RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

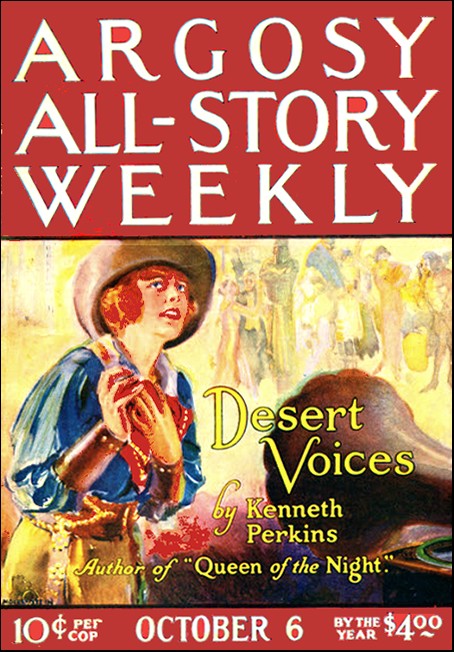

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 6 October 1923, with "Little Dark Ships"

LITTLE Kum Ling sat cross-legged in the darkness, his glance fixed on the candlenut flare in midstream. Now the darkness of Beetle Creek, at midnight, was enough to make a Chinaman blink and fumble. Above his head was a solid canopy of mangrove forest. Not a star gleam penetrated the quilt-like roof of dripping foliage.

Out in the black scum of the river floated a barrel-shaped cage. From the top of this wire cage burned the candlenut flare. Four stakes driven into the mud held the cage in position. For years little Kum Ling had sat thus, peering through the Stygian gloom, listening to the chut-chut of the Papuan poison drip, oozing from every root and reef that bordered the impenetrable swamp.

And always with the same happy result. For out of the mud and slime of innumerable centuries came that which Kum Ling most needed, money and gifts, light and opium. Also it brought him the love of his children and the blessing of his aged father in Soo Loon.

Kum's legs had warped like Cupid's bow through watching the face of the creek. Yet in a little while he would be free to pass his evenings on the divan of fat Ming Boh at Samarai, where the smoke of heaven smoothed the warps and stifled the five squealing devils in a man's heart.

Suddenly the flare on top of the cage in midstream began to jazz and shiver in the sheer joy of motion. Kum batted his eyes and grinned.

The jazz motion increased to a frantic, witch-like dance. It was as if a thousand horses were straining to snap the cage from its moorings. Up and down and round it milled in a whirlwind of mud and white fire. Kum crouched low to avoid the blasts of water and stones showered to the bank.

In a little while the flare grew steady enough to reveal a twelve-foot alligator floating dead on the surface of the creek, its great snout imprisoned in the open shaft of the barrel-like cage.

With a long boathook Kum unhitched the cage from the four stakes and drew the huge saurian to the bank.

Always these monsters of the mud were attracted by his midnight flares. And the flare could only be properly investigated after the inquisitive one had thrust his snout into the tunnel of temptation. Always this night-magic had to be sniffed at close range. And never once had the long, thin blade of steel omitted to shoot up into the soft throat, the moment the saurian tried to withdraw.

Kum anchored his catch to the bank, and in the light of the flare stripped the hide from the warm, flinching carcass. It was a tedious business in that sweltering gehenna of mangroves and mosquitoes. But the clean-stripped hide meant gold from the check book of the Sydney merchants; it meant one day closer to the life of ease and rest he had promised himself in the near future.

Moreover, there were certain parts of the white flesh that tasted like chicken when fried in his copper pan. A little pepper and boiled rice added made it a dish fit for a mandarin.

"Five pons for the pelt," he muttered. "Twenty more pelts an' I finish. Under these devil trees the air is black. My lungs grow weak. But my children go to school, my father blesses me. What does the bad air matter!"

The dawn showed like a tiger's robe flung across the naked east. The sea mirrored each tawny smear of the far-stretched robe until it changed to the milk-white garment of day.

Above the booming note of surf Kum caught the crisp sound of a naked foot on the pebbles. The little Chinaman peered from his hut door at a white man, standing ten yards away in the shelter of a bhutang tree. He was young and half naked. Down the smooth length of his boyish limbs were the red scars from the reefs he had struck. His skin was biscuit brown; his dark hair dripped brine and weeds.

He stared hard and inquiringly at the Chinaman, like one counting the last throw in a desperate gamble.

"Hello, Chink!" he said without moving nearer. "Got any grub, or coffee—in the name of God? I'm beat!"

Just here his young legs seemed to abandon him. He fell in a heap in the sand.

It is said that pity entered the Chinaman with the dawn of the human race. Ling knelt beside the boy and poured some whisky through his clenched teeth. Then he chafed his wrists, and with the instinct that is older than the apes, he massaged the flesh under the faintly beating heart.

"You come along just now," he said cheerfully. "Plenty coffee, bymby. Hi, ho; you sit up, boy! Sun too strong, heah!"

Instead of sitting up, the boy slept for five hours, like one whose body has been beaten and drugged. Over his half naked limbs the Chinaman placed a screen of palm fronds to shelter him from the blistering sun.

When he woke the Chinaman was holding a cup of strong coffee to his lips. The boy sat up and with curious glances at the sun, uttered a suppressed cry.

Kum patted his arm soothingly. "You keepee quiet. Takee pull. Why fo' you worry?" he spoke with almost womanly tenderness.

Gulping the coffee, the boy ate ravenously of some fried bananas and rice placed before him in a tin pannikin. Between each hurried mouthful his eyes made lightning darts across the surf line, where the reef formed a whaleback silhouette against the sun's fiery rays.

"I'm going to remember you as a pal, Chink," he said at last. "And I'll say it of your kind,” he added with an effort, "you never put it over a white man!"

The Chinaman's soft eyes explored the shreds of canvas clothing that clung to the other's body, a wan smile crinkling his saffron face.

"You bin in chokee!" he intoned with a sigh. "Wha' fo'?"

The boy's shoulders twitched, while the ghost of a grin touched his dry lips. "For killing a man, Chink! Name of Conlon," he added with startling brevity. Then, as if overcome by his undue lapse into speech, shook himself like a collie that has taken a thrashing.

IV"I'm as full of sea water as a bilge pipe," he confided after another cup of coffee. "And those bluenose sharks are man hunters, too!"

"You swim heah?" The Chinaman's eyes widened in stark amaze.

"How else? Boats are not included in chokee regulations. The last prisoner who made his get-away through the swamps is still in the mud. Slipped through a porridge hole among the big eels," he added with fervor. "I took my chance with the sharks!"

"Why fo' you run away?" Kum demanded blandly.

The boy chafed the reef wounds on his hips and body thoughtfully, and again the apologetic grin softened his tense, drawn features. His fingers played about a tiny miniature, fastened by a string to his wrist. The sea water had softened the knot that held it there. He regarded it thoughtfully.

"Why does a man run away from prison? Why does a man limp out of hell? Ask the sharks and the eels, Chink. They're good guessers."

The Chinaman shrugged and was silent.

From the forest track that led to the interior came the long drawn baying of hounds. The sounds rose in fleeting sobs and died away somewhere in the black smudge of bhutang jungle in the north.

The boy nodded and grinned again. "The police and the pups!" he said softly. "Blood money for the black trackers when they get me, Chink! What's the betting?"

Despite his easy manner the Chinaman detected a flash of despair in his eyes. Well he knew that the Samarai police were on the fellow's trail. Not a reef or palm belt within fifty miles of Malanga jail would remain unexplored by the sleuths of the law.

Moreover Kum Ling had known Mike Conlon in his day, and was dimly aware that the noted desperado had met his death at the hands of one Chard, a schooner hand in the employ of Conlon. A year before the noise of the affair had blown over the North Australian parts and around the pearling banks of Thursday Island. But beyond arousing a few caustic press comments anent the growing slackness of the police administration of New Guinea in general, the incident was forgotten. Even Kum Ling could not remember the cause of the shooting.

The voices of men and the baying of dogs converged slowly but surely in the direction of Beetle Creek. The Chinaman shuffled in and out of the hut uneasily.

"Maybe they come heah!" he muttered. "Yet there is no trail of him across the water!" He walked to where Chard still crouched in the beach sand and eyed him narrowly. "The police are comin'!" he announced gravely. "There is no place for you to hide!"

Chard leaped to his feet, but the Chinaman's hand restrained him. "Yo' make blood trail foh the dogs if yo' move flom heah!" he warned. "Why make trail?"

Chard remained rooted, his shapely bare feet planted in the incoming tide.

"That's sense," he answered with a quickening of his numbed faculties. "And—what next?" he questioned almost wistfully.

"No next if yo' move an inch!" the Chinaman told him. "Keep your dam feet in the water!"

It seemed hours before the Chinaman spoke. The clamor in the bhutang forest grew louder each moment. Ever nearer it drifted. The high pitched voice of the tracker, at variance with the dogs, beat shrilly on the tense silence of the beach.

Kum listened until he caught the sound of a white man's voice calling angrily to the dogs. He turned quickly to the expectant Chard.

"One white feller, commissioner of police is heah! Mistah Lester. Welly big man. He come to catch yo' himself! Him one great man in New Guinea. Evelybody kow tow to Mistah Lester!" the Chinaman babbled in his excitement. "He no likee me fo' havin' yo' heah!"

"Damn him!" Chard fumed. Already he felt the iron bracelets clicking over his wrists.

"They are comin'!" the Chinaman quavered. "One black fellow tracker, two dogs an' Mistah Lester!"

Kum's glance wandered across the beach and back to the Stygian gloom within the mangroves. Well he knew there was no hiding place the Papuan tracker could not ferret out. And Kum was certain that this straight-limbed boy criminal had made up his mind to finish his woes on this clean strip of beach. There would be no going back to Malanga jail. He was going to fight, and that would mean a speedy close to his young life. The bloodhounds and the black tracker would kill him like a hare.

The Chinaman's glance settled on the unsullied alligator hide, pegged out in front of the hut. He gestured frantically to Chard.

"Yo' keep your feet in the water, an' walk along to creek. Savvy? Quick; along creek, yo' heah?"

Chard met his glance and saw something of the death comedy in his soft, slant eyes. But Chard obeyed.

Kum Ling dragged the big, twelve-foot hide through the rotting grass until the darkness of the mangroves was reached. Chard waded thigh deep through the mud and reeds, and then halted, watching the Chinaman with fierce, questing eyes.

Two hundred yards away, in the bhutang scrub, the short-clipped voice of the police commissioner was heard, rating the black tracker. The two bloodhounds thrashed from the scrub and ran in the direction of the hut.

"Lie down!" the Chinaman commanded Chard.

"In this filthy mush?" the jail breaker objected, squirming at the thought of the viscid horrors that lurked underfoot.

"Lie down!" the Chinaman insisted. "Me chuck this skin ovah yo'! Maybe they pass it by. Maybe not. Allee same yo' get one chance foh your life. Lie down!"

In a flash Chard understood. Flinging himself down in the mud, he allowed the Chinaman to stretch the skin of the bull alligator over him. Very carefully Kum Ling folded the pliant hide about Chard's supple limbs, adjusting the head and throat piece with the skill of a taxidermist.

Then he paused to scrutinize the effect of his work. Within the gloom of the mangrove swamp it would have been difficult for an inexperienced onlooker to single out the skin from the network of roots that enmeshed it.

"Lie still, boy! The black tracker man is Motuan. He worship alligator allee same as Chinaman worship joss!" he chuckled. "Tracker no disturb yo' unless—"

"That damned white commissioner and his dogs dig me out!" came in muffled tones from the hide. "I'll lie still enough. Here they come! Get!"

A pair of bloodhounds loped through the hut door and remained sniffing and panting, their jowls adrip. Kum Ling stirred the coffee in the iron pot over the fire. He was about to add a pinch of salt to the bubbling brown mass in the pot, when his glance shifted to the clean cut figure of Commissioner Lester in the doorway.

Ling dropped the salt into the coffee and wiped his fingers on his neck-cloth. Then he salaamed obsequiously.

The young commissioner of police observed him casually, and then spoke sharply to the intruding hounds. Instantly they ran out into the open to join the flat-browed native tracker skulking in the shadows of a bunya palm. Lester was in his thirtieth year; his saddle-brown skin spoke of his restless campaigns against the lawless black and white men who clung to the forests and rivers with apelike tenacity.

His face marked him as a humanitarian with a flair for order and settlement. In the senate of the commonwealth his name stood for square dealing and justice. He glanced around the hut and nodded to the expectant Ling.

"Plenty alligators in the creek, Kum!" he greeted. "By and by you'll be bringing your family to help in the daily work," he added encouragingly.

The Chinaman's head wagged like a spring-fitted image at Lester's genial remarks. "Yes, sah, I bring um lille Ling boys to help catchum alligator. Alligator one big fool, sah, to fuss round um light. In goes his silly head. Click, clack goes the knife under his neck when he pulls away. Harder him pull, harder goes the knife. My word him one dam fool!" he added with Celestial gusto.

Lester was not the man to ask questions about escaped prisoners. His searching eyes ranged the creek banks, the beach, and the flat, foot-beaten tracks around the hut.

The bloodhounds had joined the native tracker. For a while they ran about, disturbed by the scent of the dead alligator.

Lester joined them, and stood with his face to the beach where the westering sun was aflame on the edge of a silvery cloud bank.

A sudden cry from the tracker swung him round. The fellow was holding a tiny miniature in his hand. It hung from a bit of loose string and had evidently fallen to the beach.

Lester snatched it from the tracker's trembling fingers, and stared at it with eyes that blazed darkly at the smiling face of the girl inset. Thrusting the miniature into his pocket, he walked from the beach, calling the dogs and tracker after him.

But the bloodhounds had become interested in a long, spiny object that sprawled in the mud-belt beneath the mangroves. Barking furiously, they circled within a few feet of the immovable saurian that remained still as a rock under their baying challenges.

Just here a curious thing happened. From the black slime of a bank in mid creek waddled a full-grown alligator. With scarcely a ripple it drove through the stagnant water, its great snout churning within a yard of the booming hounds.

With fear crushing his heart, Ling peered across the intervening space, and suppressed a chuckle of delight. Well he knew that the live monster was the mate of the dead bull alligator. Lester had halted and was watching results.

The two hounds were not to be denied. One of them had grabbed the head of the dead saurian, and with tigerish strength sought to drag it up the bank. But the head remained glued as though a live force was holding it in place.

Commissioner Lester watched with growing interest. But the unexpected was at hand. The tail of the live saurian whipped round under the feet of the hide-tearing hound. The stroke was unexpected, and the dog was hurled far out into the mud, the half-maddened alligator clashing and snapping on its heels.

The native tracker ran to the bank, gesticulating hysterically. "Ona pa nonga!" he called to the half-stunned hound.

The hound crawled ashore and ran from the saber-like jaws that threatened to dismember it. Lester watched in silence, a sharp frown lining his brow. He signed to the tracker impatiently.

"Almost the dogs were trapped!" he admonished in the vernacular. "Return, thou, to headquarters with them." He whispered some instructions in the fellow's ear.

Calling to the fretting hounds, the tracker turned to the bush trail leading to Putak and disappeared.

Very slowly the commissioner walked to the creek and halted beside the motionless hide. Stooping, he shook the scaly head, and then with an effort, flung it back.

With a catlike spring Chard leaped out, the muscles of his young body gathered for a clinch with his relentless pursuer.

Lester's service revolver covered him in the slant of an eye.

"There's positively nothing doing, Chard!" he said quietly. "You are mine—for keeps!"

CHARD'S breast labored painfully. The blinding sweat and mud from the mangroves obscured his vision. He rocked and swayed dizzily, and then steadied himself with an effort.

"All right!" he choked. "I've led you a dance. Only for those dogs I'd have beaten you and your damned administration!"

The commissioner pocketed his revolver like one certain of his man. He walked slowly across the beach, Chard following mechanically. At the water's edge he waited in the tense, hot silence for Lester to speak.

The commissioner beckoned the Chinaman. "Bring your table here, Ling. That old biscuit box will do for a seat."

Kum Ling obeyed tremblingly. Seated before the rough table, Lester placed some papers at his elbow and cleared his throat.

"A year ago, Chard, you were tried in the courthouse at Samarai, for the shooting of Mike Conlon. Is there any reason why the judge's sentence of penal servitude for life should not be carried out?"

Chard was standing six feet away from the table. He looked up with the jerk of a lashed steer at the cold eyed commissioner, seated on the biscuit box. A weary, scoffing smile split the dry mask of mud about his boyish lips.

"You're funnier than the old mummy in the court who threw me among the convicts at Poison River—for life, Mr. Commissioner! You know what the black gang is like out on those swamps!"

Lester flinched and twisted the papers under his elbow. "I've asked you a question," he said sternly. "The swamp and the black gangs at Poison River are still there—if you don't answer!"

Chard quaked to his reef-scarred heels. For an instant his brain reeled in the blind vertigo that catches men before they die. The white moisture of his agony crawled through the caked mud slits under his eyes.

"There was a reason why I shot Mike Conlon, Mr. Commissioner!" he faltered and stopped.

"It was never given at your trial. What was the reason?" Lester's face had become as pitiless as the mask of a savage. He was civilization's last gesture in that abode of crime and cunning. He was there to sift, punish or redress the bitter wrongs of native and white man alike.

Chard's eyes became alive with sudden understanding. This man was not like the others—the gang of courthouse wolves who had mocked and jeered at his silence, a silence forced upon him by the vicious minded old judge who had sought to drag a young girl's name into a story that reeked of crime! And in a court packed with the scum of the ports, yellow men and black, all agog for the name of the white girl for whom Chard had fired his fatal shot!

Chard's voice sounded clear in the silence. Behind his stiff, erect figure, the sun stooped like a huge blood drop to the rim of the sea.

"The reason I shot Conlon was for the reason that men shoot iron lizards and the snakes over there!" His hands gestured away to the mud bank. "I was a supercargo on board Cordon's schooner, White Witch. It was my second trip and last. I found that Conlon was owned body and soul by a slaver named Van Galt, in Songolo.

"Van Galt owns a dozen dives and gambling houses in Songolo and Macassar. He keeps scores of girls in his orchestras and saloons. It looks respectable until you see a list of his agencies that end in the cinnabar boats and the slave hells of Malay!

"I'm just a man like you, Mr. Commissioner. I didn't spend my employer's time fussing around the old wops and drunks who used to fill Van Galt's dives. But I jibbed at the cinnabar boats—manned by French convicts from Noumea—and the bleached sepulchres Van Galt made of the men and women who fell into his black holds.

"Well, the White Witch lay off Putak, one night, in October. Conlon asked me to go ashore and wait orders for cargo. Only a week before I had picked up a letter from Van Galt to Conlon. It was full of instructions for the carrying off of a white girl from Putak, and two others from Port Moresby."

The commissioner put his hand to his lips, as through a blood drop had welled from his heart. He did not speak. Chard continued:

"Conlon had friends everywhere; in the courthouses, in the customs, and among the native police. Van Galt's money did the tickling. And in a beach town like Putak, ten pounds will get a man or woman tied by the feet!

"Now, I knew the name of the girl in Putak, Mr. Commissioner. Her father's store had its back fence on the beach. Never mind who she is. She'd never heard of Van Galt or Conlon, or me or a score of other damned loafers ready to link her name with blackbirders and slave agents.

"Therefore, Mr. Commissioner, I bring you to that back fence that ran down to the beach. Instead of joining the boys in Rafferty's whisky shop, I burrowed into the sand and waited for Conlon to come right up to the fence. He came with the good old blanket on his arm, in case the young lady might start screaming. The schooner's dingy stood ready to pick him up, once he was clear of the house with the girl.

"It occurred to me, Mr. Commissioner, that I might wait until he came out with the girl struggling in his arms. It was past midnight, and some of Cordon's friends had been making merry with her father at Rafferty's bar. To put it finely they had made the get-away clear for Conlon."

The commissioner stirred uneasily. "Why didn't you go to the police?" he hazarded. "Unfortunately, I was away!"

Chard inclined his head. "There were two native police officers at Putak. Although I knew they were in Conlon's pay I could not prove it. If I had spoken to them, a prison door would have closed on me while Conlon finished his work. I took a lone hand chance.

"So I lay in the sand, under the fence, and heard Conlon stepping over the reef. He was drunk and unsteady, but not too drunk to climb the fence leading to her room.

"She had retired an hour before. I had seen her shadow on the blinds. Conlon crawled to the open window, and stood fumbling with the chloroform rags he carried. I dropped over the fence and called to him quietly. At first he did not hear my voice. But at sight of me he sobered and came at me with the rush of a madman.

"I fell over a tree stump and lay half stunned, while he tried to suffocate me with those beastly rags he carried. He was alive to all the tricks of the trade, Mr. Commissioner. No man in the islands could handle the blanket and the anesthetic like Conlon! He was as heavy as a Queensland buffalo, and could use his weight like a Jap.

"That was fair enough, but I jibbed at the blanket and the stink of the chloroform. So I pulled the only trick I had and shot him while there was time!

"Yes, Mr. Commissioner, I'd shoot such men at a shilling a dozen!"

It was almost dark now. The sea had turned to an oily smear, where the saber-winged hawks planed above the surf, squalling over some eager morsel snatched from the sandbars and inlets.

The Chinaman shuffled in and out of the smoke-filled hut, his eyes slanting toward the dim figure of the prisoner on the beach, and at the silent, tense browed commissioner of police, his hands clenched over the papers on the table.

He rose from the biscuit box, after what seemed like an eternity to the slow breathing Chinaman. In his hand he held the miniature of the smiling lipped young girl.

"Tell me, Chard," he said hoarsely, "where you found this?" He held up the miniature between his finger and thumb.

A sharp expulsion of breath came from the young convict as he stared at the face of the girl in the miniature. A curious, pensive blindness clouded his dark eyes as he answered.

"It was handed to me by a tot of a native child, one day at Poison River, while I was working with the gang. I don't know who sent it, and—I have never seen her in my life! But—it sweetened the air of Poison River. It was like a flower sent to a man in hell, God bless her!"

Slowly and with the air of one about to consummate an unthinkable act, the commissioner of police strode to Chard's side. For the millionth fraction of time the eyes of the two men cleaved the abyss of misunderstanding and lies that had yawned between them.

"Chard!" Lester's voice had lost its blade-edge intensity. It had grown mellow, but no less firm. "You were right about the men of Putak and the women they are supposed to protect. I am going to ask you to degrade yourself a little, by—"

"Say it!" Chard flung out, his shoulders braced as if for a blow. "Say it and be damned!"

"I want you, Chard," the commissioner spoke as though he had heard, "I want you to give me your hand!"

DARKNESS fell over the jungle-clad coast. A white launch swept into the inlet and made fast to the bank. The commissioner of police emerged from the hut accompanied by Chard.

For a heart-breathing space the two remained silent, while the slow beat of the tide marched with their thoughts into eternity. It was Lester who spoke.

"The launch will take you to Port Moresby. From there your passage to Sydney will be arranged. Write to me sometimes. Tell me about your people and yourself. Good-by!"

Chard halted with his foot on the launch's rail, his hand gripping Lester's.

"If you ever meet her in this life, say that I am content—that we passed each other like the dark ships in the night. And the ocean is wide! Good-by, sir!"

The launch disappeared in the blue darkness of the Papuan night.

Slowly, very slowly, Lester returned to the hut and found the Chinaman huddled over the smoky fire, for the air had grown chilly.

Kum looked up into the white man's face, a question palpitating on his heathen lips, for Lester was still holding the miniature in his trembling fingers.

"That—that lille lady I know welly well, sah! Her father keep um store in Putak!"

He pointed an accusing finger at the miniature. "She—"

"Is now my wife, Ling! And pretty happy as things go!" The commissioner of police gathered his papers from the table, which the Chinaman had brought in from the beach, and braced himself for his journey home through the forest. "Good night, Ling!"

He swung out into the bush track, halting a moment on the wooded rise for a final glimpse of the launch's pinhead light, fast disappearing over the skyline.

"And they passed each other like dark ships in the night!" he echoed with a sigh. "Never to meet, and somehow missing each other through all eternity! Thank goodness Eileen's happy! As for him—he's glad to be out of it!"

He turned again to the starlit trail, where the home lights beckoned, and the laughing-eyed little girl-wife sat waiting.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.