RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

THE yacht seemed to fall across the reef, her sails flogging to ribbons in the short blasts of wind. Standing at the trade-house window, Elsie Cromer was a helpless spectator of the pathetic little sea drama in progress. Her father had gone to Malolo Island in the nine-ton pearling lugger with the five Rotumah boys, leaving her alone in the trade-house. She had vainly tried to launch the old whaleboat from the skid, with the idea of casting a line aboard the ill-fated little vessel. For the first time in her young career Elsie discovered that a thirty-foot whaleboat has a will of its own: it simply refused to break from the skid and face the walls of green water tumbling over the beach.

About the yacht there was no sign of life. The name, Trixie, was painted in gold letters across the stern. Everything about the snow-white deck and companionway spoke of the owner's wealth; the brass-bound buckets, the silver-plated stair head rails were something of a novelty in those parts.

Never had such a thing happened at Nadir Island. There had been half-a-dozen wrecks during the last hurricane, vessels from the pearling banks or Torres Straits. But always there were men and boys clinging to boats or hatch coamings. While buoyancy remained in a ship or schooner there was the inevitable survivor to tell the tale.

The trade-house was some distance from the beach. From the storm-proof windows she had a clear view of the Trixie. Her father would be home before dark. In the meanwhile the tide was rapidly falling. The twenty foot drop would leave the yacht almost dry in the cradle of the reef.

Elsie waited. It was not every day a seventy-ton, silver-fitted millionaire's toy came into a young girl's life. She wanted to climb aboard before her father returned. It was her lucky day, maybe. Yet a touch of pity entered her as she stared again at the gallant little vessel that had fallen on the reef like a victim from an assassin's sword.

THE tide dropped. The banks of sulphur-hued clouds whirled

south, leaving a sky of raw purple above the palm-skirted atolls.

Soon a fiery sun was pouring down on the naked reefs of Malolo

Bay. Flocks of sooty winged terns planed above the stricken

Trixie, caught in the basin of the reef, her stern rail

bent against an overhanging ledge of coral.

The silence of the bay was almost terrifying. Elsie waded out with a hundred feet of line about her slim waist. Crawling along the shoal edge, she saw that the yacht's toy gangway reached the shallow water, her mast and funnel aslant, her foc's'le laved by the creaming swell, silent and abandoned.

Since childhood Elsie Cromer had lived among South Sea luggers and pearling craft. She had even dived for shell and earned a little money when her father was sick and the tides were kind. Her skin was now a golden tan, her body as lissom as a boy's.

The seas had swept away the Trixie's boats and raft; her decks were snow-white, her hull, as far as she could judge, intact. Sure-footed as any topsail hand, Elsie reached the heavy mahogany door that led to the saloon below. The door was locked!

Elsie drew away with a startled cry. Yet it was possible that the door had been locked from the inside. But why? It occurred to her in a flash that the occupants must be on board! A touch of panic fear assailed Elsie.

Between the inner and outer locking of this little ship's door lay a question of life or death. If the Trixie had accidentally broken from her moorings within the harbour of some adjacent island while her owners were ashore, the door might have been locked to prevent thefts. Such things had happened before. Elsie decided to try the skylights. She found them half-open, with enough space to allow her slim waist and shoulders a passage through.

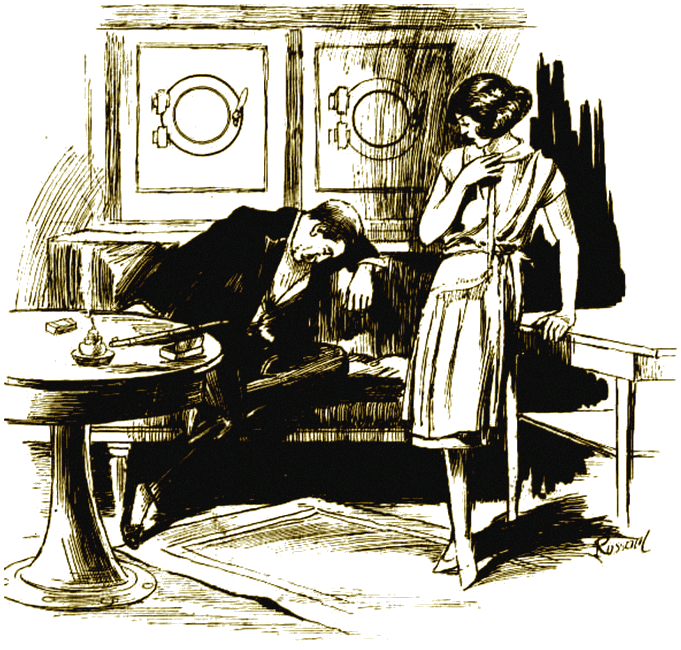

The stateroom below was plainly visible. Water had poured in through the skylights; the carpets of Genoa velvet were flooded ankle-deep. Dropping lightly on to a card-table beneath the transoms, she found the door leading to a small stateroom was shut. With a strangely beating heart she pressed the handle. It opened, revealing the flooded floor and two shut portholes looking on to the reef. Directly under the portholes was a heavily cushioned divan of red plush. Huddled against the padded end was a man in evening dress.

Elsie did not scream. Her terror had drained her white. Yet within the recesses of her mind had been a subconscious intimation of the coming shock.

Elsie did not scream. Her terror had drained her white.

The man was fifty, with grizzled hair and beard. His face was harsh and drawn. Beside him on an ebony table, a silver alcohol-lamp still smouldered. A pipe with a stem of bamboo lay on top of a pair of 'cooking' needles. Elsie's wandering glance fell on a tiny platinum box containing a sticky brown substance. He had been dead hours, had slept through the gale and the yacht's fight for life within the coral strewn archipelago.

Swiftly Elsie withdrew from the cabin of death. At, the top of the stairs she found the door had evidently been locked from the outside and the key taken away. The mystery began to frighten her. For a few moments her lips framed a short prayer for the dead as she returned to the skylight and reached the deck. With scarcely a backward glance at the yacht she hurried to the trade-house to wait her father's return.

OLD Bob Cromer treated the matter as he found it. A search of

the Trixie revealed the name of the dead owner in the

cabin:—Hesketh Rollins, Darling Point, Sydney. Bob was a

thrifty son of the sea, who had fought poverty and shipwreck

since he could remember. He had denied himself the barest

necessities of life in order that Elsie might board at a good

school in Sydney. In her eighteenth year she had returned to

Malolo to share his life and help in the big trade-house near the

beach. When seasons were good Bob shipped his shell to Sydney,

and got his cheque within a month or two at most. After paying

his store accounts at Thursday Island there was little left to

spend on beer and tobacco.

It was a lonely life for Elsie. But Bob Cromer always betted on his luck. Some day he was going to find a rosy pearl, like Jim Anderson had done; or he might happen across a new bank of shell that would fill the empty cases in the trade-house, and put his account right with old Gibbs, of the South China Bank. And now he had returned from Nadir Island to find Elsie in a state of depression because a valuable bit of salvage, in the way of an unbroached seventy-ton yacht, had come to them like a gift from heaven.

The Trixie, with her fittings, linen and silver, furniture, and stores, was worth several thousand pounds. Even a Chinaman wouldn't deny them salvage!

And here was Elsie crying like a baby because the owner, Hesketh Rollins, had taken the opportunity to indulge in an opium jazz. Men who puffed that kind of dope had no right to be alone on a gilded tomb like the Trixie. Yet, in spite of his good fortune, Bob was inclined to ponder the mystery of the Trixie's lonely voyage.

Old Doctor Clunes had come from Thursday Island to certify the cause of Rollins's death. Bob had also taken care to notify the Commissioner of Police of the yacht's tragic arrival within his waters. Beyond moving the trim little vessel to a safer anchorage across the hay and pumping her dry, not a locker or drawer had been interfered with. Bob was going to be satisfied with the law's finding in regard to his part of the salvage. The press and public were welcome to whatever solution the police arrived at in regard to the bamboo pipe and the sticky brown mess in the little platinum box.

SIX days after Elsie had boarded the stranded Trixie a

big snuffling police launch ran into the bay and cast her shore-line over the pin at the end of the trade-house pier.

The Police Commissioner, a man of sixty, stepped ashore, followed by a woman of twenty-five. Behind her walked a youth scarcely out of his teens. The woman was smartly dressed in a suit of well-cut pongee. She carried a pink, jazz-painted parasol that seemed to match the smiling red of her mouth.

Bob Cromer hurried from his work in the boat-shed to greet his visitors. Elsie remained indoors, her childlike eyes exploring the lovely creation in pink and cream pongee. The Police Commissioner shook hands with the old pearler, and then briefly introduced his companions.

"This is Mrs. Rollins, widow of the late Hesketh Rollins," he said, indicating the pink parasol. "And this young man is Neville Darcy, secretary to the late Hesketh Rollins. A sad business, Mr. Cromer, a sad business!"

Neville Darcy was well over six feet in his Oxford tans. He smelt of school and the cricket ground. At random Bob Cromer labelled him a sport and something of a gentleman. For the lady with the pink stuff on her lips he had no label whatever. A keen judge of tiger sharks and Chinese cyclones, old Bob was worse than a blind man when it came to summing up a rich widow. All he knew was that she was now his guest, and that this grizzled police officer was going to say a few things in reference to a bamboo pipe, a platinum box, and the sticky stuff inside it. He was going to say plenty about the young gentleman who smelt of the cricket ground and the hay paddock. Also, Bob had a premonition that the grizzled officer, whose name was Pat Brady, might make a few remarks to Mrs. Rollins, who smelt and looked like a flower garden after rain.

Not a moment was lost in getting aboard the Trixie. Elsie, at the bidding of the police officer, made one of the party. Mr. Brady was anxious to hear from her own lips the story of her entry into the cabin of the dead man.

The morning was stiflingly hot. Clouds of Pacific gulls drowsed over the gently heaving yacht. The whaleboat put the little party under the lowered gangway. Quickly the Police Commissioner ascended, beckoning the others to follow. The eyes of Norma Rollins drank in every line of Elsie's beautiful young face as she outlined in simple words the story of the yacht's miraculous entry into the bay, wind-driven and helpless in the smothering seas. Norma Rollins looked up sharply when Elsie spoke of her journey through the breakers with the line about her waist.

"Trouble comes to some people unasked; other folks hunt for it with ropes!" she commented bitterly.

A flush deepened on Elsie's cheek. She made no reply. Old Bob gestured apologetically. "Been used to yachts an' luggers all her life," he explained. "Can't keep Elsie off a new ship. Some gels like going into shops an' bazaars. Elsie likes the feel of a clean deck under her feet. She could no more stop boardin' this here vessel than them birds can stop flyin' over the masthead."

The Police Commissioner nodded sympathetically. Norma Rollins coughed and favoured the young secretary with a swift glance.

"Miss Cromer's curiosity led to an unpleasant awakening," she declared with a wistful smile. "I hate ships and the very thought of them. That is why I never set foot aboard the Trixie."

The Commissioner wrote down her statement in his notebook. Then he turned to Bob Cromer, standing in the cabin doorway. It had occurred to him that an explanation of the affair from his side might not come amiss. It seemed only fair that the Cromers should understand the true meaning of the Rollins's riddle.

"The yacht," he explained slowly, "was used by Mr. Rollins for a cruise around these islands. He had been ill for some months in Sydney. He reached Nadir Island on the seventeenth of last month. His only travelling companion was our young friend here."

He nodded towards the quiet-browed Neville Darcy, who had followed Norma's statements with growing interest.

"I may say," the Commissioner went on, "that Mrs. Rollins did not accompany her husband. She joined him at Nadir Island the day after he arrived. She did not go aboard the Trixie, saying she preferred to meet him on shore at the trade-house of a Consular friend. They met in the Consulate to settle some private business matter, and Mr. Rollins, accompanied by his secretary, returned to the yacht."

"That night," the Commissioner stated with emphasis, "the Trixie broke from her moorings and drifted into the storm that bore her finally into this bay."

Bob Cromer looked up quickly. "Where was the crew?" he demanded. "Where was Mr. Darcy?"

The Police Commissioner answered for the young secretary.

"There was a crew of nine Erromango boys and a skipper named Trent. Trent is in hospital at Nadir as a result of an affray with two of the boys. This affray led to the crew's desertion on the night of the Trixie's breakaway. Neville Darcy had gone ashore to acquaint Trent of the wholesale desertion. It was a very natural proceeding," the Commissioner stated with feeling. "Something had to be done, and Trent was the man to advise him. When Neville returned to the moorings he found the wind had risen and the yacht gone! It was pitch dark."

A hush fell on the cabin. The Police Commissioner studied the faces, of the little group around him. Elsie's quivering lips and moistened eye told him nothing beyond what he already knew. The face of the young secretary expressed pity and restraint. He had nothing to say. Norma's gloved fingers toyed idly with the fringe of a cushion beside her. The silence was stark, broken only by the gulls outside.

"We now come to Elsie Cromer's discovery," the Commissioner went on. "It is beyond us how Mr. Rollins got possession of the pipe and opium that resulted in his death.

"I am permitted to say that Hesketh Rollins was an opium addict, but he had long ago sworn to give it up. It was for this reason he undertook the island cruises. Not a grain of the drug accompanied him. His doctors had made it plain that further indulgence would be fatal. So we come to the conclusion that the smoking outfit was carried on board from Nadir Island during Neville's short absence. Moreover, the person who supplied the drug took the trouble to bolt certain doors, in the hope, no doubt, of puzzling the opium sleeper if he tried to come on deck."

Old Bob Cromer fidgeted in the doorway of the cabin. He was sorry for the dead man, sorry for this quiet young secretary who seemed to have been caught in the shadow of a cruel domestic tragedy.

"You got your work cut out, Mr. Brady," he volunteered bluntly, "to spot the party who put a knife across the Trixie's mooring-line. As a sailor I'll say the line was cut so's the yacht would drift into that hell smother that was blowing down at the time."

The light of agreement flashed in the Commissioner's eye. He waited for more.

"It was the most ungodly thing that ever happened in these parts," Bob continued, unable to control his feelings. "Here was a man like Hesketh Rollins settin' his teeth to beat the drug habit. We've all got to fight somethin', if it's only rotten Governments or crooked partners. Rollins was fightin' the worst kind of a devil that ever came out of a metal box. If he'd been left alone he'd have won his fight, maybe. I'm game to bet that the party what brought the stuff to him pressed it on him pretty hard—made him believe a few puffs would buck him up. By the look of things," Bob concluded sorrowfully, "the poor fellow smoked like a Chinaman after a long fast."

Norma Rollins fanned herself with a palm leaf vigorously. The proceedings bored her. Every moment spent in the cabin seemed to shatter her self-complacency. Again and again her eyes sought the young secretary, as though begging him to say something that would end this stupid inquiry. Elsie saw no answering light in Neville's glance. He was like one who courted investigation. It was now evident to her that he had loved the man who had paid forfeit to the poison-god in the platinum box.

Returning to the trade-house, the Police Commissioner heard with dismay that his petrol tank aboard the launch was leaking badly. His engineer informed him with a wry face that there was not enough oil on board to lake them back to Nadir Island.

Norma received the news with a bitter smile. Always something was happening to spoil her plans for the future. She glanced at Neville Darcy for sympathy, and found him speaking in an earnest undertone to Elsie Cromer. Old Bob bade the party welcome to his trade-house. Some time must elapse before he could bring a supply of petrol from Barren Head lighthouse, a hundred-odd miles to the south.

While Elsie was glad to meet new faces and listen to the chatter of the city-bred Mrs. Rollins, she could not escape the sense of tragedy that enveloped the silent little vessel across the bay. Her young mind began to peer beyond the curtain of this strange sea mystery until every detail lay stark and clear for her to read.

During her father's absence at Barren Head the position of hostess fell to Elsie. The trade-house had boasted two Chinese cooks, but they had gone to another trading post in the Navigators, leaving Elsie to the cooking fires and the occasional help of Narangi, the Rolumah boy.

"I want you to feel at home," she said to the visitors. "We own a mountain and one lagoon. Any amount of fish and game. Two old muzzle-loaders in the shed that Dad uses to kill time. That's all I've ever known him to kill when he goes shooting duck," she added, with suddenly twinkling eyes.

The Police Commissioner laughed heartily at this slim, girlish figure seated at the head of the table. He had his own two girls at school at Brisbane. He knew the meaning of Elsie's lonely life in this out-of-the-way group of islands, the bi-annual hurricanes, drought, and flying epidemics, to say nothing of the occasional appearance of a drunken schooner captain, demanding stores and liquor. He was attracted by her unusual beauty. The sea and her life on the open beaches, tumbling in and out of pearling luggers, had made her as whippy and agile as a boy. A brave little girl, he told himself.

Neville Darcy appeared to appreciate the result of the leaking oil tank. At the back of the lagoon he found a stretch of pandanus forest, with clouds of black duck and teal rising at every step. The mountain streams were stiff with trout; the inlets swarmed with mullet and barramundi.

Neville had spent the last few years in the society of Hesketh Rollins, retired wool-broker. Norma had been a member of a travelling theatrical company before her marriage with Rollins. Nearly the whole of his fortune had been settled on her. For the last year and a half she had avoided her husband's society, losing herself in a daily round of social engagements. Here, among the pandanus palms and the piping of birds across the lagoon, he had ample leisure to review his past life within the Rollins's household at Darling Point.

He had been a rich man's slave, his typewriter fixed at the rich man's bedside. What a life! Yet in Hesketh Rollins he had lost a friend. For the last week the tragedy had preyed on his young mind. At one time he had felt sorry for the young actress who had practically chained herself to a corpse. But youth will often break chains, he told himself, whether they be forged to the gates of heaven or hell.

A hot pipe of opium had melted Norma's chain! And this rich woman's visit to Nadir Island, only a little while before Hesketh's disappearance, pressed on him. He felt that the crime was his fault. He should never have left his nerve-ridden employer alone, not for an instant.

He walked quickly in the direction of the trade-house. In the coral-strewn path he found himself face to face with Norma. She had just come from the cool sitting-room. In the scented island night she seemed ablaze with jewels, a stage queen playing her very best.

"Enjoying the sights of the island, Neville?" she questioned sweetly. "Killing Father Time with Elsie's muzzle-loader?" she added, with a malicious glance at the ancient weapon in his hand. He checked a passionate retort; shook himself as one chafing under a perpetual lash.

"I'm busy thinking of my next job," he declared flatly.

The perfume of her scintillating presence affected him no more than a dead queen bee. He felt tired. In the star-shine her face had grown suddenly pleading.

"I want to tell you, Neville, that your next job will hold more than a typewriter and ten hours a day by a sick man's bed. My husband treated you like a galley slave."

A flush darkened his cheek for a moment. From the trade-house dining room came the sound of Elsie's fingers running over one of Strauss's haunting songs from 'Ariadne.' The theme was full of the jewelled fragrance of lonely island nights. The piano itself seemed in perfect tune.

Neville turned away, paused an instant to look back at the woman standing in the path.

"I am going to ask Mr. Cromer to let me stay here," he said quietly. "He wants a partner. And for the born slave there's nothing like a change of galleys occasionally."

He entered the trade-house with a buoyant step.

BOB CROMER returned from Barren Head with several drums of oil

in the lugger's forepart. "You can fill your tank now," he said

to the waiting Police Commissioner.

The wind had gone down; the surf was breaking in zones of dazzling white along the pandanus-sheltered beaches.

"A good night for the crossing," Bob declared cheerfully, as he transferred the drums of oil to the big Government launch. The Police Commissioner nodded.

"We'll fetch Nadir before daybreak," he predicted, glancing at the sapphire sky above the windless stretch of sea.

Norma Rollins stepped lightly from the trade-house, looked back swiftly at the open window where Neville Darcy was finishing a letter at the little writing-table.

"You won't escape toil and hardship staying here," she intimated, with a touch of despair in her voice. "Come with me, Neville," she begged.

He went on writing rapidly, then raised his head as one who had not heard.

"I'll come to the beach and say good-bye," he told her with finality. "We'll let it go at that."

Norma turned to the beach, humming softly to herself as one sure of her purpose. A faint wisp of moon had risen in the south-east. The voices of the men in the police launch reached her with startling clearness. Bob Cromer's words, addressed to the Commissioner, were definite enough.

"Young Darcy wants to try his hand in the pearling business. Said he'd like to join me as a partner."

"Well, he's a nice lad," came from the police officer. "I've studied him pretty close in the last week or so. Take it from me, Bob, he had nothing to do with Hesketh's last sleep on the Trixie. There's no real evidence to prove it wasn't an ordinary misadventure."

Norma turned sharply at sound of footsteps in her rear. Elsie was standing beside her, tall, shy, and with a troubled look in her violet eyes.

"I wish you'd arrange to take the yacht, Mrs. Rollins. I've gone over the matter with father, and he says you're welcome to retain it. There's no question of salvage between us."

Norma shot a glance at Elsie as though for the first time. "You are very kind, Miss Cromer, to offer me something I don't want. I told you I loathe ships, big and little. And"—she pointed to Neville's open window—"will you be good enough to tell Mr. Darcy I'm waiting?"

Elsie stood like a young bamboo in the path, resolute and fixed of purpose. "Never mind Mr. Darcy," she answered quietly. "Forget everything but me."

Norma Rollins eyed her askance. This was not the sweet-voiced child who had played the laughing hostess for the last two days. This was not the little fetch-and-carry girl that one might have handed a five-pound note for service rendered. Something had happened!

"Forget everything," Elsie went on, "but the one who climbed aboard the yacht out there when she blew in like a ghost ship from the dead."

"We know that," Norma snapped, completely on her guard. "Tell me something fresh—something about tulips or Iceland poppies. I want to keep cool."

Elsie's eyes were fixed on the dream-like yacht across the bay. Norma's sneer was lost.

"When I boarded the Trixie," she went on, "I saw that a lady had been there."

Norma whipped round with a sudden catch in her breath. All the willowy softness had left her. Her face was keen set as a blade.

"Now, look here, little girl," she said with frozen deliberation, "I haven't come to this old island to hear your voice. Let's be straight. When I commit a crime there'll be no daggers left behind for kids like you to show the police. Forget all about my husband's habits. Drug fiends will be served!"

"When I commit a crime there'll be no daggers

left behind for kids like you to show the police.

"Someone went out of their way to serve your husband," Elsie told her. "Yet I pitied the woman who had entered the cabin of this morphia man. I wanted to cry afterwards when I read traces of her chalked evening shoes on the red carpet. She had come in haste from a dance, evidently, at a time when people's attention was fixed on the music."

"Why did you withhold this information from Mr. Brady?" Norma challenged.

"Because women often pity women," Elsie answered sadly. "Who could look at a dead opium victim without a thought of the woman chained to him for life? Even a savage might have read the signs I saw around."

"Signs?" Norma cried, blanching now under the younger woman's fearless statements. She turned blindly from the beach as if to hide her emotion from the people in the launch. "You are mad to talk like this! You have been dreaming!"

Elsie sighed. "Dreaming of a cut rope trailing from the yacht's cleat, the cut rope that sent a man out to his last sleep in the storm! No one saw it done."

Norma recovered her shaking senses with an effort. A soft laugh escaped her. "My dear child, you are living on an island, of dreams. And you've been dreaming wrong. There isn't a scrap of evidence to prove that a woman was near Hesketh before the Trixie broke from her moorings. Try another dream, Miss Cromer!"

The voices in the big police launch grew silent. The Commissioner had seen them, was making signs in their direction.

"Come along, Mrs. Rollins! I'm sorry Neville is staying on with Mr. Cromer. Anyway, it's a fine night for the crossing."

Norma came back to where Elsie was standing. There was a touch of the theatrical and the vulgar in her flaunting adieu.

"Good-bye." She held out her hand defiantly. "Make a better guess next time. Tral-lal-la!"

Elsie took her hand, held it firmly for a period of six heart-beats.

"Good-bye," she said. "A little thing like this stops all the guessing. You left it on the cabin table beside the platinum opium box." It was a tiny diamond-studded case that Elsie had put in her hand. The monogram N.R. was engraved on its pencil-shaped surface. Fitted into the end was a stick of carmine.

Norma Rollins stared at the jewelled lipstick, a sudden film of terror blanching her eyes. With phantom haste she turned and staggered towards the waiting launch. Neville Darcy seemed to follow on her heels, a letter in his hand. He reached the launch, and for a while was lost among the bustling shapes on the deck.

The night and the palms seemed to revolve about Elsie. She heard the last farewell hoot of the police launch as it sped from the island, her lights gleaming dully in the sea mists.

A footstep on the coral path roused the fainting blood from her young heart. Neville Darcy was beside her, his strong arm steadying her swaying steps.

"I wonder," he said as they reached the warm lights of the house, "whose ghost scared Mrs. Rollins at the last moment?"

In the great peace that had come to her Elsie felt there was no need to answer Neville's question.

The ghost had left the island.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.