RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"BULLY" HAYES was a notorious American-born "blackbirder" who flourished in the 1860 and 1870s, and was murdered in 1877. He arrived in Australia in 1857 as a ships' captain, where he began a career as a fraudster and opportunist. Bankrupted in Western Australia after a "long firm" fraud, he joined the gold rush to Otago, New Zealand. He seems to have married around four times without the formality of a divorce from any of his wives.

He was soon back in another ship, whose co-owner mysteriously vanished at sea, leaving Hayes sole owner; and he joined the "blackbirding" trade, where Pacific islanders were coerced, or bribed, and then shipped to the Queensland canefields as indentured labourers. After a number of wild escapades, and several arrests and imprisonments, he was shot and killed by ship's cook, Peter Radek.

So notorious was "Bully" Hayes, and so apt his nickname, (he was a big, violent, overbearing and brutal man) that Radek was not charged; he was indeed hailed a hero.

Dorrington wrote a number of amusing and entirely fictitious short stories about Hayes. Australian author Louis Becke, who sailed with Hayes, also wrote about him.

—Terry Walker

A DROGHER passed under the schooner's stern and manoeuvred

clumsily toward the mill jetty beyond the river bend. Captain

Hayes watched it and yawned wearily. The silence of the river and

the aching monotony of the shore line filled him with a mad

desire to up anchor and away.

He was awaiting a final message from the Northern Planters' Syndicate before continuing his trip to the islands in quest of Kanaka labourers for the cane fields. Like many other blackbirders, Hayes had learned to sleep with ah eye on the gunboats and water police whenever he found it necessary to lie at the mouth of a Queensland river. Of late years the man-hunting business had received cold support from the Government. The buccaneer had been warned that if caught while attempting to land un-indentured labour within a hundred miles of Australian territory he would be arrested.

Turning suddenly from the chart-room, he saw a boat shoot around the river bend in his direction. A bare headed man was rowing furiously, and, as he swung under the schooner's stern Hayes detected a scared look in his eyes. He was a lean sun-dried man, dressed in old dungaree, and a fireman's black flannel shirt. He stood up in the boat, resting his hand nervously against the schooner's side.

"Is Cap'n Hayes aboard?" he shouted. His voice had the querulous intonation of one who had been recently pursued by a troop of fiends. Hayes leaned over the rail elaborately, a look of suppressed interest in his eyes.

"Guess I'm your man," he said carelessly. "And I reckon by the drops of treacle in your boat that you're Jimmy Belcher, the mill-owner."

The sun-dried man gestured violently as he pointed with a black, sun-scalded finger up the river.

"I'm Belcher, worse luck," he began shrilly. "I'm in trouble with my kanakas. I came to ask you if—if—"

"Call in the troopers," snapped Hayes. Don't go round ask'n your neighbors to help you put down a twopenny insurrection. No decent man wants to fight the kanakas this weather."

"Listen, for God's sake, Cap'n Hayes!" Belcher in his agony clawed the schooner's side with his fingernails. "My black mill hands have mutinied. They broached a cask of rum this morning, and they've smashed up £200 worth of crushing machinery. There's a vendetta spreading throughout the plantations. I barely escaped with my life. My wife and children are barricaded in the homestead. The black devils have surrounded the mill and are threatening to fire it."

"Call in the troopers," repeated Hayes. " People don't hesitate when I start to smash things."

"They are away fighting the mutineer boys at Marana plantation twenty miles from here," cried Belcher. " I came to you. Hayes, because there isn't another white man within call. I don't mind the machinery being wrecked: it's the missus and kids I've got to fight for. If you won't help me—"he glanced at Hayes appealingly— "I'll have to see it out alone."

Seizing his oars he fell back into the boat and bent forward suddenly. A responding flash leapt into the buccaneer's eyes as the boat shot from the schooner.

"Ahoy, not so fast, there! You explain things trio suddenly, Mr. Belcher. Come under the rail with your blamed boat, and I'll climb down."

Slipping below, he appeared after a few moments with a pair of navy revolver bulging from his pockets.

"Must take the bull-pups," he said lightly; "they encourage civility. There's one man in Queensland who knows how to deal with the free-and-easy mill wrecker. His name is William Henry Hayes," he added grimly.

Once in the boat Hayes put a stiff back to his oar, and they were soon racing up the sluggish stream, leaving the schooner a couple of miles in their wake. The swift Queensland night closed on them without warning, wrapping bush and river in tropic, darkness. A curlew, waited beyond the distant ti-tree; here and there a fish leaped from the slow-moving stream as the rowers panted at their work. An intolerable stillness hung over the black readies where the mill stood, shut in by the close planted cocoa palms.

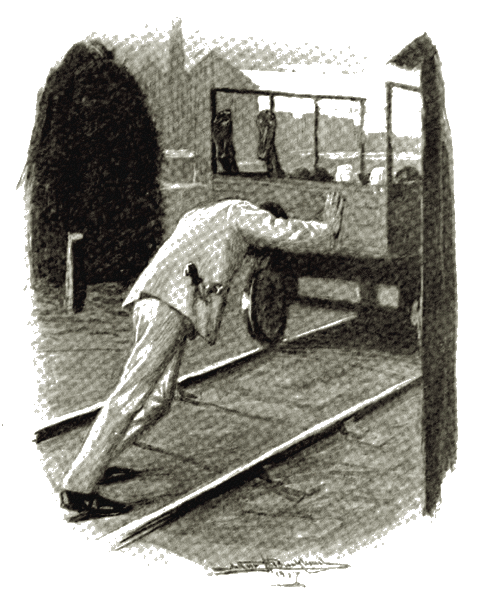

They were soon racing up the sluggish stream.

Turning the boat inshore Belcher made a swift gesture to his companion as they stole up the stone steps leading to the dark sugar mill. A dozen, grey-roofed outbuildings showed faintly through the tropic gloom, where the huge cane-stacks. lay ready for crushing. Entering the yard by a side gate, Belcher halted in the shadow of a cane-truck cautiously.

"There are twenty-five boys, all told," he said in a half- whisper. "They are armed with tomahawks and cane knives. It's the worst uprising among the kanakas since the Maryborough affair eight years ago. The islanders have been spoiling for a fight ever since they came here last month. It arose because I gave a job to an Erromango boy whose grandfather was the blood enemy of one of their tribe."

Hayes smiled grimly as he recalled many savage tribal feuds he had witnessed in the Marshall and Gilbert Islands. But the thought of the business in hand kept him silent.

A clammy heat swam through the night air. Swarms of tiger mosquitoes attacked them as they half-crouched in the shadow of the truck. The silence of the mill set Hayes thinking hard.

"The rum your kanakas broached this morning is getting in some fine work," he said after a while. "It's paralysed them, or else they're sleeping it off. Was it the usual poison, or merely treacle and dynamite?" he asked.

"The rum wasn't too pure," admitted the mill-owner. "Good enough for plantation kanakas, anyway."

Hayes knew the ways of the islanders as few white men ever hoped to. He had lived and traded with them for fifteen years, and he had. learned the value of prudence and dash when dealing with a blood vendetta.

A large cane-truck standing on rails in the centre of the yard attracted him. He regarded it for a few moments with undue curiosity, then turned inquiring to the mill owner:

"Is that cane truck empty?" he demanded.

"Quite. We haven't worked it for the last few days," answered Belcher under his breath. "Keep close to me, cap'n," he whispered, " Those kanakas of mine have eyes like telescopes."

The buccaneer made no reply as he edged near the truck cautiously. Belcher followed, keeping within arm's length of his companion. Hayes dropped on all fours suddenly and pointed to the truck.

"There's a pair of black feet hanging over the end," he growled. "I thought at first it might have been a couple of dead fowls or a bunch of bananas. "

"Feet!" gasped the mill-owner. "Surely you are mistaken, cap'n!"

"Guess I know a nigger's big toe from a ninepin," answered Hayes. That cane-truck is loaded with boys sleeping off the effects of rum. Providence has delivered the insurrectionaries into our keeping. If you've no objection, Mr. Belcher, I'll show you how to play a dry kanaka on to a wet wicket."

"We've no time to play cricket with mutineer kanakas," grumbled the mill-owner. "This is too serious a business for jokes, Cap'n Hayes. My property has been destroyed; the lives of my wife and children threatened."

The buccaneer laughed softly. "I'll bowl this sleeping crowd of mutineers. You shall be umpire. Now watch!"

Creeping stealthily toward the truck, he paused under the end wheels for several minutes, and withdrew a long iron pin that held the body of the truck to the frame-like support over the axles. Putting his shoulder against the end, he pushed until it moved noiselessly along the smooth iron rails. At each stride the truck increased in speed until he had to trot beside it to keep pace. The rails led to the mill pier that ran several yards into the river to allow droghers and small craft to land cane at the mill.

He pushed until it moved noiselessly along the smooth iron rails.

Immediately the fast-moving truck touched the pier Hayes slipped aside and matted. Two of the rum-sodden islanders sat up suddenly as they were borne riverward along the smooth, rails. There was a dazed look in their eyes—one big-jawed fellow, more sober than the rest, struggled to his feet with a savage cry of warning. He was a moment too late. The truck had reached the pier end, and crashed against the heavy cross-beam that spanned the rails. The truck tilted automatically, and emptied its human load into the deep, slow-moving river. Hayes waved the truck-pin in the air.

"How's that for out?" he shouted.

Smothered yells came from the river. One by one the heads of the half-frantic mutineers appeared on the dark surface of the stream, swimming in all directions, and cursing in their Polynesian dialect the man who had caught them so easily. Their leader, a muscular; long-bodied Erromango native, returned stealthily toward the pier. A cane-knife gripped in his right hand, he seemed to slice through the oily water as he swam with, powerful overarm strokes to the landing steps. Snatching an oar from the boat, Hayes leaped forward and brought it with a smash against the black, up-turned face.

Snatching an oar from the boat, Hayes brought it

with a smash against the black, up-turned face.

"Not this way, Johnny," he said cheerfully; "you call tomorrow and me lend you one piece of gas-tar to mend your face."

The uplifted cane-knife vanished in the stream; the long- bodied Kanaka rolled porpoise-like, screaming and holding his face.

"Now," said Hayes, addressing the amazed duster of heads in the water, " I'll gun the first man who shows his skin this side of the river. Savvy?" A chorus of savage invective followed this threat, but the sight of their leader swimming with blood-stained face for the opposite shore decided them. They followed, a dozen in number, trudgeoning with seal-like ease in his wake.

"They'll make for the scrub," said Belcher, or lie in the hills and play at bush-ranging until the mounted police and the black-trackers root them out. I wish the other lot—the big trasher gang—were with them."

"The big trasher gang! Great Scott! How many lots are there?" cried the buccaneer. "I guess you'll have to provide yourself with a war-balloon to deal with your little insurrection."

"Worst of it is, I don't know where the big gang is hiding."

The mill-owner turned sullenly from the pier and glanced back at the silent outbuilding in the distance. "They've destroyed the retorts and vats, and Lord knows whether they're biding, in the sheds or the palm-scrub at the back."

Stealing from shadow to shadow, with the fear of death in every limb, Belcher conducted the buccaneer to a six-roomed bungalow at the rear of the mill. The place was in darkness; windows and doors were barred and locked, and as the two men approached silently the sound of a child crying inside reached them.

"Fancy haying to lock up your wife and children all day!" cried the mill-owner, impatiently, "expecting to see a score of black devils chopping their way through the roof with machetes and tomahawks."

Belcher tapped at the door stealthily and gave a peculiar whistle. A bolt was withdrawn hurriedly; a woman's face peered out for a moment.

"All right, Kate," whispered the mill-owner. "I've brought a friend along."

Mrs. Belcher was a lady of Irish descent, with sun-tanned face and courageous eyes. During her husband's absence she had remained by the barred, window, rifle in hand, while her four children whimpered dismally in the dark passage.

During her husband's absence she had remained by the barred, window, rifle in hand.

"The black rascals have quietened down," she said cheerfully. "Sure we put in a whole day waitin' an' waitin' for the boys to come tearin' down the chimney or through the roof. But for the childer, 'twas meself that would have gone to thim an' conducted the mutiny in proper spirit."

Hayes shook hands with her warmly and patted the white-faced children encouragingly. "I'm glad to help you, ma'am," he said politely. "I've confabulated with junkmen and Malays in my day, but these kanakas of yours aren't fit to fight a squad of Chinese barbers. Don't worry, Ma'am," he said gently. "My patent ice- field is beginning to move, and it licks up things like an old- man torpedo."

After reconnoitring the scrub at the rear of the bungalow Hayes requested Mrs Belcher to retire in peace for the night. Returning to the mill yard, he approached a two-storied shed that stood at the end of the retort rooms. A huge square vat almost filled the centre. From its sides and bottom oozed a thick, black substance that stayed in sullen pools about the earth floor.

"My reserve stock of molasses," whispered the mill-owner. "Filthy staff to handle in the hot weather."

"Pretty big vat, isn't it?" Haves spoke under his breath, keeping well in the shadow of the half-open crate.

"I run it off into casks when ready for shipment," answered Belcher. " There's money in it, and—"

A livid flash lit up the shed; the terrific boom of a rifle followed. A bullet ripped the woodwork above Hayes' right shoulder.

"Good!" he said aloud. "I'll remember that, my lads."

Returning to the yard, followed by Belcher, he took up a position behind a stack of cane, his revolvers gleaming in the starlight.

"First nigger out will race a bullet " he shouted hoarsely. "Are you listening, boys?"

A series of yells followed from within the shed, followed by a guttural murmur as though the gang of cane-trashers were debating the situation. It occurred to Hayes that the majority of them were sober, arid had refused, even in their mutinous delirium, to partake of the fiery plantation-rum.

Another rifle shot followed; the bullet ripped the cane-stalks above Belcher's head. Then both men heard the gate of the shed close with a bang and the bolts' driven home inside.

"They're going to hold the fort," laughed Hayes. "That rifle of theirs will make it awkward for anyone crossing the yard day or night. Any provisions inside?"

"Only sugar and molasses. They'll soak into that until it sickens 'em."

"Um!" Hayes' stood up suddenly and seized a machete lying at the foot of the cane stack.

"Guess I don't feel inclined to sit here too much, Mr. Belcher. We'll shake them up, if you don't mind."

"Don't be a fool, Haves!" cried the mill-owner. "You can't face that gang of hyenas with a thing like that. They'll tear you to pieces."

"A thing like this!" The buccaneer swung the machete, sabre- like, with the skill of a guardsman. "If you allow those vermin to stay another day unchallenged, they'll be out at sun-up looting and murdering."

Ignoring the mill-owner's protest, he walked to the rear of the shed and discovered a flight of steps leading to a loft above.

Mounting stealthily, he opened the door and entered the loft. It was used as a store-room for the new bags fresh from the Indian jute mills. Slipping off his boots, he groped around until his hand touched the ring of a trap-door leading to the room below.

Haves was aware that the slightest sound would, alarm the big gang of cane-trashers beneath. Their deep voices broke upon him clearly, and as he listened he heard a slow-voiced islander outlining a plan to attack the bungalow at dawn, before the Queensland troopers arrived. They were too cunning to venture out in the dark, knowing from vast experience that a couple of white riflemen could pick them off from different points of the mill- yard.

Hayes appeared in no hurry to interrupt their plans. Chin in hand, he stretched himself on a pile of bags and waited until long after midnight. The guttural whispering ceased gradually; deep snoring told, him that sleep had overcome them, one by one. A wisp of moon showed in the east, casting a faint gleam of light across the shed.

Rising, he lifted the trap-door softly and peered below. Several blurred forms of grey and white loin-cloths indicated where the kanakas had flung themselves across the shed floor. They sprawled in different attitudes, some with knees drawn and hands stretched: others lay on their chests, their faces to the earth.

A ladder connected the loft with the ground floor. On his right and within arm's length stood, the big square vat of treacle. Descending the ladder, Hayes clung with both knees to the spokes and leaned over until the blade of the machete touched the long steel bolt that held the movable side of the vat in its place. The bolt slipped back noiselessly, allowing the hinged sides to open slowly as the weight of the molasses pressed out and down. With a heavy sighing sound the fifteen tons of black molasses broke in silent flood over the sleeping kanaka shapes.

Hayes leaned over until the blade of the machete touched the long steel bolt.

Hayes slipped back to the loft and waited. A muffled cry of agony reached him, followed by a series of gasping, choking sounds from the twenty stalwart islanders, caught in the relentless grip of the slow-moving treacle.

Hayes thrust his head through the trap-door suddenly, and lit a cigar.

"I guess that rifle of yours isn't going off again," he said genially. "Own up, like good boys, that it's a euchre party. I reckon if Britain and America knew the value of treacle as an offensive weapon they'd introduce it all big engagements. Gosh! it sticks, eh sonnies?"

The shouts of dismay subsided as the fear-stricken kanakas clawed and dragged themselves through the binding, viscous mass that clung to their knees and feet with glue-like tenacity.

Hayes sat on the ladder steps and spoke words of comfort and advice to the panting, clawing crowd below. Most of the islanders were struggling to regain an upright position; others sprawled in wrestling attitudes, striving to free themselves from the octopus-like grip of the treacle flood. A few lay on the floor of the shed, unable to rise—bound and helpless in the glutinous stream.

"I guess you boys don't hit a tide of molasses every day?" said Hayes sympathetically. " If there was a circus handy I'd bring in a few bears to lick it off."

The leader of the gang struggled to his feet, a dripping, treacle-covered rifle in his hand. He glared at the buccaneer seated on the ladder, and shook the useless weapon at him.

"Ahampes!" I keel you some day! Why for you not fight us proper?" he demanded.

"If you had hurt a woman or child in the district, answered Hayes, "I'd have tied the whole crowd of you to the plantation fence at sunrise. The blowflies would have done the rest of the fighting. Savvy?"

At dawn four mounted troopers appeared at the mill gates, accompanied by several black police armed with carbines. Hayes descended from the loft, and indicated the shed where the helpless kanakas were scraping each other with iron hoops.

"Guess you'll find 'em inside,' quiet as lambs, sergeant." he said briefly.

The sergeant looked puzzled, and turned to the white-faced mill-owner inquisitively. "Did they surrender after armed resistance?" he asked sternly. "We'll have to teach the brutes a lesson."

The buccaneer apologised for not being able to wait and see the guilty mill-wreckers escorted to the lock-up at Marana. He returned to the boat under the pier steps, accompanied by Belcher.

"Good-bye, Hayes," said the mill-owner, extending his hand gloomily. "This little mutiny will cost me a pretty penny. My machinery wrecked, my store of molasses run to waste."

The buccaneer regarded him fixedly though a cloud of cigar smoke.

"I reckon some men don't know how to spell thanks," he "Why, I burnt down a fifty thousand dollar store in Samoa last year because a fellow named Bill Harris called me liar, and hid himself in the roof."

"Did the store belong to you, cap'n?" Belcher asked meekly.

"Great Scott! No! I've got a sane spot somewhere."

Waving his hand to the mill owner Hayes pulled down the river towards the schooner.