RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

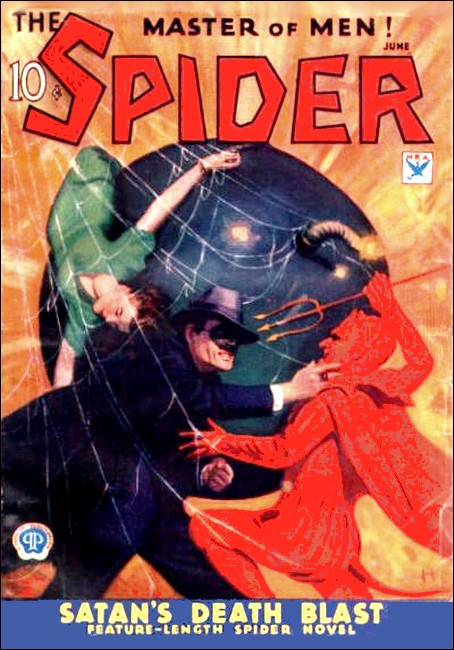

The Spider, June 1934, with "Doc Turner's Death Antidote"

None but Doc Turner, working faithfully in the interests of the neighborhood he serves, could have saved the little Frenchman. None but he could have pierced the mystery veil which hid that murder in the making!

DOC TURNER'S faded blue eyes narrowed thoughtfully as he studied the prescription in his hand. The man who had just handed him the white slip shoved a dollar bill across the counter with stubbed fingers whose nails were black- edged. Doc took it mechanically and said, "Seventy-five cents. Same address, John?"

"Yeah." The huskiness in the man's voice confirmed the evidence of the fine red lines in his bulbous nose. "Three-oh- four Morris Street, top floor, rear." He looked drearily at the quarter Doc was handing him and said, "Say, cantcher break that, mister? Th' old girl ain't got no change an' she might fergit to gimme the jit' if she don't do it right away."

The white-haired pharmacist moved slowly as he went back to the register and rang up a "No Sale." The medicine order was quite ordinary, he thought. It called for two drams of Fowler's Solution and enough elixir of lactated pepsin to make up four ounces, of which the patient was to take a teaspoonful three times a day in water. That made the dose of the arsenical solution a little less than four drops at a time, high but not unusual. It was an ordinary tonic, Doc had made up thousands like it in the years since he had first opened the pharmacy on Morris Street. But there was something wrong. This was the third time in five days the prescription was being refilled, and each bottle should have lasted ten days.

"Way she squeezes it out," John continued his grumbling, "ye'd think it were a dollar. Wanted me to take this 'un up to Norton's 'stead o' here. Fat chance o' me walkin' extry for five measly pennies." What passed for slyness peered out of his bleared eyes. "I didn't say nothin', but when it comes with your label, she'll take it an' like it."

Andrew Turner shot him a startled glance. "How is the patient?" he asked softly. "Getting any better?"

"Dunno. I ain't seen him sence th' old dame come. She ain't let me inside the door. Nobody's gone in 'cept her an' that young snip of a doctor she called. I didn't think Misoor Pellateer wuz lookin' any sicker then he allus did, but she said he wuz dyin' on his feet. She said she wuz his sister an' she wuzn't goin' to let him go any longer without proper attention."

Doc tugged at the mustache beneath his big nose, the white bush that was edged with nicotine stain. There is one per cent of potassium arsenate in Fowler's Solution, he recalled. The patient had swallowed two grains of the poison in five days. Taken all at once that would have been fatal, although in small doses it would not be. But the action of arsenic is cumulative; some of it is passed out in the ordinary bodily processes, but if too much is taken at one time a great deal remains. Eventually, if the ingestion continues, enough will gather in the victim's body to kill him.

"How often does the doctor come?"

"Every day. He's got one o' them new cars thet looks like they been made all in one piece. Th' kids hang roun' it an' I gotter chase 'em away."

The druggist did not go back to his prescription room as the derelict shuffled across the worn linoleum, past shabby but shining showcases, and out into the noise and clamor of Morris Street Doc's eyes were bleak, and his lips were compressed in a thin line.

The physician called daily and would know if his patient were getting an overdose. The symptoms of chronic arsenic poisoning are unmistakable. But...

Doc looked at the printed heading on the paper he held.

Anthony Loring, M. D.

1456

Garden Avenue

IT was an unfamiliar name. But then, the customers of

Turner's Drugstore would not be likely to summon medical aid from

Garden Avenue, although that thoroughfare is only three blocks

away. Wealth dwells in towering, cooperative cliffs on Garden

Avenue. The failures in life, and those yet to win success, form

the teeming population of the warrens that edge Morris Street and

look out on the "El" trains rattling by.

Andrew Turner sighed wearily. He was tired. He was always tired now. He had been doddering about this little drugstore more years than he cared to think. But somehow he couldn't make up his mind to sell the place and crawl off somewhere to rest. A new owner would paint the front and put in a fountain, but he wouldn't take the time or trouble to tell Angelina Patrucci what to give the bambino for the "hurt in da bell," or persuade Rosa Hassenpfeffer to let little Fritz go to high-school. Doc would be the first to deny being something more than a storekeeper, but he knew the people of Morris Street needed him.

"Abe," Doc called. "Bring me that book with the green paper covers."

"Yez, Meester Toiner. Right avay." The intermittent crash of glassware that had been sounding from behind the curtained doorway to the prescription room, stopped. There was a patter of light footsteps, then appeared the pinched, grimy face and weazened body of the errand boy. His bright black eyes were fastened on the volume he carried. "De Medical D'rectory. Eees dot vat you vant, hah?"

"Yes," Doc reached for it, and riffled the pages of the medical list. B—H—M—L. Lane—Leonard—Little—Loon—Loring, John P. No Loring, Anthony. Was he looking in the right county? Yes. There was no Anthony Loring, M. D. listed among the country's licensed physicians!

Doc Turner's scalp tightened. He fancied that letters of red had suddenly appeared across the prescription blank that still lay on the counter. They flickered and faded, but their message was unmistakable. "Murder!" the scarlet letters proclaimed. "Murder!"

THE old druggist came out from behind his sales counter.

He carried a blue carton across which bold letters proclaimed the

virtues of Nastin's Coughex. He went to the show window, slid

open a panel in the backing, placed the carton next to a pyramid

of gaily wrapped soaps. That carton was a signal.

When Jack Ransom, the red-topped, grinning mechanic in the garage around the corner saw it the grin would go from his face and his smiling eyes would grow hard. He would know there was trouble again in Morris Street and that Doc Turner wanted his help.

Abe's ferret-like eyes watched Doc's action from behind the backroom curtain and danced with excitement as his employer came slowly back to him. "Meester Toiner," he piped, popping out from his bailiwick like an animated Jack-in-the-Box. "I dun't like her face, neider. She looks like she bit eet off a piece from a vorm and dun't vant to speet eet oudt because she must got to speet oudt de epple too."

"What the devil are you talking about?"

"De seester from Meester Pellateer vot de perscreeption ees for. Ain't eet I geef her de peckages, hah? Dun't I know eet vot she looks like? Vun teeng I know she dunt look like. She dunt look like hees seester."

"Merciful Providence! You've told me enough times that your 'beeg ears' hear everything, but I didn't know they could hear a man think! Now look here, Abe, I promised your mother that you wouldn't get into any more messes and I'm going to keep that promise. Understand?"

"What's Abie, the boy detective, got for you now, Doc?" The broad-shouldered, heavy-jowled young fellow had come in unnoticed.

"Hello, Jack, I've been disabusing him of his desire to be Dr. Watson. I'm afraid he had an over-exalted opinion of my deductive faculties."

The man in the grease-smeared overalls grinned. "Well, for a counter-jumper you haven't done so badly." Then he noticed the look in Turner's eyes and became grave. "What's it this time? I see the Coughex is out."

"I don't know, Jack. I don't know if it's anything. You know old Pelletier, don't you?"

"Yes. Funny little Frenchman with a goatee that's always limping up and down Morris Street in a rusty Prince Albert swinging a cane. Come to think of it, I haven't seen him for about a week."

"No. He's laid up. And here's the strange thing..." Doc's tone dropped to a covert mumble as he outlined his suspicions. "What do you think?" he ended.

"Does sound kind of fishy. But what would anyone want to poison him for? He hasn't got a cent, lives all alone in a cold water flat over Tony's. Near as I can make out all he ever eats is bread and chocolate, and not much of that." Jack's information about his neighbors was encyclopedic.

"That's what bothers me. It seems so pointless. But he's already taken a dangerous amount of arsenic, and here's this new prescription for me to dispense. It would be easy enough to give him an overdose in water. He'd never tumble even if he read the label."

"Maybe this sister is making a mistake; maybe she's giving him a tablespoonful instead of a teaspoonful. Would that make the difference?"

"Mmmm. Just about. A tablespoon holds just four times as much. But the physician should catch that up very quickly. And, besides, why should she have wanted to go to another store?" Doc pondered. "You know," he said at last. "You've given me an idea. If she were questioned that would make a very convenient alibi. She simply made a mistake, with tragic results." He seemed to come to a sudden decision. "I'm going to take the medicine up there myself and talk to her about it. I'll soon be able to judge whether it's an honest error."

"Why don't you call up the doctor? That's what you usually do when there seems to be something wrong, and the patient never knows anything about it."

"I do that when there's something doubtful about the prescription. But if there is anything off-color about the dosage in this instance the doctor, if he is a doctor, is involved. My communicating with him would simply warn them. They'd quit this, but Pelletier would still be in danger. I must dig deeper than that."

SOMEWHERE in the recesses of the tatterdemalion flat

house at 304 Morris Street, corned beef and cabbage was cooking

and its aroma billowed down the creaking staircase as Doc Turner

toiled up through dimness. At every second floor a pinpoint gas

flame gestured compliance with city ordinances, but in the long

spaces between, darkness veiled the dirt, and damp lay heavily on

splintered stair-boards and sagging banisters. Ancient legs were

trembling with fatigue as he reached the final topmost

landing.

"The rear flat, he said," Turner panted. "This must be it," and Doc knocked on the dirt-streaked boards.

From inside the slow shuffle of slippered feet approached. An acidulous voice, sharply feminine, shrilled, "Who ees it?" There was a tight note, of apprehension in the query, but that was indicative of nothing. On Morris Street doors do not open to every knock; collectors and rent-seekers can be parleyed with more effectually from behind locked barriers.

"From the drugstore, lady."

"Un moment!" There was the scrape of a drawn bolt, the click of a turning key. A chain rattled. Then the panel moved inward four inches. A hand appeared, a flabby, fat hand whose skin was chapped and reddened by long contact with harsh soaps.

"Give me! It ees paid."

Doc slipped one foot into the scant opening. "This is the druggist, madam," he said smoothly. "I brought the prescription myself because there is something I must tell you about it. May I come in?"

"Non. No!" The woman fairly exploded. "No one comes in. I am a femme seule, a woman alone, weeth a vairy sick man. In thees wild countree I let no one dans mes chambres."

The druggist's mustache twitched with amusement "I assure you, madam, I have no designs on you. Whatever your charms, and I have no doubt they are many, my more than sixty years of age preclude me from having other than an academic interest in them. What I have to say is important; your brother's life may depend on it."

The door remained obdurately in place. "Tell it me here."

Doc's voice dropped. "Perhaps you would not care to have your neighbors hear what I have to say." He allowed a slight, a very slight note of threat to sound in the next sentence, "I should advise you to listen to me."

He heard a distinct gasp, muted abruptly. There was an instant's silence. Then the door started to open, slowly. "Vairy well. Entrez."

She was taller than he and her opulent curves threatened to burst the confines of a soiled wrapper over which once-gaudy flowers still sprawled their faded splendor. In the light of the dingy parlor to which she reluctantly led him he saw that her round, clammily pale face was distinguished by dark hairs on the upper lip, but it was her eyes that held him.

Something crawled in their limpid, dark depths that made him shudder inwardly. He thought of the women of the Terror who placidly fashioned into their knitting the tale of heads dropping into the guillotine basket.

"Be seated, monsieur." She waved ponderously to a rickety chair. Doc waited courteously till another chair creaked at her bulk. He kept the wrapped bottle on his knee and held his hat over it. "What ees it you 'ave to say?"

The pharmacist did not respond at once. He was listening to the sound of someone retching in the dark room that opened out from this one. The woman's glance flickered uneasily to it and came back to him. "What ees it?"

"This prescription. How have you been giving it to your..."

"My brothair, Monsieur Pelletier? I geev heem a cuillerée—how you say—a spoonful t'ree times a day, like the doctair 'ave say." Her eyes widened questioningly. "Why you ask?"

Did it mean anything that she had said "spoon" without, qualification, or was her apparent difficulty with English responsible? "What kind of spoon?"

"Une cuillère à soupe, a spoon for soup. Eees that wrong, perchance?"

The pharmacist could not make up his mind. Was the growing wonder in her expression, the faint wrinkling of apprehension, real or consummate acting?

Then he sprang it: "You have merely been killing your brother by slow poison. You have been giving him just four times what he should get of a deadly drug."

"Mon Dieu! Oh, Mon Dieu! What ees thees you say?" The flabby fat hands wrung themselves in the vast lap. "I keel my brothair! Boot he say eet. I am sure the doctair 'ave say eet, une cuillerée. I cannot de Anglish read; he not talk de Franch so well. Boot he say it."

A natural mistake? Was it a natural mistake? Why had she tried to get the prescription refilled—somewhere else? Why had the physician given, her a new prescription when a return of the bottle was all that was necessary? These questions flashed behind Doc's immobile countenance. He had a smattering of the language himself, but he would not have known how to make the distinction between a teaspoon and a tablespoon. Were there different words for them in French?

"Marie! Q'est ce que c'est?"

Turner twisted to the feeble voice as he felt rather than saw the woman surge from her seat. His jaw dropped at the apparition tottering through the narrow, lightless doorway. A drab, flannel nightgown flapped about the emaciated shanks of the little man; his cheeks were sunken, hollow. He was a barely moving packet of skin and bones; only the neat little goatee remained to remind Doc of the shabby but dapper Frenchman he had seen so often promenade along Morris Street. But that which turned his blood to an icy stream was the appearance of Pelletier's finger-tips and his toes. The grisly blue that painted these extremities could mean but one thing: that the little old man was far gone on the deathward path of arsenical poisoning. The retching he had heard, the sooty pouches under the dulled eyes, were confirmation.

Rapid French spluttered from the woman like water sprinkled on red-hot metal; her hands vibrated in windmill gestures, her huge shoulders shrugged. But Pelletier's gaze sought and found the visitor. "Monsieur Turnaire," he breathed, in his ghost of a voice, "you are come to help me. I..."

"Pierre!" the woman he had called Marie shrieked. "You are too seek, you will keel yourself." She swooped down on him, a billowing, smothering bulk. "De doctair 'ave say you must not come out of de bed." She swept him up, literally, and bore him back into the shadows.

"Hello, Marie! Why is the door open? You..." Turner jerked to the new voice from the entrance. A tall, slim-waisted young man entered, anger darkening his sharp, saturnine features. He checked himself as he saw the druggist; the dark glow on his face vanished. "I beg your pardon," he bowed. "I thought Mademoiselle Pelletier was alone. It is unwise to leave doors open in this house." His eyes were pin-points of interrogation.

Doc mumbled something purposely vague. This fellow must be...

"Doctair Loreeng!" Marie was back. "I am glad you 'ave come. Thees is de pharmacien who 'ave tell me he sinks I geef Pierre too much of the medicine. You 'ave say to geef a spoon, hein? A spoon grande?"

Expression fled from Loring's face; it was masklike. Doc was conscious of a sudden surge of admiration at the dexterous way in which the woman had put the other in possession of the situation. It could not have been accidental.

"A big spoon! Why no, mademoiselle. You haven't been giving him tablespoonful doses have you?" Just the correct amounts of surprise and reproach were contained in his suave voice. "I meant a small spoon—what we call a teaspoon!" Then sudden realization of the implications crescendoed his tone. "Good Lord! He's been getting four times the maximum dose of potassium arsenate. No wonder he's been failing so rapidly!"

Again the Frenchwoman's caterwauled "Mon Dieu! Mon Dieu! What 'ave I done!" accompanied the wringing of her hands. "I 'ave keeled my brothair. Bettair I should 'ave stayed in Bordeaux den come here to keel heem." She sobbed. "An' all I wanted was to make hees last days le plus comfortable what I can." She collapsed into a decrepit sofa that staggered under the impact. It was well done, Doc thought; the couple might have rehearsed the scene. Perhaps they had.

Loring was addressing him. "This is horrible, sir. I can't say how thankful I am that you called our attention to this terrible error. I hope it is not too late. May I ask how you happened to catch it, Mr.—er...?"

"Turner—Andrew Turner, Doctor. Simply enough. I was getting too many prescriptions for the mixture. Three in five days. I thought it would be wise to find out what was going on."

"It certainly was. Very." Loring bowed. "You have saved a life, Mr. Turner, thus adding to the long roll of good deeds already to the credit of your co-professionalists. Now, if you will excuse me, I must see what I can do to repair the damage already done. I will do myself the honor to call at your store as soon as I am through here."

BUT Doc Turner was not yet ready to go. He was convinced

now that his suspicions were verified, that he had interfered

with a well-laid murder plot. He settled back in his chair, quite

oblivious of the young man's hint that his presence was no longer

desired.

"You know, Doctor," he said. "I had a glimpse of Mr. Pelletier just now. It seems to me he presented every symptom of chronic arsenical toxemia. I am curious as to how you came to miss that."

Doc could act too. He presented a typical picture of a talkative ancient, settled back for a good chat.

Loring smiled, but there was no humor in his eyes. "It happens that the old man is suffering from an affection of the heart. I ascribed the cyanosis to that." He was explaining away the bluish tinge of his patient's extremities. "As for the vomiting and diarrhea, you know that these are likely to accompany any malfunctioning in a man as old as Pelletier."

Clever. Very clever. Doc was dealing with someone who was shrewd, and very dangerous. His defense, as well as that of the woman's, had been well prepared against the unlikely eventuality of an investigation of their victim's death. But there was one weak link in the chain, a link that had been exposed by the sottish John's laziness. If he were to leave with them the warning he intended, he must point that out.

"Quite natural," he sighed. "I can understand. But," he leaned forward. "But how did you come to write so many prescriptions for the compound?"

The old pharmacist's eyes fastened on the other man's, held them, and there was a tense quivering silence in the room that was somehow only accentuated by the low moaning from the inner chamber.

Loring's thin lips curled in a cold sneer, and threat was almost a hiss in his slow words. "I am afraid you are much too curious, Mr. Turner. Much." His pupils had diminished to a beadlike glittering, strangely reptilian. "You compel me to—take steps."

The woman gave vent to a little scream, quickly hushed, and a blued automatic had leaped into Loring's fingers, was snouting wickedly toward Doc Turner. "You will not ask more inconvenient questions."

Doc shrugged. "That does not frighten me, Dr. Loring. You dare not shoot me here. The walls are thin and the sound of your shot would travel far. Besides, your ingenuity could hardly explain away the presence of lead pills in me. Suppose we declare it a draw. You will have Pelletier transferred to a hospital, and I will promise to forget the results of my—curiosity."

A look of grudging admiration wavered over Loring's chiseled features. But then his eyes grew cold again. "Your proposition does not interest me. My patient is in no condition to be moved from here—alive. And as for you," he bowed again, mockingly, "may I have the pleasure of your company for a half- hour or so. I shall not detain you much longer."

Loring's weapon vanished in a pocket of his tan topcoat, his hand with it. "I can shoot as well from this pocket as outside it. Will you be good enough to remember that as you precede me downstairs?"

Doc rose, and fumbled his hat on to his head. He wondered if Abe would know that the keys to the store were in the register, so that he could lock up. Loring rattled something in French to Marie.

THE ultra-modern lines of Loring's "air-flow" sedan included

small windows that almost hid its occupants from those on the

sidewalk, but Doc could look out through the windshield and see

Morris Street slide by. It was early yet, crowds still shuffled

along the sidewalks picking bargains from the push-carts. Doc's

old eyes said good-bye to his people as Loring twisted the wheel

with one hand and turned west. His other hand was on the seat

between them. The automatic was a hard lump in the pharmacist's

side.

Meager saplings lined both sides of Garden Avenue's select roadway. There was no physician's sign on the ornate grill-work of the little door that was designed to give private entrance to the doctor's apartment on the street floor of the fourteen story structure, but Loring's key turned easily in its lock, and the lobby was distinctly a waiting room. Loring's insistent weapon hurried Turner through a richly appointed office and thence through an operating room.

"Get in there," his captor grunted, and pointed his gun to what was evidently a closet door. "I have a couple of calls to make. After that I shall return to examine Pelletier—and sign his death certificate." A grim smile twisted his mouth. "Then you and I will take a little trip out into the country, from which I shall return alone."

Doc turned the knob and pulled the door toward him. It was very thick and heavy. Within a deep closet showed shelves on which bottles of chemicals were arrayed. He went in, and the door closed behind him. He was in the dark. A key clicked in the lock. He heard the thud of Loring's retreating footsteps, and after awhile, the muffled slam of the outer door. He was left alone, to wait for death.

TO wait quietly for death? Not Andrew Turner, not in a

storeroom where so many chemicals were. The old man actually

chuckled. In the instant that light from the outer room had

flooded in here his practiced eyes had swept the labels of the

ranged containers and found that which he would need. Even

matches, on a lower shelf. He fumbled for those first, found the

box, struck one.

This bottle of white crystals—potassium chlorate, this other yellow with sulphur. He took them down. Powdered wood charcoal was here too, its cork giving evidence of much use. Evidently Loring suffered from indigestion. Lucky he did. Doc knelt, mixing the three powders, black, yellow, white, together on the floor. Not much of each, perhaps enough to cover a quarter. The druggist tore the wax paper covering from one of the other bottles, rolled it deftly into a small cone, inserted the point into the keyhole. Then pinch by pinch he dribbled the grayish mixture he had made into the lock. He tapped the paper funnel and watched the last of the powder disappear.

Now he pulled the cone out and inserted a match in its place, head first. He lit the projecting end of the wooden sliver and watched the slow flame crawl down towards the keyhole. It disappeared within.

And a coughing pow, a puff of acrid black smoke, told him the crude gunpowder had functioned. Doc choked a little as the fumes reached him, then he got his hand on the door and shook it. The shattered lock gave way, the barrier swung open, and Doc was free. Still spluttering, Doc reeled out. A white-covered couch invited him. Loring would not be back for some time, and he was tired, so tired. But he groped out of the operating room, through the office, twisted the latch on the grilled outer door. The air of Garden Avenue was cool, and almost fragrant. Even the smells here were different from those on Morris Street...

"Dere he ees! Meester Toiner. Meester Toiner." That was a voice from Morris Street—Abie's voice. Doc looked up. A battered flivver was drawing up to the curb, Jack Ransom at the wheel, the little errand boy leaning out and waving frantic arms. "Oi, Meester Toiner. Ve been looking fahr you all over."

The druggist scurried across the sidewalk and jerked at the door. "Back to 304 Morris Street, Jack, quick." He was inside the car and it was jerking to a flying start. "Maybe we're not too late."

"Too late for what?" Jack flung the question over his shoulder.

Doc explained quickly. Then, "How on earth did you two show up so opportunely?"

"We got worried when you didn't come back and I sent Abe down to find out what was keeping you. The woman at Pelletier's said you had been there, delivered the prescription, and gone right out. But someone had seen you driving away in a swell new car that turned towards Garden Avenue. So we came over here and were cruising along trying to spot you or the car... Here's 304. What's next?"

Doc looked with narrowed eyes at the lines of an "air-flow" sedan that nestled close to the curb in gleaming beauty. Loring was here already.

"Jack," he snapped. "You come up with me. Abie, you stay here and watch that car. If we aren't down before its owner appears, follow him, wherever he goes."

The same infant squalled behind the same door. Higher up a domestic dispute brawled on interminably. The same corn beef and cabbage smell—a tenuous scream threaded down from the top floor! Doc spurred his failing legs to pursuit of the loping Ransom.

"Locked!" The door to the top floor rear flat was locked. From behind its thin panel dull sounds came; heavy thuds, stentorious breathing. A woman shrilled, "Non! Non! Il est..." Such sounds are common in Morris Street flats; their denizens have learned to display a discreet deafness for them.

"Do we go in, Doc?"

"He has a gun, Jack. You might get hurt." For himself the old pharmacist had no fear, but for this young fellow...

"Hell with the gun!" Jack pulled away from the door, as far as he could get on the narrow landing. Then he had crouched, was hurling himself, a red-topped catapult, at the drab panels. His shoulder struck. There was the splinter of wood and the shriek of old screws driven from their ancient berths. And another sound—the sharp crack of an automatic. Ransom sprawled on the floor within.

Doc crowded in. Loring whirled around to the intruders, his face a pale, pinched mask of fury, his eyes two burning coals. A wisp of smoke curled from the gun in his hand. Marie was a prostrate lump of protoplasm at his feet, her pudgy hand crushed to one cushioned breast and a little trickle of blood welling from beneath her fingers. A bubbling whimper came from somewhere in the vast bulk of her body, and from the dark room beyond there was the sound of feeble, exhausted retching.

Loring's automatic jerked up, and his bloodless lips snarled. With terrible clarity Doc saw a tiny muscle on the ball of the man's thumb quiver in a premonitory twinge to the trigger-pull that would send lead crashing into his now old frame. Marie rolled, and her shuddering bulk thrust against Loring's legs. The man staggered, and Doc sprang.

The little man swarmed over the wiry, young form of his antagonist. The gun spoke, and picture glass crashed on the wall. Then a thick arm reached past Doc's face and a fist thudded against Loring's pointed chin. The pseudo-physician went limp in the old druggist's arms and crumpled to the floor.

Andrew Turner knelt by the side of the huge woman who had saved his life. Her paradoxical mustache was dewed with the sweat of agony; her face was the color of a fish's belly, but her limpid, strangely beautiful eyes were open. Despair peered from them. L'espèce de canaille," she gasped.

"Speak English," Doc said gently. "Tell us about it."

"He ees not Doctair Loreeng," she whispered. "He ees André Pelletier, our néveu. He deed tell me a beeg spoon to geev Pierre—he deed!"

"But why? What did he have to gain?"

"There ees a—how you call—inheritance that come to Pierre, an' after Pierre to André. Pierre, he 'ave reefused eet because de fortune ees made from stealing, but Andre mus' wait teel Pierre die. And he do not want to wait. But of thees I know nodding, I swear, unteel just now. Le sale lâche, he make me to keel my brothair. Oh, Mon Dieu, Mon Dieu!" Her eyes closed and tears squeezed out from between their long lashes.

"Pierre won't die now, Mademoiselle. I'm sure he can be saved."

"Ah non!" Her eyes opened again, and they were pools of torture. "Andre he 'ave geeve all de poison you 'ave breeng to Pierre. He half make heem drink all. Ven I come een an' see he do so I fight weeth heem, an' he shoot me. But it ees no use; Pierre, he die anyway. An' I die too."

"No, Marie. He will not die. There was no poison in the medicine I brought. I left it out on purpose, I wasn't taking any chances. All he drank was a red colored preparation that will do him no more harm than so much good wine. Nor will you die. See, the bullet just went through fat, it is here in your clothes. You'll be all right tomorrow morning."

Steps sounded outside, coming up the stairs. Doc and Jack looked up to see the grimy features of the errand boy peering in the open door.

"I thought I told you to stay downstairs, Abie." Doc Turner's voice was stern, but his eyes were kindly as ever.

"Meester Toiner—they's a cop at that car you told me to watch. He says that its gotta be moved qveek, or else you get a ticket, yet. I told heem—"

The little druggist grinned tiredly. "Run right down again Abie—never mind looking in here; you can't help now—Run right down and tell him that there's more than a ticket coming to the owner of the car. Tell him to get up these stairs—fast!"

"Aw, but Meester Toiner—Shoor, Meester Toiner. Right avay I'm doing it!" And he was gone, clattering down the stairs.

Jack looked up from trussing the hands and feet of the prisoner with his own belt. "He's written his last prescription for a while," he grunted.

The gray-headed little druggist nodded. "It's his turn to take it, now," he sighed. "And I bet he'd rather take slow poison than the prescription dispensed by the judge."