RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"BULLY" HAYES was a notorious American-born "blackbirder" who flourished in the 1860 and 1870s, and was murdered in 1877. He arrived in Australia in 1857 as a ships' captain, where he began a career as a fraudster and opportunist. Bankrupted in Western Australia after a "long firm" fraud, he joined the gold rush to Otago, New Zealand. He seems to have married around four times without the formality of a divorce from any of his wives.

He was soon back in another ship, whose co-owner mysteriously vanished at sea, leaving Hayes sole owner; and he joined the "blackbirding" trade, where Pacific islanders were coerced, or bribed, and then shipped to the Queensland canefields as indentured labourers. After a number of wild escapades, and several arrests and imprisonments, he was shot and killed by ship's cook, Peter Radek.

So notorious was "Bully" Hayes, and so apt his nickname, (he was a big, violent, overbearing and brutal man) that Radek was not charged; he was indeed hailed a hero.

Dorrington wrote a number of amusing and entirely fictitious short stories about Hayes. Australian author Louis Becke, who sailed with Hayes, also wrote about him.

—Terry Walker

"I AIN'T complaining about him gettin' married," said the mate bitterly: "it's the way he's kept it to himself."

"He might have lost it if he hadn't," grinned the boatswain. "There are a lot of fifty thousand dollar men in the Marquesas who'd pawn schooner and trade to marry Varae Ulverstone. He'll quit the sea now."

"Him! The sea's his wife more'n any half-caste lady can ever be. I know Varae Ulverstone, an' I know Her!" He pointed across the wide bay of Tai-o-hai to the dazzling opal-tinted skyline. "Give up that! Yah!"

A cable of smoke trailed, marble-like, over the lip of the horizon, where an incoming tramp hammered her way through the reef-paved channels. A flock of sun-birds cheeped in the rigging over head. The buccaneer's newly-painted schooner lifted herself lazily, her full round hull adrip with the wash from the Hurricane Shoal.

"Neither of us invited, anyhow," broke in the boatswain dismally. "He might have asked me to drink the lady's health, seeing that him and me have shared the same bullets."

"Shared what bullets?" The mate eyed him coldly. "I've never seen you a-sittin' on the cap'n's gun. When did you take to bullets, might I ask?"

"Up in the Paumotos, last year." the boatswain responded from the hammock, somewhat loftily. "I was standing beside the cap'n when that German fellow Hueffer fired at him. The shot touched his left cheek, ricochetted, and hit me here." Turning up his sleeve, he exhibited a livid scar that ran from elbow to wrist. "It was Hayes's bullet all right; but he never would accept presents from the Germans."

"What 'appened to the Deutscher?" asked the mate slowly. "'E never fired again, I'll swear."

"Cap'n never touched him. He sold him a rotten schooner, though, about a month later—one of those weevily junks that you can stick your foot through. That's the proper way to deal with your enemies—sell 'em a rotten ship, and down they go, trade and all, first time they venture out of sight of land."

A boat was observed approaching swiftly. The figure of Captain Hayes was visible in the stern. Four kanakas bent over the oars chanting softly as they swept under the chains. Hayes stepped aboard briskly, his eyes aglow with health and good humour. He was point-device in his attire, with a touch of the Sydney dandy in his white silk coat and pipe-clayed deck shoes.

"Well, boys," he began lightly, "I've done it at last, and I hope it won't mar our brotherly relations."

"As if we 'ad a right to object every time our skipper gets married," responded the mate acidulously. "Not me."

"Every time, Bill! Do you want to accuse me of bigamy?"

"If it ain't bigamy, it's trigonometry or something. I never took the trouble to count 'em. My head gets mixed, especially at Christmas," said the mate hoarsely.

The buccaneer's eyes kindled strangely. "I've played 'Johnny Soft-Heart' with a lot of island girls, I'll admit; but never before at the altar steps, Mr. Howe."

The mate's kit hand wandered over his ear thoughtfully. "There used to be a big-shouldered girl named Lui the Pellews, an' every time we ran port—"

"I bought her a concertina," broke in Hayes hotly. "Perhaps you see a heap of harm in that, Mr. Howe. And what about Lui?"

"Oh, nothin', cap'n!"

"The concertina didn't interfere with your sleep, I hope?"

"I ain't complainin' about the noise she made, cap'n, or the flyin' machine that somebody built out of the concertina. It's a question of principle. I'm a family man myself, an' I know my responsibilities."

"Well, I hope I'll learn mine," cried the buccaneer heartily. "You're a good chap in your way, Bill; but you don't grasp the difference between a religious ceremony and a beach flirtation."

"I know what a concertina weddin' is," growled the mate. "Still," he appeared to brighten with great reluctance, "I hope the noo arrangements won't cause a fall in wages, cap'n."

"Or the rum allowance," ventured the boatswain respectfully. "It would be a bitter hardship during Christmas week, sir."

"So it would, my lads—so it would," agreed Hayes. "There will be no small economies practised on this schooner. Everything will go on as usual." He paused a moment, and felt his chin reflectively. "I shall be aboard early to-morrow. There's a bit of carpet in the sail-locker, Mr. Howe; you'd oblige me by hanging it on the state-room floor."

"An' a bit of buntin', cap'n." The mate glanced aloft at the schooner's snow-white yards admiringly. "There's a set of flags we got from that Peruvian slave-runner last year. They're extra bright an' tricky. Blamed if there's a white ensign or Jack aboard."

"The Peruvian rags will do," assented the buccaneer indulgently. His shrewd eyes wandered to the kanaka crew grouped in the fo'c'sle. "I guess you know how to sweeten a ship, Mr. Howe," he said pensively. "You might cover up that gun-tackle, and put those cutlasses out of sight. I don't want her to see such things."

"Aye, aye, sir. We'll sweeten ship afore you come aboard."

"There are twenty cases of shell to come before we get our anchor." He turned near the gangway, and looked back thoughtfully. "We'll have a pleasant run to Sydney, I hope; and there'll be no bickerings, my lads."

They watched him into the dinghy and across the sunlit waters, where the black terns and sea-hawks trailed and squawked beyond the tide-fretted bars. They leaned motionless against the rail until he disappeared within the wide-verandahed trade-house on the beach.

"Some people would feel sorry for the woman who's been joined to him," drawled the mate. "One day he's as husky as a blamed typhoon, next he's just a big, good-lookin' sailor-man.... Gettin' married ... of all things under the sun!"

"We'll hang a few pictures in her cabin," ventured the boatswain, "and then that bit of carpet, Mr. Howe, if you'll open the sail-locker."

The Catholic Mission boat swept across the bay; a white-coated padre waved his hand to the group of people standing on the trade-house verandah. Varae Ulverstone, the half-caste Marquesan girl, sat in the spacious room overlooking the wide bay. Her mother, a wrinkled giantess with elephant shoulders and hips, squatted among piles of silk and cotton trade.

The wedding was popular, for Captain William H. Hayes was known throughout the South Pacific as a man of good standing and an excellent trader, always ready to help a starving beach-comber or put a face on the small gangs of flash Harries who battened on the natives and made the lives of European residents unendurable.

A pulsing heat swam over the pandanus woods, scores of kites floated across the near jungle, throbbing the air with their bullet-like whistlings. There had been some kava drinking in the back rooms of the trade-house, and towards dusk a drunken headman rolled across the verandah, where the waiting islanders bore him triumphantly back to the village.

Varae's mother, with a side glance at the buccaneer, rose heavily from her mat. Pressing a handful of dollars upon her, by way of a parting gift, he escorted her to the verandah steps.

Varae sat still, her eyes downcast, her fingers playing with the silk sarong he had brought her from Celebes. Behind, in the shadow of some trade stuff, squatted the toothless Oke, her father's old man-servant, who had never lost sight of her since she had left school at Tai-o-hai, five years before.

Hayes returned and sat beside her, holding her hand tenderly. "See here, Varae," he began huskily: "I'm going to make a good husband. No funny business. Stick to me, and I'll play white man."

"I'm only a half-caste," she said wistfully.

"Better educated than me, though," laughed Hayes. "And I'm going to upset the little theory about half-caste women being half-child, half-devil. See!"

She looked up as though she did not understand his words; then, like a half-frightened child, she caught his hand and held it. Varae's father was a South Sea whaler, who had made his last voyage when she was playing with the mission-house children at Tai-o-hai. Her beauty was a theme amongst the pretty women of the Marquesas, and her friends predicted that she would some day marry a consul or well-to-do trader.

Like a half-frightened child, she caught his hand and held it.

Rumours of Captain Hayes's exploits had reached Varae in her island home. She knew that the sound of his name had a disturbing influence on the watchful gunboats that patrolled the lonely trading stations of the South Pacific. There were times when, woman-like, she pitied his hard and desperate life, his ceaseless wanderings over desolate expanses, through hurricane belts and uncharted groups, where death lurked on every lagoon, beach, and atoll.

Hayes had met her a few months before in a jungle clearing about a mile from the beach. At first her strange beauty had bewildered him—the creamy, sun-coloured skin, the mystic forest-fear in her eyes, that spoke of her Northern blood. Later, when they spoke to each other inside her mother's house, he discovered nothing of the tamed savage in Varae Ulverstone. Indeed, her refinement of manner, her knowledge of books and music made the white sea captain gape and wonder by turns.

She held his big hand, long after her mother had gone, as though it brought her immeasurable relief and comfort. "Dear ... I think I shall die for you some day," she half whispered.

"That's all right," laughed Hayes. "Only don't die oftener than you can help, little girl." He stepped to the trade-house verandah suddenly, and glanced at the schooner's riding light inside the bay. Something seemed to be moving beyond the house palisade. He heard his name called softly from the beach.

Hayes had no enemies at Tai-o-hai, but the sound of his name, coming through the tangle of lianas and ferns, aroused his curiosity.

Holding a warning finger towards his wife, he stepped lightly down the path to where a strip of moonlight revealed an old kanaka woman crouching beside an upturned canoe. She beckoned him to sit beside her. He recognised her as a woman of some authority in the village. She was a cousin of the head man, and had known Varae and her mother for years. He knew in a flash that she wished to speak about his wife.

"See here, Nabon." he said abruptly "I don't want to hear your tattle. Varae has been a good girl all her life, I swear. Can't you find something to do beside making people unhappy?"

The old eyes and the toothless mouth gaped at him in the eerie light. "It is for thy welfare and peace I came," she whispered. "I bear no hate to Varae. Her mother is my friend. It is of Lindman I wish to speak."

"Stop a bit, old lady." The buccaneer bent beside her with knitted brows. "Lindman's the fellow that shot Oke's son up in the Navigators some years ago?"

"He hath not stopped at killing men's sons," crooned the old woman; "for he hath run mad, since last year, in his ship, and the things he doeth maketh our heart sad."

"Guess I know the man's history, Nabon. Like Muldoon and Black Hervey, he's entered the wife-stealing business. Don't worry about my girl, Nabon. I reckon those men would pluck hot souls from the Pit rather than steal a wife of mine."

"Beware, O Captain... Lindman is swift. The hawk hath not a sharper claw nor eye. Listen...."

"Bah!" Hayes dropped a few dollars in her lap and returned to the trade-house. Varae met him with a questioning smile, but no word of what had passed escaped him. The South Pacific, as he knew, was alive with schooner-thieves and mauraders. Muldoon and Hervey had shot men on their own verandahs before absconding with their native wives and chattels. Lindman was a more accomplished blackguard, a man of taste and education. But the deeds of Hervey and Muldoon paled when compared with his recent exploits, his tricks of dress and speech when robbery and murder were in the planning.

The business of wife-stealing was fairly common in the islands, and was not confined to the natives alone; white men and traders suffered alike at the hands of Hervey and Lindman. European women had been kidnapped from their trade-house verandahs and carried to the uttermost atolls of Southern Polynesia. There was no redress. The visiting gun-boats were slow of foot, the kidnapping schooners swift as hawks. Lindman, with the uncharted solitudes at his disposal, held the skyline, so to speak, whenever his vessel darkened the white man's lagoon.

Captain Hayes rarely concerned himself with the affairs of these unwholesome desperadoes. He was essentially a man of business, extremely courteous to women, too hasty perhaps with his rifle when trade interests were threatened by German invaders. Nabon's warning fell flat. In his lion disdain he overlooked the small sea wolves yelping on his trail.

The sound of fishes leaping in the tide-glutted bay reached him through the still tropic night. Again and again he heard the sea wake to fling her robes of surf over the white hips of coral. Varae was more to him than life or trade; without her he would become a Vanderdecken, condemned to tramp the seas, childless and unloved, until fever or pestilence cast his bones upon some storm-washed atoll.

"Varae," he took her hand very gently, and turned her face to the dawn-whitened windows, "to-day begins our new life. Let us help each other."

They walked the beach, hand in hand, past the haunts of jargoning birds and sea fowl. Across the bay their white-breasted schooner flaunted her gala bunting, a familiar shape moved to and fro across the narrow poop.

There was much to be done that day.

The seaward side of the trade-house was littered with half- filled cases of shell awaiting shipment. Forty barrels of nut oil and several tons of copra still remained in the village, and Hayes was not the man to allow a single pound of copra to remain behind. Kissing Varae heartily he asked her to be ready to sail the moment he returned from the village.

He was not likely to be home before dusk. The chief would haggle over prices, and there were many presents to be distributed among his wife's relatives. Passing from the trade- house he walked briskly along the palm-skirted track that wound over a jungle-covered spur to the village nestling in the hollow beneath.

A light breeze thrashed the beach palms where the dingy sails of a copra tramp hung sullen against the blue. From her starboard side shot a yellow painted skiff, straight as a drawn line it came until its knife-blade keel cut into the beach-sand a cable's length from the trade-house windows. A man in a straw hat leaped ashore hurriedly, addressed a few words to the kanaka oarsmen, and stepped towards the trade-house verandah. The skiff returned leisurely to the narrow-hipped copra tramp in the fairway.

Oke, searching for a packet of nails inside the dark trade- room, turned at the crunching of feet on the gravel outside. Stooping forward he emitted a little choking noise that was heard by Varae, swinging in the hammock.

"It is Lindman, the woman-stealer! Take care, Varae, what thou doest!"

"Lindman!" The rest of the servant's warning escaped her. "Who is Lindman?" she asked, rising swiftly from the hammock. "I never heard of him."

He came quickly through the house-gate, looking to the right and left. The sea and his calling had invested him with a certain wolfish stare and a wolfish stride; his voice broke harsh and bitter, as one accustomed to shouting orders in hurricanes of wind and rain. He wore a crimson sash knotted over his left hip; his yellow beard, finely trimmed, proclaimed him an island dandy, a gentleman of mirrors and cheap perfumes. His slanting eyes fell upon the half-caste girl leaning over the trade-house verandah; he bowed, and his milk-white teeth showed against his sun-tanned skin.

"I have called at Tai-o-hai," he began in a suppressed voice, "on a visit to the daughter of my old friend, Captain Ulverstone, of the whaling ship Thrasher.

"I am the daughter of Captain Ulverstone." Varae met his swift glance unflinchingly. "Anyone who was my father's friend will be welcome in the Marquesas," she went on. "I am sorry that you have missed my husband. If you will come inside—"

She hesitated at sound of Oke's deep breathing behind her. "If you will come inside," she faltered again.

"I should appreciate an hour with your husband," he said, without moving, "but the fact is I am due at Nukahiva almost immediately. The vessel which I have the honour to command," he pointed to the swart, hammer-nosed schooner in the fairway, "was once the property of your father. In those days she was known as the Mary Holland.

"My friends often speak of the Mary Holland." A faint flush stole into Varae's cheeks. "She earned my father all the money he afterwards lost in the South Seas."

"She is still a first-rate vessel." Lindman's eyes glowed with enthusiasm. "A month ago, in the Navigators, she was overhauled for repairs, and the workmen came upon a picture of Captain Ulverstone in the stateroom, painted on a rosewood panel above the old mahogany sideboard."

"I never heard of the picture!" cried Varae. "Are you sure it is my father?"

The kidnapper smiled forgivingly. "It was painted by a Sydney artist many years ago—the date is underneath. If you would care to accept it," he said warmly, "it is yours for the asking."

Like most half-caste women Varae was very proud of her white descent. Her one regret, since the death of her father, lay in the fact that no portrait of him was in her possession. Her heart leaped for a moment at the generous offer, but Lindman interrupted her thanks with unblushing haste.

"There will be some difficulty in cutting it from the rosewood panel," he said. "These ships' carpenters are not accustomed to handling fine art furniture. A cut in the wrong direction, a splintered grain, would certainly destroy the panel," he said thoughtfully.

"Oh! please don't let them destroy it!" cried Varae eagerly. "I would never forgive myself, or you," she broke out.

Lindman stood on the seaward side of the trade-house, leaning against an empty shell-case. It would have been impossible for anyone approaching from the village to have observed him. His unfaltering repose, his spotless attire, gave him the air of a prosperous trader. He eyed her for a moment, and the wolf-stare deepened at sight of the cream-white throat, the supple lines that seemed to flow beneath her pretty, wide-sleeved coat. The wolf-stare changed to a smile.

"If you care the bring one of your servants we might go aboard now," he ventured carelessly. "One of your boats will carry us."

His glance fell upon a newly-painted dinghy at the foot of the steps. "You might then advise me about the picture's removal. These ships' carpenters are terribly careless."

"My husband would like me to have the picture, I feel sure," answered Varae. "I will go aboard with pleasure; Oke, my old servant, will take us in the dinghy."

Lindman nodded approvingly, and in the fall of an eye took in the trade-house and its luxurious surroundings. "Your husband is a German trader, I presume?" he ventured after a while.

Varae laughed as she descended the verandah steps to the dinghy. "My husband's name is William Henry Hayes. I am certain you have heard of him," she added a trifle mischievously.

"Hayes!" The kidnapper's pose vanished; his lips grew ashen through the rift in his golden beard. Instinct, strong as life, screamed at him to be gone. The fame of Varae Ulverstone's beauty had reached him in the Paumotos. He had learned something of her life's history before venturing into Tai-o-hai, but, in his savage haste to reach her, had omitted to inquire the name of her fiance.

He turned the moment her feet touched the soft white sand beside him, and his throat grew strangely dry. "Of course, I know your husband," he said thickly. "His name is as well known as Bismarck's in these islands.... The dinghy," he added brokenly. "Where are the oars?"

There were no oars in the boat. The kidnapper breathed a trifle desperately, felt the sapphire dome of the sky turn to a blood-mist in the heart-shaking moments of suspense. A sudden pattering of feet on the gravel outside aroused him. One of the house-servants ran in, gesticulating frantically:

"The master is returning, Varae! He has forgotten the cash to pay for the oil and trade."

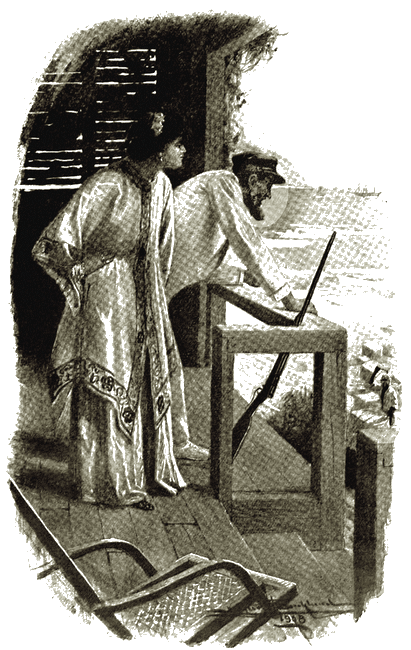

The figure of Captain Hayes was clearly visible as he descended the jungle-track leading to the trade-house.

He whistled as he came, his rifle sloping from his left arm.

Lindman had not dreamt of meeting the buccaneer at Tai-o- hai.

A sudden dog-like fear bleached his lips and eyes. Any other man but Hayes, and his presence might be explained.

"What unspeakable chance ..."

The fear that licked him white left no doubt in his mind where Hayes' bullet would strike—between the eyes, or full on his sunburnt throat.

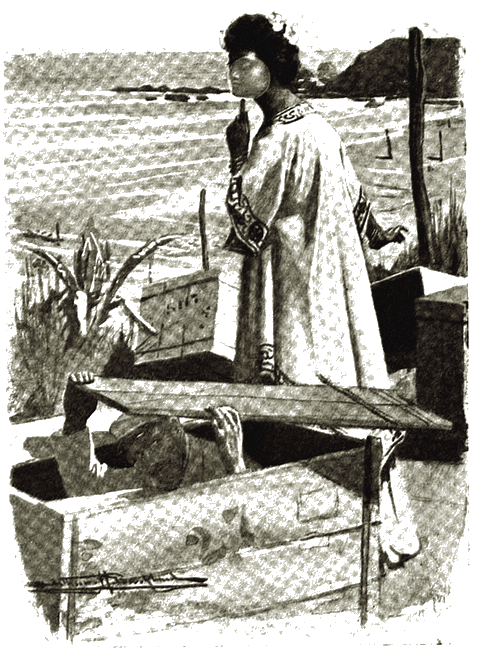

He glanced wildly at Varae, and then his eyes rested on an empty shell-case near the beach. Part of the lid was removed and lay beside it. The buccaneer's footsteps were plainly heard fifty yards away on the lee-side of the trade-house.

He turned to Varae, gesturing in his soulless panic: "Your husband may not understand the peaceful nature of my visit. There is an old sore between us. Give me this opportunity of avoiding murder."

Before Varae could cry out against the act, he had crawled into the empty shell-case, and with lightning fingers had drawn the lid over the top. Scarce daring to breathe, he felt certain that the buccaneer would proceed to the village the moment the forgotten cash was in his hands.

He had crawled into the empty shell-case, and with

lightning fingers had drawn the lid over the top.

The old kanaka, Oke, was at Varae's side in a flash. "Speak no word to the master," he whispered, "or murder will come of it. Peace; he will soon be gone."

Captain Hayes approached nimbly, and for one moment his shadow loomed Titanesque before his half-caste wife, his rifle balanced in his left hand. Something electrical charged the still, hot air; the very silence seemed to wait the inevitable impact of conflicting forces. The buccaneer halted, placed his rifle in a corner of the verandah, and laughed a little irritably. "Forgot the dollars, my girl," he said to Varae.

He stood for a moment in the hot sunlight, and his brooding glance went across the bay to the dark-hulled schooner in the fairway. A tiny frown creased his brow. "Some ships have the cut of gaol-birds." he said reflectively.

Entering the big trade-room he unlocked the safe and drew out a bundle of bank-notes hurriedly; then peeping from the door beckoned his wife genially. "Now, Varae, a run over to the village will brighten you a bit. While you are there you can pay old Gorai for the oil and sandalwood. Tell him I'm busy to- day."

She made no immediate reply, but Stood for a moment shaken between doubt and fear as Oke took up a hammer and began deliberately nailing down the lid of the shell-case that held the quailing Lindman.

Hayes followed her glance, then leaned across the verandah rail. "What are you doing, Oke?" he demanded sharply. "Didn't I ask you to pack Varae's luggage this morning?"

Hayes followed her glance, then leaned across the

verandah rail. "What are you doing, Oke?" he cried.

The old kanaka paused to rub his nose with the hammer handle. "Me plenty do, Cap'n. Me pack Missy Varae's tings one two hour ago." With a loud grunt he drove the last nail into the lid of the shell-case.

Varae almost ran to the village, scarce daring to halt or glance behind lest the sound of her husband's rifle might speak of Lindman's discovery. A dozen times on her way she told herself that Oke had risked his life to shield her visitor. The shell- case would be taken aboard the schooner that night and in the darkness Lindman would be liberated. It was unfortunate, he thought, that an old friend of her father's should be her husband's enemy.

It was quite dark when she returned from the village. A lamp burned in her husband's room; she paused a moment, before ascending the verandah steps, to watch his shadow moving across the blinds. He was in his shirtsleeves beside some scattered trade stuff when she entered the room.

"Your people kept you," he said cheerfully. "Now... you'd better help me straighten up this unholy litter, and we'll get aboard the schooner."

A dozen riding lights blinked from odd corners of the bay when they wore from their moorings. The schooner headed seaward before a strong southeast wind, while a soft, chanting chorus came from the fo'c's'le:

"The sea is deep; the sea is wide;

But this I'll prove whate'er betide:

I'm bully in the alley!

I'm bull-ee in our al-lee!

Varae walked aft while Captain Hayes stooped near the open

hatch, a hurricane-lamp at his side. "One case of shell missing!"

He turned impatiently to Oke. "Where have you stowed it, old

man?" he demanded.

Oke glanced swiftly at Varae and then at the buccaneer. "Nineteen case come aboard, Cap'n," he began in a quavering voice.

"Twenty in the manifest!" growled Hayes. A look of anger crossed his eyes. "The odd case will have to be accounted for. Speak out, man!"

Oke held up both hands suddenly, like one guilty of a secret crime. "There was a little accident, Cap'n," he said in a thick voice. "Tamito, the Erromango boy, packed the cases all too high in the whale-boat. There was one case much lighter than the others, which he put on top. When we rowed out we catch one big swell under the schooner's side, and the case on the top slide over into the water. No fault ob mine, O Cap'n."

Later the old kanaka moved across the hatch and stood by Varae, fumbling awkwardly with a tangled bowline.

"Oke, why didst thou?" she whispered, "and he a stranger to thee and me."

"He was no stranger to me, Varae," muttered the old man. "Lindman shot my son many years ago when his ship came to the island to steal our men for the Peruvian mines. See!" He pointed to where Lindman's dark-hulled vessel still waited in the fairway. "His ship will wait and wait, but the slave-master will never come aboard, Varae—never! never!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.