RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

PETER'S pipe was seven miles long. It carried oil from the company's wells at El Marash to the refinery overlooking the Gulf of Akbar. To Peter the surrounding sandhills recalled Suvla Bay. Desolation throbbed in every pulse-beat of air. It was hotter than Bourke at its worst, a strangely dementalising heat he had never experienced in his native Australian bush or desert.

The call of oil had carried him from Sydney to the company's pipe-line within the flaming, heat-drenched Gulf of Akbar. Andy Gordon, one of the Australian directors, had nominated Peter for the post of assistant surveyor in view of the fact that Moslem Arabic was the boy's pet study.

Peter's bungalow nestled in the shade of a dozen Lebanon palms on the crest of a sand-ridge. From this eyrie he had an uninterrupted view of the pipeline and works; also the blue sleeve of water that emptied with each tide into the historic depths of the Red Sea.

A strike was on at the refinery. The whole staff bad gone to El Marash to await a settlement. So Peter stayed in his bungalow to keep an eye on the deserted works. He had begun to loathe the Gulf of Akbar, the mirage-haunted dunes, and the fly-bitten Arabs lurking in every finger-strip of shade. His only companion was a forty-pound Australian bulldog named Bill.

Bill had once been a regimental mascot, and had marched with Allenby's buglers into Jerusalem and Baghdad. It all seemed a long time to Bill, dozing, chin down in the sand, his slit eyes waking only when Peter or the houseboy, Hasan, stepped to the verandah.

A LONELY life for Peter Trent, whose business it was to see

that wandering Bedouin and Arab dhow kept clear of his pipe-line.

The jackals were his only familiars. Like the Bedouin and the

dhow, these pariahs had a nose for the haunts of white men. At

night they fluted in chorus about his verandah, lean, yellow

carrion-snatchers that took steady toll of the company's sick

animals and carriers.

He had been a year in the company's service, filling the iron holds of the tankers with oil from the pipes at the sandbag pier. Once a month he visited El Marash in the company's car.

At El Marash was an American picture theatre, and Arlette Gordon, daughter of Andrew, the watchdog of Australian oil interests west of Basra and the Persian Gulf. Peter and Arlette had danced in the Consulate at El Marash, had wandered together under the green lamps of the old Mahommedan mosques, where the palm shadows were blue under the crystal intensity of an Arabian moon.

Gordon was a Barrier millionaire who had fought foreign oil interests with the strength of his dour mentality. Victory had come to old Andrew after years of pitiless strife and spending. A smile or frown from his steel-grey eyes made or destroyed men's careers in El Marash. Although Andrew liked his daughter to dance and make merry with the clean-minded young officials in his employ, it was never assumed that Arlette's smiles meant speedy promotion for her dancing partners. Strange to say, the reverse was often the case. For it was well known that the lovely Arlette gave her sympathy to the boys who somehow failed to make good. Her tender nature went out to these failures in life's grim battle. And the battle for promotion among the company's servants had grown fierce since Arlette's arrival. Andrew was emphatic in his belief that the slim-waisted youngsters with the dancing feet never got anywhere except on his daughter's toes.

The old Barrier director loved men of brawn and hair, men who could endure the sun or throw a barrel of oil over the skyline. And if a man's hair was red and his face tough as the hide of a sphinx so much the better.

Arlette had her own ideas anent the kind of toughness necessary in a man's face. Her father supplied all the toughness of manner she was ever likely to need. So in the spring of her youth she had turned to lonely Peter Trent for a change.

Peter once clouted a sailor for calling him a scented stiff- neck. Peter hated stiff-necks and picture-faced men. He would have preferred to live up to old Gordon's idea of manliness. There were days in the solitude of his bungalow when he almost regretted that his hair was glossy and dark; his legs long and streaky. For it was on record that the father of Arlette had stated that long-legged boys always fell down in a race.

PETER was returning from a long inspection of the pipe-line. A

big tanker was due at the pier in a couple of days, and strike or

no strike she must get her oil. He had attended to the hydrants;

the pier pipes were ready to fill her up.

Since the strike a number of petty thefts had happened at the refinery. Steel tools and kit-bags left about the deserted yards had gone missing. The Arabs stole everything but oil. And of late an old dhow, commanded by the notorious Ghouli, a slave-runner from the old Sudan, had been reported within the gulf. Ghouli was wanted in a dozen Red Sea ports for all the crimes in the Egyptian calendar.

Peter halted within sight of the bungalow and whistled loudly in the hope of waking Bill from his afternoon siesta. His glance wandered suddenly across the sandy gutter that separated him from the bungalow. A long fibre line was moving steadily along the gutter in the direction of the beach. Attached to this line were several knotted bundles of bed-linen and clothes—Peter's clothes. He beheld the last of his white silk tennis shirts, ties, and shoes, the dress suit he had worn in his last dance with Arlette, trail noiselessly away with the speed of a hawk. Peter held himself with an effort. Well he knew that a dozen filthy Arabs were dragging his belongings to the beach as fast as they could haul in the line. His flying start carried him into the gutter, where another surprise awaited him.

At the end of the tow-line that was guiding his personal belongings and most of the company's bed linen to the beach was the big-chested bulldog, Bill!

Bill's jaws had snapped on the line. The bulldog was enjoying a free ride in the direction of the thieves. It was clear to Peter that his house-boy, Hasan, had been clever as usual. Tying things to a line and sliding them to his associates was much safer than using a donkey. The kavass, or local patrols, often intercepted loaded donkeys. The tow-line was an inspiration.

'The black pigs!' But Peter raced after the disappearing garments, teeth clenched, his long legs scarcely touching the sand. 'Hold on, Bill!' he shouted. Arlette's picture's inside that dress coat! Stick, Bill; I'm coming!'

Bill's plug-shaped body seemed to sail over the dunes and disappear in a whirlwind of dust down the slope where the Gulf of Akbar gleamed in the sunlight. As usual, Bill had been asleep in the shade when Hasan handed the goods through the bungalow window. In a general way Bill loved movement and gesture. On principle he attached himself to anything that seemed in a hurry to fade away. And when his beloved Peter's dress clothes and et ceteras began to glide from the bungalow Bill took a dive, so to speak, and caught up with the game.

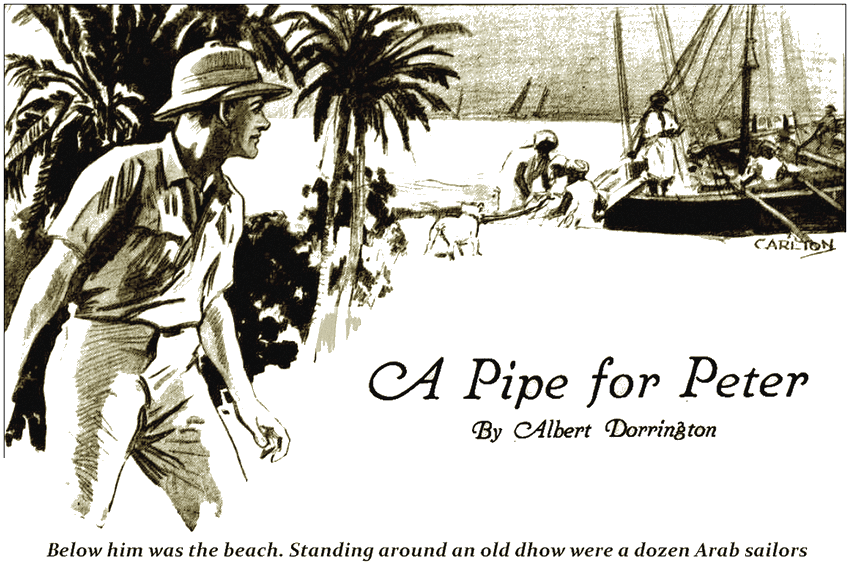

IN spite of the fact that Peter had once run a hundred yards

in a trifle over ten seconds the tow-line, with Bill attached,

improved on his record. It vanished towards the blue. Peter's

flying strides carried him to the last dune in the wake of the

disappearing rope. Then he halted as though a brake had been

applied to his long limbs. Below him was the beach. Standing

around an old dhow were a dozen Arab sailors hauling on to the

line. Their leader, a smart Arab in a red fez, his face pitted

and seamed as though it had been hewn from a pyramid, directed

their attention to the Australian bulldog at the end of the

line.

'By Allah, it is the laughing dog!' he rasped. 'The company's watchman!'

There was no need to indicate the palpitating figure of Peter Trent on the hill above. They parted like rooks at his coming, but only to form a ring round his swaying, gesticulating young body.

'See here,' Peter flung out to the wearer of the red fez, 'a man must have clothes to cover his ugliness, chief! You've taken everything I own in life, including my watch and the portrait of a lady.'

He pointed reprovingly to his dress coat and gold watch chain dangling over the line. Bill still clung to the rope-end, awaiting a sign from Peter. The dhow captain eyed Peter coldly for an instant; then he beckoned the crew to haul the line, clothes, and bulldog aboard the evil-smelling vessel. He checked Peter's advance with an upraised fist.

'Thou art well dressed,' he snapped in Arabic. 'We walk in rags.'

His black forefinger indicated the tousled, half-naked figures drawing in the line. 'Go back to thy wooden house,' he commanded darkly. 'Take with thee thy devil-faced dog, or, by the Prophet, I will fill both thy stomachs with sand. Away with thee!'

Again Bill looked up at Peter for a sign. The young pipe-line surveyor drew breath sharply, and then dived forward into the centre of the stooping gang. Luckily for Peter the muskets and knives of these Arab marauders were piled in the stern of the dhow. His rush hurled the leaders cursing into the water.

Pivoting nimbly he met the captain with a right swing on the mouth that shook him to his knees. Just here Bill let go the line and linked up with a squat dhow man who was fumbling with a knife in his belt. The pair went down together in a whirl of sand and Mahommedan oaths.

This did not prevent the crew closing on Peter. Fighting was their trade. Next to robbing a harem or raiding a village of women and children they preferred beating an occasional unbeliever to death. It was a short, savage encounter, with one forty-pound bulldog and a leggy young man hitting out for their lives on the sloping beach of Akbar. Peter went down with six shining black bodies rolling under and over him in a violent effort to pin him to earth, or garotte or pound him to insensibility.

One by one Peter flung them off, fighting with knees and fists and his good young brain. Like panthers these dhow-runners came back to the fight—a fight that provided neither sponges nor referees. They struck him on the face and over the heart. They kicked him with their bare, hard toes, and then reached for his eyes with their talon fingers. 'Chumak, chumak! Gouge, gouge!' they advised each other. 'He will not stop striking. Blind him. He will know better tomorrow! Chumak, chumak, brothers!'

Peter's movements grew wilder. His blows missed. Three of his assailants had fastened to his waist while a rope was strung about his limbs. They cast him flat on the beach, and licked their lips and wailed for their captain to speak.

The fight had gone well with Bill until a noose line found its way round his kicking body. A few deft turns and Bill's part in the fray ended. They flung him with jeers beside his master. The dhow's captain squatted on the beach and wiped a faint trickle of blood from his mouth. He had been struck by this accursed giaour! And, by Kismet, blood had followed the blow!

Near the company's pier were a number of stakes driven into the sand. At a sign two of the crew brought a couple of these posts and lashed them together crosswise. Without ado Peter was stretched out, his wrists and ankles securely roped to the timbers.

That was all. A very simple operation, accomplished without bloodshed. The dhow's captain rose from his haunches and stared down at Peter on the crosspiece.

'I could kill thee with a nod,' he stated coldly, 'for the blow thou gavest me. But now we will rifle thy house in peace, and leave thee as thou art. If thy star holds thy people may find thee,' he jeered. 'Thou art now in Allah's hands. It is written that unbelievers shall perish with dogs!' he added, with a scornful gesture towards the well-roped Bill.

The dhow's captain moved away in the direction of the bungalow, followed by his hungry squad. Peter heard them, an hour later, tumbling into the dhow and calling upon him to make his peace with Allah before the night came. The loud banging of their sail told him they were moving out to sea.

A SLIGHT breeze stirred the spindly palms on the crest above.

Sand, as fine as flour, fell on Peter's cheeks and lips. It,

seemed to rise and fall in waves about his limbs, sliding into

his pockets and settling like powdered glass in the hollows of

his clenched hands. The sun stayed in his eyes like the fingers

of a devil, while his thoughts raced in fiery wheels through his

brain. Once or twice during the endless afternoon his dry lips

framed a litany that became a softly babbled prayer for the

darkness to cover him. A coppery flare in the west showed where

the sun had set, A cool smell of night came to the beach but did

not relieve the growing pressure about his wrists and ankles. The

knots in the rope were like hammered iron. Bill wriggled inside

his bindings. From time to time faint mumblings escaped him as

his muscle-packed jaws worked towards the elusive rope strands.

Waves of sand flew into his tiny flat ears.

The fires of Peter's thirst started a beautiful delirium in which Arlette appeared, dressed in white and carrying a huge carafe filled to the brim with iced water and lemons. But the lemons and the iced water had a trick of fading over the horizon the moment he woke and called to Arlette. Always those lemons were in the greater hurry to be gone, he told himself with, a sub-humorous grin.

A cold night wind left him awake with his swollen wrists and ankles. Faint sounds came from the distant sandhills. Each breath brought them nearer. They came in sobbing circles, then in straight rushes, but always in his direction. Peter strove to ease the rope-grip on his right wrist, fought to draw his swollen hand through until his flesh quivered and throbbed with the pain of his efforts. A peculiar jackal odour blew round him. The muffled hoof-hoof of innumerable nostrils, followed by the velvet patter of paws in the sand, reached him. Lying flat on the cross- stakes he caught a momentary glimpse of eyes and ears pricking the darkness in front. Like dingoes they whimpered and drew nearer, testing and trying out each yard of space with their pencil-pointed snouts.

In his desperation Peter shouted at the circle of eyes and ears. The crack of his thirst-hardened voice caused the nearest jackal to skip back beyond the frisking tails of its comrades. But the inner circle of the jackal pack remained solid and determined to proceed with the investigation. Peter reserved his second shout until the furry head of the king jackal advanced boldly to the foot of the cross-pieces. Here the dry, hot snout nosed over his naked ankle before it set up a long-drawn yelp of invitation to its brothers.

'Shoo! Get away, you beasts!'

A dozen bristling heads and manes had bounded in, their paws striking like mallets on his half-clothed body. Peter's flesh leaped at the contact. He was conscious of the king jackal's spindly legs planted on his chest, the dry, hot muzzle snarling in his face, 'Shoo! Get off!' Peter's voice had lost its potency. Stiff-backed and snarling, the big jackal stood over him, as it had stood over scores of helpless victims along the lone camel tracks. Peter's lips moved. He was praying hurriedly to the vision of Arlette. And he hoped that she would never hear how this Arab's cross had been licked clean by hosts of desert pariahs. He knew that the boys would keep secret the real story of his end.

IN the middle of his prayer a strange thing happened. The king

jackal by right of its strength and grip was first to leap at

Peter's throat. A jackal's spring is as sure as a panther's

unless its attention is suddenly diverted. In its downward snatch

at the unprotected throat the big desert hound received an

unexpected shock.

It came from the clawed-up sand pile near the water's edge, from some torn strands of rope, scissored to pulp by restless teeth and jaws. Bill's brindled body arrived at the jackal's head with the impact of a six-inch shell. He seemed to fall amongst the frisking heads and tails with the speed of a champion heavyweight looking for a purse.

In its day the jackal leader had led the raving pack to the trail of many a sick camel and horse. They had clean-picked wounded army mules and blinded infantrymen. But the king had never been called on to stop a rush like Bill's. It was murderous, indecent. Long, long afterwards the jackal pack remembered Bill's amazing behaviour towards their leader. There was a hurried recollection of the king being worried and battered against the only rock on the beach, with Bill's jaws glued to the desert king's heart region. The diversion lasted about sixty seconds, and the king's howls for mercy melted into stuff thinner than air. Bill swung from his rock-pounded adversary and stared at the empty spaces around Peter.

A wisp of moon had risen in the south-east. The faint light beatified Bill, revealed the dumb sorrow in his eyes for the sudden and unexpected collapse of the jackal army.

Dutifully he ambled up to Peter and licked the rope-strangled wrists of the right hand. Then he moved around the cross and licked the other hand.

Peter opened his eyes wide. The cold sweat of horror was on his brow. What had become of the jackal? Bill's tongue played over, his lacerated wrists with the tenderness of a masseur.

Peter felt the cold clasp of dawn in his limbs while the bulldog trotted round and round him. Finally Bill lay down, his chin resting on the young surveyor's breast.

A poisonous smell of jackal still lingered in the air. Only a blast of dynamite or a heavily-shotted gun would move them from the locality now. While marching with the colours in Palestine Bill had gauged fairly accurately the habits of these sand-hill sleuths. He could feel their presence among the cactus on the high ridge. They would scout and watch for days. The tank of water with the dripstone beneath had been carried from the bungalow by the captain of the dhow. Bill licked his dry lips and nuzzled closer to Peter. He felt that it was going to be a long time between drinks.

Peter Trent fell into a sick sleep, in which he heard the soft fluting of the red pack on the hill above. Then he dreamed of a white-walled villa and garden, with Arlette seated beside him in the tender glow of an Australian afternoon. The fierce heat of the sun woke him. It was flaring high above the sapphire waters of the gulf. Bill's hoarse barking from the vicinity of the bungalow reached him. The unmistakable hoot, of a motor horn echoed through the sandhills.

LATER on—hours, it seemed—Bill appeared on the

slope, escorting a girl in a white dustcoat and veil. Bill led

her to the beach like an enthusiastic fisherman about to exhibit

the catch of the season. She paused an instant to draw aside the

dust veil. Then she saw Peter.

She was aglow to the warm light of the beach, a very real vision of health and youth, her tall, athletic figure silhouetted against the raw red of the sandhills. It is to Arlette's credit that she did not speak until her small but efficient penknife had sliced through his wrist and ankle ropes. In a few moments Peter was sitting up, rubbing and chafing his wrists with new-found energy and life. Arlette's capable hands were busy on his rope- reddened ankles.

It is to Arlette's credit that she did not speak until her small

but

efficient penknife had sliced through his wrist and ankle ropes.

'Accidents of this kind do happen in Persian territory,' she affirmed steadily. 'Arabs?' she queried, patting Bill's neck in token of her regard.

He nodded briefly as he shook sand from his hair and clothes. He wanted to suppress the idea that men have only got to dream of angels to produce them in the flesh. To prove his cheerfulness he tried to whistle, but the dried blood on his lips cracked the tune. She laughed in spite of herself.

'This kind of life won't do at all, Mr. Trent. There ought to be a real guard at this pipe-head—men with machine-guns and poison gas. These desert fuzzies respond to nothing else.'

There was pity in her voice, for she had not been unmindful of Peter's position in the company's service, his unwavering loyalty and sense of duty.

'They seem to have made a job of you,' she intoned with a sigh. 'You ought to be at the offices in El Marash. This location requires a really hefty guard. Dad was right when he said that boys with charming manners never won prize-fights. He always said you had charm,' she added, with suddenly twinkling eyes.

Peter's cheeks were steeped in red as she returned to her work on his ankles. He spoke with a big lump in his throat.

'Charm or no charm, I'd have put that Arab crowd into a can if there'd been another fellow named Peter standing by me,' he stated defensively. 'I wasn't in top-hole form yesterday, and the twelfth Arab was.'

'There were twelve, eh?'

Arlette bent to her task of reviving the blood circulation in his ankles. He could not tell whether she was laughing or angry. But he was grateful for the spiritual fragrance of her leonine hair, the soothing touch of her beautiful hands. He felt that he could kill all the Arabs in Persia if they so much as looked at her veil.

'I called at your bungalow after my tyre went flat,' she explained at last. 'Dad doesn't know I came. He's tootling the lunch at Selim's hotel with a party of directors. They'll hear something from me when they come here,' she promised sweetly. 'Allowing one solitary person to guard a million pounds' worth of property! How do you feel now, Mr. Trent?'

Peter struggled to his feet, shook himself vigorously. 'When I've had a bath I'll be fit to—' Arlette was responsible for the interruption. She was gesticulating towards the company's pier, where the big black dhow was making for the steps, her giant boomsail flapping weirdly in the light breeze. Peter's jaw snapped.

'The Arabs are coming back. They're scared of the gunboats—want to destroy evidence of yesterday's scrap—burn up the cross-pieces and what's left of me,' he told Arlette hurriedly.

Arlette was far from smiling now. Only for her flattened tyre she might have put a safe distance between Peter and these sea- carrion. There was no place to run or hide. A touch of dismay entered her.

THERE was no sign of panic in Peter. Yet a sick thought

entered his mind at Arlette's presence on the beach. The dhow was

rapidly approaching the pier steps. It was certain that the lynx-

eyed crew had seen the car on the hilltop and the figure of

Arlette crossing the beach. A sudden thought burned into his

young brain. He ran with sobbing breath to the pier, calling to

Arlette as he ran.

'The key of the petrol hydrant, Miss Gordon! Turn it, quick, for your dear life!'

He gained the pier head with the bulldog beside him. A number of small pipes trailed from the refinery to the pier end to feed a hose that hung from a wooden bracket near the steps. It was used to fill the tanks of launches and turbines. An out-of-date hydrant regulated the supply. The big key of the hydrant reposed within a sand-sheltered box a few yards from the pier.

Arlette knew the meaning of Peter's hasty command, knew what the turning of the key could bring about. The dhow was flapping: like a huge vulture under the lee side of the pier. The big, slanting boom came down with an ominous rattle. With his tattered shawl drawn about his bony shoulders the captain directed the casting of the line over the post, at the pier end. Arlette looked up from the hydrant as the key turned slowly.

'That man in the shawl is Ghouli Baba!' she sang out to Peter. 'Take care, boy! He is the Evil One. A single mistake and he'll make jackal pie of us both.'

Peter made no sign that he had heard Arlette. His face was white as frozen linen. There were going to be no mistakes on his part. Once the black horde gained the pier his strength would not allow him to stand between them and Arlette. In Ghouli Baba's eye was the yellow spleen of the snake. His lips parted in a fierce shout of joy as the line curled out from the dhow's side. It fell short by a few inches, but not before a long boathook had grabbed the pier and held the dhow fast.

THE dhow captain was first to the rail, his wolfish toes dug

in the wood, his gaunt body poised for his outward leap. In that

instant of frightful suspense Arlette saw a stream of petrol

flash from the hose. It struck Ghouli Baba with the sound of a

swishing blade across the face and eyes.

'Son of the Beast!' Peter volleyed, 'let this purify your abominable ship and destroy the murder stains.'

The force of a million-gallon pressure lay behind the slashing stream of petrol that poured over the deck of the dhow. Ghouli Baba pitched backwards, but recovered himself with an effort. In the fierce heat of the sun the fumes of the petrol deluge rose in suffocating waves.

'By Allah, we are undone!' the captain choked as the tide swung the dhow's head seaward. In a moment the current had carried her beyond reach of Peter's hose.

'We'd better go,' Peter called to Arlette. 'They might land on the beach and—'

A length of scarlet fire ran from the galley of the dhow. With a quick, fluttering movement it wrapped its burning length around the huddled figures of the men near the rail. A screen of black smoke enveloped them, covered for a moment the gulf of fire that roared over the boomsail and deck.

'The hell of their dreams has come true,' Peter muttered. 'Anyway, it was better than a machine-gun—much cleaner.'

Arlette followed Peter to the bungalow. A sudden limpness had come upon him. He lurched to the verandah stammering apologies for the unexpected faintness which had come over him. Arlette did her best to make coffee on the primus stove. The boy was famished, hurt, she told herself.

Sounds came from the road above them. A big touring car came sliding through the sand in front of the bungalow. Andrew Gordon stepped out, his face revealing the raw lines of his mental agitation. He had tracked his daughter to Trent's bungalow. Rumours of Ghouli Baba's presence in the Gulf of Akbar had reached him. In the last two years the notorious Arab dhow had abducted four white women from various beach stations. Arlette's glance went out to the smileless mouth and buckled brows.

'Hello, dad! You seem worried,' she greeted, a pot of boiling coffee in her hand. 'Do you want Mr. Trent or me?'

A black scowl sat on the old millionaire's face. For the last three hours he had been torn by the thought of her madcap journey to Trent's bungalow.

'I'd almost forgotten Trent was here,' he snapped. 'It won't prevent ye returning to El Marash with me.'

His lightning eyes took in Peter's outstretched figure on the couch inside the bungalow. The scowl deepened.

'Another man on strike,' he rasped. 'And my daughter ministering to his comforts.' He turned away almost savagely to his car.

Arlette followed, caught his arm, and turned his bitter glance to the black smoke pall on the distant skyline.

'That's some of your oil, dad! It represents the bath of fire Peter Trent gave Ghouli Baba and his gang of slave-runners. About a thousand gallons, I should say.'

Arlette then pointed to the refinery and works where the company's untold resources were stored. 'The smoke of Ghouli Baba's fire-sticks would have been over those tanks and buildings only for somebody's presence of mind.'

Andrew Gordon stared at the sullen smoke fumes on the skyline, his jaw grown slack, his brain slowly absorbing the meaning of his daughter's words. A drop of sweat fell from his brow. Arlette's fingers twined in his own.

'Go into the bungalow, daddy mine, and thank a gallant young gentleman for his services. It's much easier than having to write off a million pounds worth of destroyed plant.'

Andrew Gordon was a man of affairs and something of a sport. He took the coffee from his daughter's hand and stepped in to the bungalow. Arlette signed to the chauffeur in her father's touring car.

'Mr. Trent will return with us to El Marash,' she said. Bill rose from the verandah and took his place inside Andrew Gordon's car.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.