RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover

Based on an image created with Microsoft Bing software

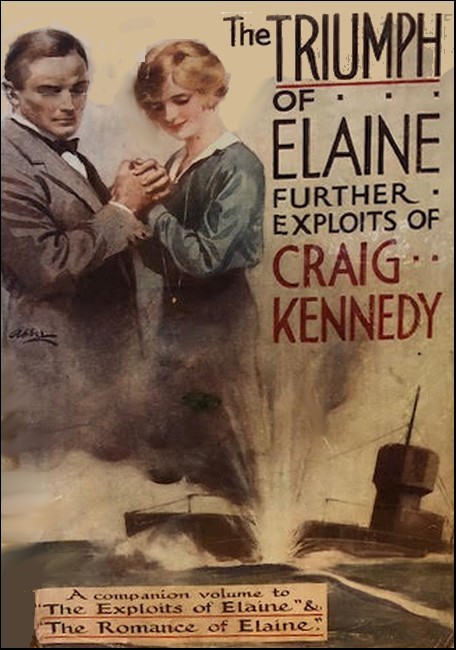

"The Triumph of Elaine,"

Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1916

"The Triumph of Elaine,"

Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1916

As an episodic novel The Triumph of Elaine is something of an oddity. In a brief introduction to the book the publishers, Hodder & Stoughton, give a short description of the first two volumes in the series, then say:

"In this, the third book, Craig Kennedy, who knows the last secret in detective disguises, continues to protect Elaine from terrible dangers by land and by sea—and so helps to achieve her triumph."

What the publishers fail to say is that of the 12 episodes in The Triumph of Elaine all except two ("Chapter X. The Flash" and "Chapter XI. The Disappearing Helmets") had already appeared under the same titles in The Romance of Elaine!

So far as could be ascertained, Hodder & Stoughton were the only publishers to market this volume. No record of an American edition, a British reprint or even an e-book version were found in a exhaustive search of the Internet undertaken with the assistance of Microsoft's AI engine, Copilot.

—Roy Glashan, 16 April 2024

FROM the rocks of a promontory that jutted out not far from the wharf where Wu Fang's body was found and Kennedy had disappeared, opened up a beautiful panorama of a bay on one side and the Sound on the other.

It was a deserted bit of coast. But any one who had been standing near the promontory the next day might have seen a thin line as if the water, sparkling in the sunlight, had been cut by a huge knife. Gradually a thin steel rod seemed to rise from the water itself, still moving ahead, though slowly now as it pushed its way above the surface. After it came a round cylinder of steel, studded with bolts. It was the hatch of a submarine and the rod was the periscope.

As the submarine lay there at rest, the waves almost breaking over it, the hatch slowly opened and a hand appeared groping for a hold. Then appeared a face with a tangle of curly black hair and keen forceful eyes. After it the body of a man rose out of the hatch, a tall, slender, striking person. He reached down into the hold of the boat and drew forth a life-preserver.

"All right," he called down in an accent slightly foreign, as he buckled on the belt. "I shall communicate with you as soon as I have something to report."

Then he deliberately plunged overboard and struck out for the shore. Hand over hand, he churned his way through the water toward the beach until at last his feet touched bottom and he waded out, shaking the water from himself like a huge animal.

The coming of the stranger had not been entirely unheralded. Along the shore road by which Kennedy and I had followed the crooks who we thought had the torpedo, on that last chase, was waiting now a powerful limousine with its motor purring. A chauffeur was sitting at the wheel, and inside, at the door, sat a man peering out along the road to the beach. Suddenly the man in the car signalled to the driver.

"He comes," he cried eagerly. "Drive down the road, closer, and meet him."

The chauffeur shot his car ahead. As the swimmer strode shivering up the roadway, the car approached him. The assistant swung open the door and ran forward with a thick, warm coat and hat. Neither the master nor the servant spoke as they met, but the man wrapped the coat about him, and hurried into the car; then the driver turned and quickly they sped toward the city.

Secret though the entrance of the stranger had been planned, however, it was not unobserved.

Along the beach, on a boulder, gazing thoughtfully out to sea and smoking an old briar pipe, sat a bent fisherman clad in an oilskin coat and hat, and heavy, ungainly boots. About his neck was a long woollen muffler which concealed the lower part of his face quite as effectually as his scraggly, grizzled whiskers.

Suddenly he seemed to discover something that interested him, slowly rose, then turned and almost ran up the shore. Quickly he dropped behind a large rock and waited, peering out.

As the limousine bearing the stranger, on whom the fisherman had kept his eyes riveted, turned and drove away, the old salt rose from behind his rock, gazed after the car as if to fix every line of it in his memory; then he, too, quickly disappeared up the road.

The stranger's car had scarcely gone when the fisherman turned from the shore road into a clump of stunted trees and made his way to a hut. Not far away stood a small, unpretentious closed car, also with a driver.

"I shall be ready in a minute," the fisherman nodded, and ran into the hut, as the driver moved his car up closer to the door.

The larger car was far down the bend of the road when the fisherman reappeared. In an almost incredible time he had changed his oilskins and muffler for a dark coat and silk hat. He was no longer a fisherman, but a rather fussy-looking old gentleman, bewhiskered 'still with eyes looking out keenly from a pair of gold-rimmed glasses.

"Follow that car—at any cost," he ordered simply as he let himself into the little motor, and the driver shot ahead down a bit of side road and out into the main shore road again, urging the car forward to overtake the one ahead.

Such was the entrance of the stranger—Marcius Del Mar—into America.

How I managed to pass the time during the first days after the strange disappearance of Kennedy I don't know. It was all like a dream—the apartment empty, the laboratory empty, my own work on the Star uninteresting. Elaine broken-hearted, life itself a burden.

Hoping against hope the next day I decided to drop around at the Dodge house. As I entered the library unannounced, I saw that Elaine, with a faith which I envied her, was sitting at a table, her back toward the door. She was gazing sadly at a photograph. Though I could not see it, I needed not to be told whose it was She did not hear me come in, so engrossed was she in her thoughts. Nor did she notice me at first as I stood just behind her. Finally I put my hand on her shoulder as if I had been an elder brother. "Have you heard from him yet?" she asked anxiously.

I could only shake my head sadly. She sighed. Involuntarily she rose and together we moved toward the garden, the last place we had seen him about the house.

We had been pacing up and down the garden talking earnestly only a short time when a man made his way in from the Fifth Avenue gate.

"Is this Miss Dodge?" he asked.

"Yes," she replied eagerly.

Neither Elaine nor I knew him at the time, though I think she thought he might be the bearer of some message from Craig. As a matter of fact he was the emissary to whom the stenographer had thrown the torpedo model from the Navy Building in Washington.

His visit was only a part of a deep-laid scheme. Only a few minutes before, three crooks—among them our visitor—had stopped just below the house on a side street. To him the others had given final instructions and a note, and he had gone on, leaving the two standing there.

"I have a note for you," he said, bowing and handing an envelope to Elaine, which she tore open and read.

Washington, D.C.

Miss Elaine Dodge,

Fifth Avenue, New York.

My Dear Miss Dodge,

The bearer, Mr. Bailey, of the Secret Service, would like to question you regarding the disappearance of Mr. Kennedy and the model of his torpedo.

Morgan Bertrand,

U.S. Secret Service.

Even as we were talking the other two crooks had already moved up and had made their way round behind the stone wall that cut off the Dodge garden back of the house. There they stood, whispering eagerly and gazing furtively over the wall as their man talked to Elaine.

After a moment I stepped aside, while Elaine read the note, and, as he asked her a few questions, I could not help feeling that the affair had a very suspicious look. The more I thought of it, the less I liked it. Finally I could stand it no longer.

"I beg your pardon," I excused myself to the alleged Mr. Bailey, "but may I speak to Miss Dodge alone just a minute?"

He bowed, rather ungraciously I thought, and Elaine followed me aside while I told her my fears.

"I don't like the looks of it myself," she agreed. "Yes, I'll be very careful what I say."

While we were talking I could see out of the corner of my eye that the fellow was looking at us askance and frowning. But if I had had an X-ray eye, I might have seen his two companions on the other side of the wall, peering over as they had been before and showing every evidence of annoyance at my interference.

The man resumed his questioning of Elaine regarding the torpedo and she replied guardedly, as in fact she could not do otherwise.

Suddenly we heard shouts on the other side of the wall, as though some one were attacking some one else.

There seemed to be several of them, for a man quickly flung himself over the wall and ran to us.

"They're after us," he shouted to Bailey.

Instantly our visitor drew a gun and followed the newcomer as he ran to get out of the garden in the opposite direction.

Just then a tall, well-dressed, striking man came over the wall, accompanied by another dressed as a policeman, and rushed toward us.

The car bearing the mysterious stranger, Del Mar, kept on until it reached New York, then made its way through the city until it came to the Hotel La Coste.

Del Mar jumped out of the car, his wet clothes covered completely by the long coat. He registered and rode up in the elevator to rooms which had already been engaged for him. In his suite a valet was already unpacking some trunks and laying out clothes when Del Mar and his assistant entered.

With an exclamation of satisfaction at his unostentatious entry into the city, Del Mar threw off his heavy coat. The valet hastened to assist him in removing the clothes still wet and wrinkled from his plunge into the sea.

Scarcely had Del Mar changed his clothes than he received two visitors. Strangely enough they were men dressed in the uniform of policemen.

"First of all we must convince them of our honesty," he said, looking fixedly at the two men. "Orders have been given to the men employed by Wu Fang to be about in half an hour. We must pretend to arrest them on sight. You understand?"

"Yes, sir," they nodded.

"Very well, come on," Del Mar ordered, taking up his hat and preceding them from the room.

Outside the La Coste, Del Mar and his two policemen entered the car which had driven Del Mar from the sea coast and were quickly whisked away, up-town, until they came near the Dodge house.

Del Mar leaped from the car, followed by his two policemen. "There they are, already," he whispered, pointing up the avenue.

All three hastened up the avenue now, where, beside a wall, they could see two men looking through intently as though very angry at something going on inside.

"Arrest them!" shouted Del Mar as his own men ran forward.

The fight was short and sharp, with every evidence of being genuine. One of the men managed to break away and jump the garden wall, with Del Mar and one of the policemen after him, while the other only reached the wall to be dragged down by the other policeman.

Elaine and I had been, as I have said, talking with the man named Bailey who posed as a Secret Service man, when the rumpus began. As the man came over the fence, warning Bailey, it was evident that neither of them had time to escape. With his baton the policeman struck the newcomer of the two flat, while the tall, athletic gentleman leaped upon Bailey and, before we knew it, had him disarmed. In a most clean-cut and professional way he snapped the bracelets on the man.

Elaine was astounded at the kaleidoscopic turn of affairs, too astounded even to make an outcry. As for me, it was all so sudden that I had no chance to take part in it. Besides I should not have known quite on which side to fight. So I did nothing.

But as it was over so quickly, I took a step forward to our latest arrival.

"Beg pardon, old man," I began, "but don't you think this is just a little raw? What's it all about?"

The newest comer eyed me for a moment, then with quiet dignity drew from his pocket and handed me his card, which read simply:

M. Del Mar, Private Investigator.

As I looked up, I saw Del Mar's other policeman bringing in another manacled man.

"These are crooks—foreign agents," replied Del Mar, pointing to the prisoners. "The government has employed me to run them down."

"What of this?" asked Elaine, holding up the note from Bertrand.

"A fake, a forgery," reiterated Del Mar, looking at it a moment critically. Then to the men uniformed as police he ordered, "You can take them to gaol. They're the fellows, all right."

As the prisoners were led off, Del Mar turned to Elaine. "Would you mind answering a few questions about these men?"

"Why—no," she hesitated. "But I think we'd better go into the house, after such a thing as this. It makes me feel nervous."

With Del Mar I followed Elaine in through the conservatory.

Del Mar had scarcely registered at the La Coste when the smaller car which had been waiting at the fisherman's hut drew up before the hotel entrance. From it alighted the fussy old gentleman who bore such a remarkable resemblance to the fisherman, hastily paid his driver and entered the hotel.

He went directly to the desk and with a well-manicured finger, scarcely reminiscent of a fisherman, began tracing the names down the list until he stopped before one which read:

Marcius Del Mar and valet. Washington, D.C. Room 520.

With a quick glance about, he made a note of it, and turned away, leaving the La Coste to take up quarters of his own in the Prince Henry down the street.

Not until Del Mar had left with his two policemen did the fussy old gentleman reappear in the La Coste. Then he rode up to Del Mar's room and rapped at the door.

"Is Mr. Del Mar in?" he inquired of the valet.

"No, sir," replied that functionary.

The little old man appeared to consider, standing a moment dandling his silk hat. Absent-mindedly he dropped it. As the valet stooped to pick it up, the old gentleman exhibited an agility and strength scarcely to be expected of his years. He seized the valet, while with one foot he kicked the door shut.

Before the surprised servant knew what was going on, his assailant had whipped from his pocket a handkerchief in which was concealed a thin tube of anaesthetic. Then leaving the valet prone in a corner with the handkerchief over his face, he proceeded to make a systematic search of the rooms, opening all drawers, trunks and bags.

He turned pretty nearly everything upside down, then started on the desk. Suddenly he paused. There was a paper. He read it, then with an air of extreme elation shoved it into his pocket.

As he was going out he stopped beside the valet, removed the handkerchief from his face and bound him with a cord from the portières. Then, still immaculate in spite of his encounter, he descended in the elevator, re-entered a waiting car and drove off.

Quite evidently, however, he wanted to cover his tracks, for he had not gone a half-dozen blocks before he stopped, paid and tipped the driver generously, and disappeared into the theatre-crowd.

Back again in the Prince Henry, whither the fussy little old man made his way as quickly as he could through a side street, he went quietly up to his room.

His door was now locked. He did not have to deny himself to visitors, for he had none. Still, his room was cluttered by a vast amount of paraphernalia and he was seated before a table deep in work.

First of all he tied a handkerchief over his nose and mouth. Then he took up a cartridge from the table and carefully extracted the bullet. Into the space occupied by the bullet he poured a white powder and added a wad of paper, like a blank cartridge, placing the cartridge in the chamber of a revolver and repeating the operation until he had it fully loaded. It was his own invention of an asphyxiating bullet.

Perhaps half an hour later, the old gentleman, his room cleaned up and his immaculate appearance restored, sauntered forth from the hotel down the street like a veritable Turveydrop, to show himself.

Elaine seemed quite impressed with our new friend, Del Mar, as we made our way to the library, though I am not sure but that it was a pose on her part. At any rate he seemed quite eager to help us.

"What do you suppose has become of Mr. Kennedy?" asked Elaine.

Del Mar looked at her earnestly. "I should be glad to search for him," he returned quickly. "He was the greatest man in our profession. But first I must execute the commission of the Secret Service. We must find his torpedo model before it falls into foreign hands."

We talked for a few moments, then Del Mar with a glance at his watch excused himself. We accompanied him to the door, for he was indeed a charming man. I felt that, if in fact he were assigned to the case, I ought to know him better.

"If you're going down-town," I ventured, "I might accompany you part of the way."

"Delighted," agreed Del Mar.

Elaine gave him her hand and he took it in such a deferential way that one could not help liking him. Elaine was much impressed.

As Del Mar and I walked down the avenue, he kept up a running fire of conversation until at last we came near the La Coste.

"Charmed to have met you, Mr. Jameson," he said, pausing. "We shall see a great deal of each other, I hope."

I had not yet had time to say good-bye myself when a slight exclamation at my side startled me. Turning suddenly, I saw a very brisk, fussy old gentleman who had evidently been hurrying through the crowd. He had slipped on something on the sidewalk and lost his balance, falling near us.

We bent over and assisted him to his feet. As I took hold of his hand, I felt a peculiar pressure from him. He had placed something in my hand. My mind worked quickly. I checked my first impulse to speak and, more from curiosity than anything else, kept the thing he had passed to me surreptitiously.

"Thank you, gentlemen," he puffed, straightening himself out. "One of the infirmities of age. Thank you, thank you."

In a moment he had bustled off quite comically.

Again Del Mar said good-bye and I did not urge him to stay. He had scarcely gone when I looked at the thing the old man had placed in my hand. It was a little folded piece of paper. I opened it slowly. Inside was printed in pencil, disguised:

BE CAREFUL. WATCH HIM.

I read it in amazement. What did it mean?

At the La Coste, Del Mar was met by two of his men in the lobby and they went up to his room.

Imagine their surprise when they opened the door and found the valet lying bound on the floor.

"Who the deuce did this?" demanded Del Mar as they loosened him.

The valet rose weakly to his feet. "A little old man with grey whiskers," he managed to gasp.

Del Mar looked at him in surprise. Instantly his active mind recalled the little old man who had fallen before us on the street.

Who—what was he?

"Come," he said quickly, beckoning his two companions who had come in with him.

Some time later, Del Mar's car stopped just below the Dodge house.

"You men go round to the back of the house and watch," ordered Del Mar.

As they disappeared he turned and went up the Dodge steps.

I walked back after my strange experience with the fussy little old gentleman, feeling more than ever, now that Craig was gone, that both Elaine and Aunt Josephine needed me.

As we sat talking in the library, Rusty, released from the chain on which Jennings kept him, bounded with a rush into the library.

"Good old fellow," encouraged Elaine, patting him.

Just then Jennings entered and a moment later was followed by Del Mar, who bowed as we welcomed him.

"Do you know," he began, "I believe that the lost torpedo model is somewhere in this house, and I have reason to anticipate another attempt of foreign agents to find it. If you'll pardon me, I've taken the liberty of surrounding the place with some men we can trust."

While Del Mar was speaking, Elaine picked up a ribbon from the table and started to tie it about Rusty's neck. As Del Mar proceeded she paused, still holding the ribbon. Rusty, who hated ribbons, saw his chance and quietly sidled out, seeking refuge in the conservatory.

Alone in the conservatory, Rusty quickly forgot about the ribbon and began nosing about the palms. At last he came to the pot in which the torpedo model had been buried in the soft earth by the thief on the night it had been stolen from the fountain.

Quickly Elaine recalled herself and, seeing the ribbon in her hand and Rusty gone, called him. There was no answer, and she excused herself, for it was against the rules for Rusty to wander about.

In his haste the thief had left just a corner of the handkerchief sticking out of the dirt. What none of us had noticed, Rusty's keen eyes and nose discovered and his instinct told him to dig for it. In a moment he uncovered the torpedo and handkerchief and sniffed.

Just then he heard his mistress calling him. Rusty had been whipped for digging in the conservatory, and now, with his tail between his legs, he seized the torpedo in his mouth and bolted for the door of the drawing-room, for he had heard voices in the library. As he did so he dropped the handkerchief, and the little propeller, loosened by his teeth, fell off.

Elaine entered the conservatory, still calling. Rusty was not there. He had reached the stairs, scurrying up to the attic, still holding the torpedo model in his mouth. He pushed open the attic door and ran in. Rusty's last refuge in time of trouble was behind a number of trunks, among which were two of almost the same size and appearance. Behind one of them he had hidden a miscellaneous collection of bones, pieces of biscuit and things dear to his heart. He dropped the torpedo among these treasures.

Del Mar, meanwhile, had followed Elaine through the hall and into the conservatory. As he entered he could see her stooping down to look through the palms for Rusty. She straightened up and went out.

Del Mar followed. Beside the palm pot where Rusty had found the torpedo, he happened to see the old handkerchief soiled with dirt. Near-by lay the little propeller. He picked them up.

"She has found it!" he exclaimed in wonder, following Elaine.

By this time Rusty had responded to Elaine's calls and came tearing downstairs again.

"Naughty Rusty," chided Elaine, tying the ribbon on him.

"So—you have found him at last?" remarked Del Mar, looking quickly at Elaine to see if she would get a double meaning.

"Yes. He's had a fine time running away," she replied.

Del Mar was scarcely able to conceal his suspicion of her. Was she a clever actress, hiding her discovery, he wondered?

Outside, on the lawn, Del Mar's men had been looking about, but had discovered nothing. They paused a moment to speak.

"Look out!" whispered one of them. "There's some one coming."

They dropped down in the shadow. There in the light of the street lamps was the fussy old gentleman coming across the lawn. He stole up to the door of the conservatory and looked through. Del Mar's men crawled a few feet closer. The little old man entered the conservatory and looked about again stealthily. The two men followed him in noiselessly and watched as he bent over the palm pot from which the dog had dug up the torpedo. He looked at the hole curiously. Just then he heard sounds behind him and sprang to his feet.

"Hands up!" ordered one of the men, covering him with a gun.

The little old man threw up his hands, raising his cane still in his right hand. The man with the gun took a step closer. As he did so, the little old man brought down his cane with a quick blow and knocked the gun out of his hand. The second man seized the cane. The old man jerked the cane back and was standing there with a thin, tough steel rapier. It was a sword-cane. Del Mar's man held the sheath.

As the man attacked with the sheath, the little old man parried, sent it flying from his grasp, and wounded him. The wounded man sank down, while the little old man ran off through the palms, followed by the other of Del Mar's men.

Round the hall he ran, and back into the conservatory, where he picked up a heavy chair and threw it through the glass, dropping himself behind a convenient hiding-place near-by. Del Mar's man, close after him, mistaking the crash of glass for the escape of the man he was pursuing, went, on through the broken exit. Then the little old man doubled on his tracks and made for the front of the house.

With Aunt Josephine I had remained in the library.

"What's that?" I exclaimed at the first sounds. "A fight?"

Together we rushed for the conservatory.

The fight, followed so quickly by the crash of glass, also alarmed Elaine and Del Mar in the hallway, and they hurried toward the library, which we had just left by another door.

As they entered, they saw a little old gentleman rushing in from the conservatory and locking the door behind him. He whirled about, and he and Del Mar recognised each other at once. They drew guns together, but the little old man fired first.

His bullet struck the wall behind Del Mar and a cloud of vapour was instantly formed, enveloping Del Mar and even Elaine. Del Mar fell, overcome, while Elaine sank more slowly. The little old man ran forward.

In the conservatory, Aunt Josephine and I heard the shooting, just as one of Del Mar's men ran in again. With him we ran back toward the library.

By this time the whole house was aroused. Jennings and Marie were hurrying downstairs, crying for help and making their way to the library also.

In the library, the little old man bent over Del Mar and Elaine. But it was only a moment later that he heard the whole house aroused. Quickly he shut and locked the folding-doors to the drawing-room, as, with Del Mar's man, I was beating at the rear library door.

"I'll go round," I suggested, hurrying off, while Del Mar's man tried to beat in the door.

Inside the little old man, who had been listening, saw that there was no means of escape. He pulled off his coat and vest and turned them inside out. On the inside he had prepared an exact copy of Jennings' livery.

It was only a matter of seconds before he had completed his change. For a moment he paused and looked at the two prostrate figures before him. Then he took a rose from a vase on the table and placed it in Elaine's hand.

Finally, with his whiskers and wig off, he moved to the rear door, where Del Mar's man was beating, and opened it.

"Look," he cried, pointing in an agitated way at Del Mar and Elaine. "What shall we do?"

Del Mar's man, who had never seen Jennings, ran to his master, and the little old man, in his new disguise, slipped quietly into the hall, out at the front door and into the street, where he had a taxicab waiting for him.

A moment later I burst open the other library door and Aunt Josephine followed me in, just as Jennings himself and Marie entered from the drawing-room.

It was only a moment before we had Del Mar, who was most in need of care, on the sofa; Elaine, already regaining consciousness, lay back in a deep easy-chair.

As Del Mar moved, I turned again to Elaine, who was now nearly recovered.

"How do you feel?" I asked anxiously.

Her throat was parched by the asphyxiating fumes, but she smiled brightly, though weakly.

"Wh-where did I get that?" she managed to gasp finally, catching sight of the rose in her hand. "Did you put it there?"

I shook my head and she gazed at the rose, wondering.

Whoever the little man was, he was gone.

I longed for Craig.

SO confident was Elaine that Kennedy was still alive that she would not admit to herself what to the rest of us seemed obvious.

She even refused to accept Aunt Josephine's hints, and decided to give a masquerade ball, which she had planned as the last event of the season before she closed the Dodge town house and opened her country house on the shore of Connecticut.

It was shortly after the strange appearance of the fussy old gentleman that I dropped in one afternoon to find Elaine addressing invitations, while Aunt Josephine helped her. As we chatted, I picked up one from the pile and mechanically contemplated the address:

M. Del Mar, Hotel La Coste, New York City.

"I don't like that fellow," I remarked, shaking my head dubiously.

"Oh, you're—jealous, Walter," laughed Elaine, taking the envelope away from me and piling it again with the others.

Thus it was that in the morning's mail, Del Mar, along with the rest of us, received a neatly engraved little invitation:

Miss Elaine Dodge

requests the pleasure

of your presence at the

masquerade ball to be

given at her residence

on Friday evening

June 1st.

"Good!" he exclaimed, reaching for the telephone, "I'll go."

In a restaurant in the white-light district two of those who had been engaged in the preliminary plot to steal Kennedy's wireless torpedo model, the young woman stenographer who had betrayed her trust and the man to whom she had passed the model out of the window in Washington, were seated at a table.

So secret had been the relations of all those in the plot that one group did not know the other, and the strangest methods of communication had been adopted.

The man removed a cover from a dish. Underneath, perhaps without even the waiter's knowledge, was a note.

"Here are the orders at last," he whispered to the girl, unfolding and reading the note. "Look. The model of the torpedo is somewhere in her house. Go to-night to the ball as a masquerader and search for it."

"Oh, splendid!" exclaimed the girl. "I'm crazy for a little society after this grind. Pay the cheque and let's get out and choose our costumes."

The man paid the cheque and they left hurriedly. Half an hour later they were at a costumer's shop choosing their disguises, both careful to get the fullest masks that would not excite suspicion.

It was the night of the masquerade.

During the afternoon Elaine had been thinking more than ever of Kennedy. It all seemed unreal to her. More than once she stopped to look at his photograph. Several times she checked herself on the point of tears.

"No," she said to herself, with a sort of grim determination. "No—he is alive. He will come back to me—he will."

And yet she had a feeling of terrific loneliness which even her most powerful efforts could not throw off.

She was determined to go through with the ball, now that she had started it, but she was really glad when it was time to dress, for even that took her mind from her brooding.

As Marie finished helping her put on a very effective and conspicuous costume, Aunt Josephine entered her dressing-room.

"Are you ready, my dear?" she asked, adjusting the mask which she carried so that no one would recognise her as Martha Washington.

"In just a minute, Auntie," answered Elaine, trying hard to put out of her mind how Craig would have liked her dress.

Somewhat earlier, in my own apartment, I had been arraying myself as Boum-Boum and modestly admiring the imitation I made of a circus clown as I did a couple of comedy steps before the mirror.

But I was not really so light-hearted. I could not help thinking of what this night might have been if Kennedy had been alive. Indeed, I was glad to take up my white mask, throw a long coat over my outlandish costume, and hurry off in my waiting car in order to forget everything that reminded me of him in the apartment.

Already a continuous stream of guests was trickling in through the canopy from the curb to the Dodge door, and carriages and motors were arriving and leaving amid great gaping from the crowd on the sidewalk.

As I entered the ballroom it was really a brilliant and picturesque assemblage. Of course I recognised Elaine in spite of her mask, almost immediately.

Characteristically, she was talking to the one most striking figure on the floor, a tall man in red—a veritable Mephistopheles. As the music started, Elaine and his Satanic Majesty laughingly fox-trotted off but were not lost to me in the throng.

I soon found myself talking to a young lady in a spotted domino. She seemed to have a peculiar fascination for me, yet she did not monopolise all my attention. As we trotted past the door, I could see down the hall. Jennings was still admitting late arrivals, and I caught a glimpse of one costumed as a grey friar, his cowl over his head and his eyes masked.

Chatting, we had circled about to the conservatory. A number of couples were there, and, through the palms, I saw Elaine and Mephisto laughingly make their way.

As my spotted domino partner and I swung round again, I happened to catch another glimpse of the grey friar. He was not dancing, but walking, or rather stalking, about the edge of the room, gazing about as if searching for some one.

In the conservatory, Elaine and Mephisto had seated themselves in the breeze of an open window, somewhat in the shadow.

"You are Miss Dodge," he said earnestly.

"You knew me?" she laughed. "And you?"

He raised his mask, disclosing the handsome face and fascinating eyes of Del Mar.

"I hope you don't think I'm here in character," he laughed easily, as she started a bit.

"I—I—well, I didn't think it was you," she blurted out.

"Ah—then there is some one else you care more to dance with?"

"No—no one—no."

"I may hope, then?"

He had moved closer and almost touched her hand. The pointed hood of the grey friar in the palms showed that at last he saw what he sought.

"No—no. Please—excuse me," she murmured, rising and hurrying back to the ballroom.

A subtle smile spread over the grey friar's masked face.

Of course I had known Elaine. Whether she knew me at once I don't know, or whether it was an accident, but she approached me as I paused in the dance a moment with my domino girl.

"From the—sublime—to the ridiculous," she cried excitedly.

My partner gave her a sharp glance. "You will excuse me?" she said, and, as I bowed, almost ran off to the conservatory, leaving Elaine to dance with me.

Del Mar, quite surprised at the sudden flight of Elaine from his side, followed more slowly through the palms.

As he did so he passed a Mexican attired in brilliant native costume. At a sign from Del Mar he paused and received a small package which Del Mar slipped to him, then passed on as though nothing had happened. The keen eyes of the grey friar, however, had caught the little action, and he quietly slipped out after the Mexican bolero.

Just then the domino girl hurried into the conservatory. "What's doing?" she asked eagerly.

"Keep close to me," whispered Del Mar, as she nodded, and they left the conservatory, not apparently together.

Upstairs, away from the gaiety of the ballroom, the bolero made his way until he came to Elaine's room, dimly lighted. With a quick glance about, he entered cautiously, closed the door, and approached a closet which he opened. There was a safe built into the wall.

As he stooped over, the man unwrapped the package Del Mar had handed him and took out a curious little instrument. Inside was a dry battery and a most peculiar instrument, something like a little flat telephone transmitter, yet attached by wires to ear-pieces that fitted over the head after the manner of those of a wireless detector.

He adjusted the head-piece and held the flat instrument against the safe, close to the combination, which he began to turn slowly. It was a burglar's microphone, used for picking combination locks. As the combination turned, a slight sound was made when the proper number came opposite the working point. Imperceptible ordinarily to even the most sensitive ear, to an ear trained it was comparatively easy to recognise the fall of the tumblers over this microphone.

As he worked, the door behind him opened softly and the grey friar entered, closing it and moving noiselessly over to the shelter of a big mahogany tall-boy, round which he could watch.

At last the safe was opened. Rapidly the man went through its contents. "Confound it!" he muttered. "She didn't put it here—anyhow."

The bolero started to close the safe when he heard a noise in the room and looked cautiously behind him. Del Mar himself, followed by the domino girl, entered.

"I've opened it," whispered the emissary, stepping out of the closet and meeting them, "but I can't find the—"

"Hands up—all of you!"

They turned in time to see the grey friar's gun yawning at them. Most politely he lined them up. Still holding his gun ready, he lifted up the mask of the domino girl.

"So—it's you," he grunted.

He was about to lift the mask of the Mexican, when the bolero leaped at him. Del Mar piled in. But sounds downstairs alarmed them, and the emissary, released, fled quickly with the girl. The grey friar, however, kept his hold on Mephistopheles, as if he had been wrestling with a veritable devil.

Down in the hall, I had again met my domino girl a few minutes after I had resigned Elaine to another of her numerous admirers.

"I thought you deserted me," I said, somewhat piqued.

"You deserted me," she parried nervously. "However, I'll forgive you if you'll get me an ice."

I hastened to do so. But no sooner had I gone than Del Mar stalked through the hall and went upstairs. My domino girl was watching for him, and followed.

When I returned with the ice, I looked about, but she was gone. It was scarcely a moment later, however, that I saw her hurry downstairs, accompanied by the Mexican bolero. I stepped forward to speak to her, but she almost ran past me without a word.

"A nut," I remarked under my breath, pushing back my mask.

I started to eat the ice myself, when, a moment later, Elaine passed through the hall with a Spanish cavalier.

"Oh, Walter, here you are," she laughed. "I've been looking everywhere for you. Thank you very much, sire," she bowed with mock civility to the cavalier. "It was only one dance, you know. Please let me talk to Boum-Boum."

The cavalier bowed reluctantly and left us. "What are you doing here alone?" she asked, taking off her own mask. "How warm it is."

Before I could reply, I heard some one coming downstairs behind me, but not in time to turn.

"Elaine's dressing-table," a voice whispered in my ear.

I turned suddenly. It was the grey friar. Before I could even reach out to grasp his robe, he was gone.

"Another nut!" I exclaimed involuntarily.

"Why, what did he say?" asked Elaine.

"Something about your dressing-table."

"My dressing-table?" she repeated.

We ran quickly up the steps. Elaine's room showed every evidence of having been the scene of a struggle, as she went over to the table. There she picked up a rose and under it a piece of paper on which were some words printed with pencil roughly.

"Look," she cried, as I read with her:

Do honest assistants search safes?

Let no one see this but Jameson.

"What does it mean?" I asked.

"My safe!" she cried, moving to a closet. As she opened the door, imagine our surprise at seeing Del Mar lying on the floor, bound and gagged before the open safe. "Get my scissors on the dresser," cried Elaine. I did so, hastily cutting the cords that bound Del Mar.

"What does it all mean?" asked Elaine as he rose and stretched himself.

Still clutching his throat, as if it hurt, Del Mar choked, "I found a man, a foreign agent, searching the safe. But he overcame me and escaped."

"Oh—then that is what the—"

Elaine checked herself. She had been about to hand the note to Del Mar when an idea seemed to come to her. Instead, she crumpled it up and thrust it into her bosom.

On the street the bolero and the domino girl were hurrying away as fast as they could.

Meanwhile, the grey friar had overcome Del Mar, had bound and gagged him, and thrust him into the closet. Then he wrote the note and laid it, with a rose from a vase, on Elaine's dressing-table before he, too, followed.

More than ever I was at a loss to make it out.

It was the day after the masquerade ball that a taxicab drove up to the Dodge house and a very trim but not overdressed young lady was announced as "Miss Bertholdi."

"Miss Dodge?" she inquired as Jennings held open the portières and she entered the library where Elaine and Aunt Josephine were sitting.

If Elaine had only known, it was the domino girl of the night before who handed her a note and sat down, looking about so demurely, while Elaine read:

My Dear Miss Dodge,

The bearer, Miss Bertholdi, is an operative of mine. I would appreciate it if you would employ her in some capacity in your house, as I have reason to believe that certain foreign agents will soon make another attempt to find Kennedy's lost torpedo model.

Sincerely,

M. Del Mar,

Elaine looked up from reading the note. Miss Bertholdi was good to look at, and Elaine liked pretty girls about her.

"Jennings," she ordered, "call Marie."

To the butler and her maid, Elaine gave the most careful instructions regarding Miss Bertholdi. "She can help you finish the packing, first," she concluded.

The girl thanked her and went out with Jennings and Marie, asking Jennings to pay her taxicab driver with money she gave him, which he did, bringing her grip into the house.

Later in the day, Elaine had both Marie and Bertholdi carrying armsful of her dresses from the closets in her room up to the attic where the last of her trunks were being packed. On one of the many trips, Bertholdi came alone into the attic, her arms full as usual. Before her were two trunks, very much alike, open and nearly packed. She laid her armful of clothes on a chair near-by and pulled one of the trunks forward. On the floor lay the trays of both trunks already packed. Bertholdi began packing her burden in one trunk which was marked in big white letters "E. Dodge."

Down in Elaine's room just at that moment Jennings entered. "The expressman for the trunks is here, Miss Elaine," he announced.

"Is he? I wonder whether they are all ready,"

Elaine replied, hurrying out of the room. "Tell him to wait."

In the attic, Bertholdi was still at work, keeping her eyes open to execute the mission on which Del Mar had sent her.

Rusty, forgotten in the excitement by Jennings, had roamed at will through the house, and seemed quite interested. For this was the trunk behind which he had his cache of treasures.

As Bertholdi started to move behind the trunk, Rusty could stand it no longer. He darted ahead of her into his hiding-place. Among the dog biscuit and bones was the torpedo model which he had dug up from the palm pot in the conservatory. He seized it in his mouth and turned to carry it off.

There, in his path, was his enemy, the new girl. Quick as a flash, she saw what it was Rusty had, and grabbed at it.

"Get out!" she ordered, looking at her prize in triumph and turning it over and over in her hands.

At that moment she heard Elaine on the stairs. What should she do? She must hide it. She looked about. There was the tray, packed and lying on the floor near the trunk marked "E. Dodge." She thrust it hastily into the tray, pulling a garment over it.

"Nearly ready?" panted Elaine.

"Yes, Miss Dodge."

"Then please tell the expressman to come up."

Bertholdi hesitated, chagrined. Yet there was nothing to do but obey. She looked at the trunk by the tray to fix it in her mind, then went downstairs.

As she left the room, Elaine lifted the tray into the trunk and tried to close the lid. But the tray was too high. She looked puzzled. On the floor was another tray almost identical.

"The wrong trunk," she smiled to herself, lifting the tray out and putting the other one in, while she placed the first tray, in which the torpedo was concealed, in the other, unmarked, trunk where it belonged. Then she closed the first trunk.

A moment later the expressman entered, with Bertholdi.

"You may take that one," indicated Elaine.

"Miss Dodge, here's something else to go in," said Bertholdi in desperation, picking up a dress.

"Never mind. Put it in the other trunk."

Bertholdi was baffled, but she managed to control herself. She must get word to Del Mar about that trunk marked "E. Dodge."

Late that afternoon, before a cheap restaurant, might have been seen our old friend who had posed as Bailey and as the Mexican. He entered the restaurant and made his way to the first of a row of booths on one side.

"Hello," he nodded to a girl in the booth.

Bertholdi nodded back and he took his seat. She had begged an hour or two off on some pretext.

Outside the restaurant, a heavily-bearded man had been standing looking intently at nothing in particular when Bertholdi entered. As Bailey came along, he followed and took the next booth, his hat pulled over his eyes. In a moment he was listening, his ear close up to the partition.

"Well, what luck?" asked Bailey. "Did you get a clue?"

"I had the torpedo model in my hands," she replied, excitedly telling the story. "It is in a trunk marked 'E. Dodge.'"

All this and more the bearded stranger drank in eagerly.

A moment later Bailey and Bertholdi left the booth and went out of the restaurant followed cautiously by the stranger. On the street the two emissaries of Del Mar stopped a moment to talk.

"All right, I'll telephone him," she said, as they parted in opposite directions.

The stranger took an instant to make up his mind, then followed the girl. She continued down the street until she came to a store with telephone booths. The bearded stranger followed still, into the next booth, but did not call a number. He had his ear to the wall.

He could hear her call Del Mar, and although he could not hear Del Mar's answers, she repeated enough for him to catch the drift. Finally, she came out, and the stranger, instead of following her farther, took the other direction hurriedly.

Del Mar himself received the news with keen excitement. Quickly he gave instructions and prepared to leave his rooms.

A short time later his car pulled up before the La Coste, and, in a long duster and cap, Del Mar jumped in, and was off.

Scarcely had his car swung up the avenue when, from an alleyway down the street from the hotel, the chug-chug of a motor-cycle sounded. A bearded man, his face further hidden by a pair of goggles, ran out with his machine, climbed on and followed.

On out into the country Del Mar's car sped. At every turn the motor-cycle dropped back a bit, observed the turn, then crept up and took it too. So they went for some time.

On the level of the Grand Central where the trains left for the Connecticut shore where Elaine's summer home was situated, Bailey was now edging his way through the late crowd down the platform. He paused before the baggage-car just as one of the baggage motor trucks rolled up loaded high with trunks and bags. He stepped back as the men loaded the luggage on the car, watching carefully.

As they tossed on one trunk marked "E. Dodge," he turned with a subtle look and walked away. Finally he squirmed around to the other platform. No one was looking and he mounted the rear of the baggage-car and opened the door. There was the baggage-man sitting by the side door, his back to Bailey. Bailey closed the door softly and squeezed behind a pile of trunks and bags.

Finally Del Mar reached a spot on the railroad where there were both a curve and a grade ahead. He stopped his car and got out.

Down the road the bearded and goggled motorcyclist stopped just in time to avoid observation. To make sure, he drew a pocket field-glass and levelled it.

"Wait here," ordered Del Mar. "I'll call when I want you."

Back on the road the bearded cyclist could see Del Mar move down the track though he could not hear the directions. It was not necessary, however. He dragged his machine into the bushes, hid it and hurried down the road on foot.

Del Mar's chauffeur was waiting idly at the wheel when suddenly the cold nose of a revolver was stuck under his chin.

"Not a word—and hands up—or I'll let the moonlight through you," growled out a harsh voice.

Nevertheless, the chauffeur managed to lurch out of the car, and the bearded stranger, whose revolver it was, found that he would have to shoot. Del Mar was not far enough away to risk it.

The chauffeur flung himself on him and they struggled fiercely, rolling over and over in the dust of the road.

But the bearded stranger had a grip of steel and managed to get his fingers about the chauffeur's throat as an added insurance against a cry for help.

He choked him literally into insensibility. Then, with a strength that he did not seem to possess, he picked up the limp, blue-faced body and carried it off the road and round the car.

In the baggage-car, the baggage-man was smoking a surreptitious pipe of powerful tobacco between stations and contemplating the scenery thoughtfully through the open door.

As the engine slowed up to take a curve and a grade, Bailey, who had now and then taken a peep out of a little grated window above him, crept out from his hiding-place. Already he had slipped a dark silk mask over his face.

As he made his way among the trunks and boxes, the train lurched and the baggage-man, who had his back to Bailey, heard him catch himself. He turned and leaped to his feet. Bailey closed with him instantly.

Over and over they rolled. Bailey had already drawn his revolver before he left his hiding-place. A shot, however, would have been fatal to his part in the plans, and was only a last resort, for it would have brought the trainmen.

Finally Bailey rolled his man over, and, getting his right arm free, dealt the baggage-man a fierce blow with the butt of the gun.

The train was now pulling slowly up the grade. More time had been spent in overcoming the baggage-man than he expected and Bailey had to work quickly. He dragged the trunk marked "E. Dodge" from the pile to the door and glanced out.

Just around the curve in the railroad Del Mar was waiting, straining his eyes down the track.

There was the train, puffing up the grade. As it approached he rose and waved his arms. It was the signal and he waited anxiously. Had his plans been carried out?

The train passed. From the baggage-car came a trunk catapulted out by a strong arm. It hurtled through the air and landed with, its own and the train's momentum.

Over it rolled in the bushes, then stopped—unbroken, for Elaine had had it designed to resist even the most violent baggage-smasher.

Del Mar ran to it. As the tail light of the train disappeared he turned round in the direction from which he had come, placed his two hands to his mouth and shouted.

From the side of the road by Del Mar's car the bearded motor-cyclist had just emerged, buttoning the chauffeur's clothes and adjusting his goggles to his own face.

As he approached the car, he heard a shout. Quickly he tore off the black beard which had been his disguise and tossed it into the grass. Then he drew the coat high up about his neck.

"All right!" he shouted back, starting along the road.

Together he and Del Mar managed to scramble up the embankment to the road, and, one at each handle of the trunk, they carried it back to the car, and piled it in.

The improvised chauffeur started to take his place at the wheel, and Del Mar had his foot on the running-board to get beside him, when the now unbearded stranger suddenly swung about and struck Del Mar full in the face. It sent him reeling back into the dust.

The engine of the car had been running, and before Del Mar could recover consciousness, the stranger had shot the car ahead, leaving Del Mar prone in the roadway.

The train, with Bailey on it, had not gained much speed, yet it was a perilous undertaking to leap. Still, it was more so now to remain. The baggage-man stirred. It was now a case of murder or a quick getaway. There was no time for any middle course.

Bailey jumped.

Scratched and bruised and shaken, he scrambled to his feet in the briars along the track. He staggered up to the road, pulled himself together, then hurried back as fast as his barked shins would let him.

He came to the spot which he recognised as that where he had thrown off the trunk. He saw the trampled and broken bushes, and made for the road.

He had not gone far when he saw, far down, Del Mar suddenly attacked and thrown down, apparently by his own chauffeur. Bailey ran forward, but it was too late. The car was gone.

As he came up, Del Mar, lying outstretched in the road, was just recovering consciousness.

"What was the matter?" he asked. "Was he a traitor?"

He caught sight of the real chauffeur on the ground, stripped.

Del Mar was furious. "No," he swore, "it was that confounded grey friar again, I think. And he has the trunk, too!"

Speeding up the road the former masquerader and motor-cyclist stopped at last.

Eagerly he leaped out of Del Mar's car and dragged the trunk over the side regardless of the enamel.

It was the work of only a moment for him to break the lock with a pocket jimmy.

One after another he pulled out and shook the clothes until frocks and gowns and lingerie lay strewn all about.

But there was not a thing in the trunk that even remotely resembled the torpedo model.

The stranger scowled.

Where was it?

DEL MAR had evidently, by this time, come to the conclusion that Elaine was the storm centre of the peculiar train of events that followed the disappearance of Kennedy and his wireless torpedo.

At any rate, as soon as he learned that Elaine was going to her country home for the summer, he took a bungalow some distance from Dodge Hall. In fact, it was more than a bungalow, for it was a pretentious place surrounded by a wide lawn and beautiful, shady trees.

There, on the day that Elaine decided to motor in from the city, Del Mar arrived with his valet.

Evidently he lost no time in getting to work on his own affairs, whatever they might be. Inside his study, which was the largest room in the house, a combination of both library and laboratory, he gave an order or two to his valet, then immediately sat down to his new desk. He opened a drawer and took out a long hollow cylinder, closed at each end by air-tight caps, on one of which was a hook.

Quickly he wrote a note and read it over: "Install submarine bell in place of these clumsy tubes. Am having harbour and bridges mined as per instructions from Government.—D."

He unscrewed the cap at one end of the tube, inserted the note, and closed it. Then he pushed a button on his desk. A panel in the wall opened, and one of the men who had played policeman once for him stepped out and saluted.

"Here's a message to send below," said Del Mar briefly.

The man bowed and went back through the panel, closing it.

Del Mar cleaned up his desk and then went out to look his new quarters over, to see whether everything had been prepared according to his instructions.

From the concealed entrance to a cave on a hillside, Del Mar's man who had gone through the panel in the bungalow appeared a few minutes later and hurried down to the shore. It was a rocky coast with stretches of cliffs and now and then a ravine and bit of sandy beach. Gingerly he climbed down the rocks to the water.

He took from his pocket the metal tube which Del Mar had given him and to the hook on one end attached a weight of lead. A moment he looked about cautiously. Then he threw the tube into the water, and it sank quickly. He did not wait, but hurried back into the cave entrance.

Elaine, Aunt Josephine, and I motored down to Dodge Hall from the city. Elaine's country house was on a fine estate near the Long Island Sound, and after the long run we were glad to pull up before the big house and get out of the car. As we approached the door, I happened to look down the road.

"Well, that's the country, all right," I exclaimed, pointing down the road. "Look."

Lumbering along was a huge heavy hay rack on top of which perched a farmer chewing a straw. Following along after him was a dog of a peculiar shepherd breed which I did not recognise. Atop of the hay the old fellow had piled a trunk and a basket.

To our surprise, the hay rack stopped before the house. "Miss Dodge?" drawled the farmer nasally.

"Why, what do you suppose he can want?" asked Elaine, moving out toward the wagon, while we followed.

"Yes?"

"Here's a trunk, Miss Dodge, with your name on it," he went on, dragging it down. "I found it down by the railroad track."

It was the trunk marked "E. Dodge" which had been thrown off the train, taken by Del Mar, and rifled by the motor-cyclist.

"How do you suppose it ever got here?" cried Elaine in wonder.

"Must have fallen off the train," I suggested. "You might have collected the insurance under this new baggage law!"

"Jennings," called Elaine. "Get Patrick and carry the trunk in." Together the butler and the gardener dragged it off.

"Thank you," said Elaine, endeavouring to pay the farmer.

"No, no, Miss," he demurred, as he clucked to his horses.

We waved to the old fellow. As he started to drive away, he reached down into the basket and drew out some yellow harvest apples. One at a time he tossed them to us as he lumbered off.

"Truly rural," remarked a voice behind us.

It was Del Mar, all togged up and carrying a magazine in his hand.

We chatted a moment, then Elaine started to go into the house with Aunt Josephine. With Del Mar I followed.

As she went Elaine took a bite of the apple. To her surprise it separated neatly into two hollow halves. She looked inside. There was a note. Carefully she unfolded it and read. Like the others, it was not written but printed in pencil:

Be careful to unpack all your trunks yourself. Destroy this note.—

A Friend.

What did these mysterious warnings mean, she asked herself in amazement. Somehow so far they had worked out all right. She tore up the note and threw the pieces away.

Del Mar and I stopped for a moment to talk. I did not notice that he was not listening to me but surreptitiously watching Elaine.

Elaine went into the house, and we followed. Del Mar, however, dropped just a bit behind and, as he came to the place where Elaine had thrown the pieces of paper, dropped his magazine. He stooped to pick it up and gathered the pieces, then rejoined us.

"I hope you'll excuse me," said Elaine brightly. "We've just arrived, and I haven't a thing unpacked."

Del Mar bowed, and Elaine left us. Aunt Josephine followed shortly. Del Mar and I sat down at a table. As he talked he placed the magazine in his lap beneath the table, on his knees. I could not see, but he was in reality secretly putting together the torn note which the farmer had thrown to Elaine.

Finally he managed to fit all the pieces. A glance down was enough. But his face betrayed nothing. Still under the table, he swept the pieces into his pocket and rose.

"I'll drop in when you are more settled," he excused himself, strolling leisurely out again.

Up in the bedroom Elaine's maid, Marie, had been unpacking.

"Well, what do you know about that?" she exclaimed as Jennings and Patrick came dragging in the banged-up trunk.

"Very queer," remarked Jennings, detailing the little he had seen, while Patrick left.

The entrance of Elaine put an end to the interesting gossip, and Marie started to open the trunk.

"No, Marie," said Elaine. "I'll unpack them myself. You can put the things away later. You and Jennings may go."

Quickly she took the things out of the battered trunk. Then she started on the other trunk, which was like it but not marked. She threw out a couple of garments, then paused, startled.

There was the lost torpedo—where Bertholdi had stuck it in her haste! Elaine picked it up and looked at it in wonder as it recalled all those last days before Kennedy was lost. For the moment she did not know quite what to make of it. What should she do?

Finally she decided to lock it up in the bureau drawer and tell me. Not only did she lock the drawer but, as she left her room, she took the key of the door from the lock inside and locked it outside.

Del Mar did not go far from the house, however. He scarcely reached the edge of the grounds, where he was sure he was not observed, when he placed his fingers to his lips and whistled. An instant later two of his men appeared from behind a hedge.

"You must get into her room!" he ordered. "That torpedo is in her luggage somewhere, after all."

They bowed and disappeared again into the shrubbery, while Del Mar turned and retraced his steps to the house.

In the rear of the house the two emissaries of Del Mar stole out of the shelter of some bushes and stood for a moment looking. Elaine's windows were high above them, too high to reach. There seemed to be no way to get to them, and there was no ladder in sight.

"We'll have to use the Dutch house-man's method," decided one.

Together they went around the house toward the laundry. It was only a few minutes later that they returned. No one was about. Quickly one of them took off his coat. Around his waist he had wound a coil of rope. Deftly he began to climb a tree whose upper branches fell over the roof. Cat-like he made his way out along a branch and managed to reach the roof. He proceeded along the ridge pole to a chimney which was directly behind and in line with Elaine's windows. Then he uncoiled the rope and made one end fast to the chimney. Letting the other end fall free down the roof, he carefully lowered himself over the edge. Thus it was not difficult to get into Elaine's room by stepping on the window-sill and going through the open window.

The man began a rapid search of the room, turning up and pawing everything that Elaine had unpacked. Then he began on the little writing-desk, the dresser, and the bureau drawers. A subtle smile flashed over his face as he came to one drawer that was locked. He pulled a sectional jimmy from his coat and forced it open.

There lay the precious torpedo.

The man clutched at it with a look of exultation. Without another glance at the room he rushed to the window, seized the rope, and pulled himself to the roof, going as he had come.

It did not take me long to unpack the few things I had brought, and I was soon back again in the living-room, where Aunt Josephine joined me in a few minutes.

Just as Elaine came hurriedly down the stairway and started toward me, Del Mar entered from the porch. She stopped. Del Mar watched her closely. Had she found anything? He was sure of it.

Her hesitation was only for a moment, however. "Walter," she said, "may I speak to you a moment? Excuse us, please?"

Aunt Josephine went out toward the back of the house to see how the servants were getting on, while I followed Elaine upstairs. Del Mar with a bow seated himself and opened his magazine. No sooner had we gone, however, than he laid it down and cautiously followed us.

Elaine was evidently very much excited as she entered her dainty little room and closed the door. "Walter," she cried, "I've found the torpedo!"

We looked about at the general disorder. "Why," she exclaimed nervously, "some one has been here—and I locked the door, too."

She almost ran over to her bureau drawer. It had been jimmied open in the few minutes while she was downstairs. The torpedo was gone. We looked at each other, aghast.

Behind us, however, we did not see the keen and watchful eyes of Del Mar, opening the door and peering in. As he saw us, he closed the door softly, went downstairs and out of the house.

About half a mile down the road, the farmer abandoned his hay rack, and now, followed by his peculiar dog, walked back. He stopped at a point in the road where he could see the Dodge house in the distance, sat on the rail fence and lighted a blackened corn-cob pipe.

There he sat for some time apparently engrossed in his own thoughts about the weather, the dog lying at his feet. Now and then he looked fixedly toward Dodge Hall.

Suddenly his vagrant attention seemed to be riveted on the house. He drew a field-glass from his pocket and levelled it. Sure enough, there was a man coming out of a window, pulling himself up to the roof by a rope and going across the roof tree. He lowered the glasses quickly and climbed off the fence with a hitherto unwonted energy.

"Come, Searchlight," he called to the dog, as together they moved off quickly in the direction he had been looking.

Del Mar's men were coming through the hedge that surrounded the Dodge estate just as the farmer and his dog stepped out in front of them from behind a thicket.

"Just a minute," he called. "I want to speak to you."

He enforced his words with a vicious-looking gun. It was two to one, and they closed with him. Before he could shoot, they had knocked the gun out of his hand. Then they tried to break away and run.

But the farmer seized one of them and held him. Meanwhile the dog developed traits all his own. He ran in and out between the legs of the other man until he threw him. There he stood, over him. The man attempted to rise. Again the dog threw him and kept him down. He was a trained Belgian sheep hound, a splendid police dog.

"Confound the brute," growled the man, reaching for his gun.

As he drew it, the dog seized his wrist, and with a cry the man dropped the gun. That, too, was part of the dog's training.

While the farmer and the other man struggled on the ground, the torpedo worked its way half from the man's pocket. The farmer seized it. The man fell back, limp, and the farmer, with the torpedo in one hand, grasped at the gun on the ground and straightened up.

He had no sooner risen than the man was at him \ again. His unconsciousness had been merely feigned. The struggle was renewed.

At that point, the hedge down the road parted and Del Mar stepped out. A glance was enough to tell him what was going on. He drew his gun and ran swiftly toward the combatants.

As Del Mar approached, his man succeeded in knocking the torpedo from the farmer's hand. There it lay, several feet away. There seemed to be no chance for either man to get it.

Quickly the farmer bent his wrist, aiming the gun deliberately at the precious torpedo. As fast as he could he pulled the trigger. Five of the six shots penetrated the little model.

So surprised was his antagonist that the farmer was able to knock him out with the butt of his gun. He broke away and fled, whistling on a police whistle for the dog just as Del Mar ran up. A couple of shots from Del Mar flew wide as the farmer and his dog disappeared.

Del Mar stopped and picked up the model. It had been shot into an unrecognisable mass of scrap. In a fury, Del Mar dashed it on the ground, cursing his men as he did so.

The strange disappearance of the torpedo model from Elaine's room worried both of us. Doubtless if Kennedy had been there he would have known just what to do. But we could not decide.

"Really," considered Elaine, "I think we had better take Mr. Del Mar into our confidence."

"Still, we have had a good many warnings," I objected.

"I know that," she persisted, "but they have all come from very unreliable sources."

"Very well," I agreed finally, "Del Mar may help us; let's drive over to his bungalow."

Elaine ordered her little runabout, and a few moments later we climbed into it and Elaine shot the car away.

As we drove along, the country seemed so quiet that no one would ever have suspected that foreign agents lurked about. But it was just under such a cover that the nefarious bridge and harbour-mining work ordered by Del Mar's superiors was going ahead quietly.

As our car climbed a hill on the other side of which, in the valley, was a bridge, we could not see one of Del Mar's men in hiding at the top. He saw us, however, and immediately wigwagged with his handkerchief to several others down at the bridge where they were attaching a pair of wires to the planking.

"Some one coming," muttered one who was evidently a lookout.

The men stopped work immediately and hid in the brush. Our car passed over the bridge, and we saw nothing wrong. But no sooner had we gone than the men crept out and resumed work. They had progressed to the point where they were ready to carry the wires of an electric connection through the grass, concealing them as they went.

In the study of his bungalow, all this time, Del Mar was striding angrily up and down, while his men waited in silence.

Finally he paused and turned to one of them. "See that the coast is clear and kept clear," he ordered. "I want to go down."

The man saluted and went out through the panel. A moment later Del Mar gave some orders to the other man, who also saluted and left the house by the front door, just as our car pulled up.

Del Mar, the moment the man was gone, put on his hat and moved toward the panel in the wall. He was about to enter when he heard some one coming down the hall to the study, and stepped back, closing the panel. It was the butler announcing us.

We had entered Del Mar's bungalow and now were conducted to his library. There Elaine told him the whole story, much to his apparent surprise, for Del Mar was a wonderful actor.

"You see," he said, as she finished telling of the finding and the losing of the torpedo, "just what I had feared would happen has happened. Doubtless the foreign agents have the deadly weapon now. However, I'll not give in. Perhaps we may run them down yet."

He reassured us, and we thanked him as we said good-bye. Outside, Elaine and I got into the car again and a moment later spun off, making a little detour first through the country before hitting the shore road back again to Dodge Hall.

Meanwhile, on the rocky shore of the promontory, several men were engaged in sinking a peculiar heavy disc which they submerged about ten or twelve feet. It was held by a cable and wires were attached to it, so that when a key was pressed a circuit was closed.

It was an "oscillator"—a new system for the employment of sound for submarine signalling, using water instead of air as a medium to transmit sound waves. It was composed of a ring magnet, a copper tube lying in an air-gap in a magnetic field, and a stationary central armature. The tube was attached to a steel diaphragm. Really it was a submarine bell which could be used for telegraphing or telephoning both ways through water.

The men finished executing the directions of Del Mar, and having carefully concealed the land connections and the key of the bell, left the spot while we were still at Del Mar's.

We had no sooner gone, however, than one of the men who had been engaged in installing the submarine bell entered the library.

"Well?" demanded Del Mar.

"The bell is installed, sir," he said. "It will be working soon."

"Good," nodded Del Mar.

He went to a drawer and from it took a peculiar-looking helmet to which was attached a sort of harness designed to fit over the shoulders and carrying a small tank of oxygen. The head-piece was a most weird contrivance, having what looked like a huge glass eye in front. The whole outfit was in reality a submarine life-saving apparatus.

Del Mar put it on, all except the helmet, which he carried under his arm; and then, with his assistant, went out through the panel in the wall. Through the underground passage the two groped their way, lighted by an electric torch, until at last they came to the entrance hidden in the underbrush, near the shore.

Del Mar went over to the concealed station from which the submarine bell was sounded and pressed the key as a signal. Then he adjusted the submarine helmet to his head and deliberately waded out into the water, farther and farther, up to his neck, then deeper still, until the waves closed over him.

As he disappeared, his emissary turned and went back towards the shore road.

The drive through the country and back to the shore road from Del Mar's was pleasant. We were spinning along at a fast pace when we came to a rocky part of the coast. As we made a turn a sharp breeze took off my hat and whirled it far off the road and among the rocks of the shore. Elaine shut down the engine, with a laugh, and we left the car by the roadside while we climbed down the rocks after the hat.

It had been carried into the water, close to shore. Still laughing, we clambered over the rocks. Elaine insisted on getting it herself, and in fact did get it. She was just about to hand it to me, when something bobbed up in the water just in front of us. She reached for it and fished it out. It was a cylinder with air-tight caps on both ends, in one of which was a hook.

"What do you suppose it is?" she asked, looking it over as we made our way up the rocks again to the car. "Where did it come from?"

We did not see a man standing by our car, but he saw us. It was Del Mar's man, who had paused on his way to watch us. As we approached he hid on the other side of the road.

By this time we had reached the car and opened the cylinder. Inside was a note which read:

Chief arrived safely. Keep watch.

To this was added something in cipher which might or might not be of vast importance; we could not tell. At all events, I thought I recognised the principle of the cipher, and did not doubt that an hour's application would reveal the secret message.

"What does it mean?" asked Elaine, mystified. Neither of us could guess, and I doubt whether we would have understood any better if we had seen a sinister face peering at us from behind a rock near-by. He was handling a revolver as if about to fire, but, changing his mind, put it away in favour of a method less risky.

We climbed into the car and started again. As we drove off the man came from behind the rocks and ran quickly up to the top of the hill. There, from the bushes, he pulled out a peculiar instrument composed of a strange series of lenses and mirrors set up on a tripod.

Eagerly he placed the tripod, adjusting the lenses and mirrors in the sunlight. Then he began working them, and it was apparent that he was flashing light beams, using a Morse code. It was a heliograph.

Down the shore on the top of the next hill sat the man who had already given the signal with the hand-kerchief to those in the valley who were working on the mining of the bridge. As he sat there, his eye caught the flash of the heliograph signal. He sprang up and watched intently. Rapidly he jotted down the message that was being flashed in the sunlight:

"Dodge girl has message from below. She and Jameson coming in car. Blow first bridge they cross...."

Down the valley the lookout, without waiting for more, made his way as fast as he could. As he approached the two men who had been mining the bridge, he whistled sharply. They answered and hurried to meet him.

"Just got a heliograph," he panted. "The Dodge girl must have picked up one of the messages that came from below. She and Jameson are coming over the bridge now in a car. We've got to blow up the bridge as they cross. Dangerous to attempt holding her up in daylight on the highway. Wreck the bridge, and they'll never be missed."

The men were hurrying now toward the bridge which they had mined. Not a moment was to be lost, for already they could see us coming over the crest of the hill.

In a few seconds they reached the hidden plunger firing-box which had been arranged to explode the charge under the bridge. There they crouched in the brush ready to press the plunger the moment our car touched the planking.

One of the men crept out a little nearer the road. "They're coming!" he called back, dropping down again. "Get ready!"

Del Mar's emissaries had not reckoned, however, that any one else might be about to whom the heliograph was an open book.

But, farther over on the hill, hiding among the trees, the old farmer and his dog were sitting quietly. The old man was sweeping the Sound with his glasses, as if he expected to see something any moment.

To his surprise, however, he caught a flash of the heliograph from the land. Quickly he turned and jotted down the signals. As he did so, he seemed greatly excited, for the message read:

"Dodge girl has message from below. She and Jameson coming in car. Blow first bridge they cross. Safest method of dispatch under the circumstances."

Quickly he turned his glasses down the road. There he could see our car rapidly approaching. He put up his glasses and hurried down the hill toward the bridge. Then he broke into a run, the dog scouting ahead.

We were going along the road nicely now, coasting down the hill. As we approached the bridge, the farmer, who had been running down the hill, saw us.

"Stop!" he shouted.

But we did not hear. He ran after us, but such a chase was hopeless. He stopped, in despair.

With a gesture of vexation he took a step or two mechanically off the road.

Elaine and I were coming fast to the bridge now.

In their hiding-place, Del Mar's men were watching breathlessly. The leader was just about to press the plunger when all of a sudden a branch in the thicket beside him crackled. There stood the farmer and his dog!... Instantly the farmer seemed to take in the situation.

With a cry he threw himself at the man who had the plunger. Another man leaped at the farmer. The dog settled him. The others piled in and a terrific struggle followed. It was all so rapid that, to all, seconds seemed like hours.

We were just starting to cross the bridge.

One of the men broke away and crawled toward the plunger box.

Our car was now in the middle of the bridge.