RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The illustrations for this story have been omitted. They were drawn by George Brehm (1878-1966), whose works are not in the public domain.

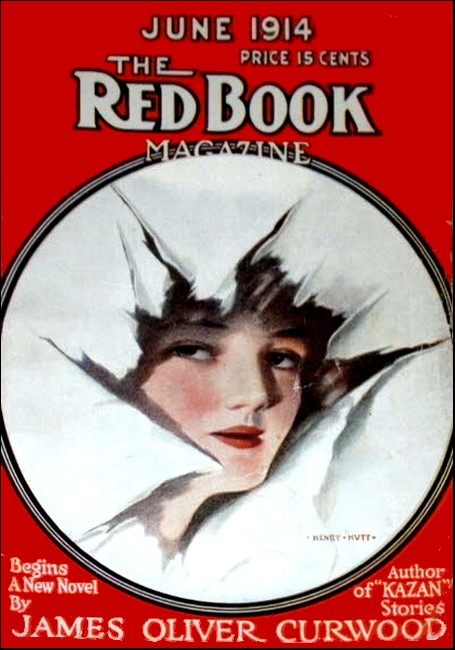

The Red Book Magazine, June 1914,

with "In the Cave of Aladdin"

THE wealth stowed in the vaults of the American-Empire Trust Company was protected by every device of steel and invention known to human ingenuity. It would be impossible for anyone to enter and rob those vaults. Yet some one did do that very thing. That is the sort of mystery Arthur B. Reeve tackles in this story, through the medium of his scientific detective, Guy Garrick. And like all the work from the pen of Mr. Reeve, both the mystery and the method of solution are scientifically correct. His stories bring to fiction all the amazing discoveries of scientific men of the day. They stand the acid test.

"GARRICK, the impossible has happened," exclaimed Colonel Van Loan, of the American-Empire Trust Company, as the young detective seated himself beside a big double mahogany desk.

"The impossible?" echoed Garrick, taking in at a glance of his camera eye both the sumptuously furnished office with its thick carpets, its easy chairs and general air of affluence, and the huge-framed, carefully-groomed magnate who presided over the destinies of fortunes that would have shamed Croesus himself.

Colonel Van Loan swung around in his chair, his head forward.

"I have sent for you, Garrick, because—well, I have heard of your scientific work, and this is a case that requires something more than any detective agency is capable of. I'm willing to take a chance with a young man like you."

He paused. Garrick said nothing. The word was ringing through his ears —"the impossible." What did it mean?

Colonel Van Loan hitched his chair a bit closer to Garrick.

"The new vault of the American-Empire has been entered and robbed," he added in a low whisper, "and there is apparently not a clue."

With an effort, Garrick stifled an exclamation of incredulity. Van Loan watched him keenly.

"Why, sir," resumed the magnate, "if that can happen, no one is secure—not even the Government itself. Currency and securities up into the billions are easy prey to some cracksman. Think of it, man: every vault, however impregnable we have considered it, is like so much paper—worthless."

"How do you suppose it happened?" asked Garrick, eagerly.

"None of us has any idea," replied

Van Loan, rising and pacing the floor helplessly. "Of course, being a detective, you are acquainted at least in a general way with the safeguards that are thrown about valuables, nowadays."

He stopped before the detective. Garrick nodded.

"Some one has broken them all down. We have found bags of lead substituted for bags of gold, packages of brown paper in the place of banknotes, and worthless envelopes where negotiable securities ought to be. It is the most incredible case I have ever heard of—staggering. Some one has avoided the network of wires, has been able to defy the half-dozen massive bolts on the ponderous doors of our vault, has penetrated the thick walls of steel and concrete—somehow—as if, well, as if he were a thief in the fourth dimension."

Garrick tried to reason it out. Here was a burglar-proof, fire-proof, bomb-proof, mob-proof, earthquake-proof vault with all the human, mechanical and electrical safeguards that modern science could devise. Yet it had been entered.

"Has a trusted employee gone wrong?" he suggested, tentatively.

"Impossible," asserted Van Loan emphatically. "No one single employee could get in there alone for an instant. We have the double custody system. It takes at least two to get in there."

"A conspiracy?" queried Garrick, still sparring for time.

Van Loan shook his head. "I am one of the two," he replied quietly.

Just then the door opened. Van Loan turned, and a woman entered, a young woman, demure, dainty, chic.

"You will excuse me—ah. Miss Gaylord?" greeted Van Loan quickly. "I'm very busy just now. Can't you come in later—about noon?"

"Surely," she smiled, with a quick look at Garrick. "I beg your pardon."

"The little manicure in the barber shop downstairs." explained Van Loan, as she left. "I have my nails done perhaps oftener than is absolutely necessary. But I believe in patronizing the tenants of our building and as I'm too busy to leave my office, Deitz, the barber downstairs, sends her up here. I don't know how she got past my secretary, unless it is because the news has disorganized all of us—who know it," he added with a significant nod at Garrick that the thing was to go no further until it was impossible to conceal it longer.

Garrick had looked at her curiously. Was it one of those hundred and one irrelevant things that one runs across in taking up a case, or was it pertinent? At any rate there was no time for such speculation.

Van Loan had pressed a button under his desk and a boy answered.

"Ask Mr. Fordyce to come in a moment," he ordered, then added to Garrick "—the cashier. When I said we had the double custody system. I didn't mean I was the one who had part of the combination of the outside doors. We have what we call a 'custody trust' of large estates—a department for those who are too rich to want to bother with their actual securities. It is a sort of vault within a vault where those securities and other valuables are kept. The American-Empire handles everything for such customers. Fordyce and I have the combination for that inner vault. Fordyce and Kenton, his assistant, have the outside combination for the big door. But it is that inside vault that has been robbed—which makes it all the more impossible to understand. Mr. Fordyce, this is the detective, Mr. Garrick. of whom I spoke to you when we made the discovery this morning."

Fordyce shook hands. He was a quiet-spoken man, one who showed that he had long been accustomed to handling other people's money, not a wealthy man himself, but of a good family that had been in banking of one form or another for many years.

"You can well imagine, Mr. Garrick," he said, "the consternation we felt when we opened the vault this morning to get some papers of the Longmore estate and found such a condition. Even yet we do not know the extent of the loss. It will take days to go over everything and check it up—to say nothing of finding out how it happened."

Garrick thought a minute.

"Let me see," he said finally, "how could we trace a robbery, supposing it possible, from the street to the securities, after nightfall?"

"We shall be glad to go over the ground with you," answered Van Loan, leading the way from the office and talking as he went.

"First, there are the locked metal doors from the street. They close some time after eight and no one of the tenants of the building or anyone to see them, if they are working late, can get by without being observed."

They had come to the flight of steps that lead down to the vaults themselves.

"Next there is another iron door," pointed out Van Loan, leading to the stairs. Then at the foot of the stairs is a heavy barred steel door and a mirror placed at an angle so that a night watchman here can see in either direction."

Garrick looked quickly about. There in the antechamber in a rack stood two shining guns ready for an emergency.

"And," added Van Loan, "at last we come to the main door of the vault itself."

He paused before the ponderous mechanism, which now was swung open for the day's business.

"The door of a modern vault," he explained, "is a very complex affair. This one contains several thousand different pieces, each ground accurately to the thousandth of an inch. It is over a foot thick, as you can see, and weighs perhaps ten tons. Yet a child can swing it on its specially designed hinges."

"H'm," mused Garrick, "four complicated locks to be picked, one of them a lock of latest pattern shielded by impregnable armor."

Suddenly an idea flashed across his mind, suggested by a case of which he had heard. He bent down and examined the time lock. No, it seemed to be in perfect order.

"What are you looking at?" inquired Fordyce quickly.

"I recall a case," he remarked, "where the time lock on a safe had been rendered inoperative and it was never discovered until after the robbery because no one ever tried to get in until the correct time. But this lock seems to be all right."

"To say nothing of other locks inside," put in Van Loan, "and a network of sensitive electric wires, the burglar alarms concealed in the walls and floors and the location of which is not generally known."

They had passed the door, the last line of defense. There opened up a veritable cave of Aladdin. Everywhere was money in every shape and form. It was as though a modern Midas had passed through and with his magic touch had transformed everything into money, beyond the wildest dreams of avarice.

"And the vault itself—the walls?" queried Garrick. tapping them casually.

"The body of the vault," answered Fordyce quickly, "is built up of steel plates bound together by screws from the inside of the vault so that the screws cannot be reached from the outside. The plates themselves are of two classes, those of hard and those of softer steel, set alternately so as to he both shock-and drill-proof. The steel of high tensile strength is used to resist the effect of high explosives, while the other has great resisting power against drilling. It will wear smooth the best of drills, and only unlimited time would suffice to get through that way.

"Then there is a layer of twisted steel bars added to the plates, another network to break any drill that may have survived the attack on the steel plates. That also adds to the power of resisting explosives. In fact, the amount of explosive necessary and the shocks that it must produce simply put that method of getting in out of the question.

"Why," he went on, "where the outside plates come together to form the angles and corners, massive angles of steel are welded over the joint. The result is a solid steel box, all embedded in a wall of rock concrete—impregnable—absolutely impregnable."

He paused.

"The door is the only possible chance. That is water tight, seven-stepped, ground to the minutest fraction of an inch. The most expert yeggman who ever lived would have no chance at that—unless he were a lock expert, endowed with omniscience. So you see why it is that we say that the impossible has happened."

Inside the huge vault were various other protections, tiers of safety deposit boxes for which an elaborate system of safety had been built up, safes for various purposes, and in the far corner a vault within a vault, the vault of the "Custody trust department."

Van Loan opened it with Fordyce's aid, each knowing only part of the combination and neither being able to work it in such a way as to be seen by the other.

In this inner vault were rows and rows of fat packages tied with little belts of red tape. Van Loan picked out one and opened it.

Instead of crinkly examples of engraving that represented a fortune, there was nothing inside but common brown paper, as though it had been stuffed in merely to satisfy the casual glance that the envelope had not been tampered with.

He opened a small, heavy money-bag which he took from a little safe in one corner in which some wealthy people kept currency against time of panic when gold might be at a premium, Garrick looked in. Instead of bright, gleaming gold-pieces there was a mass of dull, dross—lead!

"What do you make of it?" asked Fordyce helplessly.

Garrick looked from him to Van Loan. Neither apparently even laid claim to having an explanation. He tried to reason it out himself. Only one idea occurred to him. Why had the robber been so careful on the surface to conceal his stealings? Clearly, he was not through. He had carried on his theft for some time, not all at once. Perhaps he was not through yet. Perhaps he intended to come back. Surely the temptation of what remained still would be strong. A half-formed plan flitted through Garrick's mind, but with his natural caution he said nothing about it.

Instead, he shook his head slowly. "I shall have to do some outside work before I can even attempt to answer that," he said simply.

As they turned to pass out, he noted a telephone on the wall, and paused before it.

"That, I suppose," he said, "is to communicate with the outside in case anyone is shut up here."

"Yes."

"Well, I am going up to my office," went on Garrick, "and then I shall want to come down here again. May I?"

"By all means," answered Van Loan quickly. "You—you don't intend to stay in the vault?"

"Of course not," answered Garrick.

"I gave you credit for better intelligence," smiled Van Loan. "You would be suffocated, you know."

"Oh, of course. But will you have the time lock on the outside door left inoperative?"

Van Loan thought a moment. "That's an unprecedented thing," he remarked finally, looking at Fordyce, who said nothing. "Do it, Fordyce," he ordered at last.

As Garrick left the two officers, he walked out through the antechamber of the vault; then, instead of leaving the building he began to reconnoiter, keeping in mind the location of the vaults.

He was passing by the barber shop in the basement, and glancing in, when his eye caught the trim figure of the little manicure, Miss Gaylord. She recognized him, and he decided to enter. At least time spent in talking to a pretty girl was not wasted, although it might not take him nearer the solution of the tremendous problem which had so suddenly been put up to him.

Soon they were chatting across the little white table, while Garrick now and then observed the men in the barber chairs, the various barbers and the head barber, a middle-aged man, rather good looking, and apparently a little hard of hearing, whom he heard the customers refer to familiarly as Deitz.

"I suppose you have some well-known customers in a building like this," ventured Garrick, observing but apparently with his eyes averted from Miss Gaylord's face. "And some queer experiences, too."

"Yes," she answered, engrossed in her work, "but I like it. I take it all as it comes. It interests me. Do you know, character can be read by the finger nails, just as well as by the hands?"

"You don't mean it," he prompted.

"Yes. You see, I have quite a philosophy of finger tips. I have studied from actual people, some of them prominent men in various ways."

"How about mine?" he asked, taking a sudden interest in her.

"Well, for instance, you have the scientific temperament, I should say. You will pardon me—but it is usually known by one of the worst nails and cuticles that the manicure encounters. See—a nail of ordinary size, rather discolored, the cuticle so erratic that it takes a good deal of skillful work to make it look beautiful."

"And our friend, Colonel Van Loan?" he asked.

"He has a large, broad nail, the nail of a good liver, a good spender, a man of good nature."

"You know Mr. Fordyce?"

"He comes in once in a while. He has an aristocratic nail."

"How about—er—Mr. Kenton, his assistant?"

She looked up quickly.

"You know them all?" she asked.

"Oh, slightly," he answered.

"They seldom come down here." she resumed quickly. "Besides. I don't like to talk too much about my customers. You wouldn't appreciate my talking about you to them, would you?"

Garrick smiled, and turned the subject, but as he left the shop he remarked to himself, "An unusually clever girl, that Miss Gaylord."

Garrick's office was a modest suite in one of the new huge tower buildings a little further uptown. He did not stay there very long, but from a cabinet took a queer little arrangement, somewhat like a coil of coated wire.

In an adjoining room two men were reading papers. They were two of the operatives he kept for shadowing and other purposes.

"McCorkle,"—he beckoned to one. then in a whisper added—"I've a case down at the American-Empire vaults. I wish you'd just scout around there, get acquainted with the place, any of the employees, if you can. But keep in touch with the office here. I may need you at any moment; and don't let anyone see that you know me. if we should run across each other."

Half an hour later, Garrick was back again at the vaults and Van Loan had directed his secretary to accompany him on a second visit to the custody vault, which had been left open but under guard for him.

As they passed down together again among the various safe-guards. Garrick remarked, "And yet all this did not apparently protect."

"No," observed the secretary, an alert and active young man of good education, "no, in spite of all the elaborate precautions, the wonderful mechanism, the inquisition of clients and our costly system of identification, the system has fallen down somewhere."

"Who is Kenton?" inquired Garrick casually.

"The assistant," replied the secretary. "Rather a clever fellow—always on the job."

"I wonder if he knows anything more than has been told," said Garrick, apparently thinking out loud.

"Impossible," exclaimed the secretary; then, catching the drift of the remark, he added, "You mean, could it have been an inside job? Mr. Garrick, do you realize that no one could carry away much gold in the daytime, even if for a few minutes he had a chance alone down here in the vaults. Half a million weighs a ton."

"Yes," persisted Garrick. although his mind was evidently not on the remark, "but a man could stuff a good deal into an inside pocket."

He was talking to divert the secretary's attention from what he was doing, for in the meantime he had taken down the wall telephone in the custody vault, and in an inconspicuous corner had quickly attached the peculiar little arrangement he had brought from the office, in such a way that it was exposed but not noticeable.

"Is there a little office upstairs that I may use?" Garrick asked of the secretary, without saying why he wanted it.

A few minutes later, the arrangements were made and Garrick was ensconced in an office of his own, with a desk, telephone, and a key to the door, so that he could come and go as he pleased. For an hour or two he was hard at work making connections by wires with the telephone leading out through the wall from the custody vault. That finished, it was a comparatively simple arrangement that he placed on the top of his desk. It consisted of nothing, apparently, but an ordinary electric alarm bell, with another relay and dry cells.

During the rest of the afternoon Garrick stuck pretty closely to his little improvised office, taking care, however, to get acquainted with such of the employees about the building as would be necessary in case he needed to get in at night. Outside, he had stationed McCorkle and arranged to keep in touch with him.

Still, nothing happened during the day and as closing time for the banking day approached, Garrick sought out Van Loan to find out exactly how he might keep in touch with him during the evening, as well as with Fordyce and Kenton.

"I may need you at any time," he said, "and when I do I shall want you all quickly."

"Where?" asked Van Loan.

Garrick thought a minute. "I can't say, just yet. But if I can depend on you to keep in touch with Fordyce and Kenton, it may mean a great deal."

"Very well, then. You can usually find me at my club until after dinner. To-night I shall be at the theatre; I'll leave the number of the seat at the club office. As for the others, I'll instruct them to take similar means to keep in touch with me. You can depend on it."

Hour after hour of the evening sped by, and still Garrick was waiting, chafing at the inaction in the little improvised office. Over and over in his mind he turned the meager facts which he had collected so far. And as he waited, he grew more determined to see the thing through.

On one occasion when he had McCorkle on the wire, his heart gave a leap and he could scarcely restrain an exclamation of satisfaction.

"A car has just driven up to the curb around the corner from the entrance to the building," announced the operative.

"Did anyone enter the building?" asked Garrick quickly.

"No."

"Then watch it. Don't let it get out of your sight. McCorkle. It may be important."

Garrick had made up his mind to let no chance go untested. There was a possibility here. If the car was standing there to convey some one away, with the driver ready to slip into his seat at a moment's notice, throw in the clutch, and whirl away, he knew he could depend on McCorkle to take charge of that end of the affair.

It was queer at any rate. Garrick had learned from long experience that the automobile as a means of escape had made crime much more difficult to detect, that motors were becoming one of the worst of modern criminal weapons. Perhaps the trail led to some gangster's garage, dark, unpretentious, one of the mushroom growths of such places which had sprung up all over the city. From such places, at least, came the cars, often stolen and repainted, in which gangsters traveled on missions of plunder or revenge, conveying them swiftly to their quarry and as swiftly away.

Suddenly the little bell on his desk gave a faint tinkle, then louder. He strained his ears. Yes, there was no mistake about it, this time. It had settled down into a continuous buzz.

Quickly Garrick called Van Loan at the Club. He was not in, but he had left instructions how to reach him at the theatre and how to reach both Mr. Fordyce and Mr. Kenton. The entire telephone service of the club was to be put in service instantly at his expense.

Garrick rang off and got his office, leaving word to connect McCorkle instantly should he call up from the pay station which he had discovered across the street.

There was nothing to do but wait, now. Yet there was the tinkle of that little bell. Had he made a mistake in not telling them all of his plans? It had always been his rule that the fewer people he took into his confidence the fewer weak links there would be in the chain of evidence he was forging.

At last McCorkle answered. "Mac," fairly shouted Garrick. "has anyone entered the building from that car or any other?"

"No, sir."

"Then watch the door. Don't let anyone out at all—no one. Understand? I am ringing up to have some one there to back you up—"

"Mr. Garrick." interrupted McCorkle, "from where I am standing I can see a big black limousine which has just drawn up to the door. Three men have jumped out and are going into the building. The car is waiting."

"Then get over by the door—quick. There will be some one there to help you out if anything should happen. Only play safe—until you hear something suspicious from the inside. Then pull the gun on them—and, McCorkle, remember, in these quiet streets downtown a police whistle may be better even than a gun at night."

Garrick had scarcely finished a hurried call for reinforcements for his man outside, when his door, which he had left unlocked, was flung open after the hasty shuffle of three pairs of feet down the marble corridor of the hallway.

He leaped to his feet, his hand on his gun.

"What is it—what's the matter?" cried Van Loan, who was the first to enter. "Where are they?"

He had seen Garrick's automatic and had quickly assumed that he was holding some one at bay.

Garrick laughed, then motioned to the still tinkling bell.

"What is it?" asked Van Loan, pointing down at the bell.

"Down there in the custody vault I have placed what is known as a selenium cell and a relay, attached to the telephone wire and leading up here. Now that you are all here," he added, turning to Fordyce and Kenton, "let us open that vault. You see, now. why I left that time lock inoperative. Something is going on down there. Come on," he added, dashing down the stairs.

"Selenium?" puffed Van Loan, as he followed.

"Yes," called back Garrick. "Hurry! It is a peculiar element, a poor conductor of electricity in the darkness, a good one in the light. I reasoned it out this way. Suppose some one should enter the vault. The first thing necessary would be to switch on the lights. That would act on the selenium cell, complete the circuit; then this bell would ring."

It seemed incredible. Down below, hidden by the impenetrable steel walls and doors, there was a light shining on the tiny selenium cell tucked away in the custody vault.

Some one was there!

It was weird, as if a phantom hand had reached through the cold steel and turned on the lights.

One half expected to see the heavy steel door open, perhaps the night watchman killed.

But, no. The door was closed, just as Fordyce and Kenton had left it; the night watchman was sitting there vigilantly on duty, more surprised than they at seeing Van Loan and the rest at that lime of night.

One after another, the heavy bolts were shot back as Fordyce and Kenton worked the combination.

Inside the big vault all was darkness.

Next Van Loan and Fordyce began to work over the door of the smaller vault in the rear corner. Finally it swung open.

There was burning a bright light!

What was it—an incandescent witness to man or devil? Unconsciously they drew back for an instant as the door swung noiselessly open. Yet no one was there. Apparently not a thing was disturbed.

"He must have escaped!" exclaimed Fordyce.

"Escape!" rejected Kenton, looking at the thick walls and the doors through which they had just entered. "It is impossible. It simply cannot be."

Garrick was going over the interior of the vault carefully and quietly, without a word. It seemed hopeless. No one could have got out. Yet there was no one there. Van Loan stood speechless.

Garrick had come to the small safe standing in the corner. He paused.

"Come," he shouted, "give me a hand."

Together they moved it. It rolled surprisingly easy on its well oiled wheels.

"Look!" cried Garrick, who was nearest.

There, in the smooth steel wall, yawned a black hole, big enough for a man's body to wriggle through.

The wall had been penetrated by a careful calculation which brought the hole just behind the safe. Then with a lever the intruder had been able to move the little safe back and forth to hide the entrance through which, night after night, he visited the treasure house.

Without a moment's hesitation. Garrick plunged into the hole, wriggling his way along, and calling back from time to time as he progressed.

"It runs into the basement of the building," he panted, "and ends back of a closet in the barber shop. One of you come through after me; the other two hurry around to the barber shop."

He wriggled on through the tunnel. A moment later Kenton followed. Fordyce and Van Loan started around the other way.

All was dark in the barber shop. Not a soul was there. Apparently both Deitz and his fair manicure had long ago shut up the shop and left it. Who was it that had used it during the long, silent hours of night?

Garrick switched on the lights. In a closet he disclosed two large, bolt-studded tanks, like boilers, with dials and stopcocks and tubes attached.

He stooped and picked up a goose-necked instrument, like a distorted, doubled U, with two parallel tubes fastened together, and nozzles at the end.

"What is it?" asked Kenton, surveying it with awe.

"A cutter-burner—an oxyacetylene blow-pipe, with which steel can be cut with scarcely more effort than is required to slice cheese with a knife," replied Garrick, handling the thing eagerly.

"It is well-known," he went on, "that steel burns readily in an atmosphere of oxygen. It's all the same—hard or soft, tempered, annealed, chrome, Harveyize. It will cut cleanly through them all. The upper of these tubes carries the oxygen from a tank, the lower the acetylene from another. Here is the mixing chamber. They give, when they are lighted, a temperature of six or seven thousand degrees Fahrenheit, so great that if a cone of unconsumed gas, forced out under pressure, did not protect it, the nozzles themselves would be consumed."

Kenton looked at Garrick aghast.

"Robbery with this gang," he blurted out almost with awe. "must have been an art, as carefully strategized as a promoter's plan or a merchant's trade campaign."

"Yes," agreed the detective. "Night after night the thieves must have worked patiently, noiselessly, with the blow-pipe, cutting away the steel, removing the rock concrete, carefully they must have calculated to come out just back of the little safe. It looks as if they must have some inside knowledge to do that and avoid the network of wires."

Suddenly Fordyce broke in on them, pale and excited.

"Garrick!" he cried. "There has been an attempt on Van Loan's life."

"What?" exclaimed the detective. "How did it happen?"

"We were coming through the hall as you directed. As we reached the door to the street I turned. For a moment I thought Van Loan was going out on the street instead of—"

"Yes—yes." interrupted Garrick, suddenly thinking of McCorkle and his probable action under the circumstances.

"—instead of coming here with me. But no. There was a woman facing him—a woman and a man, at the door. She drew a pistol, a little ivory-handled pistol, and fired squarely at him. I saw my chance. Before she could fire again. I seized her arm and wrenched it from her. Here it is."

He handed the pistol, still warm and smoking, to Garrick.

"The man was not armed. I think. But with Van Loan wounded, they were two to one against me. Hurry!"

"A woman?" asked Garrick, following quickly. "Who?"

"I think it was that Miss Gaylord—the little manicure in the barber shop. The man I couldn't see very well. But outside, on the street, there seemed to be another man holding them back at the door."

"McCorkle," exclaimed Garrick quickly. "That's the way it is. Always in these enterprises there is a woman."

Garrick rushed up to Van Loan, who was weak with the shock and the loss of blood from an ugly wound in his left shoulder, bracing himself gamely against an angle of the now deserted cigar-stand in the lobby.

"How did it happen?" he asked, tearing a strip from the shirt of the wounded magnate and hastily improvising a tourniquet. "Here, Kenton, twist that—tight. It may stop the flow of blood, while I get help."

"Oh—it's—it's—nothing." groaned Van Loan.

Garrick, with his own automatic in one hand and the little ivory revolver in the other, advanced toward the door. It was locked, or perhaps braced from the street. At any rate, outside he could hear McCorkle giving rapid blasts on his police whistle. Inside was a man, battering and storming at the door.

"Let me out, I say. Let me out. This is an outrage. Let me out."

It was Deitz, the barber. With him, now shrinking into a corner, was the little manicure. Miss Gaylord.

"Come," ordered Garrick as he covered Deitz with the automatic. "Stop that racket—hands up—about face—now march into that corner—straight ahead —and if you turn your head or move a muscle—I'll let you have the whole business in the back of the head. Kenton, Fordyce, some one just watch Miss Gaylord. She's unarmed—but don't let her take any poison or anything like that. McCorkle!"

"Yes, sir," came an answering voice from outside. "They're coming; I hear them now, around the corner."

"Good. Get the cars and the drivers. Then come in here. We're perfectly able to take care of ourselves, now. By that time the door will be unlocked."

"All right, Mr. Garrick."

Garrick turned toward the barber, who was standing sullenly, his face in the corner.

"Deafy Deitz," he said quickly. "I recognized you at once this morning in the barber shop. I thought you might have something to do with this affair, but wasn't sure but that you might have kept straight. You've been out of Joliet a year now, and when you came to New York, I understood you had turned straight. But you couldn't keep straight, could you?"

The man muttered something unintelligible.

"I gave you the benefit of the doubt. But I didn't propose to let you or anyone else get away with anything more without getting caught. If you hadn't been so avaricious, if you had been contented with what you had already, you might have been free to-night."

Van Loan, in spite of the pain, was glaring savagely at both Deitz and Miss Gaylord.

Fordyce by this time had opened the street door and, for the moment, it seemed as if every roundsman below the "dead line" of Fulton Street was pouring into the corridor.

Miss Gaylord was sobbing convulsively.

"Don't be too hard on Deafy," she cried, looking about wildly, and avoiding the savage glare of Van Loan.

"He—we were to get a big haul—but it was—to save the name of another."

She paused, as a bright steel gleam told of the slipping by McCorkle of a pair of bracelets over the wrists of the unresisting "Deafy."

"There was some one." she went on in a low, broken murmur, "who was a million dollars or more short in his accounts—lost every dollar in speculation. He could not return it and it was only a matter of a few weeks when he would be discovered. Running away was out of the question. And so he devised a plan for retaining his good name and at the same time recouping his fortune. It was to have the bank robbed. Enough was there, where he could direct the robbers, to pay them well for their trouble, and to reestablish him. Then, when the robbery was discovered, he would merely add what he had hypothecated to the loss—and make it the greatest robbery since the Manhattan Bank affair.

"He had heard about Deafy Deitz—my husband. He came to him, laid the plan before him. pleaded with him. Begged him. I told Deafy he was a fool. We were happy—had a good business. But the man kept on. He knew the only vulnerable spot in the vault—knew the way to use a cutter-burner in order to reach it safely—had the whole plan for making it seem like an inside job to the detectives, until the real way was discovered.

"I was installed as manicure. Deafy as owner of the barber shop. Every night we worked. But it could not be for long, for fear some one might suspect why we kept the shop open so late when there were no customers.

"At last the tunnel was complete. We did the trick. We were all through. Tonight we were to remove the last traces of evidence in the shop. But the temptation was too great for Deafy. He wanted more. I told him that I suspected something—that I had read the hand of a man who came into the shop this morning, and that he was a scientific genius, that I suspected that man—suspected that some one was not playing fair with us. It was no use. He took the chance. In the midst of it all, we heard the bolts shooting back in the big vault. We crept through and fled. The outside door was locked. We were trapped, like rats. Who had done it? Who had played false?"

Suddenly Garrick turned. He understood it all now.

"Deafy," he interrupted, "you were not the man higher up. This was made possible through some one inside the bank. Your wife has been loyal to you. To save you, she has betrayed the real robber—an officer in the company who was leading a double life."

Deafy muttered something about leniency for his wife.

"No—no!" cried the former manicure. "We go together—not alone this time. I'm sorry I didn't—kill him."

She hissed out the words with a hatred that was inconceivable.

"It's all a lie—blackmail," muttered a hoarse voice.

"That can easily be shown by an examination of the books," ground out Garrick. "I suppose I myself was picked for the role of the young and inexperienced detective who was to fail to discover the actual robbers while he let the real robber escape with the credit of being more astute than the detective on the case, when he discovered the hole in the wall that he had planned himself. I started with the determination to let no one. big or little, slip through my fingers. No one has slipped through."

He turned on his heel.

"Come, McCorkle. I think the police can take care of Van Loan now."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.