RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

With gold as the theme, gold dredged in the miasmatic jungles, this is a tale of the wilds of Papua and the still wilder human beings in those places, the out-posts of civilisation. Here is one of Albert Dorrington's best romances—pithy, direct, and devoid of the super-fluities of the ordinary story teller—full of go from beginning to end.

A BLACK river with the smell of a hundred dead forests on its bosom was flowing gently under the nose of Andy Mill. It was one of the malarial tributaries of the Joda, and there were men in Papua who believed that its bed was paved with gold. Andy Mull was sluicing and dredging for the New Guinea Gold Corporation. The river slid through countless miles of rolling jungle and quartz-strewn valleys before it reached Andy and his unwieldy dredge that shovelled up sand and ooze from the bottom of the river.

Andy's hut stood on the edge of the forest clearing, apart, from the crowded tents of the creek fossickers who came in droves from the Australian towns to comb the sands of New Guinea and wash gold from the viscid mud that had lain there since the dawn of creation. Men came in rags, shoeless and starving, to the back reaches of this Papuan poison ditch. And the only machines they brought for extracting the gold-slimes from these fever hells and swamps was an occasional piece of blanket and their naked hands.

Old Andy, working in his comfortable motor-dredge, pitied these vagabond 'sluicers' in their wild scramble to get rich. But, bare-handed, bare-footed white men are no match for the pestilential vapours of this mysterious land. With gold in their fists they died on the beaches under the palms or at their work within the poison ditch, where the yellow slimes trickled from the bosom of the earth, from between the bones of dead saurians that belonged to the nameless and forgotten centuries.

And then, in a night, it seemed, Andy found himself alone on the river. His assistants had responded to a far-flung cry of a strike committee that called off every machine hand and labourer in the employ of the New Guinea Gold Corporation. The staff vanished south, where the big towns offered modern comforts, whisky bars, picture shows, race meetings.

THE little steamer that had brought the strike mandate from

Sydney had also brought a letter to Andy from his daughter

Mollie. No other girl could have written such a letter. The big

drops of perspiration on old Andy's face bore witness to the fact

that the pen is mightier than river ploughs, tiger mosquitoes, or

blackwater fever.

Dear Dad,

This isn't to say that I'm coming to Slarfield Creek. But you may expect Clarence at any moment of the night. He has just left the big prison at Long Bay, Sydney. Tells me he picked up a good story. He's a journalist. I run an electric iron over shirts and things in a laundry. Be good to Clarry. He wants a change. You'll like him.

Molly Chard."

Molly Chard! And she hadn't even remembered to tell him that

she had married this fellow Clarence! Of all the wonders created

in a world of strikes, earthquakes, poison forests, and bully

beef, women were the limit, he told himself. His brow darkened

and his fists clenched at the thought of his clean-minded little

girl marrying a man from the whale-backed, red-walled prison at

Maroubra Bay. In his various mental preoccupations Andy had a

recollection of a person called Clarence Chard, who cropped up in

Molly's brief dialogues whenever he met her in Sydney. But that

was all. And the fellow had been in gaol! Molly had married him,

no doubt, in a fit of compassion while her young mind was mushed

up with grief and emotion.

Damn the fellow! His very name implied a state of imbecility on the part of his parents. Of course, he couldn't help it. But in the name of the eight Gehennas of the Chinaman why was Clarence coming to roost in Papua, the land that killed old army veterans faster than Dutch arrak or machine-guns?

With the help of his native boy Kini, who had just returned from a visit to his native village, a fire was made outside the hut and a meal prepared. Kini was unusually silent and morose. He spilled the boiling water over the fire, and evaded Andy's glances when the last of the tea-cups went crashing to the ground. Andy Mull became suddenly thoughtful as he lit his pipe.

"See here, Kini. I don't want a sulker hanging about these works. Up till now you've been a good fellow, alla same as white boy. But now you start playing up just because the camp's taken a holiday, and you're thinking of some fatheaded girl in your father's village," he said reproachfully.

Kini wriggled uncomfortably, his coppery skin glowing in the afternoon light.

"Me no sulk, taubada," he declared uneasily, and proceeded to spill more hot water on the fire.

Andy stood up, and his brass-buckled bell slipped from his waist into his big clenched fist. A few months before he had taken Kini from a slaving existence among the sago swamps of Taganowa, where he had been flogged daily by the headman and sent to work among the leeches. Until the strike he had served Andy faithfully. In return he had been treated kindly and had been allowed to visit his mother and sisters with unfailing regularity.

Kini looked at the belt in Andy's fist, and his face quivered strangely.

"You no whale um me, taubada," he begged. "When I leave um village today I hear big tale about um drunk fellers. Jacky Daw an' two other white man, who break trade-house at Poison River an' steal um Govement launch. My fader say Jacky Daw come along heah bymby an' shootee you an' me. Jacky Daw he murder old chief, Labango, one long time ago. Jacky want um Labango's canoe, an' fifty pon's Labango hide in house."

Andy stared at the boy as he replaced his belt. His lips had grown suddenly dry, but the muscles of his big arms leaped a little at the thought of Jacky Daw in possession of the Government launch. Daw was a member of a notoriously hard-drinking gang at Poison River. With a fast-moving launch and a couple of rifles he could play up with the small traders scattered along the rivers.

"All right, Kini," Andy said after a while. "Don't pull a face over that gasbag talk you hear. Somebody's always breaking loose in the hot weather. And I'm just about as scared of Jacky Daw and his leg-iron pals as I am of the blue cheese you brought me from Putak. I've had to watch that cheese, Kini," he added good-humouredly. "I'll have to buy it a pair of pants if it keeps on following me about."

Whereat Kini laughed loudly and busied himself with the fire and the shore-lines that held the company's unwieldy dredge fast against the outgoing tide. With the coming of night Kini rolled himself in a blanket beside the fire, where the drone of the tiger mosquitoes rose to a fierce wail as the night mists settled over the low-lying flats and swamps.

ANDY filled his pipe and strolled to the river, where the

dredge loomed among the tree shadows and vapours of the slow-moving stream. A slender steel crane projected from the dredge.

Attached to the crane was a river devil or rock grip that fished

boulders and snags from the river-bed. It was necessary when the

bucket dredges got to work that the floor of the stream should

present a clean surface to the big shovel-nosed scoops that

brought up the sand and slime.

Andy's eye wandered to the opposite bank, where the scarcity of timber offered few hiding-places for visitors with guns. A few bushes often gave shelter to a spear-throwing Maiheri or raiders from Kukuku. The only object that gave pause to Andy's sigh of satisfaction was the fallen trunk of a mahogany tree.

It weighed several tons. Half-a-dozen men could hide in the shadow of its great hulk. The natives called it the death log from the fact that its rotting cavities harboured scores of big green centipedes and poison adders. There had been efforts in the past to burn it, but the spewey river soil had saturated its red interior, and the fire-stick never got a chance. It had been Andy's intention for weeks past to shift the log by blasting. But at the end of his long day's shift he was too tired to tackle a job that promised no immediate reward for the expenditure of good dynamite.

He stared moodily at the log across the narrow stream, and then strode hack to the camp fire. Tomorrow he would put a charge of 'dinny' among the ants and centipedes that infested its interior. The infernal log could be turned into a barricade by the first bushranger who happened along!

AN imperceptible throbbing sound came from the river entrance,

where the white combers raved and thundered at high tide. Andy

listened, and then jerked himself into an upright position,

kicking aside his blanket and straining in the direction of the

sound. It was past midnight, with a few faint stars piercing the

fog-veil that shrouded the distant timber. Andy's heart rapped

with unusual violence as he listened. The voices of men reached

him now—blatant, irritating voices, accompanied by the

clinking of glasses and occasional hoarse, yelps of laughter.

Crawling from the camp fire, he moved nearer the sounds. The

green light of a launch appeared in midstream; the soft throb of

the motor told him that she was heading in his direction.

Andy Mull lay flat as a lizard on the wet ground. Jacky Daw and his crew at last! All the hair-raising stories he had heard of Daw's plunderings and shootings ran molten through his mind now. Jacky had terrorised whole plantations, demanding drink and money from the owners at the point of a rifle. An old game, but full of queer thrills when the game came to one's hut door with two other blood-letters to swing axes and machetes wherever they barricaded themselves.

"And there's a dozen cow-faced policemen playing bridge on that blamed courthouse verandah ten miles away!" Andy gritted. "These stall-fed cops make me tired."

He returned to the sleeping Kini and touched his shoulder gently.

"Get up, kid and bunk to the dredge. The gang's coming. By the holy fires, I'll fight 'em till the cows come home! Shift yourself, sonny."

Kini did the shifting after the manner of an electrified squirrel. Scrambling aboard the dredge, he crawled beneath some copper battery plates and lay still as a rabbit. Nothing spectacular about Kini, except his large brown feel that, protruded from the bulge in the quick-silver-covered plates. After him went Andy, but not to cover. The old sluicer stood grimly silent within the dark, covered deck-space of the dredge, a curious gleam in his veteran eyes as the howling, yelping voices drew nearer.

A SHADOWY shape was humped near the launch's wheel. In his

swift intake of the vessel's lines Andy recognised the stolen

Government cutter with its shining brass stern rail and cabin

skylights. A natty little water boat, he told himself, with a

piano and teak-fitted cabins for the use of the harbourmaster and

revenue officers.

The vessel hove to almost in the shadow of the dredge. Andy crouched back, his nerves tingling with a thought that sent the blood hurtling through his old veins. The shadowy outline in the stern disappeared below to join the fist-hanging, glass-clinking revellers at the cabin table. The sudden popping of a cork was followed by the chorus of an old South Sea chanty.

"This girl she waits in Grosvenor Street

This girl she waits in Grosvenor Street,

This long two years waits she.

And 'er heart may weep, but he's sleepin' deep

In the South Pacific Sea!"

It was Daw's voice and a big lump stole into Andy's throat as

he thought of his daughter slaving in a laundry to provide a

gallivanting ass named Clarence with a passage in New Guinea. And

these roistering chain-gang men were after whatever gold might he

stowed in the little safe within the hut!

Silently as a seal Andy thrust over a shining lever near his hand. In a moment the long slim crane, with the steel-hooked river devil attached to the swinging chain, glided over the narrow creek and stayed like the claws of a vulture over the big mahogany log.

"Longshore lassies came greet us—

Blow my bully boys, blow!

Bumboat men were glad to greet us—

Blow my bully boys, blow!

Sold our toys to buy bad liquor.

Pawned my pants an popped the ticket—

Blow my bully boys, blow!"

The teeth of the river devil opened and snapped on the bulging

waist of the mahogany log. A touch of the motor's hand-grip swung

the log high over the creek until it swayed directly above the

white-painted brass railed launch.

"His girl she waits in Grosvenor Street

That's hard by Sydney Quay."

Andy pulled over the shining lever.

The fangs of the river devil yawned wide. For a fraction of a moment the huge log slanted round like a black arm from the hot night sky: then it fell with a blinding crash from the teeth of the rock-grip.

In the bat of an eye Andy saw that the log had canted unexpectedly and that only the frayed and splintered edges had struck the narrow launch's rail.

"Mull's my name," he choked under his breath as Daw's song snapped in the middle and a string of curses came from the cabin stairs. There were a rush of feel, a sound of scuffling, and more oaths as the little crowd below fought to gain the narrow space above.

The lights went out, and Daw's voice and fists sought to restrain his drunken, half-maddened companions in their efforts to reach the deck.

"A branch from a tree, that's all, you frowsty wops. Steady, steady, while I get my gun. Overboard with our friend Clarence! Too many hands and feet on this little coffin. Over with him!"

A tall, boyish figure appeared for an instant near the stern rail; before the hands of Daw's men could seize him he had leapt over and disappeared in the Stygian gloom of the mangrove shadows.

Shrieks of laughter followed from the three drunken shapes peering across the dark water from the stern rail.

"He was no good to us," Daw bellowed, turning a drink-sodden face to the slim crane lowering sharply above his head. In that shifting glance he saw the bayonet-like edges of the river devil's teeth swinging, gaping like some jungle monster in search of food.

"It's that blasted steel gargoyle of Mull's," he choked, backing towards the cabin stairs. "Get my gun from the table down there!" he roared. "That white livered galoot Andy is messin' with his engines. That gun, curse you!"

ANDY uttered a silent prayer as he swung the river devil with

its shining sabre-edged teeth down to the launch's forerail. The

powerful motor worked with an audible cluck-cluck as the

teeth of the grip mumbled and then fastened on the launch's

foc's'le rail. With his hoisting switch thrown back the chain of

the rock grip became tight as a banjo siring. Then like giant

hook fastened in the jaws of a young whale it raised the launch's

bows from the water.

A terrific commotion followed; plates, crockery, and cabin furniture flew with splintering crashes through the open door, across the stunned and huddled figures of the men in the stern. With the nose of the launch hauled skyward, the stern had become a well, with the cabin furniture spilling through the open door and jamming the occupants close to the deck and stern rail. Andy leaned from the dredge-house and called to the tangle of arms and legs seeking to disentangle themselves from a heavy couch and piano that had burst upon their crouching bodies.

"How d'ye feel, Jacky Daw? It's the bully boy you are with the dishes an' the piano on your chest! Maybe you'll tell me what that boy Clarence was doing in your company? I'm waiting to hear, Jacky Daw."

Only a string of oaths came from the tangle of shapes in the launch's stern. In a little while a voice answered him.

"We found the kid on the beach at Gambat. He'd just missed the steamer that brought mails here. He thought we were miners, so we brought him along, damn him! He went overboard to the iron fish of his own accord."

Well enough Andy knew that the iron fish of New Guinea spared nothing that ventured into the mud-belts after dark. It needed not the glow of his pocket torch to show him the black outlines of the twenty-foot alligators cruising around the dredge.

So much for poor Molly and her wretched boy husband, he told himself, with a sudden twitching of the throat. Fools and blackguards were quickly tested in these crawling death-lands. And Molly could weep, too, for the man that was lying in the deep black mud of Papua.

Andy peered into the sullen darkness of the river, the sweat of his mental torment clinging to his furrowed brow. Then, with only a passing glance at the launch hanging above the slowly moving stream, he shot down into the punt that trailed from the dredge's stern. Andy Mull was no dreamer. It was still possible that Molly's husband might lie drowning under his eyes, somewhere within the foetid tangles of roots and vegetation that lined every foot of the creek-bank.

"Ahoy there, Clarence!" he called out in a choking treble. "Hold on, lad! Look out for the iron fish, an' the ten-foot eels that drowned Jock Sanders last flood."

Not a ripple came to reward his efforts as he thrashed in and out the dripping maze of mangrove roots and flesh-like creepers. A couple of baby alligators snorted under the punt, and their yapping protests were answered by the big-throated mother cruising under the stern of the launch up-stream.

"He's gone, poor fellow." Andy sighed, poling the punt towards the hut near the hank.

"Damned if I know what Molly will say." He tried to whistle as he neared the bank, but his old heart was full of tears and rage at the unlooked-for trouble that had come upon him. The news of this kid's death would wring his daughter's heart. A touch of consolation entered Andy, as he thought of the fix he had put Daw in. If the gang tried to enter the water the wailing alligators would not be disappointed. Andy wiped the moisture from his eye with the sleeve of his torn shirt as he staggered dizzily to the hut. The fire was crackling merrily, sending showers of sparks and flames into the misty night.

ON an upturned bucket close to the fire sat a young man in

steaming clothes and mud-soaked tennis-shoes. At Andy's approach

he turned, holding a steaming silk coat to the fire, a grin of

welcome surprise on his boyish features.

"Quite an Arabian nights entertainment, Mr. Mull." he said genially. "Until a few moments ago the launch was quite comfortable. But it was really Daw's singing that drove me to my fell act.... Barytonitis is a disease with some drunkards." Andy came near to collapse as he stared at the steaming figure on the upturned bucket.

"So you're Clarence!" he gasped, with a swift survey, of the young man's bare chest and reach that would have qualified him for the world's cruiser-weight championship. "And what in blazes brought you here?"

Clarence turned the silk coat once more on the fire, and, feeling satisfied that it was almost dry, drew it on. Then he straightened his spoiled silk lie and lit a damp cigarette with a stick from the fire.

"My dear sir, I came, and I am now sorry," he answered cheerfully. "I wouldn't send a dog here, not if you promised to wash it in your best gold mud."

"But ye came!" Andy roared. The nervous tension of the last few hours pressing on his nerves, "I may tell ye, Clarence Chard, that we don't wash pups in gold baths, nor provide jobs for out-of-works. And be good enough to say something about my little girl that's pushin' an iron in a Chinese laundry down south," he added with growing wrath. Clarence kicked the fire together, and then drawing an empty biscuit box from the hut placed it beside his upturned bucket.

"Please sit down, Mr. Mull. The air of this jungle would spoil a sheep's temper. Don't let it spoil ours!"

Andy sit down mopping his brow, his anger evaporating at the other's sudden change of manner. He began to detect an unknown quality in the young man's bearing.

Across the creek came sounds of Daw's anguish, accompanied by the cries of his two companions, begging to be released from their perilous position.

"Let them hang awhile," Clarence advised, "until my position is explained, Mr. Mull." He smiled and drew a cigar from a silver case.

"Smoke, sir, while I ease your mind. Molly is well. Now," he went on, placing a red ember against the cigar in Andy's mouth, "I'm here on cold business. Smoke up. Those fellows in the launch fooled me into joining them. Of course I didn't know they were hold-ups when I accepted their invitation at Gambat for a free trip to the New Guinea Gold Corporation's works. I wanted to see you. But I spoiled their game the moment we entered the river.

"I'm a journalist. My life is spent running about the city picking up news and stories. I go into prisons and hospitals to hunt up a story. One day I'm at the wharves, among the schooner captains and sailing masters, combing out the story of a wreck or murder on the high seas. It's all in the day's work.

"A few weeks ago, after Molly and I had been quietly married, I visited an old convict at Long Bay penitentiary. His name was Captain Slarfield. Five years ago Slarfield was goldmining and sluicing on this creek. It was named after him. Well, I found him almost delirious—dying, in fact.

"The old chap had been a bit of a buccaneer, and had been mixed up in several shindies hereabouts. He was tried on this river for shooting a couple of natives. He was deported, and his sluicing outfit was confiscated by the police.

"He landed in Sydney, and got into fresh trouble. The penitentiary got him for keeps. He told me he had worked on this creek before while men suspected there was gold on the Joda River. But I found that I had called too late. The poor old chap was raving. He babbled incessantly about a sack of red honey he had found in a tree. Wild honey, of course. He said the bees and the police were always after the honey—especially the bees. So he hid it inside a mahogany tree that used to be hereabouts," Clarence concluded, with a slight yawn. Then, rousing himself on his upturned bucket, he felt for another cigarette.

"Poor Slarfield died next day. And I knew that I had missed the real story of his life."

"And that's what took ye into the gaol."

Andy grinned with another shrewd survey of Chard's handsome face and lengthy limbs.

SILENCE fell between the two, broken only by the frenzied

calls of the three trapped bandits in the launch. A sudden

depression had come over Clarence Chard, a feeling of home-sickness and a thought of the young wife standing in a crowded,

hot workroom, her movements watched and checked by an aggressive,

loud-voiced forewoman.

"And so the bees got into Slarfield's old bonnet," Andy ruminated. "And I'm still waitin' to hear, Clarence, what, sent ye from Molly to this black river of sorrow and death."

The young man straightened his bent shoulders instantly.

"My editor suggested the trip here. He is of opinion that New Guinea is an interesting country to write about. He said it was an unlocked chamber of romance. I'm to get £200 for a series of articles. Molly said the money would help buy a bungalow. And just here, Mr. Mull," Clarence declared, with a sad note in his voice, "I am beginning to feel that those articles and the bungalow are going to flop badly."

"And serve ye right, too," Andy growled, rising slowly from his seat near the fire. "We have three cut-throats hung up by the wing over there," he added almost fiercely. "If I right the launch, or try to, they'll be at us like a pack of wolves. Sit where you are until I come back," he ordered bluntly. Passing inside the hut, Andy took a bright-bladed axe from the fireplace, thumbed the edge critically and with a final glance at the silent figure of Clarence on the upturned bucket, spoke again.

"Ye can't play the Good Samaritan with men who'll reach for you with a razor while you're getting them food and drink," he cautioned. "Freeze your mind and sit still."

Clarence sat very still indeed, watching the dawn steal in orange-hued mists across the distant forest lines. And through the dawn haze he saw the three men clinging tenaciously to the rails and poop of the suspended launch. Immediately below them, in the black, sluggish depths of the creek, the armoured snouts of the manhunters moved briskly to and fro.

Egged on by his companions, Jacky Daw climbed in the launch's forepart in the hope of reaching the crane above, and eventually the dredge. Once his hand touched the lever he could right the launch and allow his friends to join him. Daw's monkey-like body wriggled and squirmed in the ascent. His talon fingers reaching for the chain that linked the rock grip to the forecastle rail. Some grease from the rock-grip streaked over his clutching fingers. A squeal of agony escaped him as he fought with knees and toes and oil-dripping hands to maintain his position.

"Hold on Jacky," a voice quavered from the well of the launch. "These iron fish'll get you by the boots if you tumble down. They never forgive a man his sins, these iron fish."

Daw came down the launch's rail with the scream of a frightened rat. In a moment the alligator shoal bunched together to receive the down-sliding morsel. Miraculously his foot touched a cleat in the deck of the perpendicular launch. His down-rush was stayed.

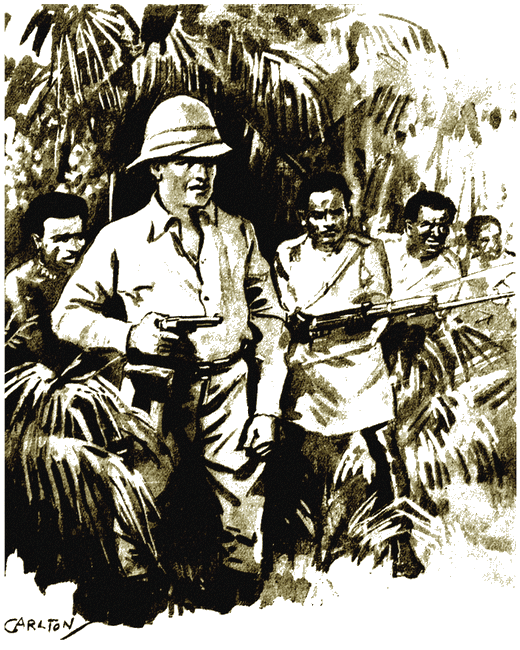

Clarence rose from his seat at the sound of voices higher up-stream. In the grey light he saw a squad of police and native trackers emerge from the beach trail in the south. They approached the dredge with carbines at the ready, the trackers shouting in amaze at sight of the hanging launch and the three outlaws bunched in the well. It was Daw's voice that cracked on the dawn air in response to a short-clipped command from the old sergeant in command of the police.

In the grey light he saw a squad of police and native

trackers emerge from the beach trail in the south.

"Give us a hand out of this, sergeant. I'm sick with the smell of those iron fish below us. Mull played this trick on us," he wailed.

"And a good trick, too," the sergeant laughed, nodding in Clarence's direction. "The dredge and the iron fish manage to keep this creek clean," he added significantly.

Andy appeared from the dark of the mangroves in time to assist in lowering the launch. The vessel righted itself quickly, while the police stood by to cover the exhausted runaways with their carbines. The punt brought them ashore, and after a few words of commendation for the service rendered by Andy the police squad trailed off with their three prisoners in the direction of the settlement.

"WE'LL have breakfast," Andy announced, stirring the fire into

life and thrusting a big coffee kettle on top.

"Lay the table out here, Clarence," he ordered. With a strangely quivering mouth, Clarence obeyed quickly enough, bread and bacon being placed in the pan beside the reddening camp-fire. A pair of tin cups were unearthed as Kini came limping from cover to assist. Andy sipped the hot black coffee that tasted like nectar in the dripping atmosphere of the marsh-sweated jungle lands.

"Try a bit of red honey on your dry bread. Clarence, my son."

Andy drew a sack he had carried in from the bank towards the fire. "It's years since I tasted pure honey. You see," he added, with a gesture towards a shelving bank of the creek. "I found the log poor Slarfield mentioned. It drifted yonder after I freed it from the grip. But the red honey was there, sweet an' fresh as the day he hid it. Try a lump, my son."

Clarence thrust his arm into the sack, strained for a moment at the weighty parcel within, and then with a mighty effort dragged it out. It was bigger than a man's head, and was wrapped in old sail-cloth.

"Gone hard and heavy in the passing years, Mr. Mull," Clarence commented, ripping it open with his knife. A stream of gold dust flowed over the breakfast cloth, over his bread and tin plate that held Andy's nicely browned rasher of bacon.

"Easy, Clarence—easy with the honey," Andy grinned, as he watched the stark amazement in the young man's eyes. Clarence Chard trembled slightly as he fingered the rich, virgin metal which had lain for years where hundreds of starving fossickers and deadbeats had cursed their luck and gone away.

"Poor Slarfield!" he said at last. "Dreaming in his narrow cell of this red metal until his brain got twisted. I suppose Molly will be glad. We'll send some of it along and give her a spell from that electric iron."

Andy's eyes snapped disapproval.

"Send nothing!" he objected. "We'll carry it ourselves and build the bungalow while the strike's on."

He gestured towards the young man's plate. "Brush away that yellow dust from your bacon, my lad, and we'll drink to poor Slarfield's memory in a cup of black coffee."

The sun rose like a big red lantern over the dark Papuan forest in the east. The voice of Kini was heard chanting a hill song as he rolled up old Andy's belongings for the trip south. The purse of yellow dust the white man had thrust into his hand would enable him to buy a valley and a bungalow, "alla same as taubada Clarence an' his good little wife."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.