RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

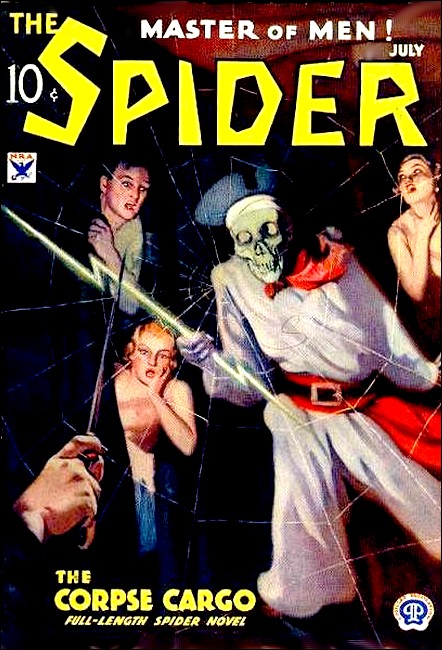

The Spider, July 1934, with "The Murder Torch"

The Morris Street firebug was not concerned with the torture-deaths which accompanied his ghastly work. But Doc Turner, suffering for each new death, vowed that he who lit the murder torch must die!

DOC TURNER switched out the lights of his drugstore on Morris Street, leaving a tiny nightlight hanging over the cash register, and moved wearily to the door. Outside he fumbled in his pocket for the key.

Furtive movement in a dark doorway across the rubbish-strewn street caught his eye. He pretended to be intent on locking his store door but was watching a reflection in the glass panel before him; a slouching figure which darted down chipped tenement steps and scuttled, ratlike and silent, past a darkened store- front to melt into the gloom.

Doc tensed. "Queer," he murmured. "I wonder..."

Somewhere a deep-toned bell bonged twice in the night silence.

The old man twisted the key in the lock and started away for his solitary room, his foot-thuds loud in the stillness. A window screeched open in a warped casing, and a woman screamed: "Fire! Madre de Dios! Fire!"

Doc's thin fists clenched. "Another!"—he groaned—"God in Heaven!" He whirled to the red-painted corner lamppost, his clawed fingers ripping at a brass hook projecting from a red box. The alarm-bell was strident above the screams of the woman at the open window.

"Fire—Fire!"

Andrew Turner hurtled across the gutter, sprang up the low stoop down which the prowler had scuttled only minutes before. He swiftly pulled the inner vestibule door open.

Flame burst out at him, red flame, roaring. Heat exploded in his face. He slammed the door shut, but not before he had seen the red streamers soaring up tinder-dry wooden stairs, up sagging, grease-filmed bannisters. Not before he had gotten one whiff of an acrid, pungent odor that was not smoke-smell.

Doc staggered down the stone stoop to the sidewalk edge. Above him, all up the side of the doomed building, white shapes leaned from open windows; screaming, shrieking in a polyglot pandemonium. He looked at the spidery, rusted fire escapes that crawled up the side of the building, and his face went bleak. Women, fat, unwieldy and clumsy-footed; long-bearded old men; tiny children scarcely able to toddle on level ground, must descend those rickety perpendicular ladders.

A far-off fire-siren wailed mournfully. The distant clangor of a bell hammered brazen alarm. The air quivered with the marrow- chilling panic of that most awful of human nightmares. Fire in the night!

The escape platforms were crowded, packed with white-clad, shrieking forms. Above it all came the thin, helpless wail of an infant. Doc could see its little arms flailing. The wizened father held it under one arm like a bag of potatoes; with the other hand he clung monkeylike to a rung of the ladder, his nightshirt flapping ludicrously about his scrawny legs.

A police-whistle piped. All along Morris Street heads poked out of windows, shrieking. At the nearer end of the second-floor platform, night-garbed figures clotted, and someone cursed. "It's ge-shtuck," a guttural voice yelled. "Mein Gott! Der ladder's ge-shtuck!" The final link in the escape-path, the bottom ladder drawn up to clear the sidewalk, was immovable, its fastenings rusted tight!

Doc's eyes searched, saw a newsstand, padlocked, on the corner. He got to it, got hands on it. Where he found the strength in his slight body was a mystery, but he pulled, tugged, shoved against the flimsy structure till its roof was a few feet under the lowest landing of the fire escape. Hysterical refugees leaped to it, then jumped to the street.

Glass shattered and sharp pointed splinters rained down.

Doc's head twisted up. A long tongue of fire licked out from a top floor window, along the topmost landing. A single form was a black image against the red glare for an instant, then, flaming, it leaped to the flimsy railing, sprang outward, a human firebrand tumbling end over end through red glare. It struck a projecting girder of the "El" structure, bounded off, crunched sickeningly on the asphalt below. A vast, horrified exhalation burst from the still-crowded fire-escape landings.

Rumbling, thunderous sound filled Morris Street; red headlights crashed past him. A gleaming long monster of red and silver was in front of the burning building. Ladders were magically everywhere, rising like long-necked prehistoric monsters. Rubber-coated figures swarmed gnome-like up their rungs even as they rose. Motors banged and popped like a roll of musketry. Water spurted as wrenches twirled; hose snaked across the sidewalk.

A stentorian voice shouted, "Start your water, Forty- three!"

Andrew Turner thought of the slinking figure he had glimpsed, of the kerosene smell. His face was bleak and very grim as he watched the holocaust.

THE daylight straggling into Doc's store was no grayer

than his features; and his eyes were very old, very tired as he

supported himself by his elbows on a showcase to which his back

was turned. A battalion chief in wet white rubber was talking to

a heavy-jowled civilian near the telephone booth at the door, and

the rumble of their voices came clearly back to him.

"What the hell's the matter with the marshal's office?" the fireman growled. "Third touch-off down here this week and you haven't done a thing."

The other's florid face grew two shades darker. "What can I do about it, Brady? We haven't got a sniff of a clue. We usually break these cases by third-degreeing the landlord, but Reggie Vandam ain't buyin' arson, an' there ain't one poor slob in these houses that's got insurance."

Chief Brady scowled. "Maybe it's a bug, Murphy."

The fire marshal's eyes narrowed. "A pyromaniac," he said slowly. "I don't think so. These jobs haven't got the earmarks of a nut's work. But what anyone can get out of them has me stumped. If..." He twisted as the telephone booth behind him opened and a tall man slid out and made for the door. "I've got to scoot." Murphy and the battalion chief exited to the street. Then the store-door opened and an undersized urchin entered.

"Oh, so here you are, Abie!" Turner frowned.

The errand boy thrust a newspaper at his employer with a grimed hand. "Look it," he said. "Peectures from de fire, dey got it alreddy."

"Get the broom and sweep up." The druggist took the sheet from Abe, turned and spread it on the counter. Below the black headlines across the top of the page, the old pharmacist scanned the double-headed text, phrases leaping out at him:

Another four-alarm incendiary fire... Three members of the Wishniewski family, living on the top floor were wiped out, leaving a bewildered three year-old girl orphaned and alone... The charred body of a man, found behind a locked door on the second floor, was identified by a blackened ring as Anton Pavlos, a lodger... A week's reign of terror has spread panic among the poverty-stricken inhabitants as further tragedies are feared...

Doc's long, almost transparent fingers crushed the paper as he read. These people were his wards, dazed-eyed aliens who looked to him for comfort, for aid, for advice in their slow adjustments to the strange customs of a strange land. More than once he had fought off the wolves that prey on the helpless and the poverty- stricken; fought them grimly, relentlessly. And now, once more, dark menace hung over Morris Street, threatening the lives of his people, this time with the most fearsome of deaths.

Against this threat the resources of a city, the skill of experts, were helpless. What could this frail, white-haired little druggist do that was not already being done? "Abie," he called. "Get the Nastins' Coughex and put it in the window."

The boy pulled dirt and crumpled papers out of the telephone booth with his broom. He leaned the long handle against the frame, crossed to a shelf and took down a blue carton. "Oi. Meester Toiner," he whined. "Ve ees got it anodder case, hah?"

The urchin adjusted the blue box to one side of a pyramid of blood tonic. This was a signal, he knew, that Doc Turner wanted to see young Jack Ransom, the brick-topped garage-mechanic from around the corner. It was a signal, too, of trouble for any who would prey upon the denizens of Morris Street.

Abe turned back to his broom, shoved the accumulated debris along the floor and behind the sales counter at the rear. He moved almost wearily.

"What is it, Abe?" Doc asked him gently. "You seem out of sorts. What's bothering you?"

Abe looked up, pushed grimy fingers through his shock of tight-curled, black hair. "Jeemy Wishniewski, vot got boined, was my freindt, Meester Toiner. I dun't feel so good." A single tear trickled alongside his nose.

"I'm sorry, Abe. I—" Doc stopped and turned to the sound of the opening door.

The tall man who had delayed Marshal Murphy entered. He went into the telephone booth, came out almost immediately. "Hey," he grunted, fastening eyes of a pale, indeterminate color on the druggist. "I dropped a paper in here. Anybody find it?"

"I don't know," Turner said slowly. "What was on the paper?"

"Nothing."

The man's tone was blurred, evasive. He came toward the back of the store, his lips scarcely moving as he talked. "It—it was a sample I had to match." His right hand twitched, and Doc saw that the little finger was missing. "I got to have it."

"There ain't no paper here, meester," Abie piped, lifting from behind the counter. "Look it."

There were only cigarette butts, chewing gum wrappers and black dirt in the pile Abe had swept together. "Okay," the man said. "It don't matter, I can get another." He turned, strode away. But at the door he turned, and his face was livid. "If I thought you was holding out on me...!" He gritted, and his eyes were glittering and snakelike as he left.

DOC shrugged. "A tough customer," he mused. "I wonder

what the paper could be."

"Here it ees, Meester Toiner." The boy slid a grayish sheet across the counter. "All de time in mein pocket, I had it."

"You brat!" Doc exclaimed. "Why..."

"I dun't like it de way he talked, und I t'ink maybe is something wrong mit heem. So I stick it away."

"I have the same idea," Doc muttered, taking the paper and looking at both sides. "But there doesn't seem to be anything on this. Yet why should he want it as a sample when you can buy pads of this in every corner stationery store for three cents?"

"What are you up to now?" a cheery voice asked. Doc turned to the squat, powerfully muscled young man who had come in unnoticed.

"Hello, Jack," Doc greeted him. "You're on the job quickly."

"I was across the street looking over the ruins." The smile faded from Jack Ransom's freckled face.

The druggist winced. "I'm afraid there are going to be fires. It's up to us to stop them."

Jack's blue eyes glowed. "I'm with you, Doc! But where are we going to start? Got something?"

"Maybe," Turner ruminated. He showed Jack the paper and told him about the surly visitor.

Jack took up the sheet of paper and gazed at it curiously. He grunted. "There isn't a thing on this."

"Maybe," the wide-eyed Abie offered, "maybe it's got writing from secret eenk on, hah? Maybe."

"Ah," Jack chuckled. "Abie, the boy detective, is on the trail. His keen nose sniffs—"

"Wait a minute," Doc interjected, a faint thread of excitement in his voice. "Wait, Jack. I think the brat may be right. There is something damned important about this sheet,and it isn't the paper. We'll try for secret writing."

In the prescription room, Abe and Jack watched Doc's deft fingers with absorbed intentness. The mysterious paper was suspended within a small glass case so that both sides were visible. Also within the transparent box was a porcelain dish half-filled with dark red crystals, which rested on a small iron tripod beneath which was a glowing alcohol lamp.

"Iodine doesn't burn, or melt," he explained in a tight voice. "It passes directly from the solid state to a vapor. Watch."

Suddenly the scaly crystals in the crucible crinkled at the edges, became perceptibly smaller. A purplish-red vapor filled the small compartment. The suspended paper yellowed.

"Look it," Abe exclaimed. "Jack! Meester Toiner! Look! Dere's somethings on dees side!"

Marks, black marks, were certainly visible. They filled out, joined and became distinct. The paper was no longer blank; scrawled letters and numbers were clearly outlined. "What is it?" Doc squeezed out. "What does it mean?"

A little muscle twitched in Ransom's freckled cheek. "I don't know," he muttered. "I don't know. But, by God, we'll figure it out." He stared at the cabalistic inscription:

M 1306 MU

W 1285 JH

F 1402 PR

St

1290 EQ

Tu 1514 ME

"Jack!" Doc exclaimed. "Those numbers! The first house to burn was 1306 Morris Street. That was on Monday. On Wednesday 1285 went up, and last night—Friday—1402. It's a list of the places that are to be fired and the days!"

The younger man twisted, his face alight. "Jumping Jehosaphat!" he almost shouted. "You've got it! The next one's tonight, 1290. We'll let the cops know. They'll lay for the firebug and get him."

BUT Turner's expression did not reflect Jack's

enthusiasm. "Wait," he said slowly. "Wait. That won't help much.

The incendiary may be only following orders. If he's arrested,

the higher-up will find another torch and carry on. He's the one

we must get to—the man really behind all this. And we can

only do that by figuring out his scheme."

"Meester Toiner," Abe asked. "Vat you teenk dose odder letters iss, hah?"

Doc's eyes quirked. "Hmm. Initials maybe." He thought a minute. "But wait, Anton Pavlos was burned to death last night, and there's no A. P. here."

Doc had unearthed a stubby pencil, was printing letters on a prescription pad. "MU... MU... The devil!" he exclaimed. "Why not? It's the most likely lead, at that!" And he wrote once more, then: "Mutual—I've got it! Look here, Jack." He was rapidly scribbling a list of his own: Mu—Mutual; JH—John Hopkins; Pr—Prudential; Eq—Equitable; Me—Metropolitan. "How does this look to you?"

"I don't know. What's it supposed to be?"

"Insurance companies! Life insurance companies! I'll stake my bottom dollar each one of those lodgers was insured in the company opposite his house number. And if we find a common beneficiary, we've got our man. Jack, call up the first three and check up with their claim departments. Snap to it, man!"

He was waiting when Jack came out of the telephone booth, the prescription pad in his hand. The carrot-topped young man shook his head. "You were half right and half wrong. There was five thousand dollars insurance on the man in 1306, three on the one in 1285, four on last night's victim. But the beneficiaries are all different. The first one is a brother, the second a wife and the third a father. They all live out of town, in different parts of the country."

Doc's eyes narrowed. "But the claims were all in promptly or the claim departments would not have been able to give the information. That's unusual; these roomers are usually drifters and their families never hear from 'em."

"I think you are on the wrong track." Jack frowned. "After all, most of the families around here take lodgers who are drunk nine-tenths of the time. Why shouldn't they get bewildered in a strange house and get burned to death?"

"Nevertheless," Doc responded heavily, "there is a connection. We'll have to work this differently, that's all." He ran a hand through his silky white hair and frowned. "You'd better go to work now. Be back here at eleven this evening. There won't be any sleep for either of us tonight."

THE public hall of 1290 Morris Street was lit only by a

pinpoint gas jet. Shoved under the slant of the narrow stairs

were three decrepit baby carriages. Doc and Jack climbed a single

flight as stealthily as its creaking would permit. The place was

silent. The good people of Morris Street rise early to labor, and

retire correspondingly early.

Doc pointed to a door in whose warped panels there was frosted glass. "Made to order for us," he whispered. "We can lock ourselves in, and no one will see us."

Ransom's low voice was bitter. "I wonder if they have common toilets in the halls on Garden Avenue. And bathtubs in the kitchens."

The outside door rattled below, and there was the sound of heavy breathing, stumbling footfalls. The two prowlers slid into the odoriferous dark hiding place, and applied eyes to the plentiful cracks in the door. The newcomers thumped up the steps, making no attempt at quiet. Doc relaxed, though he kept watching. These were just a couple of harmless drunks coming home.

One dark figure was limp; his legs dragged, and he would surely have fallen had it not been for the other, who supported him. Doc saw the hand on the end of that arm, and his scalp tightened.

A key rattled in a lock, and door hinges complained. Sound of wood against wood signaled its closing. "Hell," Jack grunted. "They—"

The little druggist's palm went against lips, "Shh," he hissed sharply. "Keep quiet." He was quivering.

"What did you see?" Ransom whispered.

"That hand," Turner breathed. "The little finger was missing. It's the fellow who lost the paper!"

The tall man's footsteps passed, clicked rapidly down stairs. The outer door slammed. Jack plunged out into the hall, turned toward the stairs. "Wait," Doc said tensely. "Wait."

"But he'll get away—we ought to follow him!"

"And someone else will fire the house. No! We'll trace him later. I want to know about the man he brought up. He took him in here."

The pharmacist tapped softly at smeared panels. There was no sound from within. "Funny," Doc muttered. "He ought still to be awake." He rapped again, more loudly. A name was scrawled on the door panel in blue crayon. "Schneider," he read it. "One of my customers." He beat a soft tattoo on the wood.

"Wer ist's," a scared, guttural voice called from within.

"Doc Turner, Otto," the druggist answered.

"Ach! Was ist?" The door jerked open. The face of the big-bellied man with a drooping walrus mustache was pale, scared. "Was ist, Herr Doktor?" he asked.

"You have a roomer, Otto?"

"Ja! Der two weeks he iss here; he comes drunk home efery night. Morgen I tell him no longer he can stay."

"I want to see him. Where's his room?"

Schneider turned. "Here!" A door just to the right of the entrance was closed. Doc took a step inside, his foot crunching on some powdery substance. There was a trail of the stuff from the sill of the flat's outer door to the threshold of the lodger's room. Otto struck a match, and Jack came in, shutting the flat door behind him.

Turner took a pinch of the powder between his thumb and first finger, lifted it to the light, then tasted the stuff, tentatively. "Potassium chlorate and lycopodium; fire would flash along it as if it were gunpowder, but there would be no smell afterward," Doc muttered. He whirled to the door of the rented room. "Locked. Jack, get it open."

JACK crouched, sprang before Otto's startled protest was

fairly out of his thick-lipped mouth. The carrot-top's shoulder

catapulted against wood; metal snapped, and the panel moved

inward. Alcohol reek swept out of the dark room as the opening

door pushed some heavy body aside. Light from the hall filtered

in, and Doc saw a long, dark body on the floor, face downward.

The left arm was outstretched, and a heavy signet ring glinted on

a grimy hand.

Ransom stared down. "Dead drunk!" he grunted.

Doc pushed past him and knelt to the limp form, his old hand darting to the wrist of the flung-out arm. His fingers fumbled an instant, then he looked up, his eyes aflame. "Not drunk," he whispered. "Dead."

"Donnerwetter!" Schneider rumbled. "Gestorben! Dead!"

Turner's arm slipped under the corpse's shoulders and turned it over. The fish-belly-white face on the lolling head caught the light, its glazed eyes staring. "Mein Gott!" Otto squealed. "Gott! Das ist nicht... Dot iss not Ryan, dot iss not my roomer!"

Turner lifted erect, his face a grim mask. "No. I thought not."

He bent again to the corpse, pulled out the right arm that was twisted awkwardly under the dead man's bulk. "Look, Jack." The little finger of the right hand was missing, the stump black, charred. "This has been cut off recently, the scar cauterized. And the fellow's clothes are drenched with alcohol and sprinkled with the powder mixture."

"God!" Jack muttered, white-lipped.

There were two white spots on either side of Doc's big nose.

"It's a vile scheme," he said. "Only a fiend could have evolved it. He takes these rooms in various names, takes policies out on himself under those names. The beneficiaries are members of his gang; perhaps really his relatives. When he is ready he picks up a derelict whose build is fairly close to his own. He gets them drunk, perhaps, kills them with an overdose of some drug, and brings them to the rooms he has rented. He's got things arranged so that their bodies will surely be burned beyond recognition when he sets fire to the houses, but they will be identified as he by the missing finger and some piece of jewelry he has made sure will be noticed. Then he collects. If others die in the fires—too bad."

Jack's eyes blazed. "The chair's too good for him!" he blurted, his voice deadly. "I—" He broke off as something thumped against the door of the flat. The trio were suddenly silent, and footsteps could be heard outside, cautious steps that moved away. Doc sniffed. A thin odor grew distinct. "Kerosene!" he muttered.

Jack whirled to the door. "No, Jack," Turner snapped. "You go out to the front, swing yourself down off the fire escape and cut off his getaway. Can you do it?"

Doc, left alone, pulled the hall door open and moved noiselessly out into the corridor. Stealthy movements came from below the stairs. The old druggist felt in his coat pocket, brought out an ancient, rusty revolver. "I don't think this will work," he said. "But he won't know that." Soundlessly he tiptoed to the stair-head.

A lank, shadowy figure was stooped over something down there. The kerosene reek was stifling. Doc's gun snouted in his gnarled hand. "Put them up, firebug!" he grated.

The man below jerked erect, twisting to the sound of Doc's voice. Dim light was just enough to show the snarl on the tall man's face. "You!" he choked. "You!" And suddenly there was the glint of steel in his hand.

Turner pressed the trigger of his gun—and nothing happened. But orange fire flashed from the weapon of the man below, and the druggist felt the wind of a passing bullet. He jumped sidewise, his eyes flashing to the outer door. It was up to Jack now! Where was he?

The incendiary's gun flashed again. But the dart of orange light was downward, to the floor. And flame exploded as the kerosene-soaked wood took the spark. Instantly a sheet of fire rushed up the drenched stairs, hurtled up toward the white-faced pharmacist.

DOC saw the tall man leap for the outer door, saw Jack's

broad-shouldered bulk loom in the opening. As he turned and

scuttled away from the devouring flame the sound of another shot

cracked through the fire's roar. "Too soon," Doc groaned. "He

came back sooner than I thought, and I wasn't ready!" Then he was

shouting, shrieking! "Fire! Fire! Everybody out!

Fire!"

Doors opened. A woman screamed. "Back! Back and out by the fire escape!" the druggist shouted. His brain was an agony. He prayed that the bottom ladder on this house was not stuck, that they would all get out safely. He was pounding on doors, shouting. "Fire! Fire! Out by the fire escape!" Somehow he had climbed a flight, but he could not remember doing it. And just below, flame roared, swirled; reached avid, orange tongues up for him. He could have prevented this. He could have...

A woman's voice wailed, from far up: "Ai, mein Jakey! Help! Help! My Jakey can't move."

Doc reeled against a hot wall, coughing, as black smoke belched up and enveloped him. Jakey! Here, he remembered, Jakey Itskopf lived on the top floor, a crippled fourteen-year-old whose widowed mother altered dresses for a sparse existence. Jake was very heavy, his mother a tiny, weak woman. Jake couldn't move, and his mother couldn't move him. The fire would shoot up the stairwell to the roof and mushroom out. The little pharmacist leaped for the stairs as hot gases swept up past him.

He could escape at will, but he went on up, straining up to that wailing mother-cry under the roof, at the point of greatest danger. "Mein Jakey! Help!"

Sparks flashed up past him on the heated smoky air. His heart pounded and he couldn't breathe, couldn't see. But the white- haired old man struggled upward to the aid of the cripple whom strong men, able and young, were abandoning to the flames as they sought safety in panic-stricken flight.

Lungs bursting, eyes bulging from their sockets, he reached the top floor at last. From a dark, closed door at his right came a smoke-choked whimper. "Jakey, Oi Jakey." Over him a glass skylight was closed, penning back the hot gases and the smoke, forcing them sidewise as it waited to force the flames.

In the murk Doc's foot clanged against a garbage can lying empty on its side. He bent to it, seized its handle, and it arced over his head, smashed against the skylight. There would be no mushrooming of the flames now.

He turned. The thick black pall, edged by lurid glare, was all about him. There was silence here now, silence except for the terrifying roar of the fire and distance-thinned pandemonium. Doc sobbed and reeled through the black gap to his right. He got the door shut, leaned back against it. Acrid fumes tore at his lungs, stung tears to his eyes. From somewhere ahead a moan came.

The old pharmacist dropped to hands and knees. Here, near the floor, he could breathe, though it seemed he inhaled knives that cut and twisted in his breast. He crawled toward that one despairing moan, and his groping hands found sleazy cotton fabric, cold flesh. He got his arms around the emaciated, frail body of the woman, pushed her along the linoleum to where a dim oblong of an open window showed in the smoke-blackened darkness. He heaved the flaccid body up to the sill, shoved her out onto the iron platform.

The chill air revived the woman. Her eyes opened, and horror stared from them. "Jakey," she gasped.

"IT'S all right, Mrs. Itskopf. I'm going back for Jakey."

His voice was hoarse, but very gentle. "You go on down the

ladder."

She pulled herself to her feet, tottered toward the square hole where the ladders began, the long spindly ladders that stretched so abruptly down to the street, and moved slowly toward them. Doc Turner was here. Doc Turner would take care of Jakey. She need fear no longer.

And the old druggist took one long look down the lattice-work that even now would take him down to safety, took one long look, and turned back to reel into black smoke that was now shot through with red tongues of flame.

He found at last the twisted body of the crippled lad. And when, by the exertion of strength that only the frenzy of despair lent his age-wearied muscles, he had dragged the limp form to that fire-escape window and lifted it out on the platform, the fire was close behind him. Its avid whirlpool of red and orange and yellow roared over the very spot whence he had pulled the boy, and its breath beat hot against his back. He scrambled out on the escape platform, tottered, and sprawled across Jakey's motionless form just as a rough face, soot-smeared beneath a red helmet, bent over him and the boy. His eyes closed...

"DRINK this."

Doc swallowed, and a fiery liquid burned down his throat. He opened his eyes, and he saw a young face, blue-capped, just above his own, saw the white coat of an ambulance surgeon.

He pulled himself erect. "I'm all right, Doctor," he husked, "I'm all right." His chest hurt, his arms and legs... But where was Jack? Had he, too, been one of the arsonist's victims? His bleared gaze circled the crowding faces about him, faces he knew—and he gasped.

That face, that long, sharp face with the icy eyes of nondescript color—his trembling hand lifted to point at it. "Grab that man!" he tried to shout, but his smoke-burned throat emitted only a squeak.

The fellow whipped around and was gone. Doc wrenched free and plunged after him, the crowd scattering from in front of him. He was through the knot of watchers, and the tall man was halfway down the block, was scrambling into a black sedan. Doc gulped, jumped suddenly at a sudden horn-blare beside him. He had almost run into a taxi which skewed across the blocked street. The druggist jumped for the running board alongside the driver, squealing, "Chase that car! It's the firebug. Chase it!"

The black sedan whipped around a corner, and Doc's cab skidded after it. "I'll get him if I got to rip the guts out of this boat," the driver yelled without turning his head, and the roar of his motor redoubled its thunder. "Me brother got boined Monday."

The red taillight of the sedan drew nearer as the dark front of an old dance hall flicked by. Turner glimpsed the sign: "Whileaway Hall." They were on Fanston Alley, then, and just ahead was the river. The incendiary would have to turn at the next corner, for beyond was the stone wall dead-ending the street. His own driver slowed for the turn.

But the sedan didn't make it! For just as the firebug's car reached that corner, there was the howl of a siren and blinding headlights of a rushing fire truck swung around and blocked him. The arsonist skewed, hurtled straight on toward the stone retaining wall and the turgid river below it.

The cab flicked past the long ladders of the pounding truck, and flicked across Eastern Avenue. The taillight ahead slackened, brakes screeched. The black car crashed against the stone parapet, and the tall man hurtled from the wrecked sedan. He crouched in the reflected beams of his own headlamps. Metal gleamed in his hand, and orange flame spurted from his gun. The cab's windshield crashed and starred, and the driver slumped over the wheel, groaning, "He's got me!"

Doc surged against the chauffeur's form, grabbed the wheel and fumbled for the gas button. His foot went down on it, and the slowing cab leaped again. The tall man fired once more. Doc heard the chunk of a bullet in his radiator, then the man was just ahead. The cab hurtled toward him; there was a solid thud, and he went down, shrieking, under avenging wheels. Doc leaped from the cab as it crashed against stone, glimpsed a pulped body, a dark, viscid pool. Asphalt hit him, and the world exploded in a burst of flame.

HOSPITAL smell was in his nostrils as he swung up through

darkness to light. His eyes opened, and he saw a white ceiling

above him, dim-lit. There was pain, nothing but pain all through

his old frame, but he knew he was alive. Someone moved beside

him, and he turned his head. "Jack!" he breathed. "Jack."

The redhead grinned. "Yeah. I'm here all right. Been watching for hours."

"But—I thought you were..."

"Shot? No. The fellow blazed at me as I came through the door, but I ducked in time, and he didn't dare try again because there was a cop just across the street. He slammed past me like a bat out of hell and got away. If the damn fool had had sense enough to stay away, he would have been all right."

"No," Doc murmured. "He knew I was on to him, and he dared not try to collect on his policies if I told what I knew. He had to chance coming back to find out whether or not I had gotten out of the fire. When he saw me laid out on the street, he stayed around to see how badly I was hurt, whether I would come to. And I did."

"You did, Doc, thank the Lord! And that was his hard luck."

"Yes." Andrew Turner's eyes closed, but there was a happy smile on his face. "It was hard luck. But there won't be any more fires on Morris Street."