RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

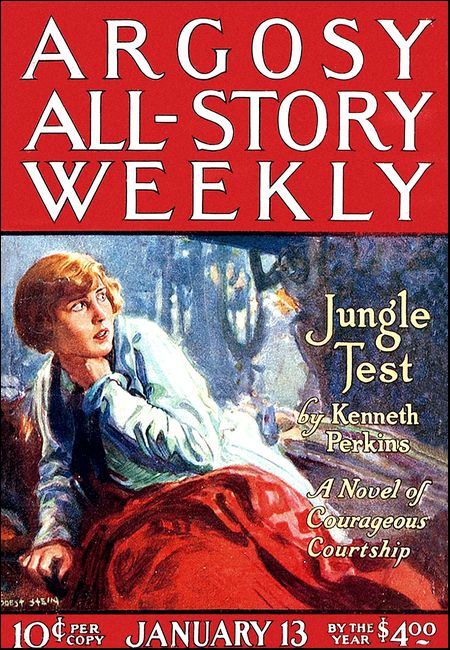

Argosy All-Story Weekly, 13 January 1923, with "The Yellow Flame"

A WHITE queen had never reigned on the island of Vahiti, with its contented armies of plantation workers, recruited mostly from the Solomons and Ellice groups. Yet, Paula Wyngate might have worn a crown of pearls as an emblem of her popularity with the dark and white people who flourish among the fifty trade islands of the little-known Vahiti Archipelago. Socially she ruled within the windswept beach consulates, where French, American and British traders foregathered at certain periods of the year to dance and admire each others' wives, after the custom of men long exiled from civilization.

Her husband, George Vandelour Wyngate, represented an affluent Dutch firm whose headquarters were in Macassar. The foreign consuls with the ugly wives helped Wyngate. They revealed to him the secret hoards of crafty headsmen, the uncounted barrels of shark oil, the new coffee lands, the ungathered stores of vanilla, camphor and sandalwood. Every one threw business in Wyngate's direction because it pleased his wife and kept her in the archipelago, where her society was as badly needed as music at a dance.

The Wyngates lived in a pretty bungalow, sheltered on the ocean side by belts of pandanus and coco palms. In the rear of the bungalow stood a commodious trade house, where George, in his white jeans, met the little schooner captains and canoe-men from the outlying islands.

Paula Wyngate's mail had arrived from Songolo, where her sister Odette was living with the wife of Jimmy Blake, commissioner of customs for the Chinese government.

Swinging in a silk-tasseled hammock on the lagoon side of the bungalow, Paula picked out her sister's letter from a pile of others. Odette was engaged to young Frank Dillon, chief officer of the City of Peking, running between San Francisco, Singapore and Batavia. Young Dillon was a good sailor, but his scanty pay would hardly provide Odette with print dresses, and would hardly allow her to compete socially with the wife of a prosperous headman. Yet, Paula liked Dillon better than any man of her acquaintance; but as the uncrowned queen of Vahiti she had to consider Odette's prestige. She opened the letter with a sudden intuition of trouble. Pretty sisters living from home often developed a flair in the writing of scare correspondence, she told herself.

My dear Paula:

I have done it, and it is hard to say at this distance whether you will congratulate or disown me. The plain truth is I have decided to marry Chiang tu Lee, who has been visiting the Blakes a good deal lately. He is twenty-three and an M. A. of Oxford. I am writing Frank and he will get my letter at San Francisco about the end of the month.

In these latitudes, my dear Paula, women age quickly, and I am going to be a good loser in the race if I wait for Frank. Of course I like him immensely, everybody likes dear old Frank; but to put it coldly, sister mine, I cannot see myself cutting any ice socially as the wife of Dillon. I cannot even attempt a description of Chiang—only a Kipling or a Conrad would have the audacity. Please don't scold me when you write. The weather in Songolo is hot, a hundred and two under the veranda! Pray for your little Odette and give love to George.

Paula Wyngate crushed the letter in her strong white hand. Her

soft cheeks grew suddenly slack and drawn. She sat up in the

hammock as though the dazzling tropic light had blinded her.

Odette was going to marry a Chinaman! She tore the letter in fifty pieces and flung the bits where the southeast trade wind scattered them over the face of the lagoon.

The trade name of Chiang tu Lee was too well known in the archipelago to have escaped her. It was the name that stood at the head of a dozen big Chinese banking institutions; it was the name that owned the new flotilla of steamers plying between Shanghai and Rangoon, half the rice mills in Cambodia and Lombok. Old man Lee, the father of Chiang, had amassed a colossal fortune out of opium and silk, and had died only a year before, leaving Chiang as his sole heir and trustee.

But this fact brought small solace to Paula Wyngate. Odette had been too long with the Blakes. She had lost touch with the outside world. Like scores of other well-meaning young ladies, she had permitted the islands to drug and disturb her sense of social propriety. Marry a Chinaman! Odette had gone mad!

The mere contemplation of such an event caused Paula's head to spin. It would mean the end of her and George. No more dances and bridge parties at the beach consulates: no more highbrow teas with the visiting commodores and captains from the various naval units. If Odette insisted on carrying out her project, nothing but flight would be left for her and George—a midnight stampede to the first westbound steamer or tramp.

Songolo is fifteen hundred miles north-northeast of Vahiti. and steamers called for passengers and cargo every fortnight or thereabouts. Paula felt like crying as she leaned against the veranda rail. She could not tell her husband what Odette had written. It would be like beating an inoffensive collie. She must go to Songolo at once. A steamer was due in about two days.

Passing from the bungalow, she entered the trade house, where George was watching his staff of native boys unpacking some cases of cotton trade and hardware. He looked up quickly as she entered.

"Hello, dear! Mail day and a worried look!" he greeted genially. "Anything wrong?"

"Odette is contracting yellow fever or some other malady, by the tone of her latest. I suppose I'll have to run up and attend to her system."

"Run up to Songolo!" A look of dismay crossed George. "That's going to take a month!" he protested, a momentary vision of himself living alone in the bungalow presenting itself.

"My dear hubby, don't be so selfish. I don't want to go north this weather. Odette has been fooling away her life at the Blakes' since last November. She's got to come home—here," Paula stated firmly.

George sighed as he sat beside her on an upturned biscuit case. "I wanted the kid to come here long ago. Seems to me as if the Blakes want to keep her for good. I'll get the consul to wireless a berth for you on the Tivonia, dear. Remember me to old Blake. Terrible pity he never had any children of his own!"

PAULA arrived at Songolo one hot morning about a week after leaving Vahiti. She had sent no message of her coming to Odette or the Blakes, deeming it advisable to appear on the scene without warning. After her luggage had been safely landed, and instructions given for it to be sent after her, she walked slowly in the direction of Blake's house.

The place was familiar enough; it seemed only a few months since she had brought her sister to the care of the stout, motherly woman who vied with her husband in her admiration for the dashing, high-spirited Odette. The house stood at the end of a long magnolia-skirted avenue, where the white sandstone path gleamed like a silver stream in the tropic sun glare. The heat seemed tempered by the swinging vines of ruby-like petals and oleanders that swarmed in an unforgettable pageant before her. But the tropic splendor of her surroundings had little fascination for the moment. Her active mind was obsessed by the thought of young Mr. Chiang, and wondering, after all, if she had not come too late.

A native maid met her on the veranda—a girl from the Line Islands, named Naura. Her dark eyes widened in surprise when Paula stated that she had just arrived from Vahiti.

"But Missa Blake nor madame not here this week," she informed her visitor breathlessly. "They go on a steamer to Macassar to see the big rajah, Lotang Bu."

"Where is my sister Odette?" Paula inquired sweetly, yet coldly apprehensive of the girl's answer.

Naura cast rapid glances about the house and lawns, and then, unable to control her excitement, ran through a banyan grove calling: "Odette, Odette! Come, please, quick! Oh, come, Missey Odette!"

Paula watched her with a faint smile, yet subtly resenting the fact that the Blakes had left her sister, unchaperoned probably, in a house where boys like Chiang came to play tennis, no doubt.

Glancing down the white road, she saw an automobile slide swiftly toward the place. It carried only one person, a Chinese youth in the early twenties. He was dressed in immaculate white Shantung silk clothes, with tennis shoes and eyeglasses. He pulled up at the veranda and got out. At sight of Paula he hesitated, glancing about him nervously and was about to reenter the car.

"I beg your pardon," Paula began easily. "May I suggest that you are looking for Odette?"

He pivoted slowly, and she had time to note the delicate molding of his ivory-white hands, the clear olive skin that many an Italian beauty might have envied.

His glancing eyes met hers shyly as he bowed and remained uncovered in the broiling sun.

"Yes, I called for Odette," he confessed. "She promised to run out with me to Mount Lavender. The road is a good one for these parts," he added with a soft smile, the one he used, no doubt, when speaking to Odette, Paula imagined.

She nodded at his words, and wondered why artists did not put more Chinese boys and girls into their pictures. She had never seen anything so piquant as this young Celestial. The blood-red orchid he wore in his coat might have come from a pagoda or temple garden. She could not guess how he would look on Broadway or Piccadilly, but he fitted Songolo like a bit of pearl set in a fan.

"It is very good of you to take an interest in my sister," she said at last, and waited.

The quick look of surprise she had expected failed to appear. He merely smiled, and she confessed that his teeth were as white and even as her own.

"Odette told me that her sister is the most beautiful woman in the islands," he stated slowly. "When you spoke I knew you were Mrs. Wyngate."

The inflection of his voice reminded her of a famous contralto's middle-register. It was the kind of voice that could read Keats or Shelley without making people wish that poets had never been born. It sometimes took Paula Wyngate years to like a person. She liked little Chiang at sight, but she had no intention of allowing him to marry Odette.

"Odette, Odette! Where are you, Missey Odette?" Naura called from the banyan grove. "Here is your lovely sisitah come from Vahiti!"

"These natives are passionately human," he expounded, his soft eyes traversing Paula's beautiful features.

"Odette is coming!" Paula exclaimed, stepping into the path to greet her sister.

"Then permit me not to interrupt your meeting," Chiang vouchsafed, getting into the car.

Before Paula could stay him the machine had slid down the road.

"I suppose my letter brought you, dear?" Odette began, her arms encircling Paula affectionately.

"It would have brought me from the South Pole," Paula confessed cheerfully. "I couldn't give a shot like that a miss in balk."

Odette was not as tall as her sister, but the red gold of her hair would have awakened the most hardened critic to a sense of its beauty. Her skin had the peach velvet tone that was the envy of all the island beauties, who often gathered at Mrs. Commissioner Blake's receptions. Odette was the product of an English university. But over-education had not warped the peculiar brilliance of manner typified in the wit and wisdom of her married sister.

"If my letter hurt your feelings, Paula, I'm sorry."

"My feelings, dear, are never in question when your happiness is at stake. I am assuming that it was Mr. Chiang who called here a few moments ago. Let me tell you frankly that I like him. He is a gentleman of the new school of Orientals that is fast ousting the fusty old mandarin type."

"Yes, that was Chi, dear. I promised to go with him to Mount Lavender. He's dreadfully self-conscious and thought, no doubt, that we ought to be left alone."

"And your mind is quite fixed on marrying him?"

"It isn't my mind; it's destiny, dear. I like Frank Dillon, too, but somehow Frank is a man any woman could marry— any woman without a destiny, I mean."

Silence fell between them as Naura brought tea and fruit to the veranda. Paula felt instinctively that the tropics were burning her sister's young blood. She had known women afflicted with orientalism until it made them silly. They raved about Asian creeds and certain forms of Buddhism until they became a nuisance to their friends.

Paula talked of the pleasures of her trip to Songolo, but like a seasoned skirmisher beat back again to the Chiang trail. The business had got to be handled briskly and with finality.

"And speaking of Mr. Chiang, dear, I should like awfully to congratulate you. He is, I feel sure, a gentleman in the best sense, a young man of astonishingly wide culture and taste."

"Some of the whites one meets here," Odette interrupted enthusiastically, "have the manners of coolies. Of course Chi has got to thank Oxford for his English manner."

"His manner does not belong to any university," Paula corrected sweetly; "it is like the sugar in a banana—it belongs to the tree. Mr. Chiang is a high born Celestial; he will never be anything else."

"What do you mean, Paula?"

"Just that, dear. If you lived with him fifty years you'd find yourself talking always to a Chinaman. He would never say 'The top av the mornin' to ye,' as poor Frank says it."

"A bit of blarney isn't everything, Paula," Odette countered. "And look at Frank! He isn't a bit artistic. At the present moment Chi is studying the early life of Leonardo da Vinci, and other early Italian masters. He knows more about rare prints than most dealers. He has translated Schiller into Cantonese! Really, Frank wouldn't understand these things!"

Paula began to feel that her task was no light one. At any moment these two young representatives of the East and West might, without word or sign, plunge into matrimony and defy the world.

In the afternoon Paula visited the principal shopping quarter of the town and completed a few purchases to while away the hours. The following clay, while Odette was arranging with Mrs. Blake's housekeeper, something in the way of a small dinner party in honor of Paula's visit, Mrs. Wyngate slipped out alone and walked in the direction of the quay, near the offices and godowns owned by Chiang tu Lee.

It was a visit of curiosity, and as she walked past the humming rice mills and silk warehouses, she saw how the father of young Chiang had founded a gigantic and thriving industry. Large and small vessels, junks and freighters flew the house flag of Lee & Co., a double dragon on a background of yellow. And all this wealth and commerce was invested in the frail anatomy of one small Celestial with a gold pince-nez!

Passing the main building which housed the clerical staff, she was suddenly overtaken by the swift-running car which had brought Chiang to the Blakes' house the day before. It was driven by a tall Batavian in white and gold livery, which also bore the double dragon on a circle of yellow.

Halting the car, he saluted her respectfully. "The Hon. Mr. Chiang tu Lee presents his compliments to Mrs. Wyngate, and begs her to honor his establishment with her presence."

Paula pondered the invitation for a breath-giving space, and quickly made up her mind. The white and gold livery held open the door of the car allowing her to enter. A hundred yards along the quay front the car halted at the official residence of young Mr. Chiang. Paula had passed the building ten minutes before and it was evident that she had been observed.

The entrance was a study in French decoration and color that was at once soothing and refreshing after the blinding white sandstone roads. Ushered into a conservatory-like foyer, by more of the dragon seal livery, her eyes encountered an exquisite setting of rare orchids and magnolias, with young Mr. Chiang seated in a cane chair beneath.

His greeting was restrained, but held an unmistakable sincerity that was not lost on Paula.

"I hope you like Songolo, Mrs. Wyngate. You will not find it so exciting as Paris, say, but unlike the great European capital it has natural gifts of palms and pearls, silk and fruit of the gods. What more, eh?" he concluded with his boyish smile.

She sat on an ottoman, where a dozen crimson-crested parakeets chattered and swarmed in the palms overhead. There was a delicious fragrance in everything around her, a sense of sybarite cleanliness and order that she had never experienced before.

For a little while they talked easily and without restraint, but in his musical, wayward sentences she began to divine the keynote of his existence:

Odette!

Paula lay back on the ottoman, half beguiled, a little entranced by the soft distillation of this Eastern magic. But the strong white woman in her was not to be denied. She was the ambassadress of her race. She stood for her caste and the prestige of her little island kingdom. She would be definite with this splendid little Chinaman, definite beyond misunderstanding.

"Mr. Chiang," she began calmly, "my sister tells me that you have made her an offer of marriage, which, I gather, she has practically accepted."

Chiang smiled as one in full possession of the sweetest thing in life. "We are going to be very happy, Mrs. Wyngate." he said simply.

"Your happiness would depend a good deal on Odette. She is white, Mr. Chiang!"

He lit a cigarette slowly and then met her glance across the table. "What of that?" he asked gravely. "I am not afflicted with those theories. I stand for humanity. My ideals and beliefs begin and end there. In the abstract there is a difference of what you call race."

"If the difference between East and West was an abstraction, Mr. Chiang, I should have nothing more to say. In this instance Miss West happens to be my sister, and I fear that her marriage with Mr. East is going to spoil her life and mine among the only people we know. Against your good self I have nothing to say. There are white people in these islands unfit to associate with you, and I find it difficult to make my point quite clear."

He sat very still, stiller than anything she had ever seen. Not a muscle or lash of his dark eyes moved. His face had grown rigid.

"Won't you answer, Mr. Chiang?" she almost pleaded.

He rose from his seat painfully and slowly. It was some time before he spoke, and when he did his voice had grown very harsh, like an instrument that had received ill usage.

"If you had asked for my life," he said with difficulty, "I could have given it in your service."

"It means Odette's life," Paula answered wistfully. She paused and met his searching eyes steadily. "And mine, too!"

He had come quite close to her now as one whose breast was bared again for the knife. She knew that she had struck him. Every fiber in his frail body had felt it. But the soul of the East ran like sobbing flames in his young blood.

"Your life, too, Mrs. Wyngate! Am I so horrible?" He half whispered.

"I think you are capable of the noblest sacrifice!"

"If—if you asked it," he stammered, "how could I refuse? I cannot bring this tragedy into your life!" He paused and his breath came like one who had cast himself from a great height. He turned his face from the tropic light after the manner of a child sick with pain.

Paula began to experience her own agony of mind, something of the fierce anguish that was searching his boyish heart. She stood up and placed her hand gently on his shoulder. "I wish I could have kept this out of your life until you were old enough to laugh it away. I, too, know what pain is like!"

He turned to her swiftly, his dark eyes flinching in the cruel white light. "Why should you suffer one breath of pain, because I am foolish enough to dream of a love that cannot be?"

Paula felt herself being caught in the quicksands of his despair. Instinct warned her that she must retreat or surrender. Very slowly she walked to the foyer entrance, the warm perfumes of a hundred islands beating upon her baffled senses. She could not pursue her object further. It was like torturing a child.

He was standing beside her in the hallway, his face a mask of suppressed emotions. "It is very foolish of me, Mrs. Wyngate, to resist your appeal. But—it was so sudden. I could not bring myself to a full realization—" he added brokenly.

"It will come easier after a while," she answered with returning courage. "Odette will understand if it is made clear. There is a way to make her see the difference in your—"

"Nationality," he nodded thoughtfully.

Paula considered the word a moment. It did not seem enough. She would have liked Chiang to prove something more, something that would reveal to Odette the real difference between East and West. He seemed to read the riddle in her mind; a crucified smile lingered on his drawn lips.

"For your sake, Mrs. Wyngate, everything shall be made clear to Odette. There shall be no doubt in her mind concerning the difference between West and East." He paused as though struggling with his madly racing thoughts, while the clamor of the port and the shouting of coolies outside, broke in upon their perfumed isolation. The touch of Paula's hand against his sleeve seemed to wake him to the realities of life.

"Some day, early this week," he half whispered, "bring Odette into the Yamen, where I frequently officiate in a judicial capacity. I think I know what we want."

In the sunlit foyer she turned slowly and held out her hand. He kissed it after the manner of a young courtier.

"Good-by!" he intoned with studied ease. Her eyes searched him swiftly, but she saw no shadow of emotion on his inscrutable face.

PAULA breathed nothing to Odette concerning her chance interview with Chiang. A couple of days slipped by allowing them an opportunity of visiting various places of interest in Songolo. Chiang did not again appear at the house, neither did Odette refer to his absence. Paula was exercised in mind anent his invitation to enter the Yamen, a place used as a courthouse, where Chinese criminals were tried by the official representatives of the Chinese government. Odette informed her that Chiang frequently occupied the judge's chair, as befitted the son of the illustrious banker and island millionaire.

"Only the natives go to the Yamen," Odette was cheerful to add when Paula suggested a visit. "The Blakes never go."

Paula laughed lightly. "I'm dying to see your little Chiang in the role of a judge. Let's have a peep at this Chinese show?"

Odette demurred, but finally consented to accompany her sister to the pagoda-shaped building in the native quarter of the town. It was known in Songolo that the captain of the notorious junk, Kish Loon, was on trial for the murder of a comprador and crew of a Songolo tramp steamer. The captain of the junk, Feng Ho, by name, had proved a curse to small ship owners and schooner craft. He rarely spared his victims once his gang of howling, chattering cutthroats spilled over their rails.

For a long time he had eluded the Chinese water police and gunboats. But Fate, in the guise of a British torpedo destroyer, had shot his smelly junk to pieces, and later brought him to Songolo to be handed over to the authorities. Within an hour after his landing he had managed to escape, but was caught some days afterward, in the hut of a coolie woman who had given him shelter. She also had been arrested.

About the gates of the Yamen was gathered the scum and raffle of the port. The lynx eyes of a Chinese official singled out the two white ladies on the outskirts of the rabble. Without ado he beat his way forward and with many salaams conducted them inside to a seat near the judge's chair.

The place was packed and reeked of sam-shu, vanilla and the sour-skinned natives of the slums. A droning silence filled the Yamen. The judge had not yet arrived. Opposite them was a heavily barred door through which the felons and murderers were sometimes driven like geese. In the center of the Yamen, and surrounded by a curiously wrought metal screen, stood an iron Buddha, ugly, malevolent and leering in the direction of the judge's seat. Above the idol's flat brow was suspended from a metal bracket in the low ceiling an iron glove, the shape and size of a human hand. Paula noticed that the palm of the iron glove was absent.

A sudden stir among the native officials was the signal of the judge's entry. He was dressed in the richly embroidered jacket of a mandarin. The coveted stars and buttons of the third order were visible on his breast. He looked across the Yamen at the sweltering, loose-jawed mob, and then his glancing eyes found Paula and Odette on his right.

The Eastern garb had changed the appearance of Chiang. He was no longer the debonair university student; something of the iron Buddha was reflected in his pose and lineaments. The fragrant delicacy of his movements was gone. He had become part of the Asiatic horde in that malodorous atmosphere of crime and punishment.

Odette gasped in surprise. Her lips moved, but made no sound. Paula's face showed no sign of mental perturbation or excitement. An Oriental in flowing raiment rose and notified the small group of officials gathered around the judge's seat that the proceedings would be conducted in English, and that the sentences would be made known to the prisoners by Mongolian and Cantonese interpreters.

The junkman, Feng Ho, was hustled through the gate and into a cage that was used as a clock for murderers and desperadoes. After him came a coolie woman carrying a baby; she was forced into the cage beside Feng Ho. The pirate was naked to his ragged loin-cloth. From his wrists and ankles trailed heavy prison fetters. He was old and toothless; yet, despite his years, he grinned truculently in the face of the judge and officials.

The proceedings were swift and without formalities. The affidavit of the destroyer's commander was taken and handed to the judge as irrefutable evidence of the fellow's guilt. There was no defense. Evidence was forthcoming which showed that the coolie woman with the baby had harbored and abetted him upon previous occasions when ships belonging to the port had been looted and burned. Her latest offense lay in the fact that she had given him shelter after his escape from the destroyer's crew. The facts were clear and beyond argument.

Sentence of decapitation was passed on the pirate, accompanied by an order that the execution should take place immediately within the grounds of the Yamen. He was seized by his guards and thrust with savage force from the court.

Odette yawned; so swift had been the proceedings that she hardly divined the terrible significance of the judge's order.

The youthful Chiang now fixed his attention on the coolie woman with the baby. Her torn sarong had left her almost bare to the waist. The babe in her arms whimpered fretfully, its flat, brown face and Mongolian eyes expressing an animal sense of misery its mother could not ease.

Chiang appeared to study some papers which a yellow-braided official had placed beside him. He looked at the woman with the curious mask-like indifference which Paula had seen creep into his face before.

"Lalu Gan Deth, you are Feng Ho's accomplice!" he stated in English. "You have helped him in the perpetration of many crimes. I shall deal severely with you according to the law of your country."

A fat Mongolian interpreter standing beside the cage, murmured to the judge that the prisoner was saying that Feng Ho was a near relative, that he had occupied her house on all occasions.

Chiang waived the argument, while a court official demanded instant silence on the part of the fat interpreter. An expectant hush fell upon the Yamen.

Chiang examined his manicured finger nails intently, while Odette leaned nearer her sister. "The dear boy will let her go; he can't help it. He's just pretending he wants to be severe. I know every phase of the silly kid's mind. Listen!"

Chiang's voice carried far into the Yamen; its nasal intonations bespoke the true Celestial. To the expectant Paula it sounded like the fluting of a wolf cub.

"Lalu Gan Deth, your left hand shall be destroyed as befits the associate of murderers and pirates! The penalty will be inflicted in the ordinary way, by means of fire and the iron glove!"

He turned to an official on his right. "Let the sentence be administered without delay," he commanded.

The woman was hauled from the cage and pushed unceremoniously toward the iron Buddha. The crowd in the Yamen rose to its feet, for this form of punishment was the most spectacular and thrilling in the whole Mongolian criminal code.

Paula sat still as death, the loud beating of her heart threatening to stifle her. Odette cowered in her seat as though an unseen hand was gripping her throat. The cold brutality of Chiang's sentence rent the veil of reserve that covered her conventional silence.

The officials had dragged the shrinking Lalu Gan Deth to the screen of the iron Buddha, allowing her to retain the baby in her arms. Her left hand was quickly forced into the iron glove suspended from the bracket above the idol's brow. Then some one touched the leering mouth of Buddha with a lighted stick. A thin jet of yellow flame shot upward toward the iron glove and reached the exposed palm of the coolie woman's hand. A soft cry penetrated the Yamen.

Odette struggled to her feet, anger and abhorrence flashing in her mutinous young eyes. She faced Chiang tu Lee, and her voice grew steady as their glances met. "Mr. Chiang," she said in an audible voice, "I beg you to stop this inhuman torture! It can satisfy no one but yourself even in this house of crime!"

Not for an instant did their glances waver, each looking deep into the soul of the other. Then his soft, dark eyes seemed to become charged with an insatiable cruelty inherited through countless ages. He turned sharply to the ushers standing near.

"Escort this woman from the Yamen!" he said coldly. "And do not allow her to return!"

Odette reeled from his menacing eyes as the ushers led her to the door. Turning suddenly she looked back, her lips parted in scorn and anger that swept her like a mill race.

"You—you Chinaman!" she flung out. "Oh, you Chinaman!"

Paula passed out with her hurriedly in time to escape the loud cries that broke from Lalu Gan Deth, standing at the iron face of Buddha.

LATE that evening, an officer of the Yamen, passing the secretarial apartments occupied by Chiang tu Lee, heard unmistakable sounds of grief emanating from within. Pausing curiously, he peeped inside the room and saw Chiang lying on an ottoman, his face buried in his hands. The sound of his sobbing seemed to fill the apartment. With the discretion of his kind the official withdrew. The private sorrows of the illustrious young judge must not be interrupted.

Two days after the trial of Feng Ho, the Blakes came home. They were genuinely disappointed to learn that Odette was returning to Vahiti with Paula. In his capacity as commissioner of customs, Blake was a traveling gazette of information regarding local affairs. The appointments and resignations of government officials were usually the subject of his criticisms. Speaking to Paula, on the morning of her departure, he said:

"The Chinese Legation is furious over an affair that happened in the Yamen, the other day. The judge, who happens to be a friend of ours, has been asked to resign. They say he sent a coolie woman with a baby to a form of torture known as the iron glove!"

Paula was silent. Neither she nor Odette had mentioned their visit to the Yamen.

"I may tell you, Mrs. Wyngate," Blake went on, "that the silly little chap will never live it down in these islands. He was such a decent sort, and between ourselves, a great admirer of Odette. As proof that something had interfered with his judgment, he sent the coolie woman five thousand dollars, enough to keep her in luxury for the rest of her days. She's out of prison, of course, and seems none the worse for her punishment. I'm really worried about Chiang; such a decent little chap!"

Paula and Odette arrived safely at Vahiti. Odette was not so badly burned as the coolie woman with the baby. She married Frank Dillon when he became captain of the City of Peking, an event brought about by the retirement of his aged superior. It is recorded in the first years of his marriage, that Dillon saved three hundred lives at sea, and never mentions the fact. It is assumed, therefore, that the wayward Odette is in safe keeping.

Two years later, Paula received a letter bearing a Chinese postmark. It was from Chiang. She read it with a strangely beating heart:

Dear Mrs. Wyngate:

True happiness comes only through repression of the senses. I loved Odette with a purity of mind that resembled a fiery flame. My spirit told me that she was mine. It was never possible for you to turn us from our marriage purpose. But to renounce the sweetest pleasure in life was a task almost too great for me. Yet the echoes of your crying heart reached and penetrated me. My chance came through that—woman in the Yamen. I seized it. It was then I made flame eat flame—the fire that scorched the woman's hand burned my image from Odette's heart.

In my present sanctuary of transcendent purity I have found true happiness, perfect content. May the wings of peace descend upon you and your people.

The Shrine of the Seven Stars.

Paula sighed softly as she burned the letter over the yellow

flame of the veranda lamp.

"I wonder if he could have loved Odette as he loves this philosophy of his?" she murmured.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.