RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library.

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

LONDON!

The name has a bell-like sound for many people. To others it is a bugle-note calling eternally across the five oceans: I have heard it in the solitudes of the Diamantina valley; it has walked beside me in the camping grounds of the Gulf when fever and loneliness stalked from the mangrove skirted inlets and ti-tree swamps.

In eight years we had saved enough money to answer the call, eight years of economical strife with a big clanking leg-chain on our little ambitions, and the day came. One man advised us to travel via Valparaiso and over the Chilian Andes into Argentina. Australians and New Zealanders, he said, wanted to hear something about the chilled beef question, the pastoral and mining outlook of the prosperous Republic.

Now the Chilian Andes are very well in their way, and one doesn't mind all occasional condor for breakfast, but the average Australian jibes at the Newcastle-Valparaiso-Shanghai route where the opium-dosed crimp-house men are occasionally shovelled into the bunkers with the coal. So one had to discard the Argentina route and scan the map anew.

The Port Arthur-Manchurian trip, via Moscow and St. Petersburg, looked inviting, especially when we all remembered Lio Yang and Mukden, and the tremendous Russian and Japanese armies that hurled themselves and the toilers' money at each other for many months. We thought that Mukden would be a nice place to see. We longed to hear about the 12-inch shells that used to whizz through the refreshment room every time General Kuropatkin came up for a basin of bear broth.

We had almost decided on the Port Arthur journey until a Chinaman told us that the North Pole is a cheerful, well- ventilated suburb in comparison with Harbin and the Trans- Siberian railway during the winter months. John inquired casually if I had ever worn a wolf-skin coat padded with rubber to keep the wind from shaving itself against our shoulder-blades. I smiled and postponed the Trans-Siberian holiday indefinitely.

After driving many innocent sheep from one end of Australia to the other, I did not feel inclined to start a fashion in wolf- skin coats. A climate that permits of an occasional calfskin vest or pyjamas at midday is more to my liking. I advise the Moscow Tourist Bureau to leave out all mention of wolf-skins when catering for Australian patronage.

Finally, we decided that the Red Sea route, with its blinding sandstorms and mirage-haunted deserts was better than a packet of snowstorms, especially when we heard that the authorities at Naples provided volcanoes in their scenery. A gentleman who has travelled extensively, told me that volcanoes are splendid things for keeping away mosquitoes.

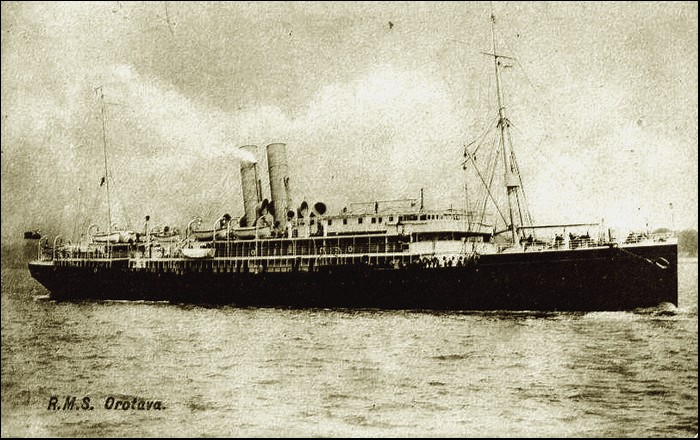

The Orotava.

A COOL breeze was blowing over Sydney on the morning of departure. Only a week before we had been lighting bush fires on our boundary fence. Now everything was changed. No more greenhide-beaters; no more sap-scalds! We were bound for England where the grass won't burn even if you spray it with kerosene in midsummer. It's a grand thing to picnic in a country where people can throw matches at one another without setting their best girl's paddock ablaze.

Sydney is a well-to-do place. It wears a gorgeous crown of red tiles on its foreshores. It is a city of iced drinks and time- payment motor launches. The people certainly appear more comfortable than the back-country dwellers. The men hold up the skirts of their waterproofs when it rains, and the women look upon 12-guinea gramophones with splendid indifference.

Arriving at the Circular Quay we beheld the outlines of the vessel that was to carry us north. Her huge stern almost bulged over the footwalk; her yellow funnels towered above the adjacent six-storey buildings. The Quay was crowded. Bush and city people thronged the Orotava's decks. Here and there a sun-tanned couple from the back-blocks caught one's eye, joy in their hearts and a ticket to London in their purses.

Near the funnel-stays was a woman from Coonamble; her five stalwart children around her, bush-scarred, sun-bitten, hardy as brumbies. Their father had sold his share in a mine, and they were off to join him in England.

The steamer's street-like decks dwarfed everything. Aboard an ordinary coastal steamer a small man may preserve his dignity. But once on the deck of a modern liner, a six-foot man becomes a midget; his height is bossed by the giant funnel-stacks, and his friends have to pick him out with binoculars or by the colour of his hair. The decks of our departing ship would have borne the fleet of little vessels which accompanied Columbus across the Atlantic. The Almiranta and Capitano, that brought De Torres and Pedro de Quiros to the Australian seaboard 300 years ago, could have been stowed comfortably in our fore and after holds. Yet, if circumstances had permitted, I would gladly have thrown my belongings aboard an 80-ton fore-and-aft rigged schooner moored almost alongside. There was romance and mystery about her rakish top-hamper. Her smoky galley and newly-painted deck-house, with the broken shell-cases lying near the alleyway, suggested island trading. A kanaka cook peeped from the cuddy. It is not good to look twice upon an Island bound schooner when London calls.

A couple of travelling bushmen leaned over the Orotava's rail and gazed steadily at the oily waters of Sydney Cove. Hitherto the Murrumbidgee was the finest strip of water they had ever seen, and they spoke earnestly concerning the height and power of deep-sea waves. One of them, a married man evidently, was of opinion that the sea froth would climb over the rail and moisten the baby.

Never saw so many babies on a ship! There were three in our cabin—put there by mistake—and a couple at the foot of the stairs playing with the steward's parrot. Some of the first saloon babies were travelling with professional nurses. At sea the professional nurse is supposed to restrain and hammerlock her small charges whenever they attempt to swallow the ship's brass-work or man the lifeboats.

While hundreds of grown-up people were saying good-bye on deck, the little ones were introducing themselves to each other below. It grieved one to see so many fine babies rushing from Australia—even for a brief space.

In the steerage and saloon were several gold-miners from Queensland—"bound for a spell on the wet," as they termed it. There are certain people from Maoriland and Tasmania who regard a yearly trip to London as the cheapest way of spending a holiday. It the third-class were plenty of well-to-do wheat farmers and small settlers, anxious to get away from the eternal grind of selection life after the recent good seasons.

"We mightn't get another chance," laughed a North Coast man. "Three years back I was burnt out, and barely escaped with the wife and children. I think we managed to save a horse rug to cover ourselves with. To-day I'm off to London, and I'm going to have a time. Did I bring the wife? My word I did. She's travelling second saloon with the youngsters. Eh? oh, the steerage is good enough for a wayback like me. It's time the old girl enjoyed herself."

We had a great send-off. It seemed as though the whole of New South Wales had come to see the last of their relations. Even the policeman waved his hand as the big vessel left the wharf. Suddenly, a wire-haired man was observed tearing along the wharf waving a strip of blue paper in the air.

"Is there anyone named M'Guinness aboard?" he shouted, "There's thirty-nine weeks' rent owing!"

Everyone on the steamer glanced at his neighbour suspiciously, but it is terribly difficult to tell a man's name by the shape of his hat. No one had seen or heard of M'Guinness. The ship's officers were certain that M'Guinness was not aboard, nor any hardened person capable of owing thirty-nine weeks' rent.

It takes a lot of big machinery and big deck fittings to surprise Australians and Maorilanders. Adjoining our cabin was a Wilcannia man, who had never seen anything bigger than a fish punt or a corduroy bridge. Yet in less than twenty-four hours he was intimate with the mysterious workings of a 6,000-ton steamer. The day after leaving Sydney he explained to me the difference between a slovenly banked fire and a properly-sliced camel-back. He held forth enthusiastically of the ways of deep-sea ships, of patent man-killing, fire draughts, and bunker space. He spoke learnedly of the difference between Bulli and Newcastle coal, how to use a slice-bar, and how to hit a Lascar under the chin with a shovel when he runs amok in the hot weather.

The head and eye of that Wilcannia sheep-breeder impressed us considerably. If young James Cornstalk is typical of this kind, I feel sure that Australia will have small difficulty in manning her own fleet when the day arrives. People tell us that we don't take to the sea. Personally, I have learned more in ten minutes from a fifteen-year-old Australian boy anent the workings of a big ship than it was possible to acquire by months of hard reading.

The South Coast of New South Wales is bleak and mountainous. Vast tracts of spotted gum forests and treeless ridges face the long Pacific swell. Here and there a chrome-coloured promontory stretches its sea-washed tip into the thunderous surf. Innumerable gull-haunted islets crowd under our bows; geese-like mollyhawks and shags trail inshore to where the sea frets and whitens under the frowning cliffs.

"It is always raining in the South Coast hills," said a Bega man. "I've known it to spill down for months, until the wild scrub cattle were fairly driven into the homestead paddocks. Funny," he went on, "how hard rain will tame old mountain bulls and brumbies. I've seen wild-eyed outlaws tramp in and stand shivering under the sheds after a long spell of cold, wet weather. You see, the wild life has not entirely eradicated the stable instinct in them. You couldn't get within miles of them in fine weather. Yes, and I'll tell you how heavy rain affects the blacks one of these days."

THROUGH the morning mist we could clearly make out the sullen heads of Twofold Bay, with Mount Imlay in the background wearing it's morning beard of cloud.

Whaling is still carried out at East Boyd, a picturesque little place on the southern shores of the bay. From October till the end of November whale-hunting goes on merrily under the management of Captain George Davidson, an up-to-date sportsman who has accounted for 96 black whales in his brief span.

Humpbacked cetaceans are plentiful enough during October and November, but the lack of bone in their huge carcasses makes them hardly worth catching. A full-grown black whale is worth in bone and oil anything up to £300 and often more. A dozen aboriginals and half-castes are employed at the trying-out works, East Boyd. The blackfellows make excellent harpooners and boat steerers, and will venture out in the wildest weather on the chance of putting an iron into a stray cetacean.

The killers, a porpoise-like toothed whale, hunt their big relative in packs and work like sheep dogs the moment a whale heaves in sight. Without their assistance the trapping of the huge mammals would be impossible. They scour the open Pacific for miles around Twofold Bay until their quarry is sighted. Forming themselves into a half-circle they fairly heel the monsters through the heads snapping and tearing at the soft white fat around the whale's heart and head.

And the whale is a one-hit fighter. He rams and trudgeons through the squadron of killers, trumpeting with fear and flogging the sea with his great fluke. The killers are too cunning to be caught by the whirling mass of bone and flesh. They confine their attacks to the head and mouth, and it is on record that a big killer once tore out the heart of a sixty-ton black whale before the boat and harpooners arrived on the scene.

Some years ago a rival firm of whalers started operations at Twofold Bay. They invested a lot of capital in up-to-date appliances, boats, bomb-spears, harpoons, etc., and after erecting a trying-out works they began looking for whales.

During the season experienced look-out men are stationed along the coast. It is their business to send up smoke-signals the moment a whale is sighted. It frequently happened that the rival harpooners appeared within striking distance of the monster at the same moment. Quarrels as to the right of ownership were inevitable.

Stories are rife in Eden concerning the Homeric conflicts which happened daily over the floating bodies of dead whales. One party claimed the right to seize and cut up any black or humpbacked whale which came into tho bay. The rival firm were of opinion that the whale became their property the moment their harpoon stuck fast in the carcass.

The struggle for supremacy lasted a couple of seasons until a rough whaler's code was drawn up and was agreed to by both parties. Herewith a rough copy of agreement signed by the rival firms:

'First harpooner on the scene to put in his iron and hang on. If the whale dies it becomes their sole property. If, however, the whale breaks away, No. 2 party is at liberty to harpoon at leisure, the whale to become their property if a kill is proclaimed.'

It was soon discovered that the second party on the scene always took the whale, seeing that in nine cases out of ten a full-grown oetacean does not succumb to the first harpoon. More complications ensued, more bitterness, and midnight sea- scrimmages that remain unrecorded in the annals of Australian whaling.

A boy humourist appeared suddenly in the district, who proceeded to elevate the Australian whaling business into the regions of comedy. He hailed from Maoriland, and he seized the situation with both hands and painted it white. Only a boy would have ventured to play the game on a crowd of half-castes and hard-hitting Yankees.

One wet, stormy night the rival stations were aroused by the cries of 'Whale-oh!' 'Blow-w-w-w!'

The seas were running mountains high, but the crews turned out of their huts and tumbled into the boats on discovering that half a dozen fire signals were flaring along the coast. Pulling cheerfully towards the Heads the rival crews fouled repeatedly in the blinding darkness, after mistaking each other for the hump of a whale.

Dawn found them wet and shivering with cold. And there was no sign of whale within the bay or on the skyline.

'Who lit that blamed fire?' demanded a sour-visaged boat- steerer. 'Guess I'll put a harpoon into the feet of the man who made that fire on the South Head.'

No one knew who lit the fires, and the whalers returned to their stations hoping to trap the miscreant who had 'pulled' them from their beds to face a semi-Arctic night.

At sun-up a bright, fair-haired boy was observed strolling book in hand along the cliffs. He was accosted immediately by a wild-eyed blubber-soaked 'cutter-up.'

'Hev you seen a whale, sonny?'

'No, sir, I have not seen a whale.'

'Did yew light up the bush any time, whatsomever, sonny, thinkin' you might befool Bill Greig an' them lads of his?'

'No sir, I have been taught not to play with fire.'

'What's thet book you're readin', sonny?'

'It's a book on fowls, sir. It tells you how to raise Plymouth Rocks on a three-acre block. I showed it to a man early this morning. He asked me if I knew how to raise a crew of lazy whalers.'

'Where did yew see that man, sonny?'

'Down the coast, sir, collecting dead timber to build a fire to-night.'

Half-an-hour later a crowd of angry whalers were seen hurrying along the coast armed with bomb-spears and lances. Nothing happened except a series of wind-blown fires along the coast the following night. The whalers stayed in bed.

At daybreak a 50-ton, killer-driven right whale was discovered stranded on the rocks near East Boyd, surrounded by swarms of voracious blue-pointer sharks. It was impossible to tow the IOUs from the dangerous shoals, and the men at trying-out wept at seeing £200 worth of bone and oil being stripped and borne away before their eyes.

Afterwards the business of whaling became so precarious that the new firm closed down and sold their outfit for a song, partly on account of the Will-o'-the-wisp fires caused by a small, wandering schoolboy.

As the big steamer wore towards the Victorian coast the giant headlands and forest-clad hills recalled the doings of Australia's long-lost pioneer and cattleman, Ben Boyd.

Somewhere in the forties Ben took up vast tracks of land in and around Twofold Bay. His energy was remarkable. After erecting a whaling station, and housing half-a-dozen crews, he began cattle-rearing on a large scale. Later, he planned the site of a city where Eden now stands, and ran his immense herds around Mount Imlay and Pambula Creek.

He experienced difficulties in marketing his store mobs owing to the almost impassable nature of the country. At last he disappeared mysteriously in an island-bound schooner and was never again heard of. The bulk of his vast herds remained for a long time in the district of Twofold Bay, neglected and unbranded.

Two years after Ben's departure the gold rush in Victoria sent up the price of beef. Crowds of adventurous drovers and cow- duffers swarmed over the Monaro country, rounding up and branding the ownerless scrub bulls and gully-duikers that wandered over the forest-screened hills.

In those days there was no particular demand for way-bills and stock-receipts; the gold-fields were meat-hungry, and Ben Boyd's cattle were shepherded by devious ways into Ballarat and Melbourne. His whales were left to take care of themselves.

From Wollongong to Cape Howe the coast of Australia has a long-dead, petrified appearance when viewed from the deck of a steamer. There are no wide river-deltas or luxuriant palm-clad inlets that one meets north of the Great Barrier. Vast uninhabited spaces fill the geographical bill.

THE life of a deep-sea steward is crammed with incident—and tips. I noticed that the young gentleman who looked after our cabin wore a lint bandage in the palm of his right hand. Asked whether he had been bitten by a land agent or octopus, he replied somewhat huskily:

"Some of the gents what come aboard like their money's worth," he said, after a while. "An old toff named Bullaman 'ad me runnin' all over the ship last trip. He was a holy terror for 'ot water an' lemons. I wore out three pairs of sneakers tearin' up an' down stairs for him.

"He'd plenty of money; an' I was told by the chief to see that the gangway was 'all clear' when he left us at Sydney.

"He looked a good mark for a big tip, an' the chief cautioned me not to hold out me 'and too far for fear of offendin' his eyesight. Young stooards have a bad habit of lettin' their 'ands 'ang over the ship's side when the passengers are goin' off.

"After carryin' Bullaman's luggage ashore, I waited respectfully on the gangway with 'ardly three inches of me 'and showing on the skyline.

"Down came Bullaman, breathin' like a cheap Panhard, an' winkln' at the ladies. I noticed that his eye was fixed on me 'and.

"'Ho, yes,' he says, pullin' up. 'Ho, yes, stoored; I'd halmost forgot you.'

"He was holdin' a 'andkerchief in his hand. There was a tin snuff-box wrapped in it; an' when he stopped he opened it like lightin', an' spilled five 'arf-crowns into me 'and I nearly jumped off the gangway.

"Everyone of 'em was red 'ot. The skin of me palm curled up an' blistered when I gripped 'em. Yer see, it's against human instinct to drop money, especially when yer liable to drop it into deep water. There was nothin' to do but dance up the gangway, an' blow on me 'and.

"That's how I come to be wearin' lint on me list, sir. I hope you ain't keepin' a few 'ot uns for me when you go ashore, sir?"

I explained briefly that my tips were given cold, and that my money was always kept on the ice-chest the night before going ashore. The steward looked pleased; and after receiving a cold half-sovereign for seeing me through, his hand grew rapidly better.

Bill Simmons is my cabin mate. He is going to Colombo to fill a position on one of Lipton's tea plantations. Bill is a handy man and has worked at most outback trades. For three years he managed a South Coast butter factory with some success. Then he became a shearing contractor, agitator, and boundary-rider. He was brace man at the Day Dawn mine, Charters Towers, and was dismissed for inciting his fellow-workmen to wake and arise during the strike.

The sick and the strong are much in evidence to-day. The women look up as you pass with dull, unseeing eyes. Some of the men are worse. When a man is rally sick, only his heels are visible. Saw several feet this morning belong to my friends sticking out of odd corners—rope coils and tarpaulin sheets. The women sprawl in their deck chairs; the men burrow.

The wind from Bass Straits cut like a knife. Time: Middle of March, and the Sydneyites abroad walk shivering about the deck. Five or six years spent in a steaming sub-tropical city has its effects; and the native of Surry Hills or Mosman turns blue at the first breath from the southern icebergs.

Melbourne at last. Slowly we steam up the weary expanse of bay. An occasional sand-hump bulges on the skyline. Not a tree or a scrap of foliage anywhere. Later we discover a horizon thick with furnace stacks and gasometers. A streamer of wine-red cloud covers the east. A black barge with black sails stands silhouetted against the dawn. Far away in the low flat north lies Melbourne, wearing a halo of wind-driven dust.

The approaches to Melbourne would scare away a modern pirate or an invading force of aesthetic Japs. The eye wanders towards the dreary sandhills and the seedy vessels huddled at the pier- end.

One's first impression of Melbourne is favourable and lasting. East and west, north and south, the city flings out her broad, straight roads. It is a place where men may walk fifteen abreast on the footpaths, instead of tripping on each other's heels as in Sydney. In comparison with Melbourne, Sydney is merely a bye- way—when one recalls its notorious traffic-traps and pinched exits. Sydneyites take their municipal fathers seriously instead of presenting them with all annual funeral under the trams.

Sydney sprawls with mediaeval futility around the coves of its beautiful harbour. Melbourne has gripped her desert site with both hands, and rendered it habitable. Her incomparable streets are strewn with grass plots and shady trees.

Melbourne men are better looking than the Sydney chaps. Sydney breeds a shamble-footed citizen, who crowds the gutters for want of footpath space. He grows bottle-shouldered through falling off the kerb and dodging trams. Some difference, too, in the gait of a Melbourne crowd.

While in Sydney I found myself rushing past the average pedestrian. In Melbourne the order was reversed; men, boys, and women streamed past me without effort. The present generation of Melbourneites is the result of a brisk, dry, healthy climate, free from humid ocean vapours that enervate dwellers around Port Jackson.

I left Melbourne with regret, and hurried back to the steamer in time to see a procession of Mahomnmedans climbing aboard. They had come from the West on a holiday tour and were returning to Kalgoorlie and Leonora to join their camel teams and fulfil fresh contracts. The gold-field Afghan is a lean-visaged fellow, with quick, shifty eyes, and grasping hands.

Opinions differ among Westralians regarding his citizen-like qualities. I have met Kalgoorlie men who declare that Mahomet Ali is a good fellow to meet when things are bad and the plains are gibbering from east to west.

One well-known miner said that he had tried a dozen Afghan camps for flour and water during a famish, and had never been refused hospitality.

Others tell strange stories of an Afghan's blackguardianisms during the rush to Coolgardie some years ago. How he polluted soaks and bailed up fever-stricken travellers, until several white miners retaliated by shooting the lean and husky camel-man at sight.

We slipped our cable from Port Melbourne pier at noon. A great crowd assembled to "see off" a young prizefighter bound for Perth, who intends wresting the championship from the Goldfields Chicken during Easter week. The young pugilist travelled second saloon, and towards evening asked permission to work with the stokers.

"Shovellin' keeps me in good nick," he said to the chief engineer pathetically. "The fires open me pores better than a runnin' track."

The engineer replied that he could not allow him to wield a slice-bar, but he had no objection to young Achilles warming his pores at the fires.

That night Achilles came on deck, fresh from his bath, to take gentle skipping exercise. The ladies peering down from the saloon deck seemed vastly amused. Never was such skipping. Achilles' feet seemed to remain in midair as the rope flew round and round.

"Good thing to 'ave quick feet," he panted, "when or bloke's chasin' yer round the ring."

In the steerage are fourteen Austrians bound for Brindisi. They came from Maoriland and boarded us at Sydney. Big hulking fellows with shark-like appetites. No one on this line saw a sea- sick Austrian. They foregather near the stairhead and bolt below in a body the moment the steward appears with breakfast or dinner bell. The struggle to be on scratch when the 8 o'clock bread and cheese bell goes is Homeric. Imagine 220 hungry men tearing down a steep companion, into a narrow dining-room, in the hope of snatching a hunk of cheese. Bill is the only man on board who can arrive at the bread and cheese before the Austrians. Bill's instincts are above cheese-bells or private signals. He knows the exact moment to swoop ahead of the steward when he appears from the pantry. Station life taught Bill a lot of things.

And the food that goes overboard! Any self-respecting bushman who has been on the hunger-track would rise against the criminal waste that goes on among the big Australian mall boats.

Yesterday a cabin steward heaved a basket of loaves over the taffrail.

"Stale bread," said he. "No use for it."

Later a saloon-cook appeared from the galley and flung a huge pan of chops and steak into the unutterable deep.

"No time for dry hash," he grunted. "And the passengers don't take on minced stuff."

"Why don't they carry a pig or two?" asked someone.

A North Coast poultry farmer shrugged his shoulders and sighed. "Thousand a year goes to waste on this boat," he said sadly. "You could run the biggest poultry farm in Australia on the stuff that goes overboard."

The mollyhawks and gulls have a gorgeous time following deep- sea boats. Interesting also to watch the albatrosses slouching from wave to wave, pirouetting, curving in mile-long sweeps ahead and astern of us.

Nine hours from Melbourne the chief steward unearthed a couple of stowaways. Both were city lads, and looked as though a pan of ashes had been emptied over them. They begged to be allowed to work their passage in the stokehold. The chief was inexorable. Both boys were removed to the Afghans' quarters. There is talk of handing them over to the police at Adelaide.

"For eatin' the company's bread and meat, An' breathin' the company's air," sang a fireman from below.

Later we discovered that a conspiracy is afloat among the firemen to liberate the stowaways at Port Adelaide.

A SALOON STEWARD'S job on an Australian mail boat is a better

one than it looks. Wages three pounds a month and found: tips run

it to eight pounds, and often twenty.

Compare the life with that of a city clerk or bush-worker. The steward lives like a prince. His sleeping quarters are equal to a saloon passenger's. His cabin is furnished with a couch and drawers. An electric fan or punkah is fitted over his berth. A cabin boy—the ship swarms with them—looks after his boots, and carries his food to him from the saloon galley. And when ashore he dresses like a bank clerk and travels from place to place in a hansom.

Very few Australian or Maoriland boys take to the business. One fancies that their democratic upbringing unfits them for such service.

"You see," said the chief to me yesterday, "the Australian boy is all very well. His intelligence is far above that of the English boy's—but somehow he makes a very indifferent waiter. When attending to the people who travel by our boats he is apt to become a trifle familiar towards the end of the trip. When reprimanded for his want of politeness he gives trouble.

"We shipped a very smart Australian chap last year," he continued. "He was nimble-footed and good-looking, and could take nine orders while the other fellows were passing the salt.

"He rose to the position of second steward within three months," I broke in enthusiastically.

"Not exactly," drawled the chief. "He got three months at Adelaide for throwing a dish of fried potatoes at the purser before a saloon full of passengers. It was the worst thing that ever happened on our boats. No, sir; we have discovered that the deep-sea Australian steward is a failure."

"They fight all right," I responded dismally.

"Fighting doesn't cut butter in our service, sir," answered the chief coldly. "We want a staff of servants, not pugilists."

We parted coldly. I watched him for a moment as he passed down the glittering brass-plated stairhead into the saloon, where the stewards flew right and left from his august presence.

Still there is hope in the fact that Australia will never produce a nation of stewards.

An 18-stone wheat-man came aboard at Melbourne. For two whole days he had been breaking all the available canvas deck chairs. He merely sits in them, and the rest is chaos.

Bill Simmons has a nice lie-back chair, a combination of sugar-bag and gum sapling. He swears that it is the most comfortable seat on the ship. Every time he leaves it on deck he places a small dog-trap in the exact spot where the 18 stone chair-smasher usually drops through.

So far nothing has happened, although the ship holds out hopes of seeing a stout man tearing along the deck with a dingo attachment trailing behind.

ARRIVED at Largs Bay* on March 14th. A train- ride of seven or eight miles a through several sand-ridden suburbs brought us to the capital of South Australia.

The Largs Bay Pier, where the author's passenger ship

docked, and the train which took him to Adelaide.

The Largs Pier Hotel can be seen in the distance.

[* In 1907, passenger ships to Adelaide berthed at the end of the Largs Pier, a long jetty in Largs Bay. A small railway, something like a steam tram, ran from the pier- end Customs post past the enormous and luxurious Largs Pier Hotel, all the way into the central Adelaide Station. The tramway has long since been dismantled, and passenger ships now berth at a newer passenger terminal further into the harbour. —Terry Walker.]

Adelaide is without doubt the silver-tail all of Australian cities. It is piquant and more respectable than the average vestryman. The near hills that stand out sharply in the morning air, the jingle of the horse trams give it the appearance of a Mexican city. We found parks and churches, and more parks. In our haste to be rid of a telegram we mistook the General Post Office for another church.

The hurrying crowds and gangs of loiterers so apparent within the precincts of Melbourne and Sydney Post Offices are nowhere visible here. Two or three boys idled within its court-like entrance.

A strange man with American whiskers and accent stated in a loud voice that we were in the city of the dead. He said that several more or less dead people haunted the Post Office during business hours' in quest of stamps and other refreshments. He walked round us deliberately and offered to show us where to put our letters. He was sorry, he said, for people who came to the city of the dead. He had come there himself only a month before, under the impression that it was a living, breathing place where men could address each other in loud voices and get drunk.

He told us in his best Chicago voice that he had offered a patent nickel-plated, stamp-licking machine to the S.A. Government for £600. Nothing had come of it. The Government had merely offered him its silent respectable ear. Ten minutes later he tried to sell us a gold watch for £3 15s.—the one that belonged to his dead wife.

Adelaide is not so tame as it looks. It rose early one morning recently and gaoled its ex-Mayor on a charge of fraud and embezzlement. Sydney would sooner die of plague or tram-scare than see one of its councillors safely inside a healthy stone gaol.

Some difference between the men of us the South The Sydneyite will borrow your last shilling; the Melbourne man is satisfied to toss you for drinks; but the Adelaide chap is simply artful—he waits for you patiently and tries to sell you his grandmother's gold watch.

We heard several girls singing inside an up-to-date restaurant. We entered and ordered breakfast hurriedly. Steak and poached eggs. A red-haired girl tripped in singing "Mollie Riley" as she took our order. She told us frankly that she could not help singing when she waited on brown-faced strangers from the Backblocks. We felt glad. Bill reckons that we ought to give Adelaide a good character. Therefore, we take back the opinion anent the artfulness of the city, and apologise by saying that Adelaide is the place where "Mollie Riley" sounds well with poached eggs.

WE returned to the station in time to see the 12 a.m. boat-train depart. Nice fix! Steamer timed to leave Largs Bay at 2.00 sharp. We fretted up and down the platform until the 12.30 started hoping that some unforeseen accident would delay the Orotava another half-hour. Mail steamers have a tricky habit of as sailing on time. When we arrived at de Largs Bay we observed the Orotava moving slowly and gracefully from her anchorage.

Here was a dilemma! Only a few shillings in our pockets and no possible hope of catching her before she reached Marseilles. Our luggage, circular notes, etc., were steering cheerfully towards the horizon.

While I was staring dumbly at the departing vessel, Bill had leaped down the pier-steps and button-holed a grey whiskered plug of a man squatting in the stern of a small motor-launch. I heard Bill's voice rise above the thrash of the tide; I saw his hands poised between heaven and sea.

The man in the motor-launch sat still as could be; his glassy, sea-blown eyes gazing into space. And Bill's voice was round and above him in nine different keys. He explained that all his hopes of future salvation lay aboard the fast-moving steamer. Would the kind gentleman who owned the launch give chase and put us aboard for a reasonable sum—five shillings, say?

The light of reason came slowly into the launch proprietor's eyes. He drew a short pipe from his pocket and scraped it carefully with a knife.

"Blamed if we ain't goin' to have some weather!" he said huskily. "Bit black over Semaphore way."

Bill sat beside him and held his hand half fiercely. He explained that the mail boat was leaving us behind. He repeated his argument in a voice full of suppressed rage. The little old man heard him sorrowfully, but made no attempt to put off. He told us that the business of catching mail boats was full of peril and hardships. Only a month before his launch had been struck by a departing steamer's propeller while endeavouring at to put a couple of desperately-belated passengers aboard.

"Well make it half-a-sovereign, then," said Bill hoarsely. "And we'll take all chances."

The launch-owner glanced dreamfully at the skyline as though it were a distant relation of his. By no word or smile did he acknowledge Bill's offer.

We breathed miserably and waited for the old man to speak.

"If it was for me own child I couldn't do it." he said at last. "It's a terrible long way from here to the steamer. An' she's tearin' up the water more'n I care about."

Bill spoke again and there was another ten shillings in his voice. Nothing a happened. It seemed to us as though the grey- whiskered old battler had been bargaining with desperate passengers all his life. His old sea-blown eyes measured the horizon and the throbbing keel of the outgoing ship leisurely.

"I'll do it for ye," he said after a while: "if ye'll make it another half-crown."

We closed with the offer and sprang aboard nimbly, and were soon tearing horizonwards in the direction of the big Orotava's black smoke-line.

"We ain't got no hope," drawled the old man dismally. "It's terrible waste of time chasin' a 16-knot mail boat."

The motor-launch fretted and plunged in the wake of the leviathan. A crowd to of inquisitive passengers gathered on the starboard side and watched us jubilantly. We could hear them betting on our chance of being taken aboard alive.

"They'll slow down when they sight us." said Bill hopefully. "They wouldn't leave us behind."

"Them slow down!" grunted the boat-chaser. "Why, if yer wife an' family was cryin' out to ye over the rail they wouldn't let down a pound of steam. Mail boats ain't got no feelin's, young man."

The great onrushing steamer was indifferent to our presence. Like a blind colossus she wore seaward, hooting and clearing the blue with her giant shoulders. Several lady passengers waved their handkerchiefs to us.

"If ye'd make it another five bob," broke in the old man, "I'll open her out an' chance it."

We counted out another five shillings. The old man pocketed it lazily and smiled.

"Hold on!" he shouted suddenly "We'll board her on the port."

The launch seemed to leap forward through the blinding spray, shivering and rattling as the seas slapped her hood and funnel. Foot by toot we gained on the Orotava until we ran drenched and half-blinded under her port davits.

The bosun's mate appeared casually over the rail. He regarded us coldly and with to evident disfavour.

"This sort of thing's against the regulations," he said loudly. "Why don't you come aboard in the proper way?"

"Now, Joe," cried our boat-catcher, oilily. "These two chaps are breakin' their hearts to 'ave a bottle of wine with you."

The bos'n was silent. His head disappeared suddenly; then a long wet rope struck us with the force of a well-flung lariat.

"Up for yer lives!" shouted the old man. "Up an' hold!"

Luckily there was no sea on as we clung tooth and nail to the line. Bill scrambled after me with the celerity of a man-o'-war's man. Wet, but grateful we tumbled over the rail.

An officer passed us smartly as we stepped on deck. Bill saluted sarcastically.

"Yer might have waited half a minute," he said loudly. "Me an' me mate represent sixty pounds' worth of passage money."

The officer looked witheringly at Bill, but made no reply.

"Suppose," continued Bill, following him leisurely; "suppose one of your fifty-pound life-boats had broken loose, would you have stopped to pick it up?"

The officer turned eyed him curiously, and vanished down the saloon stairs.

"My word you would!" cried Bill. "You'd have slewed round an' thrown the patent gasometer over the ship's parallelogram."

The stewards are amiable fellows. Constant intercourse with passengers makes them nimble-minded and human. The ship's officer is a different fellow. If you address him suddenly he will look at you for ninety seconds without answering. And if you say things about his gold braid and unimpeachable pants he will retire and invite another uniformed creature to look hard in your direction.

Most of the firemen and sailors say "Baa!" whenever Bill passes along the deck. He doesn't mind. He told them the other night that he'd sooner be mistaken for a crow than a ship's greaser. It must he admitted that he annoys these Cockney firemen. Whenever they come up from below he barks at them from the taffrail. It is a real kind of a bark that causes them to skip round and claw the air with both hands. Bill learned the barking trick when he lost his doe while taking a mob of sheep from Gunnedah to Narrabri once.

THE run across the Bight from Adelaide to Fremantle is

sometimes an uneventful performance. While idling below we

discovered casually that our mattresses were stuffed with

seaweed. No wonder we sleep like Polar bears.

Seaweed makes an excellent bed. It gives out a slight flavour of ozone not unlike St. Kilda beach at low tide. We intend asking the ship's doctor whether seaweed mattresses are intended as a cure for insomnia.

Nice little article for a journalist: Seaweed mattresses: A Cure for Broken down Nerves! London likes to hear about its broken-down nerves.

SUNDAY was an eventful day. An Austrian gum- digger from New Zealand had been acting strangely ever since he came aboard. At 4 o'clock in the afternoon he scrambled over the rail and plunged into the sea. His comrade, a big-bodied, black- whiskered fellow, tore round the decks, snatching frantically at all the available lifebuoys and hurling them over the side. The stewards forcibly restrained him from denuding the ship of its stock of life-saving appliances.

Strange how quickly a man disappears when a moderate sea is running! The eye is continually baffled by the swift-changing surface currents. It was at first surmised that our man had been swept astern, and caught by the propeller. The Orotava slewed round; a boat was lowered in fairly good time, and was soon pulling back through the long, white wake astern. No sign of the gum-digger anywhere. The boat cut here and there, travelling far, until it was lost to view.

A mail boat is as impatient of delay as a woman with an appointment. She fretted and heaved while several officers searched the wave hollows from the bridge for a glimpse of the unfortunate man. Five hundred people crowded the sides, peering across the long in-sliding seas that swept under our stern. A flock of sea hawks and albatrosses circled in groups at a certain point in our wake. A dozen glasses covered them to ascertain whether the struggles of the Austrian had caused the unusual commotion among the birds. Brown-winged mollyhawks and black shags joined the scrimmage, thrashing and screaming in mid-air, as though anxious to share the spoil.

"Those big birds will drown a man," said one of the sailors to me. "I've seen 'em settle on the head of a swimming boy and drive him under."

"They're a derned sight worse than sharks," added a New York man excitedly. "I got adrift from a whaleboat up in the Barrier, some years ago, and a big, skulking cow-bird came at me claw and wing, as if it wanted my two eyes for breakfast.

"A man can't fight birds when he's swimming for his life. He's got to chew up all his bad language and duck his head," continued the American. "I ducked every time it clawed my head until I was blamed near silly and half-drowned. Every time my bald head showed above water the derned wings hit me on the face and jaw.

"Then I felt my mate grip me by the shoulder and haul me into the boat. Guess he wasn't a second too soon either. About a dozen other cow-birds had swarmed round and started sharpening their claws against my scalp."

A sudden shout from the Orotava's stern told us that another boat had been lowered. A minute later we beheld the missing Austrian being lifted into the stern, a life-buoy gripped tenaciously in both hands. He had been in the water exactly 35 minutes. His lips were blue from exposure; his jaw hung listlessly as the boat was heaved to the davits. He was placed in hospital immediately and received medical attendance.

Later, an inquiry was held concerning the manner of his going overboard. It has been considered advisable to keep him under strict surveillance during the rest of the trip.

The approach to Fremantle is fairly easy and far less monotonous than that of Melbourne. To the uninitiated eye the deep-water channel is well buoyed and lit, although from Rottnest to Cape Leeuwin the sandbanks have a camel-like habit of appearing on the horizon. A launch conveys passengers up the Swan River to Perth.

We did the trip in a blinding shower of rain—the first for many months. Off Five Fathom Bank lies the hull of the Orizaba, gulls and hawks circling round its weatherbeaten sides. She was caught in a fog more than a year ago, and ran aground. The Orizaba was a splendid sea-boat, and on account of her good qualities her insurance was reduced 50 per cent. The company had decided to withdraw her from the Australian service; but the fog willed otherwise, and Five Fathom Bank holds her till wind and sea shall have sundered her planks.

The RMS Orizaba after being abandoned in 1905. It

remained visible for years, gradually breaking up. The

remains on the shallow sea floor are now a diving site.

One hundred and fifty passengers, mostly young men, left at

Fremantle, bound for Kalgoorlie and Leonora. The gang of Afghans

streamed ashore, glad to be out of the stuffy fore-hold, and

eager to face the open camel tracks again. Times are supposed to

be dull out West, but the crowd of new arrivals think

otherwise.

"It's hot out beyond," said one: "but tucker and wages are all right. Good-bye, old man."

Perth itself was a revelation to us. We had pictured it a veritable Chinatown among the sandhills and ti-tree swamps. The railway from Fremantle to the capital serves a dozen thriving suburbs. Everywhere one sees the hand of the builder at work. Acres of outlying scrub are being cleared; homesteads and factories bob up from behind yellow sandhills and tree-covered heights.

Perth is probably the most modern of Australian cities. The streets are well laid out, and from east to west one feels the throb of new life streaming into the capital. Here and there a dilapidated boarding-house peeps from the rows of well-built dwellings.

The mind goes back to the early nineties, when the East invaded the West, and the strenuous crowds of gold-hungry men flocked in from Adelaide, Melbourne, and Sydney. The ancient boarding-house suggests days and nights of wild excitement when the sand-bitten prospectors crowded back from Bayley's and the Murchison into Perth.

To-day the old coastal steamers are reminiscent of the old days, when crowds of successful miners stampeded homewards in quest of elusive pleasures and the girls they had left behind. These were the days when champagne ran into the scuppers, and every steamer was transformed into a floating Monte Carlo.

"I remember when the first bit of fresh mutton came on to the Great Northern," said Bill. "Neck chops fetched eighteen-pence a pound, and the heads were auctioned at five shilling apiece. The drover who brought 'em over started from Perth with 700 and landed 150. He said there wasn't enough feed on the way out to tickle the leg of a grasshopper."

A decade of stock gambling has produced a shrewd type of business man out West. He is not to be confounded with the Wall- street alligator or the London mining spieler. He is a shrewdly happy man, with enough nous to keep himself free from the soul- rotting influence of the game.

Telegrams to hand announcing the wreck of the Mildura off North-West Cape. She was bound for Fremantle, with several hundred cattle on board. Grim stories are already afloat concerning the last moments of the Mildura....

A stormy night off a treacherous coast. Heavy seas thundering over the frightened ship. Pens and boxes smashing to and fro. Dead cattle and top hampers flung for'rd in Dante-esque heaps. A crew of sweating and half-maddened sailors heaving the dead beasts overboard.

"Cattle ships are hell!" said Bill thoughtfully. "I was cook on the old Dominion, running between Halifax and Liverpool. Her for'ard decks was like the Homebush saleyards. We were carrying three hundred big-horned Canadian cattle to Liverpool; ugly long brutes that any decent Australian squatter would shoot at sight. About three days out from Halifax we walked into dirty weather that took away our funnels and bridge as if they were made of tin.

"About midnight we heard a smashing of glass above, an' one of the stewards came tearin' below with the fear 'of Gawd in his eyes. He had been carryin' drinks into the saloon when the cattle barricade broke away.

"'They're loose!' he sez,' crawlin' under the table. 'Oh, my Gawd, they're loose!'

"We listened... an' heard the big barricades slammin' against the port staunchions. Then a sea lifted an' rolled us down an' down until the water poured through the blamed skylights. The next sea put us on our beam ends, an' spilled the cattle over the deck in scores.

"Don't know that I'm a coward," went on Bill; "but I know when to fold up when the bullocks are out. One of the brutes, a big- horned starver, raced along the galley-way, and galloped right over the stern. The others came after him, until another sea downed the leaders, and in two minutes the alleyway was blocked with broken-legged cattle bashing the life out of each other on the greasy floor.

"A bullock's body was half-hanging across the stairs. They were piled in heaps around the skylight an funnel stays. We had to shoot half of 'em before we could clear the deck an' hoist 'em overboard. Talk about Port Arthur! You don't get me on a boat that ships wild Canadian bulls!"

Bill passed for'ard to assist a pantryman with the dinner. A voice said "Baa" as he passed.

Bill merely smiled. He returned an hour later with a roast fowl wrapped in a newspaper.

WE left Fremantle at 8 o'clock on Monday night and began our climb north to Colombo. The journey across the Indian Ocean is apt to become monotonous. The endless stretches of sea and sky, the absence of bird life, has a numbing effect on the eye and brain. We spent an hour looking at the ship's freezing chambers, and met a small procession of stewards carrying ice on their backs up to the saloon pantry.

Last trip the ship's cat got locked in one of the freezing chambers and remained there for nine days surrounded by frozen poultry and meat. It is a mystery how she kept herself alive in such an Arctic temperature. When released she bounded upstairs into the hot air and fell asleep on the saloon couch. She was as lively as a kitten the next day.

The English stewards and deck hands appear to suffer from the heat already, and we are five or six-days south of the Line. They are mostly fat, overfed fellows who believe in a good beefsteak and a bottle of stout before going to bunk every night. No wonder they lie awake during the tropic nights wearing a pale bloated expression on their faces.

We have discovered that quite a number of New Zealand boys are working their passage to London. One took on a job in the stokehole, but gave it up before we had been three days out of Fremantle.

The ship's surgeon is busy this morning inside his little deck dispensary. A small procession of patients wait outside on the form. A fireman crawls along the port alleyway exhibiting a badly-scalded foot to his comrades. A white-faced greaser with consumption in his luminous eyes enters the dispensary and is examined by the genial surgeon.

The Cockney fireman is a born tough. He does not mix with the rest of the ship's company. His work unfits him for polite society. The Sydney larrikin would not be seen dead in his company. Down in the throbbing spaces under the engine-room he slams things and rakes with slice-bar and shovel, feeding the fire-hungry boilers that gasp and sigh for coal and yet more coal. His boots are amble-shod to protect his feet from the burning plates. His hands and body are scarred and livid where he has been flung at one time or another against the boiler doors. When ashore he finds much relief in fighting policemen. If he has been stoking for ten years, his brain is more or less affected by the terrible heat and the violent changes to which he is subjected. They come up from below dripping from head to shoe with coal blackened bodies, slack-jawed and limp as fever patients.

The Red Sea is the horror of all white firemen, and black ones for the matter of that. In the majority of cases the rum served out in cold latitudes is saved until Colombo and Aden is reached.

"Rum is our mother and father," said one of them to me. "It feeds us when we can't eat, an' it makes us sing when the heat is crawlin' down our throats."

"But the after-effects?"

"There ain't none. The fires sweat us dry. It shrivels us up an' biles us, an' there ain't no room left for' after effects. I've tried oatmeal water an' cold tea, but neither of 'em keeps off the heat like rum. Rum 'as got hands an' feet, an' it nurses yer when yer dyin' below."

"Do men die below?"

"Die! Some of us was never properly alive. I've seen white- faced corpses of men shovellin' beside me. Yer can't get 'em to speak. Yer never hear 'em complain neither until they lie down, while the second engineer gives 'em an ice poultice."

"How do Australians face the music below?"

"They're quitters when the clinkers are out. Most of 'em would sooner fight the chief than stay through the Red Sea."

"Make the game good enough," broke in Bill, and we'll fill our stokeholes with Australian firemen. Why, stokin's a fool's game compared with sewer work and rock-breaking. I've seen a gang of Australian-born men face choke damp an' dynamite year in an' out, when the wages was all right. But 'you ain't going' to get our live men to sweat in your stokeholes for four pounds a month—not while there's a rabbit in the country."

The discussion ended abruptly.

Increased ventilation has made the stokehole of the average mailboat a more comfortable hell than formerly. But so long as London can supply legions of the damned at three to four pounds a month, the steamship companies will allow poor Jack just enough air to keep him from dying with a shovel in his hands.

WE have on board about fifty affluent farmers from New Zealand and Australia. Hard work and strict attention to the butter industry has brought its reward to the majority. It must be admitted that the New Zealanders as a whole swear by the land which gives so bountifully and requires so little in return.

The nights, especially while crossing the Indian Ocean, are delightful beyond compare. In the smoke-room and on deck those well-to-do farmers compare notes and methods of conducting an up- to-date dairy farm. This cow-talk, as it is often referred to by the sailors, is often amusing and full of human interest.

"I'd sooner have women and children to look after my cows than men," said an Otago passenger at dinner. "If a cow kicks a woman she doesn't rise and hit it with an axe or paling. She simply wipes her face and tells the animal that it is a wicked creature, and if she isn't badly hurt, will go on milking again. When a man gets kicked he stands up and belts Gehennna out of poor Strawberry, specially it she is not his own property. Result is that Strawberry gets to hate him, and his milk returns will fall off wonderfully through the year."

"I don't know about women not hitting back," put in Bill suddenly. "Dropped a maul on my wife's toe one morning, and she kept me runnin' round the paddock for 13 minutes by a the clock. Still," said Bill, genially, "I don't remember ever seeing at woman lay violent hands on a cow, although I know a lady out West who hit a bull camel in the nose with a flat-iron when it poked its upper lip through the kitchen window one afternoon. She had great presence of mind, that woman. But she told me afterwards that she mistook the camel's face for a sowing machine canvasser. Some of these machine agents have wonderful upper lips," concluded Bill.

We crossed the Equator at 4 o'clock on Monday, March 25. The day was warm, but not so unbearable as Sydney or Brisbane during midsummer. Consideration must be given to the fact that a mailboat rushing along at 15 knots an hour creates a refreshing air current. Hereabouts the dawn skies are full of weird beauty. The sun peering over the sky-line flings scarf on scarf of wine- red light across the naked East. The north-west monsoon roars into the big-throated windsails, flooding the lower decks with cool air. The vertical sun, when veiled by clouds, casts a blinding salt-white radiance over the face of the ocean.

PAST midnight two officers awoke the captain, who appeared suddenly on the bridge scanning the distant horizon. Since eleven o'clock the barometer had fallen considerably, and the sound of the bos'n's whistle and the hurrying or feet along the deck warned us that something special in the way of typhoons was bounding across the far West.

A strip of inky cloud about the size of a shawl fluttered on the horizon. A far-off humming noise reached us as though innumerable harp-strings were being rent asunder. The black cloud-shawl opened fanwise, revealing its huge wind-torn body.

"Heaven help the cargo ship that runs into it to-night!" said an old salt standing near the bridge.

The sea grew white under the enfolding body of the cloud, as though whipped into mountainous waves by the fury of its onslaught. Incidentally our ship turned her heels to the onrushing mass of cloud and water, her increased funnel-smoke showing that pressure was being brought to carry us beyond the track of the old-man typhoon.

The strumming note of the storm changed swiftly to a deep booming sound that seemed to slide under out keel with the force of an avalanche The water fairly snarled as it flew over the rail. The fury of the wind-driven waves is incredible. They appear to attack a ship from all points, as though guided by an unseen brain. The wrenchings and groanings of a big ship as she plunges and rolls into the mountainous hollows are almost human.

Imagine a sea sweeping away a couple of lifeboats fixed securely in their davits forty feet above the surface of the water. Mile on mile we skirted the down-rushing typhoon, which seemed to confine its operations within a special area. Far away in the west the sky was clear and full, of stars. Yet the near east was a cauldron of storm-whipped clouds and seething water.

"We's only caught the edge of it!" shouted a voice in my ear. '"It doesn't pay to run away from ordinary storms, but this affair would bend our patent ceilings and deck-fittings if we pushed through it. Indian typhoons are better left alone."

And so it proved even though we had only danced a polka on the skirts of the storm. Two hundred gallons of fresh milk had been burst asunder in the ice-room. A row of sharp meaty hooks pressing suddenly against the big tins had sliced them asunder, allowing the milk to run over the floor. About a hundredweight of crockery came to grief before the pantrymen could stow it safely away.

To prevent loss by carelessness on the part of these servants, many of the Australasian shipping companies have inaugurated a Missing Silver Fund. At the end of every trip the chief steward goes over the table cutlery and plate carefully and each missing article has to be made good from the fund. As much as ten shillings per head is deducted from the stewards' salary to replace lost articles. The chief explained the matter briefly to a party of saloon passengers one morning.

"Before the Missing Silver Fund was started," he said, "our losses through carelessness were very severe. Last year a pantryman left a locker of entree dishes and tureens near the port rail while he adjourned to a cabin to light a cigarette. The vessel rolled suddenly and £150 of plate went overboard.

"I had occasion to watch a young Australian steward one morning," went on the chief. "He was engaged in sweeping out the first saloon smoking-room. It was his duty to rinse the cuspidors, very expensive articles, costing us from one pound to thirty shillings each. He picked up one casually, looked round the empty smoke-room sharply, and pitched it through the port- hole. 'One less to clean,' he said, and went on sweeping. Yes, we've got a check on that kind of thing now. The stewards watch each other, and every spoon and fork and dish is guarded pretty closely."

Within three hours we had left the typhoon-area in our wake, and the grey dawn showed us the black funnels of a P. and O. liner bound from Colombo to Fremantle, her saloon lights gleaming with star-like brilliance across the naked sea levels.

EVERY sea traveller is at the mercy of his cabin attendant. Ladies are usually the easiest victims, and during a long trip the cabin thief has plenty of time to shepherd the movements of his intended prey.

The thief is careful not to rob a passenger under his charge. He prefers for obvious reasons, to purloin from people far removed from his own round. It must be admitted that Australian shipping companies are swift to punish all cabin-marauders who manage to sneak into their service. But it is almost impossible to deal with the vast, ever-changing army of stewards who habitually sail under assumed names and borrowed discharges.

One occasionally meets a Cockney rascal who brags of his success as a cabin thief. The lightest appeal to his criminal vanity will extract the desired information.

"Hi'm a pore bloke on the look out for snatches," chuckled an undersized imp recently. "You cawn't 'elp makin' a bit when yer lookin' after sick passengers. I nicked a diamond ring lawst trip while the old lydy was comin' out of the bawth-room. The bawth- room's the plice to find rings. Soap an' water eases 'em off the finger, an' they drop on the floor.

"Yus, I picked up this kooh-i-noor, an' blime it was nearly 'arf 'a pound weight, big as a glass-stopper, in fact.

"Ten minutes after, when the old lydy gave, the alarm, the whole ship turned out to look under the bunks an' feel down the bawth-room pipes for it.

"The doctor's boy comes up to me point-blank. 'Hey, Wilkin', he says, 'chief wants yer. Reckon he saw yer pokin' round the bawth-room just now.'

"Nice pickle, I sez to myself. If they catch me with the diamond in me pocket. I'll go to choke. I ducked below into the stokehole, and puts me little koh-i-noor under a 'eap of coal. Then I tore on deck casu'lly and faces the chief.

"'About that diamond. Wilky,' he sez. 'Stand up straight now, yer eyes are shinin' like a Newgate lamp. Where's the diamond, Wilky?'

"'Diamond?' I sez. 'Why, Lord like me, I ain't seen nothin' brighter than me hat since mother died! I 'ope yer don't think I borrowed the old lydy's blinker?'

"The master at arms searched me, an' then the 'ead stooward ran his 'ands over me leadin' features.

"'Wilk,' he sez, 'tike care of yourself. Some diy you'll fall over the door-mat.'

"'An' I 'ope you'll keen' yer chin up when the floor hits you,' I sez perlitely.

"With that I started on me cabins an' cleaned up before inspection. After I'd finished I toddled into the stoke-hole to warm me 'ands:

"'Ello, Friday,' says I to one of the firemen. 'Ow would a bit of roast duck go before dinner?'

"I dawnced past him and looked for me little 'eap of coal in the corner of the bunker.

"Where's the bit o' slack that was 'ere an hour ago, Friday?' sez I. 'Blime, you ain't been sweepin' up. I 'ope.'

"'Cleaned up the plates five minutes ago, Wilk,' says he. 'All the dirt's gone into the fire, my boy. What about the roast duck?'

"'You blasted old —!' I sez. 'I 'ope you'll die face down in quod.'

"It was the on'y blessin' I ever chucked away. It's bloomin' hard to pray for yer enemy after he's shovelled yer diamond into the fire. If I'd been 'arf a foot bigger I'd've shovelled him in on top of it. Wouldn't you, eh?"

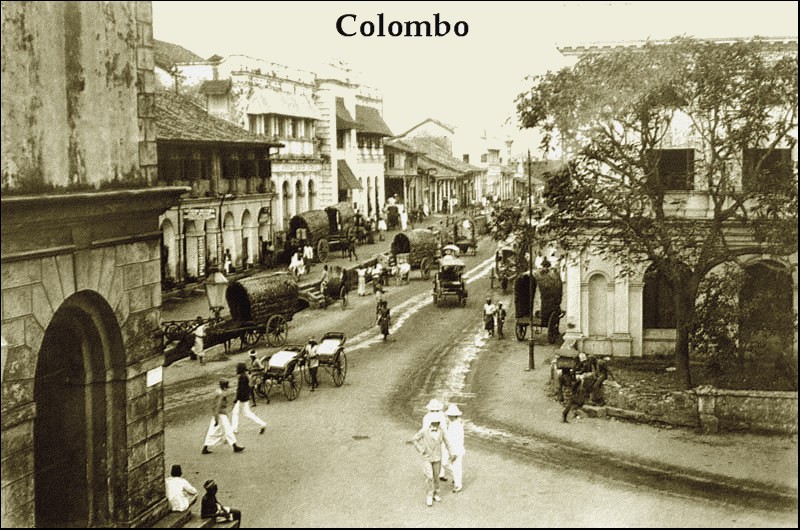

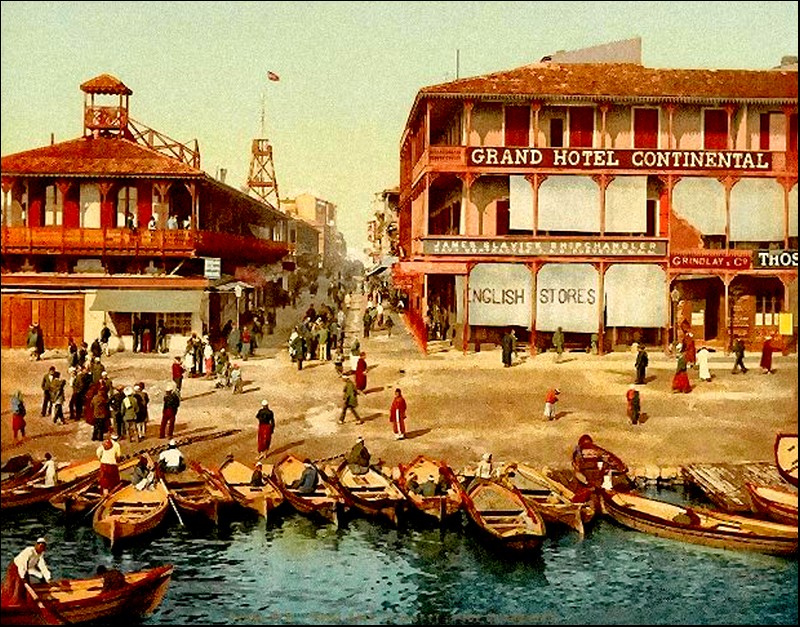

Colombo, Ceylon, 1907.

MIDNIGHT, March 27: A faint odour of cinnamon stole through the sweltering air. After ten days of sea and sky men moved uneasily in their cabins, as though a strange voice was hailing them. Men and children came up from their stuffy berths, fixing their land-hungry eyes on the far north. A white light flowered ahead, and stabbed the darkness with its pointed warning. Later a procession of moon-sized lamps wheeled upon us from the north-north-east where Colombo sweats on the edge of the Line.

The hot darkness seemed to press upon the fact of the scarce- moving sea. An unquenchable heat enveloped the ship—a sticky, slimy boat, loaded with perfume and occasional swamp odours. Out of this steaming darkness came boats and murmuring voices. And long before we had dropped anchor a number of shining bodies appeared on our port rail—wet-skinned Tamils and Cingalee laundrymen, voiceless as yet, but eager for business when the moment arrived.

It would take a hundred stock-whips to keep the adventurous Cingalee from entering your cabin. As fast as the stewards drive him from one quarter of the ship he descends another. He is an aggravating small thief in his way; his eyes are full of tender reproach when you accuse him of stealing your razors and soap. Caught in the act of opening your valise, he will tell you point- blank that it is not a valise, and that he is not in your cabin. In fact, he will swear that he is not himself, and that you are another person altogether. His logic is bewildering. But it is a great relief to hit him with his own thick walking-cane.

Four Tamil coolies rowed us ashore in an evil-smelling fruit boat and cast us adrift on an unfriendly pier, swarming with backsheesh men and Malays. The backsheesh fiend charges two cents for wishing you good morning; the memory of his villainous breath will follow us across the three oceans.

Climbing the pier steps, we walked, so to speak, from the sea's bosom across the feet of Asia. It was not yet day, but the red roads stretched suddenly before us in an Eastern frenzy of colour. At the end of one red road stood a pile of salt-white buildings, fronted with Irish-green palms and lip-red flowers. We passed the Governor's residence, where an army of high-caste Tamils were sweeping the wide lawns and beating fawn-grey carpets against the austere palm boles. Large Asian roses climbed over the teak-shingled roofs. Native servants in pantomime-coloured silks flitted across the road, carrying flowers and feather- dusters and brass trays.

The dawn was thick with crows; the road and housetops were alive with them. They foregathered within the porches of the Government buildings and on the steps of the drinking fountains. They ca'aed at the post-office windows and obstructed the foot- walk. Unlike the Australian crow, the Ceylon carrion-eater will venture within kicking-distance, and refuses to be shooed away. No one interferes with them; they are as sacred as the Indian bull or the tooth of Buddha.

A crowd of rickshaw men ran out to meet us: in a jiffy we were being rushed through the native quarter of Colombo towards the famous Cinnamon Gardens. The native quarter of Colombo is the abode of the Seven Smells. We had smelt dead whales at Eden, but the odours that walked from the native bazaars will always occupy the top hole in our memory. Every doorway held its sleeping coolie, some huddled on mats, others stretched corpse-like in front of their wares. The sea-weary eye turns gratefully upon the still, palm-shrouded lagoons which flank the narrow, chrome- coloured roads, beaten to powder by the tramping of innumerable feet. On our right stood a wide-gabled Buddhist temple, its crow- covered roof crimsoning in the sun-rays. A priest was standing in the courtyard, motionless as a stake, his old eyes fixed on the reddening East.

At the foot of the temple steps a crowd of boys were splashing and swimming in an artificial lake. Entering the Cinnamon Gardens we passed troops of Cingalese girls running towards a white- walled silk factory, shut in by dense foliage and creepers. The hot air was full of laughter as they ran. They laughed at the Australian's straw hat and the kingly way he sat in his 20 cent rickshaw.

There is small worry in a land where girls and women run laughing to work. One recalls the crowd of stern-laced factory girls that troop from the Sydney and Melbourne railway stations on their way to their obnoxious toil. Also, the Cingalee girl is very happy while earning her 25 cents a week, and she is never so tired as the Sydney tearoom girl earning thirty times the amount.

The streets are crowded with processions of heavy waggons drawn by small buffaloes. The Ceylon buffalo is not to be compared with the Australian bullock. In comparison with the fast-moving native animal the bullock is a snail and a full brother to the tortoise. At a touch of the hand the mouse- coloured little bull drops into a fast canter that equals the pace of an ordinary pony. The lush native grasses and irrigated feeding-grounds are responsible for the buffalo's stamina and condition. When unyoked at night from his heavy pole, after a 16- hour jaunt under an equatorial sun, it will gallop to the nearest lagoon and wallow in mud and grass until dawn.

Everyone visits the Buddhist temple, where the tooth has reposed for centuries. The exhibition of the sacred molar is a silly fraud. The real tooth was smuggled here from India 1,500 years ago in the coils of a princess's hair. It was afterwards stolen sand passed into the hands of a Cairo Jew. After inspecting the alleged tooth it occurred to us that the long departed Buddha could have easily beaten the average shark in the way of jaw formation if the rest of his front teeth compared with the one on view.

As the sun rose over the temple roof a young Tamil girl appeared from a palm-shadowed hut, leading a small, slate- coloured bull to the sandy shore of a lagoon. Drawn about her waist was a sarong of unutterable scarlet. The bull walked beside her gravely until the lagoon water splashed their hips. Singing softly to herself, she began to wash the mud-covered flanks and surly head beside her. Her dripping black hair swished about her naked shoulders as she stooped and emptied a vessel of water over herself and another over the sullen little buffalo.

Other girls came to the lagoon leading fawn and black buffaloes by the ears. The nuggety little animals stood motionless while the small brown hands scrubbed them from head to heel. The Australian girl is too tired to wash her father's cows, although the writer once saw a hefty woman assisting her husband to dye a horse. They had a scheme on hand for running it under a false name.

The Cinnamon Gardens is a pulseless kind of a beauty spot. It is the garden of sick men and pale perfumes. Along its borders are endless palm-sheltered roads and stagnant malarial lakes. Around these malarial lakes are scores of pretty detached villas, owned by prosperous tea and rubber planters. Every garden and lawn has its half-dozen native attendants, watering flowers, cutting grass, and trimming the long rows of English hedges. The affluent Cingalese merchant rides city-wards in his fashionable dog-cart or Victoria. Behind him a couple of thin-legged Tamil servants to yell at the mob and threaten the obnoxious rickshaw men.

Many of the Cingalese merchants are enormously wealthy, owning large silk and tobacco warehouses. Their wives and daughters rarely associate with white men, and one seldom hears of a Cingalese girl marrying out of her religion. They are mostly Buddhists and vegetarians, and when it comes to-driving a bargain the local Hebrew is comparatively a voiceless nonentity.

Between 8 and 9 o'clock the city roads are crowded with Cingalese boys hurrying to school. They read and coach each other in English as they pass along, correcting their arithmetic, and spelling aloud in their native earnestness to acquire, the language. As youngsters, they are abnormally intelligent and far ahead of the average British boy. In after years they fill nearly all the Government positions, from station master to town clerk.

Returned from the Cinnamon, feeling hot and depressed. The numerous convalescent Englishmen, taking their early walk, made us feel lonely. Colombo impressed us as a violently unhealthy place. The death rate among local whites this year is higher than that of the Gold-Coast, West Africa. As we crossed the hotel mat a Cingalese rose wearily from beneath, and told us in a faint voice that we had walked on his body. Half-an-hour later he appealed for compensation, and received threepence.

Climbing the hotel stairs we stepped gingerly over the faces of the long-haired men and boys sleeping in the corridors and doorways. An hotel coolie will pass the night anywhere except in bed. He will sleep on the roof or in the bath under the shower drip. We saw several legs dangling over the waterspout immediately over the bedroom window. Spent ten minutes trying to lasso a pair of hanging feet with some barbed wire. Feet shifted suddenly.

The white man in the tropics rarely changes his habits. He clings to his 10 x 12 bedroom, and closes the windows every night, even though the temperature is past the nineties. The hotel bedroom kills half the white men living on the Line.

In Ceylon hotel rates vary from six to ten rupees a day. If a native servant extinguishes your candle at night he expects a tip, and he will follow you through he streets calling out the nature of your meanness until you disgorge.

In certain districts the Government have provided rest houses for travellers. Every item is charged for separately; even bed linen is looked upon as an extra, while bed and bedroom cost 50 cents each. A 30-cent charge for habitation knocks the Australian endwise when he scans his first bill.

The Ceylon police are unable to control the coolie mob that besiege visitors at every rahway station. The unwary traveller suddenly finds himself surrounded by a clamouring, hysterical body of Tamils who refuse to let him pass until he inspects their stock of cinnamon sticks or packets of dirt-smeared post- cards.

AT Lighthouse Point Battery we saw a fat white man seated on a sandhill bossing a gang of girl navvies. There were 100 in all, brown-skinned Tamil maidens of the coolie class. Some were handsome, heavy-limbed youngsters, well-set, and strong as horses. They carried baskets of stone on their heads with freedom and grace. Others manipulated sand, carrying it from the beach to the railway embankment. One or two women with children at hip slaved through the ankle-gripping drifts to deposit their loads on the growing heaps. The women earn from 12 to 15 cents a day. For similar work in Australia a white navvy would receive seven shillings at least, and would probably throw down his basket after the first hour.

Occasionally when the sand-shifters slackened their gait or exhibited signs of fatigue, the fat white overseer would rise and address the sweating female gang in a voice of thunder. The younger Tamil girls responded like horses under the whip, outstripping the women with the babies and flinging down their loads of stone and sand with great bravado.

The fat white man impressed me considerably. I met dozens of his kind later while journeying from Colombo to Kandy. He is the noble warm-water Englishman who drifts equatorwards in quest of a soft job. At home he is the man who can he spared. He has sailed in the army or navy, and his weary eye turns towards India or Ceylon. His lotus-like instinct warns him that Australia is no place for a drifter, and he finally wanders to the land of the coolie and the long lazy afternoon. He usually find a billet on the rubber plantations as assistant superintendent, bossing women coolies and shouting himself hoarse over the mistakes of soft- eyed, ill-trained native children. The warm-water Englishman is, no doubt, a good fellow in his way. He sends his wife and children to the hill sanatoriums, and attends the funeral of his brother overseers whenever they die of heat apoplexy or overfeeding. Still one does not care to recall the tired white man and his gang of sweating Tamil girls. It is the cry of the mother that hurts, the little pitiful calls of the child-burdened women asking for a moment's respite as they struggle over the sand drifts to build the white man's breakwater.

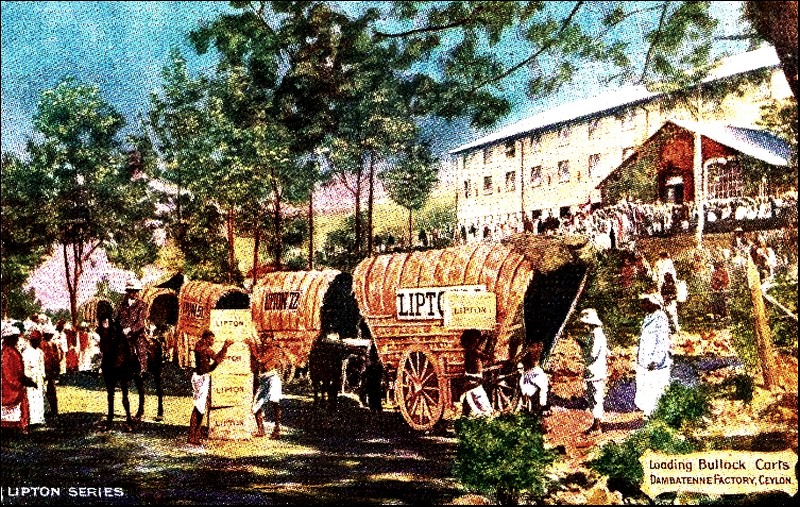

ON the morning of our arrival we received a visit from a well-known Australian, who invited us to stay for a few days at Dambatenne, one of Sir Thomas Lipton's tea estates. Dambatenne is about 70 miles inland, and is reached by a railway which passes through the most gorgeous mountain scenery on earth.

The Easter holiday trains were crowded with visitors to Newara Eliya, the Simla of Ceylon. Newara Eliya has an elevation of 6,200 feet above sea level. The rahway climbs over steep gorges and mountain torrents, and there are times when the traveller has to leave his sleeping berth and walk behind the train when landslips or washaways are expected!

During the wet season, washaways are pretty frequent. Last year a pilgrim, train, bound for Kandy slipped over an embankment and it emptied a crowd of screaming men and women into the gorge below. About 40 were killed outright, and to-day many passengers crawl after the train when it arrives at a dangerous curve on the mountain side rather than risk a ride where a mere wheel separates them from eternity.

In the refreshment car I sat near a fat white man wearing a solar topee and a big Burmese ruby on his middle finger. He was addressing another pale face over a whisky and soda, and his high-falutin' views on coolie labour set me thinking hard.

"A man comes here and take up rubber land at twenty, rupees an acre," he said loudly. "He spends two thousand rupees clearing and building his coolie lines and feeding 'em. My advice is: 'Don't pay your Tamils until the land pays you.' They'll grumble a bit and sulk, but your head kangani will boot the grumblers off the estate. I know one coffee man which ran his lot for three years without paying a cent in wages to his coolies. He kept on discharging the disaffected ones and filled his lines with fresh boys from the low country about every six months. Oh, you don't got me giving any substance to coolies until the estate begins to pay."

"That man is a skite," whispered a traveller. "Ceylon is full of such men. The Tamil labourer is too darned cute to work without pay. If you played the trick on a gang of low country coolies they'd stone you out of yer bungalow."