RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

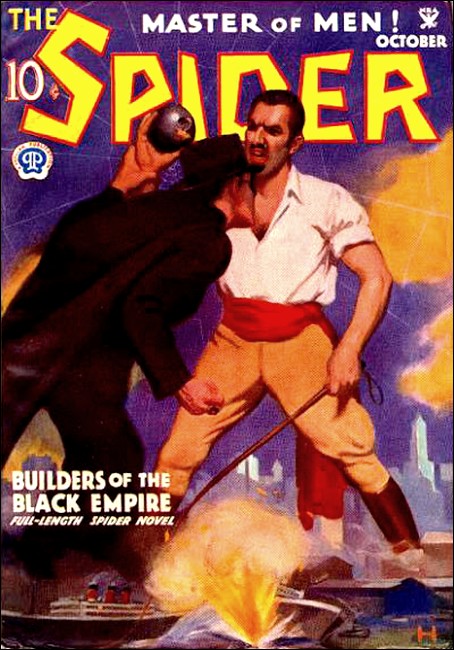

The Spider, October 1934, with "Doc Turner's Death Rendezvous"

Prison gates open in faraway Leavenworth, and Doc Turner gets an invitation to die!

THE shadows in the old drugstore on Morris Street bulked more blackly than usual along the shelving and between the grimy showcases, and the wee-hour silence seemed to brood with a queerly ominous hush. A night-owl "El" train pounded past outside, its clatter serving only to emphasize the quiet and to leave behind an added sense of pregnant dread. Behind the locked and bolted door of the ancient pharmacy the only light was a pallid beam that lay heavily, flat on the bare and splintered floor.

The thin layer of light seeped out from under the dirt-stiff curtain that during the day screened Andrew Turner's prescription room from the profaning gaze of his customers. Behind that curtain, raw luminance glared from an unshaded, pendent bulb; glinted from row upon row of bottles and little labeled boxes, and edged with its harshness the silver hair and stooped shoulders of the little old man seated at an ancient roll-top desk. Paper rustled, the scratch of a pen rasped the stillness, and a sigh quivered on air redolent with mysterious pungency of long-ago-dispensed decoctions, infusions, strange herbs and odoriferous drugs.

Doc Turner's gnarled, almost transparent hands blotted the check he had been writing, ripped it from its page. A few deft motions, and it was pinned to a white sheet headed "Statement of Account"; folded, slipped into an already stamped and addressed envelope, and added to an already tall pile of its fellows. The old druggist sighed again, jotted a few figures in the stub column of his checkbook, made a swift calculation, and noted the balance. A faint smile moved his bushy white mustache only slightly. "Two dollars and forty-three cents," he muttered. "After more than forty years. But they are all paid. I don't owe a cent." His age-bleared eyes strayed across the desk-top to where a flat, shiny automatic held down a newspaper clipping and a scribbled Government postcard. "All right, Mr. Wendell P. Logan, I'm ready for you."

His low voice was flat, grim; the smile was gone and his grayish face was set in stern, uncompromising lines. Suddenly one had a sure impression of strength, of hidden power that belied the age-shrunk, feeble body of the man. One knew, in that moment, how it was that the old druggist was a mighty tower of strength to the bewildered-eyed, otherwise friendless aliens crowding the teeming warrens of Morris Street. One knew, too, why the word had gone out, through the burrows of the human rats who prey on the defenseless poor, that it was safer to steer far clear of the poverty-stricken slum Doc had served for so many weary years. There were those who had ignored that warning; some of them ate now at the long, silent tables provided by the State for its unwilling guests—and others would never eat again. Andrew Turner's acid-stained thumb had drawn a line around his neighbors' homes, and his exploits had broadcast to the slimy crooks of a great city the edict, "Keep out!" Doc's Deadline, they called it, and it had been a veritable line of death for more than one two-legged jackal.

The bong of a far-off tower-clock came vaguely into the muted drugstore. Once. Twice. The druggist's frail form tensed. He reached slowly across the desk, his fingers closed on the butt of the automatic, pulled it closer. The card and the clipping came with it, lay in front of him. He seemed to be waiting, taut as a piano string, for something. He was waiting for something—he was waiting for death.

A furtive noise sounded out in the store front, the stealthy scrape of fabric against wood. Doc did not seem to hear it. He was reading the newspaper item for the hundredth time; the one-inch, inconsequential squib that had been buried on an inside page to fill out a too-short column, a delayed filler not worthy of immediate publication:

"LEAVENWORTH—Friday (U.P.)—A Presidential pardon today liberated Wendell P. Logan of Greater City from the Federal Penitentiary here. Logan was serving a five-year sentence for violation of the Harrison Narcotic Act."

THAT was all, but when Doc had chanced on it this

morning, the cooling blood had pulsed a little faster in his

veins and his thin lips had twisted in bitterness. Wendell P.

Logan was free again, after six short months. He was a

sanctimonious man of seeming wealth who had plied his devil's

trade under guise of a philanthropic interest in the Morris

Street Settlement House.

Logan was free—but olive-skinned, frank-eyed young Angelo Liscio mouldered in a suicide's grave because he had dared to defy the master dope-seller. Logan was free, but dozens of the youth of Morris Street were dragging out shaking-limbed, dull-eyed, hopeless lives because he had debauched them to line his pockets with gold. Only the devotion, the subtle strategy of the old druggist had put an end to that black career; only the mechanical ingenuity and fighting ability of broad-shouldered, stalwart Jack Ransom and the quick-witted shrewdness of little Abie, the Semitic errand-boy. All three had come close, very close, to death before Logan had been laid by the heels. And now—the great gates of the prison to which they had sent him had opened and Wendell P. Logan was a free man once again.

These thoughts had scarcely had time to flit through Doc Turner's old head when the morning mail had arrived. Bills, ads, and a postcard—the one that lay now in front of him. A postcard across which neatly formed, miniature letters snaked with a cold menace that no broad scrawled strokes, no sketched skull and crossbones, could have conveyed.

My very dear Doctor:

I find myself at last in a position to settle the debt I owe you. With interest. The total should be sufficient to relieve you of worry for the rest of your years. I shall arrive late Monday night. Please be in your store to meet me.

Wendell P. Logan.

An innocent enough appearing message. Yet a chill wave

had rippled up Doc's spine as he perused it, and the blood had

drained from his lips. For the bland, ingratiating words could

have only one meaning: "I am coming to kill you," they

said. "Get ready."

Somehow the brazen effrontery of the thing, the assured naming of time and place, had invested the threat with a dread inevitableness that had pierced even the old pharmacist's fatalism. "I am coming to kill you and I am not afraid to let you know because nothing you can do will save you."

And so Andrew Turner was waiting in the familiar back-room of his store to keep a rendezvous with death. But first he had set his affairs in order with the meticulous care that had characterized all his business life. If, indeed, he were to die tonight, no one would suffer for it. No one, that is, except his people, his neighbors—all those half-bewildered wops and kikes and squareheads to whom he had shown the only kindliness in a strange, cruel land. If Doc had schemed some answer to Logan's challenge, it was for their sake, not his own. His race, come what might, was nearly run, and he was tired, very tired. But, if he were to go, there would be no one, no one at all, to take his place in their bleak lives.

THE distant tower-clock bonged the half-hour. The

vibrations of the stroke died away, but Doc's head jerked to the

curtained doorway as incautious footfalls thudded toward it. A

hand, clutching a bulldog revolver rippled the curtain's edge,

swept it aside. And a squat, big-shouldered form burst

through.

"Hell, Doc," Jack Ransom growled. "It's a frost. Logan's bluffing, or he's tumbled to my laying for him in the phone booth. Maybe he lost his guts doing that stretch. Anyway, he's not showing up."

Turner's cheeks flushed with momentary anger, then the red faded away. "Impatient, Jack? Well, I can't blame you. You'll learn how to wait soon enough. Too soon, perhaps. But you're wrong. I'm as sure as I am you have red hair that the attack on me will be made before dawn, though I don't know how. Never mind, though. Wendell P. would never have walked into as simple a trap as the one you've just spoiled. I told you that before. He has too much brains for that, and he's had plenty of time to work out a plan. When he strikes, it will be from some unsuspected quarter, like the rattlesnake that he is."

"Judas Priest! How's he going to get at you without coming in here, short of blowing up the building?"

"No, that won't be the way, nothing as brutal as that. He's shrewd, that man, shrewd and cruel. He..." Turner stopped suddenly, froze. A steel-lined door bisected the shelving at the back of the prescription room, a bolted door, and something was scraping underneath it...

The white corner of an envelope showed, then its full oblong. Jack exploded into action. A frantic leap took him to the portal, two jabs of his heavy-knuckled, freckled hand shot back the bolts. "Duck, Doc," he yelled. The door was open and he was through, swallowed by the back maw of the alley beyond. The door clanged shut behind him.

The old man had not moved. But he was staring at the white rectangle on the floor, just inside the threshold, staring at it as if it were in verity the reptile to which he had just compared Logan. In the light-glare he could see the writing on it, could see that it was in the same copper-plate chirography as the postcard on his desk. He could read what the tiny letters said.

Andrew Turner, Esq.,

Address...

What was there about the thing that was striking fear into the old druggist's fighting heart, crawling fear such as never yet had come to him? He didn't know; he couldn't have known, and yet he was afraid—deathly afraid.

Apparently he had not yet moved when, minutes later, the door popped open again and Jack shouldered in. The younger man thumped the bolts back into place, turned. His broad-planed face was lined, his eyes smouldering, and his thick nostrils expanded and contracted with his breathing. "Lost him," he grunted. "He was at the alley-mouth by the time I got out. When I got there the street was clean. It wasn't Logan, and I didn't dare go further for fear it was a ruse to separate us."

Doc looked at him bleakly, almost disinterestedly. "No," he said in a flat, dull tone. "It was no ruse. Logan sent me his calling card, that is all. His calling card and a little note."

THAT didn't sound like Doc Turner—the defeat, the

utter hopelessness in his voice. Ransom shot a quick glance at

him. The pharmacist's face was fish-belly white, and minuscule

drops of cold sweat dewed his wrinkled brow. "What is it, Doc?"

Jack gasped. "What did the letter say?"

Mutely, Turner held the envelope out to him. One edge was torn now; it had been opened. Ransom took it from Doc's trembling hand, poked a finger into the aperture. And he squeaked, oddly, his face contorting suddenly with startlement, with revulsion. Then he had jerked his finger out again, and was gazing at it, narrow-eyed, his mouth tightening to a straight, harsh line.

Around his extended digit, clamped like a tight spring, was a coil of wiry, black hair. "Good Lord!" he squeezed out. "It isn't—it can't be..."

"Abe's," Turner finished the sentence. "There isn't any doubt in your mind, is there?"

"No," Ransom said slowly. "No, there isn't." A picture of the eager-eyed youngster danced before him; his thin face, the bush of stiff, jetty hair that piled atop his head, as characteristic of his race as the huge, angular nose that was constantly in need of attention. Despite his senior's efforts to the contrary, the urchin constantly obtruded into their battles with the underworld, usually with telling effect. But what...?

"Read the letter, Jack."

The other got out the single sheet. He had difficulty in making the dancing letters stand still enough for him to decipher them. But he managed it, and as he read, his young face grayed and was suddenly drawn and old.

"On second thought I have decided that it would be more convenient if you were to come to me to receive payment of that debt I owe you. I am naturally eager to get the matter off my mind, and so I have arranged for the presence of a little friend of yours who has asked me to send you the enclosed token of his esteem.

"Should you prefer, I can arrange to pay at least an installment to your friend—in fact, if I do not see you within one hour from the time this missive is delivered I shall do that. But I do not think he will like it and I am persuaded you would rather collect in person.

"If I am right, light the lamp behind the bottle in your window, the red one, and unlock the door. Someone will call for you—but not I, my dear doctor, not I! I like the little fellow's company too much to leave him, until you are here to take his place.

"By the way, the carrot-headed young man can do much harm, and no good at all, by interfering with our negotiations. I should earnestly advise him to go home to bed. Any attempt on his part, or yours, to bring the police into the matter will result disastrously to the little fellow.

"In the courtly phrase of our British cousins, I am, my dear Doctor, your most humble and utterly obedient servant,

"Wendell P. Logan.

"P.S. Please be good enough to bring this and my card with you."

The paper crumpled slowly between Jack's shaking fingers.

He licked dry lips and husked words out between them. "He's got

Abe, and he's going to kill him."

Turner shook his head. "No. He does not threaten to kill him." It was as if an automaton spoke.

Blood surged back into Ransom's face, making it black. A little muscle twitched in his cheek, and his neck seemed to swell. "God! You don't think...?"

"Torture. That is what he means by paying the debt in installments. Jack, you had better go home and go to sleep. Please mail these on your way."

"But—but Doc...!" It was a groan, a prayer. "Doc...?" Big hands, freckled and laced with a faint network of grease, fumbled out, taking the letters. "You're not...?"

The old pharmacist managed a smile, a wistful curling of his thin lip-corners. "What else is there for me to do?" He shrugged. "And after all, it doesn't make much difference. A year, two, not much more. But you'll carry on, my boy. They need somebody—these poor cusses around here. You'll carry on—and little Abe."

Jack's throat worked, but he made no sound. His eyes said it, his blue eyes that were no longer smiling. He turned, stumbled through the curtain and across the dark store-floor. The way he juggled the key in the lock of the front door was as if he were partly blinded...

DOC clicked a switch over, and a show-bottle in the

window flared into light. It spilled red over the display, over

the sidewalk outside, and it seemed as though they were bathed in

blood. Its scarlet glare lit Doc Turner, standing just inside the

doorway in his shabby overcoat and battered felt. The druggist

had somehow lost the stoop the years had laid on his shoulders;

he was erect, almost soldierly. His old eyes were peering out

into the dark reaches of Morris Street, saying goodbye.

An "El" train thundered by overhead, sweeping debris-strewn pavements with a long line of yellow oblongs. The distant tower- clock bonged three times.

Across the street a shadow, black in a black vestibule, moved. Its outlines firmed, and it was a man coming down the high stoop, coming across the cobbles; a man who rolled as he walked, whose long arms swung ape-like to his knees, whose nose was mashed flat against a face that was almost concave. Turner glimpsed a blackened nail on the finger of one hand and knew him to be Carl, the ex-pug who had done Logan's dirty work before. It had been by following that black nail, he recalled, that Abe had located the drug-seller. Carl reached the door, pulled it open and lurched in.

The man was breathing hard through his smashed nostrils. His hands reached for Turner, slipped under his coat and pressed close up and down his slim frame in a quick but expert frisk. He brought out Logan's two missives, touched a match to them and watched them burn. The last fragments fluttered to the floor, were ground under his heel.

"Dat's dose," he grunted, leering into Doc's face, so close that his oniony breath was almost overpowering. "Come along! De big feller's waitin' for yuh. An' how!" His spatulate fingers dug into the old pharmacist's upper arm, clamped like steel teeth. "Git movin'."

"That isn't necessary," Doc said, mildly. "I shall not—"

"Shut up!" the gorilla snarled. The back of his hand smashed against the old man's mouth. "Button yer lip, if yuh know what's good fer yuh or yer'll git more o' dat. Plenty more. I ain't takin' no guff off of yuh, one guy handin' it out is enough."

Turner rubbed pink from his bushy mustache. He said nothing more as he was led a block down Morris Street and around an unlighted corner, but there was a cold glitter in his eyes that had not been there before. If Carl had been bright enough to have guessed its meaning, he would not have swaggered quite so much. A small sedan waited halfway down this sleeping block, its parking lights only just aglow. The pug stopped at its side, jerked a back door open, pulled something out. And suddenly a dark cloth enfolded Doc's head, was pulled down over his shoulders, down still further. A rope pulled cruelly tight around his ankles. He was in a black bag, blinded and helpless. He felt himself lifted, tossed onto a hard leather seat. He heard starter-whirr, gear- clash, knew that the sedan was in motion.

Sudden panic swept through the old man, shaking the icy calm to which he had forced himself. Where was Carl taking him? He could be murdered in this sack—a knife-thrust, a single shot would do it—and tossed into some vacant lot or over the parapet of a bridge. Was that to be his fate—was his sacrifice to be in vain? Abe, after all, had been largely instrumental in the drug-trader's downfall. Was it likely the man would limit his revenge to Doc alone?

These torturing thoughts dragged through the weary treadmill of his brain for an eternity of jouncing, and then, quite suddenly, the horn honked twice, hinges squealed somewhere, the car pitched forward as if on a downward ramp, a door slammed, and the engine-sound had stopped.

Still in his bag, Doc was dragged from the seat on which he lay; was lifted to a husky shoulder like any sack of potatoes. He judged he was being carried up a flight of stairs, heard footsteps on the bare wooden treads other than those of the one who bore him. That must be Logan, he thought, and his flesh crawled. Even before, under his pose of bland philanthropy, the man had been incarnate evil. What had prison made of him?

The climb ended. Even through the thick, clogging fabric Turner sensed the musty odor of a long uninhabited house. Nearby someone sobbed, whiningly. Doc thumped down on boards, and a voice said, "All right, Carl, pull him out of it." The cord around his ankle loosened, and the cloth was being peeled from him.

DOC blinked at a dingy ceiling on which unsteady light

flickered. He pushed his hands down against splintered wood and

pushed himself up to a sitting posture. A candle wavered on a

tottering mantel; a kitchen table was cluttered with greasy

paper, curling rinds from sliced bologna, two beer bottles, one

half-empty, the other altogether so. His aching eyes pulled

nearer, and he saw long legs in black trousers, the swinging hem

of a square-cut, clerical coat, a hand from which a blued

revolver snouted. Looking still higher he saw a face gazing down

at him, a sharp-chinned face in which tight, cruel lips cut

across jail-pallor and from which slitted, lurid eyes met his

own. The mouth twitched, and a hard toe drove suddenly,

excruciatingly, into his side. "Get up," Logan gritted. "Get up

on your hind legs."

The old man bit his lips to repress a groan, struggled erect. Agony stabbed his side, and he was sure a rib was broken. He found a bundle in a dark corner, saw that it was Abe, gagged, legs and arms wired to his scrawny frame. The urchin's black eyes stared at him, bulging with horror, dark with despair. "How do you like it, Dr. Turner?" Logan's thin voice came again. "That's the way they do it at Leavenworth if you don't move quick enough to suit them."

"They do something else at Sing Sing," Doc answered, "to murderers. They put them in a chair and throw a switch. They say it doesn't hurt very much, but I should hate to try it." Black cloth had been tacked over the windows. Carl leaned against the closed door, his brutish face surly but his piglike eyes glittering with sadistic anticipation.

"Nor I. And I won't. By the time you are found here I shall be days out at sea, on my way to a country where extradition writs are scraps of paper. But you won't know about that. You won't know anything."

The old druggist brought his eyes back to Logan's face, caught and held the other's lewd orbs. "There are radios on ships," he said in a low, steady voice. "And ship captains are not likely to aid killers in escaping."

"You're doing a lot of worrying about what's going to happen to me. That's—" Logan broke off suddenly, and his eyes signaled Carl. The interruption was only momentary, then he was continuing, "—my business. Yours is collecting that little debt..." The pug with the mashed nose wheeled, jerked open the door. A shadowy form was visible outside; a gun roared. It was Carl's gun, and the intruder slid down along the doorpost, sprawled on the floor. His head came across the threshold; the candlelight reached it. His hair was a carroty-red—Doc's heart skipped a beat—except where seeping blood dyed it scarlet. Pent breath whistled from between Logan's lips, but his revolver and his eyes were steady on the old pharmacist.

The ex-pug bent over his victim. "Hell!" he blurted. "He ain't croaked. I just creased him." His elbow came up as his finger curled around the trigger of his gun. Doc's stringy muscles corded, his knees bent for a desperate leap, and Logan rapped out an imperative: "No! Carl, no!"

The thug's head pulled around. His eyes were almost invisible behind slitted lids. There was a muzzle of white around his mushy mouth and two spots of white either side of his nostrils. "Cripes, Boss!" His whine was like that of a bulldog held back from the kill. "Lemme give it him! Lemme blast him!"

THEY had let Logan keep his grizzled mustache in

Leavenworth; its grayness, the grayness of his skin, and a

curious greenish glint in his pupils gave him a feline

appearance, despite his size. He purred now like a cat, a cat

playing with its prey. "Not yet, my boy. Not yet. Pull him in and

get the door closed. This is going to be good."

Carl's wheeze made him seem more than ever like a bulldog, a drooling-mouthed bulldog whose undershot jaws tear for the sheer pleasure of inflicting pain. He put his broken-knuckled paws on Jack's limp form, heaved him in. The youth skidded across the floor, thudded against a table leg. Blood trickled down his forehead, over his closed lids.

The corners of Logan's lips lifted in what might have been intended for a smile. "This is better than I planned, Doctor Turner, to have all of you call upon me. The Three Musketeers of Morris Street!" Somehow his burning stare contrived to be on Ransom and Doc at the same time. The muzzle of his gun was a black tunnel to the white-haired pharmacist. His other hand swept out, closed about the beer bottle that was still half-full and jetted its contents into Jack's face.

The liquid frothed over the still, white countenance. Jack jerked awake. "What?" he spluttered. "What the...?" Then realization came into his eyes, and misery. "Doc," he groaned. "Doc—I couldn't help it. I didn't think they could hear me."

Turner's smile was warm, genuine. "It wasn't your fault, Jack. I didn't hear you. I don't understand how he did. But you should have stayed home. You can't accomplish anything here."

"I couldn't let you..."

"That's enough," Logan grated, "for you two. I'll do all the talking that's necessary here. And I'm going to do some now. You there, I want to know how you got here."

Jack looked up at him with eyes that hated. "Go to hell," he squeezed out, "and find out."

The big man bent, lightning-swift. His gun-sight slashed across Ransom's cheek, and then he was straight again in a flash, watching Doc. A red gash showed where his barrel had sliced Jack, its edges obscuring with the welling blood. "You dog!" Jack howled and came up to his feet in a long, flowing motion, his fists clenched. Carl growled, was plunging toward the youth.

"Wait," Doc snapped, sharply. "Wait! Quit it, Jack. There's no use in that. Quit it, Carl—he'll tell." For an instant the old man dominated the situation, halted the impending brawl. "Answer him, boy."

The redhead reeled, put a hand on the flat table-top to support himself. "I couldn't go home and leave Doc face it alone," he said slowly, painfully. "In spite of the fact that he had given in to you. So I walked out as if I were going home, but I kept on going around the block and hid in a hallway. I saw your gorilla come across the street, and then I saw him come out with Doc and walk down my way. I remembered passing a dark sedan on the side street and figured they were making for that. I took a chance, got back to it, and scrouged down on the floor in the back, under a rug that was there. It was dark, and the dope didn't look when he tossed Doc in. It was simple as that."

Logan's eyes were red coals. His head turned till it faced Carl, and his voice quivered with contempt. "I knew you were dull-witted, but I didn't think you were quite as brainless as that."

The pug crouched, his face suddenly livid, his muscles bunched. "Cut it!" he yelled. "You scum! I won't take dat from no one. I been takin' too much from you already."

The jailbird took two steps backward, so that his gun covered the three of them. His face was an icy mask. "You'll take what I hand you, and like it. You've gotten damned swell-headed while I've been away, but it won't go down with me." But it wasn't what he said that wiped the ferocity from Carl's visage and loosened his finger, already tightening on the trigger; it was the cold venom in his slow words, and the blaze of death in his eyes. Mere brutishness could not stand up against the evil impact of a brain twisted, half-crazed, but still a brain developed far beyond that of the other.

MEANTIME Doc Turner, standing impassive, apparently

resigned, was inwardly aquiver with watchfulness. He was missing

none of the shifting nuances of the situation, was straining

every iota of it to find something he might use, as he had so

often filtered gallons of liquid to recover grains of precious

precipitate. He felt Jack's eyes on him, and little Abe's, felt

the appeal in them, the hopelessness. "Isn't it about time we got

this over with?" he asked mildly.

Logan's eyes came back to him, burning, sardonic. "You seem to be in a great hurry," he drawled. "An awful hurry for what you've got coming to you."

"I am in a hurry to get the little fellow out of here."

A chuckle, somehow horrible, came from the tall ex-convict. "That's it, eh? Well—I am sorry to disappoint you. Abe is staying right here. Redhead fixed things nicely. He came here of his own accord, and he's let me out of my bargain."

"You dog," Jack rasped. "You yellow-bellied baby-killer." He started to push himself away from the table, but Carl's gun was on him, and Logan's.

"Steady, old man," Doc said softly. "Steady. That won't get you anything." Then, to Logan: "I didn't think you would go through with it. All Jack has done is supply you with a salve for whatever pitiful remnant of a conscience you may have. You never had any intention of letting Abe go."

Logan shrugged. "Perhaps not. But what do you think you can do about it?"

"I can, I suppose, do nothing. But there are others who will, men in uniform who will follow you wherever you go, follow you till a hand taps you on the shoulder and a voice says, 'Come with me, murderer.' And then, there will be no Presidential pardon to save you from the chair."

Ridges stood out along Logan's jaw, but he didn't answer immediately. He spoke out of the side of his mouth, instead, to Carl. "I'm getting tired of this. Get the wire and truss them up."

"It's down in the cellar," the thug muttered.

"Well get it, you fool. Snap into it."

The door opened, closed again behind Carl. Logan's unblinking stare came back to Doc. "You'll have plenty of time to wonder if you're right about that, while you're waiting here to die."

Turner's voice was sharp. "What do you mean? What are you going to do?"

His humorless smile made the killer's face more evil... "You didn't think I was going to pass you out quick, did you? That wouldn't gibe with the hours you made me spend in Leavenworth, the hours when I sat staring at gray walls and iron bars, planning this moment. You're going to spend hours, you and your friends, long hours waiting while hunger gnaws at your bellies and you dry out, little by little, till every cell in your body shrieks for water, and you pray for death. You'll be gagged, but it wouldn't help if you were not—this place is miles from any travelled highway. I used it for years to pack my coke, and nobody ever came near enough to even know the place was here. You'll be gagged and wired so well that all your writhings will do you no good, and you'll watch each other die—slowly—horribly."

He lipped the words slowly, lasciviously, watching Doc's face for a trace of fear, and although that face was an expressionless mask, icy fingers stroked the back of the old man's neck and a cold hard lump lay at the pit of his stomach. Yet his voice was low, calm, almost indifferent. "I see," he said. "I see. A very appropriate revenge, quite worthy of you. And I suppose you and Carl will have many a chuckle over it as you sail over the bounding main."

A demoniac grin twisted Logan's mustache. "I'll chuckle right enough, but Carl won't. You don't think I'd chance taking that lackwit along, do you? He'd be sure to pull something that would spill the beans." A ring of boastfulness had crept into his tone. Cunning as he was, he could not resist it, for his was a mind tainted at the beginning with an abnormality that had sent his undoubted talents into the sewers of criminality, a mind weakened by imprisonment and brooding over the one defeat that had marred his career. The author of that defeat was now before him, and it was inevitable that he display the full canvas of what he thought to be his cleverness.

DOC was suddenly seized with a coughing spell, the noise

he made covering the faint sound he had caught, the thudding

footfall just outside the door. He managed to control the spasm

and said innocently, "Then you're going to leave Carl behind. I

shouldn't think that would be any safer."

"The way I leave him will be safe enough," Logan chuckled. "He won't be making any more mistakes with a bullet in what he calls his brain. I—" The door crashed open, a bull-roar thundered in the room, and a bulking form hurtled through, thick arms flailing.

"You lousy, double-crosser!" Carl shouted. He catapulted at Logan, his gun dropping, forgotten in his rage, ham-like fists whistling. The big man ducked. His gat swept up, and orange flame lashed from it. Carl jerked as lead thumped into him, kept on coming. His knuckles pounded into the saturnine face—pounded again—muffled gun-roar drowned his bellow as a stream of death poured into him point-blank. A gout of blood burst from his mouth, carmined his blue-jowls, and suddenly life went out of him as wheat pours from a ripped sack. Like that ripped sack he collapsed, pawing at Logan's erect form.

All this had been almost instantaneous, but now Jack hurled himself at Logan, and Doc darted in, frail, but suddenly viperish. The old man's hand clutched the hot gun barrel, ripped it from Logan's startled grasp. The big man doubled up with the piston-rod churning of Ransom's fists into his stomach. His foot lashed out, caught Jack in the groin, and the youth pelted to the floor, writhed in agony.

Logan twisted, snarling, and came for the little druggist. Doc jerked up the captured gat, pulled the trigger. A click answered him—the gun was empty! A gurgling scream came from Abe, the extremity of his terror forcing the sound through his gag. Turner hurled the useless weapon into Logan's contorted face. It staggered him, and the little druggist leaped for the mantelpiece, swept the candle from it. The flame gutted as it fell, went out. Velvety blackness rushed in. Turner whirled, got hands on the flimsy table, upheaved it. Glass crashed, wood thumped against something soft, and Logan hurled screaming obscenities into the darkness. The table smashed to the floor as the big man heaved it from him, but Doc was darting around the room, hugging the wall. The noise Logan was making was more animal-like than human as he threshed about, searching for the old druggist in the impenetrable darkness.

Turner found the room's door. Jack was here, and Abe. Logan would kill them before he could get help. The panel oriented him. He stooped way over, darted into the room, his fingers trailing the floor. They found metal—the gun Carl had dropped in his berserk plunge. He lifted with it; Logan's howls located him at once, but Doc dared not shoot. Jack might have moved—even Abe might be in the line of his fire.

His hand went out behind him, found the doorknob. Hinges squealed, a gray oblong was visible. Doc's slight form was silhouetted against the dawn-light, slipping out. "Got you!" Logan roared. "Got you!" and he crashed across the shattered room, got to the door just in time to have it slam in his face. He pulled it open, plunged through.

"Pow!" the heavy report of Doc's gun pounded. "Pow!" Two tiny blue holes appeared on Logan's forehead, an expression of ludicrous surprise on his face. His knees buckled, he crashed down, was a shapeless, motionless bundle on the dusty floor.

BY the time the old druggist managed to get back into the

shambles where the drama had been played out, Jack was on his

feet and was weaving toward the door. "Doc," he gritted. "Doc,

are you all right."

Turner smiled feebly. "All right, my boy, except for a rib that's going to take a long time to heal." He turned from the lad to whose freckled face a grin had come back, staggered to the corner where Abie still lay, his eyes dancing. The wires that bound the urchin were twisted, cut into his flesh. But Doc got the gag out first.

"Phooie," the brat spat. "Phooie. Dot dittn't taste so good. Baht eet tasted better as de gun vot Carl stuck in my snoot ven he come out from behind mein hall-door and sez, 'Come vid me, you leedle kike.' "

"So that's the way they got you, on your way home from the store. Well, Abe, we got you out of a pretty pickle this time."

"Peekles," he sez. "Peekles!" I dun't vant ever to eat peekles again. Vun from dem I had it een mein mouth ven eet happened. I joost swiped eet from de pail outside Ginsberg's delicatessen. I svallowed it whole und—oi vay." His face grimaced. And then, quite suddenly, he was trembling all over, sobbing.

"Abe! What's the matter, Abe." Doc's voice was all solicitude, tenderness. "It's all right son. It's all over."

"I—I know it ees," the youngster sniffled. "I know. But I ken't forget it dot ven I seen you standing dere vid dot guy's gun on you, I tought it dot you vas leeked. Soch ah foolishness! Dey can't leek Meester Toiner—all de crooks in de whole voild ken't leek de droggist from Morris Stritt!"