RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vitage travel poster

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vitage travel poster

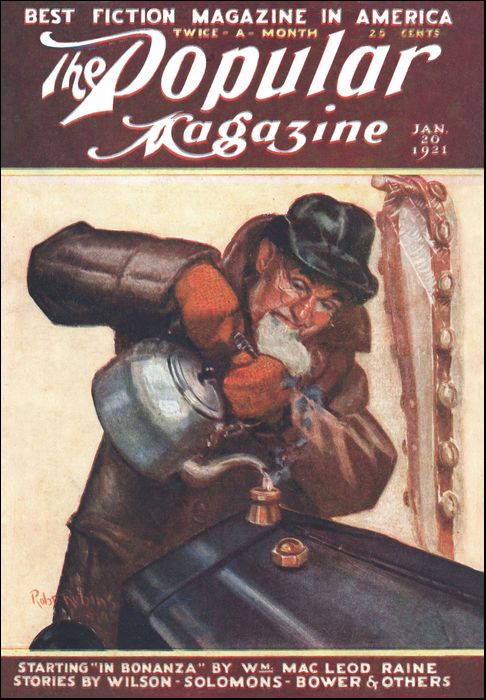

The Popular Magazine, 20 January 1921, with "White Treasure"

It looked like an unsolvable problem that Uncle Zut had set his nephew—until Helen Morrill began to wonder just how much coal would be laid in by a man who knew that he would be dead before the fall.

DURING the last six years he lived, Uncle Zut really amused me. By visiting me for a month or six weeks each year, and by stringent economies the rest of the time, he managed to make a go of it. In spite of the fact that I—and all his acquaintances, in fact—knew just why he came, it was his manner to assume a senile graciousness. One might think after seeing him at my bachelor board that he was conferring a distinctive favor upon me, and that I, instead of himself, was the indigent one.

The young men I chummed with often asked me why I kept the old duffer around, and I told them truly enough that I rather liked him, in spite of his peculiarities. Besides—and this was a point I rarely mentioned—when I had him alone at dinner, I invariably provided him with all the domestic champagne he would drink. Under the genial influence of his fifth or sixth glass from forty to fifty years dropped off Uncle Zut's imagination, if not off his wrinkled physique. He told tales of the south seas, of hunts for pirate treasure, of fights with the head-hunters of Tierra del Fuego, and of various other wild adventures that I later transmuted into the stories that brought me my living. It mattered not at all that I suspected Uncle Zut of being a confirmed, alcoholic liar. His yarns were just as good material, even if he had been no farther south than Louisville, nor farther west than Sioux City.

Only once did he tell any of these stories when another person beside myself was present. That time Rolfe Hinman asked him, winking aside at me, why it was, if he had found all the caches of D'Elfrier the pirate, that he, Uncle Zut, didn't spread himself and get a good car to run around in?

Uncle Zut was not in the least abashed. He had owned a machine, he said, but it got in bad condition. "When I disposed of it," he went on with his bland champagne flourish, "I found to my dismay that I could not get another with the drive on the right-hand side. I knew I was too old to learn to drive another style, so I let it go."

"But some of the English machines are made to order with the drive to suit," pursued Rolfe, enjoying his joke. "Why don't you look up the Rolls-Royce, for instance?"

My aged relative actually beamed at this. "I certainly shall do so!" he answered. "And I am greatly indebted to you, Mr. Hinman, for the tip!" Somehow right then even the patent absurdity of Uncle Zut considering a twelve-thousand-dollar machine did not seem so funny. Rolfe only grinned, and changed the subject himself.

"He's so danged consistent in his lying you almost believe him!" was the way Rolfe put it later. Just for that estimate, which coincided with mine at the time, Rolfe was the first person I invited—but that is ahead of the story.

UNCLE ZUT died in an unusual manner. His physicians pronounced the case acute pernicious beri-beri, a disease which rarely attacks white men—and still more rarely attacks white men who are not sailors by profession. When I heard of it, it gave me an uncanny sort of thrill for an instant, mixed with pity for the old man. In his tales of the rice-eaters of the south seas that dread disease had entered often. Sometimes the victims dried up like mud-worms on the hot sidewalk, sometimes they bloated with dropsy, but always they died. At the end, as if the bacterium had come to him from one of his stories, he had passed on the same way.

I had not heard of his illness in time to speak to him alive, but I attended his funeral—the only one of his relatives to pay him this dismal tribute. On my way back I stopped at the office of the undertaker, intending to pay his bill, but I discovered, to my astonishment, that Uncle Zut had provided for his own burial, even to purchasing a tiny lot in the cemetery and paying the mortician in advance.

"A queer duck," volunteered the young man with whom I spoke. "Nobody thought he'd have a cent, but he came in here one day and picked out the best casket we had in stock—walnut with nickeled clasps, and satin lined. Paid for it and for our auto hearse, with twenty-dollar gold pieces. Said he didn't want any carriages or cars, though, because nobody would come."

YOU may imagine my feelings when, a week later, I received a slim envelope addressed to me in Uncle Zut's familiar, stilted hand. The date at the top of the sheet of note paper was over a year old. The letter read:

Dear Nephew: This note will come to yon after my death. For five years you have been hospitable and kind to a foolish old man. Will you believe when I say that all through the year I have looked forward to the time I spent in your apartment?

All my life I have endeavored to be taken just for myself. As you know, the rest of our family has little use for aged paupers. Only you have been considerate. With them, as at first with you, I preferred to be unwelcome as a penniless old dotard rather than fawned upon because I had money to leave. That I have told you something of my life and adventures as a young man, and allowed you to imagine that I have run through several fortunes, must be attributed to your excellent champagne as much as to the fact that I attained a certain fondness for helping you with your magazine works. You have no notion how I reveled in those tales! They were memories, a little strange, perhaps, because your imagination erred often—and quite often failed completely—but still they were my own memories revivified on the printed page. Particularly that novel of the cannibals of the Horn!

It puzzles me a little why I hang on. Every one of the old devils with whom I sailed is dead ten years now. Parson Grimm was the last. Guess I must have been tough, or perhaps it's because I've been expecting to shuffle off now for nearly two decades. "A watched kettle—;—" you know. Anyway, I can feel the flutter in my pulse now, and that tells its own story. I don't care.

I am too wise a man simply to give you a fortune. You'd never appreciate it. For that reason I am going to make you use that imagination of yours. In my possession right now is the White Treasure of Ullan. All you have to do is find it. Don't bother about Ullan. He is dead.and I don't believe he made a big enough dent in history so his name is remembered. Just hunt in the house for the treasure. If you follow implicitly the directions my lawyer will give you, success must crown your efforts eventually. If your imagination is sharp you may win out in a week. Go to it! In my little cottage you will find many surprises, but the greatest of these will be the treasure, when you find it.

Zut.

THE letter stopped abruptly. My breath, which I had caught in a gasp with the start of the second paragraph, was transmuted into a prolonged whistle. Uncle Zut leaving me a fortune! It was unbelievable! White treasure! What could that be? Silver? In that second the absurdity of my wizened old relative possessing as much as a thousand dollars struck me, and I laughed. Like as not he had written that note while he still was champagne drunk, and imagined himself the possessor of the pirate treasure he imagined he had found.

In going over the letter, line by line, I found subtleties I had not suspected in Zut, however. He had gauged his standing with the family to the fourth decimal place. None of them wanted even a call from the old fellow, for on his first round of the families—the year he appeared from the West—he spent a week with each of the four branches. At that I believe he would have extended this as he did when he came to my apartment, except for the fact that—after his financial condition was discovered—his welcome was none too cordial. Even the Brandons, the soul of hospitality in their own set, balked.

Zut had guessed my main failing as a writer, with uncanny insight. My imagination was faulty, at least for fiction purposes. In order to write even a tale I had to have nearly all the plot and action furnished me by life I observed or yarns which were spun to me. Given all the ingredients, I could mix a palatable dish.

The reason for this lay in my eight years of training as rewrite man on a scientific journal. In that place imagination had been a handicap. Patiently making good, I had schooled myself to doubt every assertion made in an article, to find corroborative evidence for every statement appearing in the script sent finally to the printer, and to steep myself in plain facts.

Zut had picked this out. Also, he had guessed that I lived right up to my rather limited income, and that I paid little attention to what practical business men term the "value of money." What if all that he had told me had been the truth? That thought sent a flood of chill and warmth over my body. A fortune? Wild, impossible that such a thing should happen to me! Yet—

In a voice that trembled a little with excitement reason could not suppress, I called up Helen Morrill.

"I—I am coming right over!" I told her. "I have a—a proposition to make to you!" Always when I talk to Helen my vocabulary grows atrophied and banal.

"But Herv!" she protested. "I'm just eating my breakfast. My hair—"

"Darn your hair—oh, I beg your pardon, Helen! I'm excited as all get-out!"

"I see you are." This was a trifle chillier.

"Oh, hang it, Helen!"T cried, forgetting all the barriers I had kept so carefully between us as safeguards against my own impulses. "It's important!"

"Yes?"

At another time this cool question would have crumpled me into total discomfiture, but now something—maybe the magic of the letter's suggestion—made me throw prudence to the winds.

"Yes!" I said desperately, "I don't know whether you ever guessed, girlie, but I've been head over heels in love with you for two years. I've wanted to ask you to marry me, but I—I just couldn't. Your father showed me bills, bills, bills! I couldn't give those things to you—"

"Hervie!" she cried. "Remember you have a party line, and, besides, I—I don't like to be proposed to that far away! Did you say something about business?"

"No. Yes!" I answered confusedly "Helen, I—"

"Business hours begin for me at eleven," she returned, a hint of mischief behind the formality of her voice. "Suppose you drop in and see me then. After business is over, maybe I could persuade you to have lunch with mother and myself—purely social, you understand?" And though that meant over two hours of waiting, I had to agree.

I SPENT the time in a feverish search through my four encyclopedias, disregarding the letter's statement that Ullan—the pirate, as I supposed, who had garnered the "white treasure" in the first place—would not appear.

No such name was listed, but that did not deter me. I looked up silver, expecting that in the history of this metal I might locate a clew. No hint was there. The subject of piracy was next, but though I accumulated a lot of useless data on the activities of such personages as Morgan and Kidd, I found no Ullan. Zut had known whereof he spoke; the man, if a pirate indeed, had made no dent in history.

Then I tried to imagine of what the treasure might consist. Diamonds or silver, probably, I told myself. These were white, if one was not too finicky in his choice of adjectives. All the while I was downing all the dictates of common sense, which whispered that poor old Uncle Zut simply had been the victim of a drunken delusion. It was the first and only time in my life that even the ghost of a chance for much money had come my way, and I insisted on giving that ghost a full chance to materialize. After I saw Helen I would run right out to Uncle Zut's little dwelling, and commence.

THERE is just one thhig I don't even attempt in writing, and that is to describe Helen. Once or twice I've tried to make her the heroine of one of my stories, but when I get as far as comparing the blue-violet of her eyes to the depths of trout pools in the Sakuache Range, or describing the way her hair glistens in the light like spider-webs of copper—well, I forget all about the story.

She is just the size I like, which is something indefinitely under five feet four—all depending on the height of heels she is wearing. When I'm not fighting with myself to keep from making love to her—and sometimes when I am—her mouth corners twitch just a little, as though she might be just about to smile. When she does smile, though—and here I go, forgetting all about poor old Uncle Zut, just as I said I would.

She was dressed differently that morning than I ever had seen her before—a plaid calico morning dress, and soft-soled slippers. Somehow I felt a little frightened right away. I never had called on a girl in the morning, but I rather supposed that they climbed right into silk frocks after breakfasting in bed—at least, in families like the Morrills, anyway.

"Come right in, Hervie," she greeted me, extending her hand with real cordiality. "I'm not going to make any excuses for my appearance, though. The upstairs maid left us last night, and I have had to help out—"

I saw nothing whatever wrong with her appearance, and said so, I imagine rather fervently.

It was funny, but just as soon as I felt I had something of a right to talk to her of a certain matter my courage oozed right away. Before, when I knew my finances insufficient I had always pictured this moment as one of passionate and eloquent avowal. The truth was—well, different. I began by telling of old Zut.

This was nothing new, up to the point where I spoke of his letter. When Helen leaned over to read this her hair brushed my cheek. Scared? Say, I stammered, stuttered, and finally, when I could talk with some lucidity, I made a consummate ass of myself. "Helen," I said, so pale I could feel it, "if—if this pans out, if there is really a fortune there and I find it, I—I want you to be my wife."

Right now, looking at this sentence, I can see how Chauncey Olcott, or some of those old chaps on the stage might have made it impressive. I didn't. My voice ended up weakly, as if I didn't have the courage of my convictions at all—and really it was only because I did have them so terribly!

I didn't stop there. I told her I loved her. In fact, I think I said that about thirty times before she stopped me.

"Hervie," she said, and I noticed that her eyes didn't waver as she looked at me, "am I to understand that you are proposing marriage to me provided you find this money?"

"Y-yes!" I managed to blurt.

"Then I most certainly and unqualifiedly refuse!" she retorted. Rising to her feet, she bowed once, curtly, and swept out of the room. About two minutes later I came to myself sufficiently to find my hat and seek the door.

THE process of cementing up a broken plate never is interesting. The job is tedious, and also there is the certainty that the plate never will be quite as good as it was before the smash. I shall pass over two days, in which time I moved my own little heaven and earth to find out why Helen had thrown me down with so little regard for my feelings. I could have understood a simple refusal, with the usual corollary of an offer of undying friendship. All of my heroines did that sort of thing on occasion.

Helen had been too definite and too curt, however. I phoned, wrote, and even telegraphed, but she would not see me. Finally in despair I assaulted the house itself.

Emmons, the door man, brought down a calling card with a message on it for me. It said:

For your own sake, I hope you fail. I cannot see you. Helen Morrill.

Now it was not necessary for her to wish for my failure, even if she did not care for me in the least. A trifle resentful I went home, and, as I said, started the dubious job of rearranging myself after the smash.

THURSDAY morning I took the local out to Glen Ellyn, where Zut's little place stood. Nine-tenths of my object in hunting for his white treasure had vanished, but I could not write with even the memory of it on my mind.

I had seen the house once before, at the time of the funeral, but as the funeral had taken place from the isolation hospital, I had not been inside. It was a cottage, once painted white, with green blinds. Now the weather had dirtied and chipped it, until the whole was a smudgy gray. The chimney, extending upward to the peak of the roof, and a foot higher, was dilapidated—sufficient bricks having fallen so that it seemed a miracle that the whole remained upright. Where the shingles had met on the gables now the bare rafters showed through from the street, and I knew that on a rainy day the roof would leak like a sieve.

I tried the front door, but as I expected, it was locked. Zut might have sent me the key, but anyway, he would not care now if I broke a window. Taking up my suit case, I made my way to the side and kicked in the only basement window showing. Tossing the grip down into the blackness, I let myself in and dropped four feet to the dirt floor. By the dim light from that window I made out a rickety stair leading up. This creaked and groaned under my weight, but I managed to make the doorway above without accident.

The room was Zut's kitchen. A small coal range occupied one corner. A pump, and a large basin set in a home-made table stood alongside. One end of the table was covered with oilcloth, and I grinned at the thought of the old codger in here cooking his meals and eating them there beside the stove. A fortune, indeed! I was a bigger fool than I supposed grew wild in the city of Chicago.

Two rooms beside the kitchen occupied the remainder of the ground floor. One of these was fixed up with a single chair—a decrepit morris chair with the back propped up against the corner of the wall—and two bookcases of four sections each. Volumes of all descriptions were piled helter-skelter on the shelves and tops of the cases, while on the floor was a litter of newspapers and periodicals completely covering the ancient grass rug. In the tiny living room outside, were more papers, a table and a corroded brass lamp, beside two straight-backed chairs, one of which lacked a leg.

On a packing box in the corner stood a small talking machine; the space inside the box itself being utilized for records. I reached down and drew out a pair of these. They were both instrumental, one a double-faced record of Chaminade and the other a selection of the more popular airs from "Forza del Destino." I smiled. I could imagine old Zut sitting here alone and playing ballads or popular songs, but scarcely listening to the tenuous melodies of the "Scarf Dance" or the heavy harmonies of "Swear In This Hour." He was a funny one, all right.

As I was just about to ascend the stairs to the half story above, I chanced to glance out through the glass in the front door. A light wagon such as painters use had drawn up at the curb. The driver, a wiry, undersized chap of middle age was attaching a weight to the horse's bit. As he turned to ascend the stoop I saw he wore a black derby hat, trim mustache, and clothes that while evidently not his best still were creased and brushed meticulously. He seemed hurried. I stayed to watch as he nervously fitted a key to the lock and opened the front. door.

His start of surprise was genuine. No doubt it was a real shock to come face to face with a stranger at the door of a house supposed to be empty. I simply waited, leaning on the stair railing.

"Why!" he exclaimed, drawing back. "Who are you?"

"It's my privilege to ask that question first," I parried, for I did not care especially for his looks—and suddenly the presence of the alleged treasure had become very real to me.

"I—I am the landlord!" he stuttered, and then his self-possession returned. "Mr. Zutphen Taylor rented this place from me. You know, I suppose, that he died recently?"

"Yes, I know." The facile gravity of his voice made me distrust him more.

"Well, you see," and he rubbed his hands briskly, "his month was up last Saturday. As I cannot afford to have the place stand long unoccupied, I thought to move his effects to storage until I could get a tenant. At the disposal of his heirs, of course." And he rubbed his hands again.

This sounded like a perfectly reasonable procedure for a landlord, but it was exactly opposed to my plans. In fact, I had taken for granted that Zut owned the little house, though why I should have thought so did not now occur readily to me. Certainly his letter had not stated this to be the fact.

"So you haven't a tenant yet," I observed, adding instantly, "and because of the sickness here I don't suppose anybody will want the place right away."

"No, probably not," he returned. "And it's a pretty high rent, too."

"How much?"

This time there was no doubt about his hesitation. "F-forty dollars a month," he replied, and I saw his eyes shift quickly away and then back to mine.

"Forty!" I cried incredulously. "Uncle Zut paid forty dollars a month for this little place? Impossible!"

He shrugged his shoulders. "That is what I'm holding it for now. I had thought some of moving in myself."

I stepped up close to him. "All right, Mr. Landlord," I said. "I have real reason to want to live here. I'll pay your forty a month. Just send a lease down here and I'll sign it. What is your name?"

He squirmed. "Jonas White," he admitted. "I—I rather think, though, that I would prefer not to rent at all," he went on. "Fact, I'm sure I shall need the place for myself, and—"

His sentence broke off in the middle as I seized his shoulders and marched him to the door.

"If you are really the landlord, Mr. White," I said firmly, "you may either send down a lease to me or have me evicted. If you try the last, though, you are going to get into a lot of trouble. I am the heir of Mr. Zutphen Taylor, and I can make a pretty shrewd guess at the reason why you want possession of this house. I think a court will give me a chance at that lease, if I want to fight—and I certainly do!"

This was mere bluff on my part. I had no least idea whether or not any court would sustain me in my demand for use of the premises while conducting a hunt for my legacy. But it seemed to dismay Jonas White. With a muttered sentence I could not catch he backed down the steps, and drove away. When his rig was out of sight on the road toward the village, I turned and mounted the stairs.

TWO small rooms opened from the box-like hallway at the head of the stairs. One was devoid even of a scrap of furnishing, a forlorn coffin of a place with the ceiling cut off to a height of four feet at one side, and sloping to seven feet at the other. One window, not more than a foot square, showed the ancient wall-paper hanging in tatters, and the floor-boards loose underfoot. Because of my ignorance of beri-beri I had to conquer a real aversion in the investigation, but I was reckless. For two years I had builded much on Helen Morrill. Now she had broken with me so definitely that she could wish me to fail! Gritting my teeth I drew my small hatchet from my pocket. I'd show her! If there was any treasure hidden in this tumble-down shack I would find it.

Reaching up I could touch every foot of the ceiling and walls with the hatchet. It was my plan simply to search every possible place for a hidden cupboard or loose panel. In my stories I always had used such devices when it came to hiding treasure of any description.

Patiently I tapped the ceiling, consuming over an hour in the process. Beside getting many fragments of old plaster in my hair and eyes, I accomplished nothing. When I started on the wall my arms ached as if with neuritis, but I went on. I was getting very weary and famished when it happened. I remember I was just trying to figure out how I could get meals sent up to me, when suddenly the hammer end of my hatchet broke through the flimsy paper!

THRILLED by a wave of excitement, I dropped the hatchet on the floor, and tore away the paper with my fingers. A hole through the plaster, perhaps four inches square was revealed! Into this went my hand—and then my arm, when nothing met my fingers. Way back, a full ten inches, I touched something. It was a small package, tied in paper. Frantically I drew it out, only to have my heart sink clear to my boots when I saw the tiny dimensions. Nothing, unless it be a single large diamond, of that size could be worth much money. I tore off the brown paper wrapping. Into my palm fell a single twenty-dollar gold piece, bright and new, and a slip of folded paper.

I stared at the coin, entranced. This was real, anyway. Unfolding the paper, I forced myself to read. Scribbled in ink—Zut's hand, unmistakably—were these words:

Starting here? Lack of imagination! However, keep at it. Here's a day's wages. Z.

The wry old codger! He had figured out exactly what I would do, and planted this note! In that second my estimation of Uncle Zut rose several thousand per cent. He might have been the victim of delusions, and even a liar, but in that second one would have found difficulty in convincing me. That single double-eagle, lying in my palm, excited me as much as the scrape of Zut's spade on the corner of D'Elfrier's hidden chest had excited my old relative. It was yellow gold.

Day wages indeed! At that Zut had guessed my earning capacity pretty nearly. I thrust my arm once more clear to the back of the aperture, but nothing more was hidden there. My hunger completely driven from mind, I attacked the remainder of the wall in that bare bedroom and in the hall outside with a zest little less than fiery.

A POUNDING at the door knocker downstairs made me stop, with my hatchet held ready for a stroke. As I listened, the knock was repeated, resounding loudly through the empty hall. I tiptoed downstairs. Glancing through the glass—for I was none too anxious for visitors of any kind—I saw an old man, bearded, and dressed in overalls, on the stoop. He could scarcely be an emissary from the landlord, so I unlatched the door.

"Be you Mr. H.E. Taylor?" he asked, looking me over from head to foot with eyes that squinted.

"The same."

"Eh? You say´—" He bent his ear nearer and cupped his hand to assist the sound transmission. "Come last spring I been a leetle hard of hearing."

"I say that I'm Hervie E. Taylor," I replied, somewhat louder. "Is there anything I can do for you?"

The old chap had a kindly face, and I knew his infirmities were not shammed.

"You might," he answered, peering at me again. "Is there anything in your clothes that proves who you be? I got to be sartin sure."

I grinned. Fishing in my hip pocket I brought out a wad of unopened letters—bills that I had not paid. "These letters all are addressed to me," I answered. "Is that enough?"

He brought out his spectacle case, adjusted a pair of silver-rimmed glasses, and held the letters up close.

"I guess you be the man!" he admitted at length. "I've got something for you your Uncle Zutphen left. He didn't put much stock in them lawyer fellows, so I guess this here is a duplicate, signed and everything, of his will. Leastwise he said so, anyway. I was to give it to you." He handed over the long envelope, and turned to hobble away, but I stopped him. Hastily, while he waited, I tore open the envelope, and extracted the two documents within.

The first, to my astonishment, was a guarantee of title to the little house in which I stood. The so-called landlord, Jonas White—if that really had been his name—was a fraud! The confirmation of my suspicions made me grin in satisfaction at the memory of the summary manner in which I had got rid of him.

The second paper was the last will and testament of Zutphen Taylor. I just glanced through it sufficiently to see that I had been named as beneficiary, and that the little house and its contents had been the sum total of his possessions.

"Those are just what I wanted to see!" I exclaimed. "Here, let me give you something for your trouble." I slipped the twenty-dollar gold piece into his hand. He held the coin up close to his eyes and squinted at it.

"Twenty dollars! Glory be!" he ejaculated, in an awed voice. "I can't take that much, sir."

"It's worth it to me," I said. "Oh, and by the way. There is one thing more you can do for me, if you will. How can I get hold of some one who will get my meals for me up here? I'm not much of a hand at cooking, and I don't want to leave."

He grinned genially at me now. "Would you like some ham and aigs, with corn bread and jam, and maybe a bucket of coffee?"

Just then that sounded like the finest banquet in the world to me, and I said so.

"Well," he answered, "that's what the old woman'll get for to-night. If you want some I'll tell her to bring up a load, and then you can fix up with her for other times."

I made my order emphatic, for the mention of food had aroused the appetite I had forgotten. When the old man had gone I took a long drink at Zut's well, and this helped for the time being. To fill in the gap I went back to my hammering. With the ever-present prospect of stumbling across another one of Zut's caches—or the mysterious white treasure—I could forget not only my hunger, but also the vengeful heart-sickness that burned in me whenever I though of Helen Morrill.

I am not a good loser, either at cards or love, though at the latter I have had little experience either at losing or winning. The whole affair seemed like a monstrous nightmare to me, however. I was hurt, angry, and ashamed all at the same time—more because Helen should find herself able to be so contemptuously decided than because of the actual refusal. Had I even suspected the truth fight then, though, old Zut's treasure would have had a long wait, I am afraid.

AT five-thirty I saw the bent figure of an old woman approaching. She carried a covered basket, and I guessed, joyfully, that it must be my dinner. Such proved to be the case, and I hunted up Zut's lone plate and some plated ware from the kitchen. While I was slaughtering more ham and eggs than I ever considered possible for a man to eat at one meal, the old lady told me that she and her husband kept a small grocery in the village. They had known my uncle well, and had performed the same service for him on several occasions. When I had finished, Mrs. Pfeiffer washed up the utensils. I gave her definite instructions to bring me three square meals a day, and when she mentioned her terms I promised just double, on the stipulation that all of the meals should be as good as the one I had finished.

After she left I got cigarettes out of my suit case, and sat down for a half hour of rest that had been well earned. In spite of the aching muscles in my arms and the heavy, soothing fumes of the Yenidje tobacco, I did not sit out the half hour, however. Instantly I thought of scores of places about the little house where a treasure might be secreted. Then my mind whirled to Helen, and this was. even less comfortable. As a compromise, for I did not intend to wield that hatchet any more, I got up and strolled down to the basement. Zut had called my starting at the top of the house an evidence of a lack of imagination. Very well, I should do a little prowling in his cellar. I struck matches, located a single gas jet and lit this, and looked around me.

In the center of the basement, with a pipe leading out to the chimney, was the hot-air furnace—a tiny one as such contraptions go. The rusted air-pipes going upward looked only about half the size of those I had known in my boyhood; but, then, of course, this was a small house.

Behind the furnace stood the coal bins, one nearly empty while the other was filled. I was a little astonished at this sign of Zut's provident nature, as the month was only August; but then I remember how he had paid for his funeral in advance. This was a much more ordinary affair.

The first hint of another surprise came to me when I noticed how small the basement seemed. Somehow it did not take up anywhere near the whole floor plan of the house. Suddenly I saw! The rear end of the basement, behind the coal bins was all boarded up! Fully fifteen feet of the length of the house thus was shut off! The treasure! My heart pounded like a hydraulic pump as I ran for my hatchet. What was it I could expect to find behind that partition?

The second that I attacked if with my weapon, however, I found that force was unnecessary. Part of the wooden wall gave beneath my blows, outlining a door. The catch was concealed at the top, but my trembling fingers found it and slid it open. I pushed the door. Inside was pitch dark. Before venturing forward more than one foot I struck a match. In the instant of that flicker my eyes popped as wide open as nature would allow. Before me, glinting its newness in the polish of its body and nickel trimmings, stood a cream-white Rolls-Royce with a sedan body!

FOR a full minute I imagine I was dumb with amazement. Then I know I yelled—a bloodcurdling cry of surprise and triumph which surely would have roused an entire block in the city. Zut had not been fooling! Here was the surest proof in the world. Like one gone daft I jumped into the driver's seat, seizing the wheel as if I meant to drive straight through the wall of the house. Finding the switch, I snapped on the great headlights.

Then I found his second note. It was attached by a string to the steering column, and read:

Thank Mr. Hinman again for me. The car was a great pleasure to me even if I could run it only after night—to keep the village people from suspecting I owned it. How soon did you find it? I figure now it will take you three days searching before you notice that this wall of the basement is camouflage. I built it in myself, and flatter myself I did a pretty good job. From the outside, too, you'd never know this was used for a garage, except for the tracks in wet weather—and I only drove when it was dry. You are getting warm now, Hervie, but you will never find the treasure until you learn to use your imagination. Observation of details will help, too.

Zut.

I TOSSED the letter in the seat beside me, and laughed. I had beaten his estimated time by two days on this discovery, at any rate! It really tickled my vanity a little. I got up, ran my fingers respectfully over the levers, tried the various buttons, and nearly jumped to the car roof when one of these unexpectedly materialized as a raucous electric horn.

It was some machine! Because I had never owned even a flivver—although I often had meditated just this purchase—I spent a half hour of pure delight, lifting the hood and gazing at the trim, efficient engine, and examining the air-springs and other accessories. Zut had obtained a car with the drive on the right-hand side, and though I had never attempted running a machine with this feature, my fingers itched to take out the car and race it through the night. Caution forbade, however. In the morning I would get busy and finish up my search.

I looked at my watch. It was five minutes of nine. My aching muscles apprised me that this was bedtime. For the sake of a good day's work on the morrow I would have to turn in. A natural aversion to sleeping in the room Zut had occupied, when taken with his last illness, stopped me as I was stepping out of the machine. I got back, and pulling out one of the extension seats, I used this as a rest for my feet. Curled up on the luxurious upholstery of the back, I fell asleep in less than fifteen minutes.

I FOUND out afterward that it was one-thirty when I woke. It was one of these starts that leaves you certain you must have heard something—straining your hearing for another sound, and afraid as the dickens you'll hear it. Doubt did not last long. From the other side of the wooden partition I heard a scraping noise, then a dull thump. This was regular for about a minute, and then came a grunt that might have meant disgust. Some one was out there, all right! 1 got out of the machine as stealthily as possible, and tiptoed to the door.

Coming in I had not bothered to close this tightly, and through an aperture of a half inch I saw a light. It was one of these pocket flashes, lighting up a circle of dirt floor. Beside, it was a shadow that moved. It was a man, digging! For five minutes I held my place, muffling my breathing, and watching him.

He was not large, though I could not make out his features, as most of the time his back was turned. He was searching along the outside wall with his flash light. Every foot or two he: would stop, place the lamp on the ground so its rays spilled over the spot that interested him, and dig with a spade he carried. Just a few seconds seemed to suffice him in each spot. I knew. He was hunting for my treasure!

Mastering the indignation that surged up in me, I waited until he got within ten feet of my hiding place. He might well be armed, so I could afford to take no chances. After what seemed an interminable time, however, I saw that I could reach him before he could level any sort of a weapon at me.

I leaped, throwing the door wide. I struck him at the hips, making a crude football tackle. He sprawled forward, screeching in dismay, with me on top. In that second I seized both his arms, and endeavored to pinion them to his sides. This was not as easy as I had thought, after feeling his light bulk in my grasp. The man was small, but wiry, and fought like a cornered rat. It was not until I had jammed his head into the dirt without mercy that he gave up. Then with my belt I lashed his wrists together behind him, and turned him over for a look at his face.

The second I lifted the flash light I recognized my captive. It was Jonas White!

"So!" I ejaculated. "You're back again, eh?"

He snarled, drawing his lips back over his teeth like a jackal. "Yes!" he gritted. "And I'll have you arrested for this, too! A man can't be safe in his own house these days! I'll make you pay big! I was going to let you have the house, but now I won't! I'll sue you for damages, too!"

"You'll have a chance to tell all that to the judge!" I retorted. "In my pocket is a signed copy of my uncle's will. Also, with it is a deed to this place—a guarantee of title, I mean."

His wicked little eyes popped wide. "A forgery!" he gasped. "Your uncle left no will!"

Right then I saw light. "You were my uncle's lawyer while he lived, Mr. Jonas White!" I said slowly. "He didn't trust you very far, though, because you had some notion that he wasn't as poor as most people thought. He sent the real will and the other papers to me through another source. Now you're going up before the judge and tell him why you were attempting burglary on my place! You know better than I do what that means."

From the ghastly expression that came to his face as I spoke I saw I had hit the mark. He fairly drooled with fear, as soon as he saw I was really in earnest. He pleaded for mercy, and though at first I had no idea of letting him free, the notion occurred that I did not want him telling about the suspected treasure before I actually found it. Finally I decided not to prosecute him. Instead, I drew up a confession that he had been caught in the act of burglary, made him sign it, and then chased him out the front door. I knew his yellow type. Morning would find him just as far from Glen Ellyn as a train could take him.

IT is not my intention to detail all the disappointments that I encountered in the next three days. I started next morning early, with an enthusiasm that I thought boundless. Because of finding the big automobile in the basement, I continued my search there. I dug up every square foot of the dirt floor and sounded the walls, but all without further result. I even crawled under the car and turned up the earth beneath with a hand trowel, but without uncovering Zut's hiding place.

When I came to the coal bins I first searched the one nearly empty. Then I laboriously shoveled all of the soft coal out of the second bin into the first—and it was a hard job, too! I never before had realized that coal was so heavy; the labor, finished, just before Mrs. Pffeifer brought my dinner that evening, left me black from head to foot and tired beyond description. After eating, I went down and examined the floor of the second bin carefully, but nothing showed. Somewhat disgusted, I went up, took a sponge bath at the pump—there was no bath tub in the house—and retired for sleep in the car again.

NEXT morning I made one discovery. I had abandoned the search below stairs, and had tackled the remainder of the second floor. Zut's bedroom yielded nothing, however. It was not until I tackled the library that I found my only other clew. One of the books in the cases—I took every one out and looked at it carefully—proved to be a box bound to resemble a volume.

Therein I discovered a pile of old jewelry. It was not imposing, though many of the set stones were large—they might be rubies, diamonds, and sapphires, though they did not seem to possess the luster. It might have been the old corroded settings, however, for these were so heavy in some cases as almost to surround the gems.

At the bottom of the pile was another of Zut's notes:

Not the White Treasure. Just the personal jewelry of Ferdinand Ullan, sometimes called Ulloa. Keep on! Zut.

I re-examined the rings and brooches. If the stones were real, one of the diamonds would make a magniiceat solitaire. The old setting, of course, was out of the question. I tried the ring on my little finger, but it would not pass the second joint. Old Ullan must have been a little shaver, I decided. Wrapping up the ensemble, with the siagle exception of the solitaire, which I slipped in my vest pocket, I thrust it in my suitcase for future examination. Right then I was after the treasure; the search had become an obsession.

THE rest of that day was fruitless. On the next morning I covered the whole of the remainder of the house. It was with a sinking sensation in the pit of my stomach that I pounded the last time on the walls. I had failed! Old Zut was right. I was not able to imagine any place in the whole house in which I had not looked. There remained only one recourse. I could knock down the walls and take up the floors. Somewhere there might be a safe or a boxed-in partition hidden, that had escaped me.

A sudden thought came to me. The registers! Taking out every one of these I continued the search. When nothing showed, I tied a weight on the end of a stout cord, and plumbed the pipes from the furnace below. All was without result.

I knocked off work, and sat down to think it out. There was little doubt in my mind now that about the house, somewhere, a real treasure was concealed, but so far as I could see I was just as far away from discovering it as ever. It was my lack of imagination without doubt, but just then I felt a little bitter at my uncle for his infernal cleverness. If he knew I would not be able to find his fortune, why had he not given me a chance to work for it, or else said nothing whatever. I had been comparatively happy before. The news in his first letter, though, had ruined my peace of mind forever. Even if I did get the treasure it would be very lame consolation. Helen—

I MOPED around that house the whole remainder of a week. Sometimes I repeated my hammering on parts of the wall I had covered before. Mostly, though, I just smoked and swore, trying to dope out another possibility. The more I endeavored to think on the subject of a hiding place, however, the more I remembered Helen. Why should I worry about money, anyway?

It was Sunday afternoon before I actually did anything more. By that time I was desperate. I would go to see her, tell her that her wish had come true, and find out why she had been so hateful to me. Throwing the suit-case in the big car, I swung back the siding that Zut had fixed for a door out. A moment later I was on the road to Chicago, piloting—rather drunkenly, I am afraid—a machine that nearly ran out from under me every time my foot touched the accelerator.

In the course of the fifteen miles into River Forest, however, I achieved something like familiarity with the splendid mechanism. When I turned in at the drive leading up to the Morrill home I flatter myself I did it rather well. I was so much taken up with bringing the machine to a stop, though, that I did not see Helen until I was mounting the steps. She was lying in a hammock on a corner of the open porch, reading. Even when I approached she continued reading with absorbtion, though she must have noticed the car coming in on the drive. I came right up to her side before she lifted her eyes.

"I see you have succeeded, Mr. Taylor," she said calmly and coldly, then nodding out at the Rolls-Royce.

"No, you have had your wish," I returned, stung by her manner. "I have failed!"

Her eyes widened with astonishment. "Then why—why the car? It's English, isn't it?" I wondered if I could be mistaken. It seemed to me now that she was not nearly so reserved.

"If you'd like to take a ride with me, I'll tell you about it," I answered bluntly.

With one last glance at the magazine she bowed assent. I placed her in the seat beside me in the car, and drove out and away. Scarcely heeding direction, I chose the road north. Not until the last house of the town was behind us did I speak again. Then, slowing to a stop, I related briefly the whole story.

"And now I seem to have lost at every point," I concluded bitterly. "The fortune did not mean anything much to me except as a means for giving you all to which you have been accustomed. Perhaps that is why my—my imagination won't work as it should."

"Hervie," she said, and I was sure now that there was almost a smile on her lips, "that is not a new fault. Before ever you went out to Glen Ellyn you lacked imagination completely!"

I suppose I still have that fault, but I am not totally lacking in common sense. Right then I proposed again, and to my bewilderment and joy was accepted promptly and blushingly.

"We can sell this car and those rings, and later perhaps that little house. That ought to give a capital of fifteen or eighteen thousand. With what I make—" At this point her hand on my mouth interrupted speech.

"Stop right there, you silly boy!" she demanded. "Don't you mention money again! You ought to guess that what I wanted from you was a proposal without any strings to it. I'm not worried—or even interested—about your income. I've got plenty of my own. But to ask a girl if she will marry you if—don't ever do it again, Hervie, dear!"

"I won't!" I promised fervently.

THE white treasure? Yes, I would have forgotten all about it, if it had not been for Helen. The story I told, and the rings of old Ullan I showed her aroused her curiosity, however. Nothing would do but I should drive her right out to the house. On the way she made me review every feature of the search.

"Do you know, Hervie," she asked, pondering, "that it seems very unlike your uncle to put in that much coal this early—particularly if he was rich and did not need to economize?".

"He paid for his funeral in advance," I reminded her.

"When?"

"Oh, along in February or March, I guess."

"Then he really had an idea that he was going to die?"

"Well, perhaps not. At least he did not suspect beri-beri. He knew that he could not last much longer, though. He said so in the first letter I received."

Helen nodded, smiling. "The first thing I'm going to do when I get to that house is look at that coal!" she announced. "It doesn't sound natural to me for an old man to lay in a binful when he is expecting to die any minute!"

And she did. When she took that first shovelful out into the light even I had to admit that there was something peculiar looking about it, for even my remonstrance that we were looking for a white treasure, not a black one, had not stopped Helen.

"Hervie, you vex me sometimes!" she cried. "Even I can see that this isn't coal. Now you know something about geology and chemistry and such things. What is it?"

Thinking hard, I took up a handful of the substance I had thought coal. It was mostly a jet-black powder, but here and there through it occurred lumps of various sizes. These, when the powder had been brushed off, were not totally black, but grayish rather, and heavy—much heavier than any sort of coal, now I had it brought to my notice. Through my brain raced a series of eliminations. It must be some heavy metal—not gold, for gold does not make any ordinary black compounds—not silver, probably In that instant I had it.

"Platinum black! Platinum!" I cried, my heart jumping with the certainty that I was right. "See it is heavy!"

"Platinum?" repeated Helen, wrinkling her forehead incredulously. "That black stuff? Why, I have a pin of platinum, and that is whitish."

"White treasure!" I yelled exuberancy'

"Helen, you've found itl Listen! When you melt platinum with zinc in the proportions of one to two, and then take away the zinc by the action of sulphuric acid, finely divided platinum is left. This is black in color—platinum black they call it in the laboratory. The lumps " I stopped, for I did not know then about the lumps myself.

"Then—then it ought to be a fortune, after all," she ventured.

"Fortune?" I echoed. "I guess yes! Why, there must be eight or nine tons of it there. I know, because I shoveled it myself! Platinum is worth about one hundred dollars an ounce. That means sixteen hundred a pound. There are two thousand pounds to a ton, and say eight tons—"

I stopped. As I have said before, my imagination is faulty.

A METALLURGIST friend of mine corroborated my guess that evening. I took the platinum sample he melted in to a jeweler's shop, and had the large diamond of Ullan set for an engagement ring. The lumps in the bin proved to be alloy—platinum from which the zinc never had been removed. Even with that much base metal, however, the bin was proved to contain a treasure greater than I ever had imagined in my wildest dreams.

A week later, when Helen and I were superintending the removal of the last of it by motor express, old Pfeiffer hobbled up to the house. He had one more letter for me from Zut. My uncle had instructed him to wait until three weeks after I had taken possession of the house before delivering this last message.

The letter explained how my relative had stumbled across an ancient map, in his wanderings. This map, purporting to be dated March 3, 1736, told how a great white treasure had been hidden by Ferdinand Ullan, or Ulloa, who had discovered it in the sands of the river Pinto, near Popayan, Colombia. Searching out this cache, my uncle had recognized the metal as platinum—which its discoverer had thought to be silver, later finding his mistake and not deeming the cache worth seeking out. For the sake of safety in carrying, Uncle Zut had changed the white platinum to platinum black, and thus had brought it into the States.

We kept the big white car, and when Helen and I returned from our honeymoon we took my old friend Rolfe Hinman for a ride. "Old Zut told the truth so well we all thought he was lying!" I told him, winking.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.