RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

'A RAFT,' Jeremy Saltwyn admitted, wiping his old binoculars and peering again across the dazzling belts of surf to where the square black object floundered among the mountainous breakers. Saltwyn's mouth snapped with sudden decision as he turned to the group of five half-naked islanders standing beside the big canoe.

'I'll not risk a good boat in that hell-smother,' he decided, pointing to the long, deadly walls of green water bursting with the sound of gunfire on the reefs.

'They're dead, by the look of them,' he added, focussing the two figures on the raft, 'and two dead men are not worth one live boat.'

It was a sight that held the little group of natives spellbound. The raft tilted and sagged as the current swung it into the maelstrom of pounding surf. The two men lashed to the sail-less mast had the appearance of wind-dried mummies in the steely-white glare of sun and sea-foam.

Saltwyn's hand restrained the natives from plunging into the boiling mass of reef-broken water in their desire to assist the raft and its occupants from drowning.

'Stand by your boat, I say!' he roared. 'How in thunder am I to carry on here alone if you are drowned or crippled on those reefs? This lifesaving stunt is no business of mine: I've other work that needs attention.'

The raft with its two glassy-eyed occupants was now attending to itself. Caught in the undertow, it swirled and dived until a large comber drove it full onto a ledge of reef under the whaleback shoal. Unable to control the five impatient natives, they leaped into the whirling waters and fought their way through the deadly scour of the tide until two of them succeeded in gripping the raft.

With the cunning of their race they played skill against the sledge-hammer blows of the waves that now battered the raft as a bull batters a broken hurdle or fence.

'Aei tai ano!'

Swimming, dragging and steering the raft with their bodies, they forced it into the shallows with the gusto of children at a beach party.

Saltwyn remained a stiff-lipped spectator, his sun-withered face unable to control the look of boredom that overcame him as a result of their superhuman efforts. His hawk eyes quested over the two shapes now huddled on the beach; one a middle-aged sailor with the frame of a Hercules and the face of a beast. His flat, simian brow and cheek bore evidence of knife scars from some recent conflict. His great hairy chest was bare and covered with tattoo marks. He sprawled in the hot sand, gasping like one who had escaped from the equatorial hells of a waterless desert.

His companion was little more than a boy, slender in shape and dressed in tattered clothes that once had borne the cut of fashion. His face was a pallid mask, almost lifeless in its immobility. His milk-white teeth were visible through his dry, sun-parched lips.

The scarred Hercules raised a hand and pointed to his mouth, and then, as though the effort was more than he could endure, sank back to the beach. Saltwyn grinned unamiably. Here were two mouths, to feed, two starved bodies to nurse and win back to life. And for what, he asked himself in silent contemplation of the tattooed man's giant proportions. In a week the pair would be up and about the island, prying here and there amongst his most treasured shell hatcheries and preserves.

Philanthropy was no part of Jeremy Saltwyn's creed. If a few meals and a little money would have dispensed with his uninvited guests he would gladly have paid the price. It might be months before a schooner or tramp visited Vitonga, and Jeremy quailed at the prospect of spending his days in the society of the ape-browed man with the tattooed chest, and arms.

Moreover, his studied seclusion in that part of the Pacific was now at an end. Both these men would carry the news of his precious shell-hatcheries to the boozing dens of a dozen trading ports, where the scum of sailordom lived and dreamed of undiscovered atolls like Vitonga.

The possibilities of shipwrecked sailors and visiting schooners had been his nightmare in the past. He had discovered an El Dorado of golden-edge shell in the five lagoons that made up the group of atolls surrounding Vitonga. He employed only native shellers, men who never voyaged beyond the group. But now—these two whites had come like starved wolves to disturb the seclusion and tranquillity of his island home.

A native poured water from a nut shell between the blackened lips of the tattooed man. The boy also got his share, while across the glittering stretch of beach the sun stalked like a flaming jewel to draw the life sap from heart and brain.

Saltwyn watched each movement of the tattooed man, lying face down in the wet sand as though to shut out the fierce rays of the sun. Around his shaggy throat was a coarse red kerchief, twisted into a dozen knots and bulging slightly in places. Saltwyn moved a step forward and slit the red kerchief with the blade of a jack-knife. It fell to the beach. With the deliberation of a prison governor Saltwyn picked up the rag and shook it between his strong fingers.

A dozen blood-hued pearls fell into his palm. For fifty seconds he held them to the light, weighing, scrutinising their colour and orient with the craft of an expert. At the conclusion of his survey his eyes snapped vindictively; a half-uttered word froze on his lips.

Slowly the tattooed man rose to his elbow, his hand fumbling at his throat, Then his animal eyes turned dumbly to the figure of Saltwyn brooding over the wine-hued gems in his palm. A look of unutterable hate crossed him: his thick lips seemed to crack in the effort to find speech.

'Say, Mr. Man. I fished in hell for them stones. They're mine.' His hand stroked the air like the paw of a tiger. 'I got a nerve when it comes to divin' for other people's beans, but you—well, you're the limit!' he concluded with unexpected vehemence.

The boy with the milk-white teeth woke up from his thirst agony and looked at Saltwyn. His lips quivered strangely, but he made no sound. Saltwyn placed the pearls in the pocket of his white coat. Then he signed to the five natives standing on the beach. 'Get these people into one of the huts,' he ordered. 'As for you—' he spun round on the tattooed man with darkly blazing eyes—'another whine from you and I'll clap you in irons. In the meanwhile I'll put an inquiry through the consulate at Honolulu concerning your identity.'

Without ado the natives bore the two men to a palm-thatched hut that stood in the shadow of some pandanus scrub overlooking a medium-sized lagoon. Village there was none, only the interminable saucer shaped reefs that surrounded the sapphire mirrors of the five lagoons. A couple of seven-ton pearling luggers rolled in the tideway of a distant channel.

SALTWYN'S house was a roomy, flat-roofed affair, with a wide

verandah overlooking the nearest lagoon. On the third day

following the raft episode he stepped into the hut where the two

white men had been carried by the natives. The young man was

seated near the door. He rose at Saltwyn's entry and stood with

head slightly bent. The tattooed man was lying on a camp bed. He

made no movement, although the voice of the lagoon owner cut like

a knife on the still, hot air.

'Morning to you, my lad,' he said, addressing the boy. 'Tell me your name, and the reason you are found on a raft in this part of the Pacific,' he commanded without ceremony or hesitation.

The young man had recovered from his recent privations. His skin was clearer, his eyes more humid. There was a slight tremor in his voice as he spoke.

'My name is Kenneth Fane. I was passenger by the steamer Valmos that left Sydney for Honolulu and London five weeks ago. The Valmos struck a reef after leaving Samoa. The weather was bad, and as far as I can judge only a select few got away in the lifeboats.

'It was a ghastly business all through.' Fane paused, as though the recollection of his past experience had burnt into his young brain.

'Go on,' Saltwyn gritted. 'I want to hear.'

Fane took breath like one caught between raging seas as he continued: 'After the Valmos struck I found myself in the midst of a struggling crowd of men and women. I need not tell you that the struggle was for the lifeboats. It was a fight I could not join. So I waited under the bridge until the Valmos was well down by the head, and the last of the passengers had been swept away or drowned in the lowering of the boats. The seas were running over the rail. 'The captain was still on the bridge, and remained there until the last. The Valmos went down with a terrific lurch to starboard. I was carried off my feet and hurled into the sea.

'When I came to the surface I spied the raft with'—he paused and turned slowly in the direction of the tattooed man—Mr. Buck Trope, there, using a steering-oar to some purpose.'

'And no one on that raft but himself.' Saltwyn accused, almost fiercely. 'Looking after his own beef, they say in the shanghai ships.'

Fane was silent for a moment, like one unwilling to draw Saltwyn's wrath upon the head of his raft mate. His breast, laboured painfully as he continued: 'Trope allowed me to climb on the raft. And so we slaved together, drifting and battling with currents and winds, hoping to make land. We had no chart or knowledge of navigation. We just drifted and guessed our course, and these atolls might have been in Tahiti or the Marquesas for all we knew.'

Saltwyn laughed succinctly.

'Maybe you'll explain how your friend here came to be wearing a thousand pounds' worth of pearls around his neck?' he demanded icily. 'Did one of the lady passengers throw them into his pocket before the Valmos went down? Or did the Captain hand them to him for safety?'

Fane shook himself like one taking a beating on another's behalf.

'I know nothing of the pearls,' he answered steadily. 'Absolutely nothing.'

Slowly like a panther roused from his rest the tattooed man sat up on the camp-bed. Like Fane, food and rest had worked wonders in his appearance. Heat and strength radiated from his muscle-packed frame.

'See here, Mr. Boss, you got too much gab an' gas for my likin'.

His great shoulders were hunched like an ourang-outang's. His naked forearms were knotted where the rolls of sinew moved like ropes under the thick black hair. His slat eyes burned with the slow rage that dozed in him. His long, unclipped fingernails worked like the claws of a bear.

'You pinched my pearls!' he stated slowly and without stirring on the camp-bed. 'Just like a crimp-shop Mary. An' when we was near bein' sucked down by the breakers you stood by like a cheap showman in front of them Kanakas.'

Saltwyn listened while a stark, bleak rage swelled in his own breast. He was fifty, more, and it was years since a man or woman had dared to accuse him of a misdemeanor.

'I took charge of those pearls because I know you are a thief, a ship's robber, a safe-smasher. One more squeal from you, Mr. Buck Trope, and you'll find yourself with irons on your feet, lying in the tideway where the man-eaters come to feed.'

Trope leaned on his elbow and stared at Saltwyn as a panther stares at a bull in the distance.

'Ship's thief, eh, Mr. Boss? Safe-smasher?' He paused to moisten his lips and clip his nails together in his suppressed rage. 'Who says I'll let you hand me down to the sharks?' he inquired with a drawling mimicry in his voice. 'I reckon your lagoons are full of the beasts; kind of watchdogs to keep out poachers and divers, eh?'

Saltwyn made no answer. But, in the doorway, he paused to look back at the crouching figure on the camp-bed. Then he signed to Fane thoughtfully.

'I'll find you a job on one of my luggers, my lad. There's nothing like work for idle hands. Come along.'

Once clear of the hut Saltwyn's hand fell lightly on Fane's ragged sleeve. 'You'll be needing a new rig-out, Kenneth Fane. Come to the store; I'll fit you up,' he added, with an approving glance at the young man's clean-cut figure and honest face.

Fane was glad enough to discard his rags and accept clean linen and a white canvas suit. The Valmos had swallowed his wardrobe. Of a small fortune he had inherited two years before nothing remained except the memory of a cattle station he had attempted to run in Queensland.

Saltwyn took a ledger from a safe in a corner of the store and thrust it before the astonished Fane. Opening it, he indicated an entry made on the 17th of November of that year:

'Sent, twelve blood pearls of extraordinary value, size, and lustre, per island mission steamer John Williams for despatch to London, November 17.—January '28: Mission steamer John Williams returned here, her captain reports the twelve pearls were shipped per steamer Valmos from Sydney to London, December 10.'

He indicated an entry made on the 17th of November of that year:

'Sent, twelve blood pearls of extraordinary value, size,

and lustre.'

Saltwyn drew the twelve pearls he had snatched from Trope's kerchief and placed them on the store counter triumphantly.

'And that's that, Kenneth Fane,' he declared. 'Beat it if you can!'

Fane stared at the gems in round-eyed amaze.

'You mean that these pearls are the ones you sent by the John Williams?' he gasped.

'They're my pearls come back,' Saltwyn flung out. 'My pearls, come back in the greasy neck-clout of that boob in the hut!'

'He was a fireman on the Valmos,' Fane informed him. 'I never met him until I saw him on the raft. Possibly he stole them in the stampede for the boats. Officers and passengers were dropping things about the decks. I see no other solution to the mystery, Mr. Saltwyn.'

The old man nodded broodingly. It was some time before he spoke.

'You'll judge me a hard and difficult man, Kenneth Fane,' he said at last. 'But no harder than other white traders struggling against the sea and the hosts of thieves—thieves with talons like Trope. In ten years I've made enough to secure my daughter Molly from want and privation. Six months ago I arranged her passage out here. It's a lonely life for an old man,' he added with a sigh. 'Her last letter said she was coming with all speed. But the ways of God and the sea are strange, Mr. Fane. Instead of Molly, the sea sends me that!'

Saltwyn gestured in the direction of the hut where Trope lay snoring on his camp-bed.

Kenneth was interested in the old pearler's store, that held many relics of the surrounding atolls, together with a number of interesting undersea photographs taken by experts with special cameras. The voice of Saltwyn broke in on his thoughts.

'The presence of your raft-mate on this island puts my belongings in jeopardy, Mr. Fane. It's difficult to protect valuables here. A crook like Trope would walk away with my office safe, after murdering us, and put it in a boat.

'I remember Bully Hayes walking off with the German Consul's safe at Apia. There's no insurance against such men. While Trope and the pearls are here I shall know no peace.'

Kenneth went aboard the smallest of the luggers to familiarise himself with the wonderful shell-hatcheries of the lagoons. He was glad enough that the fates had presented him with another chance in life, and although Saltwyn was not the angelic type of trader so often depicted in South Sea society, the milk of human kindness ran in streaks through his vitriolic temperament.

It was the thought of Trope, who had lain in torment by his side on the raft, that kept him awake a night. Trope, with the gorilla hands and the strength of six men! Even in his dreams Kenneth fell that his ugly raft-mate was spying on Saltwyn for a scent that would show him the hiding-place of the pearls.

TROPE stirred uneasily on the camp-bed. A huge tropic moon

swung like a lantern over the distant reefs. The sea had gone

down: the silken thrash of surf on the beach broke the ghostly

silence of the island night. Rising softly, he peered from the

hut doorway in the direction of the store near the lagoon. The

sharp outline of a lugger on No. 2 lagoon was revealed in that

quick, wolf stare. A lugger would lake him anywhere. Men had

sailed the seas in smaller craft. It would be more comfortable

than the raft, anyway! He laughed silently, his black teeth

munching a piece of tobacco he had begged from one of the

natives.

Saltwyn was merely awaiting the arrival of the mission steamer to pack him off in irons to the nearest consulate, where the charge of stealing pearls from the Valmos would be laid against him. Trope felt that his chance was now, before a police launch came scooting across the skyline. He strolled from the hut with no fixed purpose except the pursuit of his wild-beast instincts.

Nothing came to men who slept day and night, he told himself. Being awake when others were stampeding blindly for the boats that night on the Valmos had led him on the trail of the ship's purser when he dropped the pearls in his dash for the lifeboat.

Trope walked in the shadow of the pandanus scrub, his glance wandering across the lagoon towards Saltwyn's house.

The tide was out and had drained the lagoon almost to its bed, leaving only a number of shallow holes awash. It was some minutes before his eyes accustomed themselves to the moon glare on the waterless expanse. Then he saw the outline of Jeremy Saltwyn standing within the channel entrance to the lagoon. The old man was piling palm logs across the bottle-neck of coral through which the tide water flowed. Trope's curiosity held him stiff-jawed and motionless. His bristling jaw hung. Then he stole forward to the edge of the tide-emptied lagoon and lay flat on the naked beach. A curious feeling of terror gripped his spine; he was almost on the point of calling out.

In the lagoon mud, within a few yards from Saltwyn, lay a long torpedo shape that flogged and squirmed in the shallows of a half-drained channel. The moonlight played like white fire on the quick shifting figure of Saltwyn. In his hand was a small cylinder-shaped piece of metal attached to a line with a running knot.

Like a boxer in a ring Saltwyn circled round the kicking, thrashing shark that was unable to float or turn in the shallow water of the channel. Once or twice the sabre-edged fluke struck the old man as he stepped near.

It was evident to Trope that Saltwyn aimed at slipping the line, with the cylinder attached, over the shark's propeller fin and making it secure. And then—

Trope was aware that sharks entered lagoons when fed. He had heard of Chinese pearl-stealers trapping sharks, as Saltwyn had trapped the monster in the channel, for the purpose of attaching illicit gems to their bodies. If the Chinaman knew his business there was no fear of the shark escaping from the lagoon with its precious burden. It was a matter of controlling the entry and outflow of the tides. The shark could be overhauled at will and the booty recovered. Of course, men were only driven to such expedients when they feared a visit from police patrols or island desperadoes in search of loot.

Once more Saltwyn approached the grey-bellied monster, the line with the cylinder attached held craftily in his hand. The shark had grown quieter, its long hammer head wallowing in the mud and sea-grass of the channel floor. Kneeling warily beside it, Saltwyn cast the noosed end of the line over the propeller fin and knotted it with the swiftness and skill of a born sailor. He leaped back in time to avoid a blow that sounded to Trope like the slamming of a door. A shower of mud and stones almost blinded Saltwyn as he retreated from the monster's awakened fury.

Climbing the coral wall of the channel, he paused to examine a teak-wood sluice gate that was sometimes used for preventing the outflow of water from the lagoon. This sluice gate faced the open Pacific. Saltwyn crawled back through the channel and removed the logs from the lagoon entrance to the channel.

Trope scratched his chin in some perplexity, but in a flash he saw that the old man intended the shark to escape to the ocean the moment the tide flushed the lagoon. His amazement deepened until he recalled the fact that the hammerhead would certainly return, if tempted by a plentiful supply of fresh bait. The outer reefs were hungry places for full-grown sharks, and the inner lagoon teemed with fish and oyster mush thrown from the luggers.

Trope cursed under his breath. With the return of the tide the hammerhead would make its way to the outer shoals; and then good-bye to the pearls for days, weeks perhaps.

In the bright moon glow he saw the shape of Saltwyn disappear in the direction of the house, satisfied, no doubt, that the pearls were beyond the reach of thieving fingers.

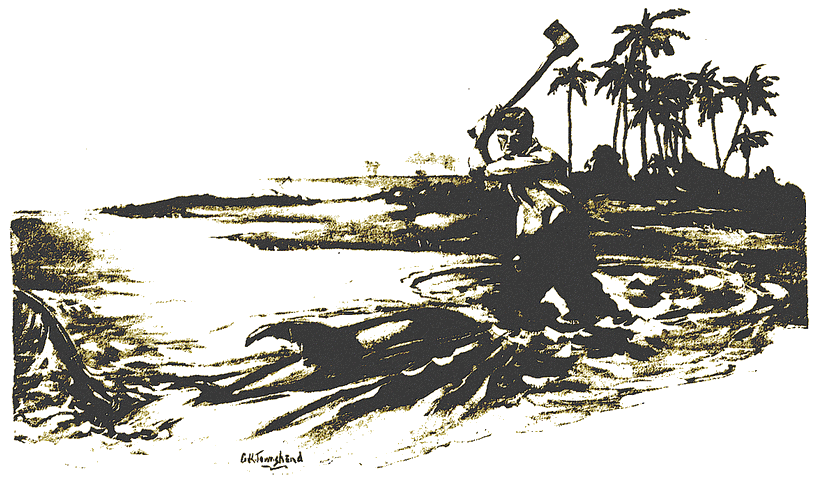

It came to Trope, lying face down on the beach, that his golden hour had struck. What was there to prevent him cutting the line that held the cylinder to the monster's spiny length? Earlier in the day he had seen a native cutting wood with an axe for the galley fires. The native had carried the wood aboard the lugger at No. 2 lagoon, leaving the axe on the pile at the rear of Saltwyn's house.

Crawling through the sand, he clung to the shelter of the coral outcrop, while the sound of the returning tide hummed like a death chant in his ear. Once the monster in the reef channel felt the water swirling about its body it would soon flog its way down the channel to the open sea.

The sweat of rage and apprehension broke over Trope. All his life he had slaved in the hellish stokeholes of Pacific and Atlantic ships. He had endured the heat of fires that wrung men's bodies to tatters. Drink, pain, and misery had been his lot. And now—one clout of an axe would put him in easy street, he would see to it that Saltwyn would never get the pearls again!

A light burned in the store-room window. The woodheap was mercifully in the shadow of an outbuilding; he crossed the last strip of beach on all fours, his shins running red from contact with the jagged coral. His eyes started, his hands clutched right and left across the woodheap. Where was the accursed axe? Surely the native had not taken it aboard the lugger. Without a steel weapon he could not approach the saw-toothed brute grovelling in the channel.

Then his staring eyes beheld the long-handled chopper lying in the shadow of the woodheap. Gripping it with an oath, he slid back to the beach under the shelter of the reefs. His nerves tingled as he moved forward to the splashing sounds near the channel.

The hammerhead and snout rose in the air as the tide crawled into the channel. In a little while the water would be over its dorsal fin. He laughed hoarsely now at the monster's struggles as he waded to his hips through the sea-grass, the axe gripped in his right hand.

The shark rolled from side to side, awaiting instinctively the big flush that would lift it clear of the mud and weeds. The surf was pounding heavily outside the reefs. Trope drew breath as he poised himself within a few feet of the gleaming white throat.

An unexpected touch of panic entered him. The glinting, sabre-toothed jaws seemed to reflect the ghostly brilliance of the moonlight; its scaly, flashing length seemed ready to leap from the water. For an instant the swinish eyes of the monster fastened on him with almost devilish intensity. There was enough water in the channel now to allow it to move a foot or two down the channel.

Digging his toes into the soft mud and sea-grass, Trope measured his stroke, while his heart hammered like a piston at his ribs. There must be no mistake, no hitting the air. One good blow was worth a dozen taps in the wrong place. Hoosht!

One good blow was worth a dozen taps in the wrong place.

He launched his flashing stroke with the deliberation of a matador. The axe blade touched the moonlit skull of the shark with a sliding, glancing effect, skating off into the air. Trope was jerked from his foothold in the treacherous sea-grass and flung across the kicking, bucking fins and fluke. The contact of his hot hands was like an electric stroke to the already maddened shark. Its body doubled like a hooked salmon and shot back with the force of a catapult.

Trope was struck with the impact of a flying boom and hurled face down into the water. Struggling blindly to his feet, the axe still clutched in his hand, he faced the bristling, wave-drenched body, his muscles binding like roots, his red brain sobbing from the pain of the blow he had received.

'Come on, you cursed sea-hound! I'm beaten when I'm dead, not before,' he bellowed hoarsely. Torn by his fury and pain he rushed close in and struck. The axe-blade quivered and sank into the up-driving head, and again into the sloping grey back. A red gash the size of a scarf showed across the gleaming white throat of the rolling, squirming monster.

Trope laughed, with the axe raised in the air. Steel was the stuff to stop these reef-swine from playing up. Cold steel, with plenty of man-beef behind it. Whoost!

Just here the wounded shark doubled with the velocity of a mud-eel, its white belly raised clear of the tide. Trope dodged the down-slashing stroke and struck like a slaughterman at the throat. The blade hummed and held to the white flesh.

'That's done it. That's—' he babbled, holding to the long axe-handle. He must not let go. The tide was strong now. The cursed brute might yet force his way out, out...

Trope's feet slithered in the sea-grass, his whole weight bent on the handle. But even in its death-throes the shark was a flailing mass of muscle and hate. And the blade in its gullet jagged it to a final lurch.

The lurch brought Trope with a flying spin across its body. His head struck mud and water beneath the outspread fluke. And the fluke beat him down and down with the precision of hammer strokes. He fought with the water closing over him and the great grey body swinging above him in the tide.

KENNETH FANE had heard sounds during the night as he lay in

his hammock under the lugger's deck awning at No. 2 lagoon. The

reefs were full of strange noises and bird cries, the cheeping of

pigmy geese and herons, the shouting of the breakers at dawn.

A question of raising shell from a sponge covered hulk outside the lagoon took him in the dinghy to Saltwyn's house. The old man was examining some chart photographs of marine shell deposits when he entered the store-room. He looked up with a grin of welcome.

'Good morning, Fane,' he greeted 'You've come about that ugly sponge-bed by the look in your eye. But just now I want you to go with me to the hut to hand old tattoo-neck a job. There's no sense in letting him wander about the island. He's strong enough to nail shell-cases together. Come along.'

Together they walked in the direction of the hut, using the soft beach track in preference to the hard, lumpy coral path over the reefs. Glancing across the lagoon Kenneth indicated a dead shark drifting near the channel. From its gullet protruded a long axe-handle. Saltwyn stood transfixed at sight of the axe-handle: then he strode nearer the channel, his eyes kindling strangely.

'Trope at his monkey tricks,' he half shouted as the gashes on the shark's body became visible. 'The fellow's crazy. Why does he go out of his way to hack one of my old pensioners to pieces?' he stormed, pointing to the axe marks on the blue head and throat. 'For the last eight years that old reefer has been a useful scavenger. He has always respected the presence of my divers and kept the water clean. Blast Trope! He shall answer for his tricks.'

Kenneth was exploring a metal cylinder fastened with a line just above the propeller fin. A sudden suspicion crossed him. He glanced quickly at the old man. Saltwyn was also regarding the cylinder attachment.

'You see,' he explained slowly, 'it's a Decroix submarine camera I've been experimenting with for a long time. Last year I got a picture from it at five fathoms, showing oyster-spat on a bank fifty miles from here. Only a Frenchman could have invented it,' he went on thoughtfully. 'It can be timed and flashed to a click. It occurred to me I might use old Bill, as I called the shark, as a picture-getter. I'm looking for new shell grounds, Fane, and there was no harm in letting old Bill loose with a camera among the banks and reefs. The machine has a chronomographic attachment that sets the locality to a minute.'

They found the body of Trope in the channel itself.

TWO days later the mission steamer anchored in a fairway

outside the channel. Saltwyn and Kenneth went out in the

whaleboat for letters and stores. There was very little news, but

plenty of stores, including Miss Molly Saltwyn, aged nineteen.

The old man shouted in his joy, the man whose nature had been

warped by his solitary existence, and whose bitter voice had once

sounded like a scourge among the reefs and inlets.

Kenneth Fane was immediately offered a chance to return to Sydney in the mission steamer. The tubby little skipper gave him an hour to make up his mind. Curiously enough, the sight of the sweet-voiced Molly walking up and down the beach with her babbling, overjoyed parent decided him in five minutes. He stayed on.

For young gentlemen of fortune the islands have many fascinations, but not always do they provide a Molly Saltwyn. In the store the following day, with Kenneth and Molly beside him, the old man took his twelve pearls from the safe and laid them in his daughter's palm.

'When you are able to match them with twelve others, Kenneth Fane, we'll draw up a deed of partnership,' he intimated with a laugh. 'In the meanwhile Molly will act as stakeholder.'

Kenneth went back to his work with a will. And the sea in her pity gave him the fairest of her gems, until the eager, trembling hand of the stakeholder was filled.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.