RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"TORPEDO" McVane sat watching the big-beamed excursion steamers as they hooted past his training-quarters at Point Hamilton. The surf raced and fell in thunderous heaps over the floor of the rocky basin below. A score of smoky-winged sea-fowl clung tenaciously to the dripping edge of shoal that thrust its ugly hip far beyond the breaker line.

One excursion steamer, bolder than the rest, ran close inshore to allow its passengers a better view of the man who was to contest the world's heavy-weight championship the following night. A score of binoculars were turned instantly on McVane, while a chorus of friendly greetings blew upon his ear.

"Torpedo" rose from his canvas chair and retired quickly from view. "I'd sooner punch bears in a twelve-foot cage than talk to those people," he declared to his trainer, Sweeney. "They mean well, but somehow they rattle my self-conceit."

Narrow-hipped as a lion, his lean, muscle-packed chest and jaw had with stood the constant batterings of a score of bitterly-fought contests. Admirers of McVane who looked for the sledge-hammer fighter in him came away disappointed. Instead of some human gorilla let loose upon a fear-stricken opponent, they beheld a handsome athlete nearing middle age, who, in private life, was frequently mistaken for a university "coach" or medical practitioner.

James McVane had chosen the "ring" as a means of livelihood rather than endure a life of servitude within some ill-ventilated office or banking-house. Until his fortieth year McVane, contrary to the predictions of sporting authorities, retained the world's heavy-weight championship. A score of younger aspirants had found his science and ringcraft unassailable. Often, after a few seemingly light exchanges, the aspirant would succumb to an unexpected "push" on the chin or body that left his audience wondering whether the contest had been prearranged in favour of the invincible Torpedo.

Experts thought differently, for, once in the ring, McVane had the rare gift of divining some weak link in his opponent's physical make-up, some anatomical defect which, sooner or later, became manifest under his demoralising assaults. It was claimed, by certain members of the profession, that these assaults were conducted with the precision of a bone-smashing surgeon.

The public had grown a little weary of his unprecedented succession of wins, and the boxing academies of Britain and America had been ransacked in the hope of unearthing some deserving genius capable of outstaying the ultra-scienced "Torpedo." Man-eating heavy-weights had been brought from Australia and New Zealand to accomplish his defeat ; the star ruffians of the ring had been hurled at him in vain. There were bar room fighters who rushed him in the hope of smashing his arm or jaw in the first thirty seconds; there were dwarf-like creatures, famous for their abnormal reach and monkey tactics, whose hope of victory lay in blinding or maiming their more humane adversary. All these had failed utterly, and it seemed as if McVane had permanently cornered the world's championship.

THEN, one white morning in March, a mysterious enthusiast came forward with an Unknown, a mere boy of eighteen, whose claim to the world's championship lay in the fact that he had studied secretly the fighting methods of "Torpedo" McVane.

A match had been arranged without delay. One of the conditions imposed was that the Unknown's personality should remain a secret until the eve of the fight. The unusual proceedings had no visible effect on the champion's nerves; so long as his share of the gate-money was secured he cared little for the advertising antics of local ring-speculators.

The usual time allowed for physical preparations slipped away without a hint of the Unknown's identity. Sweeney, who had trained McVane for his last dozen encounters, exhibited a nervous curiosity as the eve of the fight drew near. Who was this Unknown? What had his supporters to gain by keeping him in absolute seclusion until the last moment?

When the last returning excursion steamer had hooted its way past the champion's training-quarters Sweeney dispatched an assistant to the office of the Sporting Star, a newspaper which had supported the cause of James McVane. The assistant returned an hour later, after a brief interview with the Star's sub-editor.

"Well?" Sweeney met him in the doorway. "What's the name of the mystery?" "A chicken from school!" the assistant responded, wheeling his mud-covered bicycle inside the boat-house. "Young and juicy and ready for killing."

McVane strolled in leisurely from his canvas seat overlooking the surf-whitened bay, and smote the big punching-ball until it flew twice round the bar.

"Young and soft, eh?" he drawled, between the hits. "Anybody here know him?"

"Name of Norry Blake." The assistant stooped near his bicycle for an instant. "Son of a lady music-hall dancer who made hatfuls of money twenty years ago, and ended like most high-kickers—in the gutter. A lot of people here remember Mimi Blake," he added, straightening himself. "My governor used to talk about her wonderful turns at the Hippodrome."

McVane was about to side-chop the leather ball; he paused as though someone had touched him with a knife; his jaw hung sullenly.

"Why, Mimi's kid went missing after she died." His voice was harsh, almost broken, his nimble eyes had grown dull at the points.

His trainer regarded him thoughtfully. "The kid's come to life evidently. Still, it doesn't affect us, I hope?"

The champion did not answer immediately; his lips tightened, and then expanded into a mirthless grin. "Funny how kiddies spring up," he said, half aloud, "after years of hide-and-seek. First in London, then New York, and now here... to fight me, of all men!" he added disjointedly.

"Torpedo" remained standing in the centre of the exercise-room, a look of bleak incredulity in his eyes. The big leather ball swung idly within arm's-length.

Sweeney prowled near, marvelling secretly at his sudden change of manner, the monosyllabic replies which greeted his enthusiastic observations concerning the forthcoming battle.

"Blamed if the kid's name hasn't taken the spring out of him!" he confided to his assistants, an hour later. "Didn't you notice how it stopped him punching the leather?"

MCVANE retired to his private sleeping-den early that night, and settled himself before a blazing log-fire, which his attendant always prepared for him immediately after sunset. Outside he heard the low thunder of surf on the outer shoals, the coughing hoot of some steamer or tramp picking her way from buoy to light-ship at half speed.

McVane found no sleep for his tormented brain. The name Mimi Blake had stirred his sluggish memory with fiery whips. Sixteen years had passed since their last meeting, and her face peeped at him now, tear-scarred and swollen. He saw it imaged in the red flakes that fell from the slow-burning log, the eyes of fire, the lips that had once kissed his bruised cheek before he had learned to evade his antagonist's blows.

The thought of those early struggles hurt more than the fierce hammerings of a hundred fists—Mimi's struggles and his own. It was Mimi who had leaped first into fame, leaving him in the dull flare of the smoky boxing-saloons to work out his own destiny. She had left him to join Van Egbert's company of dancers, in New York, where a dozen high-priced engagements awaited her.

They never met again. Their son Norry had been taken away by Mimi's uncle, Gilbert Mostyn, a vindictive old tradesman, who regarded Mimi's marriage with McVane as the final act in her miserable career.

In their three years of married life McVane had contributed greatly to his wife's unhappiness. Swayed by jealous suspicions, caused by her growing music-hall popularity, he had often allowed his blind rage to overspill until she sank at his feet begging for mercy, praying that his berserk hands might not batter the life out of her frail body....

He sighed a little wearily now, as he recalled his ungovernable passions, the nights when he had driven her from the house into the rain-drenched streets to seek the shelter of her uncle's home, a grim, laughterless abode situated at the extreme end of the city.

And now, by one of Fate's savage ironies, his son Norry had been brought forward and trained secretly to accomplish his defeat. And through it all he detected the hand of Mimi's dour Uncle Mustyn, the man who regarded him as the cause of his niece's undoing.

McVane, as he stirred the reddening logs, divined the bitter enmity which Mostyn bore him. Surely no other creature could have manoeuvred so fiendish a plot! Father and son secretly pitted against each other in a roped arena... and the plot so cunningly arranged that only one of them could be aware of the fact.

The champion moved in his chair uneasily; his breath came in deep expulsions, while the clammy perspiration gathered on his cheek and brow. He knew that Uncle Mostyn had vowed to avenge the bitter humiliation which Mimi had suffered at his hands, the blackguard thrashings inflicted upon her young body, when hate and jealousy had overpowered his reason. Mostyn had taken Norry to America, where all traces of him had been lost. He had compelled him to bear his mother's name, and, in after years, had set himself deliberately to prepare the boy for a career in the fistic arena. It may have been that Norry exhibited an early trend towards the noble art, and that his youthful predilections had suggested to Mostyn the means of paying off an old score.

In the chill dawn hours McVane felt that the situation threatened his world wide reputation. It was ludicrous—intolerable. Any attempt on his part to interview Norry would be at once regarded as a grave breach of professional etiquette. It would be difficult for him to explain matters to Norry, even though his trainers permitted a message to reach him, which he felt certain they would not.

For years he had hoped that his son might be restored to him. He had even prayed from the depths of his blackguard conscience that the past might be forgiven when the hour of their meeting arrived. He knew that Mimi had forgiven, and he knew that her forgiveness had sweetened his after-life, had subdued the raging beast in him, helping him to the highest honours which his profession afforded.

It had caused men in two hemispheres to speak of him as the Prince of the Ring. And now, after a period of silence and mystery, Norry had flashed into public notice to dispute the honours which had been wrested from Martin Killian, Frank Hayes, and that human flail Black Montagu.

One thought comforted him. His son had reached manhood with the glow of battle in his heart and brain, a clean-limbed, dashing young athlete. How many men had met their sons in after years palsied and undersized, smitten wiih some incurable malady, unfit and unsound!

WITH the coming of day, and the saner life-giving warmth of the sun, the situation resolved itself into a more humorous light. Too much introspection was not good for men of his calling, he argued. Worse things might have happened to his son than a bout with one who knew how to blend science and humanity during the hottest moments of a contest. Norry would come to no harm, and the meeting would teach him to honour and respect the man he was henceforth to know as his beloved father.

To forgo an engagement on the day of the fight was unthinkable to James McVane. The united press of England and America would hail him the coward of the century, no matter how well he might plead afterwards the real cause of his retirement. He must enter the ring. The terms of his engagement offered no alternative, unless he fled the country or dragged out the story of his past to a jeering, unsympathetic public.

He lay on his couch and tried to sleep; but the face of Mimi came and plucked sleep from his lids. He rose languidly, and walked to the front of the boat-shed. Sweeney joined him instantly, and together they completed the final course of physical treatment that was to fit him for the coming contest.

The champion's sluggish actions im pressed the trainer unfavourably. There was an absence of spring in his gait, no nerve force in his glove-work; and, worst of all, as Sweeney soon discovered, he had not slept overnight.

In response to his anxious inquiries McVane laughed lightly. "I shall sleep this afternoon, and go into the ring to-night fit as a plug of dynamite," he said. "Let's try a walk on the beach."

Sweeney's uneasiness showed no abatement when the big Panhard car came throbbing down the track that evening to bear them to the International Sporting Club. McVane hummed cheerfully as the car swept into the wide avenue, where a great human stream surged and panted under the electric globes facing the Club entrance.

Shouts greeted the car the moment its occupants were recognised; and the champion was compelled to force his way to a private door, through which the crowd sought to gain admission.

"Keep your end up, Torpy!" The shout fell dead on his ears as he passed swiftly to his dressing-room.

Into the vast hall poured the serried waves of humans, professional men and clerks, artisans and labourers, until the great pit and galleries engulfed them.

Two minor artists of the ring filled in a twenty-minutes' wait before McVane, accompanied by Sweeney and his attendants, entered the roped enclosure. A roar of savage welcome greeted his coming, for in those days of comparatively short-lived reputations McVane had held the public eye longer than any of his predecessors, and they loved him for his clean record, his many swift and brilliant victories in the past.

THE entry of Norry Blake caused, at first, a sullen hush, that gradually broke into a tempest of applause. A mere stripling compared with the veteran champion, his appearance elicited a running fire of comment from the critics gathered around the ring. Too much of an Apollo, too finely knit, they predicted, to live through one of "Torpedo's" bone-smashing operations.

McVane sat in his corner, and his eyes leaped to the boyish figure that bowed in response to the hurricane of applause. A strange delight and pride thrilled his blood now, as their eyes met, for in that first glance the champion saw his own image and likeness in the broad-browed stripling who had come to wrest his hard-won laurels.

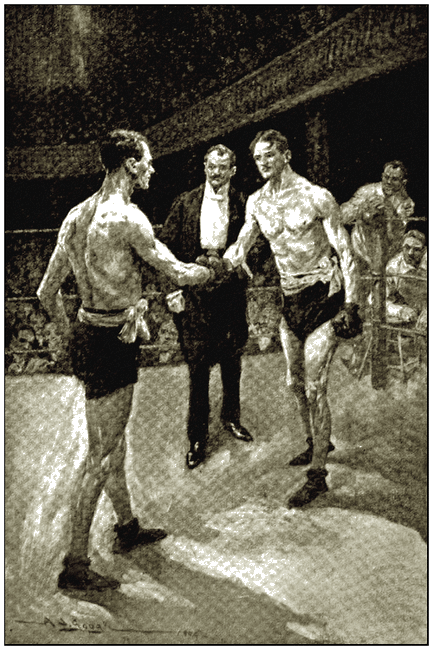

The resemblance between the two men was noted by a large number of critics, and when they crossed the ring to clasp hands the similarity in poise and carriage was even more marked. McVane had put aside all thoughts of explaining the situation to the assembled pressmen or referee. The great audience gathered from all parts of England and America would fiercely resent any disclosure on his part likely to forestall the most interesting engagement of modern times.

When they crossed the ring to clasp hands the

similarity in poise and carriage was even more marked.

Uttering the customary formula, the referee slipped aside, leaving him staring into Norry's eyes. Curiosity born of years of waiting held him rigid for the millionth fraction of time. But never till now had he felt how complete was his own mastery of the game....

The boy's face seemed to recede farther into the white flare of throbbing light, a face that regarded him with child-like curiosity, that turned swiftly to one of implacable hatred. He sought for an instant to evade the darting, questioning eyes, until the face leaped to him, driving before it a stinging, up-smashing left.

The champion broke its force with a smart shoulder-hit, while the muscles of his heart and brain seemed to recoil from the impact.

Norry panted at arm's-length, square-browed, alive to the machine-like technique of the man whose hands flashed up and out from impossible angles, staying his panther rushes without inflicting the slightest pain or anguish.

The crowd fretted impatiently as the two men hung apart, and the growing murmurs of protest jarred on McVane's ear. His left fist darted out and was stopped cleverly, Blake's right crossing with a sounding bang on his mouth.

The blow steadied McVane. A drop of blood big as a prune fell to the floor; his eye followed it stealthily, and there came to him a feeling of tremendous exultation at sight of his son crouching nearer, the beautiful straight limbs, the tremendous reach and courage. His own son, he told himself between heart-beats, his own son, and—

McVane met his rush with a lightning left, and then clinched unexpectedly to save himself from the trip-hammer returns that almost blinded him.

"Youth and age!" some one yelled from the crowd. "The kids will be served!"

The gong sounded corners.

Hundreds of eyes noted the champion's swollen features. His assistants sprayed and fanned him dexterously, and they marvelled at the new man's science and judgment. McVane breathed heavily in his chair, and again his eye wandered to the red stain in the centre of the ring.

"Blood for blood," he muttered, under his loud breath. "Mimi, your little son is squaring your account."

The call of time sent him across the ring wary as an old lion, his brain and eye awake to his son's slightest movement. The idea of defeat had not entered him. His one desire now was to win; all thoughts of love and kinship must be put aside for the honour of the game.

"Good old Mac!" came from the rippling sea of heads and faces. "Shake him up. Give the kid his comforter!"

The champion smiled grimly. Wisdom garnered of innumerable battles was reflected in his eyes. He feinted and led with the craft of a duellist, hoping to bring the round, boyish chin within striking distance of his deadly left. He danced from Norry's shooting blows, winced away when the lightning upper-cuts tore through his guard, while the crowd yelped in sheer delight at the youngster's brilliant method of attack.

McVane grinned amiably as he sought by head- and foot-work to tire the pink-cheeked stripling who evaded his chopping blows and who cross-countered so persistently. In and out the boy leaped, with the nerve-destroying energy of a typhoon, while McVane, through a mist of love and hate, marked the plump, round chin that must, sooner or later, receive its brain-jarring impact.

The champion had lived through similar ordeals when manoeuvring to outstay some less experienced opponent. And the vast audience roared its appreciation as he endured smilingly the long-distance blows that fell with a whooping sound on his face and body. There was no in-fighting. Like a gunner at his work Norry stood away, utilising his extra reach with studied precision. Then in the fourth round his tactics changed. With the courage of youth he permitted his skilled opponent a closer delivery, and the palpitating critics in the front rows waited for his instant undoing: a slip of the foot, a badly-timed hit would see the end of another would-be champion.

MCVANE returned to his corner like one who had passed through the eighteen Gehennas of Mencius. The change in Norry's tactics had not improved his chances. Blood oozed from his mouth; a bruise that resembled a hammer-stroke grew large on his brow. Something within him was crying like a wounded child—a new-found despair that turned his heart to ice, his courage to water. For the first time in his career he felt that his science had ceased to serve him. The power of his matchless art had grown limp and uncertain. He had seen Mimi's face looking at him through Norry's eyes—the bleak little face he had so often pulped with his great hands....

The tumult in the vast building rose and subsided in a kind of swooning roar. Men called to him from the grey zone of upturned faces. They told him in their savage jargon that his honour was at stake. A pitiless enfilade of predictions buzzed on his roused ear. A hooligan, with a knife-blade voice, called upon him to get up and pound the shaking heart of his boy-adversary.

He rose at sound of the referee's call and limped stiffly across the ring. The mark on his brow pulsated and throbbed. A dozen Norrys stood tight-lipped, crouching in the livid flare of the light. The faces followed him round the ring as panthers follow a wounded steer. Then a pat of a foot and a blinding smash between the eyes. Norry's face receded craftily amid Niagaras of applause. The blood-mist which had bothered McVane rose hot as fire-smoke for an instant; the next saw him across the ring, driving, smashing with both hands at the boy's set face, and each blow sounded on his ears like the beating of a heart. It was Mimi's face he was battering again, the face of the little dancer who had often cried to him in the rain: "Oh, James, James, don't strike again. Think of the child!"

Here was the child avoiding his blows with Olympic ease. Hate blinded him for an instant. All the venom he had once nourished against the miserable little woman lived in him now; it quickened his dying strength until the crowd shrieked and applauded his efforts. He felt the youthful body shrink from each scienced stroke; he saw the face of his son whiten in the electric flare even as it slanted within reach of his terrible left. "Now, now!" screamed the multitude. "Oh, Torpy, now!"

McVane stood transfixed in the ring-centre, dazed and bewildered by the storm of human voices. Then he rocked forward to his knees, a stammering, incoherent heap.

Norry stooped over him with scarce believing eyes, and waited until the referee had counted him out.

JAMES MCVANE, ex-champion of the world, awoke next morning stiff and bruised after his meeting with Norry Blake at the International Sporting Club. His attendants gathered around him consolingly, yet with a certain diffidence of manner which betrayed their disgust at the unlooked-for result of the classic encounter.

"A man can't go on winning for ever," Sweeney admitted. "But I could have sworn that he was yours in the last round, Torpy."

McVane grunted a little sullenly as he rose from his couch and prepared for his morning bath. His dreams had been invaded by a dead woman's face, a face which had looked at him through a hurricane of fearful blows. And he was not inclined to listen patiently to his trainer's views of the recent battle.

A motor whirred down the track leading to the boat-shed. An attendant came forward and whispered a few words to the ex-champion. A moment or two later Norry Blake appeared in the doorway, his right hand held out somewhat uncertainly. McVane turned sharply at sound of the footsteps, and in a flash found himself gripping the outstretched hand. Sweeney gaped in surprise at the unexpected meeting, and retired a little distance from the shed to await developments.

It was evident to the attendants that Norry had come to explain something. His whole being seemed to pendulate between excessively high spirits and a passionate outburst of self-reproach.

"I came here," he began, with diffi culty, "to express dissatisfaction with the result of last night's contest. I feel that I am not entitled to the victory; I feel that something has been withheld from me," he added brokenly.

"Norry, my boy"—McVane conducted him towards the gymnasium—"you gave your father a lively twenty minutes last night. I suspect it was Uncle Mostyn who put you up against me."

Norry stared into the ex-champion's eyes as though he would cry our. "It was Gilbert Mostyn who paid my training expenses," he confessed eagerly. Something in McVane's presence drew the warm blood into his cheeks as he accompanied him to the privacy of the gymnasium.

The ex-champion appeared to have forgotten the events of the previous night in the sudden coming of his son. Very briefly he dwelt on the cause of their separation, Mostyn's unspeakable trickery, together with his own unpardonable shortcomings in the past.

Norry listened for a little while, and then dropped into a chair, covering his face with both hands. "From the day I showed an inclination to enter the ring Uncle Gilbert spent money in preparing me for a meeting with the great McVane," he said, with an effort. "It was he who informed me that you had trampled my mother's name in the mire. The thought turned me to a human tiger when I climbed into the ring last night."

Norry's loud sobbing disturbed McVane. Stooping over the bent shoulders, he allowed his hand to rest on the boy's lowered head.

"No man ever regretted his past more than I, Norry. Last night saw my slate wiped clean—the sins were fairly hammered from it," he added grimly. "I hope Gilbert Mostyn enjoyed the way I faced the music."

"But you knew who I was," Norry protested. "I robbed you of the world's championship because you allowed me."

McVane broke into loud laughter. "Seeing that the world's championship is still in the family, Norry, we'll allow the newspapers to argue out the genuineness of your claim."

Half an hour later, when Sweeney passed into the gymnasium, he found the two champions chatting earnestly in the sunlit doorway overlooking the bay.