RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Radium Terrors," Eveleigh Nash, London, 1912

The text of this RGL Edition of "The Radium Terrors" conforms with the 1922 reprint published by Doubleday, Page and Company, Garden City, NY. The introduction and illustrations are from the serial version of the novel published in The Pall Mall Magazine in 1911. —Roy Glashan, 13 May 2019.

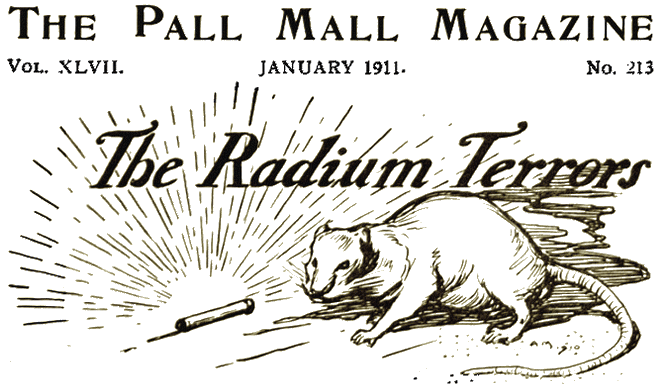

Headpiece from The Pall Mall Magazine.

"The Radium Terrors" brings the reader into a new Field of Romance. In this story we are confronted by an astounding type of Japanese criminal genius, one Doctor Tsarka, a weird and terrible scientist, from whose subtle brain is evolved the plot which terrifies London, where the various acts of the sensational drama take place. Having, by a piece of devilish ingenuity (the subject of one of the most exciting chapters in the story), become possessed of a quantity of the precious Radium, the Doctor is enabled to conduct a series of radio- surgical infamies which defy all the craft and daring of the private detective who is ever at Tsarka's heels, and all the powers at Scotland Yard.

Each chapter reveals something of the passionate determination of the children of Nippon. Detectives, civilians, friends of the organisation—all are sacrificed to their insatiable lust for wealth. Doctor Teroni Tsarka's experiments in radio-active surgery startle and bewilder the human mind. We experience for a moment the pain of the condemned figures seated in the chair or operating theatre. We hear the voice of the modern physician and therapeutist proclaiming courteously some pitiless alternative in radio-active surgery. Indeed, after a perusal of the first few chapters we feel that Mr. Albert Dorrington, the author, has broken ground where the Goddess of Science still beckons from her unsealed pinnacles, and his keen vision combined with a perfect genius for dramatic situations has invested in "The Radium Terrors" a succession of swift-moving scenes in which the Doctor and the detectives plot and counterplot, and which will hold the reader spell-bound until the conclusion of the story, which will appear in six instalments.

A feature of this new Serial will be the fine series of startling drawings, in colour and black and white, by A.C. Michael.

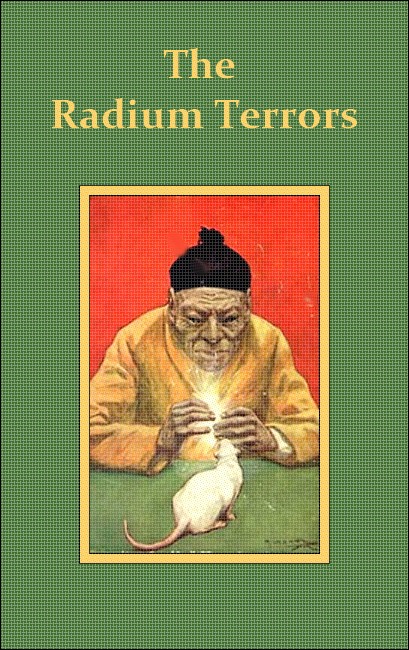

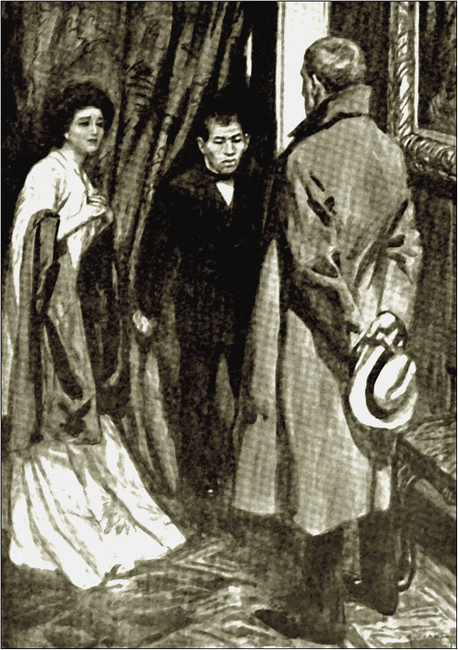

Frontispiece.

He looked once at Pepio and the at young

detective. "You make great intrusion," he said.

"I'VE been hunting for a little god that escaped from some pitchblende, Tony!" Gifford Renwick entered the smoking-room of the International Inquiry Bureau shaking the raindrops from his hat and coat.

Tony Hackett, a small, cherubic man with wheat-red hair and uncertain eyes, was seated near the fire. Renwick's words caused a listening blindness to cloud his glance. He responded without looking up at the young man beside him.

"If I were to hazard a guess, Renwick," he said thoughtfully, "I should say that your god will hate you like poison when you've found him. Sit down and let's hear."

Renwick's boyish face was flushed from the effects of some recent excitement; a nervous expectancy strained him to the point of laughter.

"I've been smoke-hunting," he declared with an effort, "in the hope of finding a genius tucked away in the coils."

"Well!"

Renwick shrugged. "I came very near to making an ass of myself, Tony—the same old donkey that brays on the slightest provocation."

"You are the only youngster in Coleman's service who can differentiate between an astral body and an Army mule," Hackett admitted graciously. "You've been chasing those radium thieves, I suppose," he added. "Don't let 'em worry you, Renny. The god in the pitchblende is going to whiten the hair of your superiors before the case is over. Try golf with your whiskey for a change. It's wonderfully soothing."

Gifford Renwick dropped into the big armchair to study the gray smoke and reddening flames, for he had found the key of many a teasing problem hidden in the white ashes of a winter fire.

The room in which they sat was one set apart by Anthony Coleman for the use of his officials. Gifford Renwick had become a member of Coleman's private detective service some three years before. The salary paid him was infinitesimal, the prospects of increased pay enormous. Tony Hackett had reached the three- hundred-a-year line, while Renwick, in his twenty-third year, did official spadework for half the amount.

The theft of the Moritz radium tube had quickened his senses. For the first time in life he was brought within the operation area of an unknown criminal organization, and the experience made him feel humble and ashamed.

A glass tube containing six grains of pure radium, valued at as many thousand pounds, had been stolen from the laboratory of Prof. Eugene Moritz. At Scotland Yard the affair was diagnosed as a bit of "ghost work," without parallel in the annals of unsolved mysteries.

To Renwick the case presented itself as the most fascinating problem in modern criminology. Professor Moritz averred that the radium tube had disappeared while he was engaged in conversation at the laboratory telephone.

At the time of the incident, the professor deposed, the doors and windows of the laboratory were securely fastened. There had been no possible way of entry without his knowledge. About eleven o'clock in the morning he had received a call at the telephone. Placing the glass tube containing the radium on his work-table, he had turned aside for a few moments to take hold of the receiver. When he returned to the table the tube was missing.

Previously to the incident he had been engaged in a series of experiments which, according to custom, had been conducted with windows and doors locked to prevent unlooked-for interruptions. Professor Moritz was emphatic in his statements that no living person could have entered the laboratory unknown to him. The members of his household were never permitted to interrupt him while certain experiments were in progress.

One Scotland Yard official suggested that the radium tube had probably found its way into the heated crucible, and had become absorbed in the molten mass of mineral substances contained therein. The contents of the crucible had therefore been subjected to a searching analysis without revealing the slightest trace of any radio-active matter.

Gifford Renwick had preferred to let the case rest until it was relegated to the official pigeon-holes to await, with the other forgotten mysteries, the resurrecting trumpet of some unborn genius. In the interest of his employer Renwick had entered upon a series of investigations which, in his estimation, had been left uncovered by the Scotland Yard experts.

What manner of thief, he asked himself, could effect an entrance into a locked laboratory at a time when a very astute scientist was himself the only occupant?

The laboratory was situated at the rear of Professor Moritz's house, and was in no way connected with the main building. The floor was of smooth concrete and free from crevices. There was no possible way of entry by the roof even if Moritz had been absent from the laboratory at the time of the occurrence.

In the adjoining house lived a Japanese doctor, Teroni Tsarka by name, whose fame as a nerve specialist had brought him into public notice.

Renwick had paid some attention to the movements of the Japanese doctor, with uninspiring results. There was little to be learned by casually watching a small, shrivelled Asiatic who rarely ventured out of doors unless in a fast-moving car which allowed no time for personal criticisms or interrogations.

Doctor Tsarka had one daughter, Pepio, a laughing, mischievous girl of eighteen, who ventured abroad with the audacity of an American heiress. Father and daughter had been in England about a year; both were linguists of exceptional ability. It was Pepio's elusiveness which had pointed the young detective's interest in them. Always unapproachable and studiously alert, the laughing- eyed Pepio was usually accompanied by a youth of her own nationality whose name, he learned afterward, was Soto Inouyiti. Like Doctor Tsarka, Soto Inouyiti had attracted public attention by his collection of pictures exhibited some months before at his rooms in South Kensington.

Renwick had shadowed the pair during their daily excursions through the city, only to discover that the love of art and literature was their besetting sin. Soto was scarcely eighteen; a slim, pretty boy with an oval face and skin of a peculiar olive richness.

Their innocent love of pictures and English books was a discovery that in no way coincided with Renwick's idea of Doctor Tsarka's complicity in the Moritz radium mystery. So he relinquished them with a sigh, and on the very day he abandoned his Tsarka theory he met Pepio on the stairs of a reference library in St. Martin's Place.

The stairway was badly lit, and his eye was transfixed by a luminescent ray emitted from a peculiar metal brooch that held Pepio's silk shawl to her shoulders. She passed him very swiftly, and was gone before his mind had leaped back to the main trail.

So he had returned to the office to brood upon the peculiar light emissions which appeared to radiate from the throat ornaments worn by Tsarka's laughing-eyed daughter. What manner of gem was it that could illuminate the darkness of a stairway? he pondered.

Tony Hackett laughed at his prolonged silence, and then very suddenly found himself staring into Renwick's handsome face.

"By Jove, Gif, I really think you have dropped on to something," he broke out. "The last time I saw you so misty about the eyes was when you had the Wilmot boy in your grip—the little wretch!"

Renwick looked annoyed, and the shadow on his brow brought an instant apology from the good-natured Tony.

"I blame you for allowing the young imp to slip away, though," he added, feeling that it was not good to apologize without a shot in another direction.

Gifford's softness of heart was well known among his intimates. It was a fact which had also been noted by various members of the criminal classes, who used their knowledge with craft and circumspection whenever his sympathies were attracted in any given direction.

The Wilmot affair was a case in point. Employed by a firm of warehousemen at an exceedingly low wage, young Wilmot had been drawn by an older clerk into a system of petty pilferings which amounted to nearly a hundred pounds. Wilmot's family were in straitened circumstances, and the boy's borrowings had gone to relieve the sickness and distress which had come upon them through the unexpected death of the father. At the last moment Renwick had neglected to insure the boy's arrest, and Oliver Wilmot had escaped to America, where he was soon in a position to refund in full the amount of his defalcations.

Renwick's act in allowing the boy to elude his employers at the last moment had nearly caused his own dismissal from the service of Anthony Coleman. He escaped, however, with a severe lecture on the sin of aiding young and foolish persons to evade the law's just penalty.

Tony Hackett's words scarcely roused Gifford from his brooding quiet. When he spoke the dream glow of the red fire was in his eyes.

"I've been walking all day," he said without looking up, "tramp, tramp, tramping in the wake of lost ideas until—"

He paused almost sharply as though conscious of his companion's searching glances.

"Until what?" Tony demanded bluntly. "Say on, Renny. Don't stew in your own dream palaces too long."

Gifford was silent for a period of six heartbeats. Then his voice had the weary intonation of an awakened sleeper.

"I met a young lady to-day who has been evading my attentions for some time. I'd fixed on her father as the kind of man likely to have been mixed up in the Moritz case. I've lived near the hem of her shadow for a long time until I was satisfied that she or her people were not the kind I was after. I came upon her to-day on the stairs of a reference library, a pretty darkish place, and I discovered that she was in a highly radioactive condition!"

Tony was not scientifically disposed, and his companion's words fell a trifle short of their true significance. Gifford explained.

"The young lady I refer to has been at close quarters with a quantity of chemical matter, in a laboratory perhaps, and it may have happened that she has been allowed to handle radium carelessly."

"Is this radioactivity easily detected in persons?"

"Yes; it acts like phosphorus in the dark. It may get on the fingers, and, as a matter of course, to the metal trinkets or jewellery worn by the experimenter or thief. It was the young lady's brooch flaring in the dark that caught me."

Tony sighed. "A lot depends whether she or her people have been handling the Moritz radium. If you first suspected her of the theft, and then discovered a radium flare on her person, your inductions are pretty sound. Personally I'd have shadowed her to the skyline on the strength of your clue."

He stared at the brooding boyish face in amazement. "If she's pretty you'll let her go, Renny. But take an old stager's advice and get your friend McFee, of Scotland Yard, to shoot her into clink to-night. It's the chance of a lifetime; it's fame with a big F. Why"—he paused to hammer Renwick's stooping shoulders with his fist—"this Moritz radium case fairly smothered the Scotland Yard people; it created a vacancy in their thinking department and gave their best men a pain in the neck through waiting round corners. Gifford, my boy, don't let this radio-active girl slip through your fingers."

"It will be like arresting a Madonna," Gifford confessed. "I shall have to get it I done though."

"When you grow older you'll be less merciful to thieves and scoundrels," Hackett averred. "So get McFee on the Madonna's trail without delay. It will do you a lot of good with the firm after your—"

"Recent bunglings, eh?"

"Well, yes, Gif. Lately you've allowed a lot of good things to slip past. Lay to your clue and keep your intellect bright."

Gifford sighed as he prepared to depart. "I like theory work best. When it comes to 'putting away' old men and—and children it makes one feel rather lonesome—cowardly almost. Good-night, Tony!"

For a while Renwick deliberated on the wisdom of bringing his friend McFee into his scheme of things. Professor Moritz had come for help to the International Inquiry Bureau, feeling assured that Scotland Yard was treating his story as the result of an overwrought imagination. He desired nothing more than the return of his lost radium. He was the type of man who abhorred criminal prosecutions and the air of police courts.

Therefore, Renwick argued, if it were possible to gain admission into the Japanese doctor's house, he might succeed, after hinting delicately at police intervention and exposure, in recovering the lost radium bulb.

The bluff had worked before. If McFee were introduced, anything might happen. The Scotland Yard man would naturally make the most of his chance. There would be a sudden rush into the house of the Japanese doctor; much noise and tramping of feet—circumstances likely to permit one of Tsarka's people to escape with the precious cache of radium.

In a fraction of time Renwick decided to act on his own responsibility. If trouble arose he might easily communicate with McFee and bring about the Jap's arrest. On the other hand, if his bluff succeeded the radium could be returned to Moritz and things left to take their course. Only he prayed inwardly that the Madonna-faced Pepio would never fall foul of his friend McFee. The big Scotch detective had a freckled skin and the spring of a tiger. No, it would not be good for Pepio San.

Renwick felt the rain sting his cheek as he passed into the street. The lamps shone moon-white through the uprising mists. Shapes flitted past with almost ghostly stealth, while here and there he saw half-dressed waifs crouching in office doorways, baby-like children muffled in rags, the hunger-wolf alive in their wind-purpled faces.

The entrance to Doctor Tsarka's house was lit by a pair of pedestal lamps. A well-kept lawn with a thickset hedge separated it from the road. Gifford had mapped out no particular plan of action, but trusted that some propitious circumstance would enable him to enter the Japanese doctor's house as swiftly as possible. To go in as a patient with a view to a consultation seemed the only way. A moment's reflection, however, revealed the folly of such a proceeding.

Stooping in the shadow of the hedge he waited while the passing minutes lengthened into eternities. The theatre cars sped past in a rapid procession. A glance at his watch showed him that it was past eleven. Pausing near the gate entrance he observed a small Daimler landaulette halt suddenly within a few yards of the pavement. Pepio Tsarka slipped out and passed through the gate before he had recovered from his surprise.

At the first touch of the house bell the door opened smartly to allow her a swift entry. Renwick almost leaped on her heels as she passed in, his shoulder hurling back the door in the face of a slant-eyed Japanese servant.

Pepio faced him instantly, the quick blood darkening her olive cheek. "How dare you come in here!" she flashed. "What is your business?"

"Your excellent parent, Pepio San." He was breathing hard like one who had gained the threshold of a long-desired goal. "A question of his naturalization papers. I would like to see them."

She stamped her foot. "You have no right of entry here. Our Consul shall hear of it!"

Gifford had been loth to force his way into the house of Doctor Tsarka. Yet a hurried glance at the palpitating Japanese girl convinced him that his visit was not wholly unexpected.

Retreating with the servant along the wide entrance hall she stayed in the shadow of a portière, her eyes turned in his direction. He was again conscious of the peculiar light emissions which surrounded her.

"Are you aware, Miss Tsarka, that you are radio-active?" He smiled reassuringly while his left hand closed the house door softly.

She retreated farther, her fingers straying instinctively over the tell-tale brooch. Renwick experienced an unexpected thrill at the strange silence of the house, a silence that closed around him with the solidity of a bank vault. Her voice reached him, but this time he detected a certain malicious merriment in it.

"My father receives visits from many hopeless lunatics. Probably you are the victim of overwork?" she queried.

Her dark, mischievous eyes seemed to reflect the luminescent flow of light from her dress ornaments. Before Gifford could reply a door opened noiselessly at the passage end. He found himself examining a shadowy, bull-necked little man with Japanese eyes and close-cropped head.

He looked once at Pepio and then at the young detective. "You make great intrusion here," he growled. "Say, what heart trouble sends you so late? Doctor Tsarka is indisposed!"

Renwick felt that he had allowed the brooch incident to betray him. His mind leaped to the double as he glanced from Pepio to the scowling Jap, half concealed in the folds of the portière.

"There is no heart trouble," the Englishman assured him with a smile. "It is a question of naturalization. Doctor Tsarka will not object to an examination of his papers."

Pepio spoke three words in the vernacular to the shadow in the portière, then, with a kindling eye, faced Renwick.

"We people of Japan are led to believe that an Englishman's house is his castle. It seems," she added tartly, "that the home of a Japanese gentleman may be invaded at any time by a lot of stupid officials!"

The shadow in the portière beckoned Gifford. "Doctor Tsarka will your questions answer. That girl," he wagged a nicotine-blackened finger at Pepio, "has the devil's temper got. She is the seventh daughter of a learned man. Unlucky as opals these sevenths," he supplemented vaguely. "Come along."

Gifford followed with a dim sense of having created rather an inextricable situation, while Pepio stormed at the doorkeeper for permitting the white man to force his way upon them at so late an hour.

"Come along!" The Jap swung from the passage into another room, where Renwick's astonished eyes fell upon a collection of disused Bunsen cells piled against the wall. A square table filled the centre of the apartment, and on it were littered a number of glass bulbs and tubes containing Magdala red, "thaleen" and hydro-carbon. The walls were covered with Japanese articles of curious workmanship and design. The floor was without carpet or linoleum, and revealed numerous acid stains on its bare surface.

Gifford marvelled now, as he followed the little Jap, that the Scotland Yard officials had allowed Doctor Tsarka's premises to go unsearched. His conductor led him down a flight of stone steps into a garden that faced Professor Moritz's laboratory from the western side.

The air smelt dank and conveyed an impression of vitriol residues and carelessly handled chemical washes. A high wall surrounded the garden, damp and moss-grown where the overhanging trees shut out the windows of the adjoining houses.

"My master everywhere sleeps but in the house," his attendant informed him. "He is troubled with the street noises—the dogs, the newsboys that make disturbance with their face."

"And your master is a prominent nerve specialist!" Gifford laughed as the Jap halted before the shut door of a newly painted outbuilding.

"The physic man is always not a good healer of himself," grunted the attendant. "There are noises in my poor head that he cannot put in tune. In go now and speak of the things that are of great annoyance to you."

Thrusting open the main door of the outbuilding, Gifford entered with his conductor, and his alert senses became conscious of a heavily ionized atmosphere impregnated with the fumes of strong tobacco.

The Jap vanished from his side, leaving him staring into the blackness of the flat-roofed outbuilding. In all his life Gifford had never known fear. He had encountered riverside desperadoes and fleet-footed bank smashers by the score, yet there had never come to him the feeling of unknown terror, which passed like the beating of a vulture's wing.

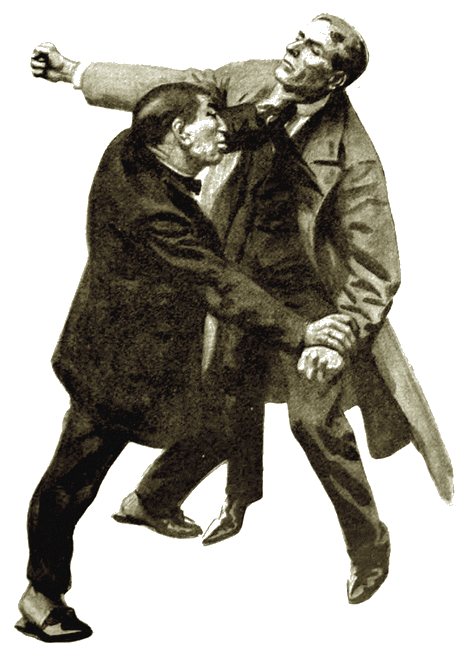

Slowly, imperceptibly he became aware of a face reviewing him almost at arm's length, and then of a huge squat shape that seemed to leap from the ground gripping him by wrist and throat!

Gifford's right fist smashed past the elusive face, and again with trip-hammer force as he sought to beat away the encircling arms of his unseen adversary.

Across the floor he reeled, panting like a lion in the grip of a python. No sound came from either, until a soft spongy mass was pressed over his eyes and quickly withdrawn. A savage grunt of satisfaction ensued; then a door closed on his right, leaving the young detective panting and mystified, unable to comprehend the nature of the mysterious assault.

Across the floor he reeled, panting

like a lion in the grip of a python.

A sudden strain of laughter echoed through the darkness, followed by the unmistakable click of an electric button. Instantly the apartment was inundated with a powerful light that revealed to his astonished eyes an oblong room furnished and upholstered to suit the fancy of a Piccadilly exquisite or art connoisseur.

At the extreme end of the room, beneath a cloudwork of tapestry and screens, stood a scarlet embroidered ottoman with a heavy brass reading lamp at the head. Under the lamp, tucked among the piled-up cushions, lay a small, wizened figure in a yellow dressing-gown. For an instant there flashed upon Renwick all the weird stories of dwarfs and elves he had ever read. The figure on the ottoman differed from the picture-book goblins only in the cast of its features—it was Japanese, and very much amused at the manner of his entry.

"I beg your pardon," Gifford began, bracing himself like one recovering from a severe shock; "the attendant informed me that I should meet Doctor Tsarka."

The figure on the ottoman leaned forward, revealing a pair of narrow shoulders and tight-fitting skull-cap.

"I am Doctor Tsarka. My confrère, Horubu, treated you rather roughly, I fancy," he said in decisive tones. "Horubu is troubled with apparitions. He mistook you probably for an anarchist."

There was malice in the last word, and in the brief pause that followed Gifford studied the capacious brow and rather well- formed features under the creaseless skull-cap. He felt instinctively that he was under the surveillance of a master criminal, a man frail of body, but whose very presence exuded the Titanic energies of his mind. Yet the Englishman, impressed as he was by Doctor Tsarka's personality, could scarcely repress a smile at his diminutive figure and mock serious pose.

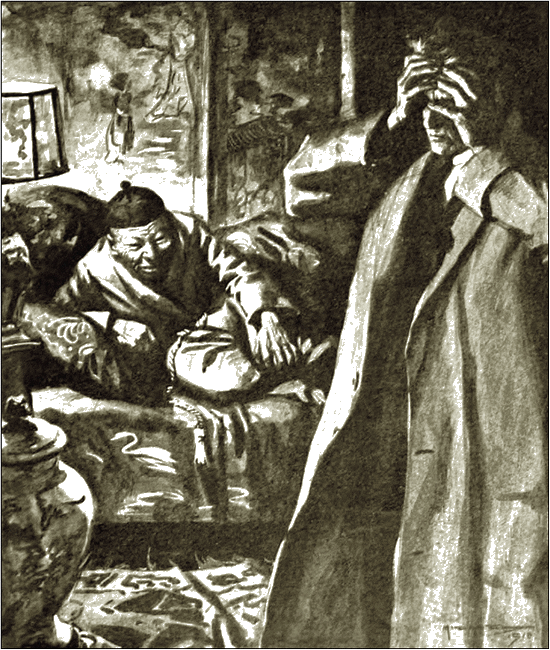

The little doctor interrupted his swift thoughts by rising from the ottoman and assuming a Napoleonic attitude beside the brass reading lamp.

"Your business here is one that might very well have been discussed with my Consul in London. You have committed a grievous blunder, my young friend, a blunder that may cost you many sleepless nights."

Renwick was aware of a slight stinging sensation across both eyes, accompanied by flashes of purple light across the retina. Each attempt to open his eyes was rewarded with a series of needle-like pricks that caused him almost to cry out.

A sigh of regret escaped the little nerve specialist as he regarded the flinching figure before him.

A sigh of regret escaped the little nerve specialist

as he regarded the flinching figure before him.

"You will grow accustomed to the illuminations after a while," he affirmed. "There will be green rays and violet mists; you will also suffer from irruptions of ultramarine. Personally, I can recommend the green rays," he added facetiously. "They suit the complexion of most young Englishmen."

Gifford with a sick taste in his mouth, groped his way to a chair, his left hand upraised to shield his eyes from the penetrating glare of the electric bulb overhead.

"The illuminations are certainly startling!" He spoke huskily, his hand gripping the chair-back to steady his shaking limbs. "May I ask if that sponge affair, that was squeezed over my eyes, contained anything poisonous?"

"My confrère, Horubu, is capable of anything when his liberty is threatened," was the unimpassioned rejoinder. "He anticipated your coming."

Gifford rocked forward, pressed his fingers tightly over his closed eyes as though to stay the flame of torment that seared his optic nerves. It occurred to him that he had fallen among a gang of medical fiends. His other speculations concerning the whereabouts of Moritz's lost radium were obliterated by the curious phenomena of light-rays through which he was passing.

Doctor Tsarka addressed him sullenly. "You came here to arrest me or my daughter, to drag us to one of your beastly gaols. For days past you have followed Pepio San, bribing her chauffeur to slow down whenever you gave a signal from your own car!"

Gifford was considering the slender veins of ultramarine and scarlet that shot across his throbbing brain. Each effort to meet Doctor Tsarka's glance brought fresh stabs of pain, until the apartment seemed to dissolve in a volcano of blinding flame.

There were possibilities in the situation which caused him to ponder helplessly. The thought of blindness left him cold. Men in his profession had been rendered inert by the use of anaesthetics. It had been left to the Oriental mind to invent a new alternative in the way of balking unwelcome investigations.

The little Japanese doctor breathed near his face, betraying a certain professional curiosity.

"The eye of a man is a wonderful instrument," he volunteered. "It deludes the brain and fills the heart with immeasurable joy or torment."

Gifford winced. It seemed as though an eagle's claw had fastened upon his eyes. To move backward or forward became an undertaking of considerable peril. The room had become absorbed in the volcano of purple rays. Only the electric bulb above his head was visible; the figure of Doctor Tsarka was a mere gnome- like blur, a goblin shadow that gesticulated—and smoked a cigarette.

"You were unfortunate enough to walk into my operating theatre when my confrère, Horubu, was conducting an experiment in molecular activity," the little nerve doctor explained. "Your eyes have been filamented. One of these days the light may return to you. Until then your future is at my disposal."

By stretching out his hand Gifford might have squeezed the breath from the imp-like figure beside him. He restrained his desire with an effort, knowing that any attempt at violence would bring a horde of Japanese house-servants about his ears.

The pat, pat, of Tsarka's sandalled feet sounded across the apartment. Then followed the unmistakable sound of a typewriter, and Renwick knew that the little nerve specialist was manipulating the keyboard of an up-to-date machine. It ceased, and he heard the flutter of notepaper at his elbow.

"You will sign this letter, my friend," the little doctor spoke close to his ear. "It is addressed to your employer."

Gifford shrugged. "Read it out," he said huskily.

Doctor Tsarka paused to make a slight correction with his pencil; then in a clear voice read the message:

"Dear Sir—I have stumbled unexpectedly upon a piece of information which may assist in clearing up the Moritz case. The 'clue' is on his way to Paris this evening. I follow. Will wire results in a day or two.

"Yours, etc."

Doctor Tsarka placed the letter in his hand. "Oblige by appending your signature. It may save you from another bombardment of violet rays. Savvy?"

Gifford's fingers closed on the note. Tsarka's first move now was to prevent other detectives following on his heels. He put down the paper.

"I do not feel inclined to sign my own death warrant, Doctor Tsarka. Suppose we allow things to take their course?"

"The course would be distinctly unpleasant for you. Now," the little doctor wheeled upon him suddenly, "you have a friend named Hackett. Does he know that you come here?"

"He may have guessed. We often guess each other's intentions without asking."

"Good; then you must sign. I promise no further harm to you. Yet... By the gods if you do not!" Renwick felt the frail body pulsate beside him as the small, wiry fingers clutched his sleeve.

"Fire away!" Gifford exclaimed passionately. "You have struck your worst blow.' Let the game go on!"

The Japanese doctor retreated, then paused at a distance to contemplate the erect, white figure in the centre of the apartment. The folding-screen at his elbow moved aside; a face pressed into the light and stared with Tsarka at the immobile young detective.

"Go away—thou!" The doctor snapped his fingers at the face. "This affair is mine, Satalaya!"

The face vanished. Doctor Tsarka inclined his head. "Do not drive me to extremes," he continued, addressing Renwick. "I bear you no malice. Put your hand to this paper. The pen is here."

"Do you intend to keep me in this place?"

"You shall be my guest for two days, not an hour longer. If you attempt to leave without permission—"

"Well?"

Doctor Tsarka made a little noise in his throat that was neither a laugh nor a cry.

"Why do you wish to die unpleasantly?" he asked after a pause. "It is not heroic. If I struck you with half a million volts no one would hear a noise. Be sane; there is no audience here to applaud your determination. Take this paper and sign!"

Renwick remained standing in the centre of the apartment like one counting his own heartbeats.

"I want to ask you, Doctor Tsarka, whether this," he touched his eyes suggestively, "is a mere illusion or a total eclipse of the vision? Does it mean blindness for me?"

"It is not an illusion," was the swift response. "You will henceforth walk in darkness unless certain remedies are applied within a few days."

Gifford nodded, and then, clearing his voice, spoke again.

"What do you mean by certain remedies?" he questioned. "An ordinary oculist could repair the damage—don't you think?"

Doctor Tsarka salaamed facetiously to the half-blind figure before him. "There is only one person in England capable of rendering you service. She is a student of the new science of radio-magnetics."

Again Renwick nodded. "So, unless I sign this letter, you intend keeping me here until I am past hope?"

"Sign it!" came sharply from the Japanese doctor. "We people of Nippon love brave men; the stupid ones we adorn with asses' ears!"

"Give me the paper, and guide my hand, O man of little iniquities!"

He thrust out his fingers with a blind gesture.

Doctor Tsarka guided his hand over the paper, and after scrutinizing the signature, carefully placed the letter in an envelope. With scarcely a sound he moved toward the maze of screens and slipped from the apartment.

A GREAT silence fell over the apartment, and Gifford waited, like a trapped lion, for something to move toward him. In his experience of London's Asiatic criminal population, he had encountered nothing which destroyed his self-control so completely as the momentary pressure of Horubu's radium-sponge, for he was convinced now that the Jap had manipulated some radio- active substance during their short wrestling bout.

The question of his mission to the house of the Japanese nerve specialist vanished at the thought of his peculiar predicament. Of the misfortunes which afflicted mankind he dreaded blindness most. He barely restrained himself from crying out as he listened for a sound to penetrate the stillness of Doctor Tsarka's operating theatre.

During those waiting moments Gifford's despair was very real. At the outset of his career he had been practically struck down by a hand skilled in the deadly uses of radio-surgery. His blindness might be transitory, or it might walk with him through life. And he had looked forward to a career which promised enduring rewards, for to him the suppression of criminality had become a religion into which he had plunged, giving heart and brain to the service.

His father, a retired army captain, had died, leaving an encumbered estate and a wife whose early training unfitted her for the strife of existence. So Gifford had taken up the burden, in his twenty-second year, determined to win for the gray-haired mother competency and respite from life's daily struggle. Failure, white and pitiless, had leaped to meet him. The unravelling of the Moritz radium mystery, which had already blighted the careers of several Scotland Yard experts, had caught him in its toils.

Gifford's desire to recover the lost radium tube had been kindled by the fact that Professor Moritz was labouring to abolish the most dreaded of human scourges. He was aware that Eugene Moritz could never replace the precious material which had contributed so vitally to his researches.

Doctor Tsarka returned unexpectedly, his slight frame palpitating with good-humoured excitement.

"Now that your letter has been posted, Mr. Renwick, we may assume a more hospitable attitude."

Reaching a cigar box from a near shelf, he proffered it with a smile.

"You will find them excellent for the nerves," he vouchsafed; "although scientists have not yet proclaimed tobacco an antidote for radium poisoning."

Gifford accepted a cigar and half stumbled into a chair, while the knife blade sensation in his temples soon gave way under the soothing influence of the weed.

Doctor Tsarka contented himself with a gold-tipped cigarette. Lying back on the ottoman he regarded Renwick smilingly.

"I am sorry that my confrère subjected you to the sponge. You will understand that his action arose from a desire to protect himself and me from the police."

"It was my duty to investigate and bring about an arrest if possible," Gifford admitted.

The Jap laughed easily, while the slow-lifting smoke oozed from his lips.

"You came for Moritz's radium, and you received a few filaments through the nerve passages of your eyes."

Gifford barely repressed himself. "Why, you admit that it is in your possession!" was all he could say.

Tsarka twirled his cigarette between his finger and thumb until it resembled a fiery wheel.

"You will spend your life in proving the fact," he purred. "Yet Horubu used it to advantage."

"In blinding me!" Gifford affirmed. "It was a noble thought, Doctor Tsarka!"

"It was certainly a dramatic one." The little Japanese specialist manipulated his fiery wheel with impish dexterity. Not for an instant did his eyes wander from the crouching figure in the chair.

"We Japanese take no chances in life," he went on. "At the first sign of the tiger's claw we strike—hard!"

Gifford sighed. "Please regard me as a paper tiger in future," he said with a touch of bitterness. "The real article would have shot you and your sponge-waving Horubu at sight."

An outburst of merriment greeted his words. Tsarka, in his exuberance, kicked his sandalled feet against the ottoman, while the skin of his face creased like hammered bronze.

"You have emotion, but no head balance, Mr. Renwick. It is well that you did not attempt violence."

A shadow crossed his face, a livid hatred that was gone in a breath.

"Some of us prefer to die out of prison," he went on. "Horubu and myself are taking no chances."

Gifford smoked in silence while the knife-stabs in his temple grew less deadly. The Japanese doctor's strange admissions puzzled him. It was seldom that an Asiatic implicated himself voluntarily. But the young detective knew enough of the Oriental mind, its vain inconsistencies and deceits, to attribute much importance to Tsarka's gratuitous statements.

He was not disposed, however, to stem the tide of information which floated oil-like from the little man's lips.

He leaned from his chair, his left hand drawn across his eyes. "Doctor Tsarka, let me frankly pay tribute to your genius and knowledge. When a foreigner manages to baffle the combined wits of England's criminal investigators, one has to pay homage."

His shot appeared to kindle Tsarka's dormant vanity. The little man gestured with his cigarette.

"I have been amused by the attitude of Scotland Yard in regard to the Moritz case. That some of its officers are stupid goes without saying."

"You have been very clever," the Englishman admitted, "to drive to the verge of distraction the most brilliant men of our time."

"We succeeded, Mr. Renwick, because you men have no imaginations. They go to work like blacksmiths seeking to disentangle a handful of gossamer threads. Listen!"

Something warned Gifford that the Japanese doctor was in the humour for disclosures. He smoked furiously, scarce daring to interrupt the thread of the little man's discourse. With all his silence and duplicity Doctor Tsarka's pulses throbbed for the Englishman's praise. In the security of his own house his Asian vanity leaped and cried for applause.

"You English are very clever; you are big and brave; you go to war like lions with unbroken teeth, but," he lay back on the ottoman, his eyes glinting in suppressed merriment, "you have no imagination. You have not learned to think as little children think. If you see a daisy in the field it is only a daisy to you —nothing more."

"What would you call it?" Renwick interposed.

Doctor Tsarka shrugged. "To the eye of the child it may be something more—a fairy's cap, or a drop of gold in the eye of a waking elf, but it is never a daisy. We Japanese are not grown up. To us the 12-inch gun is still a dragon of war, ready to thunder its message of death at the enemies of our people. And so, when we bring our child-brain into our schemes we leave an institution like Scotland Yard agape at what they are pleased to call an unfathomable mystery."

Gifford yawned a trifle wearily. He had expected more from the little doctor. "The mountain rumbles and the mouse comes forth," he said in his disappointment.

"No; a rat!" Tsarka chuckled audibly, and again the cigarette became a wheel of fire between his nimble thumb and forefinger. "It was a very small rat that broke the hearts of a score of London's most brilliant detectives when they sought to elucidate the Moritz mystery," he continued.

"On the day that the Professor acquired his six grains of radium the newspapers informed us of the circumstance. For more than a year I had followed closely the results of his experiments in cancer research. It was an open secret, too, that Lord St. Ellesmayne, President of the Cancer Research Society, had presented him with the radium. Well, to be frank with you, I Wanted those six grains of radium to complete a little experiment of my own. I could not afford, however, to put up the sum of money required for its purchase. The fact that my house adjoins Moritz's, and that his laboratory stands within twenty feet of this apartment, set me thinking how I might borrow the whole of the precious radium without his knowledge."

Doctor Tsarka paused to light another cigarette, and the match-glow illumined his eyes with a peculiar metallic brilliance.

"Now we come to the Japanese child intelligence when it is directed against an apparently impossible task," he continued. "A thought came to me that was suggested by the reading of one of Narcrissino's fables—the Japanese poet of the Seven Lakes. It was the story of the Dragon and the Rat. Mentally, I put Moritz in the Dragon's castle because he held the flaming witch- fires I so badly needed for my own experiments.

"Horubu, after much worry and expense, obtained a plan of Moritz's house from the architect who built it. It enabled us to study it carefully, and we found that it would be impossible to enter his laboratory without killing every member of his household and leaving traces of our presence everywhere around. So we studied his drains and brought little Kezzio into the game."

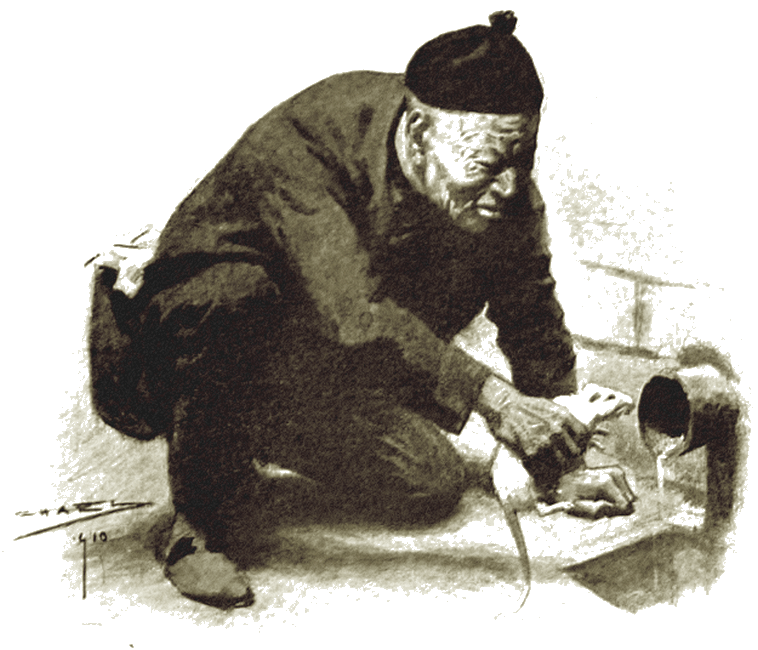

"Kezzio?" Renwick leaned forward toward the ottoman. "Who is Kezzio?" he inquired innocently.

Tsarka's eyes were pinched to narrow slits of light as he responded:

"Kezzio is the white rat from Nagasaki. It was given to me by a worker in magic named Sere Sani."

Renwick peered forward in astonishment. "You, Tsarka the scientist, talk of workers in magic!"

"Sere Sani was a harmless fellow," Tsarka continued unmoved, "with his gilt paper wands and the medicated flower bulbs which grew while you waited. We took the rat Kezzio, because it had the brains of a man-child and the tricks of a sewer thief.

"It learned more tricks from us after we had studied the water pipes leading from Moritz's laboratory. Horubu discovered that they joined ours where the house wall and the garden meet. My pipes reach my neighbours on the right, Moritz's meet ours on the left.

"All his residues and chemical washes ran through our garden drain. An idea came to me, one day, when I opened the drain to analyze his runaway washes. Like Madame Curie, I was anxious to know what my brother scientist was throwing away. I picked up several large pieces of nickel salts, and from these I gathered that his sink pipe had no screen. And so the thought of sending Kezzio into his laboratory, by way of the sink pipe, came to me."

Renwick half rose from his seat and then sat down abruptly. "The thing is childish, absurd!" he muttered under his breath.

"Moritz had regular working hours," Doctor Tsarka went on, with a placid smile in Renwick's direction. "From experience we gathered in many English laboratories, we felt confident that the glass tube containing his radium supply was constantly at his elbow.

"We had a large working model of his laboratory, and we knew from his shadow near the barred window that he conducted most of his experiments on a marble-faced bench that stood against the wall. Beside it was a white stone sink fitted with hot and cold water taps.

"Well, we began by sending Kezzio up the model pipe to the marble-faced bench that represented the exact spot where Moritz placed his radium tube whenever he crossed the laboratory to answer a call at the telephone.

"At first Kezzio did not like the wet journey up the pipe. A little starving and coaxing made him alter his mind. In less than a week he began to understand something of his task."

"Task!" Renwick allowed the hot cigar ash to fall on his knee. "Surely you do not mean—" He paused as though a blade of light had entered his throbbing eyes, both hands pressed over his brow. "Go on," he ventured in a steady voice. "I beg your pardon, Doctor Tsarka."

The little specialist nodded amiably.

"We taught the rat to pick up a glass tube that held a few sparks of phosphorus, and return with it down a curved pipe. To you the trick may seem foolish and incredible, having a thousand chances of failure against it. But we Japanese are a patient people, and there is not a trick on earth that a well-trained rat is not capable of attempting. Rodents have carried off diamond rings and bracelets from the dressing tables of the rich. History is strewn with stories of jewel thefts perpetrated by mischievous house rats whose love of bright objects is keener than most women's."

Doctor Tsarka paused to hug his knees as the thought of his daring experiment thrilled his blood.

"Few men ever played with the brain of a rat as we played. How many have studied the ordinary rat's capacity for trick work as we Japanese? The brain of a healthy rodent is as impressionable as wax or gold; it is quicker than a dog to understand, and, above all other living animals, it possesses an innate love of bright metal and glittering objects. Kezzio, after a few days' practice, would pick up a glass tube of phosphorus and carry it down a wet pipe at a signal from me or my companion, Horubu.

"Only by Moritz's shadow crossing the window could we see when he was at work. We were just a bit afraid of his chemical washes coming down the pipe, for we did not care to send little Kezzio to his death. To be caught in the drain when Moritz was throwing out cyanide water or a solution of sulphuric acid would have been a very unpleasant experience for the rat.

"Moritz's telephone cleared the way. If we could keep him talking a while with his face from the marble-topped bench, Kezzio would have a chance of proving his worth.

"On August 18th, about eleven o'clock in the morning, Horubu rang up Professor Moritz from the British Medical Institute and held him in conversation for several minutes. Horubu had been reading up Pultowa's book on radio-magnetics, and he was able to interest the professor on the light energy of disintegrated molecules.

"I became aware of Moritz's presence at the telephone through the medium of an electric appliance which notified me from one of my own wires.

"I was sitting in the garden, near the severed drain pipe, with Kezzio held in my right hand. There had been a slight flush of water a few moments before, but I trusted that no more would come down while Moritz was at the receiver.

"The rat seemed to understand my intense anxiety as I knelt by the open pipe. Its ears went back and its eyes turned to me bright and questioning. 'Up, little man,' I said, and thrust him into the pipe.

"The rat seemed to understand my intense anxiety as I knelt by the open pipe."

"You may think it was a silly experiment, the result of an opium dream, or childish fancy; but we Japanese are only children, and we sometimes accomplish the incredible by our passionate interest in everything we undertake.

"Kezzio was gone not more than thirty-five seconds when his wet nose came pointing from the pipe end. Something was wrong, and the priceless moments were flying. Horubu could not keep Moritz at the telephone a minute longer. I looked quickly at Kezzio and saw that its paws were burnt with acid residues. Dipping them in oil (it was ready at my elbow), I wiped the tiny claws swiftly and with a tweak of the ears sent it into the pipe.

"I was hopeful that Moritz would not return from the telephone, for I knew that his approach would scare Kezzio from the laboratory. I received a signal from one of my assistants, posted at the upstairs window, telling me that the professor had hung up the receiver and was about to return to his work.

"Kezzio's burnt feet had spoilt our calculations I felt certain. Kneeling on the ground I peered into the severed pipe and waited. The pipe was quite black inside and smelt strongly of nitrate solutions and bitter chemical residues. As I looked within I saw a strange thing. From the darkness there came a burning star of light that glowed in the damp drain with the power of a live sunbeam. Never before had I seen so curious a spectacle as this starry flame that came foot by foot toward me. It was Kezzio, and the little fellow tumbled into my hand with six thousand pounds' worth of radium. The glass tube that held it was hardly bigger than your finger."

Renwick's head had fallen forward during the latter half of the Japanese doctor's story. His half-smoked cigar smouldered on the ash tray beside him. Tsarka eyed him sympathetically, then rose suddenly from the ottoman and touched the bent shoulders.

"You had better rest a while. After all my narrative has only bored you. There is a comfortable room adjoining this one. My servant will show you the way. Sleep a little. To-morrow you may feel better."

Pressing an electric button in the wall he returned with a sigh to his couch.

Renwick strove to clear his brain from the clouding effects of the cigar. "Your rat story would read well in a child's picture book, Doctor Tsarka," he said with an effort. "One could scarcely expect a man of the world to believe it."

"Will your employer believe your story of Horubu's radium sponge when you return to him?" Tsarka faced him with the agility of a dancing master. "Or will he interpret it as an effort on your part to achieve a little newspaper notoriety?"

The young detective winced. "A man does not blind himself to earn a few press notices," he retorted. "The world would certainly smile if I submitted your rat and water-pipe episode for judgment."

"You—you consider it a little too Jappy?" the doctor queried. "Well, so be it. Scotland Yard has yet to put forward a saner theory concerning the theft of Moritz's radium. Try a good sleep. I will not bore you with my silly stories in future."

A coolie servant entered, and at a nod from his master conducted Renwick into the adjoining room. The windows opened upon the high-walled garden below, and Gifford felt the night air blowing in from an overhead fanlight as he moved forward gingerly. Without a word the coolie locked the door from the outside, leaving him standing in the centre of the apartment.

Groping right and left he discovered a small table and chair near the window. In a far corner was a small camp bed that smelt of stale cigars and strange clothing. A carafe of water stood on the table; he drank greedily and spilled a little on the cloth before he was aware of the fact.

The water revived him and set him thinking of his helpless plight. Setting out only a few hours before with the determination to solve the Moritz radium mystery he had fallen an easy victim to Japanese art and trickery. His credulity had been tested to the utmost by the little doctor's astounding confession of the theft, together with his weirdly fascinating account of the rat's entry into Professor Moritz's laboratory.

The coolie servant returned with some food which Renwick put aside, contenting himself with a single cup of coffee. He slept a little, and woke with the booming of a church clock in his ears. He was also conscious of a presence in the room of a soft-footed shape breathing near the doorway.

"Who are you?" he called out. "What do you want?"

"I came to look at you. I could not sleep because I feel that something has happened. Are—are you hurt?"

It was Pepio's voice. He sat up on the camp bed striving to pierce the velvet darkness that surrounded him.

"Your people dealt very promptly with me," he confessed grimly. "They took everything except my life."

"Horubu would have killed you only for my father," she whispered. "What miserable destiny brought you here?"

He caught a faint sobbing in her voice that struck like steel upon his nerves. "Destiny had nothing to do with it," he answered bluntly. "It was my business."

He felt her moving nearer, nearer, until her laboured breathing sounded almost in his ear. Some strange emotion was upon her, he felt certain, the curiosity of the gaoleress to gaze upon the prisoner. An aroma of violets and mignonette swam with her; the tinkle, tinkle, of her gold wrist ornaments was an epic in the silence.

She paused near him, breathing quickly. "Something is wrong with your eyes," she whispered. "You—you are not looking at me!"

Her voice held a peculiar childish sweetness and innocence, but the note of terror in it leaped at him with the precision of a death warrant.

He put up his hand awkwardly as though he would brush away the envelope of darkness that cut him off from the world.

"A touch of radium blindness," he vouchsafed. "You know it was that fellow Horubu, as you call him, put a sponge over my eyes." He lowered his hand mechanically. "Did you turn on the light?" he asked.

Her answer was not very clear to him. As far as he could judge she was standing somewhere in the centre of the room, and the moments seemed to pulsate between her childlike sobbing.

"I am so sorry; oh, so sorry!" The silence fell again leaving him wondering whether the daughter of Teroni Tsarka was really in league with the gang of Asiatic ruffians who appeared to swarm about the house.

"When I have an enemy," he spoke through his shut teeth now, "I shall pray for him to descend into this inferno of colour where red rays cannonade the nerves like grape shot."

His face turned upward suddenly. "Pepio Tsarka," he asked hoarsely; "is there a light in this room?"

"Yes." Her answer came with a sob. It was inconceivable that this Japanese girl should feel sorry for him. An hour before he was ready to arrest her on a charge of theft. It was humiliating to be wept over by the daughter of a professional burglar (he could not regard Doctor Tsarka in any other light). His breath came quickly as he turned to her again.

"Tell me, Pepio San, do you know anything of a—a rodent called Kezzio?"

The sobbing ceased instantly; he heard again the quick movement of her gold wrist ornaments as though her hands had come together suddenly.

"A white rat," he urged with a suppressed grimace, "that enters people's houses by way of the sink pipes?"

"My father keeps one," she admitted frankly, "and its name is Kezzio. I never heard of it entering any one's house though," she added innocently.

"Thank you, Pepio San. It was very foolish of me to come here. Now," he paused again, his lips parted good humouredly, "can you tell me, Pepio, whether my life is safe here?"

"Are you an Englishman, afraid of death?" was her unexpected query.

Renwick's unsuppressed mirth betrayed his boyish nature. "When I am as old as your father, Pepio, I shall probably welcome it. But at twenty-three I am interested in life. I have work to do. Also, if I may mention it, Pepio San, I am vastly attached to a little white-haired Englishwoman about sixty years of age."

"Your mother?"

"Yes, Pepio, my mother. She is a very particular little person, and would resent any one taking my life."

"Some one else cares besides your mother?"

"I think not, Pepio. In England we cleave to our parents, as you cleave to yours."

"Then you are not rich enough to marry?" was her next question, "And so you cling to your mother."

"Exactly; but there won't be any more clinging, Pepio, if I'm carefully garotted or bow-strung during the night. What do you think?"

She retreated to the door without responding. A voice was calling her in the passage, a deep-throated voice that sounded like some terrible echo from a forest.

Renwick strove to make out the strange volley of oaths that followed the young Japanese girl as she hurried away. The heavy footsteps halted at his door, he heard the key turned savagely in the lock, accompanied by a string of ferocious remarks uttered in Japanese. The heavy feet tramped away and as he listened he caught the sound of Doctor Tsarka's voice remonstrating with his daughter for daring to visit the man whose presence in the house had threatened their liberty.

DURING the night Renwick was kept awake by the sound of men's feet in the passage, accompanied by dragging noises suggestive of heavy furniture being removed to a van in the street. Toward daybreak he fell into a sleep that was disturbed by the occasional slamming of a door or the dropping of some metal utensil on the stone floor outside.

He awoke with a bitter taste in his mouth, a splitting pain over the eyes as though a sharp-bladed instrument had penetrated to the nerves. A glass of water from the carafe steadied him slightly. Groping his way to a chair he listened for some indication of life about the house, his mind obsessed by the curious experience of the last few hours.

Something of the city's stir pierced the heavy walls of his apartment, the unmistakable roar of motor traffic, the far-off whistle of a passing locomotive. Sound did not easily traverse the long corridors leading to Doctor Tsarka's sleeping quarters. The rear part of the house descended twenty feet below the level of the street. The garden itself was a mere grassy, well-like enclosure. All thought of breaking from the house had been abandoned by Renwick the moment his sight had failed.

Given a possible chance he would have fought his way into the road, at the outset. No chance had offered. The trained dependents of the little Japanese doctor had not thought fit to relieve him of his revolver. In the house of an enemy a blind man becomes less menacing than a beetle or garden tortoise.

Renwick could only fret and grope his way from window to table, pausing at times to listen for a footstep in the passage outside.

He had hoped that Pepio San might return. Even her voice was better than the terrible silence. He was just beginning to realize the effects of the radium sponge. Complete darkness assailed him. The faint nimbus of light which had penetrated the black void had vanished utterly. He had only the Japanese doctor's assurance that a genuine specific for radium blindness existed. But deep in Renwick's consciousness was the fixed idea that the sponge-wielder had dealt with him finally. There would be no resurrection from the awful pit of gloom into which he had been cast. The Japanese gang of thieves had made sure that he would never appear against them. It would be left to Tony Hackett to follow where his investigations had ceased.

The sound of a broom in the passage sent him to the door listening eagerly. Nearer came the sound until it stopped at Doctor Tsarka's room. A pail was banged heavily on the floor. Then a key was thrust into the lock of his door and opened briskly.

Renwick stepped back, his guard arm raised slightly. "Who are you?" he asked hoarsely. "Are you Pepio San?"

The intruder breathed warily as though the shock of meeting was quite unexpected. It was a woman's voice that spoke, a brogue-mellowed voice that eased the strain on his mind.

"Shure I came to clane up the empty house, sorr. I'd no idea there was a gentleman insoide."

There was no doubt in his mind concerning the personality of the visitor. He had met the London house-cleaner and charwoman before. He took a step to the open door, scarce believing his senses.

"I want to go from here," he said quickly. "The late occupants have taken everything from the house I suppose?"

"There's not a stick left but what stands in this room, sorr. 'Tis yourself that looks sick an' troubled, if I may take the liberty of sayin' it."

Renwick felt called upon to explain his presence in the empty house. A sudden step forward brought him with a bump against the passage wall. He turned, swearing a little under his breath, in the direction of the charwoman's voice.

"I met with an accident here last night. Perhaps"—he searched his pockets and drew out a half-crown—"perhaps you would be good enough to lead me to the street. My eyesight is not very good to-day."

A faint gasp of surprise greeted his admission. The charwoman's broom fell to the floor instantly. Her hand sought his sleeve and drew him along the passage into the garden toward the house. They passed up the steps through the glass-roofed conservatory where he had noted the rows of chemical jars and glass bulbs. The air of the street blew upon him the moment she opened the front door. He halted on the steps uncertainly like one afraid to plunge unescorted into the maelstrom of London traffic.

He turned to the breathing figure beside him, a final question on his lips. "Did you see Doctor Tsarka go from here?" he asked.

"No, sorr; 'twas the house agent, Mr. Jenner, that sent me here."

"But the house was only vacant this morning." He fingered his watch chain undecidedly. "Mr. Jenner did not lose much time in sending you to clean up," he added with a touch of suspicion.

"I was cleaning the front of the house all yesterday," came unexpectedly from the Irishwoman. "'Twould have been small trouble to let you out, sorr, if I had known."

Gifford held himself a trifle desperately. "To-day is only Thursday!" he broke out. "I came in here last evening, Wednesday, just before midnight!"

The charwoman laughed in spite of herself. "Askin' your pardon, sorr, the day is Friday. 'Twas an egg I had for breakfast instead av me usual rasher av bacon."

Gifford gestured impatiently. "Call a cab; there should be one at the street corner."

Stumbling down the steps he waited, chafing at each moment's delay, until the charwoman succeeded in hailing a taxi. With the driver's assistance he gained a seat, and was soon on his way to his employer's office.

He could not conceal his disgust at the inexplicable passage of time. His exhausted nerves had no doubt succumbed to the shock of the radium sponge, or it may have been that some unknown drug in his coffee had contributed to his long sleep.

Arriving at the office, the chauffeur assisted him to alight. The voice of Tony Hackett was heard singing on the stairs as Renwick stumbled into view. No one had ever met Tony on the stairs without hearing the latest music-hall ditty warbled in a soft, tenor voice. The song ceased in mid-octave as Renwick halted, groping on the stairhead, and changed to a whistle of surprise.

"Drunk, by Jove!" Tony's hand closed on Renwick's shoulder and drew him unceremoniously into a side room. "Where have you been? Man alive, you are not going into the chiefs room in that state!"

Renwick's appearance warranted Tony's suspicions. The unshaven face, the tight, pain-drawn mouth and, above all, the half-closed eyes that bore a curious silver scar across the lids.

Hackett caught his breath sharply.

"What is it, Renny? Something whipped you over the eyes?"

Renwick steadied himself with an effort.

"I blundered into a crowd of Japanese nerve-tappers. They fixed me up for two nights and got away. I want to see the chief. Pass me in, Tony."

Anthony Coleman, the head of the famous detective agency, received the young man with the customary nod.

"We understood that you had gone to Paris," he said briefly. "You seem to have been in trouble." He made a gesture to the stooping figure before him. "Sit down."

Renwick groped to a chair, his radium-seared eyes turned toward the grizzled man with the authoritative voice. Briefly enough he outlined the cause of his absence, embracing, in a few short sentences, the story of his experiences in the house of the Japanese nerve specialist. Anthony Coleman listened pensively without exhibiting the slightest trace of surprise or emotion. His steely eyes flashed once or twice during the short narrative, while his fingers wandered from time to time toward a pigeon-hole in his desk where the name Tsarka had been indexed with a number of others.

"Your impulsiveness has not increased our chances of getting this nerve quack," he vouchsafed at the conclusion of Renwick's story. "The radium thieves are probably now on their way to America. So much for personal initiative," he snapped.

Thrusting a handful of papers into a near drawer, he permitted himself a close survey of the young man who had failed after so much brilliant theoretical work to bring the Moritz case to a close.

"Are you quite blind?" he asked. "Can't you see anything?"

Renwick shrugged a trifle wearily. "I fancy my working days are over, sir. I am sorry you are disappointed with my work. Things do not always come into line when we expect them; leastways, the Japanese won't," he added grimly.

Anthony Coleman shifted uneasily in his chair. "I think you had better consult an oculist," he said, with a side glance toward the door. "I'll ring up Sir Floyd Garston. He does a lot of work for the Scotland Yard men. Get a cab and," he glanced again at the stooping, gray-faced young man in the chair, "and pull yourself together, Renwick," he added, with a shade of pity in his voice.

Outside, Gifford was taken charge of by the irrepressible Tony Hackett. As they descended the steps together the cherubic little detective drew a letter from his pocket and placed it in his companion's hand.

"I got it from the office rack," he explained, "and thought of posting it to your mother. Funny writing, isn't it?" he commented innocently.

Gifford fingered the envelope, a curious smile breaking over his parched lips.

"Read it, Tony; I haven't the faintest notion who it's from."

Tony eyed the scrawled missive and read it with frequent pauses.

"Dear Friend:

"I promised you a physician who would repair the damage inflicted upon you by my attendant, Horubu. You will find her at No. 11 Huntingdon Street, St. James'. By going elsewhere you waste the precious moments upon which your absolute recovery depends. The name of the physician is Madame Messonier. She is skilled in radio-magnetics, and is the only person in England capable of repairing the injury inflicted by my impulsive confrère.

"Teroni Tsarka."

Hackett placed the letter in Gifford's pocket carefully.

"That man has the impudence of a rhinoceros," he declared. "If

ever I get on his trail I'll steady his nerves with a dose of

salt and gunpowder—the little beast!"

On their way to Sir Floyd Garston's, Renwick detailed his experiences with the Japanese nerve specialist, while Hackett listened, his face to the window of the fast-moving car. He waited until his companion had finished his description of Doctor Tsarka, together with the account of the rat episode. Then Tony screwed up his lips and controlled the desire to laugh in the face of his friend.

"Those Japs have been guying you, Renny!" he declared. "But this Doctor Tsarka is rather a difficult kind of a blackguard to deal with. There are not many of his kind within the metropolitan area, I hope."

Renwick was silent as the car threaded its way through Whitehall into Trafalgar Square. The driver pulled up at the address given by Hackett and, without further ceremony, the two men entered the house of the famous oculist.

Anthony Coleman had evidently notified Sir Floyd Garston, for, after the briefest interval, the eminent oculist joined them in his consulting room. A thin, hawk-faced man with an abnormal chin and brow, he appeared interested in Gifford's recital of his encounter with the radium thieves.

The silver scars on the young detective's eyelids were subjected to a searching examination. Gifford could only feel the great man's presence as he sat still in the revolving chair, the pliant fingers that tilted his sightless face into strange light- catching angles while certain mirror-lined instruments focussed the retina of his eyes.

A great silence leaped between physician and patient, a silence that was charged with life and death for Gifford Renwick. His mother had not yet been notified of his adventure. She still believed that he was pursuing his vocation in the City. His absence from home would in no way disconcert her, since his business often took him across Europe at the most unexpected periods.

A great silence leaped between physician and patient, a silence

that was charged with life and death for Gifford Renwick.A great silence leaped between physician and patient, a silence

that was charged with life and death for Gifford Renwick.

It was the picture of this gray-haired mother that filled the black chaos of his mind. He wondered, in the waiting silence, whether they would lead him to her a stricken and hopeless derelict, or whether he would return to her roof erect and with hope in his heart.

Sir Floyd Garston remained somewhere at arm's length, a tiny steel-clad mirror in his right hand. His voice was soft, yet in the first syllable that escaped him Renwick experienced a sick, frosty feeling.

"What you have told me is truly remarkable," he began suavely. "There are indications of some radio-active agency on your retina; indeed," he breathed guardedly, as though weighing carefully the effect of his statement, "one is compelled to admit that some poisonous radio-active substance has entered the eye itself. The lids do not appear to have afforded the slightest protection."

"It—it burnt like the devil!" Renwick spoke through his shut teeth. "Do you know much about this radio-active element?" he hazarded bluntly.

The physician's words came more distinctly, Gifford thought, and it set him wondering whether his question had outraged the great specialist's dignity.

"I—I mean that it is such unknowable stuff," he added. "No one has yet declared anything about its generative qualities."

He felt Sir Floyd's hand on his brow, and then the cool, pliant fingers on his abnormal pulse.

"One must not press too closely," the physician murmured. "I am not concerned with any radio-active theories. A general diagnosis of its effects are sufficient in the present instance."

"You think?"

"Ah, we must have patience. Nature is a wonderful restorer if one has command of one's self."

"About a year you think?" Renwick felt the powers of darkness closing around him; tasted of those brief moments the savage despair of the living death to be.

"One does not care to predict," Sir Floyd responded. "Still, I shall be glad to recommend you to an ophthalmic hospital. Your case, I fear, will need patience and courage. The soldier must not quail under the knife," he added, pushing aside his instruments.

"One must attain a little of the philosophy which raises men above the assaults of pain and death."

Gifford groped for his hat in the hall, and out of the darkness around him he heard his mother's voice calling. He half turned to mutter a few words of thanks to Sir Floyd, then, with a sick, lonely feeling, surrendered himself to Tony Hackett.

"Why you're not well!" The little detective held him in the hall with more than brotherly tenderness. "Heard something nasty, eh, Renny? Come outside; the air of the street is better than the perfumes of these execution chambers."

Renwick was not given to violent attacks of self-pity, but down to the roots of his manhood he felt an unspeakable horror of the shade.

Patience and courage! Sir Floyd's words were the stock phrases of every baffled surgeon and specialist. What courage could keep him from the gulfs of despair; what patience smooth a life of blindness and premature decay?

Tony spoke words of consolation as they gained the waiting car.—"Don't worry about Garston's verdict, my boy. He's pretty old when you look at him closely. Let's take a trip to the infirmary; the doctors there will fix you up."

Renwick put up a protesting hand. "Not to an infirmary, Tony. I couldn't stand that!"

"Why?" Hackett's hand fell from his shoulder; he stared blankly at the scared face of his friend. "It's the best place for you now, Renny. They'll do their utmost. There's nothing between the infirmary and going home to mother," he added with a shrug. "You won't go home until the London hospitals have turned you down."

Gifford raised his head with the jerk of a lashed steer. "We have Madame Messonier," he said huskily. "One can never tell."

"A damned quack!" Tony exclaimed. "I'll bet she hasn't a diploma to fly with!"

"I won't go to the infirmary!" Gifford insisted. "It is full of blind people. There are ghosts of the dead inside its walls. I should meet and touch other blighted souls like myself. I won't go there, Tony!"

Hackett swore under his breath, and spoke to the chauffeur. "The Messonier Institute, No. 11 Huntingdon Street. We'll see what the lady is like, anyhow."

THE Messonier Institute stood out in white relief against the gray-faced hospital adjoining. Within its spacious consulting rooms were suites of sea-green velvet and amethyst drapings. A liveried servant carried Gifford's card through a labyrinth of mirror-panelled apartments and returned with the intelligence that Madame's hours of consultation were limited to the early morning only. She would not, therefore, see any one.

"Be good enough to inform madame that I came at the request of Doctor Tsarka."

The attendant again departed with his message, leaving him in a state of nervous expectation.

"This Messonier woman is worth watching," whispered Tony Hackett to Gifford. "If she is in touch with Tsarka we might nab him."

Gifford sighed wearily. Only one thought lived in him now—to break through the mountainous walls of darkness and gain the light of day, to become a living entity and not a human mole.

The attendant returned full of apologies, but still austere. Madame was at that moment conducting an experiment in radio- magnetics. She could not possibly see them for another hour.

"Sounds callous and stiff-necked," Hackett growled. "If we were a couple of dukes," he added facetiously, "her ladyship would come to us in a purple flying machine, I'll wager. Deuce take the woman doctors!"

Renwick was considering his chances of recovery. And in the silence that followed Hackett became absorbed in the marvellous upholstering of the white-columned consulting room. A glance at the spacious entrance revealed an infinitude of beautifully carved stonework. Above the white enamelled doors, amid a perfect cloudwork of sculpture, leaned a robed Christ with hands spread over the blind figure of a naked man.

Hackett was struck by the mixture of Hindu and Christian symbols which permeated the modellings and frescoes. Above the wide stairs, leading to madame's private apartments, were plasters and replicas of the Hindu gods Ganeesh and Siva. A green bronze statue of Buddha stood in savage silhouette against the Christ-figure on the landing.

Only a trained observer could have picked out the remarkable negations in the architectural feeling and design. And Tony Hackett, who possessed more than the average detective's power of imagination, marvelled at the weird groupings of Hindu and Christian deities. It seemed to him as though an Oriental mind had planned the building of the Messonier Institute.

Madame was free at last. Tony, his arm linked in his companion's, followed the attendant into a less spacious operating room. Hackett had expected to meet a lady whose presence reflected the dazzling charlatanry of her surroundings. He saw a white-haired, brilliant-eyed woman with irresistible childlike hands and face. It was her face that puzzled and set his brain at the leap.

Why did young lady specialists wear white wigs? he asked himself. He was certain that the natural hair beneath was a golden red or brown. A woman, Tony argued, might build up her age by the use of false hair, but the eye of youth was difficult of concealment. Madame Messonier's eyes were twenty years old. By various tricks of toilette and the costumier's art she had almost succeeded in making herself a dowager in appearance.

Her glance passed from Hackett to Gifford Renwick with unerring instinct.

"You desire to consult me?" She spoke with her hand resting lightly on the back of a revolving chair that tilted forward toward a curiously designed retinoscope.

"Dr. Teroni Tsarina advised me to see you," Renwick answered quietly.

"Doctor Tsarka!" She repeated the name as one trying to recall some long forgotten personality. "It is so hard to remember these names," she said at last. "People come and go."

"Japanese nerve specialists are rare even in London," he prompted. "Perhaps it does not matter."

"Japanese!" She raised her hand from the chair and smiled in recollection. "He was badly burnt once through the bursting of an over-heated bulb. It is very flattering to be remembered by distinguished personalities."

"I shall remember you, madame, if I am ever again permitted to see the light." Renwick spoke with his face uplifted.

"You have been elsewhere?" Her eyes searched the blind face, the clear-cut features, the boyish mouth.

"To Sir Floyd Garston. He was not enthusiastic about my chances."

"One might as well go to the pyramids," she declared. At a sign from her Tony led Gifford to the chair, and, seating him carefully, retired to a respectful distance.

Renwick was conscious of a numbing pressure of the eyes as though a silver-rimmed ophthalmoscope were searching the cells of his brain. His nerves flinched under the strain. A needle of light seemed to probe and illumine the quivering depths of his retina. The light was withdrawn sharply. He heard her voice, and it sounded very far away.