hawks on the blood-scent.

The bank itself was of no importance from an architectural standpoint, and would have been hoisted bodily from its foundations and looted at leisure but for the presence of six troopers wearing the uniform of the Queensland police.

A breast-high stockade had been erected round the building; a narrow gate permitted two men to walk abreast into the buying- room. When three attempted to pass in a hurry, a voice spoke admonishingly along the barrel of a carbine; the third man usually fell back with great speed until the order was given for him to enter.

Gold was being brought in from the remote regions of the Palmer River and the Kennedy, escorted by gangs of Chinamen and big-chested Malays, armed with kris and long-bladed knives. No man travelled alone with newly-won gold or reef-specimens in his possession. The business of the hour was to keep at bay the little parties of gold-trackers, who followed men to their pegs and claimed tribute at the point of the rifle.

It happened that Captain William H. Hayes had pegged out an acre of gold-bearing reef at White Marble. Eight kanakas and half-castes were employed in the workings: a quantity of rich stone had been already packed at the mine-head awaiting treatment. From dawn till long after dark the kanakas sweated in the narrow drives, tunnelling and staying with timber the loose schist-like formations that threatened at times to engulf them.

Hayes, stripped to the waist, stood by the windlass hauling great buckets of chrome-coloured slime from below. For the hundredth time in his life he saw fortune looming ahead, and he vowed that the sea would know him no more if the earth would provide him with honest meat and wine.

From every pot-hole and sand-heap bobbed a Mongolian head; the creek beds and flats were alive with the scum of Swatow and Shanghai. They wandered in bands over the field, dogging the white miners to their claims, fighting like hyenas among themselves whenever a penny weight of quartz was in dispute.

They came from the solitudes of Cape York and the Batavia River, from Hannibal Island and the jungled foreshores of the Great Barrier; it seemed as though the very wind had blown the news of gold about their ears. And wherever a white prospector drove his pick, Ah Sin and Kum Yow would pitch their camp along side and watch developments.

The big white barbarian, Hayes, sweated through the long hot days unmolested. The yellow invaders had studied him singly and in groups. They walked round his claim, and their throats grew hot at sight of the gold-veined quartz gleaming within the tunnelled drive. They watched him and pondered, and their coolie hearts grew white when he swung through their lines alone and unarmed.

"Him no goo'!" they chattered. "Him one size too big. Hi, ya!"

The buccaneer responded without heat or malice.. "I'm not big enough to lick you all, Children of Heaven, but if you'll pile yourselves my way about a score at a time, I'll reduce the blamed fighting to a minimum."

"By clikey, you wait!" A hundred clawing hands swept towards him. "We catchee you, byemby. Yah, hah, Cassima!"

Hayes shouldered through the reeking crowd good-humouredly. "The right man is going to belt you, Children of Heaven, first time you put your pigeon toes inside his claim. And you don't know how hard that right man can hit."

The end came unexpectedly, and Hayes' career as a gold-miner terminated abruptly. One morning a trooper picked his way across the gully and cantered down the coolie lines to where the big white man was standing at the windlass head. Nodding briefly, he demanded to see the buccaneer's mining certificate.

The moment the trooper halted at the White Marble, seven hundred Chinese "swampers" threw down their tools and surrounded the white man's claim. No word was spoken. The end of the big barbarian had come. His rich reef would fall to the gang of "jumpers" who first leaped between the pegs and held their ground.

"Your certificate, Hayes," repeated the trooper sternly. "I want to see it."

"Guess you'll have to sell me one," said the buccaneer innocently. "I've been too busy improving my claim to pay attention to your mining laws."

The trooper frowned and fingered his carbine restlessly. "You'll have to forfeit. I'm acting on orders. Mining in this colony without a licence is illegal. Call out your men." Backing his horse to the head of the mine, he took his stand by the windlass.

In his haste to begin work the buccaneer had neglected to provide himself with the necessary certificate, which would have given him undisputed ownership to that portion of the reef enclosed within his four pegs. Therefore he argued his case a little defiantly until the trooper grew hot and impatient. The proceedings were intensified by occasional yelpings from the army of Mongolian "swampers" that lined the surrounding ridge.

Technically the buccaneer was in the wrong; morally he was entitled to every pennyweight of gold found within his four pegs. Had the trooper been an older man, he would certainly have allowed an hour's grace wherein to comply with the laws of the land. Instead, he unslung his carbine and spoke three nasty words to the man whose courage was the admiration of every British and American sea captain trading within the South Pacific.

The seven hundred "swampers" closed about the mine-head, whimpering like dingoes at sight of the gold-fretted reef that bulged picturesquely from the sides and roof of the chrome- coloured drive.

Hayes laughed bitterly and shouted a word to his kanaka workmen in the tunnel below. Wiping the clay and slush from his hand and boots, he prepared to vacate his claim without further parley. Resistance was out of the question. A single shot fired in anger would bring the gold-warden and a hundred white miners at his back to enforce the law of the country.

The rattle of the trooper's carbine as it fell into its leather bucket finished the inquiry. Hayes stepped from the mine enclosure and lit a cigar.

"My compliments to your Government, young man. And you may tell 'em from me that they've whipped the wrong tiger." He glanced back for a moment at the yellow army that spilled over the sand ridge into his claim. His pegs were uprooted by a score of clawing hands. Down the sides of the shaft poured the coolie leaders, scraping the face of the reef with naked hands, hacking and pulverising with knives and picks wherever a speck of gold shone in the water-worn fissures.

Hayes saw the futility of pitting himself against the army of mine-stealers. More over, he was certain that the gold-warden at Emu Creek had received instructions from the Queensland Government to drive him from the country. His recent exploits in the South Seas had caused a spirit of apprehension to pervade the Department of Navigation. Certain harbour officials had watched and reported his movements with more than Christian curiosity; and, with a well-equipped tele graph service at their disposal, the art of harassing William H. Hayes had been practised with considerable success.

Worse than all, a gunboat had shadowed his schooner from Rockhampton to Cairns, and had prevented him landing at a moment when he desired to take in stores and fresh water.

While exonerating the captain of the gunboat, his wrath blew white and red at the loss of his mine—the weeks of slavish toil spent in ground-sluicing and cross-cutting non-payable areas of reef; and at the moment when gold had been struck the Queensland officials had offered him up to the greed of seven hundred unlicensed "swampers."

He retired sullenly to Sing Foo's boarding-house, a rat-ridden bungalow, overlooking the Straits where the Queens land-bound ships headed for the still waters of the Great Barrier Reef. From the back rooms and verandah came the rattle of dice, the guttural oaths of the puffy-necked, rubber-chafed Scandinavian divers, the stammering protests of the little Jap shelters who periodically looted the rich oyster swathes north and east of the Vanderdecken Banks.

Men glanced covertly at Hayes as he smoked in the verandah hammock; few ventured to pass the time of day, since no man knew when his rage would over-spill, scattering them like frightened dogs.

It was hinted among the Malays, gambling in a near room, that the big Tuan intended to wring the Government's neck at the earliest opportunity. A French refugee from Noumea tip-toed across the verandah and in a stifled whisper suggested an up- rising among the miners who had suffered ill-treatment at the hands of the Government.

Hayes twirled his thumbs, looked coldly at the ex-convict, and snarled him into silence. "Out of this, you cut-throat! I guess the air is full enough of poison already."

The ex-convict skipped back gesticulating violently. "Parbleu! You grunt like ze lion," he quavered. "I have no wrong done."

"You invite me, a white man, to captain an army of mongrel chows, that would die of heart trouble if a British blue-jacket sneezed within a mile of 'em. Pshaw!"

"Ze Government steal your mine. Sacre! I would keel it!" The French man expectorated effusively. His left hand stabbed the air as though illustrating his method of dealing with tyrannical Governments. "I would keel it!&mdash keel it!" he choked.

The buccaneer eyed him sombrely. "Go and have a drink, m'sieur. There's a barman over the way named Von Bismarck or something. Talk to him, and quit here. You're too blamed mercurial for a revolutionary."

The eyes of the township were on the panther-footed Hayes as he padded up and down the narrow street, his wide-peaked cap jammed over his brow. There were ruffians among the crowds of miners and trepang fishers, whose names were recorded in the gaol-books of every Australian city, yet no one among them cared to criticise or rouse him from his sullen meditations.

"I tink it vas alride to leaf him alone," grunted a German sheller. "De Queensland bolice vas foolish to blay tricks mit him. Der shwampers haf taken his claim, und dey vill bag his gold quartz, und gamble der money. No man mit blood in him vill stand dot."

The buccaneer was astir the following dawn long before the wine-red sun had flooded the Gulf with streaks of fire and opal. Smoke drifted from a hundred Chinese camps in the gullies and drifts. Far away in the south a few buffaloes roamed on the edge of the mangrove-skirted flats.

Loafing towards the pier, he stepped into a dinghy lying at the foot of the steps and pushed off. He carried with him a long leather bag and an old fowling-piece. He did not go unperceived. A couple of ancient fishermen watched him curiously.

"Cap'n's goin' to shoot black duck," ventured one. "Got some whisky an' sandwiches in the bag. Last time he went shootin' he nearly put his foot into a crocodile's mouth."

"Aye, he did," assented the other, "an' if the crocodile had taken his right foot he'd have jumped on its head wi' the left." The two ancients chuckled in chorus.

Hayes rowed leisurely across the warm, sunlit bay until he rounded a small wooded promontory in the north. Here the wind from the Straits blew suddenly about his ears, driving the boat into a short choppy swell. About a mile to the east lay the Skull Rock lighthouse, its great coppery dome glinting redly where the monsoon-driven sand had scoured it to the colour of gold.

He pulled close inshore until the light house keeper's cottage was plainly visible across the naked headland. A big surf was running on the Barrier side of the Straits. Propelling the dinghy with a steering oar, he shot into a deep inlet that penetrated almost to the foot of the huge stone edifice.

The two keepers who lived on the promontory were unmarried, and Hayes knew for certain that both were at that moment smoking in a wine-bar at Emu Creek, where billiards and dice occasion ally helped to alleviate the monotony of their lives.

Wandering inside the palisade, the buccaneer examined critically the nature of the stone work that formed the giant base of the cylinder-shaped lighthouse.

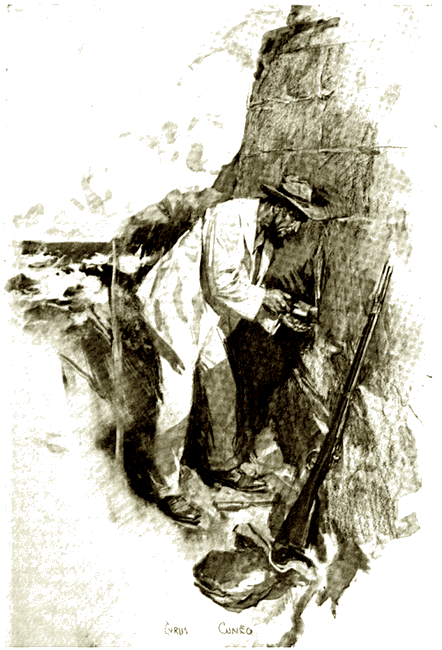

A flock of hawks drowsed over the surf-fretted reefs; the crash of the inrushing tide as it foamed and spilled over the skull-shaped promontory intensified the eerie silence of the place. Taking a trowel from the bag he carried, Hayes walked round the lighthouse base, tapping the gaping, water-worn crevices here and there, scraping between the rough hewn joints where the cement fell away in pieces at a touch from the trowel point.

"Built in a hurry," he muttered, "and it cost a train-load of money, I guess." Opening the bag, he took out a handful of tiny gold pellets, and with the chisel and trowel began to set and mortise them cunningly into the crevices of the huge stone block.

Slowly, methodically, he worked round the gigantic base of the lighthouse, probing and scraping, setting with the skill of a jeweller his glittering crumbs of gold into every water-polished crack and cranny until the massive structure was scientifically "salted" to its foundations.

Setting with the skill of a jeweller his glittering crumbs

of gold into every water-polished crack and cranny...

Examining the rocky base still more carefully, he discovered a softer, schist like stone underlying the second and third pile of masonry. Retiring a few paces he fired several charges of gold- riddled powder at the blocks from various angles. Round and round the base he strode, loading the fowling-piece with microscopic slugs of gold and driving them well into the soft crumbling stone.

Most miners would have laughed at him for wasting so much precious metal in his apparently futile effort to "salt" the giant base of the Skull Rock lighthouse. Neither did Hayes seem in a hurry to be gone: for three hours he laboured with trowel and gun to accomplish his self-allotted task. A merciless sun climbed across the windless sky, and stayed like the hand of a devil on his neck whenever he stooped to punch a gold pellet between the cemented chinks.

Lastly, after a careful survey of his work, he assured himself that the face of the stone showed no signs of trowel or guncraft. The lighthouse-keepers' dog, a small, friendly-eyed spaniel, had watched him from its chain at the rear of the cottage. Passing to the dinghy, he stooped and gently pulled its ears.

"Good little dogs never yap when a man is playing tricks with a gun, eh? Poor old chap!"

The dog fawned joyously at the touch of his hand, and set up a mournful barking when the dinghy shot away from the inlet.

"Too blamed lonely even for a dog," grunted Hayes. "Guess I'll report those two keepers at head-quarters for not attending to their dynamo and reflectors."

The heat of noon hung over Emu Creek; there was no sign of life or stir within the opium houses and pak-a-pau shops when the buccaneer loitered to wards Sing Foo's boarding-house. The big Chinaman was swinging in a hammock, at the verandah end, mumbling to himself from time to time. He moved and blinked lazily at sight of Hayes standing in the shade of the house- palms.

"You look welly warm, Cap'n," he ventured musically. "You find um sun plitty hot?"

"I've been shooting," admitted the buccaneer sombrely. "And while the gun was going off I wondered how much it cost the Queensland Government to build that lighthouse at Skull Rock."

"Welly expensive lighthouse." The Chinaman wagged his bald head for no particular reason. "Take um thlee years to build. Welly handy to lightee big ship at ni'."

"Blamed handy." Hayes fell into deep thought, and the wind- shrivelled palm stems overhead seemed to clank in the silence.

The Chinaman cracked his finger-joints abstractedly. "One, two men Horn lighthouse get welly drunk over the way," he purred. "They come over heah welly early to-day."

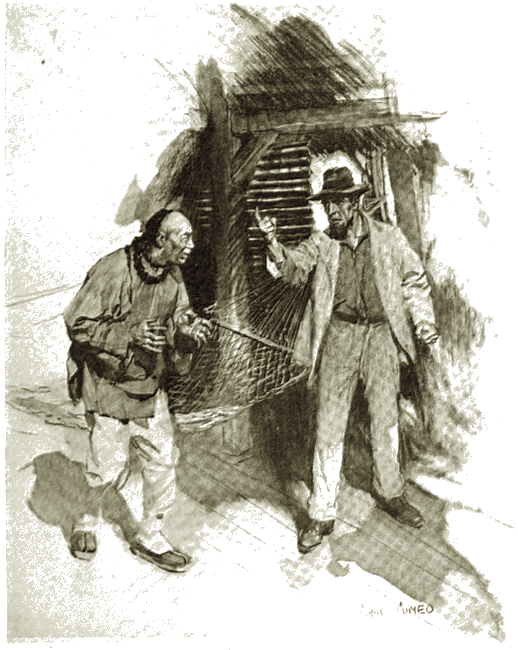

Without volunteering an answer the buccaneer tip-toed to the hammock, stooped and spoke with his face close to the surprised Mongolian's ear.

Sing Foo blinked and moistened his dry lips with the tip of his tongue as he listened to the buccaneer's half-whispered words. Then he rose from the hammock as though some strange key- word had roused him from his imbecile broodings. His long yellow fingers fastened on the white man's sleeve. "Why you tell me that?" he almost wailed. "Why fo' you tell me?"

"Prove it and see," snapped Hayes. "Every block of the stone was taken from a gold-bearing reef. And the fools who built it were blind as the stone itself. From base to dome there's four thousand tons of reef-cut blocks with gold shining wherever the rain and sea has washed."

The buccaneer paced the verandah, and the Chinaman whimpered impatiently and waited for him to speak again.

"Four thousand tons of stone from base to dome," he repeated under his breath. "And every hundredweight would yield five ounces of gold if it was put through that tumble-down battery at the White Marble. Are you any good at figures?" he demanded somewhat savagely of the Chinaman. "How much would four thousand tons of stone pan out at five ounces to the bucket?"

Sing Foo gaped, then he danced and clawed the hot air with his skeleton-like fingers. "You dlive me mad! Why fo' you tell me?" he half screamed. "Oh! why fo' you come here an' tell me?"

"If you repeat it to a living soul I'll put a bullet on your tongue," smiled Hayes. "Don't blow the news east and west until I can fix up things," he added.

"Don't blow the news east and west until I can fix up things..."

The Chinaman cowered from the sombre-eyed man, scarce daring to breathe. "You show me some day?" he asked piteously. "Just one look, eh?"

"See it yourself to-morrow when those two loafing keepers are over the way playing billiards. It won't cost you any thing. My dinghy's at the foot of the pier steps."

Without heeding further the torrent of questions poured upon him by the agitated Celestial, Hayes strode to his own room and locked the door.

There was no mistaking what followed. Glancing from the window swiftly he caught a fleeting glimpse of Sing Foo waddling down the narrow street in the direction of the big Chinese camp at the head of the gully.

Later he heard the voices of the two lighthouse-keepers as they wandered from the wine-bar, across the road, towards their punt, which lay at the foot of the pier steps.

The sun swam like a metal globe on the amber edge of sky; the crying of the gulls and sea-fowl was heard in the hot noon silence—a silence that brought a few perspiring white men to their verandahs, glancing at the sky as though an electric storm was about to shatter the peace of the coming night.

The two lighthouse men sauntered dismally to the pier steps, gripped their heavy oars and pushed off to their desolate abode, where there was neither wine nor music nor the voices of men. Midway across the bay a curious thing happened.

An evil-smelling sampan, with storm-shredded sails and monstrous beak, swooped like an unclean bird from the jungled inlet. The lighthouse men crouched low and shouted a warning, but the great beak smote them amidships, rolling them cursing into the bay. A dozen Mongolian hands reached with hooks and poles, dragging them safely aboard.

No harm was done. The black-toothed Tonquinese captain coughed an apology, and swept on his way to the Vanderdecken Bank, where the pearling luggers sweated and rolled over the oyster swathes.

That night a great darkness fell upon the Straits. The waggon of light that wheeled its warning message to the four points remained unlit. Consternation ran from the islands of the Three Kings to Port Darwin. A Singapore-bound vessel stood off in the black darkness, hooting hysterically and clamouring for pilots. From the Barrier side of the Straits came the fretting sob of a Bombay tank steamer, her black funnel fuming like a hot cigar.

As the night wore, the splutterings of reef-bound vessels grew fierce and bitter, for nothing that walks the land or sea can bellow like a frightened ship. The squealing of launches mingled with the hoarse coughing of island tramp steamers fell upon the town, and Hayes, lying under his mosquito net in Sing Foo's house, laughed at the wrath and confusion he had so suddenly created.

The dawn light liberated a close-huddled fleet of tramps and Java-bound trading vessels from the perilous reef-strewn waters of the Straits. Within six hours of the occurrence, the Queensland Navigation Department learned that the approaches to the eastern seaboard of Australia were in a criminal state of neglect. Mariners were warned that any attempt to proceed to India or Europe via Torres Straits or the Arafura Sea would be to court disaster and shipwreck.

The committee of aged sea-captains who constituted the Board of Navigation, and who were mainly responsible for Hayes' sudden ejection from the White Marble mine, arose in a red heat of obesity, and demanded the names of the miscreants who had dared to kidnap the keepers of their Northern light.

Sixteen highly reputable marine insurance firms, representing invested capital to the extent of twenty millions sterling, hurled their blighting telegrams at the head of the Navigation Department. There were, at that moment, they said, between Port Darwin and Thursday Island, three liners and eight merchant tramps carrying a risk of over six hundre thousand pounds.

Had the Queensland Government gone in for wrecking on a grand scale? they demanded. Were human life and the earnings of the widow and orphan to be scattered ruthlessly about the floors of Queensland's reef-strewn passages?

Many southern newspapers declared that the sexagenarians who composed the Navigation Board were unfit to control an animated dust-heap. Meetings were held throughout the colony demanding their instant resignation.

Several mounted troopers were dispatched overland from Port Douglas, with the intention of arresting every person found in the vicinity of the Skull Rock lighthouse. The gunboat Warrigal was ordered from Brisbane to patrol the narrow straits between Thursday Island and Cape York.

At the moment of their departure, Captain Hayes sauntered along the beach at Emu Creek, his face turned towards Skull Rock. A far-off murmuring of voices reached him that sounded like the droning of a swarm of bees. Clambering up the steep sides of a sand-hummock, he peered through his binoculars at the distant Skull Rock.

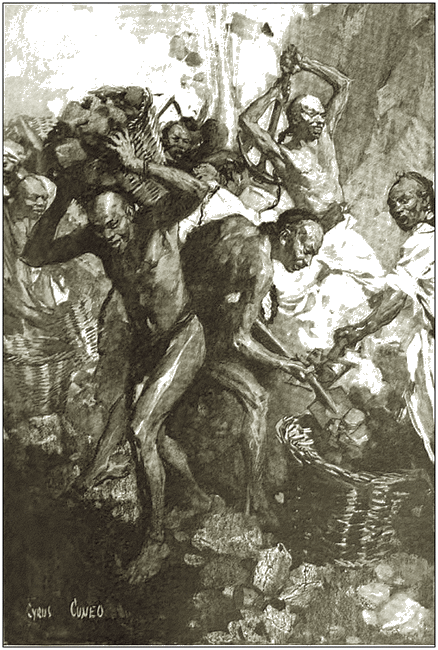

An army of squat shapes were swarming, ant-like, across the narrow peninsula that led to the lighthouse. From where he stood, the close-packed stream of figures resembled the body of some huge reptile winding its great length round the base of the cylinder-shaped tower.

Each squat shape carried a basket and pick, and when it arrived at the light house foot it paused to fill its basket with the crumbling debris that was being torn and rent from the solid piles of masonry by the army of Chinese gold-hunters.

Brandishing picks and spades, they attacked the Skull Rock light with a fierce, irresistible energy that appalled the buccaneer. Occasionally a half-muffled roar told him that dynamite was being used in the assault upon the gold-pitted blocks of stone.

They attacked the Skull Rock light with a fierce, irresistible energy

From all sides of the lighthouse flowed the stream of Chinese coolies in single file, each coolie carrying a basket of broken stone on his shoulder. As far as the eye could see, the snake- like pro cession crawled over sand-hummocks and boulder-strewn gullies until the distant jungle blotted it out.

The army attacking the lighthouse base had blasted out several huge blocks of stone from overhead, while dozens of crow-bars and spades picked and battered the cemented walls until the crumbling stone fell in showers about their feet.

Suddenly, as if by magic, the swarm of pig-tailed workers scattered over the rock-bound peninsula, and as each Mongolian ran, he glanced over his shoulder at the towering mass of stone that looked down upon the wide Gulf waters.

Its copper dome glinted fiercely in the tropic glare. A white- winged mollie-hawk had perched for a moment on the iron rail that circled the lantern. Without warning it rose swiftly, crying hoarsely as it flapped across the bay.

A shaft of flame leaped upward from the lighthouse base, splitting the great tower to its metal-capped dome. A terrific explosion followed, and for one moment the huge edifice leaned and fell, thundering across the peninsula.

Myriads of gulls and sea-fowl flew screaming past the headland, as the army of Chinese wreckers returned to the heaped- up masonry piled along the shore. Like apes they swarmed over the ground, loading their basket with broken stone and fragments of rock. All through the long hot noon the snake-like army traversed the narrow peninsula, depositing its load outside the crushing- battery at the White Marble.

From his post of observation, Hayes saw six mounted men swing over the boulder-strewn track leading from Emu Creek. They wore the uniform of the Queensland Police. Straight as a gunshot they rode towards the crawling band of lighthouse wreckers. The clink of bit and chain reached Hayes as they wheeled full tilt at the pig-tailed column.

The column halted suddenly and watched the oncoming troopers. Then, without word or command from any one, its wriggling length opened to allow the troopers to pass. But the six flashing riders knew enough of Chinese mob methods to refuse the invitation and to halt in a half-circle with carbines at the present.

The buccaneer laughed outright. "Six asses," he said under his breath, "making war on an avalanche."

A short ripple of flame enveloped the police. Retreating ten yards they fired again into the glowing bunches of Mongolian eyes; and again, so coolly that even Hayes held his breath.

The snake-line wriggled convulsively as though something had lashed it. Narrow slits appeared in its body where the carbines had cut it in twelve places. Baskets and picks were flung to earth. The snake was wounded, and it turned its thousand eyes on the white mannikins that blew fire and lead into its body.

"Now," breathed Hayes, "those six asses are going to get the music served up in style."

The serpent line uncoiled suddenly; hundreds of clawing fingers snatched up heaps of loose rocks and stones lying everywhere around. A snarl that resembled the sound of a reef- fretted ocean broke from the Mongolian swarm. Arms and legs seemed to hurl themselves into frantic wire-drawn attitudes. A shower of stones whipped the air in front of the troopers. Then it seemed as though a cyclone of jagged missiles had darkened space. The carbines spat, through the murderous hail of stone that enveloped them, with the accuracy of machine guns. . . .

Mutilated, stoned from their saddles almost, they retreated with their maddened horses to the shelter of the near scrub. The Mongolian line readjusted itself swiftly, and again the procession crawled towards the battery at White Marble.

Hayes returned to his boarding-house and found the streets of the town deserted. Panic, terror, peeped from every shut window and bungalows. The tropic night saw the Straits once more a scene of chaos and hooting, fear-stricken ships. Long past midnight a wailing sound came from White Marble where the army of coolies had been engaged crushing and testing the piled-up debris from the light house. The cry grew louder until it broke into screams of pent-up rage.

Each coolie standing in the sweating darkness of the battery had learned from the tell-tale plates that they were the victims of a gigantic hoax. Their Titanic labour had gone for naught. Some barbarian dog had salted the lighthouse; the pyramids of stone outside the battery were worthless. They held swift council and talked sanely until a terrified voice whispered that the barbarian's gunboat was heading for the Straits.

One by one they vanished into the darkness, each with a tiny parcel of gold strapped to his loin-cloth; one by one they disappeared into the scrub and kangaroo grass, until the silence of the gibber plains closed upon them.

The buccaneer slipped from his ham mock and stumbled across Sing Foo in the darkness. The Chinaman carried a bundle in his hand, and he gestured wearily at the silent army of coolies scattering towards the interior.

"They killee me, some day, when they catch um me," he cried bitterly. "Oh, why fo' you tell me that lighthouse was full of gold, Hayes?"

He departed towards the pier, hastily followed by his two shivering Tonquinese servants. The buccaneer watched them tumble into a big greasy sampan at the foot of the stairs. Five minutes later they were scudding across the bay under a stiff south-east wind in the direction of Tuan Island.

On the morning, when the gunboat Warrigal thrust her iron foot over the skyline, not a Chinaman was visible from Pera Head to the Batavia River. A squad of blue-jackets patrolled the town, while parties of Government black-trackers scoured the country, looking for the vanished horde of Mongolian lighthouse wreckers.

Captain Hayes, dressed in spotless white twill, escorted a young sub-lieutenant to the Skull Rock, and pointed out the track where the snake-army had carried every crumb of stone to the battery.

Three months later the Department of Navigation received a letter bearing the Honolulu postmark:

Gentlemen,

Your lighthouse tragedy at Skull Rock was a lesson in catastrophes that the ancient heroes and writers might well have studied. Caesar had his moments, Hannibal was a big- headed director of legions, but neither of these gentlemen ever blew out a light of so many thousand candle-power. It was an inspiration. It darkened the sea for miles; and the men who hold the maritime insurance money in tanks called you evil names—I regret my inability to spell the one I chose for you when your trooper ejected me from the White Marble. When next you are inclined to hurl your police in my direction remember there are nine other lighthouses between Rockhampton and Thursday, none of which are safe while a few pellets of gold and plenty of Chinamen are in the locality.

Bully Hayes.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.